Abstract

The effects of acetic acid and extracellular pH (pHex) on the intracellular pH (pHi) of nonfermenting, individual Saccharomyces cerevisiae cells were studied by using a new experimental setup comprising a fluorescence microscope and a perfusion system. S. cerevisiae cells grown in brewer’s wort to the stationary phase were stained with fluorescein diacetate and transferred to a perfusion chamber. The extracellular concentration of undissociated acetic acid at various pHex values was controlled by perfusion with 2 g of total acetic acid per liter at pHex 3.5, 4.5, 5.6, and 6.5 through the chamber by using a high-precision pump. The pHi of individual S. cerevisiae cells during perfusion was measured by fluorescence microscopy and ratio imaging. Potential artifacts, such as fading and efflux of fluorescein, could be neglected within the experimental time used. At pHex 6.5, the pHi of individual S. cerevisiae cells decreased as the extracellular concentration of undissociated acetic acid increased from 0 to 0.035 g/liter, whereas at pHex 3.5, 4.5, and 5.6, the pHi of individual S. cerevisiae cells decreased as the extracellular concentration of undissociated acetic acid increased from 0 to 0.10 g/liter. At concentrations of undissociated acetic acid of more than 0.10 g/liter, the pHi remained constant. The decreases in pHi were dependent on the pHex; i.e., the decreases in pHi at pHex 5.6 and 6.5 were significantly smaller than the decreases in pHi at pHex 3.5 and 4.5.

Acetic acid is a by-product formed during yeast alcoholic fermentations; e.g., in wine and beer fermentations the levels of acetic acid produced may be 1 to 2 g/liter (13) and 150 to 280 mg/liter (8), respectively. Furthermore, acetic acid is a potential inhibitor of yeast growth (1, 14, 16). Acetic acid is believed to uncouple energy generation from growth in Saccharomyces cerevisiae by dissipating the proton motive force across the plasma membrane (15, 20). The uncoupling mechanism of acetic acid involves passive diffusion of acetic acid in its undissociated form across the plasma membrane of S. cerevisiae. Once inside the cell, the undissociated acetic acid dissociates due to its pKa of 4.75 and the higher intracellular pH (pHi), causing intracellular acidification. To counteract this acidification, protons have to be pumped out of the cells by the plasma membrane ATPase, at the expense of ATP (15, 20). Thus, the pHi seems to be a crucial factor involved in the inhibitory effect of acetic acid on S. cerevisiae. However, very little is known about the effect of acetic acid on the pHi of S. cerevisiae. Pampulha and Loureiro-Dias (15) have described the effects of acetic acid and extracellular pH (pHex) on the pHi of fermenting S. cerevisiae cells as determined by using the distribution of radioactively labelled propionic acid to measure pHi. These authors concluded that the pHi of S. cerevisiae decreases with increasing extracellular concentrations of undissociated acetic acid and that this decrease in pHi depends exclusively on the extracellular concentration of undissociated acetic acid and is independent of the pHex.

In this work we used a new experimental setup comprising a fluorescence microscope and a perfusion system to study the effects of acetic acid and pHex on the pHi of nonfermenting, individual S. cerevisiae cells.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Microorganism and growth conditions.

A commercial strain of lager yeast, S. cerevisiae (catalog no. 2155), from the Collection of Pure Cultures of Brewing Yeasts (Alfred Jørgensen Laboratory Ltd., Copenhagen, Denmark) was grown in 2.5-liter European Brewing Convention tubes at 14°C in brewer’s wort with a specific gravity of 10.8°P (1°P is equal to 1 g of sugar, as sucrose, per 100 ml of wort at 20°C). The wort was oxygenated so that it contained 10 ppm of dissolved oxygen before inoculation, and the rate of inoculation was 106 cells × °P per ml of wort. Cells were harvested in the stationary phase (i.e., after 146 h of fermentation).

Staining of cells with FD.

The total cell number was determined by using a Neubauer counting chamber. A cell suspension was centrifuged at 3,000 × g for 4 min at 4°C. The supernatant was discarded, and the cells were resuspended in cold phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) (containing [per liter] 8 g of NaCl, 0.2 g of KCl, 1.44 g of Na2HPO4, and 0.24 g of KH2PO4; pH 5.6) to a final concentration of 2.5 × 106 cells/ml. Fluorescein diacetate (FD) (catalog no. F-7378; Sigma) was added to the cell suspension from a stock solution (2.4 mM FD in acetone) to a final concentration of 12 μM, and the preparation was mixed thoroughly for 10 s (final acetone concentration, 0.5% [vol/vol]). To minimize photobleaching, the cell suspension was incubated for 10 min in the dark at 40°C and immediately transferred to ice, where it remained for at least 10 min. FD is a nonfluorescent prefluorochrome that is taken up by passive diffusion by S. cerevisiae cells (3). Once inside a cell, FD is hydrolyzed by unspecified esterases, which results in the fluorescent compound fluorescein (10). Fluorescein is accumulated within the cell due to its polarity (17). Before microscopic analysis the cells were resuspended in PBS having the same pH as the perfusion solution used in the experiment (see below).

Perfusion system for dynamic studies of individual cells.

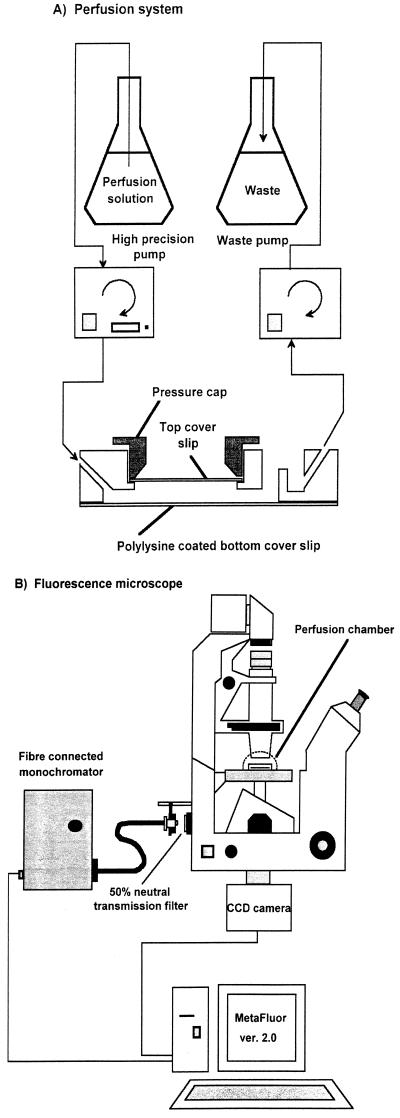

The perfusion system used is shown in Fig. 1A. The perfusion chamber (model RC-21A cell culture-perfusion chamber; Warner Instrument Corporation, Hamden, Conn.) was assembled with a poly-d-lysine (catalog no. P-6407; Sigma)-coated bottom coverslip (24 by 32 mm; Knittel Gläser, Bie & Berntsen, Rødovre, Denmark) and a top coverslip (diameter, 15 mm; Warner Instrument Corporation). Previous experiments in our laboratory had shown that poly-d-lysine was a useful agent for immobilizing yeast cells on the bottom coverslip during perfusion (data not shown). The chamber was sealed by using silicon grease. The volume of the perfusion chamber was 0.25 ml. The stained cell suspension was placed in the assembled perfusion chamber and allowed to settle and immobilize on the polylysine-coated bottom coverslip. Subsequently, the chamber was mounted on an appropriate platform (type PH1; Warner Instrument Corporation) and placed on the stage of a microscope (Zeiss model Axiovert 135 TV; Brock & Michelsen A/S, Birherød, Denmark). Solutions (see below) were perfused through the inlet of the chamber at a rate of 0.6 μl/s by using a modified Alitea XV pump (Microlab Aarhus A/S, Aarhus, Denmark) and were removed from the outlet of the chamber by using a model 101U pump (Watson Marlow, Wilmington, Mass.). The perfusion solutions consisted of PBS (pH 3.5, 4.5, 5.6, and 6.5) and 2 g of total acetic acid per liter in PBS (pH 3.5, 4.5, 5.6, and 6.5) at 25°C. In each experiment the perfusion chamber was filled with newly stained cells, and perfusion was initiated at time zero with a perfusion solution having the same pH as the cell suspension.

FIG. 1.

Schematic diagrams showing the perfusion system (A) and the fluorescence microscope (B). CCD, charge-coupled device.

Measurement of pHi of individual cells.

The pHi of an individual cell was measured by ratio imaging by using a fluorescence microscope as shown in Fig. 1B. During perfusion, stained cells were excited at 490 and 435 nm as described by Slavik (19) with exposure times of 1,000 and 500 ms, respectively. The excitation source was an optical fiber-connected monochromator with a 75-W short-arc xenon lamp (Monochromator B; T.I.L.L. Photonics GmbH, Planegg, Germany). A 50% transmission neutral filter was installed between the optical fiber and the microscope. Emission was collected at wavelengths between 515 and 565 nm by using a band-pass emission filter (Zeiss type BP 515-565; Brock & Michelsen A/S), a beam splitter (Zeiss model BSP 510; Brock & Michelsen A/S), and a cooled slow-scan frame transfer charge-coupled device camera (EEV 512 × 512 12-bit frame-transfer CCD; Princeton Instruments Inc., Trenton, N.J.). Ratio imaging of emission signals collected from excitation at 490 and 435 nm was performed by using the software package MetaFluor, version 2.0 (Universal Imaging Corporation, West Chester, Pa.). Before ratio imaging, cells were focused and selected as regions of interest under bright-field illumination, to avoid subjective selection based on fluorescence, by using a Zeiss Fluar oil objective (magnification, ×100; numerical aperture, 1.30). One region of interest comprised an individual cell; i.e., the emission obtained from a region was the average value for an individual cell. Ratio imaging was initiated at time zero of perfusion. Images were recorded at 10-s intervals, and each experiment was terminated within 10 min. In each experiment between 20 and 30 randomly selected individual S. cerevisiae cells were analyzed. Each experiment was repeated at least twice, and the results obtained were conclusive.

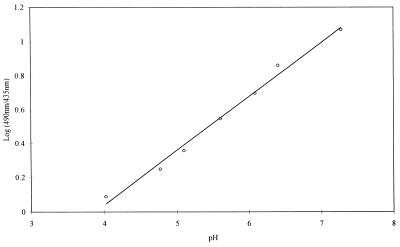

The 490 nm/435 nm ratios for individual cells were calibrated to pH values by using an in vitro calibration curve (Fig. 2). The calibration curve was prepared by using 10 μM fluorescein (catalog no. F-7505; Sigma) in PBS adjusted to various pH values with 2 N HCl and 2 N NaOH. The perfusion chamber was filled with the fluorescein solutions, and ratio imaging was performed as described above.

FIG. 2.

Relationship between the logarithm of the 490 nm/435 nm ratio and pH. The in vitro calibration curve was prepared by using 10 μM fluorescein in PBS adjusted to various pH values as described in Materials and Methods.

Calculation of the undissociated acetic acid concentrations during perfusion.

The concentrations of undissociated acetic acid in the perfusion solutions containing 2 g of total acetic acid per liter at pHex 3.5, 4.5, 5.6, and 6.5 were calculated by using the Henderson-Hasselbalch equation: pHex = pKa + log([Ac−]PS/[HAc]PS) and [HAc]PS + [Ac−]PS = [HAc]total,PS = 2 g/liter, where the pKa of acetic acid is 4.75 and [HAc]PS is the concentration of undissociated acetic acid in the perfusion solution.

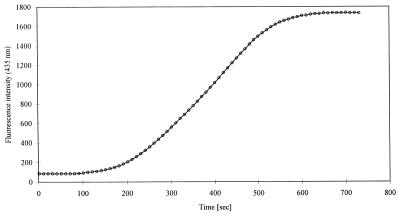

In order to calculate the concentration of undissociated acetic acid in the perfusion chamber at a given time during perfusion, the flow of perfusion solution through the chamber was characterized. This characterization was performed by using 5 μM fluorescein in PBS (pH 5.6). At a fluorescein concentration of 5 μM, artifacts, such as concentration quenching, were avoided; i.e., the fluorescence intensity was linearly correlated with the fluorescein concentration (data not shown). The chamber was filled with PBS (pH 5.6), and at time zero perfusion with 5 μM fluorescein in PBS (pH 5.6) was initiated at a rate of 0.6 μl/s. Emission signals from excitation at 435 nm were measured by using MetaFluor, version 2.0, software (Universal Imaging Corporation). The exposure time was 1,000 ms, and the 50% transmission neutral filter was omitted. Images were recorded from time zero of perfusion at 10-s intervals until the maximum fluorescence intensity was reached. The changes in fluorescence intensity in the chamber with time during perfusion are depicted in Fig. 3.

FIG. 3.

Characterization of the flow of perfusion solution through the perfusion chamber. The chamber was filled with PBS (pH 5.6). At time zero, perfusion with 5 μM fluorescein in PBS (pH 5.6) at a rate of 0.6 μl/s was initiated. Fluorescence intensity after excitation at 435 nm for 1,000 ms was measured as described in Materials and Methods.

The concentration of undissociated acetic acid in the chamber at a given time during perfusion was calculated by using the following equation: [HAc]T = [HAc]PS × [(I435,T − I435,min)/(I435,max − I435,min)], where [HAc]T is the concentration of undissociated acetic acid at time T, [HAc]PS is the concentration of undissociated acetic acid in the perfusion solution, I435,T is the fluorescence intensity after excitation at 435 nm at time T (Fig. 3), and I435,min and I435,max are the minimum and maximum fluorescence intensities, respectively, after excitation at 435 nm (Fig. 3).

RESULTS

Perfusion with PBS.

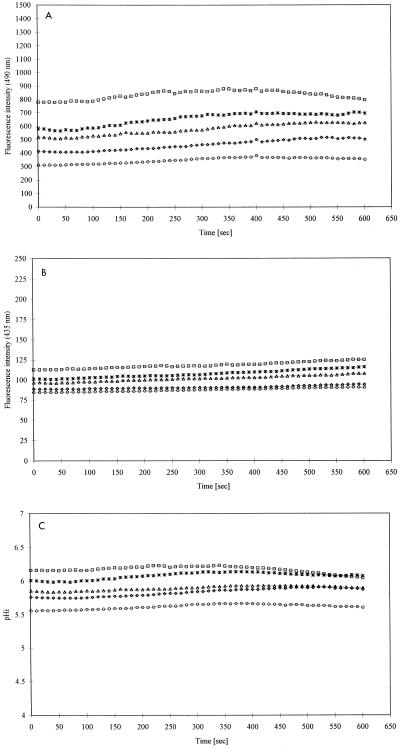

Efflux (2) and photobleaching (3) of fluorescein have previously been reported to occur in S. cerevisiae cells. In order to determine the influence of these potential artifacts on our results, stained S. cerevisiae cells were suspended in PBS at pHex 3.5, 4.5, 5.6, and 6.5 and perfused with PBS having the same pHex as the cell suspension. The fluorescence intensities after excitation at 490 and 435 nm of individual S. cerevisiae cells were not affected by perfusion with PBS at pHex 4.5 (Fig. 4A and B). The same results were observed at pHex 3.5, 5.6, and 6.5 (data not shown), indicating that the influence of efflux and photobleaching of fluorescein on our results could be ignored under the conditions used.

FIG. 4.

Fluorescence intensity after excitation at 490 nm (A) and 435 nm (B), and pHi (C) of five representative S. cerevisiae cells during perfusion with PBS (pHex 4.5) at a rate of 0.6 μl/s. Fluorescent staining of cells and ratio imaging were performed as described in Materials and Methods.

Moreover, the pHi of individual S. cerevisiae cells was not affected by perfusion with PBS at pHex 4.5 (Fig. 4C). The same results were observed at pHex 3.5, 5.6, and 6.5 (data not shown). Hence, any potential buffer interference could be ignored in the experiments performed with acetic acid in the perfusion solution.

The pHi values of individual S. cerevisiae cells ranging between 5.6 and 6.2 (Fig. 4C) are consistent with pHi values previously found for brewer’s yeast (6, 10–12, 18). Furthermore, the pHi values presented in Fig. 4C demonstrate that the asynchronous yeast population used in this study was highly heterogeneous with respect to pHi. These results agree with previously reported results obtained with asynchronous S. cerevisiae cultures (3, 6, 9).

Perfusion with undissociated acetic acid.

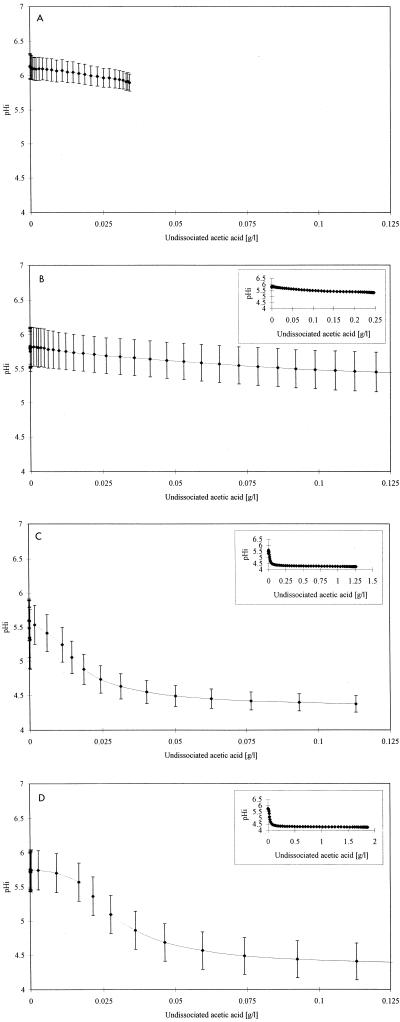

In order to determine the effects of acetic acid and pHex on the pHi of S. cerevisiae cells, stained cells were suspended in PBS at pHex 3.5, 4.5, 5.6, and 6.5 and perfused with 2 g of total acetic acid per liter in PBS having the same pHex as the cell suspension. During perfusion with 2 g of total acetic acid per liter at pHex 6.5, the average pHi of S. cerevisiae cells decreased from 6.2 to 5.9 as the extracellular concentration of undissociated acetic acid increased from 0 to 0.035 g/liter (Fig. 5A). During perfusion with 2 g of total acetic acid per liter at pHex 5.6, the average pHi of S. cerevisiae cells decreased from 5.8 to 5.4 as the extracellular concentration of undissociated acetic acid increased from 0 to 0.10 g/liter, and at concentrations of undissociated acetic acid higher than 0.10 g/liter, the pHi remained constant at 5.4 (Fig. 5B). During perfusion with 2 g of total acetic acid per liter at pHex 4.5 and 3.5, the average pHi of S. cerevisiae cells decreased from 5.6 to 4.4 as the extracellular concentration of undissociated acetic acid increased from 0 to 0.10 g/liter, and at concentrations of undissociated acetic acid higher than 0.10 g/liter, the pHi remained constant at 4.4 (Fig. 5C and D). The decreases in the pHi values of individual S. cerevisiae cells at pHex 5.6 and 6.5 were smaller than the decreases in the pHi values at pHex 3.5 and 4.5 (0.3 to 0.4 and 1.2 pH units, respectively) (Fig. 5).

FIG. 5.

Relationship between pHi of individual S. cerevisiae cells and extracellular concentration of undissociated acetic acid. The cells were perfused with 2 g of total acetic acid per liter in PBS at pHex 6.5 (A), pHex 5.6 (B), pHex 4.5 (C) and pHex 3.5 (D) at a rate of 0.6 μl/s. The pHi values presented are averages from 20 to 30 randomly selected cells. The calculated standard deviations are shown by error bars. The insets show the relationship between pHi and the full range of extracellular concentrations of undissociated acetic acid used in the experiments. The time intervals between data points are 20 s (A) (for clarity) and 10 s (B through D). Fluorescent staining of cells, ratio imaging, and calculation of the undissociated acetic acid concentrations during perfusion were performed as described in Materials and Methods.

DISCUSSION

In this study we investigated the effect of acetic acid on the pHi of individual S. cerevisiae cells at various pHex values by using a new experimental setup comprising a fluorescence microscope and a perfusion system (Fig. 1). The extracellular concentration of undissociated acetic acid at various pHex values was controlled by perfusing 2 g of total acetic acid per liter at pHex 3.5, 4.5, 5.6, and 6.5 through a perfusion chamber by using a high-precision pump, and the pHi values of individual S. cerevisiae cells during perfusion were measured by fluorescence microscopy and ratio imaging.

The results reported in this study demonstrate that at pHex 3.5, 4.5, and 5.6 the pHi values of individual S. cerevisiae cells decreased as the concentration of undissociated acetic acid increased from 0 to 0.10 g/liter (Fig. 5). At concentrations of undissociated acetic acid higher than 0.10 g/liter the pHi remained constant (Fig. 5). These results agree with the results reported by Warth (21) obtained with benzoic acid, which showed that the pHi of S. cerevisiae decreased as the benzoic acid concentration increased from 0 to 0.13 g/liter and that at benzoic acid concentrations higher than 0.13 g/liter the pHi remained constant. Our finding that the pHi of individual S. cerevisiae cells remains constant at concentrations of undissociated acetic acid higher than 0.10 g/liter may be explained by the presence of a constant level of accumulated acetic acid in S. cerevisiae, as suggested previously for benzoic acid (21). Alternatively, the plasma membrane ATPase activity of S. cerevisiae may be activated at concentrations of undissociated acetic acid higher than 0.10 g/liter. This should result in an increased efflux of protons, thereby compensating for the acidification of the cytosol. In the present study, however, the experiments were carried out without glucose or any other energy source; i.e., the ATP pools within the cells may have been depleted, and the plasma membrane ATPase may not have functioned.

Pampulha and Loureiro-Dias (15) found that acetic acid-induced decreases in the pHi in S. cerevisiae depend exclusively on the extracellular concentration of undissociated acetic acid and are independent of the pHex. These results are not consistent with our results which show that the decreases in pHi induced by undissociated acetic acid are dependent on the pHex. The difference between the results may be explained by the different experimental approaches used. Pampulha and Loureiro-Dias (15) investigated the effects of acetic acid and pHex on the pHi of S. cerevisiae by using the distribution of radioactively labelled propionic acid to measure the pHi. In this technique (i) impermeability of the anion of acetic acid is assumed (22), (ii) cells are incubated for 85 min in the presence of undissociated acetic acid, and (iii) cell suspensions are used. With our technique (i) no assumptions concerning impermeability of the anion of acetic acid have to be made, (ii) measurements are carried out at 10-s intervals, and (iii) the pHi of individual cells is measured. Furthermore, Pampulha and Loureiro-Dias (15) studied fermenting S. cerevisiae cells, whereas we studied nonfermenting cells.

The fact that the pHex affects acetic acid-induced decreases in pHi in S. cerevisiae (Fig. 5) indicates that the mechanisms underlying these decreases in pHi may be sensitive to pHex. The pHex-sensitive mechanisms may include plasma membrane permeability to undissociated acetic acid, which has been reported to decrease in S. cerevisiae with decreasing pHex (4, 5), and the buffering capacity of the cytosol, which for Zygosaccharomyces bailii has been reported to increase with decreasing pHex (7). The results obtained in this work, however, are opposite the results which could be anticipated from the mechanisms mentioned above; i.e., the pHi is lower at low pHex values compared with high pHex values (Fig. 5), whereas it should be higher due to a lower passive diffusion rate of undissociated acetic acid (4, 5) and a higher buffering capacity of the cytosol (7). Our results cannot be explained by plasma membrane permeability to undissociated acetic acid and the buffering capacity of the cytosol. Thus, this subject needs further investigation.

In conclusion, our results show that at pHex 3.5, 4.5, and 5.6 the pHi values of individual S. cerevisiae cells decrease as the concentration of undissociated acetic acid increases from 0 to 0.10 g/liter. At concentrations of undissociated acetic acid higher than 0.10 g/liter the pHi remains constant. Furthermore, our results demonstrate that the decreases in pHi strongly depend on the pHex. In future experiments we will attempt to elucidate the mechanisms underlying the changes in the pHi values of S. cerevisiae cells induced by undissociated acetic acid.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was financially supported by Alfred Jørgensen Laboratory Ltd., Copenhagen, Denmark, and by the FØTEK program sponsored by the Danish Ministry of Research through the LMC-Centre for Advanced Food Studies.

REFERENCES

- 1.Arneborg N, Moos M, Jakobsen M. The effect of acetic acid and specific growth rate on acetic acid tolerance and trehalose content of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Biotechnol Lett. 1995;17:1299–1304. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Breeuwer P, Drocourt J-L, Rombouts F M, Abee T. Energy-dependent, carrier-mediated extrusion of carboxyfluorescein from Saccharomyces cerevisiae allows rapid assessment of cell viability by flow cytometry. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1994;60:1467–1472. doi: 10.1128/aem.60.5.1467-1472.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Breeuwer P, Drocourt J-L, Bunschoten N, Zwietering M H, Rombouts F M, Abee T. Characterization of uptake and hydrolysis of fluorescein diacetate and carboxyfluorescein diacetate by intracellular esterases in Saccharomyces cerevisiae, which result in accumulation of fluorescent product. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1995;61:1614–1619. doi: 10.1128/aem.61.4.1614-1619.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Casal M, Cardoso H, Leão C. Mechanisms regulating the transport of acetic acid in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Microbiology. 1996;142:1385–1390. doi: 10.1099/13500872-142-6-1385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cássio F, Leão C, van Uden N. Transport of lactate and other short-chain monocarboxylates in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1987;53:509–513. doi: 10.1128/aem.53.3.509-513.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cimprich P, Slavik J, Kotyk A. Distribution of individual cytoplasmic pH values in a population of the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1995;130:245–252. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1995.tb07727.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cole M B, Keenan M H J. Effects of weak acids and external pH on the intracellular pH of Zygosaccharomyces bailii, and its implications in weak-acid resistance. Yeast. 1987;3:23–32. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Enari, T.-M. 1995. One hundred years of brewing research. J. Inst. Brew. Centennial Edition:16–18.

- 9.Hernlem B J, Srienc F. Intracellular pH in single Saccharomyces cerevisiae cells. Biotechnol Tech. 1989;3:79–84. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Imai T, Nakajima I, Ohno T. Development of a new method for evaluation of yeast vitality by measuring intracellular pH. J Am Soc Brew Chem. 1994;52:5–8. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Imai T, Ohno T. The relationship between viability and intracellular pH in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1995;61:3604–3608. doi: 10.1128/aem.61.10.3604-3608.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Imai T, Ohno T. Measurement of yeast intracellular pH by image processing and the change it undergoes during growth phase. J Biotechnol. 1995;38:165–172. doi: 10.1016/0168-1656(94)00130-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lafon-Lafourcade S. Wine and brandy. Bio/Technology. 1983;5:81–163. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Maiorella B, Blanch H W, Wilke C R. By-product inhibition effects on ethanolic fermentation by Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Biotechnol Bioeng. 1983;25:103–121. doi: 10.1002/bit.260250109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pampulha M E, Loureiro-Dias M C. Combined effect of acetic acid, pH and ethanol on intracellular pH of fermenting yeast. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 1989;31:547–550. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Phowchinda O, Délia-Dupuy M L, Strehaiano P. Effects of acetic acid on growth and fermentative activity of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Biotechnol Lett. 1995;17:237–242. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rabinovitch P S, June C H. Intracellular ionized calcium, magnesium, membrane potential, and pH. In: Ormerod M G, editor. Flow cytometry. A practical approach. 2nd ed. Oxford, United Kingdom: Oxford University Press; 1994. pp. 208–213. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rowe S M, Simpson W J, Hammond J R M. Intracellular pH of yeast during brewery fermentation. Lett Appl Microbiol. 1994;18:135–137. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Slavik J. Intracellular pH of yeast cells measured with fluorescent probes. FEBS Lett. 1982;140:22–26. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(82)80512-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Verduyn C, Postma E, Scheffers W A, van Dijken J P. Physiology of Saccharomyces cerevisiae in anaerobic glucose-limited chemostat cultures. J Gen Microbiol. 1990;136:395–403. doi: 10.1099/00221287-136-3-395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Warth A D. Effect of benzoic acid on glycolytic metabolite levels and intracellular pH in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1991;57:3415–3417. doi: 10.1128/aem.57.12.3415-3417.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Warth A D. Mechanism of action of benzoic acid on Zygosaccharomyces bailii: effects on glycolytic metabolite levels, energy production, and intracellular pH. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1991;57:3410–3414. doi: 10.1128/aem.57.12.3410-3414.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]