Abstract

Bacteria with limited genomic cross-hybridization were isolated from soil contaminated with C5+, a mixture of hydrocarbons, and identified by partial 16S rRNA sequencing. Filters containing denatured genomic DNAs were used in a reverse sample genome probe (RSGP) procedure for analysis of the effect of an easily degradable compound (toluene) and a highly recalcitrant compound (dicyclopentadiene [DCPD]) on community composition. Hybridization with labeled total-community DNA isolated from soil exposed to toluene indicated enrichment of several Pseudomonas spp., which were subsequently found to be capable of toluene mineralization. Hybridization with labeled total-community DNA isolated from soil exposed to DCPD indicated enrichment of a Pseudomonas sp. or a Sphingomonas sp. These two bacteria appeared capable of producing oxygenated DCPD derivatives in the soil environment, but mineralization could not be shown. These results demonstrate that bacteria, which metabolize degradable or recalcitrant hydrocarbons, can be identified by the RSGP procedure.

Unsaturated hydrocarbons are obtained as by-products in the pyrolysis of ethane to ethylene. These higher-molecular-weight products collect at the bottom of the quench tower of an ethane pyrolysis plant and are referred to as the C5+ stream. C5+ contains benzene, cyclopentadiene, dicyclopentadiene (DCPD), ethylbenzene, styrene, toluene, and xylenes as major components and many other hydrocarbons as minor components. It is further processed to obtain the pure components; e.g., pure DCPD is used for polymer production. As a result of transport and handling, accidental releases of C5+ occur at pyrolysis plant sites. It was shown recently (18) that the bioremediation of C5+-contaminated soil is characterized by rapid removal of more easily degradable BTEX (benzene, toluene, ethylbenzene, and xylene) components followed by the much slower removal of cyclopentadiene, DCPD, and higher-molecular-weight hydrocarbons (C11+).

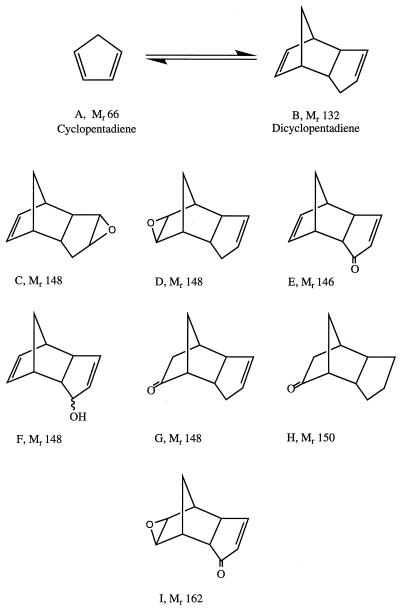

Bacteria capable of mineralizing the BTEX components of the C5+ stream are readily isolated from contaminated soil, but microorganisms capable of DCPD mineralization have not been found (17). Similarly, the pathways by which BTEX components are metabolized are generally known (5, 30) whereas the pathway for DCPD degradation is not. Laboratory experiments have shown that soil microbial communities convert some [14C]DCPD into 14CO2 while forming larger amounts of oxygenated derivatives as identified by gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS) (17). van Breemen et al. (23) found two monooxygenated DCPD derivatives in contaminated groundwater in which oxygen was incorporated at position 8 of the DCPD carbon skeleton (Fig. 1E and F), while Stehmeier et al. (17) demonstrated incorporation at position 3 (Fig. 1G and H). All of these are distinct from the epoxides (Fig. 1C and D) formed by rabbit liver cytochromes P-450 (23). The recalcitrance of DCPD in the environment is of concern primarily because of its pungent smell (2). The human perception of the success of a remediation effort at sites where C5+ spills have occurred is therefore determined largely by the concentration of residual DCPD.

FIG. 1.

Structures of DCPD and several oxidized derivatives. (A and B) DCPD (B) can be formed from cyclopentadiene (A) by a reversible reaction at room temperature. Incubation at higher temperature results in further polymerization. (C to H) Structures of six mono-oxygenated DCPD derivatives. (I) Structure of a dioxygenated DCPD derivative.

The objective of this study was to determine whether reverse sample genome probing (RSGP), a technique that is suitable for monitoring the response of environmental microbial communities to chemical changes (19), can be used to identify the response of a soil microbial community to the introduction of unsaturated hydrocarbons. Bacteria enriched in the presence of a metabolizable compound (toluene) or a recalcitrant compound (DCPD) were tested for their ability to oxidize these substrates.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Biochemical reagents.

Radioisotopes α-35S-dATP (10 mCi/ml; 400 Ci/mmol [Amersham]) and [α-32P]dCTP (10 mCi/ml; 3,000 Ci/mmol [ICN]) were used. Reagent-grade chemicals were from BDH, Fisher, or Sigma, and enzymes and bacteriophage λ DNA (0.5 mg/ml) were obtained from Pharmacia. Polyvinylpolypyrrolidone (PVPP) was from Sigma, and the Hybond-N hybridization transfer membrane was from Amersham.

Culture media.

Hydrocarbon degradation medium (HDM) and tryptone yeast extract (TY) medium were as described previously (17, 29). Minimal salts medium for studies of hydrocarbon degradation in soil contained 4 g of NaNO3, 1.5 g of KH2PO4, 0.5 g of Na2HPO4, 0.0011 g of FeSO4 · 7H2O, 0.2 g of MgSO4 · 7H2O, and 0.01 g of CaCl2 per liter of water at pH 7.0. PTYG medium contained 1 g of tryptone, 2 g of yeast extract, 2 g of glucose, 0.6 g of MgSO4 · 7H2O, and 0.07 g of CaCl2 · 2H2O per liter of water. Liquid medium C and plating medium E for the growth of sulfate reducers were as formulated by Postgate (13).

Isolation and characterization of soil bacteria.

Members of the microbial community in C5+-contaminated soil were obtained by being grown at room temperature (22°C) on the media listed in Table 1. The set in Table 1 had limited cross-hybridization of genomic DNAs. Species with little or no genomic cross-hybridization under stringent conditions have been referred to as standards in earlier work (19, 20, 25–28). Higher degrees of cross-hybridization (up to 30%) were found in the present study for genomes from Pseudomonas species. Standards 1 to 20 and 22 to 24 were isolated from C5+-contaminated soil under aerobic conditions by streaking for single colonies on PTYG medium. Restreaked, isolated colonies were grown in 5 ml of PTYG medium, which was used to inoculate 300 ml of medium in 500-ml Erlenmeyer flasks shaken at 150 rpm. Following growth to stationary phase, cells were harvested by centrifugation, frozen at −70°C, and used for DNA preparation. Glycerol stocks of all cultures were also kept at −70°C.

TABLE 1.

Composition of the soil master filter

| Positiona | Nameb | Mediumc | Sabd | Nearest homologe | cf | kλ/kxg | ςh |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | LQ1 | PTYG | 0.802 | Bordetella bronchiseptica | 164 | 238 | 20 |

| 2 | LQ5 | PTYG | 0.375 | Pseudomonas syringae | 156 | 180 | 10 |

| 3 | LQ6 | PTYG | 0.396 | Azospirillum sp. | 200 | 283 | 4 |

| 4 | LQ10 | PTYG | 0.598 | Sphingomonas parapaucimobilis | 110 | 112 | 11 |

| 5 | LQ11 | PTYG | 0.769 | Bacillus macroides | 148 | 46 | 2 |

| 6 | LQ14 | PTYG | 0.615 | Xanthomonas campestris | 132 | 61 | 12 |

| 7 | LQ15 | PTYG | 0.580 | Bacillus pseudomegaterium | 116 | 68 | 24 |

| 8 | LQ16 | PTYG | 0.861 | Pseudomonas syringae | 176 | 95 | 1 |

| 9 | LQ17 | PTYG | 0.931 | Agrobacterium rubi | 152 | 112 | 5 |

| 10 | LQ19 | PTYG | 0.349 | “Flavobacterium” lutescens | 152 | 157 | 14 |

| 11 | LQ20 | PTYG | 0.816 | Pseudomonas syringae | 156 | 210 | 30 |

| 12 | LQ21 | PTYG | 0.791 | Bordetella parapertussis | 148 | 294 | 0 |

| 13 | LQ26 | PTYG | 0.865 | Bordetella parapertussis | 130 | 166 | 25 |

| 14 | LQ27 | PTYG | (Bordetella sp.)i | 130 | 149 | 36 | |

| 15 | LQ29 | PTYG | 0.843 | Bordetella parapertussis | 152 | 208 | 32 |

| 16 | LQ30 | PTYG | 0.935 | Sphingomonas yanoikuyae | 140 | 200 | 5 |

| 17 | LQ33 | PTYG | NDj | 180 | 249 | 14 | |

| 18 | LQ34 | PTYG | 0.969 | Pseudomonas flavescens | 138 | 170 | 13 |

| 19 | LQ35 | PTYG | 0.972 | Pseudomonas flavescens | 148 | 160 | 6 |

| 20 | LQ36 | PTYG | 0.965 | Pseudomonas flavescens | 136 | 109 | 6 |

| 21 | Q1 | HDM, benzene | 0.851 | Rhodococcus sp. | 172 | 574 | 98 |

| 22 | Q2 | PTYG | 0.879 | Bacillus cereus/thuringiensis | 148 | 60 | 6 |

| 23 | Q3 | PTYG | 0.763 | Nocardioides luteus | 184 | 330 | 32 |

| 24 | Q4 | PTYG | 0.683 | Flavobacterium ferrugineum | 160 | 93 | 10 |

| 25 | Q5 | HDM, naphthalene | 0.779 | Pseudomonas syringae | 160 | 142 | 4 |

| 26 | Q6 | HDM, styrene | 0.836 | Rhodococcus globerulus | 116 | 202 | 5 |

| 27 | Q7 | TY | 0.741 | Pseudomonas syringae | 172 | 151 | 12 |

| 28 | Q8 | TY | 0.879 | Bacillus benzoevorans | 148 | 51 | 7 |

| 29 | Q9 | TY | 0.809 | Bacillus polymyxa | 146 | 73 | 7 |

| 30 | Q10 | TY, anoxic | 0.504 | Bacteroides distasonis | 146 | 72 | 10 |

| 31 | Q11 | TY, anoxic | 0.498 | Bacteroides heparinolyticus | 240 | 80 | 8 |

| 32 | Q12 | TY, anoxic | 0.846 | Clostridium xylanolyticum | 152 | 65 | 6 |

| 33 | Q13 | TY, anoxic | 0.337 | Clostridium sp. | 128 | 61 | 17 |

| 34 | Q14 | Medium C, anoxic | 0.582 | Desulfovibrio longus | 172 | 127 | 6 |

| 35 | Q15 | Medium C, anoxic | 0.571 | Desulfovibrio desulfuricans | 146 | 94 | 8 |

Position of denatured chromosomal DNA on master filter.

Name assigned at time of isolation.

Medium used for isolation. Standards 1 to 29 were isolated under aerobic conditions.

Similarity coefficient for query and matching sequences (10).

Nearest homolog in the RDP database as determined by the program SIMILARITY_RANK (10).

Amount of denatured chromosomal DNA (ng) spotted on the filter.

Ratio of hybridization constants for bacteriophage λ and genomic DNA (x) from equation 2 (19).

Average deviation between duplicate measurements of kλ/kx.

Inferred from cross-hybridization with other Bordetella sp. genomes on the filter.

ND, not determined.

Standards 21, 25, and 26 (Table 1) were isolated on aerobic HDM plates incubated in an atmosphere of benzene, naphthalene, or styrene, respectively, by M. M. Francis, NOVA Research & Technology Corp., Calgary, Canada. Cells for DNA isolation were obtained from 1-liter cultures in HDM in which these hydrocarbons served as the sole carbon and energy source. Standards 27 to 29 were isolated on aerobic TY plates, while standards 30 to 33 were obtained on TY plates under anoxic conditions in a 5% H2–10% CO2–85% N2 gas atmosphere. Two Desulfovibrio species (Table 1, standards 34 and 35) were obtained on medium E plates (13), and single colonies were grown on liquid medium C (13).

The colony morphology and cellular morphology of isolated bacteria were recorded for future reference by using descriptors and microscopy procedures defined elsewhere (6).

DNA isolation.

DNA was extracted from cells by the Marmur method (11) modified as described elsewhere (25) and also including three cycles of freezing and thawing (22) for better cell lysis. Final preparations were dissolved in TE (10 mM Tris-HCl, 0.1 mM EDTA [pH 8]).

DNA was isolated from soil by a modification of the technique described by Bakken (3). Soil samples (5 to 20 g) were combined with acid-washed PVPP, suspended in 0.1% (wt/vol) sodium pyrophosphate, and homogenized by stirring for 20 min. The soil particles and acid-washed PVPP were removed by centrifugation at 1,000 × g for 10 min at 4°C. The soil extraction was repeated twice, and the combined supernatants were centrifuged at 15,000 × g for 20 min at 4°C to collect the bacteria. The pellet was resuspended in 0.15 M NaCl–0.1 M EDTA (pH 8.0) and used for DNA isolation by the modified Marmur method. Agarose gel electrophoresis was used as an additional, final purification step to obtain DNA free from humic acids.

RSGP.

The concentrations of selected DNA preparations were adjusted to ca. 70 ng/μl by a fluorimetric method (27), and 2 μl of each denatured DNA preparation was spotted on Hybond-N hybridization membrane filters. The exact amounts of DNAs on the filter are listed in Table 1. Denatured bacteriophage λ DNA was spotted at 10, 20, 40, 60, 80, 100, 200, and 400 ng in the bottom row of each filter. The filters were dried and baked for 10 min at 80°C in a vacuum oven, after which the DNAs were further cross-linked to the filter by UV irradiation as described elsewhere (26, 27). For probe preparation, 100 ng of purified chromosomal DNA (e.g., as obtained from a single standard or from a soil sample), 0.1 ng of λ DNA, 6 μl of primer extension mix containing random hexadeoxyoligonucleotides (26), 2 μl of Klenow polymerase (2 U/μl), and 2 μl of [α-32P]dCTP were combined in a total volume of 30 μl. Following reaction at room temperature for at least 3 h, during which all of the label was incorporated, the probes were boiled and then hybridized to the filters at 68°C under highly stringent conditions (29). Following washing and drying, the dot blots were exposed to BAS-III imaging plates, which were scanned with a Fuji BAS1000 bioimaging analyzer. Net hybridization intensities for all dots (Ix and Iλ) were determined in units of photostimulable luminescence (ΔPSL) by subtracting a local background. The fractions fx of all genomes were calculated from the hybridization data as described previously (19). Relative hybridization constants (kλ/kx) were determined for all standards by hybridizing labeled, single genomic DNAs in duplicate (19), and the average values derived for each genome (Table 1) were used for calculation of fx. The degree of cross-hybridization between the chromosomal DNAs of all 35 standards was also derived from these experiments. As in the previous study (19), the hybridization intensities observed for the internal standard bacteriophage λ DNA (Iλ) increased linearly with cλ, the amount of denatured λ DNA spotted on the filter, for low concentrations only. Iλ/cλ values obtained for the range from 10 to 60 ng were averaged for all calculations. The calculated fx values can be subject to systematic errors (19), but this tends to affect all values equally. The general appearance of bar diagrams (plots of fx against standard number) was reproducible in duplicate incubations.

Identification by 16S rDNA sequencing.

A partial 16S rRNA gene sequence was determined for all of the standards listed in Table 1. The 16S rRNA genes were amplified by PCR with primers f8 (12) and r1406 (9), as explained elsewhere (19). The PCR products were sequenced directly with the Promega fmol cycle-sequencing system, with EUB388 (1) or primer P76 (GCCAGC[A/C]GCCGCGGT) targeting conserved regions of the 16S rRNA (positions 338 to 356 and 517 to 531, respectively [Escherichia coli numbering]). The best-matching sequence in the Ribosomal Database Project (RDP) database was then identified with the program SIMILARITY_RANK (10).

Soil incubations.

Soil was obtained from either the northwestern (NW) or the northeastern (NE) end of a soil pile constructed for a C5+ bioremediation project at an ethane pyrolysis plant. This soil had ca. 70 μg of DCPD/g and 70 μg of BTEX/g at the start and 30 μg of DCPD/g and 0 μg of BTEX/g at the conclusion of the bioremediation project (18). The NW side of the pile received nutrients and bulking agents, while the NE side was an unamended control. The soils were stored at 4°C in the dark. Soil samples (10 g) were placed in sterile 100-ml glass beakers loosely covered with aluminum foil. After the addition of 10 ml of sterile minimal salts, the beakers were placed in glass desiccators containing a saturated atmosphere of either DCPD and H2O, toluene and H2O, or H2O only. The desiccators were incubated at room temperature in the dark for 4 to 8 weeks. The soil-medium mixture was then centrifuged for 10 min at 10,000 × g. The soil-cell pellet was extracted with 0.1% (wt/vol) sodium pyrophosphate containing acid-washed PVPP for DNA isolation.

For studying DCPD degradation by specific strains, steam-sterilized soil (10 g) and 10 ml of minimal salts were inoculated with 10 to 20 μl of a culture grown to saturation in TY medium. Following incubation in a DCPD- and H2O-saturated atmosphere for 4 to 8 weeks and centrifugation, the soil-cell pellet was extracted for DNA isolation. The supernatant was saturated with sodium chloride and extracted three times with a total volume of 45 ml of ethyl acetate. Extracts were combined and concentrated in a rotary evaporator. The yield of these extractions was in excess of 80%. For quantitative analysis of oxygenated DCPD derivatives, the concentrated ethyl acetate extracts (ca. 0.5 ml) were dried with a stream of nitrogen and redissolved in 0.2 ml of dichloromethane containing 20 μg of p-dichlorobenzene as the internal standard.

GC and GC-MS analysis.

GC-MS and capillary GC analyses were performed with a Hewlett Packard 5890 gas chromatograph/mass spectrometer (Hewlett Packard 5971A mass selective detector) equipped with either a liquid-phase DB-1701 fused-silica capillary column (30 m by 0.25 μm) for GC-MS or an OV-1 fused-methyl-silica column (15 m by 0.32 μm) for capillary GC. The injector temperature was 220°C, and the gas chromatograph oven temperature was programmed for 2 min at 60°C and then run from 60 to 250°C at 10°C/min. The flame ionization detector temperature was 250°C. For each run, 1 μl of concentrated sample was injected directly into the gas chromatograph/mass spectrometer. The MS spectra were compared with those published previously (17, 23, 24).

Mineralization of [14C]DCPD and [14C]toluene.

Mineralization studies were carried out essentially as described by Bazylinski et al. (4). Steam-sterilized soil (1 g), 5 ml of mineral salts medium, 10 μl of uniformly labeled [14C]DCPD (2 μl of 0.15 μCi/μl diluted with 8 μl of cold DCPD), and 10 μl of a culture grown to saturation in TY medium were combined in a 20-ml ampoule, which was then sealed. Following incubation for 4 weeks, the ampoule was connected in series to two test tubes containing 10 ml of 0.6 M KOH each. The ampoule seal was then broken, and 1 ml of 1 M HCl was added. [14C]CO2 was transferred to the KOH trap for 30 min via a gentle stream of nitrogen. The contents of the test tubes were placed in two scintillation vials, mixed with 5 ml of EcoLite scintillation fluid (ICN), and counted with an LKB 1215 RACKBETA liquid scintillation counter for 2 min. The values observed in control experiments without inoculum were subtracted from the counts obtained. [14C]toluene (2 μl of 0.06 μCi/μl, diluted with 8 μl of cold toluene) was used for toluene mineralization studies. Nonsterilized soils without an added inoculum were also used in some experiments.

RESULTS

Characterization of isolated bacterial standards.

Bacteria were isolated from contaminated soil with the media indicated in Table 1. A minimal set was obtained by eliminating species with strong genomic cross-hybridization in dot blots. The 35 selected standards are listed in Table 1 in the order in which they were spotted on the master filter. Partial sequencing of PCR-amplified rRNA genes and comparison of the sequences obtained with those in the RDP database allowed identification of 33 standards (Table 1). Identifications with low values for the similarity coefficient Sab (10) are unlikely to be significant beyond the genus level. The genus Pseudomonas was most prevalent among the aerobes. Five standards had Pseudomonas syringae and three had Pseudomonas flavescens as the closest RDP homolog (Table 1). The genera Bacillus and Bordetella were also well represented, with five and four standards, respectively. Six anaerobic isolates included two Bacteroides spp., two Clostridium spp., and two Desulfovibrio spp. (Table 1).

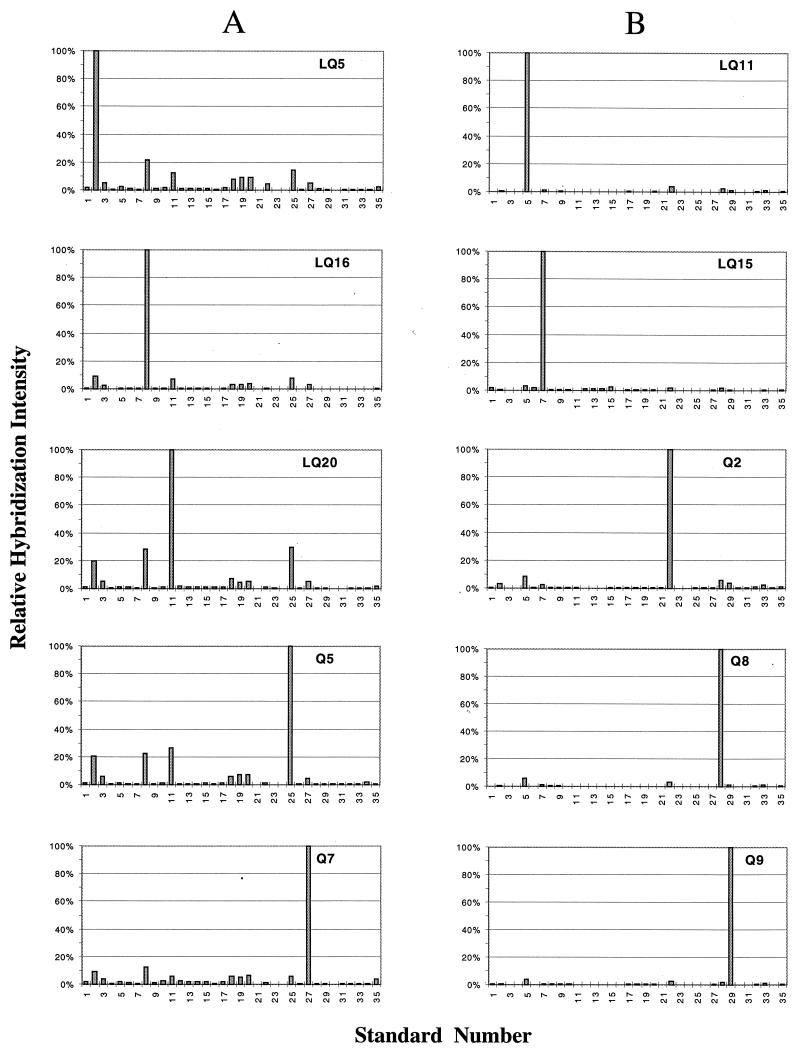

Two hundred master filters were made by spotting 2-μl volumes of denatured genomic DNA for all 35 standards. The amounts of DNA applied to the filters are listed in Table 1. Seventy of these were used for duplicate hybridizations with labeled chromosomal DNA (spiked with λ) from each of the 35 represented standards. The results for five of the six P. syringae homologs and for the five Bacillus homologs are shown in Fig. 2. These experiments allowed the cross-hybridization as well as the ratio kλ/kx to be evaluated. The average kλ/kx values are listed in Table 1. The P. syringae genomes had substantial degrees of cross-hybridization of up to 30% (Fig. 2A, standards 2, 8, 11, 25, and 27). These also cross-hybridized at a level of 5 to 10% with three genomes that had P. flavescens as the closest RDP homolog (Fig. 2A, standards 18, 19, and 20). Cross-hybridization with standards assigned to other genera by 16S rRNA sequencing was generally below 2%. The five Bacillus genomes displayed lower (<5%) degrees of cross-hybridization with each other (Fig. 2B).

FIG. 2.

Hybridization of soil community master filters with single genomic DNAs. The hybridization intensity (corrected for background) relative to that observed for the genome used as a probe (100%) is plotted against standard number in the same order as in Table 1. The patterns shown are means of duplicate hybridizations. (A) Patterns for standards 2, 8, 11, 25, and 28, which all have P. syringae as the nearest RDP homolog. (B) Patterns for standards 5, 7, 22, 28, and 29, which all have a Bacillus sp. as the nearest RDP homolog.

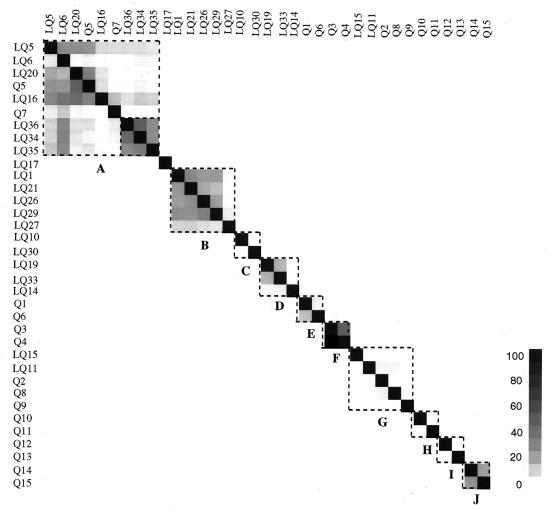

Cross-hybridization data for all 35 genomes are displayed in a matrix in Fig. 3, which has been rearranged to group phylogenetically related genomes. Strong cross-hybridizations occur only within the drawn squares, indicating a correlation between 16S rRNA-derived phylogeny and the degree of cross-hybridization. Low degrees of cross-hybridization for species within the same genus were observed for the genera Sphingomonas, Bacteroides, and Clostridium, in addition to the genus Bacillus (Fig. 2). The cross-hybridization data can be used to correct RSGP hybridization patterns of synthetic microcosms, as discussed elsewhere (19).

FIG. 3.

Cross-hybridization matrix. Hybridization data, as in Fig. 2, were arranged as columns in a matrix. The order of columns and corresponding rows was changed to bring genomes with similar 16S rRNA phylogeny in close proximity. The enclosed squares represent Pseudomonas spp. (P. flavescens inside and P. syringae outside the smaller square) (A), Bordetella spp. (B), Sphingomonas spp. (C), various (D), Rhodococcus spp. (E), various (element Q3/Q4 is anomalously high) (F), Bacillus spp. (G), Bacteroides spp. (H), Clostridium spp. (I), and Desulfovibrio spp. (J).

Extraction of DNA from soil.

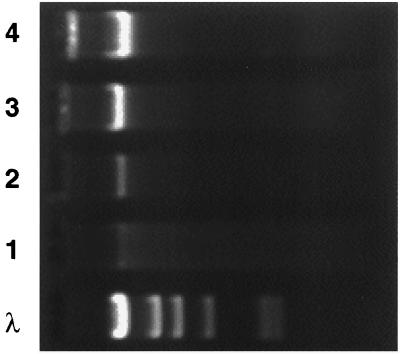

Soils obtained from either the NW or the NE end of a C5+-contaminated pile were incubated with DCPD or toluene, two significant components of the C5+ mixture. An agarose gel of DNAs extracted from NW soil samples is shown in Fig. 4. Incubation in mineral salts increased the amount of extracted DNA (Fig. 4, lanes 1 and 2) from 0.06 to 0.12 μg/g of soil. Incubation in a DCPD or toluene atmosphere further increased the extracted amounts of DNA (lanes 3 and 4) from 0.25 to 0.5 μg/g. The extraction efficiency was estimated to be 20% by measuring the amount of DNA obtained from sterilized soil to which a known volume of a bacterial culture was added. Importantly, if subsequently extracted DNA fractions were analyzed by RSGP, identical community profiles were obtained, indicating that these results were not affected by the extraction yield.

FIG. 4.

Agarose gel electrophoresis of community DNA extracted from soil. Soil was incubated for 4 weeks at room temperature with 10 ml of minimal salts medium in an atmosphere saturated with water (lane 2), water and DCPD (lane 3), or water and toluene (lane 4). Extracted DNAs were electrophoresed through agarose. Lane 1 represents DNA extracted from soil prior to incubation; lane λ represents size markers (bacteriophage λ DNA restricted with HindIII; from left to right, 23.1, 9.4, 6.6, 4.4, 2.3, and 2.0 kb).

Effects of toluene.

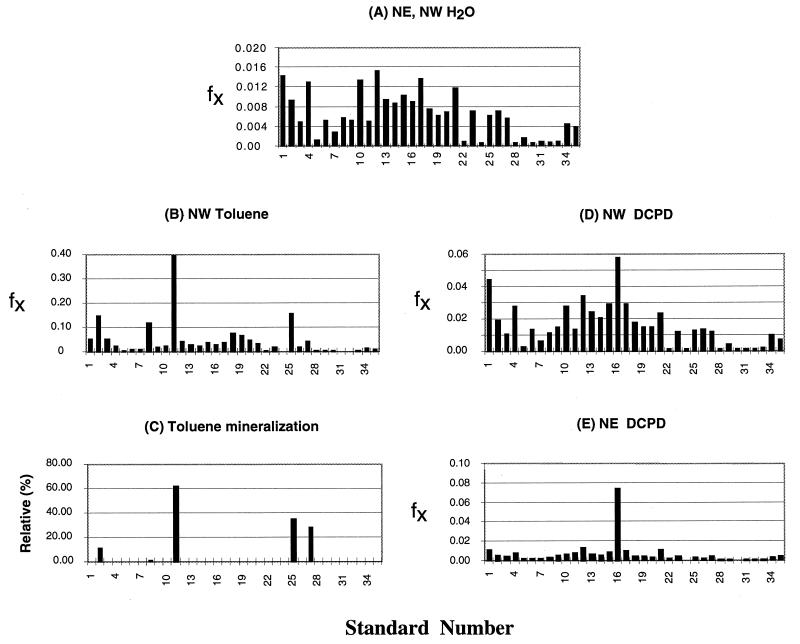

The community profiles for NE and NW soil samples incubated with minimal salts medium only were very similar. The averaged profile in Fig. 5A shows a broad population distribution with calculated fx values from 0.001 to 0.015. Incubation in the presence of toluene led to a significant shift in the community profile. A limited number of standards became enriched by an order of magnitude, as shown for the NW soil sample in Fig. 5B. Standard 11 (Pseudomonas strain LQ20) was the dominant community member. Standards 2, 8, 25, and 27 have the same RDP homolog as standard 11 (Table 1, P. syringae). The peaks for these standards in Fig. 5B are therefore caused in part by cross-hybridization with the LQ20 genome, as may be seen by comparison with the hybridization pattern for pure LQ20 in Fig. 2A. To establish whether LQ20 and the other four P. syringae homologs could metabolize toluene, the formation of [14C]CO2 from uniformly labeled [14C]toluene was investigated. When [14C]toluene was incubated with the NW soil sample and minimal salts for 4 weeks, 4 to 10% of the label was recovered from the alkali traps as [14C]CO2. The mineralization activity of individual standards, inoculated into sterilized soil and minimal salts medium containing [14C]toluene, relative to the soil consortium is indicated in Fig. 5C. Pseudomonas strain LQ20 was the most active of five standards tested (LQ5, LQ16, LQ20, Q5, and Q7).

FIG. 5.

RSGP of community DNAs from soils at the NE or NW side of a contaminated soil pile. (A) Soils were incubated with minimal salts medium only. The pattern shown is an average for NE and NW soils. (B) NW soil sample incubated with minimal salts medium in a toluene atmosphere. (C) Percent toluene mineralization by individual species relative to mineralization by the NW soil community. Data are plotted for Pseudomonas sp. standards 2, 8, 11, 25, and 27. (D and E) NW and NE soils, respectively, were incubated with minimal salts medium in a DCPD atmosphere. The fraction of each standard (fx) is plotted against standard number in panels A, B, D, and E.

Effects of DCPD.

Exposure to DCPD also led to significant changes in the community profile, which were distinctly different from those observed for toluene. Standard 16 (LQ30, with Sphingomonas yanoikuyae as the nearest RDP homolog) was the most abundant after 4 weeks of incubation of both NW and NE soil samples (Fig. 5D and E). Continued liquid culture incubations, obtained by inoculating the supernatant of the NW soil-minimal salts medium culture into minimal salts medium and incubating it in a DCPD atmosphere, gave limited growth. The absorbance at 600 nm of the culture typically increased from 0.02 to 0.08 over a 2-week period and declined subsequently. The cultures showed a different RSGP profile in which standard 15 (Pseudomonas strain Q5) was dominant (hybridization pattern similar to that shown for Pseudomonas strain Q5 in Fig. 2A). Plating of these cultures on TY medium gave colonies with uniform morphology. RSGP testing of two of these indicated both to be standard 15.

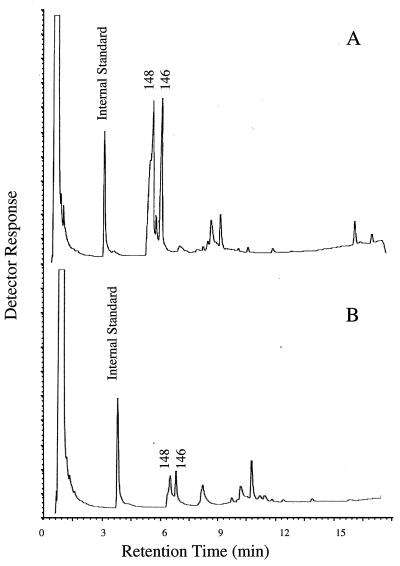

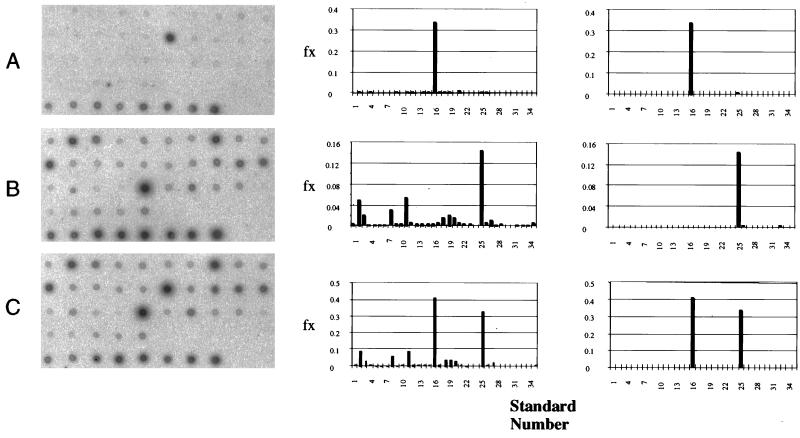

Inocula of LQ30, Q5, or LQ30 plus Q5 were added to sterilized soil (10 g) and minimal salts medium (10 ml) and incubated in a DCPD atmosphere for 7 weeks. A sample of nonsterilized soil was similarly incubated. GC patterns of ethyl acetate-extracted organics were similar for all five incubations. Those for the nonsterilized and sterilized soil incubations are shown in Fig. 6A and B, respectively. More oxidized DCPD derivatives were formed in the nonsterile soil incubation (Table 2). Comparison with known MS spectra for oxygenated DCPD derivatives (17, 23, 24) allowed the tentative identification of three mono-oxygenated derivatives (Fig. 1C through E) and one dioxygenated derivative (Fig. 1I). The addition of LQ30, Q5, or LQ30-plus-Q5 inocula also appeared to result in larger yields of oxygenated DCPD derivatives (Table 2). Extraction of DNA from these incubations and RSGP assays of the extracted DNAs confirmed that the inoculated bacteria were present (Fig. 7). However, mineralization experiments in which sterilized soil, minimal salts medium, uniformly labeled [14C]DCPD, and inocula of LQ30, Q5, or LQ30 plus Q5 were combined gave negligible amounts of [14C]CO2 in the alkali traps after 4 weeks of incubation (0.1 to 0.5% of added label).

FIG. 6.

GC patterns of organic compounds extracted from soil incubated with minimal salts medium in a DCPD atmosphere. Incubation was carried out with nonsterilized soil (A) and sterilized soil (B). The masses of peaks corresponding to oxidized DCPD derivatives are indicated.

TABLE 2.

Extraction of oxidized DCPD derivatives from soil minimal salts medium incubations

| NW soila | Inoculumb | Amt (μg) of oxidized derivativesc |

|---|---|---|

| Sterile | None | 37 |

| Sterile | Q5 | 103 |

| Sterile | LQ30 | 58 |

| Sterile | Q5 + LQ30 | 88 |

| Nonsterile | None | 162 |

Sterilized or nonsterilized NW soil (10 g) was combined with 10 ml of minimal salts medium and incubated in a DCPD atmosphere for 7 weeks.

Saturated cultures of Q5 (10 μl), LQ30 (20 μl), or both (10 and 20 μl) were added.

Peak areas of oxidized DCPD derivatives (masses indicated in Fig. 6) were combined and converted into micrograms by comparison with the internal standard, p-dichlorobenzene. The results of duplicate experiments agreed within 10%.

FIG. 7.

RSGP of DNAs extracted from sterilized soil inoculated with LQ30 (A), Q5 (B), and LQ30 plus Q5 (C). The hybridization patterns are shown on the left, the derived community profiles (fx plotted against standard number) are shown in the middle, and the corrected community profiles are shown on the right. Cross-hybridization correction was done with relevant data from the cross-hybridization matrix (Fig. 3), as described by Telang et al. (19).

DISCUSSION

Bioremediation often involves the degradation of complex mixtures of contaminants by undefined mixed populations of microorganisms (16). The degradation of C5+ by a soil microbial community certainly falls into this category. The changes in community composition upon introduction of a single or mixed hydrocarbon substrate have been characterized by plating and by the use of probes for hydrocarbon degradation genes. Sayler et al. (14) used the TOL and NAH plasmids to track the fraction of the population capable of growing with either toluene or naphthalene as the sole carbon and energy source. It was found that only a fraction of the colonies appearing on selective media reacted with these probes. In the case of toluene degradation, the unreactive bacteria may have degraded toluene through a pathway other than TOL, e.g., by the dioxygenase-initiated pathway catalyzed by Pseudomonas putida F1. In the case of naphthalene degradation, genes with no homology to NAH have recently been described (7). Thus, even the analysis of a single degradative function may require the application of multiple probes. Greer et al. (8) have therefore proposed a biotreatability protocol, which involves the use of multiple probes to assess the presence of hydrocarbon-degrading bacteria as well as physical and chemical analysis of the contaminated soil and assessment of pollutant mineralization and respiratory capacity of the resident community.

We have shown here that the effects of the introduction of hydrocarbon or xenobiotic compounds on a soil microbial community can also be monitored by RSGP, a technique used previously to characterize the dynamics of microbial communities in oil fields (19, 25–27). Whole genome probes can easily distinguish species from different genera (Fig. 3) and can, to a degree, distinguish species within the same genus (Fig. 2 and 3). The RSGP format allows rapid tracking of the abundance of multiple microbial genomes. The present collection of 35 genomes is modest relative to the microbial diversity that is thought be present in soil environments. Torsvik et al. (21) have estimated from analysis of Cot curves that soil communities contain 103 to 104 genome equivalents. If this number also applies to the community present in pyrolysis plant soils, the master filters created in this study cover only a small fraction of the resident community and are clearly not representative. The experimental data obtained in this study on the effect of toluene suggest that the actual situation in our target environment may be more favorable. Most of the species represented on the filter were cultured on rich media (Table 1). Only three were isolated in minimal media with a hydrocarbon as the sole source of carbon and energy, and toluene was not used in these isolations. However, when the soil community was exposed to toluene in the presence of minimal salts medium, one of the standard genomes on the filter was estimated to represent 40% of the extracted community DNA (Fig. 5B). Standard 11 (Pseudomonas strain LQ20), harboring this genome, was originally isolated on rich medium but was subsequently shown to be indeed capable of mineralizing toluene to a similar extent to the entire soil community (Fig. 5C).

The toxicity of individual unsaturated hydrocarbons to microbial cells (15) and the large number of components that can be present may preclude the isolation of all specific degraders. However, assuming that many of these can also be cultured on regular plating media, a general strategy to identify these species could be to (i) isolate an extensive set on rich plating media, (ii) generate a master filter of genomes with limited cross-hybridization, and (iii) identify possible degraders of specific components by determining the response of the community to introduction of the chemical. This approach appears to work in the case of toluene degradation by the community present in C5+-contaminated soil (Fig. 5B), but identification of degraders of the extremely recalcitrant petrochemical DCPD is more difficult.

Evidence for a role of microorganisms in the conversion of DCPD to oxidized derivatives was obtained by Stehmeier et al. (17), who showed that this conversion is absent in sterilized media. van Breemen and Tsou (24) suggested that oxidized DCPD derivatives are formed by nonmicrobial, especially photochemical, mechanisms, although the existence of specialized microorganisms with DCPD-oxidizing ability in soil was not ruled out by these experiments.

Our data support a role for microorganisms in the generation of oxidized DCPD derivatives (Fig. 6; Table 2). However, even in the absence of light and microbes, some oxidized derivatives appeared (Table 2), perhaps because of the different mode of delivery of the chemical (through an aerobic, saturated vapor phase) compared to earlier studies (adsorbed to charcoal [17, 24]). Sphingomonas strain LQ30 was implicated in DCPD oxidation by RSGP assays (Fig. 5D and E). The calculated fractions of the total population of this organism (0.04 to 0.08) are much lower than in the case of enrichment of Pseudomonas strain LQ20 by toluene (0.40), indicating that none of the microorganisms currently represented on the filter can derive significant energy from DCPD oxidation. These results confirm the recalcitrant nature of this chemical and suggest that in the soil environment DCPD oxidation may result solely from cometabolic reactions. Cometabolic degradation of DCPD will be explored in future studies by determining the change in the community composition by RSGP upon exposure to mixtures of DCPD and degradable BTEX compounds. The possibility that Pseudomonas strain Q5, which can use naphthalene as the sole source of carbon and energy (Table 1) and which was identified by RSGP as the dominant component of continued liquid culture incubations in the presence of DCPD, degrades DCPD cometabolically when growing on naphthalene will also be investigated.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by a Strategic Grant from the Natural Science and Engineering Research Council of Canada to G.V. Partial salary support for L.G.S. was provided by Novacor Research and Technology Corp., Calgary, Canada.

We thank F. Sun for help in the acquisition of GC-MS spectra.

REFERENCES

- 1.Amann R I, Stromley J, Devereux R, Key R, Stahl D A. Molecular and microscopic identification of sulfate-reducing bacteria in multispecies biofilms. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1992;58:614–623. doi: 10.1128/aem.58.2.614-623.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Amoore J E, Hautala E. Odor as an aid to chemical safety: odor thresholds compared with threshold limit values and volatilities for 214 industrial chemicals in air and water dilution. J Appl Toxicol. 1983;3:272–290. doi: 10.1002/jat.2550030603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bakken L R. Separation and purification of bacteria from soil. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1985;49:1482–1487. doi: 10.1128/aem.49.6.1482-1487.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bazylinski D A, Wirsen C O, Jannasch H W. Microbial utilization of naturally occurring hydrocarbons at the Guaymas Basin hydrothermal vent site. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1989;55:2832–2836. doi: 10.1128/aem.55.11.2832-2836.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Burlage R S, Hooper S W, Sayler G S. The TOL (pWW0) catabolic plasmid. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1989;55:1323–1328. doi: 10.1128/aem.55.6.1323-1328.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gerhardt P, Murray R G E, Costilow R N, Nester E W, Wood W A, Kreig N R, Phillips G B. Manual of methods for general bacteriology. Washington, D.C: American Society for Microbiology; 1981. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Goyal A K, Zylstra G J. Molecular cloning of novel genes for polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon degradation from Comamonas testosteroni GZ39. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1996;62:230–236. doi: 10.1128/aem.62.1.230-236.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Greer C, Hawari J, Samson R. Development and application of techniques for monitoring the bioremediation of petroleum hydrocarbon-contaminated soils. In: Gould W D, Lortie L, Rodrigue D, editors. Proceedings of the Tenth Annual General Meeting of Biominet. Ottawa, Canada: Canadian Government Publishing Centre, Supply and Services Canada; 1993. pp. 165–183. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hicks R, Amann R I, Stahl D A. Dual staining of natural bacterioplankton with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole and fluorescent oligonucleotide probes targeting kingdom-level 16S rRNA sequences. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1992;58:2158–2163. doi: 10.1128/aem.58.7.2158-2163.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Maidak B L, Larsen N, McCaughey M J, Overbeek R, Olsen G J, Fogel K, Blandy J, Woese C R. The Ribosomal Database Project. Nucleic Acids Res. 1994;22:3485–3487. doi: 10.1093/nar/22.17.3485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Marmur J. A procedure for the isolation of deoxyribonucleic acid from micro-organisms. J Mol Biol. 1961;3:208–218. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Olsen G J, Lane D J, Giovannoni S J, Pace N R, Stahl D A. Microbial ecology and evolution: a ribosomal RNA approach. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1986;40:337–365. doi: 10.1146/annurev.mi.40.100186.002005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Postgate J R. The sulfate-reducing bacteria. 2nd ed. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sayler G S, Shields M S, Tedford E T, Breen A, Hooper S W, Sirorkin K M, Davis J W. Application of DNA-DNA colony hybridization to the detection of catabolic genotypes in environmental samples. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1985;49:1295–1303. doi: 10.1128/aem.49.5.1295-1303.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sikkema J, de Bont J A M, Poolmans B. Mechanisms of membrane toxicity of hydrocarbons. Microbiol Rev. 1995;59:201–222. doi: 10.1128/mr.59.2.201-222.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Spain J C, Pettigrew C A, Haigler B E. Biodegradation of mixed solvents by a strain of Pseudomonas. Environ Sci Res. 1991;41:175–184. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stehmeier L G, Jack T R, Voordouw G. In vitro degradation of dicyclopentadiene by microbial consortia isolated from hydrocarbon-contaminated soil. Can J Microbiol. 1996;42:1051–1060. doi: 10.1139/m96-135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stehmeier L. Fate of dicyclopentadiene in the environment. Ph.D. thesis. Calgary, Canada: The University of Calgary; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Telang A J, Ebert S, Foght J M, Westlake D W S, Jenneman G E, Gevertz D, Voordouw G. The effect of nitrate injection on the microbial community in an oil field as monitored by reverse sample genome probing. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1997;63:1785–1793. doi: 10.1128/aem.63.5.1785-1793.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Telang A J, Voordouw G, Ebert S, Sifeldeen N, Foght J M, Fedorak P M, Westlake D W S. Characterization of the diversity of sulfate-reducing bacteria in soil and mining waste water environments by nucleic acid hybridization techniques. Can J Microbiol. 1995;40:955–964. doi: 10.1139/m94-152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Torsvik V, Sørheim R, Goksøyr J. Total bacterial diversity in soil and sediment communities—a review. J Ind Microbiol. 1996;17:170–178. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tsai Y-L, Olson B H. Rapid method for direct extraction of DNA from soil and sediments. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1991;57:1070–1074. doi: 10.1128/aem.57.4.1070-1074.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.van Breemen R B, Fenselau C C, Cotter R J, Curtis A J, Connolly G. Derivatives of dicyclopentadiene in ground water. Biomed Environ Mass Spectrom. 1987;14:97–102. doi: 10.1002/bms.1200140302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.van Breemen R B, Tsou Y. Oxidation of dicyclopentadiene in surface water. Biol Mass Spectrom. 1993;22:579–584. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Voordouw G, Voordouw J K, Karkhoff-Schweizer R R, Fedorak P M, Westlake D W S. Reverse sample genome probing, a new technique for identification of bacteria in environmental samples by DNA hybridization and its application to the identification of sulfate-reducing bacteria in oil field samples. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1991;57:3070–3078. doi: 10.1128/aem.57.11.3070-3078.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Voordouw G, Voordouw J K, Jack T R, Foght J, Fedorak P M, Westlake D W S. Identification of distinct communities of sulfate-reducing bacteria in oil fields by reverse sample genome probing. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1992;58:3542–3552. doi: 10.1128/aem.58.11.3542-3552.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Voordouw G, Shen Y, Harrington C S, Telang A J, Jack T R, Westlake D W S. Quantitative reverse sample genome probing of microbial communities and its application to oil field production waters. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1993;59:4101–4114. doi: 10.1128/aem.59.12.4101-4114.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Voordouw G, Armstrong S M, Reimer M F, Fouts B, Telang A J, Shen Y, Gevertz D. Characterization of 16S rRNA genes from oil field microbial communities indicates the presence of a variety of sulfate-reducing, fermentative, and sulfide-oxidizing bacteria. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1996;62:1623–1629. doi: 10.1128/aem.62.5.1623-1629.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Voordouw G, Strang J D, Wilson F R. Organization of the genes encoding [Fe] hydrogenase in Desulfovibrio vulgaris subsp. oxamicus Monticello. J Bacteriol. 1989;171:3881–3889. doi: 10.1128/jb.171.7.3881-3889.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yen K-M, Serdar C M. Genetics of naphthalene catabolism in pseudomonads. Crit Rev Microbiol. 1988;15:247–268. doi: 10.3109/10408418809104459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]