Abstract

Introduction

Given the growing interest and use of interleukin-17 inhibitors (anti-IL17) for the treatment of psoriatic arthritis (PsA), an observational study has been conducted to characterize the patient profile, treatment patterns, and persistence of ixekizumab or secukinumab in patients with PsA receiving them as first anti-IL17.

Methods

This is a multicenter retrospective study, conducted at eight Spanish hospitals where data from adult patients with PsA were collected from electronic medical records. Three cohorts of patients, initiating treatment with an anti-IL17 [secukinumab 150 mg (SECU150), secukinumab 300 mg (SECU300), or ixekizumab (IXE)] between January 2019 and March 2021, were included. Demographic and clinical patient characteristics, treatment patterns, and persistence were analyzed descriptively. Continuous data were presented as mean [standard deviation (SD)] and categorical variables as frequencies with percentages. Persistence rates at 3, 6, and 12 months were calculated.

Results

A total of 221 patients with PsA were included in the study [SECU150, 103 (46.6%); SECU300, 38 (17.2%); and IXE, 80 (36.2%)]. Treatment patterns differed by clinical characteristics: SECU150 was initiated more frequently in patients with moderate PsA and less peripheral joint involvement, while patients on SECU300 included those with a higher rate of enthesitis and active skin psoriasis, and patients on IXE showed a longer time since PsA diagnosis, more frequent comorbidities, joint involvement, and diagnosed skin psoriasis. Conventional synthetic disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs (csDMARDs) were previously administered in 88.2% of patients and biologic or targeted synthetic disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs (b/tsDMARDs) were administered in 72.9%. The mean number of previous b/tsDMARDs was 2.4 (SD 1.5) in the IXE cohort, 1.7 (SD 0.9) in the SECU300 cohort, and 1.6 (SD 1.0) for those in the SECU150 cohort. The global persistence on all anti-IL17 was 97.2%, 88.4%, and 81.0% at 3, 6, and 12 months, respectively. The most frequent reason for discontinuation across the three cohorts was lack of effectiveness (16.7%; 37/221).

Conclusions

Most of the patients with PsA treated with anti-IL17 in Spain had moderate to severe disease activity, high peripheral joint and skin involvement, and had received previous b/tsDMARDs. More than 80% of patients with a 1-year follow-up persisted on anti-IL17, with the highest rate observed in the IXE cohort, followed by the SECU150 then SECU300 cohorts.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s12325-023-02693-w.

Keywords: Psoriatic arthritis (PsA), Interleukin-17 inhibitors (anti-IL17), Secukinumab (SECU), Ixekizumab (IXE), Treatment patterns, Persistence, Real-world evidence (RWE)

Key Summary Points

| Why carry out this study? |

| Interleukin-17 inhibitors (anti-IL17) have been introduced in standard clinical practice in Spain as an additional treatment option for psoriatic arthritis (PsA). There is a knowledge gap in the use of anti-IL17 for PsA in a real-life setting. |

| What was learned from this study? |

| Overall, patients were prescribed the first anti-IL17 at 51.5 (11.6) years of age with a PsA disease duration of 8.1 (7.7) years, with patients on ixekizumab (IXE) being the oldest and having the longest PsA duration, followed by patients on secukinumab 150 mg (SECU150) then secukinumab 300mg (SECU300). Most of them presented comorbidities, with a slightly higher rate in patients taking IXE. |

| Of all the patients, 88.2% were treated with a conventional synthetic disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drug (csDMARD) (methotrexate being the most common csDMARD). Additionally, 72.9% of the patients had received biologic or targeted synthetic disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs (b/tsDMARDs) prior to anti-IL17 therapy, with a higher number of previous b/tsDMARDs in patients on IXE, followed by patients on SECU300 and then SECU150. |

| The 1-year overall persistence rate of anti-IL-17 was above 80%, with the highest drug survival in patients on IXE, followed by SECU150 and then SECU300. |

Introduction

Psoriatic arthritis (PsA) is a chronic, systemic, immune-mediated, inflammatory arthritis commonly associated with plaque psoriasis, joint involvement, enthesitis, dactylitis, and axial involvement. PsA can be progressive and destructive, resulting in physical abnormalities, impaired function, diminished quality of life, and increased mortality [1]. Studies have shown that approximately 0.16–0.25% of people worldwide and about 0.58% of people in Spain suffer from PsA [2–4].

The European League Against Rheumatism (EULAR) recommendations suggest a pharmacological approach based on phenotype, focused on each musculoskeletal manifestation, taking also into account non-musculoskeletal involvement and considering comorbidities. They highlight the multidisciplinary management and shared decision-making. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and topical therapies are an option for initial therapy, but in polyarthritis or oligo/monoarthritis with poor prognostic factors, conventional synthetic disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs (csDMARDs) are recommended. If the treatment target is not achieved, biologic or targeted synthetic DMARDs (b/tsDMARDs), tumor necrosis factor inhibitor (anti-TNF) drugs, interleukin-17 inhibitors (anti-IL17), interleukin-23 inhibitors (anti-IL23), or interleukin-12/23 inhibitors (anti-IL12/23) should be considered, taking into account the severity of skin involvement. Janus kinase inhibitors (JAKi) are proposed in patients with an inadequate response to at least one bDMARD or when a bDMARD is not appropriate. Phosphodiesterase 4 inhibitors may be considered in patients with mild disease and an inadequate response to at least one csDMARD, in whom neither a bDMARD nor a JAKi is appropriate [5]. The Group for Research and Assessment of Psoriasis and Psoriatic Arthritis (GRAPPA) recommendations review the literature-covered treatments for the key domains of PsA: peripheral arthritis, axial disease, enthesitis, dactylitis, and skin and nail psoriasis; along with PsA-related conditions (uveitis and inflammatory bowel disease) and comorbidities. Choice of therapy for an individual should ideally address all disease domains active in that patient along with relevant comorbidities [6].

The short-term efficacy of anti-IL17 is similar to that of anti-TNF, placing anti-TNF and anti-IL17 as equally valid options for bDMARDs in patients with refractory PsA, except in patients with clinically relevant skin involvement, where preference should be given to an anti- IL-17A or IL-17A/F, or anti-IL-23 or IL-12/23 [7–9].

In Spain, only two anti-IL17 are reimbursed and commercially available for the treatment of active PsA: secukinumab (Cosentyx®) and ixekizumab (Taltz®). Secukinumab (SECU) was reimbursed since April 2016 according to its Summary of Product Characteristics (SmPC) (treatment of active PsA, used alone or in combination with methotrexate when response to previous csDMARD therapy proves inadequate)[10]. Ixekizumab (IXE) is indicated for patients who have responded inadequately or are intolerant to one or more csDMARDs, and it can be used alone or in combination with methotrexate [11] with reimbursement only available for those patients after anti-TNF failure [12].

According to the SmPc the recommended dosing of IXE is 160 mg, followed by 80 mg every 4 weeks thereafter by subcutaneous injection. For patients with PsA with concomitant moderate to severe plaque psoriasis, the recommended dosing regimen is 160 mg, followed by 80 mg at weeks 2, 4, 6, 8, 10, and 12, then 80 mg every 4 weeks. The recommended dosing of secukinumab is 150 mg (SECU150) every 4 weeks for patients with biologic-naïve PsA by subcutaneous injection and 300 mg (SECU300) for patients with concomitant, moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis or who are anti-TNF inadequate responders [11, 13]. In October 2018, the European Medicines Agency approved a label update for SECU to include dosing flexibility of up to 300 mg based on clinical response [14].

SECU has shown efficacy and safety in biologic-naïve patients with PsA and in those previously exposed to anti-TNF (FUTURE-1 and FUTURE-2) [15, 16], but it has not demonstrated superiority to adalimumab (EXCEED)[17]. In the phase 3 FUTURE-2 study, an optional dose escalation was possible during the study starting at week 128 if active signs of disease were observed, based on the physician’s judgment. At 5 years, more patients showed improvements in their American College Rheumatology (ACR) and Psoriasis Area and Severity Index score (PASI) responses after dose escalation, highlighting the potential need of dose escalation from 150 to 300 mg in patients with a suboptimal response to SECU150 [18].

IXE has shown efficacy and safety in biologic-naïve patients with PsA (SPIRIT-P1 clinical trial) [19] and in those previously exposed to anti-TNF (SPIRIT-P2 clinical trial) [20]. Moreover, in SPIRIT-H2H, an open-label, randomized, head-to-head clinical phase 3 study, IXE demonstrated superiority to adalimumab in simultaneously achieving to a reduction of at least 50% in disease activity (ACR50) and complete skin clearance (PASI 100) [21].

Real-world evidence (RWE) studies are playing an increasingly significant role in healthcare decision-making, as they provide relevant complementary information to clinical trials in larger and more diverse populations and under clinical practice conditions. However, there are scarce RWE publications related to anti-IL17 for the management of PsA, especially those aimed at evaluating their persistence in patients treated with both IXE or SECU [22]. Hence, the PerfIL-17 study aimed to understand the treatment patterns, drug persistence, and reasons for treatment discontinuation in adult patients with PsA who have received IXE and SECU, in its two doses, in routine clinical practice in Spain [23, 24].

Methods

Study Design and Patient Population

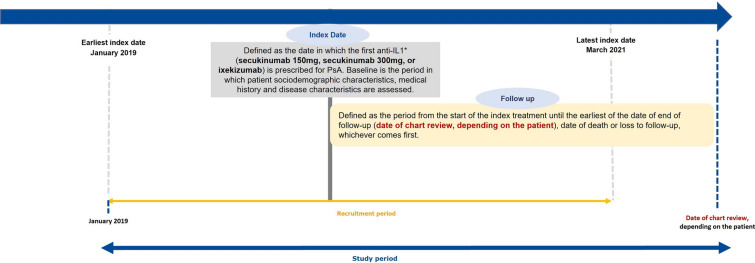

The PerfIL-17 study is a descriptive retrospective chart review study at eight hospital rheumatology departments in Spain. Eligible patients were adults with confirmed diagnosis of PsA [6], who had initiated treatment with an anti-IL17 for the first time between January 2019 and the end of March 2021, and who had at least one follow-up assessment available. Patients must have received the following treatments and starting doses, creating three cohorts of patients for the analysis: SECU150, SECU300, or IXE (allowing for subsequent change to 80 mg). Patients who were in a clinical trial during the treatment with anti-IL17 or who did not give consent to participate in the study were excluded. The index date was defined as the first anti-IL17 prescription date (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Overall study design. Anti-IL17, interleukin-17 inhibitors

The sample was planned to include an approximate maximum of 225 adult eligible patients, based on pragmatic criteria to balance the number of patients between exposure groups while ensuring a number of patients in each group that was feasible to achieve. Exposure treatments of interest were launched at different dates and consequently they had different penetration and follow-up periods. Thus, the number of patients expected in the IXE cohort group was low. As a target, 75 patients on IXE had been stated as feasible. Thus, the other two SECU cohorts were sized accordingly.

In particular, using a confidence interval of 95%, a sample of 75 patients in each cohort allowed precision around observed percentages in a binary variable ranging from 10% to 50% and from ± 7.4% to ± 11.8%, respectively. As an example, a discontinuation rate of 30% of patients at 12 months would result in a level of precision ranging from a lower limit of 19.1% to an upper limit of 40.9%.

As a result of its retrospective in nature, at no time did the study interfere with the patients’ usual clinical practice.

Study Variables

Patients’ Demographic and Clinical Profile

Baseline clinical and demographic characteristic profiles of patients with PsA who had received SECU150, SECU300, or IXE as first anti-IL17 were described.

Treatment Patterns

Treatment patterns were analyzed, describing concomitant csDMARD prescribed with anti-IL17, to determine if they were given in monotherapy or combination and if they were maintained over time. Previous and subsequent treatments were also analyzed, including b/tsDMARDs in monotherapy or combination, used by patients in the anti-IL17 treatments, providing the frequency and percentage of patients in each cohort.

Treatment Persistence

Treatment persistence was calculated as the difference between the discontinuation date and the initiation date, through either loss to follow-up or the end of the study, expressed in months. Rates of persistence at specific time periods were also calculated and given as a description of the frequency and percentage of patients continuing treatment with anti-IL17 at 3, 6, and 12 months.

We described the reasons for discontinuation of anti-IL17 in the three cohorts by presenting the distribution of patients across the different reasons as frequencies and percentages.

Loss of effectiveness as a reason for discontinuation only refers to articular involvement and not to any change in the skin involvement.

Statistical Analysis

Statistics for continuous variables were presented as the mean, standard deviation (SD), median, 25% quartile (Q1), 75% quartile (Q3), minimum, and maximum. Categorical variables were summarized by categories with frequency counts and percentages. For the purpose of descriptive analyses, instances of missing data were excluded when calculating percentages. However, for categorical data, the frequencies of missing values were delineated as a distinct category. In the case of continuous variables, the extent of missing data was summarized. Time-to-event variables, with time from the index date as the underlying timescale, were described with Kaplan–Meier curves. Patients who continued on treatment at the end of follow-up were censored up to the completion of the study follow-up or losses to follow-up.

Ethical Considerations

The study was conducted in accordance with the ethical principles of the Declaration of Helsinki, the Good Pharmacoepidemiology Practices (GPPs) guidelines of the International Society for Pharmacoepidemiology, and local rules and regulations.

The study was sent to the Spanish Health Authorities for classification and was subsequently evaluated and approved by a central ethics committee (Comité de Etica de la Investigación con medicamentos regional de la Comunidad de Madrid, minutes No. 07/20), and local ethics committees as required.

Results

Patients’ Demographic and Clinical Profile

A total of 221 patients with PsA were analyzed: 103 patients (46.6%) received SECU150, 38 patients (17.2%) SECU300, and 80 patients (36.2%) IXE as the first anti-IL17. The mean follow-up period was 21.4 (SD 8.0) months among the three cohorts, while patients on SECU150 had the highest follow-up duration (23.2 months; SD 7.9), followed by patients on SECU300 (21.7 months; SD 8.9), then patients on IXE (18.9 months; SD 7.1).

Table 1 presents patient demographics at baseline. The overall mean age when starting with an anti-IL17 was 51.5 (SD 11.6) years, and 51.6% (114/221) of patients were male. Overall, the mean BMI was 28.6 (SD 6.3) kg/m2, and most patients with a calculated BMI were overweight or obese (70.0%). Overall, 82.8% presented comorbidities and/or other conditions, with the most common being cardiovascular diseases (37.2%) and obesity (30.6%) (Table 1, supplementary material).

Table 1.

Baseline patient demographics, psoriasis and PsA characteristics

| Overall | SECU150 | SECU300 | IXE | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patients n (%) | 221 (100.0) | 103 (100.0) | 38 (100.0) | 80 (100.0) |

| Age at anti-IL17 prescription (years) | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 51.5 (11.6) | 51.8 (12.4) | 46.1 (10.3) | 53.7 (10.4) |

| Sex, n (%) | ||||

| Male | 114 (51.6) | 54 (52.4) | 18 (47.4) | 42 (52.5) |

| BMI (kg/m2) | ||||

| n (missing) | 90 (131) | 32 (71) | 21 (17) | 37 (43) |

| Mean (SD) | 28.6 (6.3) | 29.0 (6.8) | 29.0 (6.7) | 28.1 (5.9) |

| BMI (kg/m2), classification n (%) | ||||

| Underweight (< 18.5) | 4 (4.4) | 2 (6.3) | 1 (4.8) | 1 (2.7) |

| Normal weight (18.5–24.9) | 23 (25.6) | 8 (25.0) | 4 (19.0) | 11 (29.7) |

| Overweight–obese (> 24.9) | 63 (70.0) | 22 (68.8) | 16 (76.2) | 25 (67.6) |

| Comorbidities/conditions, n (%) | ||||

| Yes | 183 (82.8) | 82 (79.6) | 30 (78.9) | 71 (88.8) |

| Unknown | 1 (0.5) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (2.6) | 0 (0.0) |

| Baseline skin psoriasis characteristics | ||||

| Diagnosed psoriasis, n (%) | ||||

| Yes | 191 (86.4) | 82 (79.6) | 33 (86.8) | 76 (95.0) |

| Unknown | 9 (4.1) | 6 (5.8) | 2 (5.3) | 1 (1.3) |

| Duration of psoriasis since diagnosis (years) | ||||

| n known | 114 | 49 | 17 | 48 |

| Mean (SD) | 15.2 (13.9) | 13.0 (13.3) | 16.7 (13.6) | 16.9 (14.6) |

| Active psoriasis, n (%) | ||||

| Yes | 133 (69.6) | 56 (68.3) | 28 (84.8) | 49 (64.5) |

| Unknown | 26 (13.6) | 9 (11.0) | 2 (6.1) | 15 (19.7) |

| PASI | ||||

| n (missing) | 25 (58) | 4 (26) | 9 (5) | 12 (27) |

| Mean (SD) | 7.9 (6.0) | 3.9 (3.2) | 8.3 (6.5) | 9.0 (6.2) |

| BSA, n (%) | ||||

| n (missing) | 25 (58) | 5 (26) | 10 (5) | 10 (27) |

| Mean (SD) | 9.7 (12.3) | 4.5 (5.9) | 10.6 (13.3) | 11.4 (13.8) |

| PsA clinical characteristics | ||||

| Age at diagnosis of PsA (years) | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 43.4 (12.4) | 44.9 (13.7) | 39.7 (11.7) | 43.3 (10.8) |

| Years of diagnosed PsA at anti-IL17 prescription | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 8.1 (7.7) | 6.9 (7.3) | 6.5 (6.8) | 10.5 (8.2) |

| PsA disease activitya | ||||

| Low | 46 (20.8) | 18 (17.5) | 13 (34.2) | 15 (18.8) |

| Moderate | 119 (53.8) | 59 (57.3) | 17 (44.7) | 43 (53.8) |

| High | 36 (16.3) | 12 (11.7) | 7 (18.4) | 17 (21.3) |

| Unknown | 20 (9.0) | 14 (13.6) | 1 (2.6) | 5 (6.3) |

| Joint involvement | ||||

| Yes | 206 (93.2) | 92 (89.3) | 35 (92.1) | 79 (98.8) |

| Location (multi-response) | ||||

| Peripheral arthritis | 180 (87.4) | 72 (78.3) | 33 (94.3) | 75 (94.9) |

| Axial | 92 (44.7) | 43 (46.7) | 14 (40.0) | 35 (44.3) |

| Dactylitis | ||||

| Yes | 41 (18.6) | 20 (19.4) | 7 (18.4) | 14 (17.5) |

| Unknown | 11 (5.0) | 8 (7.8) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (3.8) |

| Enthesitis | ||||

| Yes | 56 (25.3) | 20 (19.4) | 15 (39.5) | 21 (26.3) |

| Unknown | 14 (6.3) | 9 (8.7) | 1 (2.6) | 4 (5.0) |

| Negative rheumatoid factor | ||||

| Yes | 134 (60.6) | 54 (52.4) | 25 (65.8) | 55 (68.8) |

| Unknown | 60 (27.1) | 30 (29.1) | 11 (28.9) | 19 (23.8) |

PsA psoriatic arthritis, anti-IL17 interleukin-17 inhibitors, BMI body mass index, BSA body surface area, PASI psoriasis area and severity index, DAPSA disease activity in psoriatic arthritis, SD standard deviation, SECU150 secukinumab 150 mg, SECU300 secukinumab 300 mg, IXE ixekizumab

aDisease remission (DAS28 < 2.6, DAPSA ≤ 4), low (DAS28 ≥ 2.6 and ≤ 3.2, DAPSA > 4 and ≤ 14), moderate (DAS28 > 3.2 and ≤ 5.1, DAPSA > 14 and ≤ 28), high (DAS28 > 5.1, DAPSA > 28)

As described in Table 1, at baseline most patients had a diagnosis of skin psoriasis (86.4%), with the IXE cohort presenting the highest diagnosed skin psoriasis rate (95.0%). At the index date, the mean duration from skin psoriasis diagnosis was 15.2 (SD 13.9) years, with patients on SECU300 showing the highest rate of active psoriasis at drug initiation (84.8%), followed by patients on SECU150 (68.3%) and then patients on IXE (64.5%).

Patients taking SECU150 had lower PASI and body surface area (BSA) scores (PASI mean 3.9, SD 3.2; BSA mean 4.5, SD 5.9) than patients on the SECU300 (PASI mean 8.3, SD 6.5; BSA mean 10.6, SD 13.3) or IXE cohort (PASI mean 9.0, SD 6.2; BSA mean 11.4, SD 13.8).

Table 1 also describes PsA clinical characteristics at baseline. Overall, the mean age at diagnosis of PsA was 43.4 (SD 12.4) years. The mean duration of PsA disease at the index date was 8.1 (SD 7.7) years, with patients on IXE presenting the longest disease duration (10.5 years, SD 8.2) followed by SECU150 (6.9 years, SD 7.3) then SECU300 (6.5 years, SD 6.8). Most patients (70.1%) had moderate to severe PsA disease activity at baseline assessed by Disease Activity in Psoriatic Arthritis (DAPSA) score, with the IXE cohort having the highest rate. Joint involvement was known in 93.2% of the patients. Across the three cohorts, musculoskeletal domain involvement was mostly peripheric (87.4%) followed by axial involvement in 44.7% of patients. Only 18.6% (42/221) of the total number of patients presented dactylitis. Enthesitis was observed in 25.3% (56/221) of patients with a higher prevalence in the SECU300 group (39.5%) followed by IXE (26.3%) and SECU150 (19.4%). Most patients (60.6%) presented a negative rheumatic factor, although this data was not available for approximately 27% of the sample.

Treatment Patterns

Table 2 shows treatments previously used for the management of PsA before anti-IL17 prescription. Overall, 88.2% of patients had been treated with a csDMARD; 91.3% of patients with IXE, 87.4% with SECU150, and 84.2% with SECU300. Overall, 72.9% of patients had received a b/tsDMARD before the index treatments (IXE, 93.8%; SECU300, 68.4%; SECU150, 58.3%). Of these, the vast majority (95.7%) were first exposed to b/tsDMARDs. The overall mean number of previous treatments with b/tsDMARDs was 2.0 (SD 1.3); in SECU150, 1.6 (SD 1.0); SECU300, 1.7 (SD 0.9); and IXE, 2.4 (SD 1.5).

Table 2.

Previous PsA treatments

| Overall | SECU150 | SECU300 | IXE | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patients, n (%) | 221 (100.0) | 103 (100.0) | 38 (100.0) | 80 (100.0) |

| Previous use of csDMARDs as PsA treatment, n (%) | ||||

| Yes | 195 (88.2) | 90 (87.4) | 32 (84.2) | 73 (91.3) |

| Unknown | 4 (1.8) | 2 (1.9) | 2 (5.3) | 0 (0.0) |

| Previous use of b/tsDMARDs as PsA treatment, n (%) | ||||

| Yes | 161 (72.9) | 60 (58.3) | 26 (68.4) | 75 (93.8) |

| Unknowna | 12 (5.4) | 9 (8.7) | 2 (5.3) | 1 (1.3) |

| Number of previous b/tsDMARDs | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 2.0 (1.3) | 1.6 (1.0) | 1.7 (0.9) | 2.4 (1.5) |

| Treatment in patients with bDMARDs as first agent, n (%) | ||||

| Adalimumab | 60 (37.3) | 22 (36.7) | 10 (38.5) | 28 (37.3) |

| Monotherapy | 34 (21.1) | 11 (18.3) | 8 (30.8) | 15 (20.0) |

| Combination | 26 (16.1) | 11 (18.3) | 2 (7.7) | 13 (17.3) |

| Etanercept | 49 (30.4) | 17 (28.3) | 8 (30.8) | 24 (32.0) |

| Monotherapy | 17 (10.6) | 6 (10.0) | 2 (7.7) | 9 (12.0) |

| Combination | 31 (19.3) | 11 (18.3) | 6 (23.1) | 14 (18.7) |

| Unknown | 1 (0.6) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (1.3) |

| Infliximab | 18 (11.2) | 5 (8.3) | 2 (7.7) | 11 (14.7) |

| Monotherapy | 7 (4.3) | 3 (5.0) | 0 (0.0) | 4 (5.3) |

| Combination | 10 (6.2) | 2 (3.3) | 1 (3.8) | 7 (9.3) |

| Unknown | 1 (0.6) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (3.8) | 0 (0.0) |

| Golimumab | 12 (7.5) | 7 (11.7) | 2 (7.7) | 3 (4.0) |

| Monotherapy | 3 (1.9) | 2 (3.3) | 1 (3.8) | 0 (0.0) |

| Combination | 9 (5.6) | 5 (8.3) | 1 (3.8) | 3 (4.0) |

| Certolizumab | 9 (5.6) | 3 (5.0) | 2 (7.7) | 4 (5.3) |

| Monotherapy | 3 (1.9) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (7.7) | 1 (1.3) |

| Combination | 6 (3.7) | 3 (5.0) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (4.0) |

| Ustekinumab | 6 (3.7) | 3 (5.0) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (4.0) |

| Monotherapy | 4 (2.5) | 2 (3.3) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (2.7) |

| Combination | 1 (0.6) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (1.3) |

| Unknown | 1 (0.6) | 1 (1.7) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Treatment in patients with tsDMARDs as first agent, n (%) | ||||

| Apremilast | 6 (3.7) | 2 (3.3) | 2 (7.7) | 2 (2.7) |

| Monotherapy | 4 (2.5) | 2 (3.3) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (2.7) |

| Combination | 2 (1.2) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (7.7) | 0 (0.0) |

| Tofacitinib (monotherapy) | 1 (0.6) | 1 (1.7) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

PsA psoriatic arthritis, anti-IL17 interleukin-17 inhibitors, bDMARDs biologic disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs, csDMARDs conventional synthetic disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs, tsDMARDs targeted synthetic disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs, SECU150 secukinumab 150 mg, SECU300 secukinumab 300 mg, IXE ixekizumab

aOnly one patient marked unknown, but as a result of inconsistencies/missing dates for 11 patients, it has not been possible to assess the previous treatment use

Among patients previously exposed to b/tsDMARDs, the most commonly prescribed drug was adalimumab, both overall and by cohort groups (overall, 37.3%), followed by etanercept (30.4%) and infliximab (11.2%). When given in combination, methotrexate was the preferred concomitant treatment (Table 2, supplementary material).

Table 3 describes prescription patterns of the anti-IL17. While prescribed as monotherapy in 54.8% of patients, in the case of combination therapy, methotrexate was the most frequently used csDMARD (30.8%). The mean time patients stayed on combination with csDMARDs was 15.9 (SD 9.6) months. Overall, 61.1% of patients received other concomitant treatments for PsA, with NSAIDs (66.7%) and systemic corticosteroids (43.7%) being the most common.

Table 3.

Description of the anti-IL17 treatment (index treatment)

| Overall | SECU150 | SECU300 | IXE | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient, n (%) | 221 (100.0) | 103 (100.0) | 38 (100.0) | 80 (100.0) |

| Type, n (%) | ||||

| Anti-IL17 in monotherapy | 121 (54.8) | 52 (50.5) | 22 (57.9) | 47 (58.8) |

| Anti-IL17 in combination with csDMARD | 100 (45.2) | 51 (49.5) | 16 (42.1) | 33 (41.3) |

| Type of csDMARD (combination), n (%) | ||||

| Methotrexate | 68 (30.8) | 34 (33.0) | 13 (34.2) | 21 (26.3) |

| Leflunomide | 19 (8.6) | 7 (6.8) | 2 (5.3) | 10 (12.5) |

| Sulfasalazine | 13 (5.9) | 10 (9.7) | 1 (2.6) | 2 (2.5) |

| Time on csDMARD treatment (months) | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 15.9 (9.6) | 17.9 (9.9) | 10.0 (9.5) | 15.6 (8.1) |

| Other concomitant treatment for PsA, n (%) | ||||

| Yes | 135 (61.1) | 70 (68.0) | 21 (55.3) | 44 (55.0) |

| Unknown | 2 (0.9) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (2.6) | 1 (1.3) |

| Type of concomitant treatment (multi-response), n (%) | ||||

| NSAIDs | 90 (66.7) | 51 (72.9) | 15 (71.4) | 24 (54.5) |

| Systemic corticosteroids | 59 (43.7) | 30 (42.9) | 10 (47.6) | 19 (43.2) |

PsA psoriatic arthritis, anti-IL17 interleukin-17 inhibitors, csDMARD conventional synthetic disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drug, NSAIDs non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, SECU150 secukinumab 150 mg, SECU300 secukinumab 300 mg, IXE ixekizumab

For those patients who permanently discontinued anti-IL17 treatment and received a subsequent drug during the study follow-up period, other b/tsDMARDs were the most prescribed (Table 4). Of patients in the SECU150 and SECU300 cohorts, 25% and 36%, respectively, switched to IXE, and 25% of patients in the IXE cohort were prescribed SECU150.

Table 4.

Treatments used after SECU150, SECU300, and IXE discontinuation

| Overall, N (%) | SECU150, n (%) | SECU300, n (%) | IXE, n (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient | 221 (100.0) | 103 (100.0) | 38 (100.0) | 80 (100.0) |

| Patient with permanent discontinuation from the anti-IL17 | 58 (26.2) | 29 (28.2) | 15 (39.5) | 14 (17.5) |

| Drugs used after the index treatment (ordered by frequency)a | ||||

| Other bDMARDs | 28 (59.6) | 16 (66.7) | 6 (54.5) | 6 (50.0) |

| IXE | 10 (21.3) | 6 (25.0) | 4 (36.4) | |

| tsDMARDs | 5 (10.6) | 2 (8.3) | 1 (9.1) | 2 (16.7) |

| SECU150 | 3 (6.4) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (25.0) | |

| SECU300 | 1 (2.1) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (8.3) | |

Anti-IL17 interleukin-17 inhibitors, bDMARDs biologic disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs, tsDMARDs targeted synthetic disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs, SECU150 secukinumab 150 mg, SECU300 secukinumab 300 mg, IXE ixekizumab

aNot all the patients started a new treatment after the permanent discontinuation from the anti-IL17

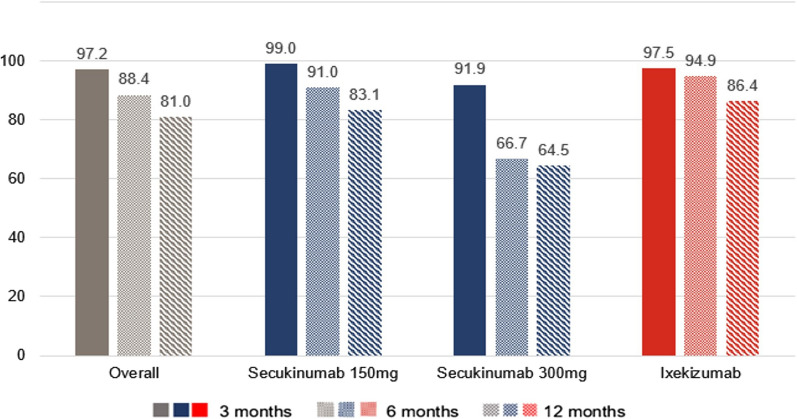

Treatment Persistence

Figure 2 shows the persistence rates on anti-IL17 treatment. Overall, persistence was 97.2% at 3 months, 88.4% at 6 months, and 81.0% at 12 months. At month 3, the persistence remained higher than 90% in the three cohorts (SECU150 99.0%, IXE 97.5%, SECU300 91.9%). At month 6 there was a drop in persistence, especially in the SECU300 cohort (IXE 94.9%, SECU150 91.0%, SECU300 66.7%). The IXE cohort presented the highest persistence rate at 12 months (86.4%), followed by SECU150 (83.1%). The lowest persistence at 12 months was observed in SECU300 patients (64.5%).

Fig. 2.

Persistence rates on anti-IL17 treatments, overall and by cohort

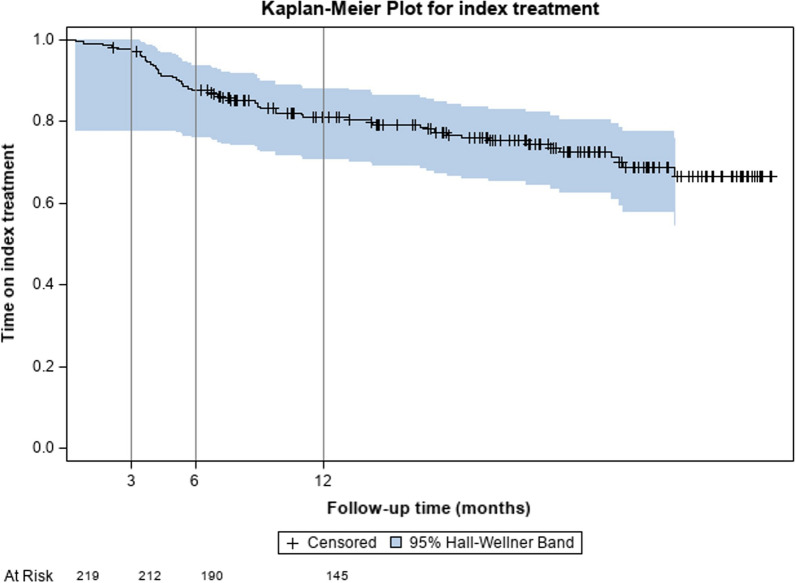

Figure 3 and supplementary Fig. 1 show the Kaplan–Meier curves of the overall sample and by treatment. As shown in Fig. 3, the mean time to discontinuation of anti-IL17 treatment was above the 12 months (23.1 months).

Fig. 3.

Time to discontinuation of index treatment: overall Kaplan–Meier curve

Reasons for Discontinuation

Overall, 26.2% of the patients permanently discontinued the index treatment. Reasons for discontinuation of the anti-IL17 treatments are shown in Table 5. SECU300 had the highest discontinuation rate (39.5%), the most common reasons being the lack of effectiveness (28.9%) and adverse reactions (10.5%). SECU150 showed a discontinuation rate of 28.2% and the most common reasons were lack of effectiveness (14.6%) and other reasons (8.7%). IXE had the lowest discontinuation rate (17.5%) with the most common reasons being the lack of effectiveness (13.8%) and other reasons (5.0%). None of the patients taking IXE discontinued the treatment as a result of adverse events.

Table 5.

Discontinuation and reasons for discontinuation of SECU150, SECU300, and IXE

| Overall | SECU150 | SECU300 | IXE | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient, n (%) | 221 (100.0) | 103 (100.0) | 38 (100.0) | 80 (100.0) |

| Reason for discontinuation (multi-response), n (%) | ||||

| Lack of effectiveness of anti-IL17 | 37 (16.7) | 15 (14.6) | 11 (28.9) | 11 (13.8) |

| Other reasons for discontinuation | 13 (5.9) | 9 (8.7) | 0 (0.0) | 4 (5.0) |

| Medical judgment/decision of the patient | 12 (5.4) | 8 (7.8) | 1 (2.6) | 3 (3.8) |

| Adverse reaction | 6 (2.7) | 2 (1.9) | 4 (10.5) | 0 (0.0) |

Anti-IL17 interleukin-17 inhibitors, SECU150 secukinumab 150 mg, SECU300 secukinumab 300 mg, IXE ixekizumab

Discussion

Data on RWE for anti-IL17A in the treatment of PsA are scarce and only consider anti-IL17 grouped by class or by analyzing one of the drugs in isolation. This is the first study describing IXE and SECU, with independent results for 150 mg and 300 mg dosage. The results reported here reflect the high persistence on anti-IL17A in a real-life setting. While two recently published retrospective Spanish studies [25, 26] already provide insights into the persistence on SECU or IXE, the PerfIL-17 study yields additional real-world data on the patient’s profile, as well as treatment patterns and reasons for discontinuation of both drugs.

The sociodemographic and clinical characteristics reported from this sample are in accordance with previous studies [22, 25, 27–32]. Differences in the baseline characteristics across the treatment groups are likely due to the observational study design (i.e., lack of randomization), different reimbursement requirements across multicenter studies or between countries, and the possibility that in real life, patients might be switched to a new biologic before losing response completely. Regarding this, patients from this study showed they had PsA for an average of 8 years, and mostly presented a moderate or high level of disease activity. Most patients were overweight and presented comorbidities such as cardiovascular diseases.

In addition, the PerfIL-17 study population had a diagnosis of psoriasis for over 10 years. The average severity of psoriasis in these patients was similar to that reported in randomized clinical trials [16, 17, 19, 20]. These data are in line with recommendations that encourage the use of anti-IL17 in patients with relevant skin involvement [33].

PerfIL-17 is the first study in Spain to look at both approved doses of SECU separately, although the SECU300 group was much smaller. Patients taking SECU300 were the youngest and presented a higher rate of enthesitis and active psoriasis than patients on the lower dose. On the other hand, patients receiving SECU150 presented the lowest PASI and BSA scores, lower proportion of high PsA disease activity, and less dactylitis. Interestingly, at least 58.3% of patients given SECU150 were not treated according to the indication, as they had previously failed on biologics. We cannot rule out that local practices suffering budget restrictions may fall under this finding.

Although more real-world data are available on the older anti-IL17, IXE was only approved for the treatment of PsA in 2018, and there is limited published data on IXE users. Patients taking IXE were the oldest and presented more frequent comorbidities, higher disease activity, and a longer time since diagnosis. In contrast with the findings reported by Perrone et al., i.e., that almost 90% of patients taking IXE had concomitant active psoriasis, our data showed that less than two-thirds of the patients taking IXE had registered data on active psoriasis manifestations. This result could be explained by a missing 20% of data on the activity on skin and nail psoriasis in our sample.

In terms of previous treatment use by our patients, the IXE cohort showed the highest percentage (93.8%) and number of previous biologics in the study. Notably, this finding is similar to those from other Spanish studies [25, 26], where 72.6–90% of patients on IXE had been previously treated with b/tsDMARDs, but do not concur with studies from other countries, where a lower proportion of patients exposed to prior b/tsDMARDs was observed (44.4%) [22]. The SECU150 and 300 cohorts in our study showed lower proportions of b/tsDMARD-experienced patients (58.3% and 68.4%, respectively), which is in line with the figures in previous studies (41.1–78.1%), although the dosing is not specified [26, 27, 29, 30, 32]. This could be explained by a later incorporation of IXE into the PsA armamentarium, the consequent overlapping of physicians’ learning curve with the study period, and the different positioning of SECU after anti-TNF failure in Spain, unlike other countries, possibly resulting in a delayed treatment prescription [10].

Regarding persistence, the IXE cohort showed the highest rate at 1 year (86.4%). This result is in line with findings previously reported [22, 34], although in Perrone et al., more than 50% of patients were bio-naïve and 21.2% had been previously treated with SECU. In our study, new target drugs such as anti-IL23 were not yet available during the study period, and it is possible that the physicians retained their last treatment alternative even if a complete response was not reached in a refractory population. Interestingly, the persistence rate observed for IXE by Braña et al. [25] was lower than that reported in our study. A hypothetical explanation is that for more than 90% of the patients in that study, IXE was the third or subsequent line of treatment and, in contrast with our population, some of the patients had experienced a previous failure to IL-17 blockade with SECU. In the same line, Murage et al. [35] also reported a lower persistence rate with IXE. In their study, although the mean number of different b/tsDMARDs used by patients was lower than in our study (1.4 vs 2.4), almost 35% of patients had used SECU in the 12 months prior to initiating IXE.

Regarding persistence in the two SECU cohorts, our results also showed that SECU150 had a better persistence rate than SECU300, likely due to a better chance of response in a less active population. In 2020, Ramonda et al. [30] had already found similar results for SECU150. However, other studies only reported persistence rates for any dose at 1 year between those reported in this study; 73% by Perrone et al. [22], and 76% by Michelsen et al. [27].

In addition, patients included in the present study were more likely to discontinue anti-IL17 because of lack of effectiveness, followed by medical judgement or patient decision and finally by adverse reactions. To our knowledge, there is no other study analyzing these reasons by type of anti-IL17 and dose [22, 25–27, 32, 36]. Previous studies analyzing reasons for discontinuation by drug (SECU or IXE) agreed that lack of effectiveness and adverse events were the most important reasons; only the rates differed, and this was probably due to the different follow-up of the studies. In the PerfIL-17 study, the adverse events rates of the different anti-IL17 were low (10.5% for SECU300, 1.9% for SECU150, and 0% for IXE) which gives confidence in the safety profile of this class.

The PerfIL-17 study has several limitations. For example, first, given the retrospective nature of data collection, missing data may have resulted in a hidden or non-response bias in the results. Second, the sample size of SECU300 was relatively small, thus limiting the quality of data retrieved. All these limitations resulted from the descriptive nature of the persistence data of the three cohorts, precluding any kind of adjustment for possible baseline differences. The observed data, therefore, should not be directly compared, and any interpretation must be made with caution.

On the other hand, one of the main strengths of our study is that it provides valuable additional information about the use of anti-IL17 in patient profiles that are not usually considered in clinical trials (comorbidities, previous patient exposure to various b/tsDMARDs, etc.). Besides, the multicenter design can offer a reliable picture of the pattern of use and persistence of anti-IL17 for patients with PsA in routine clinical practice in Spain.

Conclusions

In the perfIL-17 study, most patients with PsA initiating anti-IL17 had moderate to severe disease activity, with predominant peripheral arthritis and skin manifestations, and had received at least one previous b/tsDMARD. At 1 year of follow-up, more than 80% of patients were still under the treatments, with IXE showing the highest persistence, followed by SECU150 then SECU300.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank all the subinvestigators (Alejandro Muñoz Jiménez, Virginia Coret Cagigal, Cristina Cris Valero Martínez, Irene Llorente Cubas, Javier Mendizábal Mateos, Loreto Horcada Rubio, Natividad Del Val Del Amo, Sara García Pérez, Vicente Aldasoro Cáceres, Cintia Garcia Rodriguez, Fermín Medina Varo, Isabel Serrano García, Salma Al Fazazi, Amalia Pérez Gil), and site data managers (Blanca Ortega Lérida, Paloma Jiménez Fernández, Maria Ángeles Belmonte López, Fátima Lozano Manchado, Maria José Soto Pino, Charo Santos Sarabia) for their contribution in the material preparation and data collection; Marina Hinojosa Campos, who provided medical writing assistance, Noelia Alfaro-Oliver for her contribution to the design of the study, the protocol and the CRF, and for her collaboration in reviewing the study results and Águeda Azpeitia for her contribution in the analysis of the data. The authors especially want to thank all the patients who participated in this study.

Medical Writing/Editorial Assistance.

Marina Hinojosa Campos from OXON Epidemiology gave medical writing assistance in the first draft of the manuscript. The medical writing was funded by Eli Lilly and Company.

Author Contributions

Beatriz Joven, Rosario García Vicuña, Mercedes Núñez, Silvia Díaz-Cerezo and Sebastian Moyano contributed to the conception and design of the study. Beatriz Joven, Esteban Rubio, Rosario García Vicuña, Concepción Fito Manteca, Enrique Raya, Sara Manrique, Alba Pérez and Raquel Hernández, as principal investigators in their sites contributed to the data collection Alessandra Lacetera contributed to the analysis of the data. All authors contributed to the manuscript review and approved its final version.

Funding

This study and its publication, including the journal’s Rapid Service and Open Access Fees, were funded by Eli Lilly and Company. The present manuscript represents the opinions of the authors and does not necessarily reflect the position of their employers.

Data Availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due to privacy and ethical restrictions.

Declarations

Conflict of Interest

Rosario García Vicuña, Concepción Fito Manteca, Esteban Rubio, Enrique Raya, Alba Pérez, Raquel Hernández, Sara Manrique and Alessandra Lacetera declare that they have no competing interests. Beatriz Joven has received speaker honoraria from Asociación Madrileña de Neurología and has received payments to support travel to meetings from Eli Lilly and Company, and Sebastian Moyano, Silvia Díaz-Cerezo and Mercedes Núñez are full time employees at Eli Lilly and Company and minor owners of Eli Lilly and Company shares.

Ethical Approval

The study was conducted in accordance with the ethical principles of the Declaration of Helsinki, the Good Pharmacoepidemiology Practices (GPPs) guidelines of the International Society for Pharmacoepidemiology, and local rules and regulations. The study was sent to the Spanish Health Authorities for classification and was subsequently evaluated and approved by a central ethics committee (Comité de Etica de la Investigación con medicamentos regional de la Comunidad de Madrid), and local ethics committees as required.

References

- 1.Mease PJ, van der Heijde D, Ritchlin CT, et al. Ixekizumab, an interleukin-17A specific monoclonal antibody, for the treatment of biologic-naive patients with active psoriatic arthritis: results from the 24-week randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled and active (adalimumab)-controlled period of the phase III trial SPIRIT-P1. Ann Rheum Dis. 2017;76(1):79–87. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2016-209709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ritchlin CT, Colbert RA, Gladman DD. Psoriatic arthritis. N Engl J Med. 2017;376(10):957–970. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1505557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fundación SER. Se ha presentado el Estudio EPISER 2016 en la sede del Ministerio de Sanidad, Consumo y Bienestar Social-SER. 2019. https://www.ser.es/se-ha-presentado-el-estudio-episer-2016-en-la-sede-del-ministerio-de-sanidad-consumo-y-bienestar-social/. Accessed 29 Jan 2020.

- 4.Cabrera-Salom C, Motta Beltrán A, Medina Y. Presentación inusual de psoriasis ostrácea y artritis psoriásica: resultados después de 10 años de manejo con infliximab. Revis Colomb Reumatol. 2019. https://www.elsevier.es/es-revista-revista-colombiana-reumatologia-374-pdf-S0121812318300367. Accessed 29 Jan 2020.

- 5.Coates L, Gossec L. The updated GRAPPA and EULAR recommendations for the management of psoriatic arthritis: similarities and differences. Jt Bone Spine. 2023;90(1):105469. doi: 10.1016/j.jbspin.2022.105469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Coates LC, Soriano ER, Corp N, et al. Group for Research and Assessment of Psoriasis and Psoriatic Arthritis (GRAPPA): updated treatment recommendations for psoriatic arthritis 2021. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2022;18(8):465–479. doi: 10.1038/s41584-022-00798-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Veale DJ, Fearon U. The pathogenesis of psoriatic arthritis. Lancet. 2018;391(10136):2273–2284. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)30830-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.de Vlam K, Gottlieb AB, Mease PJ. Current concepts in psoriatic arthritis: pathogenesis and management. Acta Derm Venereol. 2014;94(6):627–634. doi: 10.2340/00015555-1833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Torre Alonso JC, Del Campo D, Fontecha P, et al. Recommendations of the Spanish Society of Rheumatology on treatment and use of systemic biological and non-biological therapies in psoriatic arthritis. Reumatol Clin (Engl Ed) 2018;14(5):254–268. doi: 10.1016/j.reuma.2017.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.AEMPS. Informe de Posicionamiento Terapéutico de secukinumab (Cosentyx®) en artritis psoriásica. https://www.aemps.gob.es/medicamentosUsoHumano/informesPublicos/docs/IPT-secukinumab-Cosentyx-artritis-psoriasica.pdf. Accessed 29 Jan 2020.

- 11.EMA. Taltz Summary of Product Characteristics. European Medicines Agency. https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/medicines/human/EPAR/taltz. Accessed 29 Jan 2020.

- 12.AEMPS. Informe de Posicionamiento Terapéutico de ixekizumab (Taltz®) en el tratamiento de la psoriasis en placas. https://www.aemps.gob.es/medicamentosUsoHumano/informesPublicos/docs/IPT-ixekizumab-Taltz-psoriasis.pdf. Accessed 29 Jan 2020.

- 13.EMA. Cosentyx Summary of Product Characteristics. European Medicines Agency. https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/medicines/human/EPAR/cosentyx. Accessed 29 Jan 2020.

- 14.Novartis. Novartis receives approval for Cosentyx® label update in Europe to include dosing flexibility in psoriatic arthritis. https://www.novartis.com/news/media-releases/novartis-receives-approval-cosentyx-label-update-europe-include-dosing-flexibility-psoriatic-arthritis. Accessed 29 Jan 2020.

- 15.McInnes IB, Mease PJ, Kirkham B, et al. Secukinumab, a human anti-interleukin-17A monoclonal antibody, in patients with psoriatic arthritis (FUTURE 2): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2015;386(9999):1137–1146. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)61134-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mease PJ, Kavanaugh A, Reimold A, et al. Secukinumab provides sustained improvements in the signs and symptoms of psoriatic arthritis: final 5-year results from the phase 3 FUTURE 1 study. ACR Open Rheumatol. 2020;2(1):18–25. doi: 10.1002/acr2.11097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McInnes IB, Behrens F, Mease PJ, et al. Secukinumab versus adalimumab for treatment of active psoriatic arthritis (EXCEED): a double-blind, parallel-group, randomised, active-controlled, phase 3b trial. Lancet. 2020;395(10235):1496–1505. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30564-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McInnes IB, Mease PJ, Kivitz AJ, et al. Long-term efficacy and safety of secukinumab in patients with psoriatic arthritis: 5-year (end-of-study) results from the phase 3 FUTURE 2 study. Lancet Rheumatol. 2020;2(4):e227–e235. doi: 10.1016/S2665-9913(20)30036-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chandran V, van der Heijde D, Fleischmann RM, et al. Ixekizumab treatment of biologic-naïve patients with active psoriatic arthritis: 3-year results from a phase III clinical trial (SPIRIT-P1) Rheumatology (Oxford) 2020;59(10):2774–2784. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kez684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nash P, Kirkham B, Okada M, et al. Ixekizumab for the treatment of patients with active psoriatic arthritis and an inadequate response to tumour necrosis factor inhibitors: results from the 24-week randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled period of the SPIRIT-P2 phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2017;389(10086):2317–2327. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)31429-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Eder L, Chandran V, Ueng J, et al. Predictors of response to intra-articular steroid injection in psoriatic arthritis. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2010;49(7):1367–1373. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/keq102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Perrone V, Losi S, Filippi E, et al. Analysis of the pharmacoutilization of biological drugs in psoriatic arthritis patients: a real-world retrospective study among an Italian population. Rheumatol Ther. 2022;9(3):875–890. doi: 10.1007/s40744-022-00440-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gladman DC, Choquette D, Khraishi M, et al. Real-world retention and clinical effectiveness of secukinumab for psoriatic arthritis: results from the CanSpA Research Network. J Rheumatol. 2023;50(5):641–8. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 24.Reich A, Reed C, Schuster C, Robert C, Treuer T, Lubrano E. Real-world evidence for ixekizumab in the treatment of psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis: literature review 2016–2021. J Dermatol Treat. 2023;34(1):2160196. doi: 10.1080/09546634.2022.2160196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Braña I, Pardo E, Burger S, González del Pozo P, Alperi M, Queiro R. Treatment retention and safety of ixekizumab in psoriatic arthritis: a real life single-center experience. J Clin Med. 2023;12(2):467. doi: 10.3390/jcm12020467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Moreno-Ramos MJ, Sanchez-Piedra C, Martínez-González O, et al. Real-world effectiveness and treatment retention of secukinumab in patients with psoriatic arthritis and axial spondyloarthritis: a descriptive observational analysis of the Spanish BIOBADASER Registry. Rheumatol Ther. 2022;9(4):1031–1047. doi: 10.1007/s40744-022-00446-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Michelsen B, Georgiadis S, Di Giuseppe D, et al. Real-world six- and twelve-month drug retention, remission, and response rates of secukinumab in 2,017 patients with psoriatic arthritis in thirteen European countries. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2022;74(7):1205–1218. doi: 10.1002/acr.24560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Perrotta FM, Delle Sedie A, Scriffignano S, et al. Remission, low disease activity and improvement of pain and function in psoriatic arthritis patients treated with IL-12/23 and IL-17 inhibitors. A multicenter prospective study. Reumatismo. 2020;72(1):52–59. doi: 10.4081/reumatismo.2020.1266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Conaghan PG, Keininger DL, Holdsworth EA, et al. Real world effectiveness and satisfaction with secukinumab in the treatment of patients with psoriatic arthritis: a population survey in five European countries. Curr Med Res Opin. 2021;37(10):1845–1853. doi: 10.1080/03007995.2021.1954500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ramonda R, Lorenzin M, Carriero A, et al. Effectiveness and safety of secukinumab in 608 patients with psoriatic arthritis in real life: a 24-month prospective, multicentre study. RMD Open. 2021;7:1519. doi: 10.1136/rmdopen-2020-001519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Manfreda V, Chimenti MS, Canofari C, et al. Efficacy and safety of Ixekizumab in psoriatic arthritis: a retrospective, single-centre, observational study in a real-life clinical setting. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2020;38(3):581–582. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Valero-Expósito M, Martín-López M, Guillén-Astete C, et al. Retention rate of secukinumab in psoriatic arthritis: real-world data results from a Spanish multicenter cohort. Medicine (Baltimore) 2022;101(36):e30444. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000030444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gossec L, Baraliakos X, Kerschbaumer A, et al. EULAR recommendations for the management of psoriatic arthritis with pharmacological therapies: 2019 update. Ann Rheum Dis. 2020;79(6):700–712. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2020-217159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Joven B, Hernández Sánchez R, Pérez Pampín E, et al. CO22 use of Ixekizumab for psoriatic arthritis patients in real-world conditions. Value Health. 2022;25(12):S21. doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2022.09.102. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Murage MJ, Princic N, Park J, et al. Real-world treatment patterns and healthcare costs in patients with psoriatic arthritis treated with ixekizumab: a retrospective study. ACR Open Rheumatol. 2021;3(12):879–887. doi: 10.1002/acr2.11347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Conesa-Nicolás E, García-Lagunar MH, Núñez-Bracamonte S, García-Simón MS, Mira-Sirvent MC. Persistence of secukinumab in patients with psoriasis, psoriatic arthritis, and ankylosing spondylitis. Farm Hosp. 2020;45(1):16–21. doi: 10.7399/fh.11465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due to privacy and ethical restrictions.