Abstract

Geotrichum candidum can produce and excrete compounds that inhibit Listeria monocytogenes. These were purified by ultrafiltration, centrifugal partition chromatography, thin-layer chromatography, gel filtration, and high-pressure liquid chromatography, and analyzed by liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry, infrared spectrometry, nuclear magnetic resonance spectrometry, and optical rotation. Two inhibitors were identified: d-3-phenyllactic acid and d-3-indollactic acid.

Contamination by Listeria has become a problem over the past 20 years in many parts of the world. The ubiquitous nature of Listeria monocytogenes, its capacity to multiply at refrigeration temperatures, its thermal tolerance (11), and its resistance to relatively low pH (it can multiply at pH 5.3 and 4°C and at pH 4.39 and 30°C) (5), together with its tolerance of high salt concentrations (4, 18), make controlling this potentially pathogenic microorganism in food products difficult. This bacterium has been incriminated in several cases of food poisoning (2, 10, 19). At risk are the immunodepressed, the old, pregnant women, fetuses, and newborn babies. Several groups have worked on biological control. As a result, many bacteriocins, which inhibit the growth of L. monocytogenes, have been isolated, purified, and characterized (12, 13, 16, 18). We have worked with Geotrichum candidum, a yeast-like member of the natural milk flora that is used as a maturing agent for soft and hard cheeses. In an extensive study carried out in 1984 (7), the interactions between G. candidum and the microflora in cheeses were examined. G. candidum inhibited the growth of gram-negative bacteria, gram-positive bacteria, and fungi (6). We recently showed (3) that G. candidum inhibits the growth of L. monocytogenes on both solid and liquid media (a bacteriostatic effect). The inhibitors are stable over a wide pH range and can be heated to 120°C for 20 min. The present report describes the purification and characterization of compounds responsible for this antibacterial action.

Microorganisms, culture conditions, and detection of inhibitory activity.

The strain of G. candidum used came from the collection of the Caen University Food Microbiology Laboratory, Caen, France (UCMA G91) and was initially isolated from a cheese, Pont l’Evêque. One percent of a preculture (optical density at 620 nm [Milton Roy Spectronic 301; Bioblock Scientific, Illkirch, France] of 0.7 [107 arthrospores or hyphae/ml]) of G. candidum was grown in a fermentor (20 liters; Biolafitte type PI) in 15 liters of Trypticase soy broth (30 g/liter; Biomerieux, Marcy l’Etoile, France) with yeast extract (6 g/liter; AES, Combourg, France) (TSBYE) buffered to pH 6.3 with 0.1 M citrate-0.2 M phosphate. The culture was stirred at 300 rpm for 64 h at 25°C under a pressure of 0.2 bar and was then filtered through a 1,000-Da cut-off membrane by tangential ultrafiltration (Sartorius, Palaiseau, France) under a pressure of 2 bars. The resulting ultrafiltrate was sterilized by passage through a capsule (Sartorius) containing 0.45-μm- and 0.2-μm-pore-size membranes.

The inhibition of L. monocytogenes was checked at each purification step by the agar diffusion well assay (3). Antimicrobial activity was estimated by measuring the diameter of the inhibitory halo on two right-angle axes (average of two plates). The strain of L. monocytogenes (UCMA L205) (serovar 1/2a; Centre National de Référence des Listeria, Nantes, France) and lysovar 1652 (Institut Pasteur, Paris, France) came from the laboratory collection and was isolated from milk. The initial lyophilized ultrafiltrate (900 mg/ml) gave a halo diameter of 36 ± 0.7 mm in the inhibition assay.

Purification.

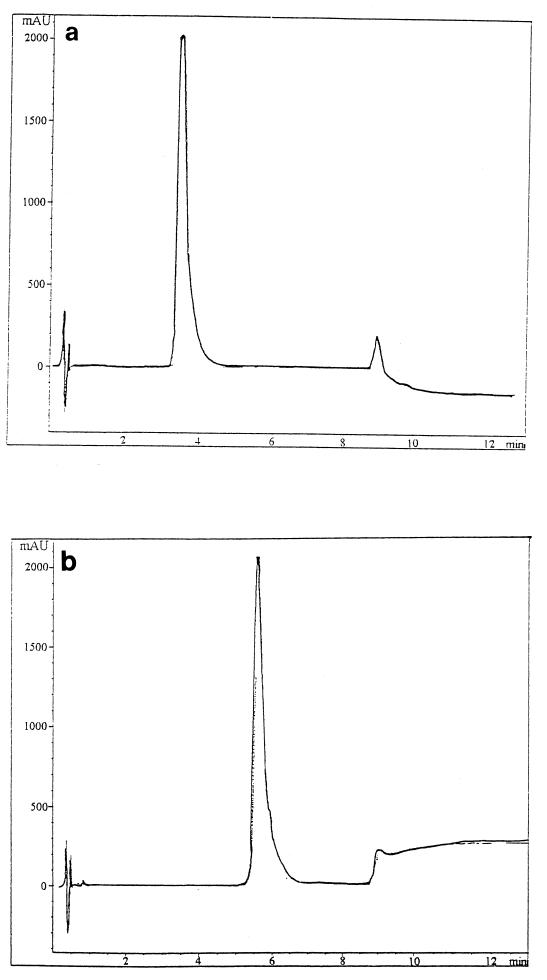

Samples of ultrafiltrate (20 μl) were spotted on thin-layer chromatography (TLC) plates (silica gel, 10 by 5 cm, 0.25 mm thick, 60 F254; Merck, Darmstadt, Germany), with 20 μl of TSBYE for controls, and eluted by vertical chromatography with a butanol-acetic acid-water (40:10:20 [vol/vol/vol]) solvent system. The bands were examined under UV light (254 nm) or after treatment with Ehrlich’s reagent. Four well-separated bands were found (Rfs, 0.11 ± 0.04; 0.41 ± 0.04; 0.7 ± 0.03; and 0.86 ± 0.03), but only the band with an Rf of 0.7 ± 0.03 differed from that of control preparations (TSBYE not containing G. candidum). The microbiological bioautography test (1) confirmed the presence of the inhibitor in the band with an Rf of 0.7. Lyophilized ultrafiltrate was subjected to centrifugal partition chromatography (Sanki 1000 Engineering Ltd.; EverSeiko, Tokyo, Japan) in butanol-acetic acid-water (40:10:50 [vol/vol/vol]). Partitioning was carried out under the following conditions: ascending mode, 1,200 rpm; flow rate, 3 ml/min; pressure, 40 bars. An aliquot of material (3 g) previously equilibrated with the solvent system was injected into the separatus via a 12-ml injection loop. Fractions (10 ml each) were collected and evaporated to dryness in a SpeedVac (Jouan RC 1022, Saint Herblain, France). The dried extracts of certain fractions were taken up in 800 μl of water and brought to pH 5.6 with 0.2 M NaOH. A total of 10 mg of pooled fractions with an Rf close to 0.7 and showing L. monocytogenes inhibitory activity (36 ± 0.7 mm for a solution of 38 mg/ml) was taken up in 250 μl of methanol-water (50:50 [vol/vol]) and automatically deposited (Camag Linomat) on a 10- by 20-cm TLC plate (silica gel, 0.25 mm thick, 60 F254; Merck). The plate was developed with butanol-acetic acid-water (40:10:20 [vol/vol/vol]) and examined under UV light. Bands with an Rf of 0.7 were scraped off and placed in methanol. The silica was washed several times and removed by centrifugation and filtration through a 0.2-μm-pore-size filter. An aliquot (20 μl) was spotted on a small silica TLC plate to confirm elution of the solute by the methanol solvent. The purity of the band with an Rf of 0.7 was confirmed by high-pressure liquid chromatography (HPLC) coupled with a photodiode array detector at 206 and 222 nm (solvent A: 0.1% formic acid in water; solvent B: CH3CN-H2O [95:5] plus 0.1% formic acid) on a C18 Grom-Sil ODS2 column (4.6 by 30 mm; particle size, 1.5 μm; Grom Analytic, Herrenberg, Germany) at the flow rate of 1 ml/min. Inhibitory activity was assessed as above. Preparative TLC indicated that the band with an Rf of 0.7 contained two components, one eluting at 4.5 min on HPLC (peak 1) and the other at 5.5 min (peak 2). The latter fraction gave an inhibitory halo of 36 ± 0.7 mm at a concentration of 20 mg/ml (a 45-fold purification over the ultrafiltrate). The material from preparative TLC (40 mg in 200 μl of methanol-water) was placed on a column of Sephadex LH20 (1 m by 1 cm; Pharmacia), and the column was eluted with methanol-water at 12 ml h−1. Fractions (1 ml each) were collected and examined by HPLC to determine the material in each fraction. This final purification on Sephadex LH20 gave two peaks, with two-thirds of the eluate at peak 1 and one-third at peak 2 (Fig. 1). As the concentration for peak 2 was very low, only the inhibitory activity for peak 1 was assayed. A concentration of 20 mg/ml gave a halo diameter of 26 ± 0.7 mm.

FIG. 1.

Reverse-phase liquid chromatography (HPLC) of inhibitory compounds of G. candidum after purification by centrifugal partition chromatography, preparative TLC, and Sephadex LH20 gel filtration. Column, C18 Grom-Sil ODS2 column (4.6 by 30 mm; particle size, 1.5 μm; Grom Analytic). Eluent: solvent A (0.1% formic acid in water), solvent B (CH3CN-H2O [95:5] plus 0.1% formic acid). Flow rate, 1 ml/min. (a) Product 1 (detection at 206 nm); (b) product 2 (detection at 222 nm).

Characterization.

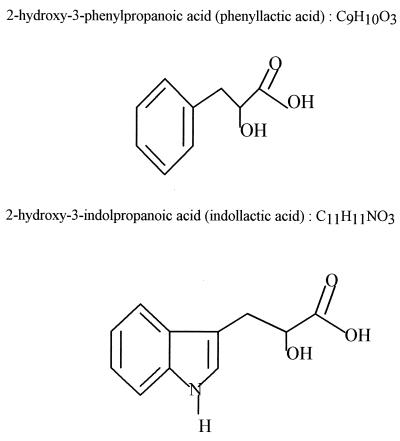

The pooled fractions were run on HPLC with a Grom-Sil ODS2 column coupled to a mass detector (Sciex Api III, triple quadrupole; Thornhill, Canada). Product 1, analyzed by desorption and chemical ionization, gave a signal at an m/z of 184 for (M+ NH4)+ on desorption and chemical ionization and thus had a mass of 166. Product 2 was analyzed by ion spray and gave a signal at an m/z of 297 (M + 4 Na)+ for a mass of 205. Spectra were determined in a Nicolet model 60 SXR FT-IR. Samples were dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide, and the 1H and 13C resonances were measured in a Brucker spectrometer at 200 and 400 Hz, respectively. The purified material was taken up in methanol, and the isomeric form of the substance(s) inhibiting L. monocytogenes was determined in a Perkin-Elmer model 341 polarimeter. Two inhibitors were identified (Fig. 2); product 1 was 2-hydroxy-3-phenylpropanoic acid (phenyllactic acid, mass 166), and product 2 was 2-hydroxy-3-indolpropanoic acid (indollactic acid, mass 205). The rotation of polarized light showed that the phenyllactic acid produced by G. candidum was the d form. The spectrum properties of the isolated compounds are identical to those of authentic commercial compounds (Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, Mo.). d-Phenyllactic acid can be purchased from Aldrich (product no. 37 690-6), and dl-indollactic acid is available from Sigma (catalog no. I2875). Inhibitory activity with commercial compounds showed that dl-phenyllactic acid (Sigma catalog no. P7251) was a stronger inhibitor of Listeria than dl-indollactic acid (34 and 26 ± 0.7 mm for 187 mM, respectively) and that the d form of phenyllactic acid was more active (38 mm for 120 mM) than the l form (Aldrich 11, 306-9, 30 mm for 120 mM). The samples were taken up in methanol-water (50:50 [vol/vol]) and brought to pH 5.6 (Table 1).

FIG. 2.

Structure of two inhibitory compounds of G. candidum characterized by LC-mass spectrometry, infrared spectrometry, nuclear magnetic resonance spectrometry, and optical rotation.

TABLE 1.

Anti-Listeria activity of phenyllactic acid and indollactic acida

| Compound | Form | Concn | Inhibitory diam (mm) ± 0.7 mm |

|---|---|---|---|

| Phenyllactic acid | dl | 187 mM (30 mg/ml) | 34 |

| Indollactic acid | dl | 187 mM (38 mg/ml) | 26 |

| Phenyllactic acid | d | 120 mM (20 mg/ml) | 38 |

| Phenyllactic acid | l | 120 mM (20 mg/ml) | 30 |

| Phenyllactic acid | d | 60 mM (10 mg/ml) | 32 |

| Phenyllactic acid | dl | 70 mM (13 mg/ml) | 30 |

The agar diffusion well assay was performed with an 18-mm-diameter well. All samples were brought to pH 5.6. Antimicrobial activity was estimated by measuring the diameter of the inhibitory halo on two right-angle axes (average of two plates [standard error of the mean, 0.7 mm]).

Phenyllactic and indollactic acids are compounds used for the synthesis of the amino acids phenylalanine and tryptophan (17), so they could be precursors of these amino acids. To our knowledge, their anti-Listeria actions have not previously been demonstrated. Only one study, carried out in 1976 (15), mentioned the antibacterial properties of β-indollactic acid, produced by Candida species, toward certain gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria (Escherichia coli and Bacillus cereus). Experiments with [14C]phenylalanine indicated that 2-phenyllactic acid is synthesized from l-phenylalanine (14). Kamata et al. (9) stated in a patent application that mutants of Brevibacterium lactofermentum produce d-3-phenyllactic acid (1.94 g/liter). By comparison, G. candidum grown in TSBYE produces about 0.6 to 1 g of d-3-phenyllactic acid per liter. No toxicological studies have been done on d-phenyllactic acid. Tharrington et al. (20) mentioned that Lactobacillus delbrueckii subsp. lactis produced lactic and acetic acids and can inhibit the growth of L. monocytogenes. The inhibitory properties of lactic acid are due to its acid nature, not to the molecule itself. dl-Lactic acid (120 mM) at pH 5.6 had no action against L. monocytogenes in the agar-well test, while 120 mM d-phenyllactic acid at the same pH gave an inhibitory halo of 37 ± 07 mm in diameter.

Acknowledgments

This study was financed by Texel (Rhone Poulenc Rorer).

We thank V. Martin of Texel and M. Mathieu and J. Henry of the University of Caen for technical assistance. We are grateful to M. Leboul of the Rhone Poulenc Rorer research facility at Vitry-Alfortville and to R. Pollien and T. Flamant and the other members of the group for valuable assistance. We thank S. Perrio of I.S.M.R.A., Caen, France, for his help in RMN spectrum analyses.

REFERENCES

- 1.Betina V. Bioautography in paper and thin layer chromatography and its scope in the antibiotic field. J Chromatogr. 1973;78:41–51. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9673(01)99035-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Borde V. La Listeria bouleverse l’hygiène alimentaire. Ind Tech. 1993;735:19–20. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dieuleveux, V., J. Chataud, and M. Guéguen. Inhibition of Listeria monocytogenes by Geotrichum candidum. Submitted for publication.

- 4.Doyle M P. Effect of environmental and processing conditions on Listeria monocytogenes. Food Technol. 1988;42:169–171. [Google Scholar]

- 5.George S M, Lund B M, Brocklehurst T F. The effect of pH and temperature on initiation of growth of Listeria monocytogenes. Lett Appl Microbiol. 1988;6:153–156. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Guéguen M, Delespaul G, Lenoir J. La flore fongique des fromages de Saint Nectaire et Tome de Savoie. II. Les conditions de développement. Rev Lait Fr. 1974;325:795–816. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Guéguen M. Contribution à la connaissance de Geotrichum candidum et notamment de sa variabilité. Conséquences pour l’industrie fromagère. Thèse Doctorat d’Etat. Caen, France: Université de Caen; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hechard Y, Renault D, Cenatiempo Y, Letellier F, Maftah A, Jayat C, Bressolier P, Ratinaud M H, Julien R, Fleury Y, Delfour A. Les bactériocines contre Listeria: une nouvelle famille de protéines? Lait. 1993;73:207–213. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kamata, M., R. Toyomasu, D. Suzuki, and T. Tanaka. May 1986. d-phenyllactic acid production by Brevibacterium or Corynebacterium. Brevet. Ajinomoto Co., Inc., Japan, Patent JP 86108396.

- 10.Kaufmann U. Comportement de Listeria monocytogenes pendant la fabrication de fromages à pâte dure. Rev Suisse Agric. 1990;22:5–9. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mackey B M, Bratchell N. The heat resistance of Listeria monocytogenes: a review. Lett Appl Microbiol. 1989;9:89–94. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Malik R K, Kumar N, Rao K N, Mathur D K. Bacteriocins—antibacterial proteins of lactic acid bacteria: a review. Microbiol Alim Nut. 1994;12:117–132. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Muriana, P. M. 1996. Bacteriocins for control of Listeria spp. J. Food Prot. 1996(Suppl.):54–63. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 14.Narayanan T K, Rao G R. Production of 2-phenethyl alcohol and 2-phenyllactic acid in Candida species. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1974;58:728–736. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(74)80478-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Narayanan T K, Ramananda Rao G. Beta-indoleethanol and beta-indolelactic acid production by Candida species: their antibacterial and autoantibiotic action. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1976;9:375–380. doi: 10.1128/aac.9.3.375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Piard J C, Desmazeaud M. Inhibiting factors produced by lactic acid bacteria. 2. Bacteriocins and other antibacterial substances. Lait. 1992;72:113–142. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sato, K., H. Ito, H. Ei, and M. Kamata. September 1986. Microbial conversion of phenyllactic acid to l-phenylalanine. Brevet. Ajinomoto Co., Inc., Japan. Patent JP 86212293.

- 18.Seeliger H P R. Listeriosis. New York, N.Y: Hafner Publishing Co.; 1961. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shofield G M. Emerging food-borne pathogens and the significance in chilled foods. J Appl Bacteriol. 1992;75:267–273. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.1992.tb01834.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tharrington G, Sorrells K M. Inhibition of Listeria monocytogenes by milk culture filtrate from Lactobacillus delbrueckii subsp. lactis. J Food Prot. 1992;55:542–544. doi: 10.4315/0362-028X-55.7.542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]