Abstract

Federal race and ethnicity data standards are commonly applied within the state of Hawai‘i. When a multiracial category is used, Native Hawaiians are disproportionately affected since they are more likely than any other group to identify with an additional race or ethnicity group. These data conventions contribute to a phenomenon known as data genocide – the systematic erasure of Indigenous and marginalized peoples from population data. While data aggregation may be unintentional or due to real or perceived barriers, the obstacles to disaggregating data must be overcome to advance health equity. In this call for greater attention to relevant social determinants of health through disaggregation of race and ethnicity data, the history of data standards is reviewed, the implications of aggregation are discussed, and recommended disaggregation strategies are provided.

Keywords: Native Hawaiian, Pacific Islander, data disaggregation, data standards, race and ethnicity, multiracial, indigenous health, data genocide

Background

The COVID-19 pandemic demonstrated the critical importance of timely and relevant demographic data.1–3 Commonly measured factors associated with health outcomes include age, gender or sex, and race and ethnicity. National standards for the collection of race and ethnicity are set by the Office of Management and Budget (OMB), which defines race as having to do with a person’s “origins”.4 The OMB further clarifies that responses are based on self-identification and should not be interpreted primarily as biological or genetic constructs but as social, cultural, and ancestral characteristics.

These present-day race categories are an unfortunate legacy of a time in America’s history when proportional democratic representation was allocated according to the number of White and enslaved (Black) persons in each state.5 Additional categories were later added to support immigration policies, but following the civil rights movement of the 1960s, racial statistics were repurposed to support the enforcement of civil rights laws aimed at equal access to housing, education, and employment. Today, these “statistical race” categories are often used in health research as a proxy for racial discrimination and other historical and contemporary systemic factors that affect social determinants of health.6,7

The first national race and ethnicity data standard was established in 1977, with OMB Directive 15.8 This mandate included Asian American or Pacific Islander (AAPI) as 1 of 5 minimally required racial and ethnic groups. These standards were revised in 1997 in response to robust community advocacy with the addition of the Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander (NHPI) group as a new minimum category distinct from Asian Americans. Yet more than 25 years later, many states and federal agencies still fail to abide by the 1997 race and ethnicity standard.9 By continuing to use the broader AAPI label, these organizations render smaller NHPI communities invisible. Although the OMB race and ethnicity standards are currently under review,10 it is unlikely that any national standard for race and ethnicity data will meet the needs of Hawai‘i’s more diverse population. Hawai‘i is the only state where Asians, Native Hawaiians, and Pacific Islanders collectively comprise a majority of the population.

Diversity Among NHPI Populations

The inadequacy of the federal minimum race categories is clear when examining social determinants of health within these statistical racial groups. Heterogeneity among the NHPI population across a wide range of socioeconomic and demographic indicators has been documented using the American Community Survey and other data sources.11,12 Variation exists among the NHPI community for bachelor’s degree attainment (2.6%-16.4%), per capita income ($5963-$20 664), limited English proficiency (2%-51%), and home ownership (3%-54%).11,12

While the people living in Hawai‘i who have ancestry from any of the thousands of islands spanning the vast Pacific Ocean may share certain commonalities of environment, climate, or colonial histories, each island population possesses a distinct history, culture, social, and political affiliation with the US. Additional differences stem from the status of Native Hawaiians as an Indigenous population in contrast to Pacific Islanders who have immigrated to Hawai‘i at different times and for different economic and political reasons.13

Diversity Among Pacific Islander Populations

As of 2010, there were 13 distinct non-Hawaiian Pacific Islander populations with at least 100 members living in Hawai‘i, collectively comprising 4-5% of the state’s population.14 According to principles of epidemiologic analysis of categorical data, categories should be constructed based on external information, and groups that are different with respect to the phenomena under study should not be combined.15 For example, when Pacific Islanders are combined with Native Hawaiians, any aggregate NHPI statistics will primarily reflect the experience of the larger Native Hawaiian population, concealing any disparities that might exist within the smaller Pacific Islander population. Without oversampling by design, few surveys can make statistically reliable or meaningful conclusions about Pacific subpopulations. And yet, each of these groups has a unique history, political, and socioeconomic status that contributes to their overall health status.16 Attempts to stratify this diverse population into statistically manageable subgroups have often relied on the geographic regions of origin such as Micronesia, Polynesia, and Melanesia. or by political affiliation with the US, such as the Compacts of Free Association (COFA).

While convenient for data tabulation, these broad, umbrella terms perpetuate reductive stereotypes that are not meaningful to Pacific Islanders and are uninformative for public health interventions. These geographic regions in the Pacific were originally created by a French explorer and naval officer named Jules Sébastien César Dumont D’Urville based on racial biases and assumptions.17 As the Samoan poet Albert Wendt has described, these “fictional” 18 categories are based on externally and artificially imposed boundaries that often pose a barrier to meaningful engagement since there is no distinct regional language or culture for Micronesia, Polynesia, or Melanesia. During the COVID-19 pandemic in Hawai‘i, disaggregated Pacific Islander data supported the creation of a team of community health workers who were better equipped to establish trust and translate ever-changing health guidance using their deep and specific knowledge about the cultures and languages of each of the affected island nations. -

Multiracial Diversity

A second major change established by the 1997 OMB standard included the requirement to allow respondents to identify with more than 1 race. Data from the 2020 census reveals a rapidly increasing multiracial population nationally, with Hawai‘i having the largest multiracial proportion at 27% based on the OMB minimum categories.19 While placing all persons who select more than 1 race into a single multiracial category complies with minimum reporting requirements and creates mutually exclusive groupings, it is also possible toprovide the number of persons who identify with each race “alone or in combination” with any other race. The conventional approach of reporting 1 multiracial category and listing only those who identify with a single race “alone” disproportionately affects Indigenous peoples who have managed to survive through generations of intermarriage after having their populations reduced to near extinction by disease and systematic violence.

Historians estimate that the Native Hawaiian population declined from as many as 700 000 – 1 000 00020 to roughly 30 000 following American and European contact and subsequent immigration from east Asia.13,20,21 For this reason, the Native Hawaiian Health Act of 1988 defined Native Hawaiian as a person who is a “descendent of the aboriginal people who, before 1778, occupied and exercised sovereignty in the area that now comprises the State of Hawai‘i.”22 This recognizes the need for an inclusive definition that accounts for the impact of colonialism initiated when Captain James Cook arrived on the shores of the Hawaiian Islands.

Impact of Data Aggregation

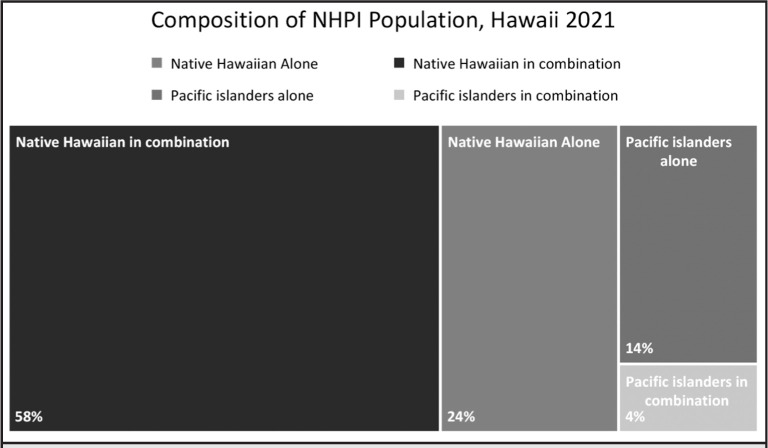

In 2021, 71% of Native Hawaiians also identified with at least 1 other race in the American Community Survey. When data are reported using a “Native Hawaiian alone” category and a single multiracial category, the result is an effective reduction in the Native Hawaiian-identifying population by over two-thirds (Table 1). Over half of Native Hawaiians are therefore made invisible in the data when combined with all other multiracial populations. Similarly, Pacific Islanders are disproportionately affected when NHPI are reported as a single group since they represent just just one-sixth of all persons who identify as NHPI living in the state. Any health disparities between Pacific Islanders and Native Hawaiians are masked when combined with the much larger Native Hawaiian population (Table 1). Statistics describing the combined NHPI group will inevitably reflect the Native Hawaiian experience, which can differ considerably from the Pacific Islander experience depending on the factors under study.

Table 1.

Native Hawaiian and Pacific Islander Population Estimates for the State of Hawai‘i, by Classification Method, American Community Survey 2021, Table S0201

| Race Alone | Race Alone or in combination | |

|---|---|---|

| Total Population | 1 441 553 | 1 441 553 |

| NHPI | 145 556 (10.1%) | 380 825 (26.4%) |

| Native Hawaiian | 90 370 (6.3%) | 309 807 (21.5%) |

| Pacific Islanderb | 55 186 (3.8%) | 71 018 (4.9%) |

Not including Native Hawaiians

NHPI = Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander

Practical and Ethical Implications of Aggregation

Adherence to the OMB standards for racial classification is not without negative consequences. Failure to collect and report data beyond the minimum federal categories in populations with large racial and ethnic diversity within these categories contributes to the ongoing marginalization of historically oppressed populations. When broad categories like “Native Hawaiian and Other Pacific Islander” and “Multiracial”, are used to describe people living in Hawai‘i, any underlying health disparities within these groups are masked, diverse experiences are erased, and efforts to improve outcomes for those facing the greatest systemic barriers are unnecessarily delayed.

The undercounting and misclassification of marginalized populations reinforces the hegemonic dominance of the majority at the expense of populations with the greatest social needs. This phenomenon of systematic erasure is frequently experienced by Indigenous and immigrant populations who have been subjected to American colonialism and military occupation. American Indian and Alaska Native (AIAN) data advocates have described the statistical suppression of their populations as data genocide.23,24 This insidious form of racism is a contemporary expression of more overt historical discrimination against minoritized populations. When attempts to exterminate Indigenous peoples through state-sanctioned violence were unsuccessful, other compulsory acculturation strategies were employed, such as forcibly placing Native youth into boarding schools to “kill the Indian, save the man.”25 Similar efforts were made to eradicate or limit Native Hawaiian identity through suppression of the Hawaiian language and practices. The teaching of Hawaiian language was banned from schools and was also discouraged from being spoken at home. Beginning in 1906, the Programme for Patriotic Exercises in the Public Schools attempted to Americanize the Hawaiian children by severely punishing them if they spoke Hawaiian at school.26 Although the aggregation or outright omission of NHPI data represents a form of racism, individual instances of aggregation may be warranted when there are concerns about protecting privacy, avoiding stigmatization, or ensuring statistical reliability. However, these concerns must be weighed against the critical need for better data to uplift historically underserved communities, with intentional equity-focused efforts designed to address the marginalization that can manifest in the absence of data about certain communities.

National NHPI Disaggregation Efforts

The imperative to disaggregate data has been highlighted by numerous health policy advocates who point to data reporting gaps for NHPI as a form of structural racism.9,27,28 Among those calling for better data are the Asian American (AA) and NHPI Interest Group of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) Community Engagement Alliance Against COVID-1929 and the President’s Advisory Commission on Asian Americans, Native Hawaiians, and Pacific Islanders.30 Community advocacy in several continental US jurisdictions has resulted in legislation mandating data disaggregation by government agencies such as in New York State (A6896), 31 California (AB1726),32 Oregon (REALD),33 Massachusetts (H3361),34 and Rhode Island (H5453).35 Surprisingly, the State of Hawai‘i lags behind these states in the development of racial disaggregation and standards legislation, despite having greater proportional representation from AA and NHPI populations.

Local Efforts

During the pandemic in Hawai‘i, advocacy by NHPI community leaders and organizations associated with the Hawai‘i NHPI Response, Recovery, and Resiliency Team (NHPI 3R) led to the creation of an NHPI-specific contact tracing team. Leaders and members of the affected communities advocated for the continued collection and reporting of detailed COVID-19 race and ethnicity data.36,37 Without disaggregated data, the COVID-19 disparities within the NHPI and Asian populations would have remained hidden, unnecessarily delaying the use of tailored, culturally responsive efforts. Some Department of Health programs have been disaggregating NHPI data for decades.38 However, racial and ethnic reporting often regresses to the minimum required standard, likely related to dependence on federal resources (eg, data collection forms), information system limitations, and the convenience of tabulating groups using broader population categories.

A Way Forward

It has been said that inequity stems from power imbalances since health and other policies have been shaped by legacies of racial, economic, and political exclusion and segregation.39,40 If those in positions of authority to set research agendas, dictate data reporting standards, and conduct public health research fail to challenge the status quo, the result will be the perpetuation of marginalizing and oppressive systems that favor historically privileged social groups. Rather than continuing to be unwittingly complicit in harmful or unhelpful data practices, health researchers and health officials in Hawai‘i are in a position to become national leaders in demonstrating how to thoughtfully disaggregate data for diverse, multiracial populations.

One of the principles underlying health equity is the notion that one size does not fit all. If equality of health outcomes is to be achieved, then it must include tailored and focused policy interventions that account for root causes such as the longstanding historical, social, and political conditions that have created those inequalities.41 Without disaggregated public health data, there can be no accountability or monitoring of progress toward correcting the systemic racism that has pervaded America’s history.

To estimate how frequently NHPI data is aggregated in Hawai‘i, the authors identified 35 articles based on research published in the Hawaii Journal of Health & Social Welfare between 2020-2022 and that provided any demographic details about the study population. Among these studies, only one-third (34%) presented the race and ethnicity data in disaggregated form. The remaining two-thirds of studies combined Native Hawaiians with Pacific Islanders and/or included Native Hawaiians in a multiracial category. For the 12 such studies published in 2022, this figure was much lower: just 8% (n=1) presented data separately for Native Hawaiians and Pacific Islanders. These examples demonstrate that the aggregation of Native Hawaiians and Pacific Islanders remains a common practice in health research and more work is needed to improve the quality and relevance of data about racial and ethnic disparities in Hawai‘i.

While research priorities and resource limitations may not always allow for the oversampling needed to draw conclusions about specific Native Hawaiian and Pacific Islander subpopulations, programs that serve these communities broadly should not assume that the subgroups are monolithic. Instead, public health programs and biomedical research should dedicate resources to collecting detailed and relevant demographic information that will support appropriately stratified analyses and ensure that culturally appropriate and language-specific resources are made available during all health interactions. Table 2 provides a list of considerations for population researchers when conducting studies within the state of Hawai‘i. The list is based on the decades of experience of the authors in working directly with these communities and analyzing population datasets. Although not responsible for collecting data, journal editors can also support data disaggregation by encouraging robust methods during the review process and requesting that authors provide an explanation of barriers encountered during the collection or tabulation process that might have prevented appropriate disaggregation. Engagement with affected communities throughout the research process will ensure meaningful categories are used so that relevant and actionable data can be made available to empower communities and create policies that promote social justice and health equity. Finally, Table 3 provides a series of strategies that can be used to overcome the most common barriers to disaggregation. Although the application of socially and culturally relevant categories may entail costs associated with additional effort and resources, the benefits of having more granular race and ethnicity data will often outweigh these costs. Once disaggregation becomes the commonly accepted standard, future costs will be greatly reduced as tools and methods that support increased data disaggregation are developed and shared.

Table 2.

Recommendations for Health Researchers and Journal Editors When Conducting and Reviewing Studies that Include Diverse Populations, Especially those that Make Ethnic Comparisons

| 1. Consider the relevance of social factors associated with race and ethnicity that go beyond federal Office of Management and Budget (OMB) minimum standards for the collection, analysis, and reporting of population health data. Avoid statements that imply that race is measure of biological or genetic traits and instead describe race as a social construct and proxy for systemic racism and social determinants of health. |

| 2. Provide the total number of persons who identify as Native Hawaiian, whether alone or in combination with some other race. Do not divide Native Hawaiians into separate single race and multiracial categories |

| 3. Separate Pacific Islanders from Native Hawaiians, and to the extent possible, further separate Pacific Islander subpopulations from each other. Do not use a single NHPI category. If disaggregation would result in small numbers, apply cell suppression rules (eg, counts between 1 and 9 and rates based on fewer than 20 events not displayed). |

| 4. When in doubt about appropriate racial categorization, consult with Native Hawaiian and Pacific Islander subject matter experts or organizations or identify examples in the literature. |

Note: These recommendations are compliant with the 1997 OMB standards and are explicitly endorsed in federal guidance which states that “in no case shall the provisions of the standards be construed to limit the collection of data to [these] categories” and that “the collection of greater detail is encouraged”, so long as “additional categories can be aggregated into these minimum categories. Regarding respondents who select more than 1 category: “data producers are strongly encouraged to provide the detailed distributions, including all possible combinations of multiple responses to the race question” and suggest that data producers “report the total selecting each particular race, whether alone or in combination with other races.”

Table 3.

Common Barriers and Strategies for Data Disaggregation

| Barrier | Strategy |

|---|---|

| Small sample, insufficient data | Oversample small populations of interest |

| Use small sample statistical methods (nonparametric tests, exact statistics, eg, Fisherés exact test, Welchés t-test or ANOVA)42,43 | |

| Display 0 and censored cells in tables with footnotes instead of aggregating disparate groups to avoid suppression. | |

| Pool samples across space (geography) or time (multiple years of data) | |

| Provide confidence intervals or notes regarding instability of estimates based on small numbers. | |

| Use discussion section to describe efforts or barriers to enumeration and inclusion or why aggregation is appropriate for study hypothesis and why future work is needed to explore phenomena within subpopulations. | |

| Lacking data collection tools | Use census-style race data collection tools that provide separate check boxes for Native Hawaiians and Pacific Islander populations. |

| Develop forms that expand upon the census race and ethnicity questions by adding more detailed groups. | |

| Create and share population reference data, data collection tools and sample analyses through open-source platforms (eg, GitHub). | |

| Lacking expertise in racial analysis | Follow examples where data has been disaggregated. |

| Seek out consultation or guidance from organizations and researchers with prior experience, especially when inferences or conclusions are made about historically marginalized populations. |

Conclusion

Racial and ethnic data aggregation practices can result in a form of erasure called data genocide and represent an insidious example of systemic racism that is a major obstacle to achieving health equity. Structural racism and settler colonialism can manifest as limited data on health disparities for historically underserved and marginalized communities.9 Although there may be practical reasons for aggregating racial data, the negative impact of failing to disaggregate outweighs these concerns and justifies the use of innovative strategies to overcome common barriers.

The aggregation of NHPI groups, as well as the use of a single “Multiracial” category containing many of these individuals, detracts from the value of important health studies since over half of the Native Hawaiians in study populations are likely to be counted in the multiracial category and Pacific Islander disparities are masked by the larger Native Hawaiian group. When insurmountable barriers beyond the control of the researchers exist (eg, use of secondary data sources relying on federal data collection tools) researchers should describe these limitations in the text and highlight the need for additional research to understand whether patterns observed in the aggregate are applicable to subpopulations or if effects are modified by culture, language, racism, or other factors associated with race and ethnicity. Researchers should expect marked heterogeneity within the NHPI population unless the data or prior studies show otherwise. If the purpose of the study is to make inferences about Native Hawaiians or Pacific Islanders, then sample size calculations should be done prior to the study to ensure sufficient statistical power during the design and data collection phases.

Several efforts are underway nationally to promote greater data disaggregation. Thoughtful attention to social, cultural, and historical context during the study design, data collection, analysis, and reporting phases of health research will result in a more robust and relevant evidence base for policymakers and health practitioners. If the goal of health research is to create actionable data that promotes the health of all, then greater data disaggregation by race and ethnicity is imperative.

Figure 1.

Native Hawaiian and Pacific Islander Population Estimates for the State of Hawai‘i, by Classification Method, American Community Survey 2021, Table S0201

Abbreviations

- AA

Asian American

- AAPI

Asian American and Pacific Islander

- AIAN

American Indian and Alaska Native

- COFA

Compact of Free Association

- HJH&SW

Hawai‘i Journal of Health & Social Welfare

- NHPI

Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander

- NH

Native Hawaiian

- NHPI 3R

Native Hawaiian and Pacific Islander Response, Recovery, and Resilience Team

- OMB

Office of Management and Budget

Conflict of Interest

None of the authors identify a conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Tai DBG, Shah A, Doubeni CA, Sia IG, Wieland ML. The disproportionate impact of COVID-19 on racial and ethnic minorities in the United States. Clin Infect Dis. 2021;72(4):703–706. doi: 10.1093/CID/CIAA815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Palakiko DM, Daniels SA, Haitsuka K, et al. A Report on the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the health and social welfare of the Native Hawaiian population in Hawai’i. Hawaii J Health Soc Welf. 2021;80(9):62–70. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Buenconsejo-Lum LE, Qureshi K, Palafox NA, et al. A Report on the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the health and social welfare in the State of Hawai’i. Hawaii J Health Soc Welf. 2021;80(9):12–23. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.OMB Directive 15: Race and ethnic reporting standards for federal statistics and administrative reporting. Published 1977. Accessed January 9, 2023. https://wonder.cdc.gov/wonder/help/populations/bridged-race/directive15.html. [PubMed]

- 5.Prewitt K. What is your race?: The census and our flawed efforts to classify Americans. Published online June 9, 2013. [DOI]

- 6.Bailey ZD, Krieger N, Agénor M, Graves J, Linos N, Bassett MT. Structural racism and health inequities in the USA: evidence and interventions. Lancet. 2017;389(10077):1453–1463. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)30569-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Penman-Aguilar A, Talih M, Huang D, Moonesinghe R, Bouye K, Beckles G. Measurement of health disparities, health inequities, and social determinants of health to support the advancement of health equity HHS Public Access. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2016;22(1):33–42. doi: 10.1097/PHH.0000000000000373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Directive No 15 race and ethnic standards for federal statistics and administrative reporting. 1977. Accessed March 3, 2023. https://wonder.cdc.gov/wonder/help/populations/bridged-race/directive15.html. [PubMed]

- 9.Morey BN, Chang RC, Thomas KB, et al. No equity without data equity: data reporting gaps for Native Hawaiians and Pacific Islanders as structural racism. J Health Polit Policy Law. 2022;47(2):159–200. doi: 10.1215/03616878-9517177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Reviewing and revising standards for maintaining, collecting, and presenting federal data on race and ethnicity. Published 1997. Accessed January 9, 2023. https://www.whitehouse.gov/omb/briefing-room/2022/06/15/reviewing-and-revising-standards-for-maintaining-collecting-and-presenting-federal-data-on-race-and-ethnicity/

- 11.Fogleman C, Nakamoto J, Yang-Seon K. Demographic, social, economic, and housing characteristics for selected race groups in Hawaii. 2018. Accessed January 9, 2023. https://files.hawaii.gov/dbedt/economic/reports/SelectedRacesCharacteristics_HawaiiReport.pdf.

- 12.Lepule T, Kwoh S. A community of contrasts: Native Hawaiians and Pacific Islanders in the United States. 2014. Accessed January 9, 2023. https://archive.advancingjustice-la.org/what-we-do/policy-and-research/demographic-research/community-contrasts-native-hawaiians-and-pacific.

- 13.Look MA, Song S, Kaholokula JK. Assessment and priorities for health and well-being in Native Hawaiians and Pacific Islanders. Published November 2020. [DOI]

- 14.DBEDT Ranking of selected races for the State of Hawai’i 2010. Accessed January 15, 2023. https://files.hawaii.gov/dbedt/census/Census_2010/SF2/2010_race_ranking_from_SF2_final.pdf.

- 15.Rothman K, Greenland S, Lash T. Modern Epidemiology. 3rd Edition. Published online December 31, 2007. Accessed March 19, 2023. https://www.rti.org/publication/modern-epidemiology-3rd-edition.

- 16.McElfish PA, Purvis RS, Riklon S, Yamada S. Compact of Free Association migrants and health insurance policies: barriers and solutions to improve health equity. Inquiry. 2019;56 doi: 10.1177/0046958019894784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tcherkézoff S. A long and unfortunate voyage towards the “invention” of the Melanesia/Polynesia distinction 1595-1832. J Pac Hist. 2003;38(2):175–196. Accessed January 15, 2023. https://www.jstor.org/stable/25169638. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wendt A. Pacific maps and fiction(s) : a personal journey. 1995. pp. 13–44. Asian and Pacific inscriptions Victoria, Australia : Meridian, Published online 1995. Accessed March 19, 2023. https://natlib.govt.nz/records/31215703.

- 19.Jones N, Marks R, Ramirez R, Rios-Vargas M. Improved race and ethnicity measures reveal U.S. population is much more multiracial. 2021. Accessed January 15, 2023. https://www.census.gov/library/stories/2021/08/improved-race-ethnicity-measures-reveal-united-states-population-much-more-multiracial.html.

- 20.Kirch P V. 4. “Like shoals of fish.” in: the growth and collapse of Pacific Island societies. University of Hawaii Press; 2017. pp. 52–69. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Swanson DA. A new estimate of the Hawaiian population for 1778, the year of first European contact. Hulili: Multidisciplinary Research on Hawaiian Well-Being. 2019;11(2) [Google Scholar]

- 22.S.136 - 100th Congress (1987-1988): Native Hawaiian Health Care Act of 1988. Accessed January 15, 2023. https://www.congress.gov/bill/100th-congress/senate-bill/136.

- 23.Urban Indian Health Institute Best practices for American Indian and Alaska Native data collection. 2020. Accessed January 9, 2023. https://www.uihi.org/resources/best-practices-for-american-indian-and-alaska-native-data-collection/

- 24.Urban Indian Health Institute Data genocide of American Indians and Alaska Natives in COVID-19 Data. 2021. Accessed January 11, 2023. https://www.uihi.org/projects/data-genocide-of-american-indians-and-alaska-natives-in-covid-19-data/

- 25.Dunbar-Ortiz R. Indigenous peoples history of the United States. Beacon Press; 2014. Accessed January 11, 2023. http://www.beacon.org/An-Indigenous-Peoples-History-of-the-United-States-P1164.aspx. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Osorio EK. Struggle for Hawaiian cultural survival. Ballard Brief. Published online March 2021.

- 27.Cheng P, Johnson DA. Moving beyond the “model minority” myth to understand sleep health disparities in Asian American and Pacific Islander communities. J Clin Sleep Med. 2021;17(10):1969–1970. doi: 10.5664/JCSM.9500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Taparra K, Pellegrin K. Data aggregation hides Pacific Islander health disparities. Lancet. 2022;400(10345):2–3. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(22)01100-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kaholokula JK, Auyoung M, Chau M, Sambamoorthi U. Unified in our diversity to address health disparities among Asian Americans, Native Hawaiians, and Pacific Islanders. Health Equity. 2022;6(1):540–545. doi: 10.1089/HEQ.2022.0034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.A proclamation on Asian American, Native Hawaiian, and Pacific Islander heritage month, 2022 | The White House. Accessed January 9, 2023. https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/presidential-actions/2022/04/29/a-proclamation-on-asian-american-native-hawaiian-and-pacific-islander-heritage-month-2022/

- 31.State of New York Asian American and Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander (AA and NH/PI) data disaggregation A6896. 2021. Accessed January 9, 2023. https://www.nysenate.gov/legislation/bills/2021/A6896.

- 32.California. AHEAD Act. 2016. Accessed January 15, 2023. https://leginfo.legislature.ca.gov/faces/billNavClient.xhtml?bill_id=201520160AB1726.

- 33.Oregon Health Authority : Race, Ethnicity, Language, and Disability (REALD) Implementation : Office of Equity and Inclusion : State of Oregon. Accessed January 15, 2023. https://www.oregon.gov/oha/OEI/Pages/REALD.aspx.

- 34.Massachusetts. Identifying Asian American and Pacific Islander ethnic groups. 2018. Accessed January 15, 2023. https://malegislature.gov/Bills/190/H3361.

- 35. Rhode Island. All Students Count Act. H 5453. Published online 2017. Accessed January 15, 2023. http://webserver.rilin.state.ri.us/BillText/BillText17/HouseText17/H5453.pdf.

- 36.Kamaka ML, Watkins-Victorino L, Lee A, et al. Addressing Native Hawaiian and Pacific Islander data deficiencies through a community-based collaborative response to the COVID-19 pandemic. Hawaii J Health Soc Welf. 2021;80(10 Suppl 2):36–45. Accessed January 9, 2023. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34704067/ [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Quint JJ, van Dyke ME, Maeda H, et al. Disaggregating data to measure racial disparities in COVID-19 outcomes and guide community response — Hawaii, March 1, 2020–February 28, 2021. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2021;70(37):1267–1273. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm7037a1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sorensen CA, Wood B, Prince EW. Race & ethnicity data: developing a common language for public health surveillance in Hawaii. Calif J Health Promot. 2003;1(SI):91–104. doi: 10.32398/CJHP.V1ISI.561. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Iton A, Shrimali BP. Power, politics, and health: a new public health practice targeting the root causes of health equity. Matern Child Health J. 2016;20(8):1753–1758. doi: 10.1007/S10995-016-1980-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Iton A, Ross RK, Tamber PS. Building community power to dismantle policy-based structural inequity in population health. Health Aff (Millwood) 2022;41(12):1763–1771. doi: 10.1377/HLTHAFF.2022.00540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Worthington KJ, Eseta Matagi >CE, Helekunihiakahikina A, Kapulani A. COVID-19 vaccination experiences & perceptions among communities of Hawai‘i.; 2022. Accessed January 15, 2023. https://health.hawaii.gov/coronavirusdisease2019/files/2022/11/Full-Report-COVID-19-Vaccination-Experiences-Perceptions-among-Communities-of-Hawai%CA%BBi.pdf.

- 42.Hollander M, Wolfe DA, Chicken E. Nonparametric statistical methods. Wiley Online Library; pp. 1–819. Published online January 1, 2015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Morgan CJ. Use of proper statistical techniques for research studies with small samples. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2017;313:873–877. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00238.2017.-In. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]