Abstract

This study looked at measurements of lead (Pb) in a pilot population of environmentally exposed elderly residents of Shanghai, China and presented the first set of bone Pb data on an elderly Chinese population. We found that with environmental exposures in this population using K-shell x-ray fluorescence (KXRF) bone Pb measurements 40% of the individuals had bone Pb levels above the nominal detection limit with an average bone lead level of 4.9 ± 3.6 μg/g. This bone lead level is lower than comparable values from previous studies of community dwelling adults in US cities. This population had a slightly higher geometric mean blood Pb of 2.6 μg/dL than the adult US population. The main conclusion of this data is that in Shanghai there is environmental exposure to Pb, measured through blood and bone, which should be further investigated to assess the health impact of this exposure.

Keywords: Metals, environmental monitoring, bone lead, cumulative, lead, biomonitoring

1. Objective

Lead (Pb) exposure throughout the world has dropped significantly over the last few decades; however, some studies have demonstrated relationships between even low-level Pb exposure and chronic diseases such as cardiovascular disease and neurodegenerative diseases.(1, 2) Blood Pb is traditionally used to monitor exposure levels because of the relative ease of collection, but blood Pb only identifies recent exposures with its biological half-life of around one month in adults and even less in children.(3, 4) Bone Pb, with its half-life of years to decades,(3) serves as a better biomarker of cumulative, chronic exposures. For an environmentally exposed population, with chronic low-level exposure to Pb, bone Pb is a more relevant marker, especially for conditions that typically have long incubation periods like cardiovascular disease, neurodegenerative disease, and cancer.

Many studies exploring environmental exposure levels have focused on U.S. or European populations, but there is a significant lack of information on environmental Pb exposures in developing or newly industrialized countries. Environmental exposures in the past were commonplace with leaded gasoline serving as a primary source of exposure. Sources of exposure today would likely come from a combination of sources central to where the individual resides. These could be anything from preventable exposures such as Pb paint or dust to more broad exposures such as air pollution from coal power plants. Assessing the environmental exposure levels can be central to identifying at risk populations for health studies and determining global exposure levels to toxicants. This study looks at environmental Pb exposure levels in Shanghai, China using a pilot of elderly men with Pb measurements and presents the first set of bone Pb measurements on a Chinese population.

2. Approach

2.1. Study population

The study participants were not selected for occupational exposures, but rather community dwelling residents of Shanghai, China. The study was limited to those greater than 50 years old and who lived in Shanghai for greater than 10 years. The study received IRB approval from Purdue University and Xinhua Hospital. When recruited, a trained research assistant would present the subjects with the details of the study and the consent forms. Signed consent forms were received from each subject. The pilot study had 30 participants with average age 70.4 ± 9.1 years, minimum age 53 years and maximum age 82 years.

2.2. KXRF bone Pb measurement system

The KXRF bone Pb measurement system was used to measure tibia bone Pb as a metric of each individual’s cumulative Pb exposure. The setup was the same as used in previous studies.(4-7) The system uses four 16 mm diameter high-purified germanium (HpGe) detectors with 10 mm thickness, four feedback resistance pre-amplifiers, four digital signal processing systems, and a computer. A 135 mCi cadmium-109 (Cd-109) source with 0.8 mm copper filter is used to irradiate tibia bone to produce the Pb K x-rays. Before measurement, the subjects’ legs were cleaned using alcohol and ethylene diamine tetra-acetic acid (EDTA) cotton swabs to remove any Pb contamination. During the measurement, the subject would sit on a wooden chair with the right leg immobilized by using two Velcro straps to attach their leg to the leg of the chair at the ankle and just below the knee. The measurement site was mid-tibia with the source at a distance to maintain ~30% dead time during the measurement. Each measurement was taken for 30-minutes. Finally, the spectra were analyzed using an in-house peak-fitting program, which gave results and error for each of the four detectors.(5, 8, 9) This error and result was combined using inverse variance weighting.(10) XRF provides a point estimate of Pb concentration, which can be negative if an individual’s bone Pb is close to zero. It is important to include these negative values when treating the measurement as a continuous variable, as with their associated uncertainties they are still a point estimate of that individual’s bone Pb.

The whole body effective dose delivered to the subject from this system was estimated to be less than 0.3 μSv for this population.(11)

2.3. Blood Pb analysis

The blood of the subjects was collected in a Pb-free environment. We cleaned the subjects’ skin using alcohol swabs before sampling. The blood collection tubes along with the EDTA-K2 anticoagulants were measured to be Pb free before sampling. All the samples were frozen and kept at −80° C immediately after the collection. Blood Pb concentrations were measured and analyzed by a Graphite Furnace Atomic Absorption Spectrometer (GFAAS) (AA900Z, Perkin Elmer)(12). The sensitivity of our device was 0.01 μg/dL, and inter and intra assay variability from quality control standards was 5%. This has been used as a standard for blood Pb measurement in the past and the practical limit of detection is on the order of 1-2 μg/dL for routine use equipment.

3. Main Results

3.1. Blood Pb and bone Pb in the population

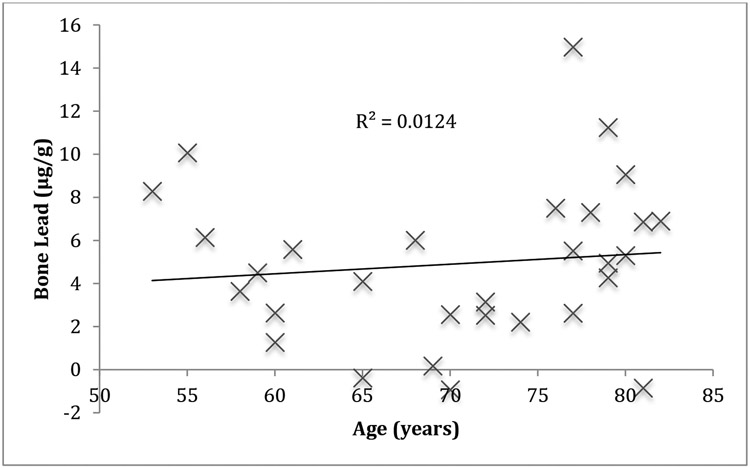

The blood Pb and bone Pb concentrations are listed in Table 1. The average uncertainty for the KXRF measurement was 2.5 ± 0.8 μg/g. The geometric mean of the blood Pb data was 2.6 μg/dL. There was no correlation between bone and blood Pb measurements or bone Pb and age (Figure 1) among the subjects.

Table 1.

KXRF bone Pb and blood Pb summary statistics.

| N | Median | Arithmetic Mean |

25th Percentile |

75th Percentile |

Minimum | Maximum | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bone Pb (μg/g) | 30 | 4.7 | 4.9 | 2.6 | 6.9 | −0.9 | 15.0 |

| Blood Pb (μg/dL) | 30 | 2.3 | 3.7 | 1.9 | 3.0 | 1.0 | 23.2 |

Figure 1.

Bone Pb versus age for the 30 men in our study.

3.5. Prevalence of concentrations above detection limits for KXRF bone Pb measurements

The prevalence of concentrations above the detection limit for the bone Pb measurements, and summary statistics for isolating the results above the detection limit are shown in Table 2. The detection limit for each measurement was taken as the uncertainty of the measurement itself. A result was included if the concentration results was greater than twice the associated uncertainty of the measurement.

Table 2.

Prevalence of KXRF bone Pb measurements above detection limit and summary statistics of measurements above detection limit.

| N | Prevalence | Average Bone Pb |

Standard Deviation |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| KXRF above DL | 12 | 40% | 7.9 | 3.0 |

4. Significance

This study looked at measurements of Pb in a pilot population of environmentally exposed elderly residents of Shanghai, China and presented the first set of bone Pb data on an elderly Chinese population.

This population had a slightly higher geometric mean blood Pb (2.6 μg/dL) than the adult US population, which had a blood Pb geometric mean of 1.2 μg/dL between 2009-2010.(13) The arithmetic mean of 3.7 μg/dL can be compared to levels in Germany in 2002-2003 at 2.2 μg/dL, France between 2006-2007 at 3.2 μg/dL, and Portugal in 2007 at 4.0 μg/dL. However, since most of these data are from many years ago, it is reasonable to assume the levels would be lower now. In a group of adult men age 69 ± 7 from the Boston area, the average tibia bone Pb was found to be 21.23 ± 13.29 μg/g between 1990 and 2005, which is much higher than the 4.9 ± 3.6 μg/g found in this study.(14) Although those levels would be expected to decline slightly over time.

The differences between the population measured here and those measure in the Boston area are stark. Likely part of this is due to the lower exposure in the Shanghai population. Although both countries banned leaded gasoline in the 1990’s, cities in China had less cars on the road than cities in the US before the ban went into effect. This could contribute to the significantly lower lead exposure in Shanghai than in Boston. In addition, the natural biologic half-life of Pb in the body, which could lower the bone lead concentrations in people from the Boston area over the almost 20 years between the studies. The Boston area adults showed a correlation between bone Pb and age, which was likely due to the ongoing exposure of leaded gasoline during the time of the measurements. The null association with age observed here may reflect the limited previous exposures in the population. Each person was exposed over the same time period, since exposure did not increase into the industrialization and wide spread use of cars, which would create an equal exposure for all individuals that were alive for the initial increase in environmental exposure. A similar null association with age was noted in a study of organochlorine pesticides in Finland, where all individuals over a certain age had the same level of exposure.(15)

A key limitation of this study was a lack of demographic information on the population measured. We are only able to identify that the subjects have lived in Shanghai for greater than 10 years and the age of subjects. Dietary information and lifestyle habits such as smoking status would be valuable to determine the impact these may have had on the generalizability of our findings in this study.

Overall, we found that with environmental exposures in this population using KXRF bone Pb measurements 40% of the individuals had bone Pb levels above the nominal detection limit, although even measurements below this can be used in health studies as a continuous variable.(16) The main conclusion of this data is that in Shanghai there is measureable environmental exposure to Pb, which should be further determined to assess the health impact of this exposure.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81373016, 30901205), National Basic Research Program of China (“973” Program,2012CB525001), Shanghai Science and Technology Committee [124119a1400], Purdue Ross Fellowship, and Purdue US-China visiting scholar network travel grant program.

6. References

- 1.Navas-Acien A, Schwartz BS, Rothenberg SJ, Hu H, Silbergeld EK, Guallar E. Bone lead levels and blood pressure endpoints. Epidemiology. 2008;19:8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Grashow R, Sparrow D, Hu H, Weisskopf MG. Cumulative lead exposure is associated with reduced olfactory recognition performance in elderly men: The Normative Aging Study. Neurotoxicology. 2015;49:158–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rabinowitz MB. Toxicokinetics of bone lead. Environ Health Perspect. 1991;91:4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Specht AJ, Lin Y, Weisskopf M, Yan C, Hu H, Xu J, et al. XRF-measured bone lead (Pb) as a biomarker for Pb exposure and toxicity among children diagnosed with Pb poisoning. Biomarkers. 2016:1–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nie H. Studies in bone lead: A new cadmium-109 XRF measurement system. Modeling bone lead metabolism. Interpreting low concentration data [Thesis (Ph D)]: McMaster University; (Canada: ), 2005.; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nie H, Chettle DR, Stronach IM, Arnold ML, Huang SB, McNeil FE, et al. A Study of MDL Improvements for the In Vivo Measurement of Lead in Bone. Nuclear Instruments and Methods in Physics Research B. 2004;213:4. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Specht AJ, Weisskopf M, Nie LH. Portable XRF technology to quantify Pb in bone in vivo. Journal of Biomarkers. 2014;2014:9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bevington P, Robinson D. Data reduction and error analysis for the physical sciences. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Somervaille LJ, Nilsson U, Chettle DR, Tell I, Scott MC, Schutz A, et al. In vivo measurements of bone lead-a comparison of two x-ray fluorescence techniques used at three different bone sites. Phys Med Biol. 1989;34(12). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Todd AC. Calculating bone-lead measurement variance. Environmental health perspectives. 2000;108(5):383–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nie H, Chettle D, Luo L, O'Meara J. Dosimetry study for a new in vivo X-ray fluorescence (XRF) bone lead measurement system. Nuclear Instruments and Methods in Physics Research B 2007. p. 225–30. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liu KL. [Review of atomic spectroscopy]. Guang Pu Xue Yu Guang Pu Fen Xi. 2005;25(1):95–103. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.CDC. Very High Blood Lead Levels Among Adults - United States 2002-2011. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly; 2013. p. 967–71. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ji JS, Power MC, Sparrow D, Spiro A 3rd, Hu H, Louis ED, et al. Lead exposure and tremor among older men: the VA normative aging study. Environ Health Perspect. 2015;123(5):445–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Weisskopf MG, Knekt P, O'Reilly EJ, Lyytinen J, Reunanen A, Laden F, et al. Persistent organochlorine pesticides in serum and risk of Parkinson disease. Neurology. 2010;74(13):1055–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kim R, Aro A, Rotnitzky A, Amarasiriwardena C, Hu H. K x-ray fluorescence measurements of bone lead concentration: the analysis of low-level data. Phys Med Biol. 1995;40(9):1475–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]