Abstract

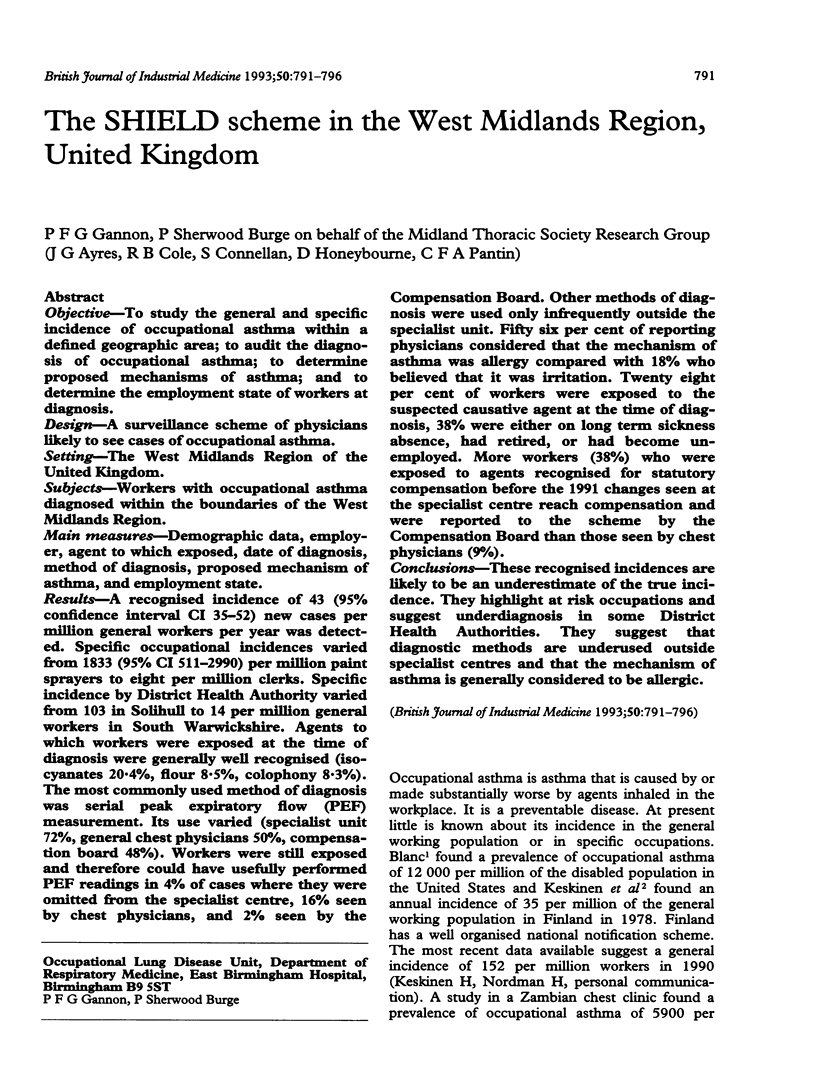

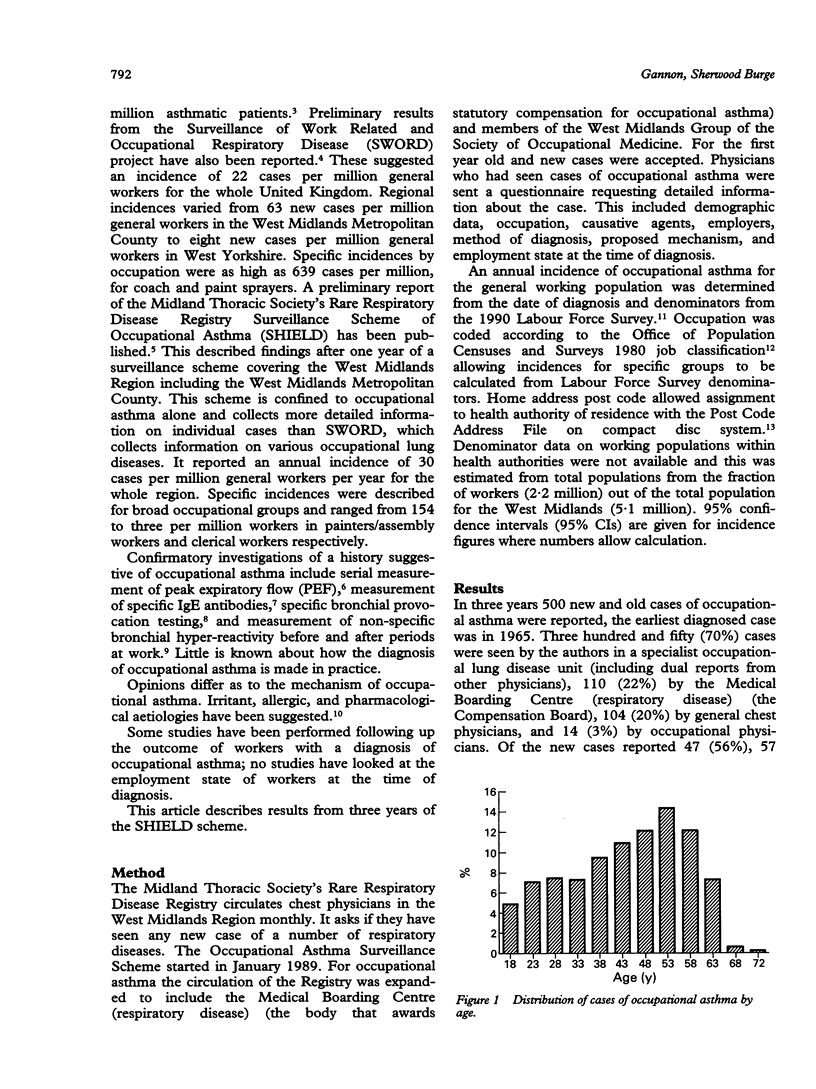

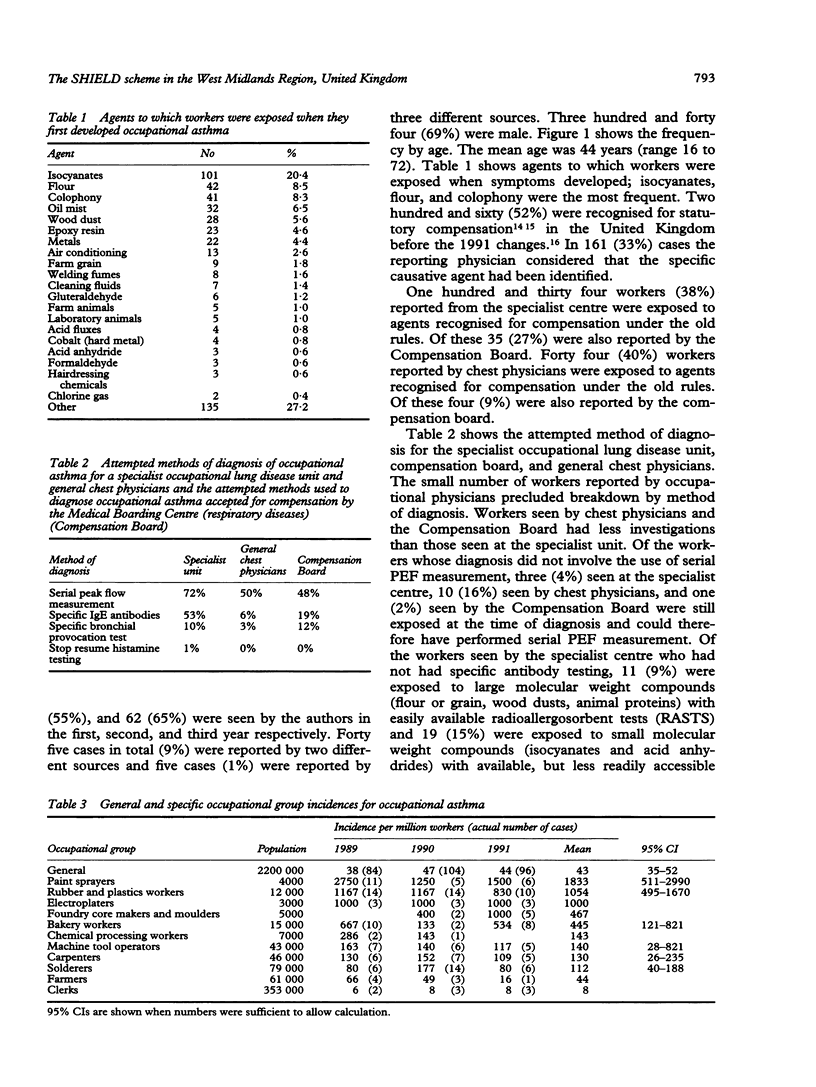

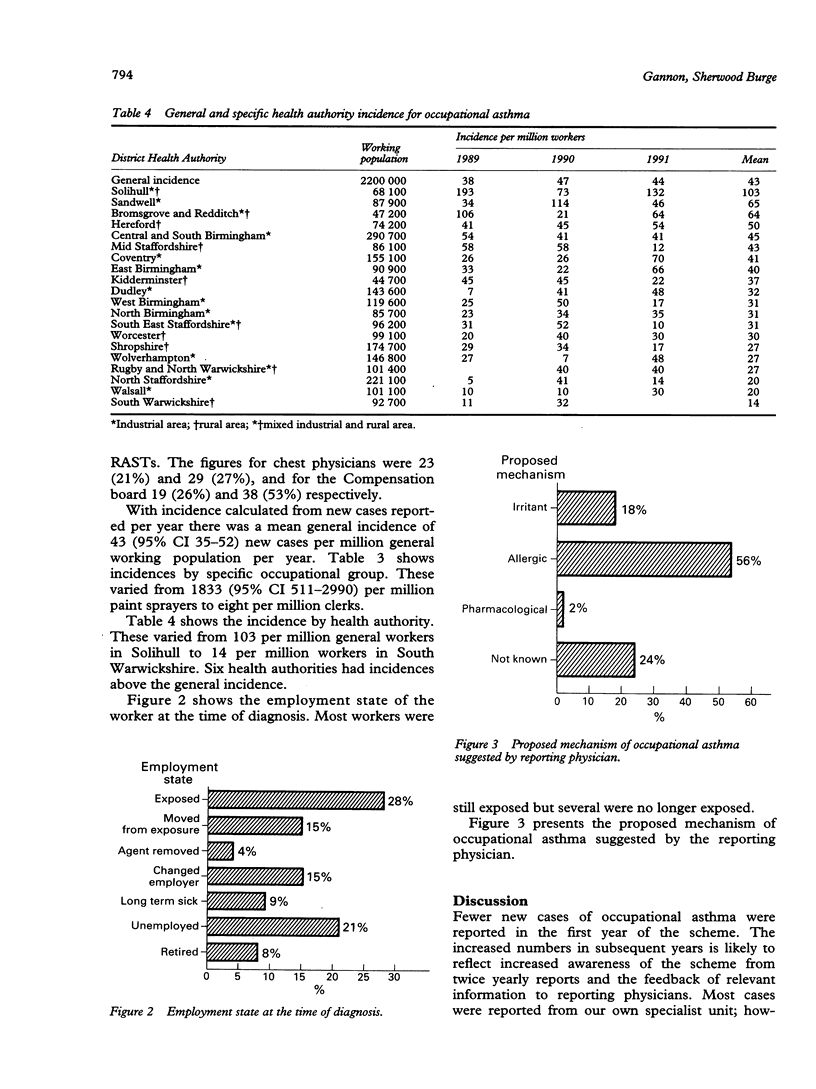

OBJECTIVE--To study the general and specific incidence of occupational asthma within a defined geographic area; to audit the diagnosis of occupational asthma; to determine proposed mechanisms of asthma; and to determine the employment state of workers at diagnosis. DESIGN--A surveillance scheme of physicians likely to see cases of occupational asthma. SETTING--The West Midlands Region of the United Kingdom. SUBJECTS--Workers with occupational asthma diagnosed within the boundaries of the West Midlands Region. MAIN MEASURES--Demographic data, employer, agent to which exposed, date of diagnosis, method of diagnosis, proposed mechanism of asthma, and employment state. RESULTS--A recognised incidence of 43 (95% confidence interval CI 35-52) new cases per million general workers per year was detected. Specific occupational incidences varied from 1833 (95% CI 511-2990) per million paint sprayers to eight per million clerks. Specific incidence by District Health Authority varied from 103 in Solihull to 14 per million general workers in South Warwickshire. Agents to which workers were exposed at the time of diagnosis were generally well recognised (isocyanates 20.4%, flour 8.5%, colophony 8.3%). The most commonly used method of diagnosis was serial peak expiratory flow (PEF) measurement. Its use varied (specialist unit 72%, general chest physicians 50%, compensation board 48%). Workers were still exposed and therefore could have usefully performed PEF readings in 4% of cases where they were omitted from the specialist centre, 16% seen by chest physicians, and 2% seen by the Compensation Board. Other methods of diagnosis were used only infrequently outside the specialist unit. Fifty six per cent of reporting physicians considered that the mechanism of asthma was allergy compared with 18% who believed that it was irritation. Twenty eight per cent of workers were exposed to the suspected causative agent at the time of diagnosis, 38% were either on long term sickness absence, had retired, or had become unemployed. More workers (38%) who were exposed to agents recognised for statutory compensation before the 1991 changes seen at the specialist centre reach compensation and were reported to the scheme by the Compensation Board than those seen by chest physicians (9%). CONCLUSIONS--These recognised incidences are likely to be an underestimate of the true incidence. They highlight at risk occupations and suggest underdiagnosis in some District Health Authorities. They suggest that diagnostic methods are underused outside specialist centres and that the mechanism of asthma is generally considered to be allergic.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Benson W. G. Exposure to glutaraldehyde. J Soc Occup Med. 1984 May;34(2):63–64. doi: 10.1093/occmed/34.3.63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanc P. Occupational asthma in a national disability survey. Chest. 1987 Oct;92(4):613–617. doi: 10.1378/chest.92.4.613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burge P. S. Single and serial measurements of lung function in the diagnosis of occupational asthma. Eur J Respir Dis Suppl. 1982;123:47–59. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan-Yeung M., Lam S. Occupational asthma. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1986 Apr;133(4):686–703. doi: 10.1164/arrd.1986.133.4.686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan-Yeung M., Lam S. Occupational asthma. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1986 Apr;133(4):686–703. doi: 10.1164/arrd.1986.133.4.686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies J. E. Occupational asthma caused by nickel salts. J Soc Occup Med. 1986 Spring;36(1):29–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gandevia B. Occupational asthma. I. Med J Aust. 1970 Aug 15;2(7):332–contd. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.1970.tb50018.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gannon P. F., Burge P. S. A preliminary report of a surveillance scheme of occupational asthma in the West Midlands. Br J Ind Med. 1991 Sep;48(9):579–582. doi: 10.1136/oem.48.9.579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gannon P. F., Weir D. C., Robertson A. S., Burge P. S. Health, employment, and financial outcomes in workers with occupational asthma. Br J Ind Med. 1993 Jun;50(6):491–496. doi: 10.1136/oem.50.6.491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hendy M. S., Beattie B. E., Burge P. S. Occupational asthma due to an emulsified oil mist. Br J Ind Med. 1985 Jan;42(1):51–54. doi: 10.1136/oem.42.1.51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keskinen H., Alanko K., Saarinen L. Occupational asthma in Finland. Clin Allergy. 1978 Nov;8(6):569–579. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2222.1978.tb01511.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meredith S. K., Taylor V. M., McDonald J. C. Occupational respiratory disease in the United Kingdom 1989: a report to the British Thoracic Society and the Society of Occupational Medicine by the SWORD project group. Br J Ind Med. 1991 May;48(5):292–298. doi: 10.1136/oem.48.5.292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pepys J., Hutchcroft B. J. Bronchial provocation tests in etiologic diagnosis and analysis of asthma. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1975 Dec;112(6):829–859. doi: 10.1164/arrd.1975.112.6.829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenberg N., Garnier R., Rousselin X., Mertz R., Gervais P. Clinical and socio-professional fate of isocyanate-induced asthma. Clin Allergy. 1987 Jan;17(1):55–61. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2222.1987.tb02319.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Syabbalo N. Occupational asthma in a developing country. Chest. 1991 Feb;99(2):528–528. doi: 10.1378/chest.99.2.528-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tse K. S., Chan H., Chan-Yeung M. Specific IgE antibodies in workers with occupational asthma due to western red cedar. Clin Allergy. 1982 May;12(3):249–258. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2222.1982.tb02525.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]