Abstract

Background

Dissecting cellulitis of the scalp (DCS) is a chronic inflammatory skin condition characterized by abscesses, nodules, fistulas, and scarring alopecia. Management of this oftentimes debilitating dermatosis can be challenging due to its recalcitrant nature. There is limited data regarding the efficacy of treatment options for DCS.

Objective

The aim of this study was to conduct a systematic review of the literature to explore the efficacy and safety of reported DCS treatments.

Methods

In October 2022, MEDLINE and EMBASE databases were searched for articles on treatments for DCS. Studies that contained outcome efficacy data for DCS treatments were included. Reviews, conference abstracts, meta-analyses, commentaries, non-relevant articles, and articles with no full-text available were excluded. Data extraction was performed by two independent reviewers.

Results

A total of 110 relevant articles with 417 patients were identified. A majority of studies (86.4%) were case reports or series. Treatment options included systemic antibiotics, oral retinoids, biologics, procedural treatments, combination agents, and topical treatments. Oral retinoids and photodynamic therapy were the most extensively studied medical and procedural interventions, respectively.

Conclusion

Overall, randomized controlled trials are needed to evaluate various treatment regimens for DCS and provide patients with a robust, evidence-based approach to therapy.

Keywords: Dissecting cellulitis of the scalp, Treatment, Therapy, Systematic review, Systemic, Medical, Procedural

Key Summary Points

| Although several medical and procedural treatments for dissecting cellulitis of the scalp (DCS) have been reported in the literature, the majority of data has been based on case reports or series. |

| In terms of systemic therapies, antibiotics and oral retinoids have the most data to support their use in DCS, but in recent years there has been an increasing number of reports to support use of various biologic therapies. |

| Procedural therapies for DCS including surgical excisions, photodynamic therapy, laser treatments, and radiation therapy overall had low rates of reported adverse events. |

Introduction

Dissecting cellulitis of the scalp (DCS) is a chronic, inflammatory skin disease that disproportionately affects African American males [1]. It is not a rare entity, with a reported prevalence of around 0.7% [2]. The condition is part of the follicular occlusion tetrad, which also consists of hidradenitis suppurativa (HS), acne conglobata, and pilonidal disease [1, 3]. DCS is characterized by abscesses and nodules that can eventually progress to form interconnected sinus tracts and cause scarring alopecia [4]. The disease is oftentimes refractory to treatment, making management challenging for clinicians. Although various treatment modalities have been reported, there is a lack of an updated review on their efficacy and safety. Herein, we aim to systematically evaluate existing literature on the efficacy and safety of medical and procedural treatments for DCS.

Methods

Search Strategy

This study was performed following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines and was preregistered on PROSPERO (CRD42022364109). This article is based on previously conducted studies and does not contain any new studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors. On 1 October 2022, two independent reviewers (E.M. and C.J.) searched MEDLINE and EMBASE databases from inception to search date with the following terms: (“dissecting cellulitis” OR “perifolliculitis capitis abscedens” OR “dissecting folliculitis” OR “Hoffman disease”).

A total of 773 articles were identified and filtered to remove non-English language and non-human studies. Duplicate articles were excluded. Titles and abstracts were screened for relevance. Full text review was then manually performed on the remaining 218 articles by the two independent reviewers (E.M. and C.J.). Studies that contained outcome efficacy data for DCS treatments were considered eligible for inclusion. Reviews, conference abstracts, meta-analyses, commentaries, non-relevant articles, and articles with no full-text available were excluded. Any discrepancies were discussed to consensus with a third reviewer (J.L.H.). Reference lists of articles that met inclusion criteria were screened for additional relevant articles and 5 additional articles were identified.

Data Extraction

Two reviewers (E.M. and C.J.) independently completed data extraction. Any discrepancies were discussed to consensus with a third reviewer (J.L.H.). For each article, the study design, country of study, patient characteristics, study intervention, efficacy outcomes, and safety outcomes were recorded. Articles were assessed for quality utilizing Cochrane risk of bias for prospective trials [5] and Newcastle–Ottawa Scale (NOS) for cohort studies [6].

Results

A total of 110 articles published between 1951 to 2022 fit the aforementioned search criteria and were included in this review (Fig. 1) [7]. These articles comprised 417 patients across 6 prospective trials, 8 retrospective cohort studies, 1 prospective cohort study, and 95 case reports/series. Study design, patient demographics, interventions, previous treatments, concomitant treatments, response, and adverse effects of the included studies are reported in Tables 1, 2, 3, and 4.

Fig. 1.

PRISMA flow diagram

Table 1.

Topical treatments for DCS

| Study characteristics | Intervention (treatment duration, when available) | Patient characteristics | Efficacy and adverse events |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gamissans 2022 [8], Spain, retrospective cohort* | Topical abx | n = 11 M |

Mean duration of tx: 5.09 ± 1.56 months 3 months: 27.3% (3/11) had a PR; and 72.7% (8/11) had NR; 6 months: 100% (3/3) had recurred (disappearance of improvement in those who initially had a PR) AE: pruritus or erythema (n = 4) |

| Karpouzis 2003 [9], Greece, case report | Isotretinoin gel (0.05%) (10 months) and clindamycin gel (1%) (2 months) |

n = 1 M, age 20 Comorbidities: acne PFT: oral abx, systemic steroids |

2 months, 10 months: hair growth, decreased inflammation; 1 year after finishing treatment at 10 months: no relapse |

| Navarro-Triviño 2020 [10], Spain, case report | Resorcinol 15% BID (3 months)—maintenance tx 3–4× per week |

n = 1 M, age 14 Comorbidities: overweight |

3 months: improvement of inflammatory nodules with follicular regrowth |

Abx, antibiotics; AE, adverse events; BID, two times a day; DCS, dissecting cellulitis of the scalp; M, male; NR, no response; PFT, previously failed treatments; PR, partial response; tx, treatment

*Poor quality as per Newcastle–Ottawa Scale (NOS). Cochrane risk of bias used for clinical trials. Newcastle–Ottawa scale (NOS) used for case–control/cross-sectional/cohort studies. Thresholds for converting the NOS rating to Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) standards (good, fair, and poor)—Good quality: 3 or 4 stars in selection domain AND 1 or 2 stars in comparability domain AND 2 or 3 stars in outcome/exposure domain. Fair quality: 2 stars in selection domain AND 1 or 2 stars in comparability domain AND 2 or 3 stars in outcome/exposure domain—Poor quality: 0 or 1 star in selection domain OR 0 stars in comparability domain OR 0 or 1 stars in outcome/exposure domain

Table 2.

Medical treatments for DCS

| Study characteristics | Intervention (treatment duration, when available) | Patient characteristics | Efficacy and adverse events |

|---|---|---|---|

| Systemic antibiotics | |||

| Abdennader 2011 [12], France, prospective trial^ | Doxycycline 100 mg/day for 3 months | n = 7 M, mean age 29.4 (19–35) | 3 month: 100% (7/7) had a PR |

| Badaoui 2016 [4], France, retrospective cohort* | Doxycycline, pristinamycin, rifampicin, or a combination of several antibiotics (n = 40) | n = 40 |

Mean FU of 11.2 months 100% (40/40) had moderate improvement with relapse after discontinuation |

| Segurado 2017 [25], Spain, retrospective cohort* |

Doxycycline 100 mg/d (n = 5), azithromycin 500 mg 3× per week (n = 3), rifampicin and clindamycin 300 mg BID (10 week) (n = 1) |

n = 9 |

Doxycycline: 80% (4/5) had a PR Azithromycin: 100% (3/3) had a PR Rifampicin and Clindamycin: 100% (1/1) had a PR |

| Gamissans 2022 [8], Spain, retrospective cohort* | Doxycycline 200 mg per day (3 months) (n = 6); Rifampicin and clindamycin 300 mg BID (3 months) (n = 4); dapsone (n = 4) | n = 14 M |

Mean duration of tx: 2.5 ± 0.83 months 3 months: 10% (1/10) had a CR and 90% (9/10) had a PR; 6 months: 90% (9/10) had recurred AE: abdominal intolerance (n = 4) Dapsone: mean duration of tx: 9.25 ± 5.06 months 3 months: 50% (2/4) had a CR and 50% (2/4) had a PR |

| Melo 2020 [13], Brazil; Retrospective cohort* | Lymecycline 300 mg per day (3 months) | n = 10 |

Day 45: 40% (4/10) improved (reduction in inflammatory activity) Day 90: 90% (9/10) improved |

| Jolliffe 1977 [57], USA, case report | Oxytetracycline 1 g per day |

n = 1 M, age 38 PFT: oral and topical abx, topical and systemic steroids |

1 month, 2 month: clearance of small temporal pustules, reduction in size of larger abscesses, hair regrowth in areas without keloid scarring |

| Brook 2006 [58], USA, case report | Clindamycin 600 mg q8h (6 weeks) |

n = 1 M, age 42 PFT: I and D, oral retinoids, oral abx; CT: topical retinoids |

12 months: significant improvement |

| Cárdenas 2011 [59], Columbia, case report | Rifampicin 300 mg q12h |

n = 1 M, age 22 PFT: oral and IV abx; CT: zinc, systemic steroids |

6 months: 70% improvement in lesions, complete improvement of suppuration |

| Koshelev 2014 [60], USA, case report | IV clindamycin and rifampin (6 days) |

n = 1 M, age 16 Comorbidities: HS, inflammatory acne, pyoderma gangrenosum; CT: I and D |

Day 6: improved |

| Varshney 2007 [61], UK, case report | Rifampin 300 mg BID and clindamycin 300 mg BID (10 weeks) |

n = 1 M, age 18 PFT: oral analgesics, oral abx, oral retinoids |

6 weeks, 10 weeks: less tender nodules, reduction in purulent discharge, most lesions flattened |

| Cormie 1962 [62], Scotland, case series | Terramycin 250 mg QID → BID (17 days) (n = 1) |

n = 1F, age 12 CT: collosol sulphur, sulphur in zinc paste (n = 1) |

4 months: good hair regrowth and only slight scarring |

| Gasner 1957 [63], USA, case report | Chloramphenicol 1000 mg per day in divided doses—500 mg per day after 2 weeks |

n = 1 M, age 34 PFT: surgical drainage and hot compresses; CT: hot boric acid compresses, liquid germicidal detergent wash |

2 weeks: marked improvement and no active lesions present |

| Greenblatt 2008 [64], UK, case report | Ciprofloxacin 250 mg BID (1 month) → 250 mg per day |

n = 1 M, age 28 PFT: oral abx, zinc, retinoids, systemic steroids |

1 month, > 5 months: hair regrowth on vertex, scalp nodules flattened, purulent discharge resolved, condition remained well controlled after decreasing dose to once daily |

| Onderdijk 2009 [65], Netherland, case report | Ciprofloxacin 500 mg BID (1 month) → 250 mg BID (3 weeks) |

n = 1 M, age 40 PFT: oral abx, retinoids |

1 month: complete resolution 3 months after stopping tx: condition in remission except for one small abscess |

| Ramesh 1990 [66], India, case report | Cephalexin 1 g per day in divided doses (2 months) (n = 1); IM gentamicin 5 mg/kg/day (4 weeks) → 3 mg/kg/day (2 weeks) (n = 1) |

n = 2 F, ages 10, 11 PFT: oral and IV abx; CT: aspiration (n = 2); topical abx, potassium permanganate solution scalp wash (n = 1) |

Patient 1 (cephalexin): 15 days: condition regressed, but some new nodules 6 months: some hair regrowth, no signs of disease Patient 2 (gentamicin): 15 days: condition improved 6 weeks: complete resolution |

| Mittal 1993 [67], India, case report | Trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole |

n = 1 F, age 40 Comorbidities: follicular occlusion triad PFT: oral abx |

20 days: reduced pus, pain, tenderness 5 days after stopping tx: relapsed |

| Salim 2003 [68], UK, case report | Trimethoprim 100 mg BID |

n = 1 M, age 36 Comorbidities: spondyloarthropathy, polyarthritis, acne (as a teenager) PFT: IV abx, oral retinoids, systemic steroids; CT: betadine wash, clindamycin solution |

18 months: developed fewer and less severe acute exacerbations of scalp lesions |

| Oral retinoids | |||

| Melo 2020 [15], Brazil, retrospective cohort* | Isotretinoin 0.25–0.5 mg/kg, cumulative dose of 120–150 mg/kg was reached |

n = 72 (71 M, 1F), median age 33.5 ± 9.0 PFT: oral abx, topical antiseptics, ketoconazole Comorbidities: acne (n = 21), pilonidal sinus (n = 3), cutis verticis gyrata (n = 2); cardiovascular disease, acne keloidalis nuchae, HTN, hepatitis, depression, neurological disease (n = 1) |

Range of 6–24 months for response time 90.3% (65/72) improved; cleared nodules and abscesses, hair regrowth 8.3% (6/72): NR |

| Badaoui 2016 [4], France, retrospective cohort* | Isotretinoin 0.5–0.8 mg/kg/day | n = 35 |

Mean FU of 6.7 months 94.3% (33/35) had complete remission but frequent relapse after discontinuation |

| Lee 2018 [16], Taiwan, retrospective cohort* | Isotretinoin 20–40 mg per day, 0.3–0.7 mg/kg | n = 16 |

Median time until initial response: 2 weeks CR (complete recovery of hair loss or global absence of bald area): 37.5% (6/16); PR (partial recovery with noticeable bald areas): 37.5% (6/16); NR (no improvement or enlarging hairless areas): 25% (4/16) |

| Segurado 2017 [25], Spain, retrospective cohort* | Isotretinoin 30 mg/d | n = 8 | PR: 87.5% (7/8) |

| Gamissans 2022 [8], Spain, retrospective cohort* | Isotretinoin | n = 4 M |

Mean duration of tx: 3.5 ± 1.8 months 3 months: 25% (1/4) had a CR, 50% (2/4) had a PR; 25% (1/4) had NR; 6 months: 33.3% (1/3) had recurred AE: dry eyes, itching (n = 3) |

| Scerri 1996 [69], UK, case series | Isotretinoin 1 mg/kg/day (4 months) → 0.75 mg/kg/day (total of 11 months) (n = 1); isotretinoin 1 mg/kg/day (9 months) (n = 2) |

n = 3 M, ages 23, 26, 24 Comorbidities: facial acne (n = 2), HS (n = 1) PFT: oral abx, zinc, Vaseline |

Patient 1: improved after 4 months (marked reduction in scalp swellings) and 11 months (disease inactive and marked regrowth of hair): still in remission 10 months after stopping tx Patient 2: complete response with regrowth of hair after 2.5 years Patient 3: improved after 3 months (scalp and beard showed progressive reduction of abscess formation) and 5 months (evidence of hair regrowth and repigmentation of white scarred areas on the scalp); 70% hair regrown after 2.5 years |

| Bjellerup 1990 [70], Sweden, case series | Isotretinoin 1 mg/kg/day for 6.5 months and then for 1.5 months (n = 1) or for 6 months (n = 1) |

n = 2 M (brothers), ages 20, 33 PFT: oral abx |

Patient 1: 2 months: no active disease 5 months after discontinuing tx at 6.5 months: mild relapse, isotretinoin restarted for 1.5 months 6 months after restarting isotretinoin: in remission Patient 2: 2 weeks: pustules cleared and nodules regressing 2 months: nodules disappeared and hair regrowth 7 months after completing tx at 6 months: complete remission |

| Benvenuto 1992 [71], Italy, case report | Isotretinoin 0.75 mg/kg/day |

n = 1 M, age 21 PFT: oral abx, I and D |

Day 30: no new nodules had developed, one persisting lesion needed further incision |

| El Sayed 2006 [72], Lebanon, case report | Isotretinoin 0.5 mg/kg/day (7 months) |

n = 1 F, age 38 PFT: topical abx and antifungals |

7 months: complete regression of symptoms, small area of scarring alopecia persisted 4 years: no recurrence |

| Healsmith 1992 [73], UK, case report | Isotretinoin 30 mg, 1 mg/kg, BID (16 weeks) |

n = 1 M, age 24 Comorbidities: acne vulgaris, diabetes PFT: oral abx, retinoids |

8 weeks: substantial improvement, decreased discharge and pain 16 weeks: discharge ceased and no pain 10 months after tx cessation: complete resolution |

| Khaled 2007 [74], Tunisia, case report | Isotretinoin 0.8 mg/kg/day (12 months) |

n = 1 M, age 25 Comorbidities: acne PFT: oral abx, systemic steroids, local tx; CT: surgical drainage |

4 weeks: significant reduction in abscess formation, nodules flattened, decreased pain 4, 6, 18 months: 95% of hair regrown, tx stopped after 12mo, no relapse in 6 months FU |

| Koca 2002 [75], Turkey, case report | Isotretinoin 0.75 mg/kg/day (6 months) → 0.5 mg/kg/day (3 months) |

n = 1 M, age 22 PFT: oral abx |

2 months: improved (no active disease of the scalp); marked improvement with resolution of abscesses, reduction of nodule size, and regrowth of hair 6 months: improvement continued with disappearance of nodules, regrowth of hair 3 months after stopping tx: remission maintained |

| Libow 1999 [76], USA, case report | Isotretinoin 90 mg/d (1 mg/kg/d) (9 months, tapered and discontinued for the last 3 months of the 9 months) |

n = 1 M, age 32 Comorbidities: cystic acne, HS, arthritis PFT: oral and topical abx, fluocinonide gel, oral retinoids 10 years previously |

1, 2 months: improvement 6 months after stopping tx: relapsed 6 months after restarting tx: complete improvement |

| Marquis 2017 [77], USA, case report | Isotretinoin 20 mg/d (0.27 mg/kg/d) |

n = 1 M, age 18 PFT: oral abx, topical clotrimazole, topical steroids |

Near-complete resolution after 4 months with no significant recurrence 7 months after discontinuing therapy |

| Melo 2021 [78], Brazil, case report | Isotretinoin 0.4 mg/kg/d |

n = 1 F, age 13 PFT: IV and oral abx; CT: oral abx, systemic steroids (for 14 days before isotretinoin) |

5 months: complete hair regrowth, no scarring alopecia, no inflammatory lesions |

| Mihić 2011 [79], Croatia, case report | Isotretinoin 80 mg/d (1 months) → 60 mg/d (2.5 months) |

n = 1 M PFT: emollients, oral abx, topical antimycotics, disinfectant spray, combined local topical compounds |

2 years: no disease relapse, normal hair growth AE: dryness, increased blood lipids |

| Mundi 2012 [80], USA, case report | Isotretinoin 1 mg/kg/d |

n = 1 M, age 32 PFT: topical and intralesional steroids, oral abx |

1 months: improvement in drainage |

| Omulecki 2000 [81], Poland, case report |

Isotretinoin 0.7 mg/kg/day (9 months in decreasing doses) Overall dose: ~ 120 mg/kg |

n = 1 M, age 19 PFT: oral abx, surgery |

5 weeks: improved 1 year after tx finished: in remission |

| Ortiz-Prieto 2017 [82], Spain, case report | Isotretinoin 0.7 mg/kg/day (6 months) |

n = 1 M, age 38 Comorbidities: AC |

2 months: adequate control of disease |

| Scavo 2002 [83], Italy, case report | Isotretinoin 0.75 mg/kg/day for 40d → 0.5 mg/kg/day (2 months), tx suspended gradually over final month |

n = 1 M, age 27 PFT: I and D, topical and oral abx, cortisone |

3 months: some lesions had disappeared while others had reduced markedly in size 1 year: almost all alopecic patches had disappeared 2y: remission maintained |

| Schewach-Millet 1986 [84], Israel, case report | Isotretinoin 1 mg/kg/day (16 weeks) → 0.5 mg/kg/d → 0.75 mg/kg/d |

n = 1 M, age 20 Comorbidities: acne PFT: oral abx, systemic steroids, I and D, ILK |

12 weeks, 16 weeks: considerable improvement (disappearance of some nodules, diminution in size of others, partial regrowth of hair); recurrence when dose was reduced |

| Stites 2001 [85], USA, case report | Isotretinoin 1 mg/kg/d |

n = 1 M, age 23 PFT: oral abx, antiseptic washes, I and D |

3 months: marked improvement with resolution of abscesses and sinus tracts, LTFU after this visit |

| Taylor 1987 [86], UK, case report | Isotretinoin 0.5 mg/kg/day (3 months) → 1 mg/kg/day (12 weeks) → 1 mg/kg/day (1 months) |

n = 1 M, age 21 Comorbidities: facial acne PFT: oral abx |

6 weeks: reduction in size of scalp cysts 12 weeks: complete healing of scalp lesions and hair regrowth 3 months after stopping tx: relapsed, but improved with another 12-week course of isotretinoin (1 mg/kg/d), relapsed again 3 months after stopping tx → third course of isotretinoin started, improved after 1 month |

| Tchernev 2011 [87], Bulgaria, case report | Isotretinoin 1 mg/kg (3.5 months) → 0.5 mg/kg due to side effects |

n = 1 M, age 30 PFT: oral abx |

3.5 months: significant improvement AE: epistaxis, xerosis in ocular and buccal mucosae |

| Prasad 2013 [17], Denmark, case report | Alitretinoin 10 mg/d (2 months) → 20 mg/d → reduced to 10 mg/d (maintenance dose) |

n = 1 M, age 15 Comorbidities: keratitis–ichthyosis–deafness syndrome, follicular occlusion triad PFT: acitretin, isotretinoin, systemic steroids, oral abx, PDT, antimycotics |

5 months: significant improvement AE: erosive skin lesions in auditory canals (improved after dose lowered to 10 mg/d) |

| Biologics | |||

| Gamissans 2022 [8], Spain, retrospective cohort* | ADA 80 mg q2w (n = 2), IFX 0.5 mg/kg/month (n = 1) | n = 3 M |

Mean duration of tx: 9.33 ± 3.77 months CR: 75% (2/3); PR: 25% (1/3) AE: infusion rxn that forced tx withdrawal (n = 1) |

| Sand 2015 [88], Denmark, retrospective cohort* | ADA 40 mg q2w |

n = 2 M PFT: oral retinoids, oral abx, ILK |

3 months: 50% (1/2) had total disease clearance 6 months: 50% (1/2) NR |

| Navarini 2010 [89], Switzerland, case series | ADA 80 mg for 1 wk → 40 mg q2w |

n = 3 M, Ages 30, 29, 27 Comorbidities: HS (n = 1) PFT: oral abx, oral retinoids |

8 weeks: clinical symptoms subsided 3 months: clinical activity and subjective symptoms significantly reduced After 4 months, ADA stopped (n = 1): relapse after 4 weeks of no tx, ADA restarted |

| Alsantali 2021 [90], Saudi Arabia, case report | ADA 80 mg on day 0 → 40 mg on day 7 → 40 mg q1w |

n = 1 M, age 38 PFT: oral and topical abx, oral retinoids |

1 month: excellent response 2 months: decreased swelling and areas of hair regrowth |

| Kurokawa 2021 [91], Japan, case report | ADA 160 mg on day 1 → 80 mg q2w |

n = 1 M, age 18 Comorbidities: HS, nodulocystic acne PFT: oral abx, CAM |

1 month: hemorrhagic ulceration improved, pain and itching subsided, insomnia resolved, alopecia improved |

| Martin-Garcia 2015 [92], Puerto Rico, case report | ADA 80 mg on day 0 → 40 mg on day 7 → 40 mg q2w for 2+ years |

n = 1 M, age 30 PFT: oral abx, oral retinoids, I and D, ILK |

1 month: significant decrease in pain, swelling 7 months, 2 years: complete clearance of lesions |

| Masnec 2018 [93], Croatia, case report | ADA 80 mg on day 0, 1, 14 → 40 mg on day 28, weekly thereafter |

n = 1 M, age 26 Comorbidities: HS, acne, dyslipidemia, obesity PFT: oral retinoids (improved DCS but worsened HS and acne) |

10 weeks: reduced secretions, pain, and inflammatory changes 15 months: tx well tolerated DLQI improved |

| Maxon 2020 [94], USA, case report | ADA 40 mg/week |

n = 1 M, age 37 Comorbidities: cystic acne PFT: ILK, excisions, oral retinoids, oral abx; CT: oral retinoids (started after 2 years on adalimumab) |

2 months: significant improvement 6 months: hair regrowth and reduction in bogginess and tenderness of the scalp 2 years: improvement with ADA plateaued, improved when acitretin was added |

| Minakawa 2021 [95], Japan, case report | ADA |

n = 1 M, age 30 Comorbidities: HS PFT: oral abx |

1, 18 months: reduced pain, no purulent secretions |

| Sukhatme 2008 [96], USA, case report | ADA 80 mg week 0, 40 mg week 1, then 40 mg q2w |

n = 1 M, age 39 PFT: oral abx, ILK, excision, oral retinoids |

1 month: pain and discharge stopped, scalp less boggy, smaller nodules, hair growth 2 months: two nodules remained, hair regrowth 5 months: lesions cleared, hair growing back normally |

| Takahashi 2019 [97], Japan, case report | ADA 80 mg on day 0 → 40 mg q2w for 3 months → 80 mg q2w |

n = 1 M, age 19 PFT: oral abx, zinc Comorbidities: HS |

1 month: pain significantly improved, purulent secretions ceased 3 months: hair regrowth |

| Badaoui 2016 [4], France, retrospective cohort* | IFX | n = 1 | Mean FU of 11.2 months: NR |

| Frechet 2021 [19], France, case series |

IFX 5 mg/kg at 0 week, 2 weeks, 6 weeks → q8w (n = 5), q6w (n = 3)*; or ADA 40 mg q2w (n = 1) *Increased to 7.5 mg/kg in n = 1 |

n = 9 (8 M, 1 F), mean age 33 ± 13 Comorbidities: AC, HS (n = 6); obesity (n = 4); pilonidal sinus, psoriasis, spondylitis (n = 1) PFT: oral abx, oral retinoids, MTX, disulone, thalidomide, systemic steroids, apremilast, canakinumab, tocilizumab; CT: oral retinoids, systemic steroids, oral abx (n = 3); MTX (n = 1) |

Mean tx duration: 17 ± 16 months (range 3–58 months) PGA: 88.9% (8/9) improved, mean decrease from 4 ± 1 to 2 ± 1; 11.1% (1/9) NR Inflammatory nodules: 9 ± 3 → 3 ± 4 Abscesses: 1.7 ± 1.06 → 0.2 ± 0.7 (78% reduction) in 87.5% (7/8) of patients DLQI: 27 ± 4 → 12 ± 8 Tx satisfaction index: 6.6 ± 1.6 out of 10 AE: retrobulbar optic neuritis caused one patient to drop out |

| Sanchez-Diaz 2021 [98], Spain, case series | IFX 5 mg/kg q8w (n = 1), ADA 80 mg q2w (n = 1) |

n = 2 M, ages 45, 48 Comorbidities: HS (n = 2), obesity (n = 2) PFT: oral abx, oral retinoids, ADA, PDT; CT: dapsone (4 weeks post-biologic for 20 weeks), IM ertapenem (11 weeks post-biologic for 6 weeks) |

24 weeks and 32 weeks: 100% (2/2): NRS pain, NRS pruritus, NRS suppuration, IHS4 improved; HiSCR achieved |

| Brandt 2008 [99], Brazil, case report | IFX 5 mg/kg q8w (1 year) |

n = 1 M, age 24 PFT: oral abx, oral retinoids |

16 weeks: hair beginning to regrow 1 year after tx discontinued: hair regrowth maintained, no relapse |

| Syed 2018 [100], USA, case report | IFX |

n = 1 M, age 31 Comorbidities: CD, peptic ulcer disease; CT: steroids |

Complete remission at unspecified time |

| Wollina 2012 [101], Germany, case report | IFX (5 mg/kg at 0 weeks, 2 weeks, 6 weeks) |

n = 1 M, age 30 Comorbidities: T2DM PFT: oral abx, retinoids, systemic steroids, surgery |

3 months: malodorous discharge stopped, inflammation reduced significantly, nodules flattened, pain decreased AE: psoriasiform spongiotic dermatitis |

| Awad 2022 [20], Australia, case report | Tildrakizumab 2 doses, 4 weeks apart |

n = 1 M, age 28 Comorbidities: HS, AC PFT: oral retinoids, oral abx, ILK |

8 weeks: reduction in pustules, decreased tenderness, and hair regrowth |

| Babalola 2022 [21], USA, case report | Risankizumab 150 mg at 0 weeks, 4 weeks, and then q12w |

n = 1 M, age 65 Comorbidities: NAFLD, HLD, HTN, CAD PFT: oral and topical abx, ILK, antiseptic wash, oral retinoids, steroids; CT: oral retinoid (for 3 months) |

7 months: excellent response |

| Muzumdar 2020 [22], USA, case report | Guselkumab 100 mg q4w for first 2 doses → q8w |

n = 1 M Comorbidities: HS, AC, folliculitis, pyoderma gangrenosum PFT: MTX, oral abx, ADA; CT: hydroxychloroquine, oral abx, systemic and topical steroids |

6 months: near complete resolution of scalp lesions, resolution of all symptoms |

| De Bedout 2021 [23], USA, case report | Secukinumab (eight injections of 150 mg over 3 months) |

n = 1 M, age 63 Comorbidities: acne vulgaris PFT: oral abx, oral retinoids, ADA, ILK; CT: oral abx |

1 month: drainage and pain completely stopped, nodules began regressing 1 year: in remission AE: eczematous reaction |

| Miscellaneous | |||

| Adrian 1980 [24], USA, case report | Multiple tapered courses of prednisone → 5 mg every other day after 1 year |

n = 1 F, age 22 PFT: oral and IV abx, antibacterial scrubs, warm compresses; CT: oral, IV, and topical abx |

48 h: drying of lesions, decreased swelling and pain 4 months: no evidence of active inflammation and sparse hair growth 1 year: full regrowth of scalp hair |

| Segurado 2017 [25], Spain, retrospective cohort* | Finasteride 1 mg/d | n = 3 | PR: 66.7% (2/3); NR: 33.3% (1/3) |

| Badaoui 2016 [4], France, retrospective cohort* | Zinc (n = 8); dapsone, corticosteroids, antifungals, or erythromycin (n = 10) | n = 18 | Mean FU of 11.2 months: 100% (18/18) had NR |

| Berne 1985 [27], Sweden, case report | Oral zinc sulfate 90 mg TID (12 weeks) → 45 mg TID (2.5 months) |

n = 1 M, age 24 Comorbidities: acne vulgaris PFT: steroid-abx combined lotion |

3 weeks: nodules disappeared and regrowth of hair 2 weeks after completion of tx: complete resolution 5 years: no relapse |

| Kobayashi 1999 [28], Japan, case report | Oral zinc sulphate 135 mg TID (4 weeks) → 250 mg/d (7 weeks) → 135 mg QD or BID |

n = 1 M, age 15 Comorbidities: cystic acne PFT: oral and topical abx; CT: oral abx |

4 weeks: nodules stopped growing and became flat 12 weeks: hair regrowth 1 week after stopping zinc tx: lesions recurred, zinc restarted with minocycline 8 weeks after restarting zinc: lesions diminished 1 year: well-controlled lesions |

| Kurokawa 2019 [29], Japan, case series | Oral Saireito (Japanese herb) 8.1 g/d |

n = 2 M, ages 17, 25 Comorbidities: AC, HS (n = 1) CT: oral abx (n = 1) |

3 months: 100% (2/2) improved Patient 1: nodules, cysts, and hypertrophic scar had improved; alopecia lesions had disappeared Patient 2: full growth with terminal hair on scalp; alopecia improved |

| Cormie 1962 [62], Scotland, case series | Perchloride of mercury lotion, chloramphenicol topical (1 month) → systemic chloramphenicol (10 days) → sulphur in zinc paste and IM penicillin (500,000 units) QD (10 days) | n = 1 F, age 14 |

Improved faster with systemic penicillin and topical sulphur 5 months after being seen, there were only very small scars with good hair growth |

Abx, antibiotics; AC, acne conglobata; ADA, adalimumab; AE, adverse events; BID, two times a day; CAM, complementary and alternative medicine; CD, Crohn’s disease; CR, complete response; CT, concomitant treatments; DCS, dissecting cellulitis of the scalp; DLQI, Dermatology Life Quality Index; FU, follow-up; HiSCR, Hidradenitis Suppurativa Clinical Response; HLD, hyperlipidemia; HS, Hidradenitis Suppurativa; HTN, hypertension; I and D, incision and drainage; IFX, infliximab; ILK, intralesional Kenalog; IM, intramuscular; IV, intravenous; LTFU, lost to follow-up; MTX, methotrexate; NR, no response; NRS, Numerical Rating Scale; PDT, photodynamic therapy; PFT, previously failed treatments; PR, partial response; q, every; QD, daily; QID, four times a day; T2DM, type 2 diabetes mellitus; TID, three times a day; tx, treatment

^High risk of bias as per the Cochrane risk of bias assessment used for clinical trials. *Poor quality as per Newcastle–Ottawa Scale (NOS). Cochrane risk of bias used for clinical trials. Newcastle–Ottawa Scale (NOS) used for case–control/cross-sectional/cohort studies. Thresholds for converting the NOS rating to Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) standards (good, fair, and poor)—Good quality: 3 or 4 stars in selection domain AND 1 or 2 stars in comparability domain AND 2 or 3 stars in outcome/exposure domain. Fair quality: 2 stars in selection domain AND 1 or 2 stars in comparability domain AND 2 or 3 stars in outcome/exposure domain. Poor quality: 0 or 1 star in selection domain OR 0 stars in comparability domain OR 0 or 1 stars in outcome/exposure domain

Table 3.

Procedural treatments for DCS

| Study characteristics | Intervention (treatment duration, when available) | Patient characteristics | Efficacy and adverse events |

|---|---|---|---|

| Surgical interventions | |||

| Badaoui 2016 [4], France, retrospective cohort* | Surgical excision or abscess drainage | n = 8 | Mean FU of 11.2 months: reduced pain but no effect on DCS progression |

| Gamissans 2022 [8], Spain, retrospective cohort* | Surgical tx | n = 3 M | 3 months: 100% (3/3) had a CR |

| Dellon 1982 [31], USA, case series | Excision → split thickness skin grafts |

n = 2 M, ages 27, 30 Comorbidities: AC, acne vulgaris, HS (n = 1) PFT: local wound care, abx |

5 years: 100% (2/2) improved with no recurrence AE: graft infection (n = 1) |

| Powers 2017 [102], USA, case series | Staged excisions q2–3 months |

n = 2 M, ages 37, 20 PFT: oral abx, ILK, ND:YAG laser, oral retinoids; CT: “medical therapy” (n = 2) |

2–3 months: remission of drainage with markedly improved QOL |

| Williams 1986 [103], USA, case series | Wide resection → split-thickness skin graft |

n = 4 M, ages 27, 32, 33, 45 Comorbidities: HS (n = 1) PFT: oral abx, I and D |

1–4 years: 100% (4/4) improved with no recurrence |

| Arneja 2007 [104], USA, case report | Wide local excision |

n = 1 M, age 15 PFT: antimicrobial shampoos, acetic acid wound dressings, topical retinoids, topical steroids, intralesional abx, oral abx, oral antifungals; CT: oral abx |

9 months: improved without recurrence |

| Bachynsky 1992 [105], Canada, case report | Wide local excision |

n = 1 M, age 32 PFT: oral retinoids, oral abx, ILK; CT: oral retinoids |

1 year: improved with no recurrence, complete hair regrowth |

| Baneu 2021 [30], Romania, case report | Excision and skin graft |

n = 1 M, age 65 Comorbidities: acne PFT: oral retinoids, penicillin, oral abx, daily povidone-iodine wet to dry local dressings; CT: postoperation—wet to dry dressings with povidone-iodine, alternate with polyhexanide |

18 months: complete remission AE: partial (20%) graft failure, seroma at skin graft donor site |

| Bellew 2003 [106], USA, case report | Excision → split thickness skin graft |

n = 1 M, age 25 PFT: systemic steroids, oral and IV abx, I and D, oral retinoids |

10 months: scalp completely healed |

| Housewright 2011 [107], USA, case report | Total scalp excision → split thickness skin graft |

n = 1 M, age 25 Comorbidities: HS PFT: systemic steroids, oral and topical abx, I and D, ILK, oral retinoids, etanercept |

8 weeks: relief of symptoms and patient satisfied with outcome |

| Maintz 2005 [108], Germany, case report | Radical debridement → mesh graft from thigh |

n = 1 M, age 31 Comorbidities: keratitis–ichthyosis–deafness syndrome, AC, HS PFT: oral retinoids |

Satisfactory result |

| Moschella 1967 [109], USA, case report | Excision → split thickness graft |

n = 1 M, age 20 PFT: topical and oral abx, I and D, hexachlorophene shampoo, epilation with superficial x-ray therapy |

8 months: complete remission of disease |

| Ramasastry 1987 [110], USA, case report | Debridements (numerous debridements of the scalp, involved periosteum, outer cortex of exposed bone) → split-thickness skin graft from thigh |

n = 1 M, age 25 Comorbidities: HS, acne CT: IV abx, enteral hyperalimentation, antidepressants, blood transfusions; oral abx and wound care for postoperative care |

3 months: complete eradication of disease and clearance of osteomyelitis of skull AE: half of grafts initially failed due to infection, areas regrafted a third and fourth time |

| Nijhawan 2019 [111], USA, case report | Full-thickness excisions → porcine xenograft (five staged excisions over 15 months) |

n = 1 M, age 29 PFT: oral and topical abx, oral retinoids, ILK, systemic steroids, TNF-alpha inhibitors, injections of sclerosing agents into sinus tracts; CT: antidepressants |

2 years: complete resolution of disease with no recurrence, significant improvement in QOL |

| Unal 2004 [112], Turkey, case report | Debridement → split-thickness skin graft to frontal region of debrided area |

n = 1 M, age 14 months PFT: oral abx; CT: I and D, oral abx |

3 months: abnormal hair regrowth at debrided area |

| Photodynamic therapy | |||

| Wu 2021 [33], China, prospective trial^ | Fire microneedling and 5% topical ALA-PDT (mean dose of 575.2 ± 41.2 J/cm [2]) q1–2 weeks, four tx total |

n = 42 M, median age 20 (range 18–37) Comorbidities: HS (n = 1) PFT: oral abx, oral retinoids, surgery, ILK, systemic steroids |

39% (16/41) improved after two tx; 75.6% (31/41) improved after three tx; 82.9% (34/41) improved after four tx; 2.4% (1/42) dropped out due to unknown reason; 24.4% (10/41) had recurred within 1 year AE: itching, burning, swelling, thin crusts (n = 42) |

| Feng 2019 [113], China, prospective trial^ | 10% ALA-PDT (3 tx every 10-15d, 20-30 min sessions) |

n = 8 M, ages 15–46 PFT: topical and oral abx, blocking therapy, surgery |

1, 3 months: 87.5% (7/8) improved, 12.5% (1/8) dropped out of the study AE: burning, scalp pain (n = 7) |

| Zhang 2016 [114], China, prospective trial^ | 5% ALA-PDT (3–7 tx sessions total) |

n = 7 M PFT: oral retinoids, CAM, oral and topical abx |

After 3 and 5–7 tx: 100% (7/7) improved AE: itching, pain, edematous erythema |

| Liu 2020 [115], China, prospective trial^ | 5% ALA–PDT (4 sessions, 1 per week) |

n = 5 M, ages 16, 21, 14, 30, 21 Comorbidities: acne vulgaris (n = 4); overweight (n = 2); keratosis pilaris, tinea capitis, AC (n = 1) PFT: oral retinoids, excision and drainage, CAM |

2 weeks: 100% (5/5) had a PR 1 months after last tx: 80% (4/5) had CR and 20% (1/5) had PR 9 months: 50% (2/4) maintained CR AE: pain, erythema, swelling |

| Feng 2021 [116], China, retrospective cohort* |

5% ALA-PDT (2–11 tx, median = 3 tx) |

n = 12 M, ages 15–53 Comorbidities: HS (n = 4); hyperthyroidism, T2DM, HTN, AC (n = 1) PFT: oral abx, oral retinoids, CAM; CT: continuation of previously failed systemic medications (n = 12) |

After last session: 83.3% (10/12) had improvement of at least 1 symptom; 90% (9/10) of those with improvement had recurrences (immediately or within 1–6 months) AE: scalp pain, crusting |

| Segurado 2017 [25], Spain, retrospective cohort* | PDT | n = 1 | NR |

| Cui 2020 [117], China, case series |

Photodynamic therapy (20% 5-ALA, 635 nm laser for 20 min) 1 tx (n = 7), 2 tx (n = 2) |

n = 9 M, mean age: 26.9 (range 17–38) Comorbidities: acne (n = 2) PFT: I and D, oral and IV abx; CT: surgery (n = 9), oral isotretinoin (n = 1) |

6 months: 88.9% (8/9) improved |

| He 2021 [35], China, case series | 20% ALA–PDT (three sessions q10d) with pretreatment by a fire needle |

n = 6 M, mean age 23.83 ± 5.6 (range 17–31) Comorbidities: overweight or obese (n = 5) PFT: topical and oral abx, surgery, systemic, topical and intralesional dexamethasone, Chinese traditional medicine |

After three sessions: CR: 50% (3/6); PR: 50% (3/6); 1 year: 16.7% (1/6) relapsed AE: itching, pain, erythema, and swelling (n = 1) |

| Su 2021 [34], China, case series | 5% 5 ALA–PDT q2 weeks (4 tx total) pretreated by fire needle intervention |

n = 3 M, Ages 43, 21,19 PFT: oral abx, surgery, drainage, PDT; CT: oral retinoids (n = 3) |

At FU of 6 weeks to 4 months: 100% (3/3) improved At FU of 1–2 years: no recurrence AE: local redness, swelling, pain, dryness (n = 3) |

| Liu 2013 [118], China, case report | 5% ALA–PDT q1 week (six sessions) |

n = 1 F, age 41 PFT: oral and topical abx, CAM, injectable thymus peptides, red light phototherapy |

7 weeks after completion of PDT: eruptions disappeared 5 months: no recurrence AE: burning during irradiation |

| Yan 2022 [119], China, case report | 10% 5 ALA–PDT q3–4 weeks, 3 tx |

n = 1 M, age 24 Comorbidities: follicular occlusion tetrad, pachyonychia congenita type II, ankylosing spondylitis CT: oral abx, sulfasalazine, oral retinoids, celecoxib |

5 months: reduced pustules and cysts |

| Zhan 2018 [120], China, case report | 10% 5-ALA–PDT q10–15d, 4 tx |

n = 1 M, age 23 PFT: steroids, intradermal injections, surgery |

After 2 tx: improvement of lesions with regression of abscesses and reduced inflammation After 4 tx: complete remission 3 months: hair regrowth |

| Laser treatments | |||

| Krasner 2006 [37], USA, prospective cohort* | Long-pulsed Nd:YAG laser (3–7 tx, monthly) |

n = 4 M, ages 25–40 Comorbidities: cystic acne, acne keloidalis nuchae, CD, HTN (n = 1) PFT: oral abx, oral retinoids, I and D, ILK; CT: topical or IL lidocaine (n = 4), oral abx (n = 2), oral retinoids (n = 1) |

1 year: 100% (4/4) improved Decreased drainage (4/4), decreased tenderness (4/4), partial hair regrowth (3/4) |

| Chui 1999 [38], USA, case series | Laser hair removal with EpiLaser (long-pulse non-Q switched ruby laser) q6 weeks: 3 tx (n = 1), 4 tx (n = 1), 5 tx (n = 1) |

n = 3 (2 M, 1 F), ages 23, 33, 35 Comorbidities: keratosis pilaris (n = 1), pseudofolliculitis barbae (n = 1) PFT: oral abx, oral retinoids, ILK, systemic steroids, hydroxychloroquine, topical steroids |

8 months (n = 2), 10 months (n = 1): 100% (3/3) improved AE: superficial crusting and erosion with persistent hypopigmentation (n = 1) |

| Xu 2022 [39], Japan, case series |

Er:YAG laser q1 month 2 tx (n = 1) and 4 tx (n = 1) |

n = 2 M, ages 20, 24 PFT: oral and topical abx, oral retinoids, fusidic acid cream; CT: topical abx after tx (n = 1) |

Patient 1: decreased lesion count and regression of nodules with partial hair regrowth after 4 tx (4 months) Patient 2: almost no inflammatory skin lesions and hair regrowth at the center of atrophic lesions after 2 tx (2 months) |

| Boyd 2002 [40], USA, case report | 800 nm pulsed-diode laser q4 week; 4 tx sessions |

n = 1 M, age 35 Comorbidities: diabetes PFT: oral retinoids, oral abx, colchicine, AZT, MTX, ketoconazole; CT: topical abx, prednicarbate ointment |

1 months: significant epilation 6 months: disease quiescent with no hair regrowth |

| Glass 1989 [41], USA, case report | Carbon dioxide laser focused mode at 31,830 W/cm [2] |

n = 1 M, age 36 PFT: oral abx, oral retinoids |

6 weeks: complete healing 4 months: no episodes of recurrence |

| Radiation treatment | |||

| Chinnaiyan 2005 [42], USA, prospective trial^ | External beam radiation therapy (electron beam radiation or a combination of electrons and photons) 5 d/week |

n = 4 M, ages 27–42 CT: analgesics |

4–13 years: 100% (4/4) improved with no relapse; all patients had complete epilation during or following radiation therapy AE: scalp irritation, erythema, xeroderma, pruritus |

| Paul 2016 [43], USA, case report | Superficial brachytherapy (10 Gray as 4 fractions) |

n = 1 M, age 46 Comorbidities: HS PFT: oral abx, oral antifungals, antiseptic wash, pentoxifylline, ILK, ADA, IFX |

4 weeks: improved 11 weeks: no recurrence |

| Intralesional steroid injections | |||

| Gamissans 2022 [8], Spain, retrospective cohort* | ILK | n = 1 M |

3, 6 months: partial recovery with noticeable bald areas AE: discrete skin atrophy |

| Moyer 1962 [45], USA, case series | Hydrocortisone acetate suspension 4–5 mg q4–5d (2 tx) | n = 1F, Age 30 |

After 2 tx: tenderness disappeared, decreased exudate 6 months of no tx: relapsed to pretreatment state |

| Intracavitary foam sclerotherapy | |||

| Aboul-Fettouh 2021 [47], USA, case series |

Intracavitary foam sclerotherapy: 1–3 mL injected per cavity (max of 10 mL) q4–8 week |

n = 3 M, ages 31, 33, 48 PFT: ILK, oral and topical abx, oral retinoids |

100% (3/3) improved Patient 1: cavities became firm and flattened; hair growth at previous alopecic sites Patient 2: cavities fibrosed and collapsed Patient 3: significant fibrosis and flattening along with hair regrowth around affected area |

| Compression bandage | |||

| Asemota 2016 [48], USA, case report | Applied manual pressure to nodule; dressing of gauze, an eye patch, and headband worn under cap |

n = 1 M, age 44 PFT: oral and topical abx, periodic aspiration, ILK |

1 month: lesion smaller, flatter, and less tender 4 months: growth of terminal hair in lesion |

Abx, antibiotics; AC, acne conglobate; ADA, adalimumab; AE, adverse events; ALA–PDT, aminolevulinic acid–photodynamic therapy; ALA–iPDT, 5-aminolevulinic acid-mediated interstitial photodynamic therapy; AZT, azathioprine; BID, two times a day; CAM, complementary and alternative medicine; CD, Crohn’s disease; CR, complete response; CT, concomitant treatments; DCS, dissecting cellulitis of the scalp; Er:YAG, Erbium-doped yttrium–aluminum–garnet; FU, follow-up; HiSCR, Hidradenitis Suppurativa Clinical Response; HLD, hyperlipidemia; HS, Hidradenitis Suppurativa; HTN, hypertension; I and D, incision and drainage; IFX, infliximab; IL, intralesional; ILK, intralesional Kenalog; IM, intramuscular; IV, intravenous; LTFU, lost to follow-up; MTX, methotrexate; ND:YAG, neodymium-doped yttrium–aluminum–garnet; NR, no response; NRS, Numerical Rating Scale; PDT, photodynamic therapy; PFT, previously failed treatments; PR, partial response; q, every; QD, daily; QID, four times a day; QOL, quality of life; sx, symptoms; T2DM, type 2 diabetes mellitus; TID, three times a day; TNF, tumor necrosis factor; tx, treatment; UC, ulcerative colitis

*Poor quality as per Newcastle–Ottawa Scale (NOS). Cochrane risk of bias used for clinical trials. Newcastle–Ottawa Scale (NOS) used for case–control/cross-sectional/cohort studies. Thresholds for converting the NOS rating to Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) standards (good, fair, and poor)—good quality: 3 or 4 stars in selection domain AND 1 or 2 stars in comparability domain AND 2 or 3 stars in outcome/exposure domain. Fair quality: 2 stars in selection domain AND 1 or 2 stars in comparability domain AND 2 or 3 stars in outcome/exposure domain—Poor quality: 0 or 1 star in selection domain OR 0 stars in comparability domain OR 0 or 1 stars in outcome/exposure domain

Table 4.

Combination treatments for DCS

| Study characteristics | Intervention (treatment duration, when available) | Patient characteristics | Efficacy and adverse events |

|---|---|---|---|

| Díaz-Pérez 2020 [49], Mexico, case series | ILK 10 mg/mL q4 week for 2 months and isotretinoin 20 mg/d |

n = 2 M (twins), ages 17 Comorbidities: obesity (n = 2) |

2 months: lesions improved and partial recovery of hair 6 months: full hair regrowth with no relapses |

| Garelli 2017 [121], Italy, case series | Clindamycin 300 mg BID for 30 days, 0.05% clobetasol propionate foam QD (n = 3) or BID (n = 1) |

n = 4 (2F, 2 M) ages 18, 26, 28, 33 Comorbidities: AC, UC (n = 1) |

After 1 month, then q3 weeks 75% (3/4): reduction in nodules and improved texture of nodules 25% (1/4): LTFU but had decrease in abscesses and suppuration |

| Georgala 2008 [122], Greece, case series | Oral rifampicin 300 mg BID for 4 months → oral isotretinoin 0.5 mg/kg/day for 4 months (n = 2) or 3 months (n = 2) |

n = 4 M, ages 24, 31, 29, 34 PFT: oral and topical abx, oral antifungals |

4 months to 1 year: 50% (2/4): no active lesions observed 50% (2/4): disease progression halted |

| Ankad 2022 [123], India, case report |

Daily: acitretin 10 mg, rifampicin 300 mg, minocycline 50 mg After 4 weeks: only acitretin continued for another 8 weeks |

n = 1 M, age 8 |

4 weeks: reduction in pustules and hair regrowth 6 months: no recurrence |

| Bolz 2008 [124], Germany, case report | Isotretinoin 40 mg BID, dapsone 50 mg BID |

n = 1 M, age 19 PFT: oral, IV, and topical abx, I and D, isotretinoin 80 mg/d for 4 weeks |

4 weeks: marked improvement 10 months: improvement sustained; isotretinoin tapered to 20 mg/d, dapsone to 50 mg/d 12 months: remained free of symptoms; only dapsone 50 mg/d continued |

| Donovan 2015 [125], Canada, case report | Isotretinoin 1 mg/kg/d, prednisone started at 40 mg then reduced by 5 mg/week for 8 weeks; cephalexin |

n = 1 M, age 25 Comorbidities: multiple sclerosis CT: interferon beta-1a for multiple sclerosis |

Improved at unspecified time |

| Goldsmith 1993 [126], UK, case report |

Oral flucloxacillin (250 mg 4× per day for 2 weeks) After 2 weeks added: oral minocycline 100 mg BID, oral cyproterone acetate and oral ethinyl estradiol |

n = 1 F, age 18 PFT: surgical drainage, abx, oral retinoids, antimalarials Comorbidities: follicular occlusion triad |

3 months: lesions on scalp and face healed 6 months: no active disease |

| Jacobs 2011 [127], Germany, case report | Acitretin 10 mg/d, prednisolone 30 mg/d → 5 mg/d; zinc aspartate 100 mg/d; topical glucocorticoids and tacrolimus 0.1% alternated |

n = 1 F, age 86 PFT: topical steroids, oral abx |

11 days: improved, systemic corticosteroids tapered and topical corticosteroids stopped 6 months: condition stable |

| Ljubojevic 2005 [128], Croatia, case report | Cloxacillin 500 mg QID for 10d, 2% salicyl resorcin solution BID; isotretinoin 30 mg/d → 20 mg/d (over 3 weeks) → 10 mg/d |

n = 1 M, age 29 PFT: oral abx, combined topical steroid and abx lotion |

1 month: decrease in edema, fluctuance, drainage 10 months: no active disease 3 months after stopping tx: mild relapse, new course of isotretinoin started for 16 weeks 2 years after restarting isotretinoin: complete remission, only patchy alopecia present AE: hyperlipidemia |

| Shaffer 1992 [50], Canada, case report | IL triamcinolone acetonide 40 mg/mL; isotretinoin 0.85 mg/kg/d → increased over 4 weeks to 1.3 mg/kg/d → increased to 1.5 mg/kg/day by 3 months |

n = 1 M, age 25 Comorbidities: acne PFT: oral and topical abx, I and D, 0.025% vitamin A acid gel, topical steroids; CT: scalp abscesses excised after IL triamcinolone q2 week |

1 month: decrease in edema, fluctuance, and purulent drainage 4 months: scalp improved significantly, few abscesses remained needing I and D 5 months: scalp hair regrew 2 years after stopping tx: disease free AE: xerosis, mild transient increase in serum triglycerides |

Abx, antibiotics; AC, acne conglobate; AE, adverse events; BID, two times a day; cm, centimeters; CT, concomitant treatments; D, day; DCS, dissecting cellulitis of the scalp; F, female; FU, follow-up; g, grams; h, hours; HS, Hidradenitis Suppurativa; I and D, incision and drainage; IL, intralesional; ILK, intralesional Kenalog; IV, intravenous; LTFU, lost to follow-up; PFT, previously failed treatments; q, every; QD, daily; QID, four times a day; tx, treatment; UC, ulcerative colitis

^High risk of bias as per the Cochrane risk of bias assessment used for clinical trials. *Poor quality as per Newcastle–Ottawa Scale (NOS). Cochrane risk of bias used for clinical trials. Newcastle–Ottawa Scale (NOS) used for case–control/cross-sectional/cohort studies. Thresholds for converting the NOS rating to Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) standards (good, fair, and poor)— Good quality: 3 or 4 stars in selection domain AND 1 or 2 stars in comparability domain AND 2 or 3 stars in outcome/exposure domain. Fair quality: 2 stars in selection domain AND 1 or 2 stars in comparability domain AND 2 or 3 stars in outcome/exposure domain. Poor quality: 0 or 1 star in selection domain OR 0 stars in comparability domain OR 0 or 1 stars in outcome/exposure domain

Data on patients’ sexes were available for 375 patients and 94.9% (356/375) of patients were male. Age at the time of study ranged from 14 months to 86 years. Top reported comorbidities included acne (17.5%, 73/417) and hidradenitis suppurativa (8.6%, 36/417). Study locations included the USA (n = 35), China (n = 11), UK (n = 7), Japan (n = 6), Spain (n = 5), Germany and Brazil (n = 4 each), Italy, India, Canada, Croatia and France (n = 3 each), Greece, Denmark, Turkey and Sweden (n = 2 each), Colombia, the Netherlands, Lebanon, Tunisia, Taiwan, Poland, Israel, Bulgaria, Saudi Arabia, Australia, Puerto Rico, Switzerland, Romania, Scotland and Mexico (n = 1 each). In terms of study quality, all cohort studies were of poor quality and all prospective trials carried a high risk of bias.

There were 17 articles on systemic antibiotic treatments, 25 on oral retinoids, 21 describing biologic treatments, and 39 on procedural treatments. Other interventions studied include combination (n = 10), topical (n = 3), and a few miscellaneous (n = 7) treatments. Response to treatment was defined as partial or complete improvement in a patient’s condition as determined by each individual study. Measures for improvement used by studies were variable and included reduction in number and size of inflammatory nodules and abscesses; flattening of sinus tracts; improvement in pain, drainage, itch, and swelling; and hair regrowth. The outcome measure for each individual study has been described in Tables 1–4, where available. Overall response rate to a specific DCS intervention was calculated on the basis of aggregate response across studies.

Topical Treatments

Limited data were available for topical DCS treatments (Table 1). Gamissans et al.’s retrospective cohort study reported a partial response in 3 out of 11 patients treated with topical antibiotics. Pruritus or erythema was reported to occur in 4 out of 11 treated patients [8]. One case report noted improvement with a isotretinoin gel and clindamycin gel combination treatment in a 20-year-old male [9]. Topical resorcinol at 15% strength applied twice daily induced clinical improvement in a 14-year-old male [10].

Systemic Antibiotics

The antibacterial and antiinflammatory effects of oral antibiotics may play a role in mitigating DCS symptoms (Table 2) [11]. The overall response rate to systemic antibiotic treatments across studies was 97.8% (91/93). Antibiotics that were utilized include doxycycline (n = 18), dapsone (n = 4), azithromycin (n = 3), ciprofloxacin and trimethoprim (n = 2 each), and lymecycline, oxytetracycline, rifampicin, clindamycin, terramycin, chloramphenicol, cephalexin and gentamicin (n = 1 each). Antibiotic combinations studied included clindamycin and rifampin (n = 7). Time to response to oral antibiotics, when reported, ranged from 6 days to 18 months. Seven patients who received doxycycline in a prospective trial had a good response to the intervention after 3 months, but none were cured of their disease [12]. A retrospective cohort study by Badaoui et al. described moderate improvement in 40 patients who received various systemic antibiotics; however, patients relapsed frequently after discontinuation of treatment [4]. Gamissans et al.’s retrospective cohort study described 14 patients, 6 of whom received doxycycline for 3 months, 4 patients on a regimen of rifampin and clindamycin for 3 months, and 4 patients on dapsone. Overall, complete recovery of alopecia was seen in 3 patients, and 11 exhibited a partial response. Four of the patients had gastrointestinal (GI) distress [8]. Melo et al.’s retrospective cohort study demonstrated improvement in nine out of ten patients on lymecycline 300 mg (mg) per day for 3 months [13].

Oral Retinoids

Retinoids have antiinflammatory and antiproliferative effects, which may normalize the epithelium and decrease follicular occlusion [14]. Isotretinoin has been the most studied oral retinoid for DCS with an overall response rate of 91% (142/156); 25.4% (29/114) of patients treated with isotretinoin had concomitant acne. Isotretinoin dosing ranged from 0.3–1 mg/kg/day and reported duration of treatment ranged from 1–12 months. Isotretinoin led to a significant reduction of inflammatory activity in 90.3% of 72 adult patients in a large retrospective multicenter study [15]. Badaoui et al.’s retrospective cohort study described improvement with isotretinoin in 33 of 35 patients; however, patients relapsed frequently after discontinuation [4]. Lee et al.’s retrospective study also reported complete or partial response in 12 out of 16 patients who received isotretinoin for their DCS. Although there was no significant correlation between the isotretinoin dose and degree of response, the two patients who had recurrences had received lower cumulative doses [16]. Another retrospective cohort study described a partial or complete response in three out of four patients who received isotretinoin. One out of three patients with a reported response had a recurrence [8]. Adverse effects reported with isotretinoin across all studies included xerosis, dry eyes, erosive skin lesions, pruritus, epistaxis, and hyperlipidemia. There was one report of alitretinoin use in the literature. Significant improvement was noted in a 15-year-old male who received a dose of 10–20 mg/day for 5 months; however, erosive skin lesions developed when the dose was increased to 20 mg/day [17]. Finally, a patient who was prescribed acitretin 30 mg/day was lost to follow-up [4].

Biologics

It has been posited that biologics may downregulate key inflammatory markers such as tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-alpha and interleukin (IL)-12/23, which are associated with follicular occlusion disorders such as DCS [18, 19]. Biologics studied for treatment of DCS include adalimumab, infliximab, secukinumab, guselkumab, risankizumab, and tildrakizumab. Most (70%, 14/20) studies on biologics for DCS have been published in the last 5 years. HS was reported as a comorbidity in 41.2% (14/34) of patients. The majority of patients had previously failed treatment with oral antibiotics (82.4%, 28/34) and oral retinoids (58.8%, 20/34).

Adalimumab (ADA) was the most studied, and overall 94.1% (16/17) of patients exhibited a response to the immunomodulator. Most (83.3%, 10/12) of the studies were case reports/series. Dosing of ADA ranged from 40–80 mg every 1–2 weeks. A response rate of 85.7% (12/14) was observed for infliximab (IFX) treatment across two retrospective cohort studies and five case reports/series. The IFX dosing interval was 5 mg/kg every 4–8 weeks. Adverse events reported with IFX treatment include an infusion reaction, psoriasiform spongiotic dermatitis, and retrobulbar optic neuritis.

IL-23 inhibitors have a few reported cases in the literature for DCS. A reduction in pustules, decreased tenderness, and hair regrowth was observed in a 28-year-old male after receiving two doses of tildrakizumab [20]. Babalola et al. described improvement after 7 months in a 65-year-old male’s DCS symptoms with risankizumab dosed at 150 mg every 12 weeks [21]. Finally, guselkumab treatment at a maintenance dose of 100 mg every 8 weeks for 6 months was effective in inducing near complete resolution of symptoms in a case report of a male patient who had failed treatment with ADA [22].

Treatment with secukinumab, an IL-17 inhibitor, was described in a 63-year-old male patient. He had complete remission for 1 year after taking secukinumab 150 mg weekly for 6 weeks (patient mistakenly took an extra loading dose) then monthly for 2 months. Although the patient developed an eczematous reaction as an adverse event, this was successfully treated with topical therapy [23].

Miscellaneous Systemic Therapies

Long-term prednisone therapy was reported in one patient. Signs of active inflammation subsided within 4 months and full regrowth of scalp hair was observed after 1 year of treatment. The patient was maintained on 5 mg of prednisone every other day after 1 year of multiple tapered courses of treatment [24]. Finasteride 1 mg/day was also shown to be effective in two out of three treated patients [25].

Zinc is known to have antiinflammatory and antioxidant properties via inhibition of inflammatory mediators such as TNF-alpha [26]. A retrospective cohort study which included eight patients receiving zinc found that none of them exhibited a response [4]. The use of zinc for DCS was also described in two case reports, both of which reported positive results [27, 28]. One of the patients was in remission for 5 years and the other had well-controlled lesions for 1 year. Oral saireito, a Japanese herb, improved DCS disease course in two patients [29].

Procedural Treatments

Surgical Interventions

Surgical excisions with and without skin grafts were reported to induce improvement in 21 patients across one retrospective cohort study and 13 case reports/series; long-term remission was reported across multiple studies. Many of the patients undergoing surgery had failed medical management with oral antibiotics and/or oral retinoids (Table 3). Split-thickness skin grafts were most commonly used for reconstruction. Complications were uncommon in the literature. Baneu et al. reported a seroma at the skin graft donor site [30], and Dellon et al.’s case series described a skin graft infection in one patient [31].

Photodynamic Therapy

Photodynamic therapy (PDT) inhibits follicular secretions, mitigates hyperkeratinization, reduces inflammation, and ablates tissues. PDT may also destroy persistent microbial biofilms, which can contribute to DCS symptoms [32]. The overall response rate to PDT with aminolaevulinic acid (ALA) across three prospective trials, one retrospective cohort study, and six case reports/series was 88.3% (83/94).

Wu et al.’s 2021 prospective trial demonstrated a novel technique in which a heated microneedle was used to puncture lesions. Thereafter, 5% ALA was applied followed by red-light PDT treatment. After four sessions, a total of 34 out of 42 patients reported improvement. Ten of the patients had relapsed within 1 year. Itching, burning, swelling, and thin crusts were noted as transient side effects [33]. Su et al. and He et al. described similar procedures in 3 and 6 patients, respectively [34, 35]. All patients had good results, but notably, Su et al. used isotretinoin as a concomitant treatment in all patients [34]. Adverse events reported with PDT include erythema, pain, itching, and swelling.

Laser Treatments

Lasers may selectively or non-selectively destroy hair follicles, thereby counteracting the progression of events that lead to follicular occlusion and rupture [36].

Long-pulsed neodymium-doped yttrium–aluminum–garnet (Nd:YAG) laser treatment sessions were effective in reducing drainage and tenderness in four males aged 25–40. A total of three to seven treatment sessions were conducted [37]. A long-pulsed ruby laser was used to perform laser hair removal in two males and one female. All patients had beneficial results, although one reported crusting and erosion with persistent hypopigmentation [38]. A case series reported improvement in two males after treatment with the erbium-doped (Er):YAG laser. One of the patients had good results after two treatment sessions and the other improved after 4 sessions [39].

Improvement was observed in a single case report of a 35-year-old male who received four treatments with 800-nm pulsed diode laser. Significant epilation was reported after 1 month and the disease was quiescent at the 6 month follow-up [40]. In Glass et al.’s 1989 case report, excision with a carbon dioxide laser led to complete clearance of disease after 6 weeks. No recurrence was observed after 4 months [41].

Radiation Treatment

A total of four patients received radiation therapy consisting of electron beam radiation or combination electron and photon radiation; all patients had decreased drainage and nodule sizes after the culmination of treatment sessions. Mild scalp irritation, erythema, xeroderma, and pruritus were noted [42]. A 2016 study by Paul et al. reported substantial improvement in a 46-year-old male with brachytherapy to the occiput [43]. Of note, x-ray irradiation, no longer used in the present day for cutaneous conditions given its side effect profile, was performed in nine patients across three studies conducted in the 1950s and 1960s and resulted in disease improvement in all patients [44–46].

Intralesional Steroid Injections

Gamissans et al.’s retrospective cohort study included one patient who received intralesional steroid injections that resulted in partial recovery of disease, although discrete skin atrophy was noted as a side effect [8]. A 30-year-old female experienced improvement after two treatments with hydrocortisone injections into abscesses every 4–5 days. However, the patient relapsed after 6 months of no treatments [45].

Intracavitary Foam Sclerotherapy

Fibrosis and flattening of DCS lesions were observed in three patients who underwent intracavitary foam sclerotherapy. No complications were noted throughout the course of treatment [47].

Compression Bandage

A 44-year-old male self-devised a compression dressing consisting of gauze, an eye patch, and a headband worn under a cap. The affected lesion became smaller and flatter after 1 month and demonstrated terminal hair growth after 4 months [48].

Combination Therapies

A variety of combination treatment approaches have been reported for DCS (Table 4). All 17 patients across ten case reports/series improved with combination therapies for DCS. A total of 14 patients on combined medical therapies such as oral retinoids and oral antibiotics improved, with the exception of one who was lost to follow-up. Similarly, three studies described combined medical and procedural treatments in four patients. Of the three studies, two examined intralesional steroid injection use combined with various doses of isotretinoin [49, 50]. All three patients improved.

Discussion

Our systematic review of DCS management strategies highlights the paucity of evidence-based data for DCS. The majority of studies in the literature describing DCS treatments were case reports or series. Large randomized controlled trials and retrospective cohort studies were scarce, which limits our ability to draw definitive conclusions regarding the efficacy of the reported treatment modalities. Oral retinoids and PDT were the most extensively studied medical and procedural treatments, respectively.

The treatment of DCS remains a challenge for dermatologists due to the lack of standardized, evidence-based guidelines. Although the pathogenesis of DCS is poorly understood, it is believed that epithelial shedding is the initial inciting event that leads to hyperkeratosis and dilatation within the hair follicle. The distended follicle ruptures, which propagates a dysregulated inflammatory response and results in the formation of nodules and abscesses followed by fistulas and scarring [51]. DCS shares several commonalities with HS in terms of suspected pathogenesis and treatments, and some posit that DCS may be a variant of HS [52]. However, there are differences between the two conditions as well. DCS appears to be more responsive to oral retinoids compared with HS, which exhibits a mixed and inconsistent response to oral retinoids. Furthermore, at least in Western nations, HS has been found to predominantly affect women [53], whereas DCS affects men in a highly disproportionate manner.

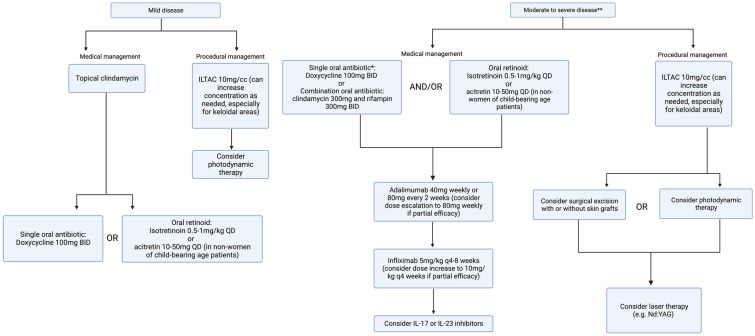

Based on findings from this systematic review and the authors’ expert opinion, we developed a treatment algorithm for DCS to help guide clinicians (Fig. 2). We recommend using systemic antibiotics and intralesional steroid injections to help control symptoms based on the safety profile and fast onset of action of these therapies. Tetracyclines are the most studied antibiotic class for DCS; however, other antibiotics have also shown benefit in case of treatment failure and non-tolerance, including azithromycin, trimethoprim–sulfamethoxazole, and dapsone. Similar to HS, dual antibiotic combination therapy such as clindamycin and rifampin may also be utilized for more symptomatic cases of DCS.

Fig. 2.

Dissecting cellulitis of the scalp treatment algorithm.†BID, twice a day; CO2, carbon dioxide; IL, interleukin; ILTAC, intralesional triamcinolone; kg; kilogram; mg, milligram; ND:YAG, neodymium-doped yttrium–aluminum–garnet; q, every; QD, daily. †Algorithm developed on the basis of systematic review and authors’ expert opinion. *Other systemic antibiotic therapy to consider if patient fails or is intolerant to tetracyclines: dapsone, azithromycin, trimethoprim–sulfamethoxazole, cephalexin. **Consider oral prednisone 0.5–1 mg/kg for a 2–4 week taper as needed for severe flares and as a bridge to longer term therapy. Figure created with biorender.com

Based on available data, oral retinoids are a first-line therapeutic agent for DCS. Clinicians should note that systemic retinoids may require extended periods of treatment in some patients to demonstrate benefit. Optimal dosing regimen for isotretinoin for DCS still needs to be established. Oral retinoids could also potentially be combined with antibiotics to achieve a longer period of disease-free remission. Although isotretinoin was the most extensively studied oral retinoid for DCS in the literature, other options such as acitretin may merit further exploration, especially since acitretin has shown superior efficacy in HS compared with isotretinoin [54]. In addition, unlike HS, DCS predominantly affects men, which makes acitretin a viable treatment option for more patients with DCS, given its teratogenicity and long half-life. Acitretin also imparts a lower burden on prescribers in the USA, since it does not require enrollment in the iPLEDGE program [55]. Of note, tetracyclines and isotretinoin should not be used concomitantly due to the increased risk of pseudotumor cerebri.

For patients with DCS that is recalcitrant to oral antibiotics and retinoids, biologic agents are a long-term treatment option that should be considered. TNF-alpha antagonists such as ADA and IFX currently have the most, albeit also limited, data. Any patient who presents with concomitant moderate to severe HS should be offered a biologic agent if there are no contraindications. Our study found that nearly one-half of the 34 patients who received treatment with biologics for DCS also had HS. The concomitant use of biologics and retinoids merits further investigation along with the use of biologics in conjunction with surgical treatments, which has demonstrated benefit in HS [56]. Furthermore, larger studies on biologic use in DCS, including IL-17, IL-23, or IL-12/23 inhibitors, are warranted. For patients with recalcitrant DCS symptoms, oral steroids such as prednisone may be considered as a rescue treatment and as a bridge to other long-term treatment options such as biologics, retinoids, or surgical excision. Finasteride is an adjunct treatment that also merits further investigation in DCS.

Surgical excisions may be needed when a patient’s disease is refractory to medical management. No recurrence was observed in any of the patients treated with excisions and all patients had improvement in DCS lesions. Notably, excisions with and without skin grafts in the study had low rates of complications, although the sample size was small. More studies are warranted to investigate the optimal surgical approach to DCS.

Although intralesional steroid injections were only reported in 2 patients, this commonly used intervention is probably simply underreported in the literature. PDT and laser treatments may be useful non-invasive interventions for patients who fail medical management. Combining medical and non-invasive procedural treatments may lead to longer periods of remission, as demonstrated by Su et al.’s study on isotretinoin combined with PDT. Further studies on laser treatments are also needed to determine the optimal candidates for therapy and treatment frequency.

Lastly, it is essential to note that chronic inflammatory skin diseases such as DCS can impart a substantial psychosocial burden. The location of the abscesses, nodules, and fistulas of DCS on the face and scalp may predispose patients to social isolation, anxiety, and depression. Eliciting and addressing potential concerns regarding relationships and emotional well-being and referring patients to mental health experts when appropriate is warranted.

Our study contributes to the literature by providing an updated, comprehensive systematic review of existing literature on DCS treatments to guide clinicians in their discussions with patients. Study limitations include an overall small number of studies and patients for each type of intervention. There is also risk of reporting bias since the majority of studies were case reports or series. In addition, there was heterogeneity between studies in timepoints for efficacy measurement as well as outcome measurement. Therefore, the results of this study should be interpreted with caution.

Overall, clinicians and patients should be aware that data regarding available DCS treatment options are limited and largely based on case reports and case series. Randomized controlled trials and large cohort studies are needed to compare the efficacy and optimal dosing of different treatment regimens and aid in the development of evidence-based guidelines for DCS treatment. Further studies are needed to characterize the subsets of patients who would be most likely to benefit from specific treatment regimens. Moreover, standardized treatment outcomes will allow for more rigorous comparisons across studies. A potential new era of treatment for DCS is on the horizon with the recent advances in biologic and small molecule inhibitor therapies, but further investigation is needed.

Author Contribution

Rahul Masson: drafting of the manuscript, checking data. Charlotte Y. Jeong: data acquisition, checking data, critical revision of the manuscript. Elaine Ma: data acquisition, checking data, critical revision of the manuscript. Natalie M. Fragoso: critical revision of the manuscript. Ashley B. Crew: critical revision of the manuscript. Vivian Y. Shi: critical revision of the manuscript. Jennifer L. Hsiao: concept and design, critical revision of the manuscript, supervision and administration.

Funding

No funding or sponsorship was received for this study or publication of this article.

Data Availability

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no new data were created or analyzed in this study.

Declarations

Conflict of Interest

Natalie M. Fragoso is an investigator for Acelyrin. Vivian Y. Shi is on the board of directors for the Hidradenitis Suppurativa Foundation (HSF), is an advisor for the National Eczema Association, is a stock shareholder of Learn Health, and has served as an advisory board member, investigator, speaker, and/or received research funding from Sanofi Genzyme, Regeneron, AbbVie, Genentech, Eli Lilly, Novartis, SUN Pharma, LEO Pharma, Pfizer, Incyte, Boehringer Ingelheim, Alumis Aristea Therapeutics, Menlo Therapeutics, Dermira, Burt’s Bees, Galderma, Kiniksa, UCB, Target-PharmaSolutions, Altus Lab/cQuell, MYOR, Polyfins Technology, GpSkin, and Skin Actives Scientific. Jennifer L. Hsiao is on the board of directors for the Hidradenitis Suppurativa Foundation, has served as a consultant for Aclaris, Boehringer Ingelheim, Novartis, and UCB, and has served as a consultant and speaker for AbbVie. Rahul Masson, Charlotte Y. Jeong, Elaine Ma, and Ashley B. Crew report no conflicts of interest.

Ethical Approval

This article is based on previously conducted studies and does not contain any new studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

References

- 1.Vasanth V, Chandrashekar BS. Follicular occlusion tetrad. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2014;5(4):491–493. doi: 10.4103/2229-5178.142517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Malviya N, Garg A. Comorbidities and Systemic Associations. In: A Comprehensive Guide to Hidradenitis Suppurativa. Elsevier; 2022:69–76. 10.1016/B978-0-323-77724-7.00008-5

- 3.Brănişteanu DE, Molodoi A, Ciobanu D, et al. The importance of histopathologic aspects in the diagnosis of dissecting cellulitis of the scalp. Rom J Morphol Embryol. 2009;50(4):719–724. [PubMed]

- 4.Badaoui A, Reygagne P, Cavelier-Balloy B, et al. Dissecting cellulitis of the scalp: a retrospective study of 51 patients and review of literature. Br J Dermatol. 2016;174(2):421–423. doi: 10.1111/bjd.13999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Higgins JPT, Altman DG, Gøtzsche PC, et al. The Cochrane Collaboration’s tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ. 2011;343:d5928. 10.1136/bmj.d5928 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 6.Wells G, Shea B, Peterson J, Welch V, Losos M, Tugwell P. The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for assessing the quality of nonrandomised studies in meta-analyses.

- 7.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6(7):e1000097. 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 8.Gamissans M, Romaní J, López-Llunell C, Riera-Martí N, Sin M. Dissecting cellulitis of the scalp: A review on clinical characteristics and management options in a series of 14 patients. Dermatol Ther. 2022;35(8):e15626. 10.1111/dth.15626 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Karpouzis A, Giatromanolaki A, Sivridis E, Kouskoukis C. Perifolliculitis capitis abscedens et suffodiens successfully controlled with topical isotretinoin. Eur J Dermatol. 2003;13(2):192–195. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Navarro-Triviño FJ, Almazán-Fernández FM, Ródenas-Herranz T, Ruiz-Villaverde R. Dissecting cellulitis of the scalp successfully treated with topical resorcinol 15. Dermatol Ther. 2020;33(3):e13406. 10.1111/dth.13406 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11.Scheinfeld N. Dissecting cellulitis (Perifolliculitis Capitis Abscedens et Suffodiens): a comprehensive review focusing on new treatments and findings of the last decade with commentary comparing the therapies and causes of dissecting cellulitis to hidradenitis suppurativa. Dermatol Online J. 2014;20(5):22692. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Abdennader S, Vignon-Pennamen MD, Hatchuel J, Reygagne P. Alopecic and aseptic nodules of the scalp (pseudocyst of the scalp): a prospective clinicopathological study of 15 cases. Dermatology. 2011;222(1):31–35. doi: 10.1159/000321475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Melo DF, Jorge Machado C, Bordignon NL, da Silva LL, Ramos PM. Lymecycline as a treatment option for dissecting cellulitis and folliculitis decalvans. Dermatol Ther. 2020;33(6):e14051. 10.1111/dth.14051 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 14.Chu S, Michelle L, Ekelem C, Sung CT, Rojek N, Mesinkovska NA. Oral isotretinoin for the treatment of dermatologic conditions other than acne: a systematic review and discussion of future directions. Arch Dermatol Res. 2021;313(6):391–430. doi: 10.1007/s00403-020-02152-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Melo DF, Trüeb RM, Dutra H, Lima MMDA, Machado CJ, Dias MFRG. Low-dose isotretinoin as a therapeutic option for dissecting cellulitis. Dermatol Ther. 2020;33(6):e14273. 10.1111/dth.14273 [DOI] [PubMed]