Abstract

The food-grade yeast Candida utilis has been engineered to confer a novel biosynthetic pathway for the production of carotenoids such as lycopene, β-carotene, and astaxanthin. The exogenous carotenoid biosynthesis genes were derived from the epiphytic bacterium Erwinia uredovora and the marine bacterium Agrobacterium aurantiacum. The carotenoid biosynthesis genes were individually modified based on the codon usage of the C. utilis glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase gene and expressed in C. utilis under the control of the constitutive promoters and terminators derived from C. utilis. The resultant yeast strains accumulated lycopene, β-carotene, and astaxanthin in the cells at 1.1, 0.4, and 0.4 mg per g (dry weight) of cells, respectively. This was considered to be a result of the carbon flow into ergosterol biosynthesis being partially redirected to the nonendogenous pathway for carotenoid production.

Carotenoids are yellow, orange, and red pigments which are widely distributed in nature (3). Industrially, carotenoid pigments such as β-carotene are utilized as food or feed supplements. β-Carotene is also a precursor of vitamin A in mammals (11). Recently, carotenoids have attracted greater attention, due to their beneficial effect on human health: e.g., the functions of lycopene and astaxanthin include strong quenching of singlet oxygen (12), involvement in cancer prevention (2), and enhancement of immune responses (6). Astaxanthin has also been exploited for industrial use, principally as an agent for pigmenting cultured fish and shellfish.

The genes responsible for the synthesis of carotenoids such as lycopene, β-carotene, and astaxanthin have been isolated from the epiphytic Erwinia species or the marine bacteria Agrobacterium aurantiacum and Alcaligenes sp. strain PC-1, and their functions have been elucidated (13, 14). The first substrate of the encoded enzymes for carotenoid synthesis is farnesyl pyrophosphate (diphosphate) (FPP), which is the common precursor for the biosynthesis of numerous isoprenoid compounds such as sterols, hopanols, dolicols, and quinones. The ubiquitous nature of FPP among yeasts has been utilized in the microbial production of lycopene and β-carotene by the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae carrying the Erwinia uredovora carotenogenic genes (19). However, the amount of carotenoids produced in these hosts was only 0.1 mg of lycopene and 0.1 mg of β-carotene per g (dry weight) of cells, respectively.

The edible yeast Candida utilis is generally recognized as a safe substance by the Food and Drug Administration. Large-scale production of the yeast cells has been developed with cheap biomass-derived sugars as the carbon source for the production of single-cell protein and several chemicals such as glutathione and RNA (1, 4). This yeast was also found to accumulate a large amount of ergosterol in the cell during stationary phase (6 to 13 mg/g [dry weight] of cells) (17). Thus, C. utilis has the potential to produce a large amount of carotenoids by redirecting the carbon flux for the ergosterol biosynthesis into the nonendogenous pathway for carotenoid synthesis via FPP. Previously, a C. utilis strain was made to produce lycopene (0.8 mg/g [dry weight]) by expressing the three nonmodified genes crtE, crtB, and crtI derived from E. uredovora (15).

In this paper, the de novo biosynthesis of lycopene, β-carotene, and astaxanthin has been performed in C. utilis by using six carotenogenic genes, which were synthesized according to the codon usage of the C. utilis glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAP) gene, which is expressed at high levels. By this approach, increased carotenoid production in C. utilis was achieved.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Synthesis of the six genes crtE, crtB, crtI, crtY, crtZ, and crtW.

The six carotenoid biosynthesis genes crtE, crtB, crtI, and crtY from E. uredovora (13) and crtZ and crtW from A. aurantiacum (14) were modified. The nucleotide sequences of the six genes were designed based on the codon usage frequently used in the GAP gene of C. utilis (8, 9), without modification to the amino acid sequences of the encoded polypeptides. Each gene was designed to be divided into two to six components as units synthesized chemically and by PCR. Unique restriction sites were created at both ends of the components to facilitate the following ligation reaction. An XbaI site was generated at the 5′ end and a BglII site was generated at the 3′ end of each of the crt genes. The crtE gene, encoding 302 amino acids, was divided into four parts. The crtB gene, which coded for 309 amino acids, was divided into three pieces. The crtI gene, encoding 492 amino acids, was divided into six parts. The crtY gene, which coded for 382 amino acids, was divided into four pieces. The crtZ gene, encoding 175 amino acids, and the crtW gene, encoding 243 amino acids, were divided into two and three parts, respectively. In each part, four to six oligonucleotides of 65 to 100 bases were chemically synthesized. Their termini were designed to be complementary to each other. PCR was sequentially carried out with the pairs of nucleotides to synthesize the complete double-strand fragments of the individual parts. These products were separately cloned into the pT7blue (Invitrogen) or pUC118 (Takara) HincII site, whose nucleotide sequences were confirmed by an ABI 373A sequencer (Applied Biosystems). The XbaI-BglII fragments carrying the individual crt genes were finally synthesized by ligating the respective components after digestion with the appropriate restriction enzymes.

Construction of expression units of crtE, crtB, crtI, crtY, crtZ, and crtW genes.

A 0.9-kb XbaI-BglII fragment containing the crtE gene was inserted into the XbaI-BamHI site of plasmid pGAPPT10, which contains the 1.0-kb promoter and the 0.8-kb terminator fragments of the GAP gene (9). The resulting plasmid was pGAPE1. To construct an expression unit for the crtI gene, plasmid pPGKPT5, containing the 0.8-kb promoter and the 0.8-kb terminator regions of the phosphoglycerate kinase (PGK) gene from C. utilis, was used (8). Plasmid pPGKPT6 was constructed from pPGKPT5 by ligating Sse8387I linkers at the blunted SphI site, which is located 0.8 kb upstream of the initiation codon of the PGK gene. A 1.5-kb crtI XbaI-BglII fragment was inserted between the XbaI and BamHI sites of pPGKPT6 to construct plasmid pPGKI1.

P14 and P57 promoters were cloned from C. utilis with a promoter cloning vector (8). Approximately 1.0-kb NotI-XbaI P14 and P57 promoter fragments along with the 0.4-kb XbaI-NotI terminator region of the plasma membrane ATPase (PMA) gene were inserted into the NotI site of pPGKPT5 and named pP14PT1 and pP57PT1, respectively. A 0.9-kb XbaI-BglII fragment containing the crtB gene was inserted between the XbaI and BamHI sites of pP14PT1 to construct pP14B1. The 1.2-kb XbaI-BglII fragment containing the crtY gene was inserted into the XbaI-BamHI sites of pP57PT1 and pPGKPT6 to construct pP57Y1 and pPGKY1, respectively. A fragment of the crtZ gene was inserted into the XbaI-BamHI site of pP14PT1 to construct plasmid pP14Z1. A 0.75-kb XbaI-BglII crtW fragment was inserted into the XbaI-BamHI site of pGAPPT10 to construct pGAPW1.

Construction of various expression vectors for carotenoid synthesis in C. utilis.

Plasmids including the ribosomal DNA (rDNA) fragment were constructed as follows. A 1.2-kb ApaI fragment containing a part of rDNA was isolated from pCLRE2 (10) and inserted in the ApaI site of pBluescript SK to construct plasmid pCRA1. Plasmid pCRA3 was constructed from pCRA1 by inserting the NotI linkers into the Asp718-digested sites after the Klenow polymerase treatment. The 1.2-kb rDNA NotI fragment of pCRA3 was digested with BglII to generate 0.5-kb and 0.7-kb fragments, which were ligated to the BglII site of plasmid pUCBgl. The resultant plasmid was named pCRA10. pUCBgl had previously been constructed by digesting pUC19 with EcoRI and HindIII and ligating the BglII linkers after Klenow polymerase treatment.

Plasmid pCRA10 was digested with XhoI and PstI and ligated into a 1.4-kb PstI-SalI fragment containing the cycloheximide resistance (CYHr) gene, which was amplified in the region from −405 to +974 of the mutated L41 gene by PCR to construct pCRAL10 (9, 10). A 1.4-kb XhoI-SacI fragment containing the CYHr gene isolated from pCLBS10 (10) and a 3.0-kb SacI-EcoRI rDNA fragment isolated from pCRE2 were simultaneously ligated into the SalI and EcoRI sites of plasmid pUC19NotI. pUC19NotI had been constructed by digesting pUC19 with HindIII and ligating the NotI linkers after Klenow polymerase treatment. The resultant plasmid was named pCLR1. In order to use the L41 gene as an integration target, the CYHr gene was divided into the 0.7- and 0.5-kb PstI-BglII fragments, which were amplified by PCR. The two fragments were inserted into the BglII site of pUCBgl to construct pCL10.

Construction of plasmids for production of lycopene, β-carotene, and astaxanthin in C. utilis.

Plasmid pCLRB was constructed from pCLR1 by inserting the 2.4-kb NotI-PstI fragment of pP14B1 between its PstI and NotI sites. The 2.65-kb NotI-PstI fragment of pGAPE1 and the 3.1-kb Sse8387I-NotI fragment of pPGKI1 were simultaneously inserted into the NotI site of pCLRB to construct plasmid pCLR1EBI-3 for lycopene production (Fig. 1).

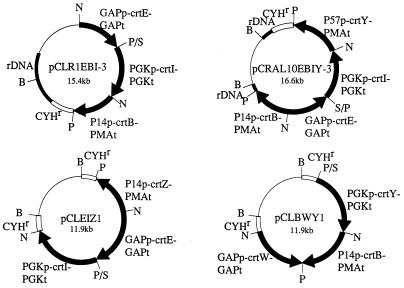

FIG. 1.

Structures of plasmids pCLR1EBI-3, pCRAL10EBIY-3, pCLEIZ1, and pCLBWY1. All of the plasmids contain the CYH resistance (CYHr) gene as a marker gene. The plasmid pCLR1EBI-3 for the production of lycopene has the crtE, crtB, and crtI genes and the rDNA fragment as a target for integration. The three crt genes are driven by the C. utilis GAP, PGK, and P14 promoters and the C. utilis GAP, PGK, and PMA terminator fragments, respectively. The plasmid pCRAL10EBIY-3 for the production of β-carotene has the crtY gene expression cassette that is connected between the P57 promoter and PMA terminator fragments, in addition to the three crt expression cassettes described above. This plasmid contains the rDNA fragment as the target for integration, which is divided by the insertion of bacterial vector sequence. The plasmid pCLEIZ1 has crtE, crtI, and crtZ genes, which are flanked by the C. utilis GAP, PGK, and P14 promoters and the GAP, PGK, and PMA terminator fragments, respectively. The plasmid pCLBWY1 has crtW, crtY, and crtB genes, flanked by the C. utilis GAP, PGK, and P14 promoters and the GAP, PGK, and PMA terminator fragments, respectively, which were used simultaneously to transform C. utilis to produce astaxanthin. Both plasmids use the CYHr gene as the target for integration. Restriction site abbreviations: N, NotI; P, PstI; B, BglII; S, Sse8387I.

Plasmid pCRAL10 was digested with NotI and religated after Klenow polymerase treatment to construct pCRAL10-2. Plasmid pCRAL10BY was constructed by inserting the 2.5-kb NotI-PstI fragment of pP57Y1 and the 2.4-kb NotI-PstI fragment of pP14B1 into the PstI site of pCRAL10-2. The 2.65-kb NotI-PstI fragment of pGAPE1 and the 3.1-kb Sse8387I-NotI fragment of pPGKI1 were inserted into the NotI site of pCRAL10BY to construct plasmid pCRAL10EBIY-3 for β-carotene production (Fig. 1).

Plasmids pCLZ1 and pCLY1 were constructed by inserting the 1.9-kb PstI-NotI fragment of pP14Z1 and the 2.8-kb Sse8387I-NotI fragment of pPGKY1 into the PstI-NotI site of pCL10, respectively. The 3.1-kb Sse8387I-NotI fragment of pPGKI1 and the 2.65-kb NotI-PstI fragment of pGAPE1 were inserted into the NotI site of pCLZ1 to construct plasmid pCLEIZ1 (Fig. 1). The 2.45-kb NotI-PstI fragment of pGAPW1 and the 2.4-kb NotI-PstI fragment of pP14B1 were inserted into the NotI site of pCLY1. The resultant plasmid was named pCLBWY1 (Fig. 1). The plasmid pCLRE2 (10), which contains rDNA and the CYHr gene, was used for construction of the control strain.

Transformation and cultivation of C. utilis.

Transformation of C. utilis IFO 0988 (ATCC 9950) was performed with the plasmids linearized by digestion with BglII according to the procedure described by Kondo et al. (10). Transformants were cultured in YPD (1% yeast extract, 2% peptone, 2% glucose) medium containing cycloheximide (CYH) (40 μg/ml).

Extraction and quantification of carotenoids and ergosterol.

Cells were harvested from culture broth by centrifugation at 3,000 × g for 10 min, washed with distilled water, and lyophilized. Isoprenoids and carotenoids were extracted from yeast cells as follows. One hundred milligrams of the cells was suspended in 2 ml of 0.9 M sorbitol solution containing 0.3 mg of Zymolyase 100T (Seikagaku-kougyou) per ml and incubated for 2 h at 37°C. Glass beads (diameter, 400 to 600 μm; Sigma Chemical Co.) and 10 ml of acetone were added and vortexed to pulverize the cells. After the acetone fraction was collected, petroleum ether extraction was carried out by adding 10 ml of petroleum ether and was repeated two times. The resultant acetone and petroleum ether extracts were evaporated to dryness and dissolved in chloroform-methanol (9:1).

Ergosterol extraction was carried out according to the method of the Japan Food Research Laboratory as follows. The cells were resuspended in 3 ml of NaCl solution (1% [wt/vol]). Then 10 ml of pyrogallol solution (1% [wt/vol] in ethanol), 2 ml of KOH solution (60% [wt/vol]), and 2 g of KOH were added. The mixture was incubated for 30 min at 70°C. A total of 19 ml of NaCl solution (1% [wt/vol]) and 15 ml of hexane-ethyl acetate (9:1) were added to this suspension. This hexane-ethyl acetate extraction was repeated two times. The resultant hexane-ethyl acetate was evaporated and dissolved in chloroform. The extracted isoprenoids, carotenoids, and ergosterol were subjected to high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) as described by Miura et al. (15). For analysis of astaxanthin and the intermediary metabolites after β-carotene, HPLC was also performed as described by Yokoyama et al. (20).

Isolation of RNA and Northern blotting analysis.

Total RNA was isolated from cells by the guanidine-thiocyanate method (16). The RNA was electrophoresed and blotted on a Hybond-N+ membrane (Amersham) and then hybridized with the probe DNA, as described by Sambrook et al. (16). The fragments containing the open reading frames of crtE, crtB, and crtI genes were labeled to make probe DNAs with the Megaprime DNA labeling system (Amersham) as described by the supplier. The actin gene was used as a control probe, which was isolated from C. utilis, with the S. cerevisiae ACT1 gene as a probe (7).

RESULTS

Growth of C. utilis carrying plasmid pCLR1EBI-3 and crt gene expression.

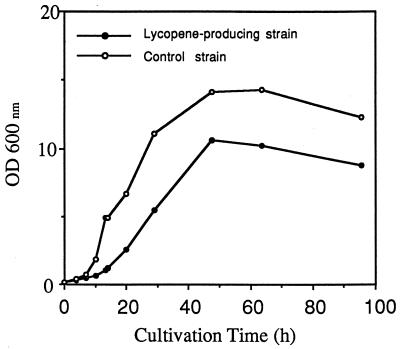

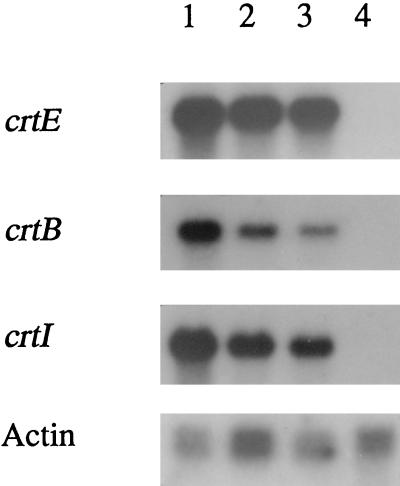

When C. utilis was transformed with the plasmid pCLR1EBI-3, the transformants were visibly red on YPD plates containing CYH. The cells of this C. utilis strain were grown in 500 ml of YPD medium containing 40 μg of CYH per ml for 100 h at 30°C in a 2-liter conical flask. Figure 2 shows the growth curves of the transformant with plasmid pCLR1EBI-3 and the control strain transformed with plasmid pCLRE2. The growth rate of the yeast carrying pCLR1EBI-3 was about half that of the control strain. The total RNA samples were extracted and purified from the cells harvested from the culture shown in Fig. 2, at three time points (14, 27, and 50 h). Figure 3 shows Northern blot analysis of the transformant carrying pCLR1EBI-3, with each crt gene as a probe. The results indicated that the three crt genes were expressed during all growth phases. The control experiments using hybridization with the C. utilis actin gene probe showed that the amount of RNA applied on each lane was approximately the same among all the phases.

FIG. 2.

Growth curves of the strain carrying pCLR1EBI-3 (closed circles) and the strain carrying pCLRE2 (open circles). Cells were cultured in YPD medium containing 40 μg of CYH per ml at 30°C. OD600 nm, optical density at 600 nm.

FIG. 3.

Northern blot hybridization of RNA extracted from the lycopene-producing strain (carrying pCLR1EBI-3) and the control strain (carrying pCLRE2). A total of 2.5 μg of total RNAs extracted from the lycopene-producing strain at 14 (lane 1), 27 (lane 2), and 50 (lane 3) h and from the control strain at 50 h (lane 4) of the culture described for Fig. 2 were applied on each lane. The crt or actin genes are used as the probe for hybridization.

Change of carotenoid and ergosterol contents in C. utilis carrying plasmid pCLR1EBI-3 during cultivation.

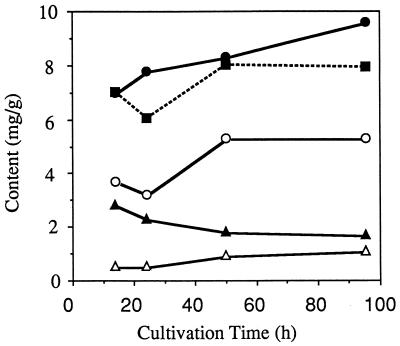

Figure 4 shows the time course fluctuation of carotenoid and ergosterol production in the yeast strain transformed with plasmid pCLR1EBI-3 and the ergosterol level in the control strain. The amount of lycopene per cell weight in the yeast carrying plasmid pCLR1EBI-3 gradually increased and reached 1.1 mg/g (dry weight) in the stationary phase (Fig. 4; Table 1). The ergosterol content per cell weight in the control gradually increased until the cells reached stationary phase. The ergosterol content in the yeast strain harboring pCLR1EBI-3 was significantly lower than that of the control strain. The sum of lycopene, β-carotene, and ergosterol amounts in the strain with pCLR1EBI-3 was similar to the amount of ergosterol in the control strain.

FIG. 4.

Time course fluctuation of carotenoids and ergosterol contents of the lycopene-producing strain (carrying pCLR1EBI-3) and ergosterol content of the control strain (carrying pCLRE2). Symbols: ▵, lycopene; ▴, phytoene; ○, ergosterol content of the lycopene-producing strain; •, ergosterol content of the control strain; ▪, total phytoene, lycopene, and ergosterol contents of the lycopene-producing strain.

TABLE 1.

Content of carotenoids accumulated in C. utilis IFO 0988 transformants carrying various plasmids

| Compound | Content (mg/g [dry wt])

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| pCLR1EBI-3 | pCRAL10EBIY-3 | pCLEIZ1 and pCLBWY1 | |

| Lycopene | 1.1 | 0.1 | 0.2 |

| β-Carotene | 0 | 0.4 | 0.1 |

| Astaxanthin | 0 | 0 | 0.4 |

Production of β-carotene and astaxanthin in C. utilis.

C. utilis transformed with plasmid pCRAL10EBIY-3 to produce β-carotene generated yellow colonies on CYH-containing plates. When plasmids pCLEIZ1 and pCLBWY1 were used to transform C. utilis simultaneously, approximately 10% of the CYH-resistant colonies showed an orange coloration. Table 1 shows the contents of ergosterol and carotenoids in these yeast transformants. The cells were harvested at the stationary phase from YPD liquid culture containing CYH. HPLC analysis revealed that the C. utilis strain carrying pCRAL10EBIY-3 synthesized 0.4 mg of β-carotene per g (dry weight) and that the yeast strain carrying pCLEIZ1 and pCLBWY1 produced 0.4 mg of astaxanthin per g (dry weight) in addition to its intermediates.

DISCUSSION

In the present study, we have modified the six crt genes for carotenoid synthesis based on the frequency of codon usage in the GAP gene. The C. utilis strain carrying plasmid pCLR1EBI-3 produced 1.1 mg of lycopene and 1.7 mg of phytoene per g (dry weight) in the stationary phase (Fig. 4 and Table 1). We have previously introduced into C. utilis plasmid pCLEBI13-2, which contains the original crt genes derived from E. uredovora, which were flanked by the promoters and terminators of C. utilis GAP, PGK, and PMA (15). It was shown that this transformant produced 0.8 mg of lycopene and 0.4 mg of phytoene per g (dry weight) (15). The modification of the crt genes increased the amount of lycopene and phytoene produced by about 1.5 and 4.3 times, respectively.

The lycopene content per cell weight in the yeast strain carrying pCLR1EBI-3 increased according to the length of cultivation, with the concomitant decrease of the phytoene content. This change in the ratio of lycopene and phytoene contents in the transformant indicated that phytoene was converted to lycopene during cultivation. However, the relatively high amount of phytoene accumulating even in the stationary phase could indicate that the conversion of phytoene to lycopene may be a rate-limiting step in this yeast strain. Such a phenomenon was not observed in the production of carotenoids in bacteria such as Escherichia coli with the Erwinia crt genes (13). The expression of the three crt genes in the yeast transformants indicates that there is sufficient quality of transcript and presumably protein during cell growth. It is possible, therefore, that the desaturation steps from phytoene to lycopene are not efficient in the yeast membrane environments, perhaps due to the absence of suitable electron carriers required in the dehydrogenation reaction.

The sum of the ergosterol, phytoene, and lycopene contents in the strain carrying pCLR1EBI-3 was almost equal to the content of ergosterol in the control strain (Fig. 4). Therefore, we have considered that the carbon flow for the biosynthetic pathway for ergosterol has been partially redirected from FPP to geranylgeranyl pyrophosphate for subsequent carotenoid production.

We also constructed the β-carotene-producing and astaxanthin-producing C. utilis strains by introducing the metabolic pathway mediated by four crt genes (crtE, crtB, crtI, and crtY) and six crt genes (crtE, crtB, crtI, crtY, crtZ, and crtW), respectively. The content of astaxanthin (0.4 mg/g [dry weight]) in the astaxanthin-producing strain is almost the same as that of the naturally astaxanthin-producing yeast Phaffia rhodozyma, which seems to be one of the most promising biological sources of pigment (5). A transformation system for P. rhodozyma was also developed, although the astaxanthin biosynthesis genes of this yeast are not known (18). Our system using the bacterial crt genes may be also applicable to P. rhodozyma to increase astaxanthin levels.

REFERENCES

- 1.Boze H, Moulin G, Galzy P. Production of food and fodder yeasts. Crit Rev Biotechnol. 1992;12:65–86. doi: 10.3109/07388559209069188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Giovannucci E, Ascherio A, Rimm E B, Stampfer M J, Colditz G A, Willet W C. Intake of carotenoids and retinol in relation to risk of prostate cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1995;87:1767–1776. doi: 10.1093/jnci/87.23.1767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Goodwin T W, Britton G. Distribution and analysis of carotenoids. In: Goodwin T W, editor. Plant pigments. London, United Kingdom: Academic Press; 1988. pp. 61–132. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ichii T, Takenaka S, Konno H, Ishida T, Sato H, Suzuki A, Yamazumi K. Development of a new commercial-scale airlift fermentor for rapid growth of yeast. J Ferment Bioeng. 1993;75:375–379. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Johnson E A, An G-H. Astaxanthin from microbial sources. Crit Rev Biotechnol. 1991;11:297–326. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jyocouchi H, Hill J, Tomita Y, Good R A. Studies of immunomodulating actions of carotenoids. I. Effects of β-carotene and astaxanthin on murine lymphocyte functions and cell surface marker expression in in vivo culture system. Nutr Cancer. 1991;6:93–105. doi: 10.1080/01635589109514148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kondo, K. Unpublished data.

- 8.Kondo, K., S. Kajiwara, and N. Misawa. 1995. A transformation system for the yeast Candida utilis and the expression of heterologous genes therewith. Japanese patent application PCT/JP95/01005.

- 9.Kondo K, Miura Y, Sone H, Kobayashi K, Iijima H. High-level expression of a sweet protein, monellin, in the food yeast Candida utilis. Nature Biotechnol. 1997;15:453–457. doi: 10.1038/nbt0597-453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kondo K, Saito T, Kajiwara S, Takagi M, Misawa N. A transformation system for the yeast Candida utilis: use of a modified endogenous ribosomal protein gene as a drug-resistant marker and ribosomal DNA as an integration target for vector DNA. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:7171–7177. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.24.7171-7177.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Krinsky N I. Carotenoids in medicine. In: Krinsky N I, Mathews-Roth M M, Taylor R F, editors. Carotenoids. Chemistry and biochemistry. New York, N.Y: Plenum Press; 1989. pp. 279–291. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Miki W. Biological functions and activities of animal carotenoids. Pure Appl Chem. 1991;63:141–146. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Misawa N, Nakagawa M, Kobayashi K, Yamano S, Izawa Y, Nakamura K, Harashima K. Elucidation of the Erwinia uredovora carotenoid biosynthetic pathway by functional analysis of gene products expressed in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1990;172:6704–6712. doi: 10.1128/jb.172.12.6704-6712.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Misawa N, Satomi Y, Kondo K, Yokoyama A, Kajiwara S, Saito T, Ohtani T, Miki W. Structure and functional analysis of a marine bacterial carotenoid biosynthesis gene cluster and astaxanthin biosynthetic pathway proposed at the gene level. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:6575–6584. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.22.6575-6584.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Miura, Y., K. Kondo, H. Shimada, T. Saito, K. Nakamura, and N. Misawa. Production of lycopene by the food yeast, Candida utilis, that does not naturally synthesize carotenoid. Biotechnol. Bioeng., in press. [PubMed]

- 16.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shimada, H., Y. Miura, and N. Misawa. Unpublished data.

- 18.Wery J, Gutker D, Renniers A C H M, Verdoes J C, Van Ooyen A J J. High copy number integration into the ribosomal DNA of the yeast Phaffia rhodozyma. Gene. 1997;184:89–97. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(96)00579-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yamano S, Ishii T, Nakagawa M, Ikenaga H, Misawa N. Metabolic engineering for production of β-carotene and lycopene in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem. 1994;58:1112–1114. doi: 10.1271/bbb.58.1112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yokoyama A, Izumida H, Miki W. Production of astaxanthin and 4-ketozeaxanthin by the marine bacterium, Agrobacterium aurantiacum. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem. 1994;58:1842–1844. [Google Scholar]