Abstract

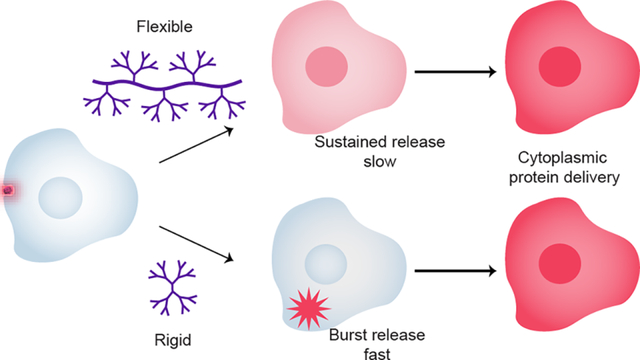

Intracellular protein delivery enables selective regulation of cellular metabolism, signaling, and development through introduction of defined protein quantities into the cell. Most applications require that the delivered protein has access to the cytosol, either for protein activity or as a gateway to other organelles such as the nucleus. The vast majority of delivery vehicles employ an endosomal pathway however, and efficient release of entrapped protein cargo from the endosome remains a challenge. Recent research has made significant advances towards efficient cytosolic delivery of proteins using polymers, but the influence of polymer architecture on protein delivery is yet to be investigated. Here we developed a family of dendronized polymers that enable systematic alterations of charge density and structure. We demonstrate that while modulation of surface functionality has a significant effect on overall delivery efficiency, the endosomal release rate can be highly regulated by manipulating polymer architecture. Notably, we show that large, multivalent structures cause slower sustained release, while rigid spherical structures result in rapid burst release.

Keywords: polymer, dendrimer, protein delivery, endosomal release, controlled release

Graphical Abstract

Introduction

Protein-based therapeutics offer the ability to treat diseases associated with protein deficiencies or mutations, conditions generally considered “undruggable” using small molecule drugs.1 Protein therapeutics have provided new approaches for treatment of disease states including genetic disorders, cancers, and inflammation.2,3 Several notable techniques have been demonstrated for intracellular delivery of proteins, utilizing synthetic approaches to develop carriers, such as liposomes, polymers, and nanoparticles.4–17 These strategies offer ease of functionalization to form stable complexes that prevent denaturation of proteins and can ultimately promote cellular uptake and delivery.18

Despite recent advances however, intracellular protein delivery poses several challenges yet to be overcome.19 The cell membrane is largely impermeable to proteins,20 and internalization often brings the carrier and functional protein into the cell via endosomes. Endosomal release is generally an inefficient process, with only ~1% of the total cargo being released into the cytoplasm, and the remainder being degraded or exocytosed.21,22 Further, intracellular protein concentration is highly dynamic due to constant protein turn over by degradation, and replacement with newly synthesized copies is required to ensure a constant supply of functional proteins.

Controlled release of protein into the cytosol over time is a largely unmet need that would provide for a high level of control over protein activity within the cell.23 Recent work by Wojnilowicz et al. demonstrated endosomal lysis and subsequent burst release of highly branched and rigid cationic polymers, such as dendritic glycogen,24 while Rehman et al. demonstrated burst release, but not complete endosomal rupture, with flexible linear PEI (LPEI), and passive ‘leaky’ release with liposomes where a distinct burst event could not be identified.22 Knowing whether carrier architecture favors burst versus sustained release, and over what time frame, is crucial information that will allow protein carriers to be engineered to optimize therapeutic parameters.

Dendronized polymers present well-defined architectural motifs that have been investigated in recent years as delivery vehicles for therapeutic cargos, including both small molecule and large biologics biomolecules such as plasmid DNA and proteins.25–27 Importantly, these polymer platforms offer a high degree of architectural and functional design space. While most studies to date have focused on the role of surface functionality on protein delivery processes, the choice of polymeric scaffold defines the surface multivalency, and so is a crucial parameter for investigation.

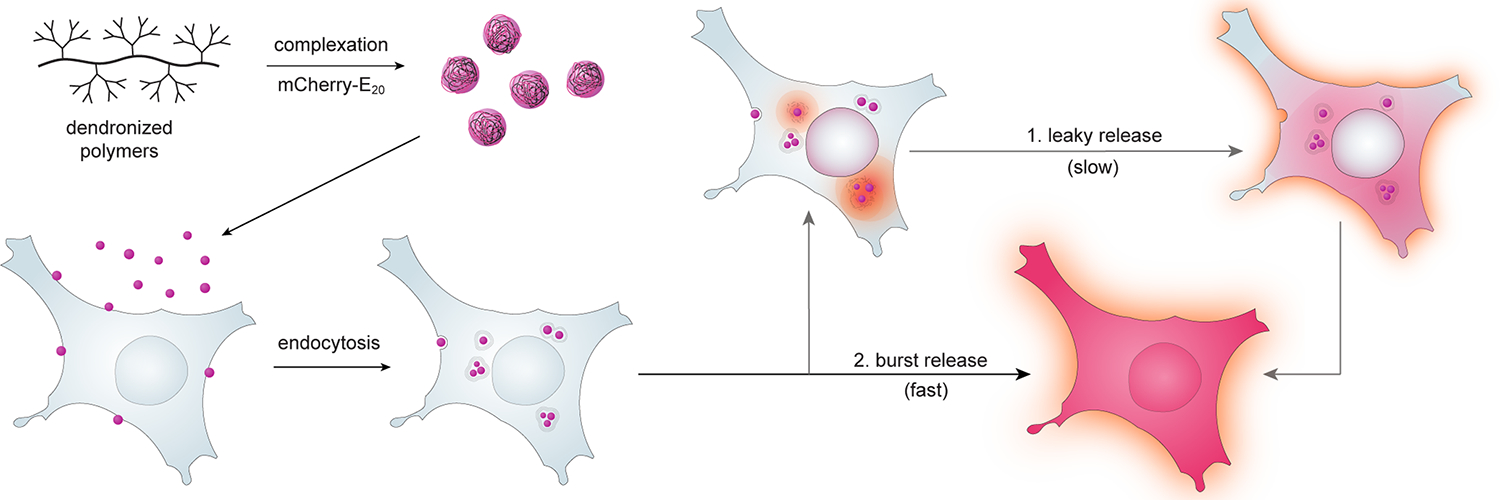

We report here the use of dendronized polymers as versatile protein delivery vehicles featuring temporal control of endosomal release. In this study we evaluated a library of synthetic platforms comprised of copolymers bearing PAMAM dendrons (Figure 1). This scaffold enabled the systematic variation of the dendron generation while varying the degree of dendron substitution along the copolymer backbone.25,28 This library of polymers was additionally modified to afford three different surface functionalities chosen for their documented ability to interact with proteins: primary amines, perfluoroalkyl chains and guanidinium moieties.7–10 These three surface moieties enable differing electrostatic environments, potential to form salt bridges (in the case of guanidinium), and different hydrogen bonding interaction strengths, all of which underpin protein binding, folding and structure, and molecular recognition, and thus are crucial parameters for successful protein delivery.10,29 Importantly, these dendronized polymers demonstrated that endosomal release and rate of cytosolic protein access were directly regulated by both polymer architecture and surface functionality, thereby demonstrating a concise approach to engineering scaffolds for intracellular protein delivery and controlled cytosolic release.

Figure 1. Engineering endosomal release rate through polymer architecture and complexation with E-tagged mCherry.

Polymers were complexed with mCherry-E20 protein and delivered to cells. Controlled endosomal release allowed temporally-regulated access of protein to the cytosol. Free cytosolic mCherry-E20 protein can be visualized throughout the cytosol and within the cell nuclei.

Results and Discussion

Systematic variation of polymer architecture for optimization of intracellular protein delivery.

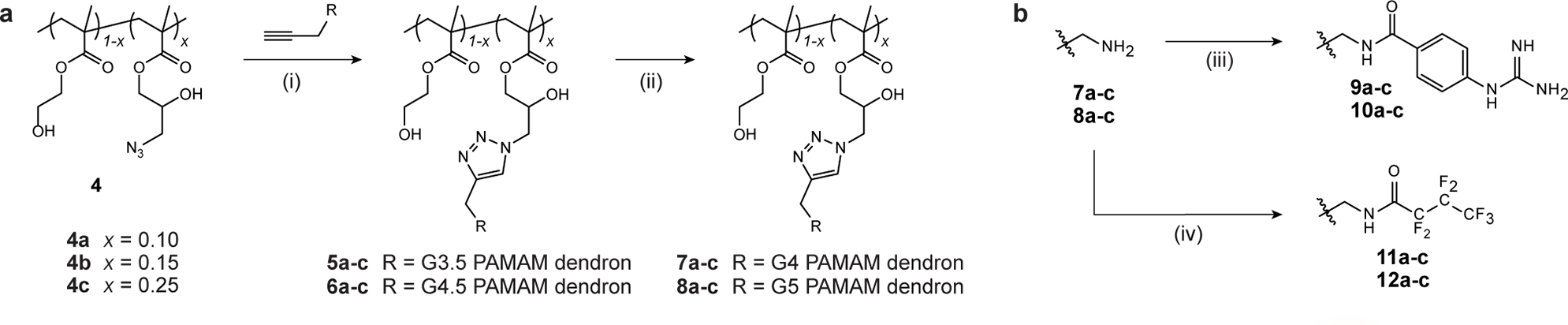

A modular synthetic strategy was adopted to enable independent variation of structure and surface functionality (Scheme 1). The delivery scaffold is built upon a linear poly(hydroxyethyl)-ran-(glycidyl methacrylate) copolymer (p(HEMA-ran-GMA)), with the epoxide moieties reacted to form azide-functionalized polymer 4. Copolymers 4a–c were generated with varying monomer feed ratios and concomitant azide density (1H NMR Figure S1). Generation 3.5 and 4.5 PAMAM dendrons were then anchored onto the linear backbone through copper-catalyzed click chemistry (5a–c and 6a–c respectively). Dendrons were then finalized to G4 and G5, giving amine-terminated dendronized polymers (denpols) 7a–c and 8a–c respectively (Scheme 1a, 1H NMR Figure S2 and S3). These polymers were used as-made, or further functionalized to afford terminal p-guanidinobenzamide (9a–c or 10a–c for G4 and G5 dendrons respectively) or heptafluorobutylamide moieties (11a–c or 12a–c for G4 and G5 dendrons respectively) (Scheme 1b, 1H NMR available in Figure S4).

Scheme 1. Polymeric library design for systematic assessment of protein delivery.

(a) Synthesis of systematically dendronized copolymers. Generation 3.5 (G3.5) and 4.5 (G4.5) PAMAM dendrons were ‘clicked’ onto azido-functionalized copolymer backbones 4a–c, and the generation finalized to give dendronized polymers bearing varying amounts of G4 (7a–c) and G5 (8a–c) dendrons. (b) Partial functionalization of polymer surface by either reaction with p-guanidinobenzoic acid (GBA, polymers 9a–c and 10a–c bearing G4 and G5 dendrons respectively) or heptafluorobutyric anhydride (HFBA, polymers 11a–c and 12a–c bearing G4 and G5 dendrons respectively). Full synthetic conditions are: (i) PMDETA, CuBr, DMF, r.t., 72 h; (ii) ethylenediamine, MeOH, 0 °C; (iii) 1. GBA, EDC, DMF, r.t. 6 h, 2. polymer, TEA, PBS, r.t., 5 d; (iv) HFBA, MeOH (anhydrous), r.t., 48 h.

We employed an inherently fluorescent mCherry protein to quantify delivery timing and efficiency. Fluorescent proteins like mCherry lose their fluorescence upon denaturation due to secondary structural alterations.30 Fluorescence tracking during protein delivery is thus a robust way to evaluate retention of protein structure through the delivery process.31

Complexation was facilitated using the versatile E-tag approach,14 with previously described mCherry-E20 employed for this work. The ~33 kDa size of mCherry-E20 (Figure S5) allows the free protein to diffuse across the cell cytoplasm and into the nucleus,32,33 allowing cytosolic delivery of mCherry-E20 to be conclusively demonstrated by nuclear mCherry fluorescence.

Surface functionality dictates protein delivery efficiency.

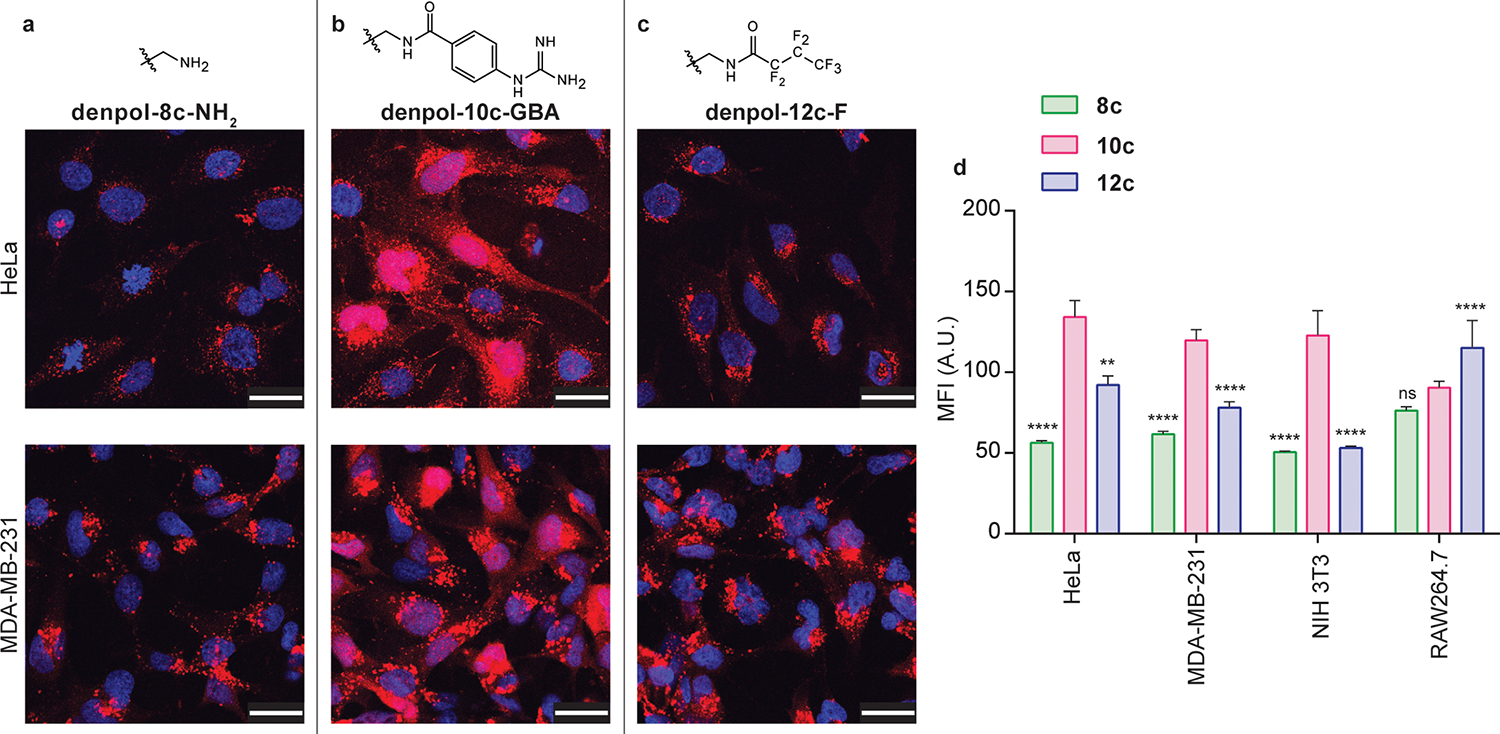

Polymer-mCherry-E20 binding was assessed using DLS and zeta for the resulting hydrodynamic radius and zeta potential, respectively (Figure S6). Protein delivery was initially screened in HeLa cells at 24 h for denpols 7a–c to 12a–c (Figure 2, Figure S7–S11) at two different polymer concentrations, with mCherry-E20 delivered at 750 nM. These denpols are well tolerated both in vitro25,34 and in vivo.28 At 24 h, amine-terminated polymers 7c and 8c demonstrated higher mean fluorescent intensity (MFI) than those originating from backbones 4a–b, with grafting density, suggesting that backbone 4c provided the optimal density for protein delivery a 24 h. This trend was further observed for denpols bearing terminal p-guanidino-benzamide and heptafluorobutylamide moieties (9a–c and 10a–c, and 11a–c and 12a–c respectively). Overall, guanidine-functionalized polymer denpol-10c-GBA resulted in a significantly higher number of mCherry-E20 positive cells compared to fluorinated denpol-12c-F, which in turn outperformed amine-terminated denpol-8c-NH2 (Figure S11).

Figure 2. Protein delivery across cell lines at 24 h.

(a-c) Delivery of mCherry-E20 protein to HeLa and MDA-MB-231 cells using dendronized polymers 8c-NH2, 10c-GBA, and 12c-F, respectively. (d) MFI values for nuclear mCherry-E20 signal for each of the three denpols for HeLa, MDA-MB-231, NIH 3T3 and RAW 264.7 cells. Figures represent a single image taken from the center of a z-stack, to demonstrate nuclear mCherry-E20 signal, scale bars represent 30 μm; nuclei were stained with Hoechst 33342 (blue). Graphs are given as mean ± SE. Statistical analysis was performed using two-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparison (**** p ≤ 0.0001, ns is non-significant).

Delivery trends were established using the most effective polymers from each surface functionality family (denpols 8c, 10c and 12c) in MDA-MB-231 (human mammary adenocarcinoma), NIH 3T3 (murine fibroblast) and RAW 264.7 (murine macrophage) cells. Similar trends were observed across all four cell lines (Figure 2 and S12–14), with denpol-10c-GBA achieving significantly higher delivery efficiencies than fluorinated denpol-12c-F, which was in turn more efficient than denpol-8c-NH2. The increased uptake of fluorinated polymer 12c in the RAW264.7 macrophage cell line may be due to the higher polymer surface hydrophobicity, compared to the amine and guanidine-terminated polymer variants.35–37 Next, we characterized and delivered Granzyme A-E10-polymer complexes to demonstrate the ability of the denpols to deliver an active enzyme (Figure S15). Representative TEM images demonstrate amorphous complex structure (Figure S16). Granzyme A induces apoptosis in cells, and so activity can be monitored via cell viability.38 We observed a similar delivery pattern: delivery with denpol-8c-NH2 had a significant effect on cell viability (~28% decrease), however delivery with denpols 10c-GBA and 12c-F resulted in an even greater effect on cell viability (~45% decrease). Delivery of Granzyme A-E10 with PAMAM, and Granzyme A-E10 alone, demonstrated no significant effect on cell viability. Furthermore, delivery of each of the denpols 8c–12c alone had no significant effect on cell viability.

The effect polymer surface functionalization on delivery kinetics.

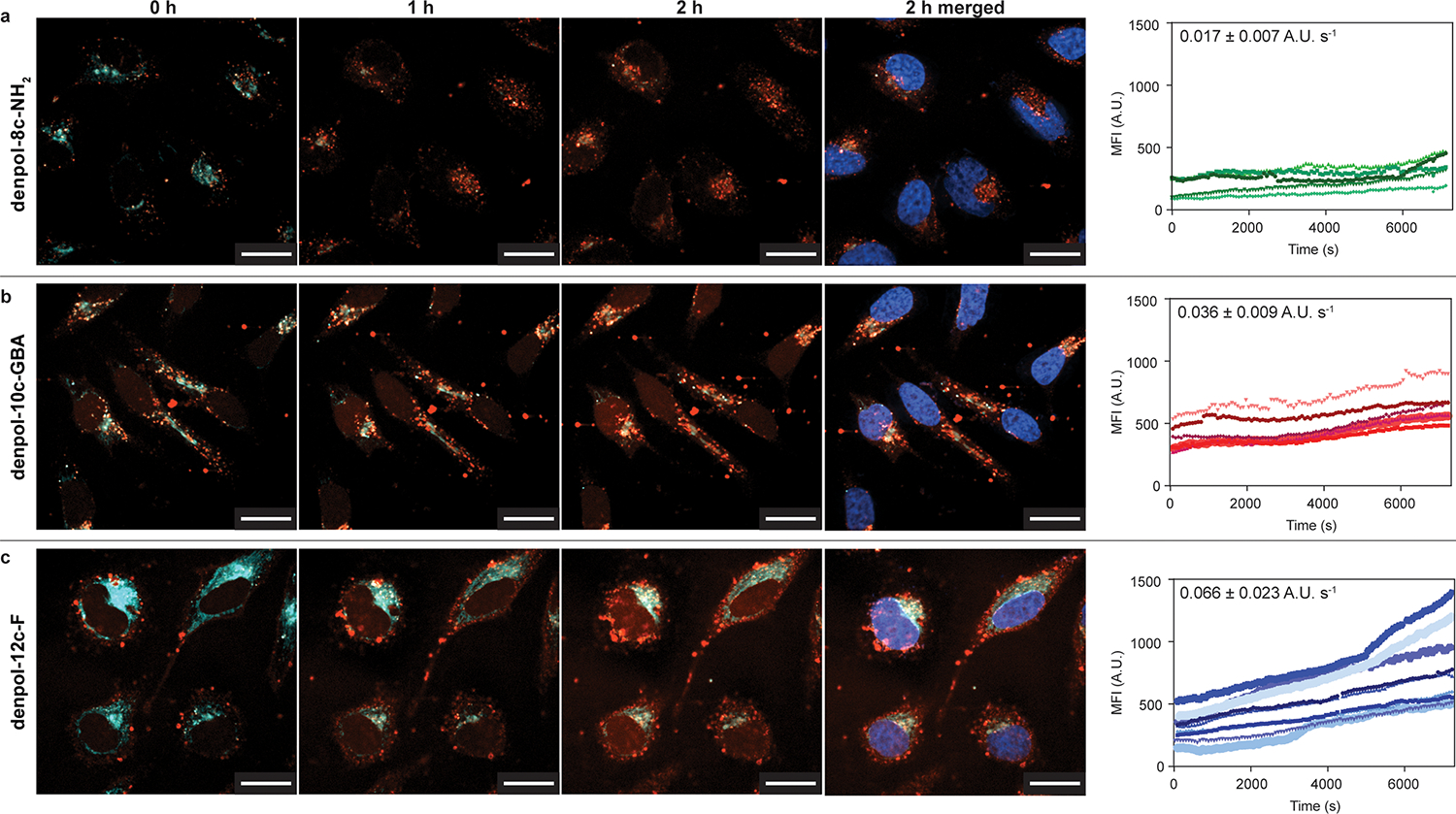

We hypothesized that polymer functionality could dictate delivery kinetics as well as efficiency. We first confirmed non-specific endocytic internalization pathways for all three polymers 8c-NH2, 10c-GBA and 12c-F via small molecule inhibition studies (Figure S17 and S18). We then used spinning-disk confocal microscopy to observe the initial 2 h of mCherry-E20 uptake and release into HeLa cells for the three denpols (Figure 3, and Supplemental movies S1–S3), and mCherry-E20 only (Figure S19). Fluorinated denpol 12c-F demonstrated the fastest endosomal release over the 2 h period, and the amine-terminated denpol 8c- NH2 demonstrated the slowest. This is consistent with previous studies that demonstrated incorporation of perfluoroalkyl chains to enable enhanced endosomal escape and modulate the successful binding/unbinding rate of DNA/dendrimer complexes.39 Interestingly, the release profiles of each of the three denpols were approximately linear rather than defined burst release events, as previously observed with other polymeric systems.22 This gradual release suggests that rather than full endosomal lysis, these polymeric structures cause endosomal ‘leakiness’. Though the rate of release is significantly different for each of the surface functionalities, this ‘leakiness’ is common, to each suggesting that this behavior may be due to the dendronized polymer scaffold itself.24,40 The use of LysoTracker during imaging indicated numerous punctate vesicles which had not yet been acidified, consistent with endosomes that had not completely matured.

Fig 3. Time-lapse endosomal release of mCherry-E20 protein.

mCherry-E20 protein was complexed with polymers and the cell internalization and endosomal release was assessed over 2 h (7200 s) by measuring the fluorescence intensity (A.U.) in cell nuclei over time. Average release rate gradient was calculated and is shown labelled on each plot. The mCherry-E20 is given by red fluorescent signal (punctate, complexed and/or endosomal; diffuse, released), LysoTracker was used to identify acidic compartments and is shown by cyan signal, and the cell nuclei were stained with Hoechst 33342 and are given by the blue signal in ‘2h merged’. (a–c) Snapshots of mCherry-E20 delivered using denpols 8c-NH2, 10c-GBA and 12c-F (respectively) at 0, 1 and 2 h, demonstrating rate of release. Denpol 8c-NH2 demonstrated high levels of punctate signal and limited release, while 10c-GBA and 12c-F additionally demonstrated mCherry-E20 release and diffusion into cell nuclei. Denpol-12c-F demonstrated the fasted mCherry-E20 release rate. Scale bar 20 μm.

Polymer architecture dictates endosomal release rate.

The effects of polymer structure and surface on endosomal release over time was determined using live cell confocal imaging. The role of the polymer scaffold architecture was assessed by comparing denpols 8c-NH2, 10c-GBA and 12c-F with G5 PAMAM dendrimers with either amine (dendrimer-P5-NH2), p-guanidinobenzamide (dendrimer-P5-GBA) or heptafluorobutylamide moieties (dendrimer-P5-F) terminal functionalities. Each of the polymers was modified with a Cy5 fluorescent tag to enable monitoring of the distribution of the polymer as well as the payload. Release profiles for each of the polymers are shown in Figure S20, mCherry-E20 only control is given in Figure S23. For both the PAMAM dendrimer and for our denpols, the slowest release was observed with the terminal amine groups, while terminal perfluoroalkyl moieties caused the fastest protein release, an observation consistent with previous studies.7,9

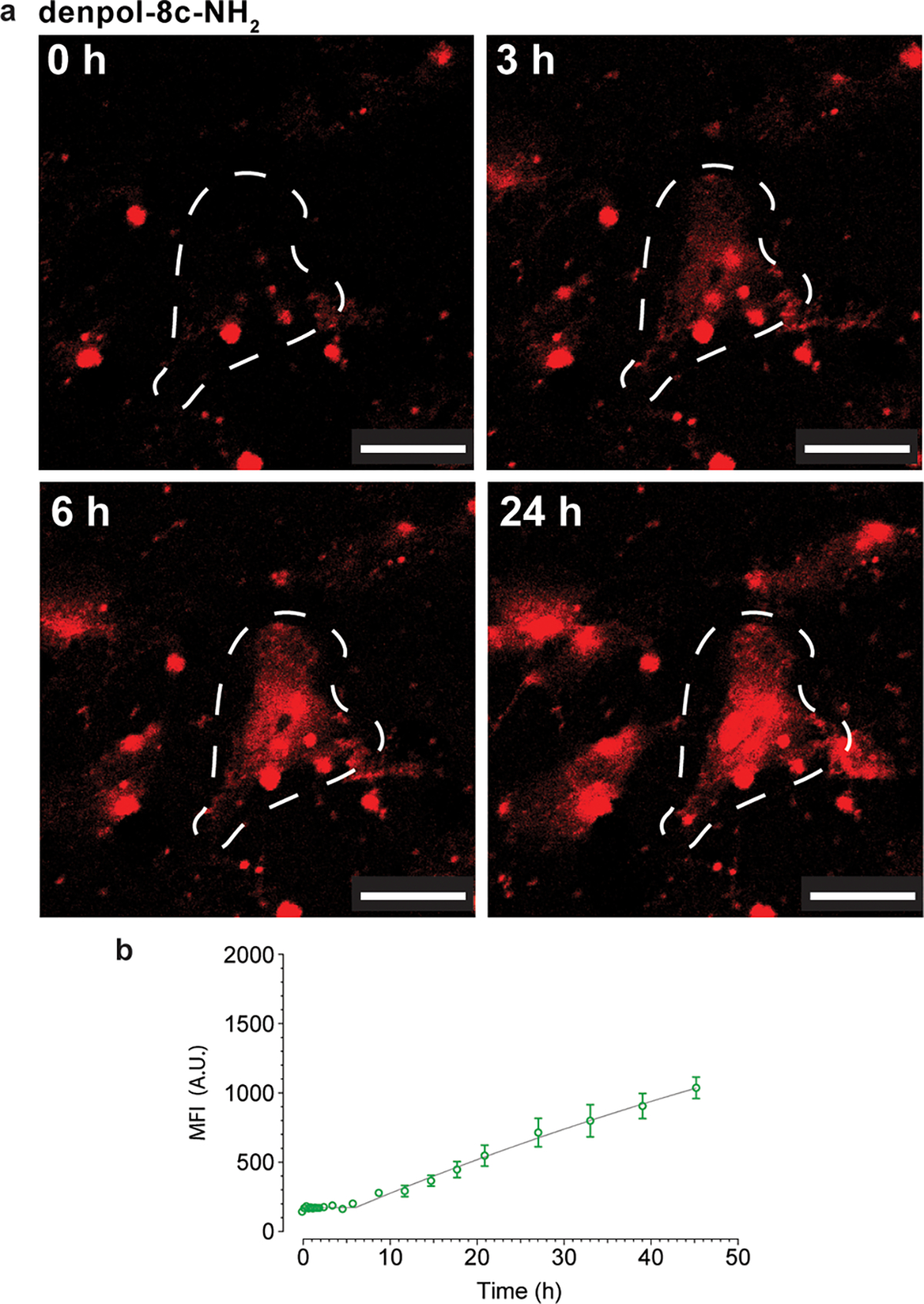

As shown in Figure 4 and Figure S20–S22a polymers using PAMAM as a polymer scaffold have a burst release profile similar to that of previously reported dendritic structures, and achieved maximum fluorescence intensity at ~20 h, 10 h and 6 h for dendrimers P5-NH2, P5-GBA and P5-F respectively. Interestingly, distributing the PAMAM dendrons along a linear backbone resulted in significantly slower release rates than traditional spherical structures, with the amine-terminated denpol 8c-NH2 still releasing protein in a linear manner at ~48 h (Figure 5, S20–S22b). Significantly, in all cases the denpol scaffold was diffused throughout the cell cytosol and nucleus prior to cytosolic protein delivery (Fig S21b). This fluorescence behavior is consistent with partial disassembly occurring within the endosome. In contrast, G5 PAMAM localizes with mCherry-E20 signal and cannot be observed within the cell until cytosolic protein release is also observed (Figure S21a).

Figure 4. Burst cytosolic release of mCherry-E20 protein in HeLa cells.

(a) Delivery of mCherry-E20 protein using PAMAM dendrimer-P5-NH2 at select time points over 90 min and (b) corresponding release profile measured by MFI. MFI measured for full image; dashed white outlines represent qualitative areas of interest, scale bar represents 30 μm.

Figure 5. Controlled cytosolic release of mCherry-E20 protein in HeLa cells.

(a) Delivery of mCherry-E20 protein using denpol-8c-NH2 over 24 h and (b) corresponding release profile measured by MFI. MFI measured for full image; dashed white outlines represent qualitative areas of interest, scale bar represents 30 μm.

These findings collectively suggest that large multivalent, flexible structures have increased membrane interaction compared to the rigid spherical surface of traditional higher-generation dendrimers. This increased interaction induces membrane ‘leakiness’ in the endosome, rather than distinct burst events, providing a temporally-altered release profile.

Conclusion

We have engineered polymers with parametrically varied scaffold architectures and surface functionalities and identified design parameters for temporally-controlled endosomal release/cytosolic protein delivery. This work demonstrates that large multivalent dendronized polymers enabled membrane ‘leakiness’ instead of the distinct burst events previously reported for polymeric and dendritic structures. Overall delivery efficiency was highest using guanidium-functionalized polymers. Polymer surface coverage was an important determinant of protein release kinetics, with the release rate of fluorinated > guanidino > amine-decorated polymers. These findings provide a roadmap for the design of protein delivery vehicles for temporally-controlled endosomal release, providing a powerful tool for controlled dosing of therapeutic proteins.

Materials and Methods

All chemicals were purchased from Sigma Aldrich and used without further purification unless otherwise stated. PAMAM G5.0 dendrimer with an ethylene diamine core was purchased (cat. 536709) as a 5 wt% solution in methanol and was dialysed against distilled water and lyophilized prior to use.

Polymer synthesis and characterization.

Detailed methods for polymer synthesis and characterization can be found in Supplementary Information. Polymer library was synthesized as previously described.25

Protein engineering and production.

mCherry plasmid (Addgene plasmid #54630) was digested with EcoRI/XhoI (NEB) and cloned into a pQE80 vector, modified in- house with glutamic acid tags (E-tag, En, where n = 20), as previously described,14 was transformed into competent BL21(DE3) E. coli and were grown in 3 × 1 L 2×YT media at 37 °C in a shaking incubator until OD600 = 0.6, and then induced with 0.5 mM IPTG with shaking for a further 16 h at 16 °C. Cells were collected by centrifugation (3,200 g, 10 min, 4 °C), supernatant was discarded, and cells were resuspended in lysis buffer (50 mM Tris, 25 mM NaCl, 2 mM EDTA, pH 8 and were lysed by using 1% Triton X-100 (30 min, 37 °C, shaking) and then DNase-I (200 U mL−1, 15 min, 37 °C, shaking) treatment. Lysed cells were then centrifuged (20,800 g, 30 min), the supernatant was collected and 150 mM NaCl was added. mCherry-E20 was then purified using a HisPur cobalt column (Thermo Fisher) as per the manufacturer’s protocol. The column was washed with 1× PBS with 2 mM imidazole, eluted (150 mM imidazole, 50 mM NaH2PO4 and 300 mM NaCl), purified by dialysis in PBS (2 × 4 L, 10 kDa MWCO membrane), aliquoted and stored (−20 °C). Purity was checked using a 12% SDS-PAGE gel.

Polymer–protein complex characterization.

Polymer–protein complexes were characterized by dynamic light scattering (DLS) and zeta potential measurements, to determine the size and charge of the polymer–peptide complexes respectively. Briefly, polymer solutions were mixed with 2.6 μg of mCherry-E20 (3.6 μL, 22.0 μm) at various mass ratios. Complexes were incubated at r.t. for 30 min in ddH2O (pH ~6). The size and zeta potential of the resulting complexes were then measured using a Malvern Zetasizer Nano ZS. Measurements were taken in triplicate after an initial equilibrium period of 2 min. For calibration of the measurements, ‘material’ was defined as PGMA (refractive index of 1.515 and absorbance of 0.05) and ‘dispersant’ was defined as water at 25 °C (refractive index of 1.330 and viscosity of 0.887). The intensity-weighted hydrodynamic radius and zeta potentials of the complexes are presented as mean ± standard deviation.

Cell culture and delivery.

HeLa (human cervical adenocarcinoma cell line, ATCC), were cultured in low glucose Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium (DMEM, Gibco), with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and 1× penicillin-streptomycin solution (Corning). MDA-MB-231, NIH 3T3, and RAW 264.7 were obtained from ATCC and cultured in serum and antibiotic-containing high glucose DMEM. All cell lines were grown in a humidified incubator at 37 °C with 5% CO2. For delivery experiments, cell lines were seeded in four well Lab-Tek chambered slides, or chambered coverglass (Thermo Fisher), for fixed and live cell imaging respectively.

For protein delivery experiments, cell seeding densities were as follows: HeLa, MDA-MB-231 and NIH 3T3 at 8.0 × 104 cells mL−1 for four-well slides and at 1.5 × 105 cells mL−1 for confocal dishes. RAW 264.7 at 1.0 × 105 cells mL−1 for four-well slides and at 2.0 × 105 cells mL−1 for confocal dishes, all to provide a confluency of ~80% at time of delivery. Cells were seeded 16–24 h prior to the delivery experiment. Polymer and protein solutions diluted to working concentration in PBS, and were mixed based on mass ratio, for a final protein concentration of 750 nM in the total 500 μL well volume. Polymer–protein solutions were mixed thoroughly and incubated at r.t. for 30 min. Cells were washed with PBS and media was replaced with 200 μL OptiMEM. Delivery cocktails were then added dropwise to the appropriate wells and were incubated for 4 h before the addition of 250 μL of complete culture medium. Cells were incubated for a further 20 h before being fixed with 2% PFA, and mounted with Fluoromount G (for fixed cell imaging at 24 h). For 48 h live cell experiments, cells were treated as described above, but incubated for a further 44 h. For 2 h live cell experiments, imaging was done in PBS.

Endocytic and membrane fusion inhibitors were used to prevent endocytic or non-endocytic uptake into cells, respectively. Cells were seeded 16 to 24 h before at previously described cell densities. Cells were then washed 2× with PBS and pretreated with wortmannin (150 ng mL−1), chlorpromazine (1.5 μg mL−1), nystatin (50 μg mL−1) or methyl-β-cyclodextrin (7.5 mg mL−1) in DMEM for 1 h at 37 °C and 5% CO2. Following pretreatment, cells were washed 2× with PBS, and polymer–protein assemblies in DMEM were added. After 4 h, media was removed, cells were washed 2× with PBS, and fresh media was applied. Confocal microscopy experiments were performed after 24 h incubation.

Statistical analysis.

Statistical analysis were performed with Graphpad Prism v6.0 (GraphPad Software Inc.). The specific analysis performed is detailed in the corresponding figure caption.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

This work was supported by the NIH (DK121351 and EB022641 to VMR and National Service Award GM008515 to DCL), the Australian Research Council (ARC) and the National Health & Medical Research Council (NHMRC) of Australia. The authors would like to acknowledge the facilities and the technical assistance of the Australian Microscopy & Microanalysis Research Facility at the Centre for Microscopy, Characterisation & Analysis, The University of Western Australia, a facility funded by the University, State and Commonwealth Governments. In addition, the authors would like to acknowledge the Light Microscopy Core Facility at UMass Amherst and the assistance of Dr. James Chambers, as well as the Electron Microscopy Core Facility at UMass Amherst and the assistance of Dr. Alexander Ribbe. JAK would like to acknowledge the support of the Australian-American Fulbright Association and Cancer Council WA.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

- (1).Lee Y-W; Luther DC; Kretzmann JA; Burden A; Jeon T; Zhai S; Rotello VM Protein Delivery into the Cell Cytosol Using Non-Viral Nanocarriers. Theranostics 2019, 9 (11), 3280–3292. 10.7150/thno.34412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2).Leader B; Baca QJ; Golan DE Protein Therapeutics: A Summary and Pharmacological Classification. Nature Reviews Drug Discovery 2008, 7 (1), 21–39. 10.1038/nrd2399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).Zelikin AN; Ehrhardt C; Healy AM Materials and Methods for Delivery of Biological Drugs. Nature Chemistry 2016, 8 (11), 997–1007. 10.1038/nchem.2629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Ménoret S; De Cian A; Tesson L; Remy S; Usal C; Boulé J-B; Boix C; Fontanière S; Crénéguy A; Nguyen TH; Brusselle L; Thinard R; Gauguier D; Concordet J-P; Cherifi Y; Fraichard A; Giovannangeli C; Anegon I Homology-Directed Repair in Rodent Zygotes Using Cas9 and TALEN Engineered Proteins. Scientific Reports 2015, 5 (1), 1–15. 10.1038/srep14410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Remy S; Chenouard V; Tesson L; Usal C; Ménoret S; Brusselle L; Heslan J-M; Nguyen TH; Bellien J; Merot J; De Cian A; Giovannangeli C; Concordet J-P; Anegon I Generation of Gene-Edited Rats by Delivery of CRISPR/Cas9 Protein and Donor DNA into Intact Zygotes Using Electroporation. Scientific Reports 2017, 7 (1), 1–13. 10.1038/s41598-017-16328-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).Bekeredjian R; Chen S; Grayburn PA; Shohet RV Augmentation of Cardiac Protein Delivery Using Ultrasound Targeted Microbubble Destruction. Ultrasound in Medicine and Biology 2005, 31 (5), 687–691. 10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2004.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Zhang Z; Shen W; Ling J; Yan Y; Hu J; Cheng Y The Fluorination Effect of Fluoroamphiphiles in Cytosolic Protein Delivery. Nature Communications 2018, 9 (1), 1–8. 10.1038/s41467-018-03779-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Yu C; Tan E; Xu Y; Lv J; Cheng Y A Guanidinium-Rich Polymer for Efficient Cytosolic Delivery of Native Proteins. Bioconjugate Chem. 2019, 30 (2), 413–417. 10.1021/acs.bioconjchem.8b00753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).Lv J; He B; Yu J; Wang Y; Wang C; Zhang S; Wang H; Hu J; Zhang Q; Cheng Y Fluoropolymers for Intracellular and in Vivo Protein Delivery. Biomaterials 2018, 182, 167–175. 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2018.08.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).Chang H; Lv J; Gao X; Wang X; Wang H; Chen H; He X; Li L; Cheng Y Rational Design of a Polymer with Robust Efficacy for Intracellular Protein and Peptide Delivery. Nano Lett. 2017, 17 (3), 1678–1684. 10.1021/acs.nanolett.6b04955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).Liu C; Wan T; Wang H; Zhang S; Ping Y; Cheng Y A Boronic Acid–Rich Dendrimer with Robust and Unprecedented Efficiency for Cytosolic Protein Delivery and CRISPR-Cas9 Gene Editing. Science Advances 2019, 5 (6), eaaw8922. 10.1126/sciadv.aaw8922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).Zuris JA; Thompson DB; Shu Y; Guilinger JP; Bessen JL; Hu JH; Maeder ML; Joung JK; Chen Z-Y; Liu DR Cationic Lipid-Mediated Delivery of Proteins Enables Efficient Protein-Based Genome Editing in Vitro and in Vivo. Nature Biotechnology 2015, 33 (1), 73–80. 10.1038/nbt.3081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Lin Y-H; Chen Y-P; Liu T-P; Chien F-C; Chou C-M; Chen C-T; Mou C-Y Approach To Deliver Two Antioxidant Enzymes with Mesoporous Silica Nanoparticles into Cells. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2016, 8 (28), 17944–17954. 10.1021/acsami.6b05834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).Mout R; Yesilbag Tonga G; Wang L-S; Ray M; Roy T; Rotello VM Programmed Self-Assembly of Hierarchical Nanostructures through Protein–Nanoparticle Coengineering. ACS Nano 2017, 11 (4), 3456–3462. 10.1021/acsnano.6b07258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).Tang R; Kim CS; Solfiell DJ; Rana S; Mout R; Velázquez-Delgado EM; Chompoosor A; Jeong Y; Yan B; Zhu Z-J; Kim C; Hardy JA; Rotello VM Direct Delivery of Functional Proteins and Enzymes to the Cytosol Using Nanoparticle-Stabilized Nanocapsules. ACS Nano 2013, 7 (8), 6667–6673. 10.1021/nn402753y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Lee B; Lee K; Panda S; Gonzales-Rojas R; Chong A; Bugay V; Park HM; Brenner R; Murthy N; Lee HY Nanoparticle Delivery of CRISPR into the Brain Rescues a Mouse Model of Fragile X Syndrome from Exaggerated Repetitive Behaviours. Nature Biomedical Engineering 2018, 2 (7), 497–507. 10.1038/s41551-018-0252-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (17).Lee K; Conboy M; Park HM; Jiang F; Kim HJ; Dewitt MA; Mackley VA; Chang K; Rao A; Skinner C; Shobha T; Mehdipour M; Liu H; Huang W; Lan F; Bray NL; Li S; Corn JE; Kataoka K; Doudna JA; Conboy I; Murthy N Nanoparticle Delivery of Cas9 Ribonucleoprotein and Donor DNA in Vivo Induces Homology-Directed DNA Repair. Nature Biomedical Engineering 2017, 1 (11), 889–901. 10.1038/s41551-017-0137-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (18).Dutta K; Hu D; Zhao B; Ribbe AE; Zhuang J; Thayumanavan S Templated Self-Assembly of a Covalent Polymer Network for Intracellular Protein Delivery and Traceless Release. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017, 139 (16), 5676–5679. 10.1021/jacs.7b01214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).Eltoukhy AA; Chen D; Veiseh O; Pelet JM; Yin H; Dong Y; Anderson DG Nucleic Acid-Mediated Intracellular Protein Delivery by Lipid-like Nanoparticles. Biomaterials 2014, 35 (24), 6454–6461. 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2014.04.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (20).Stewart MP; Langer R; Jensen KF Intracellular Delivery by Membrane Disruption: Mechanisms, Strategies, and Concepts. Chem. Rev. 2018, 118 (16), 7409–7531. 10.1021/acs.chemrev.7b00678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (21).Stewart MP; Sharei A; Ding X; Sahay G; Langer R; Jensen KF In Vitro and Ex Vivo Strategies for Intracellular Delivery. Nature 2016, 538 (7624), 183–192. 10.1038/nature19764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (22).Rehman Z. ur; Hoekstra D.; Zuhorn IS. Mechanism of Polyplex- and Lipoplex-Mediated Delivery of Nucleic Acids: Real-Time Visualization of Transient Membrane Destabilization without Endosomal Lysis. ACS Nano 2013, 7 (5), 3767–3777. 10.1021/nn3049494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (23).Vaishya R; Mitra AK Future of Sustained Protein Delivery. Ther Deliv 2014, 5 (11), 1171–1174. 10.4155/tde.14.86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (24).Wojnilowicz M; Glab A; Bertucci A; Caruso F; Cavalieri F Super-Resolution Imaging of Proton Sponge-Triggered Rupture of Endosomes and Cytosolic Release of Small Interfering RNA. ACS Nano 2019, 13 (1), 187–202. 10.1021/acsnano.8b05151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (25).Kretzmann JA; Ho D; Evans CW; Plani-Lam JHC; Garcia-Bloj B; Mohamed AE; O’Mara ML; Ford E; Tan DEK; Lister R; Blancafort P; Norret M; Iyer KS Synthetically Controlling Dendrimer Flexibility Improves Delivery of Large Plasmid DNA. Chem. Sci. 2017, 8 (4), 2923–2930. 10.1039/C7SC00097A. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (26).Zeng H; Little HC; Tiambeng TN; Williams GA; Guan Z Multifunctional Dendronized Peptide Polymer Platform for Safe and Effective SiRNA Delivery. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013, 135 (13), 4962–4965. 10.1021/ja400986u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (27).Fuhrmann G; Grotzky A; Lukić R; Matoori S; Luciani P; Yu H; Zhang B; Walde P; Schlüter AD; Gauthier MA; Leroux J-C Sustained Gastrointestinal Activity of Dendronized Polymer–Enzyme Conjugates. Nature Chemistry 2013, 5 (7), 582–589. 10.1038/nchem.1675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (28).Kretzmann JA; Evans CW; Moses C; Sorolla A; Kretzmann AL; Wang E; Ho D; Hackett MJ; Dessauvagie BF; Smith NM; Redfern AD; Waryah C; Norret M; Iyer KS; Blancafort P Tumour Suppression by Targeted Intravenous Non-Viral CRISPRa Using Dendritic Polymers. Chem. Sci. 2019, 10 (33), 7718–7727. 10.1039/C9SC01432B. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (29).Hubbard RE; Kamran Haider M Hydrogen Bonds in Proteins: Role and Strength. In: Encyclopedia of Life Sciences (ELS); John Wiley & Sons, Ltd: Chichester, 2010; 10.1002/9780470015902.a0003011.pub2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- (30).Verkhusha VV; Akovbian NA; Efremenko EN; Varfolomeyev SD; Vrzheshch PV Kinetic Analysis of Maturation and Denaturation of DsRed, a Coral-Derived Red Fluorescent Protein. Biochemistry (Moscow) 2001, 66 (12), 1342–1351. 10.1023/A:1013325627378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (31).Enoki S; Saeki K; Maki K; Kuwajima K Acid Denaturation and Refolding of Green Fluorescent Protein. Biochemistry 2004, 43 (44), 14238–14248. 10.1021/bi048733+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (32).Timney BL; Raveh B; Mironska R; Trivedi JM; Kim SJ; Russel D; Wente SR; Sali A; Rout MP Simple Rules for Passive Diffusion through the Nuclear Pore Complex. J Cell Biol 2016, 215 (1), 57–76. 10.1083/jcb.201601004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (33).Lusk CP; King MC The Nucleus: Keeping It Together by Keeping It Apart. Current Opinion in Cell Biology 2017, 44, 44–50. 10.1016/j.ceb.2017.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (34).Kretzmann JA; Feng R; Munshi AM; Ho D; Ranieri AM; Massi M; Saunders M; Norret M; Iyer KS; Evans CW A Facile Methodology Using Quantum Dot Multiplex Labels for Tracking Co-Transfection. RSC Adv. 2019, 9 (35), 20053–20057. 10.1039/C9RA03518D. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (35).Tabata Y; Ikada Y Effect of the Size and Surface Charge of Polymer Microspheres on Their Phagocytosis by Macrophage. Biomaterials 1988, 9 (4), 356–362. 10.1016/0142-9612(88)90033-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (36).He C; Hu Y; Yin L; Tang C; Yin C Effects of Particle Size and Surface Charge on Cellular Uptake and Biodistribution of Polymeric Nanoparticles. Biomaterials 2010, 31 (13), 3657–3666. 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2010.01.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (37).Nie S Understanding and Overcoming Major Barriers in Cancer Nanomedicine. Nanomedicine 2010, 5 (4), 523–528. 10.2217/nnm.10.23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (38).Mout R; Ray M; Tay T; Sasaki K; Yesilbag Tonga G; Rotello VM General Strategy for Direct Cytosolic Protein Delivery via Protein–Nanoparticle Co-Engineering. ACS Nano 2017, 11 (6), 6416–6421. 10.1021/acsnano.7b02884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (39).Wang M; Liu H; Li L; Cheng Y A Fluorinated Dendrimer Achieves Excellent Gene Transfection Efficacy at Extremely Low Nitrogen to Phosphorus Ratios. Nature Communications 2014, 5 (1), 1–8. 10.1038/ncomms4053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (40).Hinde E; Thammasiraphop K; Duong HTT; Yeow J; Karagoz B; Boyer C; Gooding JJ; Gaus K Pair Correlation Microscopy Reveals the Role of Nanoparticle Shape in Intracellular Transport and Site of Drug Release. Nature Nanotechnology 2017, 12 (1), 81–89. 10.1038/nnano.2016.160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.