Abstract

Predation of attached Pseudomonas putida mt2 by the small ciliate Tetrahymena sp. was investigated with a percolated column system. Grazing rates were examined under static and dynamic conditions and were compared to grazing rates in batch systems containing suspended prey. The prey densities were 2 × 108 bacteria per ml of pore space and 2 × 108 bacteria per ml of suspension, respectively. Postingestion in situ hybridization of bacteria with fluorescent oligonucleotide probes was used to quantify ingestion. During 30 min, a grazing rate of 1,382 ± 1,029 bacteria individual−1 h−1 was obtained with suspended prey; this was twice the grazing rate observed with attached bacteria under static conditions. Continuous percolation at a flow rate of 73 cm h−1 further decreased the grazing rate to about 25% of the grazing rate observed with suspended prey. A considerable proportion of the protozoans fed on neither suspended bacteria nor attached bacteria. The transport of ciliates through the columns was monitored at the same time that predation was monitored. Less than 20% of the protozoans passed through the columns without being retained. Most of these organisms ingested no bacteria, whereas the retained protozoans grazed more efficiently. Retardation of ciliate transport was greater in columns containing attached bacteria than in bacterium-free columns. We propose that the correlation between grazing activity and retardation of transport is a consequence of the interaction between active predators and attached bacteria.

Flagellates and small ciliates can control bacterial densities in many ecosystems (2). Protozoan bacterivory has been shown to reduce bacterial numbers and also to enhance bacterial activity (33) and is therefore accepted as a pivotal process in microbial food webs. Protozoan feeding has been studied intensively in pelagic habitats, but little information is available for porous systems (4, 6, 18, 21).

Although interstitial biofilms are a typical habitat for protozoans, the effect of protozoans on biofilm performance and biofilm detachment has been described only qualitatively (16, 19, 29). Protozoan feeding rates on biofilm bacteria have not been directly quantified previously. A protozoan food preference for attached bacteria has been demonstrated in several studies (5, 37, 38), but there is also evidence that adhesion has a protective effect (5, 11). These contradictory results reveal the complex but largely unknown role of attachment in food availability. The influence of interstitial water flow on bacterial predation also has only scarcely been evaluated, although such water flow could potentially control grazing efficiency. It has been proposed that interstitial flow reduces protozoan feeding, since it may cause abrasion of surface-associated tectic predators (28). In pelagic systems, hydrodynamic forces have been shown to influence the availability of suspended bacteria for various protozoan species (24, 36).

Protozoan bacterivory can be quantified by determining individual grazing rates. Processing of bacteria inside food vacuoles (34) has been monitored, and nongrazing subpopulations (23) have been identified. However, in most attempts to determine uptake of bacteria the workers used analogs of native prey (35, 41, 44) or enzymatic tracers (40, 43) to quantify vacuole contents. These approaches suffer from possible selectivity against or in favor of the artificial prey (23, 27, 35). The restrictions of such methods are even more obvious in porous habitats because of the predominance of attached bacteria, which are difficult to simulate by prey analogs (38). It is evident that the adhesion behavior of native bacteria cannot be mimicked with heat-killed, fluorescently labeled cells. Although several studies demonstrated that protozoan grazing occurs in sediments, they were not able to quantify grazing on bacteria embedded in biofilms (3, 8, 14, 17, 26). Hence, the use of unstained, viable prey is necessary to determine grazing rates in porous environments.

In this study, we investigated predation on bacteria attached to glass beads in a well-defined column system by the ciliate Tetrahymena sp. under lotic (percolated) and lentic (static) conditions. We describe below a new application of in situ hybridization with oligonucleotide probes. Hybridization of ingested bacteria inside the food vacuoles of the predators allowed the feeding rates on viable prey to be determined.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Organisms and culture conditions.

The hymenostomatide ciliate Tetrahymena sp. (9) was isolated from sediment from a Swiss prealpine river, Necker River (7). Small volumes (<100 μl) of pore water containing Tetrahymena sp. and indigenous bacteria were transferred into 50 ml of sterile mineral medium containing (per liter) 2.86 g of Na2HPO4 · H2O, 1.46 g of KH2PO4, 0.1 g of MgSO4 · 7H2O, 1 g of NH4NO3, and 0.05 g of Ca(NO3)2 · 4H2O. The medium was amended with 0.87 g of sodium benzoate per liter as the sole source of energy and organic carbon. During repeated transfer into fresh medium, Tetrahymena sp. grazed on indigenous bacteria and outcompeted all other protozoans, as determined by microscopy. Clonal polyxenic cultures of Tetrahymena sp. were obtained by isolating a single individual that was transferred into 50 ml of medium. The body sizes of 64 organisms were measured microscopically. The average length and width of the ellipsoidal cells were 33.2 ± 7.8 and 21.4 ± 4.4 μm, respectively, corresponding to an average body volume of 8,900 ± 5,340 μm3. Cultures containing ciliates and indigenous bacteria were started 3 to 9 days before the grazing experiments were started. Fifty-milliliter portions of medium in 100-ml Erlenmeyer flasks were each inoculated with 100 μl of a stock culture, and the preparations were incubated on a rotary shaker at 25°C and 100 rpm.

Pseudomonas putida mt2 (42), which has been used in several studies on bacterial adhesion (15, 31, 32), was independently cultured overnight in 300-ml portions of the mineral medium described above in 1-liter Erlenmeyer flasks on a rotary shaker at 25°C and 100 rpm. The mean cell volume, 0.73 ± 0.3 μm3 (n = 130), was calculated on the basis of microscopic measurements.

Preparation of cell suspensions.

Cultures of P. putida mt2 were harvested by centrifugation and washed twice in phosphate-buffered saline containing (per liter) 4.93 g of NaCl, 0.29 g of KH2PO4, and 1.56 g of K2HPO4 (PBS1). One part of the concentrate was used for predation experiments with suspended bacteria, and another part was resuspended in PBS1 and adjusted to an optical density at 280 nm of 0.5. This corresponded to a concentration of 9 × 107 cells ml−1, which was the influent bacterial concentration used for column loading.

In order to reduce the concentration of indigenous bacteria in suspensions of Tetrahymena sp., 40-ml culture samples were centrifuged for 10 min at 8,000 × g. The supernatants were removed, and the pellets were each carefully overlaid with 3 ml of PBS1. Within 3 h, a considerable fraction of the Tetrahymena sp. cells swam from the pellets into the supernatants and simultaneously emptied their food vacuoles. The supernatants were pooled, the protozoans were counted with a Buerker counting chamber (Faust AG, Schaffhausen, Switzerland), and the suspension was diluted with PBS1 to a final density of 20,000 cells ml−1. This procedure reduced the concentration of indigenous bacteria to less than 4 × 107 cells ml−1. The suspensions of Tetrahymena sp. were used for grazing experiments within 2 to 3 h.

Adhesion of bacteria.

Cells of P. putida mt2 were attached to glass beads by the method of Rijnaarts et al. (31), which has been shown to result in nearly uniform distribution of bacteria. Briefly, water-filled columns (length, 10 cm; inside diameter, 1 cm), each with a glass frit at the lower end, were filled with glass beads (diameter, 0.45 to 0.50 mm). The total pore volume, 2.7 ml (corresponding to a porosity of 0.34), was determined gravimetrically. Suspensions of P. putida mt2 cells were added to the vertical downflow columns with a peristaltic pump (Ismatec, Glattbrugg, Switzerland) at a hydraulic flow rate of 73 ± 5 cm h−1 (0.33 ml min−1). The total volume of each system, which included the pumping tube, the pore space, and a small tube at the outflow, was 3.9 ml. The residence time of the conservative tracer NaCl in the system was 12 min. During percolation of P. putida mt2 through the columns, the A280 of the influent and the A280 of the effluent were measured after 25, 40, and 60 min. The amount of attached cells was calculated from the difference between the A280 of the influent and the A280 of the effluent and the percolated volume. Percolation with the bacterial suspension was stopped when the desired number of attached cells, ca. 2 × 108 cells ml of pore volume−1, was reached, usually after 75 to 100 min. After suspended cells were removed by percolation with PBS1 for an additional 30 min, the cell density in the effluent was below the detection limit, which confirmed that irreversible adhesion of P. putida mt2 to the glass had occurred (31).

Assays to study protozoan grazing in columns.

A Tetrahymena sp. suspension was pumped into 35 columns, including 3 columns without bacteria, for 13 min. In the 32 columns containing bacteria, the infiltrating protozoans had a chance to feed on attached bacteria. Protozoans were transported for 3 min through the pumping tubes. Thus, the grazing times in the beds of the columns during infiltration ranged from 10 min for the protozoans entering first to 0 min for the protozoans entering last. To calculate average grazing rates, a mean grazing time of 5 min during infiltration was assumed.

Following the infiltration period, the columns were subjected to three different flow protocols. This allowed us to determine the influence of different flow periods and static conditions on the grazing rates. In five columns, the flow was continued immediately with PBS1 containing no protozoans. Three effluent fractions were obtained; these fractions contained the protozoans leaving the columns 0 to 17, 17 to 28, and 28 to 31 min after end of the infiltration period. The first and third fractions (designated samples c1 and d1, respectively) (Table 1) were used to determine grazing rates. In 16 columns (including the 3 columns without bacteria) the flow was stopped for 10 min. Five of these columns were immediately sacrificed by emptying their contents into flasks containing 2.7 ml of fixation buffer (see below) and the protozoans designated sample b2. Percolation of the remaining 11 columns was continued with cell-free PBS1. Effluent samples were obtained at 3.7-min intervals for 22 min after percolation was started again. The second and sixth samples were used to determine grazing rates; these samples were designated samples c2 and d2, respectively. In 14 columns, the flow was interrupted for 30 min, and then 7 of the columns were sacrificed (sample b3). Percolation of the remaining seven columns was continued with cell-free PBS1. Effluent samples were collected at 3.7-min intervals for 22 min after percolation was started again. The second and sixth samples were used to determine grazing rates; these samples were designated samples c3 and d3, respectively. The grazing experiments performed with all three flow modes were stopped after elution by sacrificing the columns and pouring their contents into small flasks (samples e1, e2, and e3). Protozoans from sacrificed columns were recovered by gently shaking the flasks and removing 2-ml-subsamples. Preliminary experiments showed that all fixed protozoans were recovered by this procedure. All samples were fixed immediately with an equal volume of fixation buffer (4.4% [wt/vol] formaldehyde and 150 μl of 1 M NaOH per liter in buffer containing [per liter] 7.60 g of NaCl, 1.25 g of Na2HPO4, and 0.41 g of NaH2PO4 [PBS2]). Two-milliliter portions were then placed in Eppendorf vials and stored at 4°C overnight. The protozoan densities of all samples were determined with a Nageotte counting chamber (Faust AG).

TABLE 1.

Grazing rates and vacuole formation for Tetrahymena sp. preying on suspended or attached bacteria

| Sample typea | Sample | Length of grazing periods (min)b

|

No. of replicates

|

All recovered individuals

|

Active grazers onlyc

|

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| t1 | t2 | t3 | ttotal | Columns or batches | Individuals | Grazing rate (no. of bacteria individual−1 h−1) | Vacuole vol (μm3 individual−1) | No. of vacuoles | Grazing rate (no. of bacteria individual−1 h−1) | Vacuole vol (μm3 individual−1) | No. of vacuoles | Fraction of active grazers (%) | ||

| a | a1 | 0 | 5 | 154 | 13 ± 24 | 1.1 ± 1.7 | 27 ± 28 | 2.4 ± 1.7 | 48 | |||||

| a2 | 10 | 8 | 113 | 3,045 | 370 ± 375 | 5.1 ± 5.7 | 4,575 | 557 ± 329 | 6.1 ± 3.3 | 66 | ||||

| a3 | 30 | 3 | 81 | 1,382 | 505 ± 376 | 10.5 ± 12.2 | 1,823 | 665 ± 286 | 9.4 ± 3.2 | 75 | ||||

| a4 | 60 | 5 | 110 | 618 | 451 ± 449 | 7.4 ± 5.9 | 861 | 629 ± 411 | 10.2 ± 4.4 | 72 | ||||

| b | b2 | 5 | 10 | 0 | 15 | 5 | 110 | 880 | 161 ± 273 | 2.6 ± 3.4 | 1,641 | 299 ± 313 | 4.8 ± 3.2 | 54 |

| b3 | 5 | 30 | 0 | 35 | 7 | 140 | 648 | 276 ± 378 | 4.7 ± 4.5 | 986 | 420 ± 396 | 7.1 ± 3.7 | 66 | |

| c | c1 | 5 | 0 | 8 | 135 | 5 | 80 | 29 | 5 ± 25 | 1.3 ± 5.1 | 197 | 31 ± 60 | 2.3 ± 0.3 | 15 |

| c2 | 5 | 10 | 5 | 20 | 8 | 159 | 19 | 5 ± 21 | 0.2 ± 0.7 | 118 | 29 ± 45 | 1.5 ± 1.1 | 16 | |

| c3 | 5 | 30 | 5 | 40 | 7 | 144 | 17 | 8 ± 39 | 0.3 ± 0.9 | 96 | 47 ± 83 | 1.9 ± 1.5 | 18 | |

| d | d1 | 5 | 0 | 30 | 35 | 5 | 49 | 165 | 70 ± 146 | 1.4 ± 2.4 | 426 | 181 ± 189 | 3.8 ± 2.4 | 39 |

| d2 | 5 | 10 | 21 | 36 | 6 | 93 | 337 | 148 ± 239 | 2.9 ± 4.7 | 729 | 319 ± 262 | 6.3 ± 5.1 | 46 | |

| d3 | 5 | 30 | 21 | 56 | 5 | 53 | 228 | 155 ± 197 | 4.1 ± 4.9 | 447 | 305 ± 173 | 8.1 ± 3.8 | 51 | |

| e | e1 | 5 | 0 | 31 | 36 | 5 | 27 | 354 | 155 ± 168 | 5.8 ± 8.7 | 598 | 262 ± 139 | 8.5 ± 9.3 | 59 |

| e2 | 5 | 10 | 22 | 37 | 7 | 84 | 888 | 400 ± 407 | 5.3 ± 4.2 | 1,243 | 559 ± 377 | 7.4 ± 3.0 | 71 | |

| e3 | 5 | 30 | 22 | 57 | 7 | 126 | 317 | 219 ± 231 | 6.0 ± 4.8 | 407 | 282 ± 226 | 7.7 ± 4.0 | 78 | |

Sample types were distinguished as follows: sample type a, protozoans feeding on suspended bacteria in batch systems; sample type b, protozoans recovered from sacrificed columns without elution; sample type c, protozoans that eluted immediately; sample type d, protozoans with retarded elution; sample type e, protozoans retained in eluted columns.

The total grazing time in a column (ttotal) included an infiltration period (t1), a no-flow period (t2), and a mean elution period (t3).

Active grazers were defined as individuals which contained at least one food vacuole.

Assay to study protozoan grazing in bacterial suspensions.

In addition to the column experiments, grazing also was investigated in batch experiments. Six-milliliter portions of the suspension of Tetrahymena sp. used in the column experiments were transferred into glass tubes. At the same time that grazing was started in the columns, 100- to 300-μl portions of the washed P. putida mt2 concentrate were added to a final concentration of ca. 2.0 × 108 cells ml−1. The tubes were manually shaken every 5 min to keep the cells in suspension. Samples (0.8 ml) were taken at zero time and after 10, 30, and 60 min (samples a1 to a4) and occasionally 120 min after the bacteria were added. They were fixed with the same volume of 4.4% fixation buffer and stored before they were used for in situ hybridization.

In situ hybridization.

Two milliliters of each sample of protozoans was washed twice in PBS2 by using a table centrifuge (10 min, 16,000 × g). The pellets were each resuspended in 0.3 ml of PBS2, an equal volume of ethanol was added, and the samples were stored at −20°C. For in situ hybridization of ingested bacteria, the eubacterial 5′-fluorescein-linked oligonucleotide probe EUB 338 (MWG Biotech, Ebersberg, Germany) was used. Thawed samples were centrifuged and resuspended in 20 to 500 μl of PBS2, depending on the protozoan density. Drops (10 μl) were placed on agarose-coated glass slides. The slides were air dried for 30 min at 45°C to attach the protozoans, and then the residual agarose was removed by treatment for 9 min with increasing aqueous concentrations of ethanol (50, 70, and 100%). Hybridization was performed at 45°C for at least 2 h in 10 μl of buffer (0.9 M NaCl, 20 mM Tris-HCl, 0.05% sodium dodecyl sulfate, 30% formamide) containing an oligonucleotide probe at a concentration of 67 ng liter−1. The hybridization chambers used were plastic vials that contained a piece of absorbent paper soaked with hybridization buffer to prevent drying of the slides. The hybridization mixture was removed, and sample plots were covered for 20 min at 45°C with another 10 μl of hybridization buffer and for 10 min at 4°C with distilled water. In some cases the samples were counterstained for 10 min with 0.0001% (wt/vol) DAPI (4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole-dihydrochloride). Finally, the samples were treated with 8 μl of antifading solution (Citifluor Ltd., London, United Kingdom).

The protozoans were observed with an Olympus model BH 2 microscope at a magnification of ×1,250 by using an interference filter set at a wavelength of 495 nm (type BP 495 exciter filter; type 515 IF barrier filter; type DM505 dichroic mirror; Olympus AG).

Calculation of grazing rates.

Counting single bacteria inside the food vacuoles was not feasible since the bacteria were too densely packed. Therefore, bacterial numbers were inferred from the vacuole volumes. The diameters of the generally spherical vacuoles were measured with a calibrated grid projected onto a slide. Up to 30 protozoans from each sample were analyzed in this way. Grazing rates (q) (in number of bacteria per individual per hour) were calculated by using the ratio of the total food vacuole volume of a grazer (Vp) (in cubic micrometers) to the volume of a bacterial cell (Vb) (in cubic micrometers) as q = Vp/Vb (t1 + t2 + t3), where the grazing time was divided into the infiltrating period (t1) (5 min), the no-flow period (t2), and the elution period (t3). Grazing rates were calculated for all recovered protozoans and were calculated separately for active grazers (i.e., the individuals which contained at least one food vacuole) in order to account for the grazing activities of the population and of the active subpopulation, respectively.

The total glass surface area available for bacterial attachment was the sum of the inner mantle area of the column and the surface area of the glass collectors. The latter was the specific surface area of the glass (49 cm2 g−1) multiplied by the mass of glass per column (31). The ratio of available glass surface area to pore space was 250 cm2 ml−1. A bacterial concentration of 2.0 × 108 cells ml of pore space−1 thus corresponded to 8,000 cells mm−2 or 125 μm2 cell−1, and a protozoan concentration of 20,000 cells ml of pore space−1 corresponded to about 1 individual mm−2.

RESULTS

Percolation of bacteria and protozoans.

After the initial breakthrough, the effluent concentrations of P. putida mt2 reached stable values corresponding to 81% ± 6% (mean ± standard deviation) of the influent concentration. The bacterial concentrations, after individual columns were loaded, ranged from 1.28 × 108 to 2.55 × 108 cells ml of pore space−1. After the initial breakthrough, the protozoan densities in the effluents of columns with attached bacteria ranged from 7 to 13% of the influent concentrations, regardless of whether the flow had been stopped for 10 or 30 min. A total of 19% ± 16% of all protozoans were eluted during the experiments. When the eluted columns were sacrificed, another 46% ± 18% of the retained protozoans were recovered, whereas 36% ± 25% of the protozoans were lost. The total recovery rate, 64% ± 24%, equals the recovery rate of 64% ± 22% obtained for the protozoans from the columns which were sacrificed before elution. This indicates that the loss of protozoans occurred during infiltration, possibly in the peristaltic pump. In bacterium-free columns, the level of retention of protozoans was much lower. While 50% ± 8% of the individuals appeared in the effluent, only 12% ± 3% were retained in the columns and 38% ± 13% were lost.

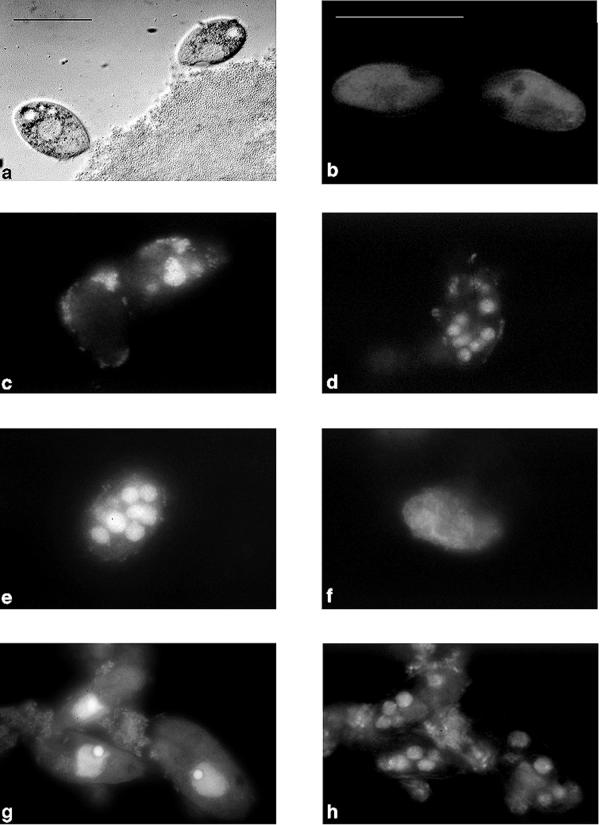

Visualization of ingested bacteria.

Food vacuoles inside Tetrahymena sp. were clearly visible after hybridization of the ingested bacteria (Fig. 1). The number and volume of the spherical vacuoles increased with grazing time. The diameters of individual vacuoles ranged from 1.5 to 8.0 μm. Intact shapes of ingested bacteria could still be observed more than 35 min after ingestion. After 2 h of grazing, fluorescent label was visible inside the predator cytoplasm, indicating that egestion of the vacuole contents had occurred. Staining with DAPI resulted in weak blue fluorescence of the ingested bacteria.

FIG. 1.

In situ hybridization of oligonucleotide probe EUB 338 with P. putida subjected to predation by Tetrahymena sp. (a) Grazing ciliates (bright light). (b) Cells before predation (green excitation). (c through f) Cells 5, 30, 60, and 250 min, respectively, after predation of a suspension containing 5 × 108 bacteria ml−1. (g) DAPI staining (blue excitation). (h) Same microscopic field as microscopic field in panel g but with green excitation of EUB 338. Bars = 30 μm. Panels b through h are shown at the same magnification. Adobe Photoshop was used to capture the images.

Grazing activities.

Table 1 summarizes the grazing activities of Tetrahymena sp. on suspended and glass-associated bacteria. At the beginning of the experiments, the grazers contained almost no ingested bacteria (Table 1, sample a1). Indigenous bacteria were not ingested, as shown by the controls without added food. The highest grazing rate was observed after 10 min of predation in batches containing suspended bacteria (sample a2). Subsequently, the grazing rate declined rapidly, as shown by the insignificantly larger vacuole volumes after 30 and 60 min of grazing (samples a3 and a4). The fraction of active grazers increased only slightly from 66% after 10 min to 72% after 60 min. In order to directly compare a complete Tetrahymena sp. population feeding on suspended cells, some columns were sacrificed before elution (samples b1 and b2). The fractions of grazing individuals in the column system were slightly lower than the fraction of grazing individuals in the batch system, and the absolute grazing rates were considerably reduced when the prey was glass associated prey (compare samples b2 and a3).

Clearly different grazing rates were observed with the protozoans that were immediately eluted with the flowing liquid (samples c1 through c3), the protozoans that passed through the columns with a delay (samples d1 through d3), and the protozoans that remained in the columns even after prolonged elution (samples e1 through e3). Very low grazing rates and fractions of active grazers of only 15 to 18% were obtained with the conservatively transported protozoans, and the intermittent no-flow period (samples c1 through c3) did not have much influence. The mean number of vacuoles and the total vacuole volumes of immediately eluted active grazers were similar to those of individuals in the column influents (compare samples c1 through c3 with sample a1). The fraction of active grazers was considerably smaller than the fraction in the column influents, indicating that selective retention of feeding organisms occurred. Clearly higher grazing rates were observed for protozoans which were transported with a delay. These organisms grazed for 35 min during continuous percolation (sample d1), but grazed more efficiently when static conditions were provided for 10 min (sample d2). When the flow was stopped for 30 min (sample d3), the total vacuole volume of active grazers did not increase further, and the fraction of active grazers stayed nearly constant.

The grazing rates and the numbers of vacuoles of retained organisms increased considerably when a no-flow period of 10 min was used (compare samples e1 and e2). A prolonged no-flow period did not result in further increases. The mean vacuole volumes even decreased when the no-flow period was extended to 30 min before elution and protozoan recovery (sample e3). This may have been due to digestion that led to a reduction in the vacuole volume. Generally, the fraction of actively grazing individuals was as high as the fraction obtained with suspended prey (compare samples e1 through e3 with samples a1 through a4). It should be noted, however, that the percentages of active grazers in the column systems refer to only the ca. 65% of the individuals which could be recovered.

DISCUSSION

In situ hybridization.

Postingestion in situ hybridization is a powerful method for monitoring ciliate predation on viable bacteria. We have demonstrated that this method is valuable in predation experiments performed with attached bacteria, since it overcomes a possible drawback of prelabeling of prey, the influence of the labeling procedure on bacterial viability, and adhesion behavior. In situ hybridization with specific oligonucleotide probes would offer the additional possibility of investigating the prey preference of predators. Binding of fluorescently labeled oligonucleotides to bacterial target rRNA has been used previously to characterize endosymbionts in anaerobic ciliates (1), to examine natural assemblages of protists (20), and to monitor flagellate grazing on bacterial suspensions (30) or biofilms (16).

Direct counting of incorporated bacteria was not feasible since food vacuoles are three-dimensional, densely packed organelles. We therefore decided to infer grazing rates from vacuole volumes. It is obvious that premature processing of vacuoles could lead to underestimates of ingested bacteria. In the present experiments, the shapes of intact single bacteria could still be distinguished inside the food vacuoles after 35 min of grazing, which is the duration of continuous uptake of bacteria by Tetrahymena sp. (10, 25). Typically, distinct phases of prey ingestion, digestion, and defecation can be observed (34). After 1 h of grazing, the vacuole number became constant and the vacuole volumes decreased, which indicated that digestion was beginning. This was accompanied by the appearance of fluorescent label in the ciliate cytoplasm. Hence, vacuole volume appears to be an adequate measure of the number of ingested bacteria in grazing experiments less than 1 h long.

Availability of attached bacteria.

The attached mode of living can protect bacteria from predation (5, 11), but may also support grazers with a preference for attached prey (5, 37, 38). Feeding on attached bacteria is typical for tectic protozoans (28), but has been quantified only for flagellates (38). The interstitial grazing rates observed in this study are in the upper range of the rates found with ciliates and fluorescently labeled bacteria in natural porous habitats (8, 17). For protozoans with considerably smaller body sizes than Tetrahymena sp., grazing rates on attached bacteria were 1 order of magnitude lower (38). Community ingestion rates of up to 3,000 bacteria individual−1 h−1 in river sediments have been calculated on the basis of protozoan growth and reductions in bacterial numbers (3). Our grazing rates of up to 880 attached bacteria individual−1 h−1 are the first values obtained for a clearly defined porous system. Our maximum grazing rate corresponds to a cleared collector surface of 3,420 μm2 individual−1 min−1 when a uniform distribution of bacteria is assumed. This is an area slightly larger than the cell surface of the ciliate. Tetrahymena sp. lacks characteristics of surface-associated tectic protozoans and seems to be adapted to a pelagic environment. However, it is able to feed on attached prey, although less efficiently than on suspended prey.

Transport and grazing behavior of Tetrahymena sp. in a porous medium.

Water flow is an important factor for protozoan predation in porous systems (13). Presumably, grazers reach sites with elevated numbers of bacteria by passive transport. For them it is crucial to avoid washout or damage (28). The loss of about one-third of all ciliates during infiltration indicates that these organisms are susceptible to destruction. Most of the surviving individuals were retained in percolated columns. Since the cell diameter of Tetrahymena sp. was about five times less than the neck diameter of the pores (∼100 μm), direct entrapment is unlikely. Immobilization and retardation of transport of groundwater protozoans have been attributed to the tendency of the protozoans to adhere to surfaces (13). Our finding that more individuals were retained in columns with attached bacteria than in columns without attached bacteria suggests that the transport behavior was influenced by the interaction with adhered prey. Active feeding perhaps prevented the ciliates from leaving the hydrodynamic boundary layer where the flow velocity was reduced close to the collector surface. This would at least in part explain the increased grazing rates of ciliates that passed through the columns with delays or were retained in pores. Feeding experiments performed with suspended prey showed that the Tetrahymena population was divided into grazers and nongrazers. It seems that the active predators interacted with bacteria on the collector surface and were retained, whereas no retention occurred with nongrazers. A polymorphous life cycle has been reported for Tetrahymena sp.; this life cycle includes passive, nonfeeding cells in the predivision stage, the so-called tomonts (39). These cells may account for the subpopulation that was transported conservatively. Higher grazing rates were observed during no-flow periods. Presumably, the uptake of bacteria was disturbed by the water flow even in the relatively quiescent hydrodynamic boundary layer. According to colloid filtration theory, enhanced flow velocity in a porous system reduces the collision frequency of transported particles with collector surfaces (12, 22). High flow velocities may therefore decrease the probability that a protozoan cell will contact its attached prey, the step crucial for initiation of grazing along the surface. The active mobility of Tetrahymena sp. is possibly not strong enough to completely overcome the hydrodynamic influence.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Chris Robinson for helpful comments on the manuscript and Rainer Zah for help with Adobe Photoshop software.

REFERENCES

- 1.Amann R, Springer N, Ludwig W, Görtz H-D, Schleifer K-H. Identification in situ and phylogeny of uncultured bacterial endosymbionts. Nature. 1991;351:161–164. doi: 10.1038/351161a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Berninger U-G, Finlay B J, Kuuppo-Leinikki P. Protozoan control of bacterial abundances in freshwater. Limnol Oceanogr. 1991;36:139–147. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bott T L, Kaplan L A. Potential for protozoan grazing of bacteria in streambed sediments. J N Am Benthol Soc. 1990;9:336–345. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brading M G, Jass J, Lappin-Scott H M. Dynamics of bacterial biofilm formation. In: Lappin-Scott H M, Costerton J W, editors. Microbial biofilms. Baltimore, Md: University Press; 1995. pp. 46–63. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Caron D A. Grazing of attached bacteria by heterotrophic microflagellates. Microb Ecol. 1987;13:203–218. doi: 10.1007/BF02024998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.DeLeo P C, Baveye P. Factors affecting predation of bacteria clogging laboratory microcosms. Geomicrobiol J. 1997;14:127–149. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Eisenmann H, Traunspurger W, Meyer E I. A new device to extract sediment cages colonized by microfauna from coarse gravel river sediments. Arch Hydrobiol. 1997;139:547–561. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Epstein S S, Shiaris M P. Rates of microbenthic and meiobenthic bacterivory in a temperate muddy tidal flat community. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1992;58:2426–2431. doi: 10.1128/aem.58.8.2426-2431.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fauré-Fremiet E. Morphologie comparéé et systématique des ciliés. Bull Soc Zool Fr. 1950;75:109–122. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fok A K, Shokley B U. Processing of digestive vacuoles in Tetrahymena and the effects of dichloroisoproterenol. J Protozool. 1985;32:6–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1550-7408.1985.tb03004.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Güde H. Grazing by protozoa as selection factor for activated sludge bacteria. Microb Ecol. 1979;5:225–237. doi: 10.1007/BF02013529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Harvey R W. Parameters involved in modeling movement of bacteria in groundwater. In: Hurst C J, editor. Modeling the environmental fate of microorganisms. Washington, D.C: American Society for Microbiology; 1991. pp. 89–114. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Harvey R W, Kinner N E, Bunn A, MacDonald D, Metge D. Transport behavior of groundwater protozoa and protozoan-sized microspheres in sandy aquifer sediments. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1995;61:209–217. doi: 10.1128/aem.61.1.209-217.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hondeveld B J M, Bak R P M, van Duyl F C. Bacterivory by heterotrophic nanoflagellates in marine sediments measured by uptake of fluorescently labeled bacteria. Mar Ecol Prog Ser. 1992;89:63–71. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jucker B A, Harms H, Zehnder A J B. Adhesion of the positively charged bacterium Stenotrophomonas (Xanthomonas) maltophila 70401 to glass and Teflon. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:5472–5479. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.18.5472-5479.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kalmbach S, Manz W, Szewzyk U. Dynamics of biofilm formation in drinking water: phylogenetic affiliation and metabolic potential of single cells assessed by formazan reduction and in situ hybridization. FEMS Microb Ecol. 1997;22:265–279. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kemp P F. Bacterivory by benthic ciliates: significance as a carbon source and impact on sediment bacteria. Mar Ecol Prog Ser. 1988;49:163–169. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kemp P F. The fate of benthic bacterial production. Rev Aquat Sci. 1990;2:109–124. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kuikman P J, Jansen A G, van Veen J A, Zehnder A J B. Protozoan predation and the turnover of soil organic carbon and nitrogen in the presence of plants. Biol Fertil Soils. 1990;10:22–28. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lim E L, Caron D A, Delong E F. Development and field application of a quantitative method for examining natural assemblages of protists with oligonucleotide probes. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1996;62:1416–1423. doi: 10.1128/aem.62.4.1416-1423.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Madsen E L, Sinclair J L, Ghiorse W G. In situ biodegradation: microbial patterns in a contaminated aquifer. Science. 1991;252:830–833. doi: 10.1126/science.2028258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Martin R E, Bouwer E J, Hanna L M. Application of clean-bed filtration theory to bacterial deposition in porous media. Environ Sci Technol. 1992;26:1053–1058. [Google Scholar]

- 23.McManus G B. On the use of surrogate food particles to measure protistan ingestion. Limnol Oceanogr. 1991;36:613–617. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Monger B C, Landry M R. Direct-interception feeding by marine zooflagellates: the importance of surface and hydrodynamic forces. Mar Ecol Prog Ser. 1990;65:123–140. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nilsson J R. Phagotrophy in Tetrahymena. In: Levandowsky M, Hutner S H, editors. Biochemistry and physiology of protozoa. Vol. 2. New York, N.Y: Academic Press, Inc.; 1979. pp. 339–379. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Novitsky J A. Protozoa abundance, growth, and bacterivory in the water column, on sedimenting particles, and in the sediment of Halifax Harbor. Can J Microbiol. 1990;36:859–863. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nygaard K, Børsheim K Y, Thingstad T F. Grazing rates on bacteria by marine heterotrophic microflagellates compared to uptake rates of bacteria-sized monodisperse fluorescent latex beads. Mar Ecol Prog Ser. 1988;44:159–165. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Patterson D J, Larsen J, Corliss J O. The ecology of heterotrophic flagellates and ciliates living in marine sediments. Prog Protistol. 1989;3:185–277. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pedersen K. Factors regulating microbial biofilm development in a system with slowly flowing seawater. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1982;44:1196–1204. doi: 10.1128/aem.44.5.1196-1204.1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pernthaler J, Sattler B, Simek K, Schwarzenbacher A, Psenner R. Contrasting bacterial strategies to coexist with a flagellate predator in an experimental microbial assemblage. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1997;63:596–601. doi: 10.1128/aem.63.2.596-601.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rijnaarts H H M, Norde W, Bouwer E J, Lyklema J, Zehnder A J B. Bacterial adhesion under static and dynamic conditions. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1993;59:3255–3265. doi: 10.1128/aem.59.10.3255-3265.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rijnaarts H H M, Norde W, Bouwer E J, Lyklema J, Zehnder A J B. Reversibility and mechanism of bacterial adhesion. Colloids Surf B Biointerf. 1995;4:5–22. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sherr B F, Sherr E B. Role of heterotrophic protozoa in carbon and energy flow in aquatic ecosystems. In: Klug M J, Reddy C A, editors. Current perspectives in microbial ecology. Washington, D.C: American Society for Microbiology; 1984. pp. 412–423. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sherr B F, Sherr E B, Rassoulzadegan F. Rates of digestion of bacteria by marine phagotrophic protozoa: temperature dependence. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1988;54:1091–1095. doi: 10.1128/aem.54.5.1091-1095.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sherr B F, Sherr E B, Fallon R D. Use of monodispersed, fluorescently labeled bacteria to estimate in situ protozoan bacterivory. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1987;53:958–965. doi: 10.1128/aem.53.5.958-965.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shimeta J, Jumars P A, Lessard E J. Influences of turbulence on suspension feeding by planktonic protozoa; experiments in laminar shear fields. Limnol Oceanogr. 1995;40:845–859. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sibbald M J, Albright L J. Aggregated and free bacteria as food sources for heterotrophic microflagellates. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1988;54:613–616. doi: 10.1128/aem.54.2.613-616.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Starink M, Krylova I N, Gilissen M-J, Bak R P M, Cappenberg T E. Rates of benthic protozoan grazing on free and attached sediment bacteria measured with fluorescently stained sediment. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1994;60:2259–2264. doi: 10.1128/aem.60.7.2259-2264.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Swift S T, Najita I Y, Ohtaguchi K, Fredrickson A G. Some physiological aspects of the autecology of the suspension-feeding protozoan Tetrahymena pyriformis. Microb Ecol. 1982;8:201–215. doi: 10.1007/BF02011425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Vrba J, Simek K, Nedoma J, Hartman P. 4-Methylumbelliferyl-β-N-acetylglucosaminide hydrolysis by a high-affinity enzyme, a putative marker of protozoan bacterivory. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1993;59:3091–3101. doi: 10.1128/aem.59.9.3091-3101.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wikner J. Grazing rate of bacterioplankton via turnover of genetically marked minicells. In: Kemp P F, Sherr B F, Sherr E B, Cole J J, editors. Handbook of methods in aquatic microbial ecology. Boca Raton, Fla: Lewis Publishers; 1993. pp. 703–714. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Williams P A, Worsey M J. Ubiquity of plasmids in coding for toluene and xylene metabolism in soil bacteria: evidence for the existence of a new TOL plasmid. J Bacteriol. 1976;125:818–828. doi: 10.1128/jb.125.3.818-828.1976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wright D A, Killham K, Glover L A, Prosser J I. Role of pore size location in determining bacterial activity during predation by protozoa in soil. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1995;61:3537–3543. doi: 10.1128/aem.61.10.3537-3543.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zubkov M V, Sleigh M A. Ingestion and assimilation by marine protists fed on bacteria labeled with radioactive thymidine and leucine estimated without separating predator and prey. Microb Ecol. 1995;30:157–170. doi: 10.1007/BF00172571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]