Abstract

A 6.0-kb SalI DNA fragment containing an entire rRNA operon (rrnB) was cloned from a cosmid gene bank of the phytopathogenic strain Rhodococcus fascians D188. The nucleotide sequence of the 6-kb fragment was determined and had the organization 16S rRNA-spacer-23S rRNA-spacer-5S rRNA without tRNA-encoding genes in the spacer regions. The 5′ and 3′ ends of the mature 16S, 23S, and 5S rRNAs were determined by alignment with the rrn operons of Bacillus subtilis and other gram-positive bacteria. Four copies of the rrn operons were identified by hybridization with an rrnB probe in R. fascians type strain ATCC 12974 and in the virulent strain R. fascians D188. However, another isolate, CECT 3001 (= NRRL B15096), also classified as R. fascians, produced five rrn-hybridizing bands. An integrative vector containing a 2.5-kb DNA fragment internal to rrnB was constructed for targeted integration of exogenous genes at the rrn loci. Transformants carrying the exogenous chloramphenicol resistance gene (cmr) integrated in different rrn operons were obtained. These transformants had normal growth rates in complex medium and minimal medium and were fully stable for the integrated marker.

Rhodococcus fascians is a gram-positive bacterium with a high G+C content belonging to the group of lower actinomycetes (14) closely related to corynebacteria. Strains of this species are of interest because they are phytopathogenic (32), causing the formation of galls on dicotyledonous plants (30) and malformations of bulbs of monocotyledonous plants (24).

The molecular genetics of nonpathogenic corynebacteria have received considerable attention (for reviews see references 23 and 29), but there are no advanced recombinant DNA tools for studying molecular genetics of plant-pathogenic bacteria such as R. fascians. Several plasmids, including circular and high-molecular-weight linear plasmids, are present in strains of R. fascians (7, 11). Conjugative plasmids carrying genes determining resistance to cadmium salts (10) or chloramphenicol (12) have been characterized. One of these plasmids, pRF2, was used to develop bifunctional vectors that also replicate in Escherichia coli (12). By using these vectors, transformation of R. fascians strains has been obtained by electroporation (9, 11).

Some genes associated with phytopathogenicity were found in a 200-kb linear plasmid in R. fascians D188 (7, 8). Chromosomal genes also appear to be required to produce plant disease (7). In order to clone and study additional genetic determinants involved in plant pathogenicity, there is a need to develop a system for chromosomal integration and expression of homologous or heterologous DNA in well-characterized dispensable sites of the R. fascians chromosome. As part of an effort in this direction, we characterized the nucleotide sequence and organization of an rRNA operon (rrnB) of R. fascians D188. Although the 5S rRNA gene of this species (21) and the 16S rRNA gene were amplified by PCR and used in phylogenetic analyses of gram-positive bacteria previously (26), the complete organization of the rrn operons and the number of rrn loci were not established.

Gene targeting is a useful strategy for introducing exogenous genes into specific chromosomal regions. Due to their repetitive nature, rRNA operons are very suitable targets for chromosomal integration of foreign DNA fragments without modification of growth rates and viability characteristics (5). In this paper we describe the characterization of the rrnB locus and the use of rRNA-encoding regions of R. fascians D188 as target sites for integration and expression of the exogenous gene cmr, a gene conferring chloramphenicol resistance (12).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and plasmids.

The bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study are listed in Table 1. E. coli was grown at 37°C in Luria broth or on Luria agar. When appropriate, ampicillin (50 μg/ml) was added to the medium. R. fascians was grown at 28°C in tryptic soy broth, on tryptic soy agar, or in minimal salts thiamine medium (28). For selection of chloramphenicol-resistant transformants of R. fascians the antibiotic was used in the culture medium at a final concentration of 25 μg/ml.

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study

| Strain or plasmid | Characteristics | Reference or sourcea |

|---|---|---|

| R. fascians strains | ||

| D188 | Cdr, pFiD188, pD188 | 5 |

| D188::pIC44.B | pIC44 inserted in rrrB, Cdr Cmr | This study |

| D188.5 | Cds Strr Eryr, plasmid-free mutant | 5 |

| CECT 3001 (= NRRL B15096) | Cdr, pC120/pL650 | CECT |

| ATCC 12974 | Cdr, pFiD188-like plasmid | ATCC |

| E. coli strains | ||

| DH1 | recA1 endA1 hsdR17 (rk−mk+) supE44 λ− thi-1 gyrA relA1 | Stratagene |

| DH5α | F− φ80dlacZΔM15 Δ(lacZYA-argF) U169 recA1 endA1 hsdR17 (rk−mk+) supE44 λ− thi-1 gyrA relA1 | 16 |

| WK6 | Δ(lac-proAB) galE strA mutS215::Tn10 F′ lac4IqZ ΔM15 proA+B+ | R. Zell |

| Plasmids | ||

| pHC79 | Cosmid derived from pBR322, Apr Tetr | 17 |

| Bluescript SK+ | Apr, ColE1 origin | Stratagene |

| pSKCm | Bluescript SK+ derivative, Cmr | This study |

| pRF30 | Apr Cmr, ColE1 origin, R. fascians plasmid replication origin | 11 |

| pRH2 | Bluescript SK+ with 2.7-kb HindIII insert containing R. fascians 16S and 23S rRNA sequences | This study |

| pIC44 | Apr Cmr, ColE1 origin, parts of R. fascians 16S and 23S rRNA sequences | This study |

CECT, Spanish Type Culture Collection; ATCC, American Type Culture Collection.

Plasmid and total DNA purification.

Small-scale preparations of E. coli plasmids were obtained as described by Birnboim and Doly (3). Recombinant cosmids were extracted by the alkaline lysis method, as described by Maniatis et al. (22). Total DNA was prepared from 100-ml overnight cultures. Cells were collected by centrifugation and resuspended in 5 ml of TES buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8.0], 25 mM EDTA, 10.3% sucrose) and treated for 2 h at 37°C with lysozyme (0.25 mg/ml). Then, 1 volume of a solution containing 10% Sarkosyl and 0.5 M EDTA was added slowly. The lysate was treated with RNase (100 μg/ml) for 20 min at 37°C, followed by digestion with proteinase K (50 μg/ml) for 1 h at 50°C. After phenol extraction, DNA was precipitated from the aqueous phase with ethanol and resuspended in TE (10 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8.0], 1 mM EDTA).

Cosmid library construction.

Total DNA of R. fascians D188 was partially digested with Sau3AI. DNA fragments with an average size of 40 to 50 kb were collected after centrifugation in a 10 to 50% sucrose gradient, extracted with phenol, and precipitated with ethanol. A 3-μg portion of this DNA was ligated to a 10-fold molar excess of cosmid pHC79 (3 μg) (17) that had been linearized with BamHI and treated with alkaline phosphatase to prevent self-ligation. The ligation mixture was packaged into λ phage particles in vitro by using a Gigapack II commercial kit (Stratagene), and cosmid-containing phage particles were used to transduce E. coli DH1 to ampicillin resistance (50 μg/ml), which yielded 6 × 105 Apr transductants per μg of R. fascians DNA. One thousand transductant colonies were transferred into 100 μl of Luria broth in 96-well microtiter plates and grown overnight at 37°C. Glycerol was added to a final concentration of 20%, and the clones were stored at −70°C.

DNA manipulations.

Restriction enzymes, T4 DNA ligase, and calf intestinal phosphatase were obtained from Boehringer Mannheim and were used as recommended by the manufacturer. Restriction-generated fragments were separated in 0.7 to 1% agarose gels depending on their sizes and were isolated and purified with a Geneclean kit (BIO-101).

Electroporation of R. fascians.

For electroporation, exponentially growing cells of R. fascians were concentrated 50-fold in a 30% polyethylene glycol 1000 solution (9). Electroporation was performed with a Gene-Pulser apparatus (Bio-Rad) by using the conditions described by Desomer et al. (9). E. coli was transformed by standard procedures (16).

DNA hybridizations.

DNA fragments were transferred from agarose gels to nylon membranes (Amersham) by vacuum blotting. Probe labelling by the random priming method and hybridizations were performed with a digoxigenin kit from Boehringer Mannheim according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Sequence determination and analysis.

The nucleotide sequence was determined on both strands with an automated dideoxy sequencing system (A.L.F. DNA sequencer; Pharmacia). The sequences used in this work for comparative studies were obtained from the EMBL and GenBank data banks. Analyses were performed with the MEGALIGN program (DNAStar Inc., Madison, Wis.).

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The nucleotide sequence of the rrnB operon of R. fascians D188 has been deposited in the EMBL and GenBank databases under accession no. Y11196.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Cloning of R. fascians rrn operons.

A cosmid gene bank from R. fascians D188 was probed with a 2.7-kb HindIII DNA fragment of an rrn operon from Brevibacterium lactofermentum containing the entire sequence of the 16S rRNA gene and a small portion of the 23S rRNA gene (1). The rrn from Brevibacterium lactofermentum was used as a probe because a higher degree of similarity was expected between ribosomal DNA operons of R. fascians and Brevibacterium lactofermentum (both coryneform bacteria) than between operons of R. fascians and other gram-positive bacteria, such as Bacillus subtilis.

Ten positive hybridizing clones were identified by colony blotting. To identify small restriction fragments that gave positive hybridization, cosmid DNA was extracted and digested with several enzymes, and blots of the digests were hybridized with the same Brevibacterium lactofermentum rrn probe. By using this procedure a 6.0-kb SalI band and a 2.7-kb HindIII band were identified and subcloned in the E. coli vector pBluescript SK+. The resulting plasmids were designated pRS1 and pRH2, respectively. The 2.7-kb HindIII fragment was found to be internal to the 6.0-kb SalI fragment (Fig. 1A).

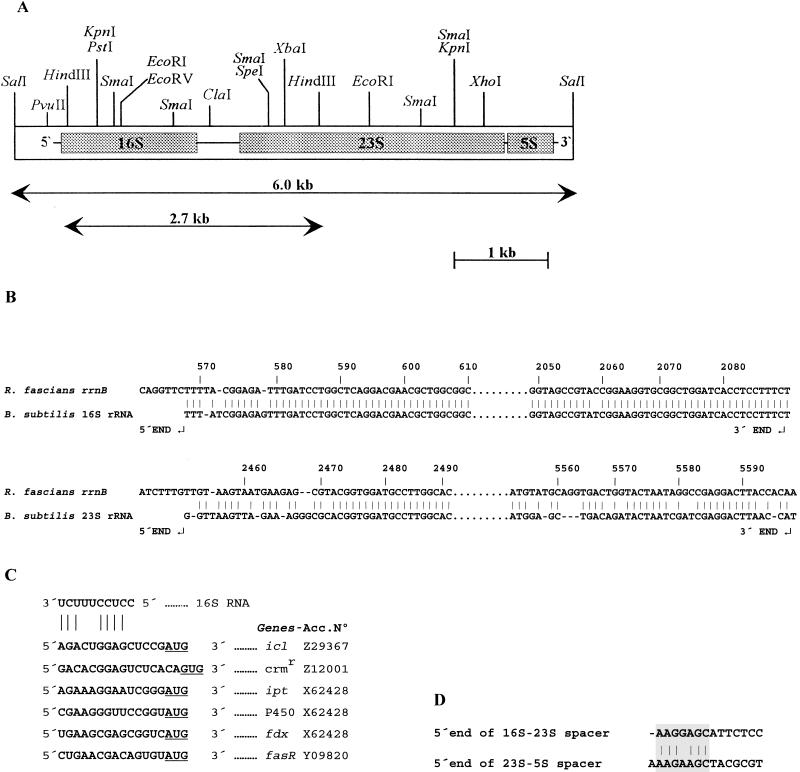

FIG. 1.

(A) Restriction map of a 6.0-kb R. fascians DNA fragment encoding the rrnB region. The 6.0-kb SalI and 2.7-kb HindIII fragments are indicated by arrows. The regions corresponding to the 16S, 23S, and 5S rRNAs are indicated by stippled boxes. (B) Alignment of the rrn gene of Bacillus subtilis with the corresponding regions of R. fascians encoding the 16S and 23S rRNAs. Note the strong conservation of the 5′ and 3′ regions. (C) Alignment of the 3′ end of the 16S rRNA gene of R. fascians with the regions upstream from the putative initiation codons of cloned genes from the same species. For each gene, pairing of at least four bases takes place. (D) Alignment of the first nucleotides of the R. fascians 16S rRNA-23S rRNA and 23S rRNA-5S rRNA spacers.

Nucleotide sequence and organization of the ribosomal DNA locus.

The 6.0-kb SalI insert of pRS1 was completely sequenced. In this fragment we found the previously reported R. fascians sequences encoding 16S and 5S rRNAs (accession no. X79186 and X15126, respectively). The presence of DNA encoding 23S rRNA was established by comparison with nucleotide sequences from Bacillus subtilis (accession no. K00637), E. coli (J01695), and Streptomyces lividans (M20148).

The rRNA genes in the 6.0-kb R. fascians DNA fragment were arranged in the order 16S rRNA-spacer-23S rRNA-spacer-5S rRNA (Fig. 1A). The spacer region between the 16S and 23S rRNA genes was 364 bp long, and the spacer region between the 23S and 5S rRNA genes was 134 bp long. No tRNA-like structures were identified in the spacer regions. The overall G+C content of the 6.0-kb fragment was 55.45 mol%, a value much lower than the average G+C content of the chromosomal DNA of R. fascians (64 mol%) (14). The G+C contents of the 16S rRNA-23S rRNA and 23S rRNA-5S rRNA spacers were 52.07 and 50.38 mol%, respectively.

The 5′ and 3′ ends of the mature 16S rRNA were assigned to nucleotides 568 and 2088, respectively (Fig. 1B), on the basis of an alignment with the homologous gene of Bacillus subtilis (15). The 5′ and 3′ ends of the 5S rRNA gene were located at nucleotides 5733 and 5853, and the total length of the 5S rRNA was 121 nucleotides. Upstream from the 5′ end of the 16S rRNA an RNase III cleavage site (AACUCAA) was found between nucleotides 377 and 383. From nucleotide 1444 to nucleotide 1456 the nucleotide signature for the high-G+C-content group (CUAAAACUCAAAG) is present. The base composition of the 3′ end of the 16S rRNA is consistent with the presence of an anti-Shine-Dalgarno (SD) sequence. As shown in Fig. 1C, there is good complementarity between the 3′ end of the 16S rRNA and regions located six to eight nucleotides upstream from the initiation codons AUG and GUG of several cloned R. fascians genes. The open reading frames analyzed correspond to the icl genes for isocitrate lyase (GenBank accession no. Z29367), a gene encoding a chloramphenicol resistance protein (Z12001), and a cluster of genes (ipt, P450, fdx) implicated in pathogenic traits (X62428). The number of bases involved in pairing ranged from four (fasR) to eight (ipt). The only exception was attE (accession no. Y09820), which encodes a protein of unknown function, is linked to the fasR gene, and did not show significant base pairing, suggesting that its ATG is not well-defined. The E. coli consensus Shine-Dalgarno sequence corresponded exactly to the SD sequence of the ipt gene.

Alignment with the homologous 23S rRNA gene of Bacillus subtilis allowed us to assign the 5′ and 3′ ends of the R. fascians 23S rRNA gene to nucleotides 2452 and 5598, respectively (Fig. 1B). The total length of the R. fascians DNA encoding the 23S rRNA is 3,147 bp, which is slightly greater than the values reported for E. coli (2,904 bp) (4), Bacillus subtilis (2,927 bp) (15), and Streptomyces griseus (3,120 bp) (19), and the G+C content of this DNA is 54.97 mol%. Between positions 4009 and 4120 there was an insertion that included a 107-bp sequence that is found in several gram-positive bacteria (27). This insertion within the central part of the 23S rRNA genes was found to be a phylogenetic marker for the gram-positive bacteria with high DNA G+C contents. This result indicates that R. fascians is phylogenetically related to corynebacteria and actinomycetes (27). As shown in Table 2, the 23S rRNA gene of R. fascians had a high percentage of nucleotides identical to the nucleotides in homologous genes of other gram-positive bacteria with high G+C contents, like Mycobacterium paratuberculosis (80.2% identical nucleotides), Mycobacterium leprae (74.5% identity), and Streptomyces species (75.2% identity to the Streptomyces lividans 23S rRNA gene and 75.1% identity to the Streptomyces griseus 23S rRNA gene). These values are higher than those obtained when comparisons were made with Bacillus subtilis 23S rRNA genes (49.6% identity) and E. coli 23S rRNA genes (53.2% identity), indicating that R. fascians is closely related to Mycobacterium species.

TABLE 2.

Levels of similarity for the R. fascians 23S rRNA gene and homologous genes of Mycobacterium leprae, Mycobacterium paratuberculosis, Micrococcus luteus, Streptomyces griseus, Streptomyces lividans, Bacillus subtilis, and E. coli

| 23S rRNA gene | % Similarity to homologous gene from:

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Escherichia coli | Bacillussubtilis | Streptomyceslividans | Streptomycesgriseus | Micrococcusluteus | Mycobacteriumparatuberculosis | Mycobacteriumleprae | |

| Rhodococcus fascians | 53.2 | 49.6 | 75.2 | 75.1 | 63.6 | 80.2 | 74.5 |

| Mycobacterium leprae | 53.8 | 49.5 | 61.9 | 71.8 | 69.7 | 92.7 | |

| Mycobacterium paratuberculosis | 52.9 | 48.9 | 71.4 | 72.5 | 74.4 | ||

| Micrococcus luteus | 57.1 | 53.6 | 63.6 | 68.9 | |||

| Streptomyces griseus | 47.0 | 48.7 | 91.5 | ||||

| Streptomyces lividans | 46.0 | 52.8 | |||||

| Bacillus subtilis | 57.2 | ||||||

The enzyme I-CeuI cuts at sequences internal to the rrn genes of several bacteria (20). We found a sequence similar to the recognition sequence of this enzyme in the 23S rRNA gene of R. fascians, between positions 4610 and 4635. When the two sequences were aligned, three mismatches were detected. Since I-CeuI permits a certain amount of degeneracy at its recognition site, we tried to digest recombinant plasmids and cosmids containing the rrn operon of R. fascians with I-CeuI, but we had no success. Agarose-embedded DNA of R. fascians was also digested with I-CeuI and subjected to pulsed-field gel electrophoresis. No bands appeared, indicating that the R. fascians 23S rRNA gene is not cleaved by the enzyme.

A 5-bp double direct repeat (5′-CATCGCATCG-3′) was present in the 16S rRNA-23S rRNA spacer. The first seven bases of the 16S rRNA-23S rRNA and 23S rRNA-5S rRNA spacers are almost identical, as shown in Fig. 1D. This sequence of nucleotides could represent a signal for processing of the precursor RNA into mature rRNAs. Two inverted repeats that were 8 bp long (5′-CCCTGACC-3′ and 5′-GGTCAGGG-3′) were found 17 bp downstream from the 3′ end of the 5S rRNA gene. These inverted repeats can form in the RNA a hairpin structure consisting of a stem of eight perfect base pairs and a loop of four bases. This secondary structure is followed by a U-rich region, a typical feature of a transcriptional terminator.

Number of copies of rrn operons in R. fascians.

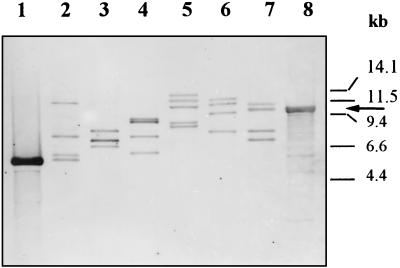

The 6.0-kb SalI fragment sequenced does not contain BamHI sites. This restriction enzyme does not seem to have any target on the rRNA operons of R. fascians. Therefore, blots of BamHI-digested R. fascians D188 total DNA were hybridized with a 2.0-kb EcoRI-XbaI probe containing an internal fragment of pRH2. Four positive BamHI bands were obtained with the DNA of R. fascians D188 (Fig. 2, lane 7). The sizes estimated for these bands were 11.5, 10.4, 7.6, and 7.0 kb. It seems, therefore, that at least four copies of rRNA operons are present in the genome of this strain. To assess whether the copy number of the rRNA operons is the same in other isolates of this species, other strains classified as R. fascians (CECT 3001 and ATCC 12974) were examined in the same experiment. Strain ATCC 12974 also produced four BamHI bands, of 13.0, 11.4, 9.5, and 7.6 kb (Fig. 2, lane 6), whereas strain CECT 3001 produced five BamHI bands having estimated sizes of 15.0, 12.5, 10.8, 8.0, and 7.8 kb (Fig. 2, lane 5). R. fascians CECT 3001 also had a different genome size and produced a different restriction pattern with endonucleases that cut the genome infrequently (25), suggesting that this isolate is different from the R. fascians type strain (ATCC 12974). The pattern of hybridization of the SalI fragment with the 2.0-kb rrn probe was consistent with the pattern obtained with the BamHI fragments. Strain D188 produced four SalI bands (Fig. 2, lane 2), strain ATCC 12974 produced four bands (lane 3), and strain CECT 3001 produced five hybridizing bands (lane 4).

FIG. 2.

Southern blot hybridizations of total DNAs of different strains of R. fascians with the 2.0-kb EcoRI-XbaI probe internal to rrnB. Lanes 1 and 8, DNA of recombinant cosmid p270; lanes 2 to 7, total DNA of R. fascians (lanes 2 and 7, strain D188; lanes 3 and 6, strain ATCC 12974; lanes 4 and 5, strain CECT 3001). The DNAs in lanes 1 to 4 were digested with SalI, and the DNAs in lanes 5 to 8 were digested with BamHI. Note that the DNA insert in cosmid pRF270 (used to isolate the sequenced rrn operon) corresponds to the second rrn band of BamHI-digested DNA of R. fascians D188 (arrow). The positions of size markers (λ digested with PstI plus λ digested with HindIII) are indicated on the right.

The hybridization results shown in Fig. 2 proved that the 6.0-kb SalI band of R. fascians D188 cloned from cosmid pRF270 is internal to the 10.4-kb BamHI band (the second largest band). The rRNA operons were designated rrnA to rrnD on the basis of the descending sizes of the BamHI bands in the strain D188 preparation. The rRNA operon characterized in this paper was rrnB.

Integrative vector targeted to rrn operons.

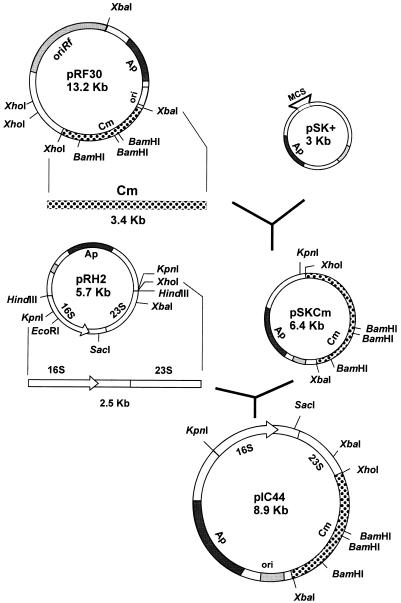

The method used to construct an integrative vector used for targeted integrations at the rrn loci is shown in Fig. 3. The chloramphenicol resistance gene (cmr) from plasmid pRF30 (11) was subcloned in pBlueskript SK+ by digestion with XhoI and XbaI, which gave rise to 6.4-kb plasmid pSKCm. Ribosomal DNA fragments were obtained by digesting plasmid pRH2 with KpnI and XhoI. A 2.5-kb KpnI-XhoI fragment (containing parts of the 16S and 23S rRNA genes) was eluted from an agarose gel and ligated to pSKCm digested with the same enzymes. The resulting 8.9-kb plasmid, pIC44, cannot replicate in R. fascians (since it does not include an R. fascians replicon) but does replicate in E. coli. pIC44 contains the following two antibiotic resistance markers: ampicillin, expressed in E. coli cells; and chloramphenicol, expressed in R. fascians.

FIG. 3.

Construction of integrative vector pIC44. The chloramphenicol resistance gene of plasmid pRF30 was introduced into Bluescript SK+, giving plasmid pSKCm. This plasmid was digested with KpnI and XhoI and ligated to a DNA fragment containing part of the 16S and 23S rRNA genes of the rrnB operon of R. fascians. Ap, ampicillin resistance gene; Cm, chloramphenicol resistance gene; MCS, multiple cloning site; ori, replication origin of the ColE1 plasmid.

Targeted integration at rrn loci of R. fascians.

R. fascians D188.5, a nonpathogenic mutant derivative of D188 which lacks the pFiD188 linear plasmid and the pD188 circular plasmid (7), was electroporated with plasmid pIC44. After 7 days of incubation, 17 chloramphenicol-resistant colonies were isolated. The same experiment was repeated three times, and resistant colonies arose at a frequency of 20 to 50 transformants per μg of plasmid DNA.

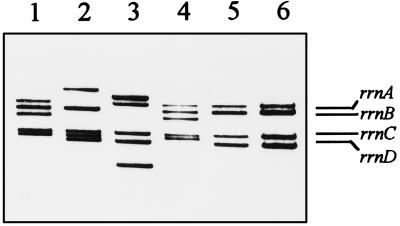

Southern blots obtained with DNAs of several transformants were probed with a 2-kb EcoRI-XbaI fragment of pRH2 (Fig. 3) internal to the R. fascians rrnB operon. Typical results of this experiment are shown in Fig. 4. Lanes 1 through 4 show the results of four different integration events, each corresponding to changes in one of the hybridizing BamHI bands present in control wild-type strain D188 (Fig. 4, lane 5) and in its derivative, D188.5, the mutant used for electroporation (lane 6) (transformants 1 and 4 showed the same integration event). The hybridization patterns exhibited by the transformants are consistent with events involving chromosomal integration by single-recombination events in one of the rrn loci.

FIG. 4.

Southern hybridization of total DNAs of four different transformants (lanes 1 to 4), showing insertions of pIC44 in three of the four rrn operons compared to the hybridization patterns obtained for R. fascians D188 (lane 5) and D188.5 (lane 6), which were used as hosts in the transformation experiments. Lanes 1 and 4 show the same integration event. Blots were hybridized with a 2.0-kb EcoRI-XbaI probe internal to rrnB containing part of the 16S and 23S rRNA genes.

Since plasmid pIC44 contains internal BamHI sites, the disrupted rrn band is converted into two new BamHI fragments that hybridize with the rrn probe (compare the mobility in Fig. 4, lanes 1 through 4, with the mobility in lanes 5 and 6). Integration of complete pIC44 was confirmed by hybridization with an XhoI-XbaI 3.4-kb probe containing the cmr gene. The results showed that the cmr gene had integrated specifically in the rrn bands whose mobility had changed compared with the standard rrn bands of the untransformed strain (data not shown).

Growth rates of mutants disrupted in an rrn operon.

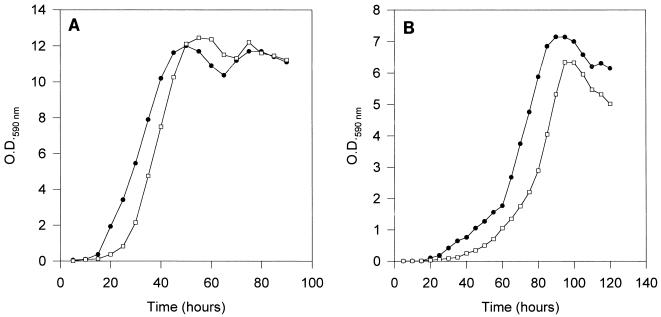

The growth curves of the transformed strains in rich media were similar to the growth curves of untransformed strain D188 (Fig. 5), indicating that integration of exogenous DNA sequences on a single ribosomal operon does not imply that there is a decrease in viability. However, in minimal salts thiamine medium there was a clear delay in the onset of the exponential growth rate, and the maximal cell density obtained was less than the maximal cell density in control cultures. Chloramphenicol resistance was maintained with total stability for at least 120 generations and during repeated transfers into media even when the transformed strains were cultivated in the absence of selective pressure.

FIG. 5.

Growth curves in complex medium (tryptic soy broth) (A) and in minimal salts thiamine medium (B) for wild-type strain R. fascians D188 (•) and mutant strain D188::pIC44.B (□), which contains pIC44 integrated into the rrnB locus. Data are the averages from four determinations at each time point in duplicate experiments. O.D.590 nm, optical density at 590 nm.

Relevance of integrations at the rrn loci in the search for new pathogenicity traits.

Our results indicate that it is possible to direct integrations introducing new sequences of DNA to a well-characterized chromosomal region by using the integrative vector targeted at the rrn loci. By using this integrative vector to transform nonpathogenic R. fascians mutants, it is possible to search for other genes that determine pathogenicity for plants. By integrating random DNA sequences from a pathogenic strain into the chromosome of a nonpathogenic strain, the effects of these genetic traits on phytopathogenicity can be observed. Work is now in progress to isolate and characterize pathogenicity traits by this approach.

The operons encoding rRNA contain usually redundant DNA (DNA that is present in several copies in the genomes of procaryotes). In the gram-positive bacteria, 6 operons have been found in Streptomyces coelicolor (31), 6 operons have been found in Staphylococcus aureus (33), 10 operons have been found in Bacillus subtilis (18), and 5 operons have been found in Corynebacterium glutamicum (2). Disruption of a single copy should not affect the viability and growth rates of a manipulated strain, as shown for E. coli (6, 13). Moreover, it has been reported that in E. coli deletion of four of seven ribosomal operons was required before any significant alteration of growth rate in minimal medium was observed (5). Our data for the growth rates of clones carrying a disrupted copy of the rrn operon clearly indicate that inactivation of one of the rrn loci does not greatly affect the growth rate. Therefore, it is unlikely that a disruption of rrn affects plant pathogenicity, although this question remains open.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by grant BIO92-0708 from the CICYT, Madrid, Spain. A.P. received a PFPI fellowship (Ministry of Education and Science, Madrid, Spain).

We thank J. Desomer and M. van Montagu for providing strains D188 and D188.5 and plasmid pRF30 and M. I. Corrales and R. Barrientos for excellent technical assistance.

REFERENCES

- 1.Amador, E., J. M. Castro, A. Correia, and J. F. Martín. Unpublished data.

- 2.Bathe B, Kalinowsky J, Puhler A. A physical and genetic map of the Corynebacterium glutamicum ATCC 13032 chromosome. Mol Gen Genet. 1996;252:255–265. doi: 10.1007/BF02173771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Birnboim H C, Doly J. A rapid alkaline extraction procedure for screening recombinant plasmid DNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 1979;7:1513–1523. doi: 10.1093/nar/7.6.1513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brosius J, Dull T J, Sleeter D D, Noller H F. Gene organization and primary structure of a ribosomal RNA operon from Escherichia coli. J Mol Biol. 1981;148:107–127. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(81)90508-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Condon C, Liveris D, Squires C, Schwartz I, Squires C L. rRNA operon multiplicity in Escherichia coli and the physiological implications of rrn inactivation. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:4152–4156. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.14.4152-4156.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Condon C, Philips J, Fu Z Y, Squires C, Squires C L. Comparison of the expression of the seven ribosomal RNA operons in Escherichia coli. EMBO J. 1992;11:4175–4185. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1992.tb05511.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Crespi M, Messens E, Caplan A B, Van Montagu M, Desomer J. Fasciation induction by the phytopathogen Rhodococcus fascians depends upon a linear plasmid encoding a cytokinin synthase gene. EMBO J. 1992;11:795–804. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1992.tb05116.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Crespi M, Verreecke D, Temmerman W, Van Montagu M, Desomer J. The fas operon of Rhodococcus fascians encodes new genes required for efficient fasciation of host plants. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:2492–2501. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.9.2492-2501.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Desomer J, Crespi M, Van Montagu M. Illegitimate integration of non-replicative vectors in the genome of Rhodococcus fascians upon electrotransformation as an insertional mutagenesis system. Mol Microbiol. 1991;5:2115–2124. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1991.tb02141.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Desomer J, Dhaese P, Van Montagu M. Conjugative transfer of cadmium resistance plasmids in Rhodococcus fascians strains. J Bacteriol. 1988;170:2401–2405. doi: 10.1128/jb.170.5.2401-2405.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Desomer J, Dhaese P, Van Montagu M. Transformation of Rhodococcus fascians by high-voltage electroporation and development of R. fascians cloning vectors. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1990;56:2818–2825. doi: 10.1128/aem.56.9.2818-2825.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Desomer J, Vereecke D, Crespi M, Van Montagu M. The plasmid-encoded chloramphenicol-resistance protein of Rhodococcus fascians is homologous to the transmembrane tetracycline efflux proteins. Mol Microbiol. 1992;6:2377–2385. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1992.tb01412.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ellwood M, Nomura M. Deletion of a ribosomal ribonucleic acid operon in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1980;143:1077–1080. doi: 10.1128/jb.143.2.1077-1080.1980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Goodfellow M. Genus Rhodococcus. In: Sneath P H A, Mair N S, Sharpe M E, Holt J G, editors. Bergey’s manual of systematic bacteriology. Vol. 2. Baltimore, Md: Williams and Wilkins; 1986. pp. 1472–1481. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Green C J, Stewart G C, Hollis M A, Vold B S, Bott K F. Nucleotide sequence of the Bacillus subtilis ribosomal RNA operon, rrnB. Gene. 1985;37:261–266. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(85)90281-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hanahan D. Studies on transformation of Escherichia coli with plasmids. J Mol Biol. 1983;166:557–580. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(83)80284-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hohn B, Collins J A. A small cosmid for efficient cloning of large DNA fragments. Gene. 1980;11:290–298. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(80)90069-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Itaya M. Physical mapping of multiple homologous genes in the Bacillus subtilis 168 chromosome: identification of ten ribosomal RNA operon loci. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem. 1993;57:1611–1614. doi: 10.1271/bbb.57.1611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kim E, Kim H, Hong S-P, Kang K H, Kho Y H, Park Y-H. Gene organization and primary structure of a ribosomal RNA gene cluster from Streptomyces griseus subsp. griseus. J Bacteriol. 1993;132:21–31. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(93)90510-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Liu S L, Hessel A, Sanderson K E. Genomic mapping with I-CeuI, an intron-encoded endonuclease specific for genes for ribosomal RNA, in Salmonella spp., Escherichia coli, and other bacteria. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:6874–6878. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.14.6874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Luehrsen K, Woese C R, Wolters J, Stackebrandt E. Nucleotide sequence of 5S ribosomal RNA of Rhodococcus fascians. Nucleic Acids Res. 1989;17:5378. doi: 10.1093/nar/17.13.5378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Maniatis T, Fritsch E F, Sambrook J. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Martín J F. Molecular genetics of amino acid-producing corynebacteria. In: Baumberg S, Hunter Y, Rhodes M, editors. Microbial products: new approaches. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press; 1989. pp. 25–59. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Miller H J, Janse J D, Kamerman W, Muller P J. Recent observations on leafy gall in Liliaceae and some other families. Neth J Plant Pathol. 1980;86:55–68. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pisabarro, A., A. Correia, and J. F. Martín. Pulsed-field gel electrophoresis analysis of the genome of Rhodococcus fascians: genome size and linear and circular replicon composition in virulent and avirulent strains. Curr. Microbiol., in press. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 26.Rainey F A, Burghardt J, Kroppenstedt S K, Klatte S, Stackebrandt E. Phylogenetic analysis of the genera Rhodococcus and Nocardia and evidence for the evolutionary origin of Rhodococcus species. Microbiology. 1995;141:523–528. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Roller C, Ludwig W, Schleifer K H. Gram-positive bacteria with a high DNA G+C content are characterized by a common insertion within their 23S rRNA genes. J Gen Microbiol. 1992;138:1167–1175. doi: 10.1099/00221287-138-6-1167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sabart P R, Gakovich D, Hanson R S. Avirulent isolates of Corynebacterium fascians that are unable to utilize agmatine and proline. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1986;52:33–36. doi: 10.1128/aem.52.1.33-36.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schwarzer A, Pühler A. Manipulation of Corynebacterium glutamicum by gene disruption and replacement. Bio/Technology. 1991;9:84–87. doi: 10.1038/nbt0191-84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Stapp C. Bacterial plant pathogens. Oxford, United Kingdom: Oxford University Press; 1961. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Van Wezel G P, Krab L M, Douthwaite S, Bibb M J, Vijgenboom E, Bosch L. Transcription analysis of Streptomyces coelicolor A3(2) rrnA operon. Microbiology. 1994;140:3357–3365. doi: 10.1099/13500872-140-12-3357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Vidaver A K. The plant pathogenic corynebacteria. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1982;36:495–517. doi: 10.1146/annurev.mi.36.100182.002431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wada A, Ohta H, Kulthanan K, Hiramatsu K. Molecular cloning and mapping of 16S-23S rRNA gene complexes of Staphylococcus aureus. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:7483–7487. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.22.7483-7487.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]