Abstract

Background

Fluorine 18 (18F) fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) positron emission tomography/computed tomography (PET/CT) has limitations in staging hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). The recently introduced 18F-labeled fibroblast-activation protein inhibitor (FAPI) has shown promising prospects in detection of HCC lesions. This study aimed to investigate the initial staging and restaging performance of 18F-FAPI PET/CT compared to 18F-FDG PET/CT in HCC.

Methods

This prospective study enrolled histologically confirmed HCC patients from March 2021 to September 2022. All patients were examined with 18F-FDG PET/CT and 18F-FAPI PET/CT within 1 week. The maximum standard uptake value (SUVmax), tumor-to-background ratio (TBR), and diagnostic accuracy were compared between the two modalities.

Results

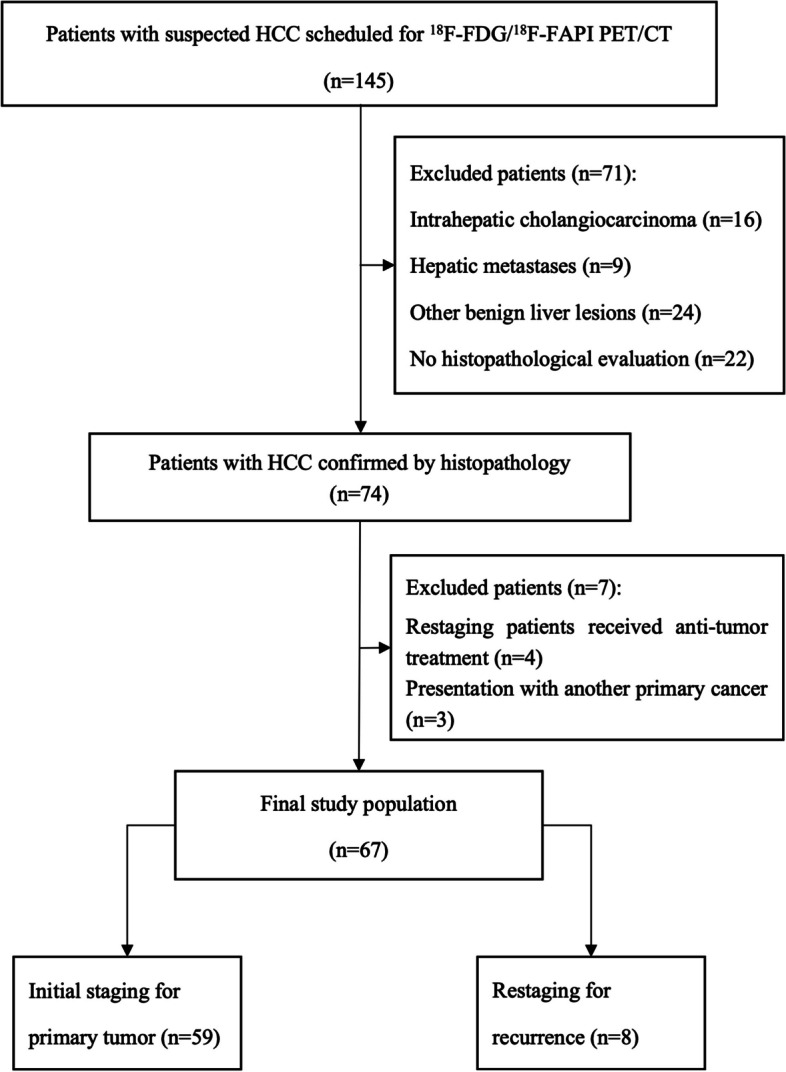

A total of 67 patients (57 men; median age, 57 [range, 32–83] years old) were included. 18F-FAPI PET showed higher SUVmax and TBR values than 18F-FDG PET in the intrahepatic lesions (SUVmax: 6.7 vs. 4.3, P < 0.0001; TBR: 3.9 vs. 1.7, P < 0.0001). In diagnostic performance, 18F-FAPI PET/CT had higher detection rate than 18F-FDG PET/CT in intrahepatic lesions [92.2% (238/258) vs 41.1% (106/258), P < 0.0001] and lymph node metastases [97.9% (126/129) vs 89.1% (115/129), P = 0.01], comparable in distant metastases [63.6% (42/66) vs 69.7% (46/66), P > 0.05]. 18F-FAPI PET/CT detected primary tumors in 16 patients with negative 18F-FDG, upgraded T-stages in 12 patients and identified 4 true positive findings for local recurrence than 18F-FDG PET, leading to planning therapy changes in 47.8% (32/67) of patients.

Conclusions

18F-FAPI PET/CT identified more primary lesions, lymph node metastases than 18F-FDG PET/CT in HCC, which is helpful to improve the clinical management of HCC patients.

Trial registration

Clinical Trials, NCT05485792. Registered 1 August 2022, Retrospectively registered.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s40644-023-00626-y.

Keywords: Hepatocellular carcinoma, Fibroblast activation protein; 18F-FAPI; PET; CT

Background

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is the most common type of primary liver cancer, and the fourth leading cause of cancer-related deaths worldwide [1]. Patients diagnosed in early stages of the disease have survival rates up to 50–70%. However, more than half of patients were diagnosed with advanced disease, and their 3-year survival rates were only 20–30% [2–4]. Therefore, early diagnosis and accurate staging for HCC patients are critical for planning therapy. Morphological imaging modalities, such as contrast computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), are commonly used in the diagnosis of HCC, but they are inadequate in detecting distant metastasis [5]. In addition, due to the postoperative anatomical changes, it is difficult to monitor the recurrence of HCC based on morphological imaging modalities [6]. Fluorine-18 fluorodeoxyglucose (18F-FDG) positron emission tomography/computed tomography (PET/CT) is an effective imaging tool for staging for many malignancies. However, 18F-FDG is not a useful tracer for detection of primary tumours of HCC [7]. Because of the low 18F-FDG uptake in well differentiated HCC and the physiological uptake in nomal liver, the detection rate of 18F-FDG PET/CT for primary HCC is less than 50% [8].

Fibroblast activation protein (FAP) is a serine protease that belongs to the dipeptidyl peptidase-IV (DPP-IV) family located in fbroblast membranes [9]. FAP is overexpressed in the cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs) of 90% of all epithelial carcinomas, including HCC [10]. Therefore, FAP-targeted radiopharmaceuticals can be considered a promising approach for the visualization of CAFs in HCC. Recently, 68 Ga labeled fibroblast activating protein inhibitor (68 Ga-FAPI) has demonstrated diagnostic value in many types of malignancies [11]. Moreover, several pilot studies with small sample size have shown 68 Ga-FAPI PET/CT is more sensitive than 18F-FDG PET/CT in detecting HCC lesions [3, 12–14]. Although 68 Ga-FAPI is a promising radiopharmaceutical for clinical application of malignancies, it still has some disadvantages, such as high production costs and short half-life [15–17]. 18F-FAPI has a longer half-life and is more widely used to meet the needs of a large number of patients, and 18F-FAPI is equivalent to 68 Ga-FAPI in detecting malignant tumors [17]. However, to our acknowledge, there is no study have explored the clinical staging value of 18F-FAPI PET/CT in HCC systematically.

Therefore, the aim of this head to head prospective study was to investigate whether the potential diagnostic value of 18F-FAPI PET/CT is superior to 18F-FDG PET/CT for HCC patients, and to explore the impact of 18F-FAPI PET/CT on the clinical therapeutic management of HCC.

Materials and methods

Patients

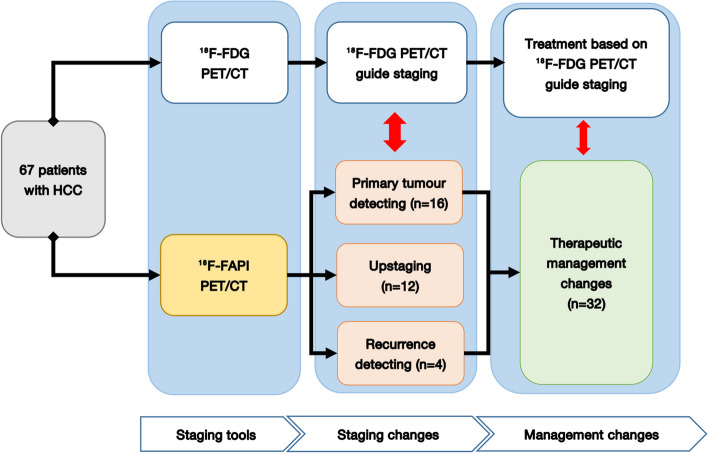

This prospective study was authorized by the ethics committee of Affiliated Cancer Hospital & Institute of Guangzhou Medical University (ethics committee permission No.2021-sw07; clinical trial registration: NCT05485792). From March 2021 to September 2022, A total of 145 patients with suspected HCC were considered as candidate participants consecutively. The enrolled patients met the following criteria: (i) age ≥ 18 years old; (ii) patients with suspected liver malignant lesions based on traditional diagnostic imaging (CT or MRI or ultrasound) and clinical symptoms; and (iii) patients who agreed to receive paired 18F-FDG PET/CT and 18F-FAPI PET/CT scans within one week. The exclusion criteria were as follows: (i) restaging patients who have received chemotherapy, radiation therapy, or targeted therapy within 3 months prior to scanning; (ii) patients who had another primary cancer at the time of evaluation; and (iii) unable to provide pathological findings to confirm HCC. Finally, a total of 67 patients were enrolled. The flow chart of our study was depicted in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Study flowchart shows inclusion and exclusion criteria. HCC = hepatocellular carcinoma; 18F = fluorine 18; FAPI = fibroblast activation protein inhibitor; FDG = fluorodeoxyglucose; PET/CT = positron emission tomography/computed tomography

18F-FDG/18F-FAPI PET/CT acquisition and imaging

18F-FDG was automatically synthesized using a PET trace cyclotron and the 18F-FDG synthesizer module (Tracerlab FXF-N, GE Healthcare). The detailed methodology for radiolabeling DOTA-FAPI can be found in the Supplementary material. 18F-FDG and 18F-FAPI PET/CT were performed using a PET/CT scanner (Discovery 710, GE Healthcare, Milwaukee, WI, USA) within 1 week. The imaging preparation and parameters of 18F-FDG/18F-FAPI PET/CT was performed according to a previously reported protocol [18].

18F-FDG and 18F-FAPI PET/CT image analysis

All images were visually interpreted independently by four board certified nuclear medicine physicians. To reduce individual interpretation bias, 18F-FDG PET/CT images were reviewed by Hao Peng and Shuyi Li, and 18F-FAPI PET/CT images were reviewed by Shuqin Jiang and Linqi Zhang. A consensus was reached following a comprehensive discussion in cases of discrepancies.

For visual analysis, lesions were divided into primary tumor and extrahepatic organs/regions (lymph nodes and distant metastasis) based on their location. Individual lymph node was then classified into four regions, including the head and neck, thoracic (supraclavicular, mediastinal, and axillary lymph nodes), abdominal (para-aortic, porta hepatic, retroperitoneal, celiac lymph nodes), and pelvic (parailiac vessels and inguinal lymph nodes). Distant involvement such as lung, bone, peritoneal and adrenal metastasis was categorized as an individual site. A positive lesion was considered when met the following criteria [19]: (i) a focal area had abnormally elevated 18F-FDG or 18F-FAPI uptake, accompanied by the abnormal density/signal in the corresponding sites on CT/MRI; and (ii) the lesions had typical features from contrast-enhanced CT (ceCT) or ce-MRI.

For semi-quantitative assessment, a region of interest (ROI) was drawn along the entire lesion on the axial PET image or anatomical information presented by CT/MRI (lesions with low or equal tracer uptake), and the maximum standardized uptake value (SUVmax), the diameter of each lesion and the amount of lesions per region were recorded. The tumor-to-background ratio (TBR) of each lesion was calculated by dividing the SUVmax of the lesion by the SUVmean of the background tissue (liver background for liver lesions; mediastinal blood pool background for macrovascular invasion, lymph nodes and peritoneal lesions; lung background for lung lesions; contralateral adrenal gland background for adrenal gland lesions; and L5 background for bone lesions). The TNM stage was assigned based on the eighth edition of the American Joint Committee on Cancer staging system [20].

Reference standard

All patients were diagnosed HCC (at least one lesion) based on histological evaluation of biopsy or surgical specimens. Due to ethical and technical issues, not all lesions are pathologically confirmed, especially for intrahepatic foci, lymph node metastasis and distant metastasis. When histopathology was unavailable for positive PET/CT findings, a combination of clinical and multimodality radiographic (including PET/CT, contrast-enhanced CT, MRI, and ultrasound) follow-up for more than 6 months was taken as the reference standard of diagnosis to validate the PET/CT findings [18]. Follow-up imaging findings that were considered malignant lesions had either progress or response to anticancer therapy in terms of reduction in size and/or number of lesions.

Statistical analysis

Quantitative variables are presented as the median [range (minimum to maximum)], and categorical variables are presented as frequencies (percentages). The diagnostic performance for HCC of 18F-FDG PET and 18F-FAPI PET was compared using the McNemar’s test. The SUVmax and TBR obtained from 18F-FDG PET and 18F-FAPI PET images were compared using the paired Wilcoxon signed-rank test. All statistical tests were performed using SPSS Statistics 17.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) software. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Patients characteristics

Sixty-seven patients with histological proven HCC (57 men and 10 women; median age, 57 [range, 32–83] years old) were enrolled in our study (Fig. 1). The most common etiology was hepatitis B infection (n = 46, 68.7%), and eighteen patients presented with cirrhosis. Fifty-nine treatment-naive patients received paired 18F-FDG and 18F-FAPI PET examinations for initial staging, and 8 patients with recurrent HCC underwent paired examinations for restaging. 26.9% (18 of 67) of patients had intrahepatic lesions invading macrovascular, and 19.4% (13 of 67) of patients were identified to have extrahepatic metastasis (6 patients with lymph node metastasis and 9 patients with distant metastasis) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Baseline patient characteristics of the enrolled patients

| Description of patients | 67 |

|---|---|

| Age [years, median (IQR)] | 57(32–83) |

| M:F radio | 57:10 |

| Cirrhosis/Non-Cirrhosis | 18/49 |

| Etiology (HBV/HCV/AH) | 46/1/1 |

| Clinical biochemical testing | |

| AFP (> 20 ng/ml) | 33 |

| CEA (> 5U/ml) | 21 |

| CA19-9 (> 37U/ml) | 9 |

| Patient status | |

| Staging | 59 |

| Recurrence detection after treatment | 8 |

| Tumor number | |

| Solitary | 32 |

| Multifocal | 35 |

| Macrovascular invasion (Yes/No) | 18/49 |

| Tumor staging (Initial evaluation) | |

| T1 | 16 |

| T2 | 13 |

| T3 | 14 |

| T4 | 16 |

| Extrahepatic Lesions (N/total) | 13/67 |

| Lymph node metastasis | 7 |

| Distant metastasis | 9 |

M male, F female, HBV Hepatitis B virus, HCV Hepatitis C virus, AH Alcoholic hepatitis, IQR interquartile range, AFP alpha-fetoprotein, CEA carcinoembryonic antigen, CA 19–9 carbohydrate antigen 199

18F-FDG PET and 18F-FAPI PET in detection of intrahepatic lesions

In the initial staging group of 59 patients (a total of 234 lesions), the detecting rate of 18F-FAPI PET for intrahepatic lesions is significantly higher than 18F-FDG PET among patients with T1-3 stages (detail in Table 2, Figs. 2 and 3) [T1: 93.8% (15/16) vs. 31.3% (5/16), P = 0.0006; T2: 100% (13/13) vs. 38.5% (5/13), P = 0.0016; T3: 100% (14/14) vs. 35.7% (5/14), P = 0.0006; T4: 100% (16/16) vs. 100% (16/16), P > 0.05], and the lesions in T2-4 stage patients were more clearly characterized by higher activity (median SUVmax, T2: 9.9 vs. 5.3, P = 0.0339; T3: 10.9 vs. 5.5, P = 0.0085; T4: 12.9 vs. 14.5, P = 0.0457) and clearer boundaries (median TBR, T2: 5.0 vs. 1.7, P = 0.0002; T3: 6.6 vs. 2.1, P = 0.0001; T4: 10.2 vs. 3.1, P < 0.0001) in 18F-FAPI PET than in 18F-FDG PET (Supplementary Fig. 1a & b).

Table 2.

Comparison of 18F-FDG PET/CT and 18F-FAPI PET/CT for the intrahepatic lesions of 67 patients

| Description of lesions | No. of patients (No. of lesions) | 18F-FDG PET/CT | 18F-FAPI PET/CT |

P value (FDG vs. FAPI) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Positive detection of lesions(%) | Median SUVmax (range) | Median TBR (range) | Positive detection of lesions(%) | Median SUVmax (range) | Median TBR (range) | SUVmax | TBR | ||

| Total | 67 | 35(52.2%) | 5.3(2.3–22.5) | 2.1(1.0–15.2) | 66(98.5%) | 9.9(0.4–24.1) | 6.0(0.8–30.0) | < 0.0001 | < 0.0001 |

| Primary Tumor | 59 | 31(53.4%) | 5.6(2.3–22.5) | 2.2(1.0–15.2) | 58(98.3%) | 9.9(0.4–24.1) | 6.7(0.8–30.0) | < 0.0001 | < 0.0001 |

| T1 | 16 | 5(31.3%) | 3.75(2.3–11.2) | 1.5(1.0–4.3) | 15(93.8%) | 4.65(0.4–15.2) | 3.6(0.8–27.8) | 0.1305 | < 0.0001 |

| T2 | 13 | 5(38.5%) | 5.3(2.3–22.5) | 1.7(1.4–9.8) | 13(100%) | 9.9(4.6–15.6) | 5.0(1.5–15.0) | 0.0339 | 0.0002 |

| T3 | 14 | 5(35.7%) | 5.5(3.7–15.5) | 2.1(1.3–6.4) | 14(100%) | 10.9(3.3–24.1) | 6.6(2.6–30.0) | 0.0085 | 0.0001 |

| T4 | 16 | 16(100%) | 14.5(4.1–18.4) | 3.5(1.9–15.2) | 16(100%) | 12.9(2.2–22.9) | 10.2(4.1–22.5) | 0.0457 | < 0.0001 |

| Recurrent Tumor | 8 | 4(50.0%) | 3.6(2.4–11.8) | 1.4(1.0–5.2) | 8(100%) | 9.8(2.9–16.8) | 5.4(2.6–12.9) | 0.0781 | 0.0078 |

| Tumor Size(cm) | |||||||||

| Total | 67(258) | 106(41.1%) | 4.3(1.3–22.5) | 1.7(0.5–15.2) | 238(92.2%) | 6.7(0.4–24.1) | 3.9(0.8–30.0) | < 0.0001 | < 0.0001 |

| ≤ 2 | NA(110) | 28(25.5%) | 3.7(1.3–9.8) | 1.5(0.5–4.3) | 97(88.1%) | 5.9(1.2–18.3) | 3.1(0.8–22.9) | < 0.0001 | < 0.0001 |

| > 2, ≤ 5 | NA(89) | 34(38.2%) | 4.2(2.2–13.8) | 1.6(0.8–10.3) | 82(92.1%) | 6.5(0.4–22.4) | 3.8(0.8–30.0) | < 0.0001 | < 0.0001 |

| > 5 | NA(59) | 44(74.6%) | 7.1(3.7–22.5) | 2.5(1.3–15.2) | 59(100%) | 11.2(2.2–24.1) | 6.6(2.6–26.1) | < 0.0001 | < 0.0001 |

| No. of lesions | |||||||||

| Solitary | 32(32) | 12(37.5%) | 4.35(2.3–22.5) | 1.7(1.0–9.8) | 31(96.9%) | 6.35(0.4–15.6) | 5.15(0.8–27.8) | 0.0152 | < 0.0001 |

| Multifocal | 35(226) | 94(41.6%) | 4.3(1.3–18.4) | 1.7(0.5–15.2) | 207(91.6%) | 6.7(1.2–24.1) | 3.8(0.8–30.0) | < 0.0001 | < 0.0001 |

| Macrovascular invasion | 18(18) | 18(100%) | 5.6(2.7–23.3) | 3.5(1.4–12.3) | 16(88.9%) | 4.65(0.5–8.2) | 2.9(1.2–4.6) | 0.007 | 0.043 |

Bold fonts indicate significant difference between FDG and FAPI (P < 0.05)

18F Fluorine 18, FDG fluorodeoxyglucose, FAPI fibroblast activation protein inhibitor, PET/CT positron emission tomography/computed tomography, HCC hepatocellular carcinoma, SUVmax maximum standardized uptake value, TBR Tumor-to-background ratio, NA Not applicable

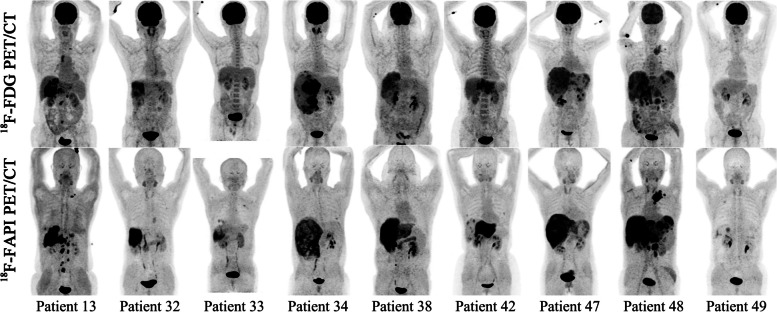

Fig. 2.

Nine representative patients with HCC underwent 18F-FDG & 18F-FAPI PET/CT imaging. 18F-FAPI PET/CT outperformed.18F-FDG PET/CT in detecting primary tumors (Patient No. 32, 33, 34, 49), intrahepatic subfoci (Patient No. 13, 38, 42, 47, 48), supraclavicular lymph node metastases (Patient No. 13, 48), retroperitoneum lymph node metastases (Patient No. 48), and comparable in detecting distant metastases (Patient No. 48)

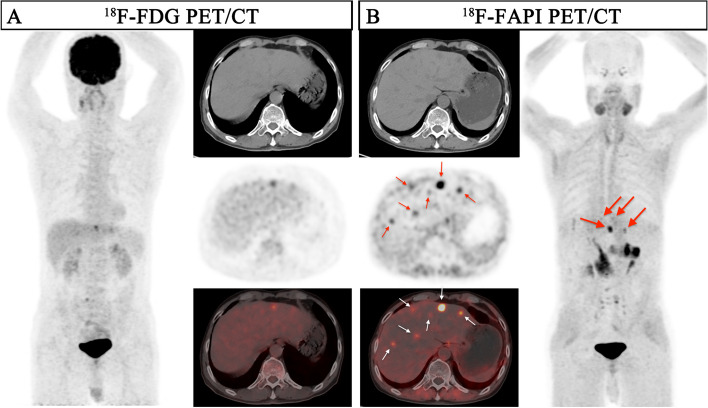

Fig. 3.

A 41-year-old male patient (Patient No. 51) with HCC (moderately differentiated) was confirmed by biopsy. 18F-FDG PET/CT displayed moderate uptake in the section II of the liver; However, the corresponding CT scan showed more nodules in other lobes of the liver. 18F-FAPI PET/CT detects greater radiotracer in primary lesions and other intrahepatic subfoci on both MIP (large arrow) and axial images (small arrow)

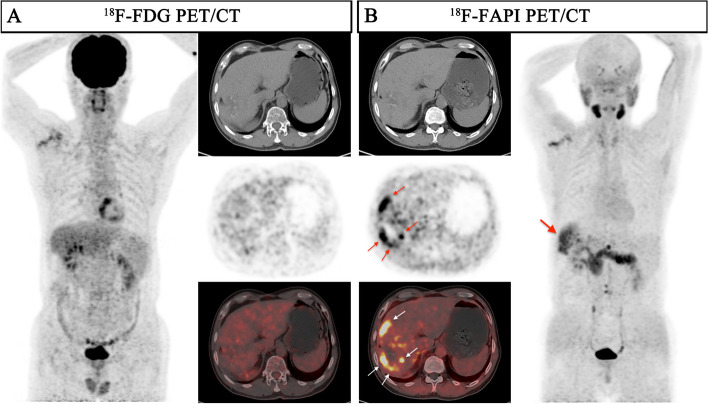

In the evaluation of recurrent tumors in 8 patients (a total of 24 lesions), there was no statistically significance in the sensitivity of detecting recurrent tumors between 18F-FAPI PET and 18F-FDG PET [100% (8/8) vs. 50.0% (4/8), P = 0.0769], while the TBR of 18F-FAPI PET/CT was significantly higher than that of 18F-FDG PET/CT for local recurrence (median TBR: 5.4 vs 1.4, P = 0.0078) (Table 2 and Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

A 57-year-old male patient (Patient No. 50) with recurrent HCC (moderately differentiated) was confirmed by postoperative pathology. 18F-FDG PET/CT displayed no uptake in this lesion, although the corresponding CT scan showed lamellar low-density shadow in right lobe of the liver. 18F-FAPI PET/CT revealed intense uptake (SUVmax 9.0; TBR 6.0) in the recurrent lesion on both maximum intensity projection (MIP) (large arrow) and axial images (small arrow)

As shown in Table 2, 18F-FAPI PET/CT depicted 92.2% of the intrahepatic lesions (238 of 258), which was much better than 41.1% (106 of 258) of 18F-FDG PET/CT (P < 0.0001). According to tumour size, 18F-FAPI PET detected significantly more intrahepatic lesions than 18F-FDG PET among different sizes subgroups, especially in the early stage HCC (Fig. 3) [≤ 2 cm: 88.1% (97/110) vs. 25.5% (28/110), P < 0.0001; > 2 cm and ≤ 5 cm: 89.9% (80/89) vs. 38.2% (34/89), P < 0.0001; > 5 cm: 100% (59/59) vs. 74.6% (44/59), P < 0.0001]. Besides, there were also significant differences in 18F-FAPI PET and 18F-FDG PET uptake among different tumor size groups (all P < 0.0001, Supplementary Fig. 1c & d).

A total of 18 patients had macrovascular invasion (16 patients for initial staging; 2 patients for restaging). There was no statistically significance in the sensitivity of detecting macrovascular invasion between 18F-FAPI PET and 18F-FDG PET [88.9% (16/18) vs. 100% (18/18), P = 0.486], and the SUVmax and TBR of 18 paired macrovascular invading lesions on 18F-FAPI PET/CT images were significantly lower than on 18F-FDG PET/CT images (P = 0.007 and P = 0.043, respectively) (Table 2).

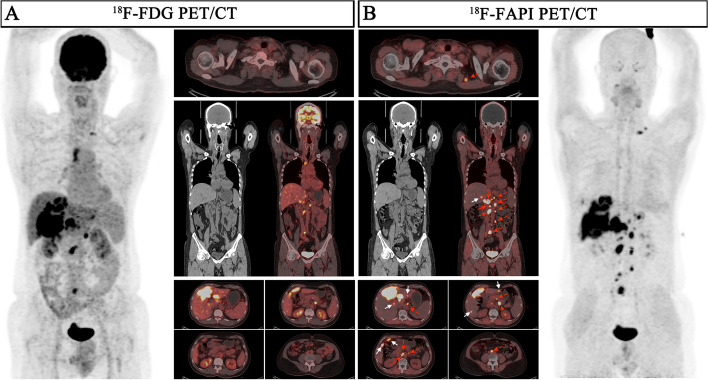

18F-FDG PET and 18F-FAPI PET for assessment of lymph node metastasis

According to the diagnostic criteria for lymph node metastases, 129 lymph nodes lesions in 7 patients were evaluated. The sensitivity of 18F-FAPI PET in detecting lymph node metastases was 97.9% (126/129), which was higher than 18F-FDG PET [89.1% (115/129), P = 0.01]. The TBR of 18F-FAPI PET in lymph node metastasis was significantly higher than that in 18F-FDG PET (6.3 vs 4.5, P < 0.0001), while there was no significant difference in SUVmax (7.3 vs 7.6, P = 0.7475) (Table 3 and Fig. 2). Sixty-four of 129 (48.8%) lymph node metastasis were greater than 1.0 cm in short diameter, and the detecting rate of 18F-FAPI PET and 18F-FDG PET for these lymph nodes both were 100%. For lymph node in short diameter (≤ 1.0 cm), the sensitivities of 18F-FAPI PET is significantly higher than 18F-FDG PET (Fig. 5) [95.4% (62/65) vs. 78.5% (51/65), P < 0.0001]. The TBR of 18F-FAPI PET in metastasis lymph node (≤ 1.0 cm) were significantly higher than 18F-FDG PET (5.0 vs. 3.3, P = 0.0016), but there was no significance in SUVmax between two agents (Supplementary Fig. 1e & f).

Table 3.

Comparison of 18F-FDG PET/CT and 18F-FAPI PET/CT for the extrahepatic lesions

| Description of lesions | No. of patients (No. of lesions) | 18F-FDG PET/CT | 18F-FAPI PET/CT |

P value (FDG vs. FAPI) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Positive detection of lesions(%) | Median SUVmax (range) | Median TBR (range) | Positive detection of lesions(%) | Median SUVmax (range) | Median TBR (range) | SUVmax | TBR | ||

| Lymph node metastasis | 7(129) | 115(89.1%) | 7.6(1.2–20.7) | 4.5(0.5–17.3) | 126(97.9%) | 7.3(2.0–21.8) | 6.3(1.4–26.5) | 0.7475 | < 0.0001 |

| Head and neck regions | 3(16) | 13(81.3%) | 4.8(1.2–14.7) | 2.1(0.5–9.2) | 16(100%) | 7.7(3.0–13.9) | 5.2(1.5–17.4) | 0.0148 | < 0.0001 |

| Thoracic regions | 2(15) | 15(100%) | 11.5(3.1–16.4) | 7.2(1.3–10.3) | 15(100%) | 13.1(8.5–21.2) | 16.4(4.7–26.5) | 0.0267 | < 0.0001 |

| Abdominal regions | 7(86) | 81(94.2%) | 7.95(1.8–20.7) | 4.9(0.8–17.3) | 83(96.5%) | 6.9(2.0–21.8) | 5.3(1.4–16.9) | 0.0772 | 0.2818 |

| Pelvic regions | 2(12) | 6(50%) | 2.8(1.7–10.6) | 1.3(0.8–6.6) | 12(100%) | 7.1(3.0–13.8) | 7.4(2.3–10.6) | 0.1763 | 0.0005 |

| Lymph node size(cm) | |||||||||

| ≤ 1 | NA(65) | 51(78.5%) | 5.2(1.2–16.7) | 3.3(0.5–13.9) | 62(95.4%) | 6.2(2.0–21.8) | 5.0(1.4–23.1) | 0.1253 | 0.0016 |

| > 1 | NA(64) | 64(100%) | 10.55(3.1–20.7) | 6.75(1.3–17.3) | 64(100%) | 9.35(3.1–21.2) | 10.15(2.0–26.5) | 0.3771 | 0.0004 |

| Distant lesions | 9(66) | 46(69.7%) | 5.0(0.7–25.4) | 6.5(0.6–84.7) | 42(63.6%) | 2.75(0.5–20.4) | 7.45(1.7–30.0) | 0.0139 | 0.582 |

| Lung | 6(24) | 7(29.1%) | 1.4(0.7–10.2) | 6.5(3.5–51.0) | 8(37.5%) | 1.65(0.5–10.5) | 13.0(1.7–28.0) | 0.7196 | 0.0639 |

| Bone | 3(24) | 24(100%) | 11.1(5.2–25.4) | 24.15(2.9–84.7) | 16(66.7%) | 3.0(1.1–20.4) | 6.3(2.8–30.0) | 0.0007 | 0.0014 |

| Peritoneal | 1(17) | 14(82.4%) | 3.9(1.3–7.7) | 1.7(0.6–3.3) | 17(100%) | 4.8(2.3–7.0) | 5.3(2.6–7.8) | 0.0731 | < 0.0001 |

| Adrenal gland | 1(1) | 1(100%) | 5.6(NA) | 1.9(NA) | 1(100%) | 4.8(NA) | 4.8(NA) | - | - |

| Total | 13(195) | 161(82.6%) | 6.3(0.7–25.4) | 5.1(0.5–84.7) | 168(86.2%) | 6.4(0.5–21.8) | 6.6(1.4–30.0) | 0.2538 | 0.0007 |

Bold fonts indicate significant difference between FDG and FAPI (P < 0.05)

18F Fluorine 18, FDG fluorodeoxyglucose, FAPI fibroblast activation protein inhibitor, PET/CT positron emission tomography/computed tomography, HCC hepatocellular carcinoma, SUVmax maximum standardized uptake value, TBR Tumor-to-background ratio, NA Not applicable

Fig. 5.

A 62-year-old male patient (Patient No. 13) with HCC (moderately differentiated) was confirmed by biopsy. Compared with 18F-FDG PET/CT, 18F-FAPI PET/CT revealed more intrahepatic subfoci (white arrow in axial images) and more lymph node metastases (red arrow in axial, coronal images). There was a lymph node in right upper mediastinum, showing low-uptake in 18F-FAPI but intense uptake in 18F-FDG, final pathological findings confirmed inflammatory

18F-FDG PET and 18F-FAPI PET in evaluation of distant metastasis

A total of 66 distant metastatic lesions in 9 patients were confirmed based on the reference standards. There was no statistically significant difference in sensitivity between 18F-FAPI PET/CT and 18F-FDG PET/CT in detecting distant metastatic lesions [42 (63.6%) vs 46 (69.7%), P = 0.58)] (Supplementary Fig. 1g).

Regarding the 3 patients with bone metastasis, 18F-FAPI PET had a significant lower sensitivity than 18F-FDG PET [66.7% (16/24) vs. 100% (24/24), P = 0.004], and 18F-FDG PET/CT showed higher SUVmax and TBR than 18F-FAPI PET/CT in bone metastasis evaluation (median SUVmax: 11.0 vs 3.0, P = 0.0007; median TBR: 24.15 vs 6.3, P = 0.0014) (Table 3). Only one patients was diagnosed with peritoneal metastasis (17 lesions, Patient 22 Supplementary Table S1). In contrast to the SUVmax, the differences between 18F-FAPI and 18F-FDG imaging were significant quantified by the TBR (median SUVmax: 4.8 vs 3.9, P = 0.0731; median TBR: 5.3 vs 1.7, P < 0.0001) (Table 3).

Changes in staging and therapeutic management

In the initial assessment of 59 patients, 18F-FAPI imaging detected primary HCC tumors in 16 patients with 18F-FDG-negative. These patients received the available treatment as early as possible since 18F-FAPI detected the primary lesion [11 patients were treated with surgery or ablation; 4 patients with transcatheter arterial chemoembolization (TACE) plus systemic therapy; and 1 patients with TACE plus systemic therapy plus radiotherapy]. With more intrahepatic subfoci revealed by 18F-FAPI PET than 18F-FDG PET/CT, the TNM staging was upgraded in 12 patients (12/59, 20.3%) (four from IB to II, eight from II to IIIA). As a result, instead of the previously planned surgical treatment, four patient received TACE and systemic chemotherapy, while eight patients received palliative systemic treatment and radiation (Table 4 and Fig. 6).

Table 4.

Comparison of 18F-FDG PET based and 18F-FAPI PET based TNM restaging

| Patient No | TNM staging (FDG PFT based) |

TNM staging (FAPI PFT based) |

Additional finding ( 18F-FAPI PET) |

Staging change | Primary lesion detected |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | T2N0M0 | T3N0M0 | Multifocal intrahepatic foci | Up | - |

| 2 | T2N0M1 | T3N0M1 | Multifocal intrahepatic foci | Up | - |

| 4 | T2N0M0 | T2N0M0 | - | None | Yes |

| 6 | T1N0M0 | T1N0M0 | - | None | Yes |

| 7 | T2N0M0 | T3N0M0 | Multifocal intrahepatic foci | Up | - |

| 10 | T1N0M0 | T1N0M0 | - | None | Yes |

| 15 | T3N0M0 | T2N0M0 | Multifocal intrahepatic foci | Up | - |

| 16 | T1N0M0 | T1N0M0 | - | None | Yes |

| 18 | T1N0M0 | T1N0M0 | - | None | Yes |

| 19 | T2N0M0 | T3N0M0 | Multifocal intrahepatic foci | Up | - |

| 21 | T2N0M0 | T3N0M0 | Multifocal intrahepatic foci | Up | - |

| 23 | T1N0M0 | T1N0M0 | - | None | Yes |

| 25 | T1N0M0 | T1N0M0 | - | None | Yes |

| 26 | T1N0M0 | T1N0M0 | - | None | Yes |

| 27 | T2N0M0 | T2N0M0 | - | None | Yes |

| 28 | T3N0M1 | T2N0M1 | Multifocal intrahepatic foci | Up | - |

| 29 | T2N0M0 | T2N0M0 | - | None | Yes |

| 30 | T3N0M0 | T3N0M0 | - | None | Yes |

| 31 | T1N0M0 | T1N0M0 | - | None | Yes |

| 36 | T2N0M1 | T2N0M1 | - | None | Yes |

| 44 | T2N0M1 | T1N0M1 | Multifocal intrahepatic foci | Up | - |

| 51 | T2N0M0 | T1N0M0 | Multifocal intrahepatic foci | Up | - |

| 55 | T2N0M0 | T1N0M0 | Multifocal intrahepatic foci | Up | - |

| 56 | T1N0M0 | T1N0M0 | - | None | Yes |

| 60 | T2N0M0 | T1N0M0 | Multifocal intrahepatic foci | Up | - |

| 63 | T1N0M0 | T1N0M0 | - | None | Yes |

| 65 | T3N0M0 | T2N0M0 | Multifocal intrahepatic foci | Up | - |

| 66 | T1N0M0 | T1N0M0 | - | None | Yes |

Bold fonts indicate the changing segment in TNM stanging after 18F-FAPI PET/CT imaging

18F Fluorine 18, FDG fluorodeoxyglucose, FAPI fibroblast activation protein inhibitor, PET positron emission tomography, TNM Tumor Node Metastasis

Fig. 6.

Overview of impact of 18F-FAPI PET/CT on staging and therapeutic management in HCC, therapeutic management was altered in 31 of 67 individuals

Among the other 8 patients with recurrence, 18F-FAPI PET identified 18F-FDG-negative locally recurrent tumors in 4 patients (50%) (Table 5), resulting in cancellation of dynamic review and administration of surgery or ablation treatment (Fig. 6).

Table 5.

Comparison of 18F-FDG PET and 18F-FAPI PET in post treatment patients

| Patient No | Primary treatment | Local recurrence detection | Distant metastasis detection | Additional finding (18F-FAPI PET) |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 18F-FDG PET | 18F-FAPI PET | 18F-FDG PET | 18F-FAPI PET | |||

| 3 | surgery | - | + | - | - | Local recurrence |

| 32 | systemic therapy | + | + | - | - | - |

| 33 | TACE | + | + | - | - | - |

| 45 | TACE and RFA | - | + | - | - | Local recurrence |

| 48 | surgery and systemic therapy | + | + | + | + | - |

| 49 | TACE | - | + | + | + | Local recurrence |

| 50 | surgery and systemic therapy | - | + | - | - | Local recurrence |

| 58 | RFA and systemic therapy | + | + | - | - | - |

18F Fluorine 18, FDG fluorodeoxyglucose, FAPI fibroblast activation protein inhibitor, PET positron emission tomography, TNM Tumor Node Metastasis, TACE transcatheter arterial chemoembolization, RFA radiofrequency ablation

Discussion

Our study have demonstrated 18F-FAPI PET/CT plays a complementary role for 18F-FDG PET/CT examination in HCC. The results showed 18F-FAPI PET/CT is superior to 18F-FDG PET/CT in detecting intrahepatic lesions, lymph node metastasis and peritoneal metastasis. In visual analysis, 18F-FAPI PET/CT had higher detection rate than 18F-FDG PET/CT in intrahepatic lesions (92.2% vs 41.1%, P < 0.0001), lymph node metastases (97.9% vs 89.1%, P = 0.01). In semiquantitative analysis, the SUVmax and TBR of intrahepatic lesions on 18F-FAPI PET/CT were both higher than those on 18F-FDG PET/CT (all p < 0.01). Although in lymph node and peritoneal metastasis, the SUVmax on 18F-FAPI PET/CT was not significantly higher than those on 18F-FDG PET/CT (all p > 0.05), the TBR on 18F-FAPI PET/CT was higher than those on 18F-FDG PET/CT (all p < 0.01).

In our study, we demonstrated that 18F-FDG is less effective than 18F-FAPI in displaying intrahepatic lesions, which was consistent with previous research results [3, 12–14, 18]. The uptake of 18F-FDG in malignant tumors largely depends on the presence of facilitated glucose transporters, including type 1 (Glut 1), while Glut 1 is rarely expressed in HCC [7, 21]. Therefore, 18F-FDG PET/CT was not recommended for detecting HCC. FAP is overexpressed in CAFs of 90% epithelial carcinomas [10], including HCC, and liver background uptake is low on 18F-FAPI PET/CT [18]. Therefore, 18F-FAPI PET/CT is superior to 18F-FDG PET/CT in detecting intrahepatic lesions. Futhermore, our study compared 18F-FDG and 18F-FAPI for HCC patients with different T stages, the ability of 18F-FAPI PET/CT to display intrahepatic lesions was better than that of 18F-FDG PET/CT among patients with T2-T4 stages, and 18F-FAPI PET/CT showed significantly higher TBR and similar SUVmax in patients with T1 stage. The above results suggest that 18F-FAPI PET/CT can improve the ability to detect HCC lesions. In the LI-RADS classification, the diagnosis of HCC lesion with diameter ≤ 2 cm was difficult, and at least two typical imaging manifestations of HCC on ce-CT/ce-MRI/US were required to grade LR-4 [22]. Our results also demonstrated that in addition to LI-RADS, 18F-FAPI PET/CT can provide more information by detecting more HCC lesions ≤ 2 cm than 18F-FDG PET/CT (88.1% (97/110) vs. 25.5% (28/110), P < 0.0001).

Although lymph node metastasis is not common in HCC, it represents the aggressive biological behavior of HCC with poor prognosis [23, 24]. It has been reported that FDG PET/CT is superior to conventional evaluations in detecting occult metastases in patients with invasive HCC. The accuracy of conventional imaging in the diagnosis of lymph node metastasis (short diameter of lymph node ≥ 1 cm] was less than 50% [25]. In visual analysis, our study showed that 18F-FAPI PET/CT detected a little more lymph node metastasis than 18F-FDG PET/CT. In semi-quantitative analysis, the SUVmax of lymph node metastasis on 18F-FAPI PET/CT was not significantly higher than that on 18F-FDG PET/CT, which could be attributed to HCC that metastasizes to lymph nodes is more aggressive and usually requires more FDG. However, the TBR on 18F-FAPI PET/CT was higher than that of 18F-FDG PET/CT, which can increase our diagnosis confidence of lymph node metastasis. In additionally, two histology-confirmed inflammatory lymph nodes in paratracheal show 18F-FDG false-positive uptake but 18F-FAPI negative uptake, intended that 18F-FAPI showed the potential ability to differentiate metastatic and nonmetastatic lymph nodes, which was consistent with previous research results [26, 27].

Lung is the most common extrahepatic metastasis site of HCC [28]. Once Lung metastasis occurred in HCC, the patient would be classified into advanced stage and require systemic treatment [1]. In visual analysis and semi-quantitative analysis, 18F-FAPI PET/CT and 18F-FDG PET/CT showed similar performance on lung metastasis. The background of lung on 18F-FAPI PET/CT is as low as that of 18F-FDG PET/CT. Besides, in our study, the diameter of more than half of lung metastasis were less than 1 cm, which may lead to less radiopharmaceuticals uptake.

With regard to macrovascular invasion and bone metastasis, the number of lesions detected by 18F-FDG PET/CT was higher than that of 18F-FAPI PET/CT, and the SUVmax and TBR on 18F-FDG PET/CT were higher than those on 18F-FAPI PET/CT. Several studies have proved that HCC with higher FDG uptake usually displays more aggressive biological behavior [29–31]. The exist of macro and microvascular invasion provide the route for tumor cells to access the portal or systemic circulation, have correlation with the presences of distant metastases [32]. And both macrovascular invasion and distant metastases were the indicator of the aggressiveness of the primary HCC [33, 34]. Although 18F-FDG PET/CT is less sensitive in detecting intrahepatic lesions of HCC, it is valuable in detecting macrovascular invasion and bone metastasis. In addition, our study only found one adrenal metastasis lesion which detected both on 18F-FAPI PET/CT and 18F-FDG PET/CT with equivalent uptake.

In this study, 18F-FAPI PET/CT identified more intrahepatic lesions, lymph node metastases and peritoneal metastases than 18F-FDG PET/CT in HCC, especially in intrahepatic lesions, and upgraded the T staging in 12 patients. Although 18F-FDG PET/CT had advantage in detecting macrovascular invasion and bone metastasis, there was no change in the staging of patients. Therefore, compared with 18F-FDG PET/CT, 18F-FAPI PET/CT has a greater impact on the initial staging of HCC patients. In addition, in this study, half of the HCC patients (4/8) for restaging found recurrent lesions on 18F-FAPI PET/CT, which were negative on 18F-FDG PET/CT. Therefore, 18F-FAPI PET/CT may demonstrated great value for HCC patients staging and restaging.

Our research also has some limitations. First of all, lymph node metastasis and distant metastasis were followed up by imaging, without pathological results. Secondly, the sample size of distant metastatic lesions is small, the diagnostic value of 18F-FAPI PET/CT and 18F-FDG PET/CT for HCC in distant metastatic lesions needs to be further explored with a larger sample size. Thirdly, 18F-FAPI is not as widely used as 68 Ga-FAPI, and more research is needed to confirm its reliability.

Conclusion

In summary, This prospective study confirmed that 18F-FAPI PET/CT is a promising technique in staging of HCC and is complementary to 18F-FDG PET/CT. 18F-FAPI PET/CT had advantages in detecting intrahepatic lesions, lymph node metastasis and peritoneal metastasis compared to 18F-FDG PET/CT, which is helpful to improve the clinical management of HCC patients.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1: Supplementary Fig. 1. (a & b) Comparison of SUVmax and TBR values in different primary tumor staging groups between 18F-FDG and 18F-FAPI PET. (c & d) Comparison of SUVmax and TBR values in different sizes of intrahepatic lesions between 18F-FDG and 18F-FAPI PET. (e & f) Comparison of SUVmax and TBR values in metastatic lymph node with different short diameters (≤ 1 cm or > 1 cm) between 18F-FDG and 18F-FAPI PET. (g) Compare the performance of 18F-FDG and 18F-FAPI PET in detecting extrahepatic lesions, involved lymph nodes, lung, bone peritoneal and adrenal gland metastases. ns = no significant; *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001; ****P < 0.0001. Table S1. Patient characteristics and 18F-FDG/18F-FAPI PET/CT imaging findings for the 67 patients

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- CAFs

Cancer-associated fibroblasts

- FAPI

Fibroblast activation protein inhibitor

- FDG

Fluorodeoxyglucose

- HCC

Hepatocellular carcinoma

- TBR

Tumor-to-background ratio

- PET/CT

Positron emission tomography/computed tomography

- SUVmax

Maximum standardized uptake value

Authors’ contributions

LQZ contributed to the conception and design of the study, and study supervision; JZ, SQJ and MSL contributed to data-collection, analysis and interpretation of data, writing, and revising the manuscript; HBX, XZ, SYL, HP, JCL, ZDL, SQR, HPC and ZWC contributed to data-collection; YFG and GSC contributed to revising the manuscript; RSZ contributed to study supervision; all authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No.82101994) and Affiliated Cancer Hospital & Institute of Guangzhou Medical University Clinical Research 5555 Program [No. IIT-2022–015(HYX)].

Availability of data and materials

All the data generated and analyzed during this study are included in our manuscript. The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was performed in line with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. Approval was granted by the Ethics Committee of Affiliated Cancer Hospital & Institute of Guangzhou Medical University.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Jing Zhang, Shuqin Jiang and Mengsi Li contributed equally to this work.

Contributor Information

Rusen Zhang, Email: zhangrusen2015@163.com.

Linqi Zhang, Email: zhanglinqi0909@163.com.

References

- 1.Villanueva A. Hepatocellular carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2019;380:1450–1462. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1713263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kesler M, Levine C, Hershkovitz D, et al. (68)Ga-PSMA is a novel PET-CT tracer for imaging of hepatocellular carcinoma: A prospective pilot study. J Nucl Med. 2019;60:185–191. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.118.214833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shi X, Xing H, Yang X, et al. Comparison of PET imaging of activated fibroblasts and (18)F-FDG for diagnosis of primary hepatic tumours: a prospective pilot study. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2021;48:1593–1603. doi: 10.1007/s00259-020-05070-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hirmas N, Leyh C, Sraieb M, et al. (68)Ga-PSMA-11 PET/CT improves tumor detection and impacts management in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. J Nucl Med. 2021;62:1235–1241. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.120.257915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Park JW, Kim JH, Kim SK, et al. A prospective evaluation of 18F-FDG and 11C-acetate PET/CT for detection of primary and metastatic hepatocellular carcinoma. J Nucl Med. 2008;49:1912–1921. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.108.055087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kunikowska J, Cieslak B, Gierej B, et al. [(68) Ga]Ga-Prostate-Specific Membrane Antigen PET/CT: a novel method for imaging patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2021;48:883–892. doi: 10.1007/s00259-020-05017-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lee JD, Yang WI, Park YN, et al. Different glucose uptake and glycolytic mechanisms between hepatocellular carcinoma and intrahepatic mass-forming cholangiocarcinoma with increased 18F-FDG Uptake. J Nucl Med. 2005;46:1753–1759. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Asman Y, Evenson AR, Even-Sapir E, Shibolet O. 18F-fludeoxyglucose positron emission tomography and computed tomography as a prognostic tool before liver transplantation, resection, and loco-ablative therapies for hepatocellular carcinoma. Liver Transpl. 2015;21:572–580. doi: 10.1002/lt.24083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rettig WJ, Chesa PG, Beresford HR, et al. Differential expression of cell surface antigens and glial fibrillary acidic protein in human astrocytoma subsets. Cancer Res. 1986;46:6406–6412. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Boulter L, Bullock E, Mabruk Z, Brunton VG. The fibrotic and immune microenvironments as targetable drivers of metastasis. Br J Cancer. 2021;124:27–36. doi: 10.1038/s41416-020-01172-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kratochwil C, Flechsig P, Lindner T, et al. (68)Ga-FAPI PET/CT: Tracer Uptake in 28 Different Kinds of Cancer. J Nucl Med. 2019;60:801–805. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.119.227967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Guo W, Pang Y, Yao L, et al. Imaging fibroblast activation protein in liver cancer: a single-center post hoc retrospective analysis to compare [(68)Ga]Ga-FAPI-04 PET/CT versus MRI and [(18)F]-FDG PET/CT. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2021;48:1604–1617. doi: 10.1007/s00259-020-05095-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Siripongsatian D, Promteangtrong C, Kunawudhi A, et al. Comparisons of quantitative parameters of ga-68-labelled fibroblast activating protein inhibitor (FAPI) PET/CT and [(18)F]F-FDG PET/CT in patients with liver malignancies. Mol Imaging Biol. 2022;24:818–829. doi: 10.1007/s11307-022-01732-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang H, Zhu W, Ren S, et al. (68)Ga-FAPI-04 Versus (18)F-FDG PET/CT in the detection of hepatocellular carcinoma. Front Oncol. 2021;11:693640. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2021.693640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Li Y, Lin X, Li Y, et al. Clinical Utility of F-18 Labeled Fibroblast Activation Protein Inhibitor (FAPI) for primary staging in lung adenocarcinoma: a prospective study. Mol Imaging Biol. 2022;24:309–320. doi: 10.1007/s11307-021-01679-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fu L, Huang S, Wu H, et al. Superiority of [(68)Ga]Ga-FAPI-04/[(18)F]FAPI-42 PET/CT to [(18)F]FDG PET/CT in delineating the primary tumor and peritoneal metastasis in initial gastric cancer. Eur Radiol. 2022;32:6281–6290. doi: 10.1007/s00330-022-08743-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hu K, Wang L, Wu H, et al. [(18)F]FAPI-42 PET imaging in cancer patients: optimal acquisition time, biodistribution, and comparison with [(68)Ga]Ga-FAPI-04. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2022;49:2833–2843. doi: 10.1007/s00259-021-05646-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhang J, He Q, Jiang S, et al. [18F]FAPI PET/CT in the evaluation of focal liver lesions with [18F]FDG non-avidity. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2023;50:937–950. doi: 10.1007/s00259-022-06022-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Scialpi M, Palumbo I, Gravante S, et al. FDG PET and split-bolus multi-detector row CT fusion imaging in oncologic patients: preliminary results. Radiology. 2016;278:873–880. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2015150151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Amin MB, Edge SB, Greene FL, et al. eds. AJCC Cancer staging manual, 8th ed. New York: Springer International Publishing: American Joint Commission on Cancer. 2017; 287–294.

- 21.Paudyal B, Oriuchi N, Paudyal P, et al. Clinicopathological presentation of varying 18F-FDG uptake and expression of glucose transporter 1 and hexokinase II in cases of hepatocellular carcinoma and cholangiocellular carcinoma. Ann Nucl Med. 2008;22:83–86. doi: 10.1007/s12149-007-0076-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chernyak V, Fowler KJ, Kamaya A, et al. Liver imaging reporting and data system (LI-RADS) version 2018: imaging of hepatocellular carcinoma in at-risk patients. Radiology. 2018;289:816–830. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2018181494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ma J, Chen XQ, Xiang ZL. Identification of a prognostic transcriptome signature for hepatocellular carcinoma with lymph node metastasis. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2022;2022:7291406. doi: 10.1155/2022/7291406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chen X, Lu Y, Shi X, et al. Development and validation of a novel model to predict regional lymph node metastasis in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. Front Oncol. 2022;12:835957. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2022.835957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ercolani G, Grazi GL, Ravaioli M, et al. The role of lymphadenectomy for liver tumors: further considerations on the appropriateness of treatment strategy. Ann Surg. 2004;239:202–209. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000109154.00020.e0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhou X, Wang S, Xu X, Meng X, Zhang H, Zhang A, et al. Higher accuracy of [68 Ga]Ga-DOTA-FAPI-04 PET/CT comparing with 2-[18F]FDG PET/CT in clinical staging of NSCLC. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2022;49:2983–2993. doi: 10.1007/s00259-022-05818-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wang L, Tang G, Hu K, et al. Comparison of 68Ga-FAPI and 18F-FDG PET/CT in the evaluation of advanced lung cancer. Radiology. 2022;303:191–199. doi: 10.1148/radiol.211424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Uka K, Aikata H, Takaki S, et al. Clinical features and prognosis of patients with extrahepatic metastases from hepatocellular carcinoma. World J Gastroenterol. 2007;13:414–420. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v13.i3.414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lee JW, Paeng JC, Kang KW, et al. Prediction of tumor recurrence by 18F-FDG PET in liver transplantation for hepatocellular carcinoma. J Nucl Med. 2009;50:682–687. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.108.060574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sabate-Llobera A, Mestres-Marti J, Reynes-Llompart G, et al. 2-[(18)F]FDG PET/CT as a Predictor of Microvascular Invasion and High Histological Grade in Patients with Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Cancers (Basel) 2021;13:2554. doi: 10.3390/cancers13112554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hyun SH, Eo JS, Song B, et al. Preoperative prediction of microvascular invasion of hepatocellular carcinoma using (18)F-FDG PET/CT: a multicenter retrospective cohort study. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2018;45:720–726. doi: 10.1007/s00259-017-3880-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yoneda N, Matsui O, Kobayashi S, et al. Current status of imaging biomarkers predicting the biological nature of hepatocellular carcinoma. Jpn J Radiol. 2019;37:191–208. doi: 10.1007/s11604-019-00817-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lee JW, Hwang SH, Kim HJ, Kim D, Cho A, Yun M. Volumetric parameters on FDG PET can predict early intrahepatic recurrence-free survival in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma after curative surgical resection. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2017;44:1984–1994. doi: 10.1007/s00259-017-3764-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Uchino K, Tateishi R, Shiina S, et al. Hepatocellular carcinoma with extrahepatic metastasis: clinical features and prognostic factors. Cancer. 2011;117:4475–4483. doi: 10.1002/cncr.25960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional file 1: Supplementary Fig. 1. (a & b) Comparison of SUVmax and TBR values in different primary tumor staging groups between 18F-FDG and 18F-FAPI PET. (c & d) Comparison of SUVmax and TBR values in different sizes of intrahepatic lesions between 18F-FDG and 18F-FAPI PET. (e & f) Comparison of SUVmax and TBR values in metastatic lymph node with different short diameters (≤ 1 cm or > 1 cm) between 18F-FDG and 18F-FAPI PET. (g) Compare the performance of 18F-FDG and 18F-FAPI PET in detecting extrahepatic lesions, involved lymph nodes, lung, bone peritoneal and adrenal gland metastases. ns = no significant; *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001; ****P < 0.0001. Table S1. Patient characteristics and 18F-FDG/18F-FAPI PET/CT imaging findings for the 67 patients

Data Availability Statement

All the data generated and analyzed during this study are included in our manuscript. The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.