Abstract

The presence of a viable competitive microflora at cell densities of 108 CFU ml−1 protects an underlying population of 105 CFU of Salmonella typhimurium ml−1 against freeze injury. The mechanism of enhanced resistance was initially postulated to be via an RpoS-mediated adaptive response. By using an spvRA::luxCDABE reporter we have shown that although the onset of RpoS-mediated gene expression was brought forward by the addition of a competitive microflora, the time taken for induction was measured in hours. Since the protective effect of a competitive microflora is essentially instantaneous, the stationary-phase adaptive response is excluded as the physiological mechanism. The only instantaneous effect of the competitive microflora was a reduction in the percent saturation of oxygen from 100% to less than 10%. For both mild heat treatment (55°C) and freeze injury this change in oxygen tension affords Salmonella a substantive (2 orders of magnitude) enhancement in survival. By reducing the levels of dissolved oxygen through active respiration, a competitive microflora reduces oxidative damage to exponential-phase cells irrespective of the inimical treatment. These results have led us to propose a suicide hypothesis for the destruction of rapidly growing cells by inimical processes. In essence, the suicide hypothesis proposes that a mild inimical process leads to the growth arrest of exponential-phase cells and to the decoupling of anabolic and catabolic metabolism. The result of this is a free radical burst which is lethal to unadapted cells.

Predictive models for bacterial survival currently fail to consider the physiological and molecular significance of a competitive microflora on the adaptive response of food-borne pathogens. We have recently demonstrated that the presence of a competitive microflora protects Salmonella typhimurium from heating at 55°C. Decimal reduction times for 105 CFU of exponential-phase Salmonella ml−1 increased from 0.4 to 2.09 min in the presence of a competitive flora at 108 CFU ml−1, indicating a significant protective effect (7). Since a high cell density of the competitive microflora (108 CFU ml−1) is critical for the protective effect, the stationary phase may be induced in the Salmonella cells. The stationary-phase sigma factor RpoS (ςs) controls the expression of a multitude of genes which confer enhanced resistance to inimical processes including thermotolerance (10), resistance to oxidative stress (14), starvation (17), and osmotic stress (17). We therefore proposed that the mechanism for protection was by induction of RpoS in the underlying Salmonella population (7).

In order to assess the validity of the above hypothesis, we have employed a lux-based reporter to evaluate RpoS activity in S. typhimurium challenged with various concentrations of a competitive microflora. In addition we have sought to determine the effect of a competitive microflora on the resistance of S. typhimurium to freeze injury, thus extending our previous studies into different inimical processes.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains used.

The bacterial strains and plasmids used are given in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Strains and plasmids used

| Strain or plasmid | Characteristic or phenotype and source |

|---|---|

| Salmonella typhimurium LT2 | Prototrophic laboratory strain (rpoS+) |

| Escherichia coli BJ4 | Wild-type isolate (13) (rpoS+) |

| Escherichia coli BJ4 L1 | Isogenic with E. coli BJ4, except for Tn10 inserted into rpoS (13) (rpoS−) |

| Escherichia coli FSAC EJa1 | Wild type from a poultry processing factory |

| Citrobacter freundii CH.IS 3.6 | Wild type from raw chicken |

| Pseudomonas fluorescens EMMA-1 | Wild type from fish |

| pSB100 | Photobacterium fischeri luxAB placed under the control of a clostridial promoter in pHG165 (3) |

| pSB230 | Vibrio harveyi luxAB cloned into pHG177 under the control of a clostridial promoter (11) |

| pSB367 | A transcriptional fusion of Salmonella dublin spvRA with Photorhabdus luminescens luxCDABE in pUC18 (24); since functional RpoS is required for expression of the spv operon (5), this biosensor measures the activity of RpoS on a target gene via bioluminescence |

RpoS-mediated gene expression.

Overnight cultures of Escherichia coli FSAC EJa1 and Citrobacter freundii, grown in Luria-Bertani broth (LB) (Lennox) (16) at 37°C, were inoculated into fresh LB and incubated at 37°C with shaking at 200 rpm in an orbital incubator (Gallenkamp, Loughborough, United Kingdom). Pseudomonas fluorescens was inoculated into LB and incubated at 30°C with shaking. Once an A600 of 0.6 (Visi-Spec; Gallenkamp) was reached, the cultures were centrifuged at 20,000 × g and ambient temperature for 5 min in a Beckman J2-21 centrifuge (Beckman Instruments Inc., Glenrothes, United Kingdom). The cell pellets were resuspended with 10 ml of fresh LB and mixed. S. typhimurium LT2 cultures were prepared as above but not pooled with the other competitors. Heat-killed competitors were prepared by heating to 80°C with regular mixing in a Toshiba ER-674 600-W microwave oven (Toshiba Corp., Tokyo, Japan) and then allowed to cool before being centrifuged and resuspended as above to an A600 equivalent to 108 CFU ml−1.

The working cultures of S. typhimurium LT2(pSB367) were cycled through growth in the early exponential phase to ensure maximum repression of RpoS-mediated gene expression. An overnight culture was inoculated into fresh LB supplemented with 50 μg of ampicillin ml−1 (LB-amp50) (Sigma Chemical Co., Poole, United Kingdom) and incubated at 37°C with shaking to an A600 of 0.2, when it was diluted 1:10 into fresh LB-amp50 and incubated to an A600 of 0.2. The culture was again diluted 1:10 into fresh LB-amp50 and then incubated until the A600 was 0.6 and centrifuged at 20,000 × g and ambient temperature for 5 min. The pellet was resuspended with 10 ml of fresh LB.

Cultures were mixed to give a final density of 105 CFU of S. typhimurium LT2(pSB367) ml−1 and from 105 to 108 CFU of viable competitors ml−1 mixed in equal proportions, or parental S. typhimurium, or an equivalent density of heat-killed competitors. S. typhimurium LT2(pSB367) at 105 CFU ml−1 without added competitors served as the control culture. Cultures were incubated at 37°C with shaking; the A600 and bioluminescence (Turner Designs TD-20e luminometer, Turner Designs Inc., Mt. View, Calif.) were monitored at 30-min intervals. The initial viable count was confirmed by the method of Miles and Misra (19).

Freeze injury.

Mixed viable competitor cultures were prepared as above except that the cells were resuspended with 0.1% peptone water (Oxoid Ltd., Basingstoke, United Kingdom) to a density of 108 CFU ml−1, and the suspensions were subsequently combined. Heat-killed competitor suspensions were also prepared as above. An overnight culture of S. typhimurium LT2(pSB100) (Table 1) was diluted 1:100 into LB-amp50 and grown at 30°C with shaking to an A600 of 0.6. This culture was then diluted 1:1,000 either into sterile 0.1% peptone water or the competitor suspensions prepared as above, to give a final S. typhimurium concentration of 105 CFU ml−1 in a volume of 50 ml. After 1 h of incubation at 30°C, an 8-ml volume (termed the experimental culture) was removed and frozen to −20°C (at 10°C min−1) with a Planer Kryo 10/16 programmable freezing chamber (Planer Products Ltd., Sunbury-on-Thames, United Kingdom) and held at this temperature for 45 min. Following freezing, the culture was thawed at 30°C in a Stratus thermostatic water bath (Northern Media, Hessle, United Kingdom). Incubation of the remainder of the 50-ml culture (termed the control culture) continued at 30°C throughout. At the end of the freeze-thaw cycle both the experimental and control cultures were diluted 1:10 into fresh LB and incubated at 30°C. Cell density was monitored during the experiment by periodic measurement of bioluminescence (Turner Designs TD-20e luminometer) after addition of 10 μl of 1% dodecanal in ethanol ml−1 (Aldrich Chemical Co. Ltd., Gillingham, United Kingdom). Viable counts were also determined at intervals (19) to substantiate the bioluminescence data.

Cultures of Escherichia coli BJ4(pSB230) and E. coli BJ4 L1(pSB230) (Table 1) were also prepared, mixed with competitors, and frozen in the same manner as the Salmonella culture. The subsequent survival of both E. coli cultures was assayed as for Salmonella.

Measurement of percent oxygen saturation.

An oxygen electrode (YSI Model 52 Dissolved Oxygen Meter; YSI Inc., Yellow Springs, Ohio) was calibrated in air-saturated water as specified by the manufacturer. The percent oxygen saturation of LB containing 105 CFU of S. typhimurium ml−1 was then determined at 10-s intervals for 1 min. The effect of adding the competitive microflora at the specified cell densities was then determined.

RESULTS

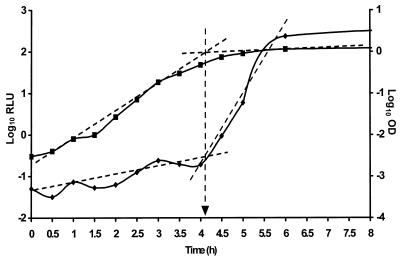

By using an spvRA::luxCDABE reporter, we have correlated the point of induction of RpoS-mediated gene expression in S. typhimurium with the growth phase (Fig. 1). The inflection point for bioluminescence induction correlated precisely with the inflection point for the transition between exponential and stationary phase of growth. These inflection points define a unique time on the x axis, which we have termed the RpoS induction time (Fig. 1). In the absence of competitors, the RpoS induction time for S. typhimurium LT2(pSB367) was 4 h 6 min (Table 2) following initiation of the culture at 105 CFU ml−1. To assess the effect of a mixed competitive microflora on the RpoS induction time, a range of cell concentrations from 105 to 108 CFU ml−1 was added to the underlying Salmonella population of 105 CFU ml−1. Induction times were not significantly different from the axenic control when 105 or 107 CFU of competitors ml−1 was incorporated with the Salmonella culture. In contrast 108 CFU of competitors ml−1 induced bioluminescence after only 2 h, representing a significant (P < 0.02, Student’s t test) decrease in the time for induction of RpoS-mediated gene expression (Table 2). Addition of parental S. typhimurium LT2 to S. typhimurium LT2(pSB367) had an effect identical to that of the mixed heterologous competitors (Table 2). Thus, the composition of the competitive microflora is not important in producing the effect. When the competitive microflora was heat-killed prior to mixing with the Salmonella culture, none of the cell densities employed led to a significant decrease in induction times compared with the axenic control (Table 2). Metabolic activity is therefore a requirement for the competitive microflora to induce the early onset of the RpoS-mediated adaptive response in exponential-phase Salmonella. This is reflected in the times for RpoS induction (Table 2), where the more vigorously growing heterologous competitors achieved stationary phase from 107 CFU ml−1 more rapidly than the autologous competitors. A minimum of 2 h postaddition of competitors is required, however, before this RpoS induction occurs. This time is much greater than the exposure time allowed by Duffy et al. (7) between addition of competitors and exposure to the heating process. RpoS induction cannot therefore be used to explain the protective effect of competitors on heat injury.

FIG. 1.

The induction of RpoS as measured by an spvRA::luxCDABE reporter in S. typhimurium LT2. Induction time for RpoS was derived from the intersection of lines drawn through the stationary and exponential portions of the growth (▪, log10 optical density [OD]) and bioluminescence (⧫, log10 relative light unit [RLU]) curves.

TABLE 2.

Mean time (± 1 standard deviation) for RpoS-mediated induction of spvRA::luxCDABE in S. typhimurium LT2(pSB367)a

| Experimental culture | Mean time at competitor culture density (CFU

ml−1) of:

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 105 | 107 | 108 | |

| 105S. typhimurium CFU ml−1 plus viable heterologous competitors | 4 h 6 min (± 6 min) | 4 h 2 min (± 6 min) | 2 h 36 min (± 23 min) | 2 h (± 18 min) |

| 105S. typhimurium CFU ml−1 plus viable autologous competitors | 3 h 50 min (± 5 min) | 3 h 54 min (± 7 min) | 3 h 43 min (± 9 min) | 2 h 9 min (± 4 min) |

| 105S. typhimurium CFU ml−1 plus heat-killed heterologous competitorsb | 4 h (± 27 min) | 4 h (± 15 min) | 3 h 53 min (± 21 min) | 4 h 6 min (± 25 min) |

The induction times for RpoS-mediated gene expression were determined as described in the legend to Fig. 1. In each case, n = 3.

The heat-killed competitors were resuspended to an A600 equivalent to the desired viable competitor density.

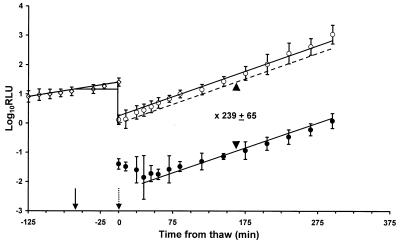

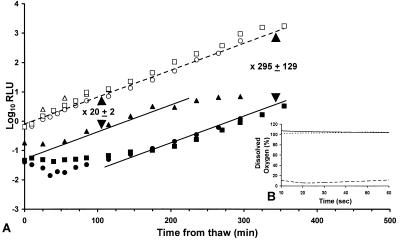

Before generating alternate explanations, it was important to establish whether the effect of competitors on Salmonella was uniquely associated with heat as an inimical process. Freeze-thaw is known to cause a reduction in the survival of S. typhimurium and has been studied previously using bioluminescence as a monitor of cell viability (8). We have extended the studies of Ellison et al. (8) to determine the effect of a competitive microflora upon survival of S. typhimurium following freeze injury. Figure 2 shows the effect of freezing from 30 to −20°C at a rate of −10°C min−1, and subsequent thaw, on the survival of 105 CFU ml−1 of S. typhimurium LT2(pSB100). The data are presented as previously described (8), with the control adjusted to allow for its continued growth during treatment of the experimental culture. Percent survival was calculated from the difference between the experimental and adjusted control growth curves. When no competitors were present, 0.42% (± 0.13%) of the Salmonella population survived freeze-thaw, representing a 239-fold reduction in viability (Fig. 2). This level of survival compares favorably with a value of 0.86% previously reported (8). Addition of a mixed competitive flora at 108 CFU ml−1 significantly (P < 0.05, Student’s t test) increased the survival of an underlying population of 105 CFU of S. typhimurium ml−1 to 4.9% (± 0.53%) (Fig. 3A). The protective effect of competitors requires that they have an active metabolism since in the presence of heat-killed competitors only 0.27% (± 0.09%) of the experimental culture survived. This is a value statistically equivalent to survival in the absence of competitors (Fig. 3A).

FIG. 2.

Survival of S. typhimurium LT2(pSB100) after freeze-thaw without competitors. The dashed line represents the control adjusted to subtract the growth which occurred during freezing of the experimental sample. ◊, growth in 0.1% peptone water; ○, control culture incubated in LB; •, experimental culture subjected to freezing; ▾|, samples frozen; ▾⋮, samples thawed. At time zero, all samples were diluted 1:10 into LB. The difference in survival between the control and freeze-thawed cultures was determined from the lines of best fit. A 239- ± 65-fold drop in viability represents the survival of 0.42% (± 0.13%) of the original cell number. Each point represents the mean of three independent replicates; the error bars represent 1 standard deviation from the mean.

FIG. 3.

Survival of S. typhimurium LT2(pSB100) after freeze-thaw without competitors (○, •), in the presence of 108 CFU of viable competitors ml−1 (▵, ▴) and in the presence of heat-killed competitors (□, ▪). Open symbols represent control cultures, while filled symbols represent the experimental cultures. ----, adjusted controls. The lines of best fit are through points which represent the mean of three independent replicates and take account of error bars with one standard deviation. For clarity the error bars are not shown. The data for ▵ after 150 min are not presented as the cultures entered stationary phase. Since there is no statistical difference between the Salmonella populations without competitors (circles) or in the presence of heat-killed competitors (squares), the dashed and solid lines show the means of both data sets. The inclusion of a viable competitive microflora increases the survival of S. typhimurium from 0.34% (± 0.13%) (•, ▪) to 4.9% (± 0.53%) (▴). (B) The percent dissolved oxygen in cultures of 105 CFU of S. typhimurium LT2 ml−1, alone ( ) or in the presence of 107 CFU of viable competitors ml−1 (.....) or 108 CFU of viable competitors ml−1 (----).

The contact time required between the competitive microflora and the Salmonella before the protective effect is manifested was examined. No significant difference was observed between a contact time of 1 h (Fig. 3A) and addition of competitors immediately prior to freezing (data not shown). In contrast to the induction of RpoS, therefore, the protective effect is conferred extremely rapidly.

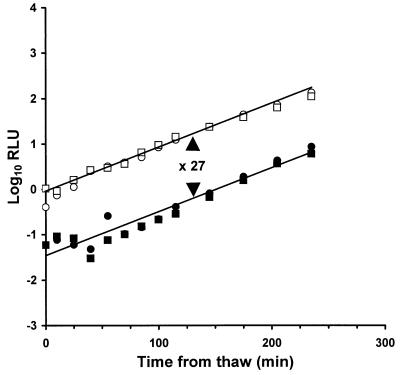

To confirm that RpoS plays no role in the enhanced resistance provided by a competitive microflora, an E. coli mutant defective in rpoS was assessed for its resistance to freeze-thaw as compared to both a wild-type E. coli and to S. typhimurium LT2. In the presence of 108 CFU of viable competitors ml−1, 3.9% of E. coli BJ4 (wild-type RpoS) and 4.2% of E. coli BJ4 L1 (RpoS insertion mutant) survived the freeze-thaw treatment (Fig. 4). E. coli clearly shows a level of protection similar to that conferred on Salmonella (4.9%), and there is no difference in survival for E. coli lacking rpoS.

FIG. 4.

Survival of E. coli BJ4(pSB100) (○, •) and of RpoS− E. coli BJ4 L1(pSB100) (□, ▪) after freeze-thaw in the presence of 108 CFU of viable competitors ml−1. Open symbols represent the control cultures, while filled symbols represent the experimental cultures. Since there is no statistical difference between the E. coli populations, the lines show the means of both. The mean difference between the control and experimental cultures is 27-fold, equivalent to 4.06% survival.

From the above, factors other than adaptive gene expression must be responsible for the instantaneous protection afforded to Salmonella by the competitive microflora. The requirement for viable competitors dictates a physiological response as the basis for the protective effect. There are, however, few physiologically mediated processes that could elicit such a rapid change in the environment surrounding the underlying Salmonella population. Since the competitors were derived from an exponential-phase population and would be respiring actively, their potential to produce a rapid depletion in oxygen tension was examined as the basis for the protective effect. Figure 3B shows that the percent dissolved oxygen for a culture of S. typhimurium at 105 CFU ml−1 is 100%. The addition of 107 CFU of competitors ml−1 does not affect the percent dissolved oxygen. The addition of 108 CFU ml−1, however, reduced the percentage of dissolved oxygen to 10% and below, at a rate that was higher than the resolution time of the experiment (10 s).

DISCUSSION

Before accurate models can be developed, predictive microbiology requires a sound basis of observed results and an understanding of the factors that contribute to the death of bacterial cells. Previous studies have shown that growth phase, medium composition, and subculturing after primary isolation are all important influences to be considered when attempting to extrapolate results from pure cultures to real food systems subjected to treatments such as freeze-thaw (23). In most foods bacteria are present as a complex microflora, and the influence of this microflora on the recovery of small populations of food pathogens is largely unstudied. Certainly the influence of a competitive microflora is not currently considered in predictive models for the survival of food-borne pathogens of inimical processes (18). We have recently shown that high levels of a competitive microflora will protect S. typhimurium against thermal inactivation (7). In the present study, we have demonstrated an equivalent protective effect for freeze-injury. The levels of inimical treatment used in these studies were sublethal to stationary-phase cells but lethal to exponential-phase cells (8). The effect of the competitive microflora was to bring the level of resistance of exponential-phase cells up to that of stationary-phase cells. This initially led us to hypothesize a role for RpoS in mediating the protective effect, via the stationary-phase adaptive response.

RpoS-mediated gene expression was measured in the underlying Salmonella population by using a real-time assay for functional RpoS which relies upon bioluminescence as a reporter (24). In the pSB367 biosensor, the lux operon has been transcriptionally fused to the Salmonella virulence plasmid gene spvR and the spvA promoter, such that Salmonella transformed with pSB367 emits light only when sufficient intracellular RpoS has accumulated to trigger expression of spvRA (4, 24). Due to the many layers of posttranscriptional and posttranslational modification which regulate both RpoS availability and activity (2, 15, 21), the measurement of functional intracellular RpoS levels was deemed to be more representative than alternatives such as transcriptional or translational rpoS fusions or Western blots. Our results show that competitors do advance the onset of RpoS-mediated gene expression in an underlying population of Salmonella. This is compatible with previous observations that competitors can induce stationary phase (20) and also that growth of a marked subpopulation of salmonellae or E. coli will be retarded by a larger population of the same organism (1). The time frame for induction of RpoS-mediated gene expression is not, however, consistent with the observed protective effect. This effect is instantaneous and correlates with a very rapid reduction in oxygen tension mediated by the metabolic activity of the competitive microflora. The lack of a dose response for oxygen reduction with different competitor numbers may reflect the fact that, in a vigorously shaken culture, cells at a density of 108 CFU ml−1 are sufficiently metabolically active to displace the O2 equilibrium and create a deficit, whereas cells at a 10-fold lower density (107 CFU ml−1) are below the level capable of causing significant displacement of the equilibrium.

We propose that the removal of oxygen protects the Salmonella from oxidative damage. The reduction in oxygen tension provides a common mode of action for protection against two entirely different inimical processes, namely, heating and freeze-thaw. The oxidative damage cannot, therefore, be a direct action of the inimical process, but must be mediated by a common aspect of cellular metabolism. We have used this concept to develop a detailed hypothesis on the self-destruction of rapidly dividing cells, which we have termed the suicide response (6). We propose that self-destruction is caused by an oxidative burst which appears to result when exponentially growing cells are growth-arrested following an inimical treatment. Protection against self-destruction can be provided by reducing the oxygen tension or by the adaptive response associated with the stationary phase which protects the cell against DNA damage, free radical damage, and protein denaturation. The sensitivity of exponential-phase cells is due to the production of intracellular free radicals rather than to the direct physical action of the inimical process.

There is a trend among consumers to demand more natural, less processed foods (12). Consequently, this increases the possibility that the resident microflora will be sublethally injured following the inimical process (9, 22). The implications for the survival of pathogens and for the recovery of culturable organisms in food analysis may need to be reexamined once we fully understand the suicide response and the factors that enhance or reduce it.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by a Leverhulme Trust Fellowship (T.G.A.) and by a M.A.F.F. Studentship (R.L.S.).

We thank K. Krogfelt for providing E. coli BJ4 and BJ4 L1.

REFERENCES

- 1.Barrow P A, Lovell M A, Barber L Z. Growth suppression in early-stationary-phase nutrient broth cultures of Salmonella typhimurium and Escherichia coli is genus specific and not regulated by ςs. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:3072–3076. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.11.3072-3076.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barth M, Marschall C, Muffler A, Fischer D, Hengge-Aronis R. Role for the histone-like protein H-NS in growth phase-dependent and osmotic regulation of ςs and many ςs-dependent genes in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:3455–3464. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.12.3455-3464.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Blisset S J, Stewart G S A B. In vivo bioluminescent determination of apparent Km’s for aldehyde in recombinant bacteria expressing luxA/B. Lett Appl Microbiol. 1989;9:149–152. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chen C-Y, Buchmeier N A, Libby S, Fang F C, Krause M, Guiney D G. Central regulatory role for the RpoS sigma factor in expression of Salmonella dublinplasmid virulence genes. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:5303–5309. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.18.5303-5309.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Coynault C, Robbe-Saule V, Norel F. Virulence and vaccine potential of Salmonella typhimurium mutants deficient in the expression of the RpoS (ςs) regulon. Mol Microbiol. 1996;22:149–160. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1996.tb02664.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dodd C E R, Sharman R L, Bloomfield S F, Booth I R, Stewart G S A B. Inimical processes: bacterial self-destruction and sub-lethal injury. Trends Food Sci Technol. 1997;8:238–241. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Duffy G, Ellison A, Anderson W, Cole M B, Stewart G S A B. Use of bioluminescence to model the thermal inactivation of Salmonella typhimuriumin the presence of a competitive microflora. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1995;61:3463–3465. doi: 10.1128/aem.61.9.3463-3465.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ellison A, Perry S F, Stewart G S A B. Bioluminescence as a real-time monitor of injury and recovery in Salmonella typhimurium. Int J Food Microbiol. 1991;12:323–332. doi: 10.1016/0168-1605(91)90146-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hall H K, Foster J W. The role of Fur in the acid tolerance response of Salmonella typhimuriumis physiologically and genetically separable from its role in iron acquisition. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:5683–5691. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.19.5683-5691.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hengge-Aronis R, Klein W, Lange R, Rimmele M, Boos W. Trehalose synthesis genes are controlled by the putative sigma factor encoded by rpoS and are involved in stationary phase thermotolerance in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1991;173:7918–7924. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.24.7918-7924.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hill P J, Swift S, Stewart G S A B. PCR based gene engineering of the Vibrio harveyi lux operon and the Escherichia coli trpoperon provides for biochemically functional native and fused gene products. Mol Gen Genet. 1991;226:41–48. doi: 10.1007/BF00273585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Knøchel S, Gould G. Preservation microbiology and safety. Quo vadis? Trends Food Sci Technol. 1995;6:127–131. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Krogfelt K A, Poulsen L K, Molin S. Identification of coccoid Escherichia coliBJ4 cells in the large intestine of streptomycin-treated mice. Infect Immun. 1993;61:5029–5034. doi: 10.1128/iai.61.12.5029-5034.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lange R, Hengge-Aronis R. Identification of a central regulator of stationary phase gene expression in Escherichia coli. Mol Microbiol. 1991;5:49–59. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1991.tb01825.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Loewen P C, Hengge-Aronis R. The role of the sigma factor ςs(KatF) in bacterial global regulation. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1994;48:53–80. doi: 10.1146/annurev.mi.48.100194.000413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Maniatis T, Fritsch E F, Sambrook J. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; 1982. p. 68. [Google Scholar]

- 17.McCann M P, Kidwell J P, Matin A. The putative ς factor KatF has a central role in the development of starvation-mediated general resistance in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1991;173:4188–4194. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.13.4188-4194.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McClure P J, Blackburn C D, Cole M B, Curtis P S, Jones J E, Legan J D. Modelling the growth, survival and death of microorganisms in foods—the UK food micromodel approach. Int J Food Microbiol. 1994;23:265–275. doi: 10.1016/0168-1605(94)90156-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Miles A A, Misra S S. The estimation of the bactericidal power of the blood. J Hyg. 1938;38:732–749. doi: 10.1017/s002217240001158x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schiemann D A, Olson S A. Antagonism by gram-negative bacteria to growth of Yersinia enterocoliticain mixed cultures. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1984;48:539–544. doi: 10.1128/aem.48.3.539-544.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schweder T, Lee K-H, Lomovskaya O, Matin A. Regulation of Escherichia coli starvation sigma factor (ςs) by ClpXP protease. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:470–476. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.2.470-476.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Siegele D A, Kolter R. Life after log. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:345–348. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.2.345-348.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Smith M G. Survival of Escherichia coli and Salmonellaafter chilling and freezing in liquid media. J Food Sci. 1995;60:509–512. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Swift S, Stewart G S A B. Luminescence as a signal of spvA expression. In: Campbell A K, Kricka L J, Stanley P E, editors. Bioluminescence and chemiluminescence, fundamentals and applied aspects. New York, N.Y: John Wiley & Sons; 1994. pp. 93–96. [Google Scholar]