Abstract

Background:

Public health measures necessary to mitigate the spread of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) impacted lifestyles and health practices. This multiyear cohort analysis of U.S. working-aged adults aims to evaluate the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on metabolic syndrome and explores contributing factors.

Methods:

This longitudinal study (n = 19,543) evaluated year-to-year changes in metabolic syndrome and cardiometabolic risk factors through employer-sponsored annual health assessment before and during the COVID-19 pandemic using logistic mixed-effects model.

Results:

From prepandemic to pandemic (2019 to 2020), prevalence of metabolic syndrome increased by 3.5% for men and 3.0% for women, across all ethnic groups. This change was mainly driven by increased fasting glucose (7.3%) and blood pressure (5.2%). The increased risk of metabolic syndrome was more likely to occur in individuals with an elevated body mass index (BMI) combined with insufficient sleep or physical activity.

Conclusions:

Cardiometabolic risk increased during the COVID-19 pandemic compared with before the pandemic in a working-aged adult population, more so for those with a high BMI, unhealthy sleep, and low physical activity practices. Given this observation, identification of risk and intervention (including lifestyle and medical) is increasingly necessary to reduce the cardiovascular and metabolic risk, and improve working-aged population health.

Keywords: metabolic syndrome, employee health, blood pressure, prediabetes, health risk factors, workplace health

Introduction

Public health efforts necessary to mitigate the transmission of the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) had unintended and adverse consequences on health. While stay-at-home orders, site closures, and social distancing were necessary to mitigate the spread of COVID-19, emerging evidence1–4 suggests significant health consequences of the pandemic, beyond the virus itself. Fear of contracting the virus combined with government mandates created social isolation and impacted lifestyles, behaviors, and mental health.4 The impact of social isolation during the pandemic may be substantial, particularly regarding psychological consequences5 and cardiometabolic health.1,6,7

Cardiometabolic risk is prevalent in the U.S. population. Approximately 1/3 of U.S. adults have metabolic syndrome,8,9 a cluster of three or more of five cardiometabolic risk factors/metabolic dysregulations including insulin resistance, atherogenic dyslipidemia (high-density lipoprotein [HDL] cholesterol and triglycerides), central obesity, and hypertension.10

Metabolic syndrome is associated with increased risk of cardiovascular disease, diabetes,11 and all-cause mortality.11,12 It is costly to the health care system,13 as patients with metabolic syndrome cost ∼60% more per person per year, and ∼24% more per risk factor than those without metabolic syndrome.13 Importantly, metabolic syndrome is modifiable where cardiometabolic risk can be reduced with intervention. As cardiovascular disease is the leading cause of morbidity and mortality worldwide, understanding the population prevalence and associated risks is essential to reducing the disease burden.

The accumulation of stressful life events has been associated with obesity, insulin resistance, elevated triglycerides, and increased odds of having metabolic syndrome.14 Yet, the immediate impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on population cardiometabolic health is largely unknown. A recent systematic review suggests that COVID-19 has exacerbated risk factors for obesity and is likely to worsen obesity rates.15

Moreover, some data indicate disruptions in eating behaviors,4 physical activity,4 sleep,4 body weight, and blood pressure as a result of the pandemic period.1,4,16–18 The pandemic's impact on health has shown some evidence of disproportionately impacting some segments of the population, including women1 and individuals with obesity.4 Yet, what remains to be seen is whether this pandemic is exacerbating the growing metabolic disease burden. To date, no studies have assessed the direct impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on metabolic syndrome in a multiyear cohort of U.S. working-aged adults. Therefore, the objectives of this article are to fill in this gap by describing the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on metabolic syndrome and cardiometabolic risk, and to explore contributing factors in vulnerable segments of the population.

Methods

This retrospective longitudinal study included a cohort of 19,543 employees (81.3%) who remained working largely onsite to provide essential services during the pandemic period and their spouses/partners (18.7%)—working-aged adults—who completed an employer-sponsored annual health assessment operated by Quest Diagnostics, with year-end evaluations (September–November) in 2018, 2019, 2020, and 2021, which included biometric measurements, venipuncture blood draw, and a self-reported health risk questionnaire.

Preliminary analyses revealed no differences between employee and spouse/domestic partner participants in demographics (age, sex) and body mass index (BMI) distributions. Thus, both were included in the analysis to increase sample size. Three study periods were defined: prepandemic period (2018–2019), transition period from prepandemic to the first year of pandemic (2019–2020), and pandemic period (2020–2021); transition period was the focus for this study, with prepandemic and pandemic periods being two control periods to compare with the transition period. All participants were at least 18 years old in 2018, and all women who were pregnant during the study period were excluded from the study analysis.

A metabolic syndrome “score” was calculated for all participants in each year of the study. The score, on a scale from 0 to 5, indicated the number of abnormal/higher risk cardiometabolic risk factors: high fasting glucose (≥100 mg/dL), hypertension (systolic blood pressure [SBP] ≥130 mm/Hg or diastolic blood pressure [DBP] ≥85 mm/Hg), hypertriglyceridemia (≥150 mg/dL), large waist circumference (>35 inches for women; > 40 inches for men), and low HDL cholesterol (<50 mg/dL for women; <40 mg/dL for men).19 Being consistent with the current literature and industry standard, a participant with a metabolic syndrome “score” ≥3 was considered having metabolic syndrome in this study.

Sleep duration in hours per day and physical activity level per week were self-reported in a health risk assessment each year.

The probability of having metabolic syndrome (≥3 abnormal/higher risk cardiometabolic risk factors) versus ≤2 abnormal/higher risk cardiometabolic risk factors was compared between the 2 years in each of three study periods: prepandemic, transition period, and pandemic period. Probabilities were estimated in nested models by including additional covariates in a larger/outer model: adjusted for age and sex only (model 1), adding BMI to model 1 (model 2), adding race to model 2 (model 3), and adding sleep duration and weekly exercise level, one at a time, to model 3 (model 4).

For the main objectives of this study, probabilities from models 2 to 4 were only compared between 2019 and 2020 for the transition period. In addition to looking at 2-year clusters in the three periods as defined in the study design, a sensitivity analysis on model 1 (age and sex adjusted) with time variable including all 4 years was conducted to examine if a similar effect on the probability of metabolic syndrome was observed in the transition period (2019–2020).

The probability of having high-risk results in each of five cardiometabolic risk factors was estimated to determine the “dominant” factors that drove the observed differences in the probability of having metabolic syndrome, without and with adjustment for age and sex.

Logistic mixed-effects models for repeated measures were fitted to assess the adjusted effects of time (pandemic vs. prepandemic), age, sex, BMI, race, sleep duration, and exercise level on the outcomes, metabolic syndrome (score ≥3 versus score ≤2), and each of cardiometabolic risk factors (abnormal/higher risk results vs. normal/lower risk results). The SAS procedure NLMIXED was used to estimate the parameters and calculate the probability of the outcomes. P values <0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Statistical analyses were performed using SAS Studio 3.6 on SAS version 9.4. (Cary, NC). This study was deemed exempt by the WCG Institutional Review Board based on federal regulation 45 CFR Parts 46 and 164. The WCG Institutional Review Board is an independent ethical review board formed by the integration of the Western Institutional Review Board with Copernicus Group IRB, New England IRB, Aspire IRB, and Midlands IRB in 2020.

Results

A total of 19,543 participants met study criteria and were included in the analysis. In this study population, mean age in 2018 was 47.3 (±standard deviation [SD] 10.9) years, and 12,152 (62.2%) were women.

During the transition period, prevalence of metabolic syndrome (score ≥3) increased by 3.1% (19.7% to 22.8%) (P < 0.001) from 2019 to 2020 (Table 1). However, in both the prepandemic period (2018–2019) and the pandemic period (2020–2021), prevalence of metabolic syndrome decreased by 0.7% (20.4% to 19.7%) and (22.8% to 22.1%), respectively (both P < 0.05) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of Participants Who Had Metabolic Syndrome (Score ≥3) or Were in the Higher Risk Group for Each Cardiometabolic Risk Factor, 2018–2021

| 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Metabolic syndrome | 3,980 (20.4%) | 3,842 (19.7%)* | 4,456 (22.8%)*** | 4,315 (22.1%)* |

| Age, mean (SD) | 49.7 (10.2) | 50.8 (10.1) | 51.6 (10.1) | 52.8 (10.1) |

| Sex | ||||

| Women | 2,228 (18.3%) | 2,177 (17.9%) | 2,536 (20.9%)*** | 2,450 (20.9%)* |

| Men | 1,752 (23.7%) | 1,665 (22.5%)* | 1920 (26.0%)*** | 1865 (26.0%) |

| BMI, kg/m2 | ||||

| BMI <30 | 1,167 (9.4%) | 1,075 (8.7%)* | 1,349 (11.1%)*** | 1,313 (10.8%) |

| BMI 30.0–34.9 | 1,229 (32.7%) | 1,196 (31.2%) | 1,371 (35.0%)*** | 1,353 (33.8%) |

| BMI ≥35.0 | 1,576 (48.5%) | 1,562 (47.5%) | 1,722 (51.3%)*** | 1,641 (49.3%) |

| Race/ethnicity | ||||

| White | 1,586 (21.6%) | 1,567 (21.4%) | 1,777 (24.2%)*** | 1,756 (23.9%) |

| Black | 460 (17.1%) | 442 (16.5%) | 538 (20.0%)*** | 484 (18.0%)* |

| Hispanic | 486 (22.6%) | 436 (20.3%)* | 509 (23.7%)*** | 485 (22.5%) |

| Asian | 419 (14.9%) | 411 (14.6%) | 494 (17.6%)*** | 497 (17.7%) |

| Sleep hours per day | ||||

| <6 | 778 (25.1%) | 1,301 (21.8%) | 1,472 (26.1%)*** | 1,467 (24.7%) |

| 6–7 | 2,347 (19.6%) | 1,292 (19.1%)* | 1,452 (22.0%)*** | 1,396 (20.1%) |

| >7 | 709 (18.2%) | 1,110 (17.8%) | 1,385 (20.5%)*** | 1,274 (20.0%) |

| Exercise level per week | ||||

| 0 time | 1,555 (28.3%) | 1,461 (26.8%) | 1,645 (31.1%)*** | 1,622 (30.2%) |

| 1–2 times | 1,197 (20.8%) | 1,242 (20.7%) | 1,421 (23.9%)*** | 1,366 (23.1%)* |

| 3–4 times | 340 (15.6%) | 305 (15.1%) | 396 (18.9%)** | 332 (16.1%) |

| ≥5 times | 142 (11.6%) | 124 (10.5%) | 191 (14.3%)* | 153 (11.7%) |

| Cardiometabolic risk factor: higher risk group threshold | ||||

| Blood pressure: SBP ≥130 mm/Hg or DBP ≥85 mm/Hg | 6,245 (32.0%) | 6,449 (33.0%)** | 7,457 (38.2%)*** | 7,585 (38.8%) |

| Fasting glucose: ≥100 mg/dL | 4,597 (27.5%) | 4,462 (26.7%)* | 5,661 (33.9%)*** | 5,223 (31.2%)*** |

| HDL cholesterol: <50 mg/dL for women; <40 mg/dL for men | 5,399 (27.6%) | 4,895 (25.1%)*** | 4,893 (25.0%) | 4,535 (23.2%)*** |

| Waist circumference: >35 inches for women; >40 inches for men | 6,668 (34.1%) | 6,661 (34.1%) | 6,825 (34.9%)** | 6,974 (35.7%)** |

| Triglyceride: ≥150 mg/dL | 4,335 (22.2%) | 4,309 (22.1%) | 4,544 (23.3%)*** | 4,614 (23.6%) |

P value comparing between index year and previous year using McNemar's test, except for age: *** <0.001 ** <0.01 *<0.05.

N (%) are reported unless indicated otherwise.

Total # of participants is 19,543, except for BMI (n = 19,478), race (n = 14,989), sleep hours per day (n = 18,987), exercise level per week (n = 14,654), and fasting glucose (n = 16,732).

BMI, body mass index; DBP, diastolic blood pressure; HDL, high-density lipoprotein; SD, standard deviation; SBP, systolic blood pressure.

During the transition period, prevalence of metabolic syndrome increased by 3.5% in men and 3.0% in women (P < 0.001). Similarly, prevalence of metabolic syndrome increased across all race/ethnicity groups: 3.6% among Black participants, 3.4% among Hispanics, 3.0% among Asians, and 2.9% among Whites (all P < 0.001) (Table 1). During the same period, prevalence of metabolic syndrome increased by 2.4% in participants with BMI <30 kg/m2, 3.8% in those with BMI between 30.0 and 34.9 kg/m2, and 3.9% in those with BMI ≥30 kg/m2 (all P < 0.001) (Table 1).

Suboptimal lifestyle practices including insufficient sleep and lower levels of physical activity were associated with a higher prevalence of metabolic syndrome. Over the transition period, prevalence of metabolic syndrome increased by 4.3% among participants who reported either <6 hours sleep and those who reported participating in no physical activity (both P < 0.001) (Table 1).

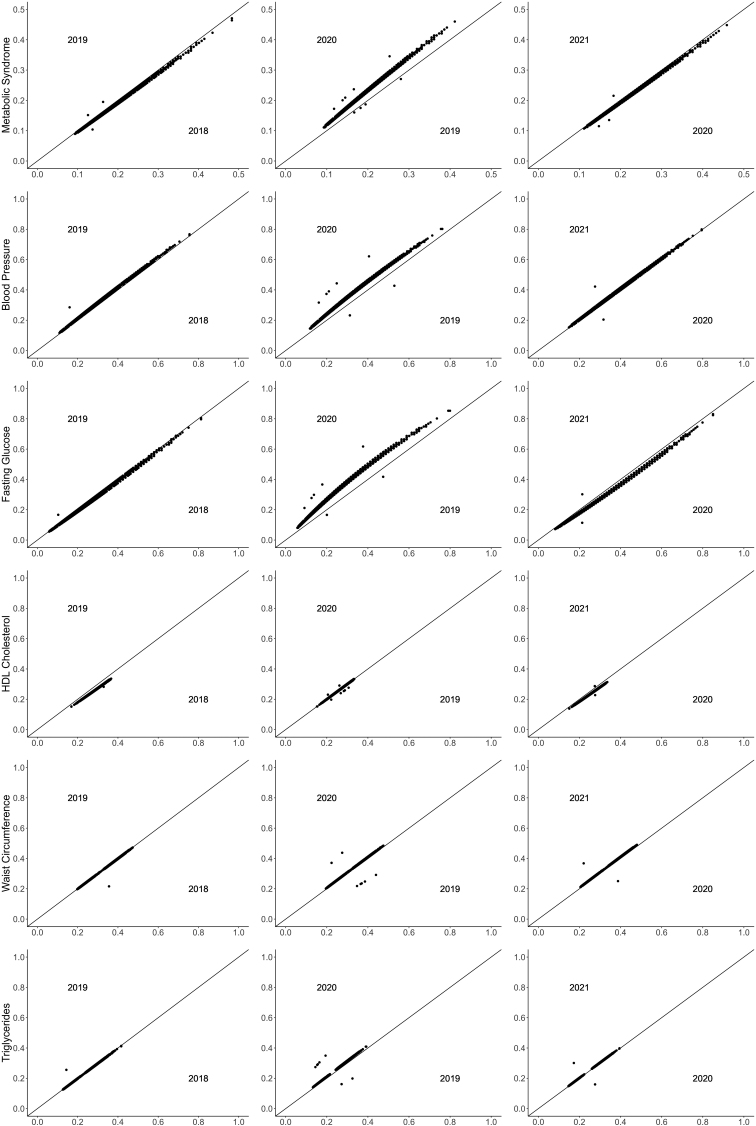

In Figure 1 based on model 1, during the transition period, probability of having metabolic syndrome increased from 2019 to 2020, after adjusting for age and sex (P < 0.001). Within the prepandemic period (2018–2019) and pandemic period (2020–2021), probability remained the same (Fig. 1). Examination of all 4 years of data together through a sensitivity analysis on model 1 (age and sex adjusted) yielded an equivalent effect on the probability of metabolic syndrome between 2019 and 2020 (P < 0.01).

FIG. 1.

Probability of metabolic syndrome and higher risk cardiometabolic risk factors by 2-year cluster (2018–2019, 2019–2020, 2020–2021). All P values <0.001 in mixed logistic regression models, comparing index year (2019/2020/2021) and previous year (2018/2019/2020), modeling the probability of metabolic syndrome or being in the higher risk group for each cardiometabolic risk factor, adjusted for age and sex.

Using the same multivariate model adjusted for age and sex, only two cardiometabolic risk factors, fasting glucose and blood pressure, showed a similar increase in year-to-year changes in the transition period from 2019 to 2020; the other three cardiometabolic risk factors including waist circumference, HDL cholesterol, and triglycerides did not show an evident change over the 4 study years including the transition period (2019–2020) (Fig. 1).

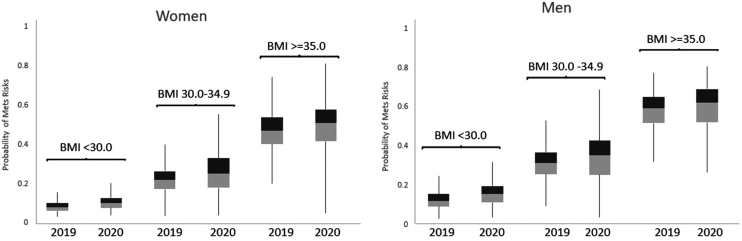

During the transition period, probability of having metabolic syndrome increased from 2019 to 2020, after adjusting for age, in both women and men and across all BMI categories (<30, 30–34.9, ≥35 kg/m2) (all P < 0.001) (Fig. 2). In this period, men had a higher probability of metabolic syndrome than women (P < 0.001); the median probability increased by 0.03–0.04 in men and by 0.02–0.03 in women, across three BMI categories. A higher BMI was associated with a higher probability of metabolic syndrome (P < 0.001); the median probability increased by 0.03 across all BMI categories from 2019 to 2020.

FIG. 2.

Probability of metabolic syndrome by sex and BMI 2019–2020. All P values <0.001 in mixed logistic regression modeling the probability of metabolic syndrome (2020 versus 2019), adjusted for age and sex. BMI, body mass index.

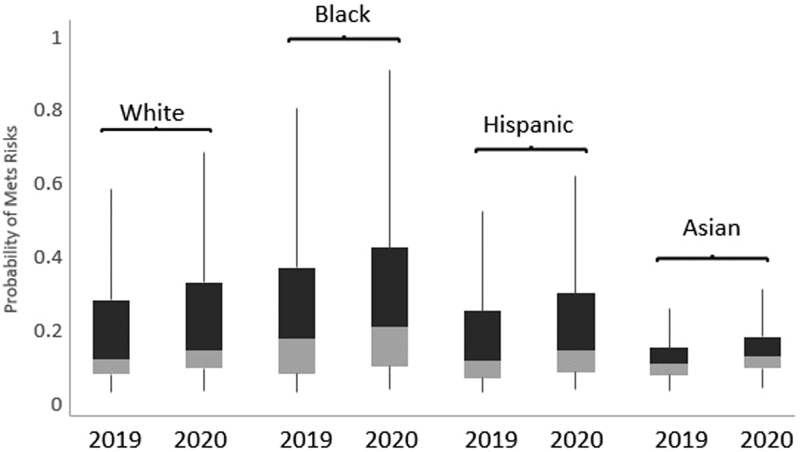

During the transition period, probability of having metabolic syndrome increased from 2019 to 2020, after adjusting for age, sex, and BMI, in all ethnic groups (all P < 0.001) (Fig. 3). In this period, Black participants had the highest probability, followed by White and Hispanic, and then by Asian participants (P < 0.001); the median probability increased by 0.02 for Black, Hispanic, and White groups, and by 0.01 for Asians, from 2019 to 2020.

FIG. 3.

Probability of metabolic syndrome by race 2019–2020. All P values <0.001 in mixed logistic regression modeling the probability of metabolic syndrome (2020 versus 2019), adjusted for age, sex, and BMI.

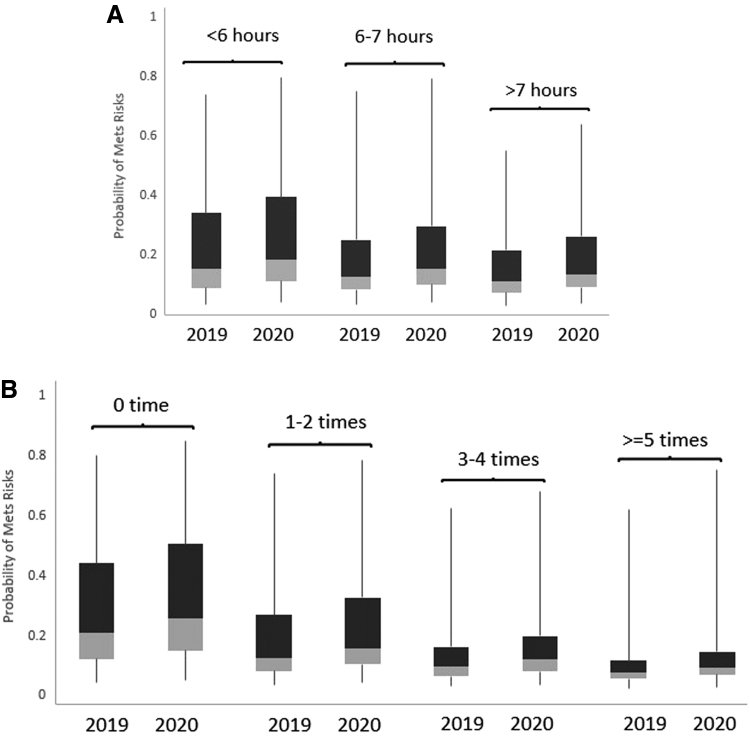

During the transition period, probability of having metabolic syndrome increased from 2019 to 2020, adjusted for age, sex, BMI, and ethnicity, in all sleep duration categories (<6 hours, 6–7 hours, and >7 hours) (all P < 0.001) (Fig. 4A). In this period, the less sleep per night, the higher risk of metabolic syndrome (P < 0.01); the median probability increased by 0.02–0.03 across all three sleep duration categories from 2019 to 2020.

FIG. 4.

Probability of metabolic syndrome 2019–2020 by (A) sleep duration per night and by (B) weekly exercise level. All P values <0.001 in mixed logistic regression modeling the probability of metabolic syndrome (2020 versus 2019), adjusted for age, sex, BMI, and race.

During the transition period, probability of having metabolic syndrome increased from 2019 to 2020, adjusted for age, sex, BMI, and ethnicity, across all exercise levels per week (0 time, 1–2 times, 3–4 times, and ≥5 times) (all P < 0.001) (Fig. 4B). A lower level of exercise was associated with a higher probability of metabolic syndrome (P < 0.001); the median probability increased by 0.05 for those participants who did not exercise at all, followed by 0.03 for one to two times, and then by 0.02 for three times or more, from 2019 to 2020.

Discussion

We evaluated the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on prevalence of metabolic syndrome in working-aged adults. The main finding of this analysis was that metabolic syndrome increased during the COVID-19 pandemic in this large U.S. population of working-aged adults. Although cardiometabolic risk has been increasing gradually in the U.S. population over the few decades,8,20 this study indicates measurable increases in risk during the COVID-19 lockdown period.

Previous research has similarly reported increases in cardiometabolic risk during the lockdown period in a smaller patient population21 and a Spanish population.22 To our knowledge, this is the first report to show increases in a large U.S. working-aged population after the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Prevalence of metabolic syndrome observed in the population of employees and their spouses/partners was similar to the rates observed in the U.S. adult population, where the prevalence of metabolic syndrome is 34.7% (with similar rates observed in men [35.1%] and women [34.3%]).8 National population health trends have shown increases in metabolic syndrome prevalence over the last decade, especially among those aged 20–39 years (from 16.2% to 21.3%), women (from 31.7% to 36.6%), Asian participants (from 19.9% to 26.2%), and Hispanic participants (from 32.9% to 40.4%).8 The high and growing rates of metabolic syndrome in U.S. working-aged populations present a major public health burden as metabolic syndrome is associated with increased risk of cardiovascular disease and all-cause mortality,11,12 higher medical costs,23,24 and lower job performance.25

Increases in metabolic syndrome were more commonly seen in individuals with a BMI in the overweight and obese range. The association of high BMI with metabolic syndrome has been clearly established, where metabolic syndrome impacts ∼60% of U.S. adults with obesity versus only 5% with normal body weight.26,27 Reasons for the greater increase in risk in those with a higher BMI are unknown but may be attributed to greater burden of the pandemic in individuals with an overweight or obese BMI. Specifically, the deleterious health behavior impacts of social isolation and stress may have disproportionately affected individuals with obesity, as previous reports showed that weight gain during the COVID-19 pandemic was more commonly reported in individuals with obesity.4 Factors contributing may include declines in physical activity,4 poor nutrition,4 and psychological stress.4,28 Not only has higher perceived stress been associated with a higher BMI and obesity,29 but increases in anxiety scores during the pandemic have been reported to be greater in people with obesity.4

As social isolation is associated with more intense stress during everyday events30 and higher cortisol reactivity in response to stress leads to higher calorie consumption and preferences for sweet foods,28 the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on lifestyle behaviors, body weight, and cardiometabolic risk factors may have presented an additional major public health burden.

Increases in metabolic syndrome were noted most commonly in men and women who reported sleeping <6 hours per night. The lockdown period was associated with a higher prevalence of sleep problems, impacting ∼18% of the general public.31,32 Sleep problems were especially common among health care workers (31%) and COVID-19 patients (57%).32 Moreover, the pandemic impacted sleep quality, where 43.8% reported worsened sleep quality.4 Previous research has linked insufficient sleep to cardiovascular and metabolic risk.33,34

Insufficient sleep has been associated with several health risks, including obesity, diabetes, hypertension, heart disease and stroke, and even premature death.33,34 Weight gain associated with insufficient sleep predisposes individuals to abdominal visceral obesity, and associated cardiovascular and metabolic risk.35 Thus, insufficient sleep appears to be a contributing factor to increases in metabolic syndrome likely through the mechanisms noted above.

Sleep deprivation has been reported to have a significant impact on metabolic and cardiovascular function,36 and this underappreciated risk factor deserves a full examination in large-scale population studies. Health interventions to mediate the cardiovascular and metabolic risk should evaluate and treat sleep disturbances, as appropriate.

Increases in metabolic syndrome were most commonly observed in men and women who reported participating in no physical activity. Physical activity modulates excess body weight,37 and is known to prevent and mitigate the impact of the metabolic syndrome.38 During the lockdown period, physical activity slightly decreased except in those with physical activity more than five times a week (increased by 1.7%, P < 0.001). Others similarly reported that sedentary leisure behaviors increased, while time spent in physical activity declined during the pandemic lockdown period.4 Insufficient physical activity appears to be a contributing factor to increases in the risk of metabolic syndrome. Thus, increasing physical activity is an important intervention to mitigate observed cardiometabolic risk increases, which is cost effective and underutilized.38 Moreover, the beneficial impact of physical activity on cardiovascular disease risk appears to even outweigh the negative impact of BMI in adults.37

Reasons for observed changes in health risks and behaviors may be attributable to social isolation and stress—both have unfavorable impacts on health and health behaviors.29,39–41 Social isolation adversely impacts health behaviors39–41 (including physical inactivity,40,41 poor diet,40,41 poor sleep quality,39 smoking,41 and use of psychotropic medications)40 and outcomes39–41 (including poor self-rated health,40 depression,39,40 unfavorable cardiovascular function,39 impaired immunity,39 impaired executive function,39 accelerated cognitive decline,39 altered hypothalamic pituitary-adrenocortical activity,39 a proinflammatory gene expression profile,39 multiple health problems,40 and earlier mortality).39

Future investigations are necessary to evaluate the relationship between stress factors and health risks. In addition, while the present investigation used fasting glucose as a measure of insulin resistance according to the existing criteria of metabolic syndrome,10 future evaluations should consider assessment of metabolic risk using hemoglobin A1C. Assessment of metabolic risk using hemoglobin A1C offers some advantages to fasting glucose, including nonfasting specimen collection and improved prediction of incident diabetes.42,43

Given the observation of increases in cardiometabolic risk in working-aged participants, screening and intervention (lifestyle and pharmaceutical) are increasingly necessary to reduce the cardiovascular and metabolic risk. Employees with metabolic syndrome have double the costs of those without any risk factors.23,24 Of the excess medical cost for individuals with metabolic syndrome, ∼20% is because of additional cardiovascular events and ∼80% because of the expense of higher prevalence of comorbidities, particularly cardiovascular disease and diabetes.24 Thus, prevention strategies including lifestyle interventions and drug therapy, if required, are needed to reduce the risk of cardiovascular disease19 and diabetes.11

Strategies to reduce the burden of metabolic syndrome may include lifestyle interventions such as Mediterranean diet44 and Diabetes Prevention Program intensive lifestyle interventions.45 Pharmaceutical interventions to manage the risk may include lipid lowering agents, antihypertensive agents, antidiabetic agents, heart failure drugs, and antiobesity therapies.46,47

Conclusion

Metabolic syndrome prevalence increased in this working-aged adult population during the transition period from prepandemic to the first COVID-19 pandemic year of 2019–2020. Despite rising prevalence of metabolic syndrome in U.S. adults in recent years, the pandemic appeared to contribute to risk increases during year 1 due to disrupted lifestyles, lower physical activity, and sleep disturbances. Those with existing metabolic risk due to overweight and obesity appeared to be particularly vulnerable to increases in the risk of metabolic syndrome. Management of the growing risk of metabolic syndrome presents an increasingly urgent priority for employers to support the health of their workforce.

Ethical Considerations

The analyses of this study were conducted according to the HIPAA Privacy Rule (Title 45 Code of Federal Regulations, Section 164.514e), which governs research conducted by covered health care entities and allows retrospective analysis using a limited data set without requiring approval of an institutional review board.

Authors' Contributions

M.S.F. contributed to conceptualization (lead), writing—original draft (lead); F.M. performed data curation, analysis, data visualization, and writing; Z.C. assisted with conceptualization (supporting), development and design of methodology, reviewing and editing; L.A.B. supported with conceptualization (supporting), analysis supervision, reviewing and editing.

Author Disclosure Statement

M.S.F., F.M., Z.C., and L.A.B. are employed by and have stock ownership in Quest Diagnostics.

Funding Information

No funding was received for this article.

References

- 1. Laffin LJ, Kaufman HW, Chen Z, et al. Rise in blood pressure observed among us adults during the covid-19 pandemic. Circulation 2022;145(3):235–237; doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.121.057075 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Fragala MS, Kaufman HW, Meigs JB, et al. Consequences of the covid-19 pandemic: Reduced hemoglobin a1c diabetes monitoring. Popul Health Manag 2021;24(1):8–9; doi: 10.1089/pop.2020.0134 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Kaufman HW, Chen Z, Niles J, et al. Changes in the number of us patients with newly identified cancer before and during the coronavirus disease 2019 (covid-19) pandemic. JAMA Netw Open 2020;3(8):e2017267; doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.17267 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Flanagan EW, Beyl RA, Fearnbach SN, et al. The impact of covid-19 stay-at-home orders on health behaviors in adults. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2021;29(2):438–445; doi: 10.1002/oby.23066 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Brooks SK, Webster RK, Smith LE, et al. The psychological impact of quarantine and how to reduce it: Rapid review of the evidence. Lancet 2020;395(10227):912–920; doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30460-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Leigh-Hunt N, Bagguley D, Bash K, et al. An overview of systematic reviews on the public health consequences of social isolation and loneliness. Public Health 2017;152:157–171; doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2017.07.035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Heffner KL, Waring ME, Roberts MB, et al. Social isolation, c-reactive protein, and coronary heart disease mortality among community-dwelling adults. Soc Sci Med 2011;72(9):1482–1488; doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.03.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Hirode G, Wong RJ. Trends in the prevalence of metabolic syndrome in the United States, 2011–2016. JAMA 2020;323(24):2526–2528; doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.4501 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Liang XP, Or CY, Cheun CL, et al. Prevalence of metabolic syndrome in the United States national health and nutrition examination survey (nhanes) 2011–2018. Eur Heart J 2021;42(1); doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehab724.2420 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Fahed G, Aoun L, Bou Zerdan M, et al. Metabolic syndrome: Updates on pathophysiology and management in 2021. Int J Mol Sci 2022;23(2):786; doi: 10.3390/ijms23020786 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Ford ES, Li C, Sattar N. Metabolic syndrome and incident diabetes: Current state of the evidence. Diabetes Care 2008;31(9):1898–1904; doi: 10.2337/dc08-0423 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Isomaa B, Almgren P, Tuomi T, et al. Cardiovascular morbidity and mortality associated with the metabolic syndrome. Diabetes Care 2001;24(4):683–689; doi: 10.2337/diacare.24.4.683 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Boudreau DM, Malone DC, Raebel MA, et al. Health care utilization and costs by metabolic syndrome risk factors. Metab Syndr Relat Disord 2009;7(4):305–314; doi: 10.1089/met.2008.0070 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Pyykkonen AJ, Raikkonen K, Tuomi T, et al. Stressful life events and the metabolic syndrome: The prevalence, prediction and prevention of diabetes (ppp)-botnia study. Diabetes Care 2010;33(2):378–384; doi: 10.2337/dc09-1027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Daniels NF, Burrin C, Chan T, et al. A systematic review of the impact of the first year of covid-19 on obesity risk factors: A pandemic fueling a pandemic? Curr Dev Nutr 2022;6(4):nzac011; doi: 10.1093/cdn/nzac011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Ahmed HO. The impact of social distancing and self-isolation in the last corona covid-19 outbreak on the body weight in sulaimani governorate- kurdistan/iraq, a prospective case series study. Ann Med Surg (Lond) 2020;59:110–117; doi: 10.1016/j.amsu.2020.09.024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Mulugeta W, Desalegn H, Solomon S. Impact of the covid-19 pandemic lockdown on weight status and factors associated with weight gain among adults in massachusetts. Clin Obes 2021;11(4):e12453; doi: 10.1111/cob.12453 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Lange SJ, Kompaniyets L, Freedman DS, et al. Longitudinal trends in body mass index before and during the covid-19 pandemic among persons aged 2–19 years - united states, 2018–2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2021;70(37):1278–1283; doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm7037a3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Grundy SM, Cleeman JI, Daniels SR, et al. Diagnosis and management of the metabolic syndrome: An american heart association/national heart, lung, and blood institute scientific statement. Circulation 2005;112(17):2735–2752; doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.169404 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Ford ES, Giles WH, Mokdad AH. Increasing prevalence of the metabolic syndrome among U.S. Adults. Diabetes Care 2004;27(10):2444–2449; doi: 10.2337/diacare.27.10.2444 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Auriemma RS, Pirchio R, Liccardi A, et al. Metabolic syndrome in the era of covid-19 outbreak: Impact of lockdown on cardiometabolic health. J Endocrinol Invest 2021;44(12):2845–2847; doi: 10.1007/s40618-021-01563-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Ramírez Manent JI, Altisench Jané B, Sanchís Cortés P, et al. Impact of covid-19 lockdown on anthropometric variables, blood pressure, and glucose and lipid profile in healthy adults: A before and after pandemic lockdown longitudinal study. Nutrients 2022;14(6):1237; doi: 10.3390/nu14061237 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Birnbaum HG, Mattson ME, Kashima S, et al. Prevalence rates and costs of metabolic syndrome and associated risk factors using employees' integrated laboratory data and health care claims. J Occup Environ Med 2011;53(1):27–33; doi: 10.1097/JOM.0b013e3181ff0594 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Fitch K, Pyenson B, Iwasaki K. Metabolic syndrome and employer sponsored medical benefits: An actuarial analysis. Value Health 2007;10(1):S21–S28; doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4733.2006.00151.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Schultz AB, Edington DW. Metabolic syndrome in a workplace: Prevalence, co-morbidities, and economic impact. Metab Syndr Relat Disord 2009;7(5):459–468; doi: 10.1089/met.2009.0008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Shi TH, Wang B, Natarajan S. The influence of metabolic syndrome in predicting mortality risk among us adults: Importance of metabolic syndrome even in adults with normal weight. Prev Chronic Dis 2020;17:E36; doi: 10.5888/pcd17.200020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Park YW, Zhu S, Palaniappan L, et al. The metabolic syndrome: Prevalence and associated risk factor findings in the US population from the third national health and nutrition examination survey, 1988–1994. Arch Intern Med 2003;163(4):427–436; doi: 10.1001/archinte.163.4.427 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Epel E, Lapidus R, McEwen B, et al. Stress may add bite to appetite in women: A laboratory study of stress-induced cortisol and eating behavior. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2001;26(1):37–49; doi: 10.1016/s0306-4530(00)00035-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Mouchacca J, Abbott GR, Ball K. Associations between psychological stress, eating, physical activity, sedentary behaviours and body weight among women: A longitudinal study. BMC Public Health 2013;13:828; doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-13-828 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Cacioppo JT, Hawkley LC. Social isolation and health, with an emphasis on underlying mechanisms. Perspect Biol Med 2003;46(3 Suppl):S39–S52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Alimoradi Z, Gozal D, Tsang HWH, et al. Gender-specific estimates of sleep problems during the covid-19 pandemic: Systematic review and meta-analysis. J Sleep Res 2022;31(1):e13432; doi: 10.1111/jsr.13432 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Alimoradi Z, Brostrom A, Tsang HWH, et al. Sleep problems during covid-19 pandemic and its' association to psychological distress: A systematic review and meta-analysis. EClinicalMedicine 2021;36:100916; doi: 10.1016/j.eclinm.2021.100916 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Cappuccio FP, Miller MA. Sleep and cardio-metabolic disease. Curr Cardiol Rep 2017;19(11):110; doi: 10.1007/s11886-017-0916-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Stranges S, Dorn JM, Cappuccio FP, et al. A population-based study of reduced sleep duration and hypertension: The strongest association may be in premenopausal women. J Hypertens 2010;28(5):896–902; doi: 10.1097/HJH.0b013e328335d076 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Covassin N, Singh P, McCrady-Spitzer SK, et al. Effects of experimental sleep restriction on energy intake, energy expenditure, and visceral obesity. J Am Coll Cardiol 2022;79(13):1254–1265; doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2022.01.038 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Sharma S, Kavuru M. Sleep and metabolism: An overview. Int J Endocrinol 2010;2010:270832; doi: 10.1155/2010/270832 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Koolhaas CM, Dhana K, Schoufour JD, et al. Impact of physical activity on the association of overweight and obesity with cardiovascular disease: The rotterdam study. Eur J Prev Cardiol 2017;24(9):934–941; doi: 10.1177/2047487317693952 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Myers J, Kokkinos P, Nyelin E. Physical activity, cardiorespiratory fitness, and the metabolic syndrome. Nutrients 2019;11(7):1652; doi: 10.3390/nu11071652 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Hawkley LC, Capitanio JP. Perceived social isolation, evolutionary fitness and health outcomes: A lifespan approach. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 2015;370(1669):20140114; doi: 10.1098/rstb.2014.0114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Hammig O. Health risks associated with social isolation in general and in young, middle and old age. PLoS One 2019;14(7):e0219663; doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0219663 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Kobayashi LC, Steptoe A. Social isolation, loneliness, and health behaviors at older ages: Longitudinal cohort study. Ann Behav Med 2018;52(7):582–593; doi: 10.1093/abm/kax033 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Bonora E, Tuomilehto J. The pros and cons of diagnosing diabetes with a1c. Diabetes Care 2011;34(Suppl 2):S184–S190; doi: 10.2337/dc11-s216 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Shiffman D, Tong CH, Rowland CM, et al. Elevated hemoglobin a(1c) is associated with incident diabetes within 4 years among normoglycemic, working-age individuals in an employee wellness program. Diabetes Care 2018;41(6):e99–e100; doi: 10.2337/dc17-2500 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Salas-Salvado J, Guasch-Ferre M, Lee CH, et al. Protective effects of the mediterranean diet on type 2 diabetes and metabolic syndrome. J Nutr 2015;146(4):920S–927S; doi: 10.3945/jn.115.218487 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Orchard TJ, Temprosa M, Goldberg R, et al. The effect of metformin and intensive lifestyle intervention on the metabolic syndrome: The diabetes prevention program randomized trial. Ann Intern Med 2005;142(8):611–619; doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-142-8-200504190-00009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Lillich FF, Imig JD, Proschak E. Multi-target approaches in metabolic syndrome. Front Pharmacol 2020;11:554961; doi: 10.3389/fphar.2020.554961 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Ott C, Schmieder RE. The role of statins in the treatment of the metabolic syndrome. Curr Hypertens Rep 2009;11(2):143–149; doi: 10.1007/s11906-009-0025-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]