Abstract

SQ109 is a tuberculosis drug candidate that has high potency against Mycobacterium tuberculosis and is thought to function at least in part by blocking cell wall biosynthesis by inhibiting the MmpL3 transporter. It also has activity against bacteria and protozoan parasites that lack MmpL3, where it can act as an uncoupler, targeting lipid membranes and Ca2+ homeostasis. Here, we synthesized 19 analogs of SQ109 and tested them against bacteria: M. smegmatis, M. tuberculosis, M. abscessus, Bacillus subtilis and Escherichia coli, as well as against the protozoan parasites, Trypanosoma brucei, T. cruzi, Leishmania donovani, L. mexicana and Plasmodium falciparum. Activity against the mycobacteria was generally less than with SQ109 and was reduced by increasing the size of the alkyl adduct, but two analogs were ~4–8 fold more active than was SQ109 against M. abscessus, including a highly drug resistant strain harboring a A309P mutation in MmpL3. There was also better activity than found with SQ109 with other bacteria and protozoa. Of particular interest, we found that the adamantyl C-2 ethyl, butyl, phenyl and benzyl analogs had 4–10x increased activity against P. falciparum asexual blood stages, together with low toxicity to a human HepG2 cell line, making them of interest as new anti-malarial drug leads. We also used surface plasmon resonance to investigate the binding of inhibitors to MmpL3, and differential scanning calorimetry to investigate binding to lipid membranes. There was no correlation between MmpL3 binding and M. tuberculosis or M. smegmatis cell activity, suggesting that MmpL3 is not a major target, in mycobacteria. However, some of the more active species decreased lipid phase transition temperatures, indicating increased accumulation in membranes, expected to lead to enhanced uncoupler activity.

Keywords: Tuberculosis, Malaria, Leishmaniasis, Antibiotic, Synthesis, Calorimetry

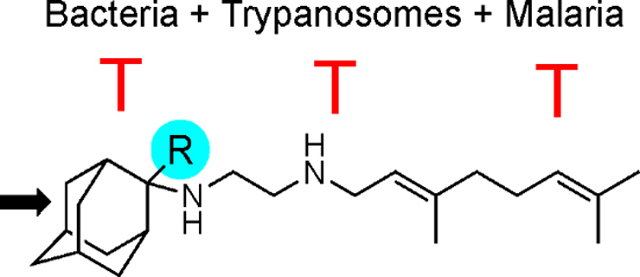

Graphical Abstract

INTRODUCTION

In 2020, an estimated 1.9 million people died from tuberculosis (TB), according to the World Health Organization. 1 Treatment with combinations of antibiotics (isoniazid, rifampicin, pyrazinamide, ethambutol) for six months can cure most people under optimal conditions, but globally, cure rates are less than optimal due to poor patient compliance to long-term chemotherapy, and the fact that some Mycobacterium tuberculosis (Mtb) strains have acquired mutations that render them resistant to many antibiotics. 2, 3 There is, therefore, the need for new, potent anti-tubercular drugs that have low rates of resistance. 2 One such drug candidate is the N-geranyl-N΄-(2-adamantyl)ethane-1,2-diamine SQ109, 4 a second generation ethylenediamine which has been in phase II clinical trials 5, 6 and shows high potency against drug resistant Mtb. 7 SQ109 binds 8 to the trehalose monomycolate transporter, Mycobacterial membrane protein Large 3 (MmpL3), and is known to inhibit cell wall biosynthesis. MmpL3 transporter activity is driven by the proton motive force (PMF) and previous research has suggested that SQ109 can function by directly blocking the transporter’s pore 9, 10 or indirectly, 7, 11 by acting as an uncoupler. Importantly, SQ109 also has a growth inhibitory activity against other bacteria 12, 13 (e.g. Helicobacter pylori 33,18), fungi (e.g. Candida albicans 11), malaria parasites (e.g. Plasmodium falciparum), 14 and the trypanosomatid parasite Trypanosoma cruzi, 15 all of which lack the MmpL3 transporter, or at least close homologs. There is, therefore, interest in the synthesis and testing of SQ109 analogs since these might have enhanced activity against not only mycobacteria, but also against other bacteria as well as against protozoa, yeasts and fungi.

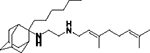

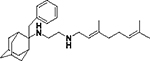

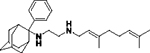

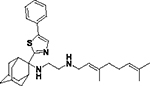

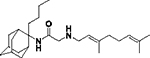

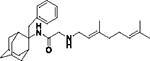

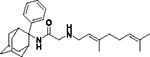

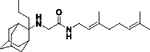

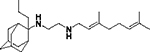

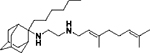

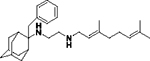

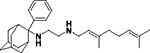

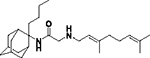

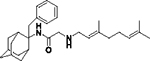

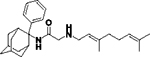

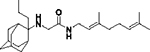

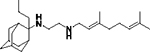

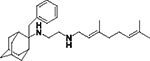

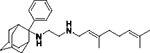

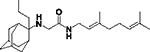

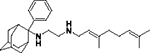

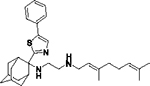

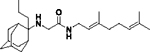

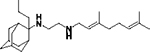

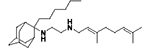

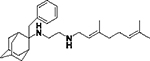

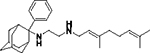

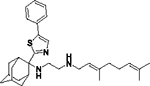

Here, we synthesized a series of analogs of SQ109 containing alkyl, aryl or heteroaryl groups at the C2-adamantyl position (Figure 1). Then, we tested SQ109 and the analogs against the following mycobacteria: M. smegmatis, M. tuberculosis HN878, M. tuberculosis Erdman (MtErdman), M. tuberculosis H37Rv (MtH37Rv), and M. abscessus. In addition, we tested these analogs against Bacillus subtilis, Escherichia coli, Plasmodium falciparum asexual blood stages, human hepatocyte carcinoma cells, T. brucei bloodstream forms, T. cruzi epimastigotes and amastigotes and their U20S host cells, L. donovani promastigote and L. mexicana promastigotes. We also explored the interaction of SQ109 and its analogs against MmpL3 using surface plasmon resonance (SPR), in addition to using differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) to explore the interactions of a subset of compounds with lipid bilayer membranes.

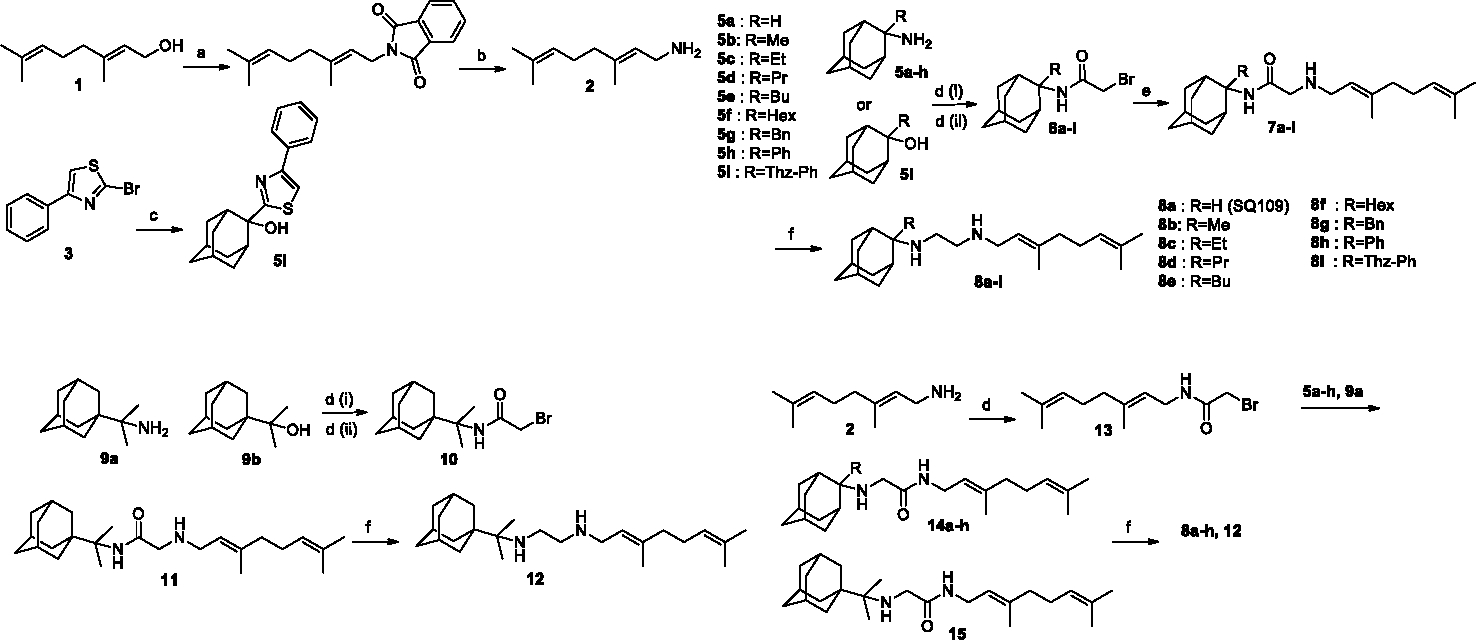

Figure 1.

Reagents and conditions: (a) Phthalimide, PPh3, DEAD, and THF, rt, 24h (81%); (b) N2H4·H2O, EtOH, reflux, 6h; (81%); (c) (i) n-BuLi, THF, −75 °C, 30 min; (ii) 2-adamantanone, THF, −75 °C, 1h; (iii) H2O, 0 °C, (56%). (di) ClCOCH2Br, K2CO3 (aq), CH2Cl2, rt, 24h (83–93%); (dii) BrCH2CN, AcOH, H2SO4, rt, 1h (61%-quant.); (e) geranylamine (2), Et3N, dry THF, rt, 48h (86–90%); (f) (i) Me3SiCl, LiAlH4, dry CH2Cl2, 0–5°C, Ar, 2.5 h; (ii) NaOH 10%, 0°C (20–40%).

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Synthesis of SQ109 analogs.

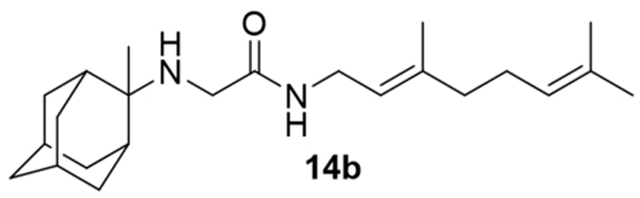

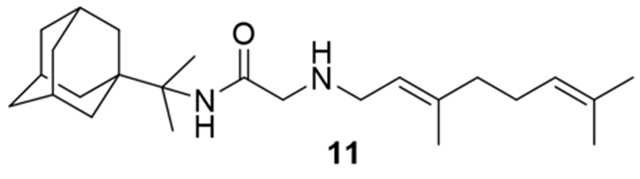

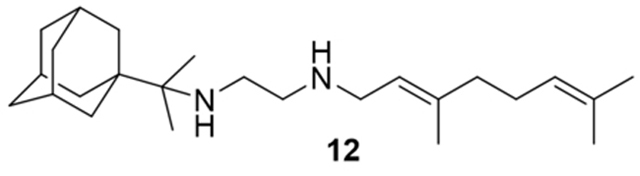

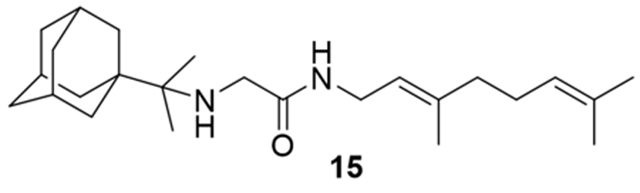

Based on the observation that the X-ray structure of SQ109 bound to MmpL3 9 has the adamantyl group located close to four aromatic rings, we elected to synthesize a series of analogs with substituents at the adamantyl C-2 position which we reasoned might have enhanced hydrophobic interactions with the protein, as well as with membranes. For the synthesis of compounds 8b-i, 12 we used as starting material geranylamine (2), 16, 17 which we prepared from geraniol (1) using the Mitsunobu reaction (phthalimide, PPh3, DEAD), and amines 5a-h, 9a, which we synthesized as described previously 18–20 (Figure 1). We carried out the preparation of the alcohol 5i from the reaction of the 2-thiazolyl lithium reagents (generated from 3 21, 22 with n-BuLi) and 2-adamantanone. We prepared the bromoacetamide (Figure 1) with Thz-Ph group 6i as well as 10, through a modified 20 Ritter reaction (BrCH2CN, AcOH, H2SO4) from the corresponding tertiary alcohols 5i, 9b. 18–20 We prepared the bromoacetamide derivatives 6a-h and aminoacetamides 7b-c, 11 or 14b-h, 15 as previously described for SQ109 (8a). 22 In aminoamides 14a-h, 15 or 7a-i, 11, compared to SQ109 (8a), it seemed possible that the bulkier substituents at the adamantyl C-2 carbon might hinder reduction of the amide carbonyl, leading to a mixture of the desired ethylenediamines, accompanied by amine decomposition by-products, formed when LiAlH4 in THF is used. 23–25 We thus synthesized the amide precursors 7a-i, 11 or 14a-h, 15 using LiAlH4 in combination with freshly distilled trimethylchlorosilane (Me3SiCl), in THF, with stirring for 2.5h at 0–10 °C under an argon atmosphere, as described for SQ109 (8a). 22 We obtained the diamines 8a-i, 12 which were purified by using column chromatography, and were then converted to crystalline difumarate salts for cell growth inhibition testing. Aminoacetamides were tested as crystalline monofumarate salts.

Anti-bacterial and anti-protozoal activity of SQ109 analogs.

We next investigated the activity of SQ109 (8a), its ethylenediamine analogs 8b-i, 12 and several aminoamide analogs: 7a, 7c, 7e, 7g, 7h, 14a, 14b, 14d, 11, 15 (Figure 1) against several bacteria, as well as protozoan parasites. We measured IC50 or MIC values (Table 1) against the following bacteria: M. smegmatis, M. tuberculosis HN878 (a virulent clinical strain), MtErdman, MtH37Rv, M. abscessus, B. subtilis and E. coli. The protozoa were T. brucei bloodstream forms, T. cruzi Dm28c epimastigotes and intracellular amastigotes (together with results for the U2OS host cells), L. donovani promastigotes, L. mexicana promastigotes and P. falciparum asexual bloodstream forms (ABS). For the protozoa, we determined parasite IC50 and EC50 values, as well as CC50 values for host cells. Results are shown in Tables 2 and 3.

Table 1.

Anti-bacterial activity of SQ109 analogs.

| Comp. No | Chemical structure | Ms IC50 (μM) | Mtb HN878 IC50 (μM) | Mtb HN878 MIC (μM) | Mtb Erdman MIC (μM) | Mtb H37Rv MIC (μM) | Ma(S) MIC (μM) | Ma(R) MIC (μM) | Bs IC50 (μM) | Ec IC50 (μM) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 8a |

|

2.4 ± 0.3 | 0.27 ± 0.02 | 0.4 | 1.8 | 1.8 | 44 | 22 | 16 | 15 |

| 8b |

|

4.4 ± 0.5 | 0.86 ± 0.06 | 0.8 | 3.5 | 3.5 | 43 | 22 | ND | 25 |

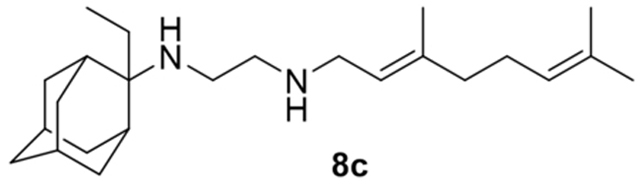

| 8c |

|

4.0 | 1.9 ± 0.06 | 1.6 | 6.8 | 6.8 | 22 | 10.7 | 4.3 | 18 |

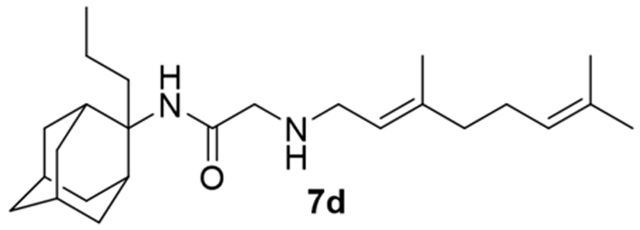

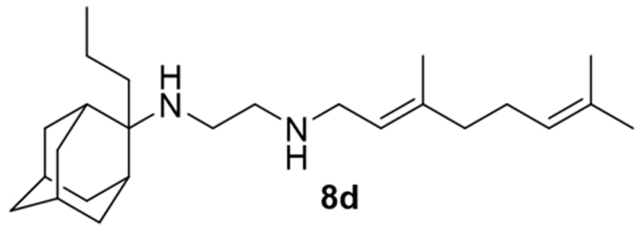

| 8d |

|

4.3 ± 0.8 | 2.6 ± 1 | 3 | 13 | 13 | 10 | 10 | ND | 7.6 |

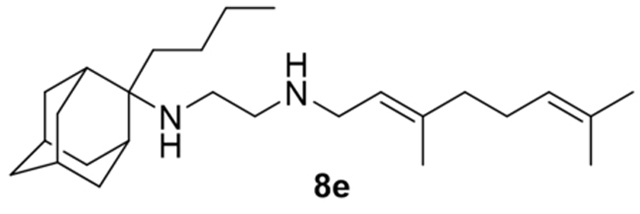

| 8e |

|

2.5 | 2.5 ± 0.2 | 3 | 9.7 | 12.9 | 6.2 | 6.2 | 0.54 | 7.8 |

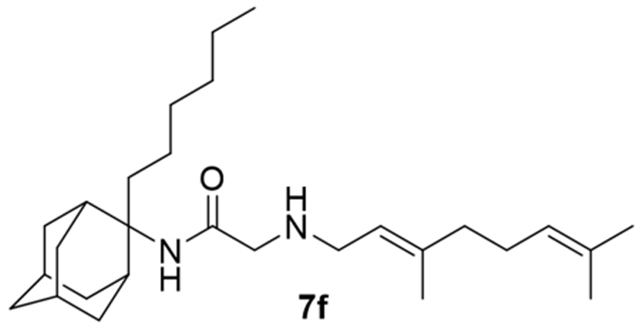

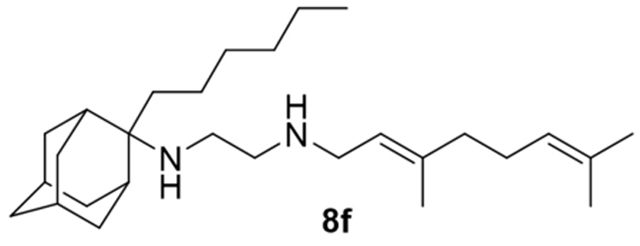

| 8f |

|

4.7 | 3.4 ± 0.6 | 3 | 12 | 12 | 12 | 12 | 1.0 | 9.2 |

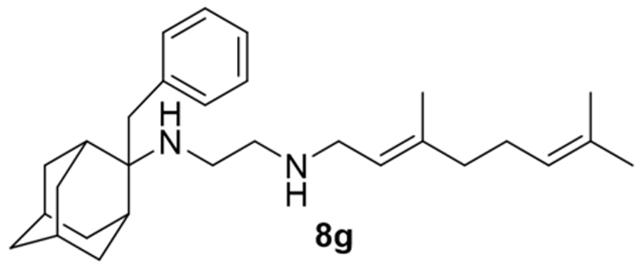

| 8g |

|

6.0 | 2.0 ± 0.5 | 1.6 | 6.1 | 6.1 | 5.8 | 5.8 | 0.59 | 1.3 × 102 |

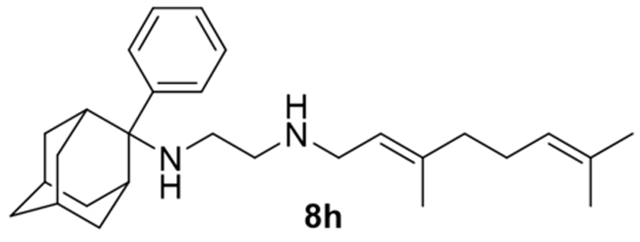

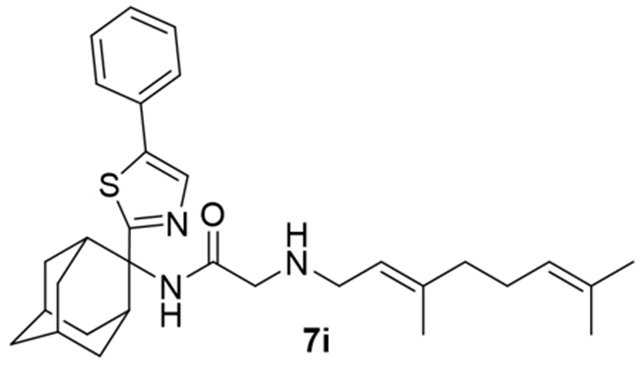

| 8h |

|

5.8 | 2.3 ± 0.2 | 1.6 | 13 | 13 | 12 | 6 | ND | No inhibition |

| 12 |

|

15 ± 2 | 3.4 ± 0.6 | 3 | 13 | 13 | 12.9 | 12.9 | ND | 8.9 |

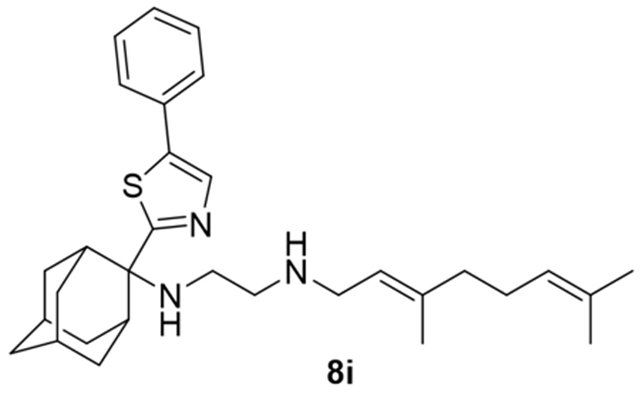

| 8i |

|

21 | ND | ND | ND | ND | 21.5 | 21.5 | ND | ND |

| 7a |

|

45 ± 6 | >25 | 25 | 340 | 340 | ND | ND | ND | 2.3 × 102 |

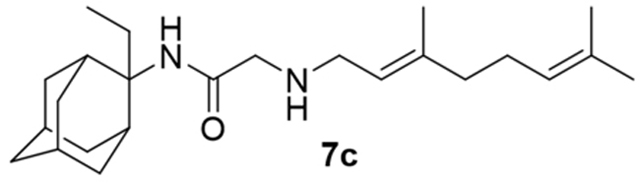

| 7c |

|

7.7 | 6.6 ± 0.2 | 6.25 | 16 | 16 | ND | ND | 1.9 | No inhibition |

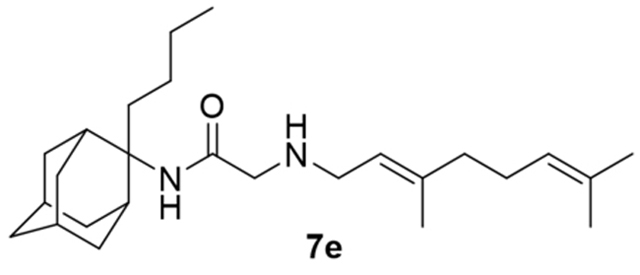

| 7e |

|

17 | 13 ± 0.3 | 12.5 | 15 | 15 | ND | ND | 2.8 | No inhibition |

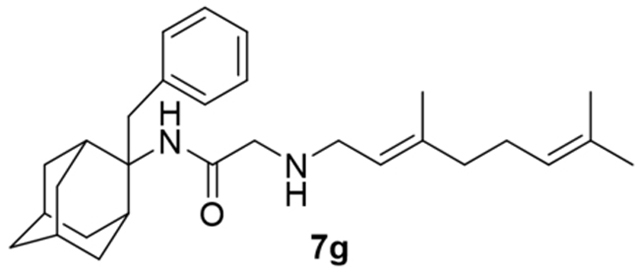

| 7g |

|

17 | 11 ± 1 | 12.5 | 29 | 29 | ND | ND | 2.3 | No inhibition |

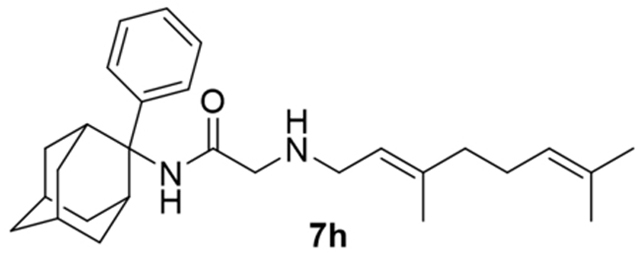

| 7h |

|

26 | ND | ND | 38 | 38 | ND | ND | 4.5 | No inhibition |

| 11 |

|

44 ± 4 | 13 ± 2 | 12.5 | 19 | 19 | ND | ND | ND | No inhibition |

| 14a |

|

5 ± 0.8 | 3.7 ± 0.6 | 3 | 16 | 21 | ND | ND | ND | 695 |

| 14b |

|

9 | 4.9 ± 0.1 | 6.25 | 20 | 30 | ND | ND | ND | No inhibition |

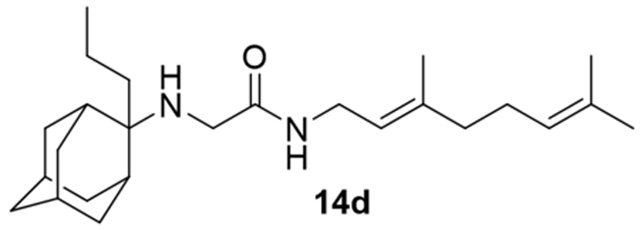

| 14d |

|

49 ± 5 | >25 | 25 | 32 | 32 | ND | ND | ND | No inhibition |

| 15 |

|

31 ± 3 | 17 ± 6 | 12.5 | 38 | 38 | ND | ND | ND | No inhibition |

Abbreviations used: Ms, M. smegmatis; Mtb, M. tuberculosis; Ma, M. abscessus; S, smooth variant; R, rough variant; Bs, Bacillus subtilis; Ec, E. coli. ND=not determined.

Table 2.

Activity of SQ109 analogs against Trypanosomatid parasites

| Comp. No | Chemical structure | T. brucei IC50 μM | T. cruzi | L. donovani IC50 μM | L. mexicana IC50 (μM) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IC50 (EPI) μM | IC50 (PAR) μM | CC50 (U20S) μM | |||||

| 8a |

|

0.91 ± 0.03 | 6.8 ± 2 | 0.74 ± 0.04 | 4.1 ± 0.2 | 2.0 ± 0.1 | 0.73 ± 0.2 |

| 8b |

|

2.1 ± 0.02 | 3.5 ± 1 | 0.77 ± 0.2 | 2.8 ± 0.7 | 2.0 ±1 | 0.43 ± 0.08 |

| 8c |

|

1.4 ± 0.2 | 8.0 ± 2 | 1.3 ± 0.06 | 2.5 ± 0.3 | 2.1 ± 0.4 | ND |

| 8d |

|

0.88 ± 0.2 | 2.1 ± 0.9 | 0.60 ± 0.5 | 1.6 ± 0.1 | 2.0 ±0.2 | 1.9 ± 0.2 |

| 8e |

|

0.37 ± 0.02 | 2.5 ± 1 | 0.84 ± 0.5 | 1.7 ± 1 | 4.0 ± 0.4 | ND |

| 8f |

|

0.98 ± 0.09 | 8.2 ± 0.4 | 1.3 ± 0.07 | 4.1 ± 1 | 8.8 ± 0.4 | ND |

| 8g |

|

0.85 ± 0.09 | 6.6 ± 1 | 0.92 ± 0.06 | 2.0 ± 0.4 | 6.1 ± 0.06 | ND |

| 8h |

|

1.3 ± 0.3 | 7.3 ± 2 | 0.60 ± 0.04 | 3.5 ± 1 | 1.4 ± 1 | ND |

| 12 |

|

1.4 ± 0.03 | 2.4 ± 0.7 | 0.56 ± 0.9 | 1.4 ± 0.2 | 2.3 ± 0.1 | 4.7 ± 0.2 |

| 7a |

|

12 ± 1 | >100 | 4.2 ± 0.4 | 14 ± 0.7 | 10 ± 0.5 | 2.2 ± 0.8 |

| 7c |

|

3.9 ± 0.3 | 14 ± 0.04 | 3.2 ± 0.2 | 7.5 ± 0.6 | 44 ± 11 | ND |

| 7e |

|

3.0 ± 0.2 | 48 ± 0.07 | 8.8 ± 1.3 | 15 ± 0.5 | 25 ± 14 | ND |

| 7g |

|

5.6 ± 1 | 17 ± 4 | 2.9 ± 0.3 | 7.0 ± 0.2 | 27 ± 0.8 | ND |

| 7h |

|

4.1 ± 0.6 | 18 ± 2 | 3.4 ± 0.2 | 7.0 ± 0.4 | 26 ± 28 | ND |

| 11 |

|

6.2 ± 0.2 | 16 ± 4 | 4.4 ± 0.3 | 6.9 ± 0.1 | 5.0 ± 0.6 | 5.2 ± 0.2 |

| 14a |

|

9.9 ± 0.7 | 28 ± 4 | 2.7 ± 0.2 | 9.5 ± 0.9 | 12 ± 0.9 | 2.0 ± 0.2 |

| 14b |

|

6.6 ± 0.03 | 18 ± 4 | 2.3 ± 0.2 | 7.2 ± 0.9 | 11 ± 0.9 | 2.4 ± 0.7 |

| 14d |

|

2.3 ± 0.1 | 14 ± 5 | 2.8 ± 0.3 | 9.1 ± 0.4 | 8.4 ± 2 | 0.73 ± 0.2 |

| 15 |

|

5.9 ± 0.1 | 15 ± 3 | 2.6 ± 0.1 | 7.1 ± 0.5 | 12 ± 8 | 5.0 ± 0.1 |

Table 3.

Activity of SQ109 analogs against Plasmodium falciparum asexual blood stages

| Comp. No | Chemical structure | PfABS IC50 (μM ± S.E.) | HepG2 % viability @ 20 μM |

|---|---|---|---|

| 8a |

|

1.58 ± 0.2 | 97 |

| 8b |

|

0.66 ± 0.18 | 100 |

| 8c |

|

0.16 ± 0.07 | 43 (85% @ 2 μM) |

| 8d |

|

0.53 ± 0.22 | 100 |

| 8e |

|

0.27 ± 0.04 | 50 (83% @ 2 μM) |

| 8g |

|

.032 ± 0.03 | 100 |

| 8h |

|

0.42 ± 0.09 | 100 |

| 7a |

|

6.49 ± 0.33 | 100 |

| 11 |

|

7.63 ± 1.13 | 100 |

| 12 |

|

0.77 ± 0.1 | 100 |

| 14a |

|

>10 | 99 |

| 14b |

|

6.47 ± 0.65 | 94 |

| 14d |

|

5.27 ± 0.41 | 100 |

| 15 |

|

5.44 ± 0.32 | 76 (91% @ 2 μM) |

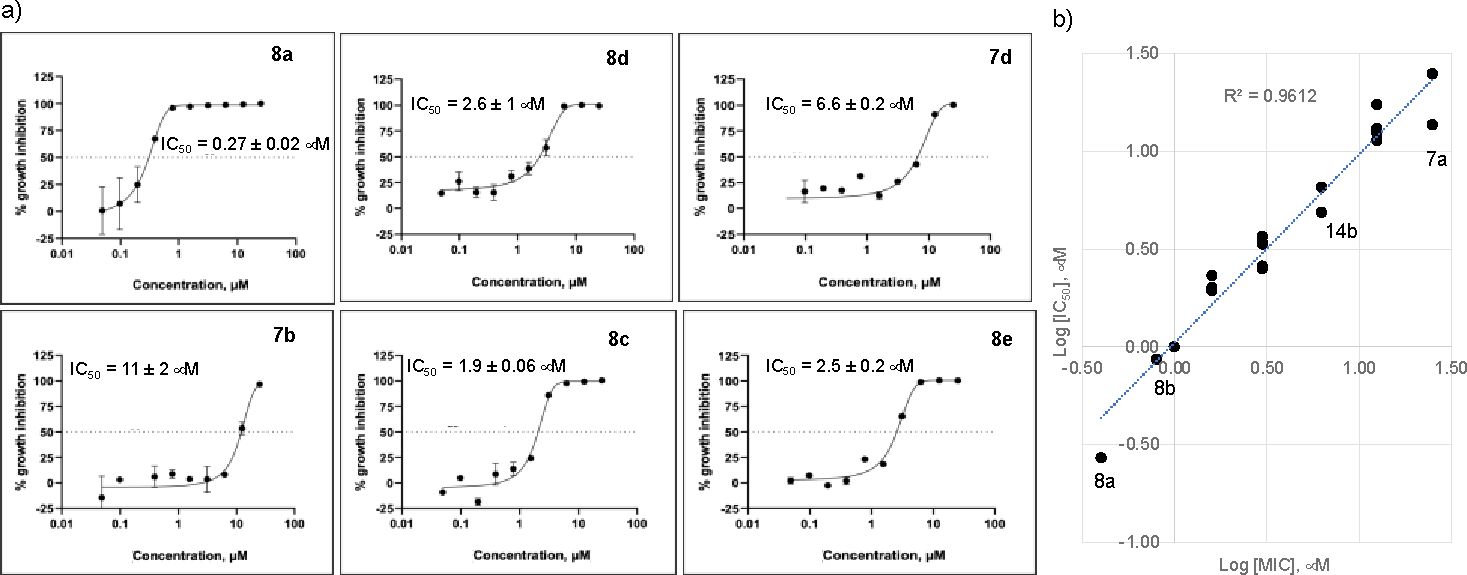

We first screened the 19 SQ109 analogs (together with SQ109) against M. smegmatis (Table 1). The IC50 value for SQ109 (8a) against M. smegmatis was 2.4 μM, in good accord with previous work. 26 Addition of an n-butyl group at C-2 (8e) yielded essentially the same result (IC50 = 2.5 μM, Table 1) while shorter as well as more bulky substituents had less activity. For example, methyl (8b), ethyl (8c), n-propyl (8d), n-hexyl (8f), phenyl (8h) and benzyl (8g) group analogs had IC50 values in the ~4–6 μM range. The larger substituted thiazole (8i) was even less active, with IC50 = 20 μM (Table 1). Likewise, the C-1 substituted analog 12, containing a dimethylmethylene group, was less active, with an IC50 value of 15 μM. Thus, the most active compounds have a relatively small substituent at C-2 and have IC50 values in the ~2–4 μM range. We then investigated the activity of SQ109 and the SQ109 analogs against MtHN878, a hypervirulent M. tuberculosis strain. Representative dose-response curves are shown in Figure 2a. MIC values are also shown in Table 1 and a correlation (R2=0.96) between the log IC50 values from the dose response curves and the log MIC values from visual inspection is shown in Figure 2b. MIC value determination using visual inspection rather than a plate reader is particularly important with M. abscessus, described below, since in the rough (R) form cells are prone to clumping. As can be seen in Table 1, the presence of a methyl group at C-2 (8b) yielded an IC50 = 0.86 μM (Table 1) which is ~3-fold higher than the IC50 = 0.27 μM of SQ109. Τhe larger alkyl adducts, e.g. ethyl (8c), n-propyl (8d), n-butyl (8e), n-hexyl (8f), benzyl (8g) and phenyl (8h) analogs showed comparable IC50 values, in the ~2–3 μM range. In addition, we tested compounds against the M. tuberculosis Erdman and H37Rv strains, finding generally similar patterns of activity with the methyl adduct yielding an IC50 = 2 μM (Table 1) and other analogs with alkyl groups having IC50 values in the 4–8 μM range (Table 1). This activity was at least 2-fold lower than found with SQ109 (8a) (IC50 = 1 μM), and the aminoamides (7a, 7c, 7e, 7g 7h, 14a, 14b, 14d, 11, 15) were generally less active than the more basic, ethylenediamine analogs.

Figure 2.

Dose-response curves for SQ109 and the SQ109 analogs against MtHN878 and correlation between Iog IC50 and log MIC values. a) Representative dose response curves. b) Correlation between Iog IC50 and log MIC values (R2 = 0.9612).

In addition to investigating M. tuberculosis, we also investigated activity against M. abscessus, which is increasingly recognized 27 as an emerging opportunistic pathogen causing severe lung disease, particularly in cystic fibrosis patients. Since it is intrinsically resistant to most conventional antibiotics, there is an unmet need for effective treatments.27 We determined the in vitro activity of SQ109 and a series of analogs against both smooth (S) and rough (R) variants of M. abscessus, which differ in their susceptibility profile to several antibiotics. As has been shown previously, 6 the MIC of SQ109 (8a) was much higher against M. abscessus (here, 22–44 μM) than against M. tuberculosis (~0.3–1 μM). However, the n-butyl analog 8e as well as the benzyl analog 8g had significantly improved activity against both the S and R variants (MICs of 5.8–6.2 μM), warranting future work on benzyl derivatives. The MIC values of all compounds against the R and S strains were either identical to or within a factor of 2x of each other. We also investigated an M. abscessus strain harboring a A309P mutation located in the transmembrane domain in MmpL3 (strain PIPD1R1), which displays very high resistance to the piperidinol-containing molecule PIPD1, 28 the indole-2 carboxamide Cpd12, 25 and the benzimidazole EJMCh-6. 25 Surprisingly, this mutant was not resistant to SQ109 or its analogs, having essentially the same MIC values as the wild type strains. This is a potentially important observation since resistance to other MmpL3 inhibitors can be very large (e.g. 32–64x for PIPD128). This lack of resistance may indicate that binding to MmpL3 is not the primary target of SQ109 (8a) and its analogs, in M. abscessus.

We then questioned whether any of the compounds investigated had activity against other bacteria, ones which lack MmpL3. In the gram-positive bacterium B. subtilis, SQ109 (8a) had an IC50 value of 16 μM (Table 1) and of interest, several of the SQ109 analogs had much better activity. For example, n-butyl (8e), n-hexyl (8f) and phenyl (8h) analogs had IC50 values in the 0.5–1.0 μM range (Table 1). We also observed that some tested aminoamides had activity, in the 2–5 μM range. In the gram-negative bacterium E. coli, the IC50 value for SQ109 (8a) was 15 μM and the n-alkyl (propyl, butyl, hexyl) analogs had IC50 values in the ~ 8–10 μM range—slightly better than found with SQ109 (8a). Since neither B. subtilis nor E. coli contain the MmpL3 protein, other targets must be involved, so the promising activity of some compounds is of interest, for future work. There was either no inhibition or very low inhibition (IC50 values > 70 μM) with the aminoamides tested (Table 1), suggesting that the ethylenediamine group might play a role in activity, as an uncoupler—as previously suggested for Mtb and protozoa.

Next, we investigated the activities of the SQ109 analogs against the following protozoa: T. brucei, T. cruzi, and two Leishmania species. In each case, the activity of SQ109 (8a) against these protozoa has been reported previously and has been proposed to arise from protonophore uncoupling, as well as effects on Ca2+ homeostasis. 15, 29, 30 Results for SQ109 (8a) and the analogs are shown in Table 2 and representative dose-response curves are shown in Figure S1. With T. brucei bloodstream forms, SQ109 (8a) had an IC50 value of 0.91 μM and slightly better activity was found with the adamantyl C-2 n-propyl (8d), n-butyl (8e), n-hexyl (8f) and benzyl (8g) analogs (IC50 values of 0.88 μM, 0.37 μM, 0.98 μM and 0.85 μM, respectively), but is slightly less with phenyl (8h) and C-1 dimethylmethylene (12) analogs (IC50 values of 1.3 μM, 1.4 μM, respectively). Of interest, the aminoamides also had activity although IC50 values were ~5–10-fold larger (in the range ~ 2–12 μM) compared to the ethylenediamines (8b-g, 12). With T. cruzi, we investigated both the epimastigotes as well as the (clinically relevant) amastigote forms, and activity against the host cell (U2OS). With epimastigotes, the IC50 of SQ109 was 6.8 μM which is ~3–4x larger than that found with the C2 ethylene diamine analogs, n-propyl (8d), n-butyl (8e) and the C-1 dimethylmethylene analog (12). With aminoamide analogs, activity was again lower than with the ethylene diamine analogs. With the intracellular amastigote form, SQ109 (8a) had an IC50 value of 0.74 μM and all of the ethylenediamine analogs had good activity, with the phenyl (8h) analog being comparable to (though not clearly better than) SQ109. The aminoamides were all less active, with IC50 values in the range ~ 2–9 μM. The same trends in activity were seen with the inhibition of host cell growth, with the ethylenediamines being more potent host cell growth inhibitors than were the amides. With L. donovani, we tested SQ109 and 18 analogs (Table 2). The IC50 value for SQ109 was 2 μM and the adamantyl C-2 methyl (8b), ethyl (8c), n-propyl (8d), n-butyl (8e), phenyl (8h), dimethylmethylene (12) analogs had higher or similar activity (in the 1–4 μM range), while the n-hexyl (8f) analog was less active (IC50 = 8.8 μM) as was the benzyl (8g) analog (IC50 = 6.1 μM). As with T. brucei and T. cruzi, the aminoamides were in general less (or much less) active with IC50 values in the range ~ 5–44 μM. With L. mexicana the IC50 value for SQ109 (8a) was 0.50 μM and the adamantyl C-2 methyl (8b) had an IC50 = 0.43 μM while the n-propyl (8d) was ~4-fold less active (IC50 = 1.94 μM). Several aminoamides had similar activity with 8d and amide 14d having IC50 = 0.73 μM (Table 2).

In addition to investigating the trypanosomatid parasites, we also investigated the asexual bloodstream form of the apicomplexan parasite P. falciparum (PfABS). As previously reported, 26 SQ109 (8a) has activity against the PfABS parasite and only modest toxicity against HepG2 (human hepatocellular carcinoma) cells. We thus evaluated SQ109 and 13 of its analogs finding more potent (~100–900 nM) PfABS activity with the adamantyl C-2 methyl (8b), ethyl (8c), n-propyl (8d), n-butyl (8e), phenyl (8h) and benzyl (8g) analogs, as well as with the C-1 dimethylmethylene analog (12), compared to SQ109 (IC50 = 1.6 μM, Table 3). The ethyl (8c) analog had ~10-fold better activity than that obtained with SQ109 (160 nM versus 1.6 μM), while the phenyl (8h) and benzyl (8g) analogs had 4x and 5x increased potency, respectively. Using HepG2 cell line viability as a test of overt toxicity, we found that there was 43% cell viability at 20 μM with the ethyl analog, but 100% viability with both phenyl and benzyl analogs, making them of potential interest as an antimalarial hit with low toxicity against mammalian cells.

When taken together, the results with M. tuberculosis cell growth inhibition indicate that it is difficult to improve upon the activity of SQ109 (8a) by adding substituents at the C-2 position. For example, the methyl (8b) and benzyl (8g) substituents at the adamantyl C-2 group had ~2–4-fold less activity against MtbHN878, MtErdman and MtH37Rv (Table 1). However, there was promising activity against both the S and R variants of M. abscessus. What is also of course of interest is the observation that some of the analogs do have better activity that does SQ109 against bacteria that lack the putative MmpL3 target, e.g. B. subtilis and E. coli, as also found with the malaria parasite, P. falciparum. A question then arises as to whether there is any correlation between MmpL3 binding and cell activity, in the mycobacteria.

MmpL3–inhibitor binding interactions.

We next used SPR to investigate the binding of SQ109 and several analogs to an expressed M. tuberculosis MmpL3 (MtMmpL3).10 We focused on measurement of the KD values for SQ109 (8a) and the 9 ethylenediamine analogs 8b-i, 12, together with four aminoamides 7a, 14a, 14b, and 14d. The experimental SPR results are shown in Figure S2. Data were fit using the two-state model, as described previously, 10 together with the 1:1 binding model.

The rate constants and the equilibrium dissociation constants KD for both models are shown in Tables 4 and 5. The two-state binding model that postulates a conformational change in the protein upon binding of an inhibitor gave improved statistical fits as seen from lower residuals values. However, as can be seen in Table 4 there are essentially no differences between the KD values obtained using either model.

Table 4.

SPR results for M. tuberculosis MmpL3-ligand binding using a 1:1 binding modela

| Comp. No | Chemical structure | KD, μM 1:1 model |

Residuals χ2 (RU)2 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 8a |

|

351.9 | 0.882 | 2510 | 58.7 |

| 8b |

|

3658 | 0.6882 | 188 | 16 |

| 8c |

|

4710 | 0.8409 | 180 | 37.9 |

| 12 |

|

6276 | 0.6646 | 106 | 62.2 |

| 8d |

|

5926 | 0.5403 | 91 | 48.9 |

| 8e |

|

3998 | 0.3888 | 97 | 22.6 |

| 8f |

|

4441 | 0.2964 | 67 | 126 |

| 8g |

|

5789 | 0.3999 | 69 | 85.1 |

| 8h |

|

4060 | 0.465 | 115 | 110 |

| 8i |

|

5627 | 0.4902 | 87 | 108 |

| 7a |

|

9.44E+02 | 0.236 | 250 | 19.4 |

| 14a |

|

4537 | 1.27 | 280 | 10.7 |

| 14b |

|

1762 | 0.7506 | 426 | 44.1 |

| 14d |

|

3.00E+03 | 0.754 | 252 | 24.2 |

Data were fit globally using the 1:1 Langmuir binding model. Equilibrium dissociation constants (KD) were calculated from the ratio of the dissociation and association rate constants.

Table 5.

SPR results for M. tuberculosis MmpL3-ligand binding using the 2-state modela

| Comp. No | Chemical structure | KD, μM 2-state | Residuals χ2 (RU)2 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 8a |

|

429.8 | 1.098 | 0.005315 | 0.02222 | 2060 | 34.5 |

| 8b |

|

4958 | 1.613 | 0.01084 | 0.03486 | 248 | 9.52 |

| 8c |

|

5473 | 1.284 | 0.006994 | 0.03012 | 190 | 7.57 |

| 12 |

|

7245 | 1.05 | 0.007539 | 0.03558 | 120 | 15 |

| 8d |

|

7325 | 0.9488 | 0.00968 | 0.04246 | 106 | 12.2 |

| 8e |

|

5151 | 0.7008 | 0.009897 | 0.03763 | 108 | 7.48 |

| 8f |

|

4642 | 0.4552 | 0.008637 | 0.03992 | 81 | 38.9 |

| 8g |

|

6462 | 0.5715 | 0.006528 | 0.03248 | 74 | 30.3 |

| 8h |

|

2.59E+04 | 4.085 | 0.00526 | 0.03247 | 136 | 29.5 |

| 8i |

|

3946 | 0.434 | 0.006253 | 0.03057 | 91 | 31.1 |

| 7a |

|

1.23E+04 | 4.816 | 0.01065 | 0.04928 | 321 | 4.38 |

| 14a |

|

2345 | 2.023 | 0.009004 | 0.02642 | 644 | 4.18 |

| 14b |

|

1917 | 1.363 | 0.009268 | 0.02741 | 531 | 12.6 |

| 14d |

|

3277 | 1.04 | 0.005907 | 0.03103 | 267 | 9.59 |

Data were fit globally using the two-states model. ka1, kd1, ka2, and kd2 are microscopic rate constants. Equilibrium dissociation constants (KD) were calculated from the ratio of the dissociation and association rate constants.

What has been puzzling about the SPR result for SQ109 binding to M. tuberculosis MmpL3 (MtMmpL3) reported previously is that the KD value for SQ109 (8a) was high, ~ 1.5 mM, while the IC50 against M. tuberculosis itself (IC50 ≈ 0.4–1 μM, Table 1) is very low. The IC50 for M. smegmatis (Table 1) is higher, ~2.4 μM, but again much lower that the KD value measured against MtMmpL3 (Table 4). The KD values for all 14 compounds tested are lower than found with SQ109 (8a) (Tables 4 and 5). What is of particular interest is that, compared to SQ109 (8a), there is a general decrease in the KD value, meaning tighter binding to MmpL3, as the compounds become more hydrophobic. For example, using the KD values from the two-state binding model that are shown in Table 5, with SQ109 (8a) and the adamantyl C-2 substituted species (see structure of R in Scheme 1) we found the following KD values R=H (8a or SQ109, 2060 μM); R=methyl (8b, 248 μM); R=ethyl (8c, 190 μM); R=n-propyl (8d, 106 μM); R=n-butyl (8e, 108 μM); R=n-hexyl (8f, 81 μM). That is, as the R substituent at C-2 (which is an H in SQ109) becomes larger and more hydrophobic, the KD decreased. A similar effect was observed with phenyl (8h, 136 μM) and benzyl (8g, 74 μM) C-2 substituents (Table 5). The C-1 dimethylmethylene analog 12 had a KD of 106 μΜ, which was close to the isomeric C-2 n-propyl 8d which had a KD of 120 μM. The thiazole 8i was also a relatively good binder with KD ~90 μM (Table 4).

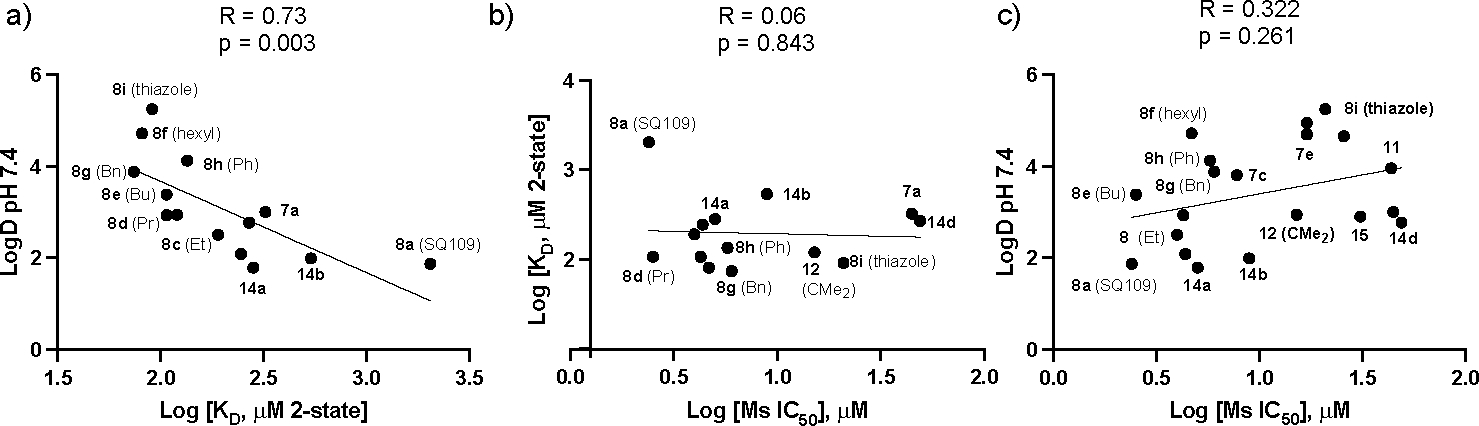

As can be seen in Figure 3a, there is a significant correlation between the log KD values for all 14 compounds (i.e. including the four amides) and logD7.4, the computed oil-water partition coefficient at pH=7.4, with a Pearson R coefficient R=0.73 and p<0.003. That is, the strongest binding occurs with the most hydrophobic species. This is not unexpected, however, we find no correlation between cell growth inhibition and log KD, Figure 3b, or between cell growth inhibition and logD7.4, for all of the compounds tested, Figure 3c. Essentially the same results were obtained using either the 1:1 or 2-state models for KD.

Figure 3.

Graphs showing correlations between log KD, LogD7.4 and M. smegmatis cell growth inhibition. (a) Log KD versus logD7.4; R=0.73, p=0.003. (b) Log Ms IC50 and log KD; R=0.06, p=0.843 (c) Log Ms IC50 and logD7.4, for all compounds tested; R=0.322, p=0.261. Selected compound numbers are shown.

One possible reason for this is that while the more hydrophobic species 8b-i, 12 do bind more strongly to MmpL3 compared to SQ109 (8a), there may be unfavorable steric interactions with the highly glycosylated mycobacterial cell wall with the larger substituents, 31, 32 or with any transporters that may facilitate cell entry. It is also of course possible that there may be other targets such as MenA, MenG, involved in menaquinone biosynthesis, which could contribute to the observed differences in activities. 23 The activity of other proteins may also be targeted, together with binding to lipid membranes, affecting uncoupling activity and the proton motive force, as well as affecting lipid membrane inhibitor-concentrations (and thus, activity). The importance of steric effects in influencing poor cell uptake in the mycobacteria seems likely since as can be seen in Table 1 and Figure 3, the bulky adamantyl C-2 phenylthiazoyl (8i) analog—while exhibiting stronger binding to MmpL3 than does SQ109 (8a) —had only very weak activity against M. smegmatis cell growth. With M. tuberculosis HN878, where full dose-response curves were obtained, there was a similar trend, with SQ109 (8a) being most active (IC50 = 0.4 μM), followed by the C-2 Me analog 8b (IC50 = 0.8 μM), the ethyl analog 8c (IC50 = 1.6 μM), n-propyl (8d and n-hexyl (8f) analogs both having IC50 = 3 μM. In M. tuberculosis HN878, the phenyl (8h) and benzyl (8g) analogs had the same activity, IC50 = 1.6 μM. Overall then, the SPR results do not support the idea that MmpL3 is the major target for SQ109 (8a) or analog activity in the mycobacteria, meaning that other targets such as uncoupling activity, or indeed other mechanisms of action, are involved, consistent of course with the activity (for SQ109) seen against other bacteria, as well as against yeasts, fungi and protozoa.

Membrane–inhibitor interactions.

Another target for SQ109 (8a) in both bacteria and protozoa involves effects on the proton motive force, and Ca2+ homeostasis—both of which involve cell membranes. In previous work 33 we investigated the pH dependence of the activity of inhibitors, including SQ109 analogs, on M. smegmatis cell growth inhibition (IC50 values) and found that there were correlations between the IC50 values and uncoupling (ΔpH collapse), as well as with changes in the gel-to-liquid crystal phase transition temperature (Tm) in DSC experiments with lipid bilayer membranes, and with computed logD values. We showed 33 that cell growth inhibition activity increased from pH 5 to 7 to 9, and this correlated with increasing uncoupler activity, decreasing Tm values, and increasing logD values. That is, increased hydrophobicity results in more membrane binding leading to more fluidity and uncoupling activity, as well as providing a reservoir of inhibitor for binding to membrane protein targets. Such effects could be important in the protozoa.

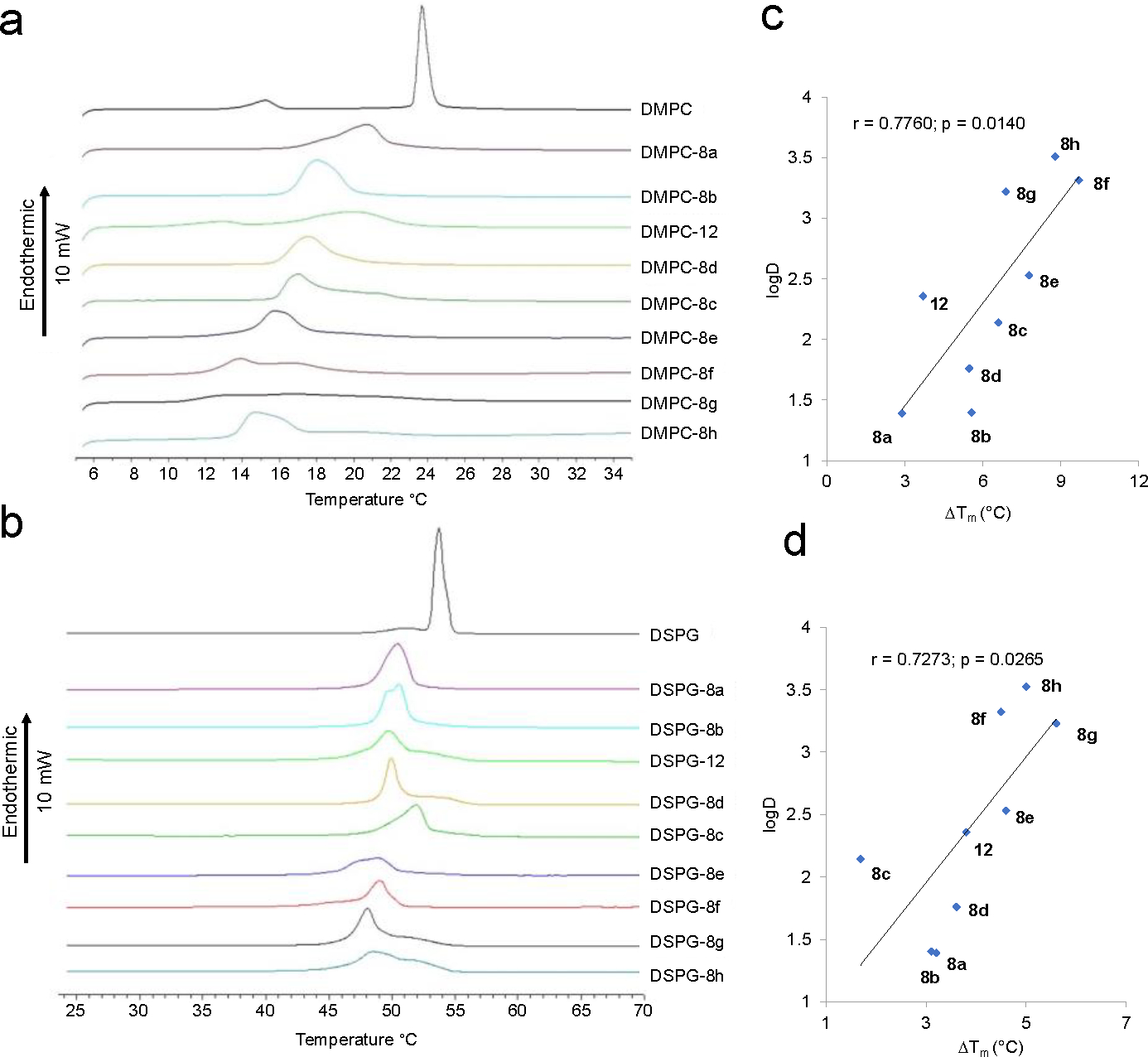

We therefore next used DSC to investigate the effects of SQ109 (8a) and analogs 8b-g, 12 on the gel-to-liquid crystal phase transition in 1,2-dimyristoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (DMPC) bilayers (10 wt % inhibitor, pH 7.4) as well as with 1,2-distearoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoglycerol (DSPG) bilayers. The zwitterionic DMPC is a model for protozoal membranes which are primarily phosphatidylcholines and phosphatidylethanolamines, while the DSPG is an anionic species and is a model for the mycobacterial inner membrane lipids. DSC scans of each compound during heating (Figures 4a,b, Table 6) and cooling (Figure S3, S4, Table S1) were then compared with measurements on DMPC or DSPG alone. The DSC scans of the main transition for the DMPC systems (Figure 4a) showed that compared to DMPC without any inhibitor, SQ109 (8a), 12 decreased Tm by 3–4 °C, while 8b (Me), 8c (Et), 8d (Pr), 8e (Bu), 8f (Hex), 8g (Bn) and 8h (Ph) decreased Tm by ca. 5.6, 6.6, 6, 7.8, 9.7, 6.9 and 8.8 °C, respectively (Table 6). The DSC scans for DSPG systems in Figure 4b showed that compared to DSPG alone SQ109 (8a), 8b (Me), 12 and 8d (Pr) decreased the Tm by 3–4 °C, while 8e (Bu), 8f (Hex), 8g (Bn) and 8h (Ph) decreased Tm by ~5 °C (Table 6).

Figure 4.

DSC results for DMPC and DSPG with and without SQ109 (8a) and 8 ethylenediamine analogs and correlations between ΔTm and logD7.4. (a) DSC heating scans for DMPC. (b) DSC heating scans for DSPG. (c) Correlation between logD7.4 and the decrease in Tm (ΔTm) for DMPC. Pearson r-coefficient = 0.776, p = 0.014. (d) as in (c) but for DSPG. Pearson r-coefficient = 0.727, p = 0.026.

Table 6.

DSC results (heating) for the DMPC:SQ109 analog systems in DMPC hydrated with PBS (phosphate buffered saline, pH=7.4) and calculated logD7.4 values at the same pH.

| Sample | T m | ΔT1/2 | ΔH | Sample | T m | ΔT1/2 | ΔH | logD7.4 |

| DMPC | 23.5 | 0.59 | 30.3 | DSPG | 53.6 | 0.9 | 48.1 | |

| DMPC:8a (H) | 20.6 | 2.6 | 23.3 | DSPG:8a (H) | 50.4 | 2.1 | 54.0 | 1.39 |

| DMPC:8b (Me) | 17.9 | 2.2 | 25.6 | DSPG:8b (Me) | 50.5 | 2.0 | 53.2 | 1.40 |

| DMPC:12 | 19.8 | 4.1 | 17.8 | DSPG:12 | 49.8 | 2.4 | 55.8 | 2.36 |

| DMPC:8d (Pr) | 17.5 | 2.2 | 22.6 | DSPG:8d (Pr) | 50.0 | 1.1 | 48.1 | 2.14 |

| DMPC:8c (Et) | 16.9 | 2.0 | 24.0 | DSPG:8c (Et) | 51.9 | 2.5 | 49.9 | 1.76 |

| DMPC:8e (Bu) | 15.7 | 2.2 | 24.4 | DSPG:8e (Bu) | 49.0 | 3.6 | 38.5 | 2.53 |

| DMPC:8f (Hex) | 13.8 | 5.1 | 24.6 | DSPG:8f (Hex) | 49.1 | 1.7 | 36.6 | 3.32 |

| DMPC:8g (Bn) | 16.6 | 10 | 21.6 | DSPG:8g (Bn) | 48.0 | 1.7 | 55.5 | 3.23 |

| DMPC: 8h (Ph) | 14.7 | 2.7 | 29.8 | DSPG: 8h (Ph) | 48.6 | 5.3 | 55.4 | 3.52 |

m: main transition; Tm (°C), temperature at which heat capacity (ΔCP) at constant pressure is a maximum; ΔT1/2 (°C), half width at half peak height of the main transition; ΔH (kJ mol−1), main transition enthalpy normalized per g of the bilayer. Results were the same after two repeats.

These results indicated that SQ109 (8a) and the analogs incorporate into the phospholipid bilayers and fluidize the membranes, generating a structure that melts at a lower temperature, Tm, compared to the pure membrane, and this effect was more pronounced as the size of the inhibitor increases. Compared to the pure DMPC bilayer, SQ109 (8a) or 8b (Me), 8c (Et), 8d (Pr), 8e (Bu), 8h (Ph), 12 broadened the main transition peak by ΔΤ1/2 = 0.7–2.4 ⁰C (Table 6), while compounds 12, 8f (Hex) and 8g (Bn) broadened by ΔΤ1/2 = 3.5, 4.4, 9.6 °C, due most likely to the formation of inhomogeneous domains that melt over a broad temperature range. Similarly, compared to the pure DSPG bilayer, SQ109 (8a), 8b (Me), 8c (Et), 8d (Pr), 8f (Hex), 8g (Bn) and 12 broadened the main transition peak by ΔΤ1/2 = 0.2–1.6 ⁰C; while compounds 8e (Bu) and 8h (Ph) broadened the peak by 2.7 and 4.4 °C, respectively, again due most likely to the formation of inhomogeneous domains that melt over a broad temperature range.34 However, rather than simply a very large broadening of the gel-to-liquid crystal phase transition, as seen with the fluidizing effect of cholesterol,35 in all cases Tm shifted to lower temperatures. The DSC thermograms obtained on cooling, Figure S3, S4 and Table S1, showed a similar decrease in Tm as seen with DMPC on heating but a more complex hysteresis effect with DSPG.

What is perhaps surprising is that, in general, the effects on Tm seen with DPMC were clearly larger than those seen with DSPG. What might the reasons for this be? Interestingly, similar effects have been reported for the binding of another cationic antibiotic, the anthracycline pirarubicin 36 binding to DSPG and to distearoylphosphatidylcholine (DSPC), in which the acyl chain lengths are the same (C18). In that work 36 it was proposed (based on the results of DSC, Fourier transform infra-red spectroscopy and quantum chemical calculations) that the ammonium group of the antibiotic bound more tightly to the PO2− group in DSPG than to the PO2− group in DSPC, due to charge repulsion with the choline Me3N+ group in DSPC, and that this resulted in decreased drug incorporation into the lipid bilayer. These observations led us to the following model for SQ109-DMPC/DSPG interactions. First, incorporation of the SQ109 geranyl (C10) chain into the lipid bilayer was expected to decrease Tm in the same way that incorporation of a farnesyl (C15) group in farnesol 37 decreased and broadened the DMPC main transition, due to disrupted packing of the DMPC alkyl chains. A similar effect would be predicted for both DMPC as well as DSPG, but the effect would be larger with the shorter chain species, DMPC, which has a similar alkyl chain length to that of the geranyl chain in SQ109. The enthalpy of the phase transition was also of course much larger with the longer chain, DSPG, species, Table 6. However, there is a second interaction that may also be of importance, the electrostatic interaction between the PO2− group in the phospholipid and the protonated ethylenediamine group of SQ109 (8a) (or analog). Binding of cationic species (e.g. Ca2+, UO22+) to anionic lipids increases Tm 38 and it is possible that SQ109 (8a) may help “cross-link” the anionic DSPG, thereby off-setting to some extent the fluidizing effect of the geranyl group in SQ109 (8a).

What is also of particular interest about the DSC results shown in Figure 4a,b is that there are good correlations between the change in Tm that correlates with the computed logD7.4 of the inhibitor, Figures 3c and 3d, with a Pearson r-coefficient = 0.776, p = 0.014 for DMPC and a Pearson r-coefficient = 0.727, p = 0.026 for DSPG. For the cooling curves, there was again a correlation between ΔTm and logD with DMPC (r = 0.75, p = 0.021) but there were more complex effects with DSPG (Figure S4). The stronger binding of the more hydrophobic analogs to lipid membranes would be expected to result in more cell activity, either by increasing membrane fluidity/uncoupling activity or by providing higher membrane concentrations for a membrane protein target. However, the more hydrophobic analogs were not found to be more active against M. tuberculosis or M. smegmatis, but we did find increased activity (a 4–8 fold decrease in MIC) in M. abscessuss, as well as large increases in activity against B. subtilis and E. coli, Table 1, and with P. falciparum (with the phenyl and benzyl analogs). The DSC results thus suggest that the larger analogs may simply not reach their target(s) in M. tuberculosis and M. smegmatis, e.g. due to unfavorable steric interactions with the mycolyl-arabinogalactan-peptidoglycan cell wall.

Microsomal stability and solubility.

Finally, we investigated the microsomal stability of analog 8b (Me) and analog 8h (Ph) as well as of SQ109 (8a) in human, mice and rat liver microsomes. In previous work, Jia et al,39, 40 found that SQ109 was metabolized in rats, mice, and dogs with [14C-SQ109] half-life values of 5 h in mice39 and >5 h in rats and dogs40. Using liver microsomes and cells expressing P450 enzymes, they concluded that SQ109 was rapidly metabolized to oxygenated species, and we recently reported their structures26. It was thus of interest to investigate whether SQ109 analogs were also metabolized, using liver microsome assays. We found that, as expected 39, 40 SQ109 (8a) was rapidly metabolized (Table S2), while the methyl analog 8b was ~2–4x more stable (% remanent at 60 minutes) than was SQ109 (8a). The phenyl analog 8h had the same % remanent as SQ109 (8a) (at 60 minutes) in mice microsomes, though was more rapidly metabolized in human and rat liver microsomes. The intrinsic clearance rates (CLint) in mice microsomes were essentially the same as found with SQ109 for 8b and 8h but were about twice as large as found with SQ109 (8a) in the human and rat liver microsome assays (Table S2). While all of these rates are high, it is of course well known that SQ109 (8a) is, nevertheless, effective against M. tuberculosis in humans where it accumulates in the lungs, and in addition, it has efficacy against both trypanosomatid as well as apicomplexan parasites, in mice models of infection, 41 where the lungs are not targeted. Clearly, it will be of interest to determine how e.g. 8h is metabolized, and whether any metabolites have activity, and further work on this topic as well as on the synthesis of 8h analogs, is of interest. To determine the susceptibility of the phenyl group in 8h to oxygenation we used 3 computer programs: the GloryFame2 program,42, 43 the Xenosite program44 and the SmartCyp program.45 Results are shown in Figure S5. Based on these results it is apparent that in general the major sites targeted by P450 cytochromes are—as with SQ109 (8a) itself— at the ends of the molecule (the terminal methyl groups and the adamantyl group) and at C10, but the phenyl group is also a potential target and may form a phenol (C19, Figure S5a, GloryFame2 result; Figure S5c, SmartCyp result) or a quinone (Figure S5b) moiety.

CONCLUSIONS

In this work we report the synthesis of analogs of the anti-tubercular drug candidate SQ109 (8a), an ethylenediamine-based inhibitor of MmpL3 currently undergoing clinical trials that also has activity against a broad range of bacteria, protozoa and even some yeasts/fungi. We synthesized a series of 19 SQ109 (8a) analogs containing adamantane C-2 alkyl, aryl or heteroaryl adamantyl groups (Me, Et, Pr, Bu, Ph, Bn, Hex, 4-phenylthiazol-2-yl, with ethylenediamine or aminoamide linkers between the adamantyl and geranyl groups, in addition to an adamantyl C-1 dimethylmethylene analog. We then tested SQ109 (8a) and the analogs against five bacteria: M. smegmatis, M. tuberculosis (3 strains), M. abscessus (two strains), B. subtilis and E. coli, as well as against five protozoa, T. brucei, T. cruzi (epimastigotes and amastigotes), L. donovani, L. mexicana and P. falciparum (asexual blood stages). There was good activity of ethylenediamine analogs containing small substituents against the mycobacteria, though activity was generally less than with the SQ109 parent molecule. The interesting exception was in M. abscessus where we found two SQ109 analogs, the butyl (8e) and benzyl (8g) species, in which activity was ~4–8 fold higher than found with SQ109 (8a). Moreover, activity was the same against a highly drug-resistant Μ. abscessus strain, harboring a A309P mutation located in the transmembrane domain in MmpL3, indicating that MmpL3 is not a major target in this species. We then used SPR to investigate the binding of SQ109, nine ethylenediamine analogs and four amide analogs to a mycobacterial MmpL3 protein target finding that tighter MmpL3 binding correlated with increasing ligand hydrophobicity with r=0.73, p<0.003 for the logKD/logD7.4 correlation. However, there were no significant correlations between cell growth inhibition and either logD or logKD. The low activity of the more potent MmpL3 binders against MmpL3-containing bacteria suggests that MmpL3 inhibitors with large C-2 substituents may not be able to penetrate the cell wall. Using DSC, we found that these inhibitors caused larger decreases in Tm than found with SQ109 (8a), indicating efficient accumulation in lipid membranes and there were clear correlations between ΔTm and logD7.4 for both DMPC (r = 0.776, p = 0.014) as well as for DSPG (r = 0.727, p = 0.026). Taken together, the SPR and DSC results are consistent with the idea that the larger, more potent MmpL3 inhibitors are less effective than is SQ109 (8a) in penetrating the arabinogalactan-peptidoglycan cell wall in mycobacteria. In contrast, in B. subtilis and E. coli, several analogs were more potent than was SQ109 (8a). In these organisms, MmpL3 is absent as is the mycolyl-arabinogalactan-peptidoglycan cell wall, although the mechanism of action of SQ109 (8a) itself in these bacteria remains to reported. On the other hand, in the trypanosomatid parasites, SQ109 (8a) is reported to act as a protonophore uncoupler that also affects Ca2+ homeostasis. In these organisms there is again no cell wall, and many of the analogs are active against the parasites. With the malaria parasite P. falciparum, there is likewise no cell wall and no MmpL3 and SQ109 and analog activity could similarly be dependent on their protonophore properties. We found that several analogs had 4–10x increased activity over SQ109 as well as low toxicity against the HepG2 human cell line making them of interest as a new anti-malarial drug hit, warranting further development of these more-bulky analogs, as antimalarial drug leads.

METHODS

General.

All solvents and chemicals were used as purchased without further purification except for Me3SiCl which was distilled just before use. Dry ether and dry dichloromethane were prepared by leaving the solvents over CaH2 for 24 h before use. Anhydrous THF was purchased in sealed bottles from Acros Organics. The progress of all reactions was monitored on Merck precoated silica gel plates (with fluorescence indicator UV254) using diethyl ether/n-hexane, n-hexane/ethyl acetate or chloroform/methanol as eluents. Column chromatography was performed with Acros Organics silica gel 60A 40–60 μm with the solvent mixtures described in the experiment section. Compounds’ spots were visualized based on their absorbance at 254 nm. The structures of 8a-i, 12 were identified using 1H, 13C and LC-MS. High-resolution mass spectrometry (HRMS) was carried using a UHR-TOF maXis 4G instrument (Bruker Daltonics, Bremen, Germany). 1H NMR spectra were recorded in CDCl3 solutions for the amines and CD3OD solutions for the fumarate salts of amines on Bruker NMR spectrometers, the DRX 200 or DRX 400 or DRX 600 at 200 MHz or 400 or 600 MHz, respectively; 13C NMR spectra were recorded at 50 MHz, 100 or 150 MHz, respectively. Carbon multiplicities were assigned using the DEPT experiment. 2D NMR HMQC and COSY spectra were used for the elucidation of the structures of intermediates and final products and NMR peaks assignments. All compounds were confirmed to have greater than 95% purity via HPLC-MS analysis. We described 22 an improved preparation of geranylamine (2) and the preparation of 6a, 7a, 13, 14a, 8a was also reported in ref 22; the preparation of geranylamine (2) and the raw materials for amines 5b-h, 12 were the corresponding adamantanols obtained from the reaction of 2-amantanone with alkyl lithium reagents. The tertiary alcohols were then reacted with a mixture of sodium azide and trifluoroacetic acid in dichloromethane and the produced tertiary alkyl azides were reduced with LiAlH4 in ether at rt to afford the amines 5b-h, 12. 18, 20 The 2-adamantylamine 5a was prepared from reduction of 2-adamantanone oxime with LiAlH4 in THF. The preparation of intermediates 2, 5i, 6a-i, 10, 13 and of 7a, 14a and SQ109 (8a) published in ref 22 can be found in the Supporting Information.

2-((3,7-Dimethylocta-2,6-dien-1-yl)amino)-N-(2-methyl-2-adamantanyl)acetamide, 7b

Bromoacetamide 6b (660 mg, 2.31 mmol) in dry THF (13 mL) was added dropwise at 0 °C to a stirred mixture of geranylamine (2) (353 mg, 2.31 mmol) and triethylamine (233 mg, 2.31 mmol) in dry THF (20 mL). The stirring continued for 48 h at room temperature. Then the aqueous phase was extracted twice with dichloromethane, the combined organic extracts were evaporated in vacuo and the crude product was purified through column chromatography using a. ether:n-hexane (1:1), b. CHCl3:MeOH (9:1), as eluents. Acetamide 7b was obtained as a pale yellow oil; yield 744 mg (90%); 1H-NMR (CDCl3, 400 MHz) δ (ppm) 1.51 (s, 3H, 2-adamantyl-CH3), 1.59 (s, 3H, 8-geranyl), 1.64 (s, 3H, 7-geranyl CH3), 1.67 (s, 3H, 3-geranyl CH3), 1.80 (s, 2H, 5,7-adamantyl), 1.96–2.05 (m, 6H, 4,5-H, 8ax,10ax-adamantyl), 2.18 (d, J = 12 Hz, 2H, 4ax,9ax-adamantyl) 3.17 (d, J = 7.4 Hz, 2H, 1-geranyl) 3.28–3.30 (m, 2H, COCH2NH), 5.07 (m, 1H, 6-geranyl), 5.23 (m, 1H, 2-geranyl); 13C-NMR (CDCl3, 100MHz) δ (ppm) 16.7 (3-geranyl CH3), 18.1 (8-geranyl), 23.5 (2-adamantyl-CH3), 26.0 (7-geranyl CH3), 27.2 (5-geranyl), 27.2 (5-adamantyl), 27.8 (7-adamantyl), 33.6 (4,9-adamantyl), 35.7 (1,3-adamantyl), 38.9 (8,10-adamantyl), 39.9 (6-adamantyl), 40.1 (4-geranyl), 47.3 (1-geranyl), 58.5 (2-adamantyl), 59.7 (COCH2NH), 123.1 (2-geranyl), 124.1 (6-geranyl), 132.2 (7-geranyl), 138.5 (3-geranyl), 168.9 (C=O); HRMS (ESI-TOF (+)) m/z [M + H]+ calculated for [C23H39N2O]+ 359.3057, found 359.3062.

N-(3,7-dimethylocta-2,6-dien-1-yl)-N´-(2-methyl-2-adamantanyl)ethane-1,2-diamine, 8b

Acetamide 7b (790 mg, 2.21 mmol) in dry dichloromethane (10 mL) was stirred at 0–5 °C for 15 min under argon atmosphere. Recently distilled trimethylsilyl chloride (288 μL, 2.65 mmol) was then added at the same temperature and the mixture was stirred for another 15 min. A suspension of LiAlH4 (117 mg, 3.09 mmol) in a small quantity of THF was added at −10–0°C and the stirring continued for 2.5 h at the same temperature. The mixture was then treated with NaOH 10%, the resulting inorganic precipitate was filtered off, the organic phase was separated and the aqueous phase was extracted twice with dichloromethane. The combined organic extracts were evaporated in vacuo and the crude product was dissolved in dichloromethane and washed with brine. After the evaporation of the solvent, the crude product was purified through column chromatography using a. CHCl3:MeOH (9:1), b. CHCl3:MeOH:ΝΗ3 (88:10:2), as system solvents to afford diamine 8b as a pale yellow oil; yield 190 mg (25%); 1H-NMR (CDCl3, 400 MHz) δ (ppm) 1.21 (s, 3H, 2-adamantyl-CH3), 1.51 (d, J = 12Hz, 2H, 4eq,9eq-adamantyl), 1.53 (s, 2H, 8eq,10eq-adamantyl), 1.59 (s, 3H, 8-geranyl), 1.63 (s, 3H, 7-geranyl CH3), 1.67 (s, 3H, 3-geranyl CH3), 1.80 (d, J = 12Hz, 2Η, 5,7-adamantyl), 1.98–2.12 (m, 4H, 4,5-geranyl), 2.64 (t, J = 6Hz, 2H, NHCH2CH2NH-geranyl), 2.74 (t, J = 6Hz, 2H, NHCH2CH2NH-geranyl), 3.23 (d, J = 7.0 Hz, 2H, 1-geranyl), 5.09 (m, 1H, 6-geranyl), 5.25 (m, 1H, 2-geranyl); 13C NMR (CDCl3, 100MHz) δ (ppm) 16.6 (3-geranyl CH3), 18.0 (8-geranyl), 23.2 (2-adamantyl CH3), 26.0 (7-adamanytyl CH3), 26.9 (5-geranyl), 27.5 (5-adamantyl), 28.4 (7-adamantyl), 32.9 (4,9-adamantyl), 34.5 (1,3-adamantyl), 36.3 (8,10-adamantyl), 39.3 (6-adamantyl), 40.0 (4-geranyl), 40.2 (1-geranyl), 47.4 (NHCH2CH2NH-geranyl), 50.1 (NHCH2CH2NH-geranyl), 56.3 (2-adamantyl), 123.3 (2-geranyl), 124.5 (6-geranyl), 131.8 (7-geranyl), 138.0 (3-geranyl); HRMS (ESI-TOF (+)) m/z [M + H]+ calculated for [C23H41N2]+ 345.3264, found 345.3269; Purity of the product determined by HPLC-MS: 96.4%.

N-(3,7-dimethylocta-2,6-dien-1-yl)-2-((2-methyl-2-adamantanyl)amino)acetamide, 14b

Bromoacetamide 13 (664 mg, 2.42 mmol) in dry THF (14 mL) was added dropwise at 0 °C to a stirred solution of 2-methyl-2-adamantanamine (5b) (400 mg, 2.42 mmol) and triethylamine (244 mg, 2.42 mmol) in dry THF (24 mL). The stirring continued for 48 h at room temperature. Then the aqueous phase was extracted twice with dichloromethane, the combined organic extracts were evaporated in vacuo and the crude product was purified through column chromatography using a. ether:n-hexane (1:1), b. CHCl3:MeOH (9:1), as eluents. Acetamide 14b was obtained as a yellow oil; yield 520 mg (60%); 1H-NMR (CDCl3, 400 MHz) δ (ppm) 1.14 (s, 3H, 2-adamantyl CH3), 1.55 (d, J = 12Hz, 2H, 4eq,9eq-adamantyl), 1.59 (s, 3H, 8-geranyl), 1.67 (s, 6H, 3,7-geranyl CH3), 1.91–1.94 (m, 2H, 4ax,9ax-adamantyl), 1.99–2.08 (m, 4H, 4,5-geranyl), 3.20 (s, 2H, NHCH2CO), 3.86 (t, J = 6 Hz, 2H, 1-geranyl), 5.08 (m, 1H, 6-geranyl), 5.19 (m, 1H, 2-geranyl). Hydrochloride salt; 13C-NMR (CD3OD, 100MHz,) δ(ppm) 17.2 (3-geranyl CH3), 18.6 (8-geranyl), 21.4 (2-adamanyl CH3), 26.7 (7-geranyl CH3), 28.3 (5-geranyl), 28.4 (5-adamantyl), 29.1 (7-adamantyl), 33.4 (4,9-adamantyl), 35.4 (8,10-adamantyl), 36.1 (1,3-adamantyl), 39.6 (6-adamantyl), 39.9 (4-geranyl), 41.4 (1-C), 43.3 (NHCH2CO), 67.3 (2-adamantyl), 121.3 (2-geranyl), 125.8 (6-geranyl), 133.5 (7-geranyl), 142.1 (3-geranyl), 167.1 (C=O); HRMS (ESI-TOF (+)) m/z [M + H]+ calculated for [C23H39N2O]+ 359.3057, found 359.3057; Purity of the product determined by HPLC-MS: 98.0%.

N-(2-(adamantan-1-yl)propan-2-yl)-2-((3,7-dimethylocta-2,6-dien-1-yl)amino)acetamide, 11

Bromoacetamide 10 (680 mg, 2.16 mmol) in dry THF (15 mL) was added dropwise at 0 °C to a stirred solution of geranylamine (2) (330 mg, 2.16 mmol) and triethylamine (218 mg, 2.16 mmol) in dry THF (20 mL). The stirring continued for 48 h at room temperature. Then the aqueous phase was extracted twice with dichloromethane, the combined organic extracts were evaporated in vacuo and the crude product was purified through column chromatography using a. ether:n-hexane (1:1), b. CHCl3:MeOH (9:1), as eluents. Acetamide 11 was obtained as a yellow oil; yield 750 mg (90%); 1H-NMR (CDCl3, 400 MHz) δ (ppm) 1.34 (s, 6H, 1-adamantyl C(CH3)2), 1.59–1.71 (m, 21H, 2,4,6,8,9,10-adamantyl, 8-geranyl, 3,7-geranyl CH3), 2.01–2.09 (m, 7H, 3,5,7-adamantyl, 4,5-geranyl), 3.15 (d, J = 7.4 Hz, 2H, 1-geranyl), 3.23–3.26 (m, 2H, COCH2NH), 5.07 (m, 1H, 6-geranyl), 5.22 (m, 1H, 2-geranyl); 13C-NMR (CDCl3, 100MHz) δ(ppm) 16.7 (3-geranyl CH3), 18.0 (8-geranyl), 21.4 (1-adamanyl C(CH3)2), 21.9 (1-adamantyl C(CH3)2), 26.0 (7-geranyl CH3), 26.8 (5-geranyl), 28.9 (3,5,7-adamantyl C), 36.5 (4,6,10-adamantyl), 37.4 (2,8,9-adamantanyl), 39.5 (1-adamantanyl), 39.8 (4-geranyl), 40.0 (1-geranyl), 47.3 (COCH2NH), 59.01 (1-adamanyl C(CH3)2), 119.8 (2-geranyl), 124.2 (6-geranyl), 132.1 (7-geranyl), 140.4 (3-geranyl), 169.1 (C=O); HRMS (ESI-TOF (+)) m/z [M + H]+ calculated for [C25H43N2O]+ 387.337, found 387.337; Purity of the product determined by HPLC-MS: 99.2%.

N-(3,7-dimethylocta-2,6-dien-1-yl)-N´-(2-(adamantan-1-yl)propan-2-yl)ethane-1,2-diamine, 12

Acetamide 11 (280 mg, 0.72 mmol) in dry dichloromethane (4 mL) was stirred at 0–5 °C for 15 min under argon atmosphere of Ar. Recently distilled trimethylsilyl chloride (94 μL, 0.87 mmol) was then added at the same temperature and the mixture was stirred for another 15 min. A suspension of LiAlH4 (38.3 mg, 1.01 mmol) in a small quantity of THF was added at −10–0°C and the stirring continued for 2.5 h at the same temperature. The mixture was treated with NaOH 10%, the resulting inorganic precipitate was filtered off, the organic phase was separated and the aqueous phase was extracted twice with dichloromethane. The combined organic extracts were evaporated in vacuo and the crude product was dissolved in dichloromethane and washed with brine. After the evaporation of the solvent, the crude product was purified through column chromatography using a. CHCl3:MeOH (9:1), b. CHCl3:MeOH:ΝΗ3 (88:10:2), as system solvents, to afford diamine 12 as a yellow oil; yield 70mg (26%); 1H-NMR (CDCl3, 400 MHz) δ (ppm) 0.96 (s, 6H, 1-adamantyl C(CH3)2), 1.60–1.67 (m, 21H, 2,4,6,8,9,10-adamantane H, 8-geranyl, 3,7-geranyl CH3), 2.01–2.09 (m, 7H, 3,5,7-adamantyl, 4,5-geranyl), 2.70 (s, 4H, NHCH2CH2NH), 3.23 (d, J = 7.0 Hz, 2H, 1-geranyl), 5.09 (m, 1H, 6-geranyl), 5.26 (m, 1H, 2-geranyl); 13C NMR (CDCl3, 100MHz) δ(ppm) 16.6 (3-geranyl CH3), 18.0 (8-geranyl), 20.7 (1-adamantyl C(CH3)2), 26.0 (7-geranyl CH3), 26.9 (5-geranyl), 29.2 (3,7,5-adamantyl), 36.5 (4,6,10-adamantyl), 37.6 (2,8,9-adamantyl), 39.2 (1-adamantyl), 40.0 (4-geranyl), 41.9 (1-geranyl), 47.2 (NHCH2CH2NH-geranyl), 50.2 (NHCH2CH2NH-geranyl), 57.2 (1-adamantyl C(CH3)2), 123.0 (2-geranyl), 124.5 (6-geranyl), 131.9 (7-geranyl), 138.3 (3-geranyl); HRMS (ESI-TOF (+)) m/z [M + H]+ calculated for [C25H45N2]+ 373.3577, found 373.357; Purity of the product determined by HPLC-MS: 96.6%.

2-((2-(Adamantan-1-yl)propan-2-yl)amino)-N-(3,7-dimethylocta-2,6-dien-1-yl)acetamide, 15

Bromoacetamide 13 (200 mg, 0.73 mmol) in dry THF (6 mL) was added dropwise at 0 °C to a stirred solution of 2-(1-adamantanyl)propan-2-amine (9) (141 mg, 0.73 mmol) and triethylamine (74 mg, 0.73 mmol) in dry THF (8 mL). The stirring continued for 48 h at room temperature. Then the aqueous phase was extracted twice with dichloromethane, the combined organic extracts were evaporated in vacuo and the crude product was purified through column chromatography using a. ether:n-hexane (1:1), b. CHCl3:MeOH (9:1), as eluents. Acetamide 15 was obtained as a yellow oil; yield 125 mg (44%); 1H-NMR (CDCl3, 400 MHz) δ (ppm) 0.92 (s, 6H, 1-adamantyl C(CH3)2), 1.59–1.73 (m, 21H, 2,4,6,8,9,10-adamantyl, 8-geranyl, 3,7-geranyl CH3), 2.01–2.10 (m, 7H, 3,5,7-adamantyl, 4,5-geranyl), 3.28 (s, 2H, NHCH2CO), 3.85 (t, J = 6.2 Hz, 2H, 1-geranyl), 5.08 (m, 1H, 6-geranyl), 5.21 (m, 1H, 2-geranyl); 13C-NMR (CDCl3, 100MHz) δ(ppm) 16.7 (3-geranyl CH3), 18.0 (8-geranyl), 20.3 (1-adamantyl C(CH3)2), 26.0 (7-geranyl CH3), 26.9 (5-geranyl), 29.0 (3,5,7-adamantyl), 36.5 (4,6,10-adamantyl), 37.4 (2,8,9-adamantyl), 37.9 (1-adamantyl), 39.0 (4-geranyl), 39.8 (1-geranyl), 46.1 (NHCH2CO), 120.3 (2-geranyl), 124.2 (6-geranyl), 132.0 (7-geranyl), 140.2 (3-geranyl), 169.2 (C=O); HRMS (ESI-TOF (+)) m/z [M + H]+ calculated for [C25H43N2O]+ 387.337, found 387.3369; Purity of the product determined by HPLC-MS: 95.8%.

2-((3,7-Dimethylocta-2,6-dien-1-yl)amino)-N-(2-ethyladamantan-2-yl)acetamide, 7c

Bromoacetamide 6c (680 mg, 2.26 mmol) in dry THF (15 mL) was added dropwise at 0 °C to a stirred solution of geranylamine (2) (346 mg, 2.26 mmol) and triethylamine (228 mg, 2.26 mmol) in dry THF (20 mL). The stirring continued for 48 h at room temperature. Then the aqueous phase was extracted twice with dichloromethane, the combined organic extracts were evaporated in vacuo and the crude product was purified through column chromatography using a. ether:n-hexane (1:1), b. CHCl3:MeOH (9:1), as eluents. Acetamide 7c was obtained as a pale yellow oil; yield 710 mg (84%); 1H-NMR (CDCl3, 400 MHz) δ (ppm) 0.75 (t, J = 7Hz, 3H, 2-adamantyl CH2CH3), 1.60 (s, 3H, 8-geranyl), 1.63 (s, 3H, 7-geranyl CH3), 1.68 (s, 3H, 3-geranyl CH3), 1.60–1.70 (m, 6H, 1,3,4eq,8eq,9eq,10eq-adamantyl), 1.81 (s, 2H, 6-adamantyl), 1.93–2.11 (m, 10H, 5,7,8ax,10ax-adamantyl, 2-adamanyl CH2CH3, 4,5-geranyl), 2.25 (s, 2H, 4ax,9ax-adamantyl), 3.19 (s, 2H, COCH2NH), 3.23 (d, J = 7.4 Hz, 2H, 1-geranyl), 5.07 (t, J = 7.4 Hz, 1H, 6-geranyl), 5.20 (t, J = 7.4 Hz, 1H, 2-geranyl); 13C-NMR (CDCl3, 100MHz) δ (ppm) 7.43 (2-adamantyl CH2CH3), 16.6 (3-geranyl CH3), 18.0 (8-geranyl C), 25.0 (2-adamantyl CH2CH3), 26.0 (7-geranyl CH3), 26.8 (5-geranyl C), 27.6 (5,7-adamantyl), 33.2 (4,9-adamantyl), 33.1 (1,3-adamantyl), 33.7 (8,10-adamantyl), 39.0 (6-adamantyl), 40.0 (4-geranyl), 47.7 (1-geranyl), 52.7 (COCH2NH), 60.4 (2-adamantyl), 122.2 (2-geranyl), 123.6 (6-geranyl), 132.1 (7-geranyl), 139.3 (3-geranyl), 170.3 (C=O); HRMS (ESI-TOF (+)) m/z [M + H]+ calculated for [C24H41N2O]+ 373.3213, found 373.3213; Purity of the product determined by HPLC-MS: 99.2%.

N-(3,7-dimethylocta-2,6-dien-1-yl)-N′-(2-ethyladamantan-2-yl)ethane-1,2-diamine, 8c

Acetamide 7c (420 mg, 1.13 mmol) in dry dichloromethane (5 mL) was stirred at 0–5 °C for 15 min under argon atmosphere. Recently distilled trimethylsilyl chloride (147 μL, 1.35 mmol) was then added at the same temperature and the mixture was stirred for another 15 min. A suspension of LiAlH4 (60 mg, 1.58 mmol) in a small quantity of THF was added at −10–0°C and the stirring continued for 2.5 h at the same temperature. The mixture was then treated with NaOH 10%, the resulting inorganic precipitate was filtered off, the organic phase was separated and the aqueous phase was extracted twice with dichloromethane. The combined organic extracts were evaporated in vacuo and the crude product was dissolved in dichloromethane and washed with brine. After evaporation of the solvent, the crude product was purified through column chromatography using a gradient of CHCl3:MeOH (20:1, 18:1), as system solvents, to afford diamine 8c as a pale yellow oil; yield 150 mg (37%); 1H-NMR (CDCl3, 400 MHz) δ (ppm) 0.75 (t, J = 7Hz, 3H, 2-adamantyl CH2CH3), 1.48 (d, J = 12Hz, 2H, 4eq,9eq-adamantyl), 1.59 (s, 3H, 8-geranyl), 1.63 (s, 3H, 7-geranyl CH3), 1.67 (s, 3H, 3-geranyl CH3), 1.59–1.67 (m, 4H, 1,3,8eq,10eq-adamantyl), 1.80 (s, 2H, 6-adamantyl), 1.90 (d, J = 12 Hz, 2H, 5,7-adamantyl), 1.99–2.18 (m, 10H, 4ax,8ax,9ax,10ax-adamantyl, 2-adamantyl CH2CH3, 4,5-H), 2.54 (t, J = 6Hz, 2H, NHCH2CH2NH-geranyl), 2.74 (t, J = 6 Hz, 2H, NHCH2CH2NH-geranyl), 3.26 (d, J = 7.0 Hz, 2H, 1-geranyl), 5.08 (t, J = 7 Hz, 1H, 6-geranyl), 5.26 (t, J = 7 Hz, 1H, 2-geranyl); 13C NMR (CDCl3, 100MHz) δ (ppm) 6.6 (2-adamantyl CH2CH3), 16.6 (3-geranyl CH3), 18.1 (8-geranyl), 24.0 (2-adamantyl CH2CH3), 26.0 (7-geranyl CH3), 26.8 (5-geranyl), 28.1 (5,7-adamantyl), 32.9 (4,9-adamantyl), 33.9 (1,3,8,10-adamantyl), 39.4 (6-adamantyl), 40.0 (1,4-geranyl), 47.2 (NHCH2CH2NH-geranyl), 49.9 (NHCH2CH2NH-geranyl), 57.7 (2-adamantyl), 122.7 (2-geranyl), 124.4 (6-geranyl), 131.9 (7-geranyl), 138.5 (3-geranyl); HRMS (ESI-TOF (+)) m/z [M + H]+ calculated for [C24H43N2]+ 359.3421, found 359.342; Purity of the product determined by HPLC-MS: 95.9%.

2-((3,7-Dimethylocta-2,6-dien-1-yl)amino)-N-(2-propyladamantan-2-yl)acetamide, 7d

Bromoacetamide 6d (850 mg, 2.70 mmol) in dry THF (15 mL) was added dropwise at 0 °C to a stirred solution of geranylamine (2) (413 mg, 2.70 mmol) and triethylamine (273 mg, 2.70 mmol) in dry THF (25 mL). The stirring continued for 48 h at room temperature. Then the aqueous phase was extracted twice with dichloromethane, the combined organic extracts were evaporated in vacuo and the crude product was purified through column chromatography using a. ether:n-hexane (1:1), b. CHCl3:MeOH (9:1), as eluents. Acetamide 7d was obtained as a pale yellow oil; yield 750 mg (72%); 1H-NMR (CDCl3, 400 MHz) δ (ppm) 0.89 (t, J = 7.4 Hz, 3H, 2-adamantyl CH2CH2CH3), 1.12–1.25 (m, 2H, 2-adamantyl CH2CH2CH3), 1.58–1.71 (m, 21H, 1,3,4eq,8eq,9eq,10eq-adamantyl, 8-geranyl, 3,7-geranyl CH3, 2-adamantyl CH2CH2CH3), 1.81 (s, 2H, 6-adamantyl), 1.96–2.05 (m, 8H, 5,7,8ax,10ax-adamantyl, 4,5-geranyl), 2.24 (d, J = 12 Hz, 2H, 4ax,9ax-adamantyl) 3.19 (d, J = 7.4 Hz, 2H, 1-geranyl) 3.30–3.31 (m, 2H, COCH2NH), 5.07 (m, 1H, 6-geranyl), 5.24 (m, 1H, 2-geranyl); 13C-NMR (CDCl3, 100MHz) δ (ppm) 14.9 (2-adamantyl CH2CH2CH3), 15.0 (2-adamantyl CH2CH2CH3), 16.4 (3-geranyl CH3), 18.0 (8-geranyl), 26.0 (7-geranyl CH3), 26.8 (5-geranyl), 27.6 (5,7-adamantyl), 33.3 (4,9-adamantyl), 33.5 (8,10-adamantyl), 33.7 (1,3-adamantyl), 33.9 (2-adamantyl CH2CH2CH3), 35.4 (6-adamantyl), 39.0 (4-geranyl), 40.0 (1-geranyl), 47.5 (COCH2NH), 52.0 (2-adamantyl), 119.7 (2-geranyl), 124.2 (6-geranyl), 132.1 (7-geranyl), 140.1 (3-geranyl), 168.7 (C=O); HRMS (ESI-TOF (+)) m/z [M + H]+ calculated for [C25H43N2O]+ 387.337, found 387.337.

N-(3,7-dimethylocta-2,6-dien-1-yl)-N´-(2-propyladamantan-2-yl)ethane-1,2-diamine, 8d

Acetamide 7d (1.22 g, 3.16 mmol) in dry dichloromethane (14 mL) was stirred at 0–5 °C for 15 min under argon atmosphere. Recently distilled trimethylsilyl chloride (412 μL, 3.79 mmol) was then added at the same temperature and the mixture was stirred for another 15 min. A suspension of LiAlH4 (168 mg, 4.42 mmol) in a small quantity of THF was added at −10–0°C and the stirring continued for 2.5 h at the same temperature. The mixture was then treated with NaOH 10%, the resulting inorganic precipitate was filtered off, the organic phase was separated and the aqueous phase was extracted twice with dichloromethane. The combined organic extracts were evaporated in vacuo and the crude product was dissolved in dichloromethane and washed with brine. After the evaporation of the solvent, the mixture was purified through column chromatography using a. CHCl3:MeOH (9:1), b. CHCl3:MeOH:ΝΗ3 (88:10:2), as system solvents to afford diamine 8d as a pale yellow oil; yield 390 mg (33%); 1H-NMR (CDCl3, 400 MHz) δ (ppm) 0.90 (t, J = 7.4 Hz, 3H, 2-adamantyl CH2CH2CH3), 1.15–1.25 (m, 2H, 2-adamantyl CH2CH2CH3), 1.45 (d, J = 12 Hz, 2H, 4eq,9eq-adamantyl), 1.55–1.72 (m, 17H, 1,3,6,8eq,10eq-adamantyl, 8-geranyl, 3,7-geranyl CH3, 2-adamantyl CH2CH2CH3), 1.79 (d, J = 12 Hz, 2Η, 5,7-adamantyl), 1.92 (d, J = 11.4 Hz, 2H, 8ax,10ax-adamantyl), 1.90–2.02 (m, 2H, 5-geranyl), 2.06–2.11 (m, 2H, 4-geranyl), 2.15 (d, J = 12.5 Hz, 4ax,9ax-adamantyl), 2.52 (t, J = 6Hz, 2H, NHCH2CH2NH-geranyl), 2.69 (t, J = 6 Hz, 2H, NHCH2CH2NH-geranyl), 3.23 (d, J = 7.0 Hz, 2H, 1-geranyl), 5.08 (t, J = 7 Hz, 1H, 6-geranyl), 5.25 (t, J = 7 Hz, 1H, 2-geranyl); 13C NMR (CDCl3, 100MHz) δ (ppm) 15.2 (2-adamantyl CH2CH2CH3), 15.3 (2-adamantyl CH2CH2CH3), 16.6 (3-geranyl CH3), 18.0 (8-geranyl), 26.0 (7-geranyl CH3), 26.9 (5-geranyl C), 28.1 (5-adamantyl), 28.3 (7-adamantyl), 33.0 (4,9-adamantyl), 34.0 (8,10-adamantyl), 34.4 (1,3-adamantyl), 34.6 (2-adamantyl CH2CH2CH3), 39.5 (6-adamantyl), 39.7 (4-geranyl), 40.0 (1-geranyl), 47.5 (NHCH2CH2NH-geranyl), 50.5 (NHCH2CH2NH-geranyl), 57.5 (2-adamantyl), 123.3 (2-geranyl), 124.5 (6-geranyl), 131.8 (7-geranyl), 137.9 (3-geranyl); HRMS (ESI-TOF (+)) m/z [M + H]+ calculated for [C25H45N2]+ 373.3577, found 373.3575; Purity of the product determined by HPLC-MS: 100.0%.

N-(3,7-dimethylocta-2,6-dien-1-yl)-2-((2-propyladamantan-2-yl)amino)acetamide, 14d

Acetamide 13 (184 mg, 0.67 mmol) in dry THF (6 mL) was added dropwise at 0 °C to a stirred solution of 2-propyl-2-adamantanamine (5d) (130 mg, 0.67 mmol) and triethylamine (68 mg, 0.67 mmol) in dry THF (8 mL). The stirring continued for 48 h at room temperature. Then the aqueous phase was extracted twice with dichloromethane, the combined organic extracts were evaporated in vacuo and the crude product was purified through column chromatography using a. ether:n-hexane (1:1), b. CHCl3:MeOH (9:1), as eluents. Acetamide 14d was obtained as a pale yellow oil; yield 90 mg (35%); 1H-NMR (CDCl3, 400 MHz) δ (ppm) 0.90 (t, J = 7.4 Hz, 3H, 2-adamantyl CH2CH2CH3), 1.14–1.20 (m, 2H, 2-adamantyl CH2CH2CH3), 1.51–1.68 (m, 21Η, 1,3,4,6,8eq,9,10eq-adamantyl, 8-geranyl, 3,7-geranyl CH3, 2-adamantyl CH2CH2CH3), 1.83 (s, 2H, 5,7-adamantyl), 1.90–1.93 (m, 2H, 4ax,9ax-adamantyl), 2.01–2.09 (m, 4H, 4,5-geranyl), 3.12 (s, 2H, NHCH2CO), 3.87 (t, J = 6 Hz, 2H, 1-geranyl), 5.08 (t, J = 7 Hz, 1H, 6-geranyl), 5.20 (t, J = 7 Hz, 1H, 2-geranyl); 13C-NMR (CDCl3, 100MHz) δ (ppm) 15.0 (2-adamantyl CH2CH2CH3), 15.5 (2-adamantyl CH2CH2CH3), 16.6 (3-geranyl CH3), 18.0 (8-geranyl), 26.0 (7-geranyl CH3), 26.8 (5-geranyl), 28.0 (5,7-adamantyl), 33.2 (4,9-adamantyl), 33.8 (8,10-adamantyl), 34.4 (1,3-adamantyl), 35.2 (2-adamantyl CH2CH2CH3), 37.2 (6-adamantyl), 39.3 (4-geranyl), 39.8 (1-geranyl), 44.2 (NHCH2CO), 120.4 (2-geranyl), 124.2 (6-geranyl), 132.1 (7-geranyl), 140.1 (3-geranyl), 168.8 (C=O); HRMS (ESI-TOF (+)) m/z [M + H]+ calculated for [C25H43N2O]+ 387.337, found 387.3369; Purity of the product determined by HPLC-MS: 98.3%.

2-((3,7-Dimethylocta-2,6-dien-1-yl)amino)-N-(2-butyladamantan-2-yl)acetamide, 7e

Bromoacetamide 6e (190 mg, 0.58 mmol) in dry THF (4 mL) was added dropwise at 0 °C to a stirred solution of geranylamine (2) (89 mg, 0.58 mmol) and triethylamine (58 mg, 0.58 mmol) in dry THF (5 mL). The stirring continued for 72 h at room temperature. Then the aqueous phase was extracted twice with dichloromethane, the combined organic extracts were evaporated in vacuo and the crude product was purified through column chromatography using a. ether:n-hexane (1:1), b. CHCl3:MeOH (9:1), as eluents. Acetamide 7e was obtained as a pale yellow oil; yield 160 mg (69%); 1H-NMR (CDCl3, 400 MHz) δ (ppm) 0.73–0.77 (m, 3H, 2-adamantyl (CH2)3CH3), 1.08–1.34 (m, 4H, 2-adamantyl CH2(CH2)2CH3), 1.60 (s, 3H, 8-geranyl), 1.63 (s, 3H, 7-geranyl CH3), 1.68 (s, 3H, 3-geranyl CH3), 1.59–1.71 (m, 6H, 1,3,4eq,8eq,9eq,10eq-adamantyl), 1.82 (s, 2H, 6-adamantyl), 1.89–2.08 (m, 10H, 5,7,8ax,10ax-adamantyl, 2-adamantyl CH2(CH2)2CH3, 4,5-geranyl), 2.24 (d, J = 12.5 Hz, 2H, 4ax,9ax-adamantyl), 3.20 (d, J = 7.4 Hz, 2H, 1-geranyl), 3.30 (s, 2H, COCH2NH), 5.07 (t, J = 7.4 Hz, 1H, 6-geranyl), 5.24 (t, J = 7.4 Hz, 1H, 2-geranyl). Fumarate salt; 13C-NMR (MeOD, 100MHz,) δ (ppm) 14.5 (2-adamantyl (CH2)3CH3), 15.6 (3-geranyl CH3), 16.8 (8-geranyl), 18.0 (7-geranyl CH3), 23.5 (4,9-adamantyl), 25.4 (5-geranyl), 26.0 (2-adamantyl (CH2)2CH2CH3), 26.8 (2-adamantyl CH2CH2CH2CH3), 27.6 (5,7-adamantyl), 32.7 (2-adamantyl CH2(CH2)2CH3), 33.3 (8,10-adamantyl), 33.7 (1,3-adamantyl), 39.0 (6-adamantyl), 40.0 (4-geranyl), 47.3 (1-geranyl), 60.8 (COCH2NH), 66.2 (2-adamantyl), 119.8 (2-geranyl), 124.1 (6-geranyl), 132.2 (3,7-geranyl), 168.7 (C=O); HRMS (ESI-TOF (+)) m/z [M + H]+ calculated for [C26H45N2O]+ 401.3526, found 401.3527; Purity of the product determined by HPLC-MS: 98.6%.

N-(3,7-dimethylocta-2,6-dien-1-yl)-N´-(2-butyladamantan-2-yl)ethane-1,2-diamine, 8e

Acetamide 7e (160 mg, 0.40 mmol) in dry dichloromethane (2 mL) was stirred at 0–5 °C for 15 min under argon atmosphere. Recently distilled trimethylsilyl chloride (52 μL, 0.48 mmol) was then added at the same temperature and the mixture was stirred for another 15 min. A suspension of LiAlH4 (21 mg, 0.56 mmol) in a small quantity of THF was added at −10–0°C and the stirring continued for 2.5 h at the same temperature. The mixture was then treated with NaOH 10%, the resulting inorganic precipitate was filtered off, the organic phase was separated and the aqueous phase was extracted twice with dichloromethane. The combined organic extracts were evaporated in vacuo and the crude product was dissolved in dichloromethane and washed with brine. After the evaporation of the solvent, the crude product was purified through column chromatography using ether:n-hexane (1:1) and a gradient of CHCl3:MeOH (25:1, 20:1), as system solvents to afford diamine 8e as a pale yellow oil; yield 20 mg (13%). Fumarate salt; 1H-NMR (MeOD, 400 MHz) δ (ppm) 0.91 (t, J = 7Hz, 3H, 2-adamantyl (CH2)3CH3), 1.12–1.33 (m, 4H, 2-adamantyl CH2(CH2)2CH3), 1.49 (d, J = 12Hz, 2H, 4eq,9eq-adamantyl), 1.59 (s, 3H, 8-geranyl), 1.64 (s, 3H, 7-geranyl CH3), 1.67 (s, 3H, 3-geranyl CH3), 1.59–1.69 (m, 8H, 1,3,6,8eq,10eq-adamantyl, 2-adamantyl-CH2(CH2)2CH3), 1.81 (s, 2H, 5,7-adamantyl), 1.92 (d, J = 12Hz, 2H, 8ax,10ax-adamantyl), 1.99–2.11 (m, 4H, 4,5-geranyl), 2.16 (d, J =12Hz, 2H, 4ax,9ax-adamantyl), 2.59 (t, J = 6Hz, 2H, NHCH2CH2NH-geranyl), 2.79 (t, J = 6 Hz, 2H, NHCH2CH2NH-geranyl), 3.29 (d, J = 7.0 Hz, 2H, 1-geranyl), 5.08 (t, J = 7 Hz, 1H, 6-geranyl), 5.26 (t, J = 7 Hz, 1H, 2-geranyl); 13C NMR (MeOD, 100MHz) δ (ppm) 15.4 (2-adamantyl (CH2)3CH3), 17.5 (3-geranyl CH3), 18.7 (8-geranyl), 19.7 (7-geranyl CH3), 23.4 (5-geranyl), 25.2 (4-adamantyl), 25.7 (9-adamantyl), 26.7 (2-adamantyl (CH2)2CH2CH3), 28.1 (2-adamantyl CH2CH2CH2CH3), 29.8 (5,7-adamantyl), 33.1 (2-adamantyl CH2(CH2)2CH3), 34.1 (8-adamantyl), 35.4 (10-adamantyl), 35.7 (1,3-adamantyl), 38.9 (6-adamantyl), 40.8 (4-geranyl), 41.6 (1-geranyl), 47.3 (NHCH2CH2NH-geranyl), 48.2 (NHCH2CH2NH-geranyl), 62.1 (2-adamantyl), 117.2 (2-geranyl), 125.6 (6-geranyl), 136.7 (3,7-geranyl); HRMS (ESI-TOF (+)) m/z [M + H]+ calculated for [C26H47N2]+ 387.3734, found 387.3737; Purity of the product determined by HPLC-MS: 98.2%.

2-((3,7-Dimethylocta-2,6-dien-1-yl)amino)-N-(2-hexyladamantan-2-yl)acetamide, 7f

Bromoacetamide 6f (70 mg, 0.20 mmol) in dry THF (1.5 mL) was added dropwise at 0 °C to a stirred solution of geranylamine (2) (31 mg, 0.20 mmol) and triethylamine (20 mg, 0.20 mmol) in dry THF (2 mL). The stirring continued for 72 h at room temperature. Then the aqueous phase was extracted twice with dichloromethane, the combined organic extracts were evaporated in vacuo and the crude product was purified through column chromatography using a. ether:n-hexane (1:1), b. CHCl3:MeOH (9:1), as eluents. Acetamide 7f was obtained as a yellow oil; yield 50 mg (60%); 1H-NMR (CDCl3, 400 MHz) δ (ppm) 0.88 (t, J = 7Hz, 3H, 2-adamantyl (CH2)5CH3), 1.11–1.33 (m, 8H, 2-adamantyl CH2(CH2)4CH3), 1.51–1.68 (m, 19H, 1,3,4eq,6,8eq,9eq,10eq-adamantyl, 3-geranyl CH3, 7-geranyl CH3, 8-H, 2-adamantyl CH2(CH2)4CH3), 1.82–1.83 (m, 2H, 5,7-adamantyl), 1.91 (d, J = 8.5 Hz, 2H, 8ax,10ax-adamantyl), 2.01–2.10 (m, 6H, 4ax,9ax-adamantyl, 4,5-geranyl), 3.11 (s, 2H, COCH2NH), 3.88 (t, J = 4 Hz, 2H, 1-geranyl), 5.08 (t, J = 7.4 Hz, 1H, 6-geranyl), 5.21 (t, J = 7.4 Hz, 1H, 2-geranyl); 13C-NMR (CDCl3, 100MHz) δ (ppm) 15.6 (2-adamantyl (CH2)5CH3), 16.6 (3-geranyl CH3), 18.0 (8-geranyl), 22.2 (2-adamantyl (CH2)4CH2CH3), 23.0 (2-adamantyl (CH2)3CH2CH2CH3), 26.0 (7-geranyl CH3), 26.8 (5-geranyl), 28.0 (5,7-adamantyl), 30.3 (2-adamantyl CH2)2CH2(CH2)2CH3), 32.4 (2-adamantyl CH2CH2(CH2)3CH3), 32.7 (2-adamantyl CH2(CH2)4CH3), 33.3 (4,9-adamantyl), 33.9 (8,10-adamantyl), 34.4 (1,3-adamantyl), 37.2 (6-adamantyl), 39.3 (4-geranyl), 39.8 (1-geranyl), 58.0 (COCH2NH), 66.2 (2-adamantyl), 120.5 (2-geranyl), 124.2 (6-geranyl), 132.1 (7-geranyl), 140.1 (3-geranyl), 172.8 (C=O).

N-(3,7-dimethylocta-2,6-dien-1-yl)-N´-(2-hexyladamantan-2-yl)ethane-1,2-diamine, 8f

Acetamide 7f (50 mg, 0.12 mmol) in dry dichloromethane (1 mL) was stirred at 0–5 °C for 15 min under argon atmosphere. Recently distilled trimethylsilyl chloride (15 μL, 0.14 mmol) was then added at the same temperature and the mixture was stirred for another 15 min. A suspension of LiAlH4 (7 mg, 0.17 mmol) in a small quantity of THF was added at −10–0 °C and the stirring continued for 2.5 h at the same temperature. The mixture was then treated with NaOH 10%, the resulting inorganic precipitate was filtered off, the organic phase was separated and the aqueous phase was extracted twice with dichloromethane. The combined organic extracts were evaporated in vacuo and the crude was dissolved in dichloromethane and washed with brine. After the evaporation of the solvent, the crude product was purified through column chromatography using ether:n-hexane (1:1) and CHCl3:MeOH (30:1), as system solvents to afford diamine 8f as a yellow oil; yield 20 mg (40%); 1H-NMR (CDCl3, 400 MHz) δ (ppm) 0.87 (t, J = 7Hz, 3H, 2-adamantyl (CH2)5CH3), 1.18–1.27 (m, 8H, 2-adamantyl CH2(CH2)4CH3), 1.49 (d, J = 12Hz, 2H, 4eq,9eq-adamantyl), 1.59 (s, 3H, 8-geranyl), 1.64 (s, 3H, 7-geranyl CH3), 1.66 (s, 3H, 3-geranyl CH3), 1.59–1.69 (m, 8H, 1,3,6,8eq,10eq-adamantyl, 2-adamantyl CH2(CH2)4CH3), 1.81 (s, 2H, 5,7-adamantyl), 1.91 (d, J = 8.5 Hz, 2H, 8ax,10ax-adamantyl), 1.99–2.10 (m, 4H, 4,5-geranyl), 2.16 (d, J = 8.5 Hz, 2H, 4ax,9ax-adamantyl), 2.58 (t, J = 6Hz, 2H, NHCH2CH2NH-geranyl), 2.78 (t, J = 6 Hz, 2H, NHCH2CH2NH-geranyl), 3.29 (d, J = 7.0 Hz, 2H, 1-geranyl), 5.07 (t, J = 7 Hz, 1H, 6-geranyl), 5.25 (t, J = 7 Hz, 1H, 2-geranyl); 13C NMR (CDCl3, 100MHz) δ (ppm) 14.4 (2-adamantyl (CH2)5CH3), 16.7 (3-geranyl CH3), 18.0 (8-geranyl), 22.0 (2-adamantyl (CH2)4CH2CH3), 23.1 (2-adamantyl (CH2)3CH2CH2CH3), 26.0 (7-geranyl CH3), 26.8 (5-geranyl), 27.9 (5,7-adamantyl), 30.4 (2-adamantyl CH2)2CH2(CH2)2CH3, 32.0 (2-adamantyl CH2CH2(CH2)3CH3), 32.3 (2-adamantyl CH2(CH2)4CH3), 32.9 (4,9-adamantyl), 33.9 (8,10-adamantyl), 34.2 (1,3-adamantyl), 39.1 (6-adamantyl), 39.3 (4-geranyl), 40.0 (1-geranyl), 46.9 (NHCH2CH2NH-geranyl), 49.2 (NHCH2CH2NH-geranyl), 66.2 (2-adamantyl), 121.9 (2-geranyl), 124.3 (6-geranyl), 131.9 (7-geranyl), 139.2 (3-geranyl); HRMS (ESI-TOF (+)) m/z [M + H]+ calculated for [C28H51N2]+ 415.4047, found 415.404; Purity of the product determined by HPLC-MS: 100.0%.

2-((3,7-Dimethylocta-2,6-dien-1-yl)amino)-N-(2-benzyladamantan-2-yl)acetamide, 7g

Bromoacetamide 6g (530 mg, 1.46 mmol) in dry THF (8 mL) was added dropwise at 0 °C to a stirred solution of geranylamine (2) (223 mg, 1.46 mmol) and triethylamine (147 mg, 1.46 mmol) in dry THF (12.5 mL). The stirring continued for 48 h at room temperature. Then the aqueous phase was extracted twice with dichloromethane, the combined organic extracts were evaporated in vacuo and the crude product was purified through column chromatography using a. ether:n-hexane (1:1), b. CHCl3:MeOH (9:1), as eluents. Acetamide 7g was obtained as a pale yellow oil; yield 560 mg (88%); 1H-NMR (CDCl3, 400 MHz) δ (ppm) 1.57 (s, 3H, 8-geranyl), 1.59 (s, 3H, 7-geranyl CH3), 1.67 (s, H, 3-geranyl CH3), 1.57–1.84 (m, 9H, 1,3,4eq,5,6eq,7,8eq,9eq,10eq-adamantyl), 1.90 (s, 1H, 6ax-adamantyl), 1.98–2.08 (m, 4H, 4,5-geranyl), 2.24–2.30 (m, 4H, 4ax,8ax,9ax,10ax-adamantyl), 3.14 (d, J = 7.4 Hz, 2H, 1-geranyl), 3.25 (s, 2H, COCH2NH), 3.38 (s, 2H, benzyl), 5.07 (t, J = 7.4 Hz, 1H, 6-geranyl), 5.26 (t, J = 7.4 Hz, 1H, 2-geranyl), 7.06–7.14 (m, 2H, phenyl), 7.16–7.19 (m, 1H, phenyl), 7.22–7.25 (m, 2H, phenyl); 13C-NMR (CDCl3, 100MHz) δ (ppm) 16.8 (3-geranyl CH3), 18.0 (8-geranyl), 26.0 (7-geranyl CH3), 26.7 (5-geranyl), 27.3 (5-adamantyl), 27.8 (7-adamantyl), 33.5 (4,8,9,10-adamantyl), 33.6 (1,3-adamantyl), 38.1 (benzyl), 38.9 (6-adamantyl), 39.9 (4-geranyl), 47.1 (1-geranyl), 56.7 (COCH2NH), 62.0 (2-adamantyl), 123.9 (6-geranyl), 126.5 (phenyl), 128.3 (phenyl), 130.6 (phenyl), 138.5 (quaternary-phenyl), 163.6 (C=O); HRMS (ESI-TOF (+)) m/z [M + H]+ calculated for [C29H43N2O]+ 435.337, found 435.3371; Purity of the product determined by HPLC-MS: 97.8%.

N-(3,7-dimethylocta-2,6-dien-1-yl)-N´-(2-benzyladamantan-2-yl)ethane-1,2-diamine, 8g