Abstract

Peptide-based hydrogel biomaterials have emerged as an excellent strategy for immune system modulation. Peptide-based hydrogels are supramolecular materials that self-assemble into various nanostructures through various interactive forces (i.e., hydrogen bonding and hydrophobic interactions) and respond to microenvironmental stimuli (i.e., pH, temperature). While they have been reported in numerous biomedical applications, they have recently been deemed as promising candidates to improve the efficacy of cancer immunotherapies and treatments. Immunotherapies seek to harness the body’s immune system to preemptively protect against and treat various diseases, such as cancer. However, their low efficacy rates result in limited patient responses to treatment. Here, the immunomaterial’s potential to improve these efficacy rates by either functioning as immune stimulators through direct immune system interactions and/or delivering a range of immune agents is highlighted. The chemical and physical properties of these peptide-based materials that lead to immune-modulation and how one may design a system to achieve desired immune responses in a controllable manner are discussed. Works in the literature that reports peptide hydrogels as adjuvant systems and for the delivery of immunotherapies are highlighted. Finally, the future trends and possible developments based on peptide hydrogels for cancer immunotherapy applications are discussed.

Keywords: Immunomaterials, peptide hydrogels, biomaterials, cancer immunotherapy, supramolecular assembly, adjuvants, vaccine

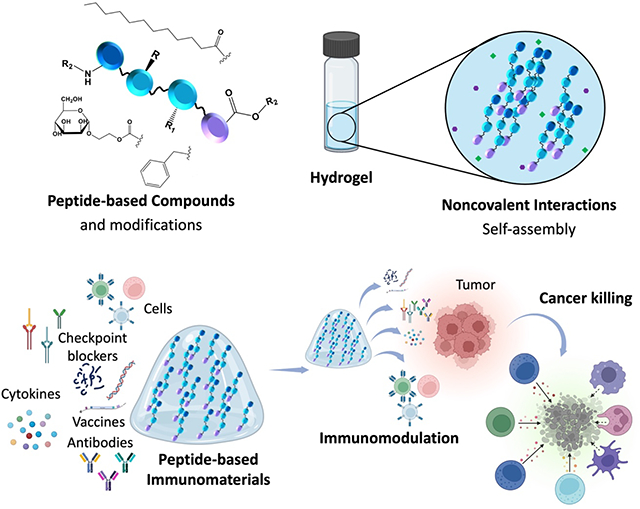

Graphical Abstract

Peptide-based hydrogels are self-assembling, stimuli-responsive biomaterials that have emerged as immune-modulating materials for cancer therapies. Immune-modulation is achieved through direct interactions of the biomaterials with immune cells and through their nanostructures influencing entrapment and controlled release of bioactive molecules. This review highlights peptide hydrogels as immunomaterials for cancer applications by demonstrating adjuvant properties or through the delivery of cancer immunotherapies.

1. Introduction

Immunomaterials are a class of biomaterials designed to modulate the function of the innate and adaptive immune cells (i.e., macrophages, dendritic cells, natural killer (NK) cells, B cells, and T cells) and pathways. Thus, this paves the way for developing new strategies for treating auto-immune diseases, chronic inflammation, foreign body response to medical devices, and cancer, which will be the focus of this review. The immune system is a collection of cellular and molecular response mechanisms that protect the body from foreign antigens that provoke an immune response, such as microbes, cellular debris/damaged cells, cancer cells, toxins, and viruses. The immune system is divided into the innate and adaptive immune systems. Innate immunity is the body’s initial response and refers to a nonspecific defense mechanism that comes to play immediately or within hours of an intrusion of an antigen in the body. Adaptive immunity refers to antigen-specific immunity, which first generates specific immune cells to attack the antigen at the first exposure and then keep the memory of the antigen for subsequent exposures.

While a lack of an immune response from a biomaterial (bioinertness) was vigorously sought in early research, recently, the modulation of a host response to a biomaterial is being acknowledged, allowing one to obtain a desired immune system response.1 Therefore, using biomaterials as a new approach to manipulate the immune response toward a desired outcome is gaining traction. Immune-modulating materials direct host responses for synergistic and enhanced remodeling of a target tissue without scar formation, with immune-modulation often targeting neutrophils or antigen-presenting cells (APCs). Biomaterials can achieve immune-modulation by immune cells’ phenotype, polarization, or antigen-presenting efficiency through their design elements, such as composition, surface topography, surface chemistry, shape, and size, or by delivering immunomodulatory agents to relevant sites. For example, there is a significant body of literature on using immune instructive materials for improved outcomes in tissue engineering applications.2,3,4 This includes poly(dioxanone) microfibers used as topographical cues for peripheral nerve regeneration by promoting the recruitment and polarization of macrophages, subsequently enhancing axon elongation and myelination.5 In addition, superparamagnetic scaffolds have also induced M2 polarization in macrophages, inhibiting pro-inflammatory cytokine secretion and promoting osteoclast differentiation for bone tissue engineering.6

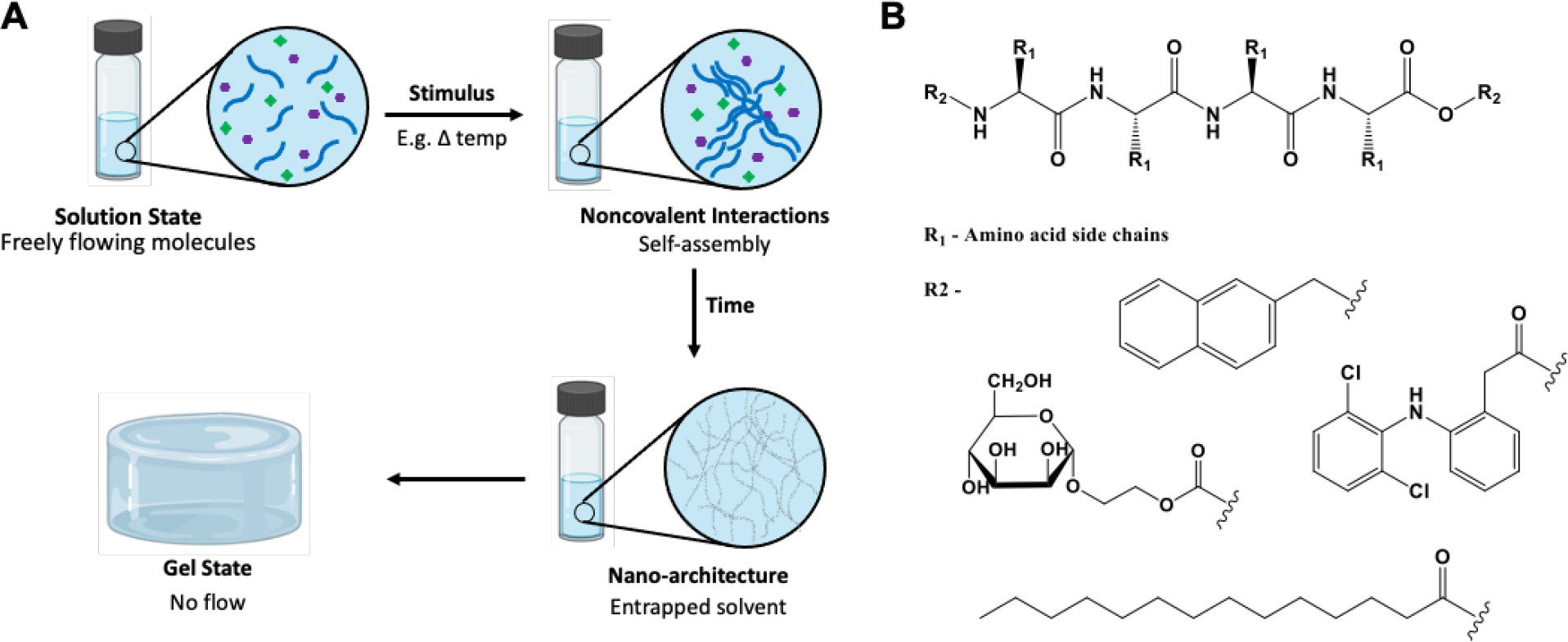

Although biomaterials composed of chemical polymers such as alginate, hyaluronic acid, bioactive glasses, etc., were designed to target immune cells/pathways, recently, physical hydrogel systems such as peptide hydrogels (semi-solid materials made of a liquid solvent and a solid gelator) have gained popularity within the immunomaterials field due to their stimuli-responsive nature, ability to self-assemble, tunable physical and mechanical properties, injectability, biocompatibility, and biodegradability.7,8 These gels are typically formed through non-covalent interactions, including hydrogen bonding, π–π stacking, electrostatic, van der Waals, and hydrophobic interactions.9 (Figure 1A) Peptide hydrogels can also undergo sol-gel phase transitions in response to pH, temperature, solvent, light, sonication, and other environmental stimuli, which allows these materials to be tunable for specific applications. Short self-assembling peptides capable of hydrogel formation are also easily modifiable. The amino acid sequence can be specifically designed, and various compounds can be covalently conjugated, allowing various functionalities such as receptor targeting and immune cell recruitment (Figure 1B). Thus, many peptide conjugates capable of forming hydrogels have been reported in the literature for various applications, including tissue engineering, drug delivery, regenerative medicine, wound healing, and 3D printing.7,9–13 More recently, they have been explored as immune-modulating materials in increasing the immune efficacy of various cancer immunotherapies.14–17

Figure 1:

A. Schematic representation of physical peptide hydrogels formed through non-covalent interactions and external stimuli. B. Backbone of a peptide conjugate that can be synthesized using various amino acids (R1) and functionalized for different applications or targeting different pathways through different functional groups, some chemical moieties that can be added is shown by R2; other options can be used.

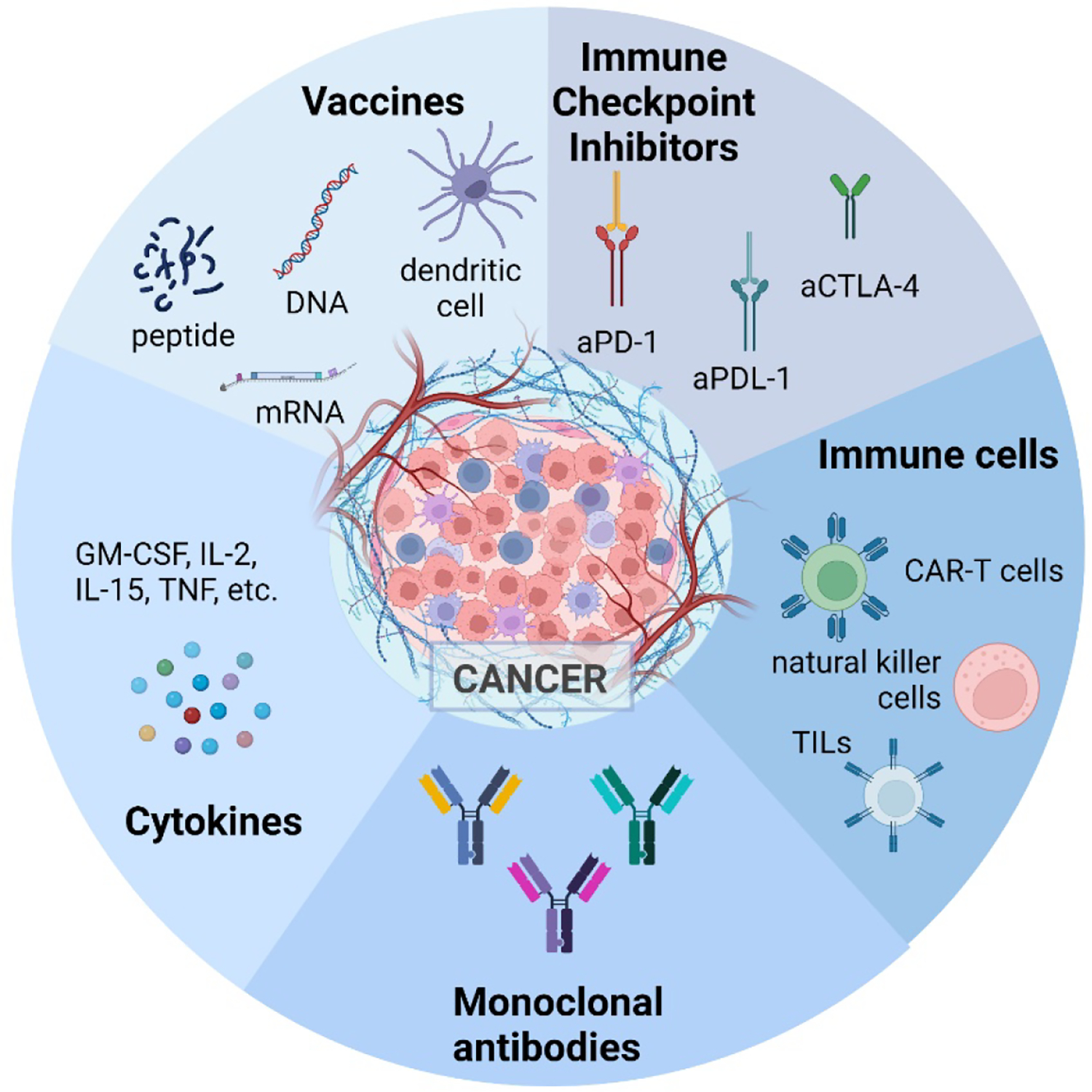

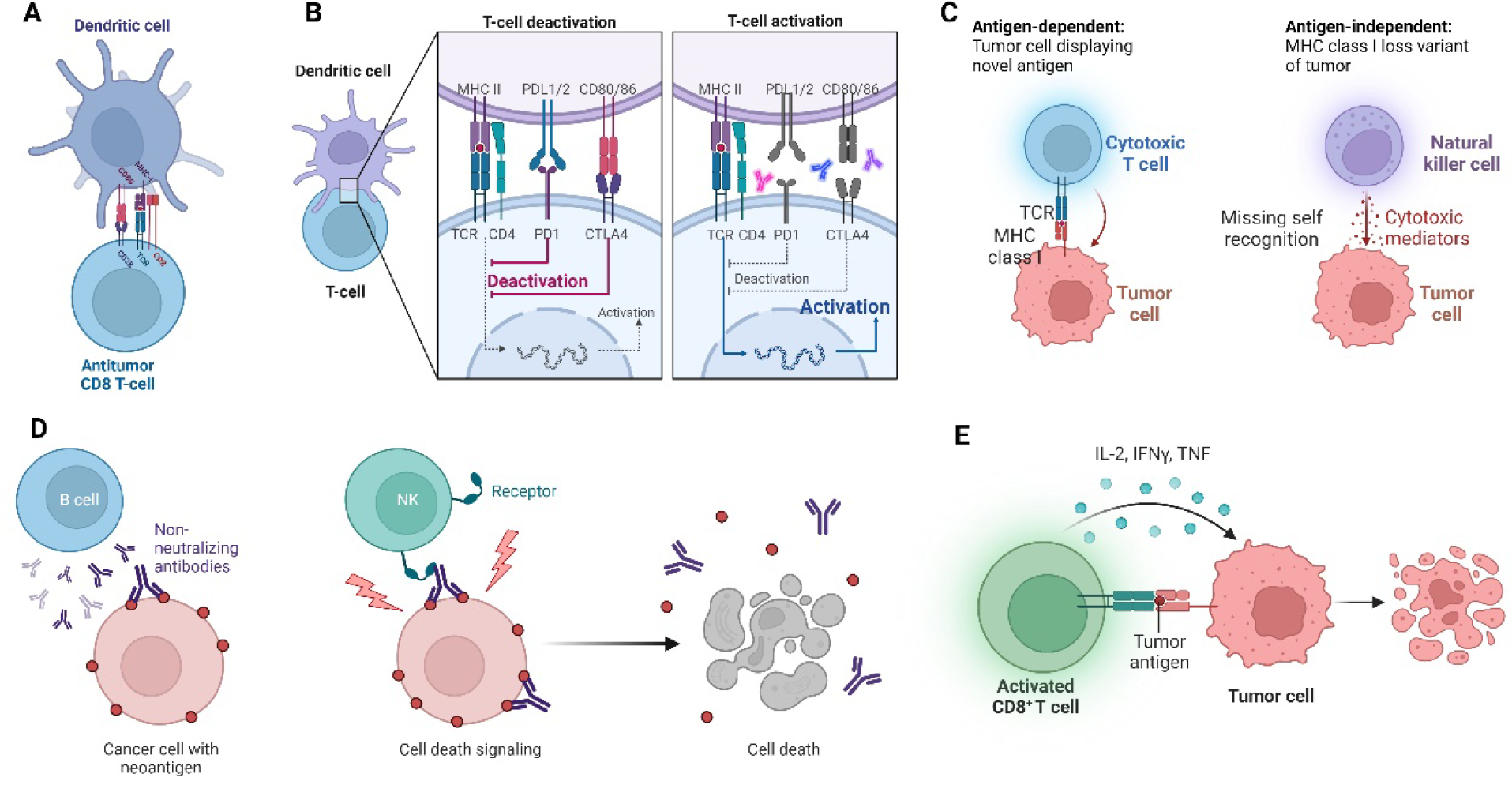

Cancer immunotherapy is a novel, attractive approach for cancer treatment with fewer side effects than standard procedures, such as surgical resection and chemotherapy, showing limited efficacy leading to tumor relapse and metastasis. There are five main types of cancer immunotherapies: vaccines, adoptive cell therapy, immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICI), monoclonal antibodies, and cytokines.16,18,19 (Figure 2) Vaccines typically stimulate anti-tumor immunity by using tumor-associated antigens (TAAs), which are overexpressed on cancer cells.20,21 There are four categories of vaccines: peptide, whole cell, viral-based, and nucleic acid-based. 20,22–24 These either encode or act as the TAAs themselves or are involved in the uptake and presentation of the TAAs. Monoclonal antibodies target and interact with a specific antigen, thereby directing the immune system to destroy the cells containing the antigen.25 Immune checkpoint inhibitors are a sub-class of monoclonal antibodies specifically targeting immune checkpoints (PD-1, PDL-1, and CTLA-4).26 They work to interrupt these co-inhibitory signaling pathways and promote the destruction of tumor cells. The antibodies can bind to the targets on the immune cells (PD-1 and CTL-4) or the cancer cells (PDL-1). Adoptive cell therapy (ACT) is a type of immunotherapy where T cells are taken from a patient’s blood, proliferated or modified in vitro, and then returned to the patient to fight cancer.27 Chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T cell therapy is a type of ACT that recognizes and eliminates cells presenting a specific target antigen.28 Lastly, cytokines are small proteins involved in cell-to-cell communication and recruitment and serve as cell messengers for the innate and adaptive immune systems. They have been reported to increase the number of immune cells in the TME, enhancing their cytolytic activity, improving antigen priming, and increasing tumor cell recognition due to signaling.29–31 For an in-depth description of immunotherapies, it is recommended to refer to the cited reviews. 28,32–35

Figure 2:

Five classes of immunotherapies for cancer treatment. (Created with BioRender.com)

Unfortunately, only roughly 30% of patients respond to these cancer immunotherapies, and therefore there is a pressing need to improve therapy options and lower recurrence rates.36 Delivery of various immunotherapies through coatings, hydrogel systems, micro/nanoparticles, and gene delivery systems is one immunomodulation strategy. With cancer immunotherapy rapidly developing, injectable biomaterials such as peptide hydrogels can serve as an optimal delivery matrix and contribute to local immunomodulation.17 They have played a role in inhibiting tumor metastasis and recurrence as they contribute to activating anti-tumor responses safely. This review highlights the recent advances and roles of peptide hydrogels as novel immunomaterials to increase the efficacy of cancer immunotherapies. We describe peptide hydrogels, cancer immunotherapies, and the material’s role in direct immunomodulation as adjuvants or in the effective delivery of the five immunotherapies.

2. Peptide Hydrogels as Immunomaterials

2.1. Introduction to Peptide Hydrogels

Peptide-based supramolecular hydrogels, a class of biomaterials, are gaining traction due to their versatility, modifiability, tunable properties, and use in various biomedical applications.7,8,37 As mentioned, these self-assembling physical gels form through non-covalent interactions and can undergo sol-gel phase transitions in response to various stimuli. Stimuli-responsiveness is an attractive property for a hydrogel to possess. It is based on a change in peptide secondary structure, solubility, and intermolecular interactions, allowing for the materials’ mechanical properties and state tunability. For example, the assembly of the simple Fmoc-Ala-Ala dipeptide into a hydrogel is triggered by an increase in temperature, while Fmoc-Phe-Phe forms a fibrous network when the pH is lowered.38,39 pH is reported to be the simplest chemical stimuli that impact gelation as hydrogen bonding motifs as well as electrostatic interactions, are strongly influenced by acid and base. An increase or decrease in pH can cause charged amino acids such as lysine to become either protonated or deprotonated, affecting the intra- and intermolecular interactions and causing changes in folding and self-assembly. Changes in the redox state have also been reported to trigger morphological changes caused by phase transitions. Temperature is another common stimulus affecting the hydrogel state where the gels typically form by dissolving a gelator in a heated solvent and then cooling the solution, which allows for cycling between the gel and sol phases.9 Furthermore, ultrasonication is another stimulus used to prepare supramolecular materials due to speeding the dissolution or dispersion of the gelator molecules.9

The self-assembling properties of peptides are sequence-dependent and can be influenced by fine-tuning their chemical structure, e.g., choosing or substituting specific amino acids or changing their enantiomer form. The amino acid sequence plays a significant role in gelation outcomes. For example, diphenylalanine plays an important role in fiber formation via π−π stacking and has been used to investigate hierarchical structures. Charged amino acids such as aspartic and glutamic acid, arginine, and lysine have been used to temper hydrogen-bind formation and improve solubility in water. The use of alanine, tryptophan, and isoleucine have been combined due to their charged and hydrophobic properties allowing the design of co-assembling oppositely charged peptides.40 This oppositely charged system was able to assist with aqueous solubility, led to a high kinetic threshold for the aggregation, and provide a long-ranged attractive force to encourage peptides to come together. Furthermore, peptide sequences determine the ways in which polymerization pathways affect the structure and function of hydrogel systems. In one example by Stupp et al., a peptide compound that formed through hydrogen bonding generated heterogeneous morphologies with a weak porous hydrogel network, while a peptide compound that formed through side chain interactions formed uniform polymers and a denser and stiffer hydrogel network.41 The chirality of the amino acids in the peptide sequence also affects self-assembly.42,43 Homochiral L and D peptides usually have similar self-assembling behaviors but distinct biological functions, while heterochiral peptides can differ in both. D-peptides exhibited better biostability because of their resistance to endogenous proteases.44,45 Supramolecular peptide hydrogel materials are also usually shear-thinning and self-healing, which means they behave more like a viscous liquid under strain. The return to the gel state is observed upon the removal of stress. This property allows them to be injected through a standard needle or clinical catheter as a viscous liquid and then reformed as a gel post-injection as opposed to covalently crosslinked hydrogels that require in situ crosslinking or surgical implantation.46 Furthermore, these materials can form an array of morphological structures, including nanofibrous matrices, nanorods, nanotubes, and micelles. 47,48

Many peptide conjugates capable of forming hydrogels have been functionalized with bio-active molecules for drug delivery and anti-tumor applications,49–55 used to entrap cells for 3D tissue cultures and cell therapy,12,56–58 designed to exhibit antibacterial properties and support wound healing processes,50,59–64 utilized in biosensor and diagnostic platform production,65–67 and modulate processes such as cell differentiation and tissue regeneration.68–73 Biomolecules can be encapsulated within these hydrogels using electrostatic interactions and physical entrapment. This allows for slow and sustained release, thus increasing their lifetime. These self-assembling nanostructures, such as nanofibers, rods, or tubes, have also been shown to stimulate the production of tumor-related antigens and promote T cell activation through peptide epitope presentation by APCs.71,74–76 APCs initiate adaptive cellular immune responses by uptaking, processing, and presenting these antigens for recognition by T cells thus activating them and increasing cytotoxic activity. Recently, they have been explored in immunotherapy applications as immune-modulating materials where the material can affect the immune system, serve as a delivery vehicle for various immunotherapies, and affect the outcomes of treatments. However, little was known about the immuno-modulatory properties of peptide hydrogels and their use in immunotherapy until recently.

2.2. Introduction to the Immune System and Immunomaterials

The innate immune system is the first line of defense and includes neutrophils, macrophages, dendritic cells, basophils, eosinophils, and NK cells. These cells can internalize and break down foreign macromolecules, and some can phagocytose, kill, and digest whole microorganisms. In addition, the production of cytokines and chemokines by some immune cells (eosinophils, mast cells, basophils) allows for the rapid recruitment of other immune cells (neutrophils, macrophages, DCs, T cells) to the site of infection and inflammation. Macrophages can be divided into M1 and M2 phenotypes, involved in tissue damage and the inhibition of cell proliferation, and tissue repair and the promotion of cell proliferation, respectively.77 Furthermore, the cells of the innate immune system can activate the adaptive immune response as APCs (DCs and macrophages).

The adaptive immune system includes T cells, which can be activated through APCs, and B cells, which produce antibodies. On the surface of APCs are a group of proteins called the major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class I and II. These will present endogenous or exogenous peptides to T cells, respectively, where MHC-peptide complexes are recognized by the T cell receptor (TCR) on the surface of T cells. This antigen presentation process can stimulate T cells to differentiate into CD8+ cytotoxic T cells (CTL) or CD4+ helper T cells. CD8+ CTLs become activated through TCR recognition of peptides bound to MHC class I molecules. These are involved in the destruction of cells expressing the targeted antigen and can release substances that induce apoptosis of target cells. CD4+ T cells are activated by recognizing peptides bound to MHC class II molecules, are involved in regulating adaptive immunity, and help the CD8+ T cell response. These helper T cells can be divided into Th1 and Th2. Th1 cells are typically associated with inflammation and induce cell-mediated responses, while Th2 cells produce cytokines to help B cells proliferate and are associated with a humoral immune response. Unlike T cells, B cells do not need APCs to recognize antigens and are responsible for producing high-affinity antibodies. Further in-depth reviews on immunology and the immune system processes are reported.78,79

A brief overview is provided to help understand the concepts behind immunomaterial function. These types of materials can be immune-evasive, where they attenuate inflammatory immune reactions and minimize host immune responses against implanted materials, or immune-activating, where they can be designed to harness the immune responses and provide therapeutic effects. Immune-evasive material properties can be attained by controlling surface chemistry, topography, and architecture, which can be manipulated to limit immune cell adhesion and denatured protein adsorption. Furthermore, functionalizing the material with ligands, anti-inflammatory agents, or wound-healing agents can be another strategy for this type of immunomodulation. Immune-activating materials that can deliver vaccine components (and act as replacement adjuvants) and immune modulators can produce a pro-immune response. The following section will discuss peptide hydrogel biomaterials as a class of immunomaterials.

2.3. Supramolecular Peptide Biomaterials as Immunomaterials

Supramolecular peptide assemblies are stabilized by non-covalent interactions, form various nanostructures, and have the ability to interact or influence immune cell function.80 The material properties, such as the size, shape, charge, particulate nature, type of amino acids, and ability to incorporate multiple functional components, such as various epitopes from cancer antigens or chemical moieties, all affect their immuno-modulatory properties.

Firstly, the addition of certain amino acids within peptide sequences, such as cationic and hydrophobic amino acids, has been shown to be crucial for both anti-cancer and immunomodulatory activity.81 Proline has been reported to aid in proteolytic stability, while phenylalanine has hydrophobicity properties, an important biophysical parameter for immunomodulatory activity. Glutamic and aspartic acid are reported to inhibit AKT phosphorylation, which is a key signal transduction protein in cancer biology. Tyrosine and tryptophan also contribute to hydrophobicity and also possess cell-penetrating abilities, as well as help to acquire a stable conformation. The presence of positive or negative charges is one of the most important parameters to initiate electrostatic interactions to form supramolecular structures as well as interactions with various cell membranes.81,82 Studies have shown that electrostatic interactions between positively charged, cationic amino acid residues such as lysine and histidine and negatively charged components in cell membranes (antigen presenting cells and cancer cells) can initiate immunomodulatory properties.82

The number of amino acid residues in peptide sequences can range typically from 5 to 100, and this allows for many potential variations of new sequences with different properties. This size also critically influences the distribution of the material fibers or particles and encapsulated biomolecules through the lymphatic system and are picked up by APCs. The shape and surface chemistry are found to affect the transport and the immunogenicity of the material.83 The nanofiber length was also found to affect the extent of the immune response, where shortening nanofibers using extrusion decreased the ability to raise CD8+ T cell responses.84 They can identify desirable immune phenotypes by reducing the need for adjuvants. Chemical modifications such as PEGylation, or the addition of fatty acids, both at the side chains or main changes, are also reported to improve immunomodulatory properties, including facilitating the uptake of the peptides by cells, inducing inflammatory responses, or increasing their stability.82

Depending on the amino acid sequence, peptide compounds form various morphologies and varying shapes ranging from spheres to long filamentous nanofibers. Peptide biomaterials possessing nanofiber morphologies, such as β-sheet peptides and peptide amphiphiles, have been explored as immune-modulating materials in immunotherapies for infectious diseases, cancer, or inflammatory conditions and depots for sustained delivery of drugs.84 These self-assembled peptide nanofibers rich in β-sheet structures have been shown to elicit strong antibody responses with minimal inflammation. While nanoparticles have been reported to have fast clearance from circulation and produce a milder immune response, nanofibers have increased retention and elevated immune responses without the need for additional adjuvants. Furthermore, fibrillar biomaterials can influence toll-like receptor (TLR) activation, inflammasome signaling, and T-independent B signaling and are used for anti-tumor CD8+ T cell responses.80,84

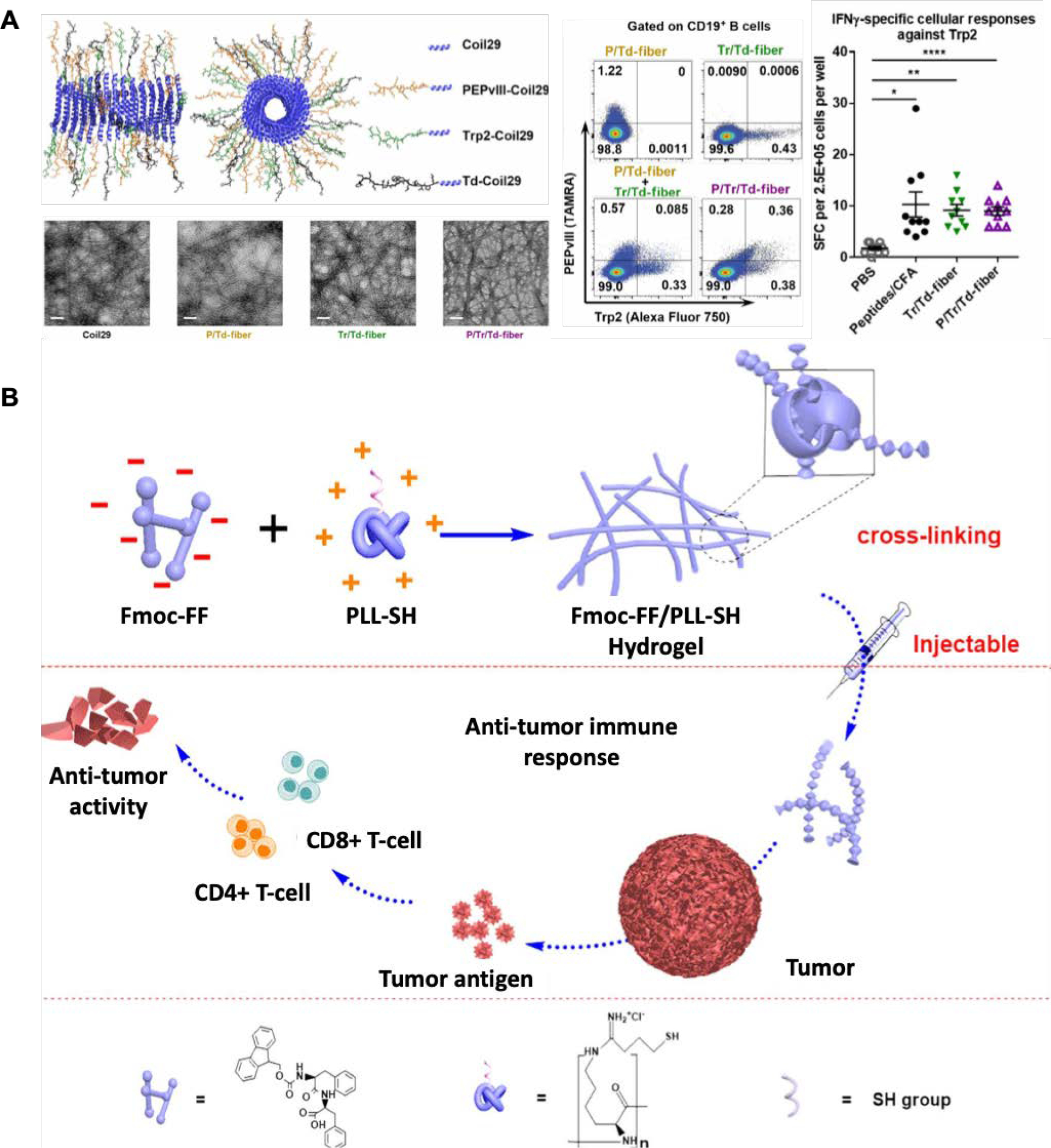

Work by the Collier group significantly advanced the area of peptide conjugates and supramolecular peptide hydrogels in immune-modulation.74–76,80,84–88 They highlighted the Q11 peptide nanofibers that can raise strong immune responses without adjuvants when conjugated to selected B and T cell epitopes. The antibody response to the fibers was CD4+ T cell-dependent and yielded high-affinity antibodies. Only the DCs that took up the Q11-epitope fibers demonstrated the expression of DC activation markers, CD80/86. They designed biomaterials with immunologically active properties, such as reactive T cell epitopes, that can boost responses to delivered antigens and induce desired immune phenotypes. In one study, they designed self-assembling polypeptide nanomaterials inspired by glatiramoids, a class of immunomodulatory linear randomized copolymers. They created a supramolecular nanomaterial platform consisting of randomized peptide epitopes that can act as a Type 2/TH2/IL-4 adjuvant.88 This glatiramoid-Q11 peptide analog was composed of amino acids such as lysine, glutamic acid, tyrosine, and alanine. They found that this peptide increases the uptake of nanofibers by APCs, increases injection site retention, and elicits Type 2 T-cell and B-cell responses. Almost all DCs acquired the nanofibers within 24 hours while subsequently producing specific IgG antibodies. Unlike Alum which activates the innate immune system by causing inflammation, the Q11 nanofibers stimulated IL-4 and IL-5-producing cells in vivo, thereby acting as a non-inflammatory adjuvant. Furthermore, they influenced the differentiation rather than proliferation of T cells into IL-4-producing T cells with a TH2 phenotype. This group also utilized the Coil29 peptide to generate antigen-specific CD8+ T cell responses comparable to peptide/complete Freund’s adjuvant (CFA) emulsions (Figure 3A).76 This system enables the simultaneous delivery of multiple peptide antigens through the co-assembly of multiple epitope-carrying peptides into a single nanofiber. They designed this multiepitope Coil29 nanofibrous platform to carry CD4+, CD8+, and B cell epitopes. These fiber vaccines induced IgG antibodies that bind specifically to EGFRvIII, a tumor-associated receptor, to mediate tumoricidal responses. A humoral and cellular immune response was elicited to enhance therapeutic effects in a B16vIII tumor model.

Figure 3:

A. Multiepitope Coil29 peptides exhibiting α-helical morphologies delivering both B cell and T cell peptide epitopes demonstrating uptake of the fluorophore-labeled peptides by CD19 B cells and eliciting a robust cellular response against Trp2 epitopes.76 B. Example of an immunomodulating peptide hydrogel formed using Fmoc-FF and PLL-SH co-assembled through electrostatic interactions and used for anti-tumor therapy. The injectable hydrogels activated a Th1 cell response and efficiently suppressed tumor growth.92

The cells part of the innate immune system are typically the first responders to the implantation of biomaterials, and their interaction will determine the host response that is evoked. In one example, multi-domain peptide hydrogels were formed, and the positively charged peptide conjugates that included either lysine or arginine caused an inflammatory response and induced the recruitment of immune cells such as inflammatory monocytes, polymorphonuclear myeloid-derived suppressor cells, macrophages, NK cells, T cells, and B cells.64 NK cells were observed on day 1 after material injection and were found to secrete cytokines and chemokines to attract other cell types. A self-assembled peptide consisting of arginine, leucine, aspartate, and glutamic acid was found to form an ordered nanofibrous hydrogel and promoted the recruitment and maturation of dendritic cells.89 The self-assembled peptide melittin-RADA32-DOX was shown to activate natural killer cell recruitment after in vivo injection.90 Additionally, they documented M2 pro-tumorigenic macrophage depletion. In another study, a 7-amino acid long peptide formed a self-assembling hydrogel and was modified with toll like receptor 7/8 (TLR 7/8). This led to the activation of macrophages towards anti-tumoral phenotype and elicited innate anti-tumoral activity.91

Many other nanofibrous self-assembling peptide hydrogels have been used to modulate immune function. A further example includes the work by Xing et al., where they utilized the charge difference of poly-L-lysine (PLL)-SH and N-fluorenyl methoxycarbonyl diphenylalanine (Fmoc-FF) peptide, facilitating enhanced entanglement between the two materials and creating a self-assembling peptide hydrogel that exhibits tunable rheological properties.92 Since the hydrogels have a helical nanofiber structure similar to the fimbrial antigen, it was found that the helical form of the self-assembled nanofibrous structures activated T cell responses and prevented tumor growth in B16 melanoma mice models (Figure 3B). The tumor-bearing mice receiving the hydrogel treatment showed a significant increase in CD4+ and CD8+ T cells and CD3+ cells. The chemical functionality of peptide hydrogels can also manipulate host responses at the early stages of inflammation.

Positively charged multidomain peptides (MDPs) have been reported to have strong immunostimulatory properties and thus are proposed as effective adjuvants.46 Canonical amino acid residues comprise these MDP hydrogels that self-assemble into β-sheets with divalent ions to form supramolecular hydrogels. It was previously found that including charged Asp or Glu residues leads to minimized inflammation. In contrast, inflammation can be increased when Lys or Arg residues are included in the peptide sequence. The MDP’s, Ac-KK(SL)6KK-Am and Ac-RR(SL)6RR-Am, adjuvant potential was assessed to cause Th2 immunity and antibody production. It was shown that the positively charged peptide hydrogel was able to act as an antigen depot to release the ovalbumin (OVA) vaccine. Both MDPs generated higher antigen-specific IgG titers than the unadjuvanted control with a small Th1 response and a biased Th2 immunity in C57BL/6J mice; however, the mechanism of action still needs to be elucidated. Lopez-Silva et al. designed MDP hydrogels displaying different surface charges and tested the immune response against these materials.64 The study revealed, similar to prior observations with proteins and polysaccharides, a strong association between pro-inflammatory responses and positively charged peptides with high immune cell infiltration, collagen deposition, and blood vessel formation in C57BL/6 mice. In contrast, negatively charged peptides elicited a minimal inflammatory response, minimal immune cell infiltration, lack of angiogenesis, and fast remodeling without excessive collagen deposition.

Aiming to overcome the immune evasion mechanisms in ICI therapy, such as the absence of T cell infiltration, downregulation of MHC-I, and loss of tumor-associated antigens, Wan et al. developed a bee venom peptide (Melittin)-polyethylene (MRP) based hydrogel that induces tumor cell death.93 Melittin has recently been reported as an immunotherapeutic agent due to promoting antitumor cytokines and activating CTLs and NK cells. Furthermore, it can trigger tumor-associated macrophage reprogramming to reverse the immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment (TME). This MRP hydrogel system was found to release melittin and modulate the immune environment by releasing tumor radiotherapy metabolites and causing repolarization of M2-like macrophages toward an M1-like phenotype. When this system was combined with an ICI, aPD-1, the antitumor effects increased, and the MRP system augmented the ability of the PD-1 blockade to suppress the growth of tumors.

An adjuvant-free peptide hydrogel vaccine system was produced by Su et al., using two different synthetic epitope-conjugated peptides (ECPs; OVA and CTL epitopes from melanoma-associated antigen, MAGE). This promoted DC maturation which in turn caused T cell priming through the activation of the NF-κB pathway which is an essential mediator in regulating the innate and adaptive immune responses. Thus the promotion of antigen-cross presentation greatly enhanced the adaptive T cell immune response, and enhanced the expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines.94 These examples show that the many advantageous properties and a wide variety of possible modifications of peptide hydrogels render them favorable and robust candidates for immune-modulatory applications. Their use in cancer immunotherapy applications is becoming apparent. Thus, the remainder of the review introduces cancer pathways that can be targeted through biomaterials and discusses peptide hydrogels for immune-modulation in cancer immunotherapeutic applications.

3. Immunomaterials for Cancer Applications

There are two ways that hydrogel biomaterials can be used in applications for increasing cancer immunotherapy efficacy; through direct immune-modulation by the material itself or through the delivery of immunotherapeutic agents. Here, we discuss some cancer pathways that can be targeted and then introduce and highlight examples of immunomaterials for cancer applications.

3.1. Targeting Cancer Pathways for Immune-modulation

Immunomodulation by biomaterials can be achieved in a TME by targeting several pathways and/or cells. Immunomodulation can be governed in the TME by targeting everyday interactions, including direct and indirect cell-cell receptor interactions, soluble factors (interleukins (ILs), chemokines, interferons (IFNs), cytokines, colony-stimulating factors (CSFs)), enzymes (proteases and protease inhibitors), and extracellular matrix (ECM) biomechanical properties.95 Tumor cells undergo a fast mutation process resulting in new proteins being expressed on their surfaces called neoantigens.96 These neoantigens can be recognized by host immune cells by being taken up by cells, presented by MHC class I and II receptors on APCs, and then presented to the T cells through T cell receptors (TCR) (Figure 4A). Antigen-presenting cells (APCs) must first take up the antigen, undergo proteolytic processing, and then present the epitope peptide as a compound with MHC class I or II on the cell surface. These interactions develop into immunological synapses (connections formed between an APC and T cell) that initiate signaling. Recently, the development of vaccines for cancer immunotherapy has focused on DC-targeted vaccines using hydrogel biomaterials as adjuvants or antigen delivery vehicles. This serves as a target for developing immunomaterials aiming to increase the uptake of antigens by APCs for improved subsequent T cell activation. Immunomodulating biomaterials targeting antigen presentation can involve changing the antigen or MHC-I expression levels and altering antigen processing and T cell activation.97 In addition, modulating DCs into a semi-mature phenotype can affect their ability to produce strong co-stimulatory signals that may lead to an immature immune synapse with T cells, resulting in T cell anergy and destruction of cellular cancer immunity.98

Figure 4:

Immunomodulatory mechanisms and potential targets in cancer. A. Presentation of cancer antigen by APC to T cell, B. Co-receptors between DCs and T cells influencing T cell activation. C. Antigen-independent recognition of cancer by NK cells. D. Production of tumor-specific antibodies by B cells. E. Release of proinflammatory cytokines to elicit anti-tumor activity. (Created with BioRender.com)

Cell-cell interactions are not limited to MHC-TCR interactions as several co-receptor interactions also have immunomodulatory effects, such as CD40/CD40L, CD70/CD27, CD80/CD28, and CD86/CTLA-4. CD80/CD28, CD3/CD28 interactions which are stimulatory for T cells, and CD86/CTLA4, PDL1/PD1, CD112/TIGIT, CD48/2B4 leading to immunosuppression (Figure 4B). Therefore, designing a material that serves as a reservoir incorporating anti-tumorigenic or T cell activating signals to deliver sustained and proliferating T cells can allow us to overcome the shortcomings of cellular immunotherapy mentioned above.

Another interaction, or the lack-there-of, is cancer cells losing MHC I molecules as an immune evasion mechanism. This loss is due to the cancer cell microenvironment interactions during which mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPK, potent activator of MHC I expression on cells) are inhibited, resulting in the loss of the MHCs, which prevents T cell-mediated cytotoxicity.99 In this case, NK cells can detect cells missing MHC I and select them for killing (Figure 4C). NK cells are increasingly becoming targets for cancer immunotherapy. It has also been reported that NK cells express killer cells immunoglobulin-like receptors (KIRs) that are immunogenetic determinants of the outcome of cancer. Therefore, in one study, a peptide:MHC DNA vaccine was designed and used to immunize targeting one of the KIR receptors.100 The vaccine construct was found to activate NK cells in both the liver and the spleen in vivo. Biomaterials tailored to increase the proliferation and activation, as well as the delivery of NK cells, can be an attractive strategy to target cancer cells without self-antigens (MHC I).

Antibody-dependent mechanisms in immunomodulation result from indirect interactions between cells and receptors. B cell immunity can potentially produce tumor-specific antibodies (Figure 4D). This interaction has two options, the antibodies binding to the tumor cell surface initiate NK cell activation and cytotoxicity, or the bound antibodies on the tumor surface interact with immune cells creating a different form of immune synapse resulting in phagocytosis of tumor cells.101 Biomaterials aimed to increase the signaling of these pathways or in the delivery of antibodies directly to the tumor can be an option for immune-modulation.

Soluble immunomodulatory factors such as chemokines, ILs, IFNs, the TNF superfamily, CSFs, and the transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β) superfamily can be delivered using a self-assembled injectable material to affect cancer immunity and cytotoxicity. The T cell chemokine receptor CXCR3 can detect chemokine gradients and migrate to tumor niches 102. ILs, on the other hand, participate in carcinogenesis, cancer immune evasion, and cancer immunity 103. IL-1 is pro-inflammatory and takes a role in carcinogenesis but, at the same time, has anti-tumor effects. Similarly, IL-10 has a dual effect by inhibiting anti-tumor responses and eliciting cytotoxicity. IL-2 also shows strong anti-tumoral activity (Figure 4E). Other soluble factors exhibit roles in cancer immunomodulation, which are explored in the literature in more detail 104–106.

3.2. Immunomaterials Targeting Cancer

Several strategies are under investigation to mediate favorable interactions between the biomaterial and the host immune system. One approach based on material design considers optimizing a given biomaterial’s physical and chemical properties (e.g., surface chemistry, topography, size, shape, hydrophilicity) to elicit a desired immune response.107,108 Surface modifications involving integrin interactions or protein adsorption that affect affinity or adhesion to the biomaterial can influence immune cell infiltration to the implant site (e.g., rolling and adhesion of monocytes) as well as the pro- or anti-inflammatory status of these cells.109–112 The material’s size, shape, stiffness, and surface roughness also influence the activation, infiltration, and cytokine secretion of different immune cells.14,113,114 Micropatterned surfaces that physically confine or conform macrophages to a specific shape (spread versus aligned and elongated) can directly alter their phenotype,115,116 Meanwhile, size changes in the nano or micro scale influence the cytokine production of dendritic cells (pro- versus anti-inflammatory), platelet activation, or cellular uptake and antigen-presenting cell activation.14 Changes in surface roughness affect immune cell activation through protein affinity and adsorption to the surface. The shape of biomaterials also influences the phagocytic activity of macrophages, maturation and cytokine secretion of dendritic cells, and the recruitment of neutrophils.117–120

Another strategy for immunomodulation includes the delivery of immune-modulating agents to tumor sites which can enhance their activity. It diminishes possible side effects or can increase immune responses by promoting the cell’s functions.121–123 Natural or synthetic polymers in a hydrogel or micro/nanoshell form can be used to trap antigenic secretions of embedded cells, preventing nearby immune cell activation and enhancing the success rates of cell transplantation,124,125 Meanwhile, for cell-based immunotherapies, similar strategies are employed to overcome insufficient localization at the injury/tumor site.126 In treating cancer and inflammatory diseases, targeted delivery of immune cells or immune-modulating agents using biomaterials are being investigated. For example, Smith et al. used porous alginate scaffolds as delivery vehicles for chimeric antigen receptor T cell and interferon (IFN) stimulator agonists against heterogeneous tumors that do not respond to systemic delivery of these immunomodulators.127 This corelease allowed substantial densities of the T cells that destroy tumor cells and high concentrations of stimulants that activate APCs to mount an anticancer response. Feng et al. developed a mannose receptor-targeted delivery system for antigen delivery to macrophages and dendritic cells to efficiently induce cellular and humoral immune responses.128 They conjugated mannose-modified chitosan with OVA-encapsulated poly(lactic-co-glycolic-acid) microparticles, which promoted dendritic cell maturation due to the mannose receptors on DCs improved antigen presentation efficiency, and, subsequently activated T cell response in mice models. While these scaffolds hold promise in this area, physical self-assembling nanofibrous hydrogels are gaining traction due to their immunomodulatory and tunable properties. The following section will focus on immune-modulatory peptide hydrogels for cancer applications.

4. Peptide Hydrogels as Immunomaterials for Cancer

In this section, we discuss the roles of peptide hydrogels as immunomaterials through direct immune-modulation as adjuvants and delivery vehicles for various cancer immunotherapies. Immunotherapy aims to elicit immune responses that will become immunological memory against cancerous cells and tumors. We will discuss how peptide hydrogels can augment these responses leading to better treatment efficacy.129 Peptide-based bioconjugates form supramolecular, injectable materials that deliver immunotherapies. Furthermore, peptide sequences can directly interact with the immune cells in a receptor-dependent or independent manner to elicit a change in the immune response. The following sections will highlight examples of peptide hydrogels as adjuvant systems and for the delivery of antigens in vaccines, immune cells, cytokines, and checkpoint inhibitors.

a. Immunomodulating Peptide Hydrogels and Their Role as Adjuvants

Supramolecular peptide hydrogels exhibiting immune-modulating properties have recently been reported as adjuvants in increasing immune responses. In many cases, nanofibers do not require additional adjuvants as they have chemical definition, modularity through the non-covalent construction, and raise strong immune responses through various mechanisms.75 This section highlights the immune-modulating effects of various peptide hydrogels and their implementation as adjuvant systems.

Nanofibrous hydrogels composed of peptide bioconjugates have been reported to act as a 3D matrix to augment vaccine responses and entrap immune cells while contributing to the immunogenicity of the vaccine. The nanofibrils are deemed essential for their antigen-loading ability. Self-assembling peptides are promising adjuvants as they are biocompatible and elicit a high titer of antibodies while inducing a humoral and cellular immune response. One of the first adjuvant hydrogel systems was designed from the self-assembled Q11 (Ac-QQKFQFQFEQQ-Am) peptide.142 A robust immune response was elicited when this system was conjugated to pathogen-associated peptide epitopes derived from the OVA antigen. The Q11 peptide conjugate capable of forming nanofibers was found to carry ovalbumin SIINFEEKL epitope to elicit specific CD8+ T cells without any adjuvants.75 Assembly of the OVA peptide into nanofibers allowed for high IgG titers without any adjuvants due to the surface display of the epitope on the fibrils. No strong antibody response was generated without the covalent coupling between the Q11 fibrilizing domain and the epitope domain. Therefore, the adjuvant properties were dependent on the covalent attachment. Collier et al. developed many self-adjuvating peptide nanofiber vaccines that can be internalized by DCs and show DC activation through the presence of the markers CD80 and CD86; however, only the DCs that acquired the material increased marker expression. The DCs then process and present the antigen to T cells in the draining lymph node.87 These epitope-bearing nanofibers showed antigen-specific differentiation of T cells and a high-titer, high-affinity IgG. They were found to be superior to those induced by alum and comparable to those caused by complete Freund’s adjuvant (CFA).

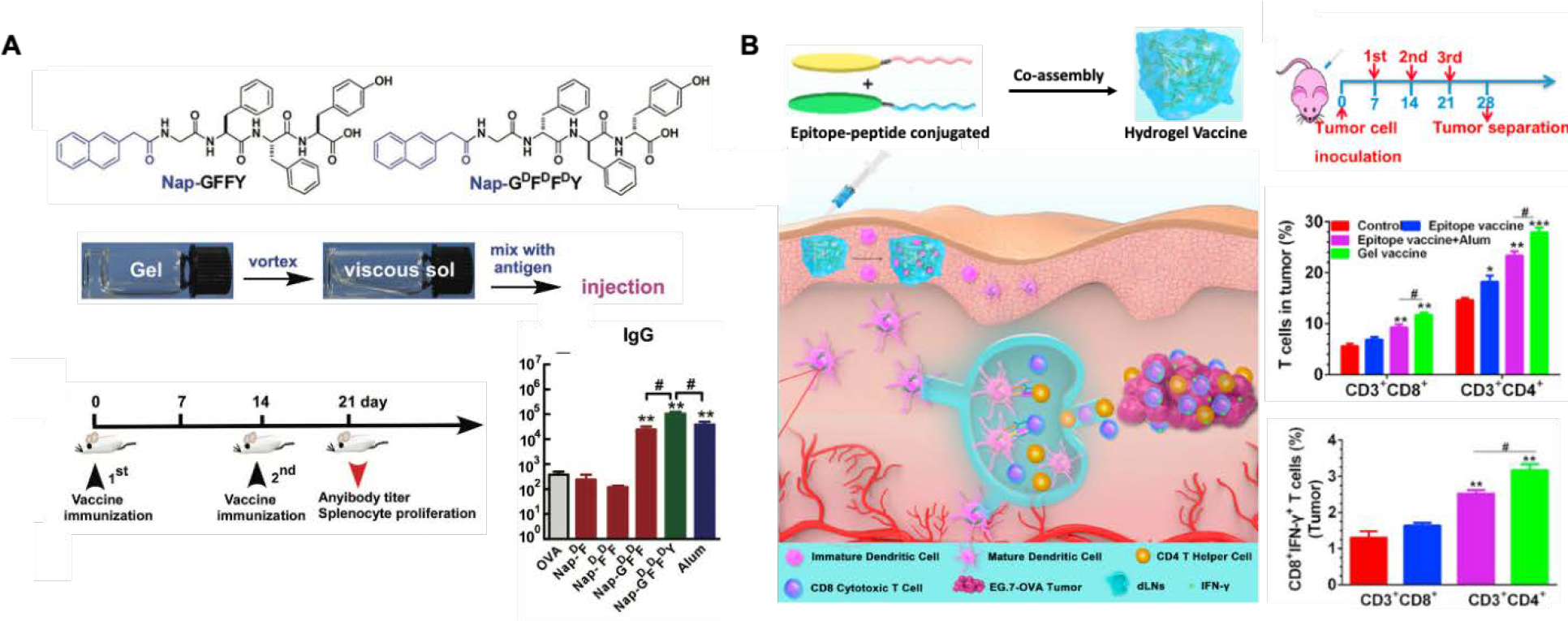

Another widely studied peptide adjuvant capable of forming a hydrogel is based on the short peptide sequence GFFY and has been reported for various applications.143–146 It was found that this peptide-functionalized with napthylacetic acid (Nap) strongly promotes the production of IgG2a antibodies and Th1 and Th2 cytokines against B16-OVA tumors.147,148 (Figure 5A) The Nap in the peptide bioconjugate served as an efficient aromatic capping group to allow for hydrogelation while stimulating CD8+ T cell responses and reducing tumor-associated inflammatory responses contributing to the development and progression of tumors.147 The hydrogels significantly enhanced the IFN and IL-6 cytokines which induced the proliferation and differentiation of CD8+ T cells and the formation of CTLs. This induction of immune responses was associated with the ability of the peptide hydrogel system to enhance antigen uptake and DC maturation, along with prolonged lymph node accumulation. The effects of the L versus D enantiomer of this peptide hydrogel system were also studied. The OVA antigen release from both gels was similar, and it was found that incorporating the antigen within the nanofiber networks allows for the protection of the antigen against digestion, thereby prolonging its duration in vivo. Both L and D-gels were reported to increase the OVA antigen uptake due to the endocytosis of the nanofibers and the adherence to the cell membrane of the DCs and localization in the lysosome. However, for the D-gel, the percentage of OVA molecules in the cytosol was higher than the L gel, which was said to be due to the release of the antigen at a lower pH being faster in the D-gel, indicating weaker binding. This antigen escapes from the lysosome and discharges into the cytosol, which is essential for cross-presentation and CD8+ T cell stimulation. The D-gel was found to induce DC maturation and prolong the accumulation of antigens in the lymph nodes better than the L-gel. Both gels were also found to increase IL-6 and TNF-a production by DCs, however, the L-gel was found to increase the production of anti-OVA IgG1 but did not affect IgG2a and IgG2b, while the D-gel increased the production of IgG1, IgG2a, and IgG2b. D-peptide hydrogels typically exhibit slightly better stability in biological systems and, therefore, can show better adjuvant potency than the L- enantiomers. A phosphorylated derivative of the tetrapeptide was synthesized, and it was hypothesized that the phosphorylated gel could protect phosphorylated antigens from being dephosphorylated and degraded, resulting in an increased production of antibodies for phosphorylated proteins.145 It was found that the phosphorylated peptide hydrogel interacted with phosphorylated antigens to form co-assembled nanofibers. Due to this interaction, they were slowly released and protected from being dephosphorylated, thus increasing the production of antibodies that recognize phosphorylated proteins. Upon adding a phosphatase enzyme, the phosphorylated gel became stiffer due to the phosphorylation of the tetrapeptide conjugate that forms the hydrogel, thus protecting the phosphorylated antigen. The antigens are predicted to be dephosphorylated after release and before APC uptake.

Figure 5:

A. D-tetrapeptide-based (Nap-GFFY) hydrogel assembled through a heating-cooling process with thixotropic properties allowing the incorporation of antigens. The adjuvant properties are elicited through the potent CD8+ T cell stimulatory properties and the increase in the production of anti-OVA IgG antibodies in the plasma.143 B. Peptide conjugates chemically coupled with epitopes co-assembling into a supramolecular self-adjuvating peptide hydrogel with nanofiber structures. The epitopes target CD8+ or CD4+ T cells, increasing antigen cross-presentation in DCs. The adjuvant hydrogel maximized T cell priming, leading to higher epitope-specific CD8+ and CD4+ T cells than the free vaccine.94

The sequence of the Nap-GFFY peptide was deemed necessary as a study substituting and/or changing the position of the amino acids concluded that both the position of each amino acid and the number of aromatic amino acids were deemed necessary in determining the potency of the adjuvant.130,131 The absence of any amino acid in the Nap-GFFY hydrogel sequence was shown to cause a 10x reduction in the antibody titer after OVA vaccination in C57BL/6 mice, highlighting the importance of choosing specific amino acids in peptide bioconjugates that form hydrogels. It was found that if the phenylalanine amino acids were substituted with Gly, the compounds did not self-assemble, showing the importance of the aromatic amino acids in hydrogel formation. Moreover, if the tyrosine was replaced, the compounds could still self-assemble, but there was a reduction in inducing humoral immunity, pro-inflammatory cytokine production, and DC maturation. These sequences are reported to use noncanonical amino acids and modifications that can potentially introduce bioactive amino acid degradation products that can cause undesirable effects in vivo. Therefore, when designing novel peptide hydrogels, it is essential to remember that the design of self-assembling peptides leading to different chemical structures affects the nanostructure morphologies and changes in biological function.

Another advantage of peptide hydrogels is the possibility to chemically conjugate additional functional peptide sequences to the self-assembling peptide sequences to obtain a hydrogel that can target specific pathways. Supramolecular co-assembly of peptides can also be used as a vaccine platform where the antigen loading and composition can be tuned. A co-assembled hydrogel was reported to show excellent self-adjuvating properties leading to the promotion of DC maturation and the priming of T cells.94 The peptides KWKAKAKAKWK and EWEAEAEAEWE were reported to self-assemble and be used as OVA antigen epitope carriers, targeting CD8+ and CD4+ T cell receptors (Figure 5B). They were chemically conjugated to the self-assembling peptides by solid-phase synthesis to create epitope-conjugated peptides (ECPs) that co-assembled through intermolecular forces between the amino acid residues. These include electrostatic interactions between the lysine (K) and glutamic acid (E) residues, π−π stacking between the aromatic tryptophan residues (W), and hydrophobic interactions among the water-insoluble epitopes. It was found that this co-assembled ECP vaccine activated the MyD88-dependent NF-kB signaling pathway in DCs and elicited T cell immunity. Firstly, the self-assembling ECP resulted in superior antigen uptake, which enabled a strong activation of DCs compared to the naked peptide. The co-assembled peptide adjuvant systems enhanced the antigen immunogenicity by increasing antigen uptake and presentation by DCs and maximized T cell priming efficiency compared to the free vaccine. Co-assemblies of T cell epitopes and TNF B-cell epitopes into nanofibers were also used for anti-TNF immunotherapy.86 It is important to remember that knowledge of immunogenic epitopes on the protein antigen is required when designing these systems.

To enhance the CTL response, Xu et al. developed a pH-responsive supramolecular peptide adjuvant capable of activating the NF-κB pathway.132 The Ada-GFFYGKKK-NH2 peptide-based nanogel was used as an adjuvant delivery system, enhancing internalization and cross-presentation (uptake, process, and present antigens with MHC class I molecules to T cells) of the antigen as well as upregulating CD80 and CD86 expression and inducing pro-inflammatory cytokine secretion by DCs. The synergistic effect of efficient antigen cross-presentation and activation of the NF-κB pathway resulted in the transformation of CD8+ cells into antigen-specific CTLs that are important for tumor eradication. When tested in animal models, the peptide hydrogel adjuvant prevented oncogenesis in naive mice and blocked tumor growth in melanoma-bearing mice, increasing survival.

While peptide hydrogels can directly modulate immune responses and possess adjuvant properties, another aspect of immune-modulation is using peptide hydrogels to deliver immunotherapies. The following sections focus on utilizing these peptide hydrogel immunomaterials to deliver vaccines, immune cells, ICIs, monoclonal antibodies, and cytokines.

b. Peptide Hydrogels for Vaccine Delivery

Supramolecular peptides have a unique advantage in cancer vaccine immunotherapy as they can assume the role of all components. The self-assembled motifs of supramolecular peptides such as α-helices and ß-sheets naturally resemble the conformation of B-cell epitopes, granting the use of these peptides as antigens.149 Some self-assembling peptides also inherently possess CD4+ T-cell epitopes, such as the Coil29 peptide.150 As discussed in the previous section, supramolecular self-assembling peptides form antigen depots as an adjuvant, enhancing antigen-presenting cell function and priming of T-cells.74,132,151,152 When utilized as vehicles, supramolecular self-assembling peptide systems can induce cellular immunity against tumors and facilitate targeted and controlled delivery of many immunotherapeutic agents such as antigens, antibodies, adjuvants, immune cells, and drugs.153

Song et al. performed ring-opening polymerization (ROP) of L-Ala NCAs with mPEG-NH2 as the initiator for the development of a mPEG-b-poly(L-alanine) (PEA) copolymer.133 The resulting PEA self-assembled into hydrogels due to hydrophobic interactions among the polypeptide blocks and through the formation of α-helix and β-sheet secondary structures. The PEA self-assembling hydrogels were found to be injectable and were loaded with tumor cell lysates (TCL) as the antigen, granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF), and two ICIs, anti-PD-1, and anti-CTLA-4 antibodies. Sustained release of the vaccine components was observed over two weeks. The TCL aided in recruiting endogenous DCs from the host, while the GM-CSF helped with the maturation of the DCs. The matured DCs migrated to the lymph nodes and initiated antigen-specific T cell priming, eliciting a potent CTL response. The PEA polypeptide hydrogel drug delivery system for combinatorial immunotherapy resulted in enhanced anti-tumor activity against melanoma and 4T-1 tumors. In a previous study, Song et al. prepared a similar polypeptide copolymer, mPEG-b-poly(L-valine) (PEV), by the ROP of L-Val NCAs with mPEG as the initiator.134 These PEV polypeptide hydrogels were loaded with TCL and a TLR3 agonist, polyinosinic:polycytidylic acid (poly(I:C)). They demonstrated sustained release of TCL and poly(I:C) from the hydrogels over eight days and successfully recruited and matured DCs in vitro. Furthermore, the PEV hydrogels with TCL and poly(I:C) enhanced T cell immune response in vivo and induced efficient antigen-specific CTL response in mice with B-16 melanoma.

Focusing on antigen uptake by DCs and DC maturation, Shan et al. used the self-assembling Hepatitis B core protein/OVA peptide system as the delivery vehicle, antigen, and adjuvant all at once for combinatorial cancer immunotherapy.154 Upon administration, the vaccine system accumulated in the lymph nodes upon administration, prolonging antigen exposure to dendritic cells, inducing their maturation, and enhancing their antigen-presenting function, leading to a robust CD8+ T-cell response. In addition, the vaccine-induced antigen-specific CTL responses effectively targeting and eliminating cancer cells in C57BL/6 mice models. The vaccine elicited antitumor immunity and decreased mouse model tumor growth, prolonging mice survival. When the peptide vaccine was administered with a low dose of the chemotherapeutic drug paclitaxel, a more prominent decrease in tumor growth and metastasis was observed compared to using each treatment alone. Yang et al. utilized the nanofibrous RADA16 peptide with alternating hydrophobic and hydrophilic amino acids, which self-assembled in cell culture media with a β-sheet conformation. They encapsulated naïve BMDCs and OVA or TCL.155 They observed that their RADA16 hydrogels were cytocompatible, nonimmunogenic, and functioned as exogenous DC-based vaccines by supporting encapsulated BMDCs and providing a matrix for antigen uptake resulting in BMDC maturation. The nanofibrous hydrogel provided a suitable matrix for the enrichment, attachment, and spread of DCs and maintained the viability and activity of DCs. Moreover, these hydrogels also performed as autologous DC-based vaccines due to the sustained release of antigens from the hydrogels resulting in the recruitment of host DCs. Together, their hydrogels promoted the homing of DCs to lymph nodes and the stimulation and activation of tumor antigen-specific T cell immunity against EG7-OVA lymphoma tumors in mice.

In contrast, Wang et al. developed a nanofibrous peptide-based supramolecular hydrogel-OVA platform to effectively stimulate and activate immune cells (Figure 6C).156 Their polypeptide precursors were prepared by solid-phase peptide synthesis, followed by a reduction with glutathione, resulting in self-assembled nanofibrous hydrogels with a β-sheet conformation. Adding ovalbumin to their polypeptide hydrogels resulted in uniform, denser nanofibers with slightly stronger rheological properties. They observed that mice vaccinated with hydrogels loaded with ovalbumin had a nearly 500 – 1800-fold increase in serum IgG, while splenocyte cytokine analysis revealed that their hydrogel vaccines had a 2.5 – 2.9-fold and 3.9 – 4.5-fold increase in IL-4 and IFN-γ respectively compared to control groups (free ovalbumin antigen). Moreover, they observed a 32 – 64% reduction in tumor growth in vaccinated mice with EG7-OVA tumors.

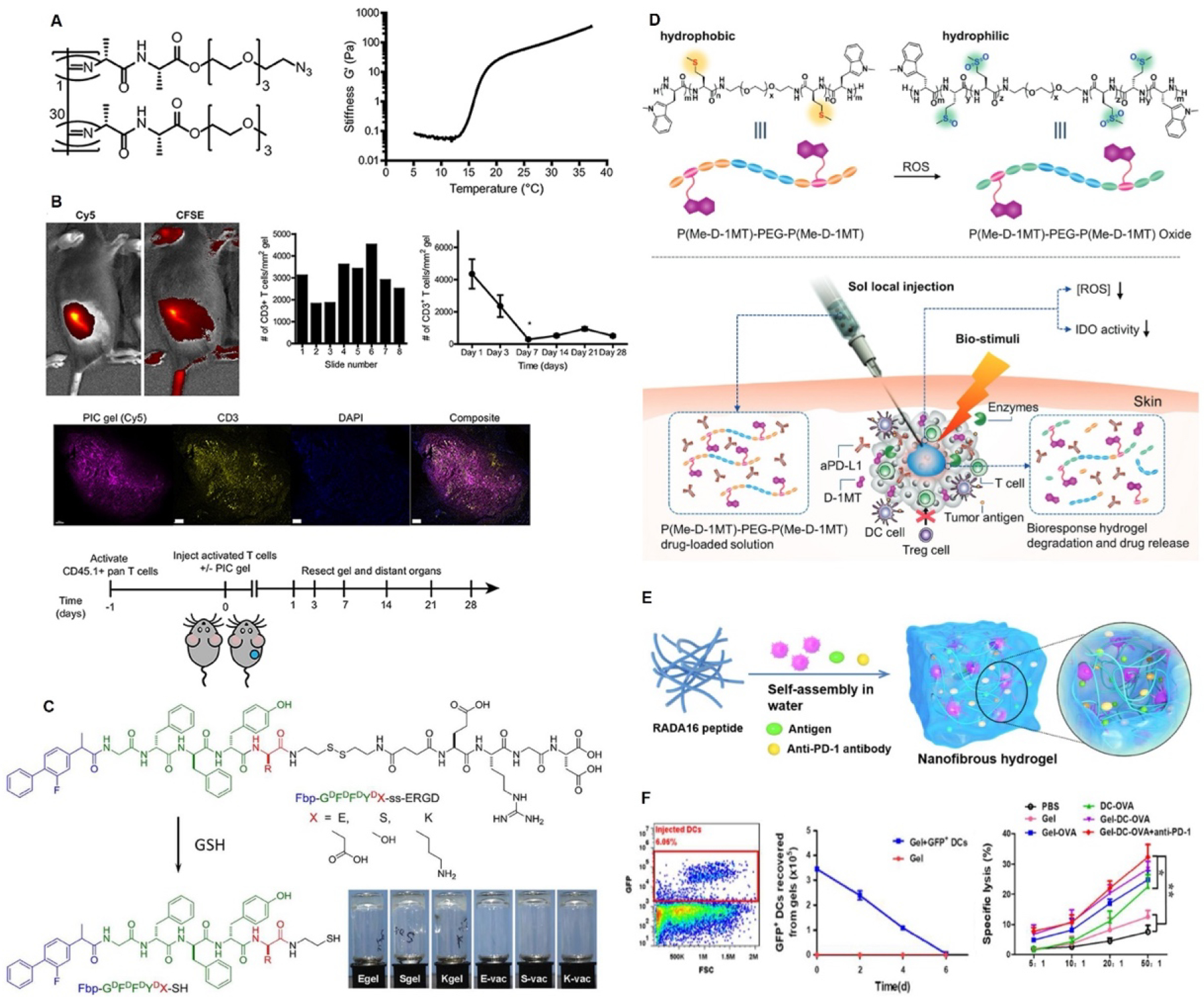

Figure 6:

Examples of peptide hydrogels for immunotherapy delivery. (A-B) PIC hydrogels for adoptive immunotherapies.126 A- PIC gel structure and temperature responsiveness of the peptide hydrogel. B- CD3+ T cell encapsulation into PIC gels and subcutaneous injection into mice. C- Co-assembled nanofibrous peptide hydrogels for cancer vaccine delivery.156 D- Schematic representation of local stimuli responsive ICI release and tumor micro niche modulation.135 (E-F) Schematic representation of the mechanism of action DC vaccine nodule and the DC encapsulation and efficacy.155

Self-assembling multivalent peptide vaccines formed by coupling three or more epitopes on a single self-adjuvanting domain is an appealing field of cancer vaccine immunotherapy. Multivalent vaccines are proved to be superior to single epitope vaccines as they can increase the magnitude and phenotype of T cell and antibody responses.157,158 The example by Su et al., reports a nanofibrous multivalent peptide hydrogel vaccine that was engineered using dual assembly of antigen epitope-conjugated peptides (OVA and CTL epitopes from melanoma-associated antigen, MAGE), to enhance the antigen-specific T cell immune response and the expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines.94 In another example, an OVA-derived cytotoxic T cell epitope was conjugated with a synthetic peptide amphiphile which self-assembled into cylindrical micelles resulting in multivalent epitope presentation.159 Enhanced uptake of these nanostructures by DCs was associated with the favorable interactions between the hydrophobic tail of peptide amphiphiles and DC membranes, subsequently improving antigen cross-presentation and T cell activation. Furthermore, the micellar structure protected its contents against degradation, concentrating the antigens and prolonging their interaction with APCs. Self-adjuvanting lipid core peptides (LCP) conjugated with two or four copies of OVA257–264 and/or OVA323–339 peptides were applied as a peptide-based cancer or infectious disease vaccines.160 The possibility of generating long-lasting memory CD8+ T cell responses by LCP-conjugated ovalbumin peptides was indicated in this study. Pompano et al. proposed multivalent self-assembling peptide nanofibers formed by the co-assembly of a high-affinity T cell and B cell epitopes as a potential candidate to develop vaccines and immunotherapies.161 Therapeutic mRNAs are the next generation of vaccines used for cancer immunotherapy and gene therapy. Multivalent self-assembling peptide-functionalized bioreducible polymers have been used for different RNA deliveries.162

c. Peptide Hydrogels for Immune Cell Delivery

Hydrogel delivery systems of immune cells for adoptive cell therapy have also been reported. In adoptive cell transfer, patient-derived leukocytes are isolated and modified in vitro before being transferred back to the patient. Several cell types in the literature have been tested for immune cell transfer for cancer therapy. These include CD8+ T cells, CD4+ T cells, Th17 cells, and NK cells.163 To achieve complex immunomodulatory functions such as T cell differentiation, modified hydrogels could be used. For example, Weiden et al. used polyisocyanopeptide (PIC) hydrogels with low gelation temperatures (16 °C) modified with azide-terminated monomers to induce immune cell modulation for adoptive cell therapy 126 (Figure 6 A, B). The thermoreversible behavior facilitates a simple cell encapsulation within the hydrogel matrix and allows for the retrieval of the cells. The authors modified PIC with RGD peptides to create hydrogels that increase cell adhesion and migration. The gels showed injectability and good T cell viability. In vivo injections showed a controlled release of the pre-activated T cells, showing a promising hydrogel platform for adoptive cell therapy. This was one of the first examples of peptide hydrogel development for T cell delivery. Unfortunately, there are very few examples of peptide hydrogels in delivering immune cells, but they show great potential for future applications.

T cell modification in vitro is a developing therapy modality. CAR-T cells are a revolutionary type of immunotherapy, gaining much attention recently. Here, patients’ T cells are collected and modified genetically to acquire a T cell receptor that can recognize a tumor antigen and induce cancer cell cytotoxicity.164 Originally, retroviral vectors were used to clone tumor-specific TCR and chains (α and β), resulting in CD8+ T cells that recognize specific MHC I-dependent antigens associated with tumors.165,166 This novel cell therapy showed promising results in treating hematological malignancies, and in 2017 the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved the first CAR-T cell therapy for acute lymphoblastic leukemia.167 However, there are several obstacles to successive CAR-T treatment for solid tumors today: i- systemic toxicity of CAR-T cells due to antigen specificity issues on the surface,168 164 ii- inadequate delivery of CAR-T cells to the tumor site following intravenous injection, although these cells have specific receptors for cancer cell antigens, the circulating volume in the human body is too large to obtain sufficient CAR-T cells in solid tumors,169 iii- CAR-T cells are exhausted by a hostile, immunosuppressive TME,170 and iv- Inadequate T cell infiltration into solid tumors. In contrast to hematological malignancies, solid tumors exhibit desmoplastic reactions. This causes a dense stroma, which makes the tumor ECM a barrier to drug and cell delivery.171 These issues demonstrate that we need a paradigm shift in immune cell delivery targeting cancer.

Today, this shift comes from the interdisciplinary field of biomaterials and immunoengineering. Hydrogel biomaterials allow for the delivery of cells with several advantages, including the ease of delivery to precise locations in the human body, they mimic the ECM of cell niches and provide cell survival and proliferation, and they are capable of manipulating the microenvironment to modify immune cell response such as preventing T cell exhaustion. For example, Atik et al. showed that low-viscosity hyaluronic acid hydrogels could be employed for CAR-T cell delivery 172. Their study aimed explicitly at intracranial delivery for brain tumors and was aimed to achieve homogeneous delivery of CAR-T cells compared to the conventional saline injections. Physical interactions between hydrogels are reported to inhibit passive diffusion of the stimulatory molecules allowing for a controlled release and activation of the CAR-T cells.173 This idea of having physical hydrogels is innovative and aligns with the underlying mechanisms of peptide hydrogel formation. The same physical gelation kinetics are present in peptide hydrogels with enhanced versatility and modifications. We believe the self-assembling physical interactions of peptide hydrogels make them great candidates for adoptive cell therapy and immunomodulatory molecule modifications and delivery. Even though no specific example exists today in this particular application, in the future, peptide hydrogels will prove themselves as high-performing cell delivery and combined immunotherapy delivery platforms.

d. Peptide Hydrogels for Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors, Monoclonal Antibodies, and Cytokine Delivery

Peptide hydrogels have also been reported to be used to deliver ICIs, MAbs, and cytokines. In a personalized and combinatorial approach against metastatic and recurrent tumors, Wang et al. encapsulated autologous tumor cells, an ICI, and a photothermal therapy agent within a peptide hydrogel system capable of tumor penetration.153 The Fmoc-KCRGDK peptide-based hydrogel was locally injected, and a near-infrared laser irradiation application triggered the release of tumor-specific antigens and the ICI, promoting maturation of DCs, infiltration of T-cells, and formation of immunological memory. The patient-specific approach successfully prevented tumor relapse and metastasis following surgical treatment in BALB/c mice models.

MDP hydrogels have 3D networks which enable them to encapsulate large biological molecules. Therefore, their stimuli-triggered and controlled drug-release capacities have been used as a delivery platform for bioactive molecules such as drugs, growth factors, cytokines, antibodies, and ICIs. Moreover, these hydrogels can decrease the effective dosage needed for the anticancer effect.10 For example, Yu et al. constructed an ICI (aPD-L1) loaded polypeptide hydrogel made of PEG and a polypeptide block containing L-methionine (Me) and dextro-1-methyl tryptophan (D-1MT) attached on either side (Figure 6D).135 This hydrogel was synthesized by ROP using amine-terminated PEG as an initiator. The authors observed that the triblock peptide polymer solution self-assembled into micelles and underwent a sol-gel phase transition by increasing the temperature. The hydrogel showed good cytocompatibility and reduced ROS levels in the tumor site, relieving the immunosuppressive tumor environment. The ICI-loaded polypeptide hydrogel-treated group in vivo demonstrated a prolonged antibody preservation time and a sustained release compared to the free drug-treated group, as well as delayed tumor growth and higher mice survival rate compared to the other groups. Notably, the hydrogel-only group displayed higher CD8+ T cell penetration than the free drug-treated groups. Moreover, the authors found that the combination of aPD-L1 and D-1MT causes an effective T cell immune response toward synergistic cancer immunotherapy.

A PEG-polypeptide hydrogel was used as a drug delivery reservoir for cancer chemoimmunotherapy in another study.174 The peptide hydrogel was shown to be injectable, biocompatible, and biodegradable with a sustained and prolonged drug release profile of the ICI, aPD-L1, and doxorubicin. Wang et al. highlighted the local delivery of camptothecin (CPT) and aPD-1 agents through a peptide hydrogel (diCPT-PLGLAG-iRGD).136 The PLGLAG peptide is a bioresponsive linker that is cleavable by an MMP-2 enzyme (overexpressed enzyme in the tumor extracellular matrix).137 The RGD peptide is known to promote the infiltration of anticancer agents into the tumor tissue.138 Furthermore, a supramolecular peptide nanotube (P-NT) hydrogel enhanced the local retention and sustained release of agents while reducing drug leakage compared to drug-free solutions. It was also observed that CD8+ T effector cells in the P-NT–aPD1–treated GL-261 brain tumor-bearing mice were higher than in aPD1(L)-treated and free (CPT + aPD1)–treated groups. As mentioned previously, the hydrogel delivery system using the RADA16 peptide sequence was developed by Yang et al. as a reservoir for the vaccine (dendritic cell (DC) + ovalbumin (OVA)) and ICI (aPD-1) delivery (Gel-DC-OVA+anti-PD-1) (Figure 6 E, F).155 Due to its hydrophilic and hydrophobic amino acids, the RADA16 peptide assembles into a hydrogel upon exposure to cell media or buffer solutions. According to their research, adding aPD-1 to the Gel-DC-OVA increased the activated DCs in the draining lymph nodes (dLNs) and significantly delayed tumor growth.

Unlike ICIs, cytokines directly boost the activity and growth of immune cells.175 Cytokine therapy regulates innate and adaptive immunity and displays enhanced anti-tumor efficiency 176,177. Hence, cytokine delivery via peptide hydrogels has drawn attention recently.139–141,178 Jiang et al. synthesized a polypeptide hydrogel Fmoc-FFF-Dopa which served as a delivery system for an antiangiogenic protein, hirudin, and an apoptosis-inducing cytokine, TRAIL, for a combination cancer treatment.139 They used an encapsulated protease enzyme permeable to small precursors to hydrolyze the reaction between Fmoc-F and FF-Dopa and convert them to a Fmoc-FFF-Dopa gelator for subsequent hydrogel assembly. In addition to presenting immediate recovery and shear-thinning behavior, the hydrogel demonstrated negligible toxicity. The oligopeptide hydrogel served as a reservoir allowing for a sustained release of the therapeutic agents and retention in the tumor. Hirudin affected the inhibition of thrombin-induced tumor angiogenesis, and TRAIL can activate a caspase-mediated apoptotic signaling pathway. The Hirudin/TRAIL-gel demonstrated inhibition of vascularization and blood vessel formation in the tumor tissue and has the highest level of apoptotic cells.

Similar precursors chosen in the study by Jiang et al. 139 was applied by Zhang et al. to obtain protease thermolysin (catalyst)-mediated Fmoc-F–FF-DOPA gelator formation.178 They used this oligopeptide hydrogel as a drug depot to co-deliver a tumor-homing immune nanoregulator (THINR) and the chemotactic CXC chemokine ligand 10 (CXCL10). THINR was composed of a Zinc 2-methylimidazole (ZIF-8)-based nanocarrier co-loaded with small interfering RNA that targets indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase-1 (siIDO1) and mitoxantrone (MIT), and later camouflaged with glioma-associated macrophage membrane (GAMM). The hydrogel only showed negligible cytotoxicity, and the THINR-CXCL10@Gel hydrogel presented good biodegradation, and shear-thinning properties, showing recovery behavior in five minutes. Moreover, all the drug-entrapped hydrogels displayed a sustained release. In vivo, the THINR-CXCL10@Gel injected group showed the most potent tumor regrowth inhibition effect and prolonged the mice’s survival among all treated groups. They justified the efficiency of their oligopeptide hydrogel-mediated drug delivery system in immunotherapy through the following sequence of events: i) MIT elevated the activation of blood-born immune T cells; ii) CXCL10 recruited blood-born immune T cell lymphocytes to the brain; and iii) siIDO1 silenced IDO1 which led to relieving Treg-related immune brakes and enhancing the anti-tumor immunity.

Poly (γ-ethyl-L glutamate)-based hydrogels have also been reported in the delivery of cytokines. In one report, the chemotherapeutic agent doxorubicin (DOX) and the cytokines IL-2 and IFN-γ were encapsulated inside a poly(γ-ethyl-L glutamate)-poly(ethylene glycol)-poly(γ-ethyl-L glutamate) (PELG7-PEG45-PELG7) hydrogel for B16F10 melanoma chemoimmunotherapy.140 The hydrogel showed good biodegradability and cytocompatibility, and drug-loaded hydrogels showed lower cytotoxicity than the free drug group. The co-loaded hydrogel with DOX/IL-2/IFN-γ reduced the anti-apoptosis Bcl-2 gene expression. At the same time, it enhanced the apoptosis gene caspase-3 expression, which resulted in increased apoptosis of the B16F10 cells. In another report by Wu et al., the cytokine, interleukin-15 (IL-15), and the chemotherapeutic agent cisplatin (CDDP) were encapsulated in mPEG-b-PELG diblock polymer.141 By elevating the temperature, PEG chains were partially dehydrated, and the β-sheet structure of the PELG chain was strengthened, resulting in micellar aggregations forming. The authors also mentioned that the increased sol-gel transition temperature after drug loading might be due to the hydrophilic effect of the drugs. An in vitro drug release assay of drug-loaded hydrogel displayed a biphasic (rapid and sustained) profile. In addition, cytotoxicity outcomes indicated significantly lower cytotoxicity of Gel + IL-15/CDDP compared to free drugs (IL-15/CDDP). Based on the in vivo degradation and biocompatibility results, the developed hydrogel was entirely degraded without long-term tissue damage. The superior anti-tumor efficacy of Gel + IL-15/CDDP over PBS, blank hydrogel, free drugs, and single-drug loaded hydrogels without any death in B16F0-RFP melanoma-bearing mice after 18 days was also elicited in their work. Combining IL-15 with CDDP enhanced the secretion of IFN-γ and IL-2, whereas that of IL-4 decreased, which had a combined effect on anti-tumor activity.

While supramolecular peptide hydrogels have been recently developed and used for immunotherapy delivery, their use in the delivery of monoclonal antibodies is scarce. However, due to their biocompatible, injectable, and nanofibrous properties, they show great potential to be used in this area.

5. Conclusion and Future Perspectives

Peptide hydrogels have emerged as a promising tool for immune-modulation in cancer treatments due to their ability to mimic antigenic behavior and modulate immune responses in a controlled and localized manner. These materials can be injected due to their shear-thinning and self-healing properties through various external physiological stimuli. Immune-modulation has been achieved through the direct interaction with immune cells and their supramolecular nanostructures influencing entrapment and controlled release. The display of antigen epitopes on the surface of nanofibers has led to numerous adjuvant-free vaccination possibilities and personalized vaccine platforms achieving immunity without inflammation and the possibility of an allergic reaction. Additionally, peptide hydrogels can deliver bioactive molecules such as antibodies and cytokines to modulate immune responses. This targeted delivery can help avoid the systemic side effects of traditional immuno-modulatory drugs and revolutionize cancer treatments. While peptide hydrogel materials have gained much popularity in this field, there are some limitations of these types of materials in comparison to traditional chemical polymer hydrogels. Peptide hydrogels typically form through non-covalent interactions which range from 1 to 5 kcal/mol, which are naturally weak and may not be sufficient for stable and highly ordered assemblies. They are also more expensive to produce and are difficult to form hydrogels that are stable for long periods of time when wanting to use these in a clinical setting. In fibrillar peptide biomaterials, it is also often difficult to achieve length control which influences cross-presentation, affecting cancer vaccination strategies. Lastly, many supramolecular peptide platforms do not have consistent morphologies, tend to be heterogenous, and lack controllability which could result in various immunotherapeutic outcomes.

Despite these challenges, there are many interesting future possibilities and directions where supramolecular peptide biomaterials can impact immune responses in cancer. The mechanisms of hydrogel immunomodulation need to be investigated with the outlook of achieving improved immunomodulation with new self-assembling sequences. While there are numerous examples of hydrogels obtaining a desired immune response, in many, if not most, cases, the exact mechanism of how these properties affect immune responses has yet to be discovered. The relationship between peptide hydrogels’ physical and mechanical properties (i.e., stiffness, porosity, topography, and electrical properties) and immune cell function and phenotype changes should also be directly explored at single-cell and systems immunology levels. This can improve the classification methods of which peptide sequences affect which biological processes. The development of biomaterials as a reservoir for immune cells has yet to be widely explored but possesses excellent potential to improve adoptive T cell therapy. Moreover, CAR-T cell therapy is an attractive emerging option showing great results for blood cancers but struggling with the delivery to solid tumors. Shear-thinning injectable hydrogels keeping the T cells active that can be locally injected into the tumor can allow this type of therapy to be a more effective and eventually the leading option for solid, aggressive cancers. The current developments in the machine learning use in biomaterial development would also be a potential expansion area in the peptide hydrogels where the potential peptide sequence hits with strong immunomodulatory effects can be predicted by silico models.179 In conclusion, peptide hydrogel biomaterials can generate and modulate interactions with immune cells affecting their response and functions. While more in-depth research on the immune-modulation mechanisms is needed, further analysis investigating hydrogel-immune cell interactions will aid in the design of novel immune-instructive hydrogels and translate their use for future cancer therapies.

Table 1:

Applications of reported immuno-modulatory peptide hydrogels.

| Class of immunomaterial | Peptide Sequence and Structure | Hydrogel Properties | Immuno-modulating Properties | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adjuvant | Nap-GFFY | - Phe amino acids allow for self-assembly. - Nap groups is aromatic capping group for hydrogelation. - Self-assembly stimulated by heating-cooling process and results with thixotropic properties. |

- Involved in stimulation of CD8+ T cell response and reduction of tumor-associated inflammatory responses. - Associated with inducing the production of IgG2a and cytokines Th1 and Th2, more specifically IFN-γ and IL-6. |

130,131,143–148 |

| Q11 (Ac-QQKFQFQFEQQ-Am) | - Self-assembles into a β-sheet-rich nanofiber network. - Self-assembly stimulated by water and physiological environments. - Co-assemble with various pathogen associated epitopes. |

- Nanofibers allow for uptake by dendritic cells involved in cross-presentation. - Co-assembly with T and B cell epitopes elicit a significant and specific immune response. -Elicits specific SIINFEKL CD8+ T cell responses. - Q11-OVA co-assembly is able to stimulate CD4+T cell responses. - The glatiramoid-Q11 analog (KEYA)n was able to elicit Type 2/TH2/IL-4 T-cell and B-cell responses, increases both APC uptake of nanofibers, and response to co-assembled epitopes. |

46, 74–76, 80, 86–88, 142, 150 | |