Abstract

The establishment of centromeric heterochromatin in the fission yeast Schizosaccharomyces pombe is dependent on the RNA interference (RNAi) pathway. Dicer cleaves centromeric transcripts to produce short interfering RNAs (siRNAs) that actively recruit components of heterochromatin to centromeres. Both centromeric siRNAs and the heterochromatin component Chp1 are components of the RITS (RNA-induced initiation of transcriptional gene silencing) complex, and the association of RITS with centromeres is linked to Dicer activity. In turn, centromeric binding of RITS promotes Clr4-mediated methylation of histone H3 lysine 9 (K9), recruitment of Swi6, and formation of heterochromatin. Similar to centromeres, the mating type locus (Mat) is coated in K9-methylated histone H3 and is bound by Swi6. Here we report that Chp1 associates with the mating type locus and telomeres and that Chp1 localization to heterochromatin depends on its chromodomain and the C-terminal domain of the protein. Another protein component of the RITS complex, Tas3, also binds to Mat and telomeres. Tas3 interacts with Chp1 through the C-terminal domain of Chp1, and this interaction is necessary for Tas3 stability. Interestingly, in cells lacking the Argonaute (Ago1) protein component of the RITS complex, or lacking Dicer (and hence siRNAs), Chp1 and Tas3 can still bind to noncentromeric loci, although their association with centromeres is lost. Thus, Chp1 and Tas3 exist as an Ago1-independent subcomplex that associates with noncentromeric heterochromatin independently of the RNAi pathway.

Heterochromatin, once thought to be inert compact chromatin, is now recognized as a dynamic structure capable of performing diverse roles within eukaryotic cells. Functions of heterochromatin include providing a platform for assembly of cohesin for maintenance of sister chromatid cohesion, for regulating gene transcription, and even for eliminating germ line-specific DNA sequences from the somatic nucleus during ciliate development (reviewed in reference 9).

In the fission yeast Schizosaccharomyces pombe, heterochromatin assembles at the mating type locus, centromeres, and telomeres (1). The chromodomain protein Swi6, the fission yeast homolog of heterochromatin protein 1 (HP1), localizes to and is required for maintenance of the repressed nature of all sites of heterochromatin (2, 11). The localization of Swi6 to these sequences is dependent on the activity of the Clr4 histone H3 K9-methyltransferase [the homolog of Su(var)39 enzymes] (5, 12) and is lost in cells where lysine 9 methylation is blocked by mutation (25).

Other components required for the establishment and maintenance of heterochromatin at all these loci are not yet resolved. At centromeres, heterochromatin maintenance and establishment additionally requires components of the RNA interference (RNAi) apparatus, which in fission yeast include a single Argonaute protein (Ago1) and a single Dicer enzyme (Dcr1) (30, 40, 41). Centromeric double-stranded transcripts are processed by Dicer, which generates short interfering centromeric RNAs (siRNAs) (31) that then somehow direct the complex to the centromere, via either siRNA-DNA or siRNA-nascent RNA interactions, most likely following their association with the Argonaute PAZ domain-containing protein, Ago1. This process is required for recruitment of the K9-histone H3 methyltransferase Clr4 to the locus (41), and this K9 H3 methylation then attracts additional K9-MeH3 binding chromodomain proteins, which contribute to the repressive architecture of centromeric heterochromatin (15).

We have previously demonstrated that another chromodomain protein, Chp1, is also essential for the formation of centromeric heterochromatin (28, 29). Recently, Chp1 has been shown to be a component of the RITS (RNA-induced initiation of transcriptional gene silencing) complex, which contains centromeric siRNAs, Ago1, Chp1, and a previously uncharacterized protein, Tas3 (39). RITS localization to centromeric sequences is required for the recruitment of Clr4 and Dicer activity and, hence, siRNA production is required for the association of the RITS complex with centromeres (39).

Despite their importance in the formation and maintenance of centromeric heterochromatin, deletions of components of the RNAi machinery have little impact on the maintenance of silent heterochromatin at the other well-characterized heterochromatic locus in fission yeast, the mating type region (mat2/3) (20). Recently, however, it has been demonstrated that multiple mechanisms ensure the formation and maintenance of heterochromatin at mat2/3. Therefore, loss of one mode of heterochromatin formation can be compensated for by redundancy within the system (20, 21, 37). The silent mat2/3 locus encompasses a 4.3-kb region of DNA (cenH) that is almost identical to the sequence found at the outer repeats of the centromere (17). Like the outer repeats, this cenH region is assembled into heterochromatin through an RNAi-dependent pathway (20). However, proximal to the mat3 locus, heterochromatin assembly occurs independent of the RNAi pathway as, for example, Atf1/Pcr1 transcription factors can directly recruit Clr6 histone deacetylase and Clr4 methyltransferase to these mat2/3 unique sequences (see Fig. 1 and 9, below) (21, 22).

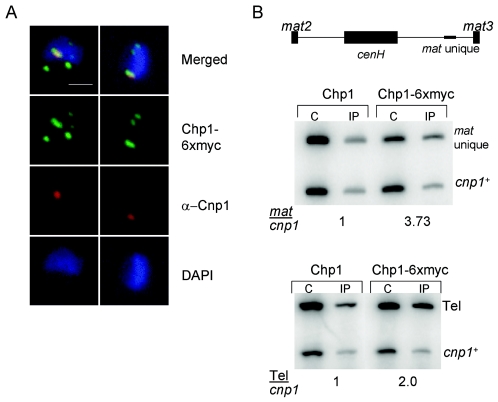

FIG. 1.

Chp1 associates with both noncentromeric heterochromatin and centromeres. (A) Immunofluorescence pictures showing the localization of Chp1-6xmyc (green) and Cnp1 (red) proteins in interphase nuclei. Cnp1 associates only with kinetochores, which are clustered. The colocalized spot of Chp1 staining represents Chp1 association with centromeric sequences, and it represents the largest spot of Chp1 staining. Bar, 1 μm. (B) ChIP analysis of anti-myc-immunoprecipitated chromatin from cells expressing chp1+ and chp1-6xmyc+. C, crude; IP, immunoprecipitate; mat unique, sequence that is unique to the mat2/3 locus; tel, telomeric sequence; cnp1, euchromatic control locus. Numbers reflect enrichment of mat unique sequences over the cnp1 control, or tel sequences over the cnp1 control, in the IP samples relative to the crude.

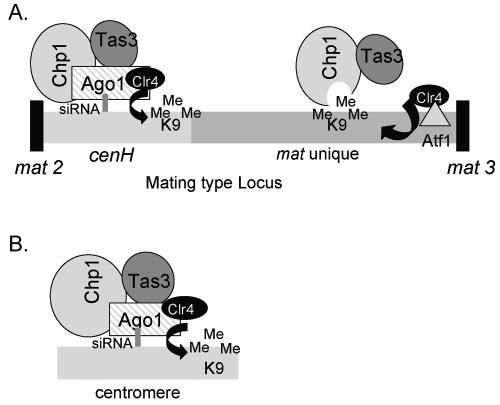

FIG. 9.

Proposed model for Chp1 complexes found at the mating type locus and centromere. (A) Chp1 associates with the mat2/3 locus through two independent pathways. At cenH sequences, Chp1 is recruited in an RNAi-dependent fashion as a component of the RITS complex, and at the mat3 proximal region Chp1 and Tas3 associate with sequences unique to the mating type independently of the RNAi apparatus. Atf1/Pcr1 transcription factors bind recognition sites proximal to the mat3 locus and directly recruit Clr4 methyltransferase activity to sequences that are unique to mat2/3, independently of the RNAi pathway (21). Chp1, in complex with Tas3, binds this K9-methylated histone H3. RNAi-independent recruitment of Chp1 and Tas3 to mat2/3 unique sequences does not appear to influence either the establishment or maintenance of silencing, suggesting that the Chp1-Tas3 complex alone is not competent to recruit Clr4. (B) In contrast, the RNAi-dependent assembly of the RITS complex at cenH or centromeric sequences promotes recruitment of Clr4 to these sequences and is important for establishment of silencing.

Here, we report that Chp1 associates with mat2/3 locus-specific sequences and telomeres in addition to sequences from the outer repeats of the centromere. We show that Chp1's chromodomain and its C-terminal domain are required for association of Chp1 with chromatin and that Chp1 directly binds to and stabilizes Tas3 through the agency of its C-terminal domain. Strikingly, although interaction with Ago1 and siRNAs are required for Chp1 to bind centromeres, Chp1 recruitment to other heterochromatic loci occurs independent of the RNAi pathway. Nonetheless, the RNAi-independent recruitment of Chp1 to unique sequences at the mat2/3 locus does not contribute to either the establishment or maintenance of silencing in this region. In contrast, Chp1 in the context of the RITS complex appears essential for the establishment of heterochromatin at cenH sequences within mat2/3 that exhibit high homology to centromeres.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Media and chemicals.

Fission yeast were maintained on rich medium (YES), unless nutritional selection was required for phenotypic analysis or to select progeny from genetic crosses or for maintenance of the LEU2 marked plasmid (pREP81-3xHA series), for which cells were grown on Pombe minimal with glutamate (PMG) medium with appropriate supplements (26) (PMG is Edinburgh minimal medium with glutamate). All chemicals were purchased from Sigma unless otherwise indicated.

Strain generation.

Strains used in this study are listed in Table 1. The chp1Δ his3+, rik1Δ LEU2, and clr4Δ LEU2 deletion strains were previously described (12, 28, 29). ago1Δ ura4+ and tas3Δ ura4+ were generated by replacing the complete open reading frames (ORFs) with the ura4+ reporter gene, and dcr1Δ Kanr was generated by replacement of the dicer ORF with KanMX6 (4). chp1-6xmyc+ has been described previously (28). tas3+ was tagged at its C terminus with 13xmyc epitopes (4). Chp1-TAP was generated by C-terminal tagging of the Chp1 ORF with the tandem affinity purification tag (36). Strains were generated in a ura4D18, leu1-32, and his3D background and outcrossed three times after construction and prior to introduction of additional marked loci. The function of tagged proteins was tested by the introduction, by crossing, of a centromeric ura4+ marker gene [otr1R(Sph1)::ura4+] (2) and assessing silencing of the centromeric ura4+ transgene by a serial dilution assay of cells on PMG-URA and PMG plus 5-fluoroorotic acid (FOA) media. FOA is toxic to cells that express ura4+ (7).

TABLE 1.

Strains used in this study

| Strain | Genotype | Source |

|---|---|---|

| PY 74 | h+chp1+-6xmyc-LEU2 ade6-210 leu1-32 ura4DS/E | R. Allshire (FY 2961) |

| PY 114 | h+ade6-210 leu1-32 ura4DS/E arg3D his3D | R. Allshire (FY 4133) |

| PY 387 | h+ ΔCD-chp1-6xmyc-LEU2 ade6-210 leu1-32 ura4DS/E arg3D his3D | This study |

| PY 450 | h+ ΔRRM-chp1-6xmyc-LEU2 ade6-210 leu1-32 ura4DS/E arg3D his3D | This study |

| PY 225 | h chp1 Δhis3+ade6-210 leu1-32 ura4DS/E otr1R(Sph1)::ura4+ | This study |

| PY 396 | h+chp1+-6xmyc-LEU2 ade6-210 leu1-32 ura4DS/E otr1R(Sph1)::ura4+ | This study |

| PY 418 | h ΔCD-chp1-6xmyc-LEU2 ade6-210 leu1-32 ura4DS/E otr1R(Sph1)::ura4+ | This study |

| PY 453 | h ΔRRM-chp1-6xmyc-LEU2 ade6-210 leu1-32 ura4DS/E otr1R(Sph1)::ura4+ | This study |

| PY 238a | h rik1Δ::LEU2 chp1-6xmyc-LEU2 leu1-32 ura4 DS/E | This study |

| PY 862 | h+tas3+-13xmyc-KANr ade6-210 leu1-32 ura4DS/E | This study |

| PY 1119 | h+ago1 Δura4+chp1+-6xmyc-LEU2 ade6-210 leu1-32 ura4D18 | This study |

| PY 354a | h+dcr1Δ::KANR chp1+-6x myc-LEU2 ade6-210 leu1-32 uraD18 | This study |

| PY 1161 | h+ago1 Δura4+tas3+-13xmyc-KANr ade6-210 leu1-32 ura4D18 | This study |

| PY 890 | h+dcr1 ΔKANr tas3+-13xmyc-KANr ade6-210 leu1-32 ura4DS/E | This study |

| PY 950 | h tas3 Δura4+chp1+-6xmyc-LEU2 ade6-210 leu1-32 ura4D18 | This study |

| PY 887 | h chp1 Δhis3+tas3+-13xmyc-KANr ade6-210 leu1-32 ura4DS/E | This study |

| PY 906a | h+chp1+-TAP-KANr tas3+-13xmyc-KANr ade6-210 leu1-32 ura4-DS/E | This study |

| PY 974 | h ago1Δ::ura4+chp1+-TAP-KANr tas3-13xmyc-KANr ade6-210 leu1-32 ura4D18 | This study |

| PY 12 | h− | R. Allshire (R972) |

| PY 260 | h90 mat3-M(RV)::ade6+ade6DN/N leu1-32 ura4D18 | R. Allshire (FY 3248) |

| PY 261 | h90 chp1 Δ::ura4+mat3-M(RV)::ade6+ade6DN/N leu1-32 ura4D18 | This study |

| PY 1127 | h90 ago1 Δ::ura4+mat3-M(RV)::ade6+ade6DN/N leu1-32 ura4D18 | This study |

| PY 1138 | h90 ago1Δ::ura4+chp1Δ::ura4+mat3-M(RV)::ade6+ade6DN/N leu1-32 ura4D18 | This study |

| PY 1115 | h90 rik1ΔLEU2 mat3-M(RV)::ade6+ade6DN/N leu1-32 ura4D18 | This study |

| PY 1157 | h90 clr4Δ::LEU2 mat3-M(RV)::ade6+ade6DN/N leu1-32 ura4D18 | This study |

| PY 30 | h+ade6-210 leu1-32 ura4-DS/E otr1R (Sph1)::ura4+ | R. Allshire (FY 648) |

| PY 404 | h−ade6-210 leu1-32 ura4-DS/E otr1R (Sph1)::ura4+ | This study |

| PY 14 | h+ade6-210 leu1-32 ura4-DS/E TM-ura4+R.int | R. Allshire (FY 340) |

| PY 271 | h−dcr1Δ::KANr ade6-210 arg3D his3D leu1-32 ura4D18 | This study |

| PY 899 | h+ago1Δ::ura4+ade6-210 arg3D his3D leu1-32 ura4D18 | This study |

| PY 916 | h tas3Δ::ura4+ade6-210 arg3D his3D leu1-32 ura4D18 | This study |

| PY 860 | h tas3+-13xmyc-KANr otr1R (Sph1)::ura4+ade6-210 leu1-32 ura4-DS/E | This study |

| PY 732 | h chp1+-TAP-KANr otr1R (Sph1)::ura4+ade6-210 leu1-32 ura4-DS/E | This study |

| PY 282 | h−CDΔ::ura4+-chp1-6xmyc-LEU2 ade6-210 his3D arg3D leu1-32 ura4D18 | This study |

| PY 338a | h RRMΔ::ura4+-chp1-6x myc-LEU2 ade6-210 his3D arg3D leu1-32 ura4D18 | This study |

| PY 189 | h−chp1+-6xmyc-LEU2 ade6-210 his3D arg3D leu1-32 ura4D18 | This study |

Only the relevant genotype is shown for this strain.

ΔCD-chp1-6xmyc and ΔRRM-chp1-6xmyc were generated by removing amino acids 2 to 79 and 311 to 407 of chp1-6xmyc+, respectively. These deletions were performed using a two-stage transformation process. Initially, the chromodomain was replaced with the ura4+ marker gene by transforming Chp1-6xmyc cells (PY 189) by electroporation with a PCR product containing ura4+ flanked with ∼80 bases of homology to sequences flanking the chromodomain. ura4+ transformants were selected by growth of cells on medium lacking uracil, and cells in which the chromodomain of Chp1 had been replaced by ura4+ (CDΔ::ura4+chp1-6xmyc) were detected by PCR (PY 282). Removal of ura4+ and generation of CDΔchp1-6xmyc cells was achieved by retransformation with a second chimeric PCR product that only contained sequences that flank the chp1 chromodomain and selecting for growth of cells on medium containing 5-FOA. PCR and DNA sequencing were used to confirm the generation of ΔCDchp1-6xmyc cells after three outcrosses (PY 387). ΔRRMchp1-6xmyc cells were derived in a similar fashion (PY 338, giving rise to PY 450). Strains were crossed to introduce the centromeric ura4+ marker at otr1R(Sph1) and the ura4+ minigene (ura4 DS/E) at the endogenous ura4+ locus.

chp1Δ cells bearing the pREP81-3xHA vector series were generated by transformation of PY 225 with vector, and the episomal ARS plasmid was maintained under selection for leucine. Expression from the vector was maintained by growth of cells on medium lacking thiamine, as the hemagglutinin (HA)-tagged protein is under control of the weakest derivative of the no message in thiamine (nmt1) promoter (6).

DNA constructs.

Yeast two-hybrid vectors were generated by PCR amplification of the Chp1 ORF with primers bearing NcoI and BamHI sites, or of the Tas3 ORF with primers containing EcoRI and BamHI sites, digestion of the purified products, and cloning into NcoI/BamHI-digested pGBKT7 (Clontech) (Chp1) or EcoRI/BamHI-digested pGADT7 (Tas3). Truncated chp1 vectors were generated in a similar fashion, using primers that amplify DNA fragments encoding amino acids 1 to 409 and cloning into pGBKT7. A pGADT7-tas3 derivative construct was also generated by digesting pGADT7-tas3 with SacI (SacI cuts within tas3 and in the 3′ polylinker region of the vector) and religation. The resulting plasmid contained coding sequence for amino acids 1 to 282 of tas3.

The pREP81-3xHA construct for expression in fission yeast was generated by cloning of annealed oligonucleotides with NdeI- and SalI-compatible ends that encode a 3xHA epitope tag and an NcoI site into NdeI/SalI-digested pREP81 (6). Release of NcoI/BamHI fragments from the pGBKT7 series and insertion into the NcoI/BamHI sites of the pREP81-3xHA vector placed the Chp1 ORF in frame with the N-terminal 3xHA tag and allowed simple shuttling of two-hybrid vector inserts into the S. pombe expression vector. The integrity of cloned DNA was verified by sequence analysis.

Protein interaction assays. (i) Yeast two-hybrid.

All budding yeast manipulations were performed according to the Clontech matchmaker yeast two-hybrid manual. pGADT7 and pGBKT7 derivative plasmids were cotransformed into AH109 budding yeast. Cultures were grown overnight at 30°C in SD-L-T, diluted back to an optical density at 600 nm of 1, and serially diluted (1:10) in distilled water. These dilutions were spotted on SD-L-T, SD-L-T-H-A plus (2.5 to 10 mM) 3-amino-1,2,4 triazole (3-AT) and 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-α-d-galactopyranoside (X-α-Gal; Clontech). Plates were incubated for 4 days at 30 °C prior to being photographed.

(ii) Fission yeast.

A total of 1.3 × 109 cells of PY 862, PY 906, and PY 974 were washed in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and resuspended in 1 ml of extraction buffer (50 mM HEPES [pH 7.6], 300 mM KO-acetate, 10% glycerol, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM EGTA, 0.2% NP-40, 5 mM MgO-acetate, 1 mM dithiothreitol, 1 mM Na3VO4, 1 mM NaF, 1 mM benzamidine, and 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, with Complete [EDTA-free] protease inhibitors [Roche]) prior to grinding in liquid N2 with a pestle and mortar until >70% lysis was achieved (assessed by microscopic examination). Cell lysates were centrifuged for 25 min at 30,000 rpm at 4°C in a Beckman TLA 120-2 rotor. Twenty microliters of supernatant was retained on ice as input material, and 40 μl of immunoglobulin G (IgG)-Sepharose beads (Amersham Biosciences; preblocked with 30 μg of bovine serum albumin) was added to the remainder of supernatant and incubated with rotation for 1 h at 4°C. Beads were washed five times with 1 ml of 80% extraction buffer-20% radioimmunoprecipitation assay buffer prior to boiling in 2× sample buffer and loading onto 8% prosieve (FMC) sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) gels and electrophoresis. Separated proteins were transferred onto nitrocellulose, and the blot was blocked in 5% milk-PBS-0.2% Tween (PBST) prior to probing with a 1:200 dilution of anti-myc antibody (9E10; Santa Cruz) in PBST and detection of bound antibody with horseradish peroxidase-linked anti-mouse antibody, followed by enhanced chemiluminescence and exposure to film.

ChIP.

Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) on fixed chromatin by using anti-Myc antibody (9E10; Santa Cruz) was performed as previously described (28). mat unique primers 5′-GGCAATACAACTTTGGCGATCATTTAC-3′ and 5′-TGTTTAGCGCACTTTGATTTTCCAGTC-3′ or Tel-specific primers 5′-CGATGCTCTCGACAAAGCCGTTCT-3′ and 5′-CCATCTCAAACTTCTGTTCAACATT-3′ (33) were used in multiplex PCR with cnp1+ primers 5′-GCCTGGAGATCCTATTCCACGGCC-3′ and 5′-GAACGCTTCAGCCGCTTCCTGAAGAC-3′ under conditions of exponential amplification (26 cycles). [α-32P]dCTP was used to spike the PCR, and uptake of 32P into the PCR products was quantified by use of ImageQuant software after separation of PCR products on 4% polyacrylamide gels, drying of gels, and imaging on a Storm PhosphorImager (Molecular Dynamics Inc.). Relative IP values represent averages from at least two independent experiments.

Immunofluorescence.

Fission yeast were grown overnight at 25°C to 5 × 106/ml and fixed with freshly prepared formaldehyde (3.8%) for 25 min. Permeabilized cells (18) were incubated with the following mouse monoclonal antibodies: anti-myc (1/100 dilution of 9E10; Santa Cruz), anti-HA (1/500; 12CA5; Roche), 1/15 anti-TAT1 (gift from K. Gull [42]) or 1/500 sheep anti-Cnp1 (gift from R. Allshire [23]), and secondary antibodies were all used at 1/100 (Texas red-conjugated anti-sheep or fluorescein isothiocyanate-conjugated anti-mouse antibody; Jackson Immunologicals). 4′,6′-Diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) was used to identify nuclei. Cells were cytospun onto polylysine-coated slides and photographed using a Zeiss Axioskop II microscope fitted with a Ludl filter wheel and chroma filters and a Coolsnap HQ camera (Photometrics). All images were taken at maximum resolution, using a 100× objective, with 100-ms exposure for fluorescein isothiocyanate, 10 ms for DAPI, and 100 ms for Texas red, and using IPLab software (Scanalytics). Images were imported into Adobe Photoshop and saved in CMYK format as Tiff files at 300-pixels/in. resolution. No manipulation of images was performed.

Defects in chromosome segregation were assessed in cells that had been stained with anti-TAT1 antibody (42) to reveal tubulin and DAPI staining of nuclei. Cells which exhibited spindle lengths of greater than 5 μm were analyzed for the presence of lagging chromosomes on the spindle (11). On average, 100 mitotic cells were analyzed.

RNA analysis.

RNA was prepared from 20-ml cultures of yeast grown in YES at 32°C to 5 × 106 cells/ml. Strains bearing centromeric ura4+ insertions were grown at 25°C. cDNA was prepared by oligo(dT)-primed reverse transcription-PCR (RT-PCR), and competitive PCR of ura4+ and ura4DS/E was performed as described previously (13). ura4+ (U) levels were quantified relative to ura4-DS/E (L) and relative to wild-type strains. tas3-13xmyc+ transcript levels were measured using multiplex PCR with primers derived from cnp1+ (above) and tas3+ (5′-TCATTTTTCGTTTTTATGCTCTAAAATTGAAGCC-3′ and 5′-CAACCTTTGCCTGAGCAGCTTATG-3′) under exponential PCR conditions, and tas3-13xmyc+ transcript levels were normalized to cnp1+ transcript levels and quantified relative to wild-type strains.

Cell growth assays: serial dilution assay of cell growth of S. pombe.

Serial (1:5) dilutions of cells grown overnight in PMG-leucine medium at 25°C to 5 × 106 cells/ml and washed in PMG with no supplements were spotted onto PMG-leucine medium, PMG-leucine medium supplemented with 2 mg of FOA/ml, or PMG medium lacking both uracil and leucine. Cultures were grown for 5 days at 25°C. A total of 1.2 × 104 cells were contained in the first spot.

To assess the maintenance of silencing at the mat2/3 locus, serial (1:5) dilutions of cells grown overnight in YES medium at 25°C to 5 × 106 cells/ml and washed in PMG with no supplements were spotted onto PMG medium containing reduced adenine (10%) and incubated for 5 days at 25°C. A total of 1.2 × 104 cells were contained in the first spot.

TSA treatment.

Cells were grown to 5 × 106 cells/ml in YES medium at 32°C, prior to dilution to 5 × 103 cells/ml in YES containing 35 μg of trichostatin A (TSA; A.G. Scientific)/ml and growth for 10 generations at 32°C. Cells were then allowed to recover for an additional 10 generations in YES alone, prior to washing in PMG with no supplements, serial (1:5) dilution of cells, spotting onto PMG medium lacking adenine or with reduced adenine (10% adenine), and incubation at 25°C for 5 days. A total of 1.2 × 104 cells were contained within the first spot.

RESULTS

The Chp1 chromodomain protein localizes to sites of heterochromatin.

We predicted that the Chp1 chromodomain protein, like Swi6, would associate with all regions of heterochromatin in fission yeast. We assessed the cellular localization of Chp1 in strains carrying a chp1-6xmyc+ allele that resides at the endogenous chp1+ locus; these strains produce a fully functional Chp1 protein with a C-terminal myc tag that is the only source of Chp1 within these cells (28). If Chp1 only associates with centromeres, a single spot should be visible in interphase cells, when centromeres are clustered at the nuclear periphery (16). Using indirect immunofluorescence and anti-myc epitope antibodies, several punctate foci of Chp1-6xmyc (green) were seen within the nucleus (two to six spots) (Fig. 1A). The position of centromeres was visualized by costaining with an antibody directed against the fission yeast Cnp1 protein (red), a histone H3 variant that only associates with active centromeres and that marks the site of formation of the kinetochore (Fig. 1A) (35). The kinetochore and outer repeat domains of the centromere form slightly spatially distinct regions of chromatin (23); therefore, green (Chp1-6xmyc) spots showing some overlap with, or adjacent to, the kinetochore (red, Cnp1) staining reflect a centromeric association of Chp1. However, in every cell examined, Chp1 was present at several other foci in addition to the centromeres, a scenario reminiscent of the numbers and positions of Swi6-positive foci, and Swi6 is known to associate with all sites of heterochromatin within fission yeast (11).

To confirm that Chp1 indeed associates with sites of heterochromatin other than centromeres, we performed ChIP with cells expressing Chp1-6xmyc and probed the immunoprecipitates for other heterochromatic DNA sequences. The silent mating type locus (mat2/3) is enriched in lysine 9-methylated histone H3 chromatin between mat2 and mat3, and within this domain there is an extensive region of very high homology to sequences from the outer repeats of the centromere (the cenH [for centromere homology] region) (17). To determine whether Chp1 associates with sequences unique to the mating type locus, primers from sequences more than 800 bp distal of cenH were used for PCR amplification of ChIP material. These unique sequences (Mat unique) were enriched in the anti-myc immunoprecipitates of chp1-6xmyc+ strains relative to the euchromatic control (cnp1+), or to immunoprecipitates prepared from non-myc-tagged strains (Fig. 1B). Similarly, sequences from the telomeric region were enriched in the anti-myc immunoprecipitates of chp1-6xmyc+ strains (Fig. 1B, lower panel). Thus, Chp1 associates with unique sequences from the mat2/3 region, with telomeres, and with the outer repeat sequences of the centromere (28, 39), as recently suggested by others (27, 32).

The chromodomain, but not the RNA recognition motif (RRM), is required for Chp1 function.

To define regions of Chp1 necessary for its activity and localization, we tested whether the two recognizable domains, the chromodomain (amino acids 2 to 79) and a putative RRM (amino acids 311 to 407) are essential for Chp1 function (Fig. 2A). We constructed S. pombe strains in which either the RRM or the chromodomain was deleted from chp1-6xmyc+ (28). These deletions were performed using a two-stage transformation process, which relies on the high efficiency of homologous recombination in fission yeast. Initially the chromodomain was replaced with the ura4+ marker gene, and then removal of ura4+ and the generation of ΔCDchp1-6xmyc cells was achieved by retransformation with a chimeric PCR product containing only sequences that flank the chp1 chromodomain. A centromeric marker gene (cen::otr-ura4+) (2) was subsequently introduced into ΔCDchp1-6xmyc cells. ΔRRMchp1-6xmyc cells were derived in a similar fashion. Levels of the mutant Chp1 proteins expressed in these strains were similar to those present in wild-type Chp1-6xmyc yeast (Fig. 2B), indicating that the mutations do not alter the stability or expression of Chp1 in vivo.

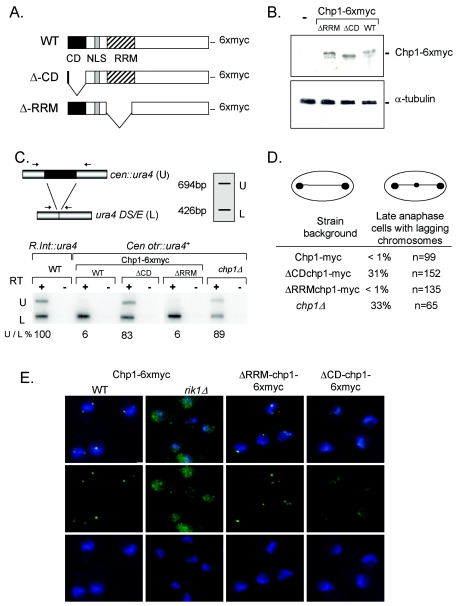

FIG. 2.

The chromodomain, but not the RRM of Chp1, contributes to its function. (A) Cartoon showing the domain structure of Chp1. CD, chromodomain; NLS, nuclear localization sequence. (B) Western analysis of steady-state levels of mutant chp1-6xmyc proteins. Whole-cell lysates were electrophoresed through an SDS-8% polyacrylamide gel, blotted, and probed with anti-myc antibody. The blot was stripped and reprobed with anti-TAT1 antibody to reveal α-tubulin levels as a loading control. (C) Strategy for quantitative RT-PCR analysis. Common primers amplified products of 694 bp (ura4+ reporter) and 426 bp for the ura4DS/E minigene located at the endogenous ura4+ locus. Oligo(dT)-primed cDNA wasprepared from RNA samples from strains bearing the centromeric ura4+ reporter (cen otr::ura4+) or the euchromatic ura4+ reporter (R.Int::ura4+) in the wild type and the indicated Chp1-6xmyc backgrounds. Expression of ura4+ (U) was compared with ura4-DS/E (L) expression in each strain by the quantitative PCR assay and compared with the fully expressed R.Int::ura4+ reporter and the silenced ura4+ inserted at cen1 otr. (D) Frequency of chromosome lagging in late-anaphase cells of wild-type (WT) and chp1 mutant strains grown at 25°C. Cells were fixed and stained with anti-TAT1 antibodies to reveal tubulin staining, and the DNA was stained with DAPI. The frequency of lagging chromosomes on late-anaphase (>5-μm-long) spindles was scored. (E) Immunofluorescent images showing localization of Chp1-6xmyc (green) staining in WT and rik1Δ cells and of the mutant ΔRRM-chp1-6xmyc and ΔCD-chp1-6xmyc proteins in otherwise-WT cells. DNA was revealed with DAPI (blue).

The integrity of centromeric heterochromatin was assessed in these chp1 mutant strains by measuring the silencing of a ura4+ (Fig. 2C, U) marker gene inserted within the outer repeat region of centromere 1 (cen otr::ura4+) and comparing its expression to that of the truncated ura4DS/E allele (Fig. 2C, L), present at the endogenous ura4 locus, by quantitative RT-PCR (13). Expression of a euchromatic insertion of ura4+ (R.Int::ura4+) was used to normalize expression of the DS/E allele and represented full expression (100%). Cells bearing a deletion of chp1 (chp1Δ) exhibited ∼80% derepression of transcription of the normally silent centromeric marker gene (cen::otr-ura4+), suggesting that outer repeat heterochromatin is largely disrupted in this mutant background (28, 29, 39). This loss of centromeric silencing was accompanied by a high incidence of cells displaying mitotic defects, as approximately 30% of late-anaphase cells exhibited lagging chromosomes (Fig. 2D) (10). Importantly, cells lacking only the Chp1 chromodomain (ΔCDchp1-6xmyc) behaved similar to the chp1 null strain, with elevated transcription of the centromeric marker gene (Fig. 2C) and numerous mitotic chromosome segregation defects (Fig. 2D). In contrast, cells lacking the RRM domain of Chp1 (ΔRRMchp1-6xmyc) exhibited no loss of Chp1 function.

To address whether the chromodomain or RRM might direct Chp1 localization (Fig. 2E), we compared the localization of Chp1 in these mutant strains to that of wild-type yeast. In wild-type cells, Chp1-6xmyc localizes to several spots at the nuclear periphery when assessed by indirect immunofluorescence with anti-myc antibodies (Fig. 1A and 2E). This pattern of Chp1-6xmyc localization is disrupted in a rik1Δ background, in which Chp1 chromatin association is lost (28) and where Chp1-6xmyc appears to accumulate in the nucleolus (Fig. 2E). ΔRRMchp1-6xmyc showed a normal pattern of localization, with several discrete spots at the nuclear periphery (Fig. 2E). In contrast, ΔCDchp1-6xmyc exhibited a diffuse faint spotty staining pattern throughout the nucleoplasm and was not associated with chromatin (Fig. 2E). Thus, the chromodomain, but not the RRM, is essential for Chp1 localization to all sites of heterochromatin and for normal Chp1 function at centromeric sequences.

The C-terminal domain of Chp1 is also essential for Chp1 function.

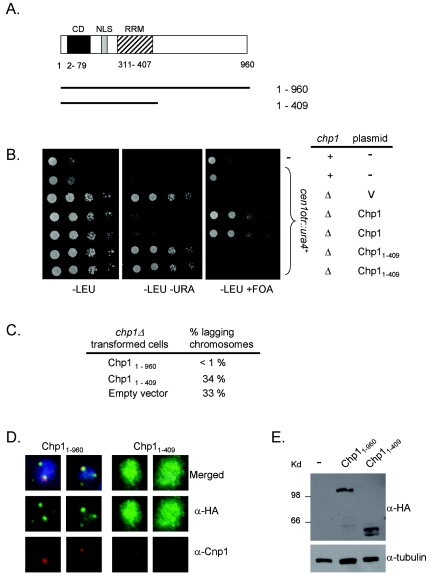

While these findings established that the chromodomain of Chp1 is necessary for targeting Chp1 to chromatin, it was unclear whether it was alone sufficient to direct Chp1 function and localization. To answer this question, we transformed chp1-null cells with plasmids encoding an N-terminally 3xHA epitope-tagged version of full-length or C-terminally truncated Chp1 (Fig. 3A). A plasmid encoding full- length Chp1 (pREP81-3xHA-Chp1) fully complemented the chp1Δ phenotype, as it reestablished silencing of a centromeric marker gene (conferring growth on FOA medium, which is toxic to ura4+-expressing cells) (Fig. 3B), accurate segregation of chromosomes (Fig. 3C), and proper targeting of 3xHA-Chp1 to typical spots at the nuclear periphery (Fig. 3D, left panel). Using this plasmid-based system, we then asked if sequences C-terminal to the RRM of Chp1 are important for Chp1 function. In contrast to the plasmid bearing full-length Chp1, expression of residues 1 to 409 of Chp1 (3xHA-chp11-409) completely failed to complement chp1Δ function. These cells exhibited high levels of chromosome segregation defects (Fig. 3C) and defects in centromeric silencing (Fig. 3B). Consistent with this result, immunolocalization of 3xHA-chp11-409 with anti-HA antibody revealed that the truncated protein was diffusely localized throughout the chromatin and nucleolus (Fig. 3D). Staining was not observed in all cells, and the high levels of immunofluorescence in others may have been caused by differential plasmid accumulation. Steady-state levels of the full-length and truncated Chp1 proteins were similar within the cell population (Fig. 3E). Therefore, the C-terminal domain of Chp1 is required for heterochromatin localization and function of Chp1. However, in the absence of its chromodomain, expression of the C terminus of Chp1 is not sufficient to drive heterochromatin localization or function of Chp1 (Fig. 3); thus, both the chromodomain and the C-terminal domain are essential for Chp1 localization and function.

FIG. 3.

The C terminus of Chp1 is also important for function. (A) Cartoon representing the regions of Chp1 inserted within the 3xHA N-terminal tagging vector (pREP81-3xHA) that were transformed into chp1Δ cells. Numbers represent amino acids. (B) Comparative growth assay of serially diluted strains bearing the centromeric cen otr::ura4+ reporter gene and assessed for growth on PMG-leucine (-LEU), PMG medium lacking leucine and uracil (-LEU -URA), or PMG medium lacking leucine but supplemented with 5-FOA (-LEU +FOA), which is toxic to ura4+ cells. Cells were wild type for chp1+ or had chp1 deleted (Δ) and were transformed with empty vector (pREP81-3xHA) or with plasmid encoding full-length or C-terminally truncated Chp1. The LEU2 marked plasmid was maintained under selection for leucine. (C) Defects in chromosome segregation were scored by counting the frequency of lagging chromosomes. chp1Δ cells bearing pREP81-3xHA derivatives were fixed and stained with DAPI and anti-TAT1 antibodies (tubulin), and the frequency of cells exhibiting lagging chromosomes on late-anaphase spindles of >5 μmin length was scored. (D) Immunofluorescence images of chp1Δ cells transformed with pREP81-3xHA-Chp1 (left) or pREP81-3xHA-chp11-409 (right) plasmids. Cells were stained with anti-HA monoclonal antibody (green) and anti-Cnp1 antibody (red), and DNA was revealed with DAPI (blue). (E) Western analysis of steady-state levels of Chp1 proteins expressed from the pREP81-3xHA plasmid in chp1Δ cells. The blot was stained with monoclonal anti-HA antibody, stripped, and reprobed with anti-TAT1 antibody to reveal tubulin as the loading control.

Tas3 colocalizes with Chp1, and Tas3 and Chp1 associate with mat2/3 and telomeres independently of Ago1 and siRNAs.

Chp1 was recently identified as a component of the RITS complex that associates with the outer repeat sequences at centromeres (28, 39). However, Chp1 is also localized to other sites of heterochromatin (Fig. 1) (27, 32). If Chp1 were exclusively associated with the RITS complex, other components of this complex should colocalize with Chp1 at other sites of heterochromatin. To test this hypothesis, endogenous Tas3 protein was tagged with a C-terminal 13xmyc epitope tag, and the localization of this fully functional protein (data not shown) was assessed. Tas3-13xmyc-expressing cells were costained with anti-myc epitope antibody and with antibody directed against Cnp1 to visualize the centromeres. Similar to Chp1, Tas3-13xmyc was localized to several punctate foci, with usually only one spot corresponding to the clustered centromeres (Fig. 4A) (27).

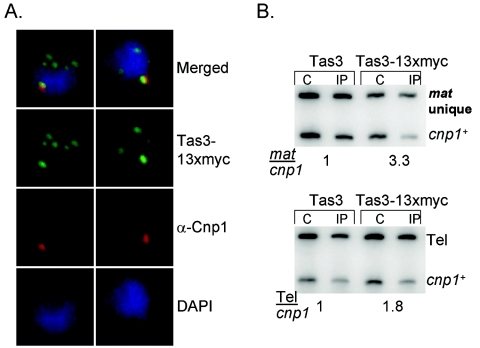

FIG. 4.

Tas3 localizes to both noncentromeric heterochromatin and centromeres. (A) Immunofluorescence pictures of cells expressing fully functional Tas3-13xmyc and stained with anti-myc (green) to reveal Tas3 localization and anti-Cnp1 (red) to localize centromeres. DNA was stained with DAPI (blue). (B) ChIP of lysates prepared from cells expressing tas3+ or tas3-13xmyc+. C, crude; IP, anti-myc immunoprecipitate; mat unique, sequence that is unique to mat2/3 locus; tel, telomeric sequence; cnp1, euchromatic control locus. Numbers reflect enrichment of mat unique sequences over the cnp1 control or tel sequences over the cnp1 control in the IP samples relative to the crude.

To confirm that Tas3-13xmyc associates with the mating type locus and telomeres in addition to its known association with the outer repeats of the centromere (27, 39), ChIP experiments were performed. Anti-myc immunoprecipitates of Tas3-13xmyc-expressing cells revealed a clear enrichment of the unique mating type sequences and telomeric sequences (Fig. 4B), whereas chromatin prepared from control cells lacking myc-tagged protein showed no enrichment of these heterochromatic loci compared to the control euchromatic cnp1+ locus. Thus, Tas3-13xmyc and Chp1-6xmyc colocalize to the mat2/3 locus, to telomeres, and to centromeres and possibly associate with all sites of heterochromatin.

Since reagents allowing for a direct evaluation of the association of Ago with Chp1 and Tas3 are not available, we addressed what effect loss of Ago1 had on the localization of Tas3 and Chp1 (Fig. 5A and B, middle panels). As expected (39), in ago1Δ cells there is a loss of centromere-associated Chp1 and Tas3, as revealed by loss of costaining of Chp1-6xmyc (Fig. 5A) and Tas3-13xmyc (Fig. 5B) with Cnp1-stained centromeres. Surprisingly, however, other foci of Chp1-6xmyc and Tas3-13xmyc persisted in ago1Δ cells. Similar results were obtained in cells from which Dicer (dcr1Δ) was deleted (Fig. 5A and B, right panels). Thus, in either the absence of Ago1 or of siRNAs, Tas3 and Chp1 association with centromeres is lost, but Tas3 and Chp1 appear to still bind other sites of heterochromatin.

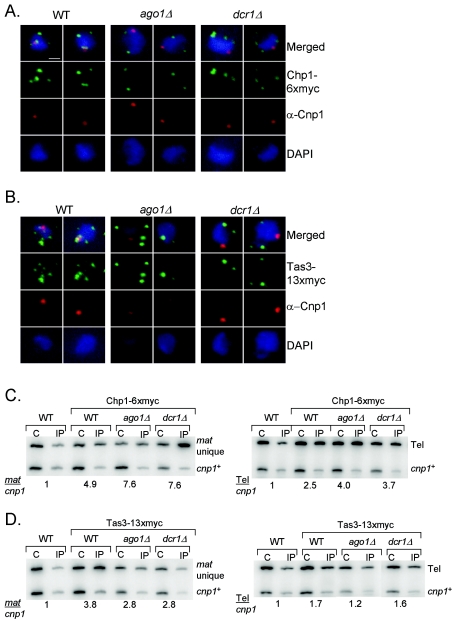

FIG. 5.

The association of Tas3 and Chp1 with noncentromeric heterochromatin is independent of Ago1 and Dcr1. (A) Immunofluorescent images of interphase cells expressing Chp1-6xmyc and stained with anti-myc antibodies (green) and anti-Cnp1 antibodies (red) to reveal localization of Chp1-6xmyc and centromeres, respectively. The middle panel shows localization in ago1Δ cells, and the right panel showslocalization in dcr1Δ cells. DAPI (blue) reveals DNA. Bar, 1 μm. (B) Immunofluorescent images of cells expressing Tas3-13xmyc and stained as for panel A. The middle panel is staining of ago1Δ cells, and the right panel shows cells lacking dcr1+. (C) Upper: ChIP of cells expressing chp1+ or chp1-6xmyc+ in wild-type (WT), ago1Δ, and dcr1Δ backgrounds and probed for association with sequences unique to the mat2/3 locus (mat unique) relative to a euchromatic control (cnp1). Lower: Tas3-13xmyc association with the mat2/3 locus probed by ChIP in WT, ago1Δ, and dcr1Δ cells. C, crude chromatin; IP, anti-myc-immunoprecipitated samples; mat unique, sequences unique to mat2/3; cnp1, euchromatic control. Numbers reflect enrichment of mat unique sequences over the cnp1 control in the IP samples relative to the crude. (D) As for panel C, except that ChIPs were probed for telomeric sequences (tel) and numbers reflect relative enrichment of tel sequences over the cnp1 control in the IP samples relative to the crude.

To confirm that the remaining foci of Chp1 and Tas3 staining in the ago1Δ and dcr1Δ backgrounds reflected the maintenance of association of these proteins with other sites of heterochromatin, we performed ChIPs. Indeed, the unique sequences from mat2/3 and telomeric DNA sequences remained clearly enriched in anti-myc-immunoprecipitated material from ago1Δ or dcr1Δ strains expressing either Chp1-6xmyc or Tas3-13xmyc (Fig. 5C and D), whereas their association with centromeric heterochromatin was lost (Fig. 5A and B) (39). Therefore, two pools of Chp1 and Tas3 are present within fission yeast: one that is recruited to centromeres in an Ago1- and siRNA-dependent fashion, and a second that associates with noncentromeric heterochromatin independently of the RNAi pathway.

We also assessed the localization of Chp1-6xmyc and Tas3-13xmyc in cells lacking tas3 and chp1, respectively (Fig. 6A). In cells with tas3 deleted, Chp1 was delocalized, with a cloud of small foci of staining that mainly accumulated over the nucleolus (Fig. 6A); therefore, in addition to the known requirement of Tas3 for Chp1 localization to centromeres, Tas3 is also required for localization of Chp1 to all other sites of heterochromatin. Strikingly, Tas3-13xmyc staining was completely absent in cells in which chp1 was deleted (Fig. 6A). To address whether this was due to a loss of Tas3 protein in chp1Δ cells, we determined the steady-state levels of the Tas3-13xmyc protein in various deletion backgrounds. In accordance with the immunolocalization data, we found that Tas3-13xmyc protein was essentially lost in chp1Δ cells, whereas it was present at normal levels in the ago1Δ cells (Fig. 6B). Chp1-6xmyc levels were unaffected by deletion of tas3+ or of ago1+.

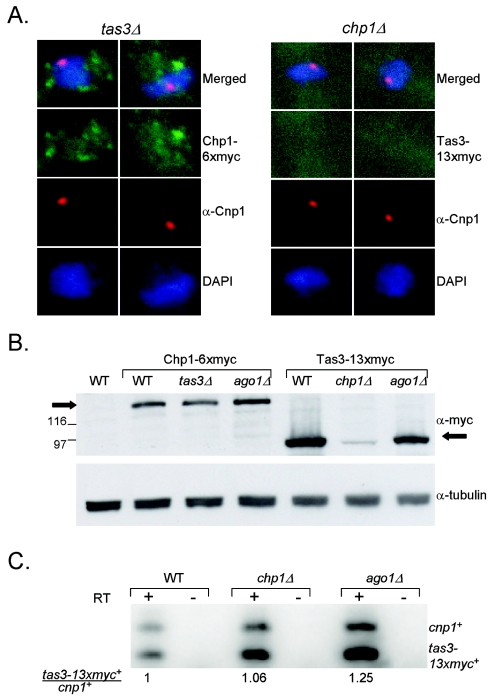

FIG. 6.

Localization of Chp1 and Tas3 is codependent, and Tas3 protein levels are dependent on Chp1. (A) Immunofluorescent images of cells expressing Chp1-6xmyc in a tas3Δ background and of Tas3-13xmyc in a chp1Δ background. Cells were stained with anti-myc antibodies (green) and anti-Cnp1 antibodies to reveal localization of centromeres. DNA was stained with DAPI (blue). (B) Western blot analysis of steady-state levels of Chp1-6xmyc and Tas3-13xmyc in wild-type (WT) and mutant backgrounds. Blot was probed with anti-myc monoclonal antibody, stripped, and reprobed with anti-TAT1 to reveal tubulin as a loading control. (C) Transcript analysis of chp1-6xmyc+ and tas3-13xmyc+ transcripts in WT and mutant strains. cDNA was prepared from RNA extracted from logarithmically growing cells and assessed for either chp1-6xmyc+ or tas3-13xmyc+ transcript levels in multiplex PCR along with primers that amplify the control cnp1+ transcript, under linear PCR conditions.

To address whether loss of Tas3-13xmyc protein in chp1Δ cells was due to suppression of tas3-13xmyc+ transcription, we performed quantitative RT-PCR using RNA prepared from wild-type, chp1Δ, and ago1Δ backgrounds. Deletion of chp1+ had no effect on tas3-13xmyc+ transcript levels (Fig. 6C); therefore, the loss of Tas3 protein in chp1 null cells is a posttranscriptional effect.

Tas3 and Chp1 interact independently of Ago1.

The RNAi-independent association of Chp1 and Tas3 with noncentromeric heterochromatin suggests that Chp1 and Tas3 may exist as a complex that acts independently of Ago1 and siRNAs. To test this notion, yeast two-hybrid analyses using a Gal4-DNA binding domain (GBD) fusion of Chp1 and GAL4 activation domain (GAD) fusion of Tas3 were performed in AH109 budding yeast bearing integrated GAL4 site-dependent reporters. All three reporter genes were strongly induced, allowing growth of the yeast on medium lacking adenine and histidine and blue coloration of the colonies from metabolism of X-α-Gal, included in the selective medium (Fig. 7A). The induction of HIS3 expression was sufficient to allow growth of the yeast on media containing up to 10 mM 3-AT (data not shown), which is a competitive inhibitor of the His3 protein. Specificity of the reporter gene induction was confirmed by the absence of growth on selective media when either Chp1-GBD or Tas3-GAD protein fusions were tested in combination with the empty GAD or GBD vectors, respectively. It is unlikely that endogenous budding yeast proteins facilitate the interaction of Tas3 and Chp1, as budding yeast lack all known components of the RNAi pathway. Finally, interaction mapping studies demonstrated that the C-terminal portion of Chp1 (residues 407 to 960), which is essential for Chp1 function (Fig. 3), was sufficient for interaction with Tas3, whereas the N-terminal domain of Tas3 (residues 1 to 282) was sufficient for interaction with Chp1 (Fig. 7A).

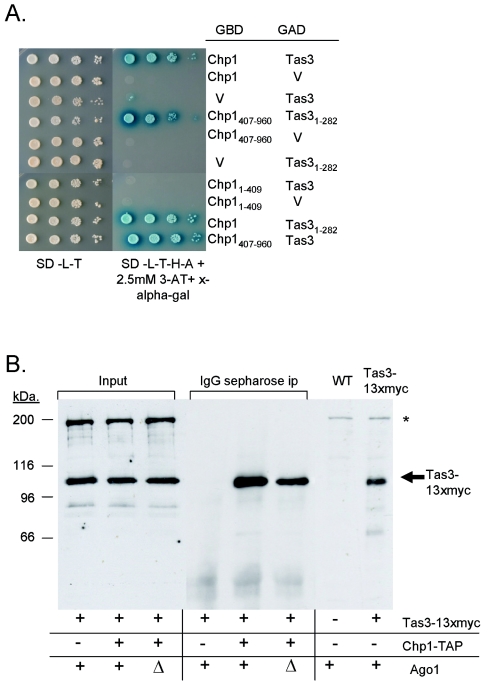

FIG. 7.

Tas3 and Chp1 directly interact, and this interaction occurs independently of Ago1. (A) Two-hybrid analysis demonstrated interaction between Tas3 and Chp1. Vectors expressing GBD fusions of full-length or truncated Chp1 proteins or empty vector (V) were cotransformed into AH109 budding yeast with vectors expressing GAD fusions of full-length or truncated Tas3 proteins or empty vector. Growth of strains was compared (left panel) by a serial dilution spotting assay onto synthetic medium lacking leucine and tryptophan (SD-L-T) to maintain plasmids. The interaction of GBD and GAD fusion proteins was assessed by serial dilution spotting assays onto media lacking leucine and tryptophan (to maintain plasmid selection) and lacking histidine and adenine and containing X-α-Gal to monitor GAL4 site-dependent activation of integrated reporter genes that drive HIS3, ADE2, and MEL1 expression (SD-L-T-A-H + x-alpha gal). A 2.5 mM concentration of 3-AT was also included as a competitive inhibitor of the His3 protein. (B) Tas3-13xmyc coimmunoprecipitates with TAP-tagged Chp1 from both ago1+ and ago1Δ fission yeast. Whole-cell extracts were prepared from fission yeast expressing Tas3-13xmyc and either wild-type (WT) Chp1 or Chp1-TAP. IgG-Sepharose was used to immunoprecipitate the protein A moiety of the TAP tag. Washed immunoprecipitates were resolved by SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis, and blotted proteins were probed with anti-myc antibodies for the presence of Tas3-13xmyc. Lanes 1 to 3 show equivalent levels of Tas3-13xmyc in input material, and lane 5 shows that Tas3-13xmyc is specifically immunoprecipitated by Chp1-TAP, as no Tas3-13xmyc was evident in IPs from chp1+ cells (lane 4). Immunoprecipitates of ago1Δ strains demonstrate maintenance of the Tas3-13xmyc and Chp1-TAP interaction (lane 6). Lanes 7 and 8 show whole-cell extracts prepared from tas3+ and tas3-13xmyc+ strains to confirm the identity of the Tas3-13xmyc signal. *, nonspecific band that was detected by anti-myc antibody in crude extracts.

To confirm that the Chp1-Tas3 interaction indeed occurred in fission yeast and that this interaction was independent of Ago1, we performed coimmunoprecipitation experiments in wild-type and ago1Δ strains. Protein extracts were prepared from strains expressing both a functional C-terminal TAP-tagged genomic Chp1 fusion protein (Chp1-TAP) and Tas3-13xmyc. IgG-Sepharose was used to immunoprecipitate Chp1-TAP complexes, and immunoprecipitated material was probed for Tas3-13xmyc by blotting with anti-myc antibodies (Fig. 7B). Immunoprecipitation of lysate from cells expressing Tas3-13xmyc and nontagged Chp1 was performed as a control for specificity of the IgG-Sepharose pull down (Fig. 7B, lane 4). Chp1-TAP coimmunoprecipitated with Tas3-13xmyc (lane 5), and this interaction was also evident in extracts from ago1Δ cells (lane 6). Therefore, Tas3 and Chp1 are also present in an RNAi-independent complex in S. pombe and bind noncentromeric heterochromatin regions in the absence of Ago1.

Chp1 is required for establishment, and to a lesser extent maintenance, of mat2/3 silencing.

To assess the role of Chp1 at the mat2/3 locus, we first examined the impact of deletion of chp1+on silencing of the ade6+ marker gene inserted close to mat3 (at the EcoRV site) (Fig. 8A) (37). The efficiency of maintenance of silencing was determined by plating serial dilutions of cells onto plates limiting in adenine. Wild-type cells efficiently silence mat3::ade6+ expression, giving rise to red colonies on plates limiting for adenine (37), whereas yeast bearing deletions in clr4+ or rik1+ alleviate silencing at the mat2/3 locus (14) and produce white colonies. Nonetheless, deletion of chp1+ or ago1+ only slightly alleviated silencing (20, 38), as revealed by the presence of pink colonies compared with the red, fully repressed colonies (Fig. 8A).

FIG. 8.

Chp1 and Ago1 are equally important for establishment and maintenance of silencing at mat2/3. (A) chp1Δ and ago1Δ similarly influence the maintenance of mat2/3 silencing. A comparative growth assay was performed of serially diluted strains bearing the ade6+ reporter gene inserted at the mat3 locus (mat3-M::ade6+) and the ade6 minigene ade6 DN/N at the endogenous ade6+ locus, and strains were assessed for growth on PMG medium with supplements, but only 10% adenine, to visualize expression of the ade6+ reporter. A strain bearing ade6+ at the normal locus was included for comparison. WT, wild-type. (B) Chpl and Ago1 contribute equally to the establishment of silencing at the mating type locus. A comparative growth assay of serially diluted strains bearing the mat3-M::ade6+ reporter was performed on PMG plus 10% adenine medium and medium lacking adenine (No Ade). Strains were grown for 10 generations in 35 μg of TSA/ml and allowed to recover for 10 generations before plating to assess the effect of deletion of chp1+ or ago1+ or the combined chp1 ago1 deletion on the efficiency of establishment of silencing at the mating type locus. chp1Δ and ago1Δ cells showed a similar defect in establishment of silencing, suggesting that the RNAi-independent association of Chp1 with mat2/3 plays no role in the establishment of silencing.

To address the consequences of Chp1 deletion on the initiation of silencing at the mat2/3 locus, cells of various backgrounds and bearing the mat3::ade6+ marker were grown for 10 generations in the presence of TSA, which promotes histone hyperacetylation and disrupts heterochromatin (13, 43). Cells were then washed and grown in the absence of TSA for an additional 10 generations, before plating on medium with no adenine (Fig. 8B, left panel) or in limiting adenine (Fig. 8B, right panel). If heterochromatin were efficiently established, cells should form red colonies on limiting adenine medium, as seen for the wild-type cells treated with TSA (20), whereas if heterochromatin were inefficiently established, white or pink colonies should result from a failure to establish silencing of the locus. TSA-treated Chp1-deficient cells showed clear reductions in their ability to establish heterochromatin on mat2/3 sequences, with pale pink colonies formed on low-adenine plates, and more growth of chp1Δ cells bearing the mat3::ade6+ marker on medium lacking adenine was observed than in similarly treated chp1+ cells. Similar findings were evident in ago1Δ cells, and no further enhancement of growth on media lacking adenine was observed for ago1Δ chp1Δ cells; therefore, deletion of chp1+ has no additional impact on the assembly of heterochromatin at mat2/3 sequences compared to the removal of Ago1 alone. We conclude that the RNAi-independent association of Chp1 with mat2/3 has little consequence on the establishment of heterochromatin on these sequences.

DISCUSSION

The studies presented herein demonstrate that two components of the RITS complex, Chp1 and Tas3, can exist as an independent complex that targets noncentromeric heterochromatin independently of Ago1 and siRNAs. It has previously been reported that Chp1 exists in the RITS complex with Tas3, Ago1, and siRNAs and that in the absence of siRNAs (in a dcr1 deletion background), interactions between Tas3, Chp1, and Ago1 are maintained but they fail to associate with centromeric heterochromatin (39). Our demonstration of an Ago1-independent interaction between Tas3 and Chp1, and the Ago1- and siRNA-independent localization of this Tas3 and Chp1 complex to the mating type locus and telomeres, suggests new views regarding the roles and regulation of components of the RITS complex in establishing and/or maintaining heterochromatin.

Firstly, our observation that the RNAi-independent form of the Chp1-Tas3 complex localizes to both telomeres and the mat2/3 locus suggests that this complex plays a role in regulating heterochromatin at these sites. The mat2/3 locus includes the 4.3-kb cenH region and here, like at centromeres, the establishment of heterochromatin is dependent upon the RNAi pathway (20). However, the establishment of heterochromatin at mat3 proximal sequences (Mat unique) is RNAi independent and results from direct recruitment of histone-modifying enzymes by the Atf1/Pcr1 transcription factors (Fig. 9) (20, 21). Importantly, our finding that Chp1 binds to telomeres and to the mating type locus independent of the RNAi apparatus suggests that Chp1 can be recruited to genomic regions that are methylated on lysine 9 of histone H3 through RNAi-independent mechanisms. The mating type locus therefore provided a useful system to probe the function of Chp1 independent of the RNAi pathway and allowed us to address whether localization of Chp1 (and Tas3) to these sequences is directly responsible for silencing.

Previous work testing the role of Chp1 in silencing of the mat2/3 locus showed a minor role for Chp1 in the maintenance of silencing at mating type sequences (38) and, similarly, a minor role for components of the RNAi pathway (20). By use of an ago1Δ strain, we confirmed that deletion of RNAi pathway components has little effect on the maintenance of silencing of the mat2/3 locus (Fig. 8A) (20). Moreover, there were no significant differences in the maintenance of silencing in ago1Δ, chp1Δ, and ago1Δchp1Δ strains, and in these cells treated with TSA there were no significant differences in the establishment of silencing at the mating type locus (Fig. 8B). Therefore, Chp1 that binds independently of the RNAi pathway to unique sequences at mat2/3 plays no additional role in either the maintenance or establishment of heterochromatin at the mating type locus, in contrast to the essential RNAi-dependent role of Chp1 in the maintenance and establishment of heterochromatin and silencing at cenH and centromeres.

In principle our studies agree with those of others that have examined the role of Chp1 in the establishment of heterochromatin at multiple loci and which suggest that Chp1 recruitment promotes silencing at mating type locus sequences inserted upstream of the ura4+ marker gene at a euchromatic site (32). Wild-type cells efficiently nucleate heterochromatin at this ectopic location and silence ura4+ expression, but chp1 null or RNAi mutants fail to establish heterochromatin on these sequences (3, 20, 32). The sequences used in this assay were, however, derived from the cenH region within mat2/3 that shares 96% identity with centromeric sequences (3, 17). Our demonstration that the RNAi-independent binding of Tas3 and Chp1 to unique sequences at mat2/3 does not support silencing, whereas association of RITS with centromeric or cenH sequences is required for establishment of silencing (20, 29, 32, 39, 40), suggests that the distinguishing factors, Ago1 and siRNAs, are key to understanding the mechanism by which RITS promotes silencing of centromeric sequences, through recruitment of the Clr4 histone methyltransferase.

The data that we have presented complement a very recent publication by Noma et al. (27). In accordance with our data, they demonstrated association of RITS components with heterochromatic loci and Tas3 and Chp1 association with the mat2/3 locus in the absence of dicer. In addition, they identified cenH transcripts which are elevated in swi6 and dcr1 mutant backgrounds and further increased in the compound mutant background in which mat2/3 silencing is lost. They attributed the maintenance of silencing in the single mutant backgrounds to posttranscriptional, as well as transcriptional, silencing mediated by RITS tethered in cis at the mat2/3 locus (27). An alternative explanation might be that only when both RNAi-dependent and RNAi-independent silencing are lost do transcript levels rise sufficiently at mat2/3 to cause loss of heterochromatin formation.

In agreement with our model for K9-MeH3-mediated recruitment of Chp1 and Tas3 to mat unique sequences, Noma et al. demonstrated a correlation between the binding activity of Chp1 and Tas3 with the extent of K9-MeH3 at mat2/3 in clr4 mutant backgrounds. Chp1 copurified with siRNAs from clr4 mutant strains in which Chp1 and Tas3 maintained some association with mat2/3, but not from clr4 deletion strains in which histone H3 K9 methylation and Chp1 chromatin association were lost. These and other data derived from use of a mutant Chp1 that does not bind chromatin led to the conclusion that RITS association with chromatin is required for efficient processing of transcripts at heterochromatic loci and for generation and recruitment of siRNAs into the RITS complex (27). However, our study suggests that RITS localization is not the sole determinant of silencing efficiency at mat2/3, as the silencing defect in strains lacking multiple RITS components is not as profound as in strains lacking clr4+ (Fig. 8 and data not shown). Deletion of clr4+ perturbs both the RNAi-dependent and RNAi-independent heterochromatin formation at mat2/3, whereas loss of RITS components affects only RNAi-dependent silencing.

Whether the Chp1-Tas3 complex plays a passive or active role in heterochromatin regulation remains to be resolved, as although deletion of chp1+ has little consequence on the RNAi-independent formation of heterochromatin at the mat2/3 locus, it is feasible that it plays an important role in the establishment and/or maintenance of heterochromatin at other sites, for example, at the telomeres or rRNA gene repeats. Specifically, deletion of chp1+ perturbs silencing of a polymerase II-transcribed marker inserted within the rRNA locus and, although chp1+ loss or mutation of the RNAi pathway does not influence the maintenance of silencing at telomeric sequences (19, 38), a role for Chp1 in the formation of heterochromatin at telomeric sequences has recently been described (32).

A second possibility is that the Chp1-Tas3 complex represents an intermediate complex that is stockpiled at noncentromeric heterochromatic loci and is thus readily available for interaction with siRNA-loaded Ago1. After binding, this forms a functional RITS complex, which can then be recruited to centromeric DNA sequences by siRNA-mediated targeting. At the mat2/3 locus, the close proximity of the cenH sequences linked in cis to the store of Tas3-Chp1 complex suggests an appealing model for a rapid switch of the Tas3-Chp1 complex to silencing competent RITS on binding to Ago1 and recruitment, perhaps by spreading, onto cenH sequences. By extrapolation, the accumulation of the Chp1-Tas3 complex at telomeres may provide a source for loading of RITS onto centromeric sequences during the switch in chromosomal positioning between mitotic and meiotic cell cycles. During mitotic interphase the centromeres are clustered at the spindle pole body, and at the onset of meiotic prophase their position at the spindle pole is taken by telomeres and the centromeres dissociate (8). After meiotic prophase, the chromosomes resume the mitotic interphase configuration, with centromeres associated with the spindle pole. Depending on the timing of centromeric transcription, and how siRNA formation is regulated during meiosis, such chromosomal movements may facilitate transfer of RITS to centromeric sequences.

Our model predicts that Ago1 is not an obligate component of the Chp1 and Tas3 complex and, recently, it has been found that Ago1, but not Tas3 or Chp1, is required for posttranscriptional gene silencing (34). Our data support a model whereby Ago1 can associate with the nuclear Chp1-Tas3 complex to form RITS and direct transcriptional silencing, or it can associate with cytoplasmic factors to drive posttranscriptional gene silencing. If Ago1 were limiting within the cell, such flexibility would allow for a rapid response to changes in signaling pathways.

The mechanism by which Chp1 binds to either centromeres or other heterochromatic loci is poorly understood. The chromodomain of Chp1 is not required for the association of Tas3 with Chp1, yet it is essential for localization of Chp1 to heterochromatin. The chromodomain of Chp1 binds to K9-MeH3 peptides in vitro (29), and Chp1 localization is dependent on the Clr4 histone methyltransferase (28). This, together with the colocalization of Chp1 with Swi6 at sites of heterochromatin (this study and references 27, 28, and 32), implies that the K9-MeH3 interaction mediated by Chp1's chromodomain contributes to its association with heterochromatin. However, as recently suggested (24), the interaction of the chromodomain with K9-MeH3 in native chromatin may not be of high enough affinity to tether proteins to heterochromatin, and now clearly in the case of Chp1, interaction with Tas3 also plays a crucial role in Chp1's ability to associate with heterochromatin.

Acknowledgments

We thank Kathy Gould for the TAP tagging and pREP81 vectors, Jurg Bahler for the 13xmyc cassette, Robin Allshire for strains and the anti-Cnp1 antibody, and Keith Gull for the anti-TAT1 antibody. We gratefully acknowledge the support and advice of Paul Brindle, John Cleveland, Gerry Zambetti, Jim Ihle, and Evan Parganas and thank John Cleveland, Paul Brindle, Paul Mead, Katsumi Kitagawa, Pascal Bernard, and Jill Lahti for critical reading of the manuscript. J.P. also thanks Paul Perry for advice on setting up the microscopy system and Tom Lawrence and Wendy Bickmore for support and encouragement.

This work was supported in part by Cancer Center Support Grant Developmental funds 2 P30 CA 21765-25 and 2 P30 CA 21765-26 and the American Lebanese Syrian Associated Charities of St. Jude Children's Research Hospital.

REFERENCES

- 1.Allshire, R. C. 1995. Elements of chromosome structure and function in fission yeast. Semin. Cell Biol. 6:55-64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Allshire, R. C., E. R. Nimmo, K. Ekwall, J. P. Javerzat, and G. Cranston. 1995. Mutations derepressing silent centromeric domains in fission yeast disrupt chromosome segregation. Genes Dev. 9:218-233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ayoub, N., I. Goldshmidt, R. Lyakhovetsky, and A. Cohen. 2000. A fission yeast repression element cooperates with centromere-like sequences and defines a mat silent domain boundary. Genetics 156:983-994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bahler, J., J. Q. Wu, M. S. Longtine, N. G. Shah, A. McKenzie III, A. B. Steever, A. Wach, P. Philippsen, and J. R. Pringle. 1998. Heterologous modules for efficient and versatile PCR-based gene targeting in Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Yeast 14:943-951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bannister, A. J., P. Zegerman, J. F. Partridge, E. A. Miska, J. O. Thomas, R. C. Allshire, and T. Kouzarides. 2001. Selective recognition of methylated lysine 9 on histone H3 by the HP1 chromodomain. Nature 410:120-124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Basi, G., E. Schmid, and K. Maundrell. 1993. TATA box mutations in the Schizosaccharomyces pombe nmt1 promoter affect transcription efficiency but not the transcription start point or thiamine repressibility. Gene 123:131-136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Boeke, J. D., J. Trueheart, G. Natsoulis, and G. R. Fink. 1987. 5-Fluoroorotic acid as a selective agent in yeast molecular genetics. Methods Enzymol. 154:164-175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chikashige, Y., D. Q. Ding, H. Funabiki, T. Haraguchi, S. Mashiko, M. Yanagida, and Y. Hiraoka. 1994. Telomere-led premeiotic chromosome movement in fission yeast. Science 264:270-273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dernburg, A. F., and G. H. Karpen. 2002. A chromosome RNAissance. Cell 111:159-162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Doe, C. L., G. Wang, C. Chow, M. D. Fricker, P. B. Singh, and E. J. Mellor. 1998. The fission yeast chromo domain encoding gene chp1+ is required for chromosome segregation and shows a genetic interaction with alpha-tubulin. Nucleic Acids Res. 26:4222-4229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ekwall, K., J. P. Javerzat, A. Lorentz, H. Schmidt, G. Cranston, and R. Allshire. 1995. The chromodomain protein Swi6: a key component at fission yeast centromeres. Science 269:1429-1431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ekwall, K., E. R. Nimmo, J. P. Javerzat, B. Borgstrom, R. Egel, G. Cranston, and R. Allshire. 1996. Mutations in the fission yeast silencing factors clr4+ and rik1+ disrupt the localisation of the chromodomain protein Swi6p and impair centromere function. J. Cell Sci. 109(Pt. 11):2637-2648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ekwall, K., T. Olsson, B. M. Turner, G. Cranston, and R. C. Allshire. 1997. Transient inhibition of histone deacetylation alters the structural and functional imprint at fission yeast centromeres. Cell 91:1021-1032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ekwall, K., and T. Ruusala. 1994. Mutations in rik1, clr2, clr3 and clr4 genes asymmetrically derepress the silent mating-type loci in fission yeast. Genetics 136:53-64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Elgin, S. C., and S. I. Grewal. 2003. Heterochromatin: silence is golden. Curr. Biol. 13:R895-R898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Funabiki, H., I. Hagan, S. Uzawa, and M. Yanagida. 1993. Cell cycle-dependent specific positioning and clustering of centromeres and telomeres in fission yeast. J. Cell Biol. 121:961-976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Grewal, S. I., and A. J. Klar. 1997. A recombinationally repressed region between mat2 and mat3 loci shares homology to centromeric repeats and regulates directionality of mating-type switching in fission yeast. Genetics 146:1221-1238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hagan, I. M., and J. S. Hyams. 1988. The use of cell division cycle mutants to investigate the control of microtubule distribution in the fission yeast Schizosaccharomyces pombe. J. Cell Sci. 89(Pt. 3):343-357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hall, I. M., K. Noma, and S. I. Grewal. 2003. RNA interference machinery regulates chromosome dynamics during mitosis and meiosis in fission yeast. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 100:193-198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hall, I. M., G. D. Shankaranarayana, K. Noma, N. Ayoub, A. Cohen, and S. I. Grewal. 2002. Establishment and maintenance of a heterochromatin domain. Science 297:2232-2237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jia, S., K. Noma, and S. I. Grewal. 2004. RNAi-independent heterochromatin nucleation by the stress-activated ATF/CREB family proteins. Science 304:1971-1976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kim, H. S., E. S. Choi, J. A. Shin, Y. K. Jang, and S. D. Park. 2004. Regulation of Swi6/HP1-dependent heterochromatin assembly by cooperation of components of the mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway and a histone deacetylase Clr6. J. Biol. Chem. 279:42850-42859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kniola, B., E. O'Toole, J. R. McIntosh, B. Mellone, R. Allshire, S. Mengarelli, K. Hultenby, and K. Ekwall. 2001. The domain structure of centromeres is conserved from fission yeast to humans. Mol. Biol. Cell 12:2767-2775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Meehan, R. R., C. F. Kao, and S. Pennings. 2003. HP1 binding to native chromatin in vitro is determined by the hinge region and not by the chromodomain. EMBO J. 22:3164-3174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mellone, B. G., L. Ball, N. Suka, M. R. Grunstein, J. F. Partridge, and R. C. Allshire. 2003. Centromere silencing and function in fission yeast is governed by the amino terminus of histone H3. Curr. Biol. 13:1748-1757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Moreno, S., A. Klar, and P. Nurse. 1991. Molecular genetic analysis of fission yeast Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Methods Enzymol. 194:795-823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Noma, K. I., T. Sugiyama, H. Cam, A. Verdel, M. Zofall, S. Jia, D. Moazed, and S. I. Grewal. 2004. RITS acts in cis to promote RNA interference-mediated transcriptional and post-transcriptional silencing. Nat. Genet. 36:1174-1180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Partridge, J. F., B. Borgstrom, and R. C. Allshire. 2000. Distinct protein interaction domains and protein spreading in a complex centromere. Genes Dev. 14:783-791. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Partridge, J. F., K. S. Scott, A. J. Bannister, T. Kouzarides, and R. C. Allshire. 2002. cis-acting DNA from fission yeast centromeres mediates histone H3 methylation and recruitment of silencing factors and cohesin to an ectopic site. Curr. Biol. 12:1652-1660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Provost, P., R. A. Silverstein, D. Dishart, J. Walfridsson, I. Djupedal, B. Kniola, A. Wright, B. Samuelsson, O. Radmark, and K. Ekwall. 2002. Dicer is required for chromosome segregation and gene silencing in fission yeast cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99:16648-16653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Reinhart, B. J., and D. P. Bartel. 2002. Small RNAs correspond to centromere heterochromatic repeats. Science 297:1831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sadaie, M., T. Iida, T. Urano, and J. Nakayama. 2004. A chromodomain protein, Chp1, is required for the establishment of heterochromatin in fission yeast. EMBO J. 23:3825-3835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sadaie, M., T. Naito, and F. Ishikawa. 2003. Stable inheritance of telomere chromatin structure and function in the absence of telomeric repeats. Genes Dev. 17:2271-2282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sigova, A., N. Rhind, and P. D. Zamore. 2004. A single Argonaute protein mediates both transcriptional and posttranscriptional silencing in Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Genes Dev. 18:2359-2367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Takahashi, K., E. S. Chen, and M. Yanagida. 2000. Requirement of Mis6 centromere connector for localizing a CENP-A-like protein in fission yeast. Science 288:2215-2219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tasto, J. J., R. H. Carnahan, W. H. McDonald, and K. L. Gould. 2001. Vectors and gene targeting modules for tandem affinity purification in Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Yeast 18:657-662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Thon, G., K. P. Bjerling, and I. S. Nielsen. 1999. Localization and properties of a silencing element near the mat3-M mating-type cassette of Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Genetics 151:945-963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Thon, G., and J. Verhein-Hansen. 2000. Four chromo-domain proteins of Schizosaccharomyces pombe differentially repress transcription at various chromosomal locations. Genetics 155:551-568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Verdel, A., S. Jia, S. Gerber, T. Sugiyama, S. Gygi, S. I. Grewal, and D. Moazed. 2004. RNAi-mediated targeting of heterochromatin by the RITS complex. Science 303:672-676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Volpe, T., V. Schramke, G. L. Hamilton, S. A. White, G. Teng, R. A. Martienssen, and R. C. Allshire. 2003. RNA interference is required for normal centromere function in fission yeast. Chromosome Res. 11:137-146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Volpe, T. A., C. Kidner, I. M. Hall, G. Teng, S. I. Grewal, and R. A. Martienssen. 2002. Regulation of heterochromatic silencing and histone H3 lysine-9 methylation by RNAi. Science 297:1833-1837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Woods, A., T. Sherwin, R. Sasse, T. H. MacRae, A. J. Baines, and K. Gull. 1989. Definition of individual components within the cytoskeleton of Trypanosoma brucei by a library of monoclonal antibodies. J. Cell Sci. 93(Pt. 3):491-500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yoshida, M., M. Kijima, M. Akita, and T. Beppu. 1990. Potent and specific inhibition of mammalian histone deacetylase both in vivo and in vitro by trichostatin A. J. Biol. Chem. 265:17174-17179. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]