ABSTRACT

Background

Due to limited inclusion of patients on kidney replacement therapy (KRT) in clinical trials, the effectiveness of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) therapies in this population remains unclear. We sought to address this by comparing the effectiveness of sotrovimab against molnupiravir, two commonly used treatments for non-hospitalised KRT patients with COVID-19 in the UK.

Methods

With the approval of National Health Service England, we used routine clinical data from 24 million patients in England within the OpenSAFELY-TPP platform linked to the UK Renal Registry (UKRR) to identify patients on KRT. A Cox proportional hazards model was used to estimate hazard ratios (HRs) of sotrovimab versus molnupiravir with regards to COVID-19-related hospitalisations or deaths in the subsequent 28 days. We also conducted a complementary analysis using data from the Scottish Renal Registry (SRR).

Results

Among the 2367 kidney patients treated with sotrovimab (n = 1852) or molnupiravir (n = 515) between 16 December 2021 and 1 August 2022 in England, 38 cases (1.6%) of COVID-19-related hospitalisations/deaths were observed. Sotrovimab was associated with substantially lower outcome risk than molnupiravir {adjusted HR 0.35 [95% confidence interval (CI) 0.17–0.71]; P = .004}, with results remaining robust in multiple sensitivity analyses. In the SRR cohort, sotrovimab showed a trend toward lower outcome risk than molnupiravir [HR 0.39 (95% CI 0.13–1.21); P = .106]. In both datasets, sotrovimab had no evidence of an association with other hospitalisation/death compared with molnupiravir (HRs ranged from 0.73 to 1.29; P > .05).

Conclusions

In routine care of non-hospitalised patients with COVID-19 on KRT, sotrovimab was associated with a lower risk of severe COVID-19 outcomes compared with molnupiravir during Omicron waves.

Keywords: cohort studies, comparative effectiveness research, COVID-19, renal replacement therapy

INTRODUCTION

People receiving kidney replacement therapy (KRT) remain vulnerable to severe outcomes from COVID-19 [1]. This is multifactorial due to effects from both impaired kidney function and its causes and treatments for kidney disease impacting underlying vulnerability to severe respiratory disease and vaccine response [2]. These biological factors intersect with reduced ability to shield due to needing to attend hospital for specialist care, particularly those people treated with in-centre haemodialysis (IC-HD) [3]. While vaccination has greatly improved the relative risk of severe outcomes for many of the originally identified vulnerable groups, such as older individuals [4], it has offered modest gains for people receiving KRT [5].

For both transplant and dialysis populations, there is substantial evidence of attenuated responses to vaccinations against pre-pandemic pathogens [6, 7]. People receiving KRT were excluded from phase 3 severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) vaccine trials [8–10], but in vitro studies of immunogenicity of AZD1222 (Oxford–AstraZeneca) and BNT162b2 (Pfizer–BioNTech) showed reduced responses compared with people without kidney disease [11–14]. Therefore, despite vaccination, people receiving KRT remain at risk of severe illness from SARS-CoV-2 infection and are a population likely to have the most benefit from outpatient antiviral treatments. However, use of these medications in the KRT population is not straightforward. Paxlovid (nirmatrelvir/ritonavir), an oral antiviral, is contraindicated in the UK marketing authorisation for patients with severe kidney impairment or those receiving immunosuppressive drugs for kidney transplantation [15].

Randomised trials of sotrovimab, a neutralising monoclonal antibody (nMAb), had limited inclusion of patients receiving KRT [16]. There is also limited evidence for molnupiravir, an oral antiviral, among people receiving KRT [17, 18]. Nonetheless, in both England and Scotland, antiviral medications were pragmatically recommended for people receiving KRT. These were deployed via dedicated treatment centres [COVID Medicine Delivery Units (CMDUs)] in England and administered centrally via individual National Health Service (NHS) health boards in Scotland, both established in December 2021 to provide timely antiviral treatment of vulnerable patients in the community.

Due to the contraindications of Paxlovid, sotrovimab and molnupiravir are still the two commonly used treatment options for the KRT population in the UK. Therefore, it remains critical to understand the comparative effectiveness of sotrovimab and molnupiravir in preventing severe outcomes from COVID-19 in non-hospitalised patients receiving KRT. This is also especially relevant in the context of the ongoing global debate regarding the efficacy of sotrovimab. Although the World Health Organization and US Food and Drug Administration have recommended against the use of sotrovimab based on in vitro data [19, 20], the latest guidelines in the UK and several European countries still recommend its use [21].

In this study, we used two sources of high-quality routinely collected clinical data in England, the UK Renal Registry (UKRR) linked to the OpenSAFELY platform, to enable comprehensive clinical data and accurate identification of people receiving KRT to bridge this gap in knowledge for COVID-19 treatments during the Omicron era. In addition, to ensure generalisability of our results, we conducted a complementary analysis using data from the Scottish Renal Registry (SRR).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study population

OpenSAFELY-UKRR cohort

We included infected adults (≥18 years old) within the OpenSAFELY-TPP platform who were receiving KRT and had non-hospitalised treatment records for either sotrovimab or molnupiravir between 16 December 2021 and 1 August 2022, covering the Omicron waves where BA.1, BA.2 and BA.4/BA.5 were the predominant subvariants in England [22]. According to national guidance [15], these patients did not need hospitalisation for COVID-19 or new supplemental oxygen specifically for the management of COVID-19 symptoms when initiating the treatment. We focused on these two drugs because only a small number of infected patients on KRT were treated with Paxlovid [15], remdesivir or casirivimab/imdevimab. During the early part of the study (from 16 December 2021 to 10 February 2022) there was relative clinical equipoise between sotrovimab and molnupiravir, with either agent recommended for treatment of symptomatic high-risk patients in national guidance [23].

SRR cohort

All adults (≥18 years old) who were on KRT in Scotland who had a linked record for receiving either sotrovimab or molnupiravir between 21 December 2021 and 31 August 2022 were included.

Data sources

OpenSAFELY-UKRR cohort

The dataset analysed within OpenSAFELY-TPP is based on 24 million people currently registered with general practitioner (GP) surgeries using TPP SystmOne software. All data were linked, stored and analysed securely within the OpenSAFELY platform (https://opensafely.org/). Data were pseudonymised and included coded diagnoses, medications and physiological parameters. No free-text data are included. All code is shared openly for review and reuse under an MIT open license (https://github.com/opensafely/sotrovimab-and-molnupiravir). Detailed pseudonymised patient data are potentially re-identifiable and therefore not shared. Primary care records are securely linked to the UKRR database, Office for National Statistics (ONS) mortality database, in-patient hospital records via the Secondary Uses Service (SUS), national coronavirus testing records via the Second Generation Surveillance System (SGSS) and the COVID-19 therapeutics dataset, derived from Blueteq software that CMDUs use to notify NHS England of COVID-19 treatments.

The UKRR database contains data from patients under secondary renal care. In this study we restricted our population to those in the UKRR 2021 prevalence cohort (i.e. patients alive and on KRT in December 2021).

SRR cohort

The SRR is a national registry of all patients receiving KRT in Scotland. It collates data from all nine adult renal units in Scotland and 28 satellite HD units serving a population of 5.4 million with 100% unit and patient coverage. Data on SARS-CoV-2 testing were obtained from the Electronic Communication of Surveillance in Scotland. Information on hospital admissions was obtained from the Scottish Morbidity Record and Rapid Preliminary Inpatient Data and data on deaths were obtained from the National Records of Scotland. Vaccination data were obtained from the Turas Vaccination Management Tool, which holds all vaccination records in Scotland. Data on treatment with sotrovimab or molnupiravir were obtained from information provided by the health boards to Public Health Scotland, in addition to data obtained via the Hospital Electronic Prescribing and Medicines Administration in the boards where available.

Exposure

The exposure was treatment with sotrovimab or molnupiravir. In the OpenSAFELY-UKRR cohort, patients were excluded if they had treatment records of any other nMAbs or antivirals for COVID-19 before receiving sotrovimab or molnupiravir (n ≤ 5). Patients with treatment records of both sotrovimab and molnupiravir were censored at the start date of the second treatment (n = 8). In the SRR cohort, as the data linkage was only undertaken looking at sotrovimab or molnupiravir, we were unable to determine if any other antiviral treatments had been given prior to this.

Outcomes

The primary outcome was COVID-19-related hospitalisation or COVID-19-related death within 28 days after treatment initiation. COVID-19-related hospitalisation was defined as hospital admission with COVID-19 as the primary diagnosis in the OpenSAFELY-UKRR cohort and defined as emergency hospital admission with COVID-19 as the main condition in the SRR cohort. COVID-19-related death was defined as COVID-19 being the underlying/contributing cause of death on death certificates in both cohorts.

Secondary outcomes were 28-day all-cause hospital admission or death and 60-day COVID-19-related hospitalisation/death. In the OpenSAFELY-UKRR cohort, to exclude events where patients were admitted in order to receive sotrovimab or other planned/regular treatment (e.g. dialysis), we did not count admissions coded as such or day cases detected by the same admission and discharge dates as hospitalisation events (Supplementary Table S1). Similarly, in the SRR cohort, only emergency hospital admissions with the length of hospital stay >0 were counted as outcome events.

Statistical analyses

OpenSAFELY-UKRR cohort

Distributions of baseline characteristics were compared between the two treatment groups. Follow-up time of individual patients was calculated from the recorded treatment initiation date until the outcome event date, 28 days after treatment initiation, initiation of a second nMAb/antiviral treatment, death or patient deregistration date, whichever occurred first.

Risks of 28-day COVID-19-related hospitalisation/death were compared between the two groups using Cox proportional hazards models, with time since treatment as the time scale. The Cox models were stratified by NHS region to account for geographic heterogeneity in baseline hazards, with sequential adjustment for other baseline covariates. Model 1 was adjusted for age and sex; Model 2 additionally adjusted for high-risk cohort categories (solid cancer, haematological disease/stem cell transplant, immune-mediated inflammatory disorders or immunosuppression), KRT modality and years since KRT start date; Model 3 further adjusted for ethnicity, Index of Multiple Deprivation (IMD) quintiles, vaccination status and calendar date (with restricted cubic splines to account for non-linear effect); and Model 4 additionally adjusted for body mass index (BMI) category, diabetes, hypertension and chronic cardiac and respiratory diseases. Missing values of covariates were treated as separate categories. The proportional hazards assumption was tested based on the scaled Schoenfeld residuals.

As an alternative approach, we adopted the propensity score weighting (PSW) method to account for confounding bias. The covariates were balanced between the two drug groups through the average treatment effect (ATE) weighting scheme based on the estimated propensity scores. Balance check was conducted using standardised mean differences between groups (<0.10 as the indicator of well balanced). Robust variance estimators were used in the weighted Cox models.

Similar analytical procedures were used for secondary outcomes. In addition, we explored whether the following factors could modify the observed comparative effectiveness: KRT modality (dialysis or kidney transplantation), time period with different dominant variants (16 December 2021–15 February 2022 for BA.1, 16 February–31 May for BA.2 and 1 June–1 August for BA.4/BA.5) [22], BMI categories (≥30 versus <30 kg/m2), presence of diabetes, hypertension, chronic cardiac diseases or chronic respiratory diseases, days between testing positive and treatment initiation (<3 versus 3–5), age group (<60 versus ≥60 years), sex and ethnicity (White versus non-White).

Additional sensitivity analyses based on the stratified Cox models were conducted, including using complete case analysis or multiple imputation by chained equations to deal with missing values in covariates; using Cox models with calendar date as the underlying time scale to further account for temporal trends (and circulating variants); additionally adjusting for time between testing positive and treatment initiation, and time between last vaccination date and treatment initiation; additionally adjusting for rural–urban classification and other comorbidities and factors that might have influenced the clinician's choice of therapy through the patient's ability to travel to hospital for an infusion (learning disabilities, severe mental illness, care home residency or housebound status); using restricted cubic splines for age to further control for potential non-linear age effects; excluding patients with treatment records of both sotrovimab and molnupiravir or with treatment records of casirivimab/imdevimab, Paxlovid or remdesivir; excluding patients who did not have a positive SARS-CoV-2 test record before treatment or initiated treatment after 5 days since a positive SARS-CoV-2 test; creating a 1-day or 2-day lag in the follow-up start date to account for potential delays in drug administration; and conducting a cause-specific analysis for the 28-day COVID-19-related hospitalisation/death versus other hospitalisation/death.

SRR cohort

Similar statistical analyses were conducted in the SRR cohort, except where there was no relevant covariate information.

Exploratory analysis with untreated comparators in the OpenSAFELY-UKRR dataset

In addition to the comparative effectiveness analyses, following peer-review feedback we conducted an exploratory analysis to assess the effectiveness of sotrovimab and molnupiravir when compared with untreated COVID-19 patients on KRT. The comparator group was defined as patients in the UKRR 2021 prevalence cohort who had a COVID-19-positive test record between 16 December 2021 and 1 August 2022, not hospitalised on the date of a positive test and who did not receive any outpatient COVID-19 therapies in the following 28 days. In this analysis, the follow-up start date for both treated and untreated patients was the COVID-19-positive test date. Patients with a missing positive test date (or outside of the study period) were thus excluded from this exploratory analysis.

To account for immortal time bias (i.e. treated patients should not have outcome events between a positive test date and the treatment initiation date), we used a time-varying Cox model in which treated patients initially contributed person-time to the untreated group between positive test and treatment initiation and then contributed to the treated group after treatment initiation; untreated patients only contributed person-time to the untreated group after their positive test date. A robust variance estimator was used in this model. Similar covariate adjustment approaches were used as mentioned above.

RESULTS

OpenSAFELY-UKRR cohort

Patient characteristics

Between 16 December 2021 and 1 August 2022, a total of 2367 non-hospitalised COVID-19 patients on KRT were treated with sotrovimab (n = 1852) or molnupiravir (n = 515). The mean age of these patients was 55.9 years (SD 14.6), 43.5% were female, 85.4% being White and 92.6% having had three or more COVID-19 vaccinations. In the whole treated population, 69.6% were kidney transplant recipients and 30.4% were on dialysis. Among these, 81.8% of dialysis patients and 76.7% of transplant patients were treated with sotrovimab. Baseline characteristics were similar between the groups receiving different treatments (Table 1), but the sotrovimab group had a lower proportion of kidney transplant recipients and a higher proportion of patients with chronic cardiac disease. There were also some geographic variations in the prescription of these two drugs and greater use of molnupiravir earlier during the study period.

Table 1:

Baseline characteristics of patients on KRT receiving molnupiravir or sotrovimab.

| OpenSAFELY-UKRR cohort | SRR cohort | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristics | Molnupiravir group | Sotrovimab group | Total | Molnupiravir group | Sotrovimab group | Total |

| Patients, n | 515 | 1852 | 2367 | 270 | 723 | 993 |

| Age (years), mean (SD) | 55.5 (14.6) | 56.0 (14.6) | 55.9 (14.6) | 54.7 (12.7) | 58.4 (14.2) | 57.4 (13.9) |

| Female, n (%) | 217 (42.1) | 813 (43.9) | 1030 (43.5) | 113 (41.9) | 310 (42.9) | 423 (42.6) |

| White, n (%) | 452 (87.9) | 1567 (84.7) | 2019 (85.4) | |||

| Most deprived, n (%) | 75 (14.9) | 282 (15.7) | 357 (15.6) | 36 (13.3) | 195 (27.0) | 231 (23.3) |

| Region (NHS), n (%) | ||||||

| East | 144 (28.0) | 489 (26.4) | 633 (26.7) | |||

| London | 36 (7.0) | 148 (8.0) | 184 (7.8) | |||

| East Midlands | 35 (6.8) | 357 (19.3) | 392 (16.6) | |||

| West Midlands | 9 (1.8) | 58 (3.1) | 67 (2.8) | |||

| North East | 6 (1.2) | 67 (3.6) | 73 (3.1) | |||

| North West | 45 (8.7) | 183 (9.9) | 228 (9.6) | |||

| South East | 61 (11.8) | 92 (5.0) | 153 (6.5) | |||

| South West | 92 (17.9) | 294 (15.9) | 386 (16.3) | |||

| Yorkshire | 87 (16.9) | 164 (8.9) | 251 (10.6) | |||

| KRT modality, n (%) | ||||||

| Dialysis | 131 (25.4) | 588 (31.8) | 719 (30.4) | 21 (7.8) | 324 (44.8) | 345 (34.7) |

| Kidney transplant | 384 (74.6) | 1264 (68.3) | 1648 (69.6) | 249 (92.2) | 399 (55.2) | 648 (65.3) |

| Years since KRT start, median (IQR) | 7 (4–13) | 7 (4–12) | 7 (4–13) | 12 (4–18) | 9 (2–14) | 10 (3–15) |

| High-risk cohorts, n (%) | ||||||

| Down syndrome | ≤5 | ≤5 | ||||

| Solid cancer | 28 (5.4) | 61 (3.3) | 89 (3.8) | |||

| Haematological disease | 12 (2.3) | 61 (3.3) | 73 (3.1) | |||

| Liver disease | ≤5 | 29 (1.6) | ||||

| Immune-mediated inflammatory diseases | 222 (43.1) | 681 (36.8) | 903 (38.2) | |||

| Immunosuppression | 17 (3.3) | 57 (3.1) | 74 (3.1) | |||

| HIV/AIDS | ≤5 | 6 (0.3) | ||||

| Rare neurological disease | ≤5 | 6 (0.3) | ||||

| BMI (kg/m2), mean (SD) | 28.4 (6.1) | 28.3 (6.1) | 28.3 (6.1) | |||

| Comorbidities, n (%) | ||||||

| Diabetes | 189 (36.7) | 710 (38.3) | 899 (38.0) | |||

| Chronic cardiac disease | 111 (21.6) | 506 (27.3) | 617 (26.1) | |||

| Hypertension | 447 (86.8) | 1585 (85.6) | 2032 (85.9) | |||

| Chronic respiratory disease | 94 (18.3) | 365 (19.7) | 459 (19.4) | |||

| Vaccination status, n (%) | ||||||

| None | 9 (1.8) | 28 (1.5) | 37 (1.6) | 0 (0.0) | 16 (2.2) | 16 (1.6) |

| 1–2 | 31 (6.0) | 108 (5.8) | 139 (5.9) | 3 (1.1) | 46 (6.4) | 49 (4.9) |

| ≥3 | 475 (92.2) | 1716 (92.7) | 2191 (92.6) | 267 (98.9) | 661 (91.4) | 928 (93.5) |

| Days between test positive and treatment, median (IQR) | 2 (1–3) | 2 (1–3) | 2 (1–3) | 2 (1–2) | 2(1–3) | 2 (1–3) |

| Weeks between 16 December 2021 and treatment, median (IQR) | 12 (4–17) | 15 (8–22) | 14 (7–21) | 15 (8–26) | 13 (9–23) | 13 (9–24) |

| Primary renal diagnosis, n (%) | ||||||

| Diabetes | 34 (12.6) | 129 (17.8) | 163 (16.4) | |||

| Glomerulonephritis | 71 (26.3) | 164 (22.7) | 235 (23.7) | |||

| Interstitial | 113 (41.9) | 219 (30.3) | 332 (33.4) | |||

| Multisystem | 32 (11.9) | 115 (15.9) | 147 (14.8) | |||

| Unknown (including missing) | 20 (7.4) | 96 (13.3) | 116 (11.7) | |||

In the OpenSAFELY-UKRR cohort, KRT start time, IMD, BMI, ethnicity and positive test date had 617, 73, 181, ≤5 and 199 missing values, respectively. In the SRR cohort, 17 postcodes did not match to an SIMD category and 12 primary renal diagnosis codes within the unknown group were missing.

Comparative effectiveness for the outcome events

Among the 2367 kidney patients treated with sotrovimab or molnupiravir, 38 cases (1.6%) of COVID-19-related hospitalisations/deaths were observed during the 28 days of follow-up after treatment initiation, with 21 (1.1%) in the sotrovimab group and 17 (3.3%) in the molnupiravir group; the number of COVID-19-related deaths was five or fewer in both groups.

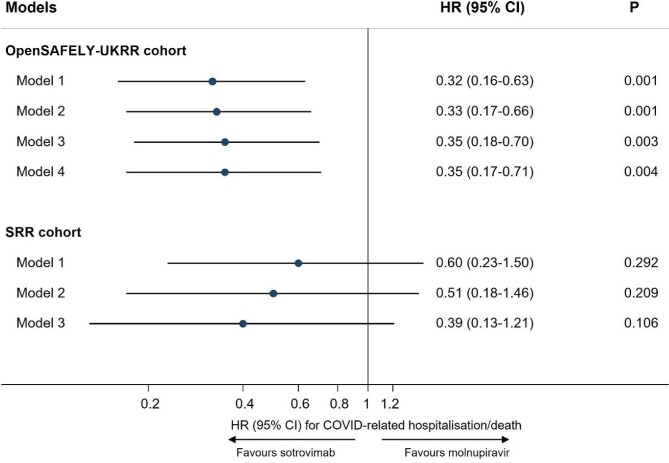

Results of stratified Cox regression showed that, after adjusting for multiple covariates, treatment with sotrovimab was associated with a substantially lower risk of 28-day COVID-19-related hospitalisation/death than treatment with molnupiravir [Model 4: HR 0.35 (95% CI 0.17–0.71); P = .004]. Consistent results favouring sotrovimab over molnupiravir were obtained from propensity score–weighted Cox models [Model 4: HR 0.39 (95% CI 0.19–0.80); P = .010], following confirmation of a successful balance of baseline covariates between groups in the weighted sample (Supplementary Table S2). The magnitude of HRs was stable during the sequential covariate adjustment process (ranging from 0.32 to 0.35 across different models; Fig. 1).

Figure 1:

Comparing risk of 28-day COVID-19-related hospitalisation/death between sotrovimab versus molnupiravir in two cohorts. In the OpenSAFELY-UKRR cohort, Model 1 adjusted for age and sex; Model 2 additionally adjusted for high-risk cohort categories, KRT modality and duration; Model 3 additionally adjusted for ethnicity, IMD quintiles, vaccination status, calendar date; and Model 4 additionally adjusted for BMI category, diabetes, hypertension, chronic cardiac and respiratory diseases. In the SRR cohort, Model 1 adjusted for age and sex; Model 2 additionally adjusted for modality, PRD group and KRT duration; Model 3 additionally adjusted for SIMD, vaccination status and calendar time.

For the secondary outcomes, the analysis of 60-day COVID-19-related events revealed similar results in favour of sotrovimab (HRs ranging from 0.33 to 0.36; P < .05). For all-cause hospitalisations/deaths, 163 cases (6.9%) were observed during the 28 days of follow-up after treatment initiation [117 (6.4%) in the sotrovimab group and 46 (9.0%) in the molnupiravir group]. Results of stratified Cox regression showed a lower risk in the sotrovimab group than in the molnupiravir group (HRs ranging from 0.60 to 0.65 in Models 1–4; P < .05; Table 2).

Table 2:

Comparing risks of non-COVID-specific outcomes between sotrovimab versus molnupiravir in two cohorts.

| OpenSAFELY-UKRR cohort | SRR cohort | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcomes | N/events | HR (95% CI) for sotrovimab (ref = molnupiravir) | P-value | N/events | HR (95% CI) for sotrovimab (ref = molnupiravir) | P-value |

| 28-day all-cause hospitalisation/death | 2350/163 | 993/75 | ||||

| Model 1 | 0.65 (0.46–0.92) | .016 | 1.04 (0.61–1.76) | .879 | ||

| Model 2 | 0.63 (0.44–0.89) | .010 | 0.80 (0.45–1.43) | .455 | ||

| Model 3 | 0.62 (0.43–0.89) | .009 | 0.71 (0.39–1.29) | .273 | ||

| Model 4 | 0.60 (0.41–0.85) | .004 | ||||

| 28-day other-cause hospitalisation/death | 2350/130 | 993/56 | ||||

| Model 1 | 0.85 (0.56–1.29) | .441 | 1.29 (0.68–2.40) | .426 | ||

| Model 2 | 0.79 (0.52–1.21) | .276 | 0.97 (0.47–1.95) | .934 | ||

| Model 3 | 0.76 (0.49–1.16) | .205 | 0.90 (0.44–1.84) | .776 | ||

| Model 4 | 0.73 (0.48–1.12) | .151 | ||||

In the OpenSAFELY-UKRR cohort, Model 1 adjusted for age and sex; Model 2 additionally adjusted for high-risk cohort categories, KRT modality and duration; Model 3 additionally adjusted for ethnicity, IMD quintiles, vaccination status, calendar date; and Model 4 additionally adjusted for BMI category, diabetes, hypertension, chronic cardiac and respiratory diseases. In the SRR cohort, Model 1 adjusted for age and sex; Model 2 additionally adjusted for modality, PRD group and KRT duration; Model 3 additionally adjusted for SIMD, vaccination status and calendar time.

Sensitivity analyses and tests for effect modification

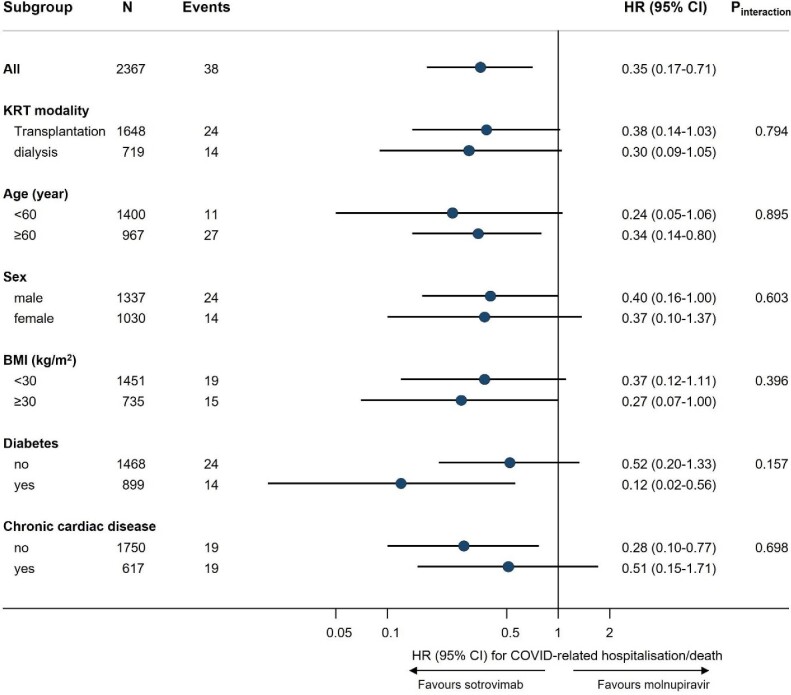

Results of sensitivity analyses were consistent with the main findings (Supplementary Table S3). Among patients included in the cause-specific analysis (n = 2350), 33 had COVID-19-related hospitalisation/death and 130 had other hospitalisation/death events within 28 days after treatment initiation. The cause-specific Cox model showed that, unlike COVID-related outcomes, there was no evidence of an association of sotrovimab with other hospitalisation/death compared with molnupiravir (HRs ranging from 0.73 to 0.85 in Models 1–4; P > .05; Table 2) despite a greater number of events compared with the primary outcome. No substantial effect modification was observed in subgroup analyses (all P-values for interaction >0.10; Fig. 2).

Figure 2:

Subgroup analysis of sotrovimab versus molnupiravir in association with risk of 28-day COVID-19-related hospitalisation/death (OpenSAFELY-UKRR cohort). Subgroup analyses were based on the fully adjusted stratified Cox model (Model 4). P-value for interaction between drug group and each of the following variables was: time period 16 February 2022–31 May 2022 (0.577), time period 1 June 2022–1 August 2022 (0.640), hypertension (0.286), chronic respiratory diseases (0.449), days between test positive and treatment initiation (0.377) and White ethnicity (0.379), respectively; no analyses within each level of these variables were done because of a lack of sample size or outcome events within the subset of population.

Exploratory analysis with untreated patients as comparators

In the exploratory analysis on effectiveness, 4588 untreated COVID-19 patients on KRT were included as comparators to the two drug groups. Compared with sotrovimab and molnupiravir users, the untreated group was older [mean age 58.1 years (SD 15.9)], had a lower proportion of kidney transplant recipients (43.6%), being White (75.3%), having had three or more COVID-19 vaccinations (83.2%) and had a higher proportion of patients with chronic cardiac disease (33.8%; Supplementary Table S4).

Among the 4588 untreated patients, 224 cases (4.9%) of COVID-19-related hospitalisations/deaths were observed during the 28 days of follow-up after a positive test, among which there were 60 (1.3%) COVID-19-related deaths. Results of time-varying Cox regression showed that, after adjusting for multiple covariates, treatment with sotrovimab was associated with a substantially lower risk of 28-day COVID-19-related hospitalisation/death than no treatment [Model 4: HR 0.38 (95% CI 0.23–0.63); P < 0.001], but no significant association was observed for molnupiravir [Model 4: HR 0.81 (95% CI 0.44–1.49); P = .492; Table 3]. As for all-cause hospitalisations/deaths (520 cases in the untreated group), the sotrovimab group [Model 4: HR 0.78 (95% CI 0.62–0.98); P = .039] but not the molnupiravir group [Model 4: HR 1.07 (95% CI 0.75–1.54); P = .704] had a lower risk compared with the untreated group (Table 3).

Table 3:

Comparing risks of outcome events within 28-days after a positive test between sotrovimab/molnupiravir versus untreated patients in the OpenSAFELY-UKRR dataset.

| Outcomes | HR (95% CI) for sotrovimab (ref = untreated) | P-value | HR (95% CI) for molnupiravir (ref = untreated) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 28-day COVID-19-related hospitalisation/death | ||||

| Model 1 | 0.38 (0.23–0.63) | <.001 | 0.94 (0.51–1.74) | .844 |

| Model 2 | 0.33 (0.20–0.55) | <.001 | 0.79 (0.43–1.45) | .443 |

| Model 3 | 0.38 (0.23–0.63) | <.001 | 0.79 (0.43–1.47) | .463 |

| Model 4 | 0.38 (0.23–0.63) | <.001 | 0.81 (0.44–1.49) | .492 |

| 28-day all-cause hospitalisation/death | ||||

| Model 1 | 0.74 (0.59–0.92) | .008 | 1.01 (0.70–1.44) | .975 |

| Model 2 | 0.74 (0.59–0.94) | .012 | 1.00 (0.70–1.44) | .995 |

| Model 3 | 0.78 (0.61–0.98) | .037 | 1.05 (0.73–1.50) | .810 |

| Model 4 | 0.78 (0.62–0.98) | .039 | 1.07 (0.75–1.54) | .704 |

In this analysis, 4588 untreated patients, 1624 sotrovimab users and 439 molnupiravir users were included (after excluding those whose positive test date was missing or outside of the study period). Model 1 adjusted for age and sex and stratified by region; Model 2 additionally adjusted for high-risk cohort categories, KRT modality and duration; Model 3 additionally adjusted for ethnicity, IMD quintiles, vaccination status, calendar date; and Model 4 additionally adjusted for BMI category, diabetes, hypertension, chronic cardiac and respiratory diseases.

SRR cohort

Between 21 December 2021 and 31 August 2022, a total of 993 non-hospitalised COVID-19 patients on KRT were treated with sotrovimab (n = 723) or molnupiravir (n = 270). The mean age of these patients was 57.4 years (SD 13.9), 42.6% were female and 93.5% had three or more COVID-19 vaccinations; 65.3% were kidney transplant recipients and 34.7% were on dialysis. Compared with the molnupiravir group, the sotrovimab group had a lower proportion of kidney transplant recipients (55.2% versus 92.2%; Table 1).

During the 28 days of follow-up after treatment initiation, 19 cases (1.9%) of COVID-19-related hospitalisations/deaths were observed, with 12 (1.7%) in the sotrovimab group and 7 (2.6%) in the molnupiravir group. There were six COVID-19-related deaths in the sotrovimab group and five in the molnupiravir group.

Results of the Cox regression showed that after adjusting for age, sex, modality, primary renal diagnosis, Scottish IMD [24], vaccination status, KRT duration and calendar date, treatment with sotrovimab was consistent with a lower risk of 28-day COVID-19-related hospitalisation/death than treatment with molnupiravir, although CIs were broad and crossed the null [HR 0.39 (95% CI 0.13–1.21); P = .106; Fig. 1]. There was no substantial difference between sotrovimab and molnupiravir in the risk of all-cause hospitalisation/death (HRs ranging from 0.71 to 1.04 in Models 1–3; P > .05) or other hospitalisation/death (HRs ranging from 0.90 to 1.29 in Models 1–3; P > .05; Table 2).

DISCUSSION

Our analysis shows that among people receiving KRT, treatment with sotrovimab is associated with a lower risk of severe outcomes from COVID-19 infection compared with molnupiravir during the Omicron wave in England in 2021–2022. We used a range of analytic methods to examine robustness of results and were able to carry out extensive adjustments for confounding given the availability of granular multisource real-world data. Analyses in an independent dataset from the SRR showed consistent effect estimates.

In addition, although it is likely that there are greater unmeasured differences in baseline health status and severity of COVID-19 between treated and untreated patients than between people treated with different medications (as reflected in Supplementary Table S4), results also showed supportive evidence for the effectiveness of sotrovimab but not molnupiravir when compared with no treatment in the infected KRT population.

This study used two validated KRT populations from 2021 reported by all kidney care centres in England and Scotland at the start of the Omicron outbreak in two independent analyses that gave broadly similar results. This is the first time analyses from the two independent renal registries, both recognised as high-quality and complete data sources, have been combined. The English data were combined with multisource data from the OpenSAFELY resource, which allowed extensive adjustment for confounding. The Scottish data had less statistical power and fewer granular variables for confounding adjustment and yielded more unstable point estimates across different statistical approaches (e.g. HR for 28-day COVID-19-related outcomes being 0.39 in the Cox regression and 0.78 in the propensity score analysis). Of note, in the English data, detailed adjustment for confounding did not materially change the results.

Several limitations of this study need to be considered. There are regional variations in terms of immune priming and survivorship bias in the KRT population because the pandemic has affected different parts of the country in different ways [25]. Similarly, there may be regional variations in how referral pathways operated for patients to receive antiviral treatment during the Omicron pandemic, which could underlie the marked regional variation of antiviral use in our data. To account for these differences, we stratified UKRR OpenSAFELY data analyses by English region and adjusted for region in propensity score analyses.

Despite the granular data on underlying health status, the possibility of residual confounding cannot be ruled out in this real-world observational study. In February 2022, prescribing guidelines changed and molnupiravir was deprioritised as a third-line treatment option [15], which reduces therapeutic equipoise and may make these two treatment groups less comparable. A pointer towards potential residual confounding may be the association between treatment and all-cause hospitalisation and death, which was not observed in the general population [26]. However, in this KRT population with high levels of comorbidity and frailty, it is possible that more effective treatment of COVID-19 reduced the incidence of other outcomes to an observable extent. Overall, given the size of the observed protective effect of sotrovimab and its robustness across multiple sensitivity analyses, residual confounding would have to be substantial to fully explain the findings. Consistent findings in independent validation in the SRR, where sources of bias and treatment pathways differed, adds further robustness to the analysis. In addition, a pragmatic trial for molnupiravir during the Omicron era, the UK PANORAMIC trial, showed that molnupiravir did not reduce the risk of hospitalisations/deaths among high-risk vaccinated adults with COVID-19 in the community [18].

Determining the current efficacy of treatments for COVID-19 is complicated due to changes in prevalence of circulating virus types, making gold-standard clinical trial data rapidly outdated. In vitro evidence is useful to understand activity of treatments against current viral subtypes but can be affected by the nature of assays and, in the case of sotrovimab, yield conflicting results [27–29]. Those data have led to changing and sometimes conflicting recommendations for prioritisation of COVID-19 treatments between countries and over time [19–21]. Well-conducted studies with routinely collected healthcare data can provide rapid analysis of drug effectiveness and safety and can be particularly valuable for populations underrepresented in clinical trials, such as KRT patients. In addition, analysis can be conducted within eras of different viral subtype dominance to update effectiveness estimates for new variants. Our data, alongside recent in vitro data, have helped to inform decision making about COVID-19 treatments, leading to a current recommendation for sotrovimab for people contraindicated for Paxlovid (including KRT patients) by the UK National Institute for Health and Care Excellence [21].

In summary, in routine care of non-hospitalised patients with COVID-19 on KRT, across periods of dominance of different subvariants of Omicron, sotrovimab was associated with a substantially lower risk of severe COVID-19 outcomes compared with molnupiravir.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We are very grateful for all the support received from the TPP Technical Operations team throughout this work and for generous assistance from the information governance and database teams at NHS England and the NHS England Transformation Directorate. We are also grateful to the UKRR Patient Council and KidneyCare UK, who supported the data linkage to OpenSAFELY, and to colleagues at Public Health Scotland (Chrissie Watters, Euan Proud and Marion Bennie) and the SRR Steering group (Alison Almond, Katharine Buck, Wan Wong, Nicola Joss, Michaela Petrie, Shona Methven, Elaine Spalding and Peter Thomson). This article contains data that have been supplied by the UKRR of the UK Kidney Association. The interpretation and reporting of these data are the responsibility of the authors and in no way should be seen as an official policy or interpretation of the UKRR or the UK Kidney Association.

Contributor Information

Bang Zheng, London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, Keppel Street, London, UK.

Jacqueline Campbell, Scottish Renal Registry, Scottish Health Audits, Public Health Scotland, Glasgow, UK.

Edward J Carr, Francis Crick Institute, London, UK.

John Tazare, London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, Keppel Street, London, UK.

Linda Nab, Bennett Institute for Applied Data Science, Nuffield Department of Primary Care Health Sciences, University of Oxford, Oxford, UK.

Viyaasan Mahalingasivam, London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, Keppel Street, London, UK.

Amir Mehrkar, Bennett Institute for Applied Data Science, Nuffield Department of Primary Care Health Sciences, University of Oxford, Oxford, UK.

Shalini Santhakumaran, UK Renal Registry, Bristol, UK.

Retha Steenkamp, UK Renal Registry, Bristol, UK.

Fiona Loud, Kidney Care UK, Alton, UK.

Susan Lyon, Patient Council, UK Kidney Association, Bristol, UK.

Miranda Scanlon, Kidney Research UK, Peterborough, UK.

William J Hulme, Bennett Institute for Applied Data Science, Nuffield Department of Primary Care Health Sciences, University of Oxford, Oxford, UK.

Amelia C A Green, Bennett Institute for Applied Data Science, Nuffield Department of Primary Care Health Sciences, University of Oxford, Oxford, UK.

Helen J Curtis, Bennett Institute for Applied Data Science, Nuffield Department of Primary Care Health Sciences, University of Oxford, Oxford, UK.

Louis Fisher, Bennett Institute for Applied Data Science, Nuffield Department of Primary Care Health Sciences, University of Oxford, Oxford, UK.

Edward Parker, London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, Keppel Street, London, UK.

Ben Goldacre, Bennett Institute for Applied Data Science, Nuffield Department of Primary Care Health Sciences, University of Oxford, Oxford, UK.

Ian Douglas, London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, Keppel Street, London, UK.

Stephen Evans, London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, Keppel Street, London, UK.

Brian MacKenna, Bennett Institute for Applied Data Science, Nuffield Department of Primary Care Health Sciences, University of Oxford, Oxford, UK.

Samira Bell, Scottish Renal Registry, Scottish Health Audits, Public Health Scotland, Glasgow, UK; Division of Population Health and Genomics, School of Medicine, University of Dundee, Dundee, UK.

Laurie A Tomlinson, London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, Keppel Street, London, UK.

Dorothea Nitsch, London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, Keppel Street, London, UK; UK Renal Registry, Bristol, UK.

FUNDING

This work was jointly funded by the Wellcome Trust (222097/Z/20/Z); Medical Research Council (MR/V015757/1, MC_PC-20059, MR/W016729/1); UK Research and Innovation (MC_PC_20051, MC_PC_20058); National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR; COV-LT-0009, NIHR135559, COV-LT2-0073); and Health Data Research UK (HDRUK2021.000, 2021.0157). The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NIHR, NHS England, UK Health Security Agency or the Department of Health and Social Care. Funders had no role in the study design; collection, analysis, and interpretation of data; writing of the report; or the decision to submit the article for publication.

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTIONS

D.N., L.A.T., S.B. and B.Z. conceived the idea of this study. B.Z. and J.C. were responsible for the data analysis. B.Z., D.N., L.A.T., S.B. and E.J.C. drafted the original version of the manuscript. A.M., B.G., B.M., W.J.H. and L.F. contributed to information governance and project administration. All authors contributed to interpretation of the results, critical revision of the manuscript and approved the final manuscript.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

All data were linked, stored and analysed securely within the OpenSAFELY platform: https://opensafely.org/. Detailed pseudonymised patient data is potentially re-identifiable and therefore not shared.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

B.G. has received research funding from the Laura and John Arnold Foundation, NIHR, NIHR School of Primary Care Research, NHS England, NIHR Oxford Biomedical Research Centre, Mohn–Westlake Foundation, NIHR Applied Research Collaboration Oxford and Thames Valley, Wellcome Trust, Good Thinking Foundation, Health Data Research UK, Health Foundation, World Health Organization, UKRI MRC, Asthma UK, British Lung Foundation and the Longitudinal Health and Wellbeing strand of the National Core Studies programme; he is a non-executive director at NHS Digital; he also receives personal income from speaking and writing for lay audiences on the misuse of science. B.M.K. is employed by NHS England, working on medicines policy and a clinical lead for primary care medicines data. A.M. is a member of RCGP health informatics group and the NHS Digital GP data Professional Advisory Group, and received consulting fee from Induction Healthcare. E.P. was a consultant for WHO SAGE COVID-19 Vaccines Working Group. I.J.D. has received research grants from GSK and AstraZeneca and holds shares in GSK. J.T. was funded by an unrestricted grant from GSK for methodological research unrelated to this work. S.L. received remuneration for medical writing from Kidney Care UK, UK Kidney Association and GORE; support for attending meeting from UK Kidney Association; and is Chair of Patients Council of UK Kidney Association, and Secretary and Trustee of Guy's & St Thomas' Kidney Patients' Association. V.M. received grant from National Institute for Health and Care Research. E.C. is a member of UK Kidney Association Infection Prevention & Control committee. F.L. received grants to institution from AstraZeneca, Pfizer, Novartis, and payment to institution from AstraZeneca for scientific events. S.B. received consulting fees from GSK and AstraZeneca. D.N. received grants from National Institute for Health and Care Research, MRC and GSK Open Lab, unrelated to this work; and is the UKKA Director of Informatics Research. L.A.T. has received research funding from MRC, Wellcome, NIHR and GSK, consulted for Bayer in relation to an observational study of chronic kidney disease (unpaid), and is a member of 4 non-industry funded (NIHR/MRC) trial advisory committees (unpaid) and MHRA Expert advisory group (Women's Health). The other authors declare no conflicts of interest.

INFORMATION GOVERNANCE AND ETHICAL APPROVAL

OpenSAFELY: This study was approved by the Health Research Authority (REC reference 20/LO/0651) and by the LSHTM Ethics Board (reference 21863). NHS England is the data controller for OpenSAFELY-TPP; TPP is the data processor; all study authors using OpenSAFELY have the approval of NHS England. This implementation of OpenSAFELY is hosted within the TPP environment, which is accredited to the ISO 27001 information security standard and is NHS IG Toolkit compliant. Patient data has been pseudonymised for analysis and linkage using industry standard cryptographic hashing techniques; all pseudonymised datasets transmitted for linkage onto OpenSAFELY are encrypted; access to the platform is via a virtual private network (VPN) connection, restricted to a small group of researchers; the researchers hold contracts with NHS England and only access the platform to initiate database queries and statistical models; all database activity is logged; only aggregate statistical outputs leave the platform environment following best practice for anonymisation of results such as statistical disclosure control for low cell counts. The OpenSAFELY research platform adheres to the obligations of the UK General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) and the Data Protection Act 2018. In March 2020, the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care used powers under the UK Health Service (Control of Patient Information) Regulations 2002 (COPI) to require organizations to process confidential patient information for the purposes of protecting public health, providing healthcare services to the public and monitoring and managing the COVID-19 outbreak and incidents of exposure; this sets aside the requirement for patient consent. This was extended in November 2022 for the NHS England OpenSAFELY COVID-19 research platform. In some cases of data sharing, the common law duty of confidence is met using, for example, patient consent or support from the Health Research Authority Confidentiality Advisory Group. Taken together, these provide the legal bases to link patient datasets on the OpenSAFELY platform. GP practices, from which the primary care data are obtained, are required to share relevant health information to support the public health response to the pandemic, and have been informed of the OpenSAFELY analytics platform. This project includes data from the UKRR derived from patient-level information collected by the NHS as part of the care and support of kidney patients. We thank all kidney patients and kidney centres involved. The data are collated, maintained and quality assured by the UKRR, which is part of the UK Kidney Association. Access to the data was facilitated by the UKRR's Data Release Group. UKRR data are used within OpenSAFELY to address a limited number of critical audit and service delivery questions related to the impact of COVID-19 on patients with kidney disease. OpenSAFELY has developed a publicly available website (https://opensafely.org/) through which we invite any patient or member of the public to make contact regarding this study or the broader OpenSAFELY project. Patient representatives, including those representing the UKRR patient council and KidneyCare UK, have actively contributed to the presentation of these results and are co-authors on this article.

SRR: Formal ethical approval was waived according to Public Health Scotland Information Governance as analysis of routinely collected data. As the analysis used routinely collected and anonymized data, individual patient consent was not sought. Access and use of the data for the purpose of this work were approved following a Public Health Scotland Information Governance review of linking internal datasets. Only the Public Health Scotland analyst had access to the linked patient data, which could only be accessed via an NHS secure network.

REFERENCES

- 1. Williamson EJ, Walker AJ, Bhaskaran Ket al. . Factors associated with COVID-19-related death using OpenSAFELY. Nature 2020;584:430–6. 10.1038/s41586-020-2521-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Su G, Iwagami M, Qin Xet al. . Kidney disease and mortality in patients with respiratory tract infections: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Kidney J 2021;14:602–11. 10.1093/ckj/sfz188 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Savino M, Casula A, Santhakumaran Set al. . Sociodemographic features and mortality of individuals on haemodialysis treatment who test positive for SARS-CoV-2: a UK Renal Registry data analysis. PLoS One 2020;15:e0241263. 10.1371/journal.pone.0241263 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Verity R, Okell LC, Dorigatti Iet al. . Estimates of the severity of coronavirus disease 2019: a model-based analysis. Lancet Infect Dis 2020;20:669–77. 10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30243-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Nab L, Parker EPK, Andrews CDet al. . Changes in COVID-19-related mortality across key demographic and clinical subgroups: an observational cohort study using the OpenSAFELY platform on 18 million adults in England. Lancet Public Health 2023;8:E364–77. 10.1016/S2468-2667(23)00079-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Carr EJ, Kronbichler A, Graham-Brown Met al. . Review of early immune response to SARS-CoV-2 vaccination among patients with CKD. Kidney Int Rep 2021;6:2292–304. 10.1016/j.ekir.2021.06.027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Danziger-Isakov L, Kumar D, AST ID Community of Practice . Vaccination of solid organ transplant candidates and recipients: guidelines from the American society of transplantation infectious diseases community of practice. Clin Transplant 2019;33:e13563. 10.1111/ctr.13563 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Voysey M, Clemens SAC, Madhi SAet al. . Safety and efficacy of the ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 vaccine (AZD1222) against SARS-CoV-2: an interim analysis of four randomised controlled trials in Brazil, South Africa, and the UK. Lancet 2021;397:99–111. 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)32661-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Polack FP, Thomas SJ, Kitchin Net al. . Safety and efficacy of the BNT162b2 mRNA Covid-19 vaccine. N Engl J Med 2020;383:2603–15. 10.1056/NEJMoa2034577 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Baden LR, El Sahly HM, Essink Bet al. . Efficacy and safety of the mRNA-1273 SARS-CoV-2 vaccine. N Engl J Med 2021;384:403–16. 10.1056/NEJMoa2035389 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Martin P, Gleeson S, Clarke CLet al. . Comparison of immunogenicity and clinical effectiveness between BNT162b2 and ChAdOx1 SARS-CoV-2 vaccines in people with end-stage kidney disease receiving haemodialysis: a prospective, observational cohort study. Lancet Reg Health Eur 2022;21:100478. 10.1016/j.lanepe.2022.100478 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Prendecki M, Thomson T, Clarke CLet al. . Immunological responses to SARS-CoV-2 vaccines in kidney transplant recipients. Lancet 2021;398:1482–4. 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)02096-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Carr EJ, Wu M, Harvey Ret al. . Neutralising antibodies after COVID-19 vaccination in UK haemodialysis patients. Lancet 2021;398:1038–41. 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)01854-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Carr EJ, Wu M, Harvey Ret al. . Omicron neutralising antibodies after COVID-19 vaccination in haemodialysis patients. Lancet 2022;399:800–2. 10.1016/S0140-6736(22)00104-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. National Health Service . Antivirals or neutralising antibodies for non-hospitalised patients with COVID-19. https://www.cas.mhra.gov.uk/ViewandAcknowledgment/ViewAlert.aspx?AlertID=103208 [accessed 27 February 2023]. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Gupta A, Gonzalez-Rojas Y, Juarez Eet al. . Effect of sotrovimab on hospitalization or death among high-risk patients with mild to moderate COVID-19: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2022;327:1236–46. 10.1001/jama.2022.2832 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Jayk Bernal A, Gomes da Silva MM, Musungaie DBet al. . Molnupiravir for oral treatment of Covid-19 in nonhospitalized patients. N Engl J Med 2022;386:509–20. 10.1056/NEJMoa2116044 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Butler C, Hobbs R, Gbinigie Oet al. . Molnupiravir plus usual care versus usual care alone as early treatment for adults with COVID-19 at increased risk of adverse outcomes (PANORAMIC): preliminary analysis from the United Kingdom Randomised, Controlled Open-Label, Platform Adaptive Trial. SSRN 2022; 10.2139/ssrn.4237902 or 10.2139/ssrn.4237902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Agarwal A, Rochwerg B, Lamontagne Fet al. . A living WHO guideline on drugs for covid-19. BMJ 2020;370:m3379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. U.S. Food & Drug Administration . FDA updates sotrovimab emergency use authorization. 2022; https://www.fda.gov/drugs/drug-safety-and-availability/fda-updates-sotrovimab-emergency-use-authorization [accessed 27 February 2023]. [Google Scholar]

- 21. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence . Final draft guidance: therapeutics for people with COVID-19. 2023; www.nice.org.uk/guidance/indevelopment/gid-ta10936 [accessed 27 February 2023]. [Google Scholar]

- 22. UK Health Security Agency . SARS-CoV-2 variants of concern and variants under investigation in England: technical briefing 48. 2022; https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/1120304/technical-briefing-48-25-november-2022-final.pdf [accessed 27 February 2023]. [Google Scholar]

- 23. National Health Service . Neutralising monoclonal antibodies (nMABs) or antivirals for non-hospitalised patients with COVID-19. 2021; https://www.cas.mhra.gov.uk/ViewandAcknowledgment/ViewAlert.aspx?AlertID=103186 [accessed 27 February 2023]. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Scottish Government . Scottish Index of Multiple Deprivation 2012: general report. 2012; https://www.gov.scot/publications/scottish-index-multiple-deprivation-2012-executive-summary/ [accessed 27 February 2023]. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Savino M, Casula A, Santhakumaran Set al. . Sociodemographic features and mortality of individuals on haemodialysis treatment who test positive for SARS-CoV-2: a UK Renal Registry data analysis. PLoS One 2020;15:e0241263. 10.1371/journal.pone.0241263 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Zheng B, Green ACA, Tazare Jet al. . Comparative effectiveness of sotrovimab and molnupiravir for prevention of severe covid-19 outcomes in patients in the community: observational cohort study with the OpenSAFELY platform. BMJ 2022;379:e071932. 10.1136/bmj-2022-071932 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Wu MY, Carr EJ, Harvey Ret al. . WHO's therapeutics and COVID-19 living guideline on mAbs needs to be reassessed. Lancet 2022;400:2193–6. 10.1016/S0140-6736(22)01938-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Bruel T, Hadjadj J, Maes Pet al. . Serum neutralization of SARS-CoV-2 Omicron sublineages BA.1 and BA.2 in patients receiving monoclonal antibodies. Nat Med 2022;28:1297–302. 10.1038/s41591-022-01792-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Iketani S, Liu L, Guo Yet al. . Antibody evasion properties of SARS-CoV-2 Omicron sublineages. Nature 2022;604:553–6. 10.1038/s41586-022-04594-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data were linked, stored and analysed securely within the OpenSAFELY platform: https://opensafely.org/. Detailed pseudonymised patient data is potentially re-identifiable and therefore not shared.