Abstract

In this article, we reviewed the possible mechanisms linking the clonal hematopoiesis of indeterminate potential (CHIP) to chronic myeloproliferative neoplasms (MPNs), autoimmune diseases (ADs), and cardiovascular diseases (CADs). CHIP is characterized by the presence of clonal mutations with an allelic frequency >2% in the peripheral blood without dysplasia, overt hematological neoplasms, or abnormalities in blood cell count. The prevalence may reach 20% of elderly healthy individuals and is considered a risk factor for myelodysplastic neoplasms and acute leukemia. In MPNs, CHIP is often associated with mutations such as JAK2V617F or DNMT3A, TET2, or ASXL1, which exhibit a 12.1- and 1.7–2-fold increase in CADs. Specifically, JAK2-mutated cells produce excessive cytokines and reactive oxygen species, leading to proinflammatory modifications in the bone marrow microenvironment. Consequently, the likelihood of experiencing thrombosis is influenced by the variant allele frequency (VAF) of the JAK2V617F mutation, which also appears to be correlated with anti-endothelial cell antibodies that sustain thrombosis. However, DNMT3A mutations induce pro-inflammatory T-cell polarization and activate the inflammasome complex, while TET2 downregulation leads to endothelial cell autophagy and inflammatory factor upregulation. As a result, in patients with TET2 and DNMT3A-related CHIP, the inflammasome hyperactivation represents a potential cause of CADs. CHIP also occurs in patients with large and small vessel vasculitis, while ADs are more frequently associated with MPNs. In these diseases, monocytes and neutrophils play a key role in the formation of neutrophil extracellular trap (NET) as well as anti-endothelial cell antibodies, resulting in a final procoagulant effect. ADs, such as systemic lupus erythematosus, psoriasis, and arthritis, are also characterized by an overexpression of the Rho-associated coiled-coil containing protein kinase 2 (ROCK2), a serine/threonine kinase that can hyperactivate the JAK-STAT pathway. Interestingly, hyperactivation of ROCK2 has also been observed in myeloid malignancies, where it promotes the growth and survival of leukemic cells. In summary, the presence of CHIP, with or without neoplasia, can be associated with autoimmune manifestations and thrombosis. In the presence of these manifestations, it is necessary to consider a “disease-modifying therapy” that may either reduce the clonal burden or inhibit the clonally activated JAK pathway.

Keywords: CHIP, myeloproliferative neoplasms, autoimmune disease, cardiovascular disease, JAK2, ROCK2, TET2, DNMT3A

1. Introduction

Philadelphia-negative chronic myeloproliferative neoplasms (MPNs) are clonal diseases originating from a single hematopoietic stem cell that causes excessive production of mature blood cells (1). According to the World Health Organization (WHO) and the International Consensus Classification (ICC) criteria, MPNs include polycythemia vera (PV), essential thrombocythemia (ET), and myelofibrosis (MF) (2, 3). The clonal origin of MPNs was identified in 1976 by studying X-chromosome inactivation patterns in the peripheral blood of female patients (4). Subsequently, the clonal nature of MPNs was further solidified by using multiple genetic analyses, such as whole-genome sequencing (WGS) and clonal mice model (5, 6). Currently, there is a lack of consensus regarding the appropriate nomenclature of mutations in MPNs; however, recently, the following classifications have been proposed: “disease driver mutations,” “clonal driver mutations,” “passenger mutations,” and “variants of unknown significance” (1).

The underlying cause of MPNs (1) is the acquisition of gain-of-function mutations in one of three “disease driver genes”: Janus kinase 2 (JAK2), Calreticulin (CALR), and the thrombopoietin receptor (MPL). Clearly, these mutations alone are sufficient to initiate and promote MPN without the need for additional cooperating mutations (6, 7). The JAK2-V617F mutation is present in most of the PV patients and in approximately half of the patients with ET or MF (8) that can show CALR or MPL mutations or be “triple negative” (9–11). Regardless of the presence or absence of specific driver gene mutations, the constitutive activation of the Janus kinase-signal transducer and activator of the transcription (JAK/STAT) signaling pathway is a common feature in all MPNs (12). “Clonal driver mutations,” when present alone, do not induce a specific MPN phenotype; anyway, they can modify the features of the disease when combined with one of other “disease driver” mutations that can be found across a range of myeloid malignancies (13–18). Most of these mutations involve epigenetic regulator genes (TET2, ASXL1, DNMT3A, EZH2, and IDH1/2), genes of messenger RNA splicing (U2AF1, SF3B1, SRSF2, and ZRSR2), or DNA repair (PPM1D and TP53), with TET2, ASXL1, and DNMT3A accounting for up to 80% of all cases of clonal hematopoiesis (19). “Passenger mutations” refer to genetic alterations that do not contribute to disease pathogenesis and manifestations. In some instances, predicting whether a gene mutation will alter function can be challenging, particularly since many mutations have not been extensively studied. Consequently, these mutations are initially categorized as “variants of unknown significance,” but over time, as our understanding of these mutations grows, they may be reclassified as disease driver mutations or passenger mutations (1).

The molecular mechanisms of clonal hematopoiesis underlying hematological manifestations were extensively explored and described. Nevertheless, the prognosis and the treatment were mainly associated with non-hematological manifestations: inflammation/autoimmunity and subsequent thrombosis.

Recently, the molecular pathogenesis of non-hematological manifestations has been recognized as increasingly important after the discovery of the clonal hematopoiesis of indeterminate potential (CHIP). CHIP is characterized by the presence of clonal mutation with an allelic frequency >2% in peripheral blood, without dysplasia, overt hematological neoplasms, or abnormalities in blood cell count, which represents a risk factor for myelodysplasia and leukemia (19–21). It is worth noting that mutations can lead to autoimmunity and thrombosis even in the absence of neoplasia. In fact, the prevalence of CHIP is significantly higher in individuals with autoimmune diseases (ADs) when compared to the normal population, being the highest in large vessel vasculitis and small vessel vasculitis, with rates of 33.3 and 30.4%, respectively (as shown in Table 1) (22–27). Meanwhile, patients with CHIP, represented by JAK2V617F mutation, had a 12.1-fold increase in cardiovascular diseases (CADs), while CHIP sustained by DNMT3A, TET2, or ASXL1 had a 1.7–2-fold increase in CADs (28). These associations taken together suggest that clonal hematopoiesis is associated with autoimmunity and inflammation independently from the presence of neoplasia.

Table 1.

Prevalence of overall and single somatic mutations in autoimmune diseases.

| References | ADs | CHIP overall prevalence n (%) | CHIP mutation | Single CHIP prevalence n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Savola et al. (22) | Rheumatoid arthritis | 10/59 (16.9) | DNMT3A TET2 GNAS CBL TP53 ASXL1 | 4/59 (6, 8) 3/59 (5, 1) 2/59 (3, 4) 1/59 (1, 7) 1/59 (1, 7) 1/59 (1, 7) |

| Ricard et al. (23) | Systemic Sclerosis | 13/90 (14, 4) | DNMT3A ATM SETBP1 NF1 SF3B1 TP53 TET2 CBL |

7/90 (7, 8) 2/90 (2, 2) 1/90 (1, 1) 1/90 (1, 1) 1/90 (1, 1) 1/90 (1, 1) 1/90 (1, 1) 1/90 (1, 1) |

| Arends et al. (24) | Anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (ANCA)-associated vasculitides | 34/112 (30, 4) | DNMT3A TET2 ASXL1 SRSF2 TP53 PPM1D RAD21 BCCOR ETV6 GNAS GNB1 KDM6A SF3B1 |

19/112 (17, 0) 7/112 (6, 3) 5/112 (4, 5) 3/112 (2, 7) 2/112 (1, 8) 2/112 (1, 8) 2/112 (1, 8) 1/112 (1, 8) 1/112 (1, 8) 1/112 (1, 8) 1/112 (1, 8) 1/112 (1, 8) 1/112 (1, 8) |

| David et al. (25) | Systemic lupus erythematosus | 47/438 (10, 7) | DNMT3A TET2 GNAS ASXL1 SH2B3 TP53 CBL ETV6 JAK2 KDM6A NFE2 PPM1D SETBP1 SMC3 |

39/438 (8, 9) 7/438 (1, 6) 3/438 (0, 7) 2/438 (0, 5) 2/438 (0, 5) 2/438 (0, 5) 1/438 (0, 2) 1/438 (0, 2) 1/438 (0, 2) 1/438 (0, 2) 1/438 (0, 2) 1/438 (0, 2) 1/438 (0, 2) 1/43 8 (0, 2) |

| Park et al. (26) | Behçet's disease | 13/117 (11, 1) | DNMT3A TET2 ASXL1 STAG2 IDH2 |

9/117 (7, 7) 2/117 (1, 7) / / / |

| Papo et al. (27) | Giant cell arteritis | 5/15 (33, 3) | DNMT3A CBL |

4/15 (26, 7) 1/15 (6, 7) |

Some patients carried more than one mutation. Ads, autoimmune diseases; CHIP, Clonal hematopoiesis of indeterminate potential.

The clinical impact of CHIP is quite evident. In addition to being associated with ADs, it has been reported that CHIP increases the risk of death in individuals with hematological neoplasms by 40%. However, only 0.5% of them actually succumb to cancer. Additionally, MPNs have a higher incidence of CADs, including ischemic stroke (HR 2.6) and premature myocardial infarction (HR 4.0), which are not related to traditional cardiovascular risk factors (19, 29).

This narrative review aims to investigate the association between clonal hematopoiesis and autoimmune and cardiovascular manifestations. In particular, we have described how the immune system can modify clonal hematopoiesis progression and how the molecular pathogenesis of clonal hematopoiesis might be related to ADs and CADs. The search was conducted across various electronic databases (PUBMED, MEDLINE) to identify relevant articles published in the English language using the following keywords: “myeloproliferative disease,” “autoimmune disease,” “autoimmunity,” “thrombosis,” “clonal haematopoiesis,” and “inflammation.” No geographic restrictions were imposed, ensuring a global representation of research findings. We included all articles relevant to the abovementioned purposes, while excluding the others.

2. Clonal hematopoiesis of driver mutations in myeloproliferative chronic neoplasms

JAK2 plays a crucial role as a signal transducer in the hematopoietic stem cell (HSC) compartment, facilitating growth, and differentiation in response to cytokine receptors without intrinsic kinase activity. These receptors include the erythropoietin receptor, the thrombopoietin receptor, and the granulocyte colony-stimulating factor receptor. The presence of JAK2V617F mutation leads to the activation of STAT with subsequent increased levels of red blood cells, neutrophils, and platelets (30–33). In fact, there is a direct correlation between the allele burden of JAK2V617F and various measurements of stimulated erythropoiesis and myelopoiesis (34).

In addition to JAK-STAT signaling, other pathways, such as phosphatidylinositol-3-kinase/AKT (PI3K/AKT) and the RAS/mitogen-activated protein kinases (RAS/MAPK), are also overactivated by the JAK2V617F mutation (35). Specifically, JAK2-mutated HSCs produce excessive cytokines and reactive oxygen species (ROS), leading to inflammatory modifications in the bone marrow microenvironment. The inflammatory environment further strengthens the competitive advantage of the clonal cells and contributes to their genomic instability (36, 37).

Moreover, the excessive cellularity in the bone marrow induces a state of pseudohypoxia activating hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF). High levels of HIF, in turn, enhance HSC self-renewal. This effect is achieved through the downregulation of LKB1/STK11, a protein known to negatively regulate HSC self-renewal (38).

CALR mutations in MPNs involve insertions and/or deletions in exon 9, which cause a frameshift and lead to the production of a new positively charged C-terminus in the mutant CALR protein. This unique C-terminus in the mutant CALR enables its binding to MPL (myeloproliferative leukemia) protein, initiating activation of the MPL/JAK/STAT signaling pathway (39).

The STAT family is also a key component in the pathogenesis of MPNs. In fact, deletion of STAT5 in transgenic mouse models expressing JAK2V617F mutation abolishes the disease phenotypes. Moreover, STAT1 has been identified as a promoter of megakaryopoiesis downstream of GATA1. In a mouse model of MPN, deletion of STAT1 in the presence of JAK2V617F leads to a reduction in megakaryopoiesis and a preference for erythropoiesis. Conversely, loss of STAT3 in hematopoietic cells enhances JAK2V617F-driven thrombopoiesis, potentially mediated by increased expression and activation of STAT1. In fact, in MPNs, STAT1, and STAT3 activation are reciprocally regulated, and imbalances in their activity can change cytokine and growth factor signals (40, 41).

However, MPNs are also characterized by disease driver mutations: 27% of patients carry TET2 mutations and 16% carry DNMT3A mutations, which are the most frequent gene aberrations sustaining CHIP (42). Clearly, it has been reported that DNMT3A mutations activate the inflammasome complex and induce proinflammatory T-cell polarization, which is responsible for cardiovascular effects, as demonstrated in the murine model, where DNMT3A deletion in stem cells induces cardiac hypertrophy and reduces cardiac function (43). Analogously, in another murine model, TET2 downregulation leads to endothelial cell autophagy and inflammatory factors upregulation (44). It has been reported that 5.1% of subjects with atherosclerosis have CHIP, and the presence of TET2-related clonal hematopoiesis significantly increases the risk of adverse outcomes (45). Moreover, in a series of 125 MPN patients, 28% had thrombotic events; similarly, in ET patients, the TET2 mutations were an independent risk factor for thrombosis (HR 4.1). However, they did not have an effect on CADs in patients affected by PV (46).

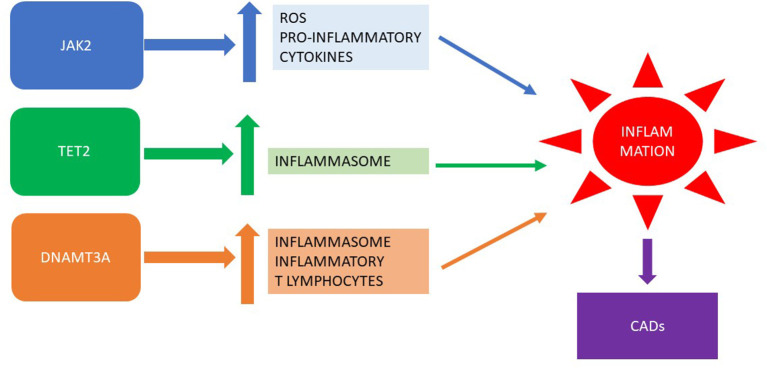

The relationship between clonal hematopoiesis of driver mutations in MPNs and CADs is depicted in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Clonal hematopoiesis of driver mutations in MPNs: inflammation and CADs. MPN, myeloproliferative neoplasm; CADs, cardiovascular diseases.

3. Risk of thrombosis in MPNs

A meta-analysis revealed that, upon initial diagnosis of MPN, thrombosis was observed in approximately 20% of patients: arterial thrombosis was prevalent in approximately 16.2% of subjects, while venous thrombosis accounted for 6.2% of cases. Common thrombotic events included cerebrovascular disease or transient ischemic attack, coronary heart disease, and deep venous thrombosis (47). In the MPNs, thrombosis resulted from the interactions between inflammatory and procoagulant factors and microparticles, along with qualitative and quantitative abnormalities of red cells, leukocytes, platelets, and endothelial cells.

An increased number of red blood cells can lead to the development of venous or arterial thrombosis by an augmented blood viscosity; however, this factor alone is not sufficient to explain the heightened thrombotic tendency observed in PV. This can be evidenced by the fact that individuals with comparable or even higher levels of secondary erythrocytoses, such as those caused by high altitude or chronic obstructive lung disease, generally do not exhibit increased susceptibility to thrombosis (48). Nevertheless, it is worth noting that sustained normalization of hematocrit levels (to below 45%) in PV patients is associated with a reduction in thrombotic events, indicating that erythrocytosis plays a significant role as a risk factor for thrombosis in PV (49).

There are no confirmed associations between elevated platelet levels and the occurrence of initial thrombotic and vascular complications in patients. Surprisingly, individuals with essential thrombocythemia and extreme thrombocytosis tend to experience bleeding complications rather than thrombotic events, which may be due to acquired von Willebrand disease (48, 50, 51).

The association between leucocytosis and thrombosis risk in patients with MPNs is still not fully established but demonstrates some evidence. The relationship between leucocytosis and thrombosis was primarily observed in arterial thrombotic events and predominantly in patients with ET. Studies have linked leukocyte counts above 15.3 × 109/L in PV and 11.3 × 109/L in ET with an increased risk of thrombosis (52, 53). A meta-analysis further confirmed that leucocytosis is an established risk factor for thrombosis, and it is likely to be independent of other factors (54).

4. Influence of the immune system on clonal hematopoiesis developments

ADs and inflammation may play an important role in inducing or avoiding clonal hematopoiesis development. Indeed, the prevalence of JAK2V617F clonal CHIP is significantly higher than the CALR-mutated one, resulting in a higher frequency of MPNs with JAK2 mutation when compared to CALR mutation. The observed differences in prevalence may be influenced by the ability of HSCs carrying driver disease mutations to escape immune surveillance. It has been noted that certain healthy individuals possess memory T-cells that recognize the mutated CALR neoantigen; however, they do not exhibit CALR-mutated CHIP. This suggests that the lower prevalence of CALR-mutated CHIP could be attributed to a more efficient elimination of CALR-mutated cells at the pre-CHIP stage by the immune system, likely in a HLA-restricted manner (55). Indeed, it was demonstrated that several peptides capable of binding numerous MHC class I molecules originate from CALR and MPL mutations (56). However, in JAK2V617F mutation, peptides have only weak interactions with any HLA allotype, reducing their recognition by the immune system. Moreover, the activation of JAK/STAT signaling by JAK2V617F leads to increased expression of programmed death ligand 1 (PD-L1). This combination of factors allows cells expressing JAK2 mutation to evade immune surveillance (57).

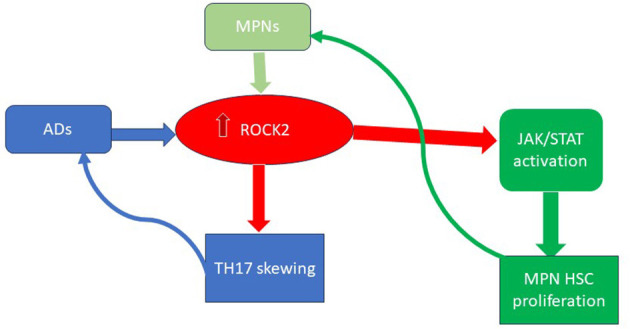

Additionally, uncontrolled inflammation could also promote CHIP or MPN development. The presence of IL-1β, an inflammatory cytokine, significantly promotes early clonal expansion in MPNs (58). Autoimmune diseases, such as systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), psoriasis, and arthritis, are also characterized by an overexpression of the Rho-associated coiled-coil containing protein kinase 2 (ROCK2). ROCK2 is a cytoplasmic serine/threonine kinase that can hyperactivate the JAK-STAT pathway. Interestingly, hyper-activation of ROCK2 has also been observed in myeloid malignancies, where it promotes the growth and survival of leukemic cells through the constitutive activation of the PI3K/Rho/ROCK/myosin light chain pathway (59, 60). Moreover, during the immune response, ROCK2 controls the TCR signaling and, through IL21 and IL17, sustains the TH17 generation, thus being implicated in the autoimmunity onset (see Figure 2) (61).

Figure 2.

The key role of ROCK2 activation in ADs and MPNs. ROCK2, Rho-associated coiled-coil containing protein kinase 2; MPN, myeloproliferative neoplasms; Ads, autoimmune diseases; HSC, hematopoietic stem cell.

5. Clonal hematopoiesis causes thrombosis through immune dysregulation

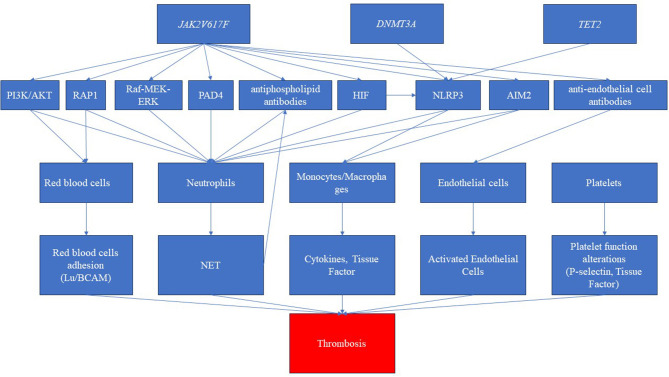

Clonal hematopoiesis, autoimmune diseases, and thrombotic manifestations are strictly linked to each other (17) (see Figure 3). However, the links among them are not well defined. The JAK2V617F mutation is correlated with a heightened risk of thrombosis, whereas CALR mutations are associated with a lower risk compared to JAK2 and MPL mutations (62, 63). Furthermore, in MPNs, the likelihood of experiencing thrombosis is influenced by the variant allele frequency (VAF) of JAK2V617F (64). Notably, patients with PV exhibited a higher incidence of thrombotic events. This difference may be attributed to the varying associations between specific driver gene mutations and thrombosis risk factors. Moreover, in a large population-based study, individuals with a personal history of autoimmunity exhibited a 20% higher risk of developing MPN, particularly in cases associated with vasculitis (65). The presence of an autoimmune disease remained an independent prognostic factor for thrombosis, even when considering the cardiovascular risk (HR 5.42) (66). This may suggest that specific mutations may be associated with alteration of the clonal cells (red blood cells, platelets, white blood cells, and endothelial cells) and the surrounding non-clonal environment, ultimately leading to thrombosis formation. First, for example, JAK2V617F mutation in red blood cells triggers signaling cascades that lead to the activation of RAS-related protein 1 (RAP1) and AKT, ultimately promoting the adhesion of red blood cells mediated by Lu/BCAM (67).

Figure 3.

Pathways related to clonal hematopoiesis involved in immune dysregulation and thrombosis. The disease driver mutation of Janus kinase (JAK2V617F) represents a pivotal trigger, inducing a cascade of intricate molecular pathways. These pathways encompass the activation of diverse routes such as phosphatidylinositol-3-kinase/AKT (PI3K/AKT), RAS-related protein 1 (RAP1), rapidly accelerated fibrosarcoma (Raf)/mitogen-activated protein kinase (MEK)/extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK), and hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF). Furthermore, this mutation elicits the activation of inflammasomes, notably NLR family pyrin domain containing 3 (NLRP3) and absent in melanoma 2 (AIM2), amplifying the inflammatory milieu. Simultaneously, the JAK mutation is associated with the production of autoantibodies, specifically antiphospholipid antibodies and anti-endothelial antibodies. Consequently, these intricate molecular perturbations culminate in the dysregulation of crucial blood cell populations. While red blood cells, platelets, and endothelial cells shift toward a procoagulant phenotype, neutrophils and monocytes produce neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs) and cytokines, respectively. This intricate interplay culminates in a pronounced prothrombotic state. Furthermore, the clonal driver mutations, particularly DNMT3 and TET2, have been shown to possess the capability to activate inflammasome pathways, further intensifying the prothrombotic environment.

In MPNs, different platelet function alterations have been observed, particularly in individuals with JAK2-mutated ET or a history of thrombosis (68). These abnormalities include increased levels of P-selectin and platelets positive for tissue factor (TF), some being specific to MPNs. These abnormalities are likely inherent to platelets derived from mutant stem cells; in fact, there is a correlation between the burden of JAK2 mutation and platelet activation (69). However, it is important to note that none of these platelet defects has been proven to be causative for clinical thrombosis. In fact, in MPNs, testing conditions can dramatically modify in vitro platelet function; conversely, analytical conditions closer to the physiological revealed normal/supranormal function (70).

The association between white blood cells and thrombosis highlights the primary role of leucocyte dysfunction in the genesis of thrombosis, mainly through neutrophils and monocytes. JAK2V617F expression is associated with neutrophil activation, in particular, with increased neutrophil extracellular trap (NET) formation, one of the major causes of cancer-associated thrombosis (71). JAK, through its activated pathways and regulatory molecules, such as STAT, AKT, and Raf-MEK-ERK, may regulate the NET formation both in normal neutrophils and neutrophils in pathological situations. In addition, in JAK2-mutated PV patients, peptidyl arginine deiminase (PAD4), HIF-mediated gene expression, and RAP1 were increased, leading to the production of NET (72–74). Moreover, RAP1 activates integrin signaling and enhances the adhesion of clonal neutrophils in PV. Interestingly, it was demonstrated that the inhibition of JAK2 signaling may reduce thrombosis in MPNs by the inhibition of NET formation (75, 76). As regards monocytes, JAK2-mutated macrophages showed increased expression of proinflammatory cytokines and chemokines, i.e., IL-1β, IL-6, iNOS, TNF-α, and MCP-1 (77, 78). The main contributors to cytokine production in monocytes are the inflammasome, as NLR Family Pyrin Domain Containing 3 (NLRP3) and Absent in Melanoma 2 (AIM2). AIM2 is a cytoplasmic sensor and is activated by dsDNA from bacterial, viral, or cellular origin (79). JAK2V617F mutation leads to metabolic and proliferative changes in macrophages resulting in replication stress. The presence of damaged oxidative DNA in hyperproliferative cells results in AIM2 activation. Simultaneously, an excess of HIF alters iron metabolism increasing cellular labile iron, thus inducing ROS, the activator of NLRP3 (80–82). The activation of both the inflammasomes leads to the massive production of IL-1β that ulteriorly promotes the NET formation and consequently thrombosis (83). Interestingly, the CANTOS trial demonstrated that canakinumab, a therapeutic monoclonal antibody targeting interleukin-1β, reduces recurrent cardiovascular events. The inflammasome, moreover, causes pyroptosis, a proinflammatory programmed cell death mediated by Gasdermin D. Inflammasome-mediated pyroptosis releases tissue factor from macrophages and activates coagulation (84, 85).

Focusing on vessels, endothelial cells (ECs) carrying the JAK2V617F mutation have been detected in patients with MPNs. Mesodermal pluripotent stem cells, indeed, have the capacity to differentiate into both hematopoietic and endothelial lineages (86, 87). In instances where vascular endothelial integrity is compromised, re-endothelialization can occur through the outgrowth of neighboring intact endothelium or by repopulating EC progenitors. Consequently, a somatic MPN driver mutation can be implanted in endothelium (88, 89) and the injury or activation of ECs leads to a shift in their properties, from anti- to pro-thrombotic. In vivo, activation of ECs in MPNs is reflected by elevated biomarkers like the von Willebrand factor (90).

The immune dysregulation in MPNs may involve adaptive immunity, in particular, autoantibody production, as demonstrated by a very high frequency of organ/non-organ specific antibodies (57%), anti-erythrocyte antibodies (45%), and anti-platelet antibodies (15%) (91). In PV patients, the JAK2V617F allele burden was correlated with anti-endothelial cell antibodies (AECAs) that are capable of recognizing activated endothelial cells resulting in thrombosis (92). Interestingly, a similar mechanism has been described in small vessel vasculitis (93).

There is a notable connection between JAK2V617F-mutated MPNs and definite antiphospholipid syndrome (APS), an autoimmune thrombotic syndrome caused by antiphospholipid antibodies (aPL). Both APS and MPNs exhibit significant upregulation of proinflammatory cytokines and an enhanced formation of NETs (94). In APS, the release of NETs is associated with the levels of antiphospholipid antibodies (aPL), and aPL can induce NETosis in neutrophils from healthy individuals (95). Moreover, aPL are also directed toward mitochondria (96). Notably, in PMF, a higher prevalence of mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) and anti-mitochondrial DNA (anti-mtDNA) was found (82). Furthermore, In SLE, it was demonstrated that anti-mitochondrial antibodies are associated with NET (97, 98). Overall, these findings highlight the strong interplay between JAK2V617F-mutated MPNs, APS, NET formation, and the dysregulation of proinflammatory cytokines, providing insights into the complex and interconnected nature of these conditions.

Finally, other mutations also can play a role in thrombosis pathogenesis. In patients with TET2 and DNMT3A clonal hematopoiesis, an inflammasome hyperactivation in myeloid cells was noticed, which represents the potential cause of cardiovascular disease (99, 100). TET2 mutation is not a standalone risk factor for thrombosis. The order of acquisition, whether it occurs first or after other mutations, is crucial. When TET2 mutation is acquired before JAK2 mutation, the thrombotic risk is higher (101).

6. Conclusion

The immune system has a primary role in clonal hematopoiesis development. Impaired immune surveillance and high inflammation (for example, by IL-1β and ROCK2 pathway) may facilitate CHIP occurrence. However, clonal hematopoiesis may directly alter the immune system, in particular, the neutrophils (NET formation), the macrophages (inflammasome and release of tissue factor), and the autoantibody production (anti-endothelial cell antibodies and antiphospholipid antibodies), leading to thrombosis. Interestingly, among the autoimmune diseases, CHIP is more prevalent in large vessel vasculitis and small vessel vasculitis, in which it is known to play the key role of, respectively, monocyte and neutrophil/NET formation (102–105). Furthermore, the most commonly associated autoimmune diseases with MPNs are vasculitis (65). With regard to autoantibodies, anti-endothelial cell antibodies are frequently detected in different autoimmune diseases, exhibiting a procoagulant effect by activating endothelial cells (106), as proven by the complex thrombotic action exerted by the antiphospholipid antibodies. Indeed, NET formation results in antibodies against mitochondria, including anti-phospholipid antibodies. These antibodies are frequently detected in systemic lupus erythematosus, and their pathogenetic association with thrombosis is clearly evident.

In summary, the presence of clonal hematopoiesis, with or without neoplasia, can be associated with autoimmune manifestations and thrombosis. In the presence of these manifestations, it seems necessary to consider a “disease-modifying therapy” that may reduce the clonal burden or inhibit the clonally activated JAK pathway. Recently, it has been shown that interferon may reduce clonal burden, while ruxolitinib, a JAK1/2 inhibitor, may inhibit the JAK-STAT pathway (107). Ultimately, the comprehension of the molecular pathogenesis of autoimmune and thrombotic manifestations provoked by clonal hematopoiesis might allow us a targeted therapy toward the era of precision medicine.

Author contributions

GF: Writing—original draft. CB: Writing—original draft. MM: Writing—review and editing. AP: Writing—review and editing. GB: Writing—review and editing. GP: Writing—review and editing. EC: Writing—review and editing. RC: Writing—review and editing. PM: Writing—review and editing. SG: Writing—review and editing.

Funding Statement

The project was funded under the National Recovery and Resilience Plan (NRRP), Mission 4 Component 2 Investment 1.5, The Tuscany Health Ecosystem (ECS—Ecosistema dell'innovazione sulle scienze e le tecnologie della vita in Toscana), HUB Tuscany Health Ecosystem Società Consortile a Responsabilità Limitata, SPOKE 7 Innovating Translational Medicine—Call for tender No. 3277 of DATE 30-12-2021 of Italian Ministry of University, and research was funded by the European Union—NextGenerationEU.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

- 1.Luque Paz D, Kralovics R, Skoda RC. Genetic basis and molecular profiling in myeloproliferative neoplasms. Blood. (2023) 141:1909–1921. 10.1182/blood.2022017578 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Arber DA, Orazi A, Hasserjian R, Thiele J, Borowitz MJ, Le Beau MM, et al. The 2016 revision to the World Health Organization classification of myeloid neoplasms and acute leukemia. Blood. (2016) 127:2391–405. 10.1182/blood-2016-03-643544 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gianelli U, Thiele J, Orazi A, Gangat N, Vannucchi AM, Tefferi A, et al. International consensus classification of myeloid and lymphoid neoplasms: myeloproliferative neoplasms. Virchows Arch. (2023) 482:53–68. 10.1007/s00428-022-03480-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Adamson JW, Fialkow PJ, Murphy S, Prchal JF, Steinmann L. Polycythemia vera: stem-cell and probable clonal origin of the disease. N Engl J Med. (1976) 295:913–6. 10.1056/NEJM197610212951702 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Williams N, Lee J, Mitchell E, Moore L, Baxter EJ, Hewinson J, et al. Life histories of myeloproliferative neoplasms inferred from phylogenies. Nature. (2022) 602:162–8. 10.1038/s41586-021-04312-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lundberg P, Takizawa H, Kubovcakova L, Guo G, Hao-Shen H, Dirnhofer S, et al. Myeloproliferative neoplasms can be initiated from a single hematopoietic stem cell expressing JAK2-V617F. J Exp Med. (2014) 211:2213–30. 10.1084/jem.20131371 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Palumbo GA, Stella S, Pennisi MS, Pirosa C, Fermo E, Fabris S, et al. The Role of New Technologies in Myeloproliferative Neoplasms. Front Oncol. (2019) 9:321. 10.3389/fonc.2019.00321 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Baxter EJ, Scott LM, Campbell PJ, East C, Fourouclas N, Swanton S, et al. Acquired mutation of the tyrosine kinase JAK2 in human myeloproliferative disorders. Lancet. (2005) 365:1054–61. 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)71142-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Klampfl T, Gisslinger H, Harutyunyan AS, Nivarthi H, Rumi E, Milosevic JD, et al. Somatic Mutations of Calreticulin in Myeloproliferative Neoplasms. N Engl J Med. (2013) 369:2379–90. 10.1056/NEJMoa1311347 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nangalia J, Massie CE, Baxter EJ, Nice FL, Gundem G, Wedge DC, et al. Somatic CALR mutations in myeloproliferative neoplasms with nonmutated JAK2. N Engl J Med. (2013) 369:2391–405. 10.1056/nejmoa1312542 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pikman Y, Lee BH, Mercher T, McDowell E, Ebert BL, Gozo M, et al. MPLW515L is a novel somatic activating mutation in myelofibrosis with myeloid metaplasia. PLoS Med. (2006) 3:e270. 10.1371/journal.pmed.0030270 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rampal R, Al-Shahrour F, Abdel-Wahab O, Patel JP, Brunel J-P, Mermel CH, et al. Integrated genomic analysis illustrates the central role of JAK-STAT pathway activation in myeloproliferative neoplasm pathogenesis. Blood. (2014) 123:e123–33. 10.1182/blood-2014-02-554634 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Veiga CB, Lawrence EM, Murphy AJ, Herold MJ, Dragoljevic D. Myelodysplasia syndrome, clonal hematopoiesis and cardiovascular disease. Cancers (Basel). (2021) 13:1968. 10.3390/cancers13081968 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Valent P. ICUS IDUS, CHIP and CCUS: diagnostic criteria, separation from MDS and clinical implications. Pathobiology. (2019) 86:30–8. 10.1159/000489042 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Desai P, Hassane D, Roboz GJ. Clonal hematopoiesis and risk of acute myeloid leukemia. Best Pract Res Clin Haematol. (2019) 32:177–85. 10.1016/j.beha.2019.05.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Constantinescu SN, Vainchenker W, Levy G, Papadopoulos N. Functional consequences of mutations in myeloproliferative neoplasms. Hemasphere. (2021) 5:e578. 10.1097/HS9.0000000000000578 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Asada S, Kitamura T. Clonal hematopoiesis and associated diseases: A review of recent findings. Cancer Sci. (2021) 112:3962–71. 10.1111/cas.15094 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Swierczek S, Prchal JT. Clonal hematopoiesis in hematological disorders: Three different scenarios. Exp Hematol. (2020) 83:57–65. 10.1016/j.exphem.2020.01.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Marnell CS, Bick A, Natarajan P. Clonal hematopoiesis of indeterminate potential (CHIP): Linking somatic mutations, hematopoiesis, chronic inflammation and cardiovascular disease. J Mol Cell Cardiol. (2021) 161:98–105. 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2021.07.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Steensma DP, Bejar R, Jaiswal S, Lindsley RC, Sekeres MA, Hasserjian RP, et al. Clonal hematopoiesis of indeterminate potential and its distinction from myelodysplastic syndromes. Blood. (2015) 126:9–16. 10.1182/blood-2015-03-631747 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jaiswal S, Ebert BL. Clonal hematopoiesis in human aging and disease. Science. (2019) 366:eaan4673. 10.1126/science.aan4673 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Savola P, Lundgren S, Keränen MAI, Almusa H, Ellonen P, Leirisalo-Repo M, et al. Clonal hematopoiesis in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Blood Cancer J. (2018) 8:69. 10.1038/s41408-018-0107-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ricard L, Hirsch P, Largeaud L, Deswarte C, Jachiet V, Mohty M, et al. Clonal haematopoiesis is increased in early onset in systemic sclerosis. Rheumatology. (2020) 59:3499–504. 10.1093/rheumatology/keaa282 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Arends CM, Weiss M, Christen F, Eulenberg-Gustavus C, Rousselle A, Kettritz R, et al. Clonal hematopoiesis in patients with anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody-associated vasculitis. Haematologica. (2020) 105:e264–7. 10.3324/haematol.2019.223305 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.David C, Duployez N, Eloy P, Belhadi D, Chezel J, Guern VL, et al. Clonal haematopoiesis of indeterminate potential and cardiovascular events in systemic lupus erythematosus (HEMATOPLUS study). Rheumatology. (2022) 61:4355–63. 10.1093/rheumatology/keac108 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Park J, An H, Lim J, Park IS, Kim MH, Kim JH, et al. Interplay between chronic inflammation and clonal haematopoiesis of indeterminate potential in Behçet's disease. Arthritis Res Ther. (2023) 25:33. 10.1186/s13075-023-03014-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Papo M, Friedrich C, Delaval L, de Boysson H, Viallard J-F, Bachmeyer C, et al. Myeloproliferative neoplasms and clonal haematopoiesis in patients with giant cell arteritis: a case–control and exploratory study. Rheumatology. (2022) 61:775–80. 10.1093/rheumatology/keab337 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jaiswal S, Natarajan P, Silver AJ, Gibson CJ, Bick AG, Shvartz E, et al. Clonal hematopoiesis and risk of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease. N Engl J Med. (2017) 377:111–21. 10.1056/NEJMoa1701719 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jaiswal S, Fontanillas P, Flannick J, Manning A, Grauman PV, Mar BG, et al. Age-related clonal hematopoiesis associated with adverse outcomes. N Engl J Med. (2014) 371:2488–98. 10.1056/NEJMoa1408617 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Moliterno AR, Kaizer H, Reeves BN. JAK2V617F allele burden in polycythemia vera: burden of proof. Blood. 141:1934–1942. 10.1182/blood.2022017697 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kralovics R, Passamonti F, Buser AS, Teo SS, Tiedt R, Passweg JR, et al. A gain-of-function mutation of JAK2 in myeloproliferative disorders. N Engl J Med. (2005) 352:1779–90. 10.1056/NEJMoa051113 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Levine RL, Wadleigh M, Cools J, Ebert BL, Wernig G, Huntly BJ, et al. Activating mutation in the tyrosine kinase JAK2 in polycythemia vera, essential thrombocythemia, and myeloid metaplasia with myelofibrosis. Cancer Cell. (2005) 7:387–97. 10.1016/j.ccr.2005.03.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.James C, Ugo V, Le Couédic JP, Staerk J, Delhommeau F, Lacout C, et al. A unique clonal JAK2 mutation leading to constitutive signalling causes polycythaemia vera. Nature. (2005) 434:1144–8. 10.1038/nature03546 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Vannucchi AM, Antonioli E, Guglielmelli P, Longo G, Pancrazzi A, Ponziani V, et al. Prospective identification of high-risk polycythemia vera patients based on JAK2V617F allele burden. Leukemia. (2007) 21:1952–9. 10.1038/sj.leu.2404854 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Vainchenker W, Kralovics R. Genetic basis and molecular pathophysiology of classical myeloproliferative neoplasms. Blood. (2017) 129:667–79. 10.1182/blood-2016-10-695940 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Marty C, Lacout C, Droin N, Le Couédic JP, Ribrag V, Solary E, et al. A role for reactive oxygen species in JAK2V617F myeloproliferative neoplasm progression. Leukemia. (2013) 27:2187–95. 10.1038/leu.2013.102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pedersen KM, Çolak Y, Ellervik C, Hasselbalch HC, Bojesen SE, Nordestgaard BG. Loss-of-function polymorphism in IL6R reduces risk of JAK2V617F somatic mutation and myeloproliferative neoplasm: A Mendelian randomization study. EClinicalMedicine. (2020) 21:100280. 10.1016/j.eclinm.2020.100280 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Marinaccio C, Suraneni P, Celik H, Volk A, Wen QJ, Ling T, et al. LKB1/STK11 is a tumor suppressor in the progression of myeloproliferative neoplasms. Cancer Discov. (2021) 11:1398–410. 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-20-1353 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chi J, Nicolaou KA, Nicolaidou V, Koumas L, Mitsidou A, Pierides C, et al. Calreticulin gene exon 9 frameshift mutations in patients with thrombocytosis. Leukemia. (2014) 28:1152–4. 10.1038/leu.2013.382 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Grisouard J, Shimizu T, Duek A, Kubovcakova L, Hao-Shen H, Dirnhofer S, et al. Deletion of Stat3 in hematopoietic cells enhances thrombocytosis and shortens survival in a JAK2-V617F mouse model of MPN. Blood. (2015) 125:2131–40. 10.1182/blood-2014-08-594572 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Huang Z, Richmond TD, Muntean AG, Barber DL, Weiss MJ, Crispino JD. STAT1 promotes megakaryopoiesis downstream of GATA-1 in mice. J Clin Invest. (2007) 117:3890–9. 10.1172/JCI33010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cattaneo D, Bucelli C, Marchetti A, Lionetti M, Fermo E, Bellani V, et al. Pathological and genomic features of myeloproliferative neoplasms associated with splanchnic vein thrombosis in a single-center cohort. Ann Hematol. (2023) 102:1409–20. 10.1007/s00277-023-05217-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sano S, Oshima K, Wang Y, Katanasaka Y, Sano M, Walsh K. CRISPR-mediated gene editing to assess the roles of Tet2 and Dnmt3a in clonal hematopoiesis and cardiovascular disease. Circ Res. (2018) 123:335–41. 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.118.313225 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Peng J, Yang Q, Li A-F, Li R-Q, Wang Z, Liu L-S, et al. Tet methylcytosine dioxygenase 2 inhibits atherosclerosis via upregulation of autophagy in ApoE-/- mice. Oncotarget. (2016) 7:76423–36. 10.18632/oncotarget.13121 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gumuser ED, Schuermans A, Cho SMJ, Sporn ZA, Uddin MM, Paruchuri K, et al. Clonal hematopoiesis of indeterminate potential predicts adverse outcomes in patients with atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease. J Am Coll Cardiol. (2023) 81:1996–2009. 10.1016/j.jacc.2023.03.401 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wang Z, Liu W, Wang D, Yang E, Li Y, Li Y, et al. TET2 mutation may be more valuable in predicting thrombosis in ET patients compared to PV patients: a preliminary report. J Clin Med. (2022) 11:6615. 10.3390/jcm11226615 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rungjirajittranon T, Owattanapanich W, Ungprasert P, Siritanaratkul N, Ruchutrakool T. A systematic review and meta-analysis of the prevalence of thrombosis and bleeding at diagnosis of Philadelphia-negative myeloproliferative neoplasms. BMC Cancer. (2019) 19:184. 10.1186/s12885-019-5387-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hasselbalch HC, Elvers M, Schafer AI. The pathobiology of thrombosis, microvascular disease, and hemorrhage in the myeloproliferative neoplasms. Blood. (2021) 137:2152–60. 10.1182/blood.2020008109 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Marchioli R, Finazzi G, Specchia G, Cacciola R, Cavazzina R, Cilloni D, et al. Cardiovascular events and intensity of treatment in polycythemia vera. N Engl J Med. (2013) 368:22–33. 10.1056/NEJMoa1208500 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Campbell PJ, MacLean C, Beer PA, Buck G, Wheatley K, Kiladjian J-J, et al. Correlation of blood counts with vascular complications in essential thrombocythemia: analysis of the prospective PT1 cohort. Blood. (2012) 120:1409–11. 10.1182/blood-2012-04-424911 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Warny M, Helby J, Birgens HS, Bojesen SE, Nordestgaard BG. Arterial and venous thrombosis by high platelet count and high hematocrit: 108 521 individuals from the Copenhagen general population study. J Thromb Haemost. (2019) 17:1898–911. 10.1111/jth.14574 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Buxhofer-Ausch V, Steurer M, Sormann S, Schloegl E, Schimetta W, Gisslinger B, et al. Impact of white blood cells on thrombotic risk in patients with optimized platelet count in essential thrombocythemia. Eur J Haematol. (2018) 101:131–5. 10.1111/ejh.13070 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Parasuraman S, Yu J, Paranagama D, Shrestha S, Wang L, Baser O, et al. Elevated white blood cell levels and thrombotic events in patients with polycythemia vera: a real-world analysis of veterans health administration data. Clin Lymph Myeloma Leuk. (2020) 20:63–9. 10.1016/j.clml.2019.11.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Carobbio A, Ferrari A, Masciulli A, Ghirardi A, Barosi G, Barbui T. Leukocytosis and thrombosis in essential thrombocythemia and polycythemia vera: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Blood Advances. (2019) 3:1729–37. 10.1182/bloodadvances.2019000211 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Holmström MO, Ahmad SM, Klausen U, Bendtsen SK, Martinenaite E, Riley CH, et al. High frequencies of circulating memory T cells specific for calreticulin exon 9 mutations in healthy individuals. Blood Cancer J. (2019) 9:8. 10.1038/s41408-018-0166-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Schischlik F, Jäger R, Rosebrock F, Hug E, Schuster M, Holly R, et al. Mutational landscape of the transcriptome offers putative targets for immunotherapy of myeloproliferative neoplasms. Blood. (2019) 134:199–210. 10.1182/blood.2019000519 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Prestipino A, Emhardt AJ, Aumann K, O'Sullivan D, Gorantla SP, Duquesne S, et al. Oncogenic JAK2 V617F causes PD-L1 expression, mediating immune escape in myeloproliferative neoplasms. Sci Transl Med. (2018) 10:eaam7729. 10.1126/scitranslmed.aam7729 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Rai S, Hansen N, Hao-Shen H, Dirnhofer S, Tata NR, Skoda RC. IL-1β Secreted from mutant cells carrying JAK2-V617Ffavors early clonal expansion and promotes MPN disease initiation and progression. Blood. (2019) 134:307–307. 10.1182/blood-2019-129800 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Galimberti S, Baldini C, Baratè C, Fornili M, Balducci S, Ricci F, et al. Myeloid neoplasms and autoimmune diseases: markers of association. Clin Exp Rheumatol. (2022) 40:49–55. 10.55563/clinexprheumatol/ddxmp9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Mali RS, Ramdas B, Ma P, Shi J, Munugalavadla V, Sims E, et al. Rho kinase regulates the survival and transformation of cells bearing oncogenic forms of KIT, FLT3, and BCR-ABL. Cancer Cell. (2011) 20:357–69. 10.1016/j.ccr.2011.07.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Chen W, Nyuydzefe MS, Weiss JM, Zhang J, Waksal SD, Zanin-Zhorov A. ROCK2, but not ROCK1 interacts with phosphorylated STAT3 and co-occupies TH17/TFH gene promoters in TH17-activated human T cells. Sci Rep. (2018) 8:16636. 10.1038/s41598-018-35109-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Lussana F, Caberlon S, Pagani C, Kamphuisen PW, Büller HR, Cattaneo M. Association of V617F Jak2 mutation with the risk of thrombosis among patients with essential thrombocythaemia or idiopathic myelofibrosis: A systematic review. Thromb Res. (2009) 124:409–17. 10.1016/j.thromres.2009.02.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Rotunno G, Mannarelli C, Guglielmelli P, Pacilli A, Pancrazzi A, Pieri L, et al. Impact of calreticulin mutations on clinical and hematological phenotype and outcome in essential thrombocythemia. Blood. (2014) 123:1552–5. 10.1182/blood-2013-11-538983 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Guglielmelli P, Loscocco GG, Mannarelli C, Rossi E, Mannelli F, Ramundo F, et al. JAK2V617F variant allele frequency >50% identifies patients with polycythemia vera at high risk for venous thrombosis. Blood Cancer J. (2021) 11:199. 10.1038/s41408-021-00581-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kristinsson SY, Landgren O, Samuelsson J, Bjorkholm M, Goldin LR. Autoimmunity and the risk of myeloproliferative neoplasms. Haematologica. (2010) 95:1216–20. 10.3324/haematol.2009.020412 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Krečak I, Holik H, Zekanović I, Morić-Perić M, Coha B, Gverić-Krečak V. Autoimmune disorders and the risk of thrombotic events in polycythaemia vera. Leuk Res. (2021) 110:106667. 10.1016/j.leukres.2021.106667 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.De Grandis M, Cambot M, Wautier M-P, Cassinat B, Chomienne C, Colin Y, et al. JAK2V617F activates Lu/BCAM-mediated red cell adhesion in polycythemia vera through an EpoR-independent Rap1/Akt pathway. Blood. (2013) 121:658–65. 10.1182/blood-2012-07-440487 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Schafer AI. Deficiency of platelet lipoxygenase activity in myeloproliferative disorders. N Engl J Med. (1982) 306:381–6. 10.1056/NEJM198202183060701 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Arellano-Rodrigo E, Alvarez-Larrán A, Reverter J-C, Colomer D, Villamor N, Bellosillo B, et al. Platelet turnover, coagulation factors, and soluble markers of platelet and endothelial activation in essential thrombocythemia: Relationship with thrombosis occurrence and JAK 2 V617F allele burden. Am J Hematol. (2009) 84:102–8. 10.1002/ajh.21338 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Lussana F, Femia EA, Pugliano M, Podda G, Razzari C, Maugeri N, et al. Evaluation of platelet function in essential thrombocythemia under different analytical conditions. Platelets. (2020) 31:179–86. 10.1080/09537104.2019.1584668 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Demers M, Krause DS, Schatzberg D, Martinod K, Voorhees JR, Fuchs TA, et al. Cancers predispose neutrophils to release extracellular DNA traps that contribute to cancer-associated thrombosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. (2012) 109:13076–81. 10.1073/pnas.1200419109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Marković DC, Maslovarić IS, Kovačić M, Vignjević Petrinović S, Ilić VLJ. Putative role of neutrophil extracellular trap formation in chronic myeloproliferative neoplasms. IJMS. (2023) 24:4497. 10.3390/ijms24054497 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Edelmann B, Gupta N, Schnoeder TM, Oelschlegel AM, Shahzad K, Goldschmidt J, et al. JAK2-V617F promotes venous thrombosis through β1/β2 integrin activation. J Clin Invest. (2018) 128:4359–71. 10.1172/JCI90312 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Gangaraju R, Song J, Kim SJ, Tashi T, Reeves BN, Sundar KM, et al. Thrombotic, inflammatory, and HIF-regulated genes and thrombosis risk in polycythemia vera and essential thrombocythemia. Blood Advances. (2020) 4:1115–30. 10.1182/bloodadvances.2019001379 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Wolach O, Sellar RS, Martinod K, Cherpokova D, McConkey M, Chappell RJ, et al. Increased neutrophil extracellular trap formation promotes thrombosis in myeloproliferative neoplasms. Sci Transl Med. (2018) 10:eaan8292. 10.1126/scitranslmed.aan8292 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Huang SUS, O'Sullivan KM. The expanding role of extracellular traps in inflammation and autoimmunity: the new players in casting dark webs. Int J Mol Sci. (2022) 23:3793. 10.3390/ijms23073793 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Wang W, Liu W, Fidler T, Wang Y, Tang Y, Woods B, et al. Macrophage inflammation, erythrophagocytosis, and accelerated atherosclerosis in Jak2 V617F Mice. Circ Res. (2018) 123:e35–e47. 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.118.313283 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Longhitano L, Li Volti G, Giallongo C, Spampinato M, Barbagallo I, Di Rosa M, et al. The role of inflammation and inflammasome in myeloproliferative disease. J Clin Med. (2020) 9:2334. 10.3390/jcm9082334 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Wang B, Yin Q. AIM2 inflammasome activation and regulation: A structural perspective. J Struct Biol. (2017) 200:279–82. 10.1016/j.jsb.2017.08.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Ginzburg YZ, Feola M, Zimran E, Varkonyi J, Ganz T, Hoffman R. Dysregulated iron metabolism in polycythemia vera: etiology and consequences. Leukemia. (2018) 32:2105–16. 10.1038/s41375-018-0207-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Liu D, Xu Z, Zhang P, Qin T, Li B, Qu S, et al. Iron deficiency in JAK2 exon12 and JAK2-V617F mutated polycythemia vera. Blood Cancer J. (2021) 11:154. 10.1038/s41408-021-00552-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Nakamura K, Kawakami T, Yamamoto N, Tomizawa M, Fujiwara T, Ishii T, et al. Activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome by cellular labile iron. Exp Hematol. (2016) 44:116–24. 10.1016/j.exphem.2015.11.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Liberale L, Holy EW, Akhmedov A, Bonetti NR, Nietlispach F, Matter CM, et al. Interleukin-1β mediates arterial thrombus formation via NET-associated tissue factor. JCM. (2019) 8:2072. 10.3390/jcm8122072 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Cho JH, Feldman M. Heterogeneity of autoimmune diseases: pathophysiologic insights from genetics and implications for new therapies. Nat Med. (2015) 21:730–8. 10.1038/nm.3897 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Yu P, Zhang X, Liu N, Tang L, Peng C, Chen X. Pyroptosis: mechanisms and diseases. Signal Transduct Target Ther. (2021) 6:128. 10.1038/s41392-021-00507-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Kobayashi I, Kobayashi-Sun J, Hirakawa Y, Ouchi M, Yasuda K, Kamei H, et al. Dual role of Jam3b in early hematopoietic and vascular development. Development. (2020) 147:dev181040. 10.1101/656108 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Zhang Q, Cannavicci A, Kutryk MJB. Exploring endothelial colony-forming cells to better understand the pathophysiology of disease: an updated review. Stem Cells Int. (2022) 2022:1–14. 10.1155/2022/4460041 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Itoh Y, Toriumi H, Yamada S, Hoshino H, Suzuki N. Resident endothelial cells surrounding damaged arterial endothelium reendothelialize the lesion. ATVB. (2010) 30:1725–32. 10.1161/ATVBAHA.110.207365 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Guadall A, Lesteven E, Letort G, Awan Toor S, Delord M, Pognant D, et al. Endothelial cells harbouring the JAK2V617F mutation display pro-adherent and pro-thrombotic features. Thromb Haemost. (2018) 118:1586–99. 10.1055/s-0038-1667015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Krüger-Genge B, Franke J. Vascular endothelial cell biology: an update. IJMS. (2019) 20:4411. 10.3390/ijms20184411 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Barcellini W, Iurlo A, Radice T, Imperiali FG, Zaninoni A, Fattizzo B, et al. Increased prevalence of autoimmune phenomena in myelofibrosis: Relationship with clinical and morphological characteristics, and with immunoregulatory cytokine patterns. Leuk Res. (2013) 37:1509–15. 10.1016/j.leukres.2013.09.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Cacciola R, Gentilini Cacciola E, Vecchio V, Cacciola E. Impact of anti-endothelial cell antibodies (AECAs) in patients with polycythemia vera and thrombosis. Diagnostics. (2022) 12:1077. 10.3390/diagnostics12051077 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Misra DP, Thomas KN, Gasparyan AY, Zimba O. Mechanisms of thrombosis in ANCA-associated vasculitis. Clin Rheumatol. (2021) 40:4807–15. 10.1007/s10067-021-05790-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Janjetovic S, Beckmann L, Holstein K, Rolling C, Thiele B, Schafhausen P, et al. Prevalence of definite antiphospholipid syndrome in carriers of the JAK2V617F mutation. Thromb Res. (2021) 198:55–61. 10.1016/j.thromres.2020.11.027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Yalavarthi S, Gould TJ, Rao AN, Mazza LF, Morris AE, Núñez-Álvarez C, et al. Release of neutrophil extracellular traps by neutrophils stimulated with antiphospholipid antibodies: a newly identified mechanism of thrombosis in the antiphospholipid syndrome: release of NETs by neutrophils stimulated with aPL. Arthr Rheumatol. (2015) 67:2990–3003. 10.1002/art.39247 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Colapietro F, Lleo A, Generali E. Antimitochondrial antibodies: from bench to bedside. Clinic Rev Allerg Immunol. (2021) 63:166–77. 10.1007/s12016-021-08904-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Wang H, Li T, Chen S, Gu Y, Ye S. Neutrophil extracellular trap mitochondrial DNA and its autoantibody in systemic lupus erythematosus and a proof-of-concept trial of metformin: NET mtDNA and metformin in SLE. Arthr Rheumatol. (2015) 67:3190–200. 10.1002/art.39296 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Becker YLC, Duvvuri B, Fortin PR, Lood C, Boilard E. The role of mitochondria in rheumatic diseases. Nat Rev Rheumatol. (2022) 18:621–40. 10.1038/s41584-022-00834-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Belizaire R, Wong WJ, Robinette ML, Ebert BL. Clonal haematopoiesis and dysregulation of the immune system. Nat Rev Immunol. (2023) 23:595–610. 10.1038/s41577-023-00843-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Baldini C, Moriconi FR, Galimberti S, Libby P, De Caterina R. The JAK–STAT pathway: an emerging target for cardiovascular disease in rheumatoid arthritis and myeloproliferative neoplasms. Eur Heart J. (2021) 42:4389–400. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehab447 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Ortmann CA, Kent DG, Nangalia J, Silber Y, Wedge DC, Grinfeld J, et al. Effect of mutation order on myeloproliferative neoplasms. N Engl J Med. (2015) 372:601–12. 10.1056/NEJMoa1412098 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Akiyama M, Ohtsuki S, Berry GJ, Liang DH, Goronzy JJ, Weyand CM. Innate and adaptive immunity in giant cell arteritis. Front Immunol. (2021) 11:621098. 10.3389/fimmu.2020.621098 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Watanabe R, Hashimoto M. Pathogenic role of monocytes/macrophages in large vessel vasculitis. Front Immunol. (2022) 13:859502. 10.3389/fimmu.2022.859502 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Nakazawa D, Masuda S, Tomaru U, Ishizu A. Pathogenesis and therapeutic interventions for ANCA-associated vasculitis. Nat Rev Rheumatol. (2019) 15:91–101. 10.1038/s41584-018-0145-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Kessenbrock K, Krumbholz M, Schönermarck U, Back W, Gross WL, Werb Z, et al. Netting neutrophils in autoimmune small-vessel vasculitis. Nat Med. (2009) 15:623–5. 10.1038/nm.1959 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Legendre P, Régent A, Thiebault M, Mouthon L. Anti-endothelial cell antibodies in vasculitis: A systematic review. Autoimmun Rev. (2017) 16:146–53. 10.1016/j.autrev.2016.12.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.How J, Garcia JS, Mullally A. Biology and therapeutic targeting of molecular mechanisms in MPN. Blood. (2023) 141:1922–1933. 10.1182/blood.2022017416 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]