Abstract

Background

People with multiple sclerosis (MS) often report dietary modifications; however, evidence on functional outcomes remains sparse.

Objective

Evaluate the impact of the low-saturated fat (Swank) and modified Paleolithic elimination (Wahls) diets on functional disability among people with relapsing-remitting MS.

Methods

Baseline-referenced MS functional composite (MSFC) scores were calculated from nine-hole peg-test (NHPT), timed 25-foot walk, and oral symbol digit modalities test (SDMT-O) collected at four study visits: (a) run-in, (b) baseline, (c) 12 weeks, and (d) 24 weeks. Participants were observed at run-in and then randomized at baseline to either the Swank (n = 44) or Wahls (n = 43) diets.

Results

Among the Swank group, MSFC scores significantly increased from −0.13 ± 0.14 at baseline to 0.10 ± 0.11 at 12 weeks (p = 0.04) and 0.14 ± 0.11 at 24 weeks (p = 0.02). Among the Wahls group, no change in MSFC scores was observed at 12 weeks from 0.10 ± 0.11 at baseline but increased to 0.28 ± 0.13 at 24 weeks (p = 0.002). In both groups, NHPT and SDMT-O z-scores increased at 24 weeks. Changes in MSFC and NHPT were mediated by fatigue.

Discussion

Both diets reduced functional disability as mediated by fatigue.

Trial Registration

Clinicaltrials.gov Identifier: NCT02914964

Keywords: Multiple sclerosis, diet, low-saturated fat, modified Paleolithic elimination, physical and cognitive function, disability, fatigue

Introduction

People with multiple sclerosis (MS) express interest in using dietary strategies to improve their wellness, 1 with approximately half reporting modifying their diets. 2 However, clinicians are reluctant to provide dietary information to their patients with MS 3 due, in part, to a lack of evidence for the effect of diet on MRI-based disease activity and progression and unknown mechanisms by which diet impacts the disease course.4–6 This has led to people with MS not receiving the clinical resources and support they desire for improving their diets. 7 Instead, people with MS likely rely on dietary information obtained from online sources 8 which may not be based on evidence. 9

Recently, two meta-analyses of randomized dietary intervention trials found a significant impact of dietary interventions on fatigue and quality of life among people with MS.10,11 One of these meta-analyses 10 resulted in members of the Nutrition Workgroup of the National MS Society recommending a healthy diet as an adjunct therapy for people with MS. 12 However, significant questions remain as the other recent meta-analysis additionally investigated the effect of dietary interventions on disability status and observed a standardized mean difference (95% confidence interval (CI)) of −0.19 (−0.40, 0.03) for the effect of dietary interventions on Expanded Disability Status Scale (EDSS) values. 11 Given this null finding, more research is needed to fully elucidate the impact of dietary interventions on disability among people with MS.

Two popular diets in the MS community are the low-saturated fat (Swank) and modified Paleolithic elimination (Wahls) diets.2,13 In a randomized parallel-arm (WAVES) trial comparing these two diets among people with relapsing-remitting MS (RRMS), both diet groups experienced statistically and clinically significant reductions in fatigue and improvements in quality of life. 14 Participants also completed the nine-hole peg-test (NHPT), timed 25-foot walk (T25FW), and oral symbol digit modalities test (SDMT-O), 15 which are components of the MS functional composite (MSFC), 16 an objective measure of functional disability in MS 17 that correlates well with the EDSS. 18 A recent retrospective analysis observed an association between higher Mediterranean diet adherence and decreased functional disability as assessed by the MSFC 19 ; however, prospective studies investigating the effect of dietary intervention on the MSFC are sparse and limited by methodological or reporting issues.20–24 Therefore, the objectives of this secondary analysis of the WAVES trial were to evaluate the effects of the Swank and Wahls diets on functional disability and explore the influence of fatigue on changes in functional disability among individuals with RRMS.

Participants and methods

Participants

This is a secondary analysis of a 36-week, randomized, parallel-arm, single-blinded trial conducted at the University of Iowa showing that both the Swank and Wahls diets cause significant improvements in quality of life and reductions in fatigue. 14 Study activities took place from August 2016 to January 2020. The University of Iowa Institutional Review Board approved the trial which followed the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) reporting guidelines. Written and informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Participants aged 18–70 years were recruited from Iowa City, IA and the surrounding area. Briefly, participants were eligible for the trial if they: (a) had neurologist-confirmed RRMS based on the 2010 McDonald Criteria, 25 (b) had fatigue severity scale (FSS) ≥ 4.0, (c) were able to walk 25 feet with unilateral or no support, (d) were not pregnant nor planning to become pregnant, and (e) were willing to comply with all study procedures. Major exclusion criteria included: (a) MS relapse, change in disease-modifying drug therapy, or change medication for symptom management within the previous 12 weeks; (b) BMI <19 kg/m2; (c) severe cognitive impairment as determined by the short portable mental health questionnaire 26 ; (d) self-reported adverse reactions to gluten-containing foods; (e) diagnosed with or treated for major comorbidities as detailed in the trial protocol. 15

Study procedures

Data collection occurred during four study visits, each spaced 12 weeks apart: (a) run-in, (b) baseline, (c) 12 weeks, and (d) 24 weeks. Participants were randomized 1:1 at baseline to either the Swank or Wahls diets using password-protected randomization tables, which were accessible only by the study registered dietitian nutritionists (RDNs) who randomized participants. Study diet behavioral theory-based education was provided by the study RDNs, who also provided support consisting of two in-person and five telephone behavioral theory-based nutrition counseling sessions for the first 12 weeks of the intervention. During the second half of follow-up, RDN support was discontinued, but participants could still contact the RDNs any time for support or assistance.

Study diets

The composition of both diets has been reviewed in detail elsewhere. 13 Briefly, the Swank diet limits saturated fat to ≤15 g per day and provides 20–50 g of unsaturated fat, four servings of grains, and four servings of fruits and vegetables (FV) per day. The Wahls diet recommends 6–9 servings of FV and 6–12 ounces of meat per day. All grains, legumes, eggs, and dairy foods are excluded from the Wahls diet. Nightshade vegetables were also excluded between the baseline and the 12-week timepoint, and then reintroduced between the 12-week and 24-week timepoints. Participants were emailed personalized feedback on their diet-specific checklists every 4 weeks from the study RDN to encourage adherence to their assigned study diet, which was previously reported as 80% adherence among the Wahls diet group and 87% among the Swank group based on analysis of 3-day weighed food records at 12 weeks. 14 Participants in both groups were instructed to maintain the same level of physical activity and provided the same supplement regimen to eliminate potential confounding effects from differing regimens. 15

Outcomes

The results for the FSS, 6-min walk test (6MWT), and SDMT-O have been published previously.14,27 For this secondary analysis, the MSFC was used as a quantitative objective assessment of functional disability. 28 The MSFC is comprised of the T25FW, NHPT, and SDMT-O. The T25FW evaluates ambulation and the NHPT evaluates manual dexterity. 29 The SDMT-O was included in the MSFC as it is easier to administer and has similar reliability and better validity over the paced auditory serial addition test. 16 All outcomes were collected using standardized procedures by masked assessors. MSFC scores were determined for all participants using standard scoring procedures 28 with the modification to include the SDMT-O. 16 Baseline-referenced z-scores were calculated for each MSFC component using the baseline mean and standard deviation values of the entire study sample and averaged into an MSFC score. Increases in MSFC scores indicate reductions in functional disability. Clinically meaningful changes were defined as a ≥ 8-point increase in the number correct for the SDMT-O, 30 ≥20% reductions in time for the NHPT and T25FW, 29 and a ≥0.5-point increase in MSFC score. 31

Statistical analysis

The trial was powered to detect within- and between-group differences in FSS (the primary outcome) which also provided 90% power for secondary outcomes including the NHPT, T25FW, and SDMT-O 15 ; however, no a priori power calculation was conducted for the MSFC. Descriptive statistics were calculated for every variable at enrollment using frequencies, means ± standard error, and medians (interquartile range). Distributions of continuous variables were evaluated for normality by graphical observation, and outliers were checked for accuracy.

Generalized linear mixed models (GLMMs) 32 were used to estimate and test the interacting effects of diet and time on outcome measures while accounting for repeated measures for each participant using a random effect. Models for outcomes with normal and right-skewed distributions specified identity and log link functions, respectively. Other potentially important variables (age, sex, BMI, smoking status, alcohol consumption, walking assistance, years since MS diagnosis, disease-modifying drug use, baseline vitamin D, baseline 6MWT distance, educational attainment) were considered for inclusion in each model to assess their relationship with the outcome and obtain the modified estimates for the diet and time effects. For each unique model (outcome and predictor set combination), the Akaike information criterion (AIC) 33 was calculated for model selection. For each outcome, the model with the smallest AIC was deemed the optimal predictor set for estimating each adjusted relationship. Point estimates, 95% CIs, and p-values of the group-specific mean changes in outcome measures over visits were generated for each optimal model.

Due to the use of baseline values for z-score calculations, the run-in visit was excluded from analyses of MSFC scores and component z-scores. For primary MSFC analysis, data from all participants completing 12- and 24-week assessments were included. Additional analyses were conducted for the NHPT, T25FW, and SDMT-O z-scores and raw values. The two-item MSFC (MSFC-2), which excludes the SDMT-O, was also assessed to confirm findings while limiting bias from potential practice effects due to the frequent SDMT-O assessments. 34 Furthermore, a sensitivity analysis including only participants who were adherent to their assigned diet was conducted. The proportion of participants in each group exceeding thresholds for clinically significant changes was compared using Fisher's exact tests. The relationship between fatigue and functional outcomes was explored with additional GLMM models, spearman's rank correlation analyses, and causal mediation analyses.

All analyses were conducted with two-sided tests (α = 0.05) using SAS software (version 9.4, SAS Institute, Inc.).

Results

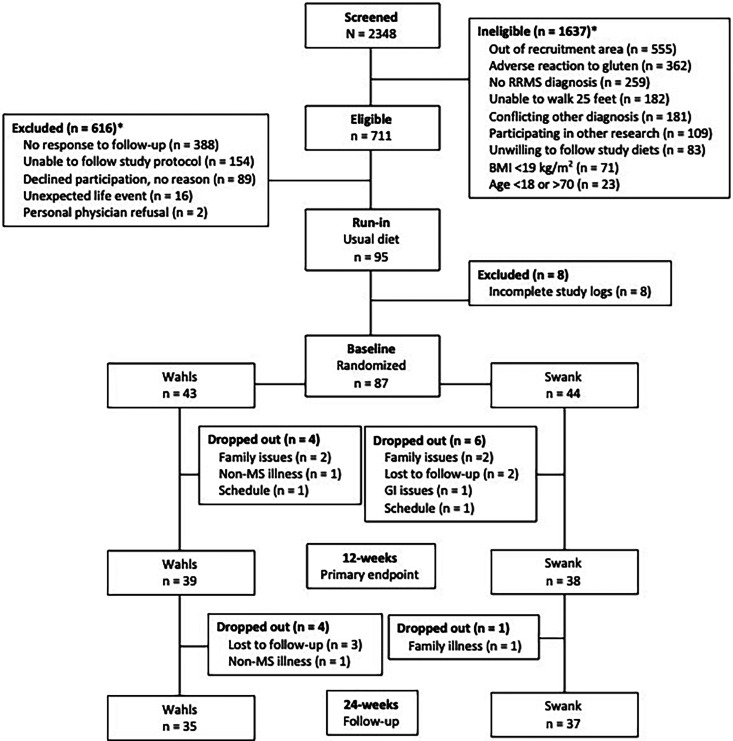

This secondary analysis included 77 participants (39 Wahls and 38 Swank) who completed the primary study endpoint at 12 weeks and 72 participants (35 Wahls and 37 Swank) who completed follow-up to 24 weeks (Figure 1). At baseline, no differences in demographics, disease status, or lifestyle characteristics were observed between groups (Table 1).

Figure 1.

Study recruitment and participant flow diagram. Ineligibility or exclusion counts may not add up to the sum of ineligible or excluded because some participants were found ineligible or were excluded for multiple reasons. Adapted with permission. 15

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of participants who completed a 12-week intervention of the LSF or MPE diets a .

| Characteristics | LSF | MPE | P-value b |

|---|---|---|---|

| N | 38 | 39 | - |

| Age (years) | 46.9 ± 1.7 | 46.4 ± 1.5 | 0.84 |

| Sex (female) | 35 (92.1) | 32 (82.1) | 0.31 |

| MS duration (years) | 12.1 ± 1.6 | 9.3 ± 1.0 | 0.14 |

| Disease-modifying drug use | 0.83 | ||

| None | 13 | 10 | |

| Oral | 11 | 11 | |

| Injectable | 10 | 12 | |

| Infused | 4 | 6 | |

| Race (Caucasian) | 36 (94.7) | 38 (97.4) | 0.99 |

| Education | 0.32 | ||

| High school | 0 (0.0) | 3 (7.7) | - |

| Some college | 12 (31.6) | 10 (25.6) | - |

| 4-year degree | 11 (28.9) | 8 (20.5) | - |

| Advanced degree | 15 (39.5) | 18 (46.2) | - |

| Smoking status | 0.13 | ||

| Never | 29 (76.3) | 23 (59.0) | - |

| Former | 3 (7.9) | 2 (5.1) | - |

| Current | 6 (15.8) | 14 (35.9) | - |

| Alcohol drinks per month c | 0.99 | ||

| None | 6 (15.8) | 7 (17.9) | - |

| Within recommendations | 29 (76.3) | 29 (74.4) | - |

| Above recommendations | 3 (7.9) | 3 (7.7) | - |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 27.6 ± 0.94 | 30.2 ± 1.3 | 0.11 |

| 6-min walk distance (meters) | 481 ± 16.3 | 459 ± 10.3 | 0.40 |

| Walking assistive device used (y) | 5 (13.2) | 4 (10.3) | 0.73 |

| Serum vitamin D (nmol/L) | 47.9 ± 3.9 | 50.9 ± 3.2 | 0.55 |

Data are shown as mean ± SEM or N (%). There were no significant differences in baseline values between groups. Adapted with permission. 15

Significance determined by Fisher's exact or two-sample t-tests.

Alcohol recommendations defined as ≤ 1 standard drink per day for females and ≤ 2 standard drinks per day for males.

There were no significant differences between groups at any time point for any outcome. The increase in MSFC scores from baseline values (−0.13 ± 0.14) to values at 12 weeks (0.10 ± 0.11) and 24 weeks (0.14 ± 0.11) were significant (p = 0.04 and p = 0.02, respectively) in the Swank group (Table 2). For the Wahls group, no changes in MSFC scores from baseline values (0.10 ± 0.11) were observed at 12 weeks (0.16 ± 0.10) but were at 24 weeks (0.28 ± 0.13; p = 0.002). Findings for the MSFC-2 were attenuated in the Swank group but values were significantly higher in the Wahls group at 12 and 24 weeks compared to baseline. For the individual components of the MSFC, NHPT z-scores increased from −0.19 ± 0.16 at baseline to 0.07 ± 0.17 at 24 weeks in the Swank diet group (p < 0.001). Similarly, NHPT z-scores increased from 0.20 ± 0.15 at baseline to 0.47 ± 0.18 at 24 weeks in the Wahls diet group (p = 0.003). No changes in NHPT z-scores were observed at 12 weeks. Among the Swank diet group, SDMT-O z-scores increased from −0.08 ± 0.16 at baseline to 0.26 ± 0.16 at 12 weeks (p < 0.001) and 0.22 ± 0.17 at 24 weeks (p = 0.009). No changes in SDMT-O z-scores from baseline values (0.04 ± 0.16) were observed at 12 weeks (0.13 ± 0.16) but were at 24 weeks (0.28 ± 0.19; p = 0.02) among the Wahls group. There were no significant within-group changes observed for T25FW z-scores at 12 or 24 weeks for either group.

Table 2.

Optimal model multiple sclerosis functional composite scores among participants with RRMS assigned to the Swank low-saturated fat and Wahls modified Paleolithic elimination dietary interventionsa,b.

| Study visit | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcome | Unit | Run-in | Baseline | 12 weeks | 24 weeks |

| Swank | |||||

| MSFC | score | NA c | −0.13 ± 0.14 | 0.10 ± 0.11* | 0.14 ± 0.11* |

| -NHPT | z-score | NA c | −0.19 ± 0.16 | −0.06 ± 0.17 | 0.07 ± 0.17*** |

| -SDMT-O | z-score | NA c | −0.08 ± 0.16 | 0.26 ± 0.16*** | 0.22 ± 0.17** |

| -T25FW d | z-score | NA c | −0.14 ± 0.23 | 0.06 ± 0.06 | 0.09 ± 0.06 |

| MSFC-2 | score | NA c | -0.15 ± 0.17 | 0.02 ± 0.11 | 0.10 ± 0.11 |

| NHPT e | seconds | 20.9 ± 0.14 | 20.6 ± 0.15 | 20.3 ± 0.14 | 20.0 ± 0.14 |

| SDMT-O | number correct | 57.8 ± 1.61* | 60.4 ± 1.51 | 63.3 ± 1.52*** | 62.9 ± 1.60** |

| T25FW f | seconds | 3.95 ± 0.30 | 4.48 ± 0.40 | 3.68 ± 0.25 | 3.64 ± 0.25 |

| 6MWT | meters | 460 ± 19.1 | 481 ± 16.3 | 485 ± 15.7 | 491 ± 16.6 |

| Wahls | |||||

| MSFC | score | NA c | 0.10 ± 0.11 | 0.16 ± 0.10 | 0.28 ± 0.13** |

| -NHPT | z-score | NA c | 0.20 ± 0.15 | 0.26 ± 0.14 | 0.47 ± 0.18** |

| -SDMT-O | z-score | NA c | 0.04 ± 0.16 | 0.13 ± 0.16 | 0.28 ± 0.19* |

| -T25FW d | z-score | NA c | 0.04 ± 0.09 | 0.09 ± 0.08 | 0.06 ± 0.11 |

| MSFC-2 | score | NA c | 0.13 ± 0.10 | 0.19 ± 0.09* | 0.28 ± 0.12* |

| NHPT e | seconds | 18.9 ± 0.17 | 18.3 ± 0.17 | 18.1 ± 0.16 | 17.5 ± 0.16* |

| SDMT-O | number correct | 60.2 ± 1.43 | 61.2 ± 1.53 | 62.0 ± 1.55 | 63.5 ± 1.83* |

| T25FW f | seconds | 3.84 ± 0.27 | 3.90 ± 0.27 | 3.71 ± 0.26 | 3.80 ± 0.26 |

| 6MWT | meters | 468 ± 19.3 | 459 ± 10.3 | 468 ± 20.3 | 495 ± 18.7** |

All values mean ± SEM with z-scores referenced to the full sample at baseline. * indicates statistical significance compared to baseline values (p≤ 0.05), ** indicates statistical significance compared to baseline values (p≤ 0.01), *** indicates statistical significance compared to baseline values (p≤ 0.001) as determined by optimal general linear mixed models according to AIC. Optimal models for outcomes without superscript letters did not include covariate adjustment based on AIC values.

Abbreviations: MSFC = multiple sclerosis functional composite; MSFC-2 = 2-item MSFC; NA = not applicable; NHPT = nine-hole peg test; SDMT-O = symbol digit modalities test – oral; T25FW = timed 25-foot walk; 6MWT = 6-min walk test.

Run-in values omitted as MSFC scores and component z-scores were calculated using baseline values.

Model adjusted for alcohol consumption.

Model adjusted for age and BMI.

Model adjusted for age, years with MS, and alcohol consumption.

The interpretation of findings did not differ in analyses of raw values other than the statistically significant improvement in NHPT at 24 weeks that was no longer observed in the Swank group (Table 2). No differences were observed between run-in and baseline values among the Wahls diet group, but the Swank diet group had a statistically significant pre-intervention increase in SDMT-O correct responses. Interpretation of unadjusted results did not change for variables with covariates included in the optimal model (Supplemental Table 1). Findings for the MSFC, NHPT, SDMT-O, and T25FW were consistent in a sensitivity analysis excluding participants who were not adherent to their assigned diet (Supplemental Table 2). Inclusion of walking assistance device use as a covariate in models did not change the interpretation of results for T25FW z-scores or raw values (data not shown).

MSFC 24-week changes were significantly correlated with 24-week changes in the NHPT (rs = -0.61; p < 0.001), SDMT-O (rs = 0.74; p < 0.001), T25FW (rs = -0.34; p = 0.004), and 6MWT (rs = 0.32; p = 0.007) but not with FSS (rs = -0.08; p = 0.48; Table 3). In addition, 24-week changes in the 6MWT were correlated with 24-week changes in the T25FW (rs = -0.54; p < 0.001). Inclusion of FSS values as a covariate in models completely attenuated all significant results for all outcomes (data not shown). Causal mediation analysis showed that 24-week changes in FSS significantly mediated the effect of the dietary interventions on MSFC, NHPT, 6MWT with significant indirect effects (95% CIs) of 0.16 (0.02, 0.31) for MSFC, −2.03 (−3.55, −0.50) for NHPT, and 34.9 (12.3, 57.5) for 6MWT (Table 4).

Table 3.

Spearman rank correlation between 24-week changes from baseline for fatigue and functional outcomes a , b .

| FSS | MSFC | NHPT | SDMT-O | T25FW | 6MWT | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FSS | 1.00 | −0.08 (0.48) | −0.01 (0.91) | −0.20 (0.11) | 0.09 (0.46) | −0.23 (0.07) |

| MSFC | 1.00 | −0.61 (<0.001) | 0.74 (<0.001) | −0.34 (0.004) | 0.32 (0.007) | |

| NHPT | 1.00 | −0.07 (0.59) | 0.19 (0.12) | −0.18 (0.15) | ||

| SDMT-O | 1.00 | −0.08 (0.53) | 0.19 (0.13) | |||

| T25FW | 1.00 | −0.54 (<0.001) | ||||

| 6MWT | 1.00 |

Spearman rank correlation coefficients shown as rs (p-value).

Abbreviations: FSS = fatigue severity scale; MSFC = multiple sclerosis functional composite; NHPT = nine-hole peg-test; SDMT-O = oral symbol digit modalities test; T25FW = timed 25-foot walk; 6MWT = 6-min walk test.

Table 4.

Causal mediation analysis for the effect of 24-week changes in fatigue on 24-week changes in functional outcomes.

| Total effect | Direct effect | Indirect effect | Percentage mediated | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Effect size (95% CI) | p-value | Effect size (95% CI) | p-value | Effect size (95% CI) | p-value | ||

| MSFC | 0.22 (−0.03, 0.46) | 0.09 | 0.05 (−0.22, 0.32) | 0.98 | 0.16 (0.02, 0.31) | 0.02 | 76.2% |

| NHPT | −0.82 (−3.31, 1.68) | 0.52 | 1.21 (−1.51, 3.93) | 0.38 | −2.03 (−3.55, −0.50) | 0.009 | 249% |

| SDMT-O | 2.44 (−0.72, 5.61) | 0.13 | 0.60 (−2.95, 4.16) | 0.74 | 1.84 (−0.03, 3.71) | 0.06 | 75.3% |

| T25FW | −0.62 (−1.86, 0.62) | 0.33 | −0.33 (−1.72, 1.06) | 0.64 | −0.29 (−0.96, 0.38) | 0.40 | 46.8% |

| 6MWT | 22.7 (−13.2, 58.4) | 0.22 | −12.2 (−50.1, 25.6) | 0.35 | 34.9 (12.3, 57.5) | 0.003 | 154% |

Abbreviations: MSFC = multiple sclerosis functional composite; NHPT = nine-hole peg-test; SDMT-O = oral symbol digit modalities test; T25FW = timed 25-foot walk; 6MWT = 6-min walk test.

At 24 weeks, 8.3% participants in the Swank group and 8.8% in the Wahls group had MSFC scores increases that exceeded the threshold of ≥0.5 points for clinical significance (p > 0.99). Furthermore, 11.1% participants in the Swank group and 8.8% in the Wahls group had improvements in the SDMT-O that exceeded the threshold of ≥8.0 points for clinical significance (p > 0.99). In addition, no participants in either group had clinically meaningful improvements in T25FW or NHPT values. Clinically significant thresholds corresponded to baseline-referenced z-scores of 0.82 for SDMT-O, 1.02 for T25FW, and 1.04 for NHPT.

Discussion

In this secondary analysis of the WAVES trial, both the Swank and Wahls diets were shown to statistically reduce functional disability, as assessed by the MSFC, 17 after 24 weeks. In addition, both groups also had statistically significant improvements in NHPT and SDMT-O z-scores at 24 weeks; however, there was no change in T25FW for either group. The effect of the dietary interventions on MSFC, NHPT, and 6MWT values was significantly mediated by fatigue.

Five previous dietary intervention trials assessed functional disability using the MSFC. One reported only baseline values despite reporting that assessments occurred throughout follow-up. 21 Three reported each of the three assessments used for MSFC calculations but did not report MSFC scores.20,22,23 The fifth reported that significant within-group MSFC improvements occurred in the plant-based low-fat intervention group over 12 months, but no differences were observed compared to the control group. 24 Due to the potential effect of exercise on MSFC, the findings from the fifth trial are confounded due to the inclusion of an exercise intervention in both groups. 24 Therefore, the findings from the present study are the first known to report on dietary intervention-specific changes in MSFC scores.

In the WAVES trial, the Swank and Wahls diets were previously shown to reduce fatigue and increase quality of life after 12 weeks 14 ; whereas the present secondary analysis indicates that reductions in functional disability occur at 24 weeks. This discrepancy in time between improvement in patient-reported outcomes and functional disability suggests that potential diet-induced changes in MS-specific functional outcomes require a longer duration intervention than changes in patient-reported outcomes. This observation is supported by previous findings from the WAVES trial showing that both groups had statistically significant improvements in the 6MWT at 24 weeks, 14 which seemingly contradicts the lack of observed change in T25FW in the present study. Therefore, other factors are associated with improvements in the 6MWT. Indeed, the present analysis indicates that changes in the 6MWT are mediated by fatigue whereas the T25FW is not mediated by fatigue.

The observation in the present study, that functional disability was statistically reduced in both diet groups at 24 weeks, is encouraging as it suggests that the potential effects of diet on functional disability are modulated by similar diet components rather than the unique composition of each diet. Corroborating this suggestion are results of a recent network meta-analysis that found only diets recommending high intake of fruits and vegetables and avoidance of ultra-processed foods significantly reduced fatigue and improved quality of life. 10 These recommendations are consistent across both the Swank and Wahls diets investigated in the present study. 13 Furthermore, these recommendations are consistent with the Mediterranean diet, for which adherence is linked to less functional disability 19 and greater brain volume 35 among people with MS.

The strengths of this study include the use of an objective measure of functional disability, masked assessors, repeated measures, and robust analytical methods. Additionally, there was high-diet adherence (≥80%) among both groups as evidenced by analysis of weighed food records. 14 This secondary analysis is limited by lack of a usual diet control group, no a priori power calculation for the MSFC, lack of diversity among the study participants, short duration of intervention, significant pre-intervention improvements among the Swank diet group, the reintroduction of nightshade vegetables among the Wahls group, and the wide range of exclusion criteria which limit the generalizability of the findings. Furthermore, the use of a single version of the SDMT-O necessitates caution due to the potential for practice effects 34 ; accordingly, results for the MSFC2, which excludes the SDMT-O, were attenuated in the Swank group. The low proportion of participants with clinically significant improvements limits the utility of recommendations for either of these diets investigated for short-term disability management among individuals with MS. However, it is worth noting that the low proportion with clinically meaningful SDMT-O changes are partially explained by the use of the recently recommended SDMT-O threshold of clinical significance which is twice the previous threshold. 30

This study provides preliminary evidence for the effect of dietary interventions on functional disability, as assessed by the MSFC, in RRMS and shows that fatigue mediates this effect largely through the NHPT. The observation that functional disability was reduced in both diet groups suggests that the benefits of dietary intervention in MS are driven by similar diet components, allowing patients to choose to follow dietary patterns based on their individual preferences. 12 Due to the limitations of the present study, future well-designed randomized controlled trials with an a priori defined objective to explore the impact of diet on functional disability are needed to confirm these findings and better understand the clinical usefulness of dietary interventions for disability management among people with MS.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, sj-docx-1-mso-10.1177_20552173231209147 for Diet-induced changes in functional disability are mediated by fatigue in relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis: A secondary analysis of the WAVES randomized parallel-arm trial by Landon J Crippes, Solange M Saxby, Farnoosh Shemirani, Babita Bisht, Christine Gill, Linda M Rubenstein, Patrick Ten Eyck, Lucas J Carr, Warren G Darling, Karin F Hoth, John Kamholz, Linda G Snetselaar, Tyler J Titcomb and Terry L Wahls in Multiple Sclerosis Journal – Experimental, Translational and Clinical

Supplemental material, sj-docx-2-mso-10.1177_20552173231209147 for Diet-induced changes in functional disability are mediated by fatigue in relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis: A secondary analysis of the WAVES randomized parallel-arm trial by Landon J Crippes, Solange M Saxby, Farnoosh Shemirani, Babita Bisht, Christine Gill, Linda M Rubenstein, Patrick Ten Eyck, Lucas J Carr, Warren G Darling, Karin F Hoth, John Kamholz, Linda G Snetselaar, Tyler J Titcomb and Terry L Wahls in Multiple Sclerosis Journal – Experimental, Translational and Clinical

Supplemental material, sj-doc-3-mso-10.1177_20552173231209147 for Diet-induced changes in functional disability are mediated by fatigue in relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis: A secondary analysis of the WAVES randomized parallel-arm trial by Landon J Crippes, Solange M Saxby, Farnoosh Shemirani, Babita Bisht, Christine Gill, Linda M Rubenstein, Patrick Ten Eyck, Lucas J Carr, Warren G Darling, Karin F Hoth, John Kamholz, Linda G Snetselaar, Tyler J Titcomb and Terry L Wahls in Multiple Sclerosis Journal – Experimental, Translational and Clinical

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge the following contributors: Mary Ehlinger for her role in study recruitment and as the primary study coordinator; Karen Smith for her role in nutrition data acquisition and as an intervention dietitian; Lisa Brooks for her role as an intervention dietitian; Michaella Edwards for her role in study coordination and data acquisition; Zaidoon Al-Share for his role in data acquisition; and the students who supported recruitment and data acquisition. The authors also thank Kristina Greiner for her editing assistance.

Footnotes

Data availability: The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to the privacy of the study participants.

Conflict of interests: TLW personally follows and promotes the Wahls™ diet. She has equity interest in the following companies: Terry Wahls LLC; TZ Press LLC; The Wahls Institute, PLC; FBB Biomed Inc; and the website: http://www.terrywahls.com. She also owns the copyright to the books Minding My Mitochondria (2nd Edition) and The Wahls Protocol, The Wahls Protocol Cooking for Life, and the trademarks The Wahls Protocol® and Wahls™, Wahls Paleo™, and Wahls Paleo Plus™ diets. She has completed grant funding from the National Multiple Sclerosis Society for the Dietary Approaches to Treating Multiple Sclerosis Related Fatigue Study. She has financial relationships with Vibrant America LLC, Standard Process Inc., MasterHealth Technologies Inc., Foogal Inc., Levels Health Inc., and the Institute for Functional Medicine. She receives royalty payments from Penguin Random House. TLW has conflict of interest management plans in place with the University of Iowa and the Iowa City Veteran's Affairs Medical Center.

Disclosures: Aspects of this work were presented at the 2020 ACTRIMS Forum and 2023 CMSC annual meetings.

Author contributions: LJ Crippes wrote the first draft of the manuscript with revisions from SMS, FS, and TJT. TJT cleaned and analyzed the data with supervision from LMR and PTE. LMR managed unblinded data. JK and CG were the study team neurologists. LJ Carr, WGD, KFH, BB, and JK trained study staff on assessment methods, assisted in data acquisition and interpretation, and oversaw study procedures. TJT planned the present analysis. TLW and LGS designed the trial and oversaw all study procedures. All authors have read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: The parent trial was supported in part by the National Multiple Sclerosis Society grant RG-1506- 04312 (TLW), the Institute for Clinical and Translational Science (ICTS) at the University of Iowa, and University of Iowa institutional funds. The ICTS is supported by the National Institutes of Health Clinical and Translational Science Award program (grant UL1TR002537). SMS is a research trainee of the University of Iowa Fraternal Order of Eagles Diabetes Research Center (T32DK112751-06). TJT, SMS, and FS are supported by the Carter Chapman Shreve Family Foundation and the Carter Chapman Shreve Fellowship Fund for diet and lifestyle research conducted by the Wahls Research team at the University of Iowa. In-kind support was provided by the University of Iowa College of Public Health Preventive Intervention Center.

ORCID iD: Tyler J Titcomb https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8162-4768

Supplemental material: Supplemental material for this article is available online.

Contributor Information

Landon J Crippes, Carver College of Medicine, University of Iowa, Iowa City, IA, USA; Department of Internal Medicine, University of Iowa, Iowa City, IA, USA.

Christine Gill, Department of Neurology, University of Iowa, Iowa City, IA, USA.

Linda M Rubenstein, Department of Epidemiology, University of Iowa, Iowa City, IA, USA.

Patrick Ten Eyck, Institute for Clinical and Translational Science, University of Iowa, Iowa City, IA, USA.

Karin F Hoth, Department of Psychiatry, University of Iowa, Iowa City, IA, USA.

John Kamholz, Department of Neurology, University of Iowa, Iowa City, IA, USA.

Linda G Snetselaar, Department of Epidemiology, University of Iowa, Iowa City, IA, USA.

Tyler J Titcomb, Department of Internal Medicine, University of Iowa, Iowa City, IA, USA; Department of Epidemiology, University of Iowa, Iowa City, IA, USA.

Terry L Wahls, Department of Internal Medicine, University of Iowa, Iowa City, IA, USA; Department of Neurology, University of Iowa, Iowa City, IA, USA.

References

- 1.Dunn M, Bhargava P, Kalb R. Your patients with multiple sclerosis have set wellness as a high priority—and the national multiple sclerosis society is responding. US Neurol 2015; 11: 80–86. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fitzgerald KC, Tyry T, Salter A, et al. A survey of dietary characteristics in a large population of people with multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler Relat Disord 2018; 22: 12–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Russell RD, Black LJ, Begley A. The unresolved role of the neurologist in providing dietary advice to people with multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler Relat Disord 2020; 44: 102304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Evans E, Levasseur V, Cross AHet al. et al. An overview of the current state of evidence for the role of specific diets in multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler Relat Disord 2019; 36: 101393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Katz Sand I. The role of diet in multiple sclerosis: mechanistic connections and current evidence. Curr Nutr Rep 2018; 7: 150–160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Parks NE, Jackson-Tarlton CS, Vacchi L, et al. Dietary interventions for multiple sclerosis-related outcomes. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2020; 5: CD004192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Silveira SL, Richardson EV, Motl RW. Desired resources for changing diet among persons with multiple sclerosis: qualitative inquiry informing future dietary interventions. Int J MS Care 2022; 24: 175–183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Marrie RA, Salter AR, Tyry T, et al. Preferred sources of health information in persons with multiple sclerosis: degree of trust and information sought. J Med Internet Res 2013; 15: e67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Beckett JM, Bird ML, Pittaway JKet al. et al. Diet and multiple sclerosis: scoping review of web-based recommendations. Interact J Med Res 2019; 8: e10050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Snetselaar LG, Cheek JJ, Fox SS, et al. Efficacy of diet on fatigue and quality of life in multiple sclerosis: a systematic review and network meta-analysis of randomized trials. Neurology 2023; 100: e357–ee66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Guerrero Aznar MD, Villanueva Guerrero MD, Cordero Ramos J, et al. Efficacy of diet on fatigue, quality of life and disability status in multiple sclerosis patients: rapid review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. BMC Neurol 2022; 22: 388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Spain RI, Piccio L, Langer-Gould AM. The role of diet in multiple sclerosis: food for thought. Neurology 2023; 100: 167–168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wahls TL, Chenard CA, Snetselaar LG. Review of two popular eating plans within the multiple sclerosis community: low saturated fat and modified Paleolithic. Nutrients 2019; 11: 352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wahls TL, Titcomb TJ, Bisht B, et al. Impact of the Swank and Wahls elimination dietary interventions on fatigue and quality of life in relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis: the WAVES randomized parallel-arm clinical trial. Mult Scler J Exp Transl Clin 2021; 7: 20552173211035399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wahls T, Scott MO, Alshare Z, et al. Dietary approaches to treat MS-related fatigue: comparing the modified Paleolithic (Wahls Elimination) and low saturated fat (Swank) diets on perceived fatigue in persons with relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis: study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials 2018; 19: 309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Drake AS, Weinstock-Guttman B, Morrow SA, et al. Psychometrics and normative data for the Multiple Sclerosis Functional Composite: replacing the PASAT with the Symbol Digit Modalities Test. Mult Scler 2010; 16: 228–237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rudick RA, Cutter G, Baier M, et al. Use of the Multiple Sclerosis Functional Composite to predict disability in relapsing MS. Neurology 2001; 56: 1324–1330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Polman CH, Rudick RA. The multiple sclerosis functional composite: a clinically meaningful measure of disability. Neurology 2010; 74: S8–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Katz Sand I, Levy S, Fitzgerald K, et al. Mediterranean Diet is linked to less objective disability in multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler 2022; 29: 248–260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Irish AK, Erickson CM, Wahls TL, et al. Randomized control trial evaluation of a modified Paleolithic dietary intervention in the treatment of relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis: a pilot study. Degener Neurol Neuromuscul Dis 2017; 7: 1–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Choi IY, Piccio L, Childress P, et al. A diet mimicking fasting promotes regeneration and reduces autoimmunity and multiple sclerosis symptoms. Cell Rep 2016; 15: 2136–2146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lee JE, Titcomb TJ, Bisht B, et al. A modified MCT-based ketogenic diet increases plasma beta-hydroxybutyrate but has less effect on fatigue and quality of life in people with multiple sclerosis compared to a modified Paleolithic diet: a waitlist-controlled, randomized pilot study. J Am Coll Nutr 2021; 40: 13–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wingo BC, Rinker JR, Green Ket al. et al. Feasibility and acceptability of time-restricted eating in a group of adults with multiple sclerosis. Front Neurol 2022; 13: 1087126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yadav V, Marracci G, Kim E, et al. Low-fat, plant-based diet in multiple sclerosis: a randomized controlled trial. Mult Scler Relat Disord 2016; 9: 80–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Polman CH, Reingold SC, Banwell B, et al. Diagnostic criteria for multiple sclerosis: 2010 revisions to the McDonald criteria. Ann Neurol 2011; 69: 292–302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pfeiffer E. A short portable mental status questionnaire for the assessment of organic brain deficit in elderly patients. J Am Geriatr Soc 1975; 23: 433–441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Saxby SM, Hass C, Shemirani F, et al. Association between improved serum fatty acid profiles and cognitive function during a dietary intervention trial in relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis. Int J MS Care 2023; (in press). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fischer JS, Rudick RA, Cutter GRet al. et al. The Multiple Sclerosis Functional Composite Measure (MSFC): an integrated approach to MS clinical outcome assessment. National MS Society Clinical Outcomes Assessment Task Force. Mult Scler 1999; 5: 244–250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kragt JJ, van der Linden FA, Nielsen JM, et al. Clinical impact of 20% worsening on Timed 25-foot Walk and 9-hole Peg Test in multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler 2006; 12: 594–598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Strober LB, Bruce JM, Arnett PA, et al. A much needed metric: defining reliable and statistically meaningful change of the oral version Symbol Digit Modalities Test (SDMT). Mult Scler Relat Disord 2022; 57: 103405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hoogervorst EL, Kalkers NF, Cutter GR, et al. The patient's perception of a (reliable) change in the Multiple Sclerosis Functional Composite. Mult Scler 2004; 10: 55–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mcculloch CE, Neuhaus JM. Generalized linear mixed models. In: Balakrishnan N, Colton T, Everitt B, et al. (eds) Wiley StatsRef: Statistics Reference Online. Online: Wiley StatsRef, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Akaike H. A new look at the statistical model identification. IEEE Trans Autom Control 1974; 19: 716–723. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fuchs TA, Gillies J, Jaworski MG, et al. Repeated forms, testing intervals, and SDMT performance in a large multiple sclerosis dataset. Mult Scler Relat Disord 2022; 68: 104375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Katz Sand IB, Fitzgerald KC, Gu Y, et al. Dietary factors and MRI metrics in early Multiple Sclerosis. Mult Scler Relat Disord 2021; 53: 103031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental material, sj-docx-1-mso-10.1177_20552173231209147 for Diet-induced changes in functional disability are mediated by fatigue in relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis: A secondary analysis of the WAVES randomized parallel-arm trial by Landon J Crippes, Solange M Saxby, Farnoosh Shemirani, Babita Bisht, Christine Gill, Linda M Rubenstein, Patrick Ten Eyck, Lucas J Carr, Warren G Darling, Karin F Hoth, John Kamholz, Linda G Snetselaar, Tyler J Titcomb and Terry L Wahls in Multiple Sclerosis Journal – Experimental, Translational and Clinical

Supplemental material, sj-docx-2-mso-10.1177_20552173231209147 for Diet-induced changes in functional disability are mediated by fatigue in relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis: A secondary analysis of the WAVES randomized parallel-arm trial by Landon J Crippes, Solange M Saxby, Farnoosh Shemirani, Babita Bisht, Christine Gill, Linda M Rubenstein, Patrick Ten Eyck, Lucas J Carr, Warren G Darling, Karin F Hoth, John Kamholz, Linda G Snetselaar, Tyler J Titcomb and Terry L Wahls in Multiple Sclerosis Journal – Experimental, Translational and Clinical

Supplemental material, sj-doc-3-mso-10.1177_20552173231209147 for Diet-induced changes in functional disability are mediated by fatigue in relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis: A secondary analysis of the WAVES randomized parallel-arm trial by Landon J Crippes, Solange M Saxby, Farnoosh Shemirani, Babita Bisht, Christine Gill, Linda M Rubenstein, Patrick Ten Eyck, Lucas J Carr, Warren G Darling, Karin F Hoth, John Kamholz, Linda G Snetselaar, Tyler J Titcomb and Terry L Wahls in Multiple Sclerosis Journal – Experimental, Translational and Clinical