ABSTRACT

Alphaviruses are emerging and re-emerging viruses that cause severe disease and threaten public health worldwide. To advance the understanding of the underlying mechanisms of alphavirus replication and identify new host restriction factors, we performed RNA-seq and identified antiviral host factors on the Getah virus (GETV), a re-emerging alphavirus. We identified tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin-inducible poly(ADP ribose) polymerase (TIPARP) as a host antiviral factor. TIPARP is downregulated in GETV-infected Vero cells, and its overexpression significantly inhibits GETV replication, while TIPARP deficiency results in significantly increased viral titers. We demonstrated that TIPARP interacts with the viral E2 glycoprotein, inducing k48-linked ubiquitination and subsequent proteasomal degradation. Additionally, we found that TIPARP recruits the E3 ubiquitin ligase membrane-associated RING-CH 8 (MARCH8) to modify the ubiquitination, leading to the degradation of E2. Lys253 in E2 was identified as the TIPARP-facilitated ubiquitination site. A mutation in Lys253 resulted in the loss of TIPARP’s anti-GETV effect. Our study demonstrated for the first time that host TIPARP is a restricting factor against GETV replication. Investigating the underlying mechanisms and understanding TIPARP for GETV will be essential to fully understanding viral pathogenesis and developing novel broad-spectrum therapeutic strategies against alphavirus infection.

IMPORTANCE

Alphaviruses threaten public health continuously, and Getah virus (GETV) is a re-emerging alphavirus that can potentially infect humans. Approved antiviral drugs and vaccines against alphaviruses are few available, but several host antiviral factors have been reported. Here, we used GETV as a model of alphaviruses to screen for additional host factors. Tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin-inducible poly(ADP ribose) polymerase was identified to inhibit GETV replication by inducing ubiquitination of the glycoprotein E2, causing its degradation by recruiting the E3 ubiquitin ligase membrane-associated RING-CH8 (MARCH8). Using GETV as a model virus, focusing on the relationship between viral structural proteins and host factors to screen antiviral host factors provides new insights for antiviral studies on alphaviruses.

KEYWORDS: alphavirus, antiviral factor, GETV, TIPARP

INTRODUCTION

Getah virus (GETV) is a member of the Semliki group of the Alphavirus genus in the family Togaviridae (1). The Semliki group viruses are spread primarily by mosquitoes; this group consists of Bebaru virus (BEBV), Chikungunya virus (CHIKV), Mayaro virus (MAYV), O'nyong-nyong virus (ONNV), Semliki Forest virus (SFV), and Una virus (UNAV). CHIKV, MAYV, and ONNV can infect humans and cause severe disease (2 – 4).

GETV was first isolated from Culex mosquitoes in Malaysia in 1995 (5) and has since been found in Australia, China, and numerous other countries in Asia and Europe (6). GETV has a broad geographical distribution and host range; it infects monkeys, pigs, horses, and other mammals and birds (7 – 10). GETV-neutralizing antibodies have been detected in cattle and humans (11 – 13), suggesting a potential public health risk. In pigs, GETV causes fever, anorexia, depression, diarrhea, fetal death, and reproductive disorders (14, 15). Infected horses exhibit transient pyrexia, skin rashes, and leg edema (16). Pigs and horses are important hosts for the amplification and circulation of GETV (17). Alphaviruses threaten public health continuously, and as a re-emerging alphavirus, GETV can potentially infect humans (18). Antiviral treatments and vaccines against GETV are still few available due to a lack of knowledge about the mechanism of GETV replication.

Like typical alphaviruses, GETV is enveloped with a positive-strand RNA genome. The genome is linear, approximately 11.7 kb in length containing a 5′-untranslated region (UTR), two large open reading frames (ORFs), a 3′-UTR, and a poly-A tail (19). ORF1 is at the 5′-end of the genome and encodes non-structural polyproteins (nsP1-nsP4). ORF2 is at the 3′-end and encodes five structural polyproteins [C (capsid), E3, E2, 6K, and E1] (20, 21). The envelope proteins E1 and E2 form heterodimers, a triplet comprising a viral spike. The spike proteins are important for attachment to cell surfaces and viral entry (22). E1 is a type I transmembrane protein that plays a role in immunogenicity and host range (23), and E2 is also a type I transmembrane protein responsible for receptor binding (24). Additionally, the interaction of E1 and E2, C and E2 is important for virus budding, indicating that E2 is essential for GETV replication (25, 26).

Tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin-inducible poly(ADP ribose) polymerase (TIPARP) (also called PARP7 or ARTD14) is a mono-ADP-ribosyltransferase with CCCH-type zinc finger domain-containing protein belonging to the PARP family (27). TIPARP contains a single CCCH-type zinc finger domain, a centrally located WWE (tryptophan-tryptophan-glutamate) protein interaction domain, and a C-terminal PARP catalytic domain (28). Zinc finger antiviral protein (ZAP, also called ZC3HAV1 or PARP13) is a member of the CCCH-type zinc finger domain-containing protein family (29). ZAP is a broadly active antiviral protein that inhibits the replication of numerous RNA viruses, including alphaviruses (30 – 32). ZAP functions by inducing the degradation of targeted viral RNA through its N-terminal CCCH-type zinc finger domain (33). Kozaki et al. reported that TIPARP inhibits Sindbis virus (SINV) replication by binding and degradation of viral RNA but not vesicular stomatitis virus (VSV), Japanese encephalitis virus (JEV), and influenza A virus (IAV), suggesting that TIPARP reacts with specific viral RNAs (34).

In this study, using the whole transcriptome RNA-seq, we identified TIPARP as a host restriction factor against GETV. TIPARP interacts with E2 and subsequently induces its ubiquitination and proteasomal degradation via the E3 ubiquitin ligase membrane-associated RING-CH8 (MARCH8), suppressing GETV replication. Additionally, we found that Lys253 is the primary ubiquitination site on GETV E2. Mutation of Lys253 abrogated the antiviral activity of TIPARP against GETV. We reveal the mechanism of TIPARP against GETV and provide an increased understanding of host defense mechanisms against GETV.

RESULTS

RNA-seq analysis of GETV-infected Vero cells

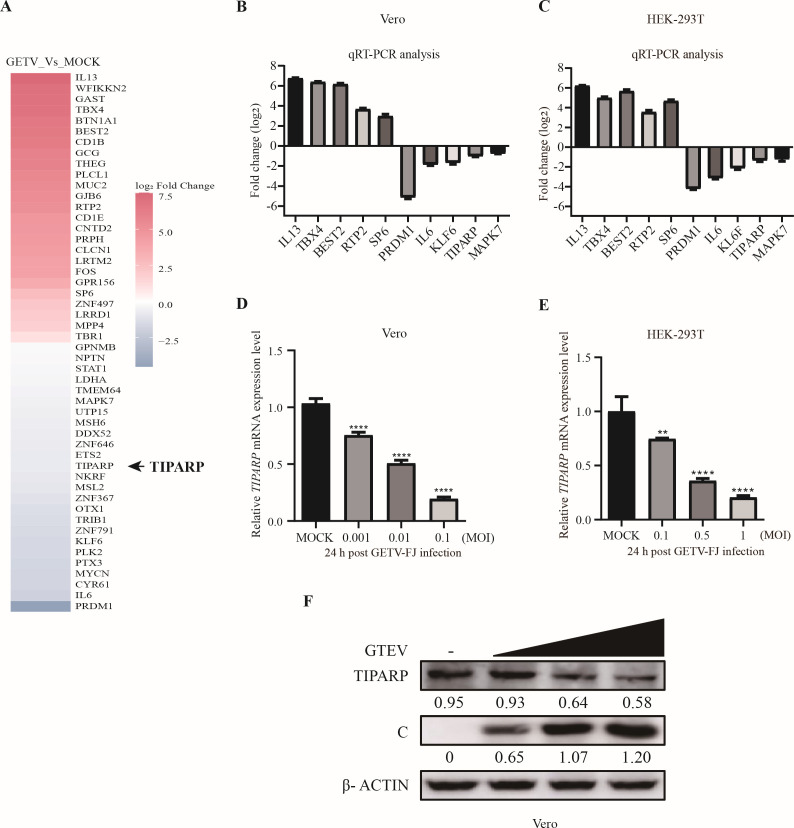

GETV could infect primates such as monkeys, and humans might be potential hosts. To reveal the connection of GETV infection mechanism in different species, we chose VERO cells for RNA-seq and carried out antiviral mechanism research in HEK-293T cells to explore the relationship between GETV infection in monkeys and humans. As can be seen from the heat map (Fig. 1A), 25 upregulated and 25 downregulated genes (including TIPARP) were randomly selected in the differentially expressed gene data. To validate the RNA-seq data, qRT-PCR was performed on five upregulated genes (IL13, TBX4, BEST2, RTP2, and SP6) and five downregulated genes (PRDM1, IL6, KLF6, TIPARP, and MAPK7). The results demonstrated that the data from RNA-seq were reliable and worthy of further study (Fig. 1B). Additionally, we detected those 10 genes in HEK-293T cells and found the same results (Fig. 1C). Those results indicated that the RNA-seq data were similar in Vero cells and HEK-293T cells and the HEK-293T cells could be used for subsequent research.

Fig 1.

TIPARP is downregulated by GETV infection. (A) Heat map of the mean log2FoldChange of differentially expressed host factors in GETV infected vs. uninfected Vero cells 24 hpi. Genes with an adjusted P-value <0.05 and |log2FoldChange|>0 analyzed by DESeq2 were assigned as differentially expressed. (B and C) Validation of RNA-seq data by qRT-PCR in Vero cells and HEK-293T cells. (D and F) qRT-PCR and western blotting analysis of TIPARP mRNA and protein level change in Vero cells infected with GETV-FJ. (E) qRT-PCR analysis of TIPARP mRNA level change in HEK-293T cells infected with GETV-FJ. The intensity of the bands of TIPARP and C was determined by ImageJ and normalized to those of β-actin. Data shown are the mean ± SD from three independent experiments. *, P < 0.05, **, P < 0.01, ***, P < 0.001, ****, P < 0.0001.

TIPARP is downregulated by GETV infection

We screened some genes involved in alphavirus replication in the differentially expressed genes of the transcriptome data (including TIPARP) and found that TIPARP has a significant antiviral function among these genes (data not shown). Previous studies have shown that TIPARP is a host immune-related factor that modulates viral infection. TIPARP inhibits SINV replication but promotes the infection of mouse hepatitis virus (MHV) (34 – 36). To identify the effect of GETV infection on TIPARP expression, we infected Vero cells with GETV-FJ at MOI of 0.001, 0.01, and 0.1 and infected HEK-293T cells with GETV-FJ at MOI of 0.1, 0.5, and 1 for 24 h. TIPARP expression, quantitated by qRT-PCR, decreased as a function of viral input (Fig. 1D and E). Accordingly, TIPARP protein levels, assessed by western blotting, also decreased as viral input increased in Vero cells (Fig. 1F). These results demonstrate that GETV infection results in depressed expression of TIPARP in vitro.

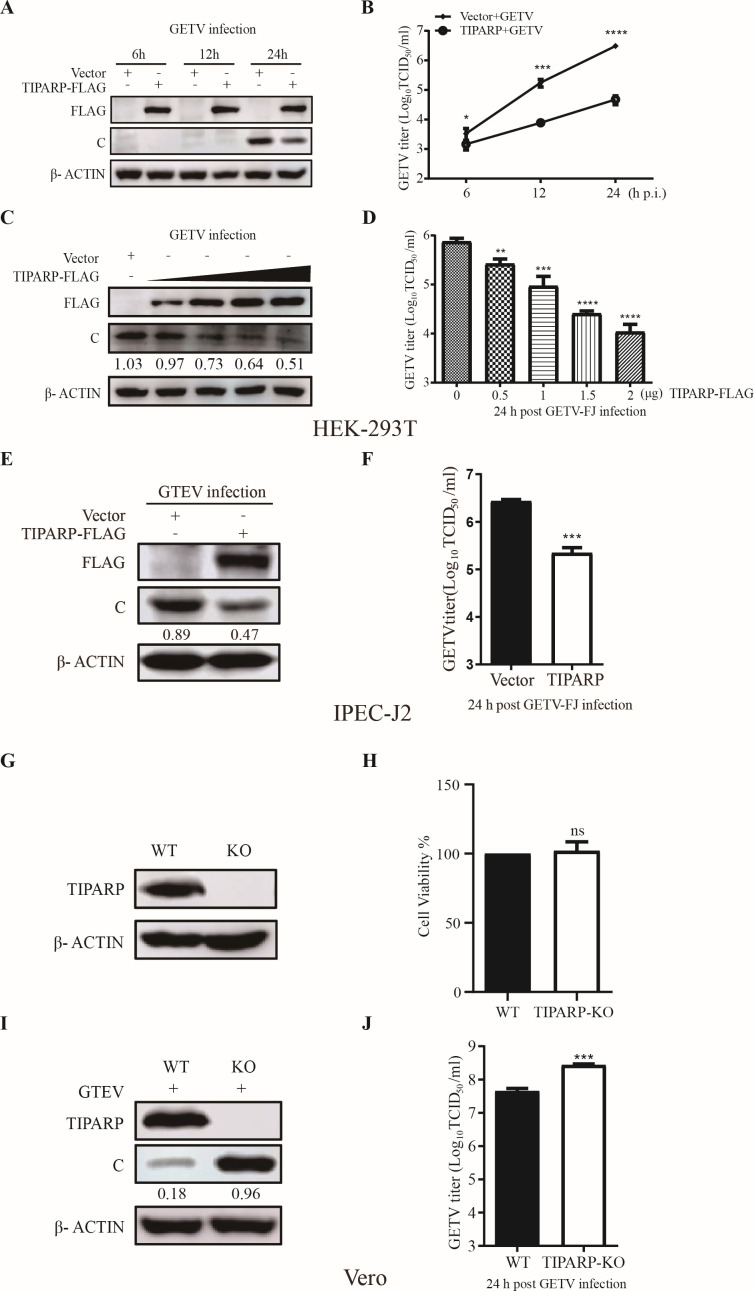

TIPARP overexpression inhibits GETV replication

To evaluate the role of TIPARP during GETV infection, HEK-293T cells were transfected with TIPARP-FLAG plasmids or empty vectors for 24 h and then infected with GETV-FJ at MOI of 0.1. Western blotting showed that overexpression of TIPARP resulted in decreased protein levels of the viral C protein throughout the infection time course (Fig. 2A). Accordingly, GETV titers were significantly lower by about 100-fold in TIPARP overexpressing cells at 24 h (Fig. 2B). We next investigated whether the suppression of GETV replication coincides with the amount of TIPARP expression. To this end, HEK-293T cells were transfected with TIPARP-FLAG at 0.5, 1, 1.5, and 2 μg for 24 h and then infected with GETV-FJ. Western blotting showed that C protein levels decreased with increasing TIPARP expression (Fig. 2C). Viral titers declined, TIPARP expression increased, and GETV titers were significantly lower by about 100-fold in cells with 2 μg TIPARP-FLAG plasmids (Fig. 2D). We further verified the antiviral function of TIPARP in IPEC-J2 cells. IPEC-J2 cells were transfected with TIPARP-FLAG or empty vectors for 24 h and then infected with GETV-FJ at MOI of 0.1. Western blotting showed that C protein levels decreased by about 2-fold (Fig. 2E), and GETV titers were significantly lower by about 10-fold in cells with TIPARP (Fig. 2F). These results demonstrated that TIPARP inhibits GETV infection.

Fig 2.

TIPARP inhibits GETV replication. (A and B) HEK-293T cells were transfected with TIPARP-FLAG or empty vectors for 24 h and then infected with GETV-FJ (MOI of 0.1). (A) Western blotting analysis of TIPARP and C protein level change. (B) Viruses released into the supernatant were titered by TCID50. (C and D) HEK-293T cells transfected with increasing amounts (from 0 to 2 µg) of TIPARP-FLAG or empty vectors for 24 h and then infected with GETV-FJ (MOI of 0.1). (C) Western blotting analysis of TIPARP and C protein level change. (D) Viruses released into the supernatant titered by TCID50. (E and F) IPEC-J2 cells were transfected with TIPARP-FLAG or empty vectors for 24 h and then infected with GETV-FJ (MOI of 0.1). (E) Western blotting analysis of TIPARP and C protein level change. (F) Viruses released into the supernatant were titered by TCID50. (G) Western blotting analysis of TIPARP protein level change in the Vero-WT and Vero-TIPARP-KO cells. (H) Cell viability of Vero-WT and Vero-TIPARP-KO cells. (I and J) Vero-WT and Vero-TIPARP-KO cells were infected with GETV-FJ (MOI of 0.001) for 24 h. (I) Western blotting analysis of TIPARP and C protein level change. (J) Titers of viruses released into the supernatant are determined by TCID50. The intensity of the bands of C was determined by ImageJ and normalized to those of β-actin. Data are shown as mean ± SD from three independent experiments. *, P < 0.05, **, P < 0.01, ***, P < 0.001.

TIPARP knockout (KO) promotes GETV replication

To further investigate the role of TIPARP in GETV replication, a TIPARP knockout Vero cell line (Vero-TIPARP-KO) was constructed using the CRISPR/CAS9. Western blotting showed that TIPARP could not be detected in the Vero-TIPARP-KO cells (Fig. 2G). MTT assay results showed that the viability of Vero-TIPARP-KO and Vero-WT cells was indistinguishable (Fig. 2H). Subsequently, the replication efficiency of GETV was assessed in Vero-TIPARP-KO and Vero-WT cells. Cells were infected with GETV-FJ at MOI of 0.001 for 24 h. In Vero-TIPARP-KO cells, C protein levels were about fivefold higher than in the WT cells (Fig. 2I). The titer of viruses released into the supernatant from the Vero-TIPARP-KO cells was about 10-fold higher than WT cells (Fig. 2J). In summary, TIPARP inhibits GETV replication.

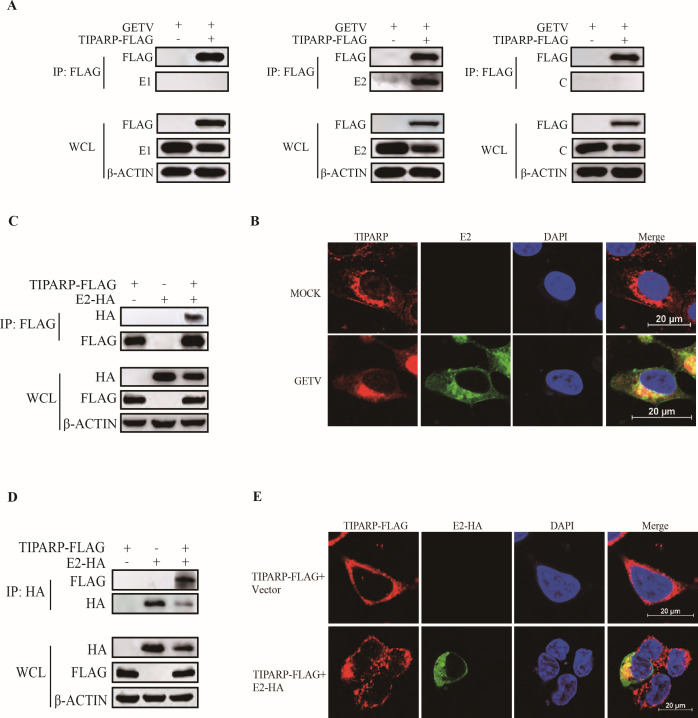

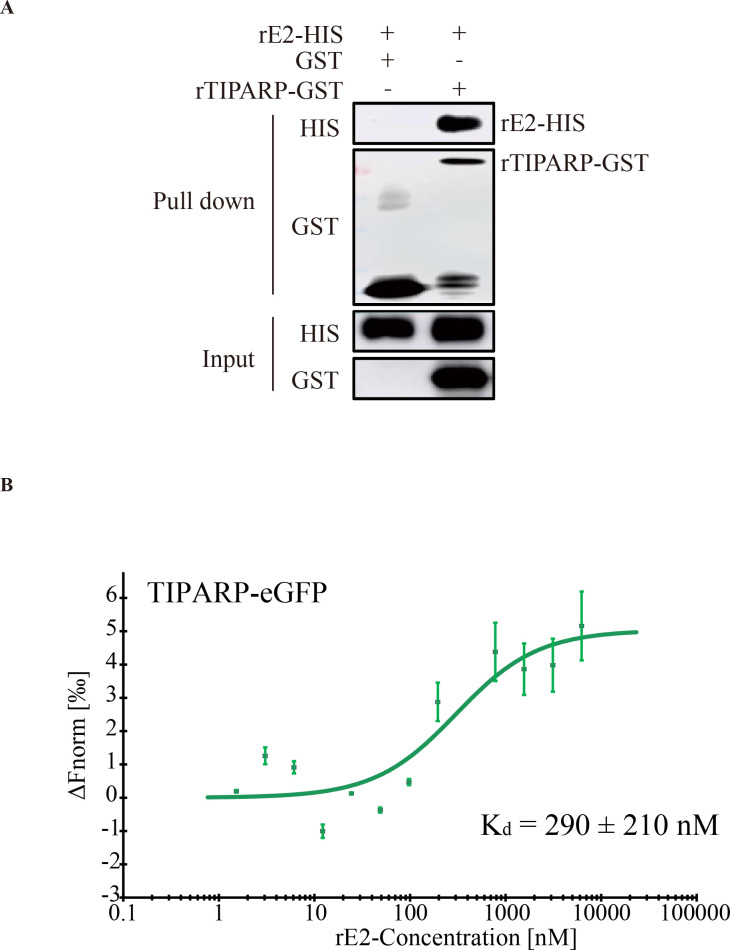

TIPARP interacts with GETV E2 glycoprotein

TIPARP inhibits alphavirus SINV replication by binding and degrading viral RNA (34). We wondered if TIPARP could also bind and degrade GETV RNA. HEK-293T cells were transfected with TIPARP-MYC plasmids for 24 h and then infected with GETV-FJ (MOI = 0.1) for 24 h. RNA immunoprecipitation showed that TIPARP could not bind and degrade GETV RNA (Fig. S1A). To explore the biological mechanism of TIPARP inhibiting GETV replication, we analyzed the interaction of TIPARP with GETV’s three main structural proteins (C, E1, E2). We transfected HEK-293T cells with TIPARP-FLAG plasmids for 24 h and then infected them with GETV-FJ at MOI 1 and performed coimmunoprecipitation assays (Co-IP). Western blotting of the Co-IPs indicated that TIPARP interacts with viral E2 only (Fig. 3A). Confocal microscopy revealed endogenous TIPARP localized in the cytoplasm (Fig. 3B, top). To determine the interaction of TIPARP and E2 under physiological conditions, we infected Vero cells with GETV-FJ at MOI of 0.001 for 24 h. Confocal microscopy again revealed that TIPARP colocalized with E2 in the cytoplasm of infected cells (Fig. 3B, bottom). To confirm the interaction between TIPARP and GETV-E2, we transfected HEK-293T cells with TIPARP-FLAG together with E2-HA plasmids or empty vectors for 24 h, western blotting highlights that TIPARP interacts with E2 (Fig. 3C and D), and confocal microscopy showed that TIPARP and E2 are colocalized in the cytoplasm (Fig. 3E). Meanwhile, GST pulldown and microscale thermophoresis (MST) confirmed the interaction between TIPARP and E2. TIPARP directly interacted with GETV-E2 with nanomolar affinity (K d , 290 ± 210 nM) (Fig. 4A and B). These results demonstrated that TIPARP interacted with GETV-E2 glycoprotein.

Fig 3.

TIPARP interacts with GETV E2 glycoprotein. (A) HEK-293T cells were transfected with TIPARP-FLAG or empty vectors for 24 h, then infected with GETV-FJ (MOI of 1) for 24 h. Cell lysates were subjected to anti-FLAG mAb coimmunoprecipitation and tested using the indicated antibodies by western blotting. (B) Confocal microscopy of GETV uninfected (top) and infected (bottom) Vero cells (MOI of 0.001, 24 h). (C, D, and E) HEK-293T cells were transfected with TIPARP-FLAG and E2-HA or empty vectors for 24 h. Cell lysates were subjected to coimmunoprecipitation using anti-FLAG (C) or anti-HA (D) mAb and tested with the indicated antibodies by western blotting. (E) Confocal microscopy HEK-293T cells transfected with TIPARP-FLAG and empty vectors (top) or TIPARP-FLAG and E2-HA (bottom). The data are representative of three independent experiments. Confocal images were recorded from three triplicate experiments and three separate experiments.

Fig 4.

TIPARP directly interacts with GETV-E2. (A) 1 µg GST or rTIPARP-GST was co-incubated with 1 µg recombinant E2. Then protein A/G agarose beads with rabbit polyclonal antibody against GST were used to pull down the GST complex. Components pulled down by the beads were detected by western blotting. (B) Microscale thermophoresis (MST). Dose-response curve for the binding interaction between rE2 and TIPARP-eGFP protein. The data are representative of three independent experiments.

All three domains of TIPARP have antiviral activity

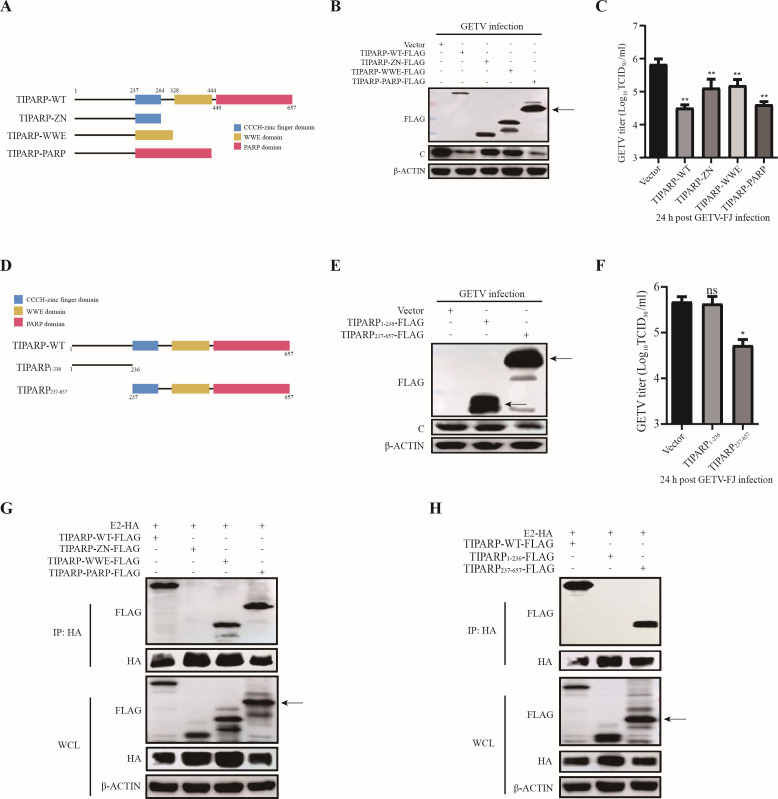

To investigate the mechanism underlying TIPARP anti-GETV activity, we sought to identify the essential antiviral domain of TIPARP. Three TIPARP truncations were constructed: TIPARP-ZN, TIPARP-WWE, and TIPARP-PARP (Fig. 5A). HEK-293T cells were transfected with TIPARP-WT or one of the truncations for 24 h and then infected with GETV-FJ at MOI of 0.1 for 24 h. Western blotting showed that all transfected cells had decreased C levels over empty vectors-transfected cells, but only in TIPARP-PARP transfected cells were C levels decreased to the same extent as in TIPARP-WT transfected cells (Fig. 5B). TCID50 assays showed that the viral titers were reduced accordingly (Fig. 5C).

Fig 5.

All three domains of TIPARP have antiviral activity. (A) Schematic of TIPARP-WT and TIPARP truncations: TIPARP-ZN, TIPARP-WWE, and TIPARP-PARP. (B and C) HEK-293T cells were transfected with TIPARP-WT, TIPARP truncations, or empty vectors for 24 h and then infected with GETV-FJ (MOI of 0.1) for 24 h. (B) Western blotting analysis of TIPARP truncations and C protein level change. (C) The titer of viruses released into the supernatant was determined by TCID50. (D) Schematic of TIPARP truncations: TIPARP1-236 and TIPARP237-657. (E and F) HEK-293T cells were transfected with TIPARP truncations or empty vectors for 24 h and then infected with GETV-FJ (MOI of 0.1) for 24 h. (E) Western blotting analysis of TIPARP truncations and C protein level change. (F) The titer of viruses released into the supernatant was determined by TCID50. (G and H) HEK-293T cells were transfected with E2-HA, TIPARP-WT, or TIPARP truncations for 24 h. Cell lysates were subjected to coimmunoprecipitation using anti-HA mAb and tested with the indicated antibodies by western blotting. The arrow denotes the target band. Data are shown as mean ± SD from three independent experiments. *, P < 0.05, **, P < 0.01, ***, P < 0.001, ****, P < 0.0001.

All the truncations had antiviral activity and contained the N-terminal amino acids (aa) 1–236. To exclude any effect of aa1–236, we constructed the deletion mutants TIPARP1–236 and TIPARP237–657 (Fig. 5D). HEK-293T cells were transfected with TIPARP-WT, TIPARP1–236, or TIPARP237–657 for 24 h and then infected with GETV-FJ at MOI of 0.1 for 24 h. Western blotting and TCID50 assay showed that TIPARP-WT and TIPARP237–657 inhibited GETV replication while TIPARP1–236 did not (Fig. 5E and F).

TIPARP is a mono-ADP-ribosyltransferase of the PARP family, and the typical H-Y-E triad motif is highly conserved. Even though glutamate is not present in the mono-ADP-ribosyltransferase, H-Y residues are still important (37 – 39). We found H-Y residues through a structure-based alignment of PARP1, PARP3, PARP12, and TIPARP (Fig. S2A) and constructed three TIPARP-PARP mutants: TIPARP-PARP (H320A), TIPARP-PARP (Y352A), and TIPARP-PARP (H320A/Y352A) (Fig. S2B). HEK-293T cells were transfected with TIPARP-PARP(WT) or one of the mutants for 24 h and then infected with GETV-FJ at MOI of 0.1 for 24 h. Western blotting and TCID50 assay showed that all the mutants could inhibit GETV replication (Fig. S2C and S2D), indicating that H-Y residues are unnecessary for the antiviral function. Those results showed that all the domains of TIPARP have antiviral activity, and the antiviral function of TIPARP is not dependent on its mono-ADP ribosyltransferase activity.

To determine which domain interacts with E2, HEK-293T cells were co-transfected with E2-HA and TIPARP-WT or one of the truncations for 24 h and then subjected to coimmunoprecipitation. Western blotting showed that only the WWE and PARP domains interact with E2 (Fig. 5G). The experiment was repeated using cells co-transfected with E2-HA and TIPARP-WT, TIPARP1–236, or TIPARP237–657 for 24 h and then subjected to coimmunoprecipitation. Western blotting showed that TIPARP237–657 interacts with E2 (Fig. 5H). These data indicate that all three domains of TIPARP have antiviral activity.

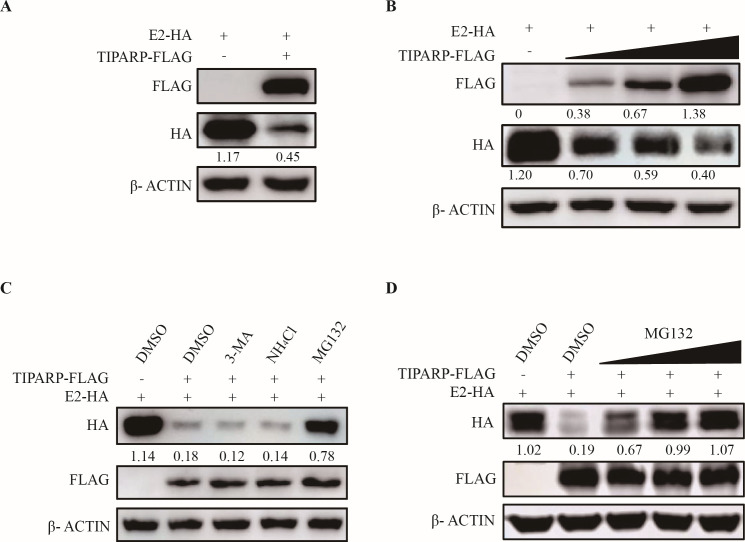

TIPARP induces degradation of E2 via the proteasomal way

From the Co-IP results, we found that the expression of E2 appeared attenuated by TIPARP (Fig. 3C and D). TIPARP-FLAG and E2-HA were co-transfected into HEK-293T cells to confirm this observation. Western blotting showed that the protein level of E2 was reduced by about 2.5-fold in TIPARP-FLAG transfected cells (Fig. 6A). HEK-293T cells were then co-transfected with E2-HA and increasing amounts (from 0 to 2 µg) of TIPARP-FLAG. Western blotting showed that the protein level of E2 declined with increasing TIPARP (Fig. 6B). Though TIPARP could not bind and degrade GETV RNA as was described for SINV (Fig. S1A), we hypothesized whether TIPARP would degrade the E2 glycoprotein of the other alphaviruses as well as GETV and examined the effect of TIPARP on the E2 glycoprotein of SINV, Ross River virus (RRV) and SFV. Western blotting showed that TIPARP-FLAG significantly decreased the expression level of SINV-E2 (9.4-fold), RRV-E2 (8.1-fold), and SFV-E2 (6.9-fold) (Fig. S1B). Additionally, Co-IP showed that TIPARP interacts with all the E2 glycoproteins (Fig. S1C). Those results indicated that TIPARP may be a broad-spectrum anti-alphavirus factor, specifically targeting alphavirus E2 glycoprotein degradation to exert antiviral function.

Fig 6.

TIPARP degrades E2 via the proteasomal pathway. (A) HEK-293T cells were transfected with E2-HA and TIPARP-FLAG or empty vectors for 24 h. Western blotting analysis of E2 protein level change. (B) HEK-293T cells were transfected with E2-HA and increasing amounts (from 0 to 2 µg) of TIPARP-FLAG or empty vectors for 24 h. Western blotting analysis of E2 protein level change. (C) HEK-293T cells were transfected with E2-HA and TIPARP-FLAG or empty vectors for 16 h, then treated with DMSO (5 µM), 3-MA (0.5 mM), NH4Cl (20 mM), or MG132 (5 µM) for 8 h. Western blotting analysis of E2 protein level change. (D) HEK-293T cells were transfected with E2-HA and TIPARP-FLAG or empty vectors for 16 h, then treated with increasing concentrations of MG132 (1, 5, and 10 µM) for 8 h. Western blotting analysis of E2 protein level change. The intensity of the bands of E2 and TIPARP was determined by ImageJ and normalized to those of β-actin. The data are representative of three independent experiments.

Eukaryotic cells’ major intracellular protein degradation pathways are autophagy, lysosomal, and proteasomal. To determine which pathway is induced by TIPARP, HEK-293T cells were co-transfected with TIPARP-FLAG and E2-HA and treated with 0.5 mM autophagy inhibitor 3MA (3-methyl adenine), 20 mM lysosome inhibitor NH4Cl, or 5 μM proteasome inhibitor MG132, 24 h post-transfection. Western blotting results showed that in cells treated with proteasome inhibitor MG132, E2 levels were higher than in the solvent controls or the 3MA (6.5-fold) or NH4Cl (5.5-fold)-treated cells (Fig. 6C). E2 levels increased as the dose of MG132 increased (Fig. 6D). These data demonstrate that TIPARP induces degradation of E2 via the proteasome pathway in a dose-dependent manner.

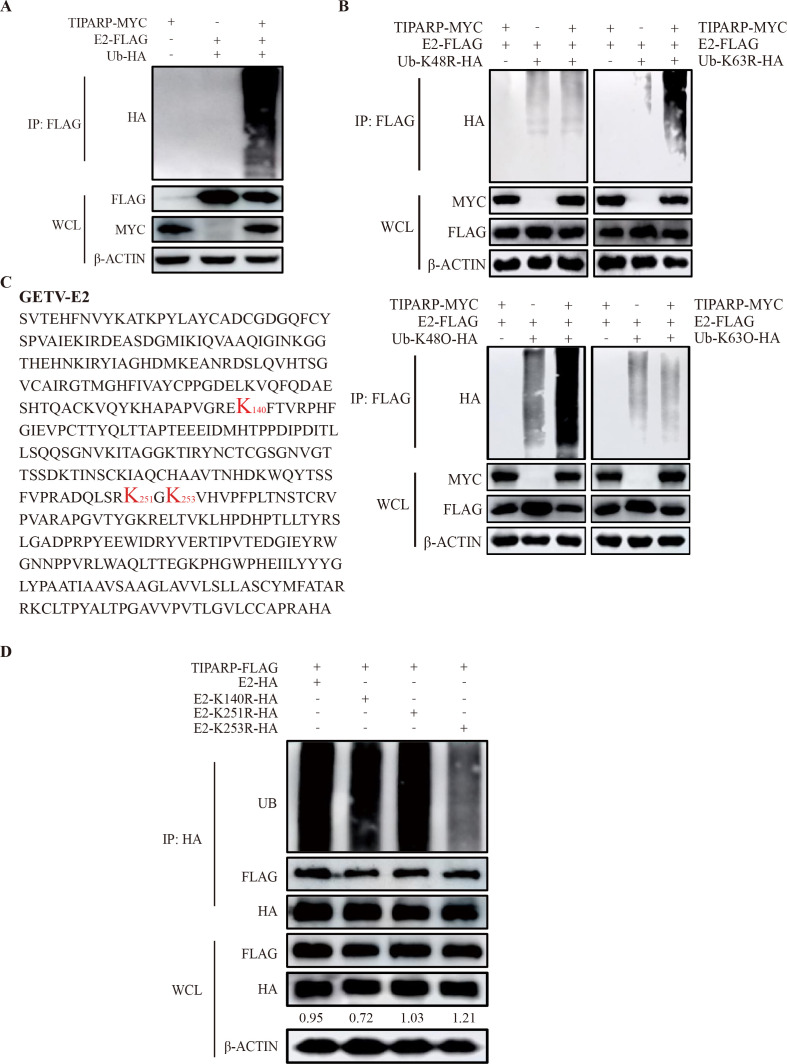

TIPARP catalyzed K48-linked ubiquitination of E2

Previous studies have shown that post-translational modifications (PTMs) and the degradation of proteins by ubiquitin via the Ub proteasome system are the main processes that medicate cellular proteins’ activity and function in cells (40, 41). Because TIPARP promotes the degradation of E2 via the proteasomal pathway (Fig. 6C), we sought to determine the ubiquitination level of E2. HEK-293T cells were transfected with TIPARP-MYC only as a negative control or E2-FLAG and Ub-HA, Ub-K48R-HA, and Ub-K63R-HA along with TIPARP-MYC or empty vectors for 24 h. Western blotting showed that TIPARP overexpression resulted in markedly increased ubiquitination of E2 (Fig. 7A). Additionally, with Ub-K63R-HA but not Ub-K48R-HA, E2 pulled down more ubiquitin in the presence of TIPARP (Fig. 7B, top panel), and E2 also pulled down more ubiquitin with Ub-K48O-HA (Fig. 7B, bottom panel). These results indicate that TIPARP modifies E2 protein by K48-linked ubiquitination.

Fig 7.

TIPARP catalyzed K48-linked ubiquitination of E2 at Lys253. (A) HEK-293T cells were transfected with E2-FLAG and Ub-HA with or without TIPARP-MYC for 24 h. Cells transfected with TIPARP-MYC served as the negative control. Cell lysates were subjected to coimmunoprecipitation using anti-FLAG mAb and tested with the indicated antibodies by western blotting. (B) HEK-293T cells were co-transfected with E2-FLAG and TIPARP-MYC or Ub-K48R/K63R-HA or TIPARP-MYC and Ub-K48R/K63R-HA for 24 h (top panel), HEK-293T cells were co-transfected with E2-FLAG and TIPARP-MYC or Ub-K48O/K63O-HA or TIPARP-MYC and Ub-K48O/K63O-HA for 24 h (bottom panel). Cell lysates were subjected to coimmunoprecipitation using anti-FLAG mAb and tested with the indicated antibodies by western blotting. (C) The amino acid sequence of GETV-E2. (D) HEK-293T cells were transfected with TIPARP-FLAG and E2-HA, E2-K140R-HA, E2-K251R-HA, or E2-K253R-HA for 24 h. Cell lysates were subjected to coimmunoprecipitation using anti-HA mAb and tested with the indicated antibodies by western blotting. The intensity of the bands of E2 was determined by ImageJ and normalized to those of β-actin. The data are representative of three independent experiments.

Lys 253 of E2 is a ubiquitination site in TIPARP

Ubiquitination is the addition of a ubiquitin molecule to a lysine residue of the target protein. We sought to identify the essential lysine residues of ubiquitin modification in E2. Three potential ubiquitination sites (Lys140), (Lys251), and (Lys253) in E2 were predicted (https://nctuiclab.github.io/ESA-UbiSite/) (Fig. 7C) (42). Accordingly, three E2 mutants were constructed, each with a single lysine residue replaced with arginine (E2-K140R-HA, E2-K251R-HA, and E2-K253R-HA). HEK-293T cells were transfected with TIPARP-FLAG and E2-HA, E2-K140R-HA, E2-K251R-HA, or E2-K253R-HA for 24 h. Coimmunoprecipitation and western blotting revealed that residue K253 is the predominant site of E2 ubiquitination by TIPARP (Fig. 7D). Meanwhile, the alignment of E2 protein sequences of GETV, SINV, RRV, and SFV showed that the K253 site is conserved among these viruses (Fig. S1D), indicating that K253 plays an important role in the degradation of E2 by TIPARP.

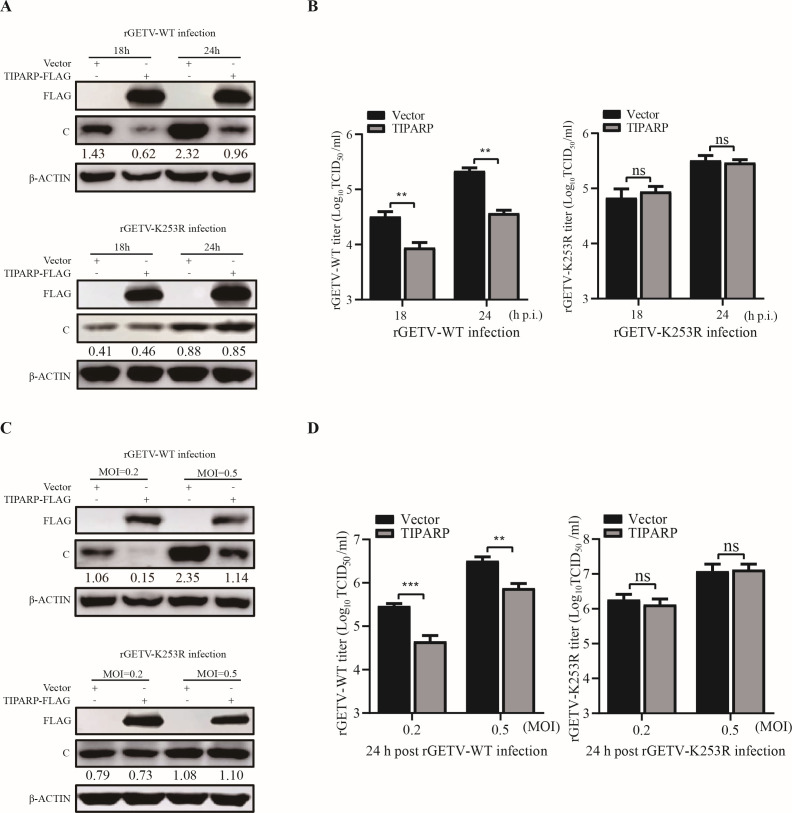

Mutation of the Lys253 abolishes the inhibition of GETV by TIPARP

E2 residue 253 plays a major role in determining the virulence of GETV (18). To determine the effect of TIPARP on rGETV-K253R, HEK-293T cells were transfected with TIPARP-FLAG or empty vectors for 24 h, then infected with rGETV-WT or rGETV-K253R at MOI of 0.1 for 18 h and 24 h. Western blotting showed that protein levels of rGETV-WT-C were significantly reduced by about 2.5-fold in TIPARP overexpressing cells, while rGETV-K253R-C protein levels were not (Fig. 8A). Viral titers at both time points were reduced in rGETV-WT infected cells but not in rGETV-K253R infected cells (Fig. 8B). Additionally, we transfected HEK-293T cells with TIPARP-FLAG or empty vectors for 24 h and then infected them with rGETV-WT or rGETV-K253R at MOI of 0.2 and 0.5 for 24 h. Western blotting and TCID50 assay showed the same results described above (Fig. 8C and D). These results indicated that mutation in the ubiquitination site of E2 abrogates the antiviral function of TIPARP against GETV and that TIPARP targets E2 lys253 for ubiquitination, thereby exerting antiviral function.

Fig 8.

TIPARP could not inhibit rGETV-K253R replication. (A and B) HEK-293T cells were transfected with TIPARP-FLAG or empty vectors for 24 h and then infected with rGETV-WT or rGETV-K253R (MOI of 0.1). (A) Western blotting analysis of TIPARP and C protein level change. (B) The titer of viruses released into the supernatant was determined by TCID50. (C and D) HEK-293T cells were transfected with TIPARP-FLAG or empty vectors for 24 h and then infected with rGETV-WT or rGETV-K253R (MOI of 0.2 or 0.5). (C) Western blotting analysis of TIPARP and C protein level change. (D) The titer of viruses released into the supernatant was determined by TCID50. The intensity of the bands of C was determined by ImageJ and normalized to those of β-actin. Data are shown as mean ± SD from three independent experiments. *, P < 0.05, **, P < 0.01, ***, P <0.001, ****, P < 0.0001.

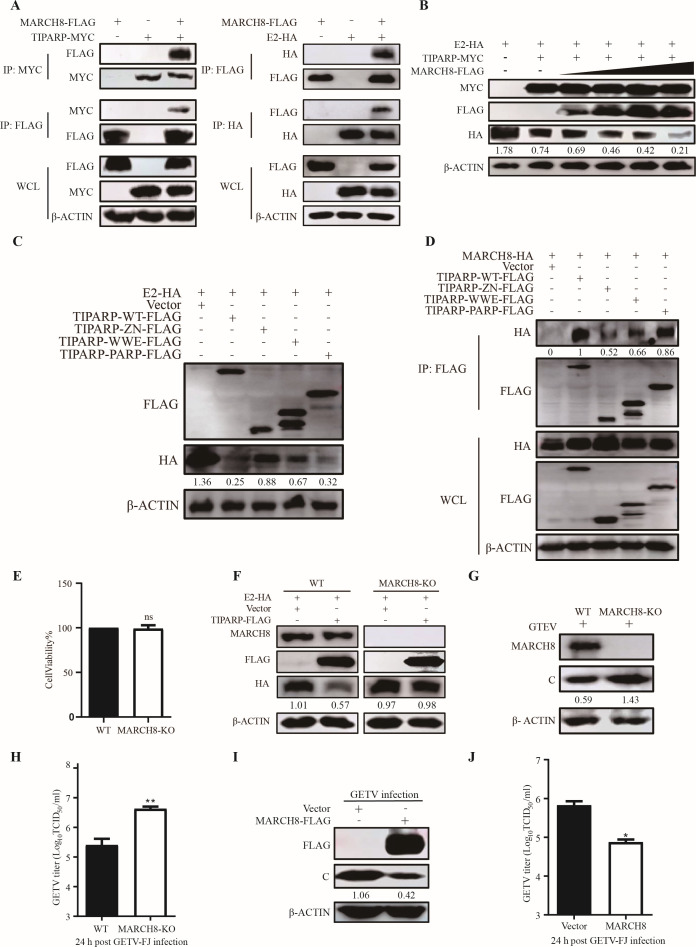

MARCH8 is an E3 ubiquitin ligase involved in the TIPARP-mediated degradation of E2

Since TIPARP is not an E3 ubiquitin ligase, we hypothesized it might recruit a potential E3 ubiquitin ligase that mediates E2 ubiquitination and degradation. There are many E3 ubiquitin ligases, such as the membrane-associated RING-CH (MARCH) family, Tripartite motif (TRIM) family, IPAH family, U Box proteins family, and E6-AP-related proteins family (43 – 47). The proteins in the MARCH family are mainly localized at plasma and/or organelle membranes and abundantly expressed in immune cells, which helps them regulate immune receptors and makes them unique (48, 49). MARCH8, as the first identified MARCH protein, shows wide-spectrum inhibition of enveloped viruses by inhibiting envelope glycoproteins, such as VSV, human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), and Ebola virus (EBOV) (50 – 52).

To determine whether MARCH8 is involved in TIPARP-induced ubiquitination and degradation of glycoprotein E2, we first examined the interaction of TIPARP and E2 with MARCH8. Co-IP showed that TIPARP and E2 interacted with MARCH8 (Fig. 9A). Furthermore, overexpression of MARCH8 significantly promoted the degradation (about 9-fold) of E2 by TIPARP in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 9B). We noticed that three domains of TIPARP degraded E2 to different degrees (Fig. 5G). We speculated that MARCH8 may cause the difference. We detected the degradation of E2 by three domains, TIPARP and TIPARP-PARP had the most significant effect on the E2 degradation (Fig. 9C). Then we detected the interaction of three domains with MARCH8, like TIPARP, TIPARP-PARP pulled down more MARCH8 compared with TIPARP-ZN and TIPARP-WWE (Fig. 9D), indicating that MARCH8 played an important role in the antiviral response of TIPARP by degrading E2. We next examined the function of endogenous MARCH8 in E2 degradation. We constructed MARCH8 knockout HEK-293T cell lines, and the MTT assay showed that the cell viability of 293T-MARCH8-KO cells was similar to that of WT cells (Fig. 9E). Western blotting indicated that in 293T-MARCH8-KO cells, TIPARP reduced the degradation of E2 compared to the WT cells (Fig. 9F). Additionally, western blotting and TCID50 showed that knockout of MARCH8 promotes GETV replication (Fig. 9G and H), while overexpression of MARCH8 inhibits viral replication (Fig. 9I and J). These results suggested that the E3 ubiquitin ligase MARCH8 is an antiviral factor involved in the degradation of E2.

Fig 9.

TIPARP-mediated degradation of GETV E2 was associated with MARCH8. (A) HEK-293T cells were transfected with MARCH8-FLAG and TIPARP-MYC (left) or E2-HA (right) for 24 h. Cell lysates were subjected to coimmunoprecipitation and western blotting using the indicated antibodies. (B) HEK-293T cells transfected with increasing amounts (from 0 to 2 µg) of MARCH8-FLAG, 2 µg E2-HA, and 2 µg TIPARP-MYC for 24 h. Western blotting analysis of E2 protein level change. (C) HEK-293T cells were transfected with E2-HA, TIPARP-WT, TIPARP truncations, or empty vectors for 24 h. Western blotting analysis of E2 protein level change. (D) HEK-293T cells were transfected with MARCH8-HA and TIPARP-WT, TIPARP truncations, or empty vectors for 24 h. Cell lysates were subjected to coimmunoprecipitation using anti-FLAG mAb and tested with the indicated antibodies by western blotting. (E) Cell viability of 293T-MARCH8-KO and 293 T-WT cell lines. (F) MARCH8-KO 293T cells and the WT cells were transfected with E2-HA and TIPARP-FLAG or empty vectors for 24 h. Western blotting analysis of MARCH8, TIPARP, and E2 protein level change. (G and H) 293T-MARCH8-KO and 293 T-WT cells were infected with GETV-FJ (MOI of 0.1) for 24 h. (I and J) HEK-293T cells were transfected with MARCH8-FLAG or empty vectors for 24 h and then infected with GETV-FJ (MOI of 0.1) for 24 h. (G and I) Western blotting analysis of MARCH8 and C protein level change. (H and J) The titer of viruses released into the supernatant was determined by TCID50. The intensity of the bands of E2 and viral C was determined by ImageJ and normalized to those of β-actin. The data are representative of three independent experiments. *, P < 0.05, **, P < 0.01, ***, P < 0.001, ****, P < 0.0001.

DISCUSSION

Alphaviruses are distributed worldwide, many causing severe diseases in humans and animals. The re-emerging alphavirus, GETV, has a wide host range and may infect humans, and it is an important and highly prevalent alphavirus. So far, there is no report on the antiviral mechanism and antiviral host factors. We tried to provide a strategy for alphavirus prevention from the perspective of GETV antiviral host factors screening for the first time. Research on the replication mechanisms of GETV is needed to develop effective anti-GETV therapies specifically and for developing antiviral therapies generally.

Previous studies on the antiviral factors of alphaviruses generally believed that the ZAP and PARP family proteins could inhibit the replication of multiple alphaviruses (30, 53). In addition, Viperin is a critical antiviral host protein that restricts CHIKV replication (54). However, there are no reports on antiviral factors active against GETV. For the first time, we identified TIPARP as a host factor restricting GETV replication by facilitating ubiquitinating viral E2 protein, targeting it for degradation. TIPARP is downregulated by GETV infection, and we found that GETV infection also downregulated AhR (Table S1). AhR is a positive regulator of TIPARP, and AhR activation directly induces TIPARP expression (36). GETV may reduce TIPARP expression by downregulating AhR. TIPARP is a PARP family member with a CCCH-type zinc finger domain, first reported as a component of the Aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AhR) pathway (28, 55). Recent studies demonstrate that TIPARP can inhibit or promote viral infection (34, 36). For example, TIPARP inhibits alphavirus SINV replication by binding and degradation of viral RNA through the CCCH-type zinc finger domain and has also been reported to negatively regulate type I interferon-mediated antiviral innate defense by interacting with the kinase TBK1 and suppressing its activity by ADP-ribosylation (35). TIPARP cannot bind and degrade GETV RNA to exert antiviral function, but TIPARP interacts with and degrades E2 of GETV and SINV, RRV, and SFV, revealing that TIPARP may specifically target the E2 glycoprotein of alphaviruses (Fig. S1).

TIPARP contains a CCCH-type zinc finger domain, a centrally located WWE protein interaction domain, and a C-terminal PARP catalytic domain (55). A CCCH-type zinc finger domain is found in many protein families, is conserved from yeast to mammals, and has been reported to inhibit various RNA viruses through interaction with the ZAP-responsive elements (ZRE) in viral RNA (56 – 58). ZAP, which contains a CCCH-type zinc finger domain, is reported to inhibit the replication of numerous alphaviruses, including SINV, SFV, RRV, and VEEV, although not VSV, YFV, HSV1, and poliovirus (30, 56). WWE domains occur in two classes of proteins, those associated with ubiquitination and those associated with poly-ADP ribosylation. WWE domains interact with E3 ubiquitin ligases, and when they bind a target protein, the modification results in altered functionality (59). The C-terminal PARP domain results from positive selection in primate ZAP protein and is reported to inhibit SFV.

Additionally, compared with the ZAP (S) isoform protein, the ZAP (L) isoform with the PARP domain exhibits stronger antiviral activity against alphaviruses (60, 61). Similarly, we found that the PARP domain in TIPARP could inhibit GETV replication, but the H-Y residues are not important for the PARP domain’s antiviral function, indicating that the mono-ADP ribosyltransferase function is not important for the antiviral activity. We found that all three domains interact with MARCH8, which may be why they can exert antiviral functions. TIPARP recruits MARCH8 to degrade the E2 of alphaviruses. Additionally, MARCH8 was reported to show broad-spectrum inhibition against viral envelope glycoproteins by recognizing their cytoplasmic lysine residues for degradation (62). So, there may be two potential antiviral mechanisms.

Like a typical alphavirus, GETV is covered by membrane-anchored spikes. The spikes are trimers of E2-E1 heterodimers (63). E1 is a type I fusion protein that, at the low pH of the endosome, drives the fusion of cellular and viral membranes (64). E2 is also a type I transmembrane glycoprotein responsible for receptor binding, host range, and tissue/cell tropism (25). E2 is synthesized as a precursor called P62, which dimerizes with E1 in the endoplasmic reticulum and aids in folding and transport (65). During the transport of the P62-E1 dimer, the P62 precursor is processed by furin to form E3 and produce mature E2 before reaching the plasma membrane. The cleavage of P62 is important for entry and fusion activation after entry into new cells (66). In addition, the juxtamembrane D-loop containing highly conserved H348 and Y352 of E2 interacts with E1 to promote virus budding, and the interaction between the nucleocapsid and the C-terminus of E2 is essential for viral budding (67, 68). TIPARP in the cytoplasm may specifically target E2 for degradation, thus blocking the dimerization of E2 and E1 and the interaction with the C protein, reducing viral budding and inhibiting GETV replication.

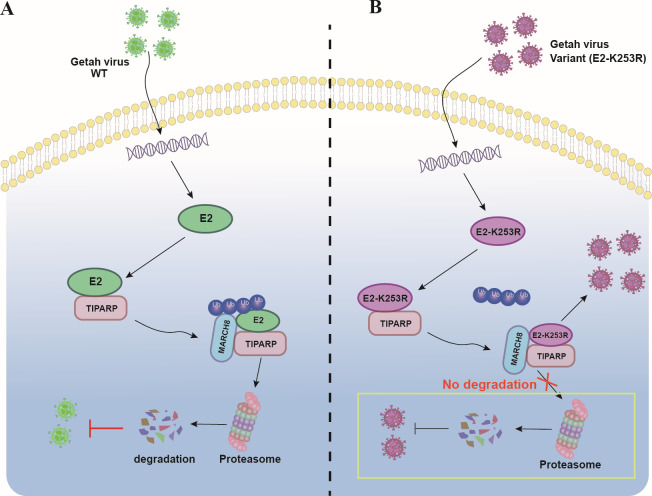

We used GETV as a model for alphaviruses to determine their relationship and host restriction factors. We identified TIPARP as a host factor that inhibits GETV replication by inducing ubiquitination of E2 and its proteasomal degradation via the E3 ubiquitin ligase MARCH8. Lys253 is the primary ubiquitination site in E2, and mutation of the Lys253 site abolished the inhibition of GETV by TIPARP (Fig. 10). Mutation of K253R enhances binding to heparan sulfate (HS), which improves virus attachment for better replication in vitro but accelerates virus clearance from the blood resulting in lower virulence in vivo (18). Mutation of K253R does not enhance the virulence of the virus and is not helpful for the spread of the virus, which is why K253 is conserved among alphaviruses. This study sheds light on the molecular mechanism of TIPARP’s anti-GETV activity and augments our understanding of the relationship between alphaviruses and host factors. TIPARP may specifically target and degrade the E2 glycoprotein of alphavirus and has the potential as a broad-spectrum anti-alphaviruses factor. These findings provide insight into developing antiviral drugs and attenuated vaccines against alphaviruses.

Fig 10.

The model of the antiviral mechanism of TIPARP. (A) Upon GETV-WT infection, TIPARP recruits the E3 ubiquitin ligase MARCH8 to modify the ubiquitination and degradation of E2, thereby inhibiting viral replication. (B) Upon infection with a GETV variant (E2-K253R), TIPARP can no longer modify the ubiquitination and degradation of E2 to inhibit viral replication.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cells and viruses

293T human embryonic kidney cells (HEK-293T), Porcine Small Intestinal Epithelial Cells (IPEC-J2) and African green monkey kidney cells (Vero) were maintained in DMEM (Gibco) supplemented with 10% (vol/vol) FBS (Biological Industries) at 37°C in a 5% CO2 humidified incubator.

GETV strains, GETV-FJ (MZ736799), were isolated from pigs and stored at −80°C in our laboratory. rGETV-WT and rGETV-K253R were previously established in our lab and stored at −80°C. Viruses were propagated and titrated using Vero cells.

Reagents and antibodies

DMSO, 3-methyl adenine (3-MA), NH4Cl, and MG132 were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. BALB/c mice were immunized with purified E1, E2, and C as an immunogen for four times to obtain monoclonal antibodies against GETV proteins E1, E2, and C. Mouse mAbs against FLAG and HA were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. Those mouse mAbs against β-actin were purchased from Proteintech, and those rabbit polyclonal antibodies against MYC were purchased from Sangon Biotech. Rabbit polyclonal antibodies against TIPARP and rabbit polyclonal antibodies against GST were purchased from Abclonal Technology, and Mouses IgG was purchased from Abmart. HRP anti-mouse IgG, HRP anti-rabbit IgG, FITC-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG, and FITC-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG were purchased from KPL, and A546-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG was purchased from Invitrogen. The SINV-E2-FLAG (GenBank accession number: MT121982) plasmid was purchased from GENEWIZ. The RRV-E (GenBank accession number: MN038231) and SFV-E (GenBank accession number: KP699763) plasmids were purchased from Sangon Biotech.

Plasmid construction

TIPARP (GenBank accession number: XM_008008616.2) was amplified from the cDNA of GETV-FJ infected Vero cells by RT-PCR and cloned into a pCAGGS vector. The expressed protein contained a FLAG or MYC tag at the C-terminus. The GETV E1, E2, and C proteins were amplified from the cDNA, reverse transcribed from GETV mRNA, and inserted into a pCAGGS vector. The expressed protein contained a FLAG or HA tag at the C-terminus. RRV-E2 and SFV-E2 were amplified from RRV-E and SFV-E plasmids and inserted into a pCAGGS vector. The expressed protein contained a FLAG tag at the C-terminus.

To identify the antiviral functional domain of TIPARP, TIPARP deletion mutants were cloned into pCAGGS. The expressed proteins contained a FLAG at the C-terminus. The schematic diagram of TIPARP and the truncated mutants is shown in Fig. 5A and D; Fig. S2B.

To determine the ubiquitination site in E2, three E2 point mutants (E2-K140R, E2-K251R, and E2-K253R) were constructed; the targeted lysines were replaced with arginine by site-directed mutagenesis (Fig. 7C). Primers are listed in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Primers in this study a

| Primer | Sequence (5′→3′) |

|---|---|

| TIPARP-F (EcoR I) | TTTGGCAAAGAATTCATGGAAATGGAAACCACCGA |

| TIPARP-Flag-R (Kpn I) | CTTGTAGTCGGTACCAATGGAAACAGTGTTACTGAC |

| TIPARP-ZN-F (EcoR I) | TTTGGCAAAGAATTCATGGAAATGGAAACCACCGA |

| TIPARP-ZN-Flag-R (Kpn I) | CTTGTAGTCGGTACCCAAGACGGTGTGGTGCTTC |

| TIPARP-WWE-F | CTACGAAGGCTGTCCACACCACCC |

| TIPARP-WWE-R | CAGCCTTCGTAGTTGGTGAGTGTGGTACTGCAATTG |

| TIPARP-PARP-F | TCAGCAAACTTTTACCCTGAAACT |

| TIPARP-PARP-R | AAAGTTTGCTGATTGGTGAGTGTGGTACTGCAATTG |

| TIPARP1-236-F (EcoR I) | TTTGGCAAAGAATTCATGGAAATGGAAACCACCGA |

| TIPARP1-236-Flag-R (Kpn I) | CTTGTAGTCGGTACCTTGGTGAGTGTGGTACTGCA |

| TIPARP237-657-F (EcoR I) | TTTGGCAAAGAATTCATGGAGAACGGAATTGAAATTTGC |

| TIPARP237-657-Flag-R (Kpn I) | CTTGTAGTCGGTACCCAAGACGGTGTGGTGCTTC |

| TIPARP-PARP (H320A)-F | CATTTATTTGCCGGAACATCCCAGGATGT |

| TIPARP-PARP (H320A)-R | AAATAAATGTCTCTCATTTAT |

| TIPARP-PARP (Y352A)-F | CAAGGCAGTGCCTTTGCAAAGAAGGCAAG |

| TIPARP-PARP (Y352A)-R | ACTGCCTTGTCCAAACATTG |

| rTIPARP-F (EcoR I) | GGATCCCCGGAATTCATGGAGAACGGAATTGAAATTTGC |

| rTIPARP-R (Xho I) | ATGCGGCCGCTCGAGTCAAATGGAAACAGTGTTACTGAC |

| TIPARP-sgRNA1-F | CACCGACGGTGGCAGATTCTACAGC |

| TIPARP-sgRNA1-R | AAACGCTGTAGAATCTGCCACCGTC |

| TIPARP-sgRNA2-F | CACCGTGTCTGTTCTGATACCTGAT |

| TIPARP-sgRNA2-R | AAACATCAGGTATCAGAACAGACAC |

| MARCH8-sgRNA1-F | CACCGTTCTATCACGCCATCCAGCC |

| MARCH8-sgRNA1-R | AAACGGCTGGATGGCGTGATAGAAC |

| MARCH8-sgRNA2-F | CACCGCAAGCAACATTTCTAAGGCT |

| MARCH8-sgRNA2-R | AAACAGCCTTAGAAATGTTGCTTGC |

| TIPARP-MYC-R1 | GAGTTTCTGCTCGCCGCCAATGGAAACAGTGTTACTGAC |

| TIPARP-MYC-R2 (Xho I) | AGATCTGCTAGCTCGAGTCACAGATCCTCTTCAGAGATGAGTTTCTGCTC |

| E2-F (EcoR I) | TTTGGCAAAGAATTCGCCACCATGAGTGTGACGGAACACTT |

| E2-HA-R (Kpn I) | GTAATCTGGAACATCGTATGGGTAGGTACCGGCATGCGCTCGTGGT |

| E2-FLAG-R (Kpn I) | CTTGTAGTCGGTACCGGCATGCGCTCGTGGT |

| RRV-E2-F (EcoR I) | TTTGGCAAAGAATTCGCCACCATGTCCGTGACAGAGCACTTT |

| RRV-E2-FLAG-R (Kpn I) | CTTGTAGTCGGTACCGGCGTTGGCGCGAGGA |

| SFV-E2-F (EcoR I) | TTTGGCAAAGAATTCGCCACCATGTCTGTGAGCCAGCACTTT |

| SFV-E2-FLAG-R (Kpn I) | CTTGTAGTCGGTACCAGCATGGGCGCGGGGG |

| E2-K140R-F | GGCAGAGAACGGTTCACCGTCAGGCCCCA |

| E2-K140R-R | TTCTCTGCCTACTGGGGCCG |

| E2-K251R-F | TTGTCTCGCCGGGGTAAAGTGCACGTACC |

| E2-K251R-R | GCGAGACAACTGGTCGGCTC |

| E2-K253R-F | CGCAAAGGTCGGGTGCACGTACCTTTCCC |

| E2-K253R-R | ACCTTTGCGAGACAACTGGT |

| qPCR-GETV-RNA-F | TCCACGCTGTCTAAGAGTTTG |

| qPCR-GETV-RNA-R | TCATGGTGTCTGTAATACGTGG |

| qPCR-GAPDH-F | GCACCGTCAAGGCTGAGAAC |

| qPCR-GAPDH-R | TGGTGAAGACGCCAGTGGA |

| qPCR-monkey-TIPARP-F | TCACTTGACCTCGTGTTTGAG |

| qPCR-monkey-TIPARP-R | TGATATGGCAAGACGGTGTG |

| qPCR-monkey-β-actin-F | TGAAGTGTGACGTGGACATC |

| qPCR-monkey-β-actin-R | CTTGATTTTCATCGTGCTGGG |

| qPCR-monkey-IL13-F | TGTGGAGCATCAACCTGAC |

| qPCR-monkey-IL13-R | AATCCGTTCAGCATCCTCTG |

| qPCR-monkey-TBX4-F | ATGAACCCCAAGACCAAGTAC |

| qPCR-monkey-TBX4-R | GGAGAATCTGGGTGGACATAC |

| qPCR-monkey-BEST2-F | ATGCTCTTTCACTACGACTGG |

| qPCR-monkey-BEST2-R | CAGGTCTAGGTCATGGTCTTTG |

| qPCR-monkey-RTP2-F | TGTACCAGCTTGACCACTTG |

| qPCR-monkey-RTP2-R | CTGCTCCACATACTGCTTCC |

| qPCR-monkey-SP6-F | TGGACTTCTCACAGGGCTAT |

| qPCR-monkey-SP6-R | GCCTGAACCACGATTCATAATG |

| qPCR-monkey-PRDM1-F | TGTGGTATTGTCGGGACTTTG |

| qPCR-monkey-PRDM1-R | CTTTGGGACATTCTTTGGGC |

| qPCR-monkey-IL6-F | AAAAGTCCTGATCCAGTTCCTG |

| qPCR-monkey-IL6-R | TTGCATCCCTGAGTTGTCC |

| qPCR-monkey-KLF6-F | ACAACTTAGAGACCAACAGCC |

| qPCR-monkey-KLF6-R | CTGACCAAAACTTCGCCAATG |

| qPCR-monkey-MAPK7-F | CGCTACTTCCTGTACCAACTG |

| qPCR-monkey-MAPK7-R | ACGAGCCATACCAAAGTCAC |

| qPCR-human-IL13-F | AACATCACCCAGAACCAGAAG |

| qPCR-human-IL13-R | ACACGTTGATCAGGGATTCC |

| qPCR-human-TBX4-F | ACCCTCGCCACATCTAAATG |

| qPCR-human-TBX4-R | GTTCTCCACAGTCCCCATTC |

| qPCR-human-BEST2-F | TGCTTCCTTGGGTTCTACATG |

| qPCR-human-BEST2-R | CATAAAAGCCAAGCACGAAGG |

| qPCR-human-RTP2-F | CATAGACCCCAACCTCAAGC |

| qPCR-human-RTP2-R | AGGAACATGTGGAAGAGGATG |

| qPCR-human-SP6-F | GACTTCTCGCAGGGCTATG |

| qPCR-human-SP6-R | GCCTGAACCACGATTCATAATG |

| qPCR-human-PRDM1-F | CTACACCATTAAGCCCATCCC |

| qPCR-human-PRDM1-R | TCGGTTGCTTTAGACTGCTC |

| qPCR-human-IL6-F | AAAAGTCCTGATCCAGTTCCTG |

| qPCR-human-IL6-R | TGAGTTGTCATGTCCTGCAG |

| qPCR-human-KLF6-F | ACAACTTAGAGACCAACAGCC |

| qPCR-human-KLF6-R | CTGACCAAAACTTCGCCAATG |

| qPCR-human-TIPARP-F | TTCCCTTGACCTCGTGTTTG |

| qPCR-human-TIPARP-R | GTGCTTCAAACAATCCCTGC |

| qPCR-human-MAPK7-F | CGCTACTTCCTGTACCAACTG |

| qPCR-human-MAPK7-R | ACGAGCCATACCAAAGTCAC |

The restriction enzyme sites used for cloning and the locations of mutations are indicated in italics.

RNA sequencing

RNA-seq transcriptome libraries were prepared following the NEBNext Ultra Directional RNA Library Prep Kit for Illumina (New England Biolabs, USA), using 1 µg of total RNA. Briefly, messenger RNA was isolated with polyA selection by oligo(dT) beads and fragmented using a fragmentation buffer. cDNA synthesis, end repair, A-base addition, and ligation of the Illumina-indexed adaptors were performed according to Illumina’s protocol. Libraries were then the size selected for cDNA target fragments of 250–300 bp on 2% Low Range Ultra Agarose followed by PCR amplified using Phusion DNA polymerase (NEB) for 15 PCR cycles. After quantified by Agilent 2100 bioanalyzer, RNA-Seq transcriptome libraries were sequenced by Illumina novo6000 on a 150-bp paired-end run by Novogene (Beijing, China). A total of 430,124,622 clean reads were obtained by removing the low-quality reads (reads with adapters, reads in which unknown bases are more than 10%, and low-quality reads indicating that the percentage of low-quality bases is over 50% in a read. Low-quality read bases were defined as a base whose sequencing is no more than 20). All clean reads were mapped to the reference genome using hierarchical indexing for spliced alignment of transcript 2 (HISAT 2). Differentially expressed genes were selected as those having |log2FoldChange|>0 difference between their geometrical mean expression in the compared groups and a statistically significant P-value (<0.05) by analysis of DEseq2 (Table S1). Each gene’s FPKM (expected number of Fragment Per Kilobase of transcript sequence per Million base pairs sequenced) was calculated and used to represent the gene expression value (Table S2). Three biological replicates were performed.

Generation of a TIPARP knockout and MARCH8 knockout cell line

KO cells were generated using CRISPR/CAS9. Two sgRNA sequences of TIPARP and MARCH8 (TIPARP-sgRNA1-F: CACCGACGGTGGCAGATTCTACAGC, TIPARP-sgRNA1-R: AAACGCTGTAGAATCTGCCACCGTC, TIPARP-sgRNA2-F: CACCGTGTCTGTTCTGATACCTGAT, TIPARP-sgRNA2-R: AAACATCAGGTATCAGAACAGACAC, MARCH8-sgRNA1-F: CACCGTTCTATCACGCCATCCAGCC, MARCH8-sgRNA1-R: AAACGGCTGGATGGCGTGATAGAAC, MARCH8-sgRNA2-F: CACCGCAAGCAACATTTCTAAGGCT, MARCH8-sgRNA2-R: AAACAGCCTTAGAAATGTTGCTTGC) were designed using the online CRISPR tool (https://www.benchling.com). Double-stranded nucleotide fragments were obtained by annealing the synthesized sgRNA oligonucleotides and cloning them into a lentiCRISPR v2 plasmid. The plasmid was extracted using an Endo-free Plasmid Mini Kit I (OMEGA), and its integrity was determined by sequencing.

Vero cells were co-transfected with 2 µg plasmids containing gRNA, 1.2 µg psPAX2, and 0.8 µg pMD2.G per well (6-well plate) using Lipofectamine 2000 according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Cell supernatants were collected at 60 h post-transfection to infect Vero cells at 30–40% confluence. To isolate a single-cell clone, 5 mg/mL of puromycin was aliquoted into wells when cells reached 90% confluence. The cells were diluted and seeded into the 96-well plates at 100 and 10 cells/mL. Western blotting and sequence analysis were used to identify the TIPARP-KO cells.

Cell viability assay

Vero-WT cells, TIPARP-KO or 293T-MARCH8-KO, and 293T-WT cells were seeded into 96-well plates and cultured until confluent. According to the manufacturer’s instructions, 10 µL of MTT (5 mg/mL, Beyotime) was aliquoted per well. The absorbance was measured at 490 nm using a microplate reader. Results are normalized to WT cells which are defined as 100% viable. Data were recorded from three triplicate experiments on the same plate and three separate experiments.

Coimmunoprecipitation assay

HEK-293T cells were seeded into 6-well plates and co-transfected with the indicated plasmids (2 µg per plasmid) for 24 h. Cells were washed three times with ice-cold PBS and then lysed in NP-40 buffer (Beyotime). The lysates were centrifuged at 12,000 rpm for 1 min, and supernatants were collected and incubated with 1 µg appropriate antibody and 20 µL protein A/G agarose beads (Beyotime) for 6–8 h at 4°C. The agarose beads were washed thrice with ice-cold PBS by centrifugation at 2,500 rpm for 5 min at 4°C. Bound proteins were analyzed by western blotting. Results were recorded from three separate experiments.

Confocal microscopy

HEK-293T cells and Vero cells were cultured with indicated conditions. Subsequently, cells were washed three times with ice-cold PBS and fixed in 4% (vol/vol) paraformaldehyde for 30 min and permeabilized with a solution of PBS containing 0.2% Triton X-100 for 10 min (Sigma) at room temperature. Cells were washed again, blocked with 5% (wt/vol) nonfat milk for 1 h, then incubated with rabbit mAb anti-FLAG (1:2,000), mouse mAb anti-E2 (1:1,000), mouse mAb anti-HA (1:2,000), and rabbit polyclonal antibody against GST (1:2,000) for 2 h at room temperature. Cells were washed thrice and then incubated with A546-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG (1:500) and FITC-conjugated goat anti-mouse or anti-rabbit IgG (1:500) for 1 h. Cells were washed and stained with DAPI for 10 min at room temperature. Cells were observed using confocal microscopy (Nikon, Japan) equipped with micro-objective (Plan Apo 60×/1.40, oil immersion, Nikon, Japan) and Microscope eyepiece (CFI, 10×/22, Nikon). Finally, images were processed by Nikon’s Confocal NIS-Elements Package software. Images were recorded from three triplicate experiments and three separate experiments.

GST pulldown assay

One microgram GST or rTIPARP-GST was co-incubated with 1 µg recombinant E2. Then the mixture was incubated with 1 µg rabbit polyclonal antibody against GST and 20 µL protein A/G agarose beads (Beyotime) for 6–8 h at 4°C. The agarose beads were washed thrice with ice-cold PBS by centrifugation at 2,500 rpm for 5 min at 4°C. Bound proteins were analyzed by western blotting. Results were recorded from three separate experiments.

Microscale thermophoresis (MST)

HEK-293T cells were transfected with TIPARP-eGFP plasmids for 48 h. Cells overexpressing TIPARP-eGFP were suspended in NP-40 buffer to obtain TIPARP-eGFP proteins. Twenty nanomolars of TIPARP-eGFP in PBS-T buffer (PBS 1×, 0.05% Tween 20) were mixed with recombinant E2 concentration varying from 6.25 µM to 1.53 nM at room temperature for 30 min to achieve binding equilibrium. Mixtures were absorbed into MST capillaries and measured using a Monolith NT.115 (NanoTemper Technologies). Data were fitted using the Hill equation, and K d values were determined using MO. Affinity analysis software (NanoTemper Technologies, Munich, Germany). Results were recorded from three independent experiments.

RNA immunoprecipitation assay

HEK-293T cells were transfected with TIPARP-MYC or empty vectors for 24 h and then infected with GETV-FJ (MOI = 0.1) or not infected with GETV for 24 h in a 75 cm2 cell culture dish. Cells were cross-linked with 1% formaldehyde for 15 min and washed twice with cold PBS. Cells were harvested by scraping and lysed in 1 mL RIP buffer (25 mM Tris-HCl, pH = 7.4, 150 mM NaCl, 1% NP-40, 1 mM EDTA, 5% Glycerol, PMSF, RNase inhibitor). The lysates were centrifuged at 12,000 rpm for 5 min at 4°C, and supernatants were quickly frozen at −80°C. Fifty microliters protein A/G beads were washed with RIP buffer and then incubated with 5 µg MYC antibodies or 5 µg IgG with gentle rotation for 2 h at 4°C. One percent (vol/vol) of cell lysates was used as input and added gently to the beads prepared above for 6 h at 4°C. The beads were washed three times with ice-cold RIP buffer by centrifugation at 2,500 rpm for 5 min at 4°C, followed by TRIzol extraction. The same volume of RNA was reverse-transcribed. The cDNA was subjected to qRT-PCR analysis. Results were recorded from three separate experiments.

Western blotting

Cells were lysed in NP-40 buffer, and 4× SDS loading buffer (Solarbio) was added to samples which were then incubated in a boiling water bath for 10 min. Proteins were separated on 10% SDS-PAGE gels and transferred onto nitrocellulose membranes (GE Amersham Bioscience). Membranes were blocked with 5% (wt/vol) nonfat milk for 1 h at room temperature, then incubated for 1 h with anti-FLAG, -HA, -GETV-E2, -TIPARP, -MYC, or -β-actin. Membranes were washed three times with PBST (10 min each) and then incubated for 1 h with HRP anti-rabbit IgG (1:2,000) or HRP anti-mouse IgG (1:2,000). Protein bands were detected by chemical luminescence substrate with Amersham Imager 600 (GE, USA). Results were recorded from three separate experiments.

Quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR)

Total RNA was extracted from cells using TRIzol (Vazyme) according to the manufacturer’s instructions and reverse transcribed into cDNA using a HiScript II 1st Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit (Vazyme). Fold-change in relative RNA quantities was assessed in triplicate by SYBR (Vazyme) using a Light Cycler 96 real-time PCR system (Roche). Primers are listed in Table 1. The data were analyzed using the 2−△△Ct method. Data were recorded from three triplicate experiments on the same plate and three separate experiments.

TCID50 titration

Vero cells were seeded in 96-well plates infected with a 10-fold serially diluted virus inoculum and incubated for 3 d at 37°C. Each sample was titrated in triplicate; at each dilution, there were six replicates. The titers of supernatants were determined using the Reed-Munch method. Data were recorded from three triplicate experiments on the same plate and three separate experiments.

Establishing a reverse genetic system for GETV

The information on rGETV-K253R and rGETV-WT was described in the previous study (18).

Recombinant expression and purification of rTIPARP and rE2

TIPARP237–657 was amplified from the cDNA of GETV-FJ infected Vero cells by RT-PCR and cloned into a pGEX-4T-1 vector. In LB media, recombinant pGEX-4T-1-TIPARP was expressed in BL21 (DE3) E. coli (Genesand). rTIPARP was induced by isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactoside (IPTG) to a final concentration of 1 mM at 16°C for 18 h. According to the manufacturer’s instructions, the recombinant protein was purified using a GST resin (Beyotime). pET-32a-E2 was purified using a His-tag resin (Beyotime) with the same method. The concentration of recombinant protein was detected by BCA Protein Assay Kit (Vazyme).

Statistical analysis

All experiments were repeated at least three times. Data are presented as the mean ± standard deviation (SD) from three independent experiments. Data were analyzed using GraphPad Prism 8. The significance of variability between groups was determined by Student’s t-test or one-way ANOVA. P-values <0.05 were considered significant.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We acknowledge the Confocal Laser Scanning Microscope Instrument Platform of Immunology, College of Veterinary Medicine, Nanjing Agricultural University and the Bioinformatics Center of Nanjing Agricultural University. We thank Michael Veit from the Institute for Virology, Center for Infection Medicine, Veterinary Faculty, Free University Berlin, for his guidance and help.

This work was supported by the National Nature Science Foundation of Outstanding Youth Fund in China (NSNF grant no. 31922081) and the Young Top-Notch Talents of National 10 Thousand Talent Program.

S.S. conceived and designed the experiments. H.J., Z.Y., X.Z., Y.Y., N.W., X.L., and Z.J. performed experiments and analyzed data. S.S., H.J., and Z.Y. wrote the manuscript. All authors reviewed and edited the paper.

The authors declare no competing interests.

Contributor Information

Shuo Su, Email: shuosu@njau.edu.cn.

Mark T. Heise, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, North Carolina, USA

DATA AVAILABILITY

The raw transcriptomic dataset presented in this research has been deposited in the National Center for Biotechnology Information under accession number PRJNA930320.

SUPPLEMENTAL MATERIAL

The following material is available online at https://doi.org/10.1128/jvi.00591-23.

Fig. S1. TIPARP interacts with SINV E2 glycoprotein. (A) HEK-293T cells were transfected with TIPARP-MYC for 24 h and then infected with GETV-FJ (MOI of 0.1) for 24 h. The levels of GETV RNA binding to the indicated MYC-tagged proteins were measured by RNA immunoprecipitation and qRT-PCR. (B) HEK-293T cells were transfected with TIPARP-MYC and SINV-E2-FLAG (left), RRV-E2-FLAG (mid), or SFV-E2-FLAG (right) for 24 h. Western blotting analysis of TIPARP and E2 protein level change. (C) HEK-293T cells were transfected with TIPARP-MYC and SINV-E2-FLAG (left), RRV-E2-FLAG (mid), or SFV-E2-FLAG (right) for 24 h. Cell lysates were subjected to coimmunoprecipitation using anti-FLAG mAb and anti-MYC pAb and tested using the indicated antibodies by western blotting. (D) A structure-based sequence alignment of GETV-E2, SINV-E2, RRV-E2, and SFV-E2 is shown. The red border and asterisk indicate the conserved K253 residues. The intensity of the bands of E2 was determined by ImageJ and normalized to those of β-actin. The data are representative of three independent experiments. *, P <0.05, **, P <0.01, ***, P <0.001, ****, P <0.0001.

Fig. S2. Mono-ADP ribosyltransferase function is not necessary for the antiviral activity. (A) A structure-based sequence alignment of the catalytic domains of PARP1, PARP3, PARP10, and PARP12 is shown. Blue borders indicate structurally conserved regions. Asterisks indicate the residues of the conserved H-Y residues. (B) Schematic of TIPARP-PARP mutants: PARP(H320A), PARP(Y352A), and PARP (H320A/Y352A). (C and D) HEK-293T cells were transfected with TIPARP-PARP mutants or empty vectors for 24 h and then infected with GETV-FJ (MOI of 0.1) for 24 h. (C) Western blotting analysis of C and PARP mutant protein level change. (D) The titer of viruses released into the supernatant was determined by TCID50. Data are shown as mean ± SD from three independent experiments. *, P <0.05, **, P <0.01, ***, P <0.001, ****, P <0.0001.

Table S1. Differentially expressed genes upon GETV infection.

Table S2. FPKM of expressed genes upon GETV infection.

ASM does not own the copyrights to Supplemental Material that may be linked to, or accessed through, an article. The authors have granted ASM a non-exclusive, world-wide license to publish the Supplemental Material files. Please contact the corresponding author directly for reuse.

REFERENCES

- 1. Wang A, Zhou F, Liu C, Gao D, Qi R, Yin Y, Liu S, Gao Y, Fu L, Xia Y, Xu Y, Wang C, Liu Z. 2022. Structure of infective Getah virus at 2.8 Å resolution determined by cryo-electron microscopy. Cell Discov 8:12. doi: 10.1038/s41421-022-00374-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Lanciotti RS, Ludwig ML, Rwaguma EB, Lutwama JJ, Kram TM, Karabatsos N, Cropp BC, Miller BR. 1998. Emergence of epidemic O'nyong-nyong fever in Uganda after a 35-year absence: genetic characterization of the virus. Virology 252:258–268. doi: 10.1006/viro.1998.9437 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Silva LA, Dermody TS. 2017. Chikungunya virus: epidemiology, replication, disease mechanisms, and prospective intervention strategies. J Clin Invest 127:737–749. doi: 10.1172/JCI84417 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Diagne CT, Bengue M, Choumet V, Hamel R, Pompon J, Missé D. 2020. Mayaro virus pathogenesis and transmission mechanisms. Pathogens 9:738. doi: 10.3390/pathogens9090738 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Shi N, Zhu X, Qiu X, Cao X, Jiang Z, Lu H, Jin N. 2022. Origin, genetic diversity, adaptive evolution and transmission dynamics of Getah virus. Transbound Emerg Dis 69:e1037–e1050. doi: 10.1111/tbed.14395 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Li YY, Liu H, Fu SH, Li XL, Guo XF, Li MH, Feng Y, Chen WX, Wang LH, Lei WW, Gao XY, Lv Z, He Y, Wang HY, Zhou HN, Wang GQ, Liang GD. 2017. From discovery to spread: the evolution and phylogeny of Getah virus. Infect Genet Evol 55:48–55. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2017.08.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Fukunaga Y, Kumanomido T, Kamada M. 2000. Getah virus as an equine pathogen. Vet Clin North Am Equine Pract 16:605–617. doi: 10.1016/s0749-0739(17)30099-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Lu G, Ou J, Ji J, Ren Z, Hu X, Wang C, Li S. 2019. Emergence of Getah virus infection in horse with fever in China, 2018. Front Microbiol 10:1416. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2019.01416 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Shi N, Li L-X, Lu R-G, Yan X-J, Liu H. 2019. Highly pathogenic swine Getah virus in blue foxes, Eastern China, 2017. Emerg Infect Dis 25:1252–1254. doi: 10.3201/eid2506.181983 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Shibata I, Hatano Y, Nishimura M, Suzuki G, Inaba Y. 1991. Isolation of Getah virus from dead fetuses extracted from a naturally infected sow in Japan. Vet Microbiol 27:385–391. doi: 10.1016/0378-1135(91)90162-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Doherty RL, Gorman BM, Whitehead RH, Carley JG. 1966. Studies of arthropod-borne virus infections in Queensland. V. survey of antibodies to group a arboviruses in man and other animals. Aust J Exp Biol Med Sci 44:365–377. doi: 10.1038/icb.1966.35 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Li Y, Fu S, Guo X, Li X, Li M, Wang L, Gao X, Lei W, Cao L, Lu Z, He Y, Wang H, Zhou H, Liang G. 2019. Serological survey of Getah virus in domestic animals in Yunnan province, China. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis 19:59–61. doi: 10.1089/vbz.2018.2273 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Liu H, Zhang X, Li L-X, Shi N, Sun X, Liu Q, Jin N-Y, Si X. 2019. First isolation and characterization of Getah virus from cattle in northeastern China. BMC Vet Res 15:320. doi: 10.1186/s12917-019-2061-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Yago K, Hagiwara S, Kawamura H, Narita M. 1987. A fatal case in newborn piglets with Getah virus infection: pathogenicity of the isolate. Nihon Juigaku Zasshi 49:989–994. doi: 10.1292/jvms1939.49.989 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Xing C, Jiang J, Lu Z, Mi S, He B, Tu C, Liu X, Gong W. 2020. Isolation and characterization of Getah virus from pigs in Guangdong province of China. Transbound Emerg Dis. doi: 10.1111/tbed.13567 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kamada M, Ando Y, Fukunaga Y, Kumanomido T, Imagawa H, Wada R, Akiyama Y. 1980. Equine Getah virus infection: isolation of the virus from racehorses during an enzootic in Japan. Am J Trop Med Hyg 29:984–988. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1980.29.984 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Sam SS, Teoh BT, Chee CM, Mohamed-Romai-Noor NA, Abd-Jamil J, Loong SK, Khor CS, Tan KK, AbuBakar S. 2018. A quantitative reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction for detection of Getah virus. Sci Rep 8:17632. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-36043-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Wang N, Zhai X, Li X, Wang Y, He WT, Jiang Z, Veit M, Su S. 2022. Attenuation of Getah virus by a single amino acid substitution at residue 253 of the E2 protein that might be part of a new heparan sulfate binding site on alphaviruses. J Virol 96:e0175121. doi: 10.1128/jvi.01751-21 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Rayner JO, Dryga SA, Kamrud KI. 2002. Alphavirus vectors and vaccination. Rev Med Virol 12:279–296. doi: 10.1002/rmv.360 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Ren T, Min X, Mo Q, Wang Y, Wang H, Chen Y, Ouyang K, Huang W, Wei Z. 2022. Construction and characterization of a full-length infectious clone of Getah virus in vivo. Virol Sin 37:348–357. doi: 10.1016/j.virs.2022.03.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Wang M, Sun Z, Cui C, Wang S, Yang D, Shi Z, Wei X, Wang P, Sun W, Zhu J, Li J, Du B, Liu Z, Wei L, Liu C, He X, Wang X, Zhang X, Wang J. 2022. Structural insights into alphavirus assembly revealed by the cryo-EM structure of Getah virus. Viruses 14:327. doi: 10.3390/v14020327 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Cho B, Jeon BY, Kim J, Noh J, Kim J, Park M, Park S. 2008. Expression and evaluation of Chikungunya virus E1 and E2 envelope proteins for serodiagnosis of Chikungunya virus infection. Yonsei Med J 49:828–835. doi: 10.3349/ymj.2008.49.5.828 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Tsetsarkin KA, Vanlandingham DL, McGee CE, Higgs S. 2007. A single mutation in Chikungunya virus affects vector specificity and epidemic potential. PLoS Pathog 3:e201. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.0030201 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Kielian M, Rey FA. 2006. Virus membrane-fusion proteins: more than one way to make a hairpin. Nat Rev Microbiol 4:67–76. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1326 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Byrd EA, Kielian M. 2017. An alphavirus E2 membrane-proximal domain promotes envelope protein lateral interactions and virus budding. mBio 8:e01564-17. doi: 10.1128/mBio.01564-17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Garoff H, Sjöberg M, Cheng RH. 2004. Budding of alphaviruses. Virus Res 106:103–116. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2004.08.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Schreiber V, Dantzer F, Ame J-C, de Murcia G. 2006. Poly(ADP-ribose): novel functions for an old molecule. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 7:517–528. doi: 10.1038/nrm1963 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Aravind L. 2001. The WWE domain: a common interaction module in protein ubiquitination and ADP ribosylation. Trends Biochem Sci 26:273–275. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(01)01787-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Gao G, Guo X, Goff SP. 2002. Inhibition of retroviral RNA production by ZAP, a CCCH-type zinc finger protein. Science 297:1703–1706. doi: 10.1126/science.1074276 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Bick MJ, Carroll J-WN, Gao G, Goff SP, Rice CM, MacDonald MR. 2003. Expression of the zinc-finger antiviral protein inhibits alphavirus replication. J Virol 77:11555–11562. doi: 10.1128/jvi.77.21.11555-11562.2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Guo X, Ma J, Sun J, Gao G. 2007. The zinc-finger antiviral protein recruits the RNA processing exosome to degrade the target mRNA. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 104:151–156. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0607063104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Zhang Y, Burke CW, Ryman KD, Klimstra WB. 2007. Identification and characterization of interferon-induced proteins that inhibit alphavirus replication. J Virol 81:11246–11255. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01282-07 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Xuan Y, Liu L, Shen S, Deng H, Gao G. 2012. Zinc finger antiviral protein inhibits murine gammaherpesvirus 68 M2 expression and regulates viral latency in cultured cells. J Virol 86:12431–12434. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01514-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Kozaki T, Komano J, Kanbayashi D, Takahama M, Misawa T, Satoh T, Takeuchi O, Kawai T, Shimizu S, Matsuura Y, Akira S, Saitoh T. 2017. Mitochondrial damage elicits a TCDD-inducible poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase-mediated antiviral response. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 114:2681–2686. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1621508114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Yamada T, Horimoto H, Kameyama T, Hayakawa S, Yamato H, Dazai M, Takada A, Kida H, Bott D, Zhou AC, Hutin D, Watts TH, Asaka M, Matthews J, Takaoka A. 2016. Constitutive aryl hydrocarbon receptor signaling constrains type I interferon-mediated antiviral innate defense. Nat Immunol 17:687–694. doi: 10.1038/ni.3422 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Grunewald ME, Shaban MG, Mackin SR, Fehr AR, Perlman S. 2020. Murine coronavirus infection activates the aryl hydrocarbon receptor in an indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase-independent manner, contributing to cytokine modulation and proviral TCDD-inducible-PARP expression. J Virol 94:e01743-19. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01743-19 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Rippmann JF, Damm K, Schnapp A. 2002. Functional characterization of the poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase activity of tankyrase 1, a potential regulator of telomere length. J Mol Biol 323:217–224. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(02)00946-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Smith S, Giriat I, Schmitt A, de Lange T. 1998. Tankyrase, a poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase at human telomeres. Science 282:1484–1487. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5393.1484 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Kleine H, Poreba E, Lesniewicz K, Hassa PO, Hottiger MO, Litchfield DW, Shilton BH, Lüscher B. 2008. Substrate-assisted catalysis by PARP10 limits its activity to mono-ADP-ribosylation. Mol Cell 32:57–69. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.08.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Gyrd-Hansen M. 2017. All roads lead to ubiquitin. Cell Death Differ 24:1135–1136. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2017.93 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Liu J, Qian C, Cao X. 2016. Post-translational modification control of innate immunity. Immunity 45:15–30. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2016.06.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Wang S, Yu M, Liu A, Bao Y, Qi X, Gao L, Chen Y, Liu P, Wang Y, Xing L, Meng L, Zhang Y, Fan L, Li X, Pan Q, Zhang Y, Cui H, Li K, Liu C, He X, Gao Y, Wang X, Mounce B. 2021. TRIM25 inhibits infectious bursal disease virus replication by targeting VP3 for ubiquitination and degradation. PLoS Pathog 17:e1009900. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1009900 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Bauer J, Bakke O, Morth JP. 2017. Overview of the membrane-associated RING-CH (MARCH) E3 ligase family. N Biotechnol 38:7–15. doi: 10.1016/j.nbt.2016.12.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Hatakeyama S. 2017. TRIM family proteins: roles in autophagy, immunity, and carcinogenesis. Trends Biochem Sci 42:297–311. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2017.01.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Rohde JR, Breitkreutz A, Chenal A, Sansonetti PJ, Parsot C. 2007. Type III secretion effectors of the IpaH family are E3 ubiquitin ligases. Cell Host Microbe 1:77–83. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2007.02.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Hatakeyama S, Yada M, Matsumoto M, Ishida N, Nakayama KI. 2001. U box proteins as a new family of ubiquitin-protein ligases. J Biol Chem 276:33111–33120. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M102755200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Huibregtse JM, Scheffner M, Beaudenon S, Howley PM. 1995. A family of proteins structurally and functionally related to the E6-AP ubiquitin-protein ligase. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 92:2563–2567. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.11.5249-b [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Lin H, Li S, Shu HB. 2019. The membrane-associated MARCH E3 ligase family: emerging roles in immune regulation. Front Immunol 10:1751. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2019.01751 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Zheng C, Tang YD. 2021. When MARCH family proteins meet viral infections. Virol J 18:49. doi: 10.1186/s12985-021-01520-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Lun CM, Waheed AA, Majadly A, Powell N, Freed EO. 2021. Mechanism of viral glycoprotein targeting by membrane-associated RING-CH proteins. mBio 12:mBio doi: 10.1128/mBio.00219-21 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Tada T, Zhang Y, Koyama T, Tobiume M, Tsunetsugu-Yokota Y, Yamaoka S, Fujita H, Tokunaga K. 2015. MARCH8 inhibits HIV-1 infection by reducing virion incorporation of envelope glycoproteins. Nat Med 21:1502–1507. doi: 10.1038/nm.3956 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Yu C, Li S, Zhang X, Khan I, Ahmad I, Zhou Y, Li S, Shi J, Wang Y, Zheng Y-H, Einav S, Diamond MS. 2020. MARCH8 inhibits Ebola virus glycoprotein, human immunodeficiency virus type 1 envelope glycoprotein, and avian influenza virus H5N1 hemagglutinin maturation. mBio 11. doi: 10.1128/mBio.01882-20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Atasheva S, Akhrymuk M, Frolova EI, Frolov I. 2012. New PARP gene with an anti-alphavirus function. J Virol 86:8147–8160. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00733-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Teng T-S, Foo S-S, Simamarta D, Lum F-M, Teo T-H, Lulla A, Yeo NKW, Koh EGL, Chow A, Leo Y-S, Merits A, Chin K-C, Ng LFP. 2012. Viperin restricts Chikungunya virus replication and pathology. J Clin Invest 122:4447–4460. doi: 10.1172/JCI63120 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Ma Q, Baldwin KT, Renzelli AJ, McDaniel A, Dong L. 2001. TCDD-inducible poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase: a novel response to 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 289:499–506. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2001.5987 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Guo X, Carroll J-WN, Macdonald MR, Goff SP, Gao G. 2004. The zinc finger antiviral protein directly binds to specific viral mRNAs through the CCCH zinc finger motifs. J Virol 78:12781–12787. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.23.12781-12787.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Müller S, Möller P, Bick MJ, Wurr S, Becker S, Günther S, Kümmerer BM. 2007. Inhibition of filovirus replication by the zinc finger antiviral protein. J Virol 81:2391–2400. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01601-06 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Mao R, Nie H, Cai D, Zhang J, Liu H, Yan R, Cuconati A, Block TM, Guo J-T, Guo H, Siddiqui A. 2013. Inhibition of hepatitis B virus replication by the host zinc finger antiviral protein. PLoS Pathog 9:e1003494. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003494 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Wang Z, Michaud GA, Cheng Z, Zhang Y, Hinds TR, Fan E, Cong F, Xu W. 2012. Recognition of the iso-ADP-ribose moiety in poly(ADP-ribose) by WWE domains suggests a general mechanism for poly(ADP-ribosyl)ation-dependent ubiquitination. Genes Dev 26:235–240. doi: 10.1101/gad.182618.111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Sawyer SL, Wu LI, Emerman M, Malik HS. 2005. Positive selection of primate TRIM5alpha identifies a critical species-specific retroviral restriction domain. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 102:2832–2837. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0409853102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Kerns JA, Emerman M, Malik HS. 2008. Positive selection and increased antiviral activity associated with the PARP-containing isoform of human zinc-finger antiviral protein. PLoS Genet 4:e21. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.0040021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Zhang Y, Ozono S, Tada T, Tobiume M, Kameoka M, Kishigami S, Fujita H, Tokunaga K, Kalia M. 2022. MARCH8 targets cytoplasmic lysine residues of various viral envelope glycoproteins. Microbiol Spectr 10. doi: 10.1128/spectrum.00618-21 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Ren SC, Qazi SA, Towell B, Wang JC-Y, Mukhopadhyay S. 2022. Mutations at the alphavirus E1'-E2 interdimer interface have host-specific phenotypes. J Virol 96:e0214921. doi: 10.1128/jvi.02149-21 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Li L, Jose J, Xiang Y, Kuhn RJ, Rossmann MG. 2010. Structural changes of envelope proteins during alphavirus fusion. Nature 468:705–708. doi: 10.1038/nature09546 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Wahlberg JM, Boere WA, Garoff H. 1989. The heterodimeric association between the membrane proteins of Semliki forest virus changes its sensitivity to low pH during virus maturation. J Virol 63:4991–4997. doi: 10.1128/JVI.63.12.4991-4997.1989 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]