ABSTRACT

All adeno-associated virus (AAV) vectors currently used in clinical trials or approved gene therapy biologics are based on human or non-human primate AAVs. A major challenge for AAV gene therapy is the high prevalence of circulating neutralizing antibodies (NAbs) in the general population targeting the virus capsids leading to vector inactivation and a loss of treatment efficacy. A strategy to escape detection by NAbs is the utilization of AAVs that do not disseminate in the primate population and exhibit low or no antigenicity. One such example is avian AAV (AAAV), which was first identified in preparations of the Olson strain of quail bronchitis, an avian adenovirus. AAAV shows very low sequence identities (~54–58%) to the AAV serotypes including to the sequences of the structurally diverse AAV4 and AAV5. In this study, the structure of empty and genome-filled AAAV capsids was determined by cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM) at 2.5 and 3.1 Å resolution. Furthermore, AAAV was found to utilize galactose for cell attachment, similar to AAV9 and AAVrh.10. Characterization of AAAV’s antigenic properties revealed that 30% of human sera from healthy individuals were capable of neutralizing transduction. This high rate of antigenicity is caused by conserved epitopes around the fivefold channel of the capsid allowing cross-reactivity of NAbs. This was further confirmed by mapping a cross-reactive human anti-AAV9 monoclonal antibody using cryo-EM. This structure-function characterization will be beneficial to further expand the current repertoire of AAV vectors in human gene therapy applications.

Importance

AAVs are extensively studied as promising therapeutic gene delivery vectors. In order to circumvent pre-existing antibodies targeting primate-based AAV capsids, the AAAV capsid was evaluated as an alternative to primate-based therapeutic vectors. Despite the high sequence diversity, the AAAV capsid was found to bind to a common glycan receptor, terminal galactose, which is also utilized by other AAVs already being utilized in gene therapy trials. However, contrary to the initial hypothesis, AAAV was recognized by approximately 30% of human sera tested. Structural and sequence comparisons point to conserved epitopes in the fivefold region of the capsid as the reason determinant for the observed cross-reactivity.

KEYWORDS: adeno-associated virus, cryo-EM, capsid, parvovirus, AAV vector, gene therapy, avian viruses, antigenicity, three-dimensional structure

INTRODUCTION

Adeno-associated viruses (AAVs) are single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) viruses in the genus Dependoparvovirus in the Parvoviridae family (1). The AAVs are non-pathogenic viruses that require coinfection with a helper virus, such as adenovirus or herpesvirus, to complete their replication cycle (2). Their ~4.7 kb genome is packaged into icosahedral capsids with T = 1 symmetry and diameters of ~250 Å (3). The AAV genome contains two identical inverted terminal repeats (ITRs) on both ends, which flank the rep and cap genes. The rep gene codes for a series of Rep proteins that are involved in transcription, genome replication, and packaging (4, 5). The capsid proteins are expressed from the cap gene, which expresses three viral proteins (VPs), VP1, VP2, and VP3, at a ratio of approximately 1:1:10 (6). These VPs overlap at their C-termini with the smallest protein, VP3 (~60 kDa), completely contained in VP1 (~82 kDa) and VP2 (~67 kDa). The latter are N-terminal extended forms of VP3, with a region shared between VP1 and VP2 (VP1/2 common region), and a unique region for VP1 (VP1u). The shared VP3 region is important for capsid assembly and 60 copies of these, regardless of the N-terminal extensions, are incorporated into a single capsid. The N-terminal extensions of VP1 and VP2 contain essential functions such as a phospholipase A2 (PLA2) enzyme domain and multiple nuclear localization signals, that are required for successful transduction of the virus (7, 8).

Dependoparvoviruses have been isolated from a wide range of animals, including humans, non-human primates, cattle, goats, pigs, sea lions, foxes, bats, rodents, birds, and reptiles (9 – 20). The amino acid sequence identity of the VPs from different AAVs can vary by up to 50% (21). The structures of the capsids from several AAVs have been determined utilizing either x-ray crystallography or cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM) (6, 22 – 27). For all AAV capsids, structural ordering is only observed for the shared VP3 region, which consists of a conserved core that is composed of an eight-stranded (βB to βI), anti-parallel β-barrel motif, an additional βA strand, and an alpha-helix (αA) between βC and βD. Additionally, loops are inserted between the β strands, with high amino acid sequence and structural variability for the different AAVs, that form the surface of the capsids. A total of nine variable regions (VRs) have been defined (28). Despite the differences in their surface loops, the AAVs share overall similar morphologies and the capsids are assembled via two-, three-, and fivefold symmetry-related VP interactions. The icosahedral fivefold symmetry axes are surrounded by five loops that form the cylindrical channels, which connect the interior of the capsid to the exterior environment. This portal is believed to be the route of genomic DNA packaging/ejection and VP1u externalization (29). Large protrusions surround the threefold symmetry axes; at the twofold axes and surrounding the fivefold channels, the AAV capsids possess depressions that are separated by raised regions, which are termed 2/5-fold walls. The differences in amino acid sequences and structural variations between different AAV capsids are responsible for alternative receptor usage leading to distinct host or tissue tropisms and determining their antigenic profiles.

The AAVs are extensively studied due to their utilization as vectors for gene delivery applications, particularly for the treatment of monogenetic diseases (5). Currently, seven gene therapy biologics based on AAV vectors have been approved for commercialization: Glybera, an AAV1 vector for the treatment of lipoprotein lipase deficiency by the European Medicines Agency (EMA); Luxturna, an AAV2 vector for the treatment of Leber’s congenital amaurosis by both the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and EMA; Zolgensma, an AAV9 vector for the treatment of spinal muscular atrophy type 1 by both the FDA and EMA; Upstaza, an AAV2 vector for the treatment of aromatic L-amino acid decarboxylase deficiency by the EMA; Roctavian, an AAV5 vector for the treatment of hemophilia A by the EMA; Hemgenix, an AAV5 vector for the treatment of hemophilia B by the FDA; and Elevidys, an AAVrh74 vector for the treatment of Duchenne muscular dystrophy by the FDA (30 – 36).

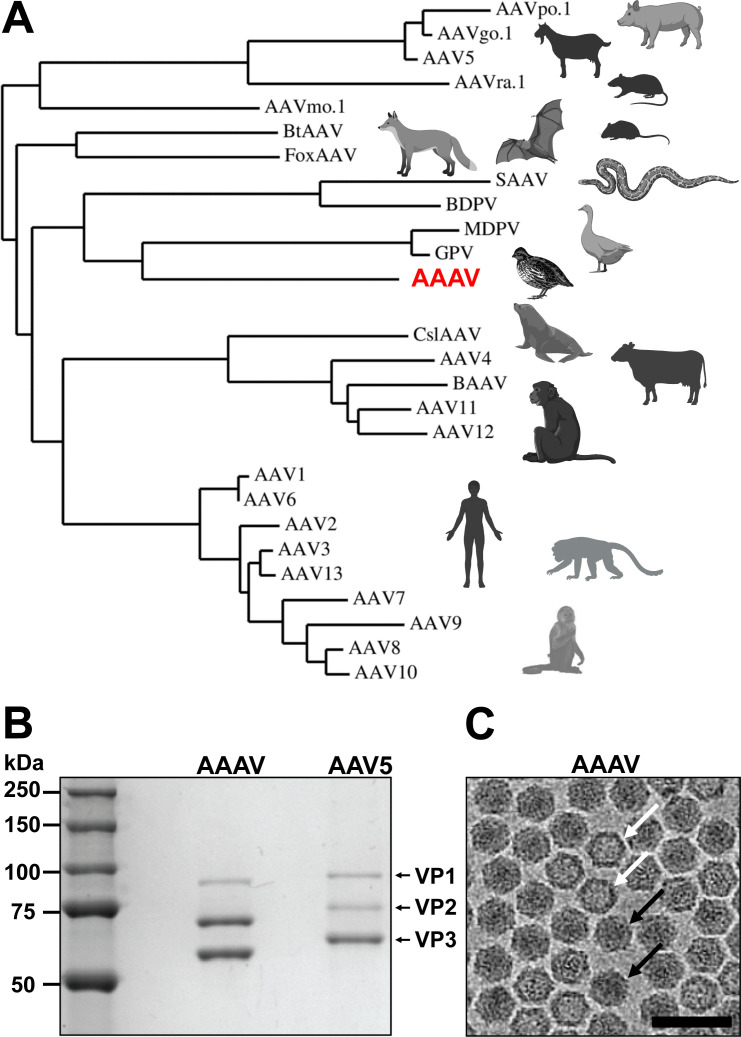

One issue undermining the broad use of AAVs in the clinical setting is the high prevalence of circulating neutralizing antibodies (NAbs) in the human population targeting the virus capsids, resulting in vector inactivation and a reduction in treatment efficacy (37). A potential strategy to escape detection by the NAbs is the utilization of AAVs that do not naturally circulate in the primate population and exhibit low or no reactivity with human sera (HS). Avian AAV (AAAV) is a promising candidate, due to the significant sequence differences between the AAAV capsid and primate-based AAVs (Fig. 1A) and no or low reactivity to human sera is expected. However, serological studies have provided evidence that AAAV infections are not restricted to avian species and have been detected in poultry workers (38). The virus was first identified and isolated from preparations of the Olson strain of quail bronchitis, an avian adenovirus affecting bobwhite quails (39). Phylogenic analysis based on its VP1 amino acid sequences puts AAAV on the same branch as other avian dependoparvoviruses, such as Muscovy duck parvovirus (MDPV) and goose parvovirus (GPV) (Fig. 1A).

Fig 1.

Production and purification of AAAV viral capsids. (A) A two-dimensional dendrogram is shown, constructed using the hierarchical clustering analysis platform Phylogeny.fr (40) and the VP1 amino acid sequences of selected dependoparvoviruses. (B) SDS gel of purified AAAV. AAV5 was loaded as a control. The position of VP1, VP2, and VP3 is indicated. The VPs of AAV5 are known to migrate higher than their actual molecular weight (41), despite being 1–3 kDa lower compared to AAAV. (C) Cryo-EM micrograph with full (black arrow) and empty (white arrow) AAAV capsids. Scale bar: 500 Å.

This study characterizes the full and empty capsid structures of AAAV and compares its structural topology and antigenic characteristics to AAV2, AAV5, and AAV9. These AAVs were selected as a comparison to AAAV because these serotypes have all already been approved as gene therapy biologics. The genome-containing and empty viral capsid structures of AAAV were determined by cryo-EM and 3D image reconstruction to 3.06 Å and 2.54 Å resolution, respectively. The AAAV capsid maintained the general features previously characterized for other AAVs. However, unlike previous comparisons of empty and full capsids, structural differences at the N-terminus and the VR-IX surface loop were observed. Further characterizations identified terminal galactose as a potential glycan receptor and showed significant cross-reactivity of fivefold binding antibodies to the AAAV capsid.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

AAAV vectors can be generated using the standard AAV production system

Previous AAAV vector preparations were produced utilizing the AAAV rep and cap genes, co-transfected with a vector genome cassette flanked by the AAAV-ITRs (42). In contrast, most AAV manufacturing systems utilize AAV2-rep and AAV2-ITR vector genomes. In order to determine if the capsids of AAAV are compatible with these standard components, we cloned the AAAV cap gene downstream of an AAV2 rep containing plasmid. During cloning, DNA sequence differences compared to the deposited AAAV sequence were discovered, likely due to sequencing mistakes in the past, leading to eight amino acid differences in VP3 and an additional difference within the VP1/2 common region. The nucleotide sequence of AAAV VP was updated: NC_004828. The new construct was transfected into HEK293 cells along with an AAV2-ITR vector genome cassette and pHelper.

Subsequently, AAAV vectors were produced using the new construct and purified by iodixanol gradient ultracentrifugation. Purification by AVB affinity chromatography (43) was also attempted; however, >98% of all loaded AAAV vectors were detected in the flowthrough or wash fractions indicating that the binding epitope for AVB is not conserved in AAAV. The purity of the iodixanol gradient-purified AAAV sample was verified by SDS-PAGE and showed VP1, VP2, and VP3 at the expected sizes of ~83, 67, and 60 kDa (Fig. 1B). Interestingly, the molar ratio of VP1:VP2:VP3 incorporated into the AAAV capsids differed from the common 1:1:10 ratio usually described for the AAV serotypes (44 – 47). In the case of AAAV, VP2 and VP3 are almost equally incorporated resulting in an estimated 1:5:5 ratio (Fig. 1B). While the start codons for VP2 (ACG) and VP3 (ATG) are similar to other AAVs, the upstream sequences vary and could lead to differences in translation initiation efficiency. Previous studies utilizing AAAV vectors did not show their purified preparations with an SDS-PAGE, preventing a direct comparison (17).

The empty and full AAAV capsid structures display structural differences

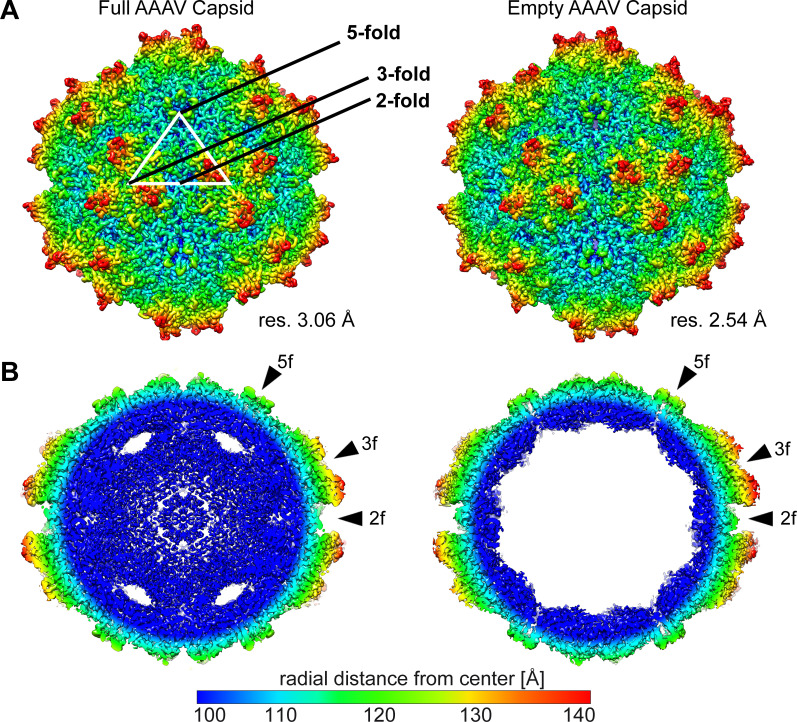

Cryo-EM micrographs of the purified sample showed intact particles of ~250 Å in diameter (Fig. 1C). Thus, the AAAV sample was deemed suitable for structural determination by cryo-EM. Furthermore, full (genome-containing) and empty capsids (no genome) could be observed, which could be differentiated by their dark (full) and light (empty) interior appearances. Thus, following cryo-EM data collection, both types of particles were extracted separately and reconstructed independently. In total, 11,240 full particles and 38,672 empty capsids were extracted from the micrographs and used for 3D-image reconstruction to 3.06 Å and 2.54 Å resolution, respectively (Fig. 2A; Table 1). Both the empty and full AAAV capsids displayed the characteristic capsid features of other AAV serotypes, such as AAV2, AAV5, and AAV9 despite low amino acid sequence identities of 54–57% (for VP1). These features include a channel at each fivefold symmetry axis, trimeric protrusions surrounding each threefold symmetry axis, and a depression at each twofold symmetry axis. Between the empty and full AAAV capsids, no significant difference can be observed on the capsid surface (Fig. 2A). In contrast, major differences can be observed in the interior of the capsids in a cross-sectional view (Fig. 2B). The full capsids showed a significant amount of density, likely contributed by the packaged DNA genome, which is absent from the corresponding empty map. Similar to all the previously reported genome-containing AAV capsid structures, a lack of density is observed underneath the fivefold channel (22, 26, 27). It was hypothesized that the structurally dynamic VP1u and VP1/VP2 common regions occupy this space prior to their proposed externalization via the fivefold channel, which is required for its PLA2 enzyme function during the viral life cycle (29).

Fig 2.

Genome-containing and empty AAAV capsid structures. (A) Capsid surface density maps determined by cryo-EM reconstruction contoured at a sigma (σ) threshold level of 1. The resolutions of the structures are calculated based on an FSC threshold of 0.143. The reconstructed maps are radially colored (blue to red) according to distance to the particle center, as indicated by the scale bar below. The icosahedral two, three, and fivefold symmetry axes are indicated on the full AAAV capsid map. (B) Cross-sectional views of the reconstructed maps from genome-containing and empty particles contoured at a σ-threshold level of 0.9. The positions of some icosahedral two-, three-, and fivefold symmetry axes are indicated by arrowheads. This figure was generated using UCSF-Chimera (48).

TABLE 1.

Summary of cryo-EM data collection, image processing, and refinement statistics

| Processing and refinement parameters | AAAV | |

|---|---|---|

| Full | Empty | |

| Total number of micrographs | 1,586 | |

| Defocus range (µm) | 0.4–3.0 | |

| Total electron dose (e-/Å2) | 61 | |

| Frames/micrograph | 50 | |

| Pixel size (Å/pixel) | 1.06 | |

| Particles used for final map | 11,240 | 38,672 |

| Resolution of final map (Å) | 3.06 | 2.54 |

| Refinement statistics | ||

| Map CC | 0.882 | 0.819 |

| RMSD a bonds (Å) | 0.01 | 0.01 |

| RMSD angles (˚) | 0.76 | 0.82 |

| All-atom clashscore | 10.02 | 11.88 |

| Ramachandran plot (%) | ||

| Outliers | 0 | 0 |

| Allowed | 2.3 | 2.7 |

| Favored | 97.7 | 97.3 |

| Rotamer outliers | 0 | 0 |

| C-beta deviations | 0 | 0 |

RMSD: root mean square deviation

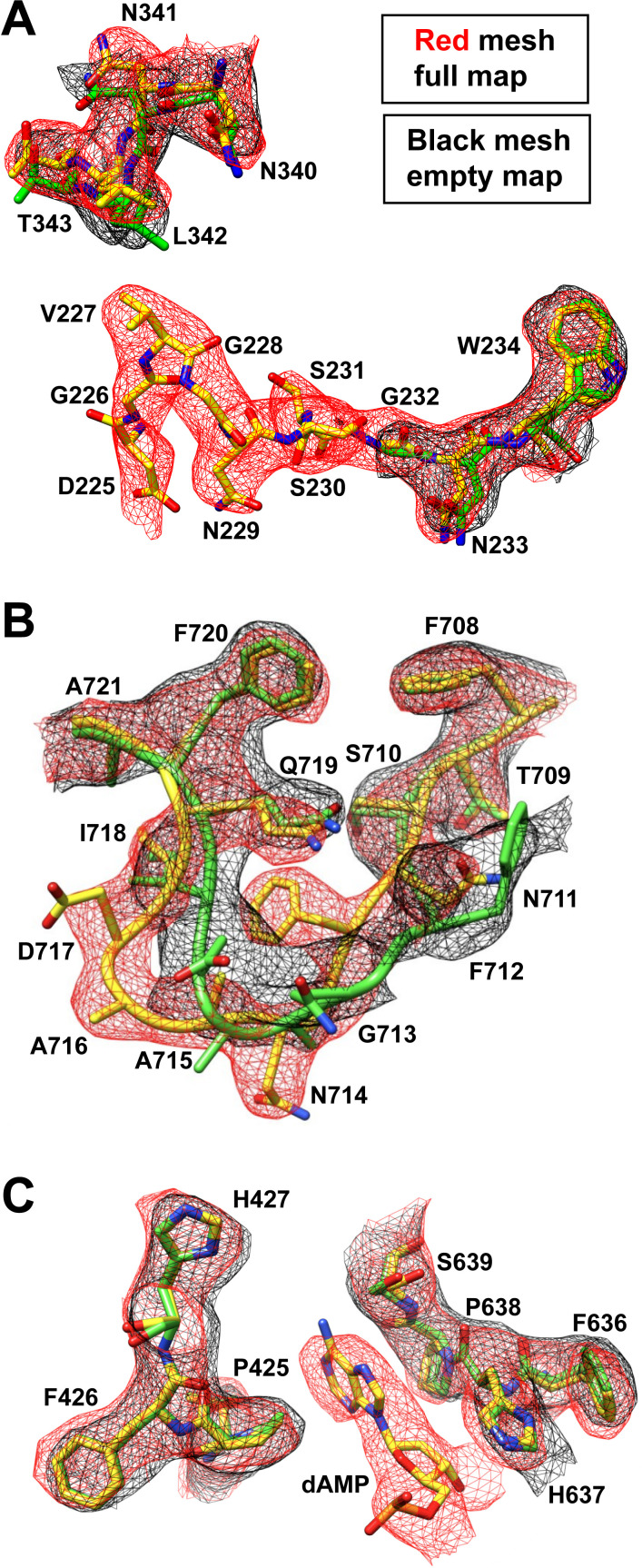

The high-resolution density maps allowed the unbiased fitting of the VP sequence into the density maps. In the case of the genome-containing capsids, structural ordering at the N-terminus begins with aspartic acid D225 (Fig. 3A), which is equivalent (±1 aa) to most AAV VP structures determined to date (27). In contrast, in the density map for the empty capsids, structural ordering starts with glycine G232. The higher disorder of the N-terminus in the empty map is unusual and has not been observed in any other empty AAV capsid structures (22, 26). However, a similar disorder was described previously for the serpentine AAV (SAAV) capsid at low pH conditions (49) and for various AAV2 capsid structures with single amino acid substitutions (50 – 52). A common feature of all these structures including the empty AAAV capsids is secondary rearrangements in the fivefold region due to the disordered N-terminus such as the movement of the DE-loop base (Fig. 3B) and the alternative side chain orientation of arginine R410 (AAAV), R395 (SAAV), or R404 (AAV2), respectively. For the remaining VP structure of the empty or full AAAV capsids, the amino acid main chain and side chains adopted identical conformations except for VR-IX (Fig. 3B). In VR-IX, the loop diverges from asparagine N711 to isoleucine I718 with Cα distances up to 5.9 Å. Such a significant difference in a surface loop conformation between empty and full capsids has not been observed previously and was not expected. This loop has been associated with cellular transduction, antigenicity, and transcription in various AAV serotypes (53 – 56), but to date, no link to DNA packaging has been reported. Due to the above-described differences, the overall Cα-RMSD of the empty and full VP structure when superposed is 0.64 Å, which is higher compared to other AAV capsid structures of previous studies (~0.2–0.3 Å) (22, 26). Additionally, like all previous genome-filled AAV capsids (22, 26, 57 – 59), ordered nucleotides were observed in the conserved nucleotide binding pockets under the threefold axis, which is absent in the empty map (Fig. 3C). This is not surprising as the surrounding amino acids are completely conserved when compared to AAV1–AAV13. While the above-mentioned nucleotide, interpreted as a dAMP, between P425 and H637/P638 is ordered at ~3σ, the neighboring nucleotides are disordered due to the imposed symmetry during 3D-image reconstruction.

Fig 3.

Differences between the density maps of the empty and full AAAV capsid structures. (A) Modeled AAAV resides at the fivefold/N-terminus of AAAV (B) in VR-IX, and (C) at the DNA binding pocket (red = full, black = empty).

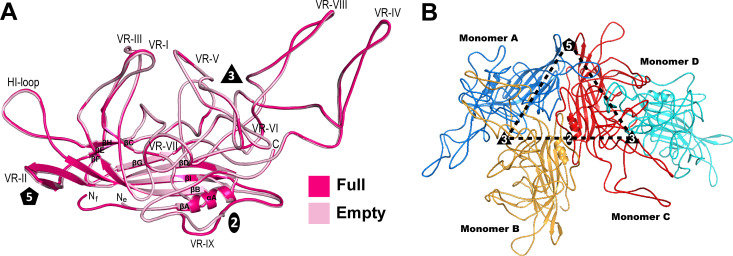

The AAAV capsid structure exhibits diversity in surface loop conformation

The AAAV VP structure conserves the core β-strand A, the eight-stranded antiparallel β-barrel (βB- βI), and the α-helix A (Fig. 4A). The N-terminus in the full map is situated below the fivefold channel and in the empty map underneath the βBIDG sheet. Large loops are inserted between the β-strands that form the surface of the capsid. The AAAV capsid is assembled from 60 VPs via two-, three-, and fivefold symmetry-related VP interactions with four VPs contributing to the asymmetric unit (Fig. 4B).

Fig 4.

AAAV VP monomer and capsid arrangement. (A) Structural superposition of AAAV full (pink) and empty (light pink) monomers is shown as ribbon diagrams with the position of VR-I to VR-IX, the HI-loop, β-strand A-I, α-helix A, the N- and C-terminus, and the icosahedral two-, three-, and fivefold axes are labeled. This image was generated using PyMOL (60). (B) Four AAAV VP monomers A–D arranged to form the intersection of the icosahedral symmetry axes at the two-, three-, and fivefold wall.

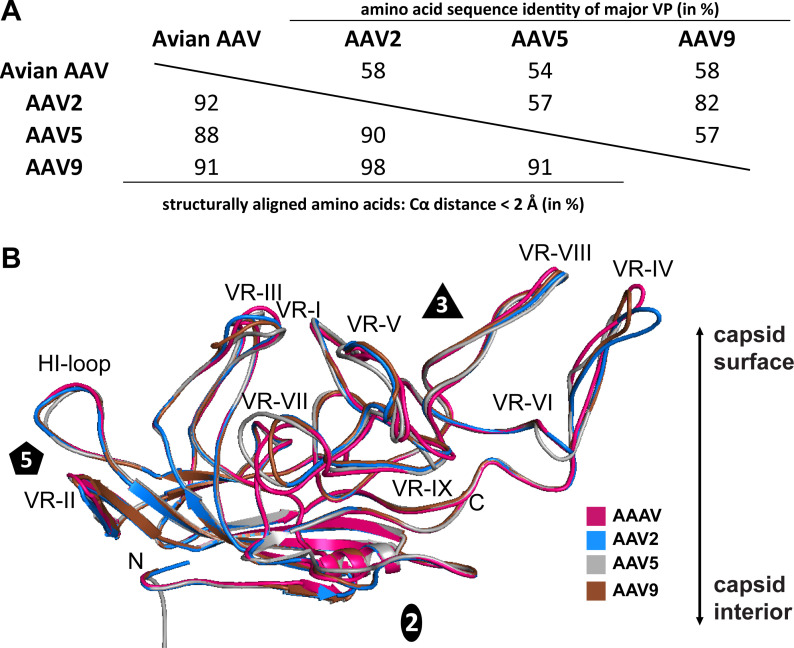

The VP1 of AAAV possesses an amino acid sequence identity of 58, 54, and 58% to AAV2, AAV5, and AAV9, respectively (Fig. 5A). However, the vast majority of amino acid differences are located in the surface loops. As a result, the capsid core is near perfectly superposable when compared to AAV2, AAV5, and AAV9, and structural variations are exclusively located in the previously defined capsid VRs (61). The most significant structural differences were found in VR-I, VR-IV, VR-V, VR-VII, and VR-IX (Fig. 5B) with Cα distances of 4–11 Å. All these loops have been previously associated with cellular transduction and antigenicity in other AAV serotypes (55, 62) suggesting alternative tropism and immunogenic properties for AAAV. In contrast, minor structural variability was observed in the fivefold region, explaining the ability of the AAV2 Rep proteins to package genomes in the diverse AAAV capsids. In fact, in the fivefold region, AAAV is more similar to AAV2 and AAV9 than AAV5 (Fig. 5B). The overall Cα-RMSDs of AAAV to AAV2, AAV5, and AAV9 are 1.49, 1.41, and 1.38 Å, with 91, 88, and 92% structurally aligned amino acids (Fig. 5A), respectively. In comparison to the previously determined non-primate AAV capsid structures of BtAAV-10HB and SAAV (26, 49), the AAAV capsid is structurally more similar to the primate AAVs, as their overall Cα-RMSDs have been described in the 1.7–1.8 Å range.

Fig 5.

Structural comparison of AAAV monomeric viral protein against AAV serotypes 2, 5, and 9. (A) Table of Cα distances and amino acid sequence identity of major VP of AAAV compared to AAV2, AAV5, and AAV9. (B) Structural superposition of AAAV (pink), AAV2 (blue), AAV5 (gray), and AAV9 (brown) shown as ribbon diagrams. The position of the N- and C-terminus, and the icosahedral two-, three-, and fivefold axes are labeled. This figure was generated using PyMol (60).

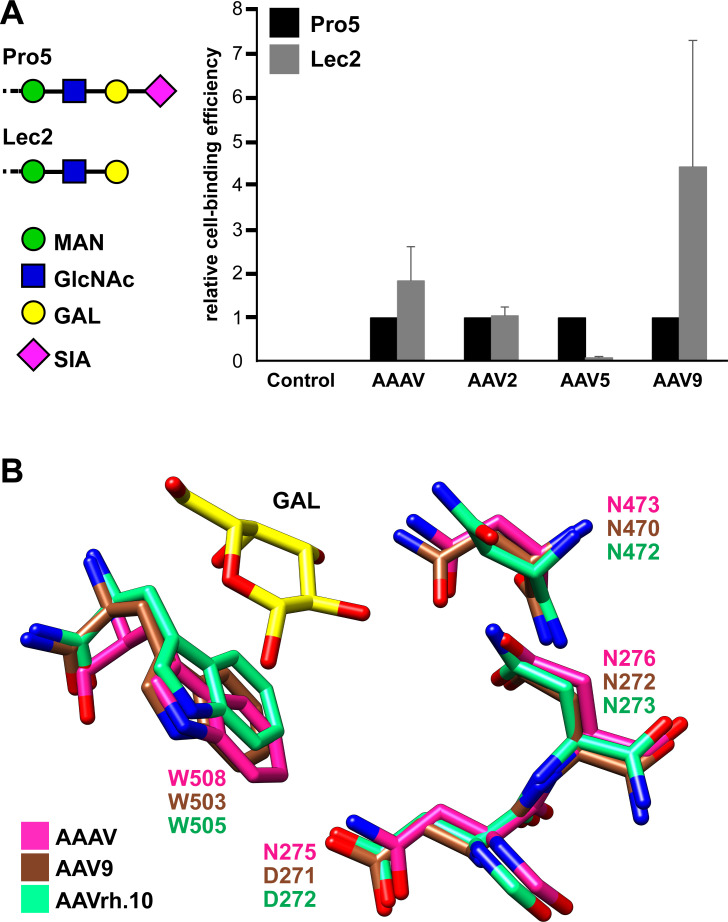

AAAV conserves the galactose binding pocket of AAV9 and AAVrh.10

Many of the AAVs utilize cell surface glycans for host cell attachment and/or entry, which subsequently determines the transduction efficiencies and tissue tropisms (55). To determine whether AAAV utilizes terminal sialic acids or galactoses, cell binding assays using differential glycan presenting Chinese Hamster Ovary (CHO) cell lines were conducted (Fig. 6A). Among the used cell lines, CHO-Pro5 displays terminal sialic acid and the related mutant CHO-Lec2 displays terminal galactose, which differs from Pro5 only by a mutation of the CMP-sialic acid transporter gene resulting in a ~98% reduced amount of sialylated glycans on the cell surface (63). The AAV2 capsid binds to heparan sulfate proteoglycan, which is present on either cell lines. Thus, binding to both cell lines was observed at approximately equal efficiency. AAV5, a known sialic acid binder, showed binding to the Pro5 cells but not to the sialic acid deficient Lec2 cell line (10-fold reduction). AAV9 showed approximately fourfold higher cell-binding ability to the Lec2 cells in comparison to the Pro5 cells, indicating that the terminal galactose is required for cell attachment. Overall, the cell binding results for AAV2, AAV5, and AAV9 are comparable to previous studies (61, 64 – 66). The cell-binding behavior of AAAV was somewhat similar to AAV9, displaying more efficient binding to the Lec2 cells compared to the Pro5 cells. However, the approximate twofold higher cell-binding ability of AAAV to the Lec2 cells was not as pronounced as it is for AAV9 (Fig. 6A). This cell binding behavior of AAAV resembles that of the AAVrh.10 capsid, which was characterized in a previous study and also showed approximately twofold higher binding efficiency of Lec2 vs Pro5 cells (21).

Fig 6.

AAAV binds to the terminal galactose glycan receptor. (A) Luciferase-packing AAV viral capsids were incubated with CHO Pro5 and Lec2 cells as described in the Materials and Methods section. The cell-binding efficiency was determined via a qPCR-based assay, detecting the luciferase gene. The results are normalized to CHO Pro5. AAV2 was tested as a positive control for all cell lines as it binds to heparan sulfate proteoglycan. AAV5 was included as a sialic acid binding control. AAV9 was included as a galactose binding control. (B) AAAV, AAV9, and AAVrh.10 all bind to the galactose glycan receptor. Comparison of the key residues involved in the galactose binding pocket for the three types of AAVs.

Subsequently, the galactose binding pocket of AAV9 and AAVrh.10 was compared to the equivalent region of the AAAV capsid (Fig. 6B). Interestingly, all the surrounding amino acids with up to ~4.5 Å distance are conserved with the exception of N275, which is D in both AAV9 and AAVrh.10. Previous studies have shown that substituting the neighboring tryptophan W503 and asparagine N470 (in AAV9) prevents the galactose binding ability of AAV9 and AAVrh.10 (21, 67). Thus, the conservation of this pocket suggests that terminal galactoses could be a potential glycan receptor for the AAAV capsid.

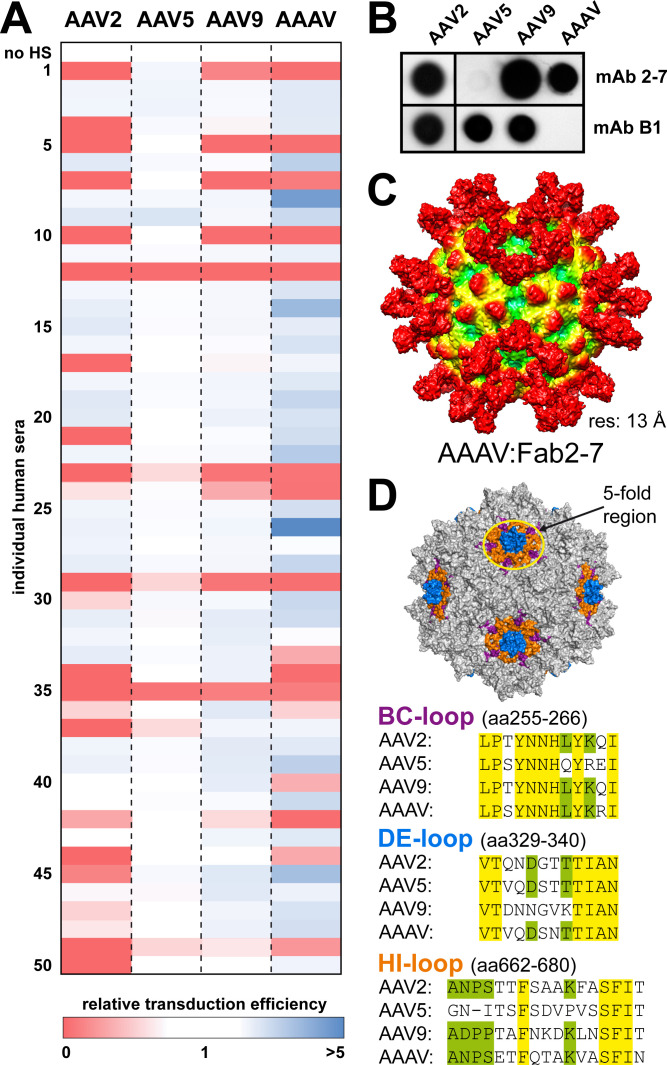

AAAV is recognized by some human sera and one AAV9-specific MAb as evidence of cross-reactivity at the fivefold region

Non-primate AAVs such as AAAV are not circulating in the human population. Due to its high amino acid sequence variability of the capsid surface, pre-existing NAbs, acquired from prior exposure to naturally circulating primate AAVs, are not expected to cross-react and neutralize vectors based on AAAV. To analyze if this is the case, a series of 50 human serum samples from healthy donors were screened against AAAV, AAV2, AAV5, and AAV9 vectors in vitro. As expected, AAV2 vectors showed the highest neutralization rate (n = 23, 46%) (Fig. 7A). It is important to note that this assay reports the neutralization potential of the human sera due to antibodies or other components of the immune system such as defensins (68). In addition, the sera may contain other antibodies that bind the AAV capsid but are unable to neutralize the AAV vectors (69). These antibodies are included in previous studies reporting the seroprevalence against the AAV serotypes and thus are in the case of AAV2 much higher (>70%) (37). The 46% neutralization rate for AAV2 is in line with previous studies that reported a 59% neutralization rate in French adults or ~30% in the United States (37, 70). On the other end of the spectrum, AAV5 showed the lowest antigenicity and was neutralized by six human sera (12%). The antigenicity of AAV9 was in between those of AAV5 and AAV2, with 11 human serum neutralizing AAV9 vectors (22%). Surprisingly, vectors based on AAAV were neutralized by 16 human sera (32%). However, the vast majority of human sera affecting AAAV also reduce the transduction of AAV2, indicating the presence of cross-neutralizing antibodies. Some human sera resulted in an enhancement of AAAV transduction higher than seen for AAV2, AAV5, or AAV9 (Fig. 7A). A possible explanation for this observation is that a different cell line had to be used for AAAV (DF-1 cells), as this capsid in its wild-type form does not transduce human cells. These cells might contain a high amount of Fc receptors enabling the uptake of AAAV by antibody-dependent enhancement, a mechanism previously described for AAVs and other parvoviruses (71 – 74).

Fig 7.

AAAV is neutralized by ~30% of human serum samples from 50 healthy individuals. (A) Neutralization assays conducted in DF-1 cells for AAAV. For AAV2, AAV5, and AAV9 neutralization assays were conducted in HEK293 cells. Cells were incubated with purified virus at an MOI = 105 in human serum samples. Normalized transduction units of AAAV, AAV2, AAV5, and AAV9 were determined by a luciferase gene reporter assay. All experiments were carried out in triplicate (n = 3). (B) Native dot immunoblots of AAAV, AAV9, and AAV5 against mAb2-7 (56) and B1 with 1010 loaded capsid particles/dot. (C) Low resolution structure of an AAAV capsid complexed with Fab2-7 determined using cryo-EM to 13 Å resolution. (D) Surface representation of the AAAV capsid highlighting the fivefold region and amino acid sequence alignments comparing the BC-loop (purple), DE-loop (blue), and HI-loop (orange) between AAV2, AAV5, AAV9, and AAAV.

Additional evidence that antibodies against the primate AAVs cross-react with AAAV came from a recent panel of monoclonal human antibodies from patients following Zolgensma treatment (56). One of the antibodies in this panel, targeting the fivefold region of the AAV9 capsid, was shown to cross-react to a wide range of AAV serotypes with the exception of AAV5. Similarly, AAAV was also recognized by this antibody as verified by native immune-dot blot (Fig. 7B) and bound to the capsid in the same way as previously shown for AAV9 (Fig. 7C) (75).

This level of cross-reactivity is the result of sequence and structural conservation on the capsid surface. As shown above, the fivefold region shows the lowest structural variability (Fig. 5A). Thus, the sequence of these surface loops was analyzed in more detail. The fivefold region is primarily composed of the DE-loop, the HI-loop, and the N-terminal part of the BC-loop (prior to VR-I) (Fig. 7D). While the overall VP sequence identity of AAAV vs AAV2 is ~58%, these loops show significant sequence similarity between the two viruses. Since AAV2 is the most prevalent AAV in the human population, antibodies neutralizing AAV2 likely also bind this region (9, 76, 77). In contrast, AAV5 shows much less cross-reactivity probability due to significant differences in the HI-loop (Fig. 5B).

Conclusions

AAVs have been extensively studied to identify host cellular factors involved in viral infection as well as AAV serotypes or variants that confer favorable transduction profiles toward gene therapy and clinical applications. Despite the advances in vector development and dose administration, barriers such as pre-existing immune response in the general human population have led to the exclusion of many patients from enrolling in gene therapy clinical trials (78 – 80). Thus, non-primate AAVs, which do not circulate in the human population, hold great potential as gene delivery vectors in comparison to primate AAVs. While the core VP features of the AAAV, such as the highly conserved β-barrel and nucleotide binding sites are maintained, the variations present in their capsid surface properties offer new tissue tropisms and the potential to evade pre-existing neutralizing antibodies. However, this strategy was not successful with AAAV. Due to the conservation in the fivefold region, a significant number of healthy human sera were capable of neutralizing the AAAV-based vectors. To circumvent these NAbs, amino acid changes in the fivefold region are required. Sequence alignments comparing the BC-, DE-, and HI-loops (Fig. 7D) allow the identification of specific amino residues shared by AAV2, AAV9, and AAV9 but not AAV5, which could be modified to bioengineering-designed AAAV escape variants as done previously for other AAV serotypes (21, 75, 81).

Another hurdle for the utilization of AAAV-based vectors is that they do not transduce mammalian cell lines such as HEK293 or HeLa cells. For successful transduction, the capsids must bind to the target cell, be internalized, traffic through the endo-lysosomal pathway, escape the endosome, and travel to the nucleus. The cell-binding studies suggest that AAAV is able to attach to mammalian cells potentially by utilizing common surface glycans such as galactose. This indicates that a later stage of the transduction process is affected preventing transgene expression from AAAV vectors in mammalian cells. Recently, a binding motif was identified in the VP1u region allowing the attachment to the entry factor GPR108 (82). While AAV2 is dependent on GPR108, AAV5 does not bind this receptor. However, by swapping the VP1u region between these AAV serotypes, the binding phenotype can be reversed. Furthermore, the Asokan lab presented data at the 2023 Annual American Society of Gene and Cell Therapy meeting showing that mammalian cell binding of AAAV is comparable to other AAV serotypes (83). Furthermore, they showed that transduction can be restored by substituting AAAV’s VP1u region with one of the primate AAVs. Thus, this strategy could be utilized for AAAV by directing the capsid to this mammalian cell receptor.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell culture

Adherent cultures of Human embryonic kidney (HEK293) cells were maintained in Dulbecco modified Eagle medium (DMEM) and supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal calf serum and 1% Antibiotic−Antimycotic. Adherent cultures of CHO cell line variants Pro5 (ATCC CRL-1781) and Lec2 (ATCC CRL-1736) were grown in Minimum Essential Medium Alpha 1 GlutaMax (Gibco) supplemented with 10% Fetal Bovine Serum and 1% Antibiotic-Antimycotic. Cells were incubated in a 37°C stationary incubator with 5% CO2. Adherent cultures of continuous chicken embryo fibroblasts (DF-1) were grown in DMEM and supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal calf serum and 1% Antibiotic-Antimycotic.

Cloning of the AAAV producer plasmid

The AAAV cap gene was amplified using standard PCR. The DNA fragment was inserted into a plasmid containing the AAV2 rep gene using a Gibson Assembly Kit (New England BioLabs) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The correct assembly downstream of the AAV2 rep gene and the minor splice site was confirmed by Sanger sequencing.

Generation and purification of recombinant AAAV particles

Recombinant AAAV vectors with a packaged luciferase gene were produced by triple transfection of HEK293 cells, utilizing pTR-UF3-Luciferase, pHelper (Stratagene), and the above-mentioned AAV2-rep-AAAV-cap plasmid. The transfected cells were harvested 72 h post transfection and washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS; 137 mM NaCl, 2.7 mM KCl, 100 mM Na2HPO4, 2 mM KH2PO4). Subsequently, the cells were pelleted and resuspended in 1× TNTM buffer (25 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 100 mM NaCl, 0.2% Triton X-100, 2 mM MgCl2). The resuspended cells were subjected to three freeze thaw cycles (−80°C to 37°C) and subsequently incubated with 125 U/mL benzonase for 1 h at 37°C before centrifugation at 10,000 × g for 15 min to pellet the cell debris. The harvested AAAV lysate was purified using iodixanol gradient ultracentrifugation as described before (84).

AAAV sample purity and integrity

The purity and integrity of the sample were confirmed by sodium dodecyl-sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) and negative-stain electron microscopy (EM), respectively. For the SDS-PAGE analysis, the sample was incubated with 1× Laemmle Sample Buffer (Bio-Rad) with 10% (vol/vol) β-mercaptoethanol and boiled for 5 min at 100°C. The denatured proteins were applied to a 10% SDS-polyacrylamide gel and run at 80 V. After the run, the gel was washed three times with distilled water (diH2O) and stained with GelCode Blue Protein Safe stain (Invitrogen) for 1 h. The gel was destained with diH2O prior to imaging using a GelDoc EX system (Bio-Rad). For negative stain EM, 5 µL of the sample was incubated on a glow-discharged CF400-CU carbon coated 400 mesh copper grids (Electron Microscopy Sciences) for 2 min and washed in three 15 µL droplets of water. Excess water was blotted with filter paper (Whatman), and the grid was stained with filtered 2% uranyl acetate. Excess stain was blotted, and the grids were imaged using a Tecnai G2 Spirit Transmission Electron Microscope (FEI) operating at 120 kV.

Vitrification and cryo-electron microscopy data collection

Three microliters of the AAAV capsids were applied to glow-discharged C-flat holey carbon-coated grids (Protochips Inc.) and vitrified using the Vitrobot Mark IV (FEI) automatic plunge-freezing system. The sample was incubated on the grids at 4°C and 95% humidity for 3.0 s prior to blotting using filter paper and plunging into a liquid ethane bath for vitrification. The grids were maintained at liquid nitrogen temperatures until data collection. The particle distribution and ice quality of the grids were screened in-house using an FEI Tecnai G2 F20-TWIN microscope (FEI Co.) operated under low-dose conditions (200 kV, ~20e−/Å2). The cryo-EM data collection was performed at the National Institutes of Health Intramural Research Program Cryo-EM Facility (NICE) using the Titan Krios electron microscope. The microscope was operated at 300 kV and data were collected on a Gatan Bioquantum-K2 summit direct electron detector camera at 20 eV energy slit. During data collection, a total dose of 61 e−/Å2 was utilized for 50 movie frames per micrograph. The movie frames were aligned using MotionCor2 with dose weighting (80).

Data processing and 3D particle reconstruction

The cisTEM software package was used for three-dimensional image reconstruction of the AAAV capsid (85). The aligned micrographs were first imported, and their microscope-based contrast transfer function (CTF) was estimated. Suboptimal-quality micrographs were eliminated. Capsids on the remaining micrographs were automatically selected using a particle radius of 125 Å. However, as the subsequent 2D classification provided unsatisfactory results with regards to the separation of empty and full capsids, the two types of capsids were manually selected and the downstream reconstructions were performed independently. Both ab-initio 3D reconstruction and automatic refinement steps were performed utilizing the default settings. The ab-initio 3D reconstruction generated an initial low-resolution map using 10% of the total boxed particles with imposed icosahedral symmetry, while the automatic refinement utilizes the entire data set and the ab-initio generated 3D map. Map sharpening of the high-resolution structure used a pre-cutoff B-factor value of −90 Å2 and variable post-cutoff B-factor values such as 0, 20, and 40 Å2. Using the UCSF-Chimera software, the sharpened density maps were analyzed and the −90 Å2/0 Å2 map was used for further model building and structure refinement. The final resolution of the structures was estimated based on a Fourier shell correlation (FSC) threshold criterion of 0.143 (Table 1).

Model building

The Swiss Model online server was used to generate an in silico model of the AAAV VP monomer based on the amino acid sequence (84). A 60mer of this model was generated using ViperDB (85) and docked into the cryo-EM density maps with Chimera using the “Fit in Map” option (83). The pixel size was adjusted to maximize the correlation coefficient. The EMAN2 subroutine e2proc3d.py was implemented to resize maps based on best fit parameters as determined by correlation coefficients from Chimera (40, 83) and converted to the CCP4 format using MAPMAN (41). The main- and side chains of the atomic AAAV model for both the empty and full capsids were manually refined in Coot using the real-space refinement tool (82). Both models were further automatically refined using PHENIX, which also provided the final refinement statistics (Table 1) (48).

AAV capsid structure comparison

For structural comparison, the AAAV monomer was superposed in Coot onto the previously determined monomers for AAV2 (PDB 1LP3), AAV5 (PDB 3NTT), and AAV9 (3UX1). The secondary structure matching (SSM) subroutine in Coot (48) provided the Cα –Cα distances (in Å) between the compared AAVs VP structures, and was used to calculate the Cα-RMSD and the percentage of aligned amino acids.

Cell binding assay

CHO variant cell lines Pro-5 and Lec-2 were passaged to 50% confluence into 15 cm plates, 24 h prior to conducting the experiment. On the day of the cell binding assay, cells at 90–100% confluence were detached from the plate by addition of 2 mL 0.5 M EDTA to the medium of a 15 cm plate. Cells were transferred into a 50-mL conical tube and centrifuged in a benchtop centrifuge for 5 min at 500 rpm. The supernatant was removed, and the pellet was resuspended in 6 mL of prechilled unsupplemented MEM. The cells were counted under a microscope using a hemocytometer, diluted to 5 × 105 cells/mL, aliquoted to 500 µL fractions, and prechilled for 30 min at 4°C. Each tube of cells was then incubated with purified AAAV, AAV2, AAV5, and AAV9 capsids at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 5 × 105 under constant rotation for 3 to 4 h at 4°C. Following the incubation, the cells were pelleted at 2,000 rpm for 10 min in a benchtop centrifuge and the supernatant was discarded. Unbound VLPs were removed by washing the cells with 300 µL prechilled 1× PBS followed by centrifugation. Pellets were resuspended in 50 µL 1× TNTM, treated with Proteinase K, and were analyzed utilizing qPCR with primers specific to the luciferase gene (Luc-F: AAAAGCACTCTGATTGACAAATAC and Luc-R: CCTTCGCTTCAAAAAATGGAAC) at an annealing temperature of 55°C for 15 s. All experiments were conducted in triplicate.

Neutralization assay

For the AAAV vectors, DF-1 cells were seeded in 96-well plates and allowed to grow overnight to ~50% confluency (2.5 × 104 cells per well) for the following day. The AAAV vectors were diluted into non-supplemented DMEM medium for a MOI of 105 vector genomes per cell. Prior to addition to the cells, the mixtures were combined with one of the 50 different human serum samples (Valley Biomedical, Winchester, VA, USA) in a 1:1 ratio and incubated for 30 min at 37°C. Subsequently, these mixtures were added directly to the cells and incubated at 37°C for 48 h. The luciferase expression of the vectors was analyzed using a luciferase assay system (Promega) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Cells infected with AAAV vectors in the absence of human sera were used as a reference to determine the presence of the neutralizing antibodies. Furthermore, uninfected cells of the same plate were used as a negative control. In the case of AAV2, AAV5, and AAV9 vectors, the same protocol was utilized with the exception of the DF-1 cells for which HEK293 cells were used instead.

Native immuno-dot blot

Native immuno-dot blot experiments were conducted utilizing the Minifold I System (Cytivia). 1010 intact capsid particles for AAAV, AAV2, AAV5, and AAV9 were attached to nitrocellulose membranes via vacuum-assisted application. The membranes with viral capsids were blocked in 1% milk/PBS for 1 h at room temperature (RT) and then incubated with primary antibodies (purified mAb 2–7 and B1) diluted in 1% milk/0.05% Tween-20/PBS and allowed to rock overnight at 4°C. The membranes were washed three times for 5 min each with 0.05% Tween 20/PBS. Then, the membranes were incubated with a horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated secondary antibody (goat pAb to Hu IgG HRP or anti-mouse IgG HRP-linked whole antibody) for 1 h at RT. After a second washing step as described before, the dot blots were developed by incubating the membranes with HRP development solution for 2 min, and chemiluminescence was captured and developed on X-ray film. The presence of a dark circle for each blot indicates recognition of the applied virus by the primary antibody.

Generation of an AAAV capsid-Fab complex structure

Purified AAAV capsids were mixed with Fabs at a ratio of two Fabs per potential VP binding site on the capsid (or approximately 120 Fabs per capsid) for Fab 2–7. The AAAV-Fab complex was incubated on ice for 30 min prior to vitrification. For a low-resolution structure, cryo-EM data were collected on the FEI Tecnai G2 F20-TWIN microscope as mentioned above.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors would like to thank the late Dr. Mavis Agbandje-McKenna for her pioneering research on the structural biology of AAVs. We thank Dr. Grant J. Logan at the University of Sydney for providing the mAb 2-7 generated from patients post-Zolgensma treatment. The authors also thank the University of Florida Interdisciplinary Center for Biotechnology Research (UF-ICBR) electron microscopy for screening the grids and the National Institutes of Health Intramural Research Program Cryo-EM Facility (NICE) for data collection and microscopy.

This research was supported by R01 GM082946 (to R.M.) from the National Institutes of Health (NIH).

Contributor Information

Mario Mietzsch, Email: mario.mietzsch@ufl.edu.

Robert McKenna, Email: rmckenna@ufl.edu.

Colin R. Parrish, Cornell University Baker Institute for Animal Health, Ithaca, New York, USA

DATA AVAILABILITY

The cryo-EM reconstructed density maps and models built for the full and empty AAAV capsid were deposited in the Electron Microscopy Data Bank (EMDB) under the accession numbers EMD-41209 and EMD−41208 and PDB-ID: 8TEY and 8TEX, respectively.

REFERENCES

- 1. Microbiology Society . ICTV virus taxonomy profile: parvoviridae. : https://www.microbiologyresearch.org/content/journal/jgv/10.1099/jgv.0.001212. Accessed 16 February 2023

- 2. Atchison RW, Casto BC, Hammon WM. 1965. Adenovirus-associated defective virus particles. Science 149:754–756. doi: 10.1126/science.149.3685.754 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Agbandje-McKenna M, Kleinschmidt J. 2011. AAV capsid structure and cell interactions, p 47–92. In Snyder RO, Moullier P (ed), Adeno-associated virus: methods and protocols. Humana Press, Totowa, NJ. doi: 10.1007/978-1-61779-370-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Daya S, Berns KI. 2008. Gene therapy using adeno-associated virus vectors. Clin Microbiol Rev 21:583–593. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00008-08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Wang D, Tai PWL, Gao G. 2019. Adeno-associated virus vector as a platform for gene therapy delivery. 5. Nat Rev Drug Discov 18:358–378. doi: 10.1038/s41573-019-0012-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Mietzsch M, Pénzes JJ, Agbandje-McKenna M. 2019. Twenty-five years of structural parvovirology. Viruses 11:362. doi: 10.3390/v11040362 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Girod A, Wobus CE, Zádori Z, Ried M, Leike K, Tijssen P, Kleinschmidt JA, Hallek M. 2002. The VP1 capsid protein of adeno-associated virus type 2 is carrying a phospholipase A2 domain required for virus infectivity. J Gen Virol 83:973–978. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-83-5-973 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Popa-Wagner R, Porwal M, Kann M, Reuss M, Weimer M, Florin L, Kleinschmidt JA. 2012. Impact of VP1-specific protein sequence motifs on adeno-associated virus type 2 intracellular trafficking and nuclear entry. J Virol 86:9163–9174. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00282-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Gao G, Vandenberghe LH, Alvira MR, Lu Y, Calcedo R, Zhou X, Wilson JM. 2004. Clades of adeno-associated viruses are widely disseminated in human tissues. J Virol 78:6381–6388. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.12.6381-6388.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Schmidt M, Katano H, Bossis I, Chiorini JA. 2004. Cloning and characterization of a bovine adeno-associated virus. J Virol 78:6509–6516. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.12.6509-6516.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Arbetman AE, Lochrie M, Zhou S, Wellman J, Scallan C, Doroudchi MM, Randlev B, Patarroyo-White S, Liu T, Smith P, Lehmkuhl H, Hobbs LA, Pierce GF, Colosi P. 2005. Novel caprine adeno-associated virus (AAV) capsid (AAV-Go.1) is closely related to the primate AAV-5 and has unique tropism and neutralization properties. J Virol 79:15238–15245. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.24.15238-15245.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Bello A, Chand A, Aviles J, Soule G, Auricchio A, Kobinger GP. 2014. Novel adeno-associated viruses derived from pig tissues transduce most major organs in mice. Sci Rep 4:6644. doi: 10.1038/srep06644 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Li L, Shan T, Wang C, Côté C, Kolman J, Onions D, Gulland FMD, Delwart E. 2011. The fecal viral Flora of California sea lions. J Virol 85:9909–9917. doi: 10.1128/JVI.05026-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Bodewes R, van der Giessen J, Haagmans BL, Osterhaus A, Smits SL. 2013. Identification of multiple novel viruses, including a parvovirus and a hepevirus, in feces of red foxes. J Virol 87:7758–7764. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00568-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Li Y, Li J, Liu Y, Shi Z, Liu H, Wei Y, Yang L. 2019. Bat adeno-associated viruses as gene therapy vectors with the potential to evade human neutralizing antibodies. Gene Ther 26:264–276. doi: 10.1038/s41434-019-0081-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Lochrie MA, Tatsuno GP, Arbetman AE, Jones K, Pater C, Smith PH, McDonnell JW, Zhou S-Z, Kachi S, Kachi M, Campochiaro PA, Pierce GF, Colosi P. 2006. Adeno-associated virus (AAV) capsid genes isolated from rat and mouse liver genomic DNA define two new AAV species distantly related to AAV-5. Virology 353:68–82. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2006.05.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Bossis I, Chiorini JA. 2003. Cloning of an avian adeno-associated virus (AAAV) and generation of recombinant AAAV particles. J Virol 77:6799–6810. doi: 10.1128/jvi.77.12.6799-6810.2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Bantel-Schaal U, zur Hausen H. 1984. Characterization of the DNA of a defective human parvovirus isolated from a genital site. Virology 134:52–63. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(84)90271-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Farkas SL, Zádori Z, Benkő M, Essbauer S, Harrach B, Tijssen P. 2004. A parvovirus isolated from royal python (Python regius) is a member of the genus Dependovirus. J Gen Virol 85:555–561. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.19616-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Pénzes JJ, Pham HT, Benkö M, Tijssen P. 2015. Novel parvoviruses in reptiles and genome sequence of a lizard parvovirus shed light on Dependoparvovirus genus evolution. J Gen Virol 96:2769–2779. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.000215 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Mietzsch M, Yu JC, Hsi J, Chipman P, Broecker F, Fuming Z, Linhardt RJ, Seeberger PH, Heilbronn R, McKenna R, Agbandje-McKenna M. 2021. Structural study of AAVrh.10 receptor and antibody interactions. J Virol 95:e0124921. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01249-21 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Mietzsch M, Barnes C, Hull JA, Chipman P, Xie J, Bhattacharya N, Sousa D, McKenna R, Gao G, Agbandje-McKenna M. 2020. Comparative analysis of the capsid structures of AAVrh.10, AAVrh.39, and AAV8. J Virol 94:e01769-19. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01769-19 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Guenther CM, Brun MJ, Bennett AD, Ho ML, Chen W, Zhu B, Lam M, Yamagami M, Kwon S, Bhattacharya N, Sousa D, Evans AC, Voss J, Sevick-Muraca EM, Agbandje-McKenna M, Suh J. 2019. Protease-activatable adeno-associated virus vector for gene delivery to damaged heart tissue. Mol Ther 27:611–622. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2019.01.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Bennett A, Keravala A, Makal V, Kurian J, Belbellaa B, Aeran R, Tseng Y-S, Sousa D, Spear J, Gasmi M, Agbandje-McKenna M. 2020. Structure comparison of the chimeric AAV2.7m8 vector with parental AAV2. J Struct Biol 209:107433. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2019.107433 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Kaelber JT, Yost SA, Webber KA, Firlar E, Liu Y, Danos O, Mercer AC. 2020. Structure of the AAVhu.37 capsid by cryoelectron microscopy. Acta Crystallogr F Struct Biol Commun 76:58–64. doi: 10.1107/S2053230X20000308 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Mietzsch M, Li Y, Kurian J, Smith JK, Chipman P, McKenna R, Yang L, Agbandje-McKenna M. 2020. Structural characterization of a bat adeno-associated virus capsid. J Struct Biol 211:107547. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2020.107547 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Mietzsch M, Jose A, Chipman P, Bhattacharya N, Daneshparvar N, McKenna R, Agbandje-McKenna M. 2021. Completion of the AAV structural atlas: serotype capsid structures reveals clade-specific features. Viruses 13:101. doi: 10.3390/v13010101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Govindasamy L, Padron E, McKenna R, Muzyczka N, Kaludov N, Chiorini JA, Agbandje-McKenna M. 2006. Structurally mapping the diverse phenotype of adeno-associated virus serotype 4. J Virol 80:11556–11570. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01536-06 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Venkatakrishnan B, Yarbrough J, Domsic J, Bennett A, Bothner B, Kozyreva OG, Samulski RJ, Muzyczka N, McKenna R, Agbandje-McKenna M. 2013. Structure and dynamics of adeno-associated virus serotype 1 VP1-unique N-terminal domain and its role in capsid trafficking. J Virol 87:4974–4984. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02524-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Büning H. 2013. Gene therapy enters the pharma market: the short story of a long journey. EMBO Mol Med 5:1–3. doi: 10.1002/emmm.201202291 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Patel U, Boucher M, de L, Visintini S. 2016. Voretigene neparvovec: an emerging gene therapy for the treatment of inherited blindness, In CADTH issues in emerging health technologies. Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health, Ottawa (ON). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Hoy SM. 2019. Onasemnogene abeparvovec: first global approval. Drugs 79:1255–1262. doi: 10.1007/s40265-019-01162-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Keam SJ. 2022. Eladocagene exuparvovec: first approval. Drugs 82:1427–1432. doi: 10.1007/s40265-022-01775-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Blair HA. 2022. Valoctocogene roxaparvovec: first approval. Drugs 82:1505–1510. doi: 10.1007/s40265-022-01788-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Heo Y-A. 2023. Etranacogene dezaparvovec: first approval. Drugs 83:347–352. doi: 10.1007/s40265-023-01845-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Mullard A. 2023. FDA approves first gene therapy for Duchenne muscular dystrophy, despite internal objections. Nat Rev Drug Discov. doi: 10.1038/d41573-023-00103-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Boutin S, Monteilhet V, Veron P, Leborgne C, Benveniste O, Montus MF, Masurier C. 2010. Prevalence of serum IgG and neutralizing factors against adeno-associated virus (AAV) types 1, 2, 5, 6, 8, and 9 in the healthy population: implications for gene therapy using AAV vectors. Hum Gene The 21:704–712. doi: 10.1089/hum.2009.182 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Yates VJ, Dawson GJ, Pronovost AD. 1981. Serologic evidence of avian adeno-associated virus infection in an unselected human population and among poultry workers. Am J Epidemiol 113:542–545. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a113130 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Yates VJ, el-Mishad AM, McCormick KJ, Trentin JJ. 1973. Isolation and characterization of an avian adenovirus-associated virus. Infect Immun 7:973–980. doi: 10.1128/iai.7.6.973-980.1973 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Dereeper A, Guignon V, Blanc G, Audic S, Buffet S, Chevenet F, Dufayard J-F, Guindon S, Lefort V, Lescot M, Claverie J-M, Gascuel O. 2008. Phylogeny.fr: robust phylogenetic analysis for the non-specialist. Nucleic Acids Res 36:W465–W469. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn180 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Mietzsch M, Grasse S, Zurawski C, Weger S, Bennett A, Agbandje-McKenna M, Muzyczka N, Zolotukhin S, Heilbronn R. 2014. OneBac: platform for scalable and high-titer production of adeno-associated virus serotype 1-12 vectors for gene therapy. Hum Gene Ther 25:212–222. doi: 10.1089/hum.2013.184 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Gray SJ, Choi VW, Asokan A, Haberman RA, McCown TJ, Samulski RJ. 2011. Production of recombinant adeno-associated viral vectors and use in in vitro and in vivo administration. Curr Protoc Neurosci Chapter 4:Unit. doi: 10.1002/0471142301.ns0417s57 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Mietzsch M, Smith JK, Yu JC, Banala V, Emmanuel SN, Jose A, Chipman P, Bhattacharya N, McKenna R, Agbandje-McKenna M. 2020. Characterization of AAV-specific affinity ligands: consequences for vector purification and development strategies. Mol Ther Methods Clin Dev 19:362–373. doi: 10.1016/j.omtm.2020.10.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Johnson FB, Ozer HL, Hoggan MD. 1971. Structural proteins of adenovirus-associated virus type 3. J Virol 8:860–863. doi: 10.1128/JVI.8.6.860-863.1971 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Buller RM, Rose JA. 1978. Characterization of adenovirus-associated virus-induced polypeptides in KB cells. J Virol 25:331–338. doi: 10.1128/JVI.25.1.331-338.1978 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Snijder J, van de Waterbeemd M, Damoc E, Denisov E, Grinfeld D, Bennett A, Agbandje-McKenna M, Makarov A, Heck AJR. 2014. Defining the stoichiometry and cargo load of viral and bacterial nanoparticles by Orbitrap mass spectrometry. J Am Chem Soc 136:7295–7299. doi: 10.1021/ja502616y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Chiorini JA, Kim F, Yang L, Kotin RM. 1999. Cloning and characterization of adeno-associated virus type 5. J Virol 73:1309–1319. doi: 10.1128/JVI.73.2.1309-1319.1999 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Pettersen EF, Goddard TD, Huang CC, Couch GS, Greenblatt DM, Meng EC, Ferrin TE. 2004. UCSF chimera--a visualization system for exploratory research and analysis. J Comput Chem 25:1605–1612. doi: 10.1002/jcc.20084 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Mietzsch M, Hull JA, Makal VE, Jimenez Ybargollin A, Yu JC, McKissock K, Bennett A, Penzes J, Lins-Austin B, Yu Q, Chipman P, Bhattacharya N, Sousa D, Strugatsky D, Tijssen P, McKenna R, Agbandje-McKenna M. 2022. Characterization of the serpentine adeno-associated virus (SAAV) capsid structure: receptor interactions and antigenicity. J Virol 96:e0033522. doi: 10.1128/jvi.00335-22 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Drouin LM, Lins B, Janssen M, Bennett A, Chipman P, McKenna R, Chen W, Muzyczka N, Cardone G, Baker TS, Agbandje-McKenna M. 2016. Cryo-electron microscopy reconstruction and stability studies of the wild type and the R432A variant of adeno-associated virus type 2 reveal that capsid structural stability is a major factor in genome packaging. J Virol 90:8542–8551. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00575-16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Tan YZ, Aiyer S, Mietzsch M, Hull JA, McKenna R, Grieger J, Samulski RJ, Baker TS, Agbandje-McKenna M, Lyumkis D. 2018. Sub-2 Å Ewald curvature corrected structure of an AAV2 capsid variant. Nat Commun 9:3628. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-06076-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Bennett A, Gargas J, Kansol A, Lewis J, Hsi J, Hull J, Mietzsch M, Tartaglia L, Muzyczka N, Bhattacharya N, Chipman P, Agbandje-McKenna M. 2023. Structural and biophysical analysis of Aav2 Capsid assembly variants. J Virol 97:e0177222. doi: 10.1128/jvi.01772-22 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Lochrie MA, Tatsuno GP, Christie B, McDonnell JW, Zhou S, Surosky R, Pierce GF, Colosi P. 2006. Mutations on the external surfaces of adeno-associated virus type 2 capsids that affect transduction and neutralization. J Virol 80:821–834. doi: 10.1128/JVI.80.2.821-834.2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Aydemir F, Salganik M, Resztak J, Singh J, Bennett A, Agbandje-McKenna M, Muzyczka N. 2016. Mutants at the 2-fold interface of adeno-associated virus type 2 (AAV2) structural proteins suggest a role in viral transcription for AAV capsids. J Virol 90:7196–7204. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00493-16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Emmanuel SN, Mietzsch M, Tseng YS, Smith JK, Agbandje-McKenna M. 2021. Parvovirus capsid-antibody complex structures reveal conservation of antigenic epitopes across the family. Viral Immunol 34:3–17. doi: 10.1089/vim.2020.0022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Logan GJ, Mietzsch M, Khandekar N, D’Silva A, Anderson D, Mandwie M, Hsi J, Nelson AR, Chipman P, Jackson J, Schofield P, Christ D, Goodnow CC, Reed JH, Farrar MA, McKenna R, Alexander IE. 2023. Structural and functional characterization of capsid binding by anti-AAV9 monoclonal antibodies from infants after SMA gene therapy. Mol Ther 31:1979–1993. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2023.03.032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Nam H-J, Lane MD, Padron E, Gurda B, McKenna R, Kohlbrenner E, Aslanidi G, Byrne B, Muzyczka N, Zolotukhin S, Agbandje-McKenna M. 2007. Structure of adeno-associated virus serotype 8, a gene therapy vector. J Virol 81:12260–12271. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01304-07 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Lerch TF, Xie Q, Chapman MS. 2010. The structure of adeno-associated virus serotype 3B (AAV-3B): insights into receptor binding and immune evasion. Virology 403:26–36. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2010.03.027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Halder S, Van Vliet K, Smith JK, Duong TTP, McKenna R, Wilson JM, Agbandje-McKenna M. 2015. Structure of neurotropic adeno-associated virus AAVrh.8. J Struct Biol 192:21–36. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2015.08.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Schrödinger, LLC. 2015. The PyMOL Molecular Graphics System Version 1.8.

- 61. Kaludov N, Brown KE, Walters RW, Zabner J, Chiorini JA. 2001. Adeno-associated virus serotype 4 (AAV4) and AAV5 both require sialic acid binding for hemagglutination and efficient transduction but differ in sialic acid linkage specificity. J Virol 75:6884–6893. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.15.6884-6893.2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Berry GE, Asokan A. 2016. Cellular transduction mechanisms of adeno-associated viral vectors. Curr Opin Virol 21:54–60. doi: 10.1016/j.coviro.2016.08.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Lim SF, Lee MM, Zhang P, Song Z. 2008. The Golgi CMP-sialic acid transporter: a new CHO mutant provides functional insights. Glycobiology 18:851–860. doi: 10.1093/glycob/cwn080 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Summerford C, Samulski RJ. 1998. Membrane-associated heparan sulfate proteoglycan is a receptor for adeno-associated virus type 2 virions. J Virol 72:1438–1445. doi: 10.1128/JVI.72.2.1438-1445.1998 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Bell CL, Gurda BL, Van Vliet K, Agbandje-McKenna M, Wilson JM. 2012. Identification of the galactose binding domain of the adeno-associated virus serotype 9 capsid. J Virol 86:7326–7333. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00448-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Shen S, Bryant KD, Brown SM, Randell SH, Asokan A. 2011. Terminal N-linked galactose is the primary receptor for adeno-associated virus 9. J Biol Chem 286:13532–13540. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.210922 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Huang L-Y, Patel A, Ng R, Miller EB, Halder S, McKenna R, Asokan A, Agbandje-McKenna M. 2016. Characterization of the adeno-associated virus 1 and 6 sialic acid binding site. J Virol 90:5219–5230. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00161-16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Porter JM, Oswald MS, Sharma A, Emmanuel S, Kansol A, Bennett A, McKenna R, Smith JG. 2023. A single surface-exposed amino acid determines differential neutralization of AAV1 and AAV6 by human alpha-defensins. J Virol 97:e0006023. doi: 10.1128/jvi.00060-23 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Fitzpatrick Z, Leborgne C, Barbon E, Masat E, Ronzitti G, van Wittenberghe L, Vignaud A, Collaud F, Charles S, Simon Sola M, Jouen F, Boyer O, Mingozzi F. 2018. Influence of pre-existing anti-capsid neutralizing and binding antibodies on AAV vector transduction. Mol Ther Methods Clin Dev 9:119–129. doi: 10.1016/j.omtm.2018.02.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Calcedo R, Vandenberghe LH, Gao G, Lin J, Wilson JM. 2009. Worldwide epidemiology of neutralizing antibodies to adeno-associated viruses. J Infect Dis 199:381–390. doi: 10.1086/595830 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Mori S, Takeuchi T, Kanda T. 2008. Antibody-dependent enhancement of adeno-associated virus infection of human monocytic cell lines. Virology 375:141–147. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2008.01.033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Xu M, Perdomo MF, Mattola S, Pyöriä L, Toppinen M, Qiu J, Vihinen-Ranta M, Hedman K, Nokso-Koivisto J, Aaltonen L-M, Söderlund-Venermo M, Tattersall P, Miller MS. 2021. Persistence of human bocavirus 1 in tonsillar germinal centers and antibody-dependent enhancement of infection. mBio 12:e03132-20. doi: 10.1128/mBio.03132-20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. von Kietzell K, Pozzuto T, Heilbronn R, Grössl T, Fechner H, Weger S, Imperiale MJ. 2014. Antibody-mediated enhancement of parvovirus B19 uptake into endothelial cells mediated by a receptor for complement factor C1q. J Virol 88:8102–8115. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00649-14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Bloom ME, Best SM, Hayes SF, Wells RD, Wolfinbarger JB, McKenna R, Agbandje-McKenna M. 2001. Identification of aleutian mink disease parvovirus capsid sequences mediating antibody-dependent enhancement of infection, virus neutralization, and immune complex formation. J Virol 75:11116–11127. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.22.11116-11127.2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Emmanuel SN, Smith JK, Hsi J, Tseng Y-S, Kaplan M, Mietzsch M, Chipman P, Asokan A, McKenna R, Agbandje-McKenna M. 2022. Structurally mapping antigenic epitopes of adeno-associated virus 9: development of antibody escape variants. J Virol 96:e0125121. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01251-21 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Gao G-P, Alvira MR, Wang L, Calcedo R, Johnston J, Wilson JM. 2002. Novel adeno-associated viruses from rhesus monkeys as vectors for human gene therapy. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 99:11854–11859. doi: 10.1073/pnas.182412299 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Mori S, Wang L, Takeuchi T, Kanda T. 2004. Two novel adeno-associated viruses from cynomolgus monkey: pseudotyping characterization of capsid protein. Virology 330:375–383. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2004.10.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Wang M, Crosby A, Hastie E, Samulski JJ, McPhee S, Joshua G, Samulski RJ, Li C. 2015. Prediction of adeno-associated virus neutralizing antibody activity for clinical application. Gene Ther 22:984–992. doi: 10.1038/gt.2015.69 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Kruzik A, Fetahagic D, Hartlieb B, Dorn S, Koppensteiner H, Horling FM, Scheiflinger F, Reipert BM, de la Rosa M. 2019. Prevalence of anti-adeno-associated virus immune responses in international cohorts of healthy donors. Mol Ther Methods Clin Dev 14:126–133. doi: 10.1016/j.omtm.2019.05.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Verdera HC, Kuranda K, Mingozzi F. 2020. AAV vector immunogenicity in humans: a long journey to successful gene transfer. Mol Ther 28:723–746. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2019.12.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Jose A, Mietzsch M, Smith JK, Kurian J, Chipman P, McKenna R, Chiorini J, Agbandje-McKenna M. 2019. High-resolution structural characterization of a new adeno-associated virus serotype 5 antibody epitope toward engineering antibody-resistant recombinant gene delivery vectors. J Virol 93:e01394-18. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01394-18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Dudek AM, Zabaleta N, Zinn E, Pillay S, Zengel J, Porter C, Franceschini JS, Estelien R, Carette JE, Zhou GL, Vandenberghe LH. 2020. GPR108 is a highly conserved AAV entry factor. Mol Ther 28:367–381. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2019.11.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Loeb E, Havlik LP, Asokan A. 2022. 2022 ASGCT annual meeting abstracts. Mol Ther 30:1–592. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2022.04.017 34921769 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Zolotukhin S, Byrne BJ, Mason E, Zolotukhin I, Potter M, Chesnut K, Summerford C, Samulski RJ, Muzyczka N. 1999. Recombinant adeno-associated virus purification using novel methods improves infectious titer and yield. Gene Ther 6:973–985. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3300938 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Grant T, Rohou A, Grigorieff N. 2018. CisTEM, user-friendly software for single-particle image processing. eLife 7:e35383. doi: 10.7554/eLife.35383 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The cryo-EM reconstructed density maps and models built for the full and empty AAAV capsid were deposited in the Electron Microscopy Data Bank (EMDB) under the accession numbers EMD-41209 and EMD−41208 and PDB-ID: 8TEY and 8TEX, respectively.