Abstract

Bowel urgency (BU), the sudden or immediate need for a bowel movement, is one of the most common and disruptive symptoms experienced by patients with ulcerative colitis (UC). Distinct from the separate symptom of increased stool frequency, BU has a substantial negative impact on quality of life and psychosocial functioning. Among patients with UC, BU is one of the top reasons for treatment dissatisfaction and one of the symptoms patients most want improved. Patients may not discuss BU often due to embarrassment, and healthcare providers may not address the symptom adequately due to the lack of awareness of validated tools and/or knowledge of the importance of assessing BU. The mechanism of BU in UC is multifactorial and includes inflammatory changes in the rectum that may be linked to hypersensitivity and reduced compliance of the rectum. Responsive and reliable patient-reported outcome measures of BU are needed to provide evidence of treatment benefits in clinical trials and facilitate communication in clinical practice. This review discusses the pathophysiology and clinical importance of BU in UC and its impact on the quality of life and psychosocial functioning. Patient-reported outcome measures developed to assess the severity of BU in UC are discussed alongside overviews of treatment options and clinical guidelines. Implications for the future management of UC from the perspective of BU are also explored.

INTRODUCTION

Ulcerative colitis (UC) commonly presents with symptoms including rectal bleeding, stool frequency, and bowel urgency (BU) (1). BU, the sudden or immediate need for a bowel movement, is distinct from increased stool frequency (Table 1) (2,3). It is one of the most bothersome symptoms experienced by patients with UC, with substantial negative impacts on quality of life (QoL) and psychosocial functioning (3,6–17).

Table 1.

Definitions of bowel urgency and related concepts

BU is one of the leading reasons patients with UC are dissatisfied with their treatment and one of the symptoms patients most want improved (9,18,19). However, BU is often not discussed by patients due to embarrassment, and it may not be addressed adequately by healthcare providers (HCPs) due to a lack of awareness of validated tools and/or knowledge of the importance of assessing BU (8,9,18,20).

This review aims to interpret the most recent research on BU in UC, with a focus on its clinical importance and impact on QoL and psychosocial functioning. It presents the latest evidence on the pathophysiology of BU in UC, tools to measure BU, and viewpoints on the future management of UC from the perspective of addressing BU.

MECHANISMS DRIVING BU

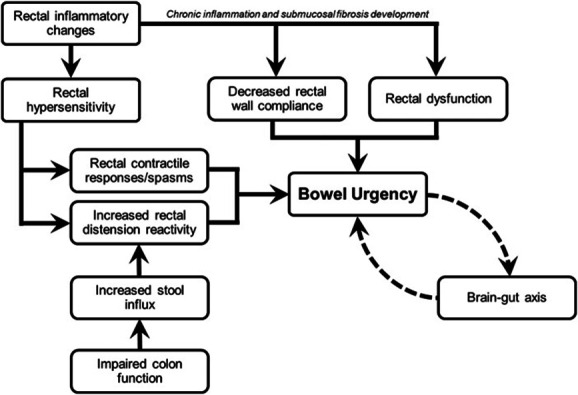

The underlying mechanisms of BU in patients with UC are multifactorial and may vary within and between patients (21–30). During evaluation, it is important to discriminate the inflammatory component (the target of most UC treatments) from other mechanisms that are also caused by the chronic process of UC. Figure 1 summarizes the mechanisms of BU in UC.

Figure 1.

Multifactorial mechanisms of bowel urgency in ulcerative colitis.

Many symptoms of UC, including BU, are believed to be driven primarily by active inflammation (21–23).Motility can seem altered with increased sigmoid-rectum transit because of an increase of propulsive pressure waves in this colonic segment (21). In active UC, stool weight is increased, which is probably related to exudation from the inflamed epithelium, increased secretion of mucus, and reduced capacity to absorb fluid and electrolytes (31). In addition, altered function of the rectal wall results in diminished distensibility, which reduces rectal capacity and leads to the arrival of fecal matter in an unaccommodating rectum. This generates increased pressure from smaller volumes and a subsequent sense of BU (27).

Chronic inflammation may also affect BU through decreased rectal wall compliance and rectal dysfunction (11,26). Chronic disease can lead to increased thickness of the muscularis mucosae and increased fibrosis in the submucosa (24). Notably, colonic dysmotility leading to symptoms such as BU can occur in the absence of macroscopic or microscopic inflammation (24). In a prospective study, patients with active or quiescent UC were found to have diminished rectal compliance compared with healthy controls (26). This suggests UC is a progressive disease and that decreased rectal compliance may be preventable or reversible with sufficient disease control (26).

Another potential mechanism for BU is anal sphincter “fatigability,” which is increased in patients with BU, but notably, such sphincter fatigability is unrelated to local inflammation (32). Negative emotions such as anxiety or stress may also contribute to BU by increasing visceral sensitivity by the brain-gut axis (33), which represents a complex bidirectional system comprising multiple interconnections between neuroendocrine pathways, the autonomous nervous system, and the gastrointestinal tract (34).

Patients with active UC also experience sensory changes and have increased smooth muscle tone, which may result in hypersensitivity and increased rectal contractile responses due to sensitization of intramural receptors in response to inflammatory changes (21–23,35). However, BU does not always equate to active UC. Anorectal dysfunction, particularly rectal hypersensitivity, can persist in quiescent UC. Hypersensitivity contributes to BU as urgency can follow the sensation of rectal filling (25). Hypersensitivity is also associated with functional bowel disorders, which can occur alongside inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) (36).

BU can occur in both active and quiescent UC (17). Overlooking the possibility of anorectal dysfunction (e.g., anal sphincter “fatigability” and/or hypersensitivity), a contributing factor to BU in quiescent UC, can lead to increased healthcare utilization, including invasive testing and unnecessary escalation of therapy, and patient dissatisfaction due to refractory symptoms (36).

CLINICAL SIGNIFICANCE OF BU

Most patients with UC, including those receiving treatment, experience BU (37). In cross-sectional and observational studies, more than 80% of patients with UC report BU (2,8,37–39). Furthermore, up to 50% of patients with UC report experiencing BU at least once daily (8,40,41). One of the most compelling consequences of BU is the need for many patients to wear diapers, pads, or other protection (42,43). The CONFIDE study reported 45% and 37% of United States and European patients, respectively, with moderate-to-severe UC wore diapers, pads, or other protection at least once weekly in the past 3 months for fear of a BU-related accident (44). The unpredictable and urgent nature of defecation, combined with uncertainty over access to facilities, increases the fear of having bowel accidents in public and may be as limiting as the actual incontinence (14). Current management of UC does not adequately address the issue of BU.

Evolving evidence suggests BU correlates with disease activity, QoL, psychological impact, clinical outcomes, and biomarkers in UC (3,43,45,46). Patients with UC or Crohn disease and mild-to-severe BU are almost 6-fold more likely to have active disease as measured by the Inflammatory Bowel Disease Symptom Inventory (relative risk, 5.9; 95% confidence interval [CI], 4.0–8.6) than those without BU (43). A significantly greater proportion of patients with UC who achieved clinically meaningful improvement or remission in BU (≥3-point decrease or score ≤1 in Urgency Numeric Rating Scale [NRS], respectively) also achieved symptomatic, clinical, corticosteroid-free, and endoscopic remission as well as clinical response and normalization of fecal calprotectin and C-reactive protein levels and improved QoL measures than those who did not achieve these BU endpoints (47).

BU and urge incontinence are also associated with increased risk of colectomy (hurry and immediately vs no hurry: odds ratio [OR], 1.42 and 1.90, respectively; 95% CI, 1.15–1.75 and 1.45–2.50, respectively), corticosteroid use (hurry and immediately vs no hurry: OR, 1.28 and 1.58, respectively; 95% CI, 1.11–1.47 and 1.27–1.95, respectively), and hospitalization (hurry and immediately vs no hurry: OR, 1.57 and 2.64, respectively; 95% CI, 1.37–1.81 and 2.21–3.15, respectively) (3). Nevertheless, assessment of BU has not been recommended as an endpoint in UC clinical trials or real-world studies and is often overlooked during the drug registration process (37,48). Furthermore, BU is not included in most UC disease activity indices, despite being the symptom with the greatest impact on patients' lives (49–52). However, BU is now recommended as a key symptom in the diagnosis of UC and a core outcome in UC clinical trials (48,49,53–55). A multidisciplinary international consensus recommended patient-reported outcomes (PROs) should include rectal bleeding, stool frequency, and BU (56). BU is recognized in the evaluation of disease severity in clinical practice (49), and control of BU is included in both clinical guidelines and definitions of UC (48,49,53–55). A combination of BU, stool frequency, and stool blood may also serve as a surrogate marker for UC disease activity (57).

BU is one of the most bothersome symptoms experienced by patients with UC (6,15,37,50,52,58). Patients report BU to be a more important symptom than abdominal pain, blood in stools, or stool frequency (37,51,59), and it is significantly associated with patients with UC not feeling well (45).

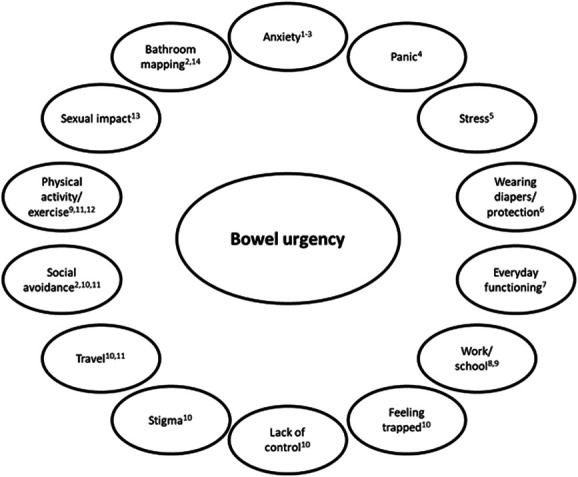

Several studies highlight the importance of BU to patients with UC (Table 2 and Figure 2). In a survey of Japanese patients with UC, BU and bowel incontinence were associated with higher stool frequency and rectal bleeding scores (9), but BU also occurred in patients without frequent stools or rectal bleeding (9). When asked about the symptom they would most like improved, BU was the most common answer (9). In another survey of outpatients with IBD in the United States, the most common symptoms reported were abdominal pain (10%) and BU (7%) (67). Similarly in Europe, Spanish patients with UC reported they most wanted to control rectal bleeding (27%) and BU (16%) (50). An international study of patients across 10 countries identified improvement in BU as one the most frequent reasons for treatment satisfaction (18). In a subgroup analysis in Australian patients, only 36% reported they were satisfied that their prescription medication improved BU (60).

Table 2.

Summary of key survey-based studies of BU in patients with UC

Figure 2.

Impact of bowel urgency on patient quality-of-life and psychosocial functioning. Sources: Waljee et al (61); Dubinsky et al (6); Hibi et al (9); Dibley and Norton (14); Larsson et al (13); Schreiber et al (62); Petryszyn and Paradowski (8); Miller et al (63); Dubinsky et al (64); Dibley et al (12); Sninsky et al (3); Tew et al (11); Travis et al (65); and Kemp et al (66).

BU negatively affects patients' QoL and psychosocial functioning (11,68,69). In a Danish study, health-related QoL was prominently associated with BU and blood in stool (70). In North America and Europe, patients reported that BU and the unpredictable need to use the toilet had a high impact on QoL (49). A meta-analysis of studies in patients with quiescent IBD found that dyssynergic defecation and its associated symptoms, including BU, may persist in up to 97% of patients without ileal pouch-anal anastomosis and up to 75% in patients with ileal pouch-anal anastomosis. BU without constipation in quiescent disease may indicate dyssynergic defecation, which can also negatively impact QoL and contribute to treatment dissatisfaction (36,71).

The emotional and psychological impact of BU may manifest as increased anxiety or panic (6,9,13,14,61). In a study including patients with IBD-related fecal incontinence, feelings of panic, distress, and embarrassment contributed to the impact of BU on their lives (14). Swedish patients reported BU as an important stressor and attempted various coping strategies, such as distraction and sharing feelings about the disease with others (13). BU also significantly increases the risks of depression (OR, 3.03; 95% CI, 1.82–5.15), anxiety (OR, 2.15; 95% CI, 1.40–3.30), and fatigue (OR, 1.95; 95% CI, 1.27–3.01) (3).

Fecal incontinence, the involuntary loss of liquid or solid stool, is a concept related to BU (Table 1). A study of patients with UC found those who reported refractory fecal incontinence while in remission had significantly greater median Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale depression and anxiety scores and worse QoL scores compared with those in remission without fecal incontinence (72).

Patients with BU have reported feeling trapped, dirty, and lacking in control (14). In addition, up to 70% of patients with UC have worse daily functional capacity due to BU or tenesmus (8). Furthermore, physical activity may be limited by BU in almost half of patients with IBD (11), and the top reasons reported for declining participation in social events, work/school, and sports/physical exercise are BU and fear of fecal urge incontinence (42). BU can also limit capacity to travel (14) and increase social impairment and social avoidance (3,6,12,20). Among patients with moderate-to-severe UC in the United States and Europe, the most common UC-related reasons for declining participation in social events were BU (43% and 30%, respectively) and fear of urge incontinence (40% and 32%, respectively) (73,74). BU can also affect sexual health, result in stigma, and force patients to map bathrooms and carry clean-up kits (3,6,12,14,16,66,68).

PATIENT-HCP COMMUNICATION GAPS

The management of chronic diseases such as UC relies on strong patient-HCP relationships facilitated by good communication. Addressing BU is a challenge as patients may not raise the topic (8,9,17,49); only 30% of patients from the United States and 43% from Europe in the CONFIDE study feeling comfortable discussing BU with their HCP, commonly because of embarrassment (42,73). In a Japanese study, patients with UC were embarrassed about discussing symptoms such as BU with a HCP (9). By contrast, the most common reason reported by HCPs for not discussing BU was the expectation that patients would bring it up (20).

This communication gap between patients and HCPs may lead to HCPs underestimating the effect of UC on patients and/or failing to recognize concerns that are important to patients (15,20,49). HCPs reported that over 50% of patients with UC believed BU and spending a significant amount of time in the bathroom were part of living with UC they should accept (18). In the CONFIDE study, 24% of patients, but only 4% of HCPs, ranked BU as having the greatest impact on patients' lives (75). Furthermore, HCPs did not report BU as among the top 3 symptoms affecting treatment decisions for patients with UC (75). HCPs must make an active effort to draw out patients' individual concerns, including symptoms they may not initially feel able to discuss openly. BU should be included in the assessment of IBD on patients' everyday lives (41).

Obtaining patient histories serves as an opportunity to discuss BU. HCPs should directly and sensitively ask about BU and its impacts on daily life activities (17). In patients with quiescent UC, HCPs can elucidate the impact of refractory symptoms in the absence of active inflammation. Pelvic floor dyssynergia has a complex presentation in quiescent UC: Instead of the hallmark symptoms of constipation and difficulties with defecation, it can also be linked with increased stool frequency, fecal incontinence, and BU (71).

When taking a patient's clinical history, asking for information on the individual's obstetric health and any past anal sphincter surgeries can assist in providing a more thorough view of factors that can contribute to BU beyond active inflammation. Knowing the distribution of any previous inflammatory disease, particularly distal colitis or proctitis with inflammation limited to the rectum, can help in determining if there is any underlying rectal hypersensitivity, a contributing factor to BU (36).

Abnormal gastrointestinal motility is a factor affecting and complicating the presentation of IBD. Functional anorectal disorders are the most prevalent functional bowel disorders in patients with IBD; patients can experience refractory symptoms even in the setting of quiescent IBD (76). Patients being evaluated for active or quiescent UC should then also be screened for coexisting functional bowel disorders, such as irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), and any symptoms suggesting overflow diarrhea and/or fecal impaction. HCPs should ask about the patient's experiences of incomplete emptying, strain when passing stools, and stool consistency. Symptoms of any functional bowel disorder should be described in depth. In some patients with IBS, BU may not result in a bowel movement and can be misinterpreted as diarrhea (36). If present, pelvic floor dyssynergia can later be assessed with anorectal manometry and a balloon expulsion test or defecography (36,71,77).

ASSESSMENTS OF BU

Patient-reported outcomes

Although BU is considered important by patients, it is not part of the outcome measures most commonly used in clinical trials, including the Mayo score for UC and PRO-2 (46,78). However, it is a key component of the Simple Clinical Colitis Activity Index (79,80).

Updated approaches to UC remission include control of BU in addition to normal stool frequency and no rectal bleeding (48,53–55) (updates to clinical guidelines highlighting the importance of BU are discussed in the Clinical guidelines for BU section) (48,53–55). Goals for PROs should include resolution of rectal bleeding and BU, normalization of bowel habits, and improvement in general well-being (68). IBD consultations should include measures of BU, stool frequency, and body weight in addition to blood tests (81). PROs are becoming increasingly prominent in the assessment of patients with UC, and easy-to-use tools are warranted (52,82,83).

The Food and Drug Administration recommends that PROs should be used in clinical trials evaluating UC treatments (84). Patients with UC prefer a BU scale that distinguishes levels of severity instead of a binary “yes/no” response (85). Consequently, several PRO tools have been developed, including the 29-item Symptoms and Impacts Questionnaire for Ulcerative Colitis, the Ulcerative Colitis Patient-Reported Outcomes Signs and Symptoms measure, the Patient-Reported Outcome-Ulcerative Colitis diary, and the Urgency NRS (6,39,58,86). Table 3 provides an overview of PROs developed in accordance with Food and Drug Administration guidance that include BU.

Table 3.

Patient-reported outcome measures of BU developed in accordance with the Food and Drug Administration guidance

NRSs for BU

Assessments of the presence and severity of BU are best conducted at regular intervals to monitor treatment response. NRSs without units have several benefits for measuring BU (6) and have been used to assess abdominal pain in IBS (87). Like pain and analgesia, BU is subjective and perceptions of the experience of BU can vary among patients (2). NRSs capture overall ratings of patients' perceptions of subjective symptoms (88) and are, therefore, well-suited to assess BU severity in UC.

The Urgency NRS is a single-item PRO measure that includes a 0–10 scale, with 0 representing no BU and 10 representing the worst possible BU (Figure 3) (6). Patients report the severity of BU over the prior 24 hours, with weekly average scores calculated as the mean score over a 7-day period. Higher scores indicate worse BU severity (6). The Urgency NRS is easily understood by patients as it does not rely on specific descriptors that may not be relevant to all patients because of varied personal experiences of BU (6).

Figure 3.

Urgency Numerical Rating Scale (NRS), a patient-reported outcome measure to assess bowel urgency in adults with ulcerative colitis. Source: Dubinsky et al (6). Reproduced without changes per the Creative Commons license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/legalcode). For permission to reproduce or use the Urgency NRS, please contact copyright@lilly.com.

Multidimensional aspects of BU

BU is a multidimensional symptom, and its severity is associated with varied characteristics such as deferral time, context (e.g., bathroom accessibility), frequency of BU, previous experience, and the extent or burden of adaptive behaviors, such as carrying clean-up equipment (6,66,68,86,89,90). Deferral time is the period during which it is possible to defer defecation after the desire to evacuate (8). In a real-world cohort of patients with IBD, clinically relevant deferral time was defined as an inability to hold stool for 15 minutes (91). However, deferral time has been reported to be as low as 5 minutes or less in 28%–54% of patients with UC (8,45), and some patients report deferral times of less than 30 seconds (66). A method for assessing deferral time is asking patients, “Over the last week, how much urgency have you had before bowel movements?” with response scale options being none (“I can wait 15 minutes or more to have a bowel movement”), mild (“I need the bathroom within 5–15 minutes”), moderate (“I need the bathroom within 2–5 minutes”), moderately severe (“I need the bathroom in less than 2 minutes”), and too severe (“sometimes I am unable to make it to the bathroom in time”) (91). A further aspect of BU is fecal urge incontinence, which is distinct from passive incontinence and involves the accidental loss of stool when a person is unable to reach the toilet in time or despite efforts to retain stool (8,14,59,92,93).

TREATMENTS FOR BU

In the same way that BU contributes to overall patient burden in UC, it also influences treatment satisfaction. In a global survey of patients with UC, BU was listed as one of the top 3 factors contributing to treatment satisfaction (18). Results from a survey of 502 European patients with UC reported that 37% were dissatisfied with their current treatment, noting overall lack of efficacy and uncontrolled symptoms; patients that were in remission (66% of those surveyed) noted that UC symptoms such as BU, pain, and fatigue were refractory (94). Although BU can occur in remission or quiescent disease, it is strongly associated with active IBD across measures and can improve with treatment (43,95). The management of BU can be complicated as there is limited evidence on the efficacy of therapies for BU independent of IBD disease activity (17).

Most pharmacotherapy for UC targets the inflammation characteristic of active disease. Treatment with upadacitinib, a Janus kinase inhibitor, has been associated with significant improvements in BU alongside the achievement of clinical response and remission (46,96,97). Mirikizumab, a monoclonal antibody targeting the p19 subunit of interleukin 23, has also demonstrated effectiveness in reducing BU. A significantly greater proportion of patients treated with mirikizumab reported no BU at week 12 versus those receiving placebo, and this improvement was sustained through week 52 (97,98). Absence of BU was significantly associated with achievement of clinical response, clinical remission, Mayo stool frequency remission, Mayo rectal bleeding remission, Mayo endoscopic remission, histologic remission, and mucosal healing at weeks 12 and 52 (18,98).

Antidiarrheal agents (e.g., loperamide) can improve BU caused by both inflammatory and noninflammatory mechanisms (93,97). In cases where BU is driven by a functional bowel disorder such as IBS, anti-inflammatory therapies may not be effective. In a trial evaluating mesalazine in patients with IBS, improving BU was designated as a secondary objective, and a subset of patients with postinfectious IBS (N = 13) reported a reduction in BU severity after treatment. However, in the main analysis (N = 136), patients receiving placebo experienced significantly fewer days with BU versus those treated with mesalazine (99). In quiescent IBD (i.e., symptomatic control), tricyclic antidepressants (e.g., amitriptyline, nortriptyline, and desipramine) have improved refractory symptoms including BU (97,100).

Supportive measures to mitigate fecal incontinence and associated BU include avoiding triggering foods, keeping consistent bowel habits, improving hygiene, and reducing fiber and caffeine intake. Caffeinated coffee drinks have a sizeable impact on the experience of BU. Caffeine in coffee heightens gastrocolonic responses, increasing motility of the colon. This stimulates the small intestine's secretion of fluid. Limiting caffeine, especially after meals, can lessen experiences of BU and diarrhea that take place after meals (93).

Biofeedback can serve as a safe, effective, and inexpensive means of treating symptoms of UC, including BU, by strengthening anorectal function (93,101). Biofeedback, which encompasses exercises of the pelvic floor and anal sphincter, helps patients manage rectal hypersensitivity, and hypersensitivity can contribute to feelings of BU (25,35,101). In patients with quiescent IBD, biofeedback therapy has been demonstrated to improve fecal incontinence as well as overall QoL (35). In a study of patients with IBD (Crohn disease, N = 23; UC, N = 6) with dyssynergic defecation (including BU) assessed with anorectal manometric testing and treated with biofeedback therapy, 30% of those who completed biofeedback therapy had a clinically significant improvement in Short Inflammatory Bowel Disease Questionnaire scores with a significant reduction in healthcare utilization through 6 months (P = 0.02) (77). Results from randomized controlled trials indicate that biofeedback in adults is a more effective treatment for dyssynergic defecation than laxatives, general muscle relaxation exercises, and drugs inducing muscle relaxation (102). Biofeedback is also effective in treating refractory symptoms in patients with quiescent IBD and functional bowel disorders (36).

A holistic approach to managing BU includes patient education, emotional and psychosocial support, as well as biofeedback and pharmacotherapy if needed (17). In cases of functional bowel disorders in the setting of quiescent IBD, treatment should be individualized for each patient, targeting specific symptoms with the goal of improving overall QoL (36).

CLINICAL GUIDELINES FOR BU

Clinical guidelines addressing BU include those from the American College of Gastroenterology (ACG), the American Gastroenterology Association, the British Society of Gastroenterology, the European Crohn and Colitis Organisation, the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, the Nurses European Crohn and Colitis Organisation, and the World Gastroenterology Organisation (66,103–108). Excerpts related to BU from UC guidelines are presented in Table 4.

Table 4.

Excerpts related to bowel urgency from current UC guidelines

The ACG clinical guideline for UC in adults is the most comprehensive with respect to BU. This guideline recommends that UC be suspected in patients with hematochezia and BU (103). If diagnosed, initial treatment of UC should focus on restoration of normal bowel frequency and control of bleeding and BU (103). The guideline also describes initial presentations of UC as characterized by symptoms of an inflamed rectum: bleeding, BU, and tenesmus (103). The guideline further states that the symptoms used to assess UC should include BU, abdominal pain, cramping, and weight loss (103). The guideline also recommends using the ACG Ulcerative Colitis Activity Index and the Simple Clinical Colitis Activity Index for clinical evaluations. Both indices include assessments of BU as a component (103).

The European Crohn and Colitis Organisation guideline for UC recommends that a full medical history should include detailed questioning about the onset of UC symptoms, which depends on the extent and severity of disease and includes BU (107). In addition, the guideline points out that BU is the most common cause of failure in an ileorectal anastomosis (107).

FUTURE OUTLOOK FOR THE MANAGEMENT OF UC FROM THE VIEWPOINT OF BU

Despite its impact on QoL and psychosocial function, BU is often neglected as a clinical symptom in UC. The mechanism of BU in UC is multifactorial, but the inflammatory component is responsive to treatment, so BU can serve as a measure of insufficient disease control in active disease. Despite being one of the symptoms patients with UC most want improved, it is often not discussed during consultations or prioritized in treatment decisions. Awareness of the importance of BU and its effect on patients' lives must improve.

With these considerations in mind, BU should be considered a third key PRO in UC in addition to rectal bleeding and stool frequency. Reduction in BU severity should be included in the definition of symptomatic and clinical remission. BU was not used to measure a return-to-normal QoL in STRIDE-II (83) and should be included as a treat-to-target measure in STRIDE-III. Although BU represents a PRO important to patients with UC, it is often not assessed. The evaluation and management of BU can improve QoL and treatment satisfaction of patients with UC. Prospective research on the association of improved clinical outcomes with improved BU is needed. Future directions include a deeper understanding of the mechanisms driving BU and the use of additional assessments that quantify BU severity that can accurately measure treatment efficacy, ultimately improving the lives of patients with UC.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

Guarantor of the article: Marla Dubinsky, MD.

Specific author contributions: All authors contributed to searching the literature and drafting the manuscript, and approved the final draft submitted.

Financial support: This narrative review was supported by Eli Lilly and Company. Authors who are employees of the sponsor played a role in interpreting the published studies included in this review and writing the manuscript. Medical writing support was provided by Andrew Sakko, PhD, CMPP, and Nicole Lipitz, and editorial support was provided by Antonia Baldo and Raena Fernandes, of Syneos Health, and funded by Eli Lilly and Company in accordance with Good Publication Practice (GPP 2022) guidelines (www.ismpp.org/gpp-2022).

Potential competing interests: A.P.B., T.H.G., C.K., and I.R. are employees of, and own stock in, Eli Lilly and Company. A.D. reports fees for participation in clinical trials, review activities such as data monitoring boards, statistical analysis, and end point committees from AbbVie, Bristol Myers Squibb, Falk Foundation, Gilead Sciences, Janssen, and Pfizer; consultancy fees from AbbVie, Amgen, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol Myers Squibb, Celltrion, Eli Lilly and Company, Falk Foundation, Ferring Pharmaceuticals, Fresenius Kabi, Galapagos, Hexal, Janssen, MSD, Pfizer, Pharmacosmos, Roche, Sandoz, Takeda, and Tillotts Pharma; payment from lectures including service on speakers bureaus from AbbVie, Celltrion, Falk Foundation, Ferring Pharmaceuticals, Galapagos, Gilead Sciences, Janssen, MSD, Pfizer, Pharmacosmos, Takeda, and Tillotts Pharma; and payment for article preparation from Eli Lilly and Company, Falk Foundation, Pfizer, and Takeda. M.D. reports consultancy fees from AbbVie, Arena Pharmaceuticals, Bristol Myers Squibb, Celgene, Eli Lilly and Company, Gilead Sciences, Janssen, Pfizer, Takeda, and UCB. T.H. is an editor of Intestinal Research and reports grants, personal fees, and/or other funds from AbbVie, Aspen Pharmacare, Celltrion, EA Pharma, Eli Lilly and Company, Ferring Pharmaceuticals, Gilead Sciences, Janssen, JIMRO, Kissei Pharmaceutical, Kyorin Pharmaceutical, Mitsubishi Tanabe Pharma, Miyarisan Pharmaceutical, Mochida Pharmaceutical, Nichi-Iko Pharmaceutical, Nippon Kayaku, Otsuka, Pfizer, Takeda, and Zeria Pharmaceutical. R.P. reports consulting and/or lecture fees from AbbVie, Abbott, Alimentiv (formerly Robarts), Amgen, Arena Pharmaceuticals, AstraZeneca, Biogen, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol Myers Squibb, Celgene, Celltrion, Cosmo Pharmaceuticals, Eisai, Elan Corporation, Eli Lilly and Company, Ferring Pharmaceuticals, Galapagos, Genentech, Gilead Sciences, GlaxoSmithKline, Janssen, Merck, Mylan, Oppilan Pharma, Pandion Therapeutics, Pfizer, Progenity, Protagonist Therapeutics, Roche, Sandoz, Satisfai Health, Shire, Sublimity Therapeutics, Takeda, Theravance Biopharma, and UCB. D.R. reports grant support from Takeda and has served as a consultant for AbbVie, AltruBio, Arena Pharmaceuticals, Bristol Myers Squibb, Eli Lilly and Company, Genentech, Gilead Sciences, Iterative Scopes, Janssen, Pfizer, Prometheus Biosciences, Roche, Takeda, and Techlab. S.S. reports no conflicts of interest. S.T. reports grants and/or research support from AbbVie, Buhlmann Diagnostics, Celgene, Eli Lilly and Company, the International Organization for the Study of Inflammatory Bowel Disease, Janssen, the Norman Collisson Foundation, Takeda, UCB, and Vifor Pharma; consulting fees from Abacus Pharmaceuticals, AbbVie, Actial, ai4gi, Alcimed, Allergan, Amgen, Arena Pharmaceuticals, Asahi Kasei Pharma, Astellas Pharma, AstraZeneca, Atlantic Pharmaceuticals, Barco, Biocare Pharma, Biogen, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol Myers Squibb, Buhlmann Diagnostics, Calcico, Celgene, Cellerix, Celsius Healthcare, Cerimon Pharmaceuticals, ChemoCentryx, Cisbio, Coronado Biosciences, Cosmo Pharmaceuticals, Ducentis BioTherapeutics, Dynavax, Elan Corporation, Eli Lilly and Company, Enterome, Falk Foundation, Ferring Pharmaceuticals, FPRT Bio, Giuliani, Genentech, Genzyme, GlaxoSmithKline, Glenmark Pharmaceuticals, Grünenthal, GW Pharmaceuticals, Immunocore, Immunometabolism, Indigo Biosciences, Janssen, Lexicon Pharmaceuticals, Medarex, Merck, MSD, Neovacs, Netbiotix, Novartis, Novo Nordisk, NPS Pharma, Ocera Therapeutics, Otsuka, Palau Pharma, Pentax Medical, Pfizer, Philips, Procter & Gamble, Pronota, Proximagen, Ptima Pharma, Receptos, Resolute, Robarts Pharmaceutical, Roche, Sandoz, Santarus, Sensyne Health, Shire, Sigmoid Pharma, SynDermix, Synthon, Takeda, Theravance Biopharma, TiGenix, Tillotts Pharma, TopiVert, TxCell, UCB, Vertex, VHsquared, Vifor Pharma, Warner Chilcott, and Zeria Pharmaceutical; and speaker fees from AbbVie, Amgen, Biogen, Falk Foundation, Ferring Pharmaceuticals, GlaxoSmithKline, Janssen, Shire, Takeda, and Zeria Pharmaceutical.

Contributor Information

Alison Potts Bleakman, Email: potts_alison@lilly.com.

Remo Panaccione, Email: rpanacci@ucalgary.ca.

Toshifumi Hibi, Email: thibi@insti.kitasato-u.ac.jp.

Stefan Schreiber, Email: s.schreiber@ikmb.uni-kiel.de.

David Rubin, Email: drubin@uchicago.edu.

Axel Dignass, Email: Axel.Dignass@agaplesion.de.

Isabel Redondo, Email: redondo_isabel1@lilly.com.

Theresa Hunter Gibble, Email: hunter_theresa_marie@lilly.com.

Cem Kayhan, Email: kayhan_cem@lilly.com.

Simon Travis, Email: simon.travis@kennedy.ox.ac.uk.

REFERENCES

- 1.Perler BK, Ungaro R, Baird G, et al. Presenting symptoms in inflammatory bowel disease: Descriptive analysis of a community-based inception cohort. BMC Gastroenterol 2019;19(1):47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Newton L, Randall JA, Hunter T, et al. A qualitative study exploring the health-related quality of life and symptomatic experiences of adults and adolescents with ulcerative colitis. J Patient Rep Outcomes 2019;3(1):66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sninsky JA, Barnes EL, Zhang X, et al. Urgency and its association with quality of life and clinical outcomes in patients with ulcerative colitis. Am J Gastroenterol 2022;117(5):769–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.US Department of Health and Human Services (FDA Guidance for UC Endpoints). 2016. (https://www.fda.gov/media/99526/download). Accessed October 26, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 5.MedlinePlus (https://medlineplus.gov/ency/article/003131.htm). Accessed October 26, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dubinsky MC, Irving PM, Panaccione R, et al. Incorporating patient experience into drug development for ulcerative colitis: Development of the Urgency Numeric Rating Scale, a patient-reported outcome measure to assess bowel urgency in adults. J Patient Rep Outcomes 2022;6(1):31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lamb CA, Kennedy NA, Raine T, et al. British Society of Gastroenterology consensus guidelines on the management of inflammatory bowel disease in adults. Gut 2019;68(Suppl 3):s1–106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Petryszyn PW, Paradowski L. Stool patterns and symptoms of disordered anorectal function in patients with inflammatory bowel diseases. Adv Clin Exp Med 2018;27(6):813–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hibi T, Ishibashi T, Ikenoue Y, et al. Ulcerative colitis: Disease burden, impact on daily life, and reluctance to consult medical professionals: Results from a Japanese Internet Survey. Inflamm Intest Dis 2020;5(1):27–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Singh S, Allegretti JR, Siddique SM, et al. AGA technical review on the management of moderate to severe ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterology 2020;158(5):1465–96.e17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tew GA, Jones K, Mikocka-Walus A. Physical activity habits, limitations, and predictors in people with inflammatory bowel disease: A large cross-sectional online survey. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2016;22(12):2933–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dibley L, Norton C, Whitehead E. The experience of stigma in inflammatory bowel disease: An interpretive (hermeneutic) phenomenological study. J Adv Nurs 2018;74(4):838–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Larsson K, Lööf L, Nordin K. Stress, coping and support needs of patients with ulcerative colitis or Crohn's disease: A qualitative descriptive study. J Clin Nurs 2017;26(5-6):648–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dibley L, Norton C. Experiences of fecal incontinence in people with inflammatory bowel disease: Self-reported experiences among a community sample. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2013;19(7):1450–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schreiber S, Panés J, Louis E, et al. Perception gaps between patients with ulcerative colitis and healthcare professionals: An online survey. BMC Gastroenterol 2012;12:108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nakase H, Hirano T, Wagatsuma K, et al. Artificial intelligence-assisted endoscopy changes the definition of mucosal healing in ulcerative colitis. Dig Endosc 2021;33(6):903–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pakpoor J, Travis S. Why studying urgency is urgent. Gastroenterol Hepatol 2023;19(2):95–100. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dubinsky MC, Watanabe K, Molander P, et al. Ulcerative colitis narrative global survey findings: The impact of living with ulcerative colitis-patients' and physicians' view. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2021;27(11):1747–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sands BE, Sandborn WJ, Panaccione R, et al. Ustekinumab as induction and maintenance therapy for ulcerative colitis. N Engl J Med 2019;381(13):1201–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Camarillo GF, Goyon EI, Zuñiga RB, et al. Gene expression profiling of mediators associated with the inflammatory pathways in the intestinal tissue from patients with ulcerative colitis. Mediators Inflamm 2020;2020:9238970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rao SS, Read NW, Davison PA, et al. Anorectal sensitivity and responses to rectal distention in patients with ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterology 1987;93(6):1270–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Drewes AM, Frøkjaer JB, Larsen E, et al. Pain and mechanical properties of the rectum in patients with active ulcerative colitis. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2006;12(4):294–303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Limdi JK, Vasant DH. Anorectal dysfunction in distal ulcerative colitis: Challenges and opportunities for topical therapy. J Crohns Colitis 2016;10(4):503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gordon IO, Agrawal N, Willis E, et al. Fibrosis in ulcerative colitis is directly linked to severity and chronicity of mucosal inflammation. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2018;47(7):922–39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Casanova MJ, Santander C, Gisbert JP. Rectal hypersensitivity in patients with quiescent ulcerative colitis. J Crohns Colitis 2015;9(7):592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Krugliak Cleveland N, Rai V, El Jurdi K, et al. Ulcerative colitis patients have reduced rectal compliance compared with non-inflammatory bowel disease controls. Gastroenterology 2022;162(1):331–3.e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Krugliak Cleveland N, Torres J, Rubin DT. What does disease progression look like in ulcerative colitis, and how might it be prevented? Gastroenterology 2022;162(5):1396–408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lach G, Schellekens H, Dinan TG, et al. Anxiety, depression, and the microbiome: A role for gut peptides. Neurotherapeutics 2018;15(1):36–59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ford AC, Lacy BE, Talley NJ. Irritable bowel syndrome. N Engl J Med 2017;376(26):2566–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Holtmann GJ, Ford AC, Talley NJ. Pathophysiology of irritable bowel syndrome. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol 2016;1(2):133–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Greig E, Sandle GI. Diarrhea in ulcerative colitis. The role of altered colonic sodium transport. Ann N Y Acad Sci 2000;915:327–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Papathanasopoulos AA, Katsanos KH, Tatsioni A, et al. Increased fatigability of external anal sphincter in inflammatory bowel disease: Significance in fecal urgency and incontinence. J Crohns Colitis 2010;4(5):553–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tanaka Y, Kanazawa M, Fukudo S, et al. Biopsychosocial model of irritable bowel syndrome. J Neurogastroenterol Motil 2011;17(2):131–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Peppas S, Pansieri C, Piovani D, et al. The brain-gut Axis: Psychological functioning and inflammatory bowel diseases. J Clin Med 2021;10(3):377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Vasant DH, Limdi JK, Solanki K, et al. Biofeedback therapy improves continence in quiescent inflammatory bowel disease patients with ano-rectal dysfunction. J Gastroenterol Pancreatol Liver 2016;3(2):1–4. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nigam GB, Limdi JK, Vasant DH. Current perspectives on the diagnosis and management of functional anorectal disorders in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Ther Adv Gastroenterol 2018;11:1756284818816956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Teich N, Schulze H, Knop J, et al. Novel approaches identifying relevant patient-reported outcomes in patients with inflammatory bowel diseases—LISTEN 1. Crohns Colitis 360 2021;3(3):otab050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nóbrega VG, Silva INN, Brito BS, et al. The onset of clinical manifestations in inflammatory bowel disease patients. Arq Gastroenterol 2018;55(3):290–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dulai PS, Jairath V, Khanna R, et al. Development of the symptoms and impacts questionnaire for Crohn's disease and ulcerative colitis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2020;51(11):1047–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ueno F, Nakayama Y, Hagiwara E, et al. Impact of inflammatory bowel disease on Japanese patients' quality of life: Results of a patient questionnaire survey. J Gastroenterol 2017;52(5):555–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lönnfors S, Vermeire S, Greco M, et al. IBD and health-related quality of life—Discovering the true impact. J Crohns Colitis 2014;8(10):1281–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Travis S, Bleakman AP, Rubin DT, et al. P303 Bowel urgency communication gap between health care professionals and patients with ulcerative colitis in the US and Europe: CONFIDE survey. Gut 2023;72:A209–A210. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kulyk A, Shafer LA, Graff LA, et al. Urgency for bowel movements is a highly discriminatory symptom of active disease in persons with IBD (the Manitoba Living with IBD study). Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2022;56(11-12):1570–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Schreiber S, et al. Hybrid Conference. Virtual. Vienna, Austria, October 08-11, 2022. Poster 0296. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Dawwas GK, Jajeh H, Shan M, et al. Prevalence and factors associated with fecal urgency among patients with ulcerative colitis and Crohn's disease in the study of a prospective adult research cohort with inflammatory bowel disease. Crohns Colitis 360 2021;3(3):otab046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ghosh S, Sanchez Gonzalez Y, Zhou W, et al. Upadacitinib treatment improves symptoms of bowel urgency and abdominal pain, and correlates with quality of life improvements in patients with moderate to severe ulcerative colitis. J Crohns Colitis 2021;15(12):2022–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Dubinsky MC, Clemow DB, Hunter Gibble T, et al. Clinical effect of mirikizumab treatment on bowel urgency in patients with moderately to severely active ulcerative colitis and the clinical relevance of bowel urgency improvement for disease remission. Crohns Colitis 360 2023;5(1):otac044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Travis SP, Higgins PD, Orchard T, et al. Review article: Defining remission in ulcerative colitis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2011;34(2):113–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rubin DT, Sninsky C, Siegmund B, et al. International perspectives on management of inflammatory bowel disease: Opinion differences and similarities between patients and physicians from the IBD GAPPS survey. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2021;27(12):1942–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Casellas F, Herrera-de Guise C, Robles V, et al. Patient preferences for inflammatory bowel disease treatment objectives. Dig Liver Dis 2017;49(2):152–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Louis E, Ramos-Goñi JM, Cuervo J, et al. A qualitative research for defining meaningful attributes for the treatment of inflammatory bowel disease from the patient perspective. Patient 2020;13(3):317–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Carpio D, López-Sanromán A, Calvet X, et al. Perception of disease burden and treatment satisfaction in patients with ulcerative colitis from outpatient clinics in Spain: UC-LIFE survey. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2016;28(9):1056–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Gajendran M, Loganathan P, Jimenez G, et al. A comprehensive review and update on ulcerative colitis. Dis Mon 2019;65(12):100851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hanauer SB. Review article: The long-term management of ulcerative colitis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2004;20(Suppl 4):97–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sandborn WJ, Feagan BG, Hanauer SB, et al. The guide to guidelines in ulcerative colitis: Interpretation and appropriate use in clinical practice. Gastroenterol Hepatol 2021;17(4 Suppl 4):3–13. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ma C, Hanzel J, Panaccione R, et al. CORE-IBD: A multidisciplinary international consensus initiative to develop a core outcome set for randomized controlled trials in inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterology 2022;163(4):950–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Higgins PD, Schwartz M, Mapili J, et al. Is endoscopy necessary for the measurement of disease activity in ulcerative colitis? Am J Gastroenterol 2005;100(2):355–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Higgins PDR, Harding G, Revicki DA, et al. Development and validation of the ulcerative colitis patient-reported outcomes signs and symptoms (UC-pro/SS) diary. J Patient Rep Outcomes 2017;2(1):26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.van Deen WK, Obremskey A, Moore G, et al. An assessment of symptom burden in inflammatory bowel diseases to develop a patient preference-weighted symptom score. Qual Life Res 2020;29(12):3387–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Connor SJ, Sechi A, Andrade M, et al. Ulcerative colitis narrative findings: Australian survey data comparing patient and physician disease management views. JGH Open 2021;5(9):1033–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Waljee AK, Joyce JC, Wren PA, et al. Patient reported symptoms during an ulcerative colitis flare: A qualitative focus group study. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2009;21(5):558–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Schreiber S, Travis S, Bleakman AP, et al. 2022 Crohn's & Colitis Congress. Hybrid-Virtual/Las Vegas, NV, USA. January 20-22, 2022. Presentation P002.

- 63.Miller J, et al. American College of Gastroenterology Annual Meeting 2014. Philadelphia, PA, USA. October 17-22, 2014. Presentation 2211.

- 64.Dubinsky MC, Schreiber S, Bleakman AP, et al. 17th Congress of the European Crohn's and Colitis Organisation. Virtual. February 16-19, 2022. Presentation P087.

- 65.Travis S, et al. Digestive Disease Week 2022. San Diego, CA, USA. May 21-24, 2022. Presentation 978.

- 66.Kemp K, Dibley L, Chauhan U, et al. Second N-ECCO consensus statements on the European nursing roles in caring for patients with Crohn's disease or ulcerative colitis. J Crohns Colitis 2018;12(7):760–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Tse CS, Shah S, Crate D, et al. Top goals and concerns reported by individuals with inflammatory bowel disease at outpatient gastroenterology clinic visits. Gastroenterology 2020;158(3 Suppl):S92–3. Conference: 2020 Crohn's & Colitis Congress, Austin, TX, February 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Schreiber S, Travis S, Bleakman AP, et al. Communicating needs and features of IBD experiences (confide) survey: Burden and impact of bowel urgency on patients with moderate to severe ulcerative colitis. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2022;28(Suppl 1):S79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Dubinsky MC, Schreiber S, Potts Bleakman A, et al. P087 Communicating needs and features of IBD experiences (CONFIDE) survey: Impact of ulcerative colitis symptoms on daily life. J Crohns Colitis 2022;16(Suppl 1):i186–7. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Rasmussen B, Haastrup P, Wehberg S, et al. Predictors of health-related quality of life in patients with moderate to severely active ulcerative colitis receiving biological therapy. Scand J Gastroenterol 2020;55(6):656–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Rezaie A, Gu P, Kaplan GG, et al. Dyssynergic defecation in inflammatory bowel disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2018;24(5):1065–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Nigam GB, Limdi JK, Hamdy S, et al. P1403—The hidden burden of faecal incontinence in active and quiescent ulcerative colitis: An underestimated problem? Am J Gastroenterol 2019;114(Suppl):S443. ACG 2019 Annual Scientific Meeting Abstracts. 2019; American College of Gastroenterology. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Travis S, et al. UEGW 2022 abstract: DV-007253.

- 74.Shreiber S, et al. UEGW 2022 abstract: DV-007256.

- 75.Theede K, Holck S, Ibsen P, et al. Level of fecal calprotectin correlates with endoscopic and histologic inflammation and identifies patients with mucosal healing in ulcerative colitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2015;13(11):1929–36.e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Bassotti G, Antonelli E, Villanacci V, et al. Abnormal gut motility in inflammatory bowel disease: An update. Tech Coloproctol 2020;24(4):275–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Perera LP, Ananthakrishnan AN, Guilday C, et al. Dyssynergic defecation: A treatable cause of persistent symptoms when inflammatory bowel disease is in remission. Dig Dis Sci 2013;58(12):3600–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Dragasevic S, Sokic-Milutinovic A, Stojkovic Lalosevic M, et al. Correlation of patient-reported outcome (PRO-2) with endoscopic and histological features in ulcerative colitis and Crohn's disease patients. Gastroenterol Res Pract 2020;2020:2065383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Walmsley RS, Ayres RC, Pounder RE, et al. A simple clinical colitis activity index. Gut 1998;43(1):29–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Walsh A, Cao R, Wong D, et al. Using item response theory (IRT) to improve the efficiency of the Simple Clinical Colitis Activity Index (SCCAI) for patients with ulcerative colitis. BMC Gastroenterol 2021;21(1):132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Mitchell R, Kremer A, Westwood N, et al. Talking about life and IBD: A paradigm for improving patient-physician communication. J Crohns Colitis 2009;3(1):1–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Wong D, Matini L, Kormilitzin A, et al. Patient reported outcomes: The ICHOM standard set for inflammatory bowel disease in real life practice helps quantify deficits in current care. J Crohns Colitis 2022;16(12):1874–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Turner D, Ricciuto A, Lewis A, et al. STRIDE-II: An update on the Selecting Therapeutic Targets in Inflammatory Bowel Disease (STRIDE) initiative of the International Organization for the Study of IBD (IOIBD): Determining therapeutic goals for treat-to-target strategies in IBD. Gastroenterology 2021;160(5):1570–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.FDA. Ulcerative Colitis: Clinical Trial Endpoints Guidance for Industry. 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 85.de Jong MJ, Roosen D, Degens J, et al. Development and validation of a patient-reported score to screen for mucosal inflammation in inflammatory bowel disease. J Crohns Colitis 2019;13(5):555–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Nag A, Romero B. Development and content validation of patient-reported outcomes tools for ulcerative colitis and Crohn's disease in adults with moderate-to-severe disease. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2022;20(1):75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Surti B, Spiegel B, Ippoliti A, et al. Assessing health status in inflammatory bowel disease using a novel single-item numeric rating scale. Dig Dis Sci 2013;58(5):1313–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Gries K, Berry P, Harrington M, et al. Literature review to assemble the evidence for response scales used in patient-reported outcome measures. J Patient Rep Outcomes 2017;2:41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Fawson S, Dibley L, Smith K, et al. Developing an online program for self-management of fatigue, pain, and urgency in inflammatory bowel disease: Patients' needs and wants. Dig Dis Sci 2022;67(7):2813–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Gavaler JS, Delemos B, Belle SH, et al. Ulcerative colitis disease activity as subjectively assessed by patient-completed questionnaires following orthotopic liver transplantation for sclerosing cholangitis. Dig Dis Sci 1991;36(3):321–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Kurt S, Caron B, Gouynou C, et al. Faecal incontinence in inflammatory bowel disease: The Nancy experience. Dig Liver Dis 2022;54(9):1195–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Kamal N, Motwani K, Wellington J, et al. Fecal incontinence in inflammatory bowel disease. Crohns Colitis 360 2021;3(2):otab013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Rao SS. Diagnosis and management of fecal incontinence. American College of Gastroenterology pPractice Parameters Committee. Am J Gastroenterol 2004;99(8):1585–604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Burisch J, Hart A, Oortwijn A, et al. P293 Insights from patients with ulcerative colitis on disease burden: Findings from a real-world survey in Europe. J Crohns Colitis 2022;16(Suppl 1):i324–5. [Google Scholar]

- 95.Joyce JC, Waljee AK, Khan T, et al. Identification of symptom domains in ulcerative colitis that occur frequently during flares and are responsive to changes in disease activity. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2008;6:69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Ghosh S, Louis E, Loftus EV, Jr, et al. Bowel urgency in patients with moderate to severe ulcerative colitis: Prevalence and correlation with clinical outcomes, biomarker levels, and health-related quality of life from U-ACHIEVE, a phase 2b study of upadacitinib. P283. J Crohns Colitis 2019;13(Suppl 1):S240–1. [Google Scholar]

- 97.Caron B, Ghosh S, Danese S, et al. Identifying, understanding and managing fecal urgency in inflammatory bowel diseases. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2023;21(6):1403–13.e27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Dubinsky M, Lee SD, Panaccione R, et al. Absence of bowel urgency is associated with significantly improved inflammatory bowel disease related quality of life in a phase 2 trial of mirikizumab in patients with ulcerative colitis. P0555. United Eur Gastroenterol J 2020;8(Suppl 8):144–887. [Google Scholar]

- 99.Lam C, Tan W, Leighton M, et al. Efficacy and Mechanism Evaluation. Efficacy and Mode of Action of Mesalazine in the Treatment of Diarrhoea-Predominant Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS-D): A Multicentre, Parallel-Group, Randomised Placebo-Controlled Trial. NIHR Journals Library Copyright Queen's Printer and Controller of HMSO: Southampton, United Kingdom, 2015. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Iskandar HN, Cassell B, Kanuri N, et al. Tricyclic antidepressants for management of residual symptoms in inflammatory bowel disease. J Clin Gastroenterol 2014;48(5):423–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Wang JY, Abbas MA. Current management of fecal incontinence. Permanente J 2013;17(3):65–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Chiarioni G, Heymen S, Whitehead WE. Biofeedback therapy for dyssynergic defecation. World J Gastroenterol 2006;12(44):7069–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Rubin DT, Ananthakrishnan AN, Siegel CA, et al. ACG clinical guideline: Ulcerative colitis in adults. Am J Gastroenterol 2019;114(3):384–413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Ananthakrishnan AN, Nguyen GC, Bernstein CN. AGA clinical practice update on management of inflammatory bowel disease in elderly patients: Expert review. Gastroenterology 2021;160(1):445–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Bernstein CN, Eliakim A, Fedail S, et al. World Gastroenterology Organisation global guidelines inflammatory bowel disease: Update August 2015. J Clin Gastroenterol 2016;50(10):803–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Carter MJ, Lobo AJ, Travis SP. Guidelines for the management of inflammatory bowel disease in adults. Gut 2004;53(Suppl 5):V1–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Magro F, Gionchetti P, Eliakim R, et al. Third European evidence-based consensus on diagnosis and management of ulcerative colitis. Part 1: Definitions, diagnosis, extra-intestinal manifestations, pregnancy, cancer surveillance, surgery, and ileo-anal pouch disorders. J Crohns Colitis 2017;11(6):649–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Abdulrazeg O, Li B, Epstein J, et al. Management of ulcerative colitis: Summary of updated NICE guidance. BMJ 2019;367:l5897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]