Abstract

Using cultivation, immunofluorescence microscopy, and scanning electron microscopy, we demonstrated the presence of viable enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli O157:H7 not only on the outer surfaces but also in the inner tissues and stomata of cotyledons of radish sprouts grown from seeds experimentally contaminated with the bacterium. HgCl2 treatment of the outer surface of the hypocotyl did not kill the contaminating bacteria, which emphasized the importance of either using seeds free from E. coli O157:H7 in the production of radish sprouts or heating the sprouts before they are eaten.

Hydroponically grown radish (Raphanus sativus) sprouts were suspected to be the vehicle of a large outbreak of Escherichia coli O157:H7 infections in Sakai City, Japan, in 1996 (8) and in small outbreaks in Yokohama and Gamagori City, Japan, in 1997. To determine whether radish sprouts could serve as a vehicle for transmission of human-pathogenic microorganisms, we investigated the proliferation of E. coli O157:H7 during growth of radish sprouts and demonstrated previously (4) that in experimentally contaminated radish seeds, E. coli O157:H7 proliferated 103- to 105-fold at an early stage of plant growth, including germination, and that the bacteria were located in edible parts of radish sprouts. Also, we demonstrated that the edible parts (hypocotyls and cotyledons) of radish sprouts could be contaminated when the roots were immersed in a bacterial suspension. These findings suggested that like alfalfa (2, 3, 5, 7, 9) and mung beans (1), radish sprouts could pose a health risk if seeds or hydroponic water were contaminated with bacteria which cause food-borne diseases. In this study we tried to determine whether E. coli O157:H7, which was considered a nonphytopathogenic bacterium, could exist in a viable and culturable form in radish sprouts.

Detection of E. coli O157:H7 by immunofluorescence microscopy.

Based on our previous study (4), we developed an experimental model for radish sprouts highly contaminated with E. coli O157:H7. An isolate of E. coli O157:H7 from a patient from the outbreak in Sakai City (strain 212) was grown in Trypticase soy broth (Becton Dickinson, Cockeysville, Md.) overnight at 37°C and then diluted with sterile water to a concentration of 103 CFU/ml. Radish seeds purchased from a retail store in Kanagawa Prefecture, Japan, were soaked in the water containing E. coli O157:H7, and then sprouts were grown at room temperature (18 to 25°C) for 7 days. The localization of E. coli O157:H7 in the edible parts of contaminated radish sprouts was studied by immunofluorescence microscopy and immunoelectron microscopy. For immunofluorescence microscopy, the edible parts were fixed in formalin–acetic acid–70% ethanol (1:1:18), dehydrated in a graded ethanol series, and used to prepare conventional paraffin sections. The sections were dewaxed with xylene and then hydrated in a graded ethanol series. After nonspecific binding was blocked with 2% normal goat serum in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) for 1 h and the preparations were washed with PBS six times (5 min each), the sections were incubated for 90 min with primary rabbit anti-E. coli O157:H7 polyclonal antibody (a kind gift from K. Tamura, Department of Bacteriology, National Institute of Infectious Diseases), which has been found not to react to bacteria other than E. coli. The sections were then washed with PBS. They were then incubated with the fluorescein-conjugated goat anti-rabbit immunoglobulin G Fab fragment (Cappel Research Products, Durham, N.C.) for 30 min, washed six times with PBS and three times with distilled water, and then immersed in 90% glycerol in PBS for fluorescence microscopy. Rabbit antibody against Salmonella enteritidis was used as a negative control.

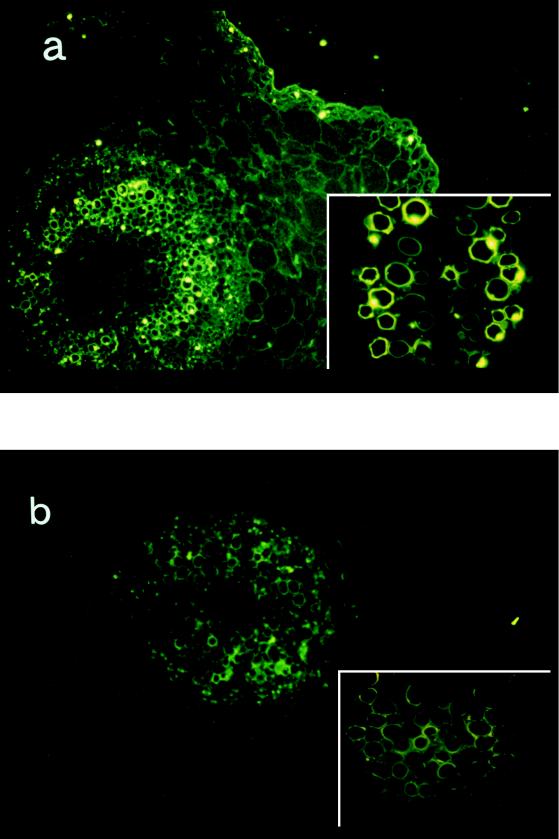

There was positive fluorescence in and on the walls of vessels and just beneath the epidermis of the hypocotyls of contaminated sprouts (Fig. 1a). This fluorescence was not detected in noncontaminated sprouts (Fig. 1b), suggesting that E. coli O157:H7 was present in the inner tissues of contaminated sprouts.

FIG. 1.

Contaminated radish sprouts as shown by fluorescence microscopy. Horizontal sections were prepared and stained with the antibody against E. coli O157:H7. (a) Contaminated sprouts. The fluorescence was caused by antibody against E. coli O157:H7 binding. (b) Noncontaminated control sprouts. (a and b) Magnification, ×100. (Insets) Magnification, ×400.

Detection of E. coli O157:H7 by scanning immunoelectron microscopy.

For scanning electron microscopy, the tissue specimens were further fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde and 0.25% glutaraldehyde for 2 h, washed with PBS, and incubated with 1% bovine serum albumin in PBS for 30 min. They were again washed with PBS and incubated for 1 h with the same primary antibody solution containing 0.1% bovine serum albumin. After being washed with PBS, they were dipped in a 15-nm-diameter colloidal gold-labeled anti-rabbit immunoglobulin (electron microscopy grade; British Biocell International, Cardiff, United Kingdom) solution, washed again with PBS, and then postfixed with 2% paraformaldehyde and 2.5% glutaraldehyde for 30 min. After dehydration in a graded acetone series, they were dried by critical point drying with liquid CO2 dryer (HCP-2 type; Hitachi), coated with osmium with a model NL-OPC 80A osmium plasma coater (Nippon Laser & Electronic Laboratory), and examined by scanning electron microscopy with a Hitachi model S-5000 microscope.

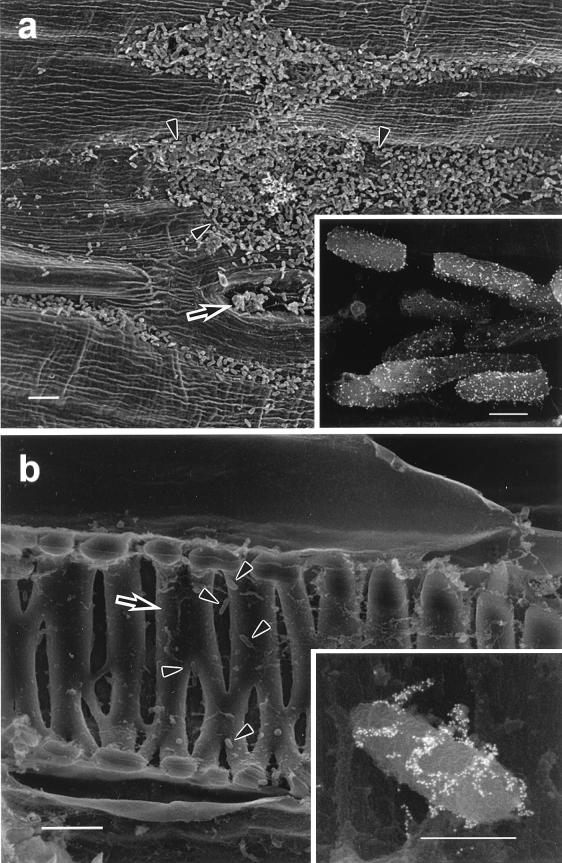

Numerous bacteria were present on the outer surfaces, including the stomata, of contaminated sprouts (Fig. 2a). As determined by the immunostaining studies, almost all of the bacterial cells on the outer surfaces of the radish sprouts which were grown from contaminated seeds appeared to be E. coli O157:H7 cells (Fig. 2a, inset). Several kinds of bacteria were present inside the hypocotyls of radish sprouts (Fig. 2b). Although E. coli O157:H7 was not present inside the hypocotyls as frequently as other species of bacteria, there certainly were bacterial cells bound to anti-E. coli O157:H7 (Fig. 2b, inset).

FIG. 2.

Contaminated radish sprouts as shown by scanning electron microscopy. (a) Outer surface. The arrow indicates a stomate, and the arrowheads indicate bacteria. (b) Inner surface. The arrow indicates the xylem, and the arrowheads indicate bacteria. Insets show sections stained with E. coli O157:H7 antibody. (a and b) Bar = 5 μm. (Insets) Bar = 50 nm.

Detection of E. coli O157:H7 by cultivation.

In order to ascertain whether the E. coli O157:H7 in the inner tissues of cotyledons was culturable, 4-cm sections of the edible parts (cotyledons and hypocotyls) of the sprouts grown from E. coli O157:H7-contaminated seeds were subjected to a common plant surface disinfection procedure involving HgCl2 (6), and then the sections were examined for the presence of the bacteria. For surface disinfection, the sections were immersed in 80% ethanol for 4 to 5 s and in 0.1% HgCl2 for various periods of time and then washed in sterile water three times to remove the HgCl2. The excess water on the surface was wiped off with sterilized filter paper. During this procedure, each section was held upside down to prevent the cut edge from absorbing the HgCl2 into the hypocotyl. For 20 sections, the 1.5-cm disinfected part of the hypocotyl was cut out, and the specimens were then placed on rainbow agar O157 plates (Biolog Inc., Hayward, Calif.). Another 20 pieces were sliced in half with a surgical knife from the base of the cotyledon parallel to the vascular bundle of the hypocotyl, and the sliced surface of each hypocotyl was placed on an agar plate. After being kept on the agar for 10 min, all of the sections were removed from the plates, which were then incubated overnight at 37°C and examined for colony formation. As shown in Table 1, E. coli O157:H7 was recovered from the outer surface of 1 of the 20 sections treated with HgCl2 for 1 or 2 min, but not from any of the sections treated for 4 or 10 min. On the other hand, when the sliced surfaces were used, bacteria were detected with two and seven of the sections treated for 4 and 10 min, respectively. The colonies were confirmed to be E. coli O157:H7 colonies with an E. coli O157 latex agglutination assay kit (UNI kit; Unipath Ltd., Hampshire, United Kingdom) and by a PCR performed with DNA probes for verotoxins (O157 PCR screening set; Takara Biomedicals, Tokyo, Japan).

TABLE 1.

Detection of E. coli O157:H7 in hypocotyl sections of radish sprouts treated with HgCl2

| Contact surface on agar plates | Expt | No. of positive sections/no. tested after HgCl2 treatment for:

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 min | 0.5 min | 1 min | 2 min | 4 min | 10 min | ||

| Sliced surface | 1 | 5/10 | 2/10 | 1/10 | 1/10 | 1/10 | 1/10 |

| 2 | 7/10 | 3/10 | 1/10 | 4/10 | 1/10 | 6/10 | |

| Outer surface | 3 | 7/10 (3.0)a | 9/10 (5.5) | 0/10 (2.6) | 0/10 (ND) | 0/10 (5.0) | 0/10 (ND) |

| 4 | 10/10 (4.1) | 6/10 (3.1) | 1/10 (2.3) | 1/10 (2.3) | 0/10 (5.9) | 0/10 (3.3) | |

The number in parentheses is the number (log CFU) of E. coli O157:H7 in the homogenate of the 10 sections tested. ND, not detected.

Ten unsliced hypocotyl sections which had been placed on an agar plate were crushed by hand to push out their contents into 10 ml of Trypticase soy broth before stomaching with a model 400 Stomacher (A. J. Seward, London, United Kingdom), and the number of E. coli O157:H7 cells in the homogenate was determined by using rainbow agar O157 plates (Table 1). E. coli O157:H7 was detected in the homogenate of the sections treated with HgCl2 for 4 or 10 min. These results indicated that E. coli O157:H7 was present in a viable form in the hypocotyl at a location that the surface disinfectant HgCl2 could not reach in 10 min.

Thus, all of the results demonstrated that E. coli O157:H7 was present not only on outer surfaces but also in inner tissues of cotyledons and in stomata when radish sprouts were raised from E. coli O157:H7-contaminated seeds; furthermore, HgCl2 treatment of the outer surfaces of cotyledons did not kill the bacteria. The viable E. coli O157:H7 found after HgCl2 treatment might have been bacteria that were present around the vessels and in the stomata of cotyledons. The ineffectiveness of disinfecting the outer surfaces of cotyledons indicates that using seeds free from E. coli O157:H7 in the production of radish sprouts or heating the sprouts to kill the bacteria is critical for preventing E. coli O157:H7 infections caused by eating raw radish sprouts.

Acknowledgments

We thank Yuichi Takikawa (Shizuoka University) for valuable and helpful comments.

REFERENCES

- 1.Andrews W H, Mislivec P B, Wilson C R, Bruce V R, Poelma P L, Gibson R, Trucksess M W, Young K. Microbial hazards associated with bean sprouting. J Assoc Off Anal Chem. 1982;65:241–248. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Beuchat L R. Comparison of chemical treatment to kill salmonella on alfalfa seeds destined for sprout production. Int J Food Microbiol. 1997;34:329–333. doi: 10.1016/s0168-1605(96)01202-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Como-Sabetti K, Reagan S, Allaire S, Parrott K, Simonds C M, Hrabowy S, Ritter B, Hall W, Altamirano J, Martin R, Downes F, Jennings G, Barrie R, Dorman M F, Keon N, Kucab M, Al Shab A, Robinson-Dunn B, Dietrich S, Moshur L, Reese L, Smith J, Wilcox K, Tilden J, Wojtala G, Park J D, Winnett M, Petrilack L, Vasquez L, Jenkins S, Barrett E, Linn M, Woolard D, Hackler R, Martin H, McWilliams D, Rouse B, Willis S, Rullan J, Miller G, Jr, Henderson S, Pearson J, Beers J, Davis R, Saunders D Food-Borne and Diarrheal Diseases Branch, Division of Bacterial and Mycotic Diseases, National Center for Infectious Diseases, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Outbreaks of Escherichia coli O157:H7 infection associated with eating alfalfa sprouts—Michigan and Virginia, June-July 1997. Morbid Mortal Weekly Rep. 1997;46:741–744. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hara-Kudo Y, Konuma H, Iwaki M, Kasuga F, Sugita-Konishi Y, Ito Y, Kumagai S. Potential hazard of radish sprouts as a vehicle of Escherichia coli O157:H7. J Food Prot. 1997;60:1125–1127. doi: 10.4315/0362-028X-60.9.1125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jaquette C B, Beuchat L R, Mahon B E. Efficacy of chlorine and heat treatment in killing Salmonella stanley inoculated onto alfalfa seeds and growth and survival of the pathogen during sprouting and storage. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1996;62:2212–2215. doi: 10.1128/aem.62.7.2212-2215.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Johnston A, Booth C, editors. Plant pathologist’s pocketbook. 2nd ed. Slough, United Kingdom: Commonwealth Agricultural Bureaux; 1983. pp. 30–45. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mahon B E, Pönkä A, Hall W N, Komatsu K, Dietrich S E, Siitonen A, Cage G, Hayes P S, Lambert-Fair M A, Bean N H, Griffin P M, Slutsker L. An international outbreak of salmonella infections caused by alfalfa sprouts grown from contaminated seeds. J Infect Dis. 1997;175:876–882. doi: 10.1086/513985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.National Institute of Infectious Diseases and Infectious Diseases Control Division, Ministry of Health and Welfare of Japan. Verocytotoxin-producing Escherichia coli (enterohemorrhagic E. coli) infection, Japan, 1996-June 1997. Infect Agents Surveillance Rep. 1997;18:153′–154′. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pönkä A, Andersson Y, Siitonen A, de Jong B, Jahkola M, Haikala O, Kuhmonen A, Pakksala P. Salmonella in alfalfa sprouts. Lancet. 1995;345:462–463. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(95)90451-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]