Dear Editor,

With great interest, we read the comprehensive systematic review by Shanika et al. [1] which highlights the high consumption of proton pump inhibitors (PPI) by about a quarter of the adults (23,4%) worldwide. In their conclusions, the authors stress the need for a rational use, better monitoring, and deprescribing where indications are lacking. We fully agree with these conclusions, but we would like to add the following aspect: the lack of PPI despite indication.

For Germany, high treatment prevalence has been reported [2], especially in patients with polypharmacy and multimorbidity. For the latter, Lappe et al. reported a treatment prevalence with PPI of 52% and a high mean amount of 442 defined daily doses (DDD) in 2019, indicating continuous treatment or high daily doses [3].

Despite high treatment prevalence with PPI, undersupply can be observed, especially when patients use, e.g., simultaneously NSAID and anticoagulants or glucocorticoids. The risk for gastrointestinal bleeding is increased compared to monotherapy with only one drug group [4]. To minimize the risk for gastric ulcer and stomach bleeding during treatment with these drugs, the prophylactic co-prescribing of PPI or other antiulcer drugs is recommended [5].

In order to investigate the extent of undersupply, we analyzed the data of one of the largest health insurance funds (BARMER) in Germany. The data was accessed via the scientific data warehouse. We focused on insured persons > 17 years of age without a diagnosis of malignant neoplasm (ICD-10 code C00-C97) and a simultaneous prescription of NSAID with (i) anticoagulants or antithrombotic agents (n = 82,756) and (ii) glucocorticoids (n = 41,319) over a period of at least 28 days in 2021. Drugs were classified according to the anatomical therapeutic chemical (ATC) classification.

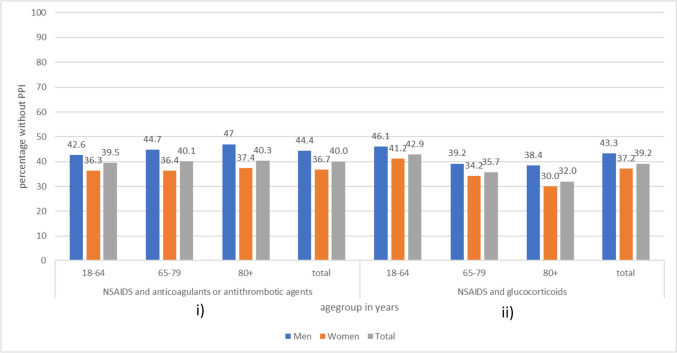

According to our data, 40.0% of those with a simultaneous treatment of NSAID with anticoagulants/antithrombotic agents had no co-prescribing of a PPI, and only 0.1% received other drugs for acid-related disorders (H2-receptor antagonists, misoprostol). A comparable amount of 39.2% did not receive an indicated PPI while using NSAID and glucocorticoids for a longer period of time. Women seem to be more likely to receive a PPI [6]. Age has a stronger influence on the co-prescribing of PPI in patients with glucocorticoids compared to the other combination of drugs (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Percentage of the study population without PPI by insured persons with NSAID and simultaneous use of i) anticoagulants/antithrombotic agents or ii) glucocorticoids. i) Men (n = 35,395); women (n = 47,361); total (n = 82,756). ii) Men, 13,336; women, 27,983; total, 41,319. Data: scientific data warehouse BARMER; study population: insured persons > 17 years of age without a diagnosis of malignant neoplasm; simultaneous use over 28 days

In addition to the examples mentioned, there are further constellations where indicated PPI prescribing should be checked [5]. The strength of the study lies in the database covering about 12% of all statutory health-insured persons in Germany (9 million persons). Limitations are the lack of information on over-the-counter drugs and individual reasons for the use or nonuse of a drug.

The high treatment prevalence of PPI and long application time underline the need for a regular medication review as expressed by Shanika et al. [1]. International guidelines for the management of multimedication [7, 8] offer various instruments for medication assessment such as the Medication Appropriateness Index (MAI) [9]. While the risk of drugs and overuse in patients are frequently addressed, the possible underuse, i.e., a lack of a drug despite given indication, is less aware [10]. The German evidence-based guideline on multimedication [8] included underuse into the MAI as a key question when reviewing medication. As we could demonstrate for PPI, there may also be an undersupply of a commonly used medicine.

Acknowledgements

Open Access funding was enabled by Project DEAL.

Authors contribution

IS, VL and DG designed the study, VL analyzed the data; IS wrote the manuscript, VL, UM and DG supervised the manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL. IS and VL received funding from the BARMER. UM is employed by the BARMER; DG received funding from the BARMER. The analysis was funded by the BARMER.

Data availability

Restrictions apply to the availability of these data. Data can be made available upon reasonable request and with permission of BARMER.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interest.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Shanika LGT, Reynolds A, Pattison S, Braund R (2023) Proton pump inhibitor use: systematic review of global trends and practices. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 79(9):1159–1172. 10.1007/s00228-023-03534-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 2.Rückert-Eheberg I-M, Nolde M, Ahn N, Tauscher M, Gerlach R, Güntner F, Günter A, Meisinger C, Linseisen J, Amann U et al (2022) Who gets prescriptions for proton pump inhibitors and why? A drug-utilization study with claims data in Bavaria, Germany, 2010–2018. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 78(4):657–667. 10.1007/s00228-021-03257-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 3.Lappe V, Dinh TS, Harder S, Brueckle M-S, Fessler J, Marschall U, Muth C, Schubert I, and on behalf of the EVITA Study Group Multimedication guidelines: assessment of the size of the target group for medication review and description of the frequency of their potential drug safety problems with routine data. Pharmacoepidemiology. 2022;1(1):12–25. doi: 10.3390/pharma1010002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Masclee GM, Valkhoff VE, Coloma PM, de Ridder M, Romio S, Schuemie MJ, Herings R, Gini R, Mazzaglia G, Picelli G et al (2014) Risk of upper gastrointestinal bleeding from different drug combinations. Gastroenterology 147(4):784–792.e789; quiz e713–784. 10.1053/j.gastro.2014.06.007 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.Grandt D, Gamstätter T (2021) S2k-Leitlinie Arzneimitteltherapie bei Multimorbidität – living guideline. https://register.awmf.org/assets/guidelines/100-001l_S2k_Arzneimitteltherapie-bei-Multimorbiditaet_2023-02.pdf. Accessed 27 Aug 2023

- 6.Grandt D, Lappe V, Schubert I (2023) Arzneimittelreport 2023: Medikamentöse Schmerztherapie nicht-onkologischer ambulanter Patientinnen und Patienten Berlin, BARMER (in print)

- 7.NICE Medicines and Prescribing Centre (UK) (2015) Medicines optimisation: the safe and effective use of medicines to enable the best possible outcomes. Manchester: National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng5/evidence/full-guideline-pdf-6775454. Accessed 30 Aug 2023 [PubMed]

- 8.Schubert I, Fessler J, Harder S, Dinh TS, Brueckle M-S, Muth C and on behalf of the EVITA Study Group Multimedication in family doctor practices: the German evidence-based guidelines on multimedication. Pharmacoepidemiology. 2022;1(1):35–48. doi: 10.3390/pharma1010005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hanlon JT, Schmader KE (2022) The medication appropriateness index: a clinimetric measure. Psychother Psychosom 91(2):78–83. 10.1159/000521699 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.Kuijpers MA, van Marum RJ, Egberts AC, Jansen PA (2008) Relationship between polypharmacy and underprescribing. Br J Clin Pharmacol 65(1):130–133. 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2007.02961.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Restrictions apply to the availability of these data. Data can be made available upon reasonable request and with permission of BARMER.