Abstract

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is a neurodegenerative disease with subtle onset, early diagnosis remains challenging. Accumulating evidence suggests that the emergence of retinal damage in AD precedes cognitive impairment, and may serve as a critical indicator for early diagnosis and disease progression. Salvianolic acid B (Sal B), a bioactive compound isolated from the traditional Chinese medicinal herb Salvia miltiorrhiza, has been shown promise in treating neurodegenerative diseases, such as AD and Parkinson’s disease. In this study we investigated the therapeutic effects of Sal B on retinopathy in early-stage AD. One-month-old transgenic mice carrying five familial AD mutations (5×FAD) were treated with Sal B (20 mg·kg−1·d−1, i.g.) for 3 months. At the end of treatment, retinal function and structure were assessed, cognitive function was evaluated in Morris water maze test. We showed that 4-month-old 5×FAD mice displayed distinct structural and functional deficits in the retinas, which were significantly ameliorated by Sal B treatment. In contrast, untreated, 4-month-old 5×FAD mice did not exhibit cognitive impairment compared to wild-type mice. In SH-SY5Y-APP751 cells, we demonstrated that Sal B (10 μM) significantly decreased BACE1 expression and sorting into the Golgi apparatus, thereby reducing Aβ generation by inhibiting the β-cleavage of APP. Moreover, we found that Sal B effectively attenuated microglial activation and the associated inflammatory cytokine release induced by Aβ plaque deposition in the retinas of 5×FAD mice. Taken together, our results demonstrate that functional impairments in the retina occur before cognitive decline, suggesting that the retina is a valuable reference for early diagnosis of AD. Sal B ameliorates retinal deficits by regulating APP processing and Aβ generation in early AD, which is a potential therapeutic intervention for early AD treatment.

Keywords: early Alzheimer’s disease, retinopathy, salvianolic acid B, BACE1, Aβ, proinflammatory cytokine

Introduction

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is a progressive neurodegenerative disorder characterized by cognitive decline. The hallmark pathological features of AD encompass amyloid-β (Aβ) plaque deposition and neurofibrillary tangles (NFTs) [1, 2], resulting in neuronal loss and altered synaptic connections [3]. Clinical evidence indicates that Aβ accumulation, stemming from an imbalance between production and clearance, is among the earliest and initial events leading to AD [4–6]. The buildup of Aβ triggers microglial activation and inflammation, initiating an inflammatory cascade response that exacerbates neurodegeneration [2]. Diagnosing AD remains challenging, with clinical diagnoses typically relying on low-accuracy neuropsychological tests and expensive neuroimaging examinations. Consequently, a significant proportion of patients with AD experience delayed diagnosis [7, 8]. Early diagnosis is critical for the treatment of AD as interventions following the onset of clinical symptoms demonstrate limited impact on preventing or reversing disease progression [9]. Recent studies have demonstrated that early diagnosis could reduce the severity of AD by one-third [10, 11]. Therefore, preclinical diagnosis of AD is essential, as early intervention can significantly reduce disease severity. Identifying reliable and cost-effective diagnostic methods for early AD detection remains a vital area of interest for the medical community.

Long thought to be limited to the brain, the onset of AD also affects the retina, a component of the central nervous system (CNS), according to recent evidence. Histological examinations and noninvasive retinal imaging techniques have revealed that AD progression leads to significant alterations in retinal structure and function [12, 13]. Some studies have demonstrated that visual problems may manifest before AD-related cognitive impairment [14–17]. Signs of retinal degeneration in AD patients include axonal degeneration of the optic nerve head [2], a reduced number of retinal ganglion cells (RGCs) [18, 19], and thinning of the retinal nerve fiber layer (RNFL) [20, 21]. These retinal changes have also been observed in commonly used AD mouse models, such as 5×FAD [22, 23], APP/PS1 [24–26], 3×Tg [27, 28], and Tg2576 [29].

Given the shared embryonic origin, vascular system, and cellular and molecular mechanisms of neurodegeneration between the retina and brain, changes in the retina may serve as an indicator of pathological processes occurring elsewhere in the CNS [30–32]. The retina is also becoming an attractive diagnostic tool for AD because state-of-the-art ocular imaging techniques, such as optical coherence tomography and confocal scanning laser ophthalmoscopy, enable the visualization of retinal changes at a higher resolution and in a more reproducible and quantifiable manner than conventional brain imaging techniques, without requiring invasive or expensive procedures [33, 34]. Despite growing interest in the pathological mechanisms of retinal damage in Alzheimer’s disease, only a handful of studies have delved into this topic in depth [35–37].

Herbs and medicinal plants have a rich history of use as sources of bioactive molecules with therapeutic potential. In recent decades, nearly half of the FDA-approved drugs have been derived from natural products [38]. There is growing evidence that herbal medicines may be effective in treating neurodegenerative diseases, including AD [39, 40]. Salvianolic acid B (Sal B), a major bioactive compound found in the traditional Chinese medicinal herb Salvia miltiorrhiza, has demonstrated promise in treating neurological disorders, such as AD [41, 42], depression [43–45], and Parkinson’s disease [46, 47]. Sal B has been shown to exhibit neuroprotective properties through its antioxidant and anti-inflammatory effects [41, 45, 48–50], reduced Aβ accumulation and Aβ-induced neuronal toxicity [51, 52], and improved cognitive function in AD mouse models [41]. Furthermore, Sal B can cross the blood-brain barrier [53], making it a direct candidate for AD treatment. We hypothesized that Sal B may ameliorate retinal damage in AD mouse models.

In this study, we demonstrate that the retina is a key reference indicator for the early diagnosis of AD, as functional impairment of the retina occurs earlier than that of the brain. Furthermore, our findings indicate that Sal B has therapeutic potential in AD. By reducing the expression of BACE1 and sorting into the Golgi apparatus, Sal B was found to reduce Aβ generation in the retina of 4-month-old 5×FAD mice. This reduction in amyloid plaque burden also leads to a decreased release of pro-inflammatory cytokines, resulting in improved retinopathy in AD. Our results underscore the pivotal role of Aβ accumulation in neurodegenerative retinal dysfunction and suggest the potential of Sal B as a therapeutic intervention for early-stage AD.

Materials and methods

Animals and pharmacological treatments

Transgenic mice carrying five familial Alzheimer’s disease (5×FAD) mutations were obtained from Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME, USA). All animal experiments were conducted in accordance with the relevant ethical regulations for animal testing and approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) of Xiamen University (ethical approval number XMULAC20200048). The experiments adhered to the guidelines of the Association for Research in Vision and Ophthalmology (ARVO). Notably, we used the 5×FAD mouse model, specifically the MMRRC_034848-JAX strain, which does not carry the Pde6brd1 mutation associated with retinal degeneration. Sal B was procured from Chengdu Herbpurify Co. Ltd. (121521-90-2, Chengdu, China) and prepared in 0.9% saline. One-month-old mice were intragastrically (i.g.) administered Sal B at a dose of 20 mg·kg−1·d−1 for three months. The treatment was administered once daily. Retinal function and structure were assessed during the treatment. All experiments were conducted and analyzed in a double-blind manner, and all collected data are presented in the Appendix or Supplementary figure. Equal proportions of male and female mice were used in the present study.

Morris water maze test

The Morris Water Maze (MWM) test was conducted using a circular tank with a diameter of 120 cm filled with opaque water maintained at a temperature of 22 °C. Reference cues were provided in the form of four bright and contrasting shapes affixed to tank walls. A platform with a diameter of 10 cm was submerged 1 cm below the water surface in a designated quadrant, which served as the target. Mice were placed in the maze at one of four randomly selected points and subjected to two trials per day for seven consecutive days. During each trial, the mice were given 90 s to locate the hidden platform. If a mouse failed to find the platform within the allotted time, it was gently guided to the platform and kept there for an additional 15 s. The latency to reach the platform was recorded using Smart Video Tracking Software 3.0 (Panlab, Harvard Apparatus). On the eighth day after training, a probe test was performed in which the platform was removed and the time spent in each quadrant was recorded.

T-maze test

In the T-maze test, the mice were placed in the center of a T-maze consisting of three arms. Mice were then allowed to freely explore their arms for 10 min. The percentage of spontaneous alternation was calculated using the Smart Video Tracking Software (version 3.0; Panlab, Harvard Apparatus, Holliston, MA, USA). The software provides an automated calculation of the percentage of spontaneous alternations.

Open field test

In the open field test, the behavior of each mouse was characterized in an open field box measuring 60 cm × 60 cm × 60 cm. The total distance traveled was monitored to evaluate motor activity, and the time and distance spent in the central and peripheral areas of the open field were calculated using the Smart Video Tracking Software (version 3.0; Panlab, Harvard Apparatus, Holliston, MA, USA).

Electroretinography

Electroretinographic (ERG) analysis was conducted using a previously established method [54]. After at least 12 h of dark adaptation, standard photostimulation ERG was recorded simultaneously from both eyes of the mice (Espion E2; Diagnosys LLC, Cambridge, UK). Mice were anesthetized by isoflurane (RWD, R510-22-10) inhalation [6], and their pupils were fully dilated with compound tropicamide eye drops (Yongguang Pharmaceutical, China). The recording procedures were performed under dim red light. Single flash recordings were obtained at increasing light intensities, ranging from 0.01 to 10 cd·s/m2, and ten responses per intensity level were averaged over a 60 s interstimulus interval. Photopic and cone-mediated responses were recorded after 30 min of light adaptation to a background light intensity of 30 cd/m2, using light intensities of 30 and 100 cd·s/m2. Fifteen waveforms were recorded for each animal and the values were averaged. The amplitudes of the ERG a-wave were measured from baseline to the negative trough, and the amplitudes of the b-wave were measured from the trough of the a-wave to the peak of the first positive wave or, in the absence of the a-wave, from the baseline to the peak of the first positive wave.

Photopic negative response

Evaluation of retinal ganglion cell (RGC) and axon function was performed using Photopic Negative Response (PhNR) recordings. The recordings were conducted at a light intensity of 20 cd·s/m2 and frequency of 1 Hz. The procedure involved collecting 100 waveforms from each mouse and averaging the results. The amplitude of the PhNR was measured from the baseline to the negative peak following the b-wave.

Optical coherence tomography

Optical Coherence Tomography (OCT) was performed using a 4D-ISOCT instrument (OPTOPROBE, UK) to evaluate structural changes in the retina [19]. During the imaging procedures, the mice were placed on a heating pad to maintain their body temperature, and a physiological saline was applied to the eye surface to prevent dehydration during anesthesia. The images were captured as TIFF stacks and quantified using the ImageJ software (NIH). The retinal layer scanned by OCT was manually divided into two components: the ganglion cell layer (GCL), the inner plexiform layer (IPL), and the total retinal thickness.

Cell culture and transfection

Human embryonic kidney 293 T cells were cultured in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) under standard cell culture conditions (37 °C, 5% CO2). The human neuroblastoma SH-SY5Y cell line stably overexpressing APP751 (SH-SY5Y-APP751) was maintained in DMEM (Thermo Fisher Scientific, C11995500BT) containing 10% FBS (Thermo Fisher Scientific, 10270-106) and 200 μg/mL G418 (Thermo Fisher Scientific, 10131027) as a selection marker. The cells were cultured in a humidified incubator at 37 °C and 5% CO2. For DNA construct transfection, cells were transfected using TurboFect Transfection Reagent (Thermo Fisher Scientific, R0534) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. For siRNA transfection, the siRNAs were provided by RiboBio (Guangzhou, China) and the target sequences for BACE1 siRNA were as follows: siBACE1-1, 5′-GAGTACAATCTCTTGAATTGTACTCCTTGCAGTCCA-3′ and siBACE1-2, 5′- ATGGATTTGACTGCAGCGGGGATCTGTGGTCTCATA-3′. Lipofectamine RNAiMAX Transfection Reagent (13778100; Thermo Fisher Scientific) was used according to the manufacturer’s instructions. All transfections were performed using appropriate controls to ensure efficiency and specificity of the experiments.

Primary retinal cell isolation and culture

Primary retinal cell cultures were obtained by carefully dissecting the retinas from postnatal day 0 (P0) mice under aseptic conditions. Dissected retinas were enzymatically dissociated using papain (20 U/mL; Worthington Biochemical Corporation, LS003126) for 30 min at 37 °C, followed by mechanical trituration using a fire-polished Pasteur pipette. Dissociated retinal cells were resuspended in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium/Nutrient Mixture F-12 (DMEM/F12; Thermo Fisher Scientific, 11320033), supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; Gibco, 10099141), 100 U/mL penicillin, and 100 µg/mL streptomycin (Gibco, 15140122). The cells were plated on poly-d-lysine (Sigma-Aldrich, P7280)-coated coverslips at a density of 2 × 105 cells/cm2 and maintained in a humidified incubator at 37 °C with 5% CO2. The culture medium was replaced every three days, and retinal cells were allowed to grow for up to 14 days in vitro before further experimentation.

Transmission electron microscopy

Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) was used to investigate the ultrastructure of RGCs and their axons in 5×FAD mice. Mice were anesthetized with isoflurane and subjected to intracardial perfusion with PBS before fixation with a mixture of 4% paraformaldehyde and 2.5% glutaraldehyde. The optic disc and optic nerve tissues were rapidly dissected, post-fixed overnight in a fixative at 4 °C, and treated with 1% osmium tetroxide (Sigma-Aldrich, 75632) for 2 h at 4 °C. The samples were then dehydrated in an ethanol gradient (Sigma-Aldrich, E7023) ranging from 30% to 100% and embedded in Spurr resin (Electron Microscopy Sciences, 14300). Serial ultrathin sections were stained with lead citrate (Sigma-Aldrich, 15326) and uranyl acetate (Electron Microscopy Sciences, 22400) and images were captured using a Hitachi HT-7800 transmission electron microscope (JEM2100HC; Jeol Ltd., Tokyo, Japan). RGC body size and axonal myelin sheath thickness were quantified using ImageJ software (NIH) by a researcher blinded to the animal genotypes. RGCs in the ganglion cell layer (GCL) are characterized by distinct morphological features, including prominent nuclei and nucleoli. RGCs are typically larger than other cell types in this layer and are often surrounded by satellite glial cells.

Immunocytochemistry

Immunocytochemistry was performed according to previously established protocols [55]. Transfection was carried out on cells using anti-HA (Sigma Aldrich, H6908) and anti-Aβ (6E10) (BioLegend, 803001) antibodies. Confocal images were obtained using a Leica SP8 confocal microscope, and quantification was performed using the ImageJ software (NIH).

Immunohistochemistry

Immunohistochemistry was performed according to previously established protocols [55]. BACE1-HA and APP-EGFP plasmids were transfected into the cells. The cells were then stained with anti-HA (Sigma-Aldrich, H6908), anti-GFP (ThermoFisher, MA5-15256) and anti-RCAS1 (Cell Signaling Technology, 12290) antibodies. Confocal images were obtained using a Leica SP8 confocal microscope, and quantification was performed using ImageJ software (NIH). Each antibody was diluted at 1:500. Alexa Fluor 488- and Alexa Fluor 594-conjugated secondary antibodies (1:500, A11001, A11005, A11008, or A11012) were used to visualize the staining, and the slices were counterstained with 4’,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (C1005, DAPI, Beyotime). Z-stack confocal images were acquired using a Nikon A1R confocal microscope. Image analysis was performed using ImageJ software (NIH) for the manual counting of Iba1+ cells. The somatic size of microglia was analyzed by acquiring z-stack images from slices immunostained with anti-Iba1 antibodies, followed by reconstruction of microglial volumes using the Surfaces function in the Imaris software (version 9.2.0, Bitplane, Belfast, UK) and the filament function of the Imaris software for analysis of Iba1+ cell branching.

TUNEL assay

Terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase dUTP nick end labeling (TUNEL) assay was performed according to the manufacturer’s protocol (MA0223, Meilunbio, China). The sections were thoroughly washed four times with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) for 10 min per wash. The nuclei were counterstained with DAPI to visualize cell morphology. Representative images were acquired using a Nikon A1R confocal microscope (Tokyo, Japan).

Hematoxylin-Eosin (HE) staining

Mice were anesthetized using an overdose of isoflurane, followed by perfusion through the aorta with 100 ml of PBS and then with 100 ml of phosphate buffer containing 4% paraformaldehyde. The eyes were then removed, embedded in OCT compound (tissue-freezing medium, Sakura, USA), and cut into 10 μm sections. These sections were consecutively collected in PBS for HE staining according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Solarbio, China). Images were captured using a digital microscope scanning system (Leica Aperio Versa 200, Germany).

RNA isolation and quantitative reverse transcription PCR

Quantitative reverse transcription PCR (qRT-PCR) was performed as previously described [55]. The primer sequences for the target genes are listed in Supplementary Table S1.

Immunoblot analysis

To assess alterations in protein expression in cells and tissues, we conducted Western blot analysis following established protocol [56–58]. Cells were harvested and lysed in radioimmunoprecipitation assay (RIPA) buffer (Sigma-Aldrich, R0278) containing protease and phosphatase inhibitors (Roche, 11873580001 and 04906837001). Tissues were homogenized in lysis buffer before centrifugation to collect supernatants. Protein concentrations were determined using the BCA Protein Assay Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, 23225). Equal amounts of protein samples were subjected to SDS-PAGE (Bio-Rad, 4561034) and transferred onto PVDF membranes (Millipore, IPVH00010). The membranes were blocked with 5% non-fat milk (Bio-Rad, 1706404XTU) in TBS-Tween (Sigma-Aldrich, P1379) and incubated overnight at 4 °C with primary antibodies against anti-BACE1 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, 33711), anti-Aβ (B-4) (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, 28365), anti-sAPPβ (BioLegend, 813401), anti-Na/K ATPase (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, sc-21712), anti-GAPDH (Sangon Biotech, D190090), anti-PS1-NTF (Arigo Biolaboratories, ARG43011), anti-sAPPα (IBL International, 11088), anti-ADAM10 (abcam, ab124695), anti-NLRP3 (proteintech, 27458-1-AP), anti-IL-1β (Santa cruz, sc-12742), and anti-caspase-1 (D-3) (Santa Cruz, sc-392736). Following incubation with HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies (Jackson ImmunoResearch, 111-035-144 and 115-035-166, and MultiSciences, GAR007), protein bands were visualized using SuperSignal West Pico PLUS Chemiluminescent Substrate (Thermo Fisher Scientific, 34580) or enhanced chemiluminescence (Meilunbio, MA0186), and captured with a Tanon Gel Imager. ImageJ software (NIH) was used to analyze and quantify the band intensities. All experiments were performed in triplicates to ensure data reliability and reproducibility.

Cell surface biotinylation assay

Cells were subjected to a cell surface biotinylation assay as previously described [59], with minor modifications. Briefly, cells were washed twice with ice-cold phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) to remove any residual culture medium. After washing, cells were incubated for 50 min at 4 °C with freshly prepared ice-cold biotinylation buffer containing 0.5 mg/mL EZ-Link Sulfo-NHS-SS-Biotin (Thermo Fisher Scientific, 21331) in PBS. The biotinylation reaction was quenched by washing the cells twice with a 100 mM glycine solution in PBS, followed by a final wash with ice-cold PBS. The cells were then lysed and biotinylated proteins were isolated using NeutrAvidin Agarose Resin (Thermo Fisher Scientific, 29201) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The eluted biotinylated proteins were analyzed using Western blotting to assess the expression of cell surface proteins.

Pharmacological inhibitors treatment

Lysosomal protein degradation was inhibited by adding 100 μg/mL leupeptin (MCE, HY-18234A). Proteasomal protein degradation was inhibited by addition of MG132 (MCE, HY-13259) at a final concentration of 10 μM.

Long-term potentiation (LTP) recording

Electrophysiological experiments were performed as previously described [56, 57]. Mice were anesthetized using isoflurane, and their brains were promptly extracted and placed in ice-cold artificial cerebrospinal fluid (ACSF; consisting of 120 mM sucrose, 2.5 mM KCl, 10 mM MgSO4, 1.25 mM NaH2PO4, 26 mM NaHCO3, 10 mM D-glucose, 64 mM NaCl, and 0.5 mM CaCl2, with a pH of 7.4 and an osmolarity of ~310 mOsm), bubbled with carbogen (95% O2 + 5% CO2). Brain slices (400 μm thick) were prepared using a Leica VT1200S vibratome, incubated in ACSF (consisting of 3.5 mM KCl, 120 mM NaCl, 1.3 mM MgSO4, 10 mM D-glucose, 1.25 mM NaH2PO4, 26 mM NaHCO3, and 2.5 mM CaCl2, with a pH of 7.4 and an osmolarity of ~300 mOsm), and bubbled with carbogen (95% O2 + 5% CO2) at 32 °C for 1 h. The slices were allowed to recover at room temperature for at least 1 h prior to recording. For the induction of long-term potentiation (LTP), the Schaffer collateral inputs into the CA1 region were stimulated using a bipolar tungsten electrical stimulation electrode, and field excitatory postsynaptic potentials (fEPSPs) were recorded from the dendritic layer of the Schaffer collateral pathway. Baseline responses were obtained every 20 s using a stimulation intensity that produced 30% of the maximum response, and were recorded using a Multi-Clamp 700 B amplifier (Molecular Devices), Clampex10.5 acquisition software (Molecular Devices), and Digidata 1550 A (Molecular Devices), with glass pipettes (1–3 MΩ) filled with ACSF. The test stimuli consisted of monophasic 0.1 ms pulses of constant currents (adjusted to produce 25% of the maximum response) at a frequency of 0.05 Hz. After a 20-min stable baseline recording, LTP was induced by high-frequency stimulation (two trains of 100 Hz stimuli, with an interval of 30 s), followed by continued recording for 60 min.

Retinal staining

Retinas from adult C57BL/6 mice were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) for 2 h, permeabilized with 1% Triton X-100 in PBS, and blocked with 0.2% bovine serum albumin (BSA). Primary antibodies, such as rabbit anti-iba1 antibody (Wako Pure Chemical, 019-19741), diluted in 1% Triton X-100 in PBS, were incubated overnight at 4 °C. The retinas were then incubated with secondary antibodies conjugated to Alexa Fluor 488 or Alexa Fluor 594 (Thermo Fisher Scientific) diluted in 1% BSA for 1 h at room temperature. After staining with DAPI and washing with PBS, retinas were mounted on glass slides for a four-leaf clover cutting and imaged using a fluorescence microscope (BX53; Olympus).

DNA constructs

Primer sequences for constructing the BACE1 plasmid or point mutations were designed. The required DNA fragment can be extracted from an existing BACE1 plasmid or amplified from BACE1. The amplified DNA fragments were subjected to enzymatic digestion and ligated into a vector plasmid (pCDNA3.1-HA/His). The ligated plasmid was subsequently transformed into Escherichia coli for screening and purification. For point mutations, PCR amplification was employed to introduce the desired nucleotide changes into the primers, followed by enzymatic digestion and ligation. Commonly used enzymes include T4 DNA ligase (M0202S; NEB). Finally, the constructed BACE1 plasmids or point mutations were sequenced to confirm their accuracy.

Protein structure prediction and molecular docking analysis

The structures of human BACE1 and mouse BACE1 were predicted using AlphaFold2, a deep neural network-based protein structure prediction algorithm developed by DeepMind. The sequences were submitted to the official AlphaFold2 website (https://alphafold.ebi.ac.uk/) and the predicted structures were downloaded. For docking, simple structures of human BACE1 and mouse BACE1 were predicted using AlphaFold2, a deep neural network-based protein structure prediction algorithm developed using DeepMind relations. AutoDock Vina, a widely used molecular docking software package, was used in this study. The structure of Sal B was obtained from the PDB database (https://www.rcsb.org/) and converted to PDBQT format using Open Babel software. Docking simulations were performed using default parameters, incorporating considerations of hydrogen bonding, van der Waals forces, and electrostatic interactions, among other factors. Furthermore, molecular dynamics simulations were carried out using Amber 20 software to obtain the stable binding conformations of BACE1 and Sal B.

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed using the GraphPad Prism software (version 9). A comprehensive description of the statistical methods applied, including one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post-hoc analysis, one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s post-hoc analysis, repeated-measures ANOVA with Bonferroni’s post-hoc analysis, and Student’s t-tests, is provided in the figure legends. The results are presented as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM), and the significance level was set at P < 0.05.

Results

Sal B restored retinal functional parameters in the early stage of 5×FAD mice

To establish the appropriate dose for treatment, we administered different doses of Sal B to 5×FAD mice, including 10, 20, and 40 mg·kg−1·d−1, based on our previous research and relevant literature [45, 48]. We carried out an in-depth examination of the activation of retinal microglial cells and deposition of Aβ plaques to evaluate the effectiveness of each administered dose. Our findings indicated that a modest improvement was observed at the 10 mg·kg−1·d−1 dose (Supplementary Fig. 1a–f), whereas more pronounced ameliorative effects were noted at the 20 and 40 mg·kg−1·d−1 doses (Supplementary Fig. 1a–f). Considering the safety and efficacy of these doses, we opted for a lower effective dose of 20 mg·kg−1·d−1 in subsequent studies.

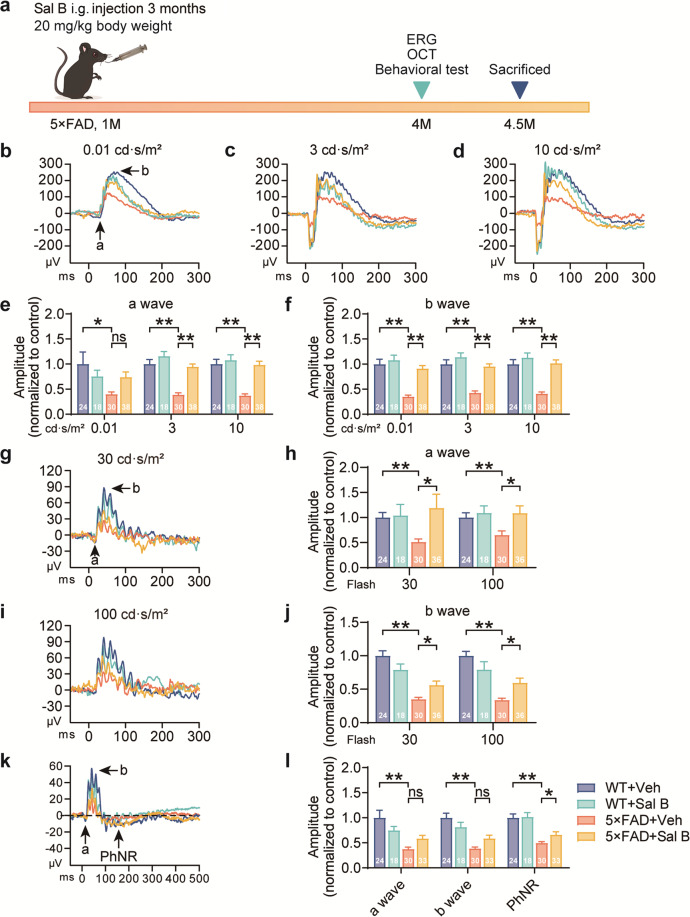

To investigate the impact of Sal B on retinal functional and structural impairments in Alzheimer’s disease, we administered Sal B (20 mg·kg−1·d−1) to 1-month-old 5×FAD mice for 3 months (Fig. 1a). Electroretinography was employed to evaluate retinal function by assessing various parameters, including dark adaptation, light adaptation, and photopic negative response (PhNR). Our results revealed that, at 4 months of age, the amplitudes of the a- and b-waves triggered by retinal photoreceptor cell activation were decreased in 5×FAD mice compared to wild-type mice during both dark adaptations (Fig. 1b–f) and light adaptation at 30 and 100 cd·s/m2 (Fig. 1g–j). Furthermore, a significant reduction in PhNR amplitude was observed in 4-month-old 5×FAD mice (Fig. 1k, l). After 3 months of Sal B administration, the amplitudes of PhNR, dark adaptation, and light adaptation were significantly increased in 5×FAD mice.

Fig. 1. Sal B restored the function of the retina in 4-month-old 5×FAD mice.

a Timeline of Sal B administration. The four treatment groups in this study were as follows: WT + Veh, WT + Sal B, 5×FAD + Veh, and 5×FAD + Sal B. One-month-old mice were intragastrically (i.g.) administered vehicle or Sal B (20 mg·kg−1·d−1) for 3 months and subsequently subjected to ERG and pathological analyses. b–f Comparison of a-wave (e) and b-wave (f) amplitudes at 3 different light intensities (0.01, 3, and 10 cd·s/m2, b–d) in WT + Veh, WT + Sal B, 5×FAD + Veh, and 5×FAD + Sal B mice at 4 months of age. n = 18 to 38 per group. g–j Comparison of the a-wave (h) and b-wave (j) amplitudes at two different single-flash intensities (30 and 100 cd·s/m2, g, i) in WT + Veh, WT + Sal B, 5×FAD + Veh, and 5×FAD + Sal B mice at 4 months of age. n = 18 to 36 per group. k, l Comparison of the a-wave, b-wave, and PhNR in WT + Veh, WT + Sal B, 5×FAD + Veh, and 5×FAD + Sal B mice at 4 months of age. n = 18 to 33 per group (one of the mice had only a left eye). All data are represented as the mean ± SEM. P-values were determined by one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc analysis in (e) and (f), (h), (j), and (l). ns, not significant. *P < 0.05 **P < 0.01.

Retinal functional impairments precede cognitive decline in early-stage 5×FAD mice

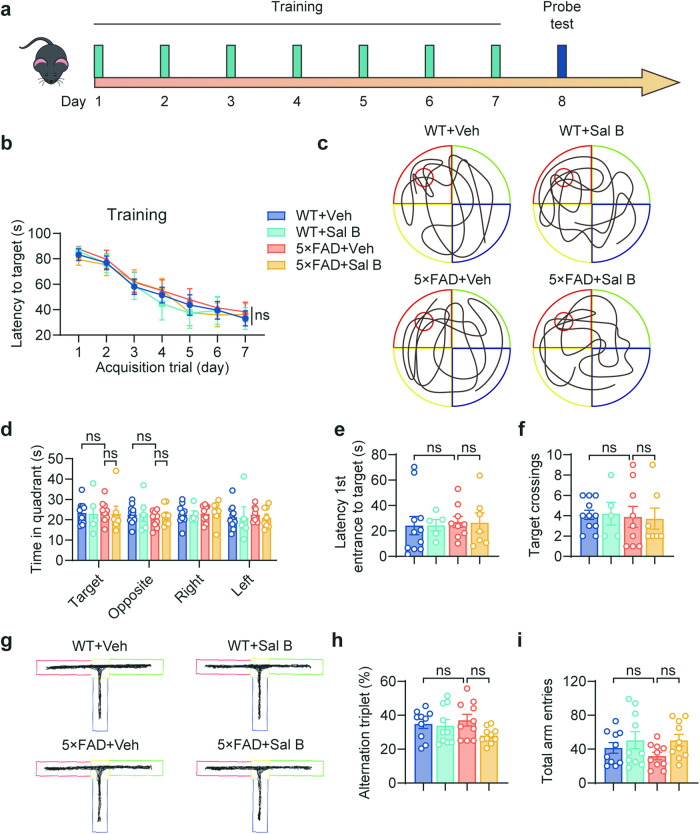

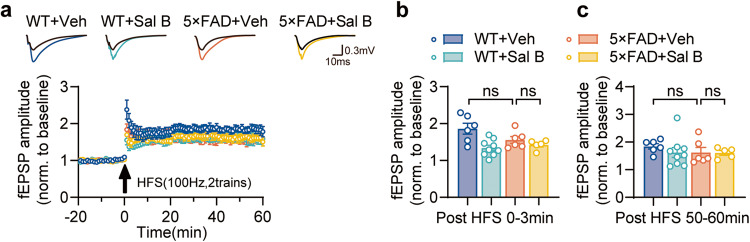

To evaluate cognitive function in 4-month-old 5×FAD mice, we assessed their learning and memory abilities using the Morris water maze (MWM) task (Fig. 2a–f, Supplementary Fig. 2a–c), and the T-maze tasks (Fig. 2g–i). These results indicate no cognitive impairment in the 4-month-old 5×FAD mice. Similarly, motor function and anxiety behavior were normal, as determined by the open-field behavior test (Supplementary Fig. 3a–f). Moreover, we conducted long-term potentiation (LTP) experiments in Schaffer collaterals and found no alterations in synaptic plasticity (Fig. 3a–c). These findings confirm that functional impairments in the retina occur before cognitive decline, suggesting that the retina is a valuable reference for early diagnosis of AD.

Fig. 2. Learning and memory impairment were not detected in 4-month-old 5×FAD mice.

a Timeline of the MWM experimental process. b MWM test results depicting escape latency in training. c Representative trace in the MWM test. d–f MWM probe test results depicting time in quadrant (d), latency 1st entrance to target (e), target crossings (f). n = 5 to 11 per group. g Representative trace in the T-maze. h, i T-maze test results depicting the percentage of alternation triplet (h) and the total arm entries (i). n = 10 per group. All data are represented as the mean ± SEM. P-values were determined by repeated measures ANOVA with Bonferroni’s post hoc analysis in (b), by one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc analysis in (d), and by one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s post hoc analysis in (e) and (f), (h) and (i). ns not significant.

Fig. 3. No detectable LTP deficit in the Schaffer collateral (SC)-CA1 pathway was observed in 4-month-old 5×FAD mice hippocampus.

a LTP recordings: LTP at the SC-CA1 synapses from WT + Veh, WT + Sal B, 5×FAD + Veh, and 5×FAD + Sal B mice at 4 months of age. HFS, high-frequency stimulation. Horizontal scale bar, 10 ms; vertical scale bar, 0.3 mV. b Results of LTP statistics: fEPSP amplitude quantification during the first 3 min of LTP recording. c Results of LTP statistics: fEPSP amplitude quantification during the last 10 min of LTP recording. n = 5 to 9 per group. All data are represented as the mean ± SEM. P values were determined by one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s post hoc analysis in (b) and (c). ns not significant.

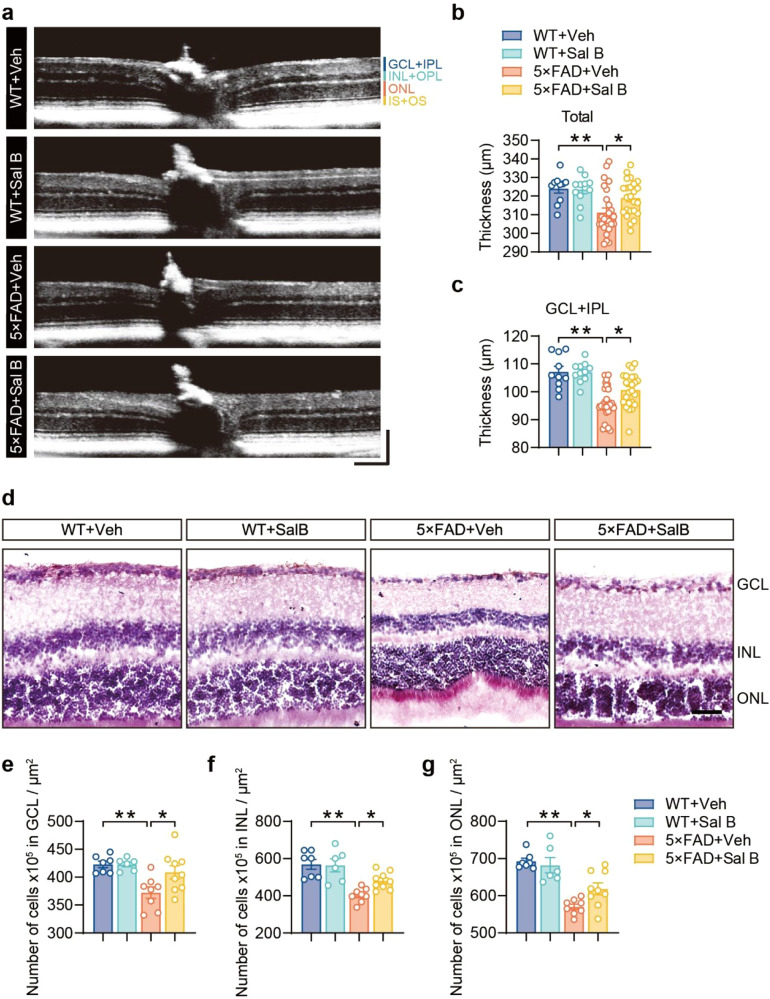

Sal B restored retinal structural changes in the early-stage 5×FAD mice

To evaluate the impact of 5×FAD on the retinal structure, we used optical coherence tomography (OCT) to scan the retinas of both 5×FAD and WT mice. The retinal layers were segmented for analysis. Our results indicated that the total retinal thickness and the thickness of the ganglion cell layer plus the inner plexiform layer (GCL + IPL) were reduced in 5×FAD mice compared to WT mice; however, three months of Sal B administration restored retinal thickness (Fig. 4a–c). The number of cells in the GCL, INL, and ONL was also significantly reduced in 5×FAD mice and restored following Sal B administration (Fig. 4d–g). These results demonstrate that Sal B effectively restored both retinal structure and function in 5×FAD mice.

Fig. 4. Sal B restored the impairment of retinal structure in 4-month-old 5×FAD mice.

a–c Representative images of the thickness of different retinal layers at 4 months of age in WT + Veh, WT + Sal B, 5×FAD + Veh, and 5×FAD + Sal B mice based on in vivo OCT volume scans (a). Horizontal scale bar, 130 μm; vertical scale bar, 150 μm. Thickness values of the total retina (b) and thickness values of the GCL + IPL (c). n = 10 to 26 per group. d–g Representative images of HE staining of the retina of WT + Veh, WT + Sal B, 5×FAD + Veh, and 5×FAD + Sal B mice (d) at 4 months of age. Scale bar, 100 μm. Number of cells in GCL (e), INL (f), ONL (g). n = 6 to 9 per group. All data are represented as the mean ± SEM. P-values were determined by one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s post hoc analysis in (b) and (c), and (e) to (g). *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01.

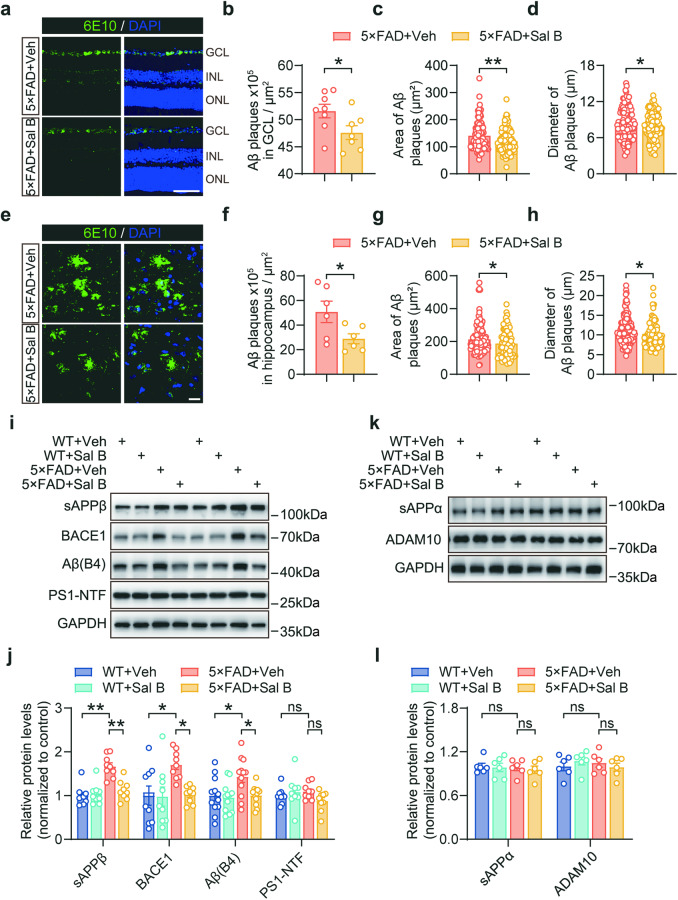

Sal B ameliorated amyloid pathology in the retina of 5×FAD mice

To investigate the effect of Sal B on amyloid pathology in 5×FAD mice, 6E10 antibody staining was used. Our findings demonstrated that Sal B treatment led to a reduction in both the number and size of amyloid plaques in the retinas of the 5×FAD mice (Fig. 5a–d). We also observed that Aβ deposition was primarily concentrated in the GCL and largely absent in the other retinal layers (Fig. 5a). Moreover, we noted an improvement in Aβ plaque deposition in the hippocampus of 5×FAD mice following Sal B treatment (Fig. 5e–h).

Fig. 5. Sal B reduced BACE1 expression and ameliorated Aβ deposition.

a Representative confocal images showing 6E10+ amyloid plaques (green) in the retina of WT + Veh, WT + Sal B, 5×FAD + Veh, and 5×FAD + Sal B mice at 4 months of age. Scale bar, 75 μm. b–d Histological quantification of the number (b), area (c), and diameter (d) of amyloid plaques in the retina of 5×FAD + Veh and 5×FAD + Sal B mice. n = 7 to 8 per group (b); n = 105 to 132 per group (c, d). e Representative confocal images showing 6E10+ amyloid plaques (green) in the hippocampus of 5×FAD + Veh and 5×FAD + Sal B mice at 4 months of age. Scale bar, 20 μm. f–h Histological quantification of the number (f), area (g), and diameter (h) of amyloid plaques in the hippocampus of 5×FAD + Veh and 5×FAD + Sal B mice. n = 6 per group (f); n = 74 to 121 per group (g, h). i–l Immunoblot analysis of proteins related to APP processing in the retina of WT + Veh, WT + Sal B, 5×FAD + Veh, and 5×FAD + Sal B mice at 4 months of age. n = 6 to 9 per group. All data are represented as the mean ± SEM. P-values were determined by Student’s t-test in (b–d), and (f–h), and by one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc analysis in (j) and (l). ns not significant. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01.

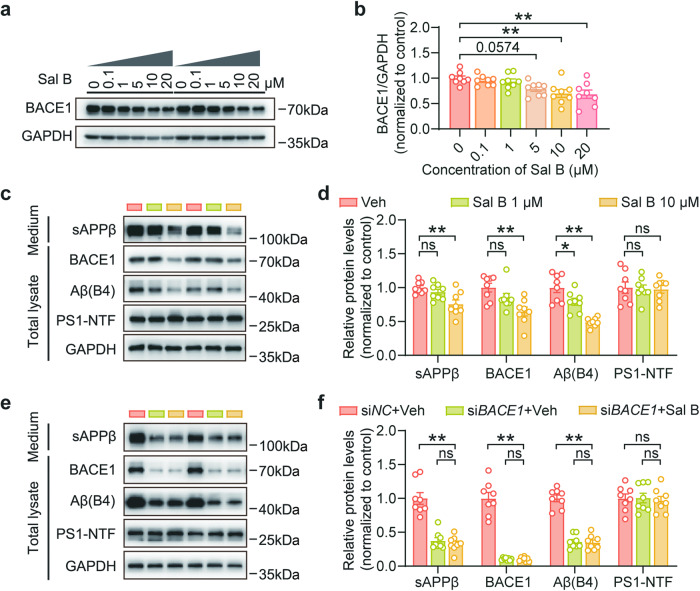

To gain a deeper understanding of the underlying mechanisms, we examined the expression of various proteolytic markers involved in APP processing, including BACE1, sAPPβ, and Aβ. Our data revealed that Sal B treatment decreases the expression of these markers in the retina (Fig. 5i, j). We further investigated the potential impact of Sal B on α-secretase-related pathways and found that Sal B did not exert a significant influence on these pathways (Fig. 5k, l). Taken together, our findings suggest that Sal B reduces Aβ production primarily through inhibition of β-secretase function. To confirm these findings, we conducted in vitro experiments using SH-SY5Y-APP751 cells and found that Sal B reduced BACE1 expression in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 6a, b). Additionally, Sal B treatment resulted in a significant decrease in the expression of BACE1, sAPPβ, and Aβ in SH-SY5Y-APP751 cells (Fig. 6c, d). Furthermore, we validated these findings in primary retinal neurons and obtained results consistent with those in SH-SY5Y-APP751 cells (Supplementary Fig. 4a, b). We treated SH-SY5Y-APP751 cells with siBACE1, and subsequently administered Sal B. Our data revealed that siBACE1 notably lowered Aβ production; however, treatment with Sal B did not lead to a further reduction in Aβ production (Fig. 6e, f). Collectively, our data provide evidence that Sal B primarily reduces Aβ-related pathology through the BACE1 pathway.

Fig. 6. Sal B mitigates Aβ deposition via BACE1 inhibition.

a, b Immunoblot assessment of BACE1 protein levels in SH-SY5Y-APP751 following Sal B administration at varying concentrations for a duration of 48 h. n = 8 per group. c, d Immunoblot examination of APP processing-associated proteins in SH-SY5Y-APP751 cells after Sal B treatment for 48 h. n = 8 per group. e, f Following transfection of SH-SY5Y-APP751 cells with siBACE1 or siNC for 72 h, the processing of APP and associated proteins was assessed by immunoblotting, subsequent to a 48 h treatment with either Sal B or the control vehicle. n = 8 per group. All data are depicted as the mean ± SEM. P-values were determined by one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc analysis in (b), (d), and (f). ns, not significant. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01.

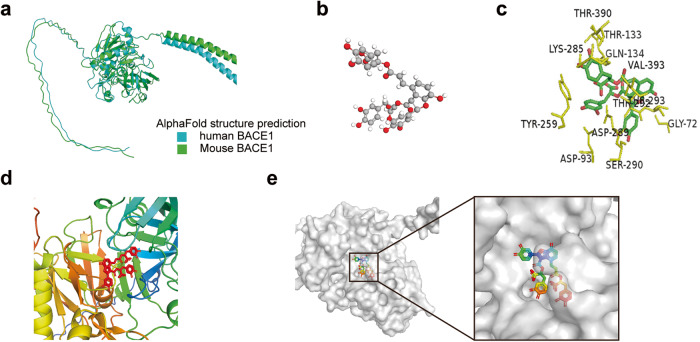

Prediction of the 3D protein structure of BACE1 and its interaction with Sal B

Despite the essential role of BACE1 in the development of Alzheimer’s disease, no high-resolution three-dimensional (3D) structures of human or mouse BACE1 are available in the Protein Data Bank (PDB). To gain insight into the binding mechanism of Sal B with BACE1, we employed a computational approach to predict the structures of human and mouse BACE1 using AlphaFold. Our analysis revealed that the predicted structures of both human and mouse BACE1 are highly conserved (Fig. 7a). The 3D structure of Sal B was obtained from the PubChem Compound database (Fig. 7b). To perform molecular docking simulations, we converted BACE1 and Sal B into PDBQT format, excluding all water molecules and adding polar hydrogen atoms. Molecular dynamics models indicated that Sal B engages BACE1 via hydrogen bonding and electrostatic interactions, resulting in stable binding (Fig. 7c–e). Further analysis revealed that VAL-393 (V393) is a critical amino acid residue in the BACE1 enzyme pocket, capable of forming stable hydrogen bonds, van der Waals forces, and hydrophobic interactions with Sal B, making it the most crucial binding site between BACE1 and Sal B. LYS-285 (K285) interacted with the drug through ionic bonds, van der Waals forces, and hydrogen bonds, enhancing the binding affinity between BACE1 and Sal B. Conversely, other residues, such as THR-133 (T133), THR-390, and LYS-285, did not form a binding interaction with Sal B and did not affect the binding of Sal B to the binding pocket (Fig. 7c–e).

Fig. 7. Molecular dynamics models predict a stable binding of Sal B and BACE1.

a Predicted structures of human BACE1 and mouse BACE1, represented as cartoons. b 3D structure of Sal B. c 2D representation of BACE1 and Sal B interactions, and the amino acid residues interacting with Sal B are shown in yellow. d, e The binding modes of BACE1 and Sal B were predicted using molecular docking. BACE1 is shown in the cartoon model (d) and with the transparent protein surface (e), where Sal B is shown as a stick model.

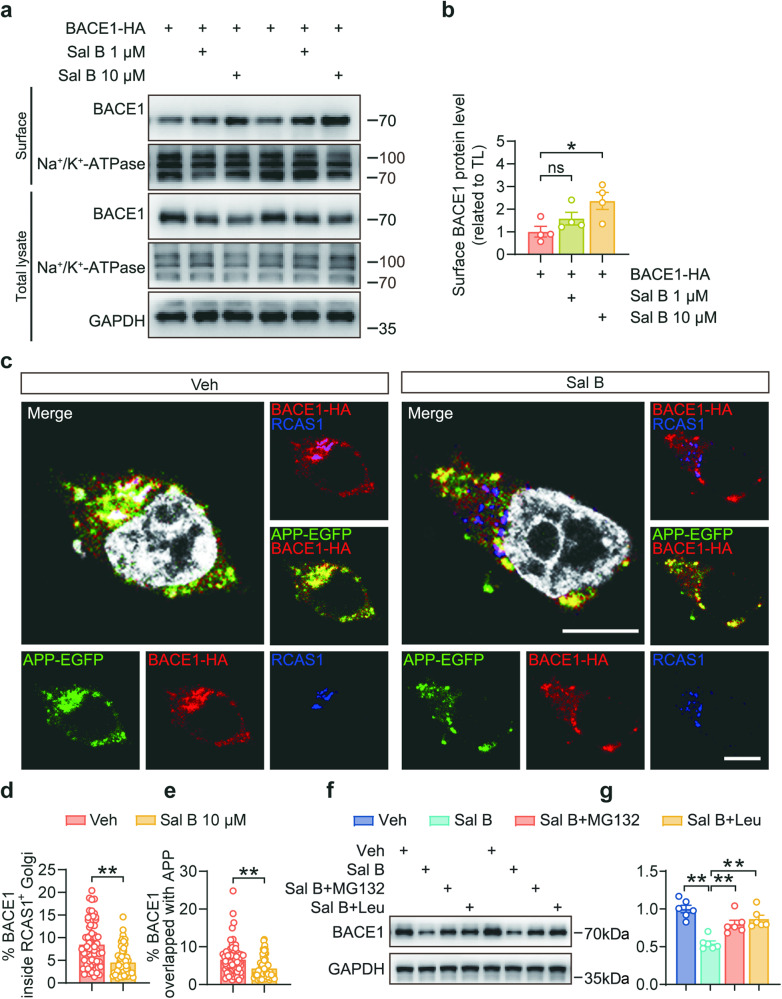

Sal B inhibits BACE1 sorting into the Golgi apparatus and leads to mislocalization and degradation

We conducted cell surface biotinylation assays to validate the influence of Sal B on BACE1 distribution. Our findings demonstrated that Sal B significantly increased the cell surface localization of BACE1, indicating a marked reduction in BACE1 within the Golgi apparatus (Fig. 8a, b). This reduction was further corroborated by our immunofluorescence staining results, which revealed that Sal B diminished the colocalization of BACE1 with the RCAS1-positive Golgi apparatus, suggesting that Sal B decreased the sorting of BACE1 into the Golgi apparatus (Fig. 8c, d). These observations were in line with the reduction in the colocalization of BACE1 and APP, indicating that Sal B substantially reduced APP cleavage by BACE1, thereby suppressing Aβ production (Fig. 8c, e).

Fig. 8. Sal B inhibited the sorting of BACE1 into the Golgi apparatus.

a, b The expression of BACE1-HA in SH-SY5Y-APP751 cells after Sal B treatment of 48 h was determined using a surface biotinylation assay. Na+/K+-ATPase was used as an internal control. n = 4 per group. c–e Representative immunostaining and colocalization analysis of APP-EGFP (green) and BACE1-HA (red) with RCAS1+ Golgi (blue) in 293 T cells after Sal B treatment of 48 h. n = 57 to 66 per group. Scale bar: 10 μm. f, g Immunoblot analysis of BACE1 in SH-SY5Y-APP751 cells treated with 10 μM Sal B for 48 h and 10 μM MG132 (proteasomal inhibitor) or 100 μg/mL leupeptin (lysosomal inhibitor). All data are depicted as the mean ± SEM. P-values were determined using one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s post hoc analysis in (b) and (g), by Student’s t-test in (d) and (e). ns not significant. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01.

To validate the binding interaction between BACE1 and Sal B, we introduced mutations at the predicted binding sites, resulting in V393E and K285D variants, and further examined whether Sal B treatment affected BACE1 localization in the Golgi apparatus. Our results demonstrated that when the binding sites were mutated, the interaction between Sal B and BACE1 was disrupted, thereby preventing Sal B from influencing BACE1 localization in the Golgi apparatus (Supplementary Fig. 5a, b). We treated SH-SY5Y-APP751 cells with the proteasome inhibitor MG132 and the lysosome inhibitor leupeptin and observed differences in BACE1 protein levels between the Sal B-treated experimental group and the untreated control group. The results revealed that both the proteasome inhibitor MG132 and the lysosome inhibitor leupeptin reversed the BACE1 degradation effects induced by Sal B (Fig. 8f, g). This suggested that Sal B binds to BACE1, causing errors in its intracellular distribution and transport. Specifically, binding of Sal B to BACE1 could potentially interfere with the sorting of BACE1 from the endoplasmic reticulum to the Golgi apparatus. This interference leads to errors in BACE1 protein localization, thereby promoting its clearance. Consequently, under the influence of Sal B, BACE1 is more prone to degradation via the lysosomal and proteasomal pathways.

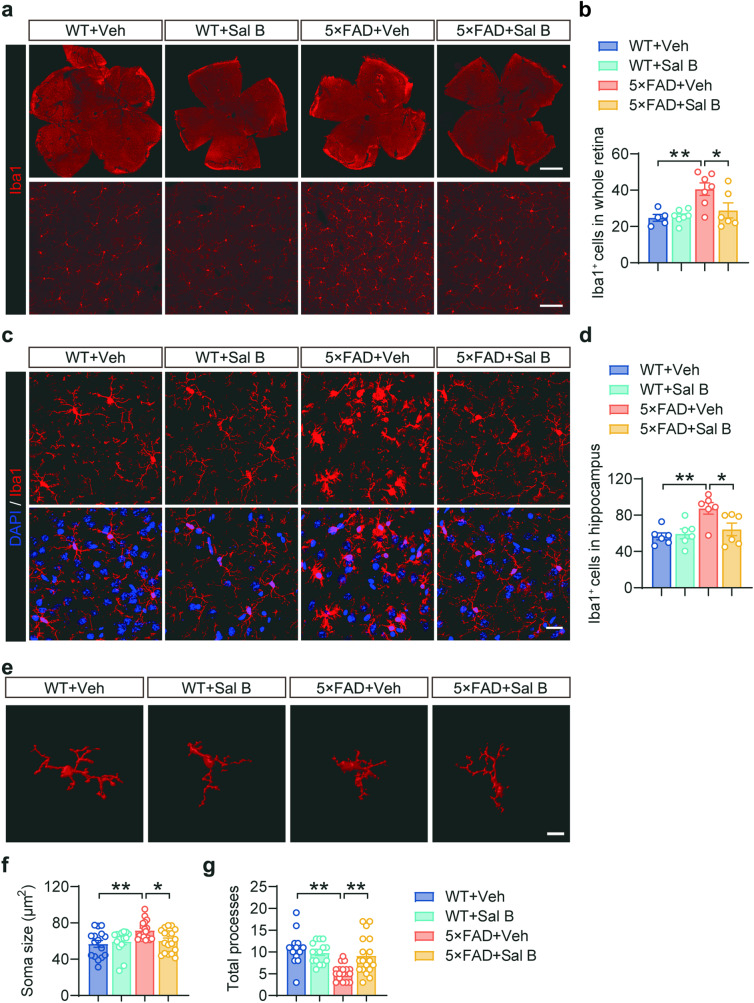

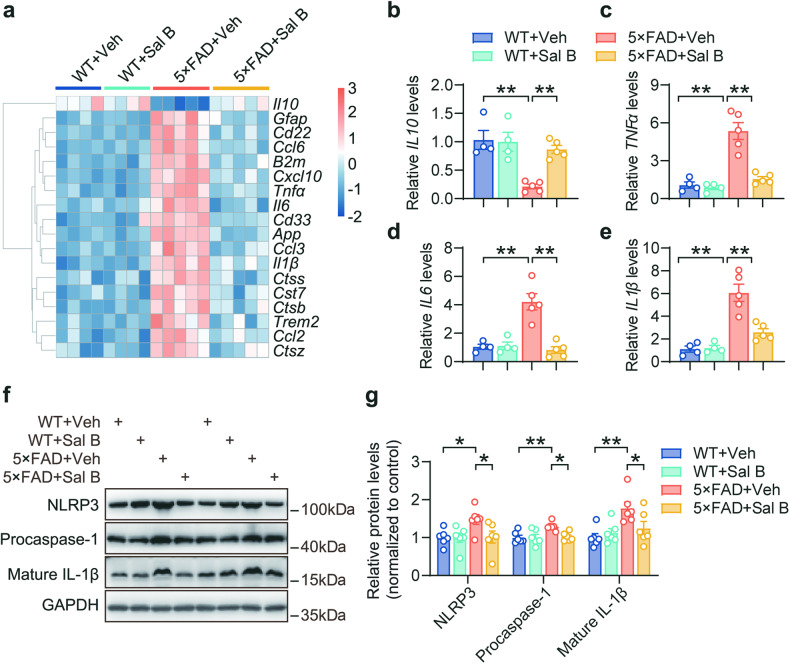

Sal B attenuates microglial activation and inflammation in the retina of 5×FAD mice

Microglia, the primary immune cells of the central nervous system, play a crucial role in phagocytosis of abnormal proteins and clearance of cellular debris. However, chronic activation of microglia results in the sustained release of proinflammatory cytokines, contributing to the neurotoxic pathogenic effects of neurodegeneration [28]. Our immunofluorescence staining analysis results revealed that the number of microglia in the retina was increased in AD mice (Fig. 9a, b), and the bodies size of microglia was increased (Fig. 9e, f), whereas the branching complexity was decreased (Fig. 9e, g). In contrast, the administration of Sal B mitigated microglial proliferation and activation. Similar results were observed in the hippocampus of the 5×FAD mice (Fig. 9c, d). Furthermore, the expression of immune- and inflammation-related genes was restored in the retina of 5×FAD mice treated with Sal B compared with that in untreated 5×FAD mice (Fig. 10a–e). Further investigation demonstrated that Sal B exhibited significant inhibitory effects on the NLRP3 inflammasome pathway (Fig. 10f, g). These findings suggest that Sal B effectively reduced microglial activation and the associated inflammatory release induced by Aβ plaque deposition in the retinas of 5×FAD mice.

Fig. 9. Sal B inhibited microglial activation in 5×FAD mice.

a, b Representative immunostaining (a) and quantification of Iba1+ microglia (b) in the retina of WT + Veh, WT + Sal B, 5×FAD + Veh, and 5×FAD + Sal B mice at 4 months of age. n = 5 to 7 per group. Scale bar, 1 mm and 100 μm. c, d Representative immunostaining (c) and quantification of Iba1+ microglia (d) in the hippocampus of WT + Veh, WT + Sal B, 5×FAD + Veh, and 5×FAD + Sal B mice at 4 months of age. n = 6 per group. Scale bar, 20 μm. e–g Representative 3D reconstruction of Iba1+ microglia in the retina using Imaris software (e). Scale bar, 10 μm. Quantification of microglial soma size (f) and total processes (g). n = 15 to 18 per group. All data are represented as the mean ± SEM. P values were determined by one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s post hoc analysis in (b), (d), (f) and (g). *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01.

Fig. 10. Sal B reduced retinal inflammation in 5×FAD mice.

a Heatmap of RNA transcripts in the retina of WT + Veh, WT + Sal B, 5×FAD + Veh, and 5×FAD + Sal B mice at 4 months of age. n = 4 to 5 per group. b–e qRT-PCR analysis of Il10, Tnfα, Il6, and Il1β mRNA levels in the retinas of WT + Veh, WT + Sal B, 5×FAD + Veh, and 5×FAD + Sal B mice at 4 months of age. n = 4 to 5 per group. f, g Immunoblot assessment of the immune response and inflammation-related proteins in the retina of WT + Veh, WT + Sal B, 5×FAD + Veh, and 5×FAD + Sal B mice at 4 months of age. n = 6 per group. All data are represented as the mean ± SEM. P-values were determined by one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s post hoc analysis in (b–e), and by one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc analysis in (g). *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01.

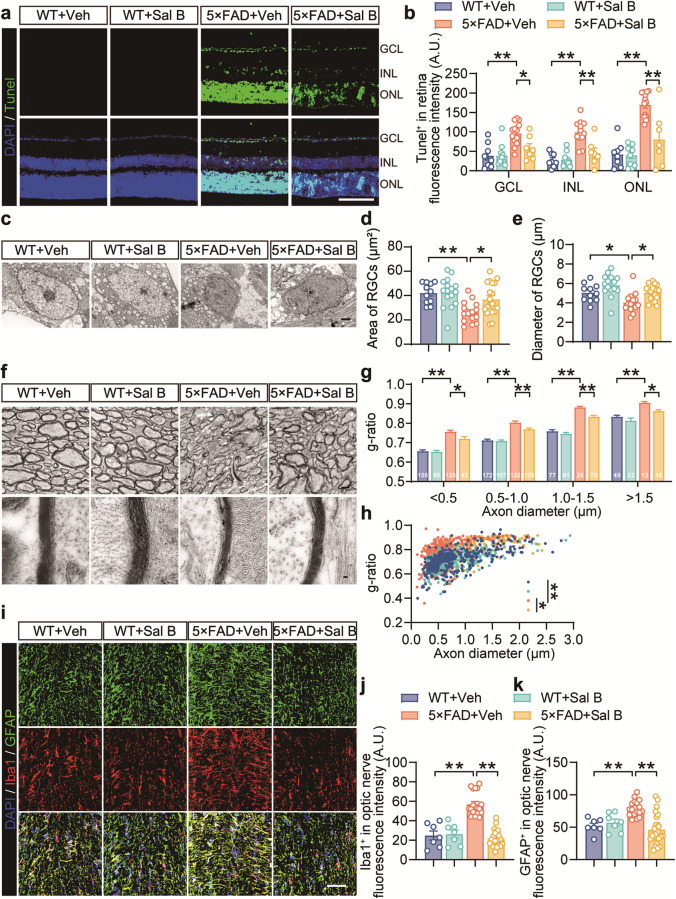

Sal B ameliorated retinal ganglion cell injury in the retina of AD mice

In Alzheimer’s disease, the accumulation of amyloid-beta plaques and the activation of microglia contribute to neuroinflammation, ultimately resulting in neuronal damage and cell death. To investigate the effect of Sal B on retinal neurons, we performed TUNEL staining and observed that the rate of apoptosis in the retinal ganglion cell layer was reduced in 5×FAD mice treated with Sal B compared with that in untreated 5×FAD mice (Fig. 11a, b). Electron microscopy analysis revealed that Sal B treatment improved the area and diameter of ganglion cell bodies in 5×FAD mice (Fig. 11c–e). We investigated the effects of Sal B on RGC axons, which are vital for transmitting visual information from the retina to the visual cortex. The g-ratio, a widely used morphometric parameter in neuroscience, evaluates axon myelination by comparing the inner diameter of the axon to the overall fiber diameter, including myelin. Changes in the g-ratio can indicate various neurological conditions including myelin alterations and axonal integrity. Our results showed an increased g-ratio in the retinas of the 5×FAD mice, suggesting axonal thinning and potential damage. Additionally, we observed reduced myelin thickness in RGC axons of 5×FAD mice, indicating impaired transmission. Sal B treatment improved myelin sheath thickness in RGC axons (Fig. 11f–h). Additionally, immunofluorescence analysis suggested that Sal B mitigated the proliferation and activation of microglia and astrocytes in the optic nerve, corroborating the results observed in the retina (Fig. 11i–k).

Fig. 11. Sal B restored RGC deficits in 5×FAD mice.

a Representative images showing TUNEL staining in the retina of WT + Veh, WT + Sal B, 5×FAD + Veh, and 5×FAD + Sal B mice at 4 months of age. Scale bar, 50 μm. b Quantification of TUNEL+ cells in GCL, INL, and ONL. n = 7 to 13 per group. c–e Electron microscopy analyses of the area (d) and diameter (e) of the RGCs. Scale bar, 1 μm. n = 11 to 19 per group. f–h Representative images of electron microscopy (f) and analyses of the g-ratio (g, h) in the optic nerves of WT + Veh, WT + Sal B, 5×FAD + Veh, and 5×FAD + Sal B mice at four months of age. Scale bars, 1 μm and 50 nm. n = 300 to 400 per group. i–k Representative immunostaining (i) and quantification of Iba1+ microglia (j) and GFAP+ astrocytes (k) in the optic nerve of WT + Veh, WT + Sal B, 5×FAD + Veh, and 5×FAD + Sal B mice at 4 months of age. n = 7 to 25 mice per group. Scale bar, 50 μm. All data are represented as the mean ± SEM. P-values were determined by one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc analysis in (b), (g), and (h), and by one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s post hoc analysis in (d), (e), (j), and (k). *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01.

Discussion

AD is a heterogeneous disorder characterized by a range of symptoms, including memory impairment, attention deficit disorder, and visual and spatial activity abnormalities [17, 60]. The overlap of neuropathological symptoms and the subtle onset of AD make it challenging to differentiation and diagnose early [61–63]. Preclinical AD-related pathology is believed to begin decades before the onset of symptoms, making it essential to find direct and noninvasive methods for monitoring disease progression [61, 64]. Retina, as an essential part of the CNS, is closely related to the brain and offers unique advantages for early AD diagnosis [65]. Owing to its clear optical quality, the retina is the only location where neurons and blood vessels can be visualized noninvasively, making it a potential new method for early AD diagnosis. Research and detection of the retina can be noninvasive, simple, and cost-effective, presenting new opportunities for the clinical management of AD [66–68].

In patients with AD, the accumulation of soluble Aβ oligomers in the brain begins one to two decades before any clinical symptoms appear, while the formation of Aβ plaques typically occurs later [69]. According to a study by Pogue et al. [70], Aβ deposits in the retina are present in mice as young as 1.5 months, suggesting that the appearance of soluble Aβ oligomers likely precedes this age. Therefore, we initiated drug intervention at one month of age as a preventative measure. Our results demonstrate that this early intervention effectively delayed AD progression, which could potentially have therapeutic implications for early-stage AD. In light of the current advancements in early diagnosis through blood, cerebrospinal fluid testing, etc., our research suggests that Sal B significantly improve and delay AD progression, providing a promising therapeutic option for early AD.

Our findings suggest that the retina is more susceptible to Aβ plaque-induced damage than the brain, likely because of its higher concentration of densely populated functional neural regions [71, 72]. Consequently, the effect of Aβ plaques on neurons is more direct and severe in the retina than in the brain. The retina is also rich in blood vessels and blood, which facilitates the entry of inflammatory factors and their damaging effects through the blood-retina barrier [73]. Furthermore, the higher metabolic activity of retinal neurons and glial cells renders them more vulnerable to interference from external inflammatory factors [74, 75]. Additionally, the diversity and complexity of retinal neuronal activity and connections may trigger a more intricate cascade of reactions, amplifying the damage caused by neural injury [76–78].

Here, we present evidence of changes in retinal structure and function in 4-month-old 5×FAD mice. The results indicated that the total retinal thickness, as well as the thickness of the ganglion cell and inner plexiform layers, were significantly reduced compared to the control group. This reduction in retinal thickness has been observed in previous studies conducted using various AD mouse models [23, 26, 29, 79, 80]. Despite the use of different segmentation methods, the results were consistent. For example, in 3×Tg-AD mice, the retinal inner layer (GCL + IPL) began to thin at 4 months of age, and the middle and outer retinal layers (INL + OPL, ONL, and IS + OS layers) changed significantly at 8, 12, and 16 months of age [81]. Similarly, in APP/PS1 mice, the size of the retina gradually decreases from 3 months of age, with significant changes in retinal thickness observed at 6, 9, and 12 months of age [6]. Functionally, the dark and light responses of the retina in 4-month-old 5×FAD mice were significantly decreased at various light intensities, indicating damage to photoreceptor cells in the early stage. The retinal PhNR showed that ganglion cells in 4-month-old 5×FAD mice were diminished in response to light, suggesting dysfunction of these cells in the early stage. Our findings are in agreement with studies on ganglion cell detection in other mouse models, such as APP/PS1 [25, 82] and 3×Tg-AD mice [28]. Furthermore, with age, the retina of AD mice demonstrated further decreases in amplitude, including the photoreceptor P3 and bipolar cell P2 in 17-month-old 5×FAD mice, and decreases in the photoreceptor [23] a-wave and bipolar cell b-wave in 12-month-old APP/PS1 mice [26].

In this study, we report the accumulation of Aβ plaques in the retinal ganglion cell layer of 5×FAD mice, which leads to various pathological changes, including microglial activation and excessive release of inflammatory factors, ultimately resulting in damage to retinal structure and function. Immunofluorescence and immunohistochemical results revealed that the accumulated Aβ plaques in the GCL of the 5×FAD mice were highly neurotoxic. Further analysis using TUNEL staining showed that apoptosis occurred in the GCL, which may have contributed to the decrease in retinal thickness. Inhibition of Aβ formation is the most effective approach [83]. BACE1 is a key enzyme involved in Aβ production through APP cleavage, and our results showed that Sal B effectively decreased BACE1 expression, thereby reducing Aβ production. Using AlphaFold, we predicted the structure of BACE1 and observed a strong interaction between BACE1 and Sal B through molecular dynamics modeling. Our analysis also revealed that Sal B inhibits the sorting of BACE1 into the Golgi apparatus, which is the main site for APP cleavage by BACE1 [84]. Sal B reduced APP cleavage and the amount of Aβ plaques, as verified by immunofluorescence experiments.

Functionally, our electroretinogram results showed that Sal B improved the amplitudes of the a- and b-waves under both dark and light adaptation in 5×FAD mice, indicating an improvement in retinal function. Furthermore, the thickness of the retinal GCL + IPL was improved and there was a corresponding increase in the number of GCL cells as a result of Sal B treatment. In our study, we also found evidence of the restoration of myelin sheath injury in the axon of RGCs following Sal B administration. These observations align with previous work by Li et al. who reported that Sal B can protect the myelin sheath around axons in spinal cord injury [85].

Multiple mechanisms may contribute to the improvement in retinal structure and function observed in AD-related 5×FAD mice following treatment with Sal B. Excessive activation of microglia and overproduction of inflammatory factors, such as TNFα, IL6, and IL1β, can have harmful effects on neurons and contribute to the progression of neurodegenerative diseases. Inhibiting the release of these factors can improve the retinal environment in AD [86]. Our results showed that Sal B treatment resulted in a decrease in the activation of retinal microglia and release of inflammatory factors in 5×FAD mice, suggesting a shift towards a more stable state. The restoration of retinal structure and function may also be related to the inhibition of apoptosis and the promotion of neurogenesis by Sal B. TUNEL staining showed a decrease in apoptosis in the retinal GCL of 5×FAD mice after Sal B administration. Previous studies have also demonstrated that Sal B can reduce oxidative damage to neurons [43, 87] and restore normal mitochondrial function [88, 89].

In conclusion, our study provides evidence of the protective effect of Sal B against retinal structural and functional alterations in an AD mouse model. Our findings shed new light on the potential therapeutic mechanisms of Sal B in mitigating Aβ-induced retinal damage and strengthen the view for considering Sal B as a promising therapeutic candidate for AD.

Supplementary information

Author contributions

LW conceived the study and designed the experiments; MDW and SZ wrote the manuscript; LW, SYL, and SFL edited the manuscript; MDW and SZ performed most of the experiments; MDW, SZ, XYL, and PPW performed morphological analyses; YFZ, JRZ, CSL, SY, and SFL analyzed and contributed reagents/materials/analysis tools. XYL performed LTP analyses; LW supervised the project. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Funding

The work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (82274301 and 81774377), the Natural Science Foundation of Fujian Province of China (Grant No. 2021J01019), the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2016YFC1305903) and the Program for New Century Excellent Talents in University of China (NCET-13-0505) (to LW).

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, upon reasonable request.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

These authors contributed equally: Meng-dan Wang, Shuo Zhang

Contributor Information

Shi-ying Li, Email: shiying_li@126.com.

Sui-feng Liu, Email: liujiasuifeng@gmail.com.

Lei Wen, Email: wenlei@xmu.edu.cn.

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41401-023-01125-3.

References

- 1.Shi H, Koronyo Y, Rentsendorj A, Fuchs DT, Sheyn J, Black KL, et al. Retinal vasculopathy in Alzheimer’s disease. Front Neurosci. 2021;15:731614. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2021.731614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fernández-Albarral JA, Salobrar-García E, Martínez-Páramo R, Ramírez AI, de Hoz R, Ramírez JM, et al. Retinal glial changes in Alzheimer’s disease - A review. J Optom. 2019;12:198–207. doi: 10.1016/j.optom.2018.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Madeira MH, Ambrósio AF, Santiago AR. Glia-mediated retinal neuroinflammation as a biomarker in Alzheimer’s disease. Ophthalmic Res. 2015;54:204–11. doi: 10.1159/000440887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dehabadi MH, Davis BM, Wong TK, Cordeiro MF. Retinal manifestations of Alzheimer’s disease. Neurodegener Dis Manag. 2014;4:241–52. doi: 10.2217/nmt.14.19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Koronyo-Hamaoui M, Koronyo Y, Ljubimov AV, Miller CA, Ko MK, Black KL, et al. Identification of amyloid plaques in retinas from Alzheimer’s patients and noninvasive in vivo optical imaging of retinal plaques in a mouse model. NeuroImage. 2011;54:S204–17. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2010.06.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Georgevsky D, Retsas S, Raoufi N, Shimoni O, Golzan SM. A longitudinal assessment of retinal function and structure in the APP/PS1 transgenic mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. Transl Neurodegener. 2019;8:30. doi: 10.1186/s40035-019-0170-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dolci GAM, Damanti S, Scortichini V, Galli A, Rossi PD, Abbate C, et al. Alzheimer’s disease diagnosis: discrepancy between clinical, neuroimaging, and cerebrospinal fluid biomarkers criteria in an Italian cohort of geriatric outpatients: A retrospective cross-sectional study. Front Med. 2017;4:203. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2017.00203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tan CC, Yu JT, Tan L. Biomarkers for preclinical Alzheimer’s disease. J Alzheimers Dis. 2014;42:1051–69. doi: 10.3233/JAD-140843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fiandaca MS, Mapstone ME, Cheema AK, Federoff HJ. The critical need for defining preclinical biomarkers in Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2014;10:S196–212. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2014.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Norton S, Matthews FE, Barnes DE, Yaffe K, Brayne C. Potential for primary prevention of Alzheimer’s disease: An analysis of population-based data. Lancet Neurol. 2014;13:788–94. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(14)70136-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kim K, Kim MJ, Kim DW, Kim SY, Park S, Park CB. Clinically accurate diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease via multiplexed sensing of core biomarkers in human plasma. Nat Commun. 2020;11:119. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-13901-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Salobrar-García E, de Hoz R, Ramírez AI, López-Cuenca I, Rojas P, Vazirani R, et al. Changes in visual function and retinal structure in the progression of Alzheimer’s disease. PLoS One. 2019;14:e0220535. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0220535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Danesh-Meyer HV, Birch H, Ku JY, Carroll S, Gamble G. Reduction of optic nerve fibers in patients with Alzheimer disease identified by laser imaging. Neurology. 2006;67:1852–4. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000244490.07925.8b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jack CR, Jr., Lowe VJ, Weigand SD, Wiste HJ, Senjem ML, Knopman DS, et al. Serial PIB and MRI in normal, mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer’s disease: implications for sequence of pathological events in Alzheimer’s disease. Brain. 2009;132:1355–65. doi: 10.1093/brain/awp062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Villemagne VL, Burnham S, Bourgeat P, Brown B, Ellis KA, Salvado O, et al. Amyloid β deposition, neurodegeneration, and cognitive decline in sporadic Alzheimer’s disease: a prospective cohort study. Lancet Neurol. 2013;12:357–67. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(13)70044-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Reiman EM, Quiroz YT, Fleisher AS, Chen K, Velez-Pardo C, Jimenez-Del-Rio M, et al. Brain imaging and fluid biomarker analysis in young adults at genetic risk for autosomal dominant Alzheimer’s disease in the presenilin 1 E280A kindred: a case-control study. Lancet Neurol. 2012;11:1048–56. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(12)70228-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhao A, Fang F, Li B, Chen Y, Qiu Y, Wu Y, et al. Visual abnormalities associate with hippocampus in mild cognitive impairment and early Alzheimer’s disease. Front Aging Neurosci. 2020;12:597491. doi: 10.3389/fnagi.2020.597491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.La Morgia C, Ross-Cisneros FN, Koronyo Y, Hannibal J, Gallassi R, Cantalupo G, et al. Melanopsin retinal ganglion cell loss in Alzheimer disease. Ann Neurol. 2016;79:90–109. doi: 10.1002/ana.24548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bevan RJ, Hughes TR, Williams PA, Good MA, Morgan BP, Morgan JE. Retinal ganglion cell degeneration correlates with hippocampal spine loss in experimental Alzheimer’s disease. Acta Neuropathol Commun. 2020;8:216. doi: 10.1186/s40478-020-01094-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Paquet C, Boissonnot M, Roger F, Dighiero P, Gil R, Hugon J. Abnormal retinal thickness in patients with mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer’s disease. Neurosci Lett. 2007;420:97–9. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2007.02.090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gao L, Liu Y, Li X, Bai Q, Liu P. Abnormal retinal nerve fiber layer thickness and macula lutea in patients with mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer’s disease. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2015;60:162–7. doi: 10.1016/j.archger.2014.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhang M, Zhong L, Han X, Xiong G, Xu D, Zhang S, et al. Brain and retinal abnormalities in the 5xFAD mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease at early stages. Front Neurosci. 2021;15:681831. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2021.681831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lim JKH, Li QX, He Z, Vingrys AJ, Chinnery HR, Mullen J, et al. Retinal functional and structural changes in the 5xFAD mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. Front Neurosci. 2020;14:862. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2020.00862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dinet V, An N, Ciccotosto GD, Bruban J, Maoui A, Bellingham SA, et al. APP involvement in retinogenesis of mice. Acta Neuropathol. 2011;121:351–63. doi: 10.1007/s00401-010-0762-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ning A, Cui J, To E, Ashe KH, Matsubara J. Amyloid-beta deposits lead to retinal degeneration in a mouse model of Alzheimer disease. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2008;49:5136–43. doi: 10.1167/iovs.08-1849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Perez SE, Lumayag S, Kovacs B, Mufson EJ, Xu S. Beta-amyloid deposition and functional impairment in the retina of the APPswe/PS1DeltaE9 transgenic mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. Investigative Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2009;50:793–800. doi: 10.1167/iovs.08-2384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Edwards MM, Rodríguez JJ, Gutierrez-Lanza R, Yates J, Verkhratsky A, Lutty GA. Retinal macroglia changes in a triple transgenic mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. Exp Eye Res. 2014;127:252–60. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2014.08.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Grimaldi A, Brighi C, Peruzzi G, Ragozzino D, Bonanni V, Limatola C, et al. Inflammation, neurodegeneration and protein aggregation in the retina as ocular biomarkers for Alzheimer’s disease in the 3xTg-AD mouse model. Cell Death Dis. 2018;9:685. doi: 10.1038/s41419-018-0740-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Liu B, Rasool S, Yang Z, Glabe CG, Schreiber SS, Ge J, et al. Amyloid-peptide vaccinations reduce {beta}-amyloid plaques but exacerbate vascular deposition and inflammation in the retina of Alzheimer’s transgenic mice. Am J Pathol. 2009;175:2099–110. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2009.090159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.De Groef L, Cordeiro MF. Is the eye an extension of the brain in central nervous system disease? J Ocul Pharmacol Ther. 2018;34:129–33. doi: 10.1089/jop.2016.0180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cordeiro MF. Eyeing the brain. Acta Neuropathol. 2016;132:765–6. doi: 10.1007/s00401-016-1628-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.London A, Benhar I, Schwartz M. The retina as a window to the brain-from eye research to CNS disorders. Nat Rev Neurol. 2013;9:44–53. doi: 10.1038/nrneurol.2012.227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Song A, Johnson N, Ayala A, Thompson AC. Optical coherence tomography in patients with Alzheimer’s disease: what can it tell us? Eye Brain. 2021;13:1–20. doi: 10.2147/EB.S235238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kurna SA, Akar G, Altun A, Agirman Y, Gozke E, Sengor T. Confocal scanning laser tomography of the optic nerve head on the patients with Alzheimer’s disease compared to glaucoma and control. Int Ophthalmol. 2014;34:1203–11. doi: 10.1007/s10792-014-0004-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chiquita S, Rodrigues-Neves AC, Baptista FI, Carecho R, Moreira PI, Castelo-Branco M, et al. The retina as a window or mirror of the brain changes detected in Alzheimer’s disease: Critical aspects to unravel. Mol Neurobiol. 2019;56:5416–35. doi: 10.1007/s12035-018-1461-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gupta VB, Chitranshi N, den Haan J, Mirzaei M, You Y, Lim JK, et al. Retinal changes in Alzheimer’s disease- integrated prospects of imaging, functional and molecular advances. Prog Retin Eye Res. 2021;82:100899. doi: 10.1016/j.preteyeres.2020.100899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Liu J, Baum L, Yu S, Lin Y, Xiong G, Chang RC, et al. Preservation of retinal function through synaptic stabilization in Alzheimer’s disease model mouse retina by Lycium Barbarum extracts. Front Aging Neurosci. 2021;13:788798. doi: 10.3389/fnagi.2021.788798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Katz L, Baltz RH. Natural product discovery: past, present, and future. J Ind Microbiol Biotechnol. 2016;43:155–76. doi: 10.1007/s10295-015-1723-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sun ZQ, Liu JF, Luo W, Wong CH, So KF, Hu Y, et al. Lycium barbarum extract promotes M2 polarization and reduces oligomeric amyloid-beta-induced inflammatory reactions in microglial cells. Neural Regen Res. 2022;17:203–9. doi: 10.4103/1673-5374.314325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Li S, Wu Z, Le W. Traditional Chinese medicine for dementia. Alzheimers Dement. 2021;17:1066–71. doi: 10.1002/alz.12258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lee YW, Kim DH, Jeon SJ, Park SJ, Kim JM, Jung JM, et al. Neuroprotective effects of salvianolic acid B on an Aβ25-35 peptide-induced mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. Eur J Pharmacol. 2013;704:70–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2013.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tan FHP, Ting ACJ, Leow BG, Najimudin N, Watanabe N, Azzam G. Alleviatory effects of Danshen, Salvianolic acid A and Salvianolic acid B on PC12 neuronal cells and Drosophila melanogaster model of Alzheimer’s disease. J Ethnopharmacol. 2021;279:114389. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2021.114389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Huang Q, Ye X, Wang L, Pan J. Salvianolic acid B abolished chronic mild stress-induced depression through suppressing oxidative stress and neuro-inflammation via regulating NLRP3 inflammasome activation. J Food Biochem. 2019;43:e12742. doi: 10.1111/jfbc.12742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Liao D, Chen Y, Guo Y, Wang C, Liu N, Gong Q, et al. Salvianolic Acid B improves chronic mild stress-induced depressive behaviors in rats: Involvement of AMPK/SIRT1 Signaling Pathway. J Inflamm Res. 2020;13:195–206. doi: 10.2147/JIR.S249363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zhang JQ, Wu XH, Feng Y, Xie XF, Fan YH, Yan S, et al. Salvianolic acid B ameliorates depressive-like behaviors in chronic mild stress-treated mice: involvement of the neuroinflammatory pathway. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2016;37:1141–53. doi: 10.1038/aps.2016.63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zhou J, Qu XD, Li ZY, Wei J, Liu Q, Ma YH, et al. Salvianolic acid B attenuates toxin-induced neuronal damage via Nrf2-dependent glial cells-mediated protective activity in Parkinson’s disease models. PLoS One. 2014;9:e101668. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0101668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zhao Y, Zhang Y, Zhang J, Yang G. Salvianolic acid B protects against MPP+-induced neuronal injury via repressing oxidative stress and restoring mitochondrial function. Neuroreport. 2021;32:815–23. doi: 10.1097/WNR.0000000000001660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zhang J, Xie X, Tang M, Zhang J, Zhang B, Zhao Q, et al. Salvianolic acid B promotes microglial M2-polarization and rescues neurogenesis in stress-exposed mice. Brain Behav Immun. 2017;66:111–24. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2017.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Liu J, Wang Y, Guo J, Sun J, Sun Q. Salvianolic Acid B improves cognitive impairment by inhibiting neuroinflammation and decreasing Aβ level in Porphyromonas gingivalis-infected mice. Aging. 2020;12:10117–28. doi: 10.18632/aging.103306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Jiang P, Guo Y, Dang R, Yang M, Liao D, Li H, et al. Salvianolic acid B protects against lipopolysaccharide-induced behavioral deficits and neuroinflammatory response: involvement of autophagy and NLRP3 inflammasome. J Neuroinflamm. 2017;14:239. doi: 10.1186/s12974-017-1013-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Durairajan SS, Yuan Q, Xie L, Chan WS, Kum WF, Koo I, et al. Salvianolic acid B inhibits Abeta fibril formation and disaggregates preformed fibrils and protects against Abeta-induced cytotoxicty. Neurochem. Int. 2008;52:741–50. doi: 10.1016/j.neuint.2007.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lin YH, Liu AH, Wu HL, Westenbroek C, Song QL, Yu HM, et al. Salvianolic acid B, an antioxidant from Salvia miltiorrhiza, prevents Abeta(25-35)-induced reduction in BPRP in PC12 cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2006;348:593–9. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.07.110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Liu SM, Yang ZH, Sun XB. Simultaneous determination of six Salvia miltiorrhiza gradients in rat plasma and brain by LC-MS/MS. China J Chin Mater Med. 2014;39:1704–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Peng B, Xiao J, Wang K, So KF, Tipoe GL, Lin B. Suppression of microglial activation is neuroprotective in a mouse model of human retinitis pigmentosa. J Neurosci. 2014;34:8139–50. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5200-13.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Zheng Q, Li G, Wang S, Zhou Y, Liu K, Gao Y, et al. Trisomy 21-induced dysregulation of microglial homeostasis in Alzheimer’s brains is mediated by USP25. Sci Adv. 2021;7:eabe1340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 56.Wen L, Tang FL, Hong Y, Luo SW, Wang CL, He W, et al. VPS35 haploinsufficiency increases Alzheimer’s disease neuropathology. J Cell Biol. 2011;195:765–79. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201105109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wen L, Lu YS, Zhu XH, Li XM, Woo RS, Chen YJ, et al. Neuregulin 1 regulates pyramidal neuron activity via ErbB4 in parvalbumin-positive interneurons. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:1211–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0910302107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Zhong L, Xu Y, Zhuo R, Wang T, Wang K, Huang R, et al. Soluble TREM2 ameliorates pathological phenotypes by modulating microglial functions in an Alzheimer’s disease model. Nat Commun. 2019;10:1365. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-09118-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Zheng Q, Song B, Li G, Cai F, Wu M, Zhao Y, et al. USP25 inhibition ameliorates Alzheimer’s pathology through the regulation of APP processing and Aβ generation. J Clin Invest. 2022;132:e152170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 60.Wang J, Gu BJ, Masters CL, Wang YJ. A systemic view of Alzheimer disease - insights from amyloid-β metabolism beyond the brain. Nat Rev Neurol. 2017;13:612–23. doi: 10.1038/nrneurol.2017.111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Hane FT, Robinson M, Lee BY, Bai O, Leonenko Z, Albert MS. Recent progress in Alzheimer’s disease research, Part 3: diagnosis and treatment. J Alzheimers Dis. 2017;57:645–65. doi: 10.3233/JAD-160907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Hane FT, Lee BY, Leonenko Z. Recent progress in Alzheimer’s disease research, Part 1: Pathology. J Alzheimer’s Dis. 2017;57:1–28. doi: 10.3233/JAD-160882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Robinson M, Lee BY, Hane FT. Recent progress in Alzheimer’s disease research, Part 2: Genetics and Epidemiology. J Alzheimers Dis. 2017;57:317–30. doi: 10.3233/JAD-161149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Masters CL, Bateman R, Blennow K, Rowe CC, Sperling RA, Cummings JL. Alzheimer’s disease. Nat Rev Dis Prim. 2015;1:15056. doi: 10.1038/nrdp.2015.56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Mirzaei N, Shi H, Oviatt M, Doustar J, Rentsendorj A, Fuchs DT, et al. Alzheimer’s retinopathy: seeing disease in the eyes. Front Neurosci. 2020;14:921. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2020.00921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Lim JK, Li QX, He Z, Vingrys AJ, Wong VH, Currier N, et al. The eye as a biomarker for Alzheimer’s disease. Front Neurosci. 2016;10:536. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2016.00536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Golzan SM, Goozee K, Georgevsky D, Avolio A, Chatterjee P, Shen K, et al. Retinal vascular and structural changes are associated with amyloid burden in the elderly: ophthalmic biomarkers of preclinical Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Res Ther. 2017;9:13. doi: 10.1186/s13195-017-0239-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Patton N, Aslam T, Macgillivray T, Pattie A, Deary IJ, Dhillon B. Retinal vascular image analysis as a potential screening tool for cerebrovascular disease: a rationale based on homology between cerebral and retinal microvasculatures. J Anat. 2005;206:319–48. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7580.2005.00395.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Hector A, Brouillette J. Hyperactivity induced by soluble Amyloid-β oligomers in the early stages of Alzheimer’s disease. Front Mol Neurosci. 2020;13:600084. doi: 10.3389/fnmol.2020.600084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Pogue AI, Dua P, Hill JM, Lukiw WJ. Progressive inflammatory pathology in the retina of aluminum-fed 5xFAD transgenic mice. J Inorg Biochem. 2015;152:206–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jinorgbio.2015.07.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Baden T, Berens P, Franke K, Román Rosón M, Bethge M, Euler T. The functional diversity of retinal ganglion cells in the mouse. Nature. 2016;529:345–50. doi: 10.1038/nature16468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Dow BM. Central mechanisms of vision: parallel processing. Fed Proc. 1976;35:54–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Moss HE. Retinal vascular changes are a marker for cerebral vascular diseases. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep. 2015;15:40. doi: 10.1007/s11910-015-0561-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Vecino E, Rodriguez FD, Ruzafa N, Pereiro X, Sharma SC. Glia-neuron interactions in the mammalian retina. Prog Retin Eye Res. 2016;51:1–40. doi: 10.1016/j.preteyeres.2015.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Yu DY, Cringle SJ, Yu PK, Su EN, Sun X, Guo W, et al. Retinal cellular metabolism and its regulation and control. In: Maiese K, editor. Neurovascular Medicine: Pursuing Cellular Longevity for Healthy Aging. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2009.

- 76.Marquardt T, Gruss P. Generating neuronal diversity in the retina: One for nearly all. Trends Neurosci. 2002;25:32–8. doi: 10.1016/S0166-2236(00)02028-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Seung HS, Sümbül U. Neuronal cell types and connectivity: Lessons from the retina. Neuron. 2014;83:1262–72. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2014.08.054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Masland RH. Neuronal diversity in the retina. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2001;11:431–6. doi: 10.1016/S0959-4388(00)00230-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Buccarello L, Sclip A, Sacchi M, Castaldo AM, Bertani I, ReCecconi A, et al. The c-jun N-terminal kinase plays a key role in ocular degenerative changes in a mouse model of Alzheimer disease suggesting a correlation between ocular and brain pathologies. Oncotarget. 2017;8:83038–51. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.19886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]