Abstract

Background and Objective

Obesity has historically been seen as a sign of wealth and social privilege, as can be inferred from studying the ancient works. We aimed to report the causes, diagnostic approaches, and treatment among the authentic books of traditional Iranian medicine.

Methods

We searched the original versions of historical books and used a narrative approach to report the history of obesity.

Results

Obesity was often seen as an indicator of complete health. Obesity in healthy women was a requirement for beauty, based on descriptions of women from the Zoroaster period and from antiquity to the late Qajar period. This point of view existed during various ages. However, after the constitutional period, the view of obesity changed into that of an illness, due to modern ideas and offshore role models, especially during the Pahlavi era. This change led to serious attempts to treat obesity. Obesity is a critical problem that needs immediate attention to prevent substantial health consequences. Different medical paradigms have presented their criteria and foundations throughout history. The emphasis of Iranian alternative medicine was on prevention and the maintenance of health, with the next step being treatment. Prevention, treatment, consuming medicinal plants, and recovery have often been written about in the traditional books of medicine.

Conclusions

Throughout the traditional Iranian medical texts, physicians have made recommendations about maintaining an appropriate body weight. The best treatment was prevention and a healthy lifestyle. The treatments for controlling and restricting obesity included paying attention to nourishment, mobility, and even the habitat.

Keywords: cardiovascular, health and history, herbal medicine, obesity, Persian medicine, traditional medicine

1. INTRODUCTION

Obesity can be described as the accumulation of excessive body fat. Epidemiological studies define obesity using the body mass index (BMI), which is the individual's weight in kilograms divided by the square of their height in centimeters. A person is considered underweight if they have a BMI of less than 18.5, normal weight from 18.5 to 24.9, overweight between 25 and 29.9, and obese at or above 30. As seen in the ancient records, throughout history obesity was seen as a sign of wealth and high socioeconomic status. 1 , 2 Obesity was considered to be a sign of social privilege and health, especially among women. 3 It was considered to be a sign of healthy fertility, except in morbid conditions, which were representative of illness. 4 , 5 According to the descriptions of women in the Avesta period (Zoroastrian religious text), physical strength was a very important and valuable feature in ancient Iran. 6 On the other hand, obesity can lead to different complications, including diabetes, cancers, cardiovascular, neurological, and gastrointestinal diseases. 7

Due to the harsh social conditions and the lack of proper nutrition among the lower classes of society, obesity was a sign of good nutrition, and such people, especially women, were desirable for marriage. 8 , 9 However, in parts of Europe and Asia, obesity was stigmatized since it was seen as a karmic result of a moral transgression or gluttony. 10 In the Mēnōg‐ī Khrad (Spirit of Wisdom), which is one of the most important secondary texts in Zoroastrianism, written in Middle Persian, in response to a question about how to maintain and comfort the body, the book recommends moderation in food and exercise as being important for health. 11 , 12 This shows that Iranians paid attention and cared a lot about physical fitness and health.

Different aspects of obesity have been evaluated, such as its epidemiology, risk factors, treatment, and prevention. 13 , 14 Nevertheless, there has been no comprehensive review of the history of obesity in Iranian medicine. Therefore, this article reports the causes, diagnostic approaches, and treatments found in the authentic books of traditional Iranian medicine.

2. METHODS

As the original versions of the historical books were not available in any online databases, we (R. M. N. and S. M.) independently reviewed the chapter titles from all relevant books. The books were sourced from the Central Library of the History of Medicine at the School of Traditional Medicine, Tabriz University of Medical Sciences, Tabriz, Iran, and all relevant chapters, which covered the period from the fourth century BC to the 18th century, were selected. Any disagreements about chapter selection were resolved by consulting a third author (S. S. N.). We then carefully reviewed the main‐texts of all selected chapters and the relevant sections of the chapters were selected for inclusion in this article. In cases where there were disagreements, we again resolved them by consulting a third author (S. S. N.). The search was conducted from February to July 2022 without any language or time filters. The reference lists of all relevant books were also manually checked, to identify any additional qualified books.

3. MAIN RESULTS

The definition of obesity and its relevance to other diseases was well‐known by ancient Greek physicians. 15 As with Iranian scholars, Greek scholars cared about health and believed that being healthy was an obligation. 16 They considered eating and drinking in moderation to be mandatory and highlighted the dangers of having too much or too little. Hippocrates (fourth century BC), the father of medicine, believed that eating abnormal quantities of food could lead to illness. 17 In his opinion, there were five factors leading to death, three of which were relevant to the time of eating and overeating. 18 Hippocrates stated that sudden death was more common in people with obesity and that obesity was the cause of irregular menstruation and infertility among women 19 Previous research has found obesity to be associated with several adverse reproductive outcomes, including menstrual dysfunction, anovulation, infertility, miscarriage, and pregnancy complications. 20 , 21

According to Galen (first century AD), who was the founder of experimental medicine and the most prominent ancient physician after Hippocrates, a good temperament could be damaged by eating too much, and a bad temperament could be corrected by eating enough. 22 He also distinguished between moderate and non‐moderate forms of obesity. In Galen's Asrar al‐nesa book) Women's Secrets: A book by Galen whose Arabic manuscript is available (drugs that were suitable for fattening and slimming the body were mentioned in a separate section). 23 A chapter of the book was dedicated to slimness and obesity, which shows the importance of body balance and fitness. 24 , 25 Tiazouq (physician of the sixth and seventh centuries AD) 26 advised the king of Iran, King Khosrow I, not to eat unless he really felt hungry and that there was nothing worse than eating without feeling hungry. Eating too much food is not recommended in any way and moderation is always encouraged.

Tarikh al‐Tabari is an Arabic language historical chronicle, completed by the Persian historian Muhammad ibn Jarir al‐Tabari (838−923 AD), which is one of the oldest Persian prose in which the fate of kings is mentioned. 27 The famous Sassanid king Khosrow II (seventh century AD) describes the characteristics of choosing a maid and wife in his letter, in which he also mentioned obesity as a criterion of beauty. 28

Al‐Harith ibn Kalada (seventh century AD) was a noble Arab who studied medicine in Iran (Gandhi Shapur University). 29 , 30 He was able to attract the attention of King Khosrow I 31 and served in the royal court. In response to the king's questions, Al‐Harith ibn Kalada considers abstinence as moderation in everything because eating more than necessary can have deleterious effects on the body. 32

With the conveyance of the Prophet Muhammad (seventh century AD) and the beginning of the Islamic era, a new approach was established in the field of medical history. 33 This period led to the formation of new compilations and books, including the book “Medicine of the Prophet.” 34 , 35 Muslims emphasized the importance of refraining from excessive eating, by referring to the verses of the Quran which broadly state “eat, drink, but do not cross the limit.” 36 Moreover, the hadiths of the Prophets and the Infallibles highlighted the importance of maintaining health and well‐being in relation to the manner of eating and drinking, and observing the necessary abstinence. 37 , 38 Iranian doctors always recommended moderation in eating and avoiding overeating in the court caliphs, who considered bodybuilding and fatness to be a sign of power and wealth. 39 Jirjis Ibn Bakhtishua, a Syriac doctor in Iran (eigthth century AD), 40 treated the stomach discomfort of the second Abbasid caliph, Al‐Mansur al‐‘Abbasi, with a proper diet and abstinence. 41 Jabril ibn Bukhtishu, another prominent doctor from the Bukhtishu family, said that “Drinking water when hungry is bad, eating when full is even worse” and “eating less of something harmful is better than eating more of something beneficial.” 42

In the ninth century AD, Ali ibn Sahl Rabban al‐Tabari 43 wrote the first comprehensive medical encyclopedia in Arabic, which benefited from Greek, Iranian, and Indian medical knowledge. 44 Tabari considered happiness, prosperity, and kingship, to be the causes of obesity, as well as thick food, a soft bed, sleeping after eating, and vomiting before eating. 45 , 46 According to traditional physicians, such as Ali ibn Sahl Rabban al‐Tabari, obesity results from having a comfortable life that is full of happiness and devoid of grief. 45 , 46 However, Iranian physicians such as Rhazes rejected the idea of using unhappiness as a method of losing weight. 47 , 48

In the ninth century, and during the beginning of the 10th century, masterpieces of Islamic medicine authored by Abu Bakr al‐Razi (Rhazes) emerged. 49 Rhazes is the greatest physician in Iran and the Islamic world. 50 , 51 Although he was one of the first to use the translated works of Galen and was inspired by his opinions and thoughts, he wrote a book criticizing Galen's thoughts, “The Doubt about Galen.” 52 , 53 He had a different point of view regarding the management of obesity to that of his predecessors, such as Hippocrates and Galen. For example, Galen believed that long thinking and mental activity made people thin, while Rhazes believed that long periods of thinking lead to sadness and grief. 47 As a clinician, he described the clinical reports of morbidly in patients with obesity and treated people with obesity by changing their lifestyle, diet, medicine, exercise regime, and introduced massage. 54 , 55

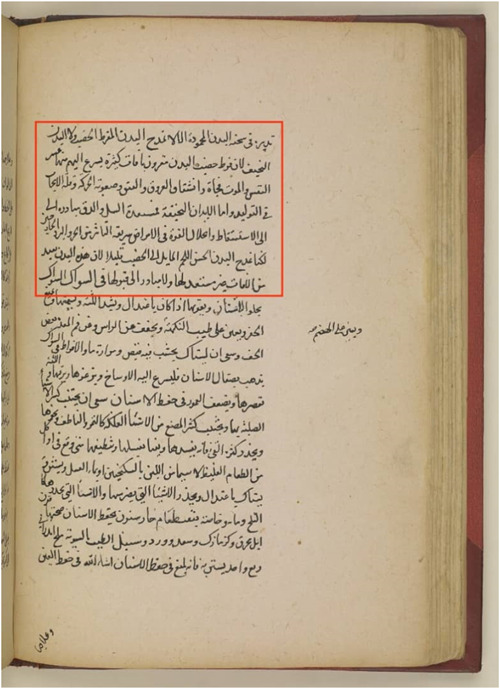

Rhazes wrote in his book “Al‐Mansouri” that we should not praise very healthy and fat or extremely thin bodies, because obesity causes diseases to flow to such bodies. 56 He says: “We praise the fleshy body, which is a little close to freshness because this body is not ready to accept diseases.” Interestingly Rhazes differentiates between two groups of fat bodies by giving separate definitions for each of them. According to him, one type of obesity is called Shahm, which is more like adipose tissue, and the other is called (Lahm) that is more like muscle mass, with the first group being considered an illness by Rhazes (Figure 1). In addition, Rhazes considers geographical conditions and the climate to be related to fattening factors. 47 , 57 For people who want to lose weight, he recommends avoiding high nutritional value foods, meat, sweets, wine, and milk. 47 , 58

Figure 1.

al‐Kitāb al‐Manṣūrī ا Rāzī, Abū Bakr Muḥammad ibn Zakarīyā [65v] (139/396), British library: oriental manuscripts, Or 5316, in Qatar Digital Library <https://www.qdl.qa/archive/81055/vdc_100023646252.0x00008c> [accessed September 17, 2022].

Al‐Akhawayni Bokhari wrote the book “Hidayat al‐Muta'allemin fi al‐tibb” (10th century AD), which is the oldest Persian document in the field of medicine. 59 , 60 In this book, the characteristics of people with obesity were described as “the person who is obese has a weak (impaired) spleen” and “The pulse of people with obesity is smaller, slower, and weaker than that of lean people.” 61 Of note, the association between obesity and splenomegaly has been extensively discussed by modern medicine. 62

Avicenna (10th century AD) was one of the greatest geniuses in the world, whose writings replaced the old books of Galen and Hippocrates and became the most important source of medicine being taught in medical schools for centuries. 61 , 63 Avicenna wrote a comprehensive medical encyclopedia entitled “The Canon of Medicine” in which he considered a healthy person to be somewhere between obesity and thinness. 64 He believed that obesity was worse than thinness and considered disproportionate and excessive obesity to be a disaster that has many disadvantages, such as restrictions in movement and a lack of flexibility. Obesity and congestion of the body tissues put pressure on the blood vessels and narrow the arteries and veins, hindering the movement of blood through the veins. The vasoconstriction, which occurs due to the obesity, makes it difficult for drugs to move and reach the place of pain, making it difficult to treat any pain. However, the mentioned idea is the opinion of ancient scientists and it has not been discussed or approved by modern medicine. In addition, breathing becomes short and difficult, and the associated shortness of breath causes an abnormal heartbeat. 65 , 66

Avicenna explained cardiovascular diseases in his Canon and wrote another book in the field of cardiovascular disease entitled “The Treatise on Cardiac Drugs” (Risala fi al‐Adwiyat al‐Qalbiyah). 67 , 68 In this book, Avicenna presented a brief explanation of heart disease. Finally, he mentions obesity as a predictor of the dissection of blood vessels and premature death. As the blood vessels of children with obesity are under more pressure they remain thin and narrow, and in adulthood, they are prone to stroke, paralysis, respiratory failure, intestinal and stomach disease, wheezing, fainting, and high‐degree fevers. Infertility, miscarriage, and abortion are other factors that are more common in people with obesity. 69 , 70

Hakim Yusefi (10th century AD) wrote in his book “Teb Yusefi” in the form of a poem: “If you are sick with obesity find a way to treat yourself. In this case, pleasure is not proper. You have got to forget about your comfort and solve this problem.” 71 , 72

The book Samak Ayar, written by Faramarz bin Khodadad bin Abdullah (11th century AD), is a famous folk story in the Persian language. 73 As the text of the book is simple and close to the language and culture of that period, it demonstrates the way that people thought during that period. Choosing an overweight woman, as the main character of the story did, shows that until this time overweight women were favored by society. 74 , 75

At the beginning of the 11th century, Zayn al‐Din Gorgani (Seyyed Esmaeel Jorjani) wrote Zakhireye Khwarazmshahi in Persian. 76 , 77 He divided people with obesity into two groups. The group whose obesity is due to a lot of muscle and the group that is due to a lot of fat. 78 He believes that in people with obesity, the blood vessels are narrow and hidden among the flesh, meaning that the prescribed drugs would not pass through the vessels and would not reach the intended organ. These problems led to difficulties in the treatment of diseases. 78 , 79

Mansur ibn Ilyas Shirazi (13th century AD) was a Persian physician who wrote the books Mansoori's description and Mansoori's Kefaye. 80 , 81 In Mansoori's Kefaye he described the six principles of maintaining health and provided instructions on how to eat and exercise, to maintain health and prevent obesity. 82 , 83

Baha al‐Dawlah Razi (15th century AD) is a doctor who was regarded as a genius in his own era. In his book, Summary of Experiences, he reported the opinions and experiences of doctors from ancient times up to the time the book was written. 84 , 85 He identified the weak pulse pressure in patients with obesity and the dangers of obesity, just like previous physicians. 86 , 87

Emad al‐Din Mahmud Shirazi (16th century AD) used opium to treat the excessive obesity of a person named Shah Ali Mirza, as written in his book Treatise on Opium. 88 , 89

Mohammad Akbar bin Mir Muqim, known as Shah Arzani (17th and 18th century AD), was one of the most knowledgeable physicians of that period, and he wrote in simple and easy‐to‐understand Persian. 90 In his book, Teb Akbari, which is a brief translation of Nafis Bin Awad Kermani's book “Description of Symptoms and Signs,” he stated seven possible risk factors for people with obesity: shortness of breath, fainting and stroke, rupture of a large vessel, fever, infertility in men and women, paralysis, and diarrhea. He also stated that the diseases that occur in people with obesity are more severe and difficult to treat. 91 , 92 Currently, we know there are several different mechanisms by which obesity can lead to infertility, including by impairing: ovarian follicular development, oocytes, fertilization, embryo development, and embryo implantation. 93

During the Qajar era (18th century) obesity reached its peak, to the point that people vomited to be able to eat more. 94 According to the writings of Carla Serena, an Italian traveler and writer, Qajar women were very fat and ate a lot of food. 95 Furthermore, as stated by al‐Dawlah, one of the wives of Naser al‐Din Shah Qajar, the fatter a woman was the dearer and closer she was to her husband. Fat women were accepted by society and thin women used different treatments to get fat, because thinness was a source of shame and despair. Among the medicines, camel's hump tallow was the most frequently prescribed, which had to be consumed every day at a certain time and in a certain quantity. Using photographs from this era, we are able to estimate the prevalence of morbid obesity and the social status of these groups of people.

At the beginning of the 19th century, with the arrival of foreign and modern magazines into Iran and the promotion of all kinds of posters and greeting cards, the images of thin women introduced new ideas of beauty into Iran and the community's view of obesity changed. Thereafter, obesity was considered to be a disorder which had to be treated. 96 , 97

Today, with the advancement of technology and changes in lifestyle and eating habits, obesity, and its comorbidities are increasing. 98 , 99 However, modern medicine has developed several different pharmacological and surgical options (e.g., lipase inhibitors and probiotics) for treating obesity. 100 The unpleasant feeling of being obese, reduced quality of life due to restricted mobility, respiratory problems, the side effects of drugs, and risks and the high cost of surgery have drawn people's attention to traditional medicine. 101 , 102 In the books of traditional medicine, they noted the difference in pulse between fat and thin people, examined the vessels, pattern of breathing, and provided the necessary tips for prevention and treatment. This all points to the fact that the sages of traditional medicine were well aware of the dangers of obesity and its complications. They also understood the relationship between obesity and other diseases, such as heart and respiratory diseases, as well as other major complications of obesity, including infertility and early death. Obesity is a chronic disease that takes time to cure. In the texts of traditional Iranian medicine, prevention is the first recommendation, and then lifestyle changes and treatment with simple herbal medicines were proposed. Implementing these recommendations together, in consultation with a doctor, can led to improvements. 103 , 104 Current systematic reviews have produced favorable results regarding the safety and efficacy of several Iranian herbal medicines for treating obesity. Herbal medicines containing Nigella sativa, green tea, puerh tea, Garcinia cambogia, Phaseolus vulgaris, Irvingia gabonensis, and Caralluma fimbriata have been shown to be effective for obesity management with a significant improvement in weight, BMI, waist circumference, or hip circumference. Moreover, flaxseed, fenugreek, spinach, and C. fimbriata were able to reduce appetite. 105 , 106

4. CONCLUSION

According to the review of the above material, obesity has always been one of the most important issues in the history of medicine. Throughout the traditional Iranian medical texts, from the seventh to the 20th centuries Anno Domini, physicians have made recommendations about maintaining an appropriate body weight. History shows us that obesity was mentioned as a criterion of beauty, but morbid obesity was never popular. The fact that obesity is a precursor to other diseases was also noted in all eras. The traditional medicine of Iran divides obesity into two groups, “Shahmi and Lahmi.” The second type was abdominal obesity which was considered to be an illness. The best treatment was prevention and a healthy lifestyle. The treatments for controlling and restricting obesity included paying attention to nourishment, mobility, and even the habitat. Furthermore, several ancient Iranian physicians recommended the use of massage and an exercise regime to reduce obesity, as well as avoiding excessive eating, sleeping after eating, and having a bed that was too soft. 107 , 108

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Somayeh Marghoub: Conceptualization; data curation; resources; writing—original draft; writing—review and editing. Sarvin Sanaie: Conceptualization; methodology; project administration; writing—original draft; writing—review and editing. Mark J. M. Sullman: Writing—original draft; writing—review and editing. Seyed Aria Nejadghaderi: Writing—original draft; writing—review and editing. Saeid Safiri: Conceptualization; investigation; methodology; project administration; supervision; validation; writing—original draft; writing—review and editing. Reza Mohammadinasab: Conceptualization; project administration; supervision; writing—review and editing.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

TRANSPARENCY STATEMENT

The lead author Saeid Safiri, Reza Mohammadinasab affirms that this manuscript is an honest, accurate, and transparent account of the study being reported; that no important aspects of the study have been omitted; and that any discrepancies from the study as planned (and, if relevant, registered) have been explained.

Marghoub S, Sanaie S, Sullman MJM, Nejadghaderi SA, Safiri S, Mohammadinasab R. Obesity from a sign of being rich to a disease of the new age: a historical review. Health Sci Rep. 2023;6:e1670. 10.1002/hsr2.1670

Contributor Information

Saeid Safiri, Email: saeidsafiri@gmail.com.

Reza Mohammadinasab, Email: rmn.nasab@gmail.com.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

No new data was generated.

REFERENCES

- 1. Brown PJ. Culture and the evolution of obesity. Hum Nat. 1991;2:31‐57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Bray GA. History of obesity. Obesity: Sc Practice. 2009;1:1‐18. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Sobal J, Stunkard AJ. Socioeconomic status and obesity: a review of the literature. Psychol Bull. 1989;105:260‐275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Cawley J, ed. The Oxford Handbook of the Social Science of Obesity. Oxford University Press; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Gilman SL. Fat: A Cultural History of Obesity. Wiley; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Bleeck AH. Avesta: The Religious Books of the Parsees. Creative Media Partners, LLC; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Kinlen D, Cody D, O'Shea D. Complications of obesity. QJM. 2018;111:437‐443. 10.1093/qjmed/hcx152 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Cassell JA. Social anthropology and nutrition. J Am Diet Assoc. 1995;95:424‐427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Renzaho AM. Fat, rich and beautiful: changing socio‐cultural paradigms associated with obesity risk, nutritional status and refugee children from sub‐Saharan Africa. Health Place. 2004;10:105‐113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Stunkard A, LaFleur W, Wadden T. Stigmatization of obesity in medieval times: Asia and Europe. Int J Obes. 1998;22:1141‐1144. 10.1038/sj.ijo.0800753 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. West EW. Menog I Khrad the Spirit of Wisdom. Kessinger Publishing; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 12. West EW, Müller FM. Pahlavi Texts. Clarendon Press; 1897. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Tabrizi JS, Sadeghi‐Bazargani H, Farahbakhsh M, Nikniaz L, Nikniaz Z. Prevalence and associated factors of overweight or obesity and abdominal obesity in Iranian population: a population‐based study of Northwestern Iran. Iran J Publ Health. 2018;47:1583‐1592. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Ezzeddin N, Eini‐Zinab H, Ajami M, Kalantari N, Sheikhi M. WHO ending childhood obesity and Iran‐ending childhood obesity programs based on urban health equity indicators: a qualitative content analysis. Arch Iran Med. 2019;22:646‐652. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Haslam D. Weight management in obesity–past and present. Int J Clin Pract. 2016;70:206‐217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Muscaritoli M, Anker SD, Argilés J, et al. Consensus definition of sarcopenia, cachexia and pre‐cachexia: joint document elaborated by Special Interest Groups (SIG)“cachexia‐anorexia in chronic wasting diseases” and “nutrition in geriatrics”. Clin Nutr. 2010;29:154‐159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Kleisiaris CF, Sfakianakis C, Papathanasiou IV. Health care practices in ancient Greece: the Hippocratic ideal. J Med Ethics Hist Med. 2014;7:6. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Bray GA. Obesity: historical development of scientific and cultural ideas. Int J Obes. 1990;14:909‐926. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Balke H, Nocito A. Vom Schönheitsideal zur Krankheit–eine Reise durch die Geschichte der Adipositas. Praxis. 2013;102:77‐83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Ozcan Dag Z, Dilbaz B. Impact of obesity on infertility in women. J Turk Ger Gynecol Assoc. 2015;16:111‐117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Norman RJ, Clark AM. Obesity and reproductive disorders: a review. Reprod Fertil Dev. 1998;10:55‐63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Papavramidou NS, Papavramidis ST, Christopoulou‐Aletra H. Galen on obesity: etiology, effects, and treatment. World J Surg. 2004;28:631‐635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Flemming R. Medicine and the Making of Roman Women: Gender, Nature, and Authority from Celsus to Galen. Oxford University Press; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Brooke E. Women Healers Through History: Revised and Expanded Edition. Aeon Books; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Hankinson RJ, ed. The Cambridge Companion to Galen. Cambridge University Press; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Afridi MMRK, Navaid MI. Encyclopaedia of Quranic Studies: Fundamentals Under Quran. Anmol Publications Pvt. Limited; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Division IDPR. The Biography of Muhammad Ibn Jarir al‐Tabari. Islamic Digital Publishing; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Yarshater E. Set—History of al‐Tabari: Volumes 1‐40 (Includes Index). State University of New York Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Montgomery SL. Science in Translation: Movements of Knowledge Through Cultures and Time. University of Chicago Press; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 30. O'Leary D. How Greek Science Passed on to the Arabs. Taylor & Francis; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Motamedmanesh M, Royan S. Khosrow II (590–628 CE). Encyclopedia. 2022;2:937‐951. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Bynum WF, Porter R. Companion Encyclopedia of the History of Medicine. Taylor & Francis; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Ullmann M. Islamic medicine. Islamic Medicine. Edinburgh University Press; 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 34. Pormann PE, Savage‐Smith E. Medieval Islamic Medicine. Edinburgh University Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 35. Al‐Rumkhani A, Al‐Razgan M, Al‐Faris A. TibbOnto: knowledge representation of prophet medicine (Tibb Al‐Nabawi). Procedia Computer Science. 2016;82:138‐142. [Google Scholar]

- 36. Farid‐ul‐Haque PS. Quran English Translati̇on. Ahmet Özdemir. [Google Scholar]

- 37. Koenig HG, Al Shohaib S. Health and Well‐being in Islamic Societies. Springer; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 38. Amer MM. Islam and health. Better Health through Spiritual Practices: A Guide to Religious Behaviors and Perspectives that Benefit Mind and Body. Bloomsbury Publishing; 2017:183. [Google Scholar]

- 39. Albala K. Eating right in the Renaissance. Eating Right in the Renaissance. University of California Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 40. Rashed R. Encyclopedia of the History of Arabic Science. Taylor & Francis; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 41. Elgood C. A Medical History of Persia and the Eastern Caliphate: From the Earliest Times Until the Year A. D. 1932. Cambridge University Press; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 42. Ragab A. The Medieval Islamic Hospital: Medicine, Religion, and Charity. Cambridge University Press; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 43. Anwar Z, Zahra K. Ali‐ibn‐Sahl Rabban al‐Tabari. International Journal of Pathology. 2018;14:93‐94. [Google Scholar]

- 44. Meyerhof M. 'Alî at‐Tabarî's “Paradise of Wisdom”, one of the oldest Arabic compendiums of medicine. Isis. 1931;16:6‐54. [Google Scholar]

- 45. Al‐Ṭabarī AiSR, Siggel A. Die propädeutischen Kapitel aus dem Paradies der Weisheit über die Medizin des’ Ali b. Sahl Rabban aṭ‐Ṭabarī. Verlag der Akad. der Wiss. und der Literatur, 1953.

- 46. Al‐Tabari A. Firdous al‐Hikmah. In: Seddiqi MZ, ed. Berlin: Matbae Aftab, 1928:425‐432. [Google Scholar]

- 47. Al‐Razi MZ. Kitab Al‐hawi fi l‐tibb: (Continens of Rhazes…: An Encyclopaedia of Medicine). Osmania Oriental Publications Bureau; 1955. [Google Scholar]

- 48. Razi Z. Kitab al Hawi. CCRUM; 2004:75‐171. [Google Scholar]

- 49. Edriss H, Rosales BN, Nugent C, Conrad C, Nugent K. Islamic medicine in the middle ages. Am J Med Sci. 2017;354:223‐229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Kara Rogers BS. Medicine and Healers Through History. Britannica Educational Publication; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 51. Robinson F, Lapidus IM. The Cambridge Illustrated History of the Islamic World. Cambridge University Press; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 52. Tubbs RS, Shoja MM, Loukas M, Oakes WJ. Abubakr Muhammad Ibn Zakaria Razi, Rhazes (865–925 AD). Childs Nerv Syst. 2007;23:1225‐1226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Shoja M, Agutter P, Tubbs R. Rhazes doubting Galen: ancient and medieval theories of vision. Int J Hist Philos Med. 2015;5:10510. [Google Scholar]

- 54. Saad B, Zaid H, Shanak S, et al. Anti‐diabetes and anti‐obesity medicinal plants and phytochemicals. Anti‐diabetes and Anti‐obesity Medicinal Plants and Phytochemicals: Safety, Efficacy, and Action Mechanisms. 2017:59‐93. [Google Scholar]

- 55. Ligon BL. Biography: Rhazes: his career and his writings. Seminars in Pediatric Infectious Diseases. Elsevier; 2001:266‐272. [Google Scholar]

- 56. Al‐Nadīm MII, Flügel G, Roediger J, et al. Kitâb al‐Fihrist. F. C. W. Vogel; 1872. [Google Scholar]

- 57. Najmʹābādī M. Histoire de la médécine de l'Iran. Chāp‐i Hunarbakhsh; 1962. [Google Scholar]

- 58. Rāzī ABMiZ . al‐Kitāb al‐Manṣūrī British library: Oriental manuscripts, Or 5316, in Qatar Digital Library; 1960.

- 59. Yarmohammadi H, Dalfardi B, Ghanizadeh A. Al‐Akhawayni Bukhari (?–983 AD). J Neurol. 2014;261:643‐645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Ghazi Sha'rbaf J, Seyyedi SM, Mohammadinasab R. Investigating the content of the first Iranian medical book in Persian: “Hidayat al‐Muta'allemin fi al‐Tibb”. Journal of Research on History of Medicine. 2021;10:25‐34. [Google Scholar]

- 61. Matini J. Hidayat al‐Mutaallimin fi al‐Tibb by Abubakr Rabi ibn Ahmad al‐Akhawayni al‐Bukhari. Mashhad University Press, Mashhad; [in Persian]; 1965. [Google Scholar]

- 62. Abd El‐Aziz R, Naguib M, Rashed LA. Spleen size in patients with metabolic syndrome and its relation to metabolic and inflammatory parameters. Egyptian J Internal Med. 2018;30:78‐82. [Google Scholar]

- 63. Ghaffari F, Taheri M, Meyari A, Karimi Y, Naseri M. Avicenna and clinical experiences in Canon of medicine. J Med Life. 2022;15:168‐173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Masic I. Thousand‐year anniversary of the historical book: “Kitab al‐Qanun fit‐Tibb”‐The Canon of Medicine, written by Abdullah ibn Sina. J Res Med Sci. 2012;17:993‐1000. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Avicenna . The Canon of medicine (al‐Qānūn Fī'l‐ṭibb) (the Law of Natural Healing): Systemic diseases, orthopedics and cosmetics. Great Books of the Islamic World. 2014.

- 66. Avicenna H. Al‐Qanon fi al‐Tibb (Canon on Medicine). Vol 2. Alalami Library Publication; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 67. Chamsi‐Pasha MAR, Chamsi‐Pasha H. Avicenna's contribution to cardiology. Avicenna J Med. 2014;04:9‐12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Choopani R, Mosaddegh M, Gir AAG, Emtiazy M. Avicenna (Ibn Sina) aspect of atherosclerosis. Int J Cardiol. 2012;156:330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Siahpoosh MB, Nejatbakhsh F. Avicenna aspect of cardiac risk factors. 2013. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 70. Choopani R, Emtiazy M. The concept of lifestyle factors, based on the teaching of avicenna (ibn sina). Int J Prev Med. 2015;6:30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Mobli M, Hamedi S, Memariani Z, et al. Hakim Yousefi and Riyaz al‐Adviyye. J Islamic Iranian Traditional Med. 2012;3:377‐381. [Google Scholar]

- 72. Pakhouh HK, Feyzabadi Z, Khodabakhsh M, et al. An overview of the life and works of famous Iranian traditional medicine and Islam in Khorasan. Med Hist. 2016;8:37‐46. [Google Scholar]

- 73. Kakahkhani D, Ahmadi J, Qavami B. Surey slangly elementd in Samak‐e‐ayyar. 2020.

- 74. Rassouli F, Mechner J. Samak the Ayyar: A Tale of Ancient Persia. Columbia University Press; 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 75. Zabihnia Emran A. Analysis of women veiling culture in the popular Samak‐E‐Ayar Tales. Sci Res Quarterly WomanCulture. 2017;9:51‐61. [Google Scholar]

- 76. Hosseini SF, Alakbarli F, Ghabili K, Shoja MM. Hakim Esmail Jorjani (1042–1137 ad): Persian physician and jurist. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2011;284:647‐650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Zarshenas MM, Zargaran A, Abolhassanzadeh Z, Vessal K. Jorjani (1042–1137). J Neurol. 2012;259:2764‐2765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Zakhireye SIJ. Khwarazmshahi. Zakhireye Kharazmshahi. 2012:10. [Google Scholar]

- 79. Roshandel HRS, Ghadimi F, Roshandel RS. Developing and standardization of a structured questionnaire to determine the temperament (Mizaj) of individuals. 2016.

- 80. Daneshfard B, Sadr M, Abdolahinia A, et al. Mansur ibn Ilyas Shirazi (1380–1422 AD), a pioneer of neuroanatomy. Neurol Sci. 2022;43:2883‐2886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Zarshenas MM, Zargaran A, Mehdizadeh A, Mohagheghzadeh A. Mansur ibn Ilyas (1380–1422 AD): a Persian anatomist and his book of anatomy, Tashrih‐i Mansuri. J Med Biogr. 2016;24:67‐71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Kefaye M. Iran University of Medical Sciences Tehran. 2003.

- 83. Alam MT, Sheerani F, Aslam M. Concept of temperament: a review.

- 84. Golshani SA, Ghafouri Z, Hakimipour A. Baha'al‐Dawlah Razi (860‐912 AH), the innovator surgeon, empiricist physician and pioneer in immunology. J Res History Med. 2012;1:1. [Google Scholar]

- 85. Seyyed Alireza G, Ziba G, Akbar H. [Baha'al‐Dawlah Razi [860‐912 AH], the innovator surgeon, empiricist physician and pioneer in immunology]. 2012.

- 86. Asadi MH, Changizi‐Ashtiyani S, Latifi AH, et al. A review of the role and importance of swaddling in Persian medicine. Int J Pediatr. 2018;6:8495‐8506. [Google Scholar]

- 87. Razi B. Kholasat al‐Tajarob [a summary of experiences in medicine]. Tehran: Tehran University of Medical Sciences. 2011.

- 88. Moosavyzadeh A, Ghaffari F, Mosavat SH, et al. The medieval Persian manuscript of Afyunieh: the first individual treatise on the opium and addiction in history. J Integ Med. 2018;16:77‐83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Soleymani S, Zargaran A. A historical report on preparing sustained release dosage forms for addicts in medieval Persia, 16th century AD. Substance Use & Misuse. 2018;53:1726‐1729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Zare F, Nimrouzi M, Shahriari M. The curative role of bitumen in traditional Persian medicine. Acta medico‐historica Adriatica. 2018;16:283‐292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Velayati A. An introduction to the history of medicine in Islam and Iran. Medical J Islamic Republic of Iran (MJIRI). 1988;2:131‐136. [Google Scholar]

- 92. Nimrouzi M, Zarshenas MM. Management of anorexia in elderly as remarked by medieval Persian physicians. Acta medico‐historica Adriatica: AMHA. 2015;13 Suppl 2:115‐128. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93. Jungheim ES, Travieso JL, Hopeman MM. Weighing the impact of obesity on female reproductive function and fertility. Nutr Res. 2013;71:S3‐S8. 10.1111/nure.12056 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94. Dezhamkhooy M. From moon‐faced amrads to farangi‐looking women: beauty transformations from the 19th to early 20th century in Iran. Beautiful Bodies: Gender Corporeal Aesthetics Past. 2022:263. [Google Scholar]

- 95. Carnoy‐Torabi DM. Adèle Hommaire de Hell et Carla Serena en Perse Qajare: Des récits de Voyage “Genrés”? Recherches en Langue et Littérature Françaises. 2021;15:43‐57. [Google Scholar]

- 96. Garrusi B, Garousi S, Baneshi MR. Body image and body change: predictive factors in an Iranian population. Int J Prev Med. 2013;4:940‐948. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97. Niya NM, Kazemi M, Abazari F, et al. Personal motivations of Iranian men and women in making decision to do face cosmetic surgery: a qualitative study. Electronic J General Med. 2018;15. [Google Scholar]

- 98. O'brien PE, Dixon JB, Brown W. Obesity is a surgical disease: overview of obesity and bariatric surgery. ANZ J Surg. 2004;74:200‐204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99. Aronne LJ. Obesity as a disease: etiology, treatment, and management considerations for the obese patient. Obesity. 2002;10:95S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100. Morales Camacho WJ, Molina Díaz JM, Plata Ortiz S, Plata Ortiz JE, Morales Camacho MA, Calderón BP. Childhood obesity: aetiology, comorbidities, and treatment. Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 2019;35:e3203. 10.1002/dmrr.3203 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101. Hasani‐Ranjbar S, Nayebi N, Larijani B, Abdollahi M. A systematic review of the efficacy and safety of herbal medicines used in the treatment of obesity. World J Gastroenterol. 2009;15:3073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102. Chandrasekaran CV, Vijayalakshmi MA, Prakash K. Herbal approach for obesity management. Am J Plant Sci. 2012;2012:1003‐1014. [Google Scholar]

- 103. Abolhasanzadeh Z, Shams M, Mohagheghzadeh A. Obesity in Iranian traditional medicine. J Islamic Iranian Traditional Med. 2017;7:375‐383. [Google Scholar]

- 104. Bahmani M, Eftekhari Z, Saki K, Fazeli‐Moghadam E, Jelodari M, Rafieian‐Kopaei M. Obesity phytotherapy: review of native herbs used in traditional medicine for obesity. J Evidence‐Based Complementary Altern Med. 2016;21:228‐234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105. Hasani‐Ranjbar S, Nayebi N, Larijani B, Abdollahi M. A systematic review of the efficacy and safety of herbal medicines used in the treatment of obesity. World J Gastroenterol. 2009;15:3073‐3085. 10.3748/wjg.15.3073 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106. Payab M, Hasani‐Ranjbar S, Shahbal N, et al. Effect of the herbal medicines in obesity and metabolic syndrome: a systematic review and meta‐analysis of clinical trials. Phytother Res. 2020;34:526‐545. 10.1002/ptr.6547 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107. Shakeri A, Hashempur MH, Beigomi A, et al. Strategies in traditional Persian medicine to maintain a healthy life in the elderly. J Complemen Integ Med. 2020;18:29‐36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108. Tabarrai M, Motaharifard MS, Shirbeigi L, Alipour R, Paknejad MS. Physical activity and exercise recommendations for children in Persian medicine: a narrative review. J Pediatr Rev. 2020;8:247‐254. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

No new data was generated.