Abstract

Objectives

The objective of this review is to (1) identify barriers and facilitators with respect to women’s health services at a primary care level based on a systematic review and narrative synthesis and (2) to conclude with recommendations for better services and uptake.

Design

Systematic review and narrative synthesis.

Data sources

PubMed, BMC Medicine, Medline, CINAHL and the Cochrane Library. Grey literature was also searched.

Eligibility criteria

Qualitative, quantitative and mixed studies were included in the review.

Data extraction and synthesis

The search took place at the beginning of June 2021 and was completed at the end of August 2021. Studies were included in the review based on the Sample, Phenomenon of Interest, Design, Evaluation, Research type criteria. The quality of the included studies was assessed using the Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool. Data were synthesised using a narrative synthesis approach.

Results

A total of 33 studies were included in the review. We identified six barriers to the delivery of effective primary healthcare for women’s health which have been organised under two core themes of ‘service barriers’ and ‘family/cultural barriers’. Ten barriers to the uptake of primary healthcare for women have been identified, under three core themes of ‘perceptions about healthcare service’, ‘cultural factors’ and ‘practical issues’. Three facilitators of primary healthcare delivery for women were identified: ‘motivating community health workers (CHWs) with continued training, salary, and supervision’ and ‘selection of CHWs on the basis of certain characteristics’. Five facilitators of the uptake of primary healthcare services for women were identified, under two core themes of ‘development of trust and acceptance’ and ‘use of technology’.

Conclusions

Change is needed not only to address the limitations of the primary healthcare services themselves, but also the cultural practices and limited awareness and literacy that prevent the uptake of healthcare services by women, in addition to the wider infrastructure in terms of the provision of financial support, public transport and child care centres.

PROSPERO registration number

CRD42020203472.

Keywords: systematic review, health policy, primary health care

STRENGTHS AND LIMITATIONS OF THIS STUDY.

The Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool was used to assess the quality of the included studies.

Narrative synthesis allowed us to analyse heterogeneous data from qualitative, quantitative and mixed-methods research.

The search strategy was limited to the English language and barrier and facilitators to delivery and uptake at primary level. We did not include studies of the tertiary sector, which may have contained relevant information about liaison with primary care.

Introduction

Pakistan has an estimated population of 112 million women,1 the majority of whom are poor2 and do not have access to out-of-pocket expenses for health.3 Achieving the health-related Sustainable Development Goals is not possible without full coverage of this population by a comprehensive set of primary healthcare services and equitable health access for all women.4 The state-run primary health services for women are managed by women community health workers (CHWs), which includes: (1) lady health workers (LHWs) and female health visitors, (2) community midwives (CMWs) and (3) traditional birth attendants (TBAs). The main services that LHWs provide include family planning, maternal and reproductive health services, vaccination and counselling. CMWs are trained by the government for a few months and are then free to practice privately; whereas TBAs are also trained briefly for safe delivery, provided with safe delivery packages and are then free to practice privately within the community. The main investment in recruitment to date has been for the LHW programme, with approximately 110 000 deployed across the country, followed by 5000–6000 CMWs.5 There are no estimates of how many TBAs have been trained by the state. LHWs are delivered at community basic health units (BHUs) or rural health centres (RHCs), but also serve clients directly on their door-step. Similarly, CMWs and TBAs provide door-to-door services.

Although the LHW programme is considered a success in improving contraception uptake and supporting reproductive health,6 7 on the whole maternal health indicators in the country are still unsatisfactory.8 This reflects a number of structural problems in terms of both the delivery and uptake of primary healthcare services including the fact that the overall health budget for Pakistan is less than 0.8% of gross domestic product.9 Other known barriers to the delivery of effective primary healthcare services in developing regions include: (1) a lack of training for health professionals with significant skills gaps,10 (2) low allocation of funds for identified priorities11 and (3) inadequate service planning and delivery.12 Other problems such as insufficient incentivisation, staffing shortages, inadequate supplies and unfavourable work environments also represent significant barriers to delivery.13 14

In addition to the LHW programme, the Sehat Sahulat Programme was launched in Pakistan to provide a health card to poor populations, and covers hospitalisation costs up to PKR460 000/US$2076.75 per year,15 and universal health coverage in the Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (KPK) province.16 Although, the programme claims to have benefited 7.2 million families, there is no evidence about outreach to women beneficiaries, or plans to scale up the programme for the wider population of women in Pakistan.

In terms of uptake, one of the major problems is that women have little autonomy as regards the decision to use primary care services and very little knowledge about the importance of health-seeking.17 Many women, especially younger and unmarried women, do not have permission from the family to access primary healthcare services,17 and when women do have permission, they are hampered from doing so by distance, lack of time and domestic burdens.18 For specific health problems such as family planning and mental health, women face considerable barriers due to stigmatisation and religious beliefs, compelling them to either abandon their healthcare needs or to seek services from faith healers.19 In addition to cultural restrictions, there is also a lack of trust and acceptance of physicians and CHW, contributing to significant barriers to uptake of health services.20 21 Conversely, known facilitators of primary healthcare service uptake in conservative regions include: (1) health provider communication and nativity22 and (2) social support and encouragement from significant others.19

Aim of the review

Ultimately, primary healthcare services are central to improving the health and well-being of the women of Pakistan and improving preventive health practices. Identifying the known barriers and facilitators to primary healthcare is vital in order to enable prudent planning and reform for the health sector.23 Although research on the barriers and facilitators to the uptake and delivery of primary care services for women in Pakistan has developed apace over the past decade, there are currently no systematic reviews that have synthesised this literature. Therefore, the aim of this study is to systematically review barriers and facilitators to the delivery of primary healthcare services for women in Pakistan and to advise recommendations for improved services.

Methods

Search strategy

A systematic review and narrative synthesis was undertaken. The following electronic databases were searched: PubMed, BMC, Medline, CINAHL and Cochrane Library. The grey literature search was conducted using the following databases: Google, Google Scholar, WHO website and Government of Pakistan Health Ministry websites. Detailed information about the search strategy, search terms, inclusion and exclusion criterion, and methods for this study can be found in the published protocol.24 A summary of the search terms and database search results can be found in online supplemental file 1. The search was initiated at the beginning of June 2021 and was completed at the end of August 2021. All published data prior to August 2021 was searched.

bmjopen-2023-076883supp001.pdf (36.9KB, pdf)

In accordance with the stated eligibility criteria, studies were included in the review based on the following criteria which have been formulated using the Sample, Phenomenon of Interest, Design, Evaluation, Research type framework25: (1) Sample: women using primary healthcare services or providers of primary healthcare to women in the community; (2) Phenomenon of Interest: primary healthcare service delivery for women. Studies not at primary or community level, or including analysis at tertiary level, were excluded; (3) Design: published literature in peer-reviewed academic journals and with a clearly stated research design; (4) Evaluation: identification of the barriers and facilitators to the delivery of primary healthcare services; (5) Research type: qualitative, quantitative and mixed studies were included in the review. Interventions, case–control studies and prospective studies were excluded from this review. Language was restricted to English.

Initial screening

An initial screening of studies was undertaken by the lead investigator for this study based on titles. In the second screening, titles and abstracts were evaluated.

Data extraction

The following information was abstracted by SRJ and reviewed by JB from the studies that met our study criteria: study design, setting, participant type, sample size, aim, barriers and facilitators.

Critical appraisal

The quality of the articles was assessed using the Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT) by SRJ and reviewed by JB.26 All the studies had a high MMAT score, except two studies, which were of medium quality. These studies (one mixed methods and one quantitative) were poorly written and had weak data analysis, but they were included in the review as they had clearly identified barriers and facilitators to delivery. The appraisal of the included studies has been summarised in online supplemental file 2.

bmjopen-2023-076883supp002.pdf (66.4KB, pdf)

Data synthesis

Studies from databases were transferred into EndNotes Software. After exclusion of duplicates, studies were transferred to an Excel template for data extraction and organisation of data. Following the final selection of included studies, separate tabs were created for organisation in the following steps: step 1—extraction of study characteristics; step 2—extraction of barriers and facilitators from each study and step 3—grouping of barriers and facilitators under common and similar codes to create overarching themes. A detailed summary of the data extracted in terms of the individual barriers and facilitators identified by each study are reported in online supplemental file 3. The preliminary narrative synthesis was undertaken independently by the lead author and then discussed and agreed with the second author. To further minimise bias, findings were discussed with the following health experts: three female medical physicians with experience in community health and public health services; two currently practising LHWs; and three officers from the Primary and Secondary Healthcare Department, Punjab. Everyone was in agreement with the findings.

bmjopen-2023-076883supp003.pdf (98.8KB, pdf)

Patient and public involvement

No patient or public was involved in this study. This study is a systematic literature review.

Results

Study characteristics

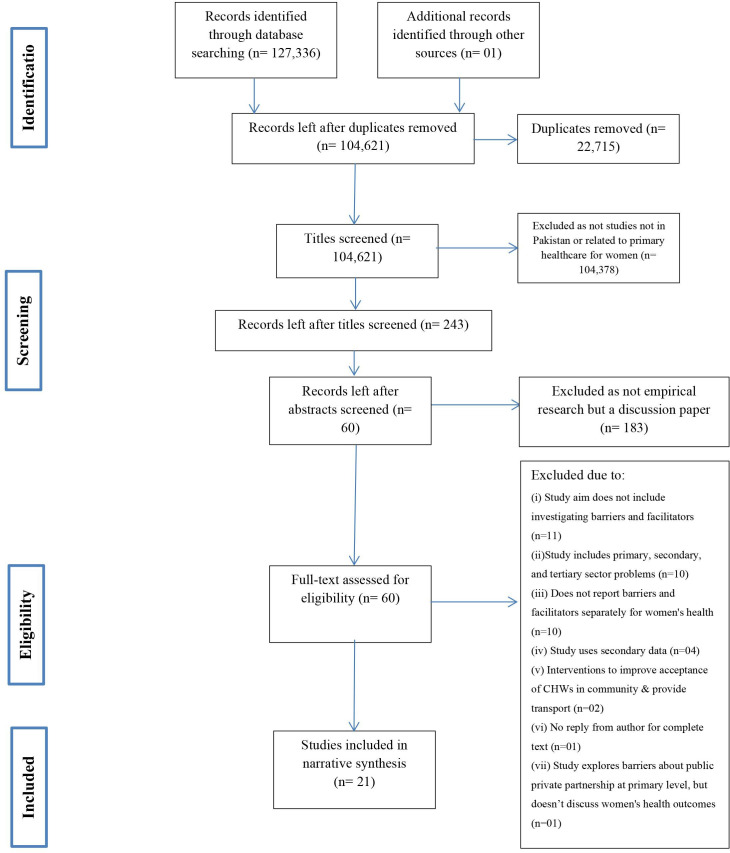

A total of 127 337 publications were identified, of which 22 715 were duplicates. After duplicates were removed 104 621 hits remained and were screened based on their titles. All studies not related specifically to Pakistan were removed and a review of the abstracts of 243 publications was undertaken. Twenty-one studies met all the study criteria and were included in the review. The search results and details have been reported using the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses flow chart, presented in figure 1.

Figure 1.

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses flow chart. CHWs, community health workers.

Included studies were published between the years 2003 and March 2021, of which: (1) 3 studies included both qualitative and quantitative data—mixed-method studies; (2) 16 studies included qualitative data and (3) 2 studies included only quantitative data. Online supplemental file 4 includes information about the complete study citation, research design, study aim, sampled participants and the setting of the data collection. The included studies described barriers and facilitators from the perspective of the following groups: (1) LHWs alone (n=1); (2) women clients and different CHWs (n=02); (3) women clients and spouse (n=02); (4) women alone (n=03); (5) women, spouse and CHWs (n=03); (6) CHWs and district-level managers of primary health and maternal health programme (n=04) or (7) women, their family members (husband, mothers-in-law), healthcare providers (HCPs) and CHWs (n=06).

bmjopen-2023-076883supp004.pdf (66.7KB, pdf)

A majority of the studies sampled participants from one city or district town (n=10). Five studies sampled participants from multiple districts or cities within one province, while another five studies sampled multiple districts from two provinces. One study was nationally representative and collected data from multiple districts across all four provinces of the country. Whereas, nine, eight and seven of the studies collected data from Sindh, Punjab and KPK provinces, respectively. Only one study collected data from Balochsitan. There was no sampling or representation in the included studies for the province of Gilgit Baltistan or the Pakistan administered Azad Kashmir.

Barriers to the delivery of primary healthcare services

Barriers to delivery

We identified six barriers to the delivery of effective primary healthcare services for women’s health, which have been organised under two core themes: (1) Service barriers—(a) inadequate training; (b) centre unresponsiveness and inefficient monitoring; (c) employment and contractual problems; (d) BHU provider teamwork and communication problems and (e) distance and coverage. (2) Family/cultural barriers—(f) family restrictions including perceptions about safety and work–family conflict in CHWs.

Service barriers

Inadequate training

TBAs who are young and inexperienced were perceived to have insufficient understanding about treatment management and to be in need of more comprehensive and ongoing training to deliver services.27 Similarly, village-based family planning volunteers who are deployed after just 7 months of preparation, were perceived to have been insufficiently well trained to deal with other maternal health issues with which clients requested help.28 The LHWs who received a longer period of training (ie, 15 months) were also perceived to be insufficiently well trained and lacking ongoing support in terms of having up-to-date information about the health needs of women.28 Other training needs that were identified included managing client records efficiently in terms of facilitating coordination with other HCPs.28 CMWs themselves felt that although their theoretical knowledge was sound, they needed more practical training for skill development and for ongoing lectures to be more regular and conducted in their local language (ie, not in the English language).29

Centre unresponsiveness and inefficient monitoring

There was perceived to be inadequate support from the district health department that supplies resources and supervises the BHUs, and problems were identified relating to a lack of response and support from the centre. First, there was felt to be a lack of or shortage of supplies and major delays in their delivery,29–31 specifically for family planning supplies32 and injectables.33 Second, an inefficient response for referrals to the secondary and tertiary care providers was identified,29 31 34 which prevents or significantly delays services for critical health needs, including mental health.35 Other studies confirmed an absence of response to requests for information and updated knowledge to support women’s health needs28 30 36 and requests for much needed resources, supplies and training to provide services for emergency obstetric care, female adolescent health and teenage pregnancies.28

Lack of monitoring and inefficient policy-making from the centre was also perceived to result in many of the HCPs working at the BHU setting up private facilities, thus compromising their service delivery and ethics.36 This was felt to be due to the fact that HCPs are perceived to have low attendance at the BHUs when they engage in dual practices, and that they also pay less attention to public sector clients and try to coerce them to visit the private facilities to gain remuneration. Although CMWs have been trained by the district health office, they are not monitored for active practice, and one study reports that only eight out of the 38 CMWs sampled are active providers in the community.7 Lack of monitoring and quality services have led to significant under-utilisation of public facilities, with many women clients opting for private healthcare services if they can afford it, or choosing local and cheap providers or home remedies for the relief of health problems.37

Employment and contractual problems

BHU providers described facing significant employment problems causing a great deal of stress and job insecurity.36 Many CHWs complained of a lack of role clarity and difficulty in understanding the range of services they are expected to provide.36 The BHU providers, especially the LHWs and CMWs described receiving very low salaries, which in turn was felt to adversely affect their job commitment and satisfaction levels.29 36 Some interviewees described staff as being underpaid31 36 and being paid irregularly due to mismanagement or fund release issues from the centre,28 31 forcing staff to take on other jobs or small contracts to make ends meet. Staffing shortages and an overwhelming workload, were perceived by many CHWs as preventing them from providing the range of services expected.28 33 36 In addition, excessive workload was also described as preventing them from delivering services to their entire caseload, or the need to deliver infrequent, rushed and suboptimal door-to-door services.38

BHU provider teamwork and communication problems

The BHU team described an absence of teamwork and communication problems as preventing them from delivering services based on coordinated planning and effective feedback.36 Conflict and improper power distribution were also highlighted, leading to an unwillingness to communicate and work together for patient management and care plan development.36 Women HCPs working at the BHU described disrespect from male colleagues.31

Distance and coverage

BHU locations are expected to cover a large population area, up to 25 000 people in one community, creating challenges for CHWs in reaching and delivering door-to-door services to women clients who are living far from the BHU.38 39 Similarly, women clients are described as being less likely to visit distant BHUs, as the majority do not have time for travel, or transport facilities are not available.17 Some women clients who have to pay for transport and travel long distances for primary healthcare, end up opting for private facilities or then visiting tertiary care services instead, as they believe their time and finances are better spent on services that provide them with better quality care.40

Family/cultural barriers

Family restrictions included perceptions about safety and work–family conflict in CHWs

Specifically, CMWs described restrictions from family members in delivering services, including visiting the home of clients as part of home delivery of services.30 A number of family members, including the spouse and in-laws, were described as preventing the CMWs from continuing practice or delivering services. CMWs also described being prevented by family members from travelling long distances within the community and from continuing work during their own pregnancies. This was perceived to make the development of trust and the provision of a continuum of care with clients difficult for CMWs. LHWs also described the conflict between family and work responsibilities, explaining how not attending family gatherings due to work was not regarded as being culturally acceptable and led to breaks in family ties and estranged relations with family members.31

CMWs complained that they were either prevented by their family from travelling alone and travelling after dusk due to concerns by male partners about their safety and security,30 33 especially during emergencies30; alternatively, they were required to be accompanied by their father or husband.31 This was more frequently referred to by CMWs from underserved regions, with less patrols and higher crime rates.

Barriers to uptake

Ten barriers to the uptake of primary healthcare for women were identified, under three core themes: (1) Perceptions about healthcare service—(a) preference for traditional services; (b) mistrust of biomedically based services; (c) perceptions about provider inefficiency; (d) low health literacy. (2) Cultural factors—(e) decision-making in families; (f) stigma and cultural disapproval; (g) role of religion; (h) chaperoning issues. (3) Practical issues—(i) transport, time and finances.

Perceptions about healthcare service

Preference for traditional services

Women were viewed as preferring to receive services from traditional providers within the community, who are known to them and accepted by their family and in-laws.30 Local providers and TBAs are trusted for being experienced, having delivered the children of relatives and neighbours and being a part of the community, despite their lack of licensing; they are also accepted as skilled and empathetic providers.31 Many women were also perceived to prefer the TBA, as there is no requirement for prenatal checkups and registration, and the TBAs can be called on immediately prior to the delivery.39 Local providers are as such viewed as being less problematic and time-consuming, and the management of pregnancy and the delivery are consistent with what mothers and mothers-in-law did in the past.39

Mistrust of the biomedical model

There is great fear with respect to biomedical health services, and what are perceived to be unnecessary recommendations for surgery by HCPs.33 41 Local unlicensed providers are preferred because they only prescribe medicines and are not known to offer surgical interventions. There is also mistrust of the HCPs with respect to time management and the prescribing of medicines and tests.34 The belief is that the HCPs are trained through the biomedical model to prescribe multiple tests and medicines regardless of disease type or severity. Due to this fear and mistrust, many women prefer to access state provided primary care services only as a last resort.

Perceptions about provider inefficiency

Women’s uptake of healthcare is significantly influenced by perceptions about provider inefficiencies and shortfalls. Many women complain that the communication level of providers is inadequate as they do not understand guidance or instructions, and as such they are unable to provide follow-up.33 Women clients in particular find it difficult to: (1) share their symptoms and medical history, (2) understand instructions for family planning and (3) follow guidelines for when and where to seek referrals.33 There are also complaints with regard to non-availability of staff at the BHU and poor quality of care when HCPs are present.38 Many women who visit the BHUs have to turn to private facilities due to unavailability of HCP or poor quality of services.39

Low health literacy

The literature suggests that there is very little awareness on the part of women about the necessity of healthcare being provided by trained maternal health staff,27 38 or the importance of family planning33 and basic health issues such as influenzas and viruses.42 One study found that even women who had a child aged 5 years or younger, were not aware of the recommended minimum number of antenatal care visits to be made during pregnancy.39 Due to the lack of health literacy, there is also limited recognition of early symptoms or the need for early healthcare.34 One study identified that awareness and ability to recognise depression and mental health problems was very low in women, leading to its progression and health-seeking only when symptoms are advanced and prognosis is poor.35 Indeed, one study found that most women believed that trained providers and BHUs were only to be approached in the event of an emergency or major health problem.39 As such, early check-ups are not common, and pregnant women typically only visit health facilities if they experience complications or danger signs, such as heavy bleeding or headaches.37 This low awareness and literacy was perceived to be a significant factor in the lack of engagement and active involvement in their own healthcare.43

Cultural factors

Decision-making in families

Many of the women are not able to make their own decisions with regard to the management of their own health and do not have approval from family members to access services.27 34 40 43 Permission and final decision-making for health is mostly controlled by husbands, and mothers-in-law,37 39–42 followed by sisters-in-law and other elders in the home.33 Some of the underpinning reasons for the above include: (a) it is not culturally acceptable for women to travel alone17 or access services outside the home34 41; (b) a cultural belief that women should not control decision-making with regard to health34 35; (c) low literacy and awareness on the part of husbands about women’s health needs and the risks to their health32 and (d) a lack of finances allocated for women’s health within the family.17

Stigma and cultural disapproval

Women’s health needs and health-seeking is associated with stigma and cultural disapproval.43 In most families, women are considered to be inferior and their health needs to be the cause of shame.32 This prevents women from sharing their health needs or seeking healthcare for early signs of disease. Stigma and shame also lead many women to seek healthcare clandestinely or from faith healers located conveniently within the community.35 Cultural disapproval for health-seeking in women, especially for maternal health, which is considered a normal and private process, is part of the socialisation of family members. Younger women who are not married are especially prevented from seeking healthcare or visiting practitioners, as news of any health problems may compromise their ability to receive the best and timely marriage proposals.17 Vaccine hesitancy and refusal to take vaccines are also associated with cultural disapproval and uncertainty about long-term side effects on women’s fertility.42 There is cultural disapproval for the use of condoms as it is associated with promiscuity and sexually transmitted diseases in men.33 Thus, the overall culture is for health to be left in ‘the hands of God’ and ‘the divine master plan’, and for women to remain passive as opposed to active in health-seeking.

Role of religion

The role of religious beliefs and religious clergy in the health-seeking behaviour of women also appears to be significant. One study identified that many religious leaders do not allow family planning or postabortion care services, with some religious leaders claiming that accessing such] services is a ‘sin’.38 41 Almost one-third of women do not use family planning because they believe it is prohibited by their religion.32 Communities with a higher ratio of religious clerics and local Imams (religious leaders) report the lowest uptake of family planning and reproductive health services.33 One study also identified that religious leaders promote the ideology that the use of family planning services and biomedical healthcare is a Western agenda aimed at eroding family values and adversely impacting fertility in Muslim populations.33

Chaperoning issues

When transport is available, many women are nevertheless still prevented from taking up health services due to the unavailability of chaperones, which have to be Mehrams (male members of family with whom marriage would be considered illegal in Islam and with whom veiling is not necessary).37 Mehrams include only the father, husband, brother or son. Many women who are married and living with husbands do not have chaperones, as their husbands are usually working during the day and may not have the time to take their wives for health visits, unless it is an emergency and they are given leave from work. Another study mentioned that the presence of a ’companion’ was important when women left the home and if none was available, then women did not have permission from husband or in-laws, even for health visits.44

Practical issues

Transport, time and finances

There is very little access to public transport for women attempting to access health services that are not within walking distance from their home.27 33 41 Even when roads and infrastructure exist, there is poor availability of public transport, especially in remote and rural locations.37 One study found that women were perceived to have very little time to access health services due to the unequal division of labour within the household.27 Women spend their day fulfilling their responsibilities for the home, children and other dependents living in the house, such as the ageing, sick and disabled. The fact that women are busy performing household chores and fulfilling childcare routines, was perceived by interviewees in another study to be a significant factor in the failure to detect early signs of health problems or to take time out for healthcare.39

Women reported not having money with which to access healthcare.27 Though primary level healthcare services are free of cost, women still need money for prescription drugs, transport, secondary or tertiary care referrals, and lab tests.27 41 Contracted BHUs to the private sector were described in one study as administering fees for services that the centre is not funding, such as for example antenatal services, delivery registration and additional diagnostics, and these user charges are serving as a deterrent for utilisation in women.40 Many women are also unable to access family planning products free of cost, despite the government claim that they are available free.33

Overall, household poverty negatively influences the decision in women and families to access early and preventive health services such as prenatal and postnatal care, and postabortion care.41 This is why many families choose to deliver the child at home with the help of a Dai (a local unlicensed midwife), as the cost is 1/10th than that of natural delivery at a public healthcare institute.34 38 The cost of travelling to a private clinic or healthcare unit for delivery is even more expensive and may require repeat visits of multiple family members, and thus home delivery by a local midwife is preferred over incurring transportation costs.34 39 Affordability is a major issue which prevents women from seeking healthcare until the last possible resort or when there is a health emergency.35 Where poor-class and middle-class families have limited finances available for healthcare, women’s health is not prioritised for financing and this money is saved for male members of the family due to the patriarchal culture.37

Facilitators of the delivery of primary healthcare services

Two facilitators of primary healthcare delivery for women were identified: (1) motivating CHWs with continued training, salary and supervision and (2) selection of CHWs on the basis of certain characteristics.

Motivating CHWs with training, salary and supervision

Peer volunteers are an important resource in the community setting in terms of the delivery of maternal health services because they are known and accepted by local women, but they need to be trained adequately and provided with ongoing professional development.43 Furthermore, peer volunteers were perceived to need to be appropriately incentivised with adequate supervision and satisfactory salaries to keep them motivated to deliver optimal services.43 Most CHWs were working due to household poverty, and so adequate salary and appropriate increments were important for their retention.7

Selection of CHWs on the basis of particular characteristics

A number of studies identified factors that appear to be associated with a higher level of motivation to continue to deliver services. First, CMWs who are from poor families and are primary income-earners for their families are known to remain in the profession and continue to deliver good services that are respected.7 Second, better quality services are delivered by CMWs who have ‘intrinsic individual characteristics’ in terms of (1) knowing how to establish and maintain a private practice, (2) having a strong business sense; (3) professionalism and (4) providing maternity care in a respectful manner.7 Third, CMWs who receive family support and approval to remain in their profession and continue their service delivery, were also perceived to be more motivated and committed providers.7 Motivation to work and provide better services in CHWs was also influenced by receiving support from their family for housework and childcare.43

Facilitators of uptake

Five facilitators of the uptake of primary healthcare services for women were identified, under two core themes: (1) Development of trust and acceptance: (a) hiring of local CHWs who are married and have children; (b) use of culturally sensitive methods; (c) development of community-based savings groups (CBSGs); (d) securing the support of wider family. (2) Use of technology.

Development of trust and acceptance

Hiring of local CHWs who are married and have children

CHWs and peer volunteers from within the community were perceived to be more generously accepted by women clients as there is greater association and trust.39 43 Local CHWs have the advantage of language matching and speak the exact same dialect with a familiar accent, which makes them more appealing to the women clients.43 Due to greater trust and belief that community women will not harm them or give them ill advice, more referrals for consultancy and testing is taken up.35 A majority of women are also willing to accept guidance and recommendations for vaccine coverage and immunisation when recommended by a trusted local CHW.42

CHWs who are married and have children are perceived to be more acceptable to women clients as they are found to be more empathetic and respectful providers.43 Married CHWs who have children are able to build friendships with the women clients and share experiences of motherhood and delivery.43 This helps women clients to build trust with the CHW and to look forward to visits and the maintenance of the relationship for ongoing health management and preventive services.

Use of culturally sensitive methods

The design and use of culturally sensitive methods was perceived in some studies to add to the legitimacy and credibility of health services and to encourage family-level support for women’s uptake of services. For example, in group educational sessions including women, husbands and mothers-in-law, one study found that pictorial illustrations of women in local dress performing safe maternal health practices facilitated acceptance and uptake.43 Another study found that printed material and Television programmes about health awareness in local languages facilitated uptake, as familiarity with language helped women to consider the health directive to be part of the regional culture35

Development of CBSGs

The complex financial issues facing women in the community pertain not just to family poverty, but also debt burden and high dependency ratios within the household. CBSGs have been found to support women not just to pool their money, but also to facilitate the sharing of information and discussion of issues related to reproductive health, including the benefits of skilled delivery and the important role of CMWs.45 It was also found that women members of CBSG were more likely to seek healthcare from TBAs and other skilled providers, and have higher utilisation of maternal and neonatal health services.45 Another study found that women were more likely to be able to access emergency healthcare when they had personal savings or were involved in informal savings groups and good relations with their friends and neighbours.38

Securing the support of wider family

Uptake of health services is strongly influenced by the support of family members, friends and local trusted LHWs.45 When family and community members encourage and support health-seeking, women clients find it easier to receive and follow-up with healthcare appointments.37 39

Use of technology

As a result of the COVID-19 pandemic, some LHWs were provided with smartphones to facilitate women clients being referred to specialist providers. These telehealth services were not only accepted by women in the community, but satisfaction with services and clinical outcomes were also found to be favourable.46 In another study, an international funding agency delivered telehealth services to rural women in a one-off project, linking them with underemployed female doctors in major cities and supporting them with digital X-rays at their homes.17 However, limitations were highlighted: (1) LHWs in rural areas are not provided with smartphones by the employer, (2) most women clients do not have access to independent technological equipment (computer or smartphone) or consistent internet to utilise telehealth services without the help of the LHW46 and (3) there are no government plans for upscale, maintenance and financing of telehealth services in Pakistan.17

Discussion

Summary of review

The development and delivery of an effective primary healthcare system has not to date been a priority in Pakistan, and as such there have been limited attempts to synthesise what is known about the barriers and facilitators to effective service delivery.47 This is the first systematic review of the literature aimed at addressing this gap. Reviews of this nature are essential to better policy planning within the primary healthcare sector, especially in developing regions.48 It is also the case that country-specific systematic reviews are best able to identify regional barriers and facilitators to guide national health policy.49 We have been able to identify important barriers and facilitators to delivery and uptake, and thereby to develop some recommendations for reform from the reviewed studies.

The key barriers in terms of the uptake of primary healthcare services related not only to misperceptions about the healthcare service, and to practical issues related to having the time and means to access the services but also cultural factors in terms of the limited health decision-making rights of women, stigma and cultural disapproval with regard to matters related to women’s health, and religious edicts preventing health-seeking behaviours. Issues related to the development of trust and acceptance, including the use of culturally sensitive methods and attempts to secure support for primary healthcare from the wider family, in addition to a more effective use of technology were identified as key facilitators of the uptake of primary healthcare services for women.

The most significant barriers to the delivery of effective primary healthcare in terms of improving women’s health were not only service related, but also related to wider family/cultural issues. So, while many interviewees identified problems relating to inadequate training; centre unresponsiveness and inefficient monitoring etc, wider problems related to perceptions about safety and work–family conflict in CHWs, mistrust of biomedically based services; perceptions about provider inefficiency; low health literacy, and restrictions by their families preventing CHWs from travelling alone to deliver services and travel after dusk were also identified as important barriers.

The key facilitators of more effective primary healthcare delivery for women were largely staff related in terms of the perceived need to better motivate CHWs through the provision of continuing professional development, better salaries and improved supervision, and also for the selection process to be focused on recruiting CHWs who better represent the women they will be serving in terms of them being local, married and having children of their own.

Although a fairly large number of studies were identified none had assessed barriers and facilitators related to: (1) the service management of BHUs and RHCs; (2) services for a comprehensive primary care model for women—which includes services for mental health, ageing women, young females not of reproductive years (below the age of 18 years), special needs females and women bearing chronic disease burdens; (3) supervision and accountability of primary care services or (4) client satisfaction with existing Sehat Sahulat cash transfers for women’s health. Our findings are limited to assessing barriers and facilitators with respect to maternal health services and the reproductive health of women. Health services for other groups, such as ageing women, unmarried women, disabled and displaced women, may have different barriers and facilitators. Additionally, the included studies did not provide any significant representation from the provinces of Balochistan, and no representation from Gilgit Baltistan or the Pakistan administered Azad Kashmir. Thus, we are unable to comment on any additional barriers and facilitators faced by the women and HCPs in these regions. While this review synthesised information about the barriers and facilitators that were identified in the included studies, we did not attempt to evaluate which factors may be more or less influential in terms of their impact.

The findings of this review suggest that in order to improve the health of women in Pakistan there are significant changes needed not only to the delivery of healthcare services but to the wider cultural context in which such services are delivered. For example, unless social interventions are planned to improve the asymmetrical household assistance and the time poverty experienced by women, neither uptake or delivery within the primary healthcare sector will improve. There is also a need for family-level cultural interventions to improve acceptance and support for practising women CHWs. Along with work–family balance, there is a need to introduce interventions to counter the chaperoning issues, such as options for mobile health units visiting women’s homes, female drivers for transport and women community volunteers to accompany women for health visits. Similarly, there is a need to improve health literacy and awareness on the part of women and their families about the benefits of licensed providers and to reduce fear and misconceptions about the biomedical model, through a collaborative approach by social workers, religious leaders and community notables—with the latter two groups having more influence in the country on women’s health behaviour and family support for women’s health-seeking.

Overall, therefore, our synthesis suggests that critical investment and efforts are needed to improve resources, infrastructure, staffing, work culture and employment benefits for women CHWs in Pakistan. Services that are accessible in terms of distance and cost, need careful planning. It is often argued that high-quality service outreach will increase uptake; however, our synthesis also suggests that improving utilisation in conservative countries such as Pakistan is only possible with investment and interventions to raise awareness and health literacy, and to promote cultural reform. Major gaps exist with respect to services for all non-reproductive health related matters, including preventive health, female adolescent health and mental health.

For a country such as Pakistan that faces multiple challenges in administrative coordination, financing and a regressive culture, it is important that multiple stakeholders from the private and public sector and community are involved in strengthening, building and expanding the primary health sector. Multisector collaboration and social policy interventions are also needed to support the primary health sector, including efforts by the finance sector for health subsidisation, the industrial sector for public transport for women, and the education or informal sector for child daycare centres. Finally, greater supervision and accountability is needed in terms of policies, protocols, budget allocation and service delivery, if the primary sector is to effectively support women’s health in a sustainable manner.

Limitations

This review of barriers and facilitators is limited in terms of the studies that have been conducted so far and that only one author conducted the search, screening and data extraction. There were no studies that assessed barriers and facilitators related to: (1) service management of BHUs and RHCs; (2) services for a comprehensive primary care model for women; (3) supervision and accountability studies of primary services or (4) client satisfaction with existing Sehat Sahulat cash transfers for women’s health. Our findings are limited to assessing barriers and facilitators with respect to maternal health services and the reproductive health of women. Health services for other groups, such as ageing women, unmarried women, disabled and displaced women, may have different barriers and facilitators. Additionally, the included studies did not include any significant representation from the provinces of Balochistan, and no representation from Gilgit Baltistan or the Pakistan administered Azad Kashmir. Thus, we are unable to comment on any additional barriers and facilitators faced by the women and HCPs in these regions. Finally, while this review synthesised information about the barriers and facilitators that were identified in the included studies, we did not attempt to evaluate which factors may be more or less influential in terms of their impact.

Conclusion

Although there are a fairly large number of studies evaluating the barriers and facilitators to the uptake and effectiveness of primary healthcare services for women in Pakistan, these are focused on a limited number of areas within primary care and on women with very specific healthcare needs. The findings suggest that many of the barriers to both uptake of primary healthcare services and their effectiveness are not limited to the healthcare system itself but to the wider social/cultural factors within which primary healthcare services are located. Improvements to the health of women will require changes that address factors not only at the level of the service, but to the subordinate position of women within the family and wider society.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the different experts for their assistance in reading and confirming our findings, including (1) Female Medical Doctors with experience in community health and public health services, including: Dr Ambreen Mansoor, Dr Saira Shahzad and Dr Sumeira Hasan; and (2) Lady Health Workers: Noreena Fiaz, Gule Zartaj and Shamshad Akhtar. We must also thank officers from the Primary and Healthcare Department Dr Asim Hussain, Awais Gohar and Dr Asad Zaheer.

Footnotes

Twitter: @JafreeRizvi

Contributors: SRJ and JB conceptualised the study, designed the methodology and wrote the manuscript. SRJ performed the literature search and interpreted the data. JB supervised the process and contributed to the interpretation. SRJ is the gurantor of the study.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were not involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of this research.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Data availability statement

Data sharing not applicable as no datasets generated and/or analysed for this study. Data sharing not applicable as no datasets generated and/or analysed for this study. All data relevant to the study are included in the article or uploaded as online supplemental information.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

References

- 1.Population . Government of Pakistan, Pakistan economic survey 2022-23. n.d. Available: https://www.finance.gov.pk/survey/chapters_23/12_Population.pdf

- 2.Saddique R, Zeng W, Zhao P, et al. n.d. Understanding multidimensional poverty in Pakistan: implications for regional and demographic-specific policies. Environ Sci Pollut Res;2023:1–16. 10.1007/s11356-023-28026-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chandrasiri J, et al. Impact of out-of-pocket expenditures on families and barriers to use of health services in Pakistan: evidence from the Pakistan social and living standards measurement surveys 2005-2007. Asian Development Bank 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hanedar E, Walker S, Brollo F. n.d. Pakistan: spending needs for reaching sustainable development goals (sdgs). SSRN Journal 10.2139/ssrn.4026282 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hussain I, Habib A, Ariff S, et al. Effectiveness of management of severe acute malnutrition (SAM) through community health workers as compared to a traditional facility-based model: a cluster randomized controlled trial. Eur J Nutr 2021;60:3853–60. 10.1007/s00394-021-02550-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hafeez A, Mohamud BK, Shiekh MR, et al. Lady health workers programme in Pakistan: challenges, achievements and the way forward. J Pak Med Assoc 2011;61:210–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mumtaz Z, Levay AV, Bhatti A. Successful community midwives in Pakistan: an asset-based approach. PLoS One 2015;10:e0135302. 10.1371/journal.pone.0135302 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zain S, Jameel B, Zahid M, et al. The design and delivery of maternal health interventions in Pakistan: a Scoping review. Health Care for Women International 2021;42:518–46. 10.1080/07399332.2019.1707833 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Muhammad Q, Eiman H, Fazal F, et al. Healthcare in Pakistan: navigating challenges and building a brighter future. Cureus 2023;15. 10.7759/cureus.40218 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Huang W, Long H, Li J, et al. Delivery of public health services by community health workers (Chws) in primary health care settings in China: a systematic review (1996–2016). Glob Health Res Policy 2018;3:1–29. 10.1186/s41256-018-0072-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Akter S, Davies K, Rich JL, et al. Indigenous women’s access to maternal Healthcare services in lower-and middle-income countries: a systematic integrative review. Int J Public Health 2019;64:343–53. 10.1007/s00038-018-1177-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tesema A, Joshi R, Abimbola S, et al. Addressing barriers to primary health-care services for Noncommunicable diseases in the African region. Bull World Health Organ 2020;98:906–8. 10.2471/BLT.20.271239 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Paudel M, Leghari A, Ahmad AM, et al. Understanding changes made to reproductive, maternal, newborn and child health services in Pakistan during the COVID-19 pandemic: a qualitative study. Sexual and Reproductive Health Matters 2022;30:2080167. 10.1080/26410397.2022.2080167 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Din NS ud, Jabeen T, Afzal A. Status of women after joining the profession as Lady health workers. Pak J Humanit Soc Sci 2023;11:2473–80. 10.52131/pjhss.2023.1102.0539 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Forman R, Ambreen F, Shah SSA, et al. Sehat Sahulat: A social health justice policy leaving no one behind. Lancet Reg Health Southeast Asia 2022;7:100079. 10.1016/j.lansea.2022.100079 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hasan SS, Mustafa ZU, Kow CS, et al. Sehat Sahulat program”: A leap into the universal health coverage in Pakistan. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2022;19:6998. 10.3390/ijerph19126998 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Habib SS, Jamal WZ, Zaidi SMA, et al. Barriers to access of Healthcare services for rural women—applying gender lens on TB in a rural District of Sindh, Pakistan. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2021;18:10102. 10.3390/ijerph181910102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Panezai S, Ahmad MM, Saqib SE. Factors affecting access to primary health care services in Pakistan: a gender-based analysis. Development in Practice 2017;27:813–27. 10.1080/09614524.2017.1344188 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nizam H, Masoom Ali DrS. Perceived barriers and Facilitators to access mental health services among Pakistani adolescents. Biosight 2021;2:4–12. 10.46568/bios.v2i2.46 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Abdel-Aziz SB, Amin TT, Al-Gadeeb MB, et al. Perceived barriers to breast cancer screening among Saudi women at primary care setting. J Prev Med Hyg 2018;59:E20–9. 10.15167/2421-4248/jpmh2018.59.1.689 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Grant M, Wilford A, Haskins L, et al. Trust of community health workers influences the acceptance of community-based maternal and child health services. Afr J Prim Health Care Fam Med 2017;9:e1–8. 10.4102/phcfm.v9i1.1281 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Al Daajani MM. Barriers to and Facilitators of Antenatal care service use at primary health care centers in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia: A cross-sectional study. Health Sciences 2020;9:17–24. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Holland-Hart DM, Addis SM, Edwards A, et al. Coproduction and health: public and Clinicians’ perceptions of the barriers and Facilitators. Health Expect 2019;22:93–101. 10.1111/hex.12834 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jafree SR, Mahmood QK, Momina AU, et al. Protocol for a systematic review of barriers, Facilitators and outcomes in primary Healthcare services for women in Pakistan. BMJ Open 2021;11:e043715. 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-043715 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cooke A, Smith D, Booth A. Beyond PICO: the SPIDER tool for qualitative evidence synthesis. Qual Health Res 2012;22:1435–43. 10.1177/1049732312452938 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hong QN, Fàbregues S, Bartlett G, et al. The mixed methods appraisal tool (MMAT) version 2018 for information professionals and researchers. EFI 2018;34:285–91. 10.3233/EFI-180221 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ariff S, Mir F, Tabassum F, et al. Determinants of health care seeking behaviors in Puerperal sepsis in rural Sindh, Pakistan: A qualitative study. OJPM 2020;10:255–66. 10.4236/ojpm.2020.109018 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Islam A, Malik FA, Basaria S. Strengthening primary health care and family planning services in Pakistan: some critical issues. J Pak Med Assoc 2002;52:2–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rehman SU, Ahmed J, Bahadur S, et al. Exploring operational barriers encountered by community midwives when delivering services in two provinces of Pakistan: A qualitative study. Midwifery 2015;31:177–83. 10.1016/j.midw.2014.08.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ahmed J, Ur Rehman S, Shahab M. Community midwives' acceptability in their communities: A qualitative study from two provinces of Pakistan. Midwifery 2017;47:53–9. 10.1016/j.midw.2017.02.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mumtaz Z, Salway S, Waseem M, et al. Gender-based barriers to primary health care provision in Pakistan: the experience of female providers. Health Policy Plan 2003;18:261–9. 10.1093/heapol/czg032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ayub A, Kibria Z, Khan F. Evaluation of barriers in non-practising family planning women. J Dow Univ Health Sci 2014;8:31–4. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Khan AW, Amjad CM, Hafeez A, et al. Perceived individual and community barriers in the provision of family planning services by Lady health workers in Tehsil Gujar Khan. J Pak Med Assoc 2012;62:1318–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Asim M, Saleem S, Ahmed ZH, et al. We won’t go there: barriers to Accessing maternal and newborn care in district Thatta, Pakistan. Healthcare 2021;9:1314. 10.3390/healthcare9101314 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Batool F, Boehmer U, Feeley F, et al. Nobody told me about it! A qualitative study of barriers and Facilitators in access to mental health services in women with depression in Karachi, Pakistan. Journal of Psychosomatic Research 2015;78:591. 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2015.03.022 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Haider S, Ali RF, Ahmed M, et al. Barriers to implementation of emergency obstetric and neonatal care in rural Pakistan. PLoS One 2019;14:e0224161. 10.1371/journal.pone.0224161 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.CLIP Working Group, Qureshi RN, Sheikh S, et al. Health care seeking Behaviours in pregnancy in rural Sindh, Pakistan: a qualitative study. Reprod Health 2016;13:75–81. 10.1186/s12978-016-0140-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Memon Z, Zaidi S, Riaz A. Residual barriers for utilization of maternal and child health services: community perceptions from rural Pakistan. GJHS 2016;8:47. 10.5539/gjhs.v8n7p47 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nisar YB, Aurangzeb B, Dibley MJ, et al. Qualitative exploration of facilitating factors and barriers to use of Antenatal care services by pregnant women in urban and rural settings in Pakistan. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2016;16:42. 10.1186/s12884-016-0829-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Riaz A, Zaidi S, Khowaja AR. Perceived barriers to utilizing maternal and neonatal health services in contracted-out versus government-managed health facilities in the rural districts of Pakistan [International journal of health policy management]. Int J Health Policy Manag 2015;4:279–84. 10.15171/ijhpm.2015.50 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Azmat SK, Shaikh BT, Mustafa G, et al. Delivering post-abortion care through a community-based reproductive health volunteer programme in Pakistan. J Biosoc Sci 2012;44:719–31. 10.1017/S0021932012000296 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Khan AA, Varan AK, Esteves-Jaramillo A, et al. Influenza vaccine acceptance among pregnant women in urban slum areas, karachi, pakistan. Vaccine 2015;33:5103–9. 10.1016/j.vaccine.2015.08.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Atif N, Lovell K, Husain N, et al. Barefoot therapists: barriers and Facilitators to delivering maternal mental health care through peer volunteers in Pakistan: a qualitative study. Int J Ment Health Syst 2016;10:24.:24. 10.1186/s13033-016-0055-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ariff S, Mir F, Tabassum F, et al. Determinants of health care seeking behaviors in Puerperal sepsis in rural Sindh, Pakistan: a qualitative study. OJPM 2020;10:255–66. 10.4236/ojpm.2020.109018 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Shaikh BT, Noorani Q, Abbas S. Community based saving groups: an innovative approach to overcome the financial and social barriers in health care seeking by the women in the rural remote communities of pakistan. Arch Public Health 2017;75:1–7. 10.1186/s13690-017-0227-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Shaikh I, Küng SA, Aziz H, et al. Telehealth for addressing sexual and reproductive health and rights needs during the COVID-19 pandemic and beyond: A hybrid Telemedicine-community accompaniment model for abortion and contraception services in Pakistan. Front Glob Womens Health 2021;2:705262. 10.3389/fgwh.2021.705262 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wazir MS, Shaikh BT, Ahmed A. National program for family planning and primary health care Pakistan: a SWOT analysis. Reprod Health 2013;10:60. 10.1186/1742-4755-10-60 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kringos DS, Boerma WGW, Hutchinson A, et al. The breadth of primary care: a systematic literature review of its core dimensions. BMC Health Serv Res 2010;10:65. 10.1186/1472-6963-10-65 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Shi L, Starfield B, Xu J, et al. Primary care quality: community health center and health maintenance organization. South Med J 2003;96:787–95. 10.1097/01.SMJ.0000066811.53167.2E [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2023-076883supp001.pdf (36.9KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2023-076883supp002.pdf (66.4KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2023-076883supp003.pdf (98.8KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2023-076883supp004.pdf (66.7KB, pdf)

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing not applicable as no datasets generated and/or analysed for this study. Data sharing not applicable as no datasets generated and/or analysed for this study. All data relevant to the study are included in the article or uploaded as online supplemental information.