Abstract

Unlike the known aggregation-caused quenching (ACQ) that the enhancement of π–π interactions in rigid organic molecules usually decreases the luminescent emission, here we show that an intermolecular “head-to-head” π–π interaction in the phenanthrene crystal, forming the so-called “transannular effect”, could result in a higher degree of electron delocalization and thus photoluminescent emission enhancement. Such a transannular effect is molecular configuration and stacking dependent, which is absent in the isomers of phenanthrene but can be realized again in the designed phenanthrene-based cocrystals. The transannular effect becomes more significant upon compression and causes anomalous piezoluminescent enhancement in the crystals. Our findings thus provide new insights into the effects of π–π interactions on luminescence emission and also offer new pathways for designing efficient aggregation-induced emission (AIE) materials to advance their applications.

A long range π-conjugation has been realized by the designed π–π interactions in phenanthrene/phenanthrene-based molecular crystals, forming the “transannular effect”, which can be amplified by high pressure and induce novel piezoluminescence.

Introduction

Solid-state luminescent materials have been attracting intensive research interest because of their wide range of applications, such as optoelectronics,1–4 data storage5,6 and theranostics.7–9 Aggregation-induced emission (AIE) has been considered a dominant mechanism for designing organic solid luminescent materials for many applications.10–19 In general, AIE molecules should be non-rigid with active intramolecular motions, and they usually show no emission in solutions at the molecular level but become brightly emissive in mesoscopic aggregated states.20–22 For the AIE mechanism, it is generally accepted that the restriction of intramolecular motions (RIM) could reduce the energy dissipation channels of the non-radiative transition, enhance the radiative transition process and thus increase the emission in the aggregation state.14,18

Compared to non-rigid organic luminescent molecules, rigid organic molecules could exhibit additional advantages such as higher thermal stability and structural stability,23,24 but rigid organic molecules usually show aggregation-caused quenching (ACQ)13,14 in the aggregated state while becoming highly emissive in the isolated form.25 In this case, the π–π stacking enhancement that should affect the π electron behaviors during excitation and radiation processes is considered as the main reason responsible for the ACQ.26,27 Therefore, how to develop a new strategy to realize solid-state luminescent materials with high efficiency for new functionalities (such as piezoluminescence) and extended practical applications by using rigid organic molecules is highly desirable but remains challenging.

Numerous studies show that the delocalization and flowability of π electrons in organic luminescent molecules play important roles in their optical properties.28–30 Graphene can be considered as an extremely large two-dimensional “conjugated molecule” constructed by substantial aromatic carbon rings,31,32 in which π electrons exhibit high delocalization and also high flowability, leading to excellent electrical properties33–35 but the absence of fluorescent properties. In contrast, when the number of aromatic rings decreases to the molecular level (such as polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, PAHs), π electrons tend to display heightened localization and reduced flowability because of the break of long range π-conjugation, which causes new properties and brings fluorescence emission.36–38 Therefore, a possible way to design solid luminescent materials using rigid organic molecules is to promote the delocalization of π electrons without increasing their flowability, which remains a challenging task but is a new strategy different from those by decreasing π–π stacking. However, this has not been explored for the design of efficient luminescent materials.

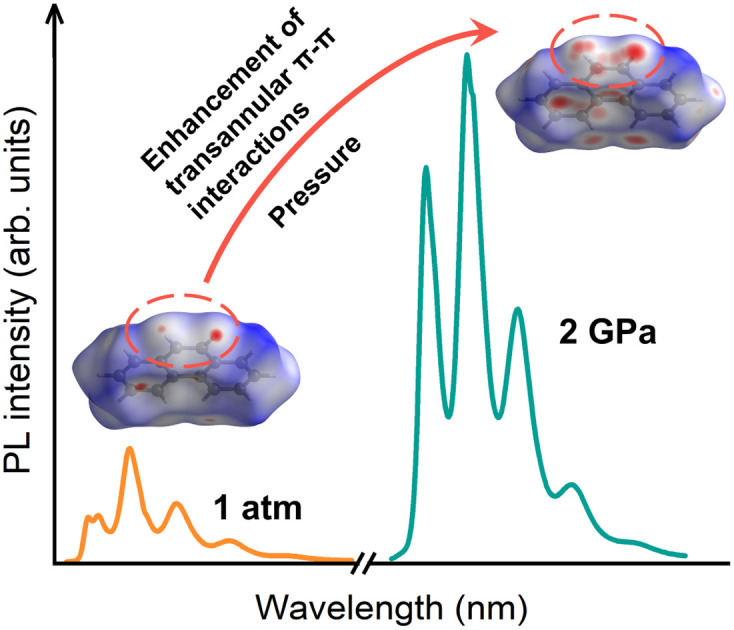

High-pressure can be used to precisely tune intermolecular interactions, altering molecular vibration and rotation modes and electronic excited states, and thus manipulating the emission behaviors.39–44 It is also an efficient technique to tune the delocalization of π electrons and amplify the related effects that are weak at ambient pressure. In this study, we discovered that the “transannular effect”,45–47 a type of weak π–π interaction, occurs in phenanthrene molecular crystals because of their unique molecular configuration. Such an effect becomes more significant upon compression and causes anomalous piezoluminescent enhancement in molecular crystals, which was also observed in phenanthrene-based cocrystals but absent in their isomers. The transannular effect could facilitate delocalization by generating long range π-conjugation in phenanthrene crystals while the flowability of π electrons is still limited within a single molecule, leading to an increase in radiative transition rates and emission intensity. Our finding not only adds another mechanism for aggregation-induced emission enhancement in luminescent materials but also presents an efficient strategy for the design of novel piezoluminescent materials.

Results and discussion

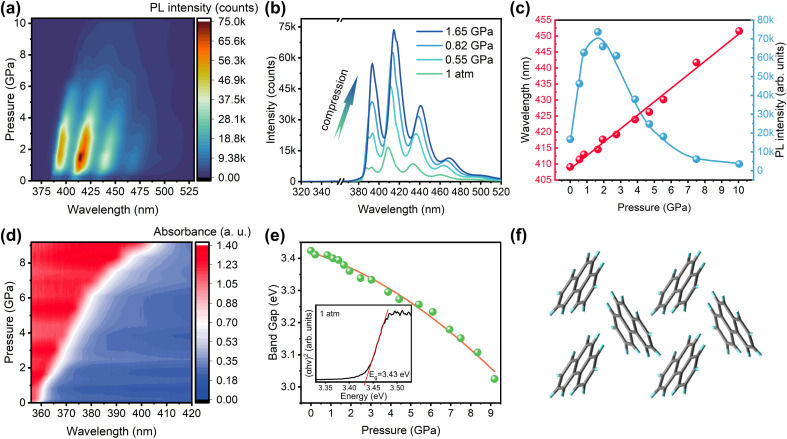

Experimental and theoretical details are presented in the ESI,† and structural information for all crystals and cocrystals involved in this work is presented in Fig. S1.†Fig. 1(a) displays the high-pressure photoluminescence (PL) spectra of phenanthrene crystals obtained by 360 nm excitation. The phenanthrene crystal shows split emission bands, similar to those of single molecules, which agrees well with the weak π–π stacking due to the bent geometry and a “herringbone” pattern48 molecular arrangement in the phenanthrene crystal at ambient pressure (Fig. 1(f)). As shown in Fig. 1(b), phenanthrene shows anomalous emission enhancement at 1 atm–1.65 GPa as pressure increases, while at above 1.65 GPa, the emission exhibits the ACQ phenomenon (Fig. S2†). The quenched emission is primarily attributed to the compression-induced strengthening of intermolecular interactions, which results in more electron internal conversion and less radiation. In situ ultraviolet-visible (UV-vis) absorption spectra demonstrate that the energy gap was narrowed upon compression (Fig. 1(d and e)), leading to the red shift of emission.

Fig. 1. (a) 2D colormap of pressure-dependent PL intensity and wavelength of the phenanthrene crystal. (b) In situ PL spectra of the phenanthrene crystal below 1.65 GPa. (c) Pressure-dependent PL wavelength and intensities. (d) 2D colormap of high-pressure UV-vis absorption spectra of the phenanthrene crystal. (e) Schematic illustrations of the band gap changes. (f) The sketch map for molecular packing of the phenanthrene crystal.

The pressure-dependent PL intensities of phenanthrene crystals upon compression are shown in Fig. 1(c), revealing a significant intensity enhancement of about 5-fold up to 1.65 GPa. To elucidate the underlying reasons for such an anomalous emission enhancement, in situ infrared (IR) and Raman spectra measurements were performed to investigate the intra- and intermolecular interactions in the phenanthrene crystal under high pressure. The experimental results match the calculated results well (Fig. S3(c) and (d)†), and as shown in Fig. 2(a) and S4,† all IR absorption peaks are blue-shifted upon compression, indicating an increase in the intramolecular vibrational energies of phenanthrene and an increase of non-radiative processes.

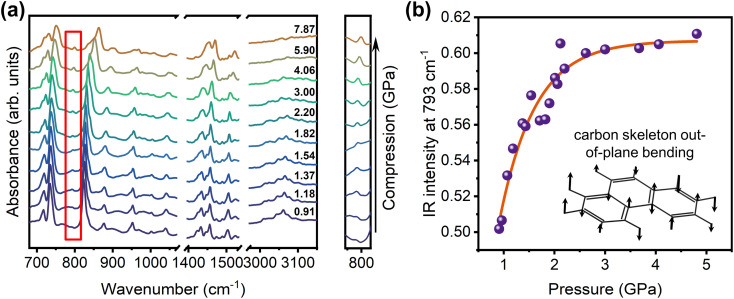

Fig. 2. (a) In situ IR spectra of the phenanthrene crystal upon compression. (b) The pressure-dependent IR absorption intensities around 793 cm−1 and the schematic diagram of the corresponding vibrational mode. The relevant vibrations are marked in the diagrams (a).

We noticed that the IR absorption intensity at approximately 793 cm−1, which represents the carbon skeleton out-of-plane bending vibration of the phenanthrene molecule according to our calculation, increases with pressure. The corresponding intensities of the 793 cm−1 mode as a function of pressure are plotted and shown in Fig. 2(b). This vibration mode exhibits a high degree of symmetry, and its intensity enhancement upon compression indicates that the molecule's dipole moment changes. This change may be due to the increased electronic delocalization of the intermediate aromatic ring because of the non-linear molecular structure of phenanthrene. Our Raman measurements show that all Raman modes are blue-shifted upon compression, which is consistent with our IR results (Fig. S3†). This clearly suggests that the general RIM mechanism cannot explain why phenanthrene exhibits such anomalous emission upon compression. Note that the Raman peaks around 100 cm−1 (see the marked regions in Fig. S3†) from out-of-plane carbon skeleton deformation vibrations exhibit a rapid blue shift at low pressure, implying significant interactions between the neighboring phenanthrene molecules, which may lead to a change in the π-electronic distribution on phenanthrene molecules. Combining our results from IR and Raman measurements, we suggest there is an active intermolecular nonbonding interaction – transannular effect. Note that previous studies show that the transannular effect can indeed alter the electronic structures of the aromatic system.45,46,49,50 In our case, such a unique interaction that most likely occurs between phenanthrene molecules could lead to greater delocalization of π electrons, which can increase the radiative transition rates and result in an anomalous piezoluminescent enhancement.

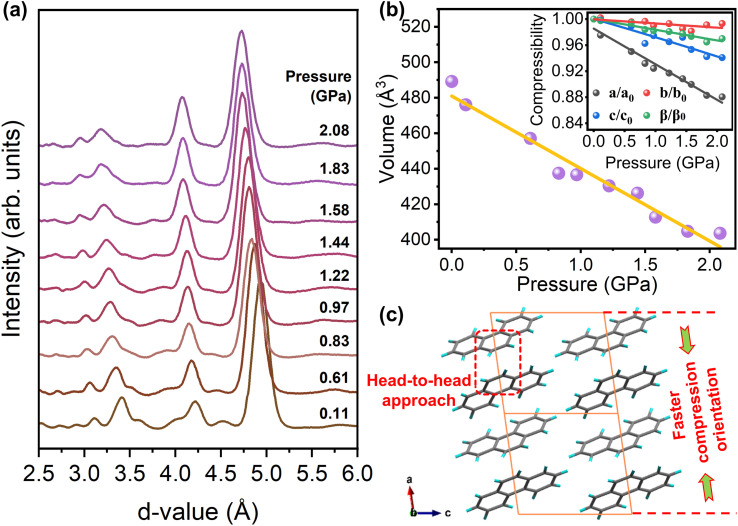

To understand if the molecular stacking could favor the transannular effect in the crystal upon compression, a high-pressure X-ray diffraction (XRD) experiment has been carried out on phenanthrene crystals. The recorded XRD patterns are presented in Fig. 3(a), wherein all the diffraction peaks are shifted to lower d-values, indicating compression of the lattice. Additionally, Fig. 3(b) depicts the variation of unit cell volume with pressure, showing that no structural transition occurred in the phenanthrene crystal during compression. Note that the a-, b-, and c-axes exhibit distinct pressure evolutions upon compression, implying an anisotropic compression of the lattice (inset, Fig. 3(b)). Furthermore, below 2.08 GPa, the a-axis was more compressible than the b- and c-axes, implying that the molecules become more closely packed along the a-axis, which is favorable for head-to-head π–π interactions between molecules (Fig. 3(c)). The Hirshfeld surface (HS) analysis51–53 was performed to quantify and visualize the closed intermolecular atomic contacts in the phenanthrene crystal. The directions and strengths of intermolecular interactions within the molecular crystal are mapped onto the HS using the descriptor dnorm. The dnorm is essentially based on the two contact distances between the nearest atoms present inside (di) and outside (de) the surface, respectively, and is expressed as: dnorm = (di − rvdwi/rvdwi)/(de − rvdwe/rvdwe), where rvdwi and rvdwe are the van der Waals radii of the appropriate atoms internal and external to the surface. The HS analysis also shows that high pressure can significantly enhance intermolecular interactions in head-to-head areas in phenanthrene crystals (Fig. S5†). Our structural analysis indicates that the aforementioned transannular delocalization effect is likely due to the close proximity of the head areas between phenanthrene molecules, which can lead to enhanced transannular effects. As shown in Fig. S5 (c and d),† the interactions between neighboring molecules were significantly enhanced, with an increase of 2.7% in C–H interactions from 1 atm to 2 GPa, respectively. Remarkably, the C–C interactions, which can be considered a π–π stacking interaction, increased by only 0.4% in the same pressure range, indicating that the transannular effects were more dominant than the π–π stacking effects below 2 GPa.

Fig. 3. (a) High-pressure XRD patterns of the phenanthrene crystal below 2.08 GPa. (b) Plotted curves for the unit cell volume of phenanthrene as a function of pressure. Inset shows the compression rate of lattice constants as pressure increases, which is given by the monoclinic P21 structure. (c) The crystal structure viewed along the b-axis, in which the marked regions represent the head-to-head approach between molecules. The XRD patterns are analyzed by JADE.

As we know, Fuzzy bond order (FBO)54,55 was proposed to quantitatively describe the number of electron pairs shared between the fragments and has been used for the characterization of π-conjugation. Here FBO was thus calculated to analyze the conjugation of the head areas between neighboring phenanthrene molecules as shown in Fig. 3(c). The FBO is 0.19995 and 0.25464 for 1 atm and 2 GPa, respectively, indicating the increase of the transannular effect between neighboring phenanthrene molecules as pressure increases. On the other hand, the transannular effects should change the aromaticity of the molecules, and Harmonic oscillator measure of aromaticity (HOMA)56 is the most popular geometry-based index for measuring aromaticity. HOMA was thus calculated and is shown in Table 1. The variation of HOMA was characterized by the three geometric segments of the phenanthrene molecule, which all show an increase in HOMA as pressure increases from 1 atm to 2 GPa. Note that the intermediate phenyl ring at the head (HOMA-2) exhibits the most significant increase from 0.476 to 0.551, indicating that the “head-to-head” interaction remarkably increases the delocalization of π-electrons on this aromatic ring. Such interactions can be considered as medium/long range π-conjugation, which is different from intermolecular π–π stacking. The theoretical calculations show that the proximity of adjacent phenanthrene molecules makes the transannular effect strengthened, which enhances the π-electron conjugation effect.

The values of HOMA for each part of the phenanthrene molecule at 1 atm and 2 GPa.

|

HOMA-1 | HOMA-2 | HOMA-3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 atm | 0.840094 | 0.475597 | 0.844315 |

| 2 GPa | 0.866979 | 0.550963 | 0.876380 |

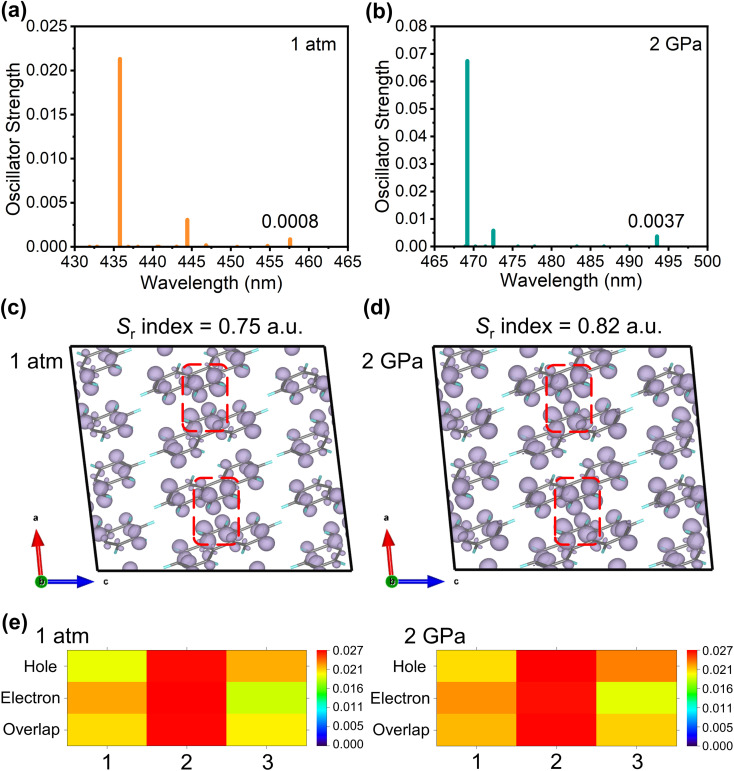

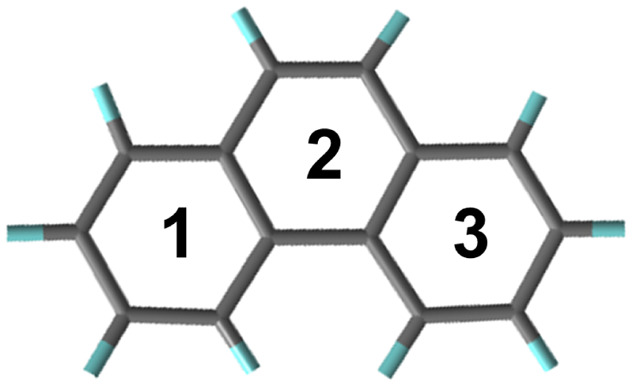

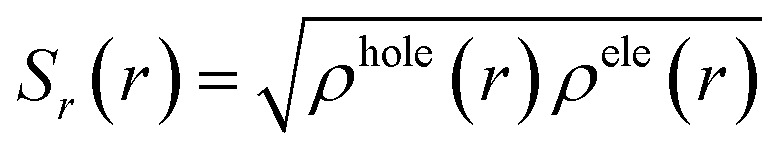

To obtain a further understanding of how the transannular effect caused the emission enhancement upon compression, we calculated the excited state properties of the phenanthrene crystal.57 It is well known that the emission intensity of a system is proportional to the oscillator strength. We observed that the oscillator strength of emission in the phenanthrene crystal increases by an order of magnitude under high pressure as compared to that at ambient pressure (Fig. 4(a and b)), which agrees well with the observed emission enhancement in the experiment. The hole–electron analysis58 was further performed to analyze the excitation characteristic of S1 → S0. As shown in Fig. S6,† the photo-induced S1 → S0 transition presents a locally excited (LE) feature at both ambient pressure and 2 GPa. Furthermore, the overlap function between hole and electron distribution can be defined as  , in which ρhole and ρele represent the densities of holes and electrons.59 As shown in Fig. 4(c) and (d), the Sr is 0.75 and 0.82 for 1 atm and 2 GPa, respectively, indicating the increase of electron–hole overlap as pressure increases, which implies an increase in the orbital overlap between the excited state and ground state. This will increase the radiative transition probability and thus cause an enhancement of emission. In addition, it is found that the smaller the hole/electron delocalization index (HDI/EDI), the larger the spatial delocalization of the hole/electron.59 The HDI and EDI of the phenanthrene crystal were calculated, which decrease from 1.92 to 1.67 and from 1.89 to 1.83, respectively, as pressure increases from 1 atm to 2 GPa, indicating an increase in spatial delocalization of the hole/electron upon compression. This is in agreement with the result obtained from the HOMA analysis. As shown in Fig. 4(e), the heat map of the hole, electron and hole–electron overlap for the three fragments is presented in Table 1, which shows that the intermediate aromatic ring plays a dominant role in the S1 → S0 emission. Our theoretical simulations further demonstrate that head-to-head transannular delocalization alters the electronic structure of the phenanthrene molecule, which affects its emission.

, in which ρhole and ρele represent the densities of holes and electrons.59 As shown in Fig. 4(c) and (d), the Sr is 0.75 and 0.82 for 1 atm and 2 GPa, respectively, indicating the increase of electron–hole overlap as pressure increases, which implies an increase in the orbital overlap between the excited state and ground state. This will increase the radiative transition probability and thus cause an enhancement of emission. In addition, it is found that the smaller the hole/electron delocalization index (HDI/EDI), the larger the spatial delocalization of the hole/electron.59 The HDI and EDI of the phenanthrene crystal were calculated, which decrease from 1.92 to 1.67 and from 1.89 to 1.83, respectively, as pressure increases from 1 atm to 2 GPa, indicating an increase in spatial delocalization of the hole/electron upon compression. This is in agreement with the result obtained from the HOMA analysis. As shown in Fig. 4(e), the heat map of the hole, electron and hole–electron overlap for the three fragments is presented in Table 1, which shows that the intermediate aromatic ring plays a dominant role in the S1 → S0 emission. Our theoretical simulations further demonstrate that head-to-head transannular delocalization alters the electronic structure of the phenanthrene molecule, which affects its emission.

Fig. 4. (a and b) The emission oscillator strengths of phenanthrene calculated at 1 atm and 2 GPa. (c and d) The overlap function Sr(r) during the S1 → S0 transition at 1 atm and 2 GPa (isosurface level = 0.00016 a.u.), the marked regions represent the head-to-head areas between molecules. (e) The contributions of the three parts of the phenanthrene molecule (rings 1, 2, 3) to the hole, electron, and orbital overlap during the S1 → S0 transition at 1 atm and 2 GPa.

The above results indicate that the transannular effect should be due to the bent geometry of phenanthrene. For comparison, the linear isomer of phenanthrene, anthracene, was studied and it exhibits a normal ACQ behavior accompanied by red-shifted emission upon compression in both experiments and calculations (Fig. S7(b–d)†), despite anthracene and phenanthrene having very similar molecular packing in the corresponding crystals (Fig. S7(a)†). The molecular configuration-dependent emission responses can be understood by the fact that the linear anthracene can easily form an excimer60,61 and thus reduce the emission under high pressure, while the bent geometry is more favorable to suppress the increased π–π stacking between parallel phenanthrene molecules upon compression and provides a stronger steric effect. These differences in molecular configuration may be the reason why transannular effects do not occur in anthracene crystals.

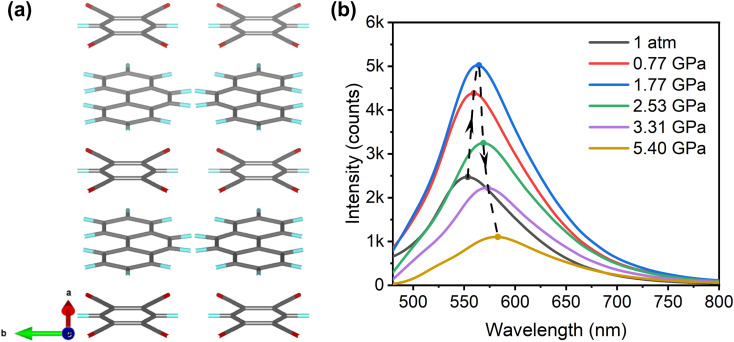

We further demonstrate that the transannular effect could be either preserved or suppressed by introducing another component to form piezoluminescent cocrystals. Considering from molecular packing, we insert 1,2,4,5-tetracyanobenzene (TCNB) into phenanthrene (Phe) crystals, forming Phe–TCNB cocrystals. The TCNB could serve as an acceptor and hold the cocrystal's lowest unoccupied molecular orbital (LUMO), thereby simplifying the energy transfer route (charge-transfer (CT) emission). The TCNB could also prevent the face-to-face packing of phenanthrene molecules and thus leave only their head-to-head interactions (Fig. 5(a)). Our high-pressure PL spectra (Fig. 5(b)) reveal that the Phe–TCNB cocrystal indeed exhibits emission enhancement at a pressure range of 1 atm–1.77 GPa, but no structural phase change occurs in the cocrystals (Fig. S8†). The high-pressure IR absorption spectra of the Phe–TCNB cocrystal (Fig. S9†) also show that all IR absorption peaks were blue-shifted as pressure increased, indicating that the nonradiative energy dissipation of the molecule is not suppressed. Instead, the 796 cm−1 and 1602 cm−1 absorption peaks of Phe–TCNB from the carbon skeleton out-of-plane and in-plane bending display anomalous intensity enhancement as pressure increases, giving a strong indication for the transannular effect in this cocrystal. Note that when phenanthrene was replaced by its linear isomer anthracene (Ant), forming the Ant–TCNB cocrystal, emission quenching was observed upon compression (Fig. S10†). We could also destroy the head-to-head interactions between the phenanthrene molecules by inserting anthracene in Phe–TCNB cocrystals, forming a ternary Ant0.5–Phe0.5–TCNB cocrystal. In this case, the transannular effect was suppressed and emission quenching was observed upon compression (Fig. S11†). These results thus demonstrate that the transannular effect can be applicable to different luminescent materials, offering new pathways for designing more efficient organic luminescent materials for different applications.

Fig. 5. (a) The sketch map for molecular packing of Phe–TCNB. (b) High-pressure PL spectra of Phe–TCNB.

Experimental and computational details

Materials source, synthesis and crystal structure

Phenanthrene (Phe, 98%) was purchased from Alfa Aesar, anthracene (Ant, 99%) was purchased from MACKLIN, and 1,2,4,5-tetracyanobenzene (TCNB, 97%) was purchased from Tokyo Chemical Industry Co., Ltd (TCI). All of the chemicals were used as received without further purification. The Phe–TCNB, Ant–TCNB and Ant0.5–Phe0.5–TCNB cocrystals were prepared by solvent evaporation methods. Identical molar masses of phenanthrene and TCNB were dissolved in excess tetrahydrofuran (THF) solutions and ultrasonicated for 12 minutes. The yellow stick-like transparent sample Phe–TCNB was obtained after evaporation of solvent from the solution after 3–4 days under ambient conditions. Ant–TCNB and Ant0.5–Phe0.5–TCNB cocrystals can be obtained by the same method. The initial crystal structures of our phenanthrene and anthracene were obtained from the Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre (CCDC, no. 1232373 and no. 950158).

In situ high-pressure experiments

High-pressure experiments were performed in a diamond anvil cell (DAC). Samples were loaded into a 120 μm diameter hole drilled in the T301 stainless-steel gasket. Pressure was calibrated by the fluorescence emission of ruby in the sample chamber.62 The pressure transmitting medium (PTM) used in the high-pressure PL, XRD, Raman and UV-vis absorption measurements was silicone oil, while it was KBr in the high-pressure IR measurements. A home-built integrated optical measurement system was used to collect high-pressure PL spectra and ultraviolet-visible (UV-vis) absorption spectra of phenanthrene and anthracene, and a semiconductor UV laser and a deuterium-halogen lamp were used as the excitation sources for the PL and absorption spectra, respectively, along with a Horiba Jobin Yvon iHR320 spectrometer; the PL excitation laser had a wavelength of 360 nm. And PL measurements of Phe–TCNB, Ant–TCNB and Ant0.5–Phe0.5–TCNB were performed on a Raman spectrometer equipped with a CCD detector (Renishaw in Via) in fluorescence mode, and a 514 nm line of a Cobolt FandangoTM laser was used for the excitation source. Infrared measurements were carried out using a Bruker Vertex 80 V spectrometer with a liquid nitrogen-cooled MCT detector. In situ high-pressure X-ray diffraction measurements were performed using a Rigaku Synergy Custom FR-X (λ = 0.7093 Å), while ambient-pressure X-ray diffraction measurements were performed using a Rigaku MicroMax-007 HF (λ = 1.5418 Å). High-pressure Raman spectra were collected using a LabRAM HR Evolution spectrometer (HORIBA Jobin-Yvon) excited by a 473 nm laser.

Computational details

The vibrational analysis was performed using the CASTEP63 module in the Materials Studio package. The exchange and correlation of electrons were treated by the generalized gradient approximation (GGA) with the Perdew–Burke–Ernzerhof (PBE) functional, and the OTFG norm-conserving pseudo-potentials were used for calculations. We used the CP2K software package57 to perform geometry optimization and electronic structure simulation of a 2 × 2 × 2 supercell with 384 atoms. Our calculations employed the TZVP basis set, Goedecker–Teter–Hutter (GTH) pseudo-potential, PBE functional and dispersion corrected density functional (DFT-D3(BJ)), with a grid cutoff of 400 Ry. The relaxation of atomic positions and calculation of the electronic structure properties of excited states are performed by using linear response TDDFT for the singlet excited state. The CP2K input files, Fuzzy bond order (FBO) analysis,54 hole–electron analysis58 and HOMA analysis56 were generated using the Multiwfn program.55 The Crystal-Explorer software 21.5 was employed to create Hirshfeld surface plots.51–53 The lattice parameters at 1 atm and 2 GPa were calculated using the CP2K code by optimizing the energy of the geometry.

Conclusion

Our experiments and calculations strongly suggest that a unique transannular effect occurs in the phenanthrene crystal, which is related to its bent molecular geometry but absent in its isomers. The unique molecular geometry causes a typical head-to-head π–π interaction between phenanthrene molecules which can be modified by pressure, resulting in a higher degree of electron delocalization and thus an anomalous emission enhancement upon compression. Moreover, from the molecular stacking point of view, we succeeded in the design of phenanthrene-based cocrystals with the transannular effect and did observe similar piezoluminescence enhancement below 1.77 GPa. This indicates that the transannular effect can be active in both locally excited (LE) phenanthrene and charge-transfer (CT) phenanthrene-based cocrystals. Our findings contribute to a better understanding of the role of some typical π–π interactions on luminescence emission in highly aggregated conjugated systems and also provide a new way to design new organic AIE materials that could be used in stimulus response, optoelectronic devices, biomedical engineering, and other fields.

Data availability

Essential data are provided in the main text and the ESI.† Data can be available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Author contributions

M. Y. and C. Z. conceived and supervised the study. T. X., C. Z. and D. C. designed and performed the experiments. C. Z., X. Y. and Z. Y. carried out the theoretical study. X. Y. carried out the structure analysis. S. H., K. H., Y. S., J. D., Q. L., P. W., R. L. and B. L. participated in the scientific discussions. T. X., M. Y. and C. Z. wrote and revised the manuscript.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts to declare.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported financially by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (52225203, U2032215, 12304017, and 12104175), and the China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (2022M720054). We thank the Shanghai Synchrotron Radiation Facility and Beijing Synchrotron Radiation Facility. We also thank the Instrument and Equipment Sharing Platform, College of Physics, Jilin University for the XRD measurements.

Electronic supplementary information (ESI) available. See DOI: https://doi.org/10.1039/d3sc04006b

References

- Setaro A. Adeli M. Glaeske M. Przyrembel D. Bisswanger T. Gordeev G. Maschietto F. Faghani A. Paulus B. Weinelt M. Preserving π-conjugation in covalently functionalized carbon nanotubes for optoelectronic applications. Nat. Commun. 2017;8:14281. doi: 10.1038/ncomms14281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han Y. Bai L. Lin J. Ding X. Xie L. Huang W. Diarylfluorene-Based Organic Semiconductor Materials toward Optoelectronic Applications. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2021;31:2105092. doi: 10.1002/adfm.202105092. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Grimsdale A. C. Leok Chan K. Martin R. E. Jokisz P. G. Holmes A. B. Synthesis of light-emitting conjugated polymers for applications in electroluminescent devices. Chem. Rev. 2009;109:897–1091. doi: 10.1021/cr000013v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farinola G. M. Ragni R. Electroluminescent materials for white organic light emitting diodes. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2011;40:3467–3482. doi: 10.1039/C0CS00204F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irie M. Fukaminato T. Sasaki T. Tamai N. Kawai T. A digital fluorescent molecular photoswitch. Nature. 2002;420:759–760. doi: 10.1038/420759a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irie M. Fukaminato T. Matsuda K. Kobatake S. Photochromism of diarylethene molecules and crystals: memories, switches, and actuators. Chem. Rev. 2014;114:12174–12277. doi: 10.1021/cr500249p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li K. Liu B. Polymer-encapsulated organic nanoparticles for fluorescence and photoacoustic imaging. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2014;43:6570–6597. doi: 10.1039/C4CS00014E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng G. Liu B. Aggregation-induced emission (AIE) dots: emerging theranostic nanolights. Acc. Chem. Res. 2018;51:1404–1414. doi: 10.1021/acs.accounts.8b00060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang Y. You X. Wang L. Zhang G. Gui S. Jin Y. Zhao R. Zhang D. Pyridinium-substituted tetraphenylethylenes functionalized with alkyl chains as autophagy modulators for cancer therapy. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2020;132:10128–10137. doi: 10.1002/ange.202001906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang H. Zhao Z. Turley A. T. Wang L. McGonigal P. R. Tu Y. Li Y. Wang Z. Kwok R. T. Lam J. W. Aggregate science: from structures to properties. Adv. Mater. 2020;32:2001457. doi: 10.1002/adma.202001457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Würthner F. Aggregation-induced emission (AIE): a historical perspective. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2020;59:14192–14196. doi: 10.1002/anie.202007525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki S. Sasaki S. Sairi A. S. Iwai R. Tang B. Z. Konishi G. i. Principles of aggregation-induced emission: design of deactivation pathways for advanced AIEgens and applications. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2020;59:9856–9867. doi: 10.1002/anie.202000940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mei J. Leung N. L. Kwok R. T. Lam J. W. Tang B. Z. Aggregation-induced emission: together we shine, united we soar. Chem. Rev. 2015;115:11718–11940. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrev.5b00263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mei J. Hong Y. Lam J. W. Qin A. Tang Y. Tang B. Z. Aggregation-induced emission: the whole is more brilliant than the parts. Adv. Mater. 2014;26:5429–5479. doi: 10.1002/adma.201401356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Q. Li Z. The strong light-emission materials in the aggregated state: what happens from a single molecule to the collective group. Adv. Sci. 2017;4:1600484. doi: 10.1002/advs.201600484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu F. Xu S. Liu B. Photosensitizers with aggregation-induced emission: materials and biomedical applications. Adv. Mater. 2018;30:1801350. doi: 10.1002/adma.201801350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong Y. Lam J. W. Tang B. Z. Aggregation-induced emission. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2011;40:5361–5388. doi: 10.1039/C1CS15113D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong Y. Lam J. W. Tang B. Z. Aggregation-induced emission: phenomenon, mechanism and applications. Chem. Commun. 2009:4332–4353. doi: 10.1039/B904665H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai X. Liu B. Aggregation-induced emission: recent advances in materials and biomedical applications. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2020;59:9868–9886. doi: 10.1002/anie.202000845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo J. Xie Z. Lam J. W. Cheng L. Chen H. Qiu C. Kwok H. S. Zhan X. Liu Y. Zhu D. Aggregation-induced emission of 1-methyl-1,2,3,4,5-pentaphenylsilole. Chem. Commun. 2001:1740–1741. doi: 10.1039/B105159H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang B. Z. Photoluminescence and electroluminescence of hexaphenylsilole are enhanced by pressurization in the solid state. Chem. Commun. 2008:2989–2991. doi: 10.1039/b803539c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng H. T. Yuan Y. X. Xiong J. B. Zheng Y. S. Tang B. Z. Macrocycles and cages based on tetraphenylethylene with aggregation-induced emission effect. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2018;47:7452–7476. doi: 10.1039/C8CS00444G. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stein S. E. Brown R. π-Electron properties of large condensed polyaromatic hydrocarbons. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1987;109:3721–3729. doi: 10.1021/ja00246a033. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dunitz J. D. Gavezzotti A. Attractions and repulsions in molecular crystals: what can be learned from the crystal structures of condensed ring aromatic hydrocarbons? Acc. Chem. Res. 1999;32:677–684. doi: 10.1021/ar980007+. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Birks J. B., Photophysics of Aromatic Molecules, 1970 [Google Scholar]

- Huang Y. Xing J. Gong Q. Chen L. C. Liu G. Yao C. Wang Z. Zhang H. L. Chen Z. Zhang Q. Reducing aggregation caused quenching effect through co-assembly of PAH chromophores and molecular barriers. Nat. Commun. 2019;10:169. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-08092-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park M. Jeong Y. Kim H. S. Lee W. Nam S. H. Lee S. Yoon H. Kim J. Yoo S. Jeon S. Quenching-Resistant Solid-State Photoluminescence of Graphene Quantum Dots: Reduction of π–π Stacking by Surface Functionalization with POSS, PEG, and HDA. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2021;31:2102741. doi: 10.1002/adfm.202102741. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu W. Zheng R. Zhen Y. Yu Z. Dong H. Fu H. Shi Q. Hu W. Rational design of charge-transfer interactions in halogen-bonded co-crystals toward versatile solid-state optoelectronics. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2015;137:11038–11046. doi: 10.1021/jacs.5b05586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei Y. C. Kuo K. H. Chi Y. Chou P. T. Efficient Near-Infrared Luminescence of Self-Assembled Platinum (II) Complexes: From Fundamentals to Applications. Acc. Chem. Res. 2023;56:689–699. doi: 10.1021/acs.accounts.2c00827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y. Jiang S. Glusac K. Powell D. H. Anderson D. F. Schanze K. S. Photophysics of monodisperse platinum-acetylide oligomers: delocalization in the singlet and triplet excited states. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2002;124:12412–12413. doi: 10.1021/ja027639i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X. Y. Yao X. Müllen K. Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in the graphene era. Sci. China: Chem. 2019;62:1099–1144. doi: 10.1007/s11426-019-9491-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gutzler R. Perepichka D. F. π-Electron conjugation in two dimensions. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013;135:16585–16594. doi: 10.1021/ja408355p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi Y. W. Choi H. J. Dichotomy of electron-phonon coupling in graphene moire flat bands. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2021;127:167001. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.127.167001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao Y. Fatemi V. Fang S. Watanabe K. Taniguchi T. Kaxiras E. Jarillo-Herrero P. Unconventional superconductivity in magic-angle graphene superlattices. Nature. 2018;556:43–50. doi: 10.1038/nature26160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolotin K. I. Ghahari F. Shulman M. D. Stormer H. L. Kim P. Observation of the fractional quantum Hall effect in graphene. Nature. 2009;462:196–199. doi: 10.1038/nature08582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamaguchi Y. Matsubara Y. Ochi T. Wakamiya T. Yoshida Z. How the π conjugation length affects the fluorescence emission efficiency. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008;130:13867–13869. doi: 10.1021/ja8040493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loh K. P. Bao Q. Eda G. Chhowalla M. Graphene oxide as a chemically tunable platform for optical applications. Nat. Chem. 2010;2:1015–1024. doi: 10.1038/nchem.907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao L. Meziani M. J. Sahu S. Sun Y. P. Photoluminescence properties of graphene versus other carbon nanomaterials. Acc. Chem. Res. 2013;46:171–180. doi: 10.1021/ar300128j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhai C. Yin X. Niu S. Yao M. Hu S. Dong J. Shang Y. Wang Z. Li Q. Sundqvist B. Molecular insertion regulates the donor–acceptor interactions in cocrystals for the design of piezochromic luminescent materials. Nat. Commun. 2021;12:4084. doi: 10.1038/s41467-021-24381-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yin X. Zhai C. Hu S. Yue L. Xu T. Yao Z. Li Q. Liu R. Yao M. Sundqvist B. Doping of charge-transfer molecules in cocrystals for the design of materials with novel piezo-activated luminescence. Chem. Sci. 2023;14:1479–1484. doi: 10.1039/D2SC06315H. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu H. Gu Y. Dai Y. Wang K. Zhang S. Chen G. Zou B. Yang B. Pressure-induced blue-shifted and enhanced emission: a cooperative effect between aggregation-induced emission and energy-transfer suppression. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2020;142:1153–1158. doi: 10.1021/jacs.9b11080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong Y. Xu B. Zhang J. Tan X. Wang L. Chen J. Lv H. Wen S. Li B. Ye L. Piezochromic luminescence based on the molecular aggregation of 9, 10-Bis ((E)-2-(pyrid-2-yl) vinyl) anthracene. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2012;51:10782–10785. doi: 10.1002/anie.201204660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang T. Yong X. Yu J. Wang Y. Wu M. Yang Q. Hou X. Liu Z. Wang K. Yang X. Brightening Blue Photoluminescence in Nonemission MOF-2 by Pressure Treatment Engineering. Adv. Mater. 2023;35:2211729. doi: 10.1002/adma.202211729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fang J. Fu Z. Chen X. Liu Y. Chen F. Wang Y. Li H. Yusran Y. Wang K. Valtchev V. Piezochromism in Dynamic Three-Dimensional Covalent Organic Frameworks. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2023:e202304234. doi: 10.1002/anie.202304234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang W. Xu J. Lai Y. H. Alternating Conjugated and Transannular Chromophores: Tunable Property of Fluorene-Paracyclophane Copolymers via Transannular π–π Interaction. Org. Lett. 2003;5:2765–2768. doi: 10.1021/ol034413r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cram D. J. Bauer R. H. Macro Rings. XX. Transannular Effects in π–π-Complexes1. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1959;81:5971–5977. doi: 10.1021/ja01531a031. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Stoll M. E. Lovelace S. R. Geiger W. E. Schimanke H. Hyla-Kryspin I. Gleiter R. Transannular Effects in Dicobalta–Superphane Complexes on the Mixed-Valence Class II/Class III Interface: Distinguishing between Spin and Charge Delocalization by Electrochemistry, Spectroscopy, and ab Initio Calculations. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1999;121:9343–9351. doi: 10.1021/ja9914792. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dhar J. Karothu D. P. Patil S. Herringbone to cofacial solid state packing via H-bonding in diketopyrrolopyrrole (DPP) based molecular crystals: influence on charge transport. Chem. Commun. 2015;51:97–100. doi: 10.1039/C4CC06063F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pang X. Wang H. Zhao X. R. Jin W. J. Co-crystallization turned on the phosphorescence of phenanthrene by C–Br⋯ π halogen bonding, π–hole⋯ π bonding and other assisting interactions. CrystEngComm. 2013;15:2722–2730. doi: 10.1039/C3CE26661C. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gao H. Y. Zhao X. R. Wang H. Pang X. Jin W. J. Phosphorescent cocrystals assembled by 1, 4-diiodotetrafluorobenzene and fluorene and its heterocyclic analogues based on C–I···π halogen bonding. Cryst. Growth Des. 2012;12:4377–4387. doi: 10.1021/cg300515a. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bojarska J. Remko M. Fruziński A. Maniukiewicz W. The experimental and theoretical landscape of a new antiplatelet drug ticagrelor: Insight into supramolecular architecture directed by CH⋯F, π⋯π and CH⋯π interactions. J. Mol. Struct. 2018;1154:290–300. doi: 10.1016/j.molstruc.2017.10.053. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Spackman M. A. McKinnon J. J. Fingerprinting intermolecular interactions in molecular crystals. CrystEngComm. 2002;4:378–392. doi: 10.1039/B203191B. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Spackman M. A. Jayatilaka D. Hirshfeld surface analysis. CrystEngComm. 2009;11:19–32. doi: 10.1039/B818330A. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mayer I. Salvador P. Overlap populations, bond orders and valences for ‘fuzzy’atoms. Chem. Phys. Lett. 2004;383:368–375. doi: 10.1016/j.cplett.2003.11.048. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lu T. Chen F. Multiwfn: A multifunctional wavefunction analyzer. J. Comput. Chem. 2012;33:580–592. doi: 10.1002/jcc.22885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krygowski T. M. Crystallographic studies of inter-and intramolecular interactions reflected in aromatic character of. pi.-electron systems. J. Chem. Inf. Comput. Sci. 1993;33:70–78. doi: 10.1021/ci00011a011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kühne T. D. Iannuzzi M. Del Ben M. Rybkin V. V. Seewald P. Stein F. Laino T. Khaliullin R. Z. Schütt O. Schiffmann F. CP2K: An electronic structure and molecular dynamics software package-Quickstep: Efficient and accurate electronic structure calculations. J. Chem. Phys. 2020;152:194103. doi: 10.1063/5.0007045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Z. Lu T. Chen Q. An sp-hybridized all-carboatomic ring, cyclo [18] carbon: Bonding character, electron delocalization, and aromaticity. Carbon. 2020;165:468–475. doi: 10.1016/j.carbon.2020.04.099. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shao Y. Lu T. Li M. Lu W. Theoretical exploration of diverse electron-deficient core and terminal groups in A–DA′ D–A type non-fullerene acceptors for organic solar cells. New J. Chem. 2022;46:3370–3382. doi: 10.1039/D1NJ04571G. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jones P. F. Nicol M. Excimer fluorescence of crystalline anthracene and naphthalene produced by high pressure. J. Chem. Phys. 1965;43:3759–3760. doi: 10.1063/1.1696547. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Birks J. Rep. Prog. Phys. 1975;38:903. doi: 10.1088/0034-4885/38/8/001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mao H. Xu J. A. Bell P. Calibration of the ruby pressure gauge to 800 kbar under quasi-hydrostatic conditions. J. Geophys. Res.: Solid Earth. 1986;91:4673–4676. doi: 10.1029/JB091iB05p04673. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Clark S. J. Segall M. D. Pickard C. J. Hasnip P. J. Probert M. I. Refson K. Payne M. C. First principles methods using CASTEP. Z. Kristallogr. – Cryst. Mater. 2005;220:567–570. doi: 10.1524/zkri.220.5.567.65075. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Essential data are provided in the main text and the ESI.† Data can be available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.