Abstract

Background/Aim

The number of older patients with breast cancer has been increasing and a major challenge is to develop optimal treatment strategies for these patients, who often have comorbidities. Obesity is reportedly a poor prognostic factor in breast cancer, however there is limited research on underweight patients. Clarifying the relationship between physique and prognosis may contribute to the establishment of optimal treatment strategies for older patients with breast cancer.

Patients and Methods

This retrospective study examined clinicopathological data from a multicenter collaborative database on 1,076 patients aged 70 years or older who had undergone curative surgery. According to the body mass index (BMI), patient physique was defined as underweight (<18.5 kg/m2), normal (18.5-24.9 kg/m2) or obese (≥25 kg/m2). In this study, we explored the relationship between the physique of patients with breast cancer and outcomes.

Results

Underweight patients had a significantly lower rate of chemotherapy administration (p=0.017) and a higher rate of presence of other cancer (p=0.022). During the observation period (median of 75.2 months), 133 patients (12%) developed recurrent disease and 131 patients (12%) died. Age, BMI, tumor size, progesterone receptor and the presence of other cancer were independent factors relating to overall survival (p<0.001, p=0.027, p=0.002, p=0.008 and p=0.005, respectively). Patients with a low BMI had a significantly shorter overall survival, but there was no association with disease-free survival in this subset of patients.

Conclusion

Overall survival was shorter in underweight older patients with breast cancer. Our data indicate that being underweight should be considered both in treatment decisions and in future studies of outcomes for older patients with breast cancer.

Keywords: Breast neoplasms, prognosis, underweight, body mass index, physique

The number of older people is increasing worldwide. There were 727 million people aged over 65 years in 2020, and it is generally accepted that this number will have doubled by 2050 (1). For instance, in Japan, patients over 75 years of age accounted for 45.4% of all patients with cancer in 2019 (2). The same applies to breast cancer (3,4). A major challenge is to develop optimal treatment strategies for older patients, who often have comorbidities. For example, the efficacy of chemotherapy in the elderly remains controversial (5,6), mainly due to the exclusion of older patients from many prospective clinical trials. We recently established a database of older patients with breast cancer aged 70 years or more and revealed that adjuvant chemotherapy did not improve their survival (7). While it is impossible to draw general conclusions about the efficacy of chemotherapy due to inter-study variability in treatment details and target patients, there is a need for research into what treatment has true benefit in older patients with breast cancer.

In the current study, we focused on the physique of patients. Obesity is a risk factor for breast cancer in post-menopausal women (8,9) and the recurrence rate in obese patients with breast cancer is reportedly higher (10,11). While many studies have investigated the relationship between obesity and the prognosis of breast cancer (10-15), only a few have examined the characteristics of underweight patients with breast cancer (13,16,17). In other diseases, it is reported that underweight patients have poorer outcomes (18-20). However, the prognosis of underweight older patients with breast cancer remains unclear. We posited that a better understanding of the relationship between physique and prognosis might help in the development of future treatment strategies. As such, in this study, we explored the relationship between patient physique and outcomes, along with other clinicopathological factors, using retrospective data from older patients with breast cancer.

Patients and Methods

Patients. We recently established a database of 1,095 Japanese women aged over 70 years with invasive breast cancer who underwent curative surgery between January 2008 and December 2013 at seven institutions (National Cancer Center Hospital, Juntendo University, Gunma University, Kyoto Prefectural University of Medicine, Fukushima Medical University, Japanese Red Cross Saitama Hospital and Saiseikai Shiga Hospital) (7). Patients who were diagnosed with non-invasive breast cancer, who had bilateral breast cancer, or who lacked clinical data were excluded. Clinicopathological data and details of the clinical course were obtained from the patient’s medical records. Of these, information about the physique of 1,076 patients was available, and these were the subjects of this study. The median age of these patients was 75 (range=70-93) years. According to the body mass index (BMI), a patient’s physique was defined as either underweight (BMI <18.5 kg/m2), normal (18.5-24.9 kg/m2) or obese (≥25 kg/m2).

The primary endpoint of the current study was overall survival (OS), defined as the length of time from primary surgery to the death from any cause, and the secondary endpoint was disease-free survival (DFS), defined as the length of time from primary surgery to any recurrence of breast cancer. Pathological examination was carried out based on the fifth edition of the WHO Classification of Tumors of the Breast. Tumor grade was judged based on the modified Bloom–Richardson histological grading system.

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of each hospital (approval number 2019-093). The need for written informed consent was waived due to it being a retrospective study.

We present the findings following the format recommended by the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) guidelines.

Statistical assessment. Statistical analyses were performed using JMP Pro 16.0.0 statistical software (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA). Associations between clinicopathological parameters and patient physique were evaluated using Pearson’s chi-squared test and Fisher’s exact test. For comparisons of mean values among two or more than two groups, two-sided Student’s t-test or analysis of variance were employed, respectively. To evaluate variables for independent prognostic effects, the Cox proportional hazard model was applied with a 95% confidence interval. Kaplan–Meier curves were drawn and the log-rank test was applied for comparisons of survival between two groups. A value of p<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

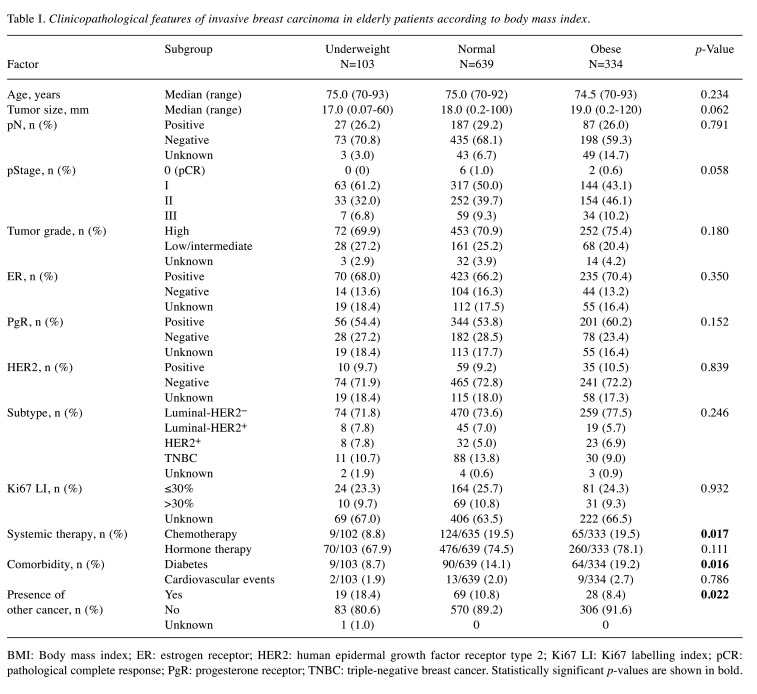

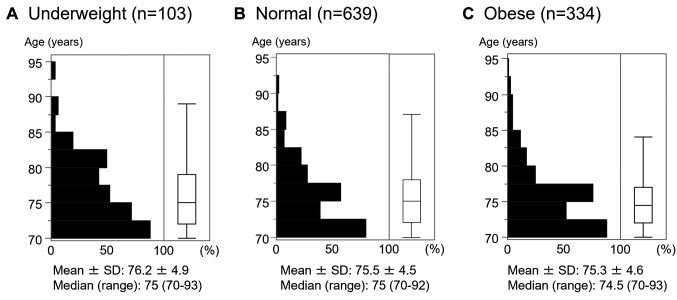

Clinicopathological features of invasive carcinoma in relation to physique. Clinicopathological features of patients in relation to physique are shown in Table I. Samples were stratified by estrogen receptor (ER), progesterone receptor (PgR) (hormone receptor, HR) and human epidermal growth factor receptor type 2 (HER2) status, as luminal-HER2− (HR+/HER2−), luminal-HER2+ (HR+/HER2+), HER2+ (HR−/HER2+), and triple-negative (HR−/HER2−). Of 1,076 patients, 103 (9.6%) were underweight, 639 (59.4%) were normal weight, and 334 (31.0%) were obese. There was no significant difference in age among groups (age distributions are shown in Figure 1). Compared with the normal and obese groups, the underweight group had a significantly lower rate of chemotherapy (p=0.017) and a significantly higher rate of having a presence of other cancer (p=0.022), while diabetes was more frequent in the obese group (p=0.016).

Table I. Clinicopathological features of invasive breast carcinoma in elderly patients according to body mass index.

BMI: Body mass index; ER: estrogen receptor; HER2: human epidermal growth factor receptor type 2; Ki67 LI: Ki67 labelling index; pCR: pathological complete response; PgR: progesterone receptor; TNBC: triple-negative breast cancer. Statistically significant p-values are shown in bold.

Figure 1. Age distribution in relation to physique. distribution of patients’ ages according to physique as indicated by body mass index (BMI) are shown for underweight patients (BMI <18.5 kg/m2) (A), normal-weight patients (BMI=18.5-24.9 kg/m2) (B) and obese patients (BMI ≥30 kg/m2) (C).

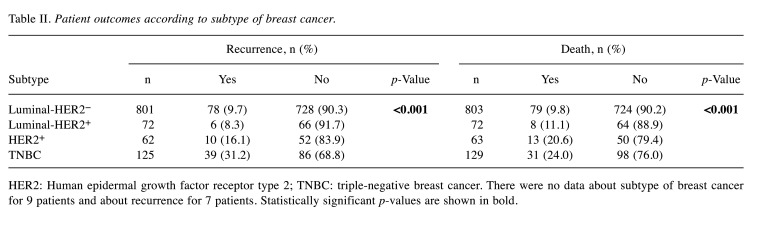

Patient outcomes. We evaluated clinicopathological factors in relation to patient outcome. During the observation period (median=75.2 months, range=0.2-147.9 months), 133 patients had tumor recurrence and 131 patients died, including 47 who died due to breast cancer; of the 1,076 patients, there was no data for seven patients on whether they developed recurrent disease or not. When the patients were divided into two groups, namely the underweight group (BMI<18.5 kg/m2) and the normal/obese group (≥18.5 kg/m2), 11 (10.7%, 11/103) and 122 (12.6%, 122/966) patients had tumor recurrence, respectively, with no statistical difference between these rates (p=0.569). We also compared patient outcomes in relation to tumor subtypes. There were significant differences in recurrence rates among subtypes (Table II; p<0.001), wherein patients with triple-negative tumors had the highest rate of recurrence (31.2%). Differences were also observed in relation to patient death (p<0.001), where patients with HER2+ or triple-negative breast cancer had higher rates of death (20.6% and 24.0%, respectively; Table II).

Table II. Patient outcomes according to subtype of breast cancer.

HER2: Human epidermal growth factor receptor type 2; TNBC: triple-negative breast cancer. There were no data about subtype of breast cancer for 9 patients and about recurrence for 7 patients. Statistically significant p-values are shown in bold.

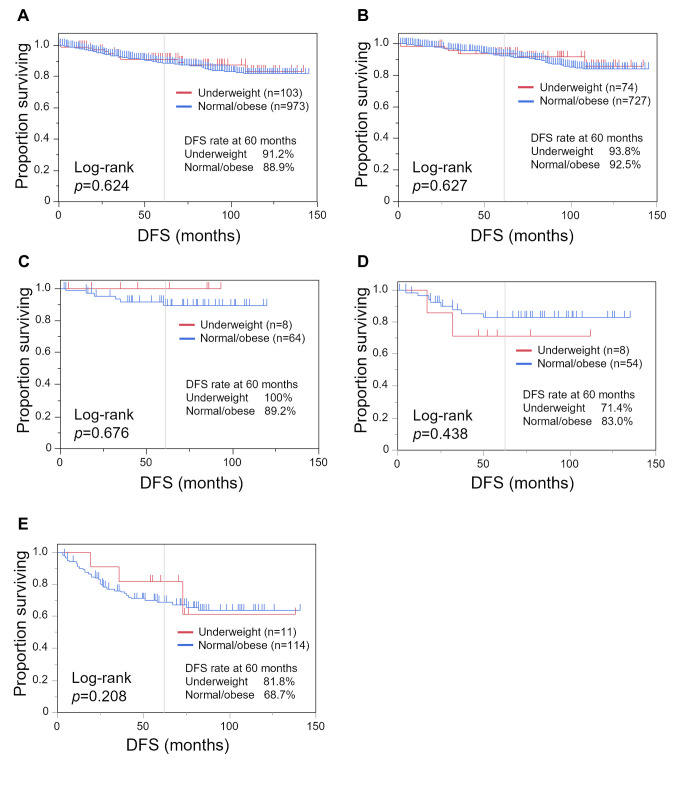

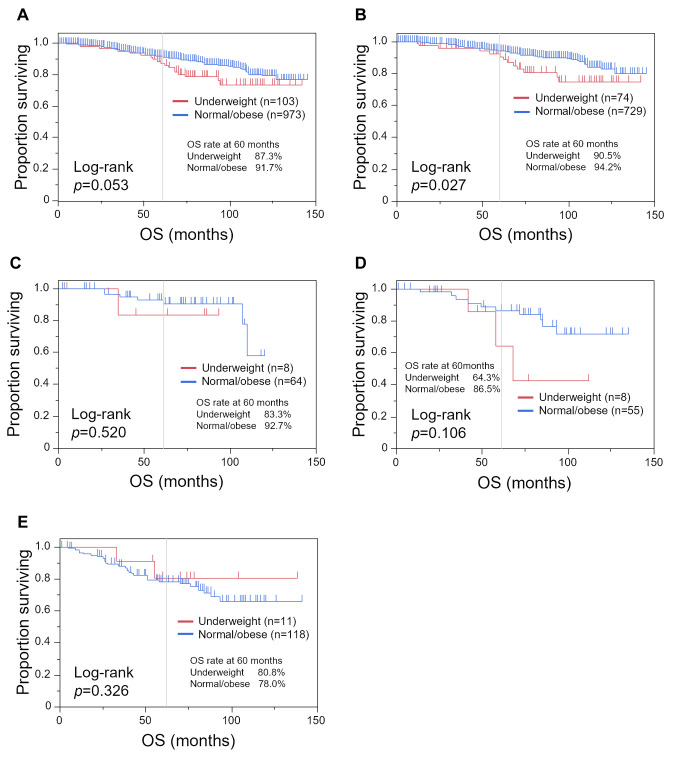

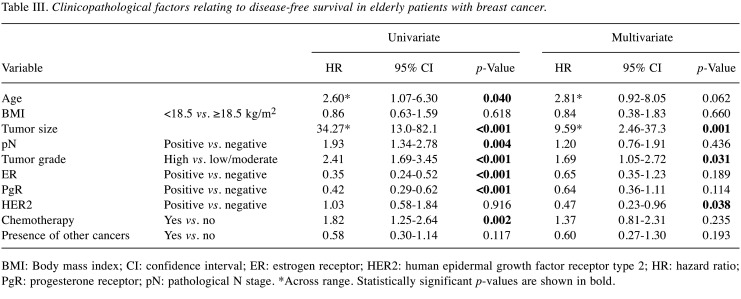

We performed a Kaplan–Meier analysis comparing the underweight and normal/obese groups (Figure 2 and Figure 3). While there was no statistically significant difference in DFS between the underweight and normal/obese groups, with DFS of 91.2% and 88.9% at 60 months, respectively (Figure 2A; p=0.624). OS tended to be shorter in the underweight group, with an OS rate at 60 months of 87.3% compared with 91.7% (Figure 3A; p=0.053). In patients with luminal-HER2− tumors, underweight patients had a shorter OS (Figure 3B; p=0.027).

Figure 2. Kaplan–Meier curves of disease-free survival (DFS) comparing the underweight group (body mass index <18.5 kg/m2) and the normal/obese group (body mass index ≥18.5 kg/m2). Kaplan–Meier curves are shown for all patients (A), and patients with luminal-human epidermal growth factor receptor type 2 (HER2)− (B), luminal-HER2+ (C), HER2+ (D), and triple-negative (E) breast cancer.

Figure 3. Kaplan-Meier curves of overall survival comparing the underweight group (body mass index <18.5 kg/m2) and the normal/obese group (body mass index ≥18.5 kg/m2). Kaplan–Meier curves are shown for all patients (A), and patients with luminal-human epidermal growth factor receptor type 2 (HER2)− (B), luminal-HER2+ (C), HER2+ (D), and triple-negative (E) breast cancer.

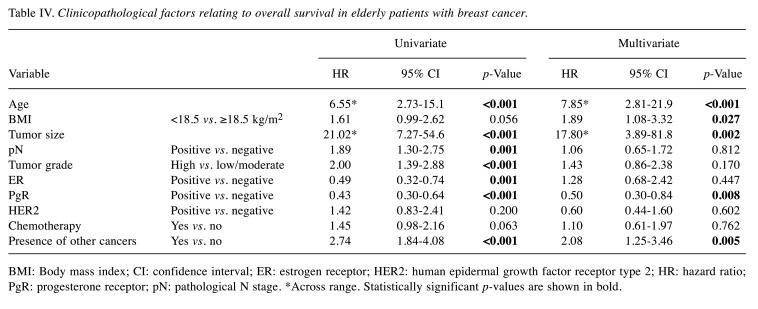

Next, we investigated clinicopathological factors relating to DFS and OS. In the univariate analysis, older age, larger tumor size, positive lymph node metastasis, high tumor grade, ER−, PgR− and receiving chemotherapy were related to poorer DFS (Table III; p=0.040, p<0.001, p=0.004, p<0.001, p<0.001, p<0.001 and p=0.002, respectively). In multivariate analysis, larger tumor size, high tumor grade and HER2 status were independent factors for poor DFS (p=0.001, p=0.031 and p=0.038, respectively); patients with HER2− tumors had a shorter DFS than those with HER2+ tumors. Regarding OS, in the univariate analysis, older age, larger tumor size, positive lymph node metastasis, high tumor grade, ER−, PgR− , and the presence of other cancer were associated with OS (Table IV; p<0.001, p<0.001, p=0.001, p<0.001, p=0.001, p<0.001 and p<0.001, respectively). In multivariate analysis, older age, low BMI, larger tumor size, PgR− and the presence of other cancer were independent factors for poorer OS (p<0.001, p=0.027, p=0.002, p=0.008 and p=0.005, respectively); patients with low BMI had a significantly shorter OS, although no significant difference in DFS was observed.

Table III. Clinicopathological factors relating to disease-free survival in elderly patients with breast cancer.

BMI: Body mass index; CI: confidence interval; ER: estrogen receptor; HER2: human epidermal growth factor receptor type 2; HR: hazard ratio; PgR: progesterone receptor; pN: pathological N stage. *Across range. Statistically significant p-values are shown in bold.

Table IV. Clinicopathological factors relating to overall survival in elderly patients with breast cancer.

BMI: Body mass index; CI: confidence interval; ER: estrogen receptor; HER2: human epidermal growth factor receptor type 2; HR: hazard ratio; PgR: progesterone receptor; pN: pathological N stage. *Across range. Statistically significant p-values are shown in bold.

Discussion

The current study found OS was shorter in underweight older patients with breast cancer who had undergone curative surgery. However, the breast cancer recurrence rate was not high in this population, suggesting that short survival was driven by factors other than breast cancer. Being underweight is reportedly a factor of poor prognosis in patients with cancer (21,22). A higher recurrence rate and worse mortality have also been reported in underweight patients with breast cancer (14,23). The definite cause of this remains unknown. Moon et al. suggested that chronic undernutrition may reduce the effectiveness of systemic treatments (23). However, in our study, this was not the case as recurrent disease was not more common in underweight patients compared to the remaining patients. Poorer prognosis in underweight patients has been observed in other diseases apart from cancer. For example, poorer outcomes have been reported in underweight patients with hypertension and cardiovascular diseases (18-20).

Poor prognosis in underweight patients is likely the result of multiple interacting factors. However, increased ‘vulnerability’ due to sarcopenia and frailty may be a key reason. It is suggested that sarcopenia and frailty should be considered when deciding the treatment plan for older patients with cancer (24-26). Sarcopenia with muscle atrophy leads to a higher risk of falls, fractures, reduced quality of life, and increased risk of infection and mortality (27-30). Frailty is a multidimensional concept that includes physical ability and social and environmental elements, and is known to be associated with an increased risk of death (31,32). Frailty is composed of various components (33), with sarcopenia considered one such component (34). BMI is also sometimes included as an evaluation factor (35-37). Thus, we suspect this underlying vulnerability might be a cause of why, in our study, underweight patients had shorter OS. It should be noted however, that sarcopenia is defined by muscle mass and walking speed, so strictly speaking, being underweight does not automatically indicate sarcopenia. Due to lack of detailed data, we were unable to analyze whether being underweight affected patient outcomes by contributing to the presence of sarcopenia and frailty; further studies designed to specifically evaluate these events are warranted.

Moreover, another possible reason might be the presence of other malignant diseases. In the present study, underweight patients, especially those who had luminal-HER2− tumors, frequently had other cancer that may have contributed to their shorter OS. In addition, we were unable to test this hypothesis due to a lack of information on other cancer, such as the primary organ, time of onset, clinical stage and treatment. Whether patients had lost weight due to other cancer or related treatments is also unknown. The cause of death for some of the patients was also unknown. This lack of some data was a major limitation of this retrospective study.

In conclusion, OS was shorter in underweight elderly patients with breast cancer. As such, being underweight may need to be considered when discussing treatment options and studying patient outcomes in older patients with breast cancer.

Conflicts of Interest

AS reports grants and personal fees from Chugai Pharmaceutical, grants and personal fees from AstraZeneca, grants from Daiichi Sankyo, grants from Eisai, grants from Taiho Pharmaceutical, personal fees from Eli-Lilly, outside the submitted work. Other Authors have nothing to disclose.

Authors’ Contributions

Yumiko Ishizuka, Yoshiya Horimoto, Midori Morita, Emi Tokuda, Toru Higuchi, and Akihiko Shimomura designed this study. Yumiko Ishizuka, Yoshiya Horimoto, Midori Morita, Yukino Kawamura, Katsutoshi Sekine, Sayaka Obayashi, Yuki Kojima, Emi Tokuda, Toru Higuchi, and Akihiko Shimomura collected clinical data. Yumiko Ishizuka and Yoshiya Horimoto conducted data analysis and statistics. Yumiko Ishizuka and Yoshiya Horimoto drafted the original manuscript and Midori Morita, Yukino Kawamura, Yuki Kojima, Emi Tokuda, Toru Higuchi, and Akihiko Shimomura substantively revised it. All Authors revised and approved the final version of the article.

Acknowledgements

The Authors sincerely appreciate Clear Science Pty Ltd for language editing.

References

- 1.World Population Ageing 2020 Highlights. United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division. Available at: https://www.un.org/development/desa/pd/sites/www.un.org.development.desa.pd/files/files/documents/2020/Sep/un_pop_2020_pf_ageing_10_key_messages.pdf. [Last accessed on October 10, 2023]

- 2.Cancer Incidence of Japan. Cancer and Disease Control Division, Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare. Available at: https://www.mhlw.go.jp/content/10900000/000942181.pdf. [Last accessed on October 10, 2023]

- 3.Cancer Statistics in Japan 2022. Institute for Cancer Control, National Cancer Center. Available at: https://ganjoho.jp/public/qa_links/report/statistics/pdf/cancer_statistics_2022.pdf. [Last accessed on October 10, 2023]

- 4.Varghese F, Wong J. Breast cancer in the elderly. Surg Clin North Am. 2018;98(4):819–833. doi: 10.1016/j.suc.2018.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tamirisa N, Lin H, Shen Y, Shaitelman SF, Sri Karuturi M, Giordano SH, Babiera G, Bedrosian I. Association of chemotherapy with survival in elderly patients with multiple comorbidities and estrogen receptor-positive, node-positive breast cancer. JAMA Oncol. 2020;6(10):1548–1554. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2020.2388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sawaki M, Taira N, Uemura Y, Saito T, Baba S, Kobayashi K, Kawashima H, Tsuneizumi M, Sagawa N, Bando H, Takahashi M, Yamaguchi M, Takashima T, Nakayama T, Kashiwaba M, Mizuno T, Yamamoto Y, Iwata H, Kawahara T, Ohashi Y, Mukai H, RESPECT study group Randomized controlled trial of trastuzumab with or without chemotherapy for HER2-positive early breast cancer in older patients. J Clin Oncol. 2020;38(32):3743–3752. doi: 10.1200/JCO.20.00184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Morita M, Shimomura A, Tokuda E, Horimoto Y, Kawamura Y, Ishizuka Y, Sekine K, Obayashi S, Kojima Y, Uemura Y, Higuchi T. Is adjuvant chemotherapy necessary in older patients with breast cancer. Breast Cancer. 2022;29(3):498–506. doi: 10.1007/s12282-021-01329-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Renehan AG, Tyson M, Egger M, Heller RF, Zwahlen M. Body-mass index and incidence of cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective observational studies. Lancet. 2008;371(9612):569–578. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60269-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Suzuki R, Iwasaki M, Inoue M, Sasazuki S, Sawada N, Yamaji T, Shimazu T, Tsugane S, Japan Public Health Center-based Prospective Study Group Body weight at age 20 years, subsequent weight change and breast cancer risk defined by estrogen and progesterone receptor status-the Japan public health center-based prospective study. Int J Cancer. 2011;129(5):1214–1224. doi: 10.1002/ijc.25744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cecchini RS, Swain SM, Costantino JP, Rastogi P, Jeong JH, Anderson SJ, Tang G, Geyer CE Jr, Lembersky BC, Romond EH, Paterson AH, Wolmark N. Body mass index at diagnosis and breast cancer survival prognosis in clinical trial populations from NRG Oncology/NSABP B-30, B-31, B-34, and B-38. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2016;25(1):51–59. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-15-0334-T. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gennari A, Amadori D, Scarpi E, Farolfi A, Paradiso A, Mangia A, Biglia N, Gianni L, Tienghi A, Rocca A, Maltoni R, Antonucci G, Bruzzi P, Nanni O. Impact of body mass index (BMI) on the prognosis of high-risk early breast cancer (EBC) patients treated with adjuvant chemotherapy. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2016;159(1):79–86. doi: 10.1007/s10549-016-3923-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nelson SH, Marinac CR, Patterson RE, Nechuta SJ, Flatt SW, Caan BJ, Kwan ML, Poole EM, Chen WY, Shu XO, Pierce JP. Impact of very low physical activity, BMI, and comorbidities on mortality among breast cancer survivors. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2016;155(3):551–557. doi: 10.1007/s10549-016-3694-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kawai M, Tomotaki A, Miyata H, Iwamoto T, Niikura N, Anan K, Hayashi N, Aogi K, Ishida T, Masuoka H, Iijima K, Masuda S, Tsugawa K, Kinoshita T, Nakamura S, Tokuda Y. Body mass index and survival after diagnosis of invasive breast cancer: a study based on the Japanese National Clinical Database-Breast Cancer Registry. Cancer Med. 2016;5(6):1328–1340. doi: 10.1002/cam4.678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chan DSM, Vieira AR, Aune D, Bandera EV, Greenwood DC, McTiernan A, Navarro Rosenblatt D, Thune I, Vieira R, Norat T. Body mass index and survival in women with breast cancer-systematic literature review and meta-analysis of 82 follow-up studies. Ann Oncol. 2014;25(10):1901–1914. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdu042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Scholz C, Andergassen U, Hepp P, Schindlbeck C, Friedl TWP, Harbeck N, Kiechle M, Sommer H, Hauner H, Friese K, Rack B, Janni W. Obesity as an independent risk factor for decreased survival in node-positive high-risk breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2015;151(3):569–576. doi: 10.1007/s10549-015-3422-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Iyengar NM, Chen IC, Zhou XK, Giri DD, Falcone DJ, Winston LA, Wang H, Williams S, Lu YS, Hsueh TH, Cheng AL, Hudis CA, Lin CH, Dannenberg AJ. Adiposity, inflammation, and breast cancer pathogenesis in Asian women. Cancer Prev Res (Phila) 2018;11(4):227–236. doi: 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-17-0283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Uomori T, Horimoto Y, Arakawa A, Iijima K, Saito M. Breast cancer in lean postmenopausal women might have specific pathological features. In Vivo. 2019;33(2):483–487. doi: 10.21873/invivo.11499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stamler R, Ford CE, Stamler J. Why do lean hypertensives have higher mortality rates than other hypertensives? Findings of the Hypertension Detection and Follow-up Program. Hypertension. 1991;17(4):553–564. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.17.4.553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Selmer R, Tverdal A. Body mass index and cardiovascular mortality at different levels of blood pressure: a prospective study of Norwegian men and women. J Epidemiol Community Health. 1995;49(3):265–270. doi: 10.1136/jech.49.3.265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kwon H, Yun JM, Park JH, Cho BL, Han K, Joh HK, Son KY, Cho SH. Incidence of cardiovascular disease and mortality in underweight individuals. J Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle. 2021;12(2):331–338. doi: 10.1002/jcsm.12682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Takada K, Shimokawa M, Akamine T, Ono Y, Haro A, Osoegawa A, Tagawa T, Mori M. Association of low body mass index with poor clinical outcomes after resection of non-small cell lung cancer. Anticancer Res. 2019;39(4):1987–1996. doi: 10.21873/anticanres.13309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Komatsu S, Kosuga T, Kubota T, Okamoto K, Konishi H, Shiozaki A, Fujiwara H, Otsuji E. Preoperative low weight affects long-term outcomes following curative gastrectomy for gastric cancer. Anticancer Res. 2018;38(9):5331–5337. doi: 10.21873/anticanres.12860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Moon HG, Han W, Noh DY. Underweight and breast cancer recurrence and death: a report from the Korean Breast Cancer Society. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(35):5899–5905. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.22.4436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Huisingh-Scheetz M, Walston J. How should older adults with cancer be evaluated for frailty. J Geriatr Oncol. 2017;8(1):8–15. doi: 10.1016/j.jgo.2016.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Minami CA, Cooper Z. The frailty syndrome: A critical issue in geriatric oncology. Crit Care Clin. 2021;37(1):151–174. doi: 10.1016/j.ccc.2020.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sun Q, Jiang X, Qin R, Yang Y, Gong Y, Wang K, Peng J. Sarcopenia among older patients with cancer: A scoping review of the literature. J Geriatr Oncol. 2022;13(7):924–934. doi: 10.1016/j.jgo.2022.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ata AM, Kara M, Kaymak B, Özçakar L. Sarcopenia is not “love”: You have to look where you lost it! Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2020;99(10):e119–e120. doi: 10.1097/PHM.0000000000001391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Beaudart C, Zaaria M, Pasleau F, Reginster JY, Bruyère O. Health outcomes of sarcopenia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2017;12(1):e0169548. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0169548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Argilés JM, Campos N, Lopez-Pedrosa JM, Rueda R, Rodriguez-Mañas L. Skeletal muscle regulates metabolism via interorgan crosstalk: Roles in health and disease. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2016;17(9):789–796. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2016.04.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cesari M, Pahor M, Lauretani F, Zamboni V, Bandinelli S, Bernabei R, Guralnik JM, Ferrucci L. Skeletal muscle and mortality results from the InCHIANTI Study. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2009;64(3):377–384. doi: 10.1093/gerona/gln031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Watanabe D, Yoshida T, Watanabe Y, Yamada Y, Kimura M, Kyoto-Kameoka Study Group A U-shaped relationship between the prevalence of frailty and body mass index in community-dwelling Japanese older adults: The Kyoto-Kameoka study. J Clin Med. 2020;9(5):1367. doi: 10.3390/jcm9051367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Handforth C, Clegg A, Young C, Simpkins S, Seymour MT, Selby PJ, Young J. The prevalence and outcomes of frailty in older cancer patients: a systematic review. Ann Oncol. 2015;26(6):1091–1101. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdu540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dent E, Lien C, Lim WS, Wong WC, Wong CH, Ng TP, Woo J, Dong B, De La Vega S, Hua Poi PJ, Kamaruzzaman SBB, Won C, Chen L, Rockwood K, Arai H, Rodriguez-Mañas L, Cao L, Cesari M, Chan P, Leung E, Landi F, Fried LP, Morley JE, Vellas B, Flicker L. The Asia-Pacific Clinical Practice Guidelines for the management of frailty. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2017;18(7):564–575. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2017.04.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Peterson SJ, Mozer M. Differentiating sarcopenia and cachexia among patients with cancer. Nutr Clin Pract. 2017;32(1):30–39. doi: 10.1177/0884533616680354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Arai H, Satake S. English translation of the Kihon Checklist. Geriatr Gerontol Int. 2015;15(4):518–519. doi: 10.1111/ggi.12397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pijpers E, Ferreira I, van de Laar RJJ, Stehouwer CDA, Nieuwenhuijzen Kruseman AC. Predicting mortality of psychogeriatric patients: a simple prognostic frailty risk score. Postgrad Med J. 2009;85(1007):464–469. doi: 10.1136/pgmj.2008.073353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Searle SD, Mitnitski A, Gahbauer EA, Gill TM, Rockwood K. A standard procedure for creating a frailty index. BMC Geriatr. 2008;8:24. doi: 10.1186/1471-2318-8-24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]