Abstract

The γ-aminobutyric acid–mediated (GABAergic) system participates in many aspects of organismal physiology and disease, including proteostasis, neuronal dysfunction, and life-span extension. Many of these phenotypes are also regulated by reactive oxygen species (ROS), but the redox mechanisms linking the GABAergic system to these phenotypes are not well defined. Here, we report that GABAergic redox signaling cell nonautonomously activates many stress response pathways in Caenorhabditis elegans and enhances vulnerability to proteostasis disease in the absence of oxidative stress. Cell nonautonomous redox activation of the mitochondrial unfolded protein response (mitoUPR) proteostasis network requires UNC-49, a GABAA receptor that we show is activated by hydrogen peroxide. MitoUPR induction by a spinocerebellar ataxia type 3 (SCA3) C. elegans neurodegenerative disease model was similarly dependent on UNC-49 in C. elegans. These results demonstrate a multi-tissue paradigm for redox signaling in the GABAergic system that is transduced via a GABAA receptor to function in cell nonautonomous regulation of health, proteostasis, and disease.

Optogenetics is used to demonstrate the role of GABAergic redox signaling in C. elegans health and disease.

INTRODUCTION

Reactive oxygen species (ROS) and redox biology play multifaceted roles in health and disease and are needed for cellular signaling, homeostasis, and communication in a wide range of cell types and organisms (1, 2). In Caenorhabditis elegans, redox biology plays a functional role in reproduction (3), cuticle structure (4), behavior/environmental sensing (5), and life span (6).

However, important questions in redox biology remain unanswered, especially molecular understanding of the redox signaling that coordinates biological processes and phenotypes across tissues. This is because characterizing tissue-specific redox biology and chemistry in an organismal environment is especially challenging (6–8). First, exogenous oxidants and pro-oxidants (e.g., H2O2, juglone, rotenone, and paraquat) cannot be applied to specific tissues. Second, mutants that have altered redox biology are rarely characterized in a tissue-specific manner. Furthermore, the mitochondrial mutants that display increased mitochondrial ROS and are commonly used (e.g., nuo-6, isp-1, and clk-1) (9, 10) also display additional phenotypes such as altered mitochondrial metabolism that limit clear understanding of redox biology (8, 11). Last, the diverse chemical kinetics, reactivity, and diffusability of each ROS (e.g., hydrogen peroxide, superoxide, hydroxyl radical, and singlet oxygen) can define redox signaling networks (1), but these factors are less explored in multicellular organisms where additional layers of regulation may be present. For example, while charged radicals such as superoxide (O2•−) cannot traverse cell membranes, hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) is a diffusible second messenger with the potential to act cell nonautonomously (12, 13).

Tissue-specific investigation of redox biology has recently become possible via ROS-producing optogenetic proteins such as KillerRed and Supernova (13–15). These optogenetic proteins have been widely used in C. elegans because these animals are optically transparent and tissue-specific promoters are widely available. However, most studies using this technology have focused on oxidative stress to ablate specific cells (15, 16), generate organelle damage, or inactivate specific proteins (17, 18).

C. elegans is ideal for in vivo analysis of redox signaling in specific tissues due to the wide array of behaviors and phenotypes that can be assayed (19, 20). We focused on investigating neuronal redox biology, which is especially dynamic since ROS can be produced in neurons by axonal firing (21), hypoxia (22), altered metabolism (23, 24), and aging (25). ROS are also capable of regulating neuronal processes such as synaptic transmission and plasticity (26, 27). We focused on the γ-aminobutyric acid–mediated (GABAergic) system since mitochondrial ROS has been implicated in strengthening GABA-mediated synaptic transmission (23) and the GABAergic system regulates many processes and organismal phenotypes associated with altered ROS and redox biology, including neurodegeneration (28), proteostasis and protein folding (29, 30), life-span extension (31), and immunity (32). However, while GABAA receptors can be oxidized, it is unclear how their redox regulation is mechanistically linked to these diverse phenotypes (23, 33–35).

Here, we developed an optogenetic platform that enables long-term production of ROS across a full continuum of levels ranging from redox signaling to oxidative stress in many C. elegans individuals simultaneously. We applied this platform to control and sustain ROS production in GABAergic neurons using worms that express KillerRed under the vesicular GABA transporter (unc-47) promoter. In parallel, we assayed a spinocerebellar ataxia type 3 (SCA3) C. elegans neurodegenerative disease model that is associated with increased ROS and proteostasis failure (36, 37). The mitochondrial unfolded protein response (mitoUPR) is cell nonautonomously activated in both strains in a ROS-dependent manner, and this induction required the GABAA receptor UNC-49, which is primarily expressed in neurons (GABAergic, cholinergic, and interneurons) and muscle cells (38–40). Using electrophysiology, we determined that H2O2 increases UNC-49B channel activity independent of GABA and also potentiates the channel activation by GABA. Our results demonstrate a multi-tissue GABAergic redox signaling network that acts via GABAA receptor oxidation to cell nonautonomously regulate stress response signaling and vulnerability to proteostasis disease.

RESULTS

An LED-based optogenetic platform enables investigation of GABAergic redox signaling and oxidative stress

Investigating GABAergic redox biology requires developing an approach to control and sustain ROS production across a continuum of levels ranging from redox signaling to oxidative stress in many C. elegans individuals simultaneously. We used large, white light producing light-emitting diodes (LEDs) controlled by dimmer switches to modulate light intensity (fig. S1, A and B). To optogenetically produce ROS specifically in GABAergic neurons, we used the C. elegans strain we term “GABA-KR” (wpIs15 [unc-47p::KillerRed] X; GABA-KR) that expresses KillerRed (KR) in the cytoplasm of GABAergic neurons using the unc-47 promoter (Fig. 1A) (15). Light activation of KR rapidly damages and permanently inactivates GABAergic neurons, which induces a shrinker phenotype (15). While previous work permanently inactivated neurons using high light intensities (100 to 460 mW/cm2) for a short duration (5 to 120 min) (15), we observed that lower light intensities (0.3 to 3.0 mW/cm2) for longer durations (72 hours) were able to similarly induce neuronal damage in the GABA-KR strain in a light intensity–dependent manner (Fig. 1B).

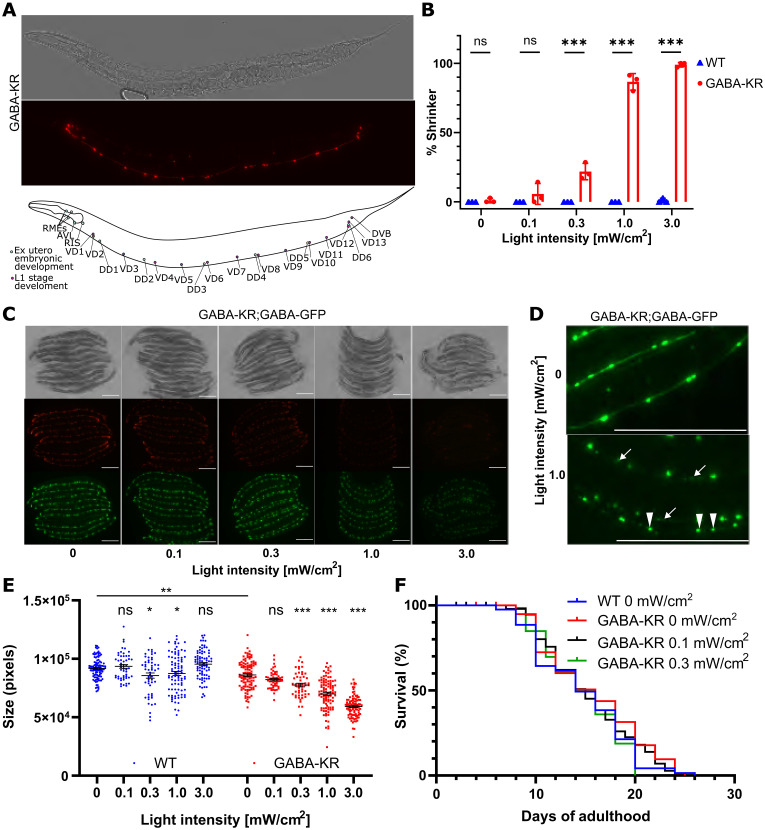

Fig. 1. GABA-KR enables investigation of GABAergic redox signaling and oxidative stress.

(A) GABA-KR strain fluorescent image and schematic, indicating GABA-KR expression in GABAergic neurons under unc-47 promoter. (B) KillerRed activation induces movement defects. Animals were illuminated with LED lights (0 to 3.0 mW/cm2) for 72 hours during development and then scored for the shrinker phenotype caused by GABAergic neuron dysfunction. Three biological replicates, N ≥ 35 per replicate for KillerRed and WT. Ordinary two-way ANOVA with Šídák’s multiple comparison test with a single pooled variance. (C) Brightfield (top) and fluorescent (KR, middle; GFP, bottom) images of the GABAergic neurons of GABA-KR;GABA-GFP (juIs76 [unc-25p::GFP + lin-15(+)] II; wpIs15 [unc-47p]::KillerRed X) animals with 0 to 3.0 mW/cm2 illumination. Scale bar, 200 μm. (D) Enlarged images of 0 (top) and 1.0 mW/cm2 (bottom), showing cell body rounding (solid triangle) neuronal process degeneration and blebbing (arrow). Scale bar 200 μm. (E) Worm size changes induced by GABA-KR, five or more biological replicates, with N ≥ 8 per replicate. Ordinary two-way ANOVA with Šídák’s multiple comparison test, with a single pooled variance to compare WT to GABA-KR and with individual variance computed for each comparison for comparison within strains. (F) Representative life-span curves of GABA-KR worms illuminated with 0 to 0.3 mW/cm2 during development (72 hours) compared to WT worms (0 mW/cm2). Kaplan-Meier simple survival analysis with log-rank (Mantel-Cox) test.

Since light can induce heat, and temperature can influence many aspects of C. elegans’ physiology (41), we routinely measured the temperature of the nematode growth medium (NGM) dishes that worms were cultured on. There was no increase in temperature at ≤1.0 mW/cm2 light, but 3.0 mW/cm2 light increased the temperature by 1°C (fig. S1C). We additionally verified that environmental conditions were stable using the temperature-sensitive hsp-16.2p::GFP reporter strain (42). No increase in hsp-16.2p::GFP expression was observed at light conditions ≤1.0 mW/cm2, but 3.0 mW/cm2 caused a small, but significant, increase in green fluorescent protein (GFP) expression (fig. S1D).

The ROS produced by ≥1.0 mW/cm2 light induced phenotypes consistent with oxidative stress. For example, worms exposed to 1.0 or 3.0 mW/cm2 displayed abnormal neuronal morphology and fragmentation of neuronal processes including blebbing and pearling as well as smaller and rounder cell bodies (Fig. 1, C and D). These light intensities also decreased the overall size of the GABA-KR worms (Fig. 1E) and altered tissue morphology (Fig. 1C) in a light intensity–dependent manner, which was not observed in wild-type (WT) worms. In contrast, worms exposed to light conditions ≤0.3 mW/cm2 displayed no neuronal damage or tissue abnormalities (Fig. 1C), and the number of animals displaying a shrinker phenotype was only modestly increased (Fig. 1B). To test whether light intensity between 0 and 0.3 mW/cm2 affected C. elegans health, we measured life span. Light intensities of 0 to 0.3 mW/cm2 did not alter life span (Fig. 1F and fig. S1E). These results indicate that this optogenetic platform enables analysis of the full continuum of ROS levels to study redox biology, with ≤0.1 mW/cm2 light producing ROS consistent with redox signaling (43, 44) that did not cause detrimental health effects. At the other end of the redox spectrum, light intensities ≥1.0 mW/cm2 induced oxidative stress, damaged neuronal morphology and function, and caused detrimental consequences for worm size and tissue morphology.

GABA-KR redox signaling activates diverse stress response pathways cell nonautonomously

We used this optogenetic platform to investigate whether ROS and redox signaling in GABA neurons activates specific stress response pathways at 0 to 3.0 mW/cm2 light intensities using four well-characterized GFP reporter strains: daf-16 (TJ356), sod-3 (CF1553), gst-4 (CL2166), and hsp-6 (SJ4100). DAF-16 is a FoxO transcription factor that mediates stress resistance by translocating from the cytoplasm to the nucleus when activated (45, 46). SOD-3 (superoxide dismutase 3) is a mitochondrial manganese superoxide dismutase that counteracts ROS accumulation by detoxifying superoxide (47). Glutathione S-transferase-4 (GST-4) is a homolog of human sigma GSTs that mitigates oxidative stress by conjugating reduced glutathione (GSH) to electrophiles (48). HSP-6 is the ortholog of human mitochondrial heat shock protein 70 (mthsp70) and a specific mediator of the mitoUPR that regulates proteostasis (49, 50).

Chronic ROS production (72 hours) in GABAergic neurons differentially activated distinct stress responses. For example, daf16p::daf-16a/b::GFP nuclear translocation was not reliably altered by GABA-KR at the three light intensities evaluated (fig. S2A). However, GFP expression in the three other reporter strains was significantly up-regulated in GABA-KR strains compared to control strains that do not express GABA-KR (Fig. 2, A to C). The sod-3p::GFP, gst-4p::GFP, and hsp-6p::GFP reporters were all very sensitive to ROS in GABAergic neurons and activated by the 0 mW/cm2 condition, where light was limited as much as experimentally possible. This is likely because fluorescent proteins such as KR and enhanced GFP (eGFP) produce some ROS even in the absence of light stimulation during chromophore maturation (18, 49, 51). We observed a light-dependent increase in sod-3p::GFP expression in the presence of GABA-KR, while sod-3p::GFP expression changed minimally in the absence of GABA-KR under all light conditions (Fig. 2A). In contrast, gst-4p::GFP expression decreased in the presence of GABA-KR at light intensities corresponding to oxidative stress (Fig. 2B), likely due to oxidative inactivation of this pathway (52).

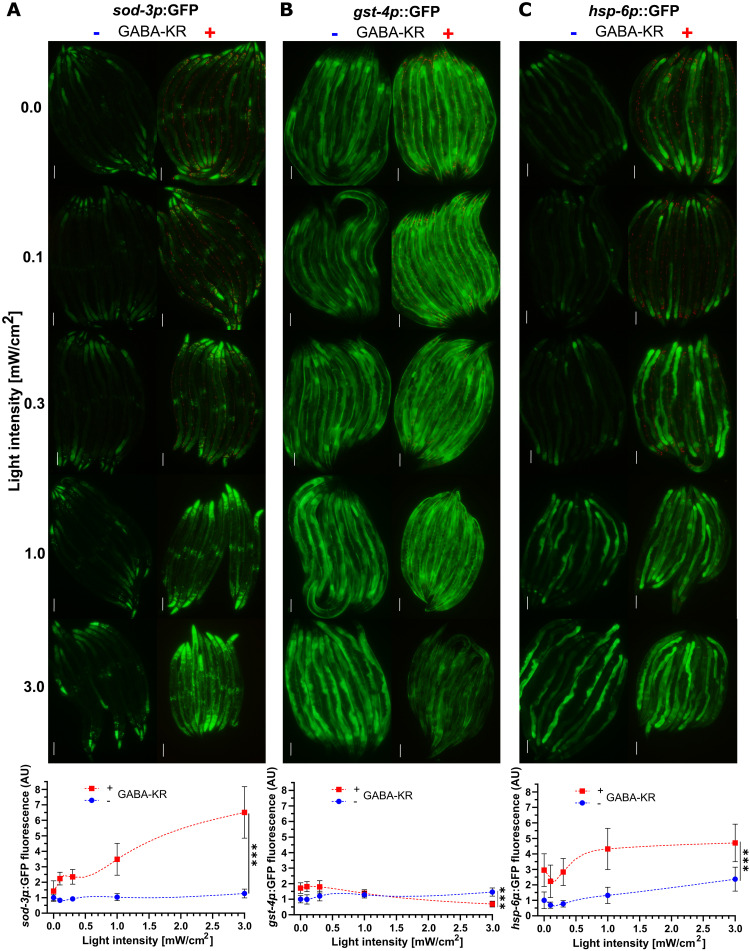

Fig. 2. GABA-KR activates stress response pathways with a diversity of responses.

(A) Top: Fluorescent microscope images of multiple sod-3p::GFP worms in the absence (left) and presence (right) of GABA-KR between 0 and 3.0 mW/cm2. Bottom: GFP intensity measurements of sod-3p::GFP in the presence (red, square) and absence (blue, circle) of GABA-KR between 0 and 3.0 mW/cm2 (B) Top: Fluorescent microscope images of multiple gst-4p::GFP worms in the absence (left) and presence (right) of GABA-KR between 0 and 3.0 mW/cm2. Bottom: GFP intensity measurements of gst-4p::GFP in the presence (red, square) and absence (blue, circle) of GABA-KR between 0 and 3.0 mW/cm2 (C) Top: Fluorescent microscope images of multiple hsp-6p::GFP worms in the absence (left) and presence (right) of GABA-KR between 0 and 3.0 mW/cm2. Bottom: GFP intensity measurements of hsp-6::GFP in the presence (red, square) and absence (blue, circle) of GABA-KR between 0 and 3.0 mW/cm2. All fluorescence intensities were normalized to the respective reporter control at 0 mW/cm2 and analyzed using ordinary two-way ANOVA to compare the curves, showing mean ± SD of three or more biological replicates with N ≥ 6 for each replicate/condition. Curves created using LOWESS, 10 points in smoothing window. AU, arbitrary units.

The hsp-6p::GFP reporter of the mitoUPR had the largest fold change by GABA-KR (Fig. 2C), consistent with its known sensitivity to exogenous addition of the ROS generators paraquat, antimycin A, and rotenone (53, 54) and by ROS produced optogenetically in the mitochondrial outer membrane of muscle, intestinal, and neuronal cells (18). In contrast to sod-3p::GFP and gst-4p::GFP, induction of hsp-6p::GFP by GABA-KR was stable at all light intensities.

To determine whether cell nonautonomous activation of stress response pathway was specific to the GABAergic system, we crossed the sod-3p::GFP and hsp-6p::GFP reporter into a strain that expresses KR in cholinergic neurons under the unc-17 promoter (cholinergic-KR; wpIs14 [unc-17p::KillerRed + unc-122p::GFP]) (fig. S2B) (15). In contrast to GABA-KR, stimulation with 0 to 3.0 mW/cm2 light in the cholinergic-KR strain did not activate sod-3p::GFP expression (fig. S2C) or hsp-6p::GFP (fig. S2D).

GABA-KR cell nonautonomously activates the mitoUPR proteostasis network

Since the mitoUPR plays a potential role in many disease-relevant processes, we further investigated its activation by GABAergic redox signaling. First, Western blot analysis confirmed the GABA-KR–dependent increase in hsp-6p::GFP expression (Fig. 3A). Image analysis showed that increased hsp-6p::GFP expression occurs primarily in the intestine, not the GABAergic neurons where KR is expressed (Fig. 3B). We also observed cell nonautonomous activation of mitoUPR by GABA-KR using the translational reporter for dve-1 [dve-1p::dve-1::GFP (55)], a transcription factor that translocates to the nucleus upon mitoUPR activation (Fig. 3C) (55). GABA-KR significantly increased the number of cells with nuclear dve-1p::dve-1::GFP (Fig. 3, D and E), primarily in intestinal cells as observed for hsp-6p::GFP expression (Figs. 2C and 3B). GABA-KR–dependent DVE-1 nuclear localization was also observed in smaller nuclei in cells close to body wall muscle cells. These results demonstrate that redox signaling in GABAergic neurons is sufficient to activate proteostasis and stress response networks cell nonautonomously.

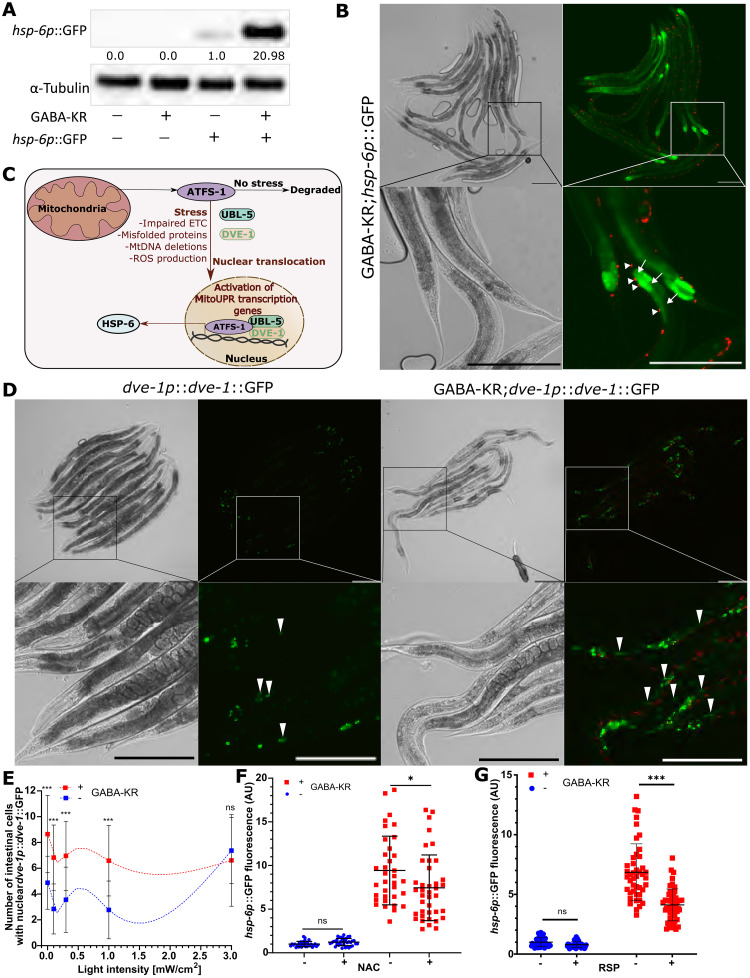

Fig. 3. GABA-KR sufficient to activate mitoUPR cell nonautonomously (ROS dependent).

(A) Western blot of hsp-6p::GFP in the absence (−) and presence (+) of GABA-KR and respective control strains in the presence (+) and absence (−) of hsp-6p::GFP. Values indicate the hsp-6p::GFP/α-tubulin ratio changes normalized to the hsp-6p::GFP control. (B) Brightfield (left) and fluorescent (right) microscope images of GABA-KR;hsp-6p::GFP strains. Top: Full-image 10× magnification. Bottom: Enlarged image highlights cell nonautonomous activation. Arrowheads point at KR in GABAergic neurons, while arrows point at hsp-6p::GFP expression in intestines. Scale bar, 200 μm. (C) Schematic of hsp-6 regulation by atfs-1 and through ubl-5 and dve-1 (89). (D) Brightfield (left) and fluorescent (right) microscope images of dve-1p::dve-1::GFP and GABA-KR;dve-1p::dve-1::GFP strains. Top: Full-image 10× magnification. Bottom: Enlarged image highlights cell nonautonomous activation. Arrowheads point at intestinal nuclear dve-1p::dve-1::GFP expression. Scale bar, 200 μm. (E) Number of intestinal cells with nuclear GFP in dve-1p::dve-1::GFP versus dve-1p::dve-1::GFP;GABA-KR worms; mean ± SD; ordinary two-way ANOVA and Bonferroni’s multiple comparison test with a single pooled variance. Curves created using LOWESS, 10 points in smoothing window. (F) hsp-6p::GFP expression in the presence (+) and absence (−) of GABA-KR and treatment with (+) or without (−) N-acetylcysteine (NAC; 5 mM); mean ± SD; ordinary two-way ANOVA and Tukey’s multiple comparison test with a single pooled variance. (G) hsp-6p::GFP expression in the presence (+) and absence (−) of GABA-KR and treatment with (+) or without (−) rapeseed pomace (RSP) extract (1 mg/ml); mean ± SD; ordinary two-way ANOVA and Tukey’s multiple comparison test with a single pooled variance.

To determine whether mitoUPR induction depended on the ROS produced by GABA-KR, we treated hsp-6p::GFP and GABA-KR;hsp-6p::GFP with N-acetylcysteine (NAC), a common antioxidant and U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA)–approved drug (56). Treatment of the GABA-KR;hsp-6p::GFP strain with 5 mM NAC significantly reduced hsp-6p::GFP fluorescence (Fig. 3F), demonstrating that ROS mediate the increased mitoUPR expression caused by GABA-KR. No change was observed in hsp-6p::GFP expression following NAC treatment for the control reporter strain without GABA-KR. To verify this ROS dependence, we also used an extract from rapeseed/canola pomace (RSP extract) that has been shown to have antioxidant activity in vitro (57–59) and in vivo (37). Treatment with the RSP extract also significantly decreased mitoUPR expression of GABA-KR;hsp-6p::GFP worms (Fig. 3G). To determine whether hsp-6p::GFP fluorescence is increased due to KR-induced ROS production, we used a strain that expresses GFP in GABAergic neurons oxIs12 [unc-47p::GFP + lin-15(+)] (60). Due to its structure, GFP is less likely to create ROS than KR (13, 61). Expression of GFP in GABAergic neurons was not sufficient to induce hsp-6p::GFP expression (fig. S3). These results demonstrate that ROS produced in GABAergic neurons is required for cell nonautonomous activation of mitoUPR.

The GABAA receptor UNC-49 is required for activation of the mitoUPR by redox signaling, but GABA synthesis is not

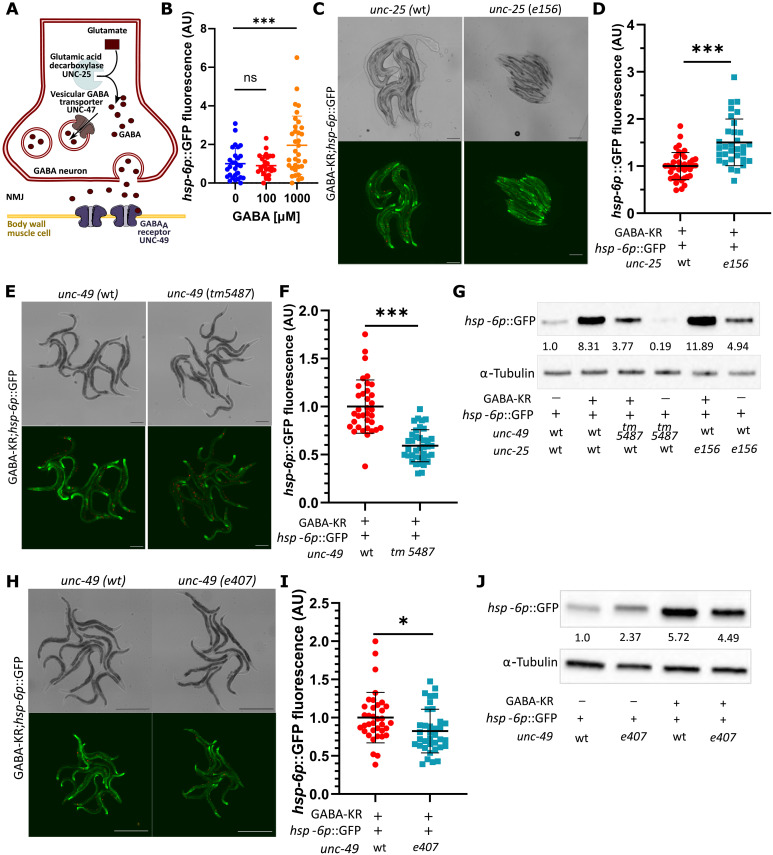

We hypothesized that GABA-KR–dependent activation of the mitoUPR required a canonical component of the C. elegans GABAergic system (Fig. 4A). Treatment with exogenous, nontoxic concentrations of GABA was sufficient to increase hsp-6p::GFP expression (Fig. 4B and fig. S4A), indicating that GABA neurotransmission was sufficient to activate the mitoUPR. To determine whether the increased mitoUPR expression by GABAergic ROS required endogenous GABA synthesis, we crossed the GABA-KR;hsp-6p::GFP strain with an unc-25(e156) mutant strain that lacks the sole C. elegans glutamic acid decarboxylase enzyme that is required for GABA synthesis (Fig. 4A). Loss of unc-25 did not decrease, and even increased, hsp-6p::GFP by GABA-KR as measured by both imaging (Fig. 4, C and D) and Western blot (Fig. 4G) in the dark and with 0.1 and 0.3 mW/cm2 light (fig. S4B). Therefore, GABA synthesis was not required for induction of mitoUPR.

Fig. 4. GABA-KR activation of mitoUPR requires GABAA receptor UNC-49 but is not dependent on GABA synthesis.

(A) Schema of GABA production/synaptic transmission. Genes of interest: unc-47 (GABA vesicular transporter), unc-25 (glutamic acid decarboxylase, necessary for GABA production), and unc-49 (inhibitory GABAA receptor). NMJ, neuromuscular junction; GABA, γ-aminobutyric acid (90). (B) GFP fluorescence expression of hsp-6p::GFP reporter strains treated with 0, 100, and 1000 μM GABA; mean ± SD; ordinary one-way ANOVA and Dunnett’s multiple comparison test, with single pooled variance; three or more biological replicates with N ≥ 6 for each condition. (C) Fluorescent (bottom) and brightfield (top) images of hsp-6p::GFP expression in GABA-KR;hsp-6p::GFP (left) and GABA-KR;hsp-6p::GFP;unc-25(e156) (right). Scale bar, 200 μm. (D) GFP fluorescence expression in GABA-KR;hsp-6p::GFP strain with WT unc-25 or mutant unc-25(e156). Unpaired t test; mean ± SD; three or more biological replicates with N ≥ 6 for each condition. (E) Fluorescent (bottom) and brightfield (top) images of hsp-6p::GFP expression in GABA-KR;hsp-6p::GFP (left) and GABA-KR;hsp-6p::GFP;unc-49(tm5487) (right). Scale bar, 200 μm. (F) GFP fluorescence expression in GABA-KR;hsp-6p::GFP strain with WT unc-49 or mutant unc-49(tm5487). Unpaired t test; mean ± SD; three or more biological replicates with N ≥ 6 for each condition. (G) Western blot of hsp-6p::GFP expression in GABA-KR;hsp-6p::GFP worms in the presence of unc-25(e156) or unc-49(tm5487) with respective controls; representative of two biological replicates. (H) Fluorescent (bottom) and brightfield (top) images of hsp-6p::GFP in GABA-KR;hsp-6p::GFP (left) and GABA-KR;hsp-6p::GFP;unc-49 (e407) (right). Scale bar, 500 μm. (I) GFP fluorescence expression in GABA-KR;hsp-6p::GFP strain with WT unc-49 or mutant unc-49(e407). Unpaired t test; mean ± SD; three or more biological replicates with N ≥ 6 for each condition. (J) Western blot of hsp-6p::GFP expression in GABA-KR;hsp-6p::GFP worms in unc-49(+) and mutant unc-49(e407) strains; representative of two biological replicates. WBs, Western blots: Values indicate the hsp-6p::GFP/α-tubulin ratios normalized to hsp-6p::GFP.

In contrast to GABA synthesis mutants, unc-49(tm5487) mutants that lack the GABAA receptor UNC-49 (39) displayed a significant reduction in hsp-6p::GFP expression in the GABA-KR background in the dark (Fig. 4, E to G) and with 0.1 and 0.3 mW/cm2 light (fig. S4C). To investigate whether these results were allele specific, since the unc-49(tm5487) mutation is a 302–base pair (bp) deletion of unc-49 covering exons 7 and 8, we used a second unc-49 mutation, unc-49(e407), which is a nonsense mutation that causes an early stop codon in exon 5. unc-49(e407) mutants also displayed significantly reduced hsp-6p::GFP expression in the GABA-KR strain in the dark (Fig. 4, H to J) and with 0.1 and 0.3 mW/cm2 light (fig. S4D). To determine whether this expression decrease could be due to a decrease in KR expression, we measured KR expression in WT animals as well as unc-49 mutants. The results show that there is no significant change in KR expression (fig. S4, E and F). To determine whether unc-49 was required for the activation of other stress response pathways, we measured sod-3p::GFP expression in unc-49(tm5487) animals. Expression of sod-3p::GFP was increased in unc-49(tm5487) mutants (fig. S4G), suggesting that unc-49 is not required for sod-3 activation by GABA-KR and may even suppress it. Hence, unc-49 is required for mitoUPR activation, whereas unc-25 and GABA synthesis is not required. This suggested that ROS may activate UNC-49 channel activity in a GABA-independent manner.

H2O2 increases UNC-49B channel activity

We next sought to determine the molecular mechanism of UNC-49 activation by ROS in GABAergic neurons, which we hypothesized involved redox regulation of the UNC-49 GABAA receptor itself. Historically, the original studies of unc-49 reported a single promotor that controls the expression of three UNC-49 protein isoforms (Table 1) (39). Notably, many more UNC-49 isoforms have been detected since, and naming of UNC-49 isoforms in Wormbase (62) is inconsistent with those used in some of the literature. Here, we refer to UNC-49 isoforms using the Wormbase nomenclature and provide Table 1 for clarification. UNC-49C is considered the canonical UNC-49 isoform, but heteromerization with UNC-49F can modulate UNC-49C channel in response to GABAA receptor–modulating drugs compared to the homomer (38, 39).

Table 1. C. elegans UNC-49 isoforms and their naming differences.

| Wormbase* (this manuscript) | Previous publications (39) |

|---|---|

| UNC-49B (T21C12.1b) | UNC-49A |

| UNC-49C (T21C12.1c) | UNC-49B |

| UNC-49F (T21C12.1f) | UNC-49C |

We investigated redox activation of UNC-49 using two-electrode voltage clamp electrophysiology in Xenopus oocytes. GABA activated both UNC-49B and UNC-49C when expressed individually, demonstrating their functionality as homopentamers (Fig. 5A and fig. S5, A, B, and D).

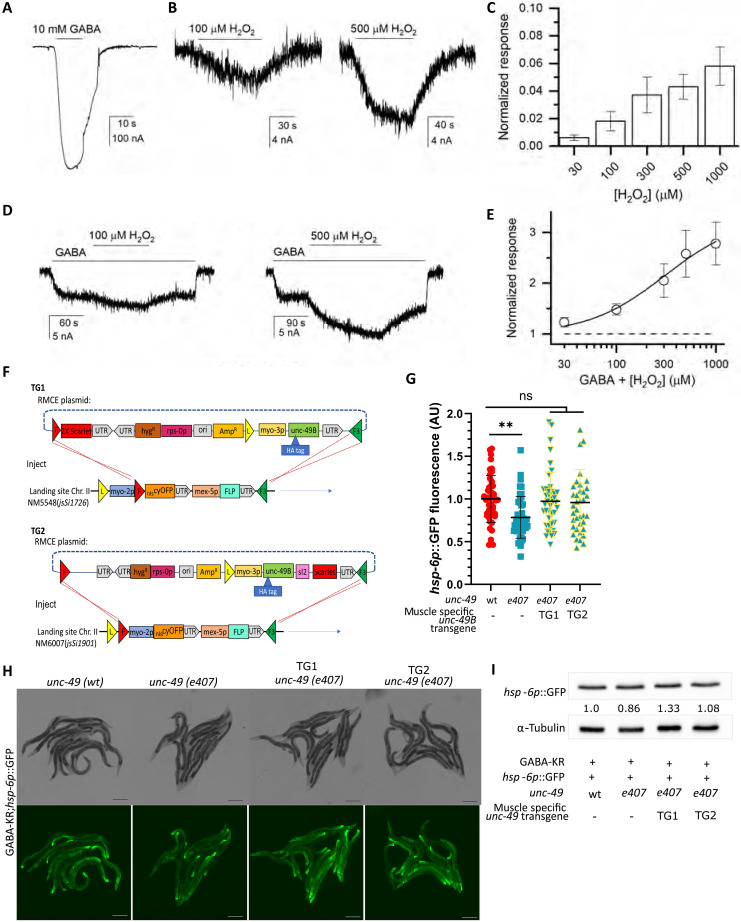

Fig. 5. H2O2 activates channel activity of UNC-49B.

(A) Representative trace from an oocyte expressing UNC-49B exposed to 10 mM (saturating) GABA. Black line: Period of GABA exposure. (B) Representative traces from the same oocyte exposed to 100/500 μM H2O2. (C) Summary of H2O2 direct activation data; mean ± SEM (n = 5 to 9 cells/concentration) of current responses normalized to the response to 10 mM GABA in the same cell. (D) Representative traces from an oocyte expressing UNC-49B, showing H2O2-induced potentiation of responses to low (300 to 500 μM; EC3) GABA. (E) H2O2 concentration-response relationship for potentiation of GABA-activated receptors; mean ± SEM for potentiation (1 = no effect), five cells. The curve shows a fit of pooled data to the Hill equation with an offset constrained to 1. Fitting the potentiation concentration-response curve for UNC-49 yielded a maximal response of 3.3 ± 0.6 (best-fit parameter ± SE of the fit; 1 = no effect), EC50 of 311 ± 165 μM, and a Hill coefficient of 1.12 ± 0.34. (F) Transgene creation and injection for reexpression of UNC-49B in muscle cells. Colored triangles represent loxP (yellow), FRT (red), and FRT3 (green) recombinase sites. Resulting plasmids were injected into WT or hsp-6p::GFP;GABA-KR;unc-49(e407) animals with the landing site on Chr II. (G) GFP fluorescence expression in GABA-KR;hsp-6p::GFP strain with WT or mutant unc-49(tm5487) in the presence/absence of TG1/TG2. Ordinary one-way ANOVA and Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test, with a single pooled variance, mean ± SD, three or more biological replicates with N ≥ 10 for each condition. (H) Fluorescent (bottom) and brightfield (top) images of hsp-6p::GFP expression in GABA-KR;hsp-6p::GFP (left) and GABA-KR;hsp-6p::GFP;unc-49(tm5487) (right). Scale bar, 200 μm. (I) Western blot of hsp-6p::GFP expression in GABA-KR;hsp-6p::GFP worms in WT and mutant unc-49(e407) strains and in the presence/absence of TG1/TG2; one biological replicate. Values indicate the hsp-6p::GFP/α-tubulin ratio normalized to GABA-KR;hsp-6p::GFP.

We next investigated the redox regulation of UNC-49 isoforms. The UNC-49C homomer and the heteromeric UNC-49C/UNC-49F receptors did not respond to treatment with up to 500 μM H2O2 (fig. S5, A, B, and D). In contrast, the UNC-49B receptor was directly activated by as little as 30 μM H2O2 (Fig. 5, B and C) as observed for the human ρ1 GABAA receptors (fig. S5C), which was used as positive control. In uninjected Xenopus laevis oocytes, exposure to 30 to 500 μM H2O2 generated minimal (less than 1.6 nA, total n = 5 oocytes) change in holding current, indicating that the responses observed originate from the GABAA receptor. We next investigated whether H2O2 modulated UNC-49B channel activity elicited by GABA and found that H2O2 exposure potentiated the response to GABA (Fig. 5D). The normalized potentiation concentration-response curve was fitted with the Hill equation, yielding a fitted maximal response of 3.3 ± 0.6 (best-fit parameter ± SE of the fit; 1 = no effect), an EC50 (median effective concentration) of 311 ± 165 μM, and a Hill coefficient of 1.12 ± 0.34 (Fig. 5E).

These results demonstrate that UNC-49B can be redox-activated, consistent with our model that ROS produced in GABAergic neurons induce mitoUPR and hsp-6p::GFP expression via oxidation of UNC-49.

Muscle-specific UNC-49B expression rescues the decrease in mitoUPR activation caused by unc-49 mutations

UNC-49 is primarily expressed in neurons and muscle cells (fig. S5, E and F) (38–40). During locomotion, the role of UNC-49 in the 19 ventral cord D-type neurons is to inhibit the contraction of body wall muscle cells. Due to the importance of UNC-49 function in muscle cells, we investigated whether reexpression of UNC-49B solely in muscle cells could rescue the decreased hsp-6p::GFP expression we observed in unc-49(e407) mutants.

Two independent strains and transgenes were generated. The TG1 strain expressed UNC-49B and scarlet under the myo-3 and myo-2 promoters, respectively. TG2 expressed UNC-49B under the myo-3 promoter with coexpression of scarlet in muscle (Fig. 5F and tables S2 to S5). Compared to the unc-49 mutant GABA-KR;hsp-6p::GFP;unc-49(e407) control strain, we observed that both TG1 and TG2 significantly rescued the decrease in mitoUPR expression caused by unc-49 mutation (Fig. 5, G and H) back to the levels of the GABA-KR;hsp-6p::GFP–positive control based on imaging and Western blot analysis (Fig. 5I). Hence, expression of UNC-49B in muscle cells is sufficient to rescue the mitoUPR phenotype.

GABAergic redox signaling induces vulnerability to proteostasis disease

The stress response pathways activated by low amounts of ROS in GABA neurons, including mitoUPR, SOD-3, and GST-4 (Fig. 2), are often considered to be cytoprotective and hormetic (63). We therefore hypothesized that activation of stress responses by GABA-KR would improve proteostasis-related disease phenotypes. To test this, we first used the GMC101 strain that expresses full-length human amyloid-β (Aβ)1–42 in C. elegans body wall muscle cells, where Aβ1–42 can oligomerize, aggregate, and induce age-progressive paralysis at 25°C (64). This strain displays increased ROS production (65), and Aβ proteotoxicity is reduced by enhanced mitochondrial proteostasis (66), suggesting that activation of the mitoUPR by GABAergic redox signaling might alleviate the disease phenotype. However, the number of paralyzed worms 12 to 24 hours after induction of proteostatic stress by temperature upshift was significantly increased in the presence of GABAergic KR under low light conditions (Fig. 6A). To test whether GABAergic redox signaling induced vulnerability to other proteostasis diseases, we next evaluated the motility phenotype of a spinocerebellar ataxia (SCA3) strain that overexpresses the aggregation-prone human ATXN3 protein in all neurons as either WT ATXN3, with 14 CAG repeats (AT3q14), or expanded ATXN3, with 75 or 130 CAG repeats (AT3q75 and AT3q130), in all C. elegans neurons (67). Coexpression of GABA-KR in the AT3q14 and AT3q130 strains worsened motility under light conditions (0 mW/cm2) that do not induce deleterious phenotypes or oxidative stress in GABA-KR worms (Fig. 6B) and hence seem to induce neuronal vulnerability. These studies indicate that GABAergic redox signaling induces vulnerability to proteostasis disease in neurodegenerative models.

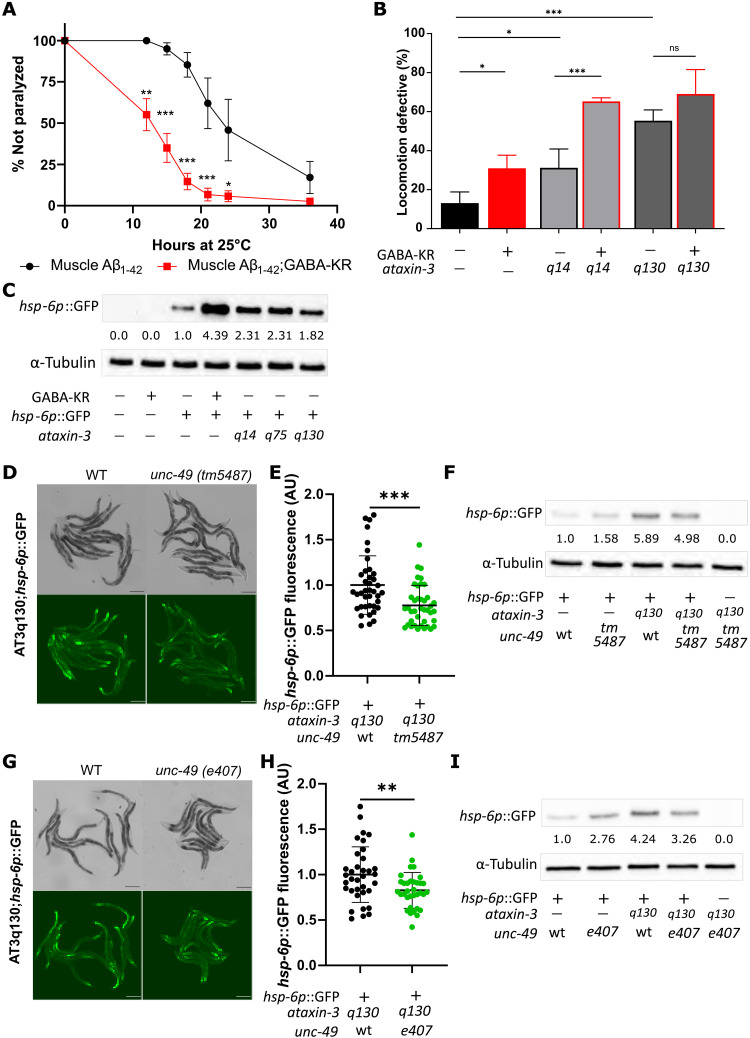

Fig. 6. SCA3 activation of mitoUPR depends on UNC-49, and GABA-KR is detrimental for neurodegeneration phenotypes.

(A) Age-related paralysis phenotype in GMC101, body wall muscle Aβ1–42–expressing C. elegans. Plotted are the mean fractions of individuals not paralyzed ± SEM, four biological replicates with N = 45 per experiment per strain, ordinary two-way ANOVA and Tukey’s multiple comparison test, with individual variance computed for each comparison. (B) Comparison of locomotion-defective behavior of WT (blue), GABA-KR (red), and AT3q14 and AT3q130 in the absence (black) and presence (red) of GABA-KR; mean ± SD; four biological replicates with N ≥ 38 per experiment per strain, ordinary two-way ANOVA and Tukey’s multiple comparison test, with single pooled variance. (C) Western blot analysis of hsp-6p:GFP expression in SCA3 AT3q14, q75, and q130 models compared to GABA-KR;hsp-6p:GFP and other respective controls; representative of two biological replicates. Values indicate the hsp-6p:GFP/α-tubulin ratio changes normalized to the hsp-6p:GFP control. (D) Brightfield and fluorescent image examples of AT3q130;hsp-6p:GFP expression in WT and mutant unc-49(tm5487) strains. Scale bar, 200 μm. (E) GFP fluorescence expression in AT3q130;hsp-6p:GFP strain with WT or mutant unc-49(tm5487); mean ± SD, unpaired t test, three biological replicates with N ≥ 10 per strain and replicate. (F) Western blot analysis of AT3q130;hsp-6p:GFP expression in the presence or absence of unc-49(tm5487) mutation; three biological replicates. Values indicate the hsp-6p:GFP/α-tubulin ratio changes normalized to the hsp-6p:GFP control. (G) Brightfield and fluorescent image examples of AT3q130;hsp-6p::GFP expression in unc-49(+) and mutant unc-49(e407) strains. Scale bar, 200 μm. (H) GFP fluorescence expression in AT3q130;hsp-6p:GFP strain with unc-49(+) or mutant unc-49(e407), mean ± SD, unpaired t test, three biological replicates with N ≥ 10 per strain and replicate. (I) Western blot analysis of AT3q130;hsp-6p:GFP expression in unc-49(+) and mutant unc-49(e407) strains; representative of three biological replicates. Values indicate the hsp-6p:GFP/α-tubulin ratio changes normalized to the hsp-6p:GFP control.

Activation of the mitoUPR by a spinocerebellar ataxia neurodegenerative disease model requires unc-49

We hypothesized that GABAergic redox signaling and UNC-49 may function in proteostasis and neurodegenerative disease since cell nonautonomous activation of mitoUPR was observed in response to pan-neuronal expression of the aggregation-prone Q40 protein, an artificial polyQ tract made up of 40 glutamines (Q40) (49). In addition, altered ROS levels and redox biology are often associated with neurodegeneration, especially diseases of protein aggregation (36, 49, 68). The GABAergic system has also been shown to contribute to neurodegeneration since an SCA3 disease model expressing mutant ataxin-3 (ATXN3) with 89 CAG repeats displays increased ROS levels, decreased life span, and neurodegeneration (36).

To determine whether physiologically relevant polyQ neurodegeneration models activate the mitoUPR expression in a ROS- and UNC-49–dependent manner, we used the pan-neuronal SCA3 C. elegans disease model (67), since the model displays a motility defect and a polyQ length-dependent increase in protein aggregation (67), which can be alleviated with antioxidant treatment, implicating ROS in the disease etiology (37).

All three SCA3 strains (AT3q14, AT3q75, and AT3q130) displayed increased mitoUPR as assessed by hsp-6p::GFP expression (Fig. 6C and fig. S6A). To test whether mitoUPR activation was dependent on ROS, we treated the strains expressing AT3q14;hsp-6p::GFP and AT3q130;hsp-6p::GFP with the RSP antioxidant extract. The antioxidant extract significantly decreased mitoUPR activation in the AT3q14 and AT3q130 hsp-6p::GFP model (fig. S6, B and C), indicating that ROS is required to activate the mitoUPR. To determine whether the SCA3-dependent increase in mitoUPR also required unc-49, we crossed the more disease-relevant AT3q130 polyQ expansion model with both unc-49 mutations (e407 and tm5487). These loss-of-function unc-49 mutations significantly decreased hsp-6p::GFP levels by 23% and 18% (Fig. 6, D to I), respectively. These results demonstrate that unc-49 is required for cell nonautonomous activation of the mitoUPR by a pan-neuronal model of proteostasis disease as well as GABAergic redox signaling.

DISCUSSION

Technological advances enable tissue-specific investigation of ROS at levels ranging from redox signaling to oxidative stress

New technologies to probe the complex chemistry and biology of oxidation-reduction reactions in cells and organisms are often the rate-limiting step to conceptual advances in redox biology (69, 70). Important new tools include sensors for specific types of ROS, redox couples, and oxidized proteins (13, 70).

Optogenetic tools have revolutionized spatiotemporal control of ROS production (13, 14, 71). While these tools have primarily been used to study oxidative stress, cell ablation, or protein inhibition (e.g., CALI) (15, 17, 71), studies such as ours and others indicate that they are useful to investigate spatial aspects of redox signaling as well (18, 72). As a transparent, multicellular organism, C. elegans is ideally suited to provide new insights into many aspects of redox biology and signaling, especially those that are tissue-specific or are integrated across multiple tissues. C. elegans has many endogenous sources of ROS that are known to be functionally involved in diverse biological processes, including BLI-3, KRI-1, and GLB-12, as well as the mitochondria (2). The spatiotemporal control afforded by optogenetics is ideal to investigate how endogenous ROS mechanistically contribute to varied biological processes.

Our study advanced optogenetic approaches by enabling long-term production of ROS across a full continuum of levels from redox signaling to oxidative stress in many C. elegans worms and strains at the same time. Our use of low-cost LED lights is advantageous compared to more commonly used mercury bulbs, liquid light guides, or microscopy-based light delivery that can only be used to study a few worms at a time (15, 17, 72). High-throughput optogenetic platforms such as the one described here, and by others, will substantially advance research in redox biology (73). As we demonstrate in this study, precise control of ROS levels enables one to determine whether ROS promotes disease via damaging oxidative stress versus regulation of signaling and cellular processes that can both positively and negatively regulate neuronal and organismal health (50, 74, 75).

The GABAergic system is redox-regulated

The GABAergic system regulates many organismal phenotypes associated with ROS and redox biology (33), and components of GABA neurotransmission are known to be redox regulated (23, 33–35). However, the molecular mechanisms linking GABAergic redox signaling with these downstream phenotypes are not well understood.

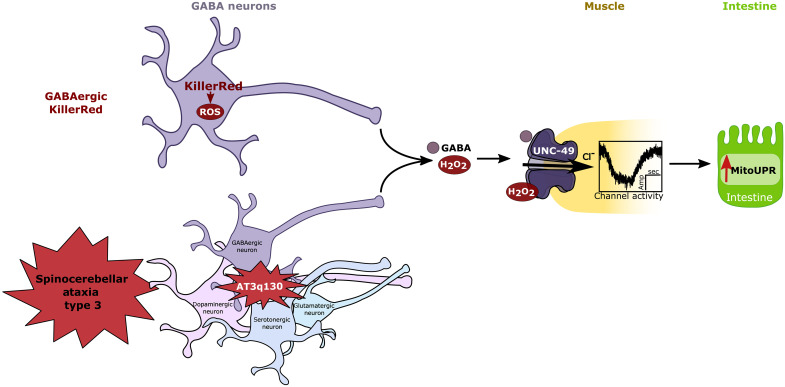

In this study, we demonstrate that the GABAA receptor UNC-49 is required for the cell nonautonomous activation of the mitoUPR in response to increased ROS in GABA neurons and a pan-neuronal SCA3 proteostasis disease model. We also demonstrate that UNC-49B expression in muscle cells can rescue mutation of unc-49, and that UNC-49B channel activity is redox-activated by H2O2 in a transmitter-independent manner. While these results do not delineate which subtype of GABA neurons is involved, these results support a model of GABAergic redox signaling whereby H2O2 is released from GABA neurons and diffuses to muscle cells to redox-activate UNC-49 channel opening to ultimately induce the mitoUPR (Fig. 7). The pentameric ligand gated ion channel (pLGIC) superfamily, which includes GABA receptors, contributes to virtually all functions of the central nervous system (76); therefore, our discovery that redox regulation of UNC-49 increases channel activity suggests a redox mechanism explaining how H2O2 regulates such a diverse array of neuronal phenotypes, including addiction, neuroprotection, pain, cognition, and aging (26, 27, 77).

Fig. 7. Model of how GABAergic ROS and UNC-49 mediate cell nonautonomous activation of the mitoUPR in C. elegans.

UNC-49 is required for cell nonautonomous activation of the mitoUPR in response to ROS produced in GABA neurons and neuronal ROS produced in an ataxia disease model (AT3q130). UNC-49B channel activity is sensitive to H2O2. These results indicate that redox activation of UNC-49 is an important mediator of redox signaling across tissues.

Redox signaling cell nonautonomously activates the mitoUPR via UNC-49

The mitoUPR has been shown to be activated by several factors in neurons including serotonin, the neuropeptide FLP-2, and Wnt/EGL-20 signaling (18, 49, 78). Our results indicate that GABAergic neurons can participate in mitoUPR as well. Notably, the mechanisms downstream of neurons that transduce cell nonautonomous activation of mitoUPR are relatively unknown besides the frizzled receptor in the intestine that is downstream of Wnt/EGL-20 signaling (49). Our results demonstrate that UNC-49 is a mediator of cell nonautonomous mitoUPR activation, and its location in muscle cells suggests that additional tissues may be involved in organism-wide coordination of this important proteostasis network. Notably, UNC-49 has previously been shown to play an important role in the cell nonautonomous regulation of intestinal immunity (32).

Our data show that the UNC-49 GABAA receptor is also required for mitoUPR activation by the physiologically relevant model of SCA3 disease that affects all neurons, not just GABA neurons. GABA receptors and GABAergic signaling have been previously implicated in organismal proteostasis. For example, defective GABAergic signaling leads to increased aggregation of polyQ proteins in muscle cells, while GABA treatment decreased the number of polyQ aggregates (29). GABA signaling is also affected in models of Huntington’s disease (HD), which have polyQ expansions in the huntingtin (htt) protein (79). However, our observation that GABAergic redox signaling induces a vulnerability to multiple proteostasis diseases models suggests that harnessing mitoUPR activation to improve this proteostasis disease may not be straightforward, but highlights GABAA receptors as potential treatment targets.

Last, a gap remains in understanding how GABAergic signaling is transduced downstream of UNC-49 to mitochondria in the intestine. While many studies have focused on a direct “brain-gut” connection for mitoUPR activation (18, 49, 78), our results suggest that the neuromuscular junction and muscle cells are functionally important. This is consistent with a study, demonstrating that UNC-49 mediated a neuronal-muscle connection involved in intestinal immunity (32). Further research linking redox activation of UNC-49 to mitoUPR activation in proteostasis disease provides insight into how the GABAergic system can be harnessed for therapeutic intervention.

In conclusion, GABAergic redox signaling mediates cell nonautonomous activation of several stress response pathways but also induces a vulnerability to proteostasis disease in the absence of oxidative stress. The GABAA receptor UNC-49 is required for activation of the mitoUPR, and we demonstrate that UNC-49 channel activity is redox sensitive. Redox regulation of the GABAA receptor may contribute to many aspects of neuronal and organismal regulation and may be targets to alleviate disease.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains and general maintenance

All C. elegans strains were cultured and observed using standard methods (20) unless otherwise stated. C. elegans were maintained on NGM dishes seeded with Escherichia coli OP50 strain at 20°C in the dark. Strains were backcrossed to Bristol strain N2 at least five times unless otherwise stated. The GABA-KR (XE1150) and GABA-KR/GFP (XE1158) (15) strains were provided by the Hammarlund laboratory (Yale, New Haven, CT). The SCA3-related strains (AT3q14, AT3q75, and AT3q130), previously described (67), were provided by the Maciel laboratory (Universidade do Minho, ICVS, Braga, Portugal). All remaining strains were provided by the Caenorhabditis Genetic Center (CGC) of University of Minnesota (https://cgc.umn.edu/) or by the National Bioresource Project of Japan (https://shigen.nig.ac.jp/c.elegans/top.xhtml). Double and/or triple mutant strains were generated using common breeding techniques (80). A list of all strains used in this study, together with their abbreviations, genotypes, and sources, is provided in table S2.

Optogenetic photoactivation of GABAergic KillerRed

For photoactivation, all KillerRed strains and necessary controls were bleached to obtain developmentally synchronized egg populations (81). Between 30 and 60 eggs were transferred on evenly seeded NGM dishes (35 mm) in M9 and left to dry. Dried dishes were placed under the LED lights covered by ultraviolet (UV) and blue light filters (fig. S1). Light intensities were varied by changing the distance of the light source to the NGM dishes and by dimmers. Light intensities (0.1, 0.3, 1.0, and 3.0 mW/cm2) for each dish were measured before placement of NGM dishes. Light treatment occurred chronically for 72 hours. For dark conditions, dishes were wrapped in aluminum foil and placed under the same LED lights (light intensity, 1.0 to 3.0 mW/cm2). The temperature of the NGM dishes was measured routinely via Helect Infrared Thermometer, Non-Contact Digital Laser Temperature Gun. For experiments only done in the dark, dishes were stored in opaque boxes in the 20°C incubator.

Treatment with RSP extracts and NAC

RSP was extracted as previously described (37, 57–59) with minor modifications. Instead of the previously used automatic Soxhlet Soxtherm SE 416 (Gerhardt; Königswinter), a conventional Soxhlet extraction apparatus was used in this study. The RSP was initially extracted with petroleum ether, and the defatted RSP was dried overnight at room temperature. The second extraction of the defatted RSP was undertaken with an ethanol/water mixture (95:5), followed by one cycle of evaporation using the rotary evaporator Rotavapor R-114 (Büchi, New Castle, DE, USA). The final extract was frozen (24 hours) and free-dried (Edwards Freeze Dryer Modulyo) for 48 hours to yield the RSP extract (6.4% yield by weight).

Stock solutions of both RSP extract and NAC (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) were prepared in M9. For NAC, the pH was adjusted with NaOH (1 M) to the same pH as M9 (pH 6.7). One hundred sixty microliters of the NAC (125 mM) and RSP (25 mg/ml) stock solutions was added to 35-mm petri dishes, filled with 4 ml of NGM and an even lawn of E. coli OP50 bacteria, to reach final concentrations of 5 mM (NAC) and 1 mg/ml RSP extract. Synchronized eggs of hsp-6p::GFP and hsp-6p::GFP;GABA-KR worms were transferred onto these and control dishes (M9 treatment) and cultured for 72 hours in the dark.

Assessment of stress response induction using reporter strains for gst-4, sod-3, hsp-16.2, daf-16, and hsp-6

Strains were grown in NGM dishes (35 mm) seeded with an even lawn of E. coli OP50 bacteria for 72 hours (see above). Worms were prepared for fluorescence microscopy by preparing 3% agar slides and adding a drop of levamisol (3 mM) onto the agar, and about 10 worms were added per slide. If needed, worms were oriented using an eye lash. Excess levamisol was removed, and the worms were covered with a cover slide and sealed with 3% agar. Brightfield and fluorescence images of animals were acquired using an Olympus Microscope IX70 (Figs. 1 and 2) or a Leica DMi8 (Figs. 3 to 6) using the same settings for control and light or drug-treated animals in each experiment. Fluorescence intensity of each worm was measured using Fiji (ImageJ, 1.53f51) and normalized to the respective controls. Daf-16p::daf-16a/b::GFP nuclear translocation was scored as nuclear or nonnuclear for each individual. The experiments were repeated at least three times independently. For the purpose of showing the results, the same level of brightness and contrast was applied to vehicle-treated animals with no impact in the fluorescence quantification of the images.

Drug toxicity assay for GABA (fig. S4A)

The toxicity of distinct concentrations of GABA in vivo was determined in the WT N2 Bristol strain, using the food clearance assay (82). The assay was performed as previously described (82, 83) in liquid culture in 96-well plate format using concentrations from 3.125 to 400 mM GABA, dissolved in deionized water. Animals treated with 5% dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) were used as a toxic concentration control. One independent experiment, with five wells per treatment concentration, was conducted.

Motor performance in the C. elegans SCA3 strain and crosses

To generate double mutants, we crossed AT3q14 and AT3q130 animals with the GABA-KR (XE1150) strain. Animals were grown in liquid culture in 96-well format as described for the toxicity assay (see above). The motility assay was performed as previously described (37, 83), using C. elegans strains expressing WT ATXN3 (AT3q14) and mutant ATXN3 (AT3q130) proteins in their nervous system, along with N2 (WT) as control.

Paralysis assay

The paralysis assay was done as previously described (64) with small modifications. All strains were cultured at 20°C and developmentally synchronized via bleaching. Seventy-two hours after bleaching (time zero), individuals were shifted from 20° to 25°C and body movement was assessed after 12, 15, 18, 21, 24, and 36 hours. Worms were scored as paralyzed if they failed to complete full-body movement spontaneously or after being touch-provoked on the head. Between 45 and 55 worms were scored for each experiment per strain, and the percentage of individuals not paralyzed was calculated for each experiment (n = 4).

Western blots

Dishes of mixed stage, mostly adult populations, were bleached and transferred to 85-mm NGM dishes with E. coli OP50 bacteria as food source. After 72 hours, worms were washed off using M9 media. Each lysate sample was prepared from between 1 and 4 NGM dishes containing developmentally staged adult worms. Worms were collected in microcentrifuge tubes by gravitation and washed twice with more M9. Excess M9 was removed before freezing at −20°C. Worm lysis and Western blotting were done according to previous work (72) with minor modifications. Worm lysis was performed with the addition of equal amount of lysis buffer as worm pellet. Modified radioimmunoprecipitation assay buffer (50 mM tris-HCl, 150 mM NaCl, 20 mM EDTA, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate, 1% Triton X-100, and 0.1% SDS, pH 8.0) was used as lysis buffer combined with sonication using a sonic probe 2× for 7 s, on ice in between (amplitude 12), or in a sonic water bath with ice 10 × 30 s on/off 20 min total (amplitude 80). After centrifugation at 12,000g for 3 min at 4°C, the supernatant was collected, and protein concentration was determined by PierceBCA Protein assay (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). For SDS gel, samples were diluted by half with milliQ water and 5× reducing loading buffer was added. Between 15 and 20 μg of samples were then loaded onto 12% gels and separated by SDS-PAGE. Proteins were transferred to nitrocellulose membranes using Trans-Blot Turbo transfer buffer and a Trans-Blot Turbo Transfer System, and membranes were blocked in 5% bovine serum albumin (BSA) in tris-buffered saline with Tween 20 (TBST; 15.2 mM tris-HCl, 4.62 mM tris base, 150 mM NaCl, 0. 5% Tween 20) for 1 hour at room temperature. Membranes were then incubated overnight at 4°C in the appropriate primary antibodies diluted 1:1000 in 5% BSA in TBST with 0.05% sodium azide: anti-KillerRed (No. AB961; Evrogen, Moscow, Russia), anti-GFP (B-2, sc-9996, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Dallas, TX, USA), and anti–α-tubulin (DM1A, Invitrogen, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). After washing three times in TBST (~1 hour total), membranes were incubated in horseradish peroxidase–conjugated secondary antibodies: goat anti-mouse secondary antibody (115035-146, Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories Inc., West Grove, PA, USA) or goat anti-rabbit secondary antibody (111-035-144, Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories Inc., West Grove, PA, USA) for 1 hour at room temperature, which was followed by washing three times in TBST (~1 hour total). Finally, proteins were visualized using ECL (Clarity Western ECL Substrate; Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA) for image capture (ChemiDoc; Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA).

Receptor expression and electrophysiological recordings

The plasmid pBGR4 containing cDNA for UNC-49C (WBGene00006784, Sequence T21C12.1c) and plasmid pBGR9 containing cDNA for UNC-49F (WBGene00006784, Sequence T21C12.1f) were provided by B. Bamber (University of Toledo, Toledo, OH) (38, 39). The cDNAs for the UNC-49C and UNC-49F subunits [subcloned into vectors pBGR4 and pBGR9, respectively (39)] were linearized with Acc65I (NEB Labs, Ipswich, MA). The complementary RNAs (cRNAs) were generated from linearized cDNA using T3 mMessage mMachine (Ambion, Austin, TX, USA). Polyadenylation of RNA was carried out using Poly(A) Tailing Kit mMessage mMachine (Ambion, Austin, TX, USA).

The cDNAs encoding the UNC-49B isoform (WBGene00006784, Sequence T21C12.1b) subcloned into the T7 expression vector pBluescript II KS(+) were purchased from Bio Basic Inc. (Amherst, NY, USA). The cDNA was linearized with Acc65I. The cDNA for the human GABAA ρ1 (GenBank accession no. M62400; NM_002042) subunit in pGEMHE (84) was linearized with NheI (New England Biolabs, Ipswich, MA, USA). The cRNAs were synthesized from linearized cDNA using the mMessage mMachine T7 Ultra Transcription Kit (Ambion, Austin, TX, USA).

The UNC-49 and ρ1 subunits were expressed in oocytes from X. laevis (African clawed frog). Quarter ovaries were purchased from Xenoocyte (Dexter, MI, USA) and digested at 37°C with shaking at 150 rpm for 15 to 30 min in 2% (w/v) (mg/ml) collagenase A solution in ND96 (96 mM NaCl, 2 mM KCl, 1.8 mM CaCl2, 1 mM MgCl2, 5 mM Hepes; pH 7.4) with penicillin (100 U/ml) and streptomycin (100 μg/ml). Following digestion, the oocytes were rinsed in ND96 and stored in ND96 with supplements [2.5 mM Na pyruvate, penicillin (100 U/ml), streptomycin (100 μg/ml), gentamicin (50 μg/ml)] at 15°C for at least 4 hours before injections.

Oocytes were injected with 15 to 30 ng of UNC-49B cRNA, or 5 ng of UNC-49C or ρ1 cRNA per oocyte. Heteromeric UNC49C/F receptors were expressed by injecting the oocytes with a total of 10 ng of cRNA in the ratio of 1:1 (UNC-49C:UNC-49F). Following injections, the oocytes were incubated at 15°C in ND96 with supplements for 1 to 3 days before conducting electrophysiological recordings.

The electrophysiological recordings were performed using standard two-electrode voltage clamp at room temperature (85, 86). The oocytes were clamped at −60 mV. Bath and drug solutions were gravity-applied from glass syringes with glass luer slips via Teflon tubing to the recording chamber (RC-1Z, Warner Instruments, Hamden, CT). The flow rate was 8 ml/min. Solutions were switched manually using four-port bulkhead switching valve and medium pressure six-port bulkhead valves (IDEX Health and Science, Rohnert Park, CA). The current responses were amplified with an OC-725C amplifier (Warner Instruments, Hamden, CT), digitized with a Digidata 1200 series digitizer (Molecular Devices, San Jose, CA), and stored using pClamp (Molecular Devices, San Jose, CA, USA). The current responses were analyzed using Clampfit (Molecular Devices, San Jose, CA, USA) to determine the peak current amplitude.

Modulation by H2O2 was measured by initially exposing an oocyte to a low (<5% of saturating GABA) concentration of GABA for up to 2 min. This was followed by an application of GABA + H2O2 for 1 to 3 min, a wash in GABA for up to 2 min, and eventual recovery in ND96. Each cell was additionally exposed to a reference solution of a saturating concentration (10 mM) of GABA. Direct activation by H2O2 was tested by exposing the oocytes to 30 to 1000 μM H2O2. Each cell was also tested with 1 mM GABA to verify expression. Lack of effect on other targets in the oocyte membrane was verified by exposing uninjected oocytes to 300 μM H2O2 or 10 mM GABA. For comparison to a previous report (34), H2O2-mediated modulation of GABA-activated receptors was confirmed in oocytes expressing the human ρ1 GABAA receptor.

The inorganic salts used in ND96, GABA, and H2O2 were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). The stock solution of GABA was made in ND96 at 500 mM and stored in aliquots at −20°C. H2O2 solution (30%, w/w) in H2O was stored at 4°C. Dilutions were made as needed on the day of experiments.

Design of unc-49 transgenes

unc-49 clones were created by assembling an unc-49B form in two parts. The common NT-terminal region (about half of the coding sequence) was created by designing a synthetic DNA fragment containing unc-49 cDNA sequences with a hemagglutinin tag inserted between the sixth and seventh amino acid after the signal peptide sequence cleavage site and three ribosomal introns positioned at sites of native unc-49 gene introns. The ribosomal introns were used in place of native sequences because of the concern that enhancer regions could reside in these large introns. The key aim was to assess whether muscle-specific expression of these forms was functional. The C-terminal region of the B form was synthesized with synonymous mutations that removed SapI sites.

Molecular biology

Plasmids (table S3) were constructed using Golden Gate assembly as detailed in (87). Oligonucleotides (table S4) were obtained from MilliporeSigma (Burlington, MA), and synthetic DNA fragments were purchased from Twist Biosciences (South San Francisco, CA). The structure of plasmids and transgenic insertions was confirmed using nanopore sequencing (plasmidsaurus, Eugene, OR).

Plasmid constructions (table S3)

NMp4865 pHygRR2 myo-3p unc-49B

The myo-3p from NMp4104, the unc-49 NT and unc-49B CT from synthetic DNAs NMp4854 and NMp4855, and the tbb-2 3′ untranslated region (UTR) from NMp3694 were coassembled into NMp4561 using a SapI Golden Gate assembly reaction.

NMp4866 pHygO2 myo-3p unc-49B sl2 scarlet

The myo-3p from NMp4104, the unc-49NT and unc-49B CT from synthetic DNAs NMp4854 and NMp4855, the gpd-2/-3 intergenic region from NMp4002, mScarlet from NMp4443, and the tbb-2 3′UTR from NMp3777 were coassembled into NMp4558 using a SapI Golden Gate assembly reaction.

Strain constructions (table S2)

jsSi1726 (NM5548) and jsSi1901 (NM6007) landing sites were introduced into JHM051 by crossing landing site males into JHM051 and backcrossing the male progeny to JHM051 and then re-homozygosing for the landing site, resulting in strains NM6388 and NM6402.

rRMCE transgenes

Plasmids were injected both into a background containing only a landing site and in a landing site; unc-49; unc-25p:killer red, hsp-6p::GFP background. Plasmid DNAs were injected at ~30 to 50 ng/μl. The pHygRR2-based plasmid was injected into NM5548 and NM6388, and the pHygO2-based plasmid was injected into NM6007 and NM6402 animals as described by Nonet (87). Animals were injected and cultured at 25°C. On day 3, 100 μl of hygromycin B (20 mg/ml) was added to select for insertions, and homozygous insertion-bearing animals were isolated on day 8 or day 9 after injection. Insertions were obtained for three of four conditions (three of four injections). The plasmid insertion not obtained in the mutant background was backcrossed into that background (see tables S2 and S5 for information). The insertion structure of both transgenes was confirmed by nanopore sequencing of DNA amplified from genomic DNA as described by Nonet (88).

Statistics

Statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism 9 [version 9.3.1 (471)]. Continuous variables were tested for normal distribution (Shapiro-Wilk or Kolmogorov-Smirnov normality test) and outliers; they were then analyzed with t test, one-way or two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), using Bonferroni’s, Dunnett’s, or Tukey’s multiple comparison analysis for post hoc comparison. A critical value for significance of P ≤ 0.05 was applied throughout the study. All experiments were performed at least in triplicate (n ≥ 3), and data show mean ± SD or mean ± SEM unless otherwise stated. Categorical variables were analyzed using the Fisher’s exact test. In all graphs, asterisks (*) are used to indicate statistical significance, with ns meaning not significant (P > 0.05), *P ≤ 0.05, **P ≤ 0.01, and ***P ≤ 0.001.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge Macintosh of Glendaveny for providing the rapeseed pomace samples for this study. We thank the Caenorhabditis Genetics Center (CGC; https://cgc.umn.edu/), which is funded by the National Institutes of Health—Office of Research Infrastructure Programs (P40 OD010440) and the National Bioresource Project (https://shigen.nig.ac.jp/c.elegans; material transfer agreement signed), for mutant nematode strains and the Maciel laboratory [Life and Health Sciences Research Institute (ICVS), School of Medicine, University of Minho, Braga, Portugal and 3ICVS/3B’s—PT Government Associate Laboratory, Braga, Portugal] for the three ataxia nematode strains. The KillerRed strains were provided by the Hammarlund laboratory (Yale, New Haven, CT). We also thank B. Bamber (University of Toledo, Toledo, OH), who provided plasmid pBGR4 containing cDNA for UNC-49C and plasmid pBGR9 containing cDNA for UNC-49F.

Funding: This publication was supported by the National Institute on Aging Awards R21 AG058037 and R21AG058037-02S1 (to K.K. and J.M.H.) and a postdoctoral fellowship from the National Ataxia Foundation (to F.P.). This work was also supported by NIH National Institute of General Medical Sciences (grant R35GM140947) and funds from the Taylor Family Institute for Innovative Psychiatric Research (to G.A.), as well as by NIH grants R56 AG072169 and RO1 AG057748 (to K.K.) by the National Institute on Aging. Grant R01GM141688 by the National Institute of General Medical Sciences supported M.L.N.

Author contributions: F.P., G.A., M.L.N., K.K., and J.M.H. conceptualized and designed the experiments. F.P., J.M., M.L.N., and S.H. performed C. elegans experiments with supervision by M.L.N., K.K., and J.M.H. A.L.G. performed electrophysiology experiments under supervision by G.A. B.B. prepared the RSP extract with supervision by P.K.T.L. and K.Y. F.P., A.L.G., G.A., and J.M.H. analyzed data. F.P., A.L.G., and J.M.H. wrote the original manuscript draft with review and editing performed by all the other authors.

Competing interests: The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Data and materials availability: All data needed to evaluate the conclusions in the paper are present in the paper and/or the Supplementary Materials. Most strains and plasmids can be requested from the corresponding author or the Caenorhabditis Genetics Center (CGC; https://cgc.umn.edu/) without restrictions. The tm5487 strain can be provided by the National Bioresource Project (https://shigen.nig.ac.jp/c.elegans/) pending scientific review and a completed material transfer agreement.

Supplementary Materials

This PDF file includes:

Figs. S1 to S6

Tables S1 and S2

Legends for tables S3 to S5

References

Other Supplementary Material for this manuscript includes the following:

Tables S3 to S5

REFERENCES AND NOTES

- 1.M. Schieber, N. S. Chandel, ROS function in redox signaling and oxidative stress. Curr. Biol. 24, R453–R462 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.A. Miranda-Vizuete, E. A. Veal, Caenorhabditis elegans as a model for understanding ROS function in physiology and disease. Redox Biol. 11, 708–714 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Y. Yang, S. M. Han, M. A. Miller, MSP hormonal control of the oocyte MAP kinase cascade and reactive oxygen species signaling. Dev. Biol. 342, 96–107 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.W. A. Edens, L. Sharling, G. Cheng, R. Shapira, J. M. Kinkade, T. Lee, H. A. Edens, X. Tang, C. Sullards, D. B. Flaherty, G. M. Benian, J. David Lambeth, Tyrosine cross-linking of extracellular matrix is catalyzed by Duox, a multidomain oxidase/peroxidase with homology to the phagocyte oxidase subunit gp91phox. J. Cell Biol. 154, 879–892 (2001). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.G. Li, J. Gong, H. Lei, J. Liu, X. Z. S. Xu, Promotion of behavior and neuronal function by reactive oxygen species in C. elegans. Nat. Commun. 7, 13234 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.D. Bazopoulou, D. Knoefler, Y. Zheng, K. Ulrich, B. J. Oleson, L. Xie, M. Kim, A. Kaufmann, Y.-T. Lee, Y. Dou, Y. Chen, S. Quan, U. Jakob, Developmental ROS individualizes organismal stress resistance and lifespan. Nature 576, 301–305 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.P. Back, W. H. de Vos, G. G. Depuydt, F. Matthijssens, J. R. Vanfleteren, B. P. Braeckman, Exploring real-time in vivo redox biology of developing and aging Caenorhabditis elegans. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 52, 850–859 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.J. Durieux, S. Wolff, A. Dillin, The cell-non-autonomous nature of electron transport chain-mediated longevity. Cell 144, 79–91 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.D. J. Dues, C. E. Schaar, B. K. Johnson, M. J. Bowman, M. E. Winn, M. M. Senchuk, J. M. van Raamsdonk, Uncoupling of oxidative stress resistance and lifespan in long-lived isp-1 mitochondrial mutants in Caenorhabditis elegans. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 108, 362–373 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.C. E. Schaar, D. J. Dues, K. K. Spielbauer, E. Machiela, J. F. Cooper, M. Senchuk, S. Hekimi, J. M. van Raamsdonk, Mitochondrial and cytoplasmic ROS have opposing effects on lifespan. PLOS Genet. 11, 1–24 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.J. M. van Raamsdonk, S. Hekimi, Reactive oxygen species and aging inCaenorhabditis elegans: Causal or casual relationship? Antioxid. Redox Signal. 13, 1911–1953 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.M. Waghray, Z. Cui, J. C. Horowitz, I. M. Subramanian, F. J. Martinez, G. B. Toews, V. J. Thannickal, Hydrogen peroxide is a diffusible paracrine signal for the induction of epithelial cell death by activated myofibroblasts. FASEB J. 19, 1–16 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.A. P. Wojtovich, T. H. Foster, Optogenetic control of ROS production. Redox Biol. 2, 368–376 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.K. Takemoto, T. Matsuda, N. Sakai, D. Fu, M. Noda, S. Uchiyama, I. Kotera, Y. Arai, M. Horiuchi, K. Fukui, T. Ayabe, F. Inagaki, H. Suzuki, T. Nagai, SuperNova, a monomeric photosensitizing fluorescent protein for chromophore-assisted light inactivation. Sci. Rep. 3, 2629 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.D. C. Williams, R. El Bejjani, P. M. Ramirez, S. Coakley, S. A. Kim, H. Lee, Q. Wen, A. Samuel, H. Lu, M. A. Hilliard, M. Hammarlund, Rapid and permanent neuronal inactivation in vivo via subcellular generation of reactive oxygen with the use of KillerRed. Cell Rep. 5, 553–563 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.J. Kobayashi, H. Shidara, Y. Morisawa, M. Kawakami, Y. Tanahashi, K. Hotta, K. Oka, A method for selective ablation of neurons in C. elegans using the phototoxic fluorescent protein, KillerRed. Neurosci. Lett. 548, 261–264 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.A. P. Wojtovich, A. Y. Wei, T. A. Sherman, T. H. Foster, K. Nehrke, Chromophore-assisted light inactivation of mitochondrial electron transport chain complex II in Caenorhabditis elegans. Sci. Rep. 6, 1–13 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.L.-W. Shao, R. Niu, Y. Liu, Neuropeptide signals cell non-autonomous mitochondrial unfolded protein response. Cell Res. 26, 1182–1196 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.E. Yemini, T. Jucikas, L. J. Grundy, A. E. X. Brown, W. R. Schafer, A database of Caenorhabditis elegans behavioral phenotypes. Nat. Method. 10, 877–879 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.S. Brenner, The genetics of Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics 77, 71–94 (1974). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.V. Adam-Vizi, Production of reactive oxygen species in brain mitochondria: Contribution by electron transport chain and non–electron transport chain sources. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 7, 1140–1149 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.M. E. Pamenter, Mitochondria: A multimodal hub of hypoxia tolerance. Can. J. Zool. 92, 569–589 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- 23.M. V. Accardi, B. A. Daniels, P. M. G. E. Brown, J.-M. Fritschy, S. K. Tyagarajan, D. Bowie, Mitochondrial reactive oxygen species regulate the strength of inhibitory GABA-mediated synaptic transmission. Nat. Commun. 5, 3168 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.J. N. Cobley, M. L. Fiorello, D. M. Bailey, 13 reasons why the brain is susceptible to oxidative stress. Redox Biol. 15, 490–503 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.S. M. Kilbride, J. E. Telford, G. P. Davey, Age-related changes in H2O2 production and bioenergetics in rat brain synaptosomes. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1777, 783–788 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.M. E. Rice, H2O2: A dynamic neuromodulator. Neuroscientist 17, 389–406 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.C. A. Massaad, E. Klann, Reactive oxygen species in the regulation of synaptic plasticity and memory. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 14, 2013–2054 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.J. W. Błaszczyk, Parkinson’s disease and neurodegeneration: GABA-collapse hypothesis. Front. Neurosci. 10, 269 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.S. M. Garcia, M. O. Casanueva, M. C. Silva, M. D. Amara, R. I. Morimoto, Neuronal signaling modulates protein homeostasis in Caenorhabditis elegans post-synaptic muscle cells. Genes Dev. 21, 3006–3016 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.R. C. Taylor, K. M. Berendzen, A. Dillin, Systemic stress signalling: Understanding the cell non-autonomous control of proteostasis. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 15, 211–217 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.F. Yuan, J. Zhou, L. Xu, W. Jia, L. Chun, X. Z. S. Xu, J. Liu, GABA receptors differentially regulate life span and health span in C. elegans through distinct downstream mechanisms. Phys. Ther. 317, C953–C963 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Z. Zheng, X. Zhang, J. Liu, P. He, S. Zhang, Y. Zhang, J. Gao, S. Yang, N. Kang, M. I. Afridi, S. Gao, C. Chen, H. Tu, GABAergic synapses suppress intestinal innate immunity via insulin signaling in Caenorhabditis elegans. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 118, e2021063118 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.A. N. Beltrán González, M. I. López Pazos, D. J. Calvo, Reactive oxygen species in the regulation of the GABA mediated inhibitory neurotransmission. Neuroscience 439, 137–145 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.A. N. Beltrán González, J. Gasulla, D. J. Calvo, An intracellular redox sensor for reactive oxygen species at theM3-M4 linker ofGABAAρ1receptors. Br. J. Pharmacol. 171, 2291–2299 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.A. Amato, C. N. Connolly, S. J. Moss, T. G. Smart, Modulation of neuronal and recombinant GABAA receptors by redox reagents. J. Physiol. 517, 35–50 (1999). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Y. Fardghassemi, A. Tauffenberger, S. Gosselin, J. A. Parker, Rescue of ATXN3 neuronal toxicity in Caenorhabditis elegans by chemical modification of endoplasmic reticulum stress. Dis. Model. Mech. 10, 1465–1480 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.F. Pohl, A. Teixeira-Castro, M. D. Costa, V. Lindsay, J. Fiúza-Fernandes, M. Goua, G. Bermano, W. Russell, P. Maciel, P. K. T. Lin, P. Kong, T. Lin, V. Lindsay, GST-4-dependent suppression of neurodegeneration in C . elegans models of Parkinson’s and Machado-Joseph disease by rapeseed pomace extract supplementation. Front. Neurosci. 13, 1–13 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.B. A. Bamber, R. E. Twyman, E. M. Jorgensen, Pharmacological characterization of the homomeric and heteromeric UNC-49 GABA receptors in C. elegans. Br. J. Pharmacol. 138, 883–893 (2003). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.B. A. Bamber, A. A. Beg, R. E. Twyman, E. M. Jorgensen, The Caenorhabditis elegans unc-49 locus encodes multiple subunits of a heteromultimeric GABA receptor. J. Neurosci. 19, 5348–5359 (1999). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.H. Hutter, J. Suh, GExplore 1.4: An expanded web interface for queries on Caenorhabditis elegans protein and gene function. Worm 5, e1234659 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.M. B. Goodman, P. Sengupta, How Caenorhabditis elegans senses mechanical stress, temperature, and other physical stimuli. Genetics 212, 25–51 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.S. L. Rea, D. Wu, J. R. Cypser, J. W. Vaupel, T. E. Johnson, A stress-sensitive reporter predicts longevity in isogenic populations of Caenorhabditis elegans. Nat. Genet. 37, 894–898 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.R. P. Brandes, F. Rezende, K. Schröder, Redox regulation beyond ROS why ROS should not be measured as often. Circ. Res. 123, 326–328 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Y. M. Go, J. J. Gipp, R. T. Mulcahy, D. P. Jones, H2O2-dependent activation of GCLC-ARE4 reporter occurs by mitogen-activated protein kinase pathways without oxidation of cellular glutathione or thioredoxin-1. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 5837–5845 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.S. T. Henderson, T. E. Johnson, daf-16 integrates developmental and environmental inputs to mediate aging in the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans. Curr. Biol. 11, 1975–1980 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.X. X. Lin, I. Sen, G. E. Janssens, X. Zhou, B. R. Fonslow, D. Edgar, N. Stroustrup, P. Swoboda, J. R. Yates, G. Ruvkun, C. G. Riedel, DAF-16/FOXO and HLH-30/TFEB function as combinatorial transcription factors to promote stress resistance and longevity. Nat. Commun 9, 1–15 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.J. M. van Raamsdonk, S. Hekimi, Deletion of the mitochondrial superoxide dismutase sod-2 extends lifespan in Caenorhabditis elegans. PLOS Genet. 5, e1000361 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.B. Leiers, A. Kampkötter, C. G. Grevelding, C. D. Link, T. E. Johnson, K. Henkle-Dührsen, A stress-responsive glutathione S-transferase confers resistance to oxidative stress in Caenorhabditis elegans. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 34, 1405–1415 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.K. M. Berendzen, J. Durieux, L.-W. Shao, Y. Tian, H.-E. Kim, S. Wolff, Y. Liu, A. Dillin, Neuroendocrine coordination of mitochondrial stress signaling and proteostasis. Cell 166, 1553–1563.e10 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.F. Muñoz-Carvajal, M. Sanhueza, The mitochondrial unfolded protein response: A hinge between healthy and pathological aging. Front. Aging Neurosci. 12, 300 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.D. Ganini, F. Leinisch, A. Kumar, J. J. Jiang, E. J. Tokar, C. C. Malone, R. M. Petrovich, R. P. Mason, Fluorescent proteins such as eGFP lead to catalytic oxidative stress in cells. Redox Biol. 12, 462–468 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.D. J. Kemble, G. Sun, Direct and specific inactivation of protein tyrosine kinases in the Src and FGFR families by reversible cysteine oxidation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 106, 5070–5075 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Y. Liu, B. S. Samuel, P. C. Breen, G. Ruvkun, Caenorhabditis elegans pathways that surveil and defend mitochondria. Nature 508, 406–410 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.S. Bora, G. S. H. Vardhan, N. Deka, L. Khataniar, D. Gogoi, A. Baruah, Paraquat exposure over generation affects lifespan and reproduction through mitochondrial disruption in C. elegans. Toxicology 447, 152632 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.C. M. Haynes, K. Petrova, C. Benedetti, Y. Yang, D. Ron, ClpP mediates activation of a mitochondrial unfolded protein response in C. elegans. Dev. Cell 13, 467–480 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.G. K. Schwalfenberg, N-acetylcysteine: A review of clinical usefulness (an old drug with new tricks). J. Nutr. Metab. 2021, 1–13 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.F. Pohl, M. Goua, G. Bermano, W. R. Russell, L. Scobbie, P. Maciel, P. Kong Thoo Lin, Revalorisation of rapeseed pomace extracts: An in vitro study into its anti-oxidant and DNA protective properties. Food Chem. 239, 323–332 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.K. Yates, F. Pohl, M. Busch, A. Mozer, L. Watters, A. Shiryaev, P. Kong Thoo Lin, Determination of sinapine in rapeseed pomace extract: Its antioxidant and acetylcholinesterase inhibition properties. Food Chem. 276, 768–775 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.F. Pohl, M. Goua, K. Yates, G. Bermano, W. R. Russell, P. Maciel, P. K. T. Lin, Impact of rapeseed pomace extract on markers of oxidative stress and DNA damage in human SH-SY5Y cells. J. Food Biochem. 45, e13592 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.S. L. McIntire, R. J. Reimer, K. Schuske, R. H. Edwards, E. M. Jorgensen, Identification and characterization of the vesicular GABA transporter. Nature 389, 870–876 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.S. Pletnev, N. G. Gurskaya, N. Pletneva, K. A. Lukyanov, D. M. Chudakov, V. I. Martynov, V. O. Popov, M. Kovalchuk, A. Wlodawer, Z. Dauter, V. Pletnev, Structural basis for phototoxicity of the genetically encoded photosensitizer KillerRed. J. Biol. Chem. 284, 32028–32039 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.WormBase WS283 March, WormBase (2022), (available at https://wormbase.org).

- 63.H. S. Yi, J. Y. Chang, M. Shong, The mitochondrial unfolded protein response and mitohormesis: A perspective on metabolic diseases. J. Mol. Endocrinol. 61, R91 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]