Abstract

Organisms that overproduced l-cysteine and l-cystine from glucose were constructed by using Escherichia coli K-12 strains. cysE genes coding for altered serine acetyltransferase, which was genetically desensitized to feedback inhibition by l-cysteine, were constructed by replacing the methionine residue at position 256 of the serine acetyltransferase protein with 19 other amino acid residues or the termination codon to truncate the carboxy terminus from amino acid residues 256 to 273 through site-directed mutagenesis by using PCR. A cysteine auxotroph, strain JM39, was transformed with plasmids having these altered cysE genes. The serine acetyltransferase activities of most of the transformants, which were selected based on restored cysteine requirements and ampicillin resistance, were less sensitive than the serine acetyltransferase activity of the wild type to feedback inhibition by l-cysteine. At the same time, these transformants produced approximately 200 mg of l-cysteine plus l-cystine per liter, whereas these amino acids were not detected in the recombinant strain carrying the wild-type serine acetyltransferase gene. However, the production of l-cysteine and l-cystine by the transformants was very unstable, presumably due to a cysteine-degrading enzyme of the host, such as cysteine desulfhydrase. Therefore, mutants that did not utilize cysteine were derived from host strain JM39 by mutagenesis with N-methyl-N′-nitro-N-nitrosoguanidine. When a newly derived host was transformed with plasmids having the altered cysE genes, we found that the production of l-cysteine plus l-cystine was markedly increased compared to production in JM39.

l-Cysteine, one of the important amino acids used in the pharmaceutical, food, and cosmetics industries, has been obtained by extracting it from acid hydrolysates of the keratinous proteins in human hair and feathers. The first successful microbial process used for industrial production of l-cysteine involved the asymmetric conversion of dl-2-aminothiazoline-4-carboxylic acid, an intermediate compound in the chemical synthesis of dl-cysteine, to l-cysteine by enzymes from a newly isolated bacterium, Pseudomonas thiazoliniphilum (11). Yamada and Kumagai (13) also described enzymatic synthesis of l-cysteine from beta-chloroalanine and sodium sulfide in which Enterobacter cloacae cysteine desulfhydrase (CD) was used. However, high level production of l-cysteine from glucose with microorganisms has not been studied.

Biosynthesis of l-cysteine in wild-type strains of Escherichia coli and Salmonella typhimurium is regulated through feedback inhibition by l-cysteine of serine acetyltransferase (SAT), a key enzyme in l-cysteine biosynthesis, and repression of expression of a series of enzymes used for sulfide reduction from sulfate by l-cysteine (4), as shown in Fig. 1. Denk and Böck reported that a small amount of l-cysteine was excreted by a revertant of a cysteine auxotroph of E. coli. In this revertant, SAT encoded by the cysE gene was desensitized to feedback inhibition by l-cysteine, and the methionine residue at position 256 in SAT was replaced by isoleucine (2). These results indicate that it may be possible to construct organisms that produce high levels of l-cysteine by amplifying an altered cysE gene. Although the residue at position 256 is supposedly part of the allosteric site for cysteine binding, no attention has been given to the effect of an amino acid substitution at position 256 in SAT on feedback inhibition by l-cysteine and production of l-cysteine. It is also not known whether isoleucine is the best residue for desensitization to feedback inhibition.

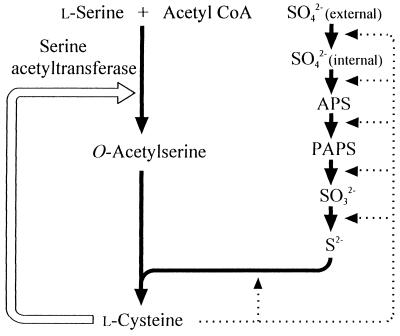

FIG. 1.

Biosynthesis and regulation of l-cysteine in E. coli. Abbreviations: APS, adenosine 5′-phosphosulfate; PAPS, phosphoadenosine 5′-phosphosulfate; Acetyl CoA, acetyl coenzyme A. The open arrow indicates feedback inhibition, and the dotted arrows indicate repression.

On the other hand, l-cysteine appears to be degraded by E. coli cells. Therefore, in order to obtain l-cysteine producers, a host strain with a lower level of l-cysteine degradation activity must be isolated. In this paper we describe high-level production of l-cysteine plus l-cystine from glucose by E. coli resulting from construction of altered cysE genes. The methionine residue at position 256 in SAT was replaced by other amino acids or the termination codon in order to truncate the carboxy terminus from amino acid residues 256 to 273 by site-directed mutagenesis. A newly derived cysteine-nondegrading E. coli strain with plasmids having the altered cysE genes was used to investigate production of l-cysteine plus l-cystine.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Organisms and plasmid.

The microorganisms used in this study were E. coli JM39 (F+ cysE51 tfr-8) (2), JM240 (Hfr proC47 cys-54 supE42) (2), and JM109 [recA1 Δ(lac-proAB) endA1 gyrA96 thi-1 hsdR17 relA1 supE44/(F′ traD36 proAB+ lacIq ZΔM15)]. Strain JM39 was used as the host for transformations of plasmids having altered cysE genes and also as the parent for deriving l-cysteine-nondegrading mutants. Chromosomal DNA from JM240 was used as the template for construction of altered cysE genes. JM109 was used as the indicator strain in the test for growth inhibition by l-cysteine. The plasmid vector pBluescript II SK+ (Toyobo Biochemicals, Osaka, Japan) carrying the ampicillin resistance gene was used for cloning and expression of the cysE gene.

Enzymes used for DNA manipulations.

The enzymes used for DNA manipulations were obtained from Takara Shuzo (Kyoto, Japan) and were used under the conditions recommended by the supplier.

Chemicals.

All amino acids were obtained from Ajinomoto Co., Inc. (Tokyo, Japan), and acetyl coenzyme A was purchased from Wako Pure Chemical Industries Ltd. (Tokyo, Japan). N-Methyl-N′-nitro-N-nitrosoguanidine (NTG) was obtained from Sigma Chemical Co. (St. Louis, Mo.).

Gene cloning.

Figure 2 shows the strategy used to clone the cysE gene. To isolate the wild-type gene containing the putative promoter and terminator regions by PCR, genomic DNA was prepared from E. coli JM240, and sense and the antisense primers were designed based on the nucleotide sequences outside the gene, as determined by Denk and Böck (2). The sense primer was 5′-GGGAATTCATCGCTTCGGCGTTGAAA-3′, and the antisense primer was 5′-GGCTCTAGAAGCGGTATTGAGAGAGATTA-3′. A 10- to 50-ng portion of genomic DNA was added as a template to a solution containing 10 μl of 10× PCR buffer (100 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8.3], 500 mM KCl, 15 mM MgCl2), 8 μl of a deoxyribonucleoside triphosphate preparation containing each deoxynucleoside triphosphate at a concentration of 2.5 mM, 1 μl of a preparation containing each of the two primers at a concentration of 1 μM, 2.5 U of Ex Taq DNA polymerase, and enough distilled water to bring the total volume to 100 μl. Twenty-five PCR cycles (94°C for 1 min, 55°C for 1 min, 72°C for 3 min) were carried out with a model 480 DNA thermal cycler (Perkin-Elmer Co., Foster City, Calif.). The unique amplified band at about 1,200 bp was ligated to the EcoRV site of pBluescriptII SK+ by a TA cloning method (7). The vector was digested with EcoRV and incubated with Taq DNA polymerase by using standard buffer conditions in the presence of 2 mM dTTP for 2 h at 70°C. The vector added a single thymidine at the 3′ end, and the PCR products added to the 3′ adenosine overhang by the Taq DNA polymerase during the PCR had complementary single-base 3′ overhangs added by the ligation reaction. The nucleotide sequence of the insert containing the cysE gene was confirmed with a model 373A DNA sequencer (Applied Biosystems) by using dideoxy chain termination sequencing. A plasmid harboring the wild-type cysE gene, designated pCE, was used as the template DNA for site-directed mutagenesis.

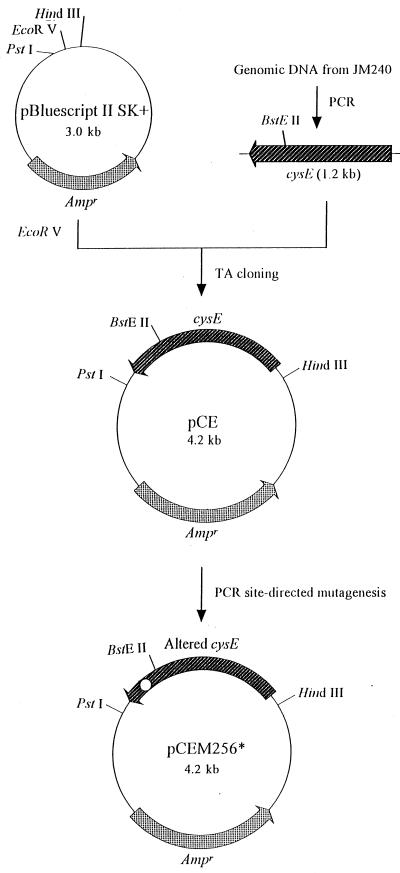

FIG. 2.

Cloning and site-directed mutagenesis of cysE. Details are described in the text. Ampr, ampicillin resistance gene. The open circle indicates the codon for residue 256 in SAT altered by site-directed mutagenesis.

Site-directed mutagenesis.

As shown in Fig. 2, the residue at position 256 in SAT was replaced by various amino acid residues by PCR performed with 5′-phosphorylated primers 5′-CAGGAAACAGCTATGAC-3′ (primer a), 5′-CTGCAATCTGTGACGCT-3′ (primer b), 5′-AATGGATXXXGACCAGC-3′ (primer c), and 5′-GCTGGTCXXXATCCATT-3′ (primer d) (X indicates a mixture of G, A, T, and C). Primers a and b were synthesized to complement the regions 140 bp upstream of the PstI restriction site and 50 bp downstream of the BstEII site in pCE, respectively. Primers c and d were used as primers for mutagenesis. A PCR was first carried out with primers a and c or primers b and d in an independent microtube. The unique amplified bands at 270 and 250 bp obtained with primers a and c and primers b and d, respectively, were purified from agarose gels after electrophoresis and then used as templates in a subsequent PCR with primers a and b, as in the corresponding reactions of the first PCR. After the second PCR, the expected PCR product band was digested with PstI and BstEII to recover the 310-bp fragments and then ligated to the large pCE fragment digested with PstI and BstEII. DNA sequencing was carried out in order to identify the amino acid substitution. The resulting plasmids having altered cysE genes were designated pCEM256* (the asterisk indicates an amino acid residue identified by its single-letter abbreviation). To truncate the carboxy terminus from amino acid residue 256 of the SAT protein, the amber (UAG) termination codon at position 256 was introduced by PCR with primers a, b, 5′-AATGGATTAGGACCAGC-3′, and 5′-GCTGGTCCTAATCCATT-3′ (the underlining indicates the locations of mismatches).

Media and cultivation.

Luria-Bertani (LB) medium (10) was the complex medium used, and M9 medium (10) was the minimal medium used for all strains. C1 medium was used for the production of l-cysteine and l-cystine and contained (per liter of distilled water) 30 g of glucose, 2 g of KH2PO4, 10 g of (NH4)2SO4, 1 g of MgSO4 · 7H2O, 10 mg of FeSO4 · 7H2O, 10 mg of MnCl2 · 4H2O, 20 g of CaCO3 (added after it was sterilized separately), and 100 mg each of l-isoleucine, l-leucine, l-methionine, and glycine. The pH was adjusted to 7.0 with KOH. When appropriate, ampicillin (50 μg/ml) was added to the medium. For production of amino acids, a loopful of cells cultured for 24 h on LB solid medium containing ampicillin at 30°C was inoculated into 20 ml of C1 medium in a 500-ml flask, and the preparation was incubated at 30°C for 72 h on a reciprocal shaker at 120 strokes per min.

Isolation of mutants that do not utilize l-cysteine.

E. coli JM39 cells in the late exponential phase in LB medium were mutagenized for 10 min with NTG (100 μg/ml in 0.1 M phosphate buffer [pH 7.0]). Mutagenized cells were spread onto LB agar plates and incubated at 37°C for 24 h. The colonies were replica plated onto modified M9 medium plates (containing 0.3 mg of l-cysteine per ml as the sole nitrogen source instead of 1.0 mg of NH4Cl per ml) and M9 medium plates and incubated at 37°C for 48 h. Colonies which failed to grow on the former plates but grew on the latter plates were selected as possible mutants.

Determination of l-cysteine and l-cystine.

The amounts of l-cysteine and l-cystine were determined by performing a microbioassay with Pediococcus acidilactici (formerly Leuconostoc mesenteroides) IFO 3076 (12). We confirmed that this strain responded equally to l-cysteine and l-cystine. As l-cysteine in the culture fluid was easily oxidized to l-cystine, which was slightly soluble in water, the culture fluids were assayed after l-cystine was dissolved with 0.5 N HCl.

Enzyme assays.

To determine SAT (EC 2.3.1.30) activities, cells were grown in 20 ml of C1 medium at 30°C for 48 h to the late exponential phase, washed with 50 mM Tris-HCl buffer (pH 7.5), and resuspended in 4 ml of the same buffer containing 2 mM dithiothreitol. The supernatants obtained after disruption of the cells by ultrasonication and centrifugation at 30,000 × g for 30 min were used as enzyme sources. SAT activity was assayed by monitoring the decrease in absorbance at 232 nm of the reaction mixture (final volume, 1 ml) containing 50 μmol of Tris-HCl (pH 7.6), 1 μmol of l-serine, 0.1 μmol of acetyl coenzyme A, and enzyme solution at 30°C, as described by Denk and Böck (2). To determine CD (EC 4.4.1.1) activities, cells were grown in 25 ml of LB medium supplemented with 1 mg of l-cysteine per ml at 30°C for 24 h, washed with 50 mM Tris-HCl buffer (pH 7.5), and resuspended in 5 ml of the same buffer containing 2 mM dithiothreitol and 50% (vol/vol) glycerol. The supernatants obtained after disruption of the cells by ultrasonication and centrifugation at 30,000 × g for 30 min were used as enzyme sources. CD activity was measured as described by Kredich et al. (5). Protein concentrations were determined with a Bio-Rad Protein Assay kit. Bovine serum albumin was used as the standard protein.

RESULTS

Growth inhibition by l-cysteine and reversal of this inhibition by amino acids.

Harris found that growth of an E. coli K-12 strain was inhibited by l-cysteine and that this inhibition was partially reversed by adding l-leucine and l-isoleucine (3). Similar results were obtained in this study with strain JM109. Furthermore, we found that adding glycine, l-methionine, and l-tyrosine also effectively reversed the growth inhibition caused by l-cysteine (data not shown). Based on these results, each of these amino acids (except l-tyrosine, which was slightly soluble in water) was added to C1 medium at a concentration of 100 μg/ml in the cultures used for production of amino acids.

Effect of amino acid substitution at position 256 in SAT on catalytic properties and l-cysteine production.

The UAG termination codon at position 256 in SAT was first introduced by site-directed mutagenesis. Surprisingly, the cells carrying the mutated gene complemented the cysteine auxotrophy of strain JM39. This suggested that the truncated protein still had SAT activity. To replace Met-256 with other amino acids, 19 mutant plasmids were constructed by site-directed mutagenesis, as described above. A cysteine auxotroph, strain JM39, was transformed with these plasmids, and the transformants exhibited ampicillin resistance and complemented the cysteine auxotrophy of JM39. In the case of leucine and lysine substitutions, transformants were not obtained, probably because the specific activity was severely impaired.

Table 1 shows the relative SAT activities of strains having various proteins mutated at position 256. The enzymes in the soluble fraction obtained from sonicated cells were assayed without further purification. The level of gene expression seemed to be almost the same for all mutants, judging from densitometric estimates of the amounts of accumulated SAT in the soluble fraction obtained by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (data not shown). The SAT activity of the strain carrying pCE was 140-fold higher than the SAT activity of JM109 harboring the vector used (0.03 U/min/mg) due to the gene dosage effect. However, significant decreases in enzymatic activity occurred when residue 256 was replaced by other amino acids or the termination codon. On the other hand, the levels of activity of the mutant enzymes were approximately 15 to 30% even in the presence of 100 μM l-cysteine, while the wild-type enzyme was markedly inhibited by l-cysteine. These results indicate that the methionine at position 256 is, in part, responsible for the catalytic efficiency observed, as well as the feedback inhibition due to l-cysteine.

TABLE 1.

Effects of amino acid residue substitutions at position 256 in SAT on catalytic properties and production of l-cysteine plus l-cystine

| Plasmid | Amino acid residue at position 256 | SAT activity (U/min/mg) in the presence ofa:

|

Activity remaining in the presence of 100 μM l-cysteine (%) | Concn of l-cysteine plus l-cystine (mg/liter) with the following hosts:

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No l-cysteine | 100 μM l-cysteine | JM39 | JM39-8 | |||

| pCE | Met (wild type) | 4.31 | 0.020 | 0.5 | NDb | 70 ± 10 |

| pCEM256A | Ala | 0.54 | 0.130 | 24.1 | 140 ± 80 | 790 ± 380 |

| pCEM256R | Arg | 0.40 | 0.128 | 32.1 | 200 ± 160 | 600 ± 80 |

| pCEM256N | Asn | 0.26 | 0.072 | 27.6 | 190 ± 110 | 530 ± 50 |

| pCEM256D | Asp | 0.12 | 0.029 | 24.2 | 300 ± 140 | 580 ± 50 |

| pCEM256C | Cys | 0.17 | 0.053 | 31.4 | 50 ± 20 | 360 ± 20 |

| pCEM256Q | Gln | 0.10 | 0.028 | 28.1 | 130 ± 100 | 520 ± 90 |

| pCEM256E | Glu | 0.25 | 0.043 | 17.3 | 240 ± 90 | 710 ± 270 |

| pCEM256G | Gly | 1.21 | 0.223 | 18.4 | 220 ± 50 | 520 ± 60 |

| pCEM256H | His | 1.27 | 0.287 | 22.6 | 310 ± 70 | 550 ± 80 |

| pCEM256I | Ile | 0.79 | 0.154 | 19.5 | 150 ± 110 | 510 ± 80 |

| pCEM256F | Phe | 0.54 | 0.081 | 15.0 | 260 ± 120 | 550 ± 70 |

| pCEM256P | Pro | 1.75 | 0.385 | 22.0 | 230 ± 90 | 490 ± 60 |

| pCEM256S | Ser | 0.42 | 0.113 | 27.0 | 140 ± 90 | 610 ± 40 |

| pCEM256T | Thr | 1.75 | 0.357 | 20.4 | 150 ± 120 | 570 ± 80 |

| pCEM256W | Trp | 2.16 | 0.402 | 18.6 | 290 ± 110 | 610 ± 70 |

| pCEM256Y | Tyr | 1.60 | 0.320 | 20.0 | 290 ± 160 | 610 ± 70 |

| pCEM256V | Val | 0.80 | 0.205 | 25.6 | 240 ± 90 | 560 ± 70 |

| pCEM256Stop | —c | 0.40 | 0.125 | 31.3 | 80 ± 10 | 730 ± 110 |

| pBluescript II SK+ | <0.0004 | NTd | NT | NT | NT | |

Each plasmid was introduced into JM39 with a defective chromosomal cysE gene, and soluble fractions from the cells were used as enzyme sources. The variations in the values were less than 5%.

ND, not detected.

—, termination codon at position 256.

NT, not tested.

To determine the production of l-cysteine plus l-cystine, all of the transformants were cultured in C1 medium at 30°C for 72 h (Table 1). It was found that in the recombinant strains carrying the mutant cysE gene there was marked production of l-cysteine plus l-cystine (50 to 300 mg/liter) due to the effect of the feedback resistance, while no l-cysteine plus l-cystine was detected in JM39 harboring the wild-type cysE gene.

Derivation of mutants that do not utilize l-cysteine.

Despite the fact that l-cysteine and l-cystine were produced when the mutant SAT gene was introduced into JM39, the production was unstable and decreased significantly during prolonged cultivation, probably because of cysteine-degrading enzymes, such as CD (data not shown). Because the presence of any cysteine-degrading enzyme seemed to be disadvantageous for constant production of l-cysteine, we attempted to isolate l-cysteine-nondegrading mutants which could be used as host strains. Several mutants which could grow on common M9 medium but not on the same medium containing l-cysteine as the sole nitrogen source were derived from strain JM39 with NTG treatment. One of these mutants, JM39-8, had only 10% of the CD activity of wild-type strain JM39 (0.0039 U/min/mg for JM39-8 versus 0.0353 U/min/mg for JM39). Strain JM39-8 was used as the host in the experiments described below.

Transformation of a mutant that does not utilize l-cysteine with plasmids having altered cysE and l-cysteine production by the recombinant strains.

The plasmids shown in Table 1 were introduced into mutant JM39-8, and production of amino acids was examined by culturing the transformants obtained (Table 1). In all of the transformants there was a general increase in production of l-cysteine plus l-cystine (range, 2- to 10-fold) compared to the transformants of JM39. The maximum level was observed in the strain having the Met-256-Ala mutant SAT gene (790 mg/liter). It is worth noting that a small amount of l-cysteine plus l-cystine (70 mg/liter) accumulated in the case of the wild-type SAT, while these amino acids were not produced when JM39 was used as the host. Also, the accumulated amino acids were stable after 96 h of cultivation in all cases, probably due to the lower level of degradation (data not shown). These results suggest that a cysteine-nondegrading mutant would be clearly advantageous for molecular breeding of an l-cysteine overproducer.

DISCUSSION

Organisms that overproduce various amino acids have been obtained by isolating mutants resistant to analogs of corresponding amino acids and have been successfully used for commercial production (14). Overproduction of l-cysteine by this type of mutant has never been reported. Denk and Böck (2) observed excretion of a small amount of l-cysteine by a revertant of a cysteine auxotroph of E. coli. This revertant had a genetically altered SAT, in which the methionine residue at position 256 was replaced by isoleucine and was insensitive to feedback inhibition by l-cysteine. These results suggested that it might be possible to obtain organisms that overproduce l-cysteine if the altered SAT could be amplified. Thus, we attempted to construct transformants having an amplified cysE gene coding for SAT by replacing the methionine at position 256 with other amino acids.

As expected, the transformants obtained that harbored altered cysE genes produced approximately 200 mg of l-cysteine plus l-cystine per liter. The production of these amino acids, however, was very unstable. Assuming that one of the reasons for this instability was the degradation of accumulated l-cysteine, l-cysteine-nondegrading mutants were derived as hosts for transformation. The level of production of l-cysteine plus l-cystine in these transformants was 2 to 10 times higher than the level of production when the parent was the host; the maximum level of production was approximately 790 mg/liter.

Replacement of the methionine residue at position 256 in wild-type SAT with other amino acids brought about both uniform desensitization to feedback inhibition by l-cysteine, irrespective of the amino acid residues, and a drastic reduction in the level of SAT. These results suggest that only the methionine residue had significance for both catalytic activity and sensitivity to inhibition by l-cysteine in the carboxy-terminal portion of the SAT protein. However, there is a question concerning why replacing Met-256 with leucine and lysine did not restore the cysteine requirement, which was presumably caused by a dramatic decrease in enzymatic activity. At present, the degrees of enzymatic activity and feedback desensitization do not correlate with the residue characteristics, such as charge, size, and hydrophobicity. Much more research on the catalytic mechanism of SAT performed with purified enzyme is needed, and an attempt to obtain high-level expression of the SAT gene is currently in progress. Recently, Leinfelder and Heinrich (6) demonstrated that l-cysteine and its derivatives were produced by transformants which had a mutation in the region of the amino acid from position 97 to position 273 or a truncation in the carboxy terminus of the SAT protein in the cysE gene. We are also trying to identify positions other than position 256 where amino acid residues could be replaced to obtain a higher level of desensitization.

Here we do not discuss the clear relationship between SAT specific activity and the amount of l-cysteine plus l-cystine because when we construct a potent microorganism for production of a metabolite such as an amino acid, generally we are faced with the problem that not only the level of key enzyme (such as SAT) but also the levels of the other enzymes involved in the biosynthesis of the metabolite need to be elevated by a gene dosage effect with a good balance in order to optimize the metabolic flow for formation of the target metabolite. In such a case, stable, balanced expression of several different genes in the host cells is essential (8). A stable supply derived from genetically engineered systems of precursors for l-cysteine, such as sulfide and l-serine, might increase l-cysteine production. Based on our data, it is thought that one copy or a low number of copies, not a high number of copies, of the mutant cysE gene desensitized to feedback inhibition might be sufficient for production of some l-cysteine plus l-cystine.

In addition, the regulation of gene expression in cysteine biosynthesis can be considered. In both E. coli and S. typhimurium, gene expression in the cysteine regulons is positively regulated by the transcriptional activator cysB and an inducer, N-acetyl-l-serine (9). Recently, cysB mutants that do not require an inducer and constitutively express the cysteine regulon were isolated by site-directed mutagenesis (1). Therefore, it may be that introduction of the cysB mutation into the overproducer described here will lead to an increase in the amount of l-cysteine, which is being sought.

In conclusion, the study described here demonstrates that stable expression of feedback-insensitive SAT is necessary for overproduction of l-cysteine.

REFERENCES

- 1.Colyer T E, Kredich N M. Residue threonine-149 of the Salmonella typhimurium CysB transcription activator: mutations causing constitutive expression of positively regulated genes of the cysteine regulon. Mol Microbiol. 1994;13:797–805. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1994.tb00472.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Denk D, Böck A. l-Cysteine biosynthesis in Escherichia coli: nucleotide sequence and expression of the serine acetyltransferase (cysE) gene from the wild-type and a cysteine excreting mutant. J Gen Microbiol. 1987;133:515–525. doi: 10.1099/00221287-133-3-515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Harris C L. Cysteine and growth inhibition of Escherichia coli: threonine deaminase as the target enzyme. J Bacteriol. 1981;145:1031–1035. doi: 10.1128/jb.145.2.1031-1035.1981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kredich N M. Regulation of cysteine biosynthesis in Escherichia coli and Salmonella typhimurium. In: Herrmann K M, Sommerville R L, editors. Amino acids: biosynthesis and genetic regulation. London, United Kingdom: Addison-Wesley Publishing Company; 1983. pp. 115–132. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kredich N M, Foote L J, Keenan B S. The stoichiometry and kinetics of the inducible cysteine desulfhydrase from Salmonella typhimurium. J Biol Chem. 1973;248:6187–6196. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Leinfelder W, Heinrich P. Process for preparing o-acetylserine, l-cysteine and l-cysteine-related products. PCT International publication WO 97/15673. 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Marchuk D, Drumm M, Saulino A, Collins F S. Construction of T-vectors, a rapid and general system for direct cloning of unmodified PCR products. Nucleic Acids Res. 1991;19:1154. doi: 10.1093/nar/19.5.1154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Morinaga Y, Takagi H, Ishida M, Miwa K, Sato T, Nakamori S. Threonine production by co-existence of cloned genes coding homoserine dehydrogenase and homoserine kinase in Brevibacterium lactofermentum. Agric Biol Chem. 1987;51:93–100. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ostrowski J, Jagura-Burdzy G, Kredich N M. DNA sequence of the cysB regions of Salmonella typhimurium and Escherichia coli. J Biol Chem. 1987;262:5999–6005. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sano K, Yokozeki K, Tamura F, Yasuda N, Noda I, Mitsugi K. Microbial conversion of dl-2-amino-Δ2-thiazoline-4-carboxylic acid to l-cysteine and l-cystine: screening of microorganism and identification of products. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1977;34:806–810. doi: 10.1128/aem.34.6.806-810.1977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tsunoda T, Eguchi S, Narui K. On the bioassay of amino acids. II. Determination of arginine, asparatic acid and cystine. Amino Acids. 1961;3:7–13. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yamada H, Kumagai H. Microbial and enzymatic processes for amino acid production. In: Tsuruya T, et al., editors. Chemistry for the welfare of mankind. Oxford, United Kingdom: Pergamon Press; 1979. pp. 1117–1127. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yoshinaga F, Nakamori S. Production of amino acids. In: Herrmann K M, Sommerville R L, editors. Amino acids: biosynthesis and genetic regulation. London, United Kingdom: Addison-Wesley Publishing Company; 1983. pp. 405–429. [Google Scholar]