Abstract

Galloway–Mowat syndrome is a rare autosomal-recessive genetic disorder that is characterized by variety of complications such as neurological abnormalities and early-onset progressive kidney disease. Studies have been shown that pathogenic mutations in genes that belong to the KEOPS complex lead to Galloway–Mowat syndrome. Several pathogenic mutations in OSGEP gene, a member of the KEOPS complex, have been detected in Galloway–Mowat syndrome. Here we describe a 12-year-old male with intellectual disability, poor speech, seizures, microcephaly, and nephrotic syndrome that were in favor of Galloway–Mowat syndrome, born to a healthy Iranian consanguineous parents. Extracted genomic DNA from blood sample was used to perform whole-exome sequencing in the patient. The mutational screening revealed a novel homozygote OSGEP gene missense variant. Our finding established whole-exome sequencing as a valuable technic for the detection of rare variants.

Keywords: Galloway–Mowat syndrome, KEOPS complex, OSGEP, Whole-exome sequencing

Introduction

Galloway–Mowat syndrome (GAMOS, OMIM 251,300) is a rare autosomal-recessive disorder characterized by early-onset nephrotic syndrome and associated with microcephaly, brain anomalies, and delayed psychomotor development [1]. The nephrotic syndrome occurs in the first months of life and is typically steroid resistant, followed by constant and rapid deterioration of renal function. The degree of renal anatomopathological damage is variable and ranges from minimal changes up to diffuse mesangial sclerosis [2]. Most patients also present dysmorphic facial features, including hypertelorism, ear abnormalities, and micrognathia [3]. Most affected individuals die in early childhood [4]. It has been estimated that the prevalence of this disease is about < 1/1,000,000 but it is likely that many cases remain misdiagnosed or undiagnosed [5]. GAMOS genetically is a heterogeneous disorder and there are several genes of KEOPS (Kinase, Endopeptidase and Other Proteins of small Size) complex that have an association with GAMOS. OSGEP is a member of KEOPS complex and plays an important role in tRNA threonylcarbamoyladenosine modification. Pathogenic variants in OSGEP gene are reported in GAMOS [6]. Here, we report a novel homozygous mutation in OSGEP gene in a 12-year-old boy with clinical manifestation of GAMOS that was born to an Iranian family with consanguineous marriage.

Case presentations

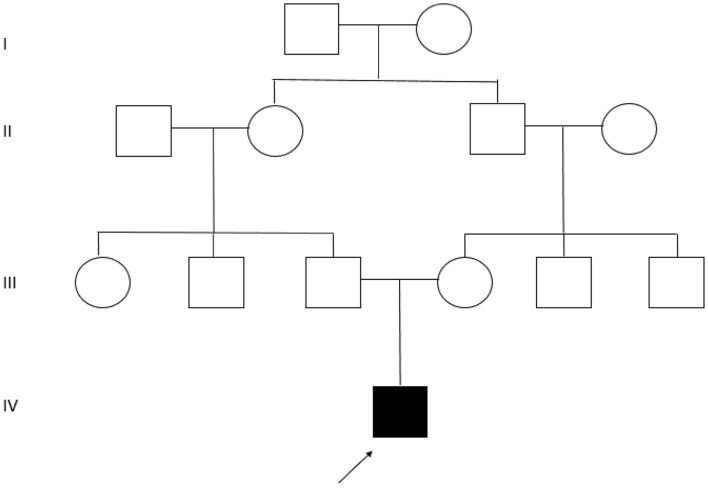

A 12-year-Old boy born to a healthy Iranian consanguineous parents originating from Azeri ethnic group (Fig. 1) was referred to Hope Generation Foundation Genetic Diagnosis Center. The patient manifested a complex phenotype and medical history including intellectual disability, poor speech, seizures started 20 days after birth, microcephaly, early-onset proteinuria, and nephrotic syndrome started at the first year of life. Brain MRI also had revealed cerebral atrophy and thin corpus callosum, that all were in favor of Galloway–Mowat syndrome. So, based on the clinical manifestation, informed consent was obtained from the parents and whole-exome sequencing was performed for the patient.

Fig. 1.

The pedigree of the index family: a black arrow in the pedigree specifies the proband with intellectual disability, poor speech, seizures, microcephaly, and nephrotic syndrome

DNA extraction and whole-exome sequencing

Using the salting out method, genomic DNA was isolated from the peripheral blood samples of the patient and his parents. The patient-extracted DNA was fragmented, and enriched for whole-exome sequencing using Agilent SureSelect V7 kit. The libraries were sequenced to mean > 90 × coverage on an Illumina Novaseq 6000 platform. The initial sequencing component of this test was performed by the Illumina genome sequencing service in Macrogen (Seoul, Korea).

Analysis of whole-exome sequencing data

Aligning the sequencing results to the human reference genome (GRCh37/hg19) was performed using the Burrows-Wheeler Aligner (BWA) program and variant calls are made using the genomic analyzer tool kit (GATK). Gene annotation of the variants is performed using Variant Effect Predictor (VEP) program. Common variants are filtered based on the available information from databases (including HGMD, ClinVar, 1000 Genome, ExAC, LSDBs, dbSNP and local database, Iranome), published literature, clinical correlation and its predicted function.

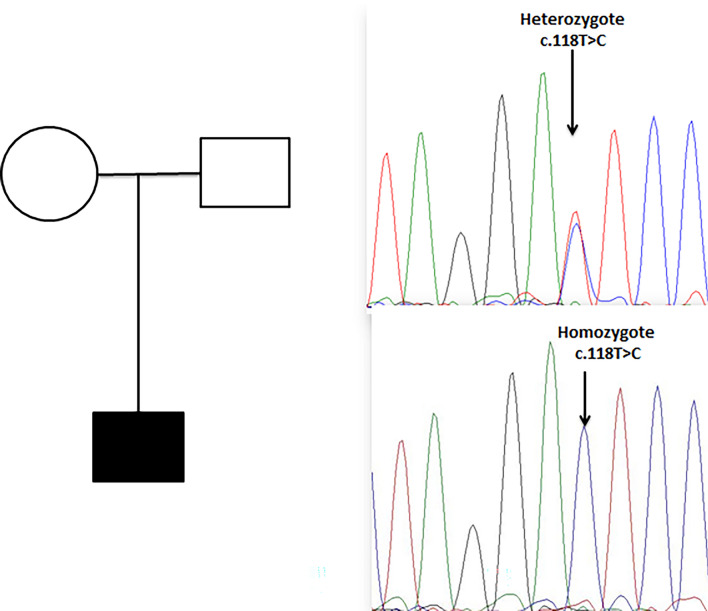

Sanger sequencing validation and segregation analysis

Finally, for variant validation and segregation analysis in the family, polymerase chain reaction (PCR) was performed to amplify the targeted region using specific primers (forward: 5’-GACCTGAAGGCTGAGTAGGG-3’, reverse: 5’-ACAACAGCCACAGAAACCAG-3’). The PCR products were then subjected to Sanger sequencing on an automated ABI PRISM 3130XL (Applied Biosystems, USA).

Results

Using bioinformatics filtering strategies and in silico analysis, a homozygous missense c.118 T > C was detected in the patient. According to the ACMG guidelines for the interpretation of sequence variants, this T to C transition was classified as likely pathogenic. Most bioinformatics prediction tools are also in favor of its pathogenicity (Table 1). In addition, this variant is completely absent in public genomic databases such as gnomAD and local genomic database Iranome. Segregation analysis in family members confirmed the segregation of the variant with the phenotype (Fig. 2).

Table 1.

In silico prediction results

| Location | Nucleotide change | Protein change | Prediction | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Condel | Mutation assessor | Mutation taster | PolyPhen | |||

| Exon 14 | c.118 T > C | p.Phe40Leu | Damaging | Damaging | Disease causing | Damaging |

Fig. 2.

Segregation analysis of index family. Parents are heterozygote and the patient ishomozygote for c.118 T > C variant

Discussion

Galloway–Mowat syndrome is a rare autosomal-recessive disorder that is described by various physical and developmental abnormalities such as microcephaly and nephrotic syndrome [7]. Till now, several mutations in different genes have been identified in the patients suffering from Galloway–Mowat syndrome [8]. KEOPS complex is a protein with five subunits that play essential role in development of animal. It has been proven that mutation in KEOPS genes causes Galloway–Mowat syndrome. The OSGEP gene encodes the O-sialoglycoprotein endopeptidase enzyme, which is a part of KEOPS complex and have critical role in tRNA threonylcarbamoyladenosine modification [5]. In humans, various pathogenic variants in OSGEP gene have been detected in individuals with Galloway–Mowat syndrome [5, 9]. The first case of Galloway–Mowat syndrome in Iran was reported by Maleki et al. In 2012, a 7-month-old infant boy from consanguineous parents with microcephaly, gastroesophageal reflux, multiple craniofacial characters, hypothyroidism, and nephrotic syndrome was identified. They suggested mutation in GMS1 gene may be implicated in this case [10]. In present study, we identified a novel homozygous missense variant c.118 T > C in OSGEP gene in a 12-year-old boy that had a clinical feature of Galloway–Mowat syndrome. Our in silico analysis with prediction software tools identified this variant as a probable source of damage. Segregation analysis confirmed our finding and revealed that patient’s parents are in the heterozygote state for this variant. Identification of the genetic cause of the disease for this family allowed us to evaluate the risk of the proband’s parents for having an affected child by prenatal testing during pregnancy and to arrange appropriate management. Although the detailed functional mechanism of this missense variant need more investigations, the progressive identification of genetic defects associated with this complications will eventually reveal the underlying pathological mechanisms and help develop more effective treatment strategies for patients.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

All the authors have declared no competing interest.

Ethical approval

All procedures performed in this study were in accordance with the ethical standards of Hope Generation Foundation Institute and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in this study.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Galloway WH, Mowat AP. Congenital microcephaly with hiatus hernia and nephrotic syndrome in two sibs. J Med Genet. 1968;5(4):319–321. doi: 10.1136/jmg.5.4.319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.B. B. A. De Vries, W. G. Van’t Hoff, R. A. H. Surtees, R. M. Winter, 2001 “Diagnostic dilemmas in four infants with nephrotic syndrome, microcephaly and severe developmental delay,” Clin. Dysmorpholl 10 (2) 115–121 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Braun DA, et al. Mutations in KEOPS-complex genes cause nephritic syndrome with primary microcephaly. Nat Genet. 2017;49(10):1529–1538. doi: 10.1038/ng.3933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pezzella M, et al. Galloway-Mowat syndrome: an early-onset progressive encephalopathy with intractable epilepsy associated to renal impairment. two novel cases and review of literature. Seizure. 2010;19(2):132–135. doi: 10.1016/j.seizure.2009.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.A. Domingo-Gallego et al “Novel homozygous OSGEP gene pathogenic variants in two unrelated patients with Galloway-Mowat syndrome: Case report and review of the literature”. BMC Nephrology 20 (1) 126 (2019) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 6.Lin PY, et al. Galloway-Mowat syndrome in Taiwan: OSGEP mutation and unique clinical phenotype. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2018;13(1):226. doi: 10.1186/s13023-018-0961-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rosti RO, et al. Extending the mutation spectrum for Galloway-Mowat syndrome to include homozygous missense mutations in the WDR73 gene. Am J Med Genet Part A. 2016;170(4):992–998. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.37533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hyun HS, et al. A familial case of Galloway-Mowat syndrome due to a novel TP53RK mutation: a case report. BMC Med Genet. 2018;19(1):131. doi: 10.1186/s12881-018-0649-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Teng H, Liang C, Liang D, Li Z, Wu L. Novel variants in OSGEP leading to galloway-Mowat syndrome by altering its subcellular localization. Clin Chim Acta. 2021;523:297–303. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2021.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Malaki M, Rafeey M. Infant boy with microcephaly gastroesophageal Refl ux and nephrotic syndrome (Galloway-Mowat Syndrome): a case report. Middle East J Dig Dis. 2012;4(1):51–54. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]