Abstract

The occurrence of DNA sequences encoding the hemolysin HblA complex and Bacillus cereus enterotoxin BceT, which have recently been confirmed as enterotoxins, was studied in Bacillus spp. To amplify these DNA sequences, PCR primer systems for the B component of hblA and for bceT DNA sequences were developed. The results from the amplification of hblA sequences correlated well with results obtained with the B. cereus enterotoxin (diarrheal type) test kit (RPLA kit), but not with the results of the Bacillus diarrheal enterotoxin visual immunoassay (BDE kit). Except for two thermophilic strains, all strains that were positive in PCR amplification assays with the hblA primers were also positive when tested with the RPLA kit. The hblA DNA sequence was found in 33 strains, and these strains were closely related according to 16S rDNA-RFLP analysis, except B. pasteurii. In PCR amplifications with the bceT primers only the model strain gave a positive signal. It is concluded that screening of the hemolysin HblA complex by the PCR method allows faster detection of enterotoxin production than does testing with the RPLA enterotoxin kit.

Some strains of Bacillus cereus and other Bacillus spp. cause food poisoning (24) and other infections (14). There are two principal types of food poisoning caused by B. cereus, namely, the emetic and the diarrheal types (23). As many as 50% of various spices, dairy products, and meat products contain B. cereus organisms; however, some products, such as mushrooms, are free of B. cereus (34, 37, 40). About half of B. cereus strains produce diarrheal enterotoxin (16, 30, 32). B. cereus strains can grow at temperatures between 4 and 37°C (36, 37), and psychrotrophic B. cereus strains can produce enterotoxin (11, 16, 18) both aerobically and anaerobically (17). Furthermore, the spores survive heat treatment, especially in foods that contain a lot of fat (23). B. cereus is also known to spoil milk and other food products (10, 29). Therefore, its presence in food processing plants should be minimal. Good diagnostic tools are thus required to ensure the hygienic quality of susceptible food items.

Several selective plating methods have been described for detecting B. cereus (20, 22, 25, 26, 33). The selection is based, for instance, on the ability of B. cereus to grow in the presence of polymyxin B and its lecithinase reaction (20). These methods require, with confirmatory testing, up to 4 days to perform. This is too time-consuming when inspecting products with short shelf-lives (e.g., dairy and fresh meat products). Another disadvantage of using selective media is that the growth of other microorganisms is not totally inhibited by any of the media designed to detect B. cereus. For identification of B. cereus, the miniaturized biochemical assay API 50 CHB has been used successfully (18, 34). The presence of B. cereus strains that cause food poisoning can also be indicated by their toxins.

The biochemical characterization of B. cereus enterotoxin(s) has not been completed. The action of enterotoxins at the molecular level is not well established (17); they are known to reverse the absorption of fluid, Na+, and Cl− and to cause malabsorption of glucose and amino acids; they can also cause neurosis and mucosal damage (23). Enterotoxins cause fluid accumulation in ligated rabbit ileal loops, are cytotoxic to cultured cells, and are lethal to mice after intravenous injection (4, 35). The preformed toxin is destroyed after digestion by pH and proteolytic enzymes of the gut. Therefore, the diarrheal form of food poisoning is proposed to be due to bacteria growing in the intestine. Spores, which survive indigestion, proceed to sporulate, grow, and produce toxin in the intestine (14, 17, 24, 31). Hemolysin BL (hblA [19]) may indicate the presence of enterotoxin in B. cereus. Beecher and MacMillan (4) showed that hemolysin BL binds component B, which either binds to or alters the cells, allowing component L to lyse the cells. bceT is another possible indicator of the presence of enterotoxin. Agata et al. (1) cloned and sequenced a 2.9-kb toxin gene fragment from B. cereus B-4ac. The gene fragment (bceT) was expressed in Escherichia coli. The translated product exhibited Vero cell cytotoxicity and was found to be positive in a vascular permeability assay; however, the responses were lower than with the parent strain.

To test for the presence of hblA and bceT in bacterial strains or in food, two methods have been proposed: animal tests or immunological tests. There are commercial kits designed to detect enterotoxic B. cereus bacteria via immunological reactions. Two commonly used immunoassays have been found to detect different antigens (9, 10, 13). The Bacillus diarrheal enterotoxin visual immunoassay (BDE kit; Tecra) detects two proteins of 40 and 41 kDa which are apparently nontoxic proteins (6). The B. cereus enterotoxin (diarrheal type) test kit (RPLA kit; Oxoid) is specific to the L2 component of the hemolysin BL complex.

Another approach for detecting B. cereus is to amplify a specific, unique DNA sequence of the organism. Such a DNA test would provide additional information about the potential risks involved with a food product and could, if successful, replace the plating and immunological methods for detecting the presence of enterotoxic B. cereus.

Toxin production has been mainly reported for strains of B. cereus. However, the taxonomy and phylogeny of the genus Bacillus has been under debate, and many changes have been proposed. Phylogenetic analysis based on 16S ribosomal DNA (rDNA) have shown that B. cereus is closely related to B. anthracis, B. mycoides, and B. thuringiensis (2, 7). Ash et al. (3) divided the genus Bacillus into five groups according to reverse transcriptase sequencing of 16S rRNA, with one group consisting of B. cereus, B. mycoides, and B. thuringiensis. In contrast, Nakamura and Jackson (27) showed that, based on DNA reassociation studies, these three species belong to taxonomically distinct groups.

The aim of the present study was to develop rapid and accurate diagnostic tools for detecting B. cereus and its enterotoxic potential. We therefore studied the occurrence of the hemolysin hblA and bceT genes in different Bacillus strains to see whether their presence correlates with enterotoxicity. In order to determine the phylogenetic position of the enterotoxic strains studied, we performed 16S rDNA restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP) analyses.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains.

A group of 80 strains representing enterotoxic and nonenterotoxic B. cereus and other Bacillus species (Table 1) were grown in brain heart infusion (BioKar Diagnostics) supplemented with 1% (wt/vol) glucose overnight at 37°C with shaking (150 rpm). The cells were collected by centrifugation at 5,000 × g for 10 min and resuspended in 525 μl of TE buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl, 1 mM EDTA [pH 8]; Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, Mo.), and DNA was extracted by lysozyme enzyme (Sigma) digestion followed by CTAB-chloroform extraction and isopropanol (E. Merck AG, Darmstadt, Germany) precipitation. First, 5 μl of proteinase K (20 mg/ml; Promega, Madison, Wis.) and 40 μl of lysozyme (50 mg/ml) were added to the cell suspension. This mixture was incubated for 1 h at 37°C and then 30 μl of 10% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS; Merck) and 100 μl of 10% N-lauroylsarcosine (Sigma) were added. The suspension was incubated for 30 min, and the volume was adjusted to 3,000 μl by adding 1,420 μl of TE buffer and 420 μl of 5 M NaCl. For purification, 300 μl of preheated (65°C) 10% CTAB in 0.7 M NaCl was added, and the mixture was incubated for 10 min at 65°C. One phenol-chloroform-isoamyl alcohol purification was performed by adding an equal volume of phenol-chloroform-isoamyl alcohol (25:24:1), and the mixture was centrifuged at 10,000 × g for 20 min. This procedure was followed by chloroform-isoamyl alcohol extraction and precipitation with an equal volume of isopropanol and centrifugation 10,000 × g for 15 min. The DNA was resuspended in 100 μl of TE buffer.

TABLE 1.

Bacillus strains used in this study and comparison of the different methods for detecting B. cereus enterotoxin

| Straina | Presence of enterotoxin as determined by:

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PCRb | Oxoid BCETRPLAc | BDEd | BHEMORFLPe | |

| B. amyloliquefaciens ATCC 23842 | − | ND | ND | |

| B. badius DSM 23 | − | ND | ND | |

| B. brevis DSM 30 | − | ND | ND | |

| B. brevis ATCC 10027 | − | ND | ND | |

| B. cereus PHLS F837/76* | + | 64 | ND | I |

| B. cereus B-4ac* | + | 64 | 4 | I |

| B. cereus DSM 2301* | + | 64 | 3 | I |

| B. cereus DSM 4282* | + | 64 | 3 | I |

| B. cereus DSM 31 | + | 64 | ND | I |

| B. cereus ATCC 7064 | + | 64 | ND | I |

| B. cereus ATCC 27877 | + | 64 | 3 | I |

| B. cereus NCFB577 | + | 64 | 3 | II |

| B. cereus NCFB 578 | + | 64 | 3 | III |

| B. cereus NCFB 579 | + | 64 | 4 | II |

| B. cereus NCFB 634 | + | 64 | 2 | II |

| B. cereus NCFB 719 | + | ND | ND | III |

| B. cereus PHLS F528/94 | + | 64 | ND | I |

| B. cereus PHLS F3453/94 | + | 64 | ND | I |

| B. cereus SMR137 | + | 64 | ND | I |

| B. cereus SMR 161 | + | 64 | 4 | III |

| B. cereus K5T9 (TP) | + | 32 | − | II |

| B. cereus FB11 (TP) | + | 32 | − | I |

| B. cereus EA160 (TP) | + | 16 | 2 | I |

| B. cereus MC 23 (TP) | + | 32 | 3 | I |

| B. cereus B 738 (TP) | + | 64 | − | I |

| B. cereus FA2 (TP) | + | 2 | − | I |

| B. cereus E 35 (TP) | + | 8 | 3 | I |

| B. cereus K5T4 (TP) | + | 16 | − | I |

| B. cereus B 667 (TP) | + | 32 | − | I |

| B. cereus B 922 (TP) | + | 4 | 2 | I |

| B. cereus ATCC 12826 | − | − | ND | |

| B. cereus ATCC 14579 | − | − | ND | |

| B. cereus NCFB 721 | − | − | ND | |

| B. cereus NCFB 722 | − | − | ND | |

| B. cereus NCFB 723 | − | ND | ND | |

| B. cereus NCFB 826 | − | ND | ND | |

| B. cereus NCFB 827 | − | ND | ND | |

| B. cereus NCFB 836 | − | ND | ND | |

| B. cereus NCFB 1938 | − | ND | ND | |

| B. cereus PHLS F5881/94 | − | − | ND | |

| B. cereus SMR 178 | − | − | ND | I |

| B. cereus SMR 181 | − | ND | ND | |

| B. cereus SMR 182 | − | ND | ND | |

| B. cereus SMR 725 | − | ND | ND | |

| B. cereus SMR 729 | − | ND | ND | |

| B. cereus SMR 731 | − | ND | ND | |

| B. cereus SMR 740 | − | ND | ND | |

| B. cereus E21 (TP) | − | − | ND | |

| B. cereus ER25 (TP) | − | ND | ND | |

| B. cereus FB12 (TP) | − | ND | ND | |

| B. cereus K5T3 (TP) | − | ND | ND | |

| B. cereus EMC 92 (TP) | − | ND | ND | |

| B. cereus IH41064 (KTL) | − | − | ND | |

| B. cereus IH41385 (KTL) | − | ND | ND | |

| B. circulans ATCC 4513 | − | ND | ND | |

| B. coagulans DSM 1 | − | − | ND | |

| B. firmus DSM 12 | − | ND | ND | |

| B. laterosporus DSM 25 | − | ND | ND | |

| B. lentus DSM 9 | − | ND | ND | |

| B. macerans DSM 24 | − | ND | ND | |

| B. mycoides ATCC 6462 | − | ND | ND | |

| B. mycoides ATCC 11986 | − | ND | ND | |

| B. mycoides NCFB 681 | − | ND | ND | |

| B. mycoides NCFB 682 | − | ND | ND | |

| B. mycoides NCFB 718 | − | ND | ND | |

| B. mycoides NCFB 1136 | + | 64 | 3 | I |

| B. mycoides NCFB 1152 | + | 64 | 3 | III |

| B. pasteurii DSM 33 | + | 64 | 4 | II |

| B. simplex DSM 1317 | − | ND | ND | |

| B. smithii DSM 459 | + | − | ND | I |

| B. sphaericus DSM 28 | − | ND | ND | |

| B. subtilis DSM 618 | − | ND | ND | |

| Bacillus sp. DSM 54 | − | ND | ND | |

| Bacillus sp. DSM 405 | − | ND | ND | |

| Bacillus sp. DSM 406 | − | ND | ND | |

| Bacillus sp. DSM 411 | − | ND | ND | |

| Bacillus sp. DSM 465 | − | ND | ND | |

| Bacillus sp. DSM 466 | + | − | ND | I |

| Bacillus sp. DSM 730 | − | ND | ND | |

| B. thuringiensis NCFB 1157 | + | 64 | 2 | I |

Abbreviations: An asterisk indicates that the strain was found to be enterotoxic in a previous study. ATCC = American Type Culture Collection, Rockville, Md.; DSM = Deutsche Sammlung von Mikroorganismen und Zellkulturen GmbH, Braunschweig, Germany; NCFB = National Collection of Food Bacteria, AFRC Institute of Food Research, Reading, United Kingdom; PHLS = Food Hygiene Laboratory, Central Public Health Laboratory, London, United Kingdom; SMR = Swedish Dairies’ Association, Lund, Sweden; KTL = National Public Health Institute, Helsinki, Finland; TP = strains used in Pirttijärvi et al. (30).

PCR was done with HblA primers.

The results are recorded according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The numbers refer to the strength of the reaction, e.g., “4” is a weak reaction, and “64” is a strong reaction. ND, Not determined.

The results are recorded according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The numbers refer to the strength of the reaction. ND, Not determined.

Hemolysin PCR-RFLP types: type I cuts like model hblA sequence of B. cereus F837/76, in type II the restriction pattern is different with RsaI and TaqI restriction enzymes, and in type III the restriction pattern is different with TaqI.

Primers.

The hemolysin hblA gene-specific primers were designed with the GCG program package (Genetics Computer Group, Madison, Wis.) and the EMBL and GenBank data banks. The hemolysin BL gene of the B. cereus F837/76 DNA sequence (L20441 [19]) was used for sequence analysis. The sequence for the hblA primer for HblA1 was 5′-GCTAATGTAGTTTCACCTGTAGCAAC-3′, and the sequence for the hblA primer for HblA2 was 5′-AATCATGCCACTGCGTGGACATATAA-3′. The primers for the bceT gene were designed by using the corresponding DNA sequence of B. cereus B-4ac (D17312 [1]). The sequence for the bceT primer for BceT1 was 5′-GAATTCCTAAACTTGCACCATCTCG-3′, and the sequence for the bceT primer for BceT2 was 5′-CTGCGTAATCGTGAATGTAGTCAAT-3′. The same DNA sequences were used for the selection of restriction enzymes in the restriction map analysis (GCG package). For 16S rDNA amplification, rD1 and fD1 primers (39) were used.

PCRs.

One microliter of DNA (ca. 5 ng of DNA) from each of the different strains was amplified by PCR. The PCR conditions were optimized for annealing temperature and MgCl2 concentration. The final reaction mixture (50 μl) contained 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.8) at 25°C, 50 mM KCL, 0.1% Triton X-100, 200 μM concentrations of each dNTP, and 25 pmol of primers HblA1 and HblA2 or primers Bcet1 and Bcet2. The Dynazyme DNA polymerase was added after the reaction mixture had been heated to an 80°C “hot start” (12). PCR analyses were performed in a MJ PTC-200 thermocycler with a heated lid. Thermal cycles for the HblA primers were as follows: 5 cycles at 94°C for 30 s, at 70°C for 1 min, and at 72°C for 1.5 min followed by 30 cycles at 94°C for 30 s, at 65°C for 1 min, and at 72°C for 1.5 min. The bceT fragment was amplified by using 30 cycles (94°C for 45 s, 65°C for 45 s, and 72°C for 1 min). 16S rDNA was amplified by using 35 cycles (94°C for 1 min, 55°C for 1 min, and 72°C for 2 min). The amplification results were analyzed in 1% agarose gels (0.5× TAE buffer [0.02 M Tris-acetate, 0.001 M EDTA]) containing ethidium bromide (0.25 mg/ml), and electrophoresis was carried out for 2 h at 200 V.

Hybridization protocol.

The hblA amplification product of B. cereus F837/76 was cloned in Epicurian coli (Stratagene) by using the pZero vector (Invitrogen). The plasmid was extracted, labeled with digoxigenin-11-dUTP during PCR with HblA primers, with all other reaction conditions matching the manufacturer’s instructions (Boehringer GmbH, Mannheim, Germany), and then used as a probe in Southern blot hybridization. Then 100 ng of total DNA was electrophoresed overnight (20 h) at 30 V in 0.8% agarose gel in TAE buffer. The gel was treated with 0.25 M HCl for 10 min, followed by 30 min in 0.4 N NaOH. A positively charged nylon membrane (Boehringer Mannheim) was treated with 2× SSC (1× SSC is 0.15 M NaCl plus 0.015 M sodium citrate), and then the DNA was transferred into the membrane with a vacuum-blotting apparatus for 2 h (2016 Vacugene; LKB Bromma). The hybridization reaction was done overnight according to the digoxigenin hybridization protocol at a hybridization temperature of 60°C. The membrane was washed in 2× SSC containing 0.1% SDS at room temperature, and stringent washing was performed at 60°C in 0.5× SSC containing 0.1% SDS. The detection was done according to the manufacturer’s instructions (colorimetric detection with nitroblue tetrazolium and 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolylphosphate).

RFLP analysis.

The hemolysin amplification fragment was digested with RsaI, TaqI, and XbaI (all from Promega). 16S rDNA RFLP analyses were performed on 56 strains with CfoI, HaeIII, MspI, and RsaI (all from Promega). The digested PCR products were run at 200 V for 5.5 h in 5% agarose gels (0.5× TAE buffer) containing (0.25 mg/ml) ethidium bromide by using a water-cooled gel electrophoresis apparatus (SuperSub; Hoefer Scientific Instruments, San Francisco, Calif.). Further analysis of the gel results was done with the Gelcompar program package (GelCompar, comparative analysis of electrophoresis patterns version 4.0; Applied Maths, Kortrijk, Belgium).

Enterotoxin immunoassays.

The strains found to be positive in the PCR assay were analyzed by using two commercial immunoassay kits, BCET-RPLA (Oxoid; Unipath Ltd., Basingstoke, England) and BDE (Tecra Diagnostics; Biotech Australia, Roseville, Australia). The assays were performed according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

RESULTS

The average amount of DNA extracted from different Bacillus strains was 5.6 μg/ml. Under optimized PCR conditions, an hblA amplification product was obtained from 33 of the Bacillus strains (Table 1). These strains representing both enterotoxic and nonenterotoxic B. cereus strains as indicated in previous studies. Furthermore, B. pasteurii DSM 33, B. mycoides NCFB 1136 and 1152, B. smithii DSM 459, Bacillus sp. DSM 466, and B. thuringiensis NCFB 1157 were all found to be positive in the hblA test. Only the B. cereus strain B-4ac gave an amplification product with primers designed to detect the bceT DNA sequence.

To confirm that the PCR amplification products represented the hblA sequence, Southern blots with total DNA from 16 strains were hybridized with an hblA probe. The results from the hybridization assay confirmed that the hemolysin hblA gene is present both in enterotoxic and nonenterotoxic strains. In the hybridization assay we tested nine strains that were PCR positive for hemolysin and four strains that were PCR negative for hemolysin. Seven of the PCR-positive strains had similar hybridization signals in Southern blots with digested total DNA, and two of the PCR-positive strains showed some polymorphism. One of the PCR-negative strains (ATCC 12826) gave a signal which appeared in a larger DNA fragment of the total DNA digestion than in the control strain F837/76 (data not shown).

Hemolysin PCR-RFLP.

To see if any polymorphism could be detected within the amplified PCR products, we performed PCR-RFLP analyses of the hblA amplification products of the PCR-positive strains. The amplification products were digested with RsaI, TaqI, and XbaI. The expected digestion patterns were obtained from the EMBL data bank by using the hemolysin sequence from B. cereus F837/76 (accession no. L20441). Our forward primer starts at 121 bp, and the reverse primer ends at 994 bp. The expected cut for RsaI is at nucleotide 347, and the sizes of the digestion products were 227 and 647 bp. The expected cut for TaqI is at 932 (with digestion products of 62 and 812 bp), and the expected cut for XbaI is at 699 (with digestion products of 295 and 579 bp). Nine strains showed polymorphism in comparison with most of the strains, giving different digestion patterns either with TaqI alone or with RsaI and TaqI (Table 1).

Immunological enterotoxin assay.

The strains which were toxin gene positive in the hemolysin PCR assay were also toxin positive when tested with the BCET-RPLA enterotoxin kit (Table 1).

16S rDNA RFLP analysis.

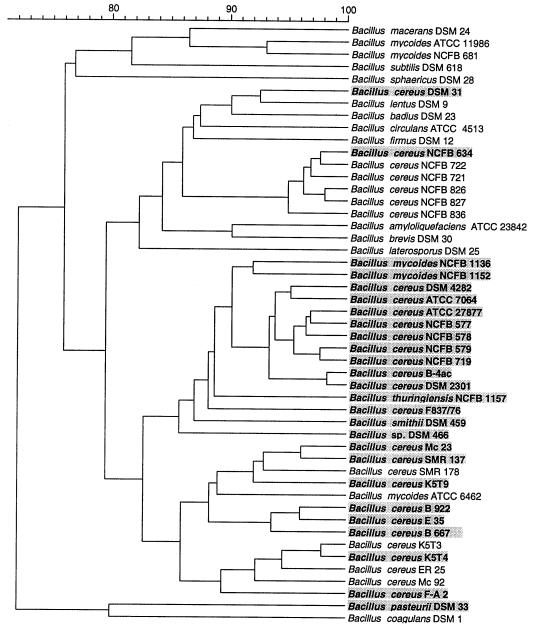

Fifty strains were included in the 16S rDNA analysis. The analysis showed that the enterotoxic strains are closely related Bacillus strains (Fig. 1).

FIG. 1.

Dendrogram of B. cereus strains based on 16S rDNA RFLP analysis with GelCompar program package (UPGMA method). The strains in the shaded boxes were found to be positive by hblA PCR amplification.

DISCUSSION

The development of B. cereus diagnostic assays is important because these organisms produce many proteolytic enzymes, many of which are toxic for animals and humans. Therefore, we wanted to develop a rapid and reliable method for detecting enterotoxic Bacillus strains based on their toxin genes. We designed two PCR primer systems, one that would amplify hblA DNA sequences and another that would amplify bceT DNA sequences. A gene product corresponding to hblA was detected by PCR in 33 of 108 tested strains. Agata et al. (1) found in their PCR assay that all 10 of the strains they tested were bceT positive. In our study only the bceT gene model strain B-4ac was found to be positive with our bceT primers. We did not have access to the other bceT gene-positive reference strains included in the study by Agata et al. (1). However, we found that the bceT gene seems to be relatively rare and could not be found in the enterotoxic strains used in this study. This is in contrast to the results of Agata et al. (1). Therefore, the bceT method does not seem to be a good diagnostic probe for assessing the enterotoxic potential of Bacillus strains.

RPLA is a simple and highly sensitive immunological method. The BCET-RPLA kit (Oxoid) is designed to detect B. cereus enterotoxin. It does not react with the crude toxins of B. licheniformis, B. pumilus, or B. subtilis. However, it does react with the crude toxin from B. thuringiensis, which is closely related to B. cereus (32). The results obtained with RPLA immunoassays are in general agreement with those of the cell culture assays, but some of the strains can give false results (8, 28). In our study the RPLA kit gave positive results with all strains that were found to be positive in the hblA PCR assay, including B. mycoides, B. pasteurii, and B. thuringiensis strains. The only exceptions were two thermotolerant Bacillus strains, namely, B. smithii DSM 459 and Bacillus sp. strain DSM 466, which were positive with hblA PCR primers but which failed to give positive immunological reactions. Since the enterotoxin is thermolabile (23), the negative immunological reactions were probably due to the long growth time and high growth temperature: 55°C for B. smithii and 60°C for Bacillus sp. strain DSM 466. The Tecra enterotoxin kit does not test enterotoxic protein but proteins which apparently are nontoxic. Therefore, it was not surprising that the results with this immunological assay did not correlate with those from our PCR assays.

The hybridization studies with the hblA probe proved that DNA sequences that code for HblA could be found in the PCR-positive strains and that the hybridization signals were similar, i.e., some length variation was observed, with the strains tested. The reason for the unexpected hybridization signal of strain ATCC 12826 could be that the hemolysin gene it carries has changed. The results obtained in this study, i.e., the difference in hybridization signal and the negative reactions in enterotoxin assays (hemolysin PCR and immunological enterotoxin assays), all support the conclusion that B. cereus ATCC 12826 is not enterotoxic. To study the discrepancies noticed in the hybridization results, we performed an RFLP analysis of the hblA PCR product.

The hblA PCR products were found to be slightly heterogeneous by the PCR-RFLP method (Table 1). RsaI and TaqI grouped the amplification products into three types (I, II, and III). The PCR products of nine strains could be separated from that of the model strain by cutting with RsaI and/or TaqI. These minor differences seemed not to affect the enterotoxic potential of the strains because they were found to be positive by immunological assay with the RPLA kit. The different restriction patterns obtained from the amplification products with hemolysin primers could reflect rearrangements in the gene region or may be the results of mutational changes. The results presented in this study show that the hemolysin hblA gene could be detected both in strains which, according to previously published information, were enterotoxic and in nonenterotoxic strains (culture collection information). With the BCET-RPLA test (Oxoid), 85% of the psychrotrophic Bacillus spp. (n = 83) were reported to be enterotoxin positive (18), whereas the average of enterotoxic strains of B. cereus is 50%. With our PCR assay 28 of the 62 (45%) tested B. cereus strains were found to be positive, and these strains also gave a positive immunological reaction with the RPLA kit.

A rapid and reliable method for detecting enterotoxin is very important to ensure that food products are safe. Since contamination levels may be low, the detection method should sensitive enough to be able to detect low numbers of B. cereus organisms as quickly as possible. The PCR method for testing the hblA sequence is a sensitive and fast method for testing food products and determining their enterotoxic potential.

The 16S rDNA RFLP analysis showed that the strains which harbored the hemolysin B component, i.e., strains that were found to be positive by PCR analysis with hblA primer, were closely related to one another (Fig. 1). Only B. pasteurii was separated further from the other hemolysin-positive strains according to 16S rDNA RFLP analysis. However, Bacillus species which were not hemolysin positive were dispersed among the strains harboring the hemolysin gene. We therefore conclude that the 16S rDNA gene and the hemolysin gene have different evolutionary histories.

The B. cereus enterotoxin has been detected by using immunological kits, such as the BCET-RPLA kit. However, the analysis takes 2 days to perform. The screening for the hblA gene by the PCR method provides similar results faster provided suitable sample preparation protocols are applied. In the literature several successful PCR assays have been described in which the detection has been accomplished within 1 day (15, 38). The PCR amplification procedure, with preparation of master mixtures, application of thermal cycles, and reading of the results, can be completed in ca. 2 h. Furthermore, PCR amplification products can be further analyzed by restriction enzyme digestion, which is helpful in epidemiological studies. Additional target genes, such as 16S rDNA, provide further information for epidemiological studies. The usage of this methodology should therefore prove useful in food laboratories.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank M. S. Salkinoja-Salonen for providing some of the Bacillus strains and Anne Mäkinen for excellent technical support.

This study was part of a Nordic Industry foundations NORDFOOD project RAPID CONTROL METHODS (P93155) funded by TEKES (Technology Development Centre, Helsinki, Finland), Finnzymes Oy (Helsinki, Finland), and Ingman Foods Oy Ab (Helsinki, Finland). Additional funding was provided by The Academy of Finland (ABS Graduate School) and the Walter Ehrström foundation.

REFERENCES

- 1.Agata N, Ohta M, Arakawa Y, Mori M. The bceT gene of Bacillus cereus encodes an enterotoxic protein. Microbiology. 1995;141:983–988. doi: 10.1099/13500872-141-4-983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ash C, Farrow J A E, Dorsch M, Stackebrandt E, Collins M D. Comparative analysis of Bacillus anthracis, Bacillus cereus, and related species on the basis of reverse transcriptase sequencing of 16S rRNA. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1991;41:343–346. doi: 10.1099/00207713-41-3-343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ash C, Farrow J A E, Wallbanks S, Collins M D. Phylogenetic heterogeneity of the genus Bacillus revealed by comparative analysis of small-subunit-ribosomal RNA sequences. Lett Appl Microbiol. 1991;13:202–206. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Beecher D J, MacMillan J D. A novel biocomponent hemolysin from Bacillus cereus. Infect Immun. 1990;58:2220–2227. doi: 10.1128/iai.58.7.2220-2227.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Beecher D J, MacMillan J D. Characterization of the components of hemolysin BL from Bacillus cereus. Infect Immun. 1991;59:1778–1784. doi: 10.1128/iai.59.5.1778-1784.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Beecher D J, Wong A C L. Identification and analysis of the antigens detected by two commercial Bacillus cereus diarrheal enterotoxin immunoassay kits. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1994;60:4614–4616. doi: 10.1128/aem.60.12.4614-4616.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bourque S N, Valero J R, Lavoie M C, Levesque R C. Comparative analysis of the 16S to 23S ribosomal intergenic spacer sequences of Bacillus thuringiensis strains and subspecies and of closely related species. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1995;61:1623–1626. doi: 10.1128/aem.61.4.1623-1626.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Buchanan R L, Schultz F J. Evaluation of the Oxoid BCET-RPLA kit for the detection of Bacillus cereus diarrheal enterotoxin as compared to cell culture cytotoxicity. J Food Prot. 1992;55:440–443. doi: 10.4315/0362-028X-55.6.440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Buchanan R L, Schultz F J. Comparison of the Tecra VIA kit, Oxoid BCET-RPLA kit and CHO cell culture assay for the detection of Bacillus cereus diarrhoeal enterotoxin. Lett Appl Microbiol. 1994;19:353–356. doi: 10.1111/j.1472-765x.1994.tb00473.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Christiansson A. Enterotoxin production in milk by Bacillus cereus: a comparison of methods for toxin detection. Neth Milk Dairy J. 1993;47:79–87. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Christiansson A, Naidu A S, Nilsson I, Wadström T, Pettersson H-E. Toxin production by Bacillus cereus dairy isolates in milk at low temperatures. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1989;55:2595–2600. doi: 10.1128/aem.55.10.2595-2600.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.D’Aquila R T, Bechtel L J, Videler J A, Eron J J, Gorczyca P, Kaplan J C. Maximizing sensitivity and specificity of PCR by pre-amplification heating. Nucleic Acids Res. 1991;19:3749. doi: 10.1093/nar/19.13.3749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Day T L, Tatini S R, Notermans S, Bennett R W. A comparison of ELISA and RPLA for detection of Bacillus cereus diarrhoeal enterotoxin. J Appl Bacteriol. 1994;77:9–13. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.1994.tb03037.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Drobniewski F A. Bacillus cereus and related species. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1993;6:324–338. doi: 10.1128/cmr.6.4.324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Galindo I, Rangel-Aldao R, Ramírez J L. A combined polymerase chain reaction-colour development hybridization assay in a microtitre format for the detection of Clostridium spp. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 1993;39:553–557. doi: 10.1007/BF00205050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Granum P E, Brynestad S, Kramer J M. Analysis of enterotoxin production by Bacillus cereus from dairy products, food poisoning incidents and non-gastrointestinal infections. Int J Food Microbiol. 1993;17:269–279. doi: 10.1016/0168-1605(93)90197-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Granum P E, Brynestad S, O’Sullivan K, Nissen H. Enterotoxin from Bacillus cereus: production and biochemical characterization. Neth Milk Dairy J. 1993;47:63–70. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Griffiths M W. Toxin production by psychrotrophic Bacillus spp. present in milk. J Food Prot. 1990;53:790–792. doi: 10.4315/0362-028X-53.9.790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Heinrichs J H, Beecher D J, MacMillan J D, Zilinskas B A. Molecular cloning and characterization of the hblA gene encoding the B component of hemolysin BL from Bacillus cereus. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:6760–6766. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.21.6760-6766.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Holbrook R, Andersson J M. An improved selective and diagnostic medium for the isolation and enumeration of Bacillus cereus in foods. Can J Microbiol. 1980;26:753–759. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hood A M, Tuck A, Dane C R. A medium for the isolation, enumeration and rapid presumptive identification of injured Clostridium perfringens and Bacillus cereus. J Appl Bacteriol. 1990;69:359–372. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.1990.tb01526.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kim H U, Goepfert J M. Enumeration and identification of Bacillus cereus in foods. I. 24-Hour presumptive test medium. Appl Microbiol. 1971;22:581–587. doi: 10.1128/am.22.4.581-587.1971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kramer J M, Gilbert R J. Bacillus cereus and other Bacillus species. In: Doyle M P, editor. Foodborne bacterial pathogens. New York, N.Y: Marcel Dekker, Inc.; 1989. p. 796. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lund B M. Foodborne disease due to Bacillus and Clostridium species. Lancet. 1990;336:982–986. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(90)92431-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Meira de Vasconcellos F J, Rabinovitch L. A new formula for an alternative culture medium, without antibiotics, for isolation and presumptive quantification of Bacillus cereus in foods. J Food Prot. 1995;58:235–238. doi: 10.4315/0362-028X-58.3.235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mossel D A A, Koopman M J, Jongerius E. Enumeration of Bacillus cereus in foods. Appl Microbiol. 1967;15:650–653. doi: 10.1128/am.15.3.650-653.1967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nakamura L K, Jackson M A. Clarification of the taxonomy of Bacillus mycoides. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1995;45:46–49. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Notermans S, Tatini S. Characterization of Bacillus cereus in relation to toxin production. Neth Milk Dairy J. 1993;47:71–77. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Overcast W W, Atmaram K. The role of Bacillus cereus in sweet curdling of fluid milk. J Milk Food Technol. 1974;37:233–236. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pirttijärvi T S M, Graeffe T H, Salkinoja-Salonen M S. Bacterial contaminants in liquid packaging boards: assessment of potential for food spoilage. J Appl Bacteriol. 1996;81:445–458. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.1996.tb03532.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shinagawa K, Ichikawa K, Matsusaka N, Sugii S. Purification and some properties of a Bacillus cereus mouse lethal toxin. J Vet Med Sci. 1991;53:469–474. doi: 10.1292/jvms.53.469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shinagawa K. Serology and characterization of toxigenic Bacillus cereus. Neth Milk Dairy J. 1993;47:89–103. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Szabo R A, Todd E C D, Rayman M K. Twenty-four hour isolation and confirmation of Bacillus cereus in foods. J Food Prot. 1984;47:856–860. doi: 10.4315/0362-028X-47.11.856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.te Giffel M C, Beumer R R, Leijendekkers S, Rombouts F M. Incidence of Bacillus cereus and Bacillus subtilis in foods in the Netherlands. Food Microbiol. 1996;13:53–58. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Thompson N E, Ketterhagen M J, Bergdoll M S, Schantz E J. Isolation and some properties of an enterotoxin produced by Bacillus cereus. Infect Immun. 1984;43:887–894. doi: 10.1128/iai.43.3.887-894.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Väisänen O M, Mwaisumo N J, Salkinoja-Salonen M S. Differentiation of dairy strains of the Bacillus cereus group by phage typing, minimum growth temperature, and fatty acid analysis. J Appl Bacteriol. 1991;70:315–324. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.1991.tb02942.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.van Netten P, van de Moosdijk A, van Hoensel P, Mossel D A A, Perales I. Psychrotrophic strains of Bacillus cereus producing enterotoxin. J Appl Bacteriol. 1990;69:73–79. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.1990.tb02913.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wegmüller B, Lüthy J, Candrian U. Direct polymerase chain reaction detection of Campylobacter jejuni and Campylobacter coli in raw milk and dairy products. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1993;59:2161–2165. doi: 10.1128/aem.59.7.2161-2165.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Weisburg W G, Barns S M, Pelletier D A, Lane D J. 16S ribosomal DNA amplification for phylogenetic study. J Bacteriol. 1991;173:697–703. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.2.697-703.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wong H-C, Chang M-H, Fan J-Y. Incidence and characterization of Bacillus cereus isolates contaminating dairy products. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1988;54:699–702. doi: 10.1128/aem.54.3.699-702.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]