Abstract

Background

Low-grade fibromyxoid sarcoma (LGFMS) is a rare type of sarcoma which is observed in the soft tissue of proximal extremities, typically in young and middle-aged adults. It consists of a solid proliferation of bland spindle cells within collagenous and myxoid stroma.

Case Report

Herein, we report a case of LGFMS with massive degeneration and hyalinization. A 30-year-old man presented with a well-circumscribed mass measuring 15 cm in diameter in his left biceps femoris muscle. Marginal tumor resection was performed under the clinical diagnosis of an ancient schwannoma or chronic expanding hematoma (CEH). The resected tissue revealed a well-demarcated tumor mass with massive degeneration and hyalinization with focal calcification. Proliferation of spindle tumor cells with abundant collagenous stroma, which resembled the fibrous capsule of CEH, was observed exclusively in a small area of the periphery of the tumor. No nuclear palisading, myxoid stroma, or collagen rosettes were identified. Immunohistochemical analysis demonstrated that the spindle tumor cells expressed mucin 4 and epithelial membrane antigen. Reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction analysis detected mRNA expression of fused in sarcoma::CAMP-responsive element binding protein 3-like protein 2 (FUS::CREB3L2) fusion gene. Thus, a final diagnosis of LGFMS with massive degeneration and FUS::CREB3L2 fusion was made.

Conclusion

The recognition of massive degeneration and hyalinization as unusual features of LGFMS might be helpful to differentiate it from CEH and other benign spindle-cell tumors.

Keywords: Low-grade fibromyxoid sarcoma, massive necrosis, MUC4, FUS::CREB3L2 fusion

Low-grade fibromyxoid sarcoma (LGFMS) is a rare type of sarcoma which commonly arises in the deep soft tissue of proximal extremities or trunk of middle-aged patients (1,2). Most cases of LGFMS present as a painless and slow-growing well-circumscribed mass, with a diameter from 1 to 23 cm, and comprise fibrous and myxoid areas (1-4). The tumor typically exhibits an aggressive clinical behavior and high rates of recurrence, distal metastasis and mortality during long-term follow-up (3,4). Histologically, LGFMS exhibits a proliferation of bland spindle cells arranged in short fascicles or a whorled growth pattern within collagenous and myxoid stroma (1-3). The neoplasm also often exhibits giant collagen rosette formations, which are one of its diagnostic histological features (1,5). A subset of LGFMS presents cystic degeneration and heterotopic ossification (3,5-7); however, tumor necrosis is rarely described (8). In immunohistochemical (IHC) analysis, cytoplasmic mucin 4 (MUC4) expression in tumor cells is highly sensitive for the diagnosis of LGFMS, and focal positivity for smooth muscle actin, desmin, and CD34 are additional findings (9). Most LGFMSs harbor gene rearrangements for the generation of fused in sarcoma::CAMP-responsive element binding protein 3-like protein 2 (FUS::CREB3L2 or FUS::CREB3L1) fusion genes (10). Reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction assays using formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded tumor tissue specimens are available for the detection of the characteristic fusion genes (11).

Herein, we report a case of LGFMS with massive degenerative and hyalinized necrosis in the left biceps femoris muscle, which was difficult to differentiate from chronic expanding hematoma (CEH) and other benign spindle-cell tumors.

Case Report

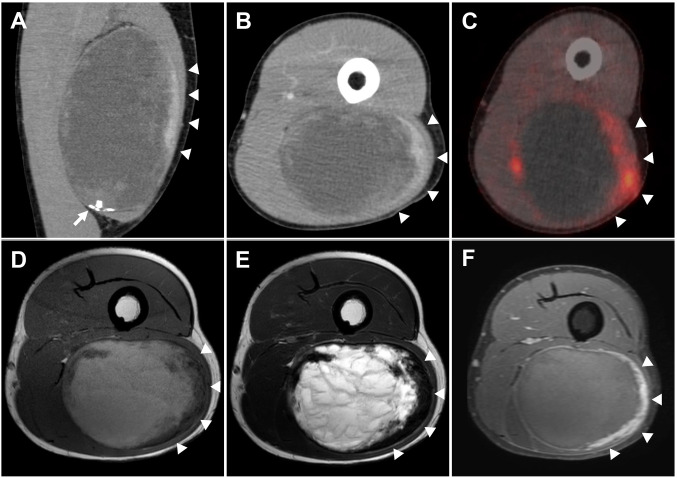

Clinical summary. A 30-year-old man presented with a painless, slow-growing mass in the left thigh that had been present for 7 years. He had no history of local trauma. Computed tomography revealed a well-circumscribed hematoma-like mass of 16×9×6 cm in the left biceps femoris muscle, with focal calcification (Figure 1A). A peripheral solid area exhibited moderate contrast enhancement (Figure 1A and B, arrowheads), and 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron-emission tomography/computed tomography showed increased fluorodeoxyglucose uptake in the area (standard uptake value maximum=4.49) (Figure 1C, arrowheads). On magnetic resonance imaging, the central area of the tumor exhibited high intensity in T1-weighted (T1WI) and T2-weighted (T2WI) images; the peripheral area showed low intensity on T1WI and T2WI and mild enhancement on post-contrast T1WI (Figure 1D-F, respectively, arrowheads). The diagnostic imaging suggested ancient schwannoma with cystic change or CEH with peripheral fibrous capsule. Marginal resection was performed for the differential diagnosis and treatment. Six months postoperatively, no local recurrence or remote metastasis was observed.

Figure 1. Diagnostic imaging. Coronal (A) and axial (B) contrast-enhanced computed tomography of the tumor revealed low density in most areas, suggesting cystic degeneration or a hematoma. The peripheral area showed mild contrast enhancement (arrowheads) and calcification (arrow). 18F-Fluorodeoxyglucose positron-emission tomography/computed tomography showed an increased uptake in the peripheral area (arrowheads). On T1-weighted (D) and T2-weighted (E) magnetic resonance imaging, the central area of the tumor exhibited high intensity, while the peripheral area (arrowheads) showed low intensity. On post-contrast T1-weighted magnetic resonance imaging (F), the peripheral area demonstrated moderate contrast enhancement (arrowheads), indicating a cellular area of a fibrous capsule or tumor proliferation.

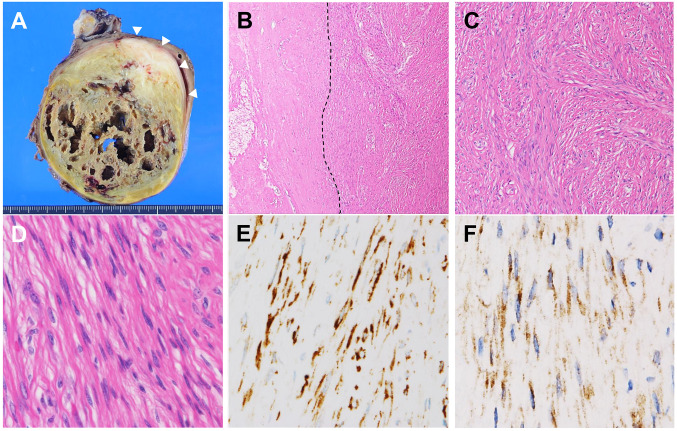

Pathological findings. The resected mass was fixed in 10% phosphate-buffered neutral formalin, processed routinely for paraffin-embedded tissue sections, stained with hematoxylin and eosin, and used for IHC. Macroscopic examination revealed a yellowish-brown mass, measuring 15×10×8 cm, with cystic degeneration and a peripheral greyish-white area (Figure 2A, arrowheads). Histological examination identified massive degeneration and hyalinization (Figure 2B) with cholesterol clefts, aggregates of foamy macrophages, and focal calcification but no ossification. In the peripheral greyish-white area, spindle tumor cell proliferation was sparsely arranged in loose fascicles with an abundant collagenous stroma (Figure 2C). The spindle cells had bland nuclei and inconspicuous nucleoli, without nuclear palisading, marked pleomorphism, or frequent mitotic figures (Figure 2D). No myxoid stroma or giant collagen rosettes were detected, despite multiple sectioning and extensive histological observation. In IHC, the spindle cells were positive for MUC4 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Dallas, TX, USA) (Figure 2E) and epithelial membrane antigen (EMA; Leica Biosystems, Nussloch GmbH, Nuβloch, Germany) (Figure 2F); however, they were negative for α-smooth muscle actin (Leica Biosystems), desmin (Leica Biosystems), CD34 (DAKO, Santa Clara, CA, USA), S-100 protein (Leica Biosystems), SRY-box transcription factor 10 (SOX10; Nichirei, Tokyo, Japan), and β-catenin (Leica Biosystems).

Figure 2. Macroscopic and microscopic tumor findings. A: Macroscopic examination of the resected tumor, showing a yellow-brown cyst-like cavitation area and peripheral greyish-white solid area (arrowheads). B: Histological examination with a low-power scanning view of the areas of massive necrosis and hyalinization (left side of the dashed line) [hematoxylin and eosin (HE), 40×]. C: Medium-power view of the tumor periphery, showing a fascicular proliferation of spindle cells with collagenous stroma. (HE, 100×). D: High-power view of the tumor, showing spindle cells with bland-looking nuclei and inconspicuous nucleoli. No myxoid stroma or collagen rosettes were observed. (HE, 400×). Immunohistochemical study revealed that spindle cells were positive for mucin 4 (E) and epithelial membrane antigen (F). (400×).

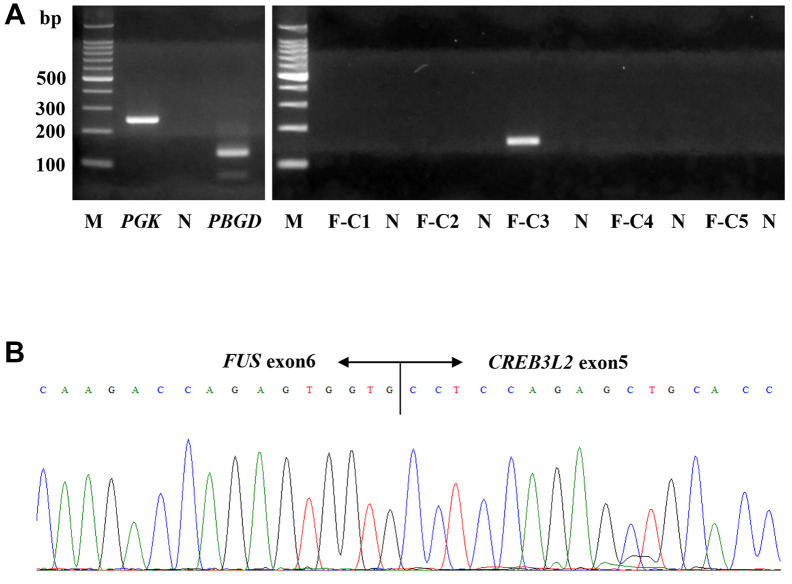

Molecular analysis. Reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction using mRNAs extracted from the formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded tissues (11) detected the FUS::CREB3L2 fusion gene, which was confirmed by Sanger sequencing (Figure 3A and B). Therefore, the final histological and molecular diagnosis was of LGFMS with massive necrosis and a FUS::CREB3L2 fusion.

Figure 3. Reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction analysis for the detection of fused in sarcoma–CAMP-responsive element binding protein 3-like protein 2 (FUS::CREB3L2) fusion gene. A: Reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction using mRNAs extracted from formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded tumor tissue. Using F-C3 primers, a specific PCR product (149 bp) of FUS::CREB3L2 fusion gene was detected. F-C5 primers for FUS::CREB3L1 did not amplify any genes. B: Sanger sequencing of the PCR product revealed a fusion point generating FUS::CREB3L2 fusion, in exon 6 of FUS and exon 5 of CREB3L2. F-C1, -2, -3, -4: FUS::CREB3L2 primers (F-C3: 149 bp); F-C5: FUS::CREB3L1 primer; M: molecular size marker; N: negative control (distilled water); PBGD: porphobilinogen deaminase (127 bp); PGK: phosphoglycerate kinase (247 bp).

Discussion

We present a rare case of LGFMS with massive degenerative and hyalinized necrosis but no typical myxoid stroma or collagen rosette formation. Retrospectively, the age of the patient, anatomic location, and clinical findings of the mass are compatible with a diagnosis of LGFMS (1-3). However, the unusual massive degeneration and subsequent paucity of viable tumor cells resulted in a difficult differential diagnosis by imaging and histological examination. Combined IHC and molecular assessments are essential for the diagnosis of such unusual cases of LGFMS.

In the present case, the histological differential diagnosis included CEH, ancient schwannoma, desmoid fibromatosis, and leiomyoma of deep soft tissue. CEH is a slow-growing non-neoplastic hypocellular lesion in which the trauma history of the patient is not always clear (12). Identification of an old central hematoma and a hypocellular fibrous capsule with granulation tissue, chronic inflammation and hemosiderin deposition is helpful in the diagnosis of CEH (13,14). Ancient schwannomas exhibit diffuse hypocellular areas, with stromal and vascular wall hyalinization, cystic degeneration, and calcification; nuclear palisading and nuclear pleomorphism, so-called degenerative atypia, are characteristic features that are not observed in LGFMS (15). Schwannoma cells typically are diffusely positive for S-100 protein and SOX10 (15,16). Another important differential diagnosis is desmoid fibromatosis, in which proliferation of bland spindle cells with abundant collagenous stoma resembles that in the present case; however, desmoid fibromatosis usually does not exhibit massive necrosis. IHC analysis of nuclear β-catenin expression is useful for differential diagnosis (17). Leiomyomas of deep soft tissue are even less frequently encountered and are commonly located in the lower and upper extremities, in which degenerative cystic changes, hyalinization, and calcification occur (18,19). As leiomyoma cells typically have cigar-shaped nuclei and are almost always positive for α-smooth muscle actin and desmin (18), it would not be difficult to differentiate them from LGFMS.

Some LGFMS cases with central necrosis or cystic change have been reported (20-23). In the case of a 77-year-old man who presented with LGFMS, arising in the deep soft tissue of the buttock, a necrotic area that was limited to the central and spindle tumor cell-proliferating area, showing myxoid stroma was reported. It was better preserved than in the present case (20). Tumor necrosis might result from a long duration of tumor development (20). Other LGFMS cases with cystic changes have often been reported in superficial locations, but solid areas exhibit typical histological findings for LGFMS (21-23). Among these cases, one with a tumor uncommonly located in the cheek presented cystic changes and osseous metaplasia (22). Although the pathogenesis and biological significance of massive necrosis and subsequent cystic changes and hyalinization in LGFMS remain unknown, awareness of such unusual pathological features as an uncommon histological presentation is required for the differential diagnosis of LGFMS.

Conclusion

LGFMS should be included in differential diagnosis in the case of deep soft-tissue tumors with spindle-cell proliferation and massive degeneration with hyalinization, even if viable tumor cells occupy only a small area and do not exhibit typical myxoid stroma and giant collagen rosettes. In particular, MUC4 and EMA IHC with specific fusion gene detection is necessary for a definite diagnosis of LGFMS exhibiting unusual features.

Conflicts of Interest

The Authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Authors’ Contributions

Takashi Tasaki and Akihide Tanimoto made the final pathological diagnosis; Mari Kirishima, Hirotsugu Noguchi, and Ikumi Kitazono summarized the pathological data; Eisuke Shiba and Masanori Hisaoka analyzed and interpreted the molecular data; Wataru Terabaru and Kazuhiro Tabata performed the immunohistochemical study; Naohiro Shinohara and Hiromi Sasaki summarized the clinical data; Masanori Nakajo and Masatoyo Nakajo summarized the clinical imaging data; Akihide Tanimoto organized the study and wrote the article. All Authors read and approved the final article.

Acknowledgements

The Authors greatly appreciate the excellent technical assistance of Ms. Kaori Iwakiri and Ms. Emi Kubota, Department of Surgical Pathology, Kagoshima University Hospital, and Orie Iwaya, Department of Pathology, Kagoshima University Graduate School of Medical and Dental Sciences.

References

- 1.Folpe AL, Lane KL, Paull G, Weiss SW. Low-grade fibromyxoid sarcoma and hyalinizing spindle cell tumor with giant rosettes. Am J Surg Pathol. 2000;24(10):1353–1360. doi: 10.1097/00000478-200010000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chamberlain F, Engelmann B, Al-Muderis O, Messiou C, Thway K, Miah A, Zaidi S, Constantinidou A, Benson C, Gennatas S, Jones RL. Low-grade fibromyxoid sarcoma: Treatment outcomes and efficacy of chemotherapy. In Vivo. 2020;34(1):239–245. doi: 10.21873/invivo.11766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Evans HL. Low-grade fibromyxoid sarcoma. Am J Surg Pathol. 2011;35(10):1450–1462. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e31822b3687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Maretty-Nielsen K, Baerentzen S, Keller J, Dyrop HB, Safwat A. Low-grade fibromyxoid sarcoma: Incidence, treatment strategy of metastases, and clinical significance of the FUS gene. Sarcoma. 2013;2013:256280. doi: 10.1155/2013/256280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hisaoka M, Matsuyama A, Aoki T, Sakamoto A, Yokoyama K. Low-grade fibromyxoid sarcoma with prominent giant rosettes and heterotopic ossification. Pathol Res Pract. 2012;208(9):557–560. doi: 10.1016/j.prp.2012.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lee AF, Yip S, Smith AC, Hayes MM, Nielsen TO, O’Connell JX. Low-grade fibromyxoid sarcoma of the perineum with heterotopic ossification: case report and review of the literature. Hum Pathol. 2011;42(11):1804–1809. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2011.01.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Serinelli S, Mookerjee GG, Stock H, De La Roza G, Damron T, Gitto L, Zaccarini DJ. Low-grade fibromyxoid sarcoma with heterotopic bone formation: Case report and review of the literature. Appl Immunohistochem Mol Morphol. 2022;30(9):640–646. doi: 10.1097/PAI.0000000000001059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Oda Y, Takahira T, Kawaguchi K, Yamamoto H, Tamiya S, Matsuda S, Tanaka K, Iwamoto Y, Tsuneyoshi M. Low-grade fibromyxoid sarcoma versus low-grade myxofibrosarcoma in the extremities and trunk. A comparison of clinicopathological and immunohistochemical features. Histopathology. 2004;45(1):29–38. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.2004.01886.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Doyle LA, Möller E, Dal Cin P, Fletcher CD, Mertens F, Hornick JL. MUC4 is a highly sensitive and specific marker for low-grade fibromyxoid sarcoma. Am J Surg Pathol. 2011;35(5):733–741. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e318210c268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mertens F, Fletcher CDM, Antonescu CR, Coindre JM, Colecchia M, Domanski HA, Downs-Kelly E, Fisher C, Goldblum JR, Guillou L, Reid R, Rosai J, Sciot R, Mandahl N, Panagopoulos I. Clinicopathologic and molecular genetic characterization of low-grade fibromyxoid sarcoma, and cloning of a novel FUS/CREB3L1 fusion gene. Lab Invest. 2005;85(3):408–415. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.3700230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Matsuyama A, Hisaoka M, Shimajiri S, Hayashi T, Imamura T, Ishida T, Fukunaga M, Fukuhara T, Minato H, Nakajima T, Yonezawa S, Kuroda M, Yamasaki F, Toyoshima S, Hashimoto H. Molecular detection of FUS-CREB3L2 fusion transcripts in low-grade fibromyxoid sarcoma using formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissue specimens. Am J Surg Pathol. 2006;30(9):1077–1084. doi: 10.1097/01.pas.0000209830.24230.1f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Negoro K, Uchida K, Yayama T, Kokubo Y, Baba H. Chronic expanding hematoma of the thigh. Joint Bone Spine. 2012;79(2):192–194. doi: 10.1016/j.jbspin.2011.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mentzel T, Goodlad JR, Smith MA, Fletcher CD. Ancient hematoma: A unifying concept for a post-traumatic lesion mimicking an aggressive soft-tissue neoplasm. Mod Pathol. 1997;10(4):334–340. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Aoki T, Nakata H, Watanabe H, Maeda H, Toyonaga T, Hashimoto H, Nakamura T. The radiological findings in chronic expanding hematoma. Skeletal Radiol. 1999;28(7):396–401. doi: 10.1007/s002560050536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Glodblum JR, Folpe AL, Weiss SW. Benign tumors of peripheral nerves. In: Enzinger’s & Weiss’s Soft Tissue Tumors Seventh Edition. Philadelphia, PA, USA, Elsevier. 2020:pp. 913–930. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Miettinen M. Immunohistochemistry of soft tissue tumours - review with emphasis on 10 markers. Histopathology. 2014;64(1):101–118. doi: 10.1111/his.12298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ng TL, Gown AM, Barry TS, Cheang MCU, Chan AKW, Turbin DA, Hsu FD, West RB, Nielsen TO. Nuclear beta-catenin in mesenchymal tumors. Mod Pathol. 2005;18(1):68–74. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.3800272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McCarthy AJ, Chetty R. Benign smooth muscle tumors (leiomyomas) of deep somatic soft tissue. Sarcoma. 2018;2018:2071394. doi: 10.1155/2018/2071394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Billings SD, Folpe AL, Weiss SW. Do leiomyomas of deep soft tissue exist. Am J Surg Pathol. 2001;25(9):1134–1142. doi: 10.1097/00000478-200109000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kurisaki-Arakawa A, Akaike K, Tomomasa R, Arakawa A, Suehara Y, Takagi T, Kaneko K, Yao T, Saito T. A case of low-grade fibromyxoid sarcoma with unusual central necrosis in a 77-year-old man confirmed by FUS-CREB3L2 gene fusion. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2014;5(12):1123–1127. doi: 10.1016/j.ijscr.2014.09.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Brasanac D, Dzelatovic NS, Stojanovic M. Giant cystic superficial low-grade fibromyxoid sarcoma. Ann Diagn Pathol. 2013;17(2):222–225. doi: 10.1016/j.anndiagpath.2011.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.He KF, Jia J, Zhao YF. Low-grade fibromyxoid sarcoma with cystic appearance and osseous metaplasia in the cheek: a case report and review of the literature. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2013;71(6):1143–1150. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2012.12.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sahraoui G, Sassi F, Charfi L, Ghallab M, Mrad K, Doghri R. Low-grade fibromyxoid sarcoma of the vulva presenting as a cystic mass: A case report and review of literature. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2022;100:107736. doi: 10.1016/j.ijscr.2022.107736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]