TCC and Ki (Qi)

Visitors to China from the West (and also from Japan) are impressed in the early morning when they first wake up in their hotels to see many Chinese people quietly and beautifully performing Tai Chi Chuan (TCC: Tai-kyoku-ken, in Japanese, and, incidentally, Tai Chi Chih® is a registered trademark of a school of TCC) in the park just next to their hotels. Also it is now not unusual to see TCC practised by Westerners in New York or London these days. We remember that we were quite amused to see in the film Star Wars a somewhat caricatured version of martial arts probably related to TCC shown off in a ‘Western’ way.

Although it seems difficult to ‘define’ what TCC is, given its broad range from health exercise to martial art, it would be pertinent to say that its essential components are meditation, breathing and slow body movement. We usually understand it as a mode of Qigong (Ki-kou, in Japanese), which may be roughly translated into ‘effectuation of Qi (Ki, in Japanese)’ in English. Qigong as applied to health practice can be divided into ‘external’ and ‘internal’ facets. In the former mode, Ki external to a subject is transferred into the subject mediated by an outside ‘master’ Ki practitioner. In the latter mode, a subject carries out sequences of practices by him/herself to enhance (or effectuate) his/her own Ki.

It has now become clichéd among people interested in complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) that the modern analytical medicine should be transformed or evolved into more ‘holistic’ medicine. Many people will agree that one of the keys to this ‘holistic’ approach is mind/body integrity. The concept of Ki would be of great value towards this direction, as it is understood as a kind of ‘energy’ of mind/body as a whole. If, therefore, there was some concrete method to enhance (strengthen) Ki, it would become one of the cornerstones of holistic medicine of the future. Scientific study of Qigong is warranted from this perspective, and thus Irwin's review ‘Shingles Immunity and Health Functioning in the Elderly: Tai Chi Chih as a Behavioral Treatment’ in eCAM (1) is a timely one.

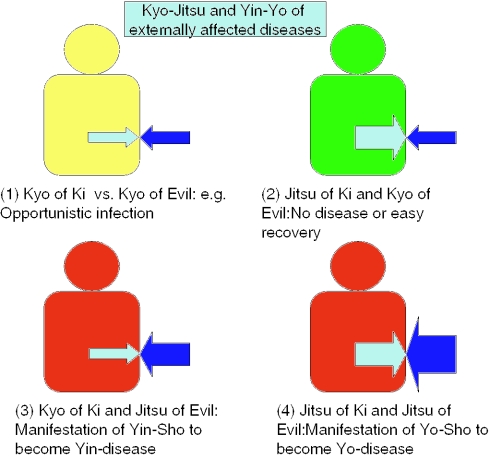

The basic principle of Qigong as a ‘health’ practice, we believe, is the assumption that if Ki is ‘depressed (or vacant)’, illness (evil) will develop (‘illness out of hollowed Ki’). This kind of understanding will be better illustrated by using the concepts of Yin/Yo (Yin–Yang, in Chinese: or maybe ‘overt/covert’ in this case) and Kyo/Jitsu (Xu-Shi, in Chinese: or maybe ‘hollow/full’ in this case) (2) as seen in Fig. 1. According to this scheme, a subject's Ki is either Kyo (hollow) or Jitsu (full), while external evil's potency is also Kyo (hollow) or Jitsu (full). When a subject's Ki is Kyo, even an external evil with Kyo potency will cause disease. A typical example of such a situation would be opportunistic infection in immunocompromised patients. On the other hand, when a subject's Ki is Jitsu but the potency of an external evil is Kyo, the subject will overcome the evil. When a subject's Ki is Kyo but the potency of an external evil is Jitsu, in contrast, the evil will overcome the resistance of the subject and the subject will become ill. This kind of situation is the Yin condition of the disease, such as advanced cancer in old people. When both a subject's Ki and the potency of an external evil are both Jitsu, there will emerge a Yo condition of disease, such as febrile chicken pox in young children. Thus, from the medical point of view, Ki can be seen as the totality of the body's healing systems or defense mechanisms which include the immune system as their essential part.

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of the Kyo (hollowness)/Jitsu (fullness) and Yin (negativity)/Yo (positivity) view of development of ‘externally affected’ diseases. In Kampo and Chinese Traditional Medicine, development of diseases that are caused by external ‘evils’ is interpreted in terms of their antagonistic balance with Ki. For example, if both Ki and evil are weak (Kyo), conditions such as opportunistic infection will develop (1). If Ki is strong while evil is weak, no disease will develop (2). If Ki is weak and evil is strong, the subject yields to the evil, and Yin (negative) Sho will develop (3). Finally, if both Ki and evil are strong, Yo (positive, or fulminant) disease conditions (Sho) will develop (4).

TCC Against Diseases?

There have been several reports (3–5) and reviews (6) showing that TCC enhances immune functions. However, a recent systematic review by Wang et al. (7) concludes that well-designed studies remain to be conducted in the future, as the data presented up to now have many limitations and biases. Irwin showed in his review in eCAM (1) and several previous articles (8,9) that TCC, which is supposed to support the Jitsu condition for Ki, induced proliferation of CD4+ and CD45RO+ T-lymphocytes against varicella zoster virus (VZV) in those who practise it. This is a fine piece of data obtained by a well-designed method, directed towards one of the general ideas above, namely enhanced Ki will overcome an external Kyo evil. It should be noted, however, that their data do not show that those who practice TCC are less likely to be afflicted by shingles, or much less that TCC will cure it. His view is also very interesting for us, who have long tried to integrate Kampo and other CAM modalities into our clinical practices as dermatologists (10,11).

Shingles is a very interesting disease condition, as it is caused by secondary reactivation of VZV many decades after its actual infection, well known as chicken pox. This reactivation process is intriguing, but it is already known that many factors could contribute to it, including overwork, stress, trauma, malignancy, autoimmune diseases, grave infections, use of immunosuppressive agents and radiation. These various factors may lead to depressed immune functions which will eventually allow reactivation of VZV. We dermatologists are usually more likely to be visited by patients who are already affected by shingles, even in severe states. In those cases, our first choice is antiviral agents, which would directly ‘kill’ the ‘external evils’, in this case VZV. Even steroids, which are in principle regarded as ‘immunosuppressive’ agents, are being revalued these days for fulminant cases. On the other hand, however, we often use Kampo medicine such as Hochu-Ekki-To (Bu-zhong-yi-qi-tang in Chinese) for patients with shingles in order to enhance their Ki, as it is one of the typical formulae in Kampo which is prescribed for people with the Sho of Ki-Kyo (Qi-Xu, in Chinese) or ‘hollowed (deficient) Ki’ conditions (12–14). It would be of great interest to examine if treatment of shingles by Hochu-Ekki-To is also associated with the proliferation of T cells against VZV.

Irwin's study, on the other hand, focuses on the aspect of prevention. Especially interesting is his study design where subjects selected are those older ones at higher risk of shingles. Also we appreciate his study design of having control subjects on the waiting list from the ethical point of view, Since not participating in an exercise program as mild as TCC would certainly not do anyone harm. This kind of design should be considered in assessment of other CAM modalities as well, for example, Kampo. At the epidemiological level, however, as Irwin himself admits, it would be rather difficult to confirm if the increase of anti-VZV T cells by TCC will in fact decrease the incidence of shingles, as the incidence itself is quite low. However, if the question to be answered is not whether immunity to certain specific ‘evils’ is enhanced by TCC but whether its practice will enhance Ki to reduce the chance of various external evils harming the subject, say, influenza, epidemiological studies on a large cohort should give an interesting answer. I hope our colleagues in China will carry out such a prospective study with scientific rigor.

Methodological Challenge

One of the pitfalls in the study on Ki is obviously that there seems to be no ‘scientific’ objective measure to evaluate its ‘quantity’. As an American psychiatrist, Irwin keeps this problem at bay by taking a ‘behaviorist’ approach, asking not whether Ki enhanced immune functions but just whether immune cells against VZV were increased in those who ‘performed’ TCC. Indeed, he tried not to make any references to Ki in his review. Instead, he presented SF-36 scores, related to quality of life (QOL), of those who did or did not practise TCC. He verified the effects of TCC in improving the scores, especially in those older adults whose baseline scores were at or below the population norm. He proposes as a hypothesis to explain these effects that either relaxation or exercise, or both, may mediate the observed changes in immunity and health outcome, suggesting the sympathetic/parasympathetic balance as a basic mechanism for their influence. We are tempted to ask at this point if it is not possible to call ‘Ki’ something, which is influenced by relaxation and/or exercise, related to QOL, and based at least partly on the ‘sympathetic/parasympathetic balance’. This may be a nice way to introduce the ‘holistic’ concept of Ki into ‘analytical’ Western medicine.

The merit of the Ki concept would be well understood if compared with the related English term such as ‘spirit’ or ‘vitality/vigor’. In the dualistic tradition of Western culture, spirit is understood as something non-physical or tangible, so it is essentially not influenced by one's physical condition: a person can be ‘high-spirited’ even if he is fatally ill. On the other hand, vitality/vigor is understood as something more related to one's physical condition, so one would not be seen as ‘more vigorous’ if quietly meditating. There seems to be no good term to represent the ‘mind–body balance’ condition, like Ki, in English. One way to illustrate Ki as a ‘mind–body’ concept is to point out that the word Ki is probably related to ‘breathing’ (and therefore of course ‘air’). Indeed, it should be borne in mind that the crucial component of TCC is breathing. By breathing deeply, one can feel that they are really living, and in deep breathing a practitioner of TCC is suggested to unite concentration of mind and relaxation of body.

As Asian clinicians, though, we would not like to ‘mystify’ the concept of Ki and also the practise of TCC so much. Ki could well be roughly regarded as a shorthand sign to represent ‘mind–body QOL’ and we have no doubt that several modes of exercise practised even in the West have many things in common with TCC in enhancing Ki. In fact, we have recommended to our Japanese patients not only TCC but stretching, swimming or even household work, for enhancement of Ki. In his study on laughter comparing rheumatoid arthritis patients and healthy people, Yoshino (15,16) reported that several ‘stress’ measures such as serum cortisol, interleukin-6 (IL-6) and adrenaline levels are decreased in patients who laughed, and the natural killer (NK) cell activity was increased both in patients and in healthy subjects who laughed of ten. We suggest that laughter would be for some subjects as effective as TCC in enhancing Ki.

Thus, the concept of Ki would be as important and effective, and also as difficult to quantify, as the concept of ‘stress’. However, if the concept of ‘stress’ can have citizenship in modern medicine, as we think is the case, why not the concept of Ki, which may be understood as something which could be the target of stress? The concept of Ki is so rich as to encompass such wide characterizations of its disturbance as Ki–Kyo (hollowed Ki), Ki–Gyaku (back streamed Ki) and Ki–Utsu (stagnant-Ki) (12). The usual concept of stress is probably related to the latter two Ki states, while the first would be understood as the condition where a person has yielded to stress. We should like to point out that as the research into ‘stress’ has suffered from the absence of ‘objective’ measures which could be called ‘stress indices (or stress coefficient, SQ?)’, difficulty in quantifying Ki and its derangement is not related to its cultural (Asian) worldview. It is the difficulty of introducing any holistic or ‘qualia’-like concepts into the modern Western methodology of science.

Subjective or Objective

It would therefore be tempting for a Western psychiatrist such as Irwin to approach this problem from a behavioristic point of view and try to represent a subject's Ki (or stress) state in such terms as the SF-36. Especially interesting is the possibility of relating Ki to those SF-36 scores such as General Health Perception and Vitality. We are sure that SF-36 would help us obtain useful data without which no large-scale comparative trials would be possible. However, we must express serious reservations concerning this approach, not because it tries to quantify something ‘subjective’, or what cannot in principle be quantified. As long as its limitation is realized, such an attempt of objectively representing ‘subjective’ qualities has actually advanced, not hampered, the progress of scientific study of the mind. What we would like to point out is that such a questionnaire method has limitations, because it takes a subject's verbal reactions to written questions at face value. In addition to, of course, the problem of conscious lying, questionnaire methods are not well guarded against the problem of a subject's unconscious self-deception. This point is especially important in assessing many CAM modalities in which some practitioners offer ‘magical’ healing power. For example, nowadays we encounter a lot of ‘external’ Qigong ‘masters’ who boast they can heal many patients' diseases by transmitting their special Ki energy. I am afraid that there are not just a few people who could be deceived by such gurus into responding to questionnaires in such a way that their SF-36 scores would appear to have dramatically improved.

Ki can be Approached ‘Objectively’

We would like to remind readers of the very merit of the concept of Ki, that it is the concept of the state of the mind/body as a whole. It is thus not a ‘subjective’ state, which can only be known introspectively. From our clinical experience, the ‘Ki–Kyo’ state is diagnosed very ‘objectively’: those with ‘Ki–Kyo’ are weak in voice, have no ‘strength’ in their eyes and their posture is poor. We do not think anyone can pretend to be in good Ki condition, even if they can pretend to have high SF-36 scores on the paper questionnaire. In this sense, Ki is a very objective entity. It is not an abstract and subjective entity like soul or spirit. As experienced dermatologists, we would also like to point out that we can judge a patient's Ki state by just glancing at their skin condition. Those people healthy in mind–body, or with good Ki, have bright and ‘full’ skin. Though difficult to quantify, these are ‘objective’ and non-verbal properties, unlike subjective states of expressed verbally by the subject in response to a written questionnaire. There is thus a definite possibility that we can elaborate on the concept of Ki as an objective ‘scientific’ term.

It is a basic East Asian ‘philosophy’ of health/disease that those with a good Ki state are highly immune to diseases. It is very nice to see that Western clinical researchers such as Irwin have undertaken the challenge to tackle this difficult problem of Ki, or mind–body unity. Now is an exciting era, when for the first time it has became possible for a western psychiatrist and an Eastern dermatologist to work together towards reconciling this fundamental difference between the medicines of the East and the West.

References

- 1.Irwin M, Pike J, Oxman M. Shingles immunity and health functioning in the elderly: Tai Chi Chih as a behavioral treatment. eCAM. 2004;1:223–32. doi: 10.1093/ecam/neh048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yamamoto I. A personal view on Sho. Med Kanpo. 1993;12:11–21. (in Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sun X, Xu Y, Xia Y. Determination of E-rosette-forming lymphocytes in aged subjects with Taichiquan exercise. Int Sports Med. 1989;10:217–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhang GD. The impact of 48-form Tai Chi Chuan and Yi Qi Yang Fei Gong on the serum levels of IgG, IgM, IgA and IgE in human. J Beijing Inst Phys Educ. 1990;4:12–4. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Li ZQ, Shen Q. The impacts of the performance of Wu's Tai Chi Chuan on the activity of natural killer cells in peripheral blood in the elderly. Chin J Sports Med. 1995;14:53–6. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Li JX, Hong Y, Chan KM. Tai Chi: physiological characteristics and beneficial effects on health. Br J Sports Med. 2001;35:148–56. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.35.3.148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wang C, Collet JP, Lau J. The effect of Tai Chi on health outcomes in patients with chronic conditions: a systematic review. Arch Intern Med. 2004;164:493–501. doi: 10.1001/archinte.164.5.493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Irwin M, Costlow C, Williams H, Artin KH, Chan CY, Stinson DL, Levin MJ, Hayward AR, Oxman MN. Cellular immunity to varicella-zoster virus in patients with major depression. J Infect Dis. 1998;178(Suppl 1):S104–8. doi: 10.1086/514272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Irwin MR, Pike JL, Cole JC, Oxman MN. Effects of a behavioral intervention, Tai Chi Chih, on varicella-zoster virus specific immunity and health functioning in older adults. Psychosom Med. 2003;65:824–30. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000088591.86103.8f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kobayashi H, Takahashi K, Mizuno N, Kutsuna H, Ishii M. An alternative approach to atopic dermatitis: part I—case series presentation. eCAM. 2004;1:49–62. doi: 10.1093/ecam/neh015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kobayashi H, Takahashi K, Mizuno N, Kutsuna H, Ishii M. An alternative approach to atopic dermatitis: part II—summary of cases and discussion. eCAM. 2004;1:145–55. doi: 10.1093/ecam/neh026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Terasawa K. Evidence-based reconstruction of Kampo medicine: part II—the concept of Sho. eCAM. 2004;1:119–23. doi: 10.1093/ecam/neh022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Li XY, Takimoto H, Miura S, Yoshikai Y, Matsuzaki G, Nomoto K. Effect of a traditional Chinese medicine, Bu-zhong-yi-qi-tang (Japanese name: Hochu-ekki-to) on the protection against Listeria monocytogenes infection in mice. Immunopharmacol Immunotoxicol. 1997;14:383–402. doi: 10.3109/08923979209005400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kawakita T, Nomoto K. Immunopharmacological effects of Hochu-ekki-to and its clinical application. Prog Med. 1998;18:801–7. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yoshino S, Fujimori J, Kohda M. Effects of mirthful laughter on neuroendocrine and immune systems in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheumatol. 1996;23:793–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nakajima A, Hirai H, Yoshino S. Reassessment of mirthful laughter in rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheumatol. 1999;26:512–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]