Abstract

Despite advances in the nutritional support of low birth weight and early-weaned piglets, most experience reduced extrauterine growth performance. To further optimize nutritional support and develop targeted intervention strategies, the mechanisms that regulate the anabolic response to nutrition must be fully understood. Knowledge gained in these studies represents a valuable intersection of agriculture and biomedical research, as low birth weight and early-weaned piglets face many of the same morbidities as preterm and low birth weight infants, including extrauterine growth faltering and reduced lean growth. While the reasons for poor growth performance are multifaceted, recent studies have increased our understanding of the role of nutrition in the regulation of skeletal muscle growth in the piglet. The purpose of this review is to summarize the published literature surrounding advances in the current understanding of the anabolic signaling that occurs after a meal and how this response is developmentally regulated in the neonatal pig. It will focus on the regulation of protein synthesis, and especially the upstream and downstream effectors surrounding the master protein kinase, mechanistic target of rapamycin complex 1 (mTORC1) that controls translation initiation. It also will examine the regulatory pathways associated with the postprandial anabolic agents, insulin and specific amino acids, that are upstream of mTORC1 and lead to its activation. Lastly, the integration of upstream signaling cascades by mTORC1 leading to the activation of translation initiation factors that regulate protein synthesis will be discussed. This review concludes that anabolic signaling cascades are stimulated by both insulin and amino acids, especially leucine, through separate pathways upstream of mTORC1, and that these stimulatory pathways result in mTORC1 activation and subsequent activation of downstream effectors that regulate translation initiation Additionally, it is concluded that this anabolic response is unique to the skeletal muscle of the neonate, resulting from increased sensitivity to the rise in both insulin and amino acid after a meal. However, this response is dampened in skeletal muscle of the low birth weight pig, indicative of anabolic resistance. Elucidation of the pathways and regulatory mechanisms surrounding protein synthesis and lean growth allow for the development of potential targeted therapeutics and intervention strategies both in livestock production and neonatal care.

Keywords: Amino acids, Insulin, Mechanistic target of rapamycin, Pig, Protein synthesis

Introduction

Two common issues faced by the swine industry each year are pigs born of a low birth weight (piglets with a birth weight in the bottom 10% in a litter) (Riddersholm et al., 2021; Wu, 2018) and failure of piglets to thrive in early weaning scenarios (Valentim et al., 2021). Low birth weight in piglets is largely due to the genetic pressures of increasing hyperprolific sows (Riddersholm et al., 2021; Wu, 2018), while early weaning is typically done in response to market pressures from the highly vertically integrated pork market (Valentim et al., 2021). Nevertheless, both represent considerable issues facing the growth of neonatal pigs. Low birth weight, alone, represents a considerable loss to the swine industry each year (Wu et al., 2006). This is due to multiple factors including piglet losses at birth from discarded low birth weight animals, and indirect profit loss from wasted resources related to sow breeding and care (Wu et al., 2006; Mota-Rojas et al., 2011). Early weaning is done with the goal of decreasing the time between farrowing and rebreeding, leading to increased annual sow productivity (Valentim et al., 2021). However, young piglets have a decreased ability to digest grain due to enzyme activity in the gut that favors milk digestion and will only gradually adapt to digest other carbohydrates and protein approaching D42 of age (Engelsmann et al., 2022; Wei et al., 2021; Santos et al., 2018). This can lead to reduced digestibility and enteric disorders, similar to those seen in preterm and low birth weight human infants (Gomez et al., 2015). Therefore, the neonatal piglet model represents a valuable “dual purpose for dual benefits” model that has the potential to provide valuable findings in both animal agriculture and medicine.

Despite recent, modest reductions in the percentage of children affected, low birth weight remains the second highest cause of infant mortality in the United States (Mathews and Driscoll, 2017). Low birth weight in humans is defined as a birth weight of less than 2 500 g, per the World Health Organization, and in piglets is defined as the bottom 10% of litter birth weight. The majority of low birth weight infants are also born preterm (Alexander, 2007). Worldwide each year, approximately 15 million infants are born preterm, including over 10% of babies in the U.S. (Narwal et al., 2012), and this represents a significant healthcare concern (McIntire et al., 1999; March of Dimes, 2022).

Along with the increased risk of neonatal and postneonatal death, low birth weight piglets and infants are at increased risk for short-term adverse health outcomes such as respiratory distress, sepsis, decreased digestibility in the gut, and necrotizing enterocolitis, sometimes associated with parenteral feeding in low birth weight human infants, a necessary component of preterm infant management (Goldenberg and Culhane, 2007; Sondheimer et al., 1998; Kao et al., 2006). Extrauterine growth restriction is also a commonality between low birth weight piglets and infants, with growth curves faltering early in neonatal life and leading to decreased linear growth and an increased fat-to-lean mass body mass ratio, which likely contributes to an increased risk of undesirable carcass yields (“fatty carcass”) in low birth weight piglets, and obesity and related metabolic disease in low birth weight infants (Johnson et al., 2012; Markopoulou et al., 2019). This underscores the importance of meeting neonatal protein requirements and understanding the nutritional regulation of muscle growth in the neonate, especially those born low birth weight.

However, to develop effective therapies to optimize the nutritional management and growth of low birth weight piglets and infants, the nutritional mechanisms regulating perinatal growth must be firmly established. Growth and protein turnover rates are higher during the neonatal period than in any other period of postnatal or adult life (Davis et al., 1989). This high growth rate is largely attributable to the high rate of protein synthesis in skeletal muscle (Davis and Fiorotto, 2009; Suryawan et al., 2007). We have shown that this high rate of protein synthesis in muscle of the neonate is driven by the high ribosomal abundance and the ability to accelerate protein synthesis after a meal. This response to feeding in muscle is regulated independently by the postprandial increase in insulin and amino acids that activate nutrient signaling cascades (Wilson et al., 2009; El-Kadi et al., 2012; Suryawan et al., 2009) that increase activation of mechanistic target of rapamycin complex 1 (mTORC1), the master regulator of translation initiation (Davis and Fiorotto, 2009). However, low birth weight neonates often fall behind established extrauterine growth curves (Zhang et al., 2021; Bhatia, 2013), indicating a potential dysregulation in the activation of translation initiation.

Studies in the low birth weight piglet suggest that this extrauterine growth restriction is due to a reduced response to the feeding-induced stimulation of protein synthesis (Naberhuis et al., 2019). This reduced anabolic response results from the resistance of both the insulin and amino acid anabolic signaling pathways that regulate mTORC1-dependent translation initiation (Rudar et al., 2021a). Understanding these complex nutrient signaling pathways, how they impact the overall growth of the neonate, and the physiological differences that occur due to developmental regulation are vital to the development of new strategies to optimize the nutritional management of at-risk piglets and infants and promote their lean growth.

Role of nutrient intake in neonatal growth regulation

Feeding increases protein synthesis in neonatal skeletal muscle and this response is developmentally regulated

During the neonatal period, neonates undergo rapid growth. While all body tissues contribute to this rapid increase in mass, skeletal muscle tissue is the primary driver, in addition to being the most sensitive to nutrient deficiencies during this critical period in terms of meeting growth potential. For example, in neonatal rats, skeletal muscle tissue increases from 30% of total body protein at birth to 45% of total body protein at weaning (D28) (Davis and Fiorotto, 2009). Supporting this period of early muscle growth through a sufficient supply of nutrients, including amino acids, is vital for maximizing swine growth performance and productivity.

Skeletal muscle protein deposition occurs when the rate of protein synthesis exceeds the rate of protein degradation (Rudar et al., 2019; Reeds et al., 1980). Following ingestion of a meal, plasma levels of amino acids and glucose sharply increase, resulting in increased circulating levels of amino acids and insulin (in response to increased glucose levels). We have previously shown that feeding profoundly stimulates muscle protein synthesis in the neonatal pig and that this postmeal response decreases with age, noticeably diminishing even over the first 28 days of life (Suryawan and Davis, 2018; Suryawan et al., 2007; Davis et al., 1996), and further decreases through the postnatal period and into adulthood (Markofski et al., 2015; Paddon-Jones and Rasmussen, 2009; Volpi et al., 2000). To determine the metabolic mechanisms underlying this response, we developed a modified pancreatic-substrate clamp method which allows precise control of not only insulin and glucose (DeFronzo et al., 1979) but also amino acids (Davis et al., 1998) so that the independent effects of both insulin and amino acids could be identified using hyperinsulinemic-euaminoaci demic-euglycemic, euinsulinemic-hyperaminoacidemic-euglyc miec, and euinsulinemic-euaminoacidemic-euglycemic clamps. The results showed that the stimulation of protein synthesis by both insulin and amino acids is unique to skeletal muscle in neonatal pigs and is independently regulated by both anabolic agents (O’Connor et al., 2003; Davis et al., 2002). This is notable as studies with adult skeletal muscle tissue showed no response to insulin in terms of activating protein synthesis pathways (Barazzoni et al., 2012), and protein synthesis in the viscera of neonatal pigs is also not affected by the presence of insulin (Davis et al., 2001). Because skeletal muscle of the neonatal pig can respond independently to both postprandial signaling molecules, it poises the skeletal muscle to be able to undergo more pronounced protein accretion.

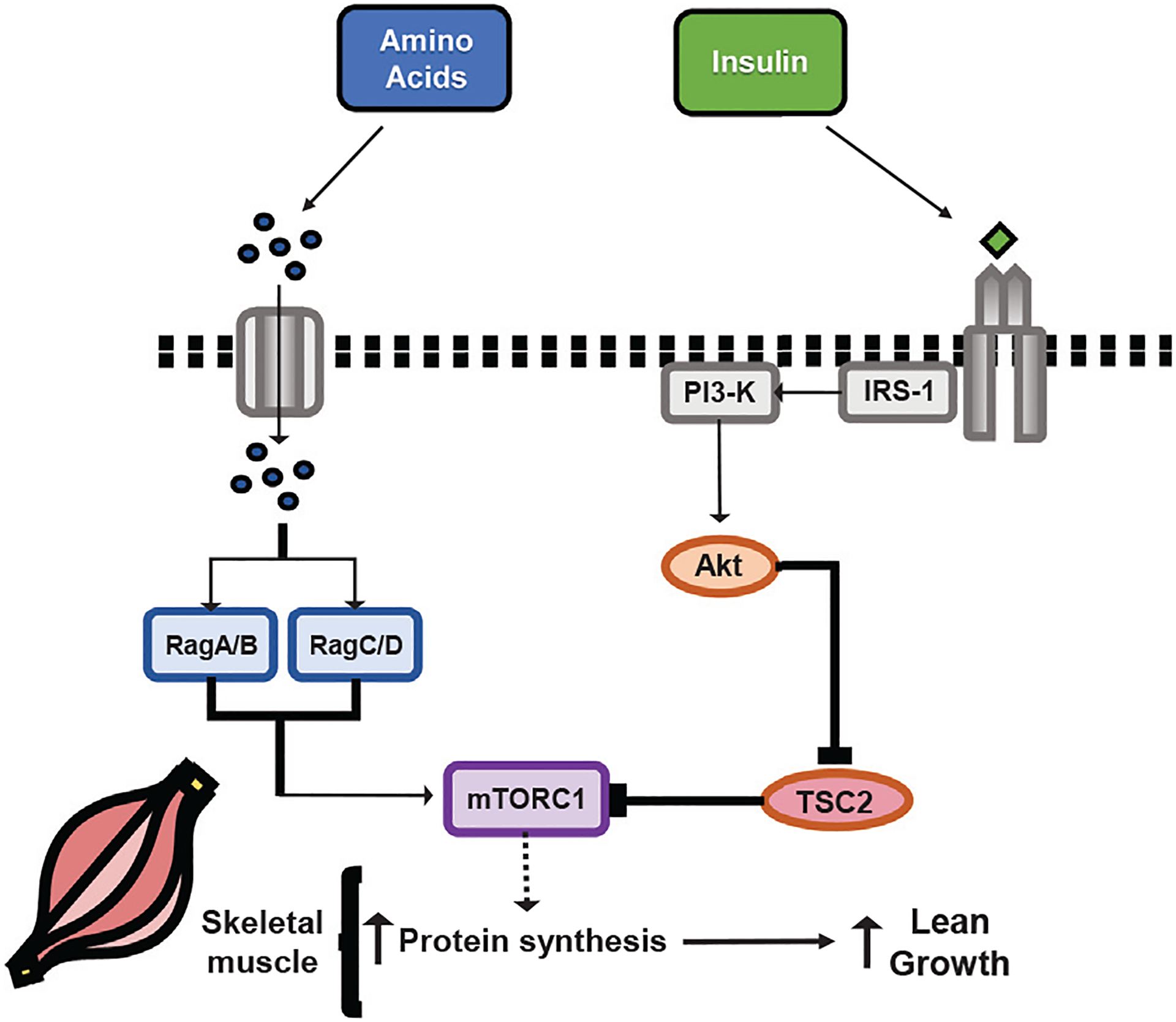

Insulin and amino acids act separately as anabolic signals to increase protein synthesis in skeletal muscle of the neonatal pig through stimulation of upstream activators of mTORC1 (Suryawan et al., 2001; Suryawan et al., 2006) (Fig. 1). This complex, named for the mTOR enzyme that acts as its catalytic site, is the master regulating kinase of protein synthesis (Saxton and Sabatini, 2017). mTORC1 then acts through its downstream signaling cascades to activate translation initiation factors that regulate the binding of messenger RNA (mRNA) to the ribosome. These downstream effectors of mTORC1, together with factors that recruit the binding of methionyl-transfer RNA (met-tRNA) to the ribosome (Ma and Blenis, 2009), allow for newly synthesized proteins to be produced, leading to increased skeletal muscle deposition in the neonate.

Fig. 1.

Insulin and amino acids act through separate intracellular signaling pathways to stimulate mTORC1, resulting in increased skeletal muscle protein synthesis and increased lean growth in neonatal pigs. Insulin acts through PI3K/Akt inhibition of TSC2 (a potent inhibitor of mTORC1) while amino acids facilitate mTORC1 association with Rag proteins (a necessary component of mTORC1 activation). Adapted from Rudar et al. (2021b). Abbreviations: Akt = Ak strain transforming; IRS1 = insulin receptor substrate 1; mTORC1 = mechanistic target of rapamycin complex 1; PI3K = phosphoinositide 3 kinase; Rag = RAS-related GTP-binding; TSC2 = tuberous sclerosis complex 2.

Skeletal muscle in neonatal swine is exceptionally sensitive to feeding-induced changes in the plasma concentrations of nutrients due to an enhanced sensitivity of the signaling pathways both upstream and downstream of mTORC1 (Rudar et al., 2019). Therefore, adequate nutrient intake, especially protein intake, is vital for neonatal health, as insufficient protein intake in neonatal pigs leads to growth faltering and decreased response of skeletal muscle protein synthesis to meal feeding (Columbus et al., 2015; Frank et al., 2006). Amino acid-specific stimulation of these protein synthesis signaling cascades also underscores an important, but often misunderstood aspect of nutrition—there is no simple “whole protein” requirement. Instead, there are multiple requirements each day for different amino acids and the amino acid content of a meal will impact the postprandial response of protein synthesis in skeletal muscle (Posey et al., 2021; Devries et al., 2018; Hou and Wu, 2017). This can significantly impact the growth of the neonatal pig, especially early-weaned piglets when they are switched from sow’s milk (a comparatively good source of proteinogenic and protein synthesis-stimulating amino acids, including leucine and glycine [Wu and Knabe, 1994]) to traditional plant-based swine diets (low in leucine, glycine, and arginine [Li and Wu, 2020; Hou et al., 2019]) during the critical growth period from birth to traditional weaning age (approximately 21–28 days after birth). Therefore, having a thorough understanding of the mechanisms by which insulin and amino acids stimulate translation initiation and protein synthesis, including the upstream and downstream signaling pathways of mTORC1 activation, is vital for optimizing swine growth performance and overall productivity.

Insulin regulates mechanistic target of rapamycin complex 1 activity

In the neonatal pig, protein synthesis markedly increases following a meal, though studies have shown this effect decreases with age and is blunted in the low birth weight neonatal pig (Davis et al., 1996; Paddon-Jones and Rasmussen, 2009; Naberhuis et al., 2019; Rudar et al., 2021a). One reason for this dramatic response to meal feeding is the rapid rise in plasma insulin, as insulin induces mTORC1 activation in skeletal muscle (Garami et al., 2003). This insulin-induced response is notable as this is unique to the skeletal muscle of the neonatal monogastric, as studies with neonatal ruminants have not shown an increase in protein synthesis in response to infusion with insulin (Wester et al., 2004; Bequette et al., 2002; Oddy et al., 1987). While insulin infusion alone did not appear to stimulate protein synthesis in these studies, it should be noted that insulin reduced circulating levels of amino acids, potentially limiting protein synthesis activation by insulin.

In early neonatal life, when insulin binds to the transmembrane insulin receptor on the surface of a skeletal myocyte, it initiates an intracellular signaling cascade that results in the induction of mTORC1 activation. While insulin can signal through multiple pathways, affecting different processes within a cell, stimulation of the phosphoinositide 3 kinase (PI3K)-Ak strain transforming (Akt)/protein kinase B (PKB) pathway results in increased protein synthesis. The binding of insulin to its receptor on the surface of insulin-responsive cells induces autophosphorylation of the receptor, leading to the recruitment of insulin receptor substrate 1 (IRS1) and activation of PI3K. This in turn phosphorylates and activates Akt (also known as PKB) (Hoxhaj and Manning, 2020) which stimulates the rapid phosphorylation, and subsequent inactivation, of tuberous sclerosis complex 2 (TSC2), an inhibitor of mTORC1 (Hoxhaj and Manning, 2020; Menon et al., 2014). The phosphorylation and inhibition of TSC2 cause TSC to release its inhibitory hold on mTOR, allowing mTOR to associate with Rheb on the lysosomal membrane, leading to mTORC1 activation (Saxton and Sabatini, 2017; Inoki et al., 2003; Garami et al. 2003). Notably, previous work utilizing the neonatal piglet pancreatic-clamp technique (described in Davis et al., 1998) to increase insulin to fed levels leads to stimulation of the insulin signaling pathway, including activation of PI3K and Akt, the phosphorylation of TSC2, and formation of the RAS-homolog enriched in brain (Rheb)-mTOR association complex (Suryawan et al., 2007; O’Connor et al., 2003). However, the activation of this pathway is blunted in skeletal muscle of the preterm piglet, with hyperinsulinemic-euaminoa cidemic-euglycemic clamps showing lower phosphorylation of Akt and TSC2 and reduced Rheb-mTOR association in response to insulin in muscle of preterm compared to term neonates (Rudar et al., 2021a). Notably, this specific cellular signaling pathway was shown to not be affected by amino acids using the euinsulinemic-hyperaminoacidemic-euglycemic clamp technique (Suryawan et al., 2009; Suryawan et al., 2007; Suryawan et al., 2004; O’Connor et al., 2003).

Amino acids regulate mechanistic target of rapamycin complex 1 activity

Feeding increases protein synthesis in part due to the increase in amino acids that make up the protein source in the meal. We have previously shown that a rise in leucine, a branched-chain amino acid that is both proteinogenic and an anabolic signaling molecule, is sufficient nutrient stimulus to increase the rate of protein synthesis in skeletal muscle of the neonatal pig (Suryawan et al. 2008; Escobar et al., 2005, 2006, and 2007). This increase in protein synthesis is a result of the activation of mTORC1 due to the activation of upstream amino acid sensing pathways that are independent of the insulin stimulatory pathway. While more work is needed to fully elucidate all pathways involved in mTORC1 stimulation by amino acids, studies largely conducted in vitro have led to acceptance of the following model (Yao et al., 2017; Chantranupong et al., 2016; Wolfson et al., 2016; Bar-Peled and Sabatini, 2014). Upon amino acid transport into the cell, these nutrients signal through the heterodimeric RAS-related GTPbinding (Rag) A/B and Rag C/D proteins. In association with Rag A/B GTPase (bound to GTP) or Rag C/D GTPase (bound to GDP), mTOR moves to the lysosomal membrane. This occurs with concurrent activity of the Ragulator proteins (LAMPTOR1–5) and vacuolar H+-ATPase (V-ATPase). The movement of mTOR to the lysosomal membrane allows it to interact with the lysosome-associated Rheb protein (a potent stimulator of mTORC1), leading to the activation of mTORC1 (Bar-Peled and Sabatini, 2014). The Rheb protein becomes active following the removal of TSC inhibition via the insulin-sensing pathway or via an insulinindependent adenosine monophosphate-activated protein kinase (AMPK) phosphorylation pathway. However, there is no evidence of changes in acetyl-CoA carboxylase (ACC) (an indicator protein of AMPK activity) abundance or phosphorylation due to amino acids, insulin, or age. Additionally, results from previous work show no change in AMPK phosphorylation following amino acid supplementation, indicating a low likelihood that AMPK plays a vital role in amino acid-driven mTORC1 activation in neonatal muscle (Rudar et al., 2021a; Manjarín et al., 2020; Suryawan and Davis, 2018; Manjarín et al., 2018; Boutry et al., 2013).

Leucine is a potent stimulator of amino acid-driven mTORC1 activation. This is due to the activity of stress response protein 2 (Sestrin2) and its interaction with the GTPase-activating protein activation toward Rags (GATOR) proteins (Sadria and Layton, 2021; Chantranupong et al., 2016; Wolfson et al., 2016; Kim et al., 2015). During fasting, Sestrin2 binds to GATOR2, acting as a potent inhibitor of GATOR1. Active GATOR1 binds to mTOR and prevents it from associating with Rag A/B or Rag C/D for localization to the lysosome (the location of the master activator, Rheb). However, Sestrin2 also acts as a nutrient sensor and is especially sensitive to the presence of leucine. Upon transport of leucine into the cell, the amino acid binds to Sestrin2 (Wolfson et al., 2016), leading to Sestrin2 inhibition. Inhibiting Sestrin2 releases active GATOR2 to associate with GATOR1. Upon GATOR protein interaction, GATOR1 releases its inhibition on mTOR allowing for interaction with the Rag proteins. Once released from GATOR1, mTOR is free to associate with the Rag proteins to be translocated to the lysosomal membrane for activation. In this way, leucine stimulates the binding of Rag A and Rag C to mTOR, leading to increased protein synthesis (Suryawan and Davis, 2018; Hong-Brown et al., 2012). Our previous work has shown an increased formation of the Rag A-mTOR and Rag C-mTOR complexes in skeletal muscle of the neonatal pig in response to feeding or in response to ingestion of a leucine-supplemented diet (Rudar et al., 2021a; Suryawan et al., 2020; Suryawan and Davis, 2018; Boutry et al., 2016).

Arginine is also a possible stimulator of mTORC1 activation that functions through the putative arginine sensor, SLC38A9 (Rebsamen et al., 2015; Wang et al., 2015). SLC38A9, an amino acid transporter, has been shown to regulate mTORC1 activation through the Rag-Ragulator complex in vitro (Jung et al., 2015). However, other results showed that the abundance of SLC38A9 was not affected by amino acids, insulin, or age in the neonatal pig (Suryawan and Davis, 2018). Therefore, as no other in vivo skeletal muscle data are available, further work is needed to determine the role of SLC38A9 in the integration of anabolic amino acid signaling.

Activation of mechanistic target of rapamycin complex 1 by insulin and amino acids leads to translation initiation in neonatal skeletal muscle

Following the integration of the nutrient signaling components in the insulin and amino acid signaling pathways, these signals are then conveyed through mTOR kinase, the master regulator of translation initiation that controls the overall rate-limiting step of protein synthesis. The mTOR catalytic subunit associates with two protein complexes, mTORC1 and mTORC2, with mTORC1 serving as the primary anabolic signal integrating complex (Liu and Sabatini, 2020). However, in vitro results suggest that mTORC2 may reinforce the upstream anabolic signaling components necessary for mTORC1 activation (Sarbassov et al., 2002). Following localization to the lysosomal membrane by the Rag proteins (Rag A-mTOR, Rag C-mTOR), and subsequent activation through association with membrane-bound Rheb, mTORC1 initiates a series of downstream signaling cascades that activate translation initiation (Saxton and Sabatini, 2017). The most well-characterized downstream effectors are p70 ribosomal protein S6 kinase 1 (S6K1) and eukaryotic initiation factor (eIF)4E binding protein 1 (4EBP1). Both factors are recruited by Raptor, a critical component of mTORC1, which binds proteins at their TOR signaling motifs (TOS), facilitating phosphorylation by mTOR kinase (Nojima et al., 2003). When active, 4E-BP1 binds and sequesters eIF4E, preventing the formation of the eIF4E·eIF4G complex required for the recruitment of mRNA to the 43S preinitiation complex and translation initiation (Ma and Blenis, 2009). Upon multisite phosphorylation by mTORC1 (Böhm et al., 2021), 4E-BP1 becomes inactive, releasing eIF4E and allowing for eIF4E·eIF4G complex formation and promoting translation initiation (Liu and Sabatini, 2020). Unlike its inhibitory effect on 4E-BP1, mTORC1 phosphorylation results in S6K1 activation. S6K1 activation results in phosphorylation of many downstream target proteins involved in translation initiation and elongation including eIF4B (enhances the RNA helicase activating of eIF4A), ribosomal protein (rp) S6 (a component of the small ribosomal subunit), and eukaryotic elongation factor (eEF)2 kinase (prevents inactivation of eEF2) (Saxton and Sabatini, 2017). Our previous work has shown that phosphorylation of mTORC1 and its downstream targets S6K1 and 4E-BP1 increases, as does the abundance of active eIF4E eIF4G complex, in skeletal muscle of neonatal pigs after feeding or in response to a rise in either amino acids or insulin to simulate fed levels (Boutry et al., 2013, 2016; Columbus et al., 2015; Suryawan et al., 2008, 2012; Gazzaneo et al., 2011; Escobar et al., 2005, 2010; Wilson et al., 2009; O’Connor et al., 2003).

Additionally, we have shown that the skeletal muscle of young neonatal pigs is especially sensitive to activation of these anabolic pathways. Amino acid and insulin signaling to mTORC1, the activation of translation initiation, and the stimulation of protein synthesis following a meal are elevated in the newborn and decrease with age (Suryawan et al., 2013; Suryawan and Davis, 2010; Escobar et al., 2007; Suryawan et al., 2007; Suryawan et al., 2001; Davis et al., 2000). This developmentally regulated sensitivity is due to an elevated abundance and postprandial activity of upstream and downstream mTORC1 effectors in skeletal muscle of the newborn that decreases with age (Suryawan and Davis, 2018; Kimball et al., 2000). These developmental differences in expression and activity would explain the increased sensitivity to both insulin and leucine signaling in young neonates and the heightened activation response of mTORC1. Growth factor receptor bound protein (GRB)10 phosphorylation has been reported to diminish IRS functionality, inhibiting the mTORC1 signaling pathway, in cell culture (Hsu et al. 2011; Yu et al. 2011). Neonatal pigs showed less GRB10 abundance than older pigs, resulting in a more stabilized signaling pathway (Suryawan and Davis, 2018). Additionally, DEP-containing mTOR-interacting protein (DEPTOR) is a strong inhibitor of mTORC1 (Peterson et al., 2009; Gao et al., 2011). Our results showed a decreased abundance of DEPTOR in skeletal muscle of the newborn pig compared to skeletal muscle of pigs 20 -days older (Suryawan and Davis 2018). There was also a greater abundance of both Sestrin2 (the “Leu sensing” protein that leads to the removal of GATOR1’s inhibitory action on mTORC1) (Wolfson et al., 2016) and LAMTOR 1 (a component of the critical Ragulator complex necessary for mTORC1 activation) (Bar-Peled and Sabatini, 2014) in skeletal muscle of 6- compared to 26-day-old pigs (Suryawan and Davis, 2018). These results suggest an increased sensitivity to leucine and increased mTORC1 activation threshold in neonatal pig skeletal muscle. Additionally, these results offer explanation for the sharp developmental decline in postmeal protein synthesis rates.

The neonatal pig is a highly translatable animal model of human infants

Livestock animals can provide valuable research insights for both agricultural and biomedical research (Spencer et al, 2022; Smith and Govoni, 2022; Polejaeva et al., 2016). The success of utilizing livestock animals, especially the piglet, as models for biomedical research highlights an important role for these animals as “dual purpose” models (Eicher et al, 2014; Hamernik, 2019). The piglet is a highly translatable animal model for studying human infant nutrition due to their high degree of similarity in physiology, metabolism, and stage of development in gestation (Bergen, 2022; Burrin et al., 2020). Additionally, many of the challenges of the newborn period faced by neonatologists are also seen in the swine industry, including low birth weight and concerns around early weaning. Therefore, utilizing livestock models creates collaborative research that can improve the efficiency and production of animal agriculture and the healthcare outcomes of humans. Providing “dual benefits” allows for greater access to resources, the formation of valuable collaborative efforts, and a shared goal of improving outcomes for all.

Conclusions

The rapid increase in swine growth during early neonatal life is driven by enhanced skeletal muscle sensitivity to feeding. Feeding results in the activation of mTORC1 and increased protein synthesis. This postmeal sensitivity of anabolic signaling is developmentally regulated, with marked responsiveness in early postnatal life which declines into adulthood. Thus, this enhanced sensitivity during the neonatal period provides a critical window for maximizing overall growth. Elucidation of the different signaling pathways that are activated in response to meal feeding have provided valuable insight into the developmental regulation of neonatal metabolism and growth, providing a metabolic understanding for the period of rapid growth seen in early neonatal life. Further, determining the upstream effectors of protein synthesis provides important metrics for assessing the effectiveness of targeted intervention strategies. With animal agriculture moving toward improved sustainability, targeted interventions represent opportunities for improving animal efficiency and decreasing waste, resulting in improved public perception of livestock production. For biomedical research, targeted intervention strategies in low birth weight infants to improve lean growth that results in lowered adiposity and risk of metabolic disease should decrease the economic and healthcare system impacts associated with these long-term morbidities. Overall improved understanding of the complex pathways regulating protein synthesis in the neonate has important implications for both agriculture and biomedical research.

Implications.

Understanding the mechanisms that regulate protein synthesis and lean growth in the neonate is instrumental for optimizing the nutritional support for neonatal pigs. Additionally, challenges faced by low birth weight and early-weaned piglets are similar to morbidities in preterm and low birth weight infants, making the neonatal piglet a valuable model for both agriculture and biomedical research in elucidating anabolic pathway regulation. Improved understanding of the pathways regulating lean growth in the neonatal pig will provide important information to promote sustainability and efficiency for swine production and to improve health outcomes for at-risk infants.

Acknowledgements

The contents of this publication do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the USDA, nor does any mention of trade names, commercial products, or organizations imply endorsement by the US government.

Financial support statement

Financial support for this project was provided by the National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Grants HD-085573 and HD-099080 (T.A. Davis); and US Department of Agriculture Current Research Information System Grant 6250-51000-055 (T.A. Davis).

Footnotes

Declaration of interest

None.

Data and model availability statement

None of the data were deposited in an official repository. Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no new data were created or analyzed.

References

- Alexander GR, 2007. Preterm Birth: Causes, Consequences, and Prevention. B, Prematurity at Birth: Determinants, Consequences, and Geographic Variation National Academies Press, Washington, DC, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Barazzoni R, Short KR, Asmann Y, Coenen-Schimke JM, Robinson MM, Nair KS, 2012. Insulin fails to enhance mTOR phosphorylation, mitochondrial protein synthesis, and ATP production in human skeletal muscle without amino acid replacement. American Journal of Physiology. Endocrinology and Metabolism 309, E1117–E1125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bar-Peled L, Sabatini DM, 2014. Regulation of mTORC1 by amino acids. Trends in Cell Biology 24, 400–406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bequette BJ, Kyle CE, Crompton LA, Anderson SE, Hanigan MD, 2002. Protein metabolism in lactating goats subjected to the insulin clamp. Journal of Dairy Science 85, 1546–1555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergen WG, 2022. Pigs (Sus Scrofa) in biomedical research. Advances in Experimental and Medical Biology 1354, 335–343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhatia J, 2013. Growth curves: how to best measure growth of the preterm infant. The Journal of Pediatrics 162, S2–S6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Böhm R, Imseng S, Jakob RP, Hall MN, Maier T, Hiller S, 2021. The dynamic mechanism of 4E-BP1 recognition and phosphorylation by mTORC1. Molecular Cell 81, 2403–2416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boutry C, El-Kadi SW, Suryawan A, Wheatley SM, Orellana RA, Kimball SR, Nguyen HV, Davis TA, 2013. Leucine pulses enhance skeletal muscle protein synthesis during continuous feeding in neonatal pigs. American Journal of Physiology. Endocrinology and Metabolism 305, E620–E631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boutry C, El-Kadi SW, Suryawan A, Steinhoff-Wagner J, Stoll B, Orellana RA, Nguyen HV, Kimball SR, Fiorotto ML, Davis TA, 2016. Pulsatile delivery of a leucine supplement during long-term continuous enteral feeding enhances lean growth in term neonatal pigs. American Journal of Physiology. Endocrinology and Metabolism 310, E699–E713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burrin D, Sangild PT, Stoll B, Thymann T, Buddington R, Marini J, Olutoye O, Shulman RJ, 2020. Translational advances in pediatric nutrition and gastroenterology: New insights from pig models. Annual Review of Animal Biosciences 8, 321–335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chantranupong L, Scaria SM, Saxton RA, Gygi MR, Shen K, Wyant GA, Wang T, Harper JW, Gygi SP, Sabatini DM, 2016. The CASTOR proteins are arginine sensors for the mTORC1 pathway. Cell 165, 153–164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Columbus DA, Steinhoff-Wagner J, Suryawan A, Nguyen HV, Hernandez-Garcia A, Fiorotto ML, Davis TA, 2015. Impact of prolonged leucine supplementation on protein synthesis and lean growth in neonatal pigs. American Journal of Physiology. Endocrinology and Metabolism 309, E601–E610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis TA, Fiorotto MF, Nguyen HV, Reeds PJ, 1989. Protein turnover in skeletal muscle of sucking rats. The American Journal of Physiology 257, R1141–R1146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis TA, Burrin DG, Fiorotto ML, Nguyen HV, 1996. Protein synthesis in skeletal muscle and jejunum is more responsive to feeding in 7- than in 26-day-old pigs. American Journal of Physiology. Endocrinology and Metabolism 270, E802–E809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis TA, Burrin DG, Fiorotto ML, Reeds PJ, Jahoor F, 1998. Roles of insulin and amino acids in the regulation of protein synthesis in the neonate. The Journal of Nutrition 128, 347S–350S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis TA, Fiorotto ML, 2009. Regulation of muscle growth in neonates. Current Opinion in Clinical Nutrition and Metabolic Care 12, 78–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis TA, Nguyen HV, Suryawan A, Bush JA, Jefferson LS, Kimball SR, 2000. Developmental changes in the feeding-induced stimulation of translation initiation in muscles of neonatal pigs. American Journal of Physiology. Endocrinology and Metabolism 279, E1226–E1234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis TA, Fiorotto ML, Beckett PR, Burrin DG, Reeds PJ, Wray-Cahen D, Nguyen HV, 2001. Differential effects of insulin on peripheral and visceral tissue protein synthesis in neonatal pigs. American Journal of Physiology. Endocrinology and Metabolism 280, E770–E779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis TA, Fiorotto ML, Burrin DG, Reeds PJ, Nguyen HV, Beckett PR, Vann RC, O’Connor PM, 2002. Stimulation of protein synthesis by both insulin and amino acids is unique to skeletal muscle in neonatal pigs. American Journal of Physiology. Endocrinology and Metabolism 282, E880–E890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeFronzo RA, Tobin JD, Andres R, 1979. Glucose clamp technique: a method for quantifying insulin secretion and resistance. American Journal of Physiology 237, E214–E223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devries MC, McGlory C, Bolster DR, Kamil A, Rahn M, Harkness L, Baker SK, Phillips SM, 2018. Leucine, not total protein, content of a supplement is the primary determinant of muscle protein anabolic responses in healthy older women. The Journal of Nutrition 148, 1088–1095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eicher S, Miller LC, Sordillo LM, 2014. Dual purpose with dual benefit research models in veterinary and biomedical research. Veterinary Immunology and Immunopathology 159, 111–112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Kadi SW, Suryawan A, Gazzaneo MC, Srivastava N, Orellana RA, Nguyen HV, Lobley GE, Davis TA, 2012. Anabolic signaling and protein deposition are enhanced by intermittent compared with continuous feeding in skeletal muscle of neonates. American Journal of Physiology. Endocrinology and Metabolism 302, E674–E686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engelsmann MN, Jensen LD, van der Heide ME, Hedemann MS, Nielsen TS, Nørgaard JV, 2022. Age-dependent development in protein digestibility and intestinal morphology in weaned pigs fed different protein sources. Animal 16, 100439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Escobar J, Frank JW, Suryawan A, Nguyen HV, Kimball SR, Jefferson LS, Davis TA, 2005. Physiological rise in plasma leucine stimulates muscle protein synthesis in neonatal pigs by enhancing translation initiation factor activation. American Journal of Physiology. Endocrinology and Metabolism 288, E914–E921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Escobar J, Frank JW, Suryawan A, Nguyen HV, Kimball SR, Jefferson LS, Davis TA, 2006. Regulation of cardiac and skeletal muscle protein synthesis by individual branched-chain amino acids in neonatal pigs. American Journal of Physiology. Endocrinology and Metabolism 290, E612–E621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Escobar J, Frank JW, Suryawan A, Nguyen HV, Davis TA, 2007. Amino acid availability and age affect the leucine stimulation of protein synthesis and eIF4F formation in muscle. American Journal of Physiology. Endocrinology and Metabolism 293, E1615–E1621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Escobar J, Frank JW, Suryawan A, Nguyen HV, Van Horn CG, Hutson SM, Davis TA, 2010. Leucine and a-ketoisocaproic acid, but not norleucine, stimulate skeletal muscle protein synthesis in neonatal pigs. Journal of Nutrition 140, 1418–1424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frank JW, Escobar J, Suryawan A, Nguyen HV, Kimball SR, Jefferson LS, Davis TA, 2006. Dietary protein and lactose increase translation initiation factor activation and tissue protein synthesis in neonatal pigs. American Journal of Physiology. Endocrinology and Metabolism 290, E225–E233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao D, Inuzuka H, Tan MKM, Fukushima H, Locasale JW, Liu P, Wan L, Zhai B, Chin YR, Shaik S, Lyssiotis CA, Gygi SP, Toker A, Cantley LC, Asara JM, Harper JW, Wei W, 2011. mMTOR drives its own activation via SCF (bTrCP)-dependent degradation of the mTOR inhibitor DEPTOR. Molecular Cell 44, 290–303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garami A, Zwartkruis FJ, Nobukuni T, Joaquin M, Roccio M, Stocker H, Kozma SC, Hafen E, Bos JL, Thomas G, 2003. Insulin activation of Rheb, a mediator of mTOR/S6K/4E-BP signaling, is inhibited by TSC1 and 2. Molecular Cell 11, 1457–1466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gazzaneo MC, Suryawan A, Orellana RA, Torraza RM, El-Kadi SW, Wilson FA, Kimball SR, Srivastava N, Nguyen HV, Fiorotto ML, Davis TA, 2011. Intermittent bolus feeding has a greater stimulatory effect on protein synthesis in skeletal muscle than continuous feeding in neonatal pig. Journal of Nutrition 141, 2152–2158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldenberg RL, Culhane JF, 2007. Low birth weight in the United States. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 85, 584S–590S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomez LAC, Herrera AL, Suescun JEP, 2015. La inclusión de cepas probióticas mejora los parámetros inmunológicos en pollos de engorde. Ces Medicina Veterinaria y Zootecnia 10, 160–169. [Google Scholar]

- Hamernik DL, 2019. Farm animals are important biomedical models. Animal Frontiers 9, 3–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong-Brown LQ, Brown CR, Kazi AA, Navaratnarajah M, Lang CH, 2012. Rag GTPases and AMPK/TSC2/RHEB mediate the differential regulation of mTORC1 signaling in response to alcohol and leucine. American Journal of Physiology. Cell Physiology 302, C1557–C1565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hou YQ, He WL, Hu SD, Wu G, 2019. Composition of polyamines and amino acids in plant-source foods for human consumption. Amino Acids 51, 1153–1165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hou YQ, Wu G, 2017. Nutritionally nonessential amino acids: a misnomer in nutritional sciences. Advances in Nutrition 8, 137–139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoxhaj G, Manning BD, 2020. The PI3K-AKT network at the interface of oncogenic signaling and cancer metabolism. Nature Reviews. Cancer 20, 74–88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsu PP, Kang SA, Rameseder J, Zhang Y, Ottina KA, Lim D, Peterson TR, Choi Y, Gray NS, Yaffe MB, Marto JA, Sabatini DM, 2011. The mTOR regulated phosphoproteome reveals a mechanism of mTORC1-mediated inhibition of growth factor signaling. Science 332, 1317–1322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inoki K, Li Y, Xu T, Guan KL, 2003. Rheb GTPase is a direct target of TSC2 GAP activity and regulates mTOR signaling. Genes and Development 17, 1829–1834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson MJ, Wootton SA, Leaf AA, Jackson AA, 2012. Preterm birth and body composition at term equivalent age: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Pediatrics 130, e640–e649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jung J, Genau HM, Behrends C, 2015. Amino acid-dependent mTORC1 regulation by the lysosomal membrane protein SLC38A9. Molecular and Cell Biology. 35, 2479–2494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kao LS, Morris BH, Lally KP, Stewart CD, Huseby V, Kennedy KA, 2006. Hyperglycemia and morbidity and mortality in extremely low birth-weight infants. Journal of Perinatology: Official Journal of the California Perinatal Association 26, 730–736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim JS, Ro S, Im M, Park H, Semple I, Park H, Cho U, Wang W, Guan K, Karin M, Lee JH, 2015. Sestrin2 inhibits mTORC1 through modulation of GATOR complexes. Scientific Reports 5, 9502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimball SR, Jefferson LS, Nguyen HV, Suryawan A, Bush JA, Davis TA, 2000. Feeding stimulates protein synthesis in muscle and liver of neonatal pigs through an mTOR-dependent process. American Journal of Physiology. Endocrinology and Metabolism 279, E1080–E1087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li P, Wu G, 2020. Composition of amino acids and related nitrogenous nutrients in feedstuffs for animal diets. Amino Acids 52, 523–542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu GY, Sabatini DM, 2020. mTOR at the nexus of nutrition, growth, ageing and disease. Nature Reviews. Molecular Cell Biology 21, 183–203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma XM, Blenis J, 2009. Molecular mechanisms of mTOR-mediated translational control. Nature Reviews. Molecular Cell Biology 10, 307–318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manjarín R, Columbus DA, Solis J, Hernandez-García AD, Suryawan A, Nguyen HV, McGuckin MM, Jimenez RT, Fiorotto ML, Davis TA, 2018. Short- and long-term effects of leucine and branched-chain amino acid supplementation of a protein- and energy-reduced diet on muscle protein metabolism in neonatal pigs. Amino Acids 50, 943–959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manjarín R, Boutry-Regard C, Suryawan A, Canovas A, Piccolo BD, Maj M, Abo-Ismail M, Nguyen HV, Fiorotto ML, Davis TA, 2020. Intermittent leucine pulses during continuous feeding alters novel components involved in skeletal muscle growth of neonatal pigs. Amino Acids 52, 1319–1335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- March of Dimes, 2022. Premature Birth Report Card. Retrieved on 20 December 2022 from https://www.marchofdimes.org/about/news/march-dimes-2022-report-card-shows-us-preterm-birth-rate-hits-15-year-high-rates.

- Markofski MM, Dickinson JM, Drummond MJ, Fry CS, Fujita S, Gundermann DM, Glynn EL, Jennings K, Paddon-Jones D, Reidy PT, Sheffield-Moore M, Timmerman KL, Rasmussen BB, Volpi E, 2015. Effect of age on basal muscle protein synthesis and mTORC1 signaling in a large cohort of young and older men and women. Experimental Gerontology 65, 1–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markopoulou P, Papanikolaou E, Analytis A, Zoumakis E, Siahanidou T, 2019. Preterm birth as a risk factor for metabolic syndrome and cardiovascular disease in adult life: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Pediatrics 210, 69–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathews TJ, Driscoll AK, 2017. Trends in infant mortality in the United States, 2005–2014. NCHS Data Brief 279, 1–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McIntire DD, Bloom SL, Casey BM, K.j., 1999. Birth weight in relation to morbidity and mortality among newborn infants. New England Journal of Medicine 340, 1234–1238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menon S, Dibble CC, Talbott G, Hoxhaj G, Valvezan AJ, Takahashi H, Cantley LC, Manning BD, 2014. Spatial control of the TSC complex integrates insulin and nutrient regulation of mTORC1 at the lysosome. Cell 156, 771–785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mota-Rojas D, Orozco-Gregorio H, Villanueva-Garcia D, Bonilla-Jaime H, Suarez-Bonilla X, Hernandez-Gonzalez R, Roldan-Santiago P, Trujillo-Ortega ME, 2011. Foetal and neonatal energy metabolism in pigs and humans: a review. Veterinární Medicína 56, 215–225. [Google Scholar]

- Naberhuis JK, Suryawan A, Nguyen HV, Hernandez-Garcia A, Cruz SM, Lau PE, Olutoye OO, Stoll B, Burrin DG, Fiorotto ML, Davis TA, 2019. Prematurity blunts feeding-induced stimulation of translation in initiation signaling and protein synthesis in muscle of neonatal piglets. American Journal of Physiology. Endocrinology and Metabolism 317, E839–E851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Narwal R, Adler A, Vera GC, Rohde S, Say L, Lawn JE, 2012. National, regional, and worldwide estimates of preterm birth rates in the year 2010 with time trends since 1990 for selected countries: a systematic analysis and implications. Lancet 379, 2162–2172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nojima H, Tokunaga C, Eguchi S, Oshiro N, Hidayat S, Yoshino K, Hara K, Tanaka N, Avruch J, Yonezawa K, 2003. The mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) partner, raptor, binds the mTOR substrates p70 S6 kinase and 4E-BP1 through their TOR signaling (TOS) motifs. The Journal of Biological Chemistry 278, 15461–15464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Connor PMJ, Bush JA, Suryawan A, Nguyen HV, Davis TA, 2003. Insulin and amino acids independently stimulate skeletal muscle protein synthesis in neonatal pigs. American Journal of Physiology. Endocrinology and Metabolism 284, E110–E119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oddy VH, Lindsay DB, Barker PJ, Northrop AJ, 1987. Effect of insulin on hindlimb and whole-body leucine and protein metabolism in fed and fasted sheep. British Journal of Nutrition 58, 143–154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paddon-Jones D, Rasmussen BB, 2009. Dietary protein recommendations and the prevention of sarcopenia. Current Opinion in Clinical Nutrition and Metabolic Care 12, 86–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peterson TR, Laplante M, Thoreen CC, Sancak Y, Kang SA, Kuehl WM, Gray NS, Sabatini DM, 2009. DEPTOR is an mTOR inhibitor frequently overexpressed in multiple myeloma cells and required for their survival. Cell 137, 873–886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polejaeva IA, Rutigliano HM, Wells KD, 2016. Livestock in biomedical research: history, current status and future prospective. Reproduction, Fertility, and Development 28, 112–124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Posey EA, Bazer FW, Wu G, 2021. Amino acids and their metabolites for improving human exercising performance. Amino Acids in Nutrition and Health. Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology 1332, 151–166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rebsamen M, Pochini L, Stasyk T, de Araújo ME, Galluccio M, Kandasamy RK, Snijder B, Fauster A, Rudashevskaya EL, Bruckner M, Scorzoni S, Filipek PA, Huber KV, Bigenzahn JW, Heinz LX, Kraft C, Bennett KL, Indiveri C, Huber LA, Superti-Furga G, 2015. SLC38A9 is a component of the lysosomal amino acid sensing machinery that controls mTORC1. Nature 519, 477–481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reeds PJ, Cadenhead A, Fuller M, Lobley G, McDonald J, 1980. Protein turnover in growing pigs. Effects of age and food intake. British Journal of Nutrition 43, 445–455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riddersholm KV, Bahnsen I, Bruun TS, de Knegt LV, Amdi C, 2021. Identifying risk factors for low piglet birth weight, high within-litter variation and occurrence of intrauterine growth-restricted piglets in hyperprolific sows. Animals 11, 2731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudar M, Fiorotto ML, Davis TA, 2019. Regulation of muscle growth in early postnatal life in a swine model. Annual Review of Animal Biosciences 15, 309–335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudar M, Naberhuis JK, Suryawan A, Nguyen HV, Stoll B, Style CC, Verla MA, Olutoye OO, Burrin DG, Fiorotto ML, Davis TA, 2021a. Prematurity blunts the insulin- and amino acid-induced stimulation of translation initiation and protein synthesis in skeletal muscle of neonatal pigs. American Journal of Physiology. Endocrinology and Metabolism 320, E551–E565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudar M, Naberhuis JK, Suryawan A, Nguyen HV, Stoll B, Style CC, Verla MA, Olutoye OO, Burrin DB, Fiorotto ML, Davis TA, 2021b. Intermittent bolus feeding does not enhance protein synthesis, myonuclear accretion, or lean growth more than continuous feeding in a premature piglet model. American Journal of Physiology. Endocrinology and Metabolism 321, E737–E752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sadria M, Layton AT, 2021. Interactions among mTORC, AMPK and SIRT: a computational model for cell energy balance and metabolism. Cell Communication and Signaling 19, 57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santos TC, Carvalho CDCS, Da Silva GC, Diniz TA, Soares TE, Moreira SDJM, Cecon PR, 2018. Influência do ambiente térmico no comportamento e desempenho zootécnico de suínos. Revista de Ciências Agroveterinárias 17, 241–253. [Google Scholar]

- Sarbassov DD, Ali SM, Sengupta S, Sheen JH, Hsu PP, Bagley AF, Markhard AL, Sabatini DM, 2002. Prolonged rapamycin treatment inhibits mTORC2 assembly and Akt/PKB. Molecular Cell 22, 159–168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saxton RA, Sabatini DM, 2017. mTOR signaling in growth, metabolism, and disease. Cell 168, 960–976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith BI, Govoni KE, 2022. Use of agriculturally important animals as models in biomedical research. Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology 1354, 315–333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sondheimer JM, Asturias E, Cadnapaphornchai M, 1998. Infection and cholestasis in neonates with intestinal resection and long-term parenteral nutrition. Journal of Pediatric Gastroenterology and Nutrition 27, 131–137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spencer TE, Wells KD, Lee K, Telugu BP, Hansen PJ, Bartol FF, Blomberg L, Schook LB, Dawson H, Lunney JK, Driver JP, Davis TA, Donovan SM, Dilger RN, Saif LJ, Moeser A, McGill JL, Smith G, Ireland JJ, 2022. Future of biomedical, agricultural and biological systems research using domesticated animals. Biology of Reproduction 106, 629–638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suryawan A, Davis TA, 2010. The abundance and activation of mTORC1 regulators in skeletal muscle of neonatal pigs are modulated by insulin, amino acids, and age. Journal of Applied Physiology 109, 1448–1454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suryawan A, Davis TA, 2018. Amino acid- and insulin-induced activation of mTORC1 in neonatal piglet skeletal muscle involves Sestrin2-GATOR2, Rag A/C-mTOR, and RHEB-mTOR complex formation. The Journal of Nutrition 148, 825–833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suryawan A, Nguyen HV, Bush JA, Davis TA, 2001. Developmental changes in the feeding-induced activation of the insulin-signaling pathway in neonatal pigs. American Journal of Physiology. Endocrinology and Metabolism 281, E908–E915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suryawan A, O’Connor PMJ, Kimball SR, Bush JA, Nguyen HV, Jefferson LS, Davis TA, 2004. Amino acids do not alter the insulin-induced activation of the insulin signaling pathway in neonatal pigs. The Journal of Nutrition 134, 24–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suryawan A, Escobar J, Frank JW, Nguyen HV, Davis TA, 2006. Developmental regulation of the activation of signaling components leading to translation initiation in skeletal muscle of neonatal pigs. American Journal of Physiology. Endocrinology and Metabolism 291, E849–E859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suryawan A, Orellana RA, Nguyen HV, Jeyapalan AS, Fleming JR, Davis TA, 2007. Activation by insulin and amino acids of signaling components leading to translation initiation in skeletal muscle of neonatal pigs is developmentally regulated. American Journal of Physiology. Endocrinology and Metabolism 293, E1597–E1605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suryawan A, Jeyapalan AS, Orellana RA, Wilson FA, Nguyen HV, Davis TA, 2008. Leucine stimulates protein synthesis in skeletal muscle of neonatal pigs by enhancing mTORC1 activation. American Journal of Physiology. Endocrinology and Metabolism 295, E868–E875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suryawan A, O’Connor PMJ, Bush JA, Nguyen HV, Davis TA, 2009. Differential regulation of protein synthesis by amino acids and insulin in peripheral and visceral tissues of neonatal pigs. Amino Acids 37, 97–104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suryawan A, Torrazza RM, Gazzaneo MC, Orellana RA, Fiorotto ML, El-Kadi SW, Srivastava N, Nguyen HV, Davis TA, 2012. Enteral leucine supplementation increases protein synthesis in skeletal and cardiac muscles and visceral tissues of neonatal pigs through mTOR1-dependent pathways. Pediatric Research 71, 324–331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suryawan A, Nguyen HV, Almonaci RD, Davis TA, 2013. Abundance of amino acids transporters involved in mTORC1 activation in skeletal muscle of neonatal pigs is developmentally regulated. Amino Acids 45, 523–530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suryawan A, Rudar M, Fiorotto ML, Davis TA, 2020. Differential regulation of mTORC1 activation by leucine and b-hydroxy-b-methylbutyrate in skeletal muscle of neonatal pigs. Journal of Applied Physiology 128, 286–295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valentim JK, Mendes JP, Caldara FR, Pietramale RTR, Garcia RG, 2021. Meta-analysis of relationship between weaning age and daily weight gain of piglets in the farrowing and nursery phases. South African Journal of Animal Science 51, 332–338. [Google Scholar]

- Volpi E, Mittendorfer B, Rasmussen BB, Wolfe RR, 2000. The response of muscle protein anabolism to combined hyperaminoacidemia and glucose-induced hyperinsulinemia is impaired in the elderly. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism 85, 4481–4490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang S, Tsun ZY, Wolfson RL, Shen K, Wyant GA, Plovanich ME, Yuan ED, Jones TD, Chantranupong L, Comb W, Wang T, Bar-Peled L, Zoncu R, Straub C, Kim C, Park J, Sabatini BL, Sabatini DM, 2015. Lysosomal amino acid transporter SLC38A9 signals arginine sufficiency to mTORC1. Science 347, 188–194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei X, Tsai T, Howe S, Zhao J, 2021. Weaning induced gut dysfunction and nutritional interventions in nursery pigs: a partial review. Animals 11, 1279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wester TJ, Lobley GE, Birnie LM, Crompton LA, Brown S, Buchan V, Calder AG, Milne E, Lomax MA, 2004. Effect of plasma insulin and branched-chain amino acids on skeletal muscle protein synthesis in fasted lambs. British Journal of Nutrition 92, 401–409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson FA, Suryawan A, Orellana RA, Kimball SR, Gazzaneo MC, Nguyen HV, Fiorotto ML, Davis TA, 2009. Feeding rapidly stimulates protein synthesis in skeletal muscle of neonatal pigs by enhancing translation initiation. The Journal of Nutrition 139, 1873–1880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolfson RL, Chantranupong L, Saxton RA, Shen K, Scaria SM, Cantor JR, Sabatini DM, 2016. Sestrin2 is a leucine sensor for the mTORC1 pathway. Science 351, 43–48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu G, 2018. Principles of Animal Nutrition. CRC Press, London, UK. [Google Scholar]

- Wu G, Bazer FW, Wallace JM, Spencer TE, 2006. Board-invited review: intrauterine growth retardation: implications for the animal sciences. Journal of Animal Science 84, 2316–2337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu G, Knabe DA, 1994. Free and protein-bound amino acids in sow’s colostrum and milk. The Journal of Nutrition 124, 415–424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yao Y, Jone E, Inoki K, 2017. Lysosomal regulation of mTORC1 by amino acids in mammalian cell. Biomolecules 7, 51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu Y, Yoon S-O, Poulogiannis G, Yang Q, Ma XM, Villén J, Kubica N, Hoffman GR, Cantley LC, Gygi SP, Blenis J, 2011. Phosphoproteomic analysis identifies GRB10 as an mTORC1 substrate that negatively regulates insulin signaling. Science 332, 1322–3126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang L, Lin JG, Liang S, Sun J, Gao NN, Wu Q, Zhang HY, Liu HJ, Cheng XD, Cao Y, Li Y, 2021. Comparison of postnatal growth charts of singleton preterm and term infants using World Health Organization standards at 40–160 weeks postmenstrual age: A Chinese single-center retrospective cohort study. Frontiers in Pediatrics 9, 595882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

None of the data were deposited in an official repository. Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no new data were created or analyzed.