Abstract

The changes in motility, chemotactic responsiveness, and flagellation of Rhizobium meliloti RMB7201, L5-30, and JJ1c10 were analyzed after transfer of the bacteria to buffer with no available C, N, or phosphate. Cells of these three strains remained viable for weeks after transfer to starvation buffer (SB) but lost all motility within just 8 to 72 h after transfer to SB. The rates of motility loss differed by severalfold among the strains. Each strain showed a transient, two- to sixfold increase in chemotactic responsiveness toward glutamine within a few hours after transfer to SB, even though motility dropped substantially during the same period. Strains L5-30 and JJ1c10 also showed increased responsiveness to the nonmetabolizable chemoattractant cycloleucine. Cycloleucine partially restored the motility of starving cells when added after transfer and prevented the loss of motility when included in the SB used for initial suspension of the cells. Thus, interactions between chemoattractants and their receptors appear to affect the regulation of motility in response to starvation independently of nutrient or energy source availability. Electron microscopic observations revealed that R. meliloti cells lost flagella and flagellar integrity during starvation, but not as fast, nor to such a great extent, as the cells lost motility. Even after prolonged starvation, when none of the cells were actively motile, about one-third to one-half of the initially flagellated cells retained some flagella. Inactivation of flagellar motors therefore appears to be a rapid and important response of R. meliloti to starvation conditions. Flagellar-motor inactivation was at least partially reversible by addition of either cycloleucine or glucose. During starvation, some cells appeared to retain normal flagellation, normal motor activity, or both for relatively long periods while other cells rapidly lost flagella, motor activity, or both, indicating that starvation-induced regulation of motility may proceed differently in various cell subpopulations.

As nutrient availability approaches zero in natural environments, populations of motile bacteria face a potentially crucial choice between searching actively for additional nutrients or shutting off motility to conserve energy and substrates. On the one hand, continued motility and chemotaxis may offer a population its best chance to find new nutrient supplies, avoid stress, mate, and reproduce. On the other hand, motility and taxis are inherently costly cellular processes, requiring the synthesis of perhaps 50 gene products and the performance of considerable mechanical work, with flagella rotating up to 15,000 rpm and requiring about 1,000 protons per revolution (19, 26, 28, 29). Thus, survival and competitive success in natural environments may require sophisticated, perhaps subpopulation-level regulation of motility and chemotaxis in response to low-level and fluctuating nutrient availability. Relatively few studies have examined the changes in behavior of flagellated bacteria in response to starvation or reduced nutrient availability, and none so far has involved soil or rhizosphere bacteria. Terracciano and Canale-Parola (30) reported that carbon-limited growth of a Spirochaeta species in chemostat cultures resulted in a 10- to 1,000-fold enhancement of chemotactic responsiveness to the specific sugars used to support growth, indicating that this bacterium selectively enhanced its behavioral sensitivity to low concentrations of growth-limiting nutrients. Certain marine vibrios became considerably more motile and chemotactically responsive between 15 and 72 h after transfer to starvation medium and also shifted to the use of high-affinity transporters (3, 11, 31, 32). However, another marine vibrio lost motility and responsiveness within 10 h after transfer to starvation conditions (20), while a marine Pseudomonas strain increased its motility after starvation for 27 h (35). It is not clear from these limited studies whether there are common patterns of behavioral regulation for flagellated bacteria in response to starvation conditions.

In this paper, we examine the starvation-induced changes in the motility behavior of a common soil and rhizosphere bacterium, Rhizobium meliloti. R. meliloti is an agriculturally important species that symbiotically nodulates alfalfa and fixes atmospheric nitrogen. It typically has five to eight peritrichous complex flagella. Complex flagella require divalent cations for functional integrity (24), and they are more rigid and appear to be more efficient in propulsion through viscous media than plain flagella (12, 13, 17, 21). R. meliloti is reported to swim by exclusive clockwise rotations of its flagella, with brief pauses or changes in speed for redirection, and it exhibits chemokinesis, swimming at higher speeds when exposed to higher attractant concentrations (13, 28). This bacterium is positively chemotactic toward a variety of amino acids, dicarboxylic acids, and sugars (2, 4, 12, 14), toward the nodulation gene-inducing flavonoids secreted by the roots of its host (8, 9), and toward unknown attractants secreted at localized sites on these roots (14). Mutants defective in motility or chemotaxis are impaired in their ability to compete for sites of nodule initiation on the host root (1, 7). The present article describes some of the changes in motility, chemotaxis, and flagellation seen in three strains of R. meliloti after transfer to starvation conditions and seeks to characterize the behavioral strategies used by this soil-rhizosphere species in response to starvation and the variability among strains of this species in their responses.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, media, and culture.

R. meliloti RMB7201 (15), L5-30 (7), and JJ1c10 (34) were maintained in 15% glycerol stock cultures at −80°C. The strains were routinely cultured at 28°C in 1/10-strength TY medium (0.6 g of tryptone, 0.3 g of yeast extract, and 0.5 g of CaCl2 · 2H2O per liter). In some experiments, NM minimal salts medium (24) was used, with 20 mM sodium succinate as the carbon source and 5 mM KNO3 as the nitrogen source. After autoclaving of the NM medium, and immediately before its use, 5 mg of CaCl2 · 2H2O and 1 ml of Gotz vitamin stock solution (12) were added per liter. Escherichia coli c118 (16) and HB101 (6) were cultured on Luria-Bertani medium at 37°C. All liquid cultures were grown on a rotary shaker at 175 to 200 rpm. Solid media were prepared by addition of 1.5% agar (Difco). All chemicals used for these media were analytical or reagent grade (Baker Chemical Co. or Sigma Chemical Co.). Cells were routinely harvested for transfer to starvation medium during early exponential phase (A590, ca. 0.15), the period during which the R. meliloti strains exhibit the greatest motility.

SB.

The chemotaxis buffer of Robinson et al. (24) was used as a starvation medium for these studies. Starvation buffer (SB) contains 10 mM HEPES (N-2-hydroxyethylpiperazine-N′-2-ethanesulfonic acid), 0.1 mM EDTA-Na, and 0.2 mM CaCl2, in high-performance liquid chromatography-grade (Baker Chemical Co.) or nanopure water, pH 7.0. This buffer was found to be optimal for maintaining the motility of R. meliloti and the integrity of its complex flagella (24). It is also suitable as a starvation medium since it contains no utilizable carbon, nitrogen, or energy source.

Motility and chemotaxis assays.

For routine analysis of motility after transfer of cells to starvation medium, early-exponential-phase cultures on 1/10-strength TY or NM-succinate medium were harvested by centrifugation at 1,800 × g for 10 min. The pellet was resuspended by vortexing in an equal volume of SB; a micropipet was carefully used to remove droplets of liquid from the tube after decanting and prior to cell resuspension. To determine the percentage of motile cells, an aliquot of a bacterial suspension was placed in a Petroff-Hauser counting chamber and observed at a magnification of ×860 under phase-contrast optics (Zeiss model I-35 inverted microscope). Only those cells in the focal plane of the grid surface were counted, and counting was performed rapidly (1 to 2 min) to minimize the settling of nonmotile cells. Reported percentages are averages of counts from two independent replicate suspensions for all experiments. A total of 60 to 100 cells from two or three different fields were counted per determination. The percentage of motile cells determined in this way was normally reproducible within ±10% for replicate samples. In some cases, video-recorded data were analyzed to obtain motile-cell percentages and to characterize motility behavior. Chemotactic responsiveness toward glutamine (10 mM in SB) or other attractants was determined by capillary assay in Palleroni chambers (22). Responsiveness is expressed as a chemotaxis ratio (the average number of cells entering attractant-filled capillaries divided by the average number of cells entering buffer-filled capillaries). Relative motility was also measured by entry into SB-filled capillary tubes (27). In some experiments, responsiveness was assayed with the attractant present in both the bacterial suspension and buffer-filled capillaries as a control. Entry into capillary tubes for motility and chemotaxis assays was determined after a 30-min incubation at room temperature. The average CFU per capillary tube was determined by plating aliquots of suspensions from four replicate tubes per data point.

Transfer to starvation conditions by membrane filtration.

Ten-milliliter aliquots of a mid-exponential-phase 1/10-strength TY or NM culture were filtered through micropore membranes of various types (0.02-μm-pore-size Anodisc [Alltech Associates, Inc., Deerfield, Ill.], 0.45-μm-pore-size cellulose acetate and nylon [Magna, Honeye, N.Y.], 0.22-μm-pore-size mixed cellulose esters [Poretics, Livermore, Calif.], or 0.4-μm-pore-size polycarbonate [Nucleopore Co., Pleasanton, Calif.]). After filtration, the filters were washed twice with SB (20 ml each), and the cells were subsequently resuspended by gentle agitation of the membrane in 10 ml of SB.

Flagellar staining and electron microscopy.

The percentage of flagellated cells was determined at various times after transfer to SB. A 3-μl droplet of the suspension was placed on a piece of Parafilm, and 1 μl of 2% uranyl acetate stain was added. After a few seconds of mixing, 2 μl of the droplet was transferred to a Formvar-coated 300-mesh copper grid. The cells were allowed to react with the stain and to settle onto the surface of the film for 5 min prior to being air dried in a laminar-flow hood. Grids were observed through a Phillips model 201 transmission electron microscope. Air drying of the grid surface left areas of rather dense stain, but other areas had a light background and were suitable for observation of bacteria and flagella. The percentage of cells with flagella was determined by observation of 75 to 100 cells per grid on at least two duplicate grids per sample.

RESULTS

Survival of R. meliloti in starvation medium.

Viable-cell counts of all three R. meliloti strains remained high after transfer to SB. The number of viable cells of strain JJ1c10 gradually diminished about 50-fold over a period of 120 days, but counts of strains L5-30 and RMB7201 remained almost unchanged, at about 108 CFU/ml, during this period.

Changes in motility in response to starvation conditions.

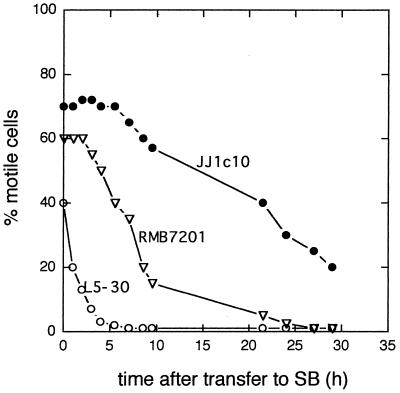

The visible motility of all three strains of R. meliloti diminished to almost zero within 6 to 72 h after transfer to starvation medium (Fig. 1). The length of time required for each of the three strains to reach either half-maximal or essentially zero motility was quite reproducible and also considerably different for each strain. These times were not significantly affected by the growth phase prior to harvest. The loss of motility seen in Fig. 1 was not affected by addition of trace metals or vitamins.

FIG. 1.

Changes in motility of R. meliloti L5-30 (○), RMB7201 (▿), and JJ1c10 (•) at various times after transfer to SB. Cells were transferred to SB and, at intervals, assayed microscopically to determine the percentage of motile cells as described in Materials and Methods. The data are from a single experiment. The curves shown are representative of those obtained in at least four other experiments. Replicate samples normally showed less than 10% variation from the mean.

The bacteria lost motility after transfer to SB regardless of whether they were transferred by centrifugal washing (Fig. 1), by membrane filtration, or by dialysis (data not shown). Centrifugal washing and resuspension was adopted for routine use in subsequent starvation response studies. Dialysis was considered unsuitable due to the relatively long time interval (>8 h) between the initiation of dialysis and essentially complete removal of nutrients from the bacterial suspensions. Membrane filtration through micropore membrane filters of various types allowed for rapid transfer to starvation conditions but resulted in large (>50%) reductions in the percentage of motile cells after resuspension in SB, presumably due to flagellar adhesion or damage (data not shown). Centrifugal washing was rapid and resulted in relatively small (5 to 10%) reductions in the percentage of motile cells and the percentage of flagellated cells during the transition from exponential-phase 1/10-strength TY cultures to fresh SB suspensions. The number of detached flagella present in the supernatants of the SB suspensions was found to be low, indicating that centrifugation and resuspension caused relatively little damage to flagella. Centrifugal washing, however, did not give complete recovery of the motile cells in the original cultures. At the relatively low centrifugation speeds that were used to pellet the cells as gently as possible, 10 to 15% of the motile cells remained in the supernatant.

Changes in chemotactic responsiveness upon exposure to starvation conditions.

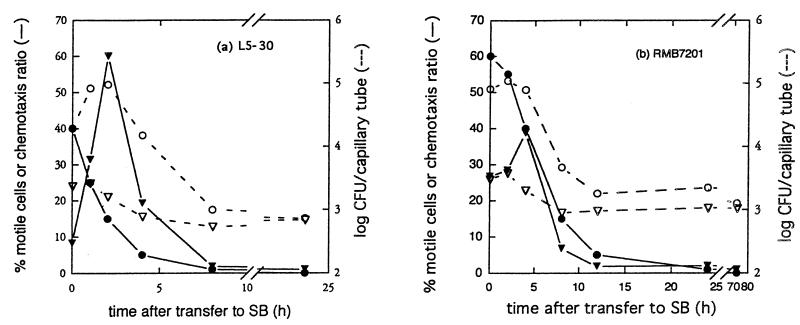

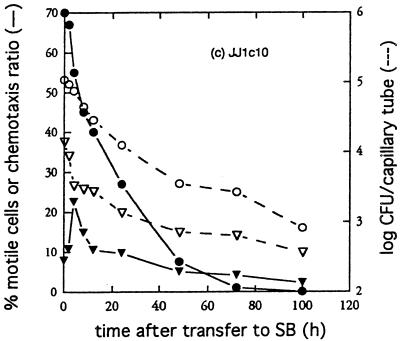

All three strains showed significant (two to sixfold) but transiently enhanced responsiveness to 10 mM glutamine within a few hours after transfer to starvation medium (Fig. 2). The enhanced responses occurred despite the fact that the overall motile activity diminished rapidly during the same time period. As shown in Fig. 3, L5-30 cells suspended in SB showed a transiently increased responsiveness to the nonmetabolizable attractant cycloleucine, similar to that obtained with glutamine. Cycloleucine is a potent attractant for R. meliloti (25) but does not support its growth and is not toxic (data not shown). The entry of cells into buffer-filled capillaries was not appreciably affected by the addition of cycloleucine to the bacterial suspension. Thus, enhanced entry of starving R. meliloti cells into cycloleucine-filled capillaries is not due to localized activation of motility in cells exposed to the attractant.

FIG. 2.

Changes in motility and chemotaxis of R. meliloti L5-30 (a), RMB7201 (b), and JJ1c10 (c) after transfer to SB. Cultures were transferred to SB and assayed at various times after transfer for percentage of motile cells and for chemotactic responsiveness as described in Materials and Methods. Graphed are the percentage of motile cells (•), the number of cells entering SB-filled capillary tubes (▿), and the number of cells entering capillary tubes containing 5 mM glutamine (○). The chemotaxis ratio (▾) was calculated by dividing the number of cells in attractant-filled capillaries by the number in SB-filled capillaries.

FIG. 3.

Chemotactic responsiveness of R. meliloti L5-30 to different concentrations of cycloleucine (CL) before and after starvation. L5-30 cells freshly transferred from 1/10-strength TY cultures to SB (○) or starved in SB for 2 h (•) were assayed for entry into capillary tubes filled with 5, 1, 0.2, 0.04, or 0.008 mM cycloleucine as described in Materials and Methods. Data points represent averages of values from four replicate capillaries. The chemotaxis ratio was calculated by dividing the number of cells in attractant-filled capillaries by the number in SB-filled capillaries. Curves are from a single experiment that was repeated with similar results.

Swimming behavior of cells exposed to starvation conditions.

Light and videomicroscopy revealed clear changes in the character of swimming behavior after transfer of R. meliloti cells to starvation medium. Immediately after transfer to SB, when 40 to 60% of the cells were motile, the cells were very active, swimming quite continuously with almost no discernible pauses. The swimming was relatively fast (ca. 20 to 30 μm/s) and straight, the bacteria often covering distances of 100 μm between abrupt changes of direction. The proportion of cells of all three strains that exhibited this normal swimming behavior diminished steadily after transfer to SB. By the time the percentages of motile cells had dropped to 15 to 25% of the initial levels, very few cells exhibited any smooth forward swimming. The average rate of forward movement of these starved cells was slower, perhaps one-third of the speed seen in fresh suspensions, and few cells moved more than 50 μm from their starting point within 1 min. Motile cells in starved suspensions seemed to change direction more frequently than those in fresh SB suspensions, and many of the swimming cells were observed to come to a complete stop, with no visible motion. Sometimes these stops lasted for a fraction of a second, while at other times they lasted 1 s or more before swimming was resumed. Near the grid surface, where motion is constrained, many motile cells in these starved suspensions were observed to move in circles 3 to 10 cell lengths in diameter. With longer periods of starvation, an increasing proportion of the motile cells appeared unable to swim at all and just spun or tumbled weakly in one location.

To ensure that light microscopic determinations of the percentage of motile cells provided an accurate measure of the changes in motility induced by starvation, and to see whether the reduced forward swimming behavior exhibited by starving cells might affect entry into pores (such as those found in soil), motility was measured by capillary assay as described by Segal et al. (27). Motilities measured by light microscopy and capillary assay did not always change in simple parallel to each other with time after cell transfer to starvation medium (Fig. 2). However, both measures of motility seem valid and useful. They provide averages over different time scales, with the microscopic assay giving an average over a short (roughly 1-min) time period and the capillary assay giving an average motility over a longer (30-min) time period.

Changes in flagellation of cells exposed to starvation conditions.

Initially, it seemed possible that the loss and disintegration of flagella could explain the observed losses of motility and normal swimming behavior following transfer to starvation conditions. To test this possibility, a simple method for determining the percentage of cells that retained flagella was devised. Grids for electron microscopy were prepared by mixing an SB suspension of bacteria with the uranyl acetate stain and drying this mixture directly on the grid film, without washing or blotting. This procedure prevented the potentially selective loss of actively motile cells during blotting as well as the potentially selective retention of any cells that might adhere more strongly to the grid film during blotting or washing. Addition of the uranyl acetate stain was observed to stop all motility within seconds, making it likely that the motile, flagellated cells settled on the surface of the film in much the same manner as nonflagellated cells. When freshly transferred suspensions of bacteria were examined, relatively few loose flagella or fragments of flagella were observed on the grids. Cells from growing cultures and those from freshly transferred suspensions were similar with regard to the number and length of flagella associated with the bacteria. These observations provide evidence that low-speed centrifugal transfer of cells to SB, exposure to uranyl acetate, and subsequent drying normally resulted in relatively little breakage of flagella or large-distance separation of flagella from their cell of origin. About 10 to 15% of the cells on the grids were present in clumps of five or more cells. Abundant flagella were usually seen in association with the clumped cells, possibly indicating a tendency for flagellated cells to adhere to each other. The cells present in such clumps were not included in counts of flagellated cells since it was not easy to distinguish between individual cells with and without flagella in such clumps.

The reliability of this direct counting method for determining flagellated-cell percentages was tested by mixing a suspension of L5-30 containing a high percentage of flagellated cells (i.e., freshly transferred to SB) with a suspension containing a low percentage of flagellated cells (i.e., 20 h after transfer to SB). The percentage of flagellated cells counted in the mixture was in close (±3%) agreement with the percentage predicted from counts of the two initial suspensions. Flagellated-cell percentages determined from duplicate grids were usually found to agree within 5%, indicating that the method is quantitatively reproducible.

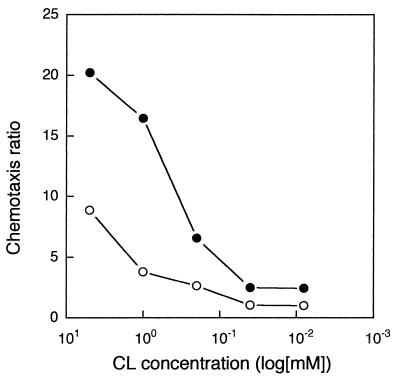

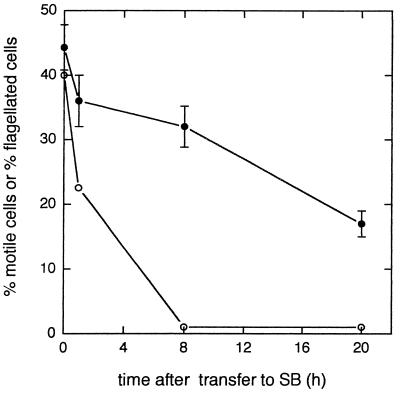

After suspension of L5-30 cells in starvation medium, the percentage of cells with flagella decreased gradually from about 45% to about 32% over an 8-h period (Fig. 4). The percentage of visibly motile cells, however, decreased from about 40% to essentially zero during this same period. Most of the L5-30 cells that retained flagella after several hours of starvation did not have the normal number of full-length flagella. Indeed, many retained only a short (0.5- to 1.0-μm) remnant of a single flagellum. About one-third of the flagellated cells in 8-h, nonmotile suspensions of L5-30, however, retained two or more full-length flagella. A similar proportion of flagellated cells in suspensions of L5-30 starved for 20 h or more had two or more full-length flagella, even though the overall percentage of flagellated cells dropped to 15 to 20%. Strains RMB7201 and JJ1c10 behaved similarly: a relatively high proportion (30%) of the cells from nonmotile suspensions of these strains, starved for 24 to 48 h, still retained flagella, and a considerable fraction (approximately one-third) of these flagellated cells had two or more long flagella.

FIG. 4.

Retention of motility and flagella by strain L5-30 after transfer to SB. Cells were transferred to SB and then assayed at various times for the percentage of motile cells (○) and the percentage of flagellated cells (•) as described in Materials and Methods. The results are representative of two independent experiments.

Effects of glucose, glutamine, culture filtrates, and nonmetabolizable chemoattractants on retention of motility and reversal of motility loss.

As shown in Table 1, the addition of 5 mM glucose, glutamine, or cycloleucine to the SB used to wash and resuspend the initial cultures of L5-30 resulted in an almost complete retention of motility for a period of several hours. The addition of 0.05 mM cycloleucine was just as effective as 5 mM cycloleucine in blocking motility loss. The addition of 5 mM itaconic acid, another nonmetabolizable (but weaker) chemoattractant, was also effective in blocking the loss of motility during starvation but did so only about half as well as cycloleucine. L5-30 cells washed and resuspended in SB containing either glucose or one of the nonmetabolizable attractants did not grow, and they gradually lost motility after the first few hours. Cells washed and resuspended in SB containing glutamine, which provides both N and C for growth, were able to multiply and maintained motility for longer periods of time. L5-30 cells resuspended in SB containing one-fifth-strength culture filtrate from 3-day-old stationary-phase cultures of L5-30, RMB7201, or JJ1c10 grown in NM-succinate defined medium also retained essentially full motility for several hours.

TABLE 1.

Motility of R. meliloti L5-30 after transfer to SB containing an added nutrient, culture filtrate, or nonmetabolizable attractant

| Added substance (concn) | % Motile cells after incubation in supplemented SB for period of (min)a:

|

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 20 | 30 | 40 | 60 | 90 | 120 | 180 | |

| No addition | 38 | 25 | 20 | 18 | 16 | 15 | 12b | 10b |

| Nutrient | ||||||||

| Glucose (5 mM) | 45 | 55 | NDc | 60 | ND | 60 | ND | 60 |

| Glutamine (5 mM) | 60 | 60 | ND | 60 | ND | 60 | ND | 60 |

| Attractant | ||||||||

| Cycloleucine (5 mM) | 60 | 60 | ND | 60 | ND | 60 | ND | 60 |

| Cycloleucine (50 μM) | 55 | 55 | ND | 60 | ND | 60 | ND | 60 |

| Itaconate (5 mM) | 35 | 35 | ND | 35 | ND | 40 | ND | 30 |

| Culture filtrate | ||||||||

| L5-30 | 75 | ND | 75 | ND | 75 | 75 | 75 | ND |

| JJ1c10 | 75 | ND | 80 | ND | 80 | 80 | 80 | ND |

| 7201 | 65 | ND | 65 | ND | 65 | 65 | 65 | ND |

Percentages are from single representative experiments that were repeated two or three times.

Motile cells tumbled slowly; few swam straight.

ND, not determined.

Because the loss of motility induced by starvation could be prevented by the addition of either a nonmetabolizable attractant or an energy-C source such as glucose, it was of interest to determine if these substances could reverse the loss of motility after a period of starvation. Cells of L5-30 were washed and resuspended in SB and incubated for either 1.5 or 8 h, so that the visible motility of the suspensions was reduced by 50 or 98%, respectively. Then either glucose, cycloleucine, or both were added to a concentration of 5 mM. As seen in Table 2, delayed additions of glucose and cycloleucine were able to restore the motility of starving L5-30 cells to some extent. Both the glucose and glucose-cycloleucine additions quickly restored the motility of 1.5-h-starved cells to full, prestarvation levels of normal swimming activity (Table 2). The addition of cycloleucine alone appeared to activate a comparable number of nonmotile cells, but their motility was largely restricted to circling and tumbling activity, with little evidence of straight swimming. When glucose and cycloleucine were added to L5-30 cells which had been starved for 8 h and had lost ca. 98% of their motility, it took 1 h or more for the added compounds to have any appreciable effect on motility. Restoration of motility, even after 6 to 12 h, was only partial, particularly in terms of straight swimming activity (Table 2). In similar experiments with strain JJ1c10, the addition of cycloleucine to suspensions which had been starved for 24 h in SB and had lost about 50% of their motility was found to immediately, though modestly, increase the percentage of motile cells and the number that entered cycloleucine-filled capillaries. The addition of cycloleucine 24 h after transfer did not prevent the cell motility from gradually decreasing over the next 24 h of starvation. When glucose was added to these 24-h-starved JJ1c10 suspensions, the cells were found to clump in large aggregates within a few hours, so motility could not be assessed.

TABLE 2.

Restoration of motility to starved cells by addition of glucose and/or cycloleucine

| Strain | Time starved before addition (h) | Time elapsed after addition (h) | % Motile cells with compound(s)a:

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| None | Glc | CL | Glc+CL | |||

| L5-30 | 1.5 | 0 | 20 | 40 | 40 | 48 |

| 1.5 | 0.5 | 8 | 42 | 40 | 50 | |

| 1.5 | 2 | 5 | 50 | 35 | 55 | |

| 1.5 | 4 | 2 | 48 | 30 | 50 | |

| 1.5 | 8 | 0 | 26 | 23 | 28 | |

| 8 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 3 | 5 | |

| 8 | 0.5 | 0 | 4 | 3 | 5 | |

| 8 | 1 | 0 | 14 | 8 | 16 | |

| 8 | 2 | 0 | 14 | 8 | 16 | |

| 8 | 3 | 0 | 23 | 13 | 26 | |

| 8 | 14.5 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 10 | |

| JJ1C10 | 24 | 0 | 35 | —b | 38 | — |

| 24 | 2 | 35 | — | 38 | — | |

| 24 | 8 | 25 | — | 35 | — | |

| 24 | 24 | 15 | — | 23 | — | |

Glc, glucose; CL, cycloleucine.

—, glucose caused cell clumping of strain JJ1c10; hence, the data are not reported.

DISCUSSION

Starvation-induced changes in chemotactic responsiveness.

All three strains of R. meliloti studied here showed increased but transiently expressed chemotactic responsiveness during starvation. Enhanced chemotactic responsiveness may represent a general starvation response by which motile bacteria increase their probability of finding new nutrient supplies without committing internal reserves to continued flagellar synthesis or motor activity. The molecular mechanisms involved in the chemotactic-sensitivity facet of R. meliloti’s starvation response are unknown. In starving R. meliloti cells, enhanced responsiveness does not appear to involve significant changes in either the threshold of or the optimal concentration for responses to attractants (Fig. 3). Since starving R. meliloti cells exhibit increased responsiveness to cycloleucine, a nonmetabolizable attractant, we conclude that this organism’s enhanced responsiveness to attractants does not require exposure to new nutrient or energy supplies. It is not clear why, or even whether, the increased responsiveness of R. meliloti is transient. It is quite possible that responsiveness per se remains at a high level during prolonged starvation and that the reduction in entry into attractant-filled capillaries simply reflects reduced motility.

Regulation of motility in response to starvation.

In general, the motility of R. meliloti cells was down regulated during starvation. Both flagellar maintenance and motor activity seemed to be affected. The bacteria lost flagella as a result of starvation, but this loss of flagella could not fully account for the extensive loss of motility during the initial phases of the starvation response (Fig. 4), and many of the nonmotile cells in starving cultures retained flagella. We conclude that one of the first responses of R. meliloti to starvation is to turn off the rotation of flagellar motors in certain cells. Flagellar-motor activity in R. meliloti is reported to alternate between an “on” state and an “off” state during normal swimming behavior (13). Similar behavior, with considerably longer pauses between swims, is seen in the related, uniflagellate species Rhodobacter sphaeroides (33). We speculate that starvation may progressively increase the proportion of time that the individual flagellar motors of a cell spend in the off state. If so, then one would predict that the time intervals that cells spend in straight swimming would gradually decrease, that the average swimming speed would also gradually decrease, and that the frequency of directional changes would correspondingly increase. Later during starvation, the probability that all flagellar motors on a given cell are off at the same time would become appreciable and the cells would stop moving altogether for brief periods. Finally, the proportion of flagellated cells that stay at rest for extended time periods would increase to 100%. Our videomicroscopic observations of motility are consistent with this starvation response model. After a period of starvation sufficient to reduce the percentage of motile cells to ca. 20% of their initial level, those cells that remained motile often stopped moving altogether for periods of time ranging from about 0.5 s to several seconds. Unstarved cells rarely, if ever, stopped moving for more than a small fraction of a second. The possibility that an increased amount of time in the off position is a starvation-induced response seems in accord with the increased proportion of time that E. coli flagellar motors were reported to spend in the inactive, pausing mode in suspensions without nutrients as opposed to suspensions with added glycerol (18).

The switching off of flagellar-motor activity in response to starvation seems to be at least partially reversible in all three strains tested. The reactivation of motor activity in starved L5-30 cells by added attractants was effectively instantaneous during the first 1.5 h after transfer to SB but required 1 h or more when glucose or cycloleucine was added after 8 h of starvation (Table 2). It remains to be determined how the cells changed between 1.5 and 8 h of starvation to prevent the full and rapid reactivation of flagellar-motor activity. Access to a carbon or energy source was the main limiting factor in reactivation of motility in cells starved for an extended period. However, the appreciable reactivation of motor activity by cycloleucine alone (Table 2) indicates that the binding of a receptor to a nonmetabolite can be an important contributor to reactivation, even if it is not sufficient to restore normal swimming behavior. It will be of interest to learn whether one of the recently described MotC or MotD proteins (23), which have no counterparts in E. coli, might serve as a receptor for signals corresponding to energy sources or attractants that would subsequently regulate flagellar-motor activity.

In contrast to L5-30 and RMB7201, strain JJ1c10 remained fairly responsive to reactivation by chemoattractants even after 48 to 100 h of starvation (Fig. 2; Table 2). Such differences between strain JJ1c10 and the other two strains in the reactivatability of flagellar motors, as well as the different periods of starvation required to reduce motility to half-maximal or zero levels for the three strains (Fig. 1), suggest that all three strains of R. meliloti have adopted somewhat different, genetically programmed patterns of behavioral response to starvation. Strain JJ1c10 appears to be significantly more committed to sustained motility and chemotactic responsiveness than either L5-30 or RMB7201. Perhaps as a consequence, strain JJ1c10 loses viability (or enters a viable but nonculturable state) significantly faster than the other two strains under conditions of prolonged starvation, at least in vitro.

Loss of flagella in response to starvation.

In general, when R. meliloti cells were starved long enough to bring visible motility to essentially zero, roughly half of the flagellated cells retained only short lengths of just one or two flagella. It is likely that cells with only one or two truncated flagella are incapable of normal, smooth forward swimming. Thus, the progressive loss and disintegration of flagella on many of the cells may help to explain why most of those cells which remained visibly motile only circled, twitched, or tumbled slowly. Frequent or extended pausing by some individual flagella on a cell with several flagella might also result in such aberrant swimming behavior (13, 28).

However, even in extensively starved suspensions in which no swimming or even slowly spinning cells were detected, about one-third of the flagellated cells of all three strains appeared to retain a normal number of full-length flagella. In electron micrographs, such cells were indistinguishable from flagellated cells taken from actively growing cultures. We conclude that the loss and disintegration of flagella occur in just a selected subpopulation of the cells. The molecular mechanisms behind this selective loss or retention of flagella in certain subpopulations of this bacterium remain to be determined. The cell-specific, starvation-induced regulation of flagellar loss on the one hand and of flagellar-motor activity on the other hand appears to result in the production of five distinct subpopulations: (i) cells that have lost all of their flagella and are nonmotile, (ii) cells that retain normal numbers of intact flagella and have active flagellar motors, (iii) cells that retain normal numbers of intact flagella but have inactive flagellar motors, (iv) cells that have lost most of their flagella but have active flagellar motors, and (v) cells that have lost most of their flagella and have inactive flagellar motors. After prolonged starvation, only the first, third, and fifth subpopulations of cells remain. It would be of considerable interest to know whether the different subpopulations generated by these two kinds of starvation response each have some kind of selective advantage in surviving starvation under natural environmental circumstances (5).

Retention of motility during starvation.

The loss of motility in L5-30 cells following transfer to starvation medium could be prevented or minimized for an extended period by the addition of an attractant to the starvation medium during transfer (Table 1). The extent to which this loss of motility was prevented seemed to be determined by how strongly the attractant elicited tactic responses and not by whether the attractant was metabolizable or by its concentration per se. Substances present in the filtrates from stationary-phase cultures of R. meliloti had similar abilities to prevent motility loss during starvation. Presumably the active substances in these culture filtrates were nonmetabolizable attractants, but other possibilities, including quorum-sensing autoinducers (10), remain open. From these observations, we conclude that the presence of chemoattractants can at least temporarily override the normal down regulation of behavioral activity in R. meliloti. Based on the effects of nonmetabolizable attractants like cycloleucine and itaconic acid, the ability of chemoattractants to override starvation-induced down regulation of motility seems to be independent of any energy or nutrient input from the attractant. Thus, the interaction of such chemoattractants with their receptors would seem to provide one important input to the regulation of behavioral activity under starvation conditions. A second, independent part of such regulation undoubtedly involves nutrient-energy sensing and its connections to flagellar maintenance and motor activity. Further studies at both the molecular genetic and ecological levels are needed to understand how bacteria regulate their patterns of behavioral activity when faced with starvation.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The assistance of Elke Kretschmar and Robert Whitmoyer in the use of the electron microscope is much appreciated, as is the advice of Catherine Wolkin regarding methods for flagellar staining. We thank John Parkinson for valuable suggestions and John Streeter, Michael Boehm, and Jayne Robinson for critical reading of the manuscript and helpful comments.

Partial support for salaries, supplies, and publication costs was provided by state and federal funds appropriated to the Ohio Agricultural Research and Development Center, Ohio State University.

Footnotes

Ohio Agricultural Research and Development Center manuscript number 136-97.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ames P, Bergman K. Competitive advantage provided by bacterial motility in the formation of nodules by Rhizobium meliloti. J Bacteriol. 1981;148:728–729. doi: 10.1128/jb.148.2.728-729.1981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ames P, Schluederberg S A, Bergman K. Behavioral mutants of Rhizobium meliloti. J Bacteriol. 1980;141:722–727. doi: 10.1128/jb.141.2.722-727.1980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Amy P S, Morita R Y. Starvation-survival patterns of sixteen freshly isolated open-ocean bacteria. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1983;45:1109–1115. doi: 10.1128/aem.45.3.1109-1115.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bergman K, Gulash-Hoffee M, Hovestadt R E, Larosiliere R C, Ronco II P G, Su L. Physiology of behavioral mutants of Rhizobium meliloti: evidence for a dual chemotaxis pathway. J Bacteriol. 1988;170:3249–3254. doi: 10.1128/jb.170.7.3249-3254.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bewley W F, Hutchinson H B. On the changes through which the nodule organism (Ps. radicicola) passes under cultural conditions. J Agric Sci. 1920;10:144–162. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Boyer H W, Roulland-Dussoix D. A complementation analysis of the restriction and modification of DNA in Escherichia coli. J Mol Biol. 1969;41:459–472. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(69)90288-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Caetano-Anollés G, Wall L G, De Micheli A T, Macchi E M, Bauer W D, Favelukes G. Role of motility and chemotaxis in efficiency of nodulation by Rhizobium meliloti. Plant Physiol. 1988;86:1228–1235. doi: 10.1104/pp.86.4.1228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Caetano-Anollés G, Crist-Estes D K, Bauer W D. Chemotaxis of Rhizobium meliloti to the plant flavone luteolin requires functional nodulation genes. J Bacteriol. 1988;170:3164–3169. doi: 10.1128/jb.170.7.3164-3169.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dharmatilake A J, Bauer W D. Chemotaxis of Rhizobium meliloti towards nodulation gene-inducing compounds from alfalfa roots. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1992;58:1153–1158. doi: 10.1128/aem.58.4.1153-1158.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Eberl L, Winson M K, Sternberg C, Stewart G S, Christiansen G, Chabra S R, Wycroft B, Williams P, Molin S, Givskov M. Involvement of N-acyl-l-hormoserine lactone autoinducers in controlling the multicellular behaviour of Serratia liquefaciens. Mol Microbiol. 1996;20:127–136. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1996.tb02495.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Geesey G G, Morita R Y. Capture of arginine at low concentrations by a marine psychrophilic bacterium. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1979;38:1092–1097. doi: 10.1128/aem.38.6.1092-1097.1979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Götz R, Limmer N, Ober K, Schmitt R. Motility and chemotaxis in two strains of Rhizobium with complex flagella. J Gen Microbiol. 1982;128:789–798. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Götz R, Schmitt R. Rhizobium meliloti swims by unidirectional, intermittent rotation of right-handed flagellar helices. J Bacteriol. 1987;169:3146–3150. doi: 10.1128/jb.169.7.3146-3150.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gulash M, Ames P, Larosiliere R C, Bergman K. Rhizobia are attracted to localized sites on legume roots. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1984;48:149–152. doi: 10.1128/aem.48.1.149-152.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hankinson T R, Sweeney P E, Gudbrandsen S M, Ronson C W. Population behavior of genetically engineered Rhizobium meliloti in an open-air field trial. In: Gresshoff P, Stacey G, Newton W, editors. Nitrogen fixation: achievements and objectives. New York, N.Y: Chapman & Hall; 1990. pp. 397–403. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Herrero M, de Lorenzo V, Timmis K N. Transposon vectors containing non-antibiotic resistance selection markers for cloning and stable chromosomal insertion of foreign genes in gram-negative bacteria. J Bacteriol. 1990;172:6557–6567. doi: 10.1128/jb.172.11.6557-6567.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Krupski G, Götz R, Ober K, Pleier E, Schmitt R. Structure of complex flagellar filament in Rhizobium meliloti. J Bacteriol. 1985;162:361–366. doi: 10.1128/jb.162.1.361-366.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lapidus I R, Welch M, Eisenbach M. Pausing of flagellar rotation is a component of bacterial motility and chemotaxis. J Bacteriol. 1988;170:3627–3632. doi: 10.1128/jb.170.8.3627-3632.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Macnab R M. Flagella and motility. In: Neidhardt F C, Curtiss III R, Ingraham J L, Lin E C C, Low K B, Magasanik B, Reznikoff W S, Riley M, Schaechter M, Umbarger H E, editors. Escherichia coli and Salmonella: cellular and molecular biology. 2nd ed. Washington, D.C: ASM Press; 1996. pp. 123–145. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Malmcrona-Friberg K, Goodman A, Kjelleberg S. Chemotactic responses of marine Vibrio sp. strain S14 (CCUG 15956) to low-molecular-weight substances under starvation and recovery conditions. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1990;56:3699–3704. doi: 10.1128/aem.56.12.3699-3704.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Maruyama M, Lodderstaedt G, Schmitt R. Purification and biochemical properties of complex flagella isolated from Rhizobium lupini H13-3. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1978;535:110–114. doi: 10.1016/0005-2795(78)90038-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Palleroni N J. Taxonomy of pseudomonads. In: Sokatch J R, editor. The bacteria: the biology of pseudomonads. New York, N.Y: Academic Press; 1986. pp. 3–20. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Platzer J, Sterr W, Hausmann M, Schmitt R. Three genes of a motility operon and their role in flagellar rotary speed variation in Rhizobium meliloti. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:6391–6399. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.20.6391-6399.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Robinson J B, Tuovinen O H, Bauer W D. Role of divalent cations in the subunit associations of complex flagella from Rhizobium meliloti. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:3896–3902. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.12.3896-3902.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Robinson J B, Bauer W D. Relationships between C4 dicarboxylic acid transport and chemotaxis in Rhizobium meliloti. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:2284–2291. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.8.2284-2291.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schuster S C, Khan S. The bacterial flagellar motor. Annu Rev Biophys Biomol Struct. 1994;23:509–539. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bb.23.060194.002453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Segal L A, Chet I, Henis Y. A simple quantitative assay for bacterial motility. J Gen Microbiol. 1977;98:320–337. doi: 10.1099/00221287-98-2-329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sourjik V, Schmitt R. Different roles of CheY1 and CheY2 in the chemotaxis of Rhizobium meliloti. Mol Microbiol. 1996;22:427–436. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1996.1291489.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Stock J B, Surette M G. Chemotaxis. In: Neidhardt F C, Curtiss III R, Ingraham J L, Lin E C C, Low K B, Magasanik B, Reznikoff W S, Riley M, Schaechter M, Umbarger H E, editors. Escherichia coli and Salmonella: cellular and molecular biology. 2nd ed. Washington, D.C: ASM Press; 1996. pp. 1103–1129. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Terracciano J S, Canale-Parola E. Enhancement of chemotaxis in Spirochaeta aurantia grown under conditions of nutrient limitation. J Bacteriol. 1984;159:173–178. doi: 10.1128/jb.159.1.173-178.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Torrella F, Morita R Y. Microcultural study of bacterial size changes and microcolony and ultramicrocolony formation by heterotrophic bacteria in seawater. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1981;41:518–527. doi: 10.1128/aem.41.2.518-527.1981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Torrella F, Morita R Y. Starvation induced morphological changes, motility, and chemotaxis patterns in a psychrophilic marine vibrio. Publ Cent Natl Exploit Oceans Actes Colloq. 1982;13:45–60. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ward M J, Bell A W, Hamblin P A, Packer H L, Armitage J P. Identification of a chemotaxis operon with two cheY genes in Rhodobacter sphaeroides. Mol Microbiol. 1995;17:357–366. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1995.mmi_17020357.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Watson R J, Chan Y-K, Wheatcroft R, Yang A-F, Han S. Rhizobium meliloti genes required for C4-dicarboxylate transport and symbiotic nitrogen fixation are located on a megaplasmid. J Bacteriol. 1988;170:927–934. doi: 10.1128/jb.170.2.927-934.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wrangstadh M, Szewzyk U, Östling J, Kjelleberg S. Starvation-specific formation of a peripheral exopolysaccharide by a marine Pseudomonas sp., strain S9. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1990;56:2065–2072. doi: 10.1128/aem.56.7.2065-2072.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]