Abstract

Background and Objectives:

Diagnosing skin disorders is a core skill in family medicine residency. Accurate diagnosis of skin cancers has a significant impact on patient health. Dermoscopy improves a physician’s accuracy in diagnosing skin cancers. We aimed to quantify the current state of dermoscopy use and training in family medicine residencies.

Methods:

We included questions on dermoscopy training in the 2021 Council of Academic Family Medicine Educational Research Alliance (CERA) survey of family medicine residency program directors. The survey asked about access to a dermatoscope, the presence of faculty with experience using dermoscopy, the amount of dermoscopy didactic time, and the amount of hands-on dermoscopy training.

Results:

Of 631 programs, 275 program directors (43.58% response rate) responded. Half of the responding programs (50.2%) had access to a dermatoscope, and 54.2% had a faculty member with experience using dermoscopy. However, only 6.8% of residents had 4 or more hours of didactics on dermoscopy over their entire training. Only 16.2% had 4 or more hours of hands-on dermoscopy use. Over half (58.9%) of programs planned to add more dermoscopy training. We did not find any correlations between the program’s size/type/location and dermoscopy training opportunities.

Conclusions:

Despite reasonable access to a dermatoscope and the presence of at least one faculty member with dermoscopy experience, most family medicine residency programs provided limited dermoscopy training opportunities. Research is needed to better understand how to facilitate dermoscopy training in family medicine residencies.

INTRODUCTION

Skin conditions are some of the most commonly seen problems in family medicine, comprising 8% of all visits to family physicians.1 The evaluation of suspected skin cancer is a core primary care skill, but the ABCD (asymmetry, border irregularity, color variegation, diameter>6 mm) clinical tool can miss up to two-thirds of melanomas.2 Melanoma accounts for nearly 8,000 deaths each year in the United States.3 The annual cost of treating new melanomas is estimated to increase from $457 million in 2011 to $1.6 billion in 2030.4 Dermoscopy uses a handheld device to magnify and examine structures in the deeper layers of the skin. There is strong evidence that the use of dermoscopy improves the accuracy of melanoma and basal cell carcinoma diagnosis and allows for earlier detection (strength of recommendation, A).5, 6 Family physicians find more skin cancers and biopsy fewer benign lesions after developing competency in using a dermatoscope.7 Dermoscopy training typically includes didactic and interactive training modalities. When family physicians use dermoscopy routinely, melanoma diagnostic accuracy improves.6, 8, 9 Despite this, the overall use of dermoscopy by practicing family physicians remains low.10

The American Academy of Family Physicians (AAFP) “Recommended Curriculum Guidelines for Family Medicine Residents” includes dermoscopy under its required skills.11 Evidence about dermoscopy training in US dermatology residencies exists,12, 13, 14 but it has not been researched in US family medicine residencies. This study aimed to assess current availability of dermatoscopes and dermoscopy-trained faculty in family medicine residencies along with the amount of dermoscopy didactics and hands-on teaching.

METHODS

The AAFP IRB-approved Council of Academic Family Medicine Educational Research Alliance (CERA) survey was sent to family medicine residency program directors between September 14, 2021 and October 8, 2021, with cleared data reported to the authors in November 2021. CERA further validated respondent information about current program status and fulfilling criteria for completing the survey. CERA survey and methodology have been previously described. 15

We analyzed the data with SPSS software using descriptive statistics to evaluate survey respondents and answers to the survey. Using a χ2 test, we further analyzed for correlations between program characteristics and the presence and extent of dermoscopy training. The program characteristics included program location, size, type, and community size.

RESULTS

Six hundred thirty-one verified family medicine residency program directors received the survey, with 275 (43.6%) answering all questions.

Descriptive Statistics

Most respondents (57.8%) were from community-based, university-affiliated programs (see Table 1 ). The program director respondents were equally distributed by program location, size of the community in which the residency was located, and size of the residency program itself.

Table 1. Characteristics of Family Medicine Residency Programs Whose Program Directors Responded to Dermoscopy Survey Items.

|

Characteristic, n=275 |

n (%) |

|

Type of Program |

|

|

Community-based, university-affiliated |

159 (57.8) |

|

Community-based, nonaffiliated |

61 (22.2) |

|

University-based |

46 (16.7) |

|

Military |

3 (1.1) |

|

Other |

6 (2.2) |

|

Region Where Program Is Located |

|

|

New England |

11 (4) |

|

Middle Atlantic |

40 (14.5) |

|

South Atlantic |

37 (13.5) |

|

East South Central |

14 (5.1) |

|

East North Central |

50 (18.2) |

|

West South Central |

29 (10.5) |

|

West North Central |

23 (8.4) |

|

Mountain |

28 (10.2) |

|

Pacific |

43 (15.6) |

|

Program Size |

|

|

Small program (<19 residents) |

121 (44.0) |

|

Medium program (19-31 residents) |

112 (40.7) |

|

Large program (>31 residents) |

42 (15.3) |

|

Community Size (population) |

|

|

<30,000 |

33 (12.1) |

|

30,000- 74,999 |

37 (13.6) |

|

75,000-149,000 |

60 (22.0) |

|

150,000-499,999 |

70 (25.6) |

|

500,000-1,000,000 |

31 (11.4) |

|

> 1 million |

42 (15.4) |

Training Aspects

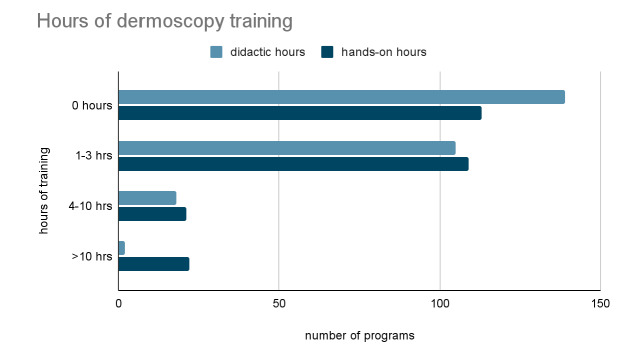

Half (50.2%) of responding programs reported having access to a dermatoscope, with just over half (54.9%) reporting having a faculty with dermoscopy experience (Table 2). Only 38.3% of programs reported providing didactic dermoscopy education, and the vast majority (93.6%) provided only 0-3 total hours of didactic instruction during the entire residency training. Additionally, 42.6% of responding programs provided no hands-on dermoscopy training, and 41.1% gave just 1-3 hours of hands-on training (Figure 1). Overall, 58.9% of programs reported the intention to add more dermoscopy training in the future.

Table 2. Access to Dermatoscopes and Dermoscopy Training.

|

n=275 |

n (%) |

|

Does your program provide access to a dermatoscope? |

|

|

No |

133 (49.8) |

|

Yes |

134 (50.2) |

|

Does your program have faculty with experience using dermoscopy? |

|

|

No |

103 (38.4) |

|

Yes |

147 (54.9) |

|

I don’t know |

18 (6.7) |

|

In your didactic curriculum, do you provide dermoscopy education? |

|

|

No |

153 (57.5) |

|

Yes |

102 (38.3) |

|

I don’t know |

11 (4.1) |

|

Over what time frame do you intend to add more dermoscopy training to your program’s curriculum? |

|

|

No current intention to add |

109 (41.1) |

|

Within a year |

57 (21.5) |

|

<3 years |

41 (15.5) |

|

Intend but are unsure when |

58 (21.9) |

Figure 1 . Hours of Didactic and Hands-On Dermoscopy Training.

Summary of Subanalysis

Chi-square–test correlations were not significant between program characteristics and the presence of a dermatoscope, faculty with dermoscopy training, or hours of dermoscopy training.

DISCUSSION

Our study is the first published study assessing dermoscopy training in family medicine residencies. It is unexpected that over 50% of the responding programs have access to a dermatoscope and have at least one faculty with experience using dermoscopy. Previous surveys of primary care physicians in the United States showed only 8-16% performed dermoscopy.9, 14 In our study, only 38% of the respondents included dermoscopy education in their curriculum, and of those, the vast majority had less than 3 total didactic hours in a year. The prevalence of hands-on dermoscopy training was similarly low despite being the preferred learning method for dermoscopy by PCPs.16 The discrepancy between a higher-than-expected prevalence of faculty with experience using dermoscopy and lack of dermoscopy education may be due to dermoscopy experience not corresponding with sufficient expertise to train residents.

Most of the program directors surveyed in our study intend to add dermoscopy training in the future, which aligns with a 2020 study that showed most PCPs would like to learn dermoscopy.14 Lack of device access followed by lack of training were the most common barriers to the use of dermoscopy in community primary care settings.16 Programs intent on adding dermoscopy training should consider purchase of a hybrid dermatoscope ($400-$1200). While the AAFP recommends including dermoscopy in residency education, it is unlikely to be routinely taught until required by the ACGME and tested on family medicine board exams. ACGME requirements and board exam emphasis increased motivation for learning and teaching dermoscopy in dermatology residencies. 17

Limitations of this study include the 43.6% overall response rate. Survey questions regarding faculty experience with dermoscopy required program directors to subjectively define experience. Thus, we do not know the extent to which dermoscopy is utilized by these faculty or their level of expertise. Additionally, program directors were estimating on responses such as hours of hand-on dermoscopy training provided. This study did not investigate barriers to teaching dermoscopy in family medicine residencies, which could be an area of future research. Further study could also delineate the percentage of primary care residents and faculty who use dermoscopy and their level of competency.

While more than half of responding programs have access to a dermatoscope and a faculty member with dermoscopy experience, most provide residents with little to no dermoscopy education and training. While the USPSTF has found insufficient evidence to recommend screening for skin cancer in all asymptomatic adults, dermoscopy remains an important and patient-centered tool for evaluating individual skin lesions of concern. Further research could better characterize the barriers to dermoscopy training in family medicine residencies and strategies for increasing its teaching and use in appropriate clinical settings.

Financial Support

DMH’s efforts were supported by NIH through the Michigan Institute for Clinical and Health Research UL1TR002240 and by NCI through The University of Michigan Rogel Cancer Center P30CA046592 grants.

Author Contributions

Miranda Lu: Conceptualization, methodology, writing—original draft, writing- Review and editing, visualization, supervision, project administrationRichard Usatine: conceptualization, methodology, writing—original draft, writing—review and editingJames Holt: Conceptualization, methodology, writing—original draft, writing—review and editingDiane Harper: Writing—review and editing, supervisionAlexandra Verdieck: Conceptualization, methodology, formal analysis, writing—original draft, writing—review and editing, visualization

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the assistance of Ashfaq Marghoob, MD, and Rebecca Rdesinski.

References

- 1.Awadalla F, Rosenbaum D A, Camacho F, Fleischer A B, Feldman S R. Dermatologic disease in family medicine. Fam Med. 2008;40(7):507–511. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Salerni G, Terán T, Alonso C, Fernández-Bussy R. The role of dermoscopy and digital dermoscopy follow-up in the clinical diagnosis of melanoma: clinical and dermoscopic features of 99 consecutive primary melanomas. Dermatol Pract Concept. 2014;4(4):39–46. doi: 10.5826/dpc.0404a07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Siegel R L, Miller K D, Fuchs H E, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2022. CA Cancer J Clin. 2022;72(1):7–33. doi: 10.3322/caac.21708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Guy G P, Thomas C C, Thompson T, Watson M, Massetti G M, Richardson L C. Vital signs: melanoma incidence and mortality trends and projections - United States. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 1982;64(21):591–596. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dinnes J, Deeks J J, Chuchu N. Cochrane Skin Cancer Diagnostic Test Accuracy Group. Visual inspection and dermoscopy, alone or in combination, for diagnosing keratinocyte skin cancers in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018;12(12):11901–11901. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD011901.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vestergaard M E, Macaskill P, Holt P E, Menzies S W. Dermoscopy compared with naked eye examination for the diagnosis of primary melanoma: a meta-analysis of studies performed in a clinical setting. Br J Dermatol. 2008;159(3):669–676. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2008.08713.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Seiverling E V, Ahrns H T, Greene A. Teaching benign skin lesions as a strategy to improve the triage amalgamated dermoscopic algorithm (TADA) J Am Board Fam Med. 2019;32(1):96–102. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.2019.01.180049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kittler H, Pehamberger H, Wolff K, Binder M. Diagnostic accuracy of dermoscopy. Lancet Oncol. 2002;3(3):159–165. doi: 10.1016/s1470-2045(02)00679-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bafounta M L, Beauchet A, Aegerter P, Saiag P. Is dermoscopy (epiluminescence microscopy) useful for the diagnosis of melanoma? results of a meta-analysis using techniques adapted to the evaluation of diagnostic tests. Arch Dermatol. 2001;137(10):1343–1350. doi: 10.1001/archderm.137.10.1343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Morris J B, Alfonso S V, Hernandez N, Fernández M I. Examining the factors associated with past and present dermoscopy use among family physicians. Dermatol Pract Concept. 2017;7(4):63–70. doi: 10.5826/dpc.0704a13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Recommended curriculum guidelines for family medicine residents: conditions of the skin. American Academy of Family Physicians. 2021 [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wu T P, Newlove T, Smith L, Vuong C H, Stein J A, Polsky D. The importance of dedicated dermoscopy training during residency: a survey of US dermatology chief residents. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;68(6):1000–1005. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2012.11.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Patel P, Khanna S, Mclellan B, Krishnamurthy K. The need for improved dermoscopy training in residency: a survey of US dermatology residents and program directors. Dermatol Pract Concept. 2017;7(2):17–22. doi: 10.5826/dpc.0702a03. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chen Y A, Rill J, Seiverling E V. Analysis of dermoscopy teaching modalities in United States dermatology residency programs. Dermatol Pract Concept. 2017;7(3):38–43. doi: 10.5826/dpc.070308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Seehusen D A, Mainous A G, Iii, Chessman A W. Creating a centralized infrastructure to facilitate medical education research. Ann Fam Med. 2018;16(3):257–260. doi: 10.1370/afm.2228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Williams N M, Marghoob A A, Seiverling E, Usatine R, Tsang D, Jaimes N. Perspectives on dermoscopy in the primary care setting. J Am Board Fam Med. 2020;33(6):1022–1024. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.2020.06.200238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fried L J, Tan A, Berry E G. Dermoscopy proficiency expectations for US dermatology resident physicians: results of a modified Delphi survey of pigmented lesion experts. JAMA Dermatol. 2021;157(2):189–197. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2020.5213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]