Abstract

Cancer is the primary and one of the most prominent causes of the rising global mortality rate, accounting for nearly 10 million deaths annually. Specific methods have been devised to cure cancerous tumours. Effective therapeutic approaches must be developed, both at the cellular and genetic level. Immunotherapy offers promising results by providing sustained remission to patients with refractory malignancies. Genetically modified T-lymphocytic cells have emerged as a novel therapeutic approach for the treatment of solid tumours, haematological malignancies, and relapsed/refractory B-lymphocyte malignancies as a result of recent clinical trial findings; the treatment is referred to as chimeric antigen receptor T-cell therapy (CAR T-cell therapy). Leukapheresis is used to remove T-lymphocytes from the leukocytes, and CARs are created through genetic engineering. Without the aid of a major histocompatibility complex, these genetically modified receptors lyse malignant tissues by interacting directly with the carcinogen. Additionally, the outcomes of preclinical and clinical studies reveal that CAR T-cell therapy has proven to be a potential therapeutic contender against metastatic breast cancer (BCa), triple-negative, and HER 2+ve BCa. Nevertheless, unique toxicities, including (cytokine release syndrome, on/off-target tumour recognition, neurotoxicities, anaphylaxis, antigen escape in BCa, and the immunosuppressive tumour microenvironment in solid tumours, negatively impact the mechanism of action of these receptors. In this review, the potential of CAR T-cell immunotherapy and its method of destroying tumour cells is explored using data from preclinical and clinical trials, as well as providing an update on the approaches used to reduce toxicities, which may improve or broaden the effectiveness of the therapies used in BCa.

Keywords: T-cell receptors, chimeric antigen receptor t-cell therapy, breast cancer, relapsed/refractory B-cell malignancies, B-lymphocyte non-Hodgkin lymphoma, cytokine release syndrome, neurotoxicity, anaphylaxis, US Food and Drug Administration, clinical trial

1. Introduction

The complex and diverse group of disorders collectively referred to as malignant cancer is characterised by the dissemination and proliferation of aberrant cells in the body. Physiologically normal cells undergo a systematic process of growth, division and apoptosis, or programmed cell death, to reach senescence. In contrast, cancer cells proliferate aggressively, giving rise to malignant tumours that can invade and destroy adjacent tissues and organs by spreading through the bloodstream or lymphatic system (1). Numerous variables can contribute to the development of malignancies, including genetic alterations, exposure to carcinogens such as tobacco smoke or UV radiation, and dietary and lifestyle choices (2). While various treatment methods, including surgery, radiation therapy, and chemotherapy, are available for different types of malignancies, the primary challenge lies in revolutionising the diagnosis and prognosis of cancer at both the cellular and genetic levels (3). In the late 19th century, surgeon William Coley observed that certain cancer patients suffering from bacterial infections experienced spontaneous cancer remission. This observation led Coley to inject heat-killed Streptococcus pyogenes and S. marcescens into cancer patients to boost their immune systems. Although the results were mixed, his work laid the foundation for modern immunotherapy (4). In the 1890s, Paul Ehrlich delved deeper into the concept that the immune system is capable of detecting and eliminating malignant cells. He laid the groundwork for active and passive immunity, a concept he later referred to as 'cancer immunity' (5). Research at the National Cancer Institute by Rosenberg (6) explored the efficacy of interleukin-2 (IL-2) in stimulating cell growth and combating cancerous cells. The development and advances of cancer immunotherapy gained notable momentum following the development of the first monoclonal antibody (mAb), rituximab, for treating non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL) in 1997. Monoclonal antibodies are one of the three adoptive cell transfer (ACT) therapies used for diagnosing malignancies and for prognostic evaluation (7,8). For example, subcutaneous FBL3 lymphomas were lysed by infusing IL-2 intravenously. Studies also investigated the use of genetically altered T-lymphocytes to target tumour antigens (6,9). After a decade of studies and trials, Eshhar et al (10) developed a genetically engineered therapy using chimeric proteins that could recognize and target specific malignant antigens expressed on T-cells. This therapy is known as chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell therapy. The process involves leukapheresis, a procedure used to isolate T-lymphocytes from a patient's leukocytes, followed by the infusion of genetically altered CARs into the patient's circulatory system. Over a decade of successful innovations, CARs have evolved, incorporating different domains and co-stimulatory, elements that enhance their ability to bind to cancerous cells and tissues, facilitating the lysis of cancerous cells. This evolution has led to CAR T-cell therapy becoming a novel therapeutic option for conditions such as multiple myeloma (MM), B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukaemia (B-ALL), and other aggressive tumours (11,12). Recent achievements in CAR T-cell therapy, driven by molecular and immunological insights, provide the foundation for its advancement as a more efficient and precise therapeutic approach. These advances are further discussed in the following sections.

2. Requirements for CAR T-cell development

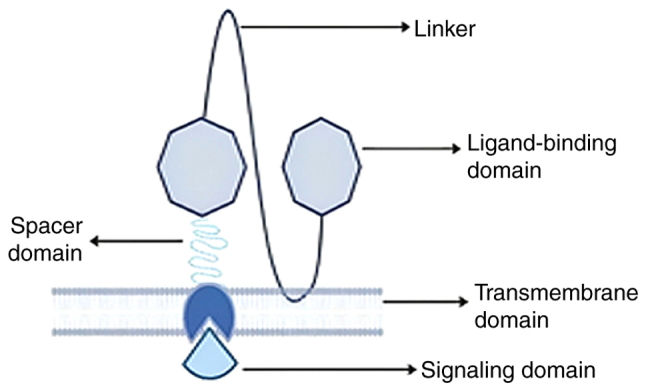

The demand for T-cell receptors (TCRs) in curing metastatic melanoma, was unparalleled due to their remarkable efficacy. However, their success as a therapeutic option was accompanied by a series of adverse side effects including off-target toxicity, cardiac toxicity, neurological toxicities, and various other life-threatening complications, which led to the exploration of neoantigens as a potentially safer approach (13,14). The introduction of CAR T-cell therapy ushered in cutting-edge technologies across various disciplines, including immunogenetics, molecular genetics, and oncogenetics. This approach involves the use of protein receptors known as chimeric T-lymphocytic receptors, which have evolved to enable T-cells to precisely target specific antigens. Their ability to combine components for T-cell activation and antigen binding justifies the term 'chimeric' being applied to them (15,16). The basic structural composition of CAR includes the extracellular domain (also referred to as the target and spacer motif), the transmembrane motif, and a signalling motif. Each of these domains significantly influences anti-carcinogenic effectiveness and CAR T-cell production (15).

3. Characterisation of the CAR domains

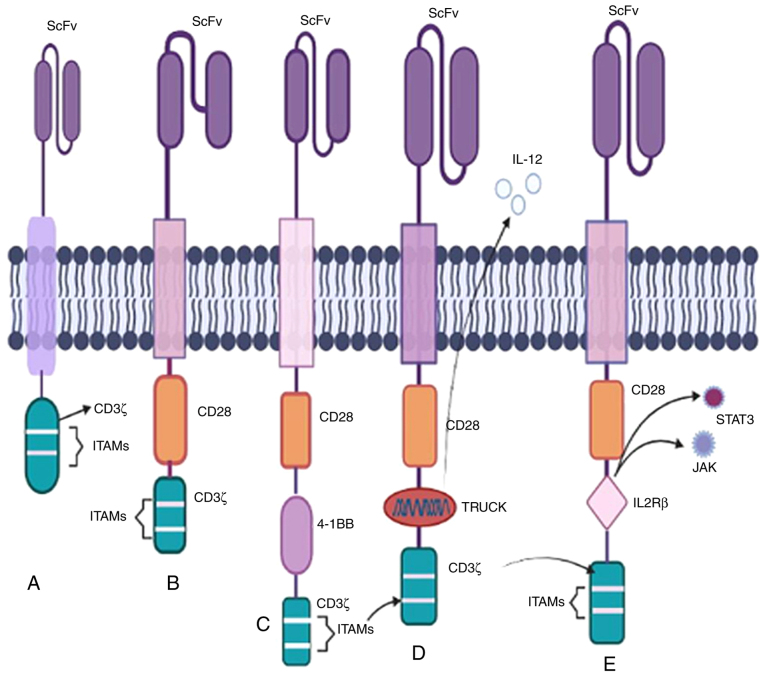

Ligand-binding domain

The targeting domain, also known as the ligand-binding domain, primarily consists of a fragment called single-chain variable fragment (ScFv) (Fig. 1), produced from non-human sequences found in mABs capable of eliciting immunogenic responses. Theoretically, ScFv can recognise a wide range of surface antigens expressed on target cells (such as HER2, PSMA, and CD19) (15,17). In addition, other domains incorporate nanobodies and receptor-cognate ligands, such as NKG2D, IL-2R, IL-7R, T1E, and PD-1, to target multiple ligands (18,19). Certain cases have reported potent anti-tumour activity with ScFv, which, however, can lead to neurotoxicity and could potentially be resolved through the optimisation of ligand-binding affinities (20).

Figure 1.

Chimeric antigen receptors are composed of a signalling motif, a transmembrane motif, a spacer motif, and a ligand-binding motif.

Spacer domain

To provide flexibility to the recognition sites of CAR T-cells, the spacer domain connects ScFv to the transmembrane domain. This function of the spacer domain is to determine the impact based on its length (15). For larger tumour sizes, the binding of epitopes with a spacer domain of a specific length becomes necessary. However, off-target binding can compromise the safety and effectiveness of a therapy (21,22). For example, the interaction of FcRs with the IgG1 Fc spacer domain on rodent macrophages can lead to CAR-induced cell death. To address this issue, Hudecek et al (22) proposed the deletion of the Fc spacer CH2 domain, a critical component of chimeric Fc-FcR interactions. Based on the results of clinical studies, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved certain non-IgG-based spacer domains, such as CD8 and CD28, which are widely used in therapy. Spacers also play a role in quantifying and purifying CAR-positive subsets after engineering.

Transmembrane domain

The transmembrane domain serves as a linker, acting as a pivot point for transmitting ligands and recognition signals to the signalling domain. The TCR-CD3 complex's domains play a crucial part in organising the assembly. Cysteine residues in the transmembrane domain of CD3 are made possible by the dimerization of CD3ζ in the first generation of chimeric antigen T-lymphocytes. This domain is exposed to hydrophobic conditions containing non-polar amino acids as it is an integral part of the basic structure of the genetically modified T-lymphocyte receptor. In the current context, designs of this domain are borrowed from CD4 and CD28, which are relatively independent of the TCR complex and ensure the binding of the independent TCR to the target. According to a review study by Cheng Zhang et al (23) and Sterner et al (24), the most widely accepted and used transmembrane domain is CD28 or CD8α, which is chosen to optimise receptor expression and stability.

Signalling domain

The CAR T-cell therapy can only be partially explained without discussing the signalling domain. The signalling or co-stimulatory domains were engineered in the 1990s and include a CD3ζ domain and a tyrosine-based immunoreceptor (ITAM). ITAMs are present on the TCR-CD3 complex and serve as crucial phosphorylation sites to recruit ZAP70, which plays a critical role in signalling cascades (17). The importance of signalling domains has been discussed in the previous section, with CD28 and 4-1BB as recognised co-stimulatory domains for various B-cell malignancies in the second generation of CARs; this is further elaborated elsewhere (24).

4. Generations of CARs

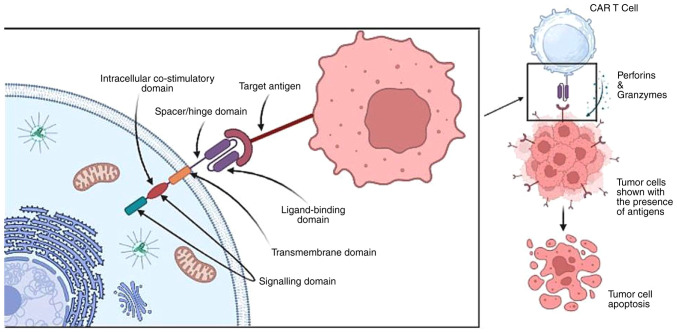

First generation

The CD3ζ chain serves as the primary stimulatory domain in the initial CAR T-cell therapy paradigm from the 1990s. These engineered receptors were widely accepted due to the presence of CD3ζ and ITAMs (Fig. 2) (25,26). Specific drugs for this generation entered clinical trials for the management of leukaemia, ovarian cancer, and neuroblastoma (NB) following successful preclinical results. B-cell lymphoma (BCL) patients received infusions of CD20-CD3ζ CAR T-cells, and several neuroblastoma patients received treatment with ScFv-CD3ζ CAR T-cells. The genetically altered signalling receptors, now known as CARs, were initially referred to as the 'T body approach' model (27,28).

Figure 2.

There are five generations of CAR T-cells. CAR T-cell products made by Kymriah® and Yescarta®, which were approved by the FDA in 2017 are the most prevalent examples of CAR T-based therapies. (A) An intracellular CD3 ITAM, a transmembrane domain, and ScFv are all present in first-generation CARs. (B) Second-generation CARs include auxiliary coordinating domains such as CD28, CD137, and 4-1BB. (C) Third-generation CARs incorporate the addition of two coordinating domains, such as CD3ζ-CD28-OX40 and CD3ζ-CD28-4-1BB, resulting in an increased cytotoxic effect on carcinogenic cells. (D) In fourth-generation CARs, TRUCKs are inserted as the co-stimulatory domain to enhance IL12 production. (E) In fifth-generation CARs, within CD28 and ITAMs, the IL2Rβ-derived JAK-STAT activation domain is present. ITAM, immunoreceptor tyrosine-based activation motif; ScFv, single-chain variable fragment; CAR, chimeric antigen receptor; TRUCK, T-cells redirected for universal cytokine killing; FDA, Federal Drug Administration.

Second generation

The success of the first generation of studies paved the way for a second-generation therapy. The two co-stimulatory domains that have received FDA approval are CD28 and 4-1BB, showing substantial therapeutic benefits in several cancers including chronic lymphoblastic leukaemia (CLL), B-ALL, and multiple myeloma (Fig. 2) (29). Furthermore, a phosphoproteomic mass spectroscopy study demonstrated that CARs with CD28 domains phosphorylate more rapidly and intensely than those with 4-1BB domains. In summary, CD28-based chimeric receptors enhance effector T-cell proliferation responses, whereas 4-1BB-based CARs promote T-cell accumulation (28,29).

Third generation

Enhanced anti-carcinogenic efficacy is achieved by incorporating two signalling domains. Third-generation therapies, such as CD3-CD28-OX40 and CD3-CD28-4-1BB, boost cytokine production and activation signals to promote prolonged proliferation (Fig. 2) (30). Preclinical results for anti-PSMA and anti-mesothelin CD28-4-1BB-CD3ζ CARs have shown increased tumour eradication and persistence abilities compared with the second-generation therapies. These two motifs have been evaluated against several targets including CD19, PSMA, GD2, and mesothelin (31-34).

The superiority of third-generation therapies over second-generation therapies remain a subject of debate. For example, CD28-4-1BB-based CARs demonstrate better preclinical results in mouse xenografts of pancreatic cancer in the third generation. However, second-generation therapies have still outperformed the subsequent generations in terms of their anti-carcinogenic potency. Third-generation therapies exhibit improved in vitro secretion of cytokines such as IL2 and TNFα with anti-GD2 CARs consisting of the CD28-OX40-CD3ζ domain. This domain also shows enhanced proliferation and expansion compared with the second- and first-generation therapies (35,36).

Fourth generation

All previous generations of CAR T-cell therapies exhibit a lack of anti-carcinogenic activity against solid tumours due to the inhospitable microenvironment of solid tumours resulting in heterogeneity and deterioration. The fourth-generation CAR T-cell therapy is also known as T-cells redirected for universal cytokine killing (TRUCK) or 'armoured CARs' (37,38). These armoured chimeric receptors can express cytokines and chemokine receptors such as IL12 to enhance T-cell penetration and protect T-lymphocytes from the oxidative stress microenvironment to enhance infiltration (Fig. 2) (39). An illustrative example involves using antigen-negative cancer cell regulators as a target for antagonistic antibodies such as CTLA-4 and PD-1 demonstrating that blocking PD-1 improves the regulation of HER-2 redirected CAR T-cells leading to an enhanced immune response in HER-2 competent transgenic mice (40).

Fifth generation

Recently, membrane-based receptors have been developed, incorporating an IL2Rβ domain inserted between the co-stimulatory domains CD247 and CD28 to trigger cytokine signalling (Fig. 2). The presence of the YXXQ STAT3 binding motif in the IL2Rβ domain facilitates the induction of CAR T-cells and may activate the JAK-STAT pathway to promote cell proliferation. This generation of CART-cells has shown better persistence in leukaemia (41,42).

5. Mechanism of lysing the tumour cells

CARs serve as a membrane bridge with their receptors spanning both the cell's intracellular and extracellular matrix. The portion protruding from the cell surface typically consists of synthetic antibodies acting as the basic antigen recognition motif. The choice of domains used determines the receptor's ability to detect or bind to tumour cell antigens. Each CAR's internal region, which includes the T-lymphocyte trigger unit and 'co-stimulatory' domains, plays a crucial signalling role. These domains are responsible for transmitting signals within the cell following the interaction between the receptor and antigens. The specific domains used can impact the overall function of the cells. Unlike endogenous TCRs, CARs can recognise unprocessed antigens, regardless of how major histocompatibility antigens are presented. CARs can bind to various targets, including protein-protein peptides, sugars, highly glycosylated proteins, and gangliosides, thus broadening the range of potential targets. While ScFv derived from antibodies are commonly used in the interaction between a CAR and its target, Fab fragments (Fab) acquired from libraries and natural ligands (also known as first-generation CARs) have also been used (43,44).

Leukapheresis, a procedure used to isolate T-cells from leukocytes, is the first step in the mechanism of action. In leukapheresis, leukocytes, T-cells, and other components are separated, following which, in vitro cloning is performed using viruses to develop a modified gene capable of encoding the chimeric receptors (44). The designed CARs recognise and bind to specific antigens or proteins found on the surface of malignant cells (45). The in vitro-engineered T-cells are then expanded to produce tens of thousands of copies. This process may take several weeks and involves the use of cytokines and other growth factors to stimulate T-cell proliferation. Following this, the engineered receptors are introduced into the patient's bloodstream.

Once in the circulatory and lymphatic systems, CAR T-cells come into contact with antigen-presenting cancerous cells. When a CAR encounters the cancer cell expressing the target antigen, it initiates intracellular signalling processes that activate CAR T-cells, leading to an increase in cytokine production. This activation allows CAR T-cells to directly attack the tumour cells through cytotoxicity. CAR T-cells release cytotoxic chemicals, such as perforin and granzymes, which induce apoptosis (programmed cell death) in the cancer cells (Fig. 3) (45). Additionally, CAR T-cells can stimulate other immune cells, such as natural killer (NK) cells and tissue macrophages, which contribute to immune responses aimed at destroying cancer cells or tissues. In certain rare cases, these augmented T-cells can persist in the patient's immune system providing ongoing protection against cancer recurrence (46).

Figure 3.

CAR T-cell mode of action for identifying and binding with tumour antigens and releasing cytokines (perforins and granzymes) resulting in the lysis of carcinogenic cells/tissues.

6. Preclinical experiments on mouse models

Preclinical trials involving xenograft humanised mouse models to investigate tumour progression have enabled researchers to study the tumour microenvironment (TME), which includes components such as blood vessels, lymphocytes, fibroblasts, and the extracellular matrix (ECM). This research has led to the development of humanised patient-derived xenograft (hu-PDX) mouse models designed to preserve genetic profiles and drug responses. The hu-PDX mouse model closely replicates the TME found in humans, with cytokines and chemokines playing a critical role in regulating angiogenesis, metastasis, and immune responses (47,48). Humanised mouse models have been employed in ACT T-lymphocytic therapy to enhance the recognition and elimination of cancer cells. For example, the maturation of transgenic Wilm's tumour (WT-1-specific TCRs in HLA-I transgenic NSG mice transplanted with haematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) enhances cell proliferation capacity and triggers cytokine immune responses, which results in the amplification of anti-carcinogenic effects (49). The success of ACT T-lymphocytic therapies in preclinical and clinical settings paved the way for CAR T-cell therapy in cancer treatment. The necessity to simulate human-originated tumours within an intact immune system has been recognized with the co-evolution of anti-tumour T-cells and the use of CAR T-receptors on humanised (HM) and genetically modified (GEMM) mouse models (50,51). In HM mouse models, experiments involving humanised NRG mice treated with gp350 CAR T-cells showed a reduction in Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) levels. This research has stimulated further investigation into the correlation between the spread of a virus and the incidence of cancer (52). Currently, CAR T-cell therapy has demonstrated significant efficacy in treating various haematological and B-cell malignancies without the restriction of major histocompatibility complex. Chimeric receptors have been engineered to target CD19 in the hu-BLT (bone marrow, liver, and thymus) mouse model, with positive responses observed against primary acute B-ALL (53). As therapies have advanced, the introduction of co-stimulatory motifs such as 4-1BB (CD28 and CD137) has shown promise in enhancing anti-neoplastic responses and cancer cell elimination in hu-SRC (SCID repopulating cell) mice (54). This review emphasises the efficacy of CAR T-cells in BCa treatment and sheds light on various preclinical studies aimed at better understanding their potential. The human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2 also known as ERBB2 belongs to the receptor tyrosine-protein kinase family (55). When triggered, downstream signalling pathways lead to gene overexpression and initiate tumour metastases. In BCa, 20-30% of the patient population exhibit HER2 amplification, highlighting its value as a target in BCa therapy. In preclinical studies, HER2 CAR T-cells resulted in the eradication of tumour cells, even in trastuzumab-resistant JIMT-1 xenografts, leading to improved survival rates in xenograft mice (56). Preclinical studies have targeted various BCa antigens such as FRα, epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR), AXL, MUC1, c-Met, TEM8, and NKG2D, to optimise the efficacy of CAR T-cell therapy in both preclinical and clinical settings. The third generation of CAR T-cell therapy, which includes anti-EGFR antibodies in the ScFv region, has exhibited anti-carcinogenic responses in xenograft mouse models of triple-negative BCa (TNBC) cell lines (57). TNBC offers several potential cell targets, including MUC1, c-Met, AXL, NKG2D, integrin αvβ3, and ROR1, all of which have shown promising preclinical results in various in vitro and in vivo models of engineered CAR T cell therapy (58). For example, CAR T-cells based on the receptor tyrosine kinase AXL have demonstrated significant efficacy in regulating in vitro cytotoxicity in MDA-MB-231 xenograft mice for TNBC (59). Another surface receptor, integrin αvβ3, which plays a role in cell adhesion between epithelial cells and their microenvironment has been targeted using a second generation of chimeric T-lymphocytes in preclinical stages, leading to the release of cytokines such as IL2 and IFNγ (60). The tyrosine kinase receptor c-Met is also being targeted with engineered CAR T-receptors to induce cytolysis in TNBC cells and reduce tumour progression in TNBC xenografts with intact immune metabolism (61). NKG2D-CAR T-cell therapy has been used to target xenograft mouse models by inducing pro-inflammatory responses. In second-generation therapies, these engineered receptors, incorporating co-stimulatory motifs such as 4-1BB, have been shown to regulate anti-carcinogenic activity in vivo (62). Transmembrane proteins such as MUC1 are often overexpressed in TNBC cells in glycosylated form. Therefore, tMUC1-CAR T-cell receptors have been engineered to stimulate cytokines and chemokines to act on mutant alleles in xenograft mice in vitro (63). Aberrations in breast tissues contributing to TNBC can potentially be treated with tyrosine kinase-like orphan receptor 1 (ROR1)-CAR T-cells, which stimulate anti-carcinogenic responses in different in vitro models (64). Numerous other potential cellular targets for TNBC have been explored in preclinical studies, as demonstrated below (Table I).

Table I.

T-lymphocytic CAR targets for TNBC.

| CAR T-lymphocytic target | Pre-clinical outcomes in TNBC | (Refs.) |

|---|---|---|

| AXL | Reduces tumour progression in MDA-MB-231 xenograft mice, Showed in vitro cytotoxicity. The intrinsic regulation of IL7 cytokine enhances the anti-carcinogenic activities in vitro. | (59,65) |

| CD32A | Combination with cetuximab or panitumumab leads to the lysis of EGFR+ve MDA-MB-468 TNBC cells and the release of cytokines like IFNγ and TNFα. | (66) |

| EGFR | EGFR-derived receptors are responsible for the lysis of TNBC tissues in both in vitro and in vivo models. | (57) |

| FRα | In vitro lysis of TNBC cells and regression in an MDA-MB-231 xenograft model. Used as a potential biomarker for effective clinical efficacy. | (67) |

| GD2 | Induces cytotoxicity in TNBC tissues of in vivo models. | (68) |

| ICAM-1 | Acts as a mediator in in vivo TNBC tissues such as an MDA-MB-231 mouse model. | (69) |

| Integrin αvβ3 | Overexpression of integrins in the pre-clinical stages helps target TNBC tissues with second generation-engineered receptors, which results in the release of cytokines such as IL2 and IFNγ. | (60) |

| Mesothelin | Acts as an effector in the PD-1 knockout mouse model of TNBC. | (70) |

| c-Met | Triggers cytolysis of triple negative carcinogenic breast tissues to reduce tumour progression in xenograft models with intact immune metabolism. | (61) |

| MUC1 | Upregulated in TNBC cells in the glycosylated form regulates mutant alleles of xenograft mouse models in vitro. | (63) |

| NKG2D | In a xenograft mouse model, it induced proinflammatory responses to second generation therapies using co-stimulatory motifs 4-1BB to regulate the anti-carcinogenic activities in vivo. | (62) |

| ROR1 | Induces anti-carcinogenic responses in different in vitro 3D culture models. | (64) |

| TEM8 | Anti-carcinogenic responses in TNBC xenograft mouse models. Causes off-target toxicity in in vivo models. | (71,72) |

| TROP2 | Upregulated in TNBC carcinogens. Associated with a poor prognosis due to its promoting effect on pro-carcinogenic signalling pathways. Targeting this results in the elimination of epithelial malignancies in in vitro models. | (73) |

AXL, tyrosine kinase receptor; CAR, chimeric antigen receptor; EGFR, epidermal growth factor receptor; FRα, folate receptor α; GD2, disialoganglioside GD2; ICAM-1, intracellular adhesion molecule-1; c-MET, mesenchymal-epithelial transition factor; MUC1, mucin 1 glycoprotein; NKG2D, natural killer group 2-member D; ROR1, receptor tyrosine kinase-like orphan receptor 1; TEM8, tumour endothelial marker 8; TROP2, trophoblast cell surface antigen 2.

7. Malignancy-specific CAR T-cell clinical trials and BC CAR T-cell clinical studies

Numerous clinical trials are currently underway to develop and advance CAR T-cell immunotherapy (Table II) to assess the effectiveness of this treatment approach for various malignancies. These trials primarily involve patients with B-NHL, B-ALL, CLL, and glioblastoma, as well as other solid tumours and relapsed/refractory malignancies. It would be a remarkable achievement if some of these trials meet the regulatory standards set by the US FDA.

Table II.

Malignancy-specific CAR T-cell clinical trials.

| NCT number | Malignancy | Phase | Target antigen | (Refs.) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NCT02208362 | Glioblastoma | Phase 1 | IL13Ra2 | (74) |

| NCT03726515 | Glioblastoma | Phase 1-completed | EGFRvIII | (75) |

| NCT03198546 | LUSC | Phase 1 | GPC3 | (76) |

| NCT00902044 | OS | Phase 1 | HER-2 | (77) |

| NCT01373047 | LIHC | Phase 1-completed | CEA | (78) |

| NCT01897415 | PAAD | Phase 1-completed | Mesothelin | (79) |

| NCT03323944 | PAAD | Phase 1 | Mesothelin | (80) |

| NCT03159819 | STAD & PAAD | N/A | Claudin 18.2 | (81) |

| NCT03393936 | RCC | Phase 1/2 | AXL | (82) |

| NCT03873805 | CRPC | Phase 1 | PSCA | (83) |

| NCT03089203 | CRPC | Phase 1 | PSMA | (84) |

| NCT04020575 | BRCA | Phase 1 | MUC1 | (85) |

| NCT03585764 | PCC | Phase 1 | Folate receptor-α | (86) |

| NCT02498912 | PCC | Phase 1 | MUC16 | (87) |

| NCT02792114 | BRCA | Phase 1 | Mesothelin | (88) |

| NCT02442297 | CNS Tumour | Phase 1 | HER2 | (89) |

| NCT03696030 | LM, BRCA, HER2+ve BRCA | Phase 1 | HER2 | (90) |

| NCT02414269 | MPE, BRCA | Phase 1/2 | Mesothelin | (91) |

| NCT01044069 | B-ALL | Phase 1 | CD19 | (92) |

| NCT00466531 | B-CLL | Phase 1/2 | CD19 | (93) |

| NCT00586391 | BCL/CLL/ALL | Phase 1 | CD19 | (94) |

| NCT00608270 | B-NHL | Phase 1 | CD19 | (95) |

| NCT02315612 | B-NHL | Phase 1 | CD22 | (96) |

| NCT01722149 | MPM | Phase 1-completed | FAP | (97) |

| NCT02311621 | NB | Phase 1 | CD171 | (98) |

| NCT03274219 | MM | Phase 1 | BCMA | (99) |

| NCT00881920 | CLL, BCL, MM | Phase 1 | CD28 | (100) |

| NCT03939026 | r/r BCL, r/r FL | Phase 1 | CD19 | (101) |

| NCT03666000 | r/r ALL, r/r NHL | Phase 1/2 | CD19 | (102) |

| NCT04035434 | r/r NHL, r/r BCL | Phase 1 | CD19 | (103) |

| NCT03190278 | r/r-AML | Phase 1 | CD123 | (104) |

| NCT04093596 | r/r-MM | Phase 1 | BCMA | (105) |

| NCT03692429 | MCRC | Phase 1 | NKG2D | (106) |

| NCT01044069 | B-ALL | Phase 1 | CD19 | (92) |

| NCT01140373 | CMPC | Phase 1 | PSMA | (107) |

| NCT01822652 | NB | Phase 1 | GD2 | (108) |

| NCT01953900 | NB, OS | Phase 1 | GD2 | (109) |

| NCT02208362 | r-Glioblastoma | Phase 1 | CD19 | (74) |

N/A, not applicable; LUSC, lung squamous cell carcinoma; OS, osteosarcoma; LIHC, liver hepatocellular carcinoma; PAAD, pancreatic adenocarcinoma; STAD, stomach adenocarcinoma; RCC, renal cell carcinoma; CRPC, castrate-resistant prostate cancer; PCC, peritoneal cell carcinoma; BRCA, breast cancer; LM, leptomeningeal metastases; MPE, malignant pleural effusion; B-ALL, B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukaemia; B-CLL, B-cell chronic lymphoblastic leukaemia; BCL, B-cell lymphoma; B-NHL, B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma; MPM, malignant pleural mesothelioma; NB, neuroblastoma; MM, multiple myeloma; FL, follicular lymphoma; r/r-, relapsed and refractory; AML, acute myeloid lymphoma; MCRC, metastatic colorectal cancer; CMPC, castrate metastatic prostate cancer; CNS, central nervous system.

Several clinical studies for administering chimeric antigen immunotherapy in BCa patients are presented in Table III.

Table III.

Breast carcinoma CAR T-cell clinical studies.

| NCT number | Phase | Target antigen | (Refs.) |

|---|---|---|---|

| NCT04329065 | Phase 2 | HER2 | (136) |

| NCT00095706 | Phase 1/2-completed | HER2 +ve | (137) |

| NCT04276493 | Phase 1/2 | HER2 +ve | (138) |

| NCT04170595 | Phase 1/2 | HER2 +ve | (139) |

| NCT03500380 | Phase 2/3 | HER2 +ve | (140) |

| NCT00019812 | Phase 2-completed | HER2 | (141) |

| NCT00003539 | Phase 2-completed | HER2 | (142) |

| NCT00006228 | Phase 2-completed | HER2 +ve | (143) |

| NCT00003992 | Phase 2-completed | HER2 | (144) |

| NCT03571633 | Phase 2 | HER2 +ve | (145) |

| NCT02491892 | Phase 2-completed | HER2 | (146) |

| NCT00301899 | Phase 2-completed | HER2/neu | (147) |

| NCT04924699 | Phase 2/3 | HER2 +ve | (148) |

| NCT04829604 | Phase 2 | HER2 +ve | (149) |

| NCT04107142 | Phase 1 | NKG2DL | (150) |

| NCT05274451 | Phase 1 | ROR1+ | (151) |

| NCT05891197 | Early phase 1 (ongoing) | ROR1 | (152) |

| NCT01837602 | Phase 1-completed | c-MET | (153) |

| NCT02580747 | Phase 1 | Mesothelin | (154) |

| NCT02587689 | Phase 1/2 | MUC1 | (155) |

| NCT04430595 | Phase 1/2 | HER2, GD2 and CD44v6 | (156) |

| NCT02915445 | Phase 1 | EpCAM | (157) |

| NCT03635632 | Phase 1 | GD2 | (158) |

CAR, chimeric antigen receptor.

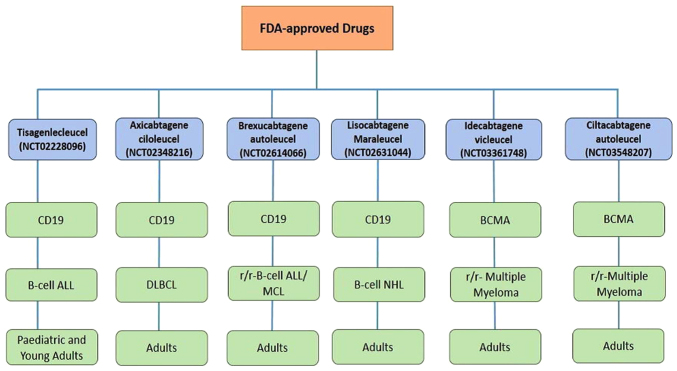

8. FDA-approved therapies

Drugs for treating several refractory/relapsed B-lymphocyte malignancies, including diffuse large cell BCL (DLBCL), have been approved by the FDA in the United States. These approvals stem from promising preclinical studies on mouse models and impressive results from clinical trials. In 2018 FDA granted approval to CTL019 (tisagenlecleucel; NCT02228096; Fig. 4) for use in paediatric B-ALL patients who had relapsed or failed previous treatments. A single-arm, open-label, multi-central phase II research study is currently ongoing to evaluate CTL019's safety and efficacy in patients with r/r-B-ALL. This treatment has shown a high success rate, with CTL019 achieving a 3-month full remission rate of 83% and a 6-month survival rate of 89%. Additionally, the ZUMA-1 trial reported a total remission rate of 59% and an overall response rate of 82% (110,111). In 2019, following the completion of a phase II clinical study, KTE-C19 (NCT02348216; axicabtagene ciloleucel) received FDA authorisation as an orphan medication for the treatment of adults with r/r-DLBCL. After undergoing Yescarta therapy, the complete remission rate was 51% (112). In 2020, brexucabtagene autoleucel was approved for the treatment of certain patients with Mantle cell lymphoma (MCL) (NCT02601313). Furthermore, in October 2021, brexucabtagene autoleucel (Tecartus) received approval for the treatment of adult patients with r/r-B-cell precursor ALL. These trials were conducted under ZUMA-3 phase I/II (NCT02614066), evaluating CD19-targeted CAR T-cell therapy for adult r/r-B-ALL A phase I trial infused lisocabtagene maraleucel (NCT02631044) to assess the drug's safety and efficacy levels for patients with r/r-B-cell NHL. According to a 23-month trial, lisocabtagene maraleucel achieved an overall response rate (ORR) of 73% (113). In 2021, idecabtagene vicleucel was authorised by the US FDA for use in treating adult patients with r/r-multiple myeloma. An ongoing phase II trial [NCT03361748] for this drug showed ORR and CR rates of 72 and 28%, respectively with ~65% of patients remaining in CR for a full year. Finally, ciltacabtagene autoleucel was licensed for adult patients with r/r-multiple myeloma in February 2022 based on the findings of the phase II clinical study [NCT03548207]. The clinical study reported an ORR of 97.9%, a response time of 21.8 months, and a follow-up time of ~18 months. To identify the most precise medications for specific types of malignancies and further enhance treatment efficacy several clinical trials are currently underway, with the potential for future FDA approvals (Table II).

Figure 4.

FDA-approved drugs for the CAR-T-cell therapy of different malignancies such as B-ALL, DLBCL, r/r-B-ALL, B-cell NHL, and r/r-MM in paediatric and adult patients. FDA, Federal Drug Administration; B-ALL, B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukaemia; DLBCL, diffuse large cell B-cell lymphoma, r/r-, relapsed/refractory; B-cell NHL, B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma; MM, multiple myeloma.

9. Contemporary advances in breast carcinoma CAR T cell therapy

In accordance with the intensity of their expression, tumour antigens are categorised into three groups: Cancer germline antigens, tumour-specific antigens (TSAs), and tumour-associated antigens (TAAs) (114). Cancer cells display TSAs on their surface with malignant cells being rich in TAAs such as HER2 and CD19 (115,116). Targeting TSAs can lead to side effects such as on-target/off-target toxicity as chimeric T-cells attack them (117). Inhibitors such as PARP, CDK4/6, AKT, and HER2, that affect various carcinogenesis pathways, including the cell cycle, metastasis, and angiogenesis, have been investigated as potential therapeutic targets for impeding BCa proliferation. To date, four PARP antagonists (olaparib, talazoparib, rucaparib, and niraparib) have undergone extensive clinical research. Olaparib, the first FDA-approved PARP inhibitor, targets the genetic activity of the TOPBP1 and WEE1 genes. Olaparib is administered both as combination therapy (alongside chemotherapy) and as a monotherapy, with common side effects including anaemia and neutropenia (NCT02000622, NCT01445418, NCT02734004, NCT02032823, and NCT02789332) (118,119). CDK4/6 plays a crucial role in facilitating tumour cell progression. FDA-approved CDK4/6 antagonists include palbociclib, abemaciclib, and ribociclib, primarily targeting the FOXM1 gene. Palbociclib, the first effective CDK4/6 inhibitor, benefits both post- and pre-menopausal women with HER2-negative and HR-positive BCa, with neutropenia being a common side effect. In certain combination therapies, pulmonary embolism, back pain, and diarrhoea were also observed (NCT02513394, NCT00141297, NCT01037790, NCT00721409, and NCT01942135) (119,120). In the AKT/PI3K/mTOR signalling pathway, AKT is a vital transducer affecting genes such as PI3K, FOXO1, PIP2, PDK1, TSC1/2, and mTOR. Activated AKT suppresses apoptotic pathways (Bcl-2-associated death promoter) while stimulating cell proliferation pathways. Both allosteric and ATP-competitive inhibitors have been designed, with ATP-competitive AKT inhibitors proving superior. MK-2206, an allosteric inhibitor, used in combination therapy with trastuzumab, anthracycline, and neoadjuvant chemotherapy, was particularly effective for HER2-positive BCa. Capivasertib and ipatasertib have demonstrated better efficacy than other ATP-competitive inhibitors (121). Advances in HER2-targeted malignancy treatments have led to increased survival rates for HER2-positive BCa patients (122). CAR T-cell immunotherapy plays a crucial role in addressing the clinical challenge of BCa metastasis. HER2-redirected chimeric T-cell receptor immunotherapy can trigger a remarkable immunological response in xenograft models (123). This third-generation CAR T-cell therapy, featuring the CD28 or 4-1BB co-stimulatory domain, enhances survival, proliferation, and cancer cell control by CAR T-cells (124). Approximately 20-30% of patients with HER2 amplification with adverse prognostic outcomes have been administered HER2/ERBB2 targeting the tyrosine kinase receptors that are responsible for activating the downstream signalling pathways such as P13K, MEK, PKC, and JAK/STAT once triggered, leading to tumour progression (125). The FDA-approved mAB trastuzumab targets HER2 receptors and has resulted in clinical improvements for BCa patients (126). The clinical trial [NCT02792114] identified MSLN as a prospective therapeutic target for MSLN-specific metastatic BCa. To optimize tumour specificity, the in vitro CAR T-cell therapy has been developed for targeting MUC1 and ERBB2 for BCa patients, resulting in T-cell survival within malignant tumour cells (127). Targeting the env gene of human endogenous retroviruses (HERV)-K with HERV-K-targeted CAR T-cell therapy has demonstrated anti-malignant effects, as the env protein is involved in tumour progression and is expressed in ~70% of BCa cases (128,129). Approximately 15-30% of BCa patients have HER1 gene amplification; primarily in cases of TNBC (130). TNBC is resistant to conventional (anti-HER2 and endocrine) treatments due to the absence of EGFR, oestrogen receptors (ERs), and progesterone receptors (PRs) (131). TNBC occurs in 45-70% of patients (132). Several target antigens for TNBC, such as chondroitin sulphate proteoglycan 4 (CSPG4), intracellular adhesion molecule-1 (ICAM-1), natural killer group 2 member D ligand (NKG2DL), AXL, tumour endothelial marker 8 (TEM8), integrin αVβ3, orphan receptor 1 (ROR1), c-MET, folate receptor α (FRα), EGFR, mesothelin, disialoganglioside (GD2), mucin 1 (MUC1), and trophoblast cell-surface antigen 2 (TROP2), have been identified (133) Atezolizumab, an anti-PD L1-based immunotherapy, in combination with the chemotherapeutic drug nab-paclitaxel, is used for TNBC treatment (134). Other promising target antigens are currently in the preclinical stage. Based on the results of nano-ultra performance liquid chromatography, five antigens have been identified, namely, IL-32, syntenin-1, ribophorin-2, proliferating cell nuclear antigen, and cofilin-1 (135). Targeting these tumour antigens may replace chemotherapy treatments and serve as a future approach for reprogramming CAR T-cells for TNBC treatment.

10. Limitations

The remarkable success of these engineered chimeric receptors in treating B-cell and haematological malignancies has made them a considerable and promising therapeutic option for B-cell tumours and haematological cancers. Despite being one of the most advanced therapies against malignancies, CAR T-cell therapy has several potential toxicities, including CRS, NT, on/off-target tumour detection, and induction of anaphylaxis (159,160). Additionally, there are certain challenges that arise during the treatment of solid tumours such as BCa and TNBC, including antigen escape (161) and an immunosuppressive tumour microenvironment (162).

CRS

CRS is an unfavourable inflammatory response that can occur during CAR T-cell therapy and mAB infusions. CRS is triggered by the activation of NK cells, B-lymphocytes, T-lymphocytes, phagocytic cells, APCs, and certain endothelial tissue matrix cells (163,164). CRS is witnessed following the infusion of mAbs, IL2, and certain bispecific CAR T-cell domains such as CD19-CD3 antibodies. The severity of CRS depends on the tumour burden in the patient. For instance, a case report by Teachey et al (165) noted that patients with relapsed/refractory B-ALL who received CD19-specific CAR T-cell immunotherapy experienced complications, including high levels of CRS (19-43%).

Corticosteroids play a significant role in reversing CRS symptoms without affecting the drug's anti-malignant effect. However, it is worth noting that prolonged systemic corticosteroid use for >14 days can have adverse effects on the drug's anti-carcinogenic effects. To address this concern, the FDA approved tocilizumab as a rapid reversal drug for CRS (166-169).

On/off-target carcinogen recognition

On/Off-target toxicity occurs when the intended target carcinogen is primarily present in cancerous cells but also binds to CAR T-cell target antigens in non-malignant tissues. This toxicity has been observed in gastrointestinal and haematologic organ systems (170). The first instance of on/off-target toxicity was observed in renal cell carcinoma patients who were treated with chimeric antigen-recognising carbonic anhydrase IX (CAIX) (171).

A study conducted by Morgan et al (172) observed toxicity in colorectal cancer patients who received third-generation CAR T-cell therapy targeting CRBB2/HER2. To mitigate the extent of long-term toxicities such as those mentioned above, suicidal genes can be introduced into the vector (172,173).

Patients receiving CAR T-cell therapy for CD19-specific neoplasms may experience focal neurological symptoms, including aphasia, seizures, allodynia, and apraxia (174). Importantly, the severity of neurological sequelae can be partially influenced by the cytokine levels of the patient. For example, 78% of B-cell NHL patients who received axicabtagene ciloleucel experienced NT, and 87% of B-ALL patients treated with brexucabtagene autoleucel suffered from neurologic toxicities. Studies have shown no clear correlation between the proportion of modified and naturally occurring T-cells and the presence of EEG abnormalities. It remains unclear whether NT is specific to CD19-specific malignancies or can occur with other antigens (175).

Anaphylaxis

Anaphylaxis occurs when the body's natural defence system overreacts and triggers an excessive inflammatory response. The primary reason for anaphylaxis in CAR T-cell therapy is the use of chimeric T-lymphocytic receptors derived from murine mAbs (175,176). Mesothelin, a tumour-associated antigen, is often overexpressed in malignancies such as malignant pleural mesothelioma (MPM), pancreatic cancer, and ovarian cancer. Preclinical models showed that multiple infusions of anti-mesothelin and anti-CD19 RNA CAR T-cells had anti-tumour effects. Based on this, human clinical trials were conducted (NCT01355965) involving meso-RNA-CAR T therapy. However, multiple meso-mRNA CAR T-cell infusions in a limited time frame resulted in a patient experiencing an anaphylactic shock. To mitigate this toxicity, T-cell infusion was terminated (177-179). The transfer of genetically engineered T-cells requires careful monitoring, prompt recognition, and immediate management of these side effects to reduce any potential negative outcomes.

Toxicities in BCa and TNBC

One major limitation when targeting BCa antigens is the proper identification of the target antigen due to its low expression levels in vital organs, which could lead to off-target toxic effects (114). Another toxic outcome when targeting these receptors on proliferating cells in breast tissues is intratumor heterogeneity, which causes resistance of tumour antigens to single target engineered receptors, a phenomenon known as antigen escape. In antigen escape, engineered CAR T-cells lose their efficacy against carcinogens. To counteract this toxicity, several preclinical experiments have combined dual antigens to target solid tumours, which eventually improves treatment efficacy. For example, several tandem chimeric receptors, including HER2 and MUC1 in BCa, have shown enhanced anti-carcinogenic effects in preclinical models. Another significant challenge of CAR T-cell therapy in solid tumours, particularly in BCa, is associated with an immunosuppressive TME. The TME is comprised of multiple immunosuppressive elements, including carcinogenic cells, regulatory T-lymphocytes (Treg), myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs), cancer-associated fibroblasts, and tumour-associated macrophages (TAMs). Additionally, various cytokines, chemokines, and extracellular matrix components are integral parts of the TME that help in regulating progression, angiogenesis, and metastasis by providing necessary growth regulators, chemokines, interleukins, transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β), indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase (IDO), and vascular endothelial growth factor. PD-1 and CTLA-4 are other immunosuppressive checkpoint blockers that affect chimeric-engineered T-receptors, hindering their anti-carcinogenic reactions against solid tumours such as TNBC (180-183). A strategy to combat the immunosuppressive TME involves engineering armoured CARs that release pro-inflammatory cytokines to favourably reshape anti-carcinogenic responses. Interleukins such as IL-12 and IL-18 are released to enhance anti-carcinogenic reactions by IFNγ and Treg inhibition that triggers M1 macrophages (184,185).

11. Conclusions and future perspectives

A significant barrier leading to on/off-target tumour toxicity in solid tumours associated with TAAs is the challenge of specifically targeting tumour cells. New CAR designs are being developed with improved tumour selectivity and reduced off-target effects. This includes the use of synthetic receptors such as synNotch receptors to enhance the specificity of CAR T-cells. Another hurdle is TME, in which solid tumours release chemotactic cytokines such as CXCL1, CXCL12, and CXCL5, which suppress T-cell activation (186,187). To overcome these challenges, additional proteins such as armoured CAR T-cells are incorporated into engineered receptors to withstand immunosuppressive responses primarily found in TME to improve the eradication of tumours. The incorporation of 'suicide genes' into CARs also provides an opportunity to mitigate toxicity by deactivating the CAR T-cells (188,189). TNBCs, which have historically been challenging to treat and often rely on chemotherapy with low survival rates, are now the focus of several combination therapies in preliminary and interventional trials. Examples include CDK7 with EGFR CAR therapy (190) and anti-PD-L1 with PARP inhibitory therapy (190). Researchers are continually exploring various methods to overcome these obstacles, such as integrating CRISPR/Cas9 systems into CAR immunotherapy for genome editing and the development of universal CAR T-cells (190,191). Advances in multi-omics have improved the ability to identify unique neoantigens resulting from tumour-specific polymorphisms, potentially leading to more targeted therapies with fewer adverse effects (192).

The potential developments in CAR T-cell therapy are promising and marked by significant advancements. As technology progresses, the field may witness increased safety measures, innovative target identification, combination therapies, an increased range of tools, and breakthroughs in manufacturing and delivery. These developments are likely to shape the landscape of precision immunotherapy, highlighting novel avenues for more effective and personalised cancer treatments. The unwavering dedication of researchers, healthcare professionals, and industry stakeholders will pave the way for a future where CAR T-cell immunotherapy proves highly effective in treating sarcomas, ultimately improving patient outcomes (193).

Overall, the potential of CAR T-cells in treating solid tumours, including BCa and TNBC, has yielded promising results in clinical trials. The label of being 'difficult to treat' for TNBCs may soon be erased through the effective outcomes achievable with these engineered receptors.

Acknowledgments

Not applicable.

Funding Statement

This research has been funded by Scientific Research Deanship at University of Ha'il-Saudi Arabia through project number MDR-22 038.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Authors' contributions

MZN, S, wrote the major parts of the manuscript and prepared the figures and tables. CD and SG revised the manuscript. HEME, FHK, AAE and NT performed the bibliographic research and prepared the table and figures. MAK conceptualized the study and oversaw the process. All authors helped to write the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript. Data authentication is not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

- 1.National Cancer Institute What is cancer? 2021. https://www.cancer.gov/about-cancer/understanding/what-is-cancer .

- 2.Blackadar CB. Historical review of the causes of cancer. World J Clin Oncol. 2016;7:54–86. doi: 10.5306/wjco.v7.i1.54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Debela DT, Muzazu SG, Heraro KD, Ndalama MT, Mesele BW, Haile DC, Kitui SK, Manyazewal T. New approaches and procedures for cancer treatment: Current perspectives. SAGE Open Med. 2021;9:20503121211034366. doi: 10.1177/20503121211034366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Decker WK, Safdar A. Bioimmunoadjuvants for the treatment of neoplastic and infectious disease: Coley's legacy revisited. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2009;20:271–281. doi: 10.1016/j.cytogfr.2009.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Valent P, Groner B, Schumacher U, Superti-Furga G, Busslinger M, Kralovics R, Zielinski C, Penninger JM, Kerjaschki D, Stingl G, et al. Paul Ehrlich (1854-1915) and his contributions to the foundation and birth of translational medicine. J Innate Immun. 2016;8:111–120. doi: 10.1159/000443526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rosenberg SA. IL-2: The first effective immunotherapy for human cancer. J Immunol. 2014;192:5451–5458. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1490019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pierpont TM, Limper CB, Richards KL. Past, present, and future of rituximab-the world's first oncology monoclonal antibody therapy. Front Oncol. 2018;8:163–163. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2018.00163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.June CH, O'Connor RS, Kawalekar OU, Ghassemi S, Milone MC. CAR T cell immunotherapy for human cancer. Science. 2018;359:1361–1365. doi: 10.1126/science.aar6711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rosenberg SA, Restifo NP, Yang JC, Morgan RA, Dudley ME. Adoptive cell transfer: A clinical path to effective cancer immunotherapy. Nat Rev Cancer. 2008;8:299–308. doi: 10.1038/nrc2355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gross G, Waks T, Eshhar Z. Expression of immunoglobulin-T-cell receptor chimeric molecules as functional receptors with antibody-type specificity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1989;86:10024–10028. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.24.10024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Graham C, Hewitson R, Pagliuca A, Benjamin R. Cancer immunotherapy with CAR-T cells-behold the future. Clin Med (Lond) 2018;18:324–328. doi: 10.7861/clinmedicine.18-4-324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Maus MV. A decade of CAR T cell evolution. Nat Cancer. 2022;3:270–271. doi: 10.1038/s43018-022-00347-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cameron BJ, Gerry AB, Dukes J, Harper JV, Kannan V, Bianchi FC, Grand F, Brewer JE, Gupta M, Plesa G, et al. Identification of a Titin-derived HLA-A1-presented peptide as a cross-reactive target for engineered MAGE A3-directed T cells. Sci Transl Med. 2013;5:197ra103. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3006034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.June CH, Riddell SR, Schumacher TN. Adoptive cellular therapy: A race to the finish line. Sci Transl Med. 2015;7:280ps7. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aaa3643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lee YH, Kim CH. Evolution of chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T cell therapy: current status and future perspectives. Arch Pharm Res. 2019;42:607–616. doi: 10.1007/s12272-019-01136-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Titov A, Valiullina A, Zmievskaya E, Zaikova E, Petukhov A, Miftakhova R, Bulatov E, Rizvanov A. Advancing CAR T-cell therapy for solid tumors: Lessons learned from lymphoma treatment. Cancers (Basel) 2020;12:125. doi: 10.3390/cancers12010125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jayaraman J, Mellody MP, Hou AJ, Desai RP, Fung AW, Pham AHT, Chen YY, Zhao W. CAR-T design: Elements and their synergistic function. EBioMedicine. 2020;58:102931. doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2020.102931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Xie YJ, Dougan M, Jailkhani N, Ingram J, Fang T, Kummer L, Momin N, Pishesha N, Rickelt S, Hynes RO, Ploegh H. Nanobody-based CAR T cells that target the tumor microenvironment inhibit the growth of solid tumors in immunocompetent mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2019;116:7624–7631. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1817147116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Barber A, Rynda A, Sentman CL. Chimeric NKG2D expressing T cells eliminate immunosuppression and activate immunity within the ovarian tumor microenvironment. J Immunol. 2009;183:6939–6947. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0902000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lynn RC, Feng Y, Schutsky K, Poussin M, Kalota A, Dimitrov DS, Powell DJ., Jr High-affinity FRβ-specific CAR T cells eradicate AML and normal myeloid lineage without HSC toxicity. Leukemia. 2016;30:1355–1364. doi: 10.1038/leu.2016.35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Guest RD, Hawkins RE, Kirillova N, Cheadle EJ, Arnold J, O'Neill A, Irlam J, Chester KA, Kemshead JT, Shaw DM, et al. The role of extracellular spacer regions in the optimal design of chimeric immune receptors: Evaluation of four different scFvs and antigens. J Immunother. 2005;28:203–211. doi: 10.1097/01.cji.0000161397.96582.59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hudecek M, Sommermeyer D, Kosasih PL, Silva-Benedict A, Liu L, Rader C, Jensen MC, Riddell SR. The nonsignaling extracellular spacer domain of chimeric antigen receptors is decisive for in vivo antitumor activity. Cancer Immunol Res. 2015;3:125–135. doi: 10.1158/2326-6066.CIR-14-0127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhang C, Liu J, Zhong JF, Zhang X. Engineering CAR-T cells. Biomark Res. 2017;5:22. doi: 10.1186/s40364-017-0102-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sterner RC, Sterner RM. CAR-T cell therapy: Current limitations and potential strategies. Blood Cancer J. 2021;11:69. doi: 10.1038/s41408-021-00459-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mohanty R, Chowdhury CR, Arega S, Sen P, Ganguly P, Ganguly N. CAR T cell therapy: A new era for cancer treatment (Review) Oncol Rep. 2019;42:2183–2195. doi: 10.3892/or.2019.7335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhang Q, Ping J, Huang Z, Zhang X, Zhou J, Wang G, Liu S, Ma J. CAR-T cell therapy in cancer: Tribulations and road ahead. J Immunol Res. 2020;2020:1924379. doi: 10.1155/2020/1924379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Louis CU, Savoldo B, Dotti G, Pule M, Yvon E, Myers GD, Rossig C, Russell HV, Diouf O, Liu E, et al. Antitumor activity and long-term fate of chimeric antigen receptor-positive T cells in patients with neuroblastoma. Blood. 2011;118:6050–6056. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-05-354449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Duong CP, Yong CS, Kershaw MH, Slaney CY, Darcy PK. Cancer immunotherapy utilizing gene-modified T cells: From the bench to the clinic. Mol Immunol. 2015;67:46–57. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2014.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Qian L, Li D, Ma L, He T, Qi F, Shen J, Lu XA. The novel anti-CD19 chimeric antigen receptors with humanized scFv (single-chain variable fragment) trigger leukemia cell killing. Cell Immunol. 2016;304:49–54. doi: 10.1016/j.cellimm.2016.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lock D, Mockel-Tenbrinck N, Drechsel K, Barth C, Mauer D, Schaser T, Kolbe C, Al Rawashdeh W, Brauner J, Hardt O, et al. Automated manufacturing of potent CD20-directed chimeric antigen receptor t cells for clinical use. Hum Gene Ther. 2017;28:914–925. doi: 10.1089/hum.2017.111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhao Z, Condomines M, van der Stegen SJC, Perna F, Kloss CC, Gunset G, Plotkin J, Sadelain M. Structural design of engineered costimulation determines tumor rejection kinetics and persistence of CAR T cells. Cancer Cell. 2015;28:415–428. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2015.09.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hombach A, Hombach AA, Abken H. Adoptive immunotherapy with genetically engineered T cells: Modification of the IgG1 Fc 'spacer' domain in the extracellular moiety of chimeric antigen receptors avoids 'off-target'activation and unintended initiation of an innate immune response. Gene Ther. 2010;17:1206–1213. doi: 10.1038/gt.2010.91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhong XS, Matsushita M, Plotkin J, Riviere I, Sadelain M. Chimeric antigen receptors combining 4-1BB and CD28 signaling domains augment PI3kinase/AKT/Bcl-XL activation and CD8+ T cell-mediated tumor eradication. Mol Ther. 2010;18:413–420. doi: 10.1038/mt.2009.210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Quintarelli C, Orlando D, Boffa I, Guercio M, Polito VA, Petretto A, Lavarello C, Sinibaldi M, Weber G, Del Bufalo F, et al. Choice of costimulatory domains and of cytokines determines CAR T-cell activity in neuroblastoma. Oncoimmunology. 2018;7:e1433518. doi: 10.1080/2162402X.2018.1433518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Abate-Daga D, Lagisetty KH, Tran E, Zheng Z, Gattinoni L, Yu Z, Burns WR, Miermont AM, Teper Y, Rudloff U, et al. A novel chimeric antigen receptor against prostate stem cell antigen mediates tumor destruction in a humanized mouse model of pancreatic cancer. Hum Gene Ther. 2014;25:1003–1012. doi: 10.1089/hum.2013.209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pulè MA, Straathof KC, Dotti G, Heslop HE, Rooney CM, Brenner MK. A chimeric T cell antigen receptor that augments cytokine release and supports clonal expansion of primary human T cells. Mol Ther. 2005;12:933–941. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2005.04.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Beatty GL, Moon EK. Chimeric antigen receptor T cells are vulnerable to immunosuppressive mechanisms present within the tumor microenvironment. Oncoimmunology. 2014;3:e970027. doi: 10.4161/21624011.2014.970027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chmielewski M, Abken H. TRUCKs: The fourth generation of CARs. Expert Opin Biol Ther. 2015;15:1145–1154. doi: 10.1517/14712598.2015.1046430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kueberuwa G, Kalaitsidou M, Cheadle E, Hawkins RE, Gilham DE. CD19 CAR T cells expressing IL-12 eradicate lymphoma in fully lymphoreplete mice through induction of host immunity. Mol Ther Oncolytics. 2017;8:41–51. doi: 10.1016/j.omto.2017.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.John LB, Devaud C, Duong CP, Yong CS, Beavis PA, Haynes NM, Chow MT, Smyth MJ, Kershaw MH, Darcy PK. Anti-PD-1 antibody therapy potently enhances the eradication of established tumors by gene-modified T cells. Clin Cancer Res. 2013;19:5636–5646. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-13-0458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kim DW, Cho JY. Recent advances in allogeneic CAR-T cells. Biomolecules. 2020;10:263. doi: 10.3390/biom10020263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kagoya Y, Tanaka S, Guo T, Anczurowski M, Wang CH, Saso K, Butler MO, Minden MD, Hirano N. A novel chimeric antigen receptor containing a JAK-STAT signaling domain mediates superior antitumor effects. Nat Med. 2018;24:352–359. doi: 10.1038/nm.4478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Dai H, Wang Y, Lu X, Han W. Chimeric antigen receptors modified T-cells for cancer therapy. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2016;108:djv439. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djv439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Li D, Li X, Zhou WL, Huang Y, Liang X, Jiang L, Yang X, Sun J, Li Z, Han WD, Wang W. Genetically engineered T cells for cancer immunotherapy. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2019;4:35. doi: 10.1038/s41392-019-0070-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Levine BL, Miskin J, Wonnacott K, Keir C. Global manufacturing of CAR T cell therapy. Mol Ther Methods Clin Dev. 2016;4:92–101. doi: 10.1016/j.omtm.2016.12.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Benmebarek MR, Karches CH, Cadilha BL, Lesch S, Endres S, Kobold S. Killing mechanisms of chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T cells. Int J Mol Sci. 2019;20:1283. doi: 10.3390/ijms20061283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Guo S, Deng CX. Effect of stromal cells in tumor microenvironment on metastasis initiation. Int J Biol Sci. 2018;14:2083–2093. doi: 10.7150/ijbs.25720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Morton JJ, Bird G, Keysar SB, Astling DP, Lyons TR, Anderson RT, Glogowska MJ, Estes P, Eagles JR, Le PN, et al. XactMice: Humanizing mouse bone marrow enables microenvironment reconstitution in a patient-derived xenograft model of head and neck cancer. Oncogene. 2016;35:290–300. doi: 10.1038/onc.2015.94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Najima Y, Tomizawa-Murasawa M, Saito Y, Watanabe T, Ono R, Ochi T, Suzuki N, Fujiwara H, Ohara O, Shultz LD, et al. Induction of WT1-specific human CD8+ T cells from human HSCs in HLA class I Tg NOD/SCID/IL2rgKO mice. Blood. 2016;127:722–734. doi: 10.1182/blood-2014-10-604777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Yin L, Wang XJ, Chen DX, Liu XN, Wang XJ. Humanized mouse model: A review on preclinical applications for cancer immunotherapy. Am J Cancer Res. 2020;10:4568–4584. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zitvogel L, Pitt JM, Daillère R, Smyth MJ, Kroemer G. Mouse models in on immunology. Nat Rev Cancer. 2016;16:759–773. doi: 10.1038/nrc.2016.91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Slabik C, Kalbarczyk M, Danisch S, Zeidler R, Klawonn F, Volk V, Krönke N, Feuerhake F, Ferreira de Figueiredo C, Blasczyk R, et al. CAR-T cells targeting Epstein-Barr virus gp350 validated in a humanized mouse model of EBV infection and lymphoproliferative disease. Mol Ther Oncolytics. 2020;18:504–524. doi: 10.1016/j.omto.2020.08.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Jin CH, Xia J, Rafiq S, Huang X, Hu Z, Zhou X, Brentjens RJ, Yang YG. Modeling anti-CD19 CAR T cell therapy in humanized mice with human immunity and autologous leukemia. EBioMedicine. 2019;39:173–181. doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2018.12.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Gulati P, Rühl J, Kannan A, Pircher M, Schuberth P, Nytko KJ, Pruschy M, Sulser S, Haefner M, Jensen S, et al. Aberrant Lck signal via CD28 costimulation augments antigen-specific functionality and tumor control by redirected T cells with PD-1 blockade in humanized mice. Clin Cancer Res. 2018;24:3981–3993. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-17-1788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Roskoski R., Jr The ErbB/HER family of protein-tyrosine kinases and cancer. Pharmacol Res. 2014;79:34–74. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2013.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Szöőr Á, Tóth G, Zsebik B, Szabó V, Eshhar Z, Abken H, Vereb G. Trastuzumab derived HER2-specific CARs for the treatment of trastuzumab-resistant breast cancer: CAR T cells penetrate and eradicate tumors that are not accessible to antibodies. Cancer Lett. 2020;484:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2020.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Liu Y, Zhou Y, Huang KH, Li Y, Fang X, An L, Wang F, Chen Q, Zhang Y, Shi A, et al. EGFR-specific CAR-T cells trigger cell lysis in EGFR-positive TNBC. Aging (Albany NY) 2019;11:11054–11072. doi: 10.18632/aging.102510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Corti C, Venetis K, Sajjadi E, Zattoni L, Curigliano G, Fusco N. CAR-T cell therapy for triple-negative breast cancer and other solid tumors: Preclinical and clinical progress. Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 2022;31:593–605. doi: 10.1080/13543784.2022.2054326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wei J, Sun H, Zhang A, Wu X, Li Y, Liu J, Duan Y, Xiao F, Wang H, Lv M, et al. A novel AXL chimeric antigen receptor endows T cells with anti-tumor effects against triple negative breast cancers. Cell Immunol. 2018;331:49–58. doi: 10.1016/j.cellimm.2018.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wallstabe L, Mades A, Frenz S, Einsele H, Rader C, Hudecek M. CAR T cells targeting αvβ3 integrin are effective against advanced cancer in preclinical models. Adv Cell Gene Ther. 2018;1:e11. doi: 10.1002/acg2.11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Zhao X, Qu J, Hui Y, Zhang H, Sun Y, Liu X, Zhao X, Zhao Z, Yang Q, Wang F, Zhang S. Clinicopathological and prognostic significance of c-Met overexpression in breast cancer. Oncotarget. 2017;8:56758–56767. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.18142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Han Y, Xie W, Song DG, Powell DJ., Jr Control of triple-negative breast cancer using ex vivo self-enriched, costimulated NKG2D CAR T cells. J Hematol Oncol. 2018;11:92. doi: 10.1186/s13045-018-0635-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Zhou R, Yazdanifar M, Roy LD, Whilding LM, Gavrill A, Maher J, Mukherjee P. CAR T cells targeting the tumor MUC1 glycoprotein reduce triple-negative breast cancer growth. Front Immunol. 2019;10:1149. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2019.01149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Wallstabe L, Göttlich C, Nelke LC, Kühnemundt J, Schwarz T, Nerreter T, Einsele H, Walles H, Dandekar G, Nietzer SL, Hudecek M. ROR1-CAR T cells are effective against lung and breast cancer in advanced microphysiologic 3D tumor models. JCI Insight. 2019;4:e126345. doi: 10.1172/jci.insight.126345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Zhao Z, Li Y, Liu W, Li X. Engineered IL-7 receptor enhances the therapeutic effect of AXL-CAR-T cells on triple-negative breast cancer. Biomed Res Int. 2020;2020:4795171. doi: 10.1155/2020/4795171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Caratelli S, Arriga R, Sconocchia T, Ottaviani A, Lanzilli G, Pastore D, Cenciarelli C, Venditti A, Del Principe MI, Lauro D, et al. In vitro elimination of epidermal growth factor receptor-overexpressing cancer cells by CD32A-chimeric receptor T cells in combination with cetuximab or panitumumab. Int J Cancer. 2020;146:236–247. doi: 10.1002/ijc.32663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Song DG, Ye Q, Poussin M, Chacon JA, Figini M, Powell DJ., Jr Effective adoptive immunotherapy of triple-negative breast cancer by folate receptor-alpha redirected CAR T cells is influenced by surface antigen expression level. J Hematol Oncol. 2016;9:56. doi: 10.1186/s13045-016-0285-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Seitz CM, Schroeder S, Knopf P, Krahl AC, Hau J, Schleicher S, Martella M, Quintanilla-Martinez L, Kneilling M, Pichler B, et al. GD2-targeted chimeric antigen receptor T cells prevent metastasis formation by elimination of breast cancer stem-like cells. Oncoimmunology. 2019;9:1683345. doi: 10.1080/2162402X.2019.1683345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Yang Y, Vedvyas Y, McCloskey JE, Min IM, Jin MM. ICAM-1 targeting CAR T cell therapy for triple negative breast cancer. Cancer Res. 2019;79(13 Suppl):S2322. doi: 10.1158/1538-7445.AM2019-2322. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Hu W, Zi Z, Jin Y, Li G, Shao K, Cai Q, Ma X, Wei F. CRISPR/Cas9-mediated PD-1 disruption enhances human mesothelin-targeted CAR T cell effector functions. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2019;68:365–377. doi: 10.1007/s00262-018-2281-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Petrovic K, Robinson J, Whitworth K, Jinks E, Shaaban A, Lee SP. TEM8/ANTXR1-specific CAR T cells mediate toxicity in vivo. PLoS One. 2019;14:e0224015. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0224015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Byrd TT, Fousek K, Pignata A, Szot C, Samaha H, Seaman S, Dobrolecki L, Salsman VS, Oo HZ, Bielamowicz K, et al. TEM8/ANTXR1-specific CAR T cells as a targeted therapy for triple-negative breast cancer. Cancer Res. 2018;78:489–500. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-16-1911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Bedoya DM, King T, Posey AD. Generation of CART cells targeting oncogenic TROP2 for the elimination of epithelial malignancies. Cytotherapy. 2019;21(Suppl):S11–S12. doi: 10.1016/j.jcyt.2019.03.570. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 74.National Library of Medicine (NLM) ClinicalTrials.gov ID, NCT02208362. NLM; Bethesda, MD: 2015. Genetically Modified T-cells in Treating Patients With Recurrent or Refractory Malignant Glioma. https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT02208362 . [Google Scholar]

- 75.National Library of Medicine (NLM) ClinicalTrials.gov ID, NCT03726515. NLM; Bethesda, MD: 2019. CART-EGFRvIII + Pembrolizumab in GBM. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT03726515 . [Google Scholar]

- 76.National Library of Medicine (NLM) ClinicalTrials.gov ID, NCT03198546. NLM; Bethesda, MD: 2017. GPC3-CAR-T Cells for Immunotherapy of Cancer With GPC3 Expression. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT03198546 . [Google Scholar]

- 77.National Library of Medicine (NLM) ClinicalTrials.gov ID, NCT00902044. NLM; Bethesda, MD: 2010. Her2 Chimeric Antigen Receptor Expressing T Cells in Advanced Sarcoma. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT00902044 . [Google Scholar]

- 78.National Library of Medicine (NLM) ClinicalTrials.gov ID, NCT01373047. NLM; Bethesda, MD: 2011. CEA-Expressing Liver Metastases Safety Study of Intrahepatic Infusions of Anti-CEA Designer T Cells (HITM) https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT01373047 . [Google Scholar]

- 79.National Library of Medicine (NLM) ClinicalTrials.gov ID, NCT01897415. NLM; Bethesda, MD: 2013. Autologous Redirected RNA Meso CAR T Cells for Pancreatic Cancer. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT01897415 . [Google Scholar]

- 80.National Library of Medicine (NLM) ClinicalTrials.gov ID, NCT03323944. NLM; Bethesda, MD: 2017. CAR T Cell Immunotherapy for Pancreatic Cancer. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT03323944 . [Google Scholar]

- 81.National Library of Medicine (NLM) ClinicalTrials.gov ID, NCT03159819. NLM; Bethesda, MD: 2017. Clinical Study of CAR-CLD18 T Cells in Patients With Advanced Gastric Adenocarcinoma and Pancreatic Adenocarcinoma. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT03159819 . [Google Scholar]

- 82.National Library of Medicine (NLM) ClinicalTrials.gov ID, NCT03393936. NLM; Bethesda, MD: 2018. Safety and Efficacy of CCT301 CAR-T in Adult Subjects With Recurrent or Refractory Stage IV Renal Cell Carcinoma. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT03393936 . [Google Scholar]

- 83.National Library of Medicine (NLM) ClinicalTrials.gov ID, NCT03873805. NLM; Bethesda, MD: 2019. PSCA-CAR T Cells in Treating Patients With PSCA+ Metastatic Castration Resistant Prostate Cancer. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT03873805 . [Google Scholar]

- 84.National Library of Medicine (NLM) ClinicalTrials.gov ID, NCT03089203. NLM; Bethesda, MD: 2017. CART-PSMA-TGFβRDN Cells for Castrate-Resistant Prostate Cancer. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT03089203 . [Google Scholar]

- 85.National Library of Medicine (NLM) ClinicalTrials.gov ID, NCT04020575. NLM; Bethesda, MD: 2020. Autologous huMNC2-CAR44 or huMNC2-CAR22 T Cells for Breast Cancer Targeting Cleaved Form of MUC1 (MUC1*) https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT04020575 . [Google Scholar]

- 86.National Library of Medicine (NLM) ClinicalTrials.gov ID, NCT03585764. NLM; Bethesda, MD: 2018. MOv19-BBz CAR T Cells in aFR Expressing Recurrent High Grade Serous Ovarian, Fallopian Tube, or Primary Peritoneal Cancer. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT03585764 . [Google Scholar]

- 87.National Library of Medicine (NLM) ClinicalTrials.gov ID, NCT02498912. NLM; Bethesda, MD: 2015. Cyclophosphamide Followed by Intravenous and Intraperitoneal Infusion of Autologous T Cells Genetically Engineered to Secrete IL-12 and to Target the MUC16ecto Antigen in Patients With Recurrent MUC16ecto+ Solid Tumors. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT02498912 . [Google Scholar]

- 88.National Library of Medicine (NLM) ClinicalTrials.gov ID, NCT02792114. NLM; Bethesda, MD: 2016. T-Cell Therapy for Advanced Breast Cancer. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT02792114 . [Google Scholar]

- 89.National Library of Medicine (NLM) ClinicalTrials.gov ID, NCT02442297. NLM; Bethesda, MD: 2016. T Cells Expressing HER2-specific Chimeric Antigen Receptors(CAR) for Patients With HER2-Positive CNS Tumors (iCAR) https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT02442297 . [Google Scholar]

- 90.National Library of Medicine (NLM) ClinicalTrials.gov ID, NCT03696030. NLM; Bethesda, MD: 2018. HER2-CAR T Cells in Treating Patients With Recurrent Brain or Leptomeningeal Metastases. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT03696030 . [Google Scholar]

- 91.National Library of Medicine (NLM) ClinicalTrials.gov ID, NCT02414269. NLM; Bethesda, MD: 2015. Malignant Pleural Disease Treated With Autologous T Cells Genetically Engineered to Target the Cancer-Cell Surface Antigen Mesothelin. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT02414269 . [Google Scholar]

- 92.National Library of Medicine (NLM) ClinicalTrials.gov ID, NCT01044069. NLM; Bethesda, MD: 2010. Precursor B Cell Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia (B-ALL) Treated With Autologous T Cells Genetically Targeted to the B Cell Specific Antigen CD19. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT01044069 . [Google Scholar]

- 93.National Library of Medicine (NLM) ClinicalTrials.gov ID, NCT00466531. NLM; Bethesda, MD: 2007. Treatment of Relapsed or Chemotherapy Refractory Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia or Indolent B Cell Lymphoma Using Autologous T Cells Genetically Targeted to the B Cell Specific Antigen CD19. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT00466531 . [Google Scholar]

- 94.National Library of Medicine (NLM) ClinicalTrials.gov ID, NCT00586391. NLM; Bethesda, MD: 2009. CD19 Chimeric Receptor Expressing T Lymphocytes In B-Cell Non Hodgkin's Lymphoma, ALL & CLL (CRETI-NH) https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT00586391 . [Google Scholar]

- 95.National Library of Medicine (NLM) ClinicalTrials.gov ID, NCT00608270. NLM; Bethesda, MD: 2009. CD19 Chimeric Receptor Expressing T Lymphocytes In B-Cell Non Hodgkin's Lymphoma, ALL & CLL (CRETI-NH) https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT00608270 . [Google Scholar]

- 96.National Library of Medicine (NLM) ClinicalTrials.gov ID, NCT02315612. NLM; Bethesda, MD: 2014. Anti-CD22 Chimeric Receptor T Cells in Pediatric and Young Adults With Recurrent or Refractory CD22-expressing B Cell Malignancies. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT02315612 . [Google Scholar]

- 97.National Library of Medicine (NLM) ClinicalTrials.gov ID, NCT01722149. NLM; Bethesda, MD: 2015. Re-directed T Cells for the Treatment (FAP)-Positive Malignant Pleural Mesothelioma. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT01722149 . [Google Scholar]

- 98.National Library of Medicine (NLM) ClinicalTrials.gov ID, NCT02311621. NLM; Bethesda, MD: 2014. Engineered Neuroblastoma Cellular Immunotherapy (ENCIT)-01. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT02311621 . [Google Scholar]

- 99.National Library of Medicine (NLM) ClinicalTrials.gov ID, NCT03274219. NLM; Bethesda, MD: 2017. Study of bb21217 in Multiple Myeloma. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT03274219 . [Google Scholar]

- 100.National Library of Medicine (NLM) ClinicalTrials.gov ID, NCT00881920. NLM; Bethesda, MD: 2009. Kappa-CD28 T Lymphocytes, Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia, B-cell Lymphoma or Multiple Myeloma, CHARKALL (CHARKALL) https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT00881920 . [Google Scholar]

- 101.National Library of Medicine (NLM) ClinicalTrials.gov ID, NCT03939026. NLM; Bethesda, MD: 2019. KSafety and Efficacy of ALLO-501 Anti-CD19 Allogeneic CAR T Cells in Adults With Relapsed/Refractory Large B Cell or Follicular Lymphoma (ALPHA) https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT03939026 . [Google Scholar]

- 102.National Library of Medicine (NLM) ClinicalTrials.gov ID, NCT03666000. NLM; Bethesda, MD: 2019. Dose-escalation, Dose-expansion Study of Safety of PBCAR0191 in Patients With r/r NHL and r/r B-cell ALL. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT03666000 . [Google Scholar]

- 103.National Library of Medicine (NLM) ClinicalTrials.gov ID, NCT04035434. NLM; Bethesda, MD: 2019. A Safety and Efficacy Study Evaluating CTX110 in Subjects With Relapsed or Refractory B-Cell Malignancies (CARBON) https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT04035434 . [Google Scholar]

- 104.National Library of Medicine (NLM) ClinicalTrials.gov ID, NCT03190278. NLM; Bethesda, MD: 2017. Study Evaluating Safety and Efficacy of UCART123 in Patients With Relapsed/Refractory Acute Myeloid Leukemia (AMELI-01) https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT03190278 . [Google Scholar]