Abstract

The wild-type strain of Clostridium beijerinckii NCIMB 8052 tends to degenerate (i.e., lose the ability to form solvents) after prolonged periods of laboratory culture. Several Tn1545 mutants of this organism showing enhanced long-term stability of solvent production were isolated. Four of them harbor identical insertions within the fms (def) gene, which encodes peptide deformylase (PDF). The C. beijerinckii fms gene product contains four diagnostic residues involved in the Zn2+ coordination and catalysis found in all PDFs, but it is unusually small, because it lacks the dispensable disordered C-terminal domain. Unlike previously characterized PDFs from Escherichia coli and Thermus thermophilus, the C. beijerinckii PDF can apparently tolerate N-terminal truncation. The Tn1545 insertion in the mutants is at a site corresponding to residue 15 of the predicted gene product. This probably removes 23 N-terminal residues from PDF, leaving a 116-residue protein. The mutant PDF retains at least partial function, and it complements an fms(Ts) strain of E. coli. Northern hybridizations indicate that the mutant gene is actively transcribed in C. beijerinckii. This can only occur from a previously unsuspected, outwardly directed promoter located close to the right end of Tn1545. The Tn1545 insertion in fms causes a reduction in the growth rate of C. beijerinckii, and, associated with this, the bacteria display an enhanced stability of solvent production. The latter phenotype can be mimicked in the wild type by reducing the growth rate. Therefore, the observed amelioration of degeneration in the mutants is probably due to their reduced growth rates.

Peptide deformylase (PDF; E.C. 3.5.1.27) is the enzyme that removes the N-formyl moiety from N-formylmethionine at the N termini of nascent polypeptides, giving formate and deformylated polypeptides as reaction products (1). In several eubacteria, including Escherichia coli, Thermus thermophilus, and Clostridium acetobutylicum, PDF is encoded by the fms (def) gene, which is cotranscribed with the gene encoding methionyl-tRNAfMet formyltransferase (2, 15, 20, 21). Essentiality has been demonstrated in E. coli (21). Although the level of overall sequence conservation between the deduced gene products from different bacteria is generally rather low, three motifs (HEXXH, EGCLS, and GXGXAAXQ) are absolutely conserved (24). They form the catalytic center of the protein and include residues C90, H132, and H136 involved in Zn2+ coordination and E133 involved in catalysis (residues are numbered in accordance with the numbering of the E. coli PDF) (24). The removal of 23 residues from the disordered C-terminal domain of the E. coli PDF had no deleterious effect on enzyme activity, whereas activity was abolished by the removal of more than two residues from the N terminus (23). Very similar results have recently been obtained with the T. thermophilus enzyme (24).

The Clostridium beijerinckii fms gene was isolated during the characterization of a strain that is less prone to degeneration than the wild type. Degeneration is a term used to describe the loss of solvent-producing capacity to which this organism is particularly prone when grown on a rich medium with a readily metabolized carbon source (17, 18). This undesirable characteristic has been encountered in other solvent-producing clostridia, including C. acetobutylicum (17, 31). Degeneration is also well known in other organisms such as streptomycetes, in which the ability to hyperproduce antibiotics is frequently unstable (14).

A number of different mechanisms of strain degeneration can be distinguished in clostridia (19). Mutants of C. acetobutylicum lacking solvent-producing enzymes are, by definition, degenerate (3, 10, 26). Such mutants can arise by the loss of a 210-kbp plasmid on which reside several of the genes encoding enzymes specifically required for solvent production (12, 13, 31). In C. beijerinckii NCIMB 8052, the terminal fermentation enzymes are not plasmid encoded (37) and are therefore less susceptible to deletion or loss. Nevertheless, this organism is more prone to degeneration than C. acetobutylicum ATCC 824 (39). In C. beijerinckii NCIMB 8052 solvent production is under the control of the Spo0A transcription factor, which is a global regulator of post-exponential-phase gene expression (16), and spo0A disruption mutants are therefore degenerate (4, 37, 38). However, the reason(s) why C. beijerinckii is more susceptible to degeneration than C. acetobutylicum remains obscure.

In addition to strain degeneration caused by genetic alterations, C. beijerinckii cells growing rapidly in a rich medium with a high sugar concentration are unable to form solvents and spores (18, 19). During rapid growth the volatile fatty acids (VFAs), acetic and butyric acids, are formed rapidly and accumulate in the medium, lowering its pH. The rate of acid production is so rapid that the cells cannot effectively induce solvent production. The accumulated acids distribute themselves across the cell membranes according to their pKa values and the difference in pH on the two sides of the membrane. When the concentration of VFAs is high enough, the redistribution of the acids will, in effect, translocate sufficient protons to acidify the more alkaline side of the membrane. Thus, when the pH of the clostridial culture decreases below approximately 4.7 and the concentrations of acetate and butyrate are in the 20 to 30 mM range, the interiors of all the cells in the culture will become acidified below a tolerable level (32). Cellular functions will be inhibited, and viability will be lost. On the other hand, as the growth rate is reduced, the rate of acid production will also be decreased, and below a critical value (“tipping point”) the cells are able effectively to switch to solvent production and convert the accumulated acids to the nonacidic end products butanol and acetone. Thereafter, the concentration of VFAs in the medium will decrease, the pH will rise, and overacidification of the cells’ interiors and cell death will be averted.

The imbalance between acid production and the initiation of solvent production during rapid growth is being explored by isolating Tn1545 insertion mutants of C. beijerinckii NCIMB 8052 that are less prone to degeneration than the wild type (18, 19). In this paper we characterize four independently isolated strains that harbor identical Tn1545 insertions in fms. The resulting impairment of PDF expression and/or activity causes a decrease in growth rate, which is associated with a reduced tendency to degenerate. The mutant phenotype can be mimicked in the wild-type strain by manipulating the growth rate.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Growth of bacteria, measurement of growth rates, and analysis of fermentation end products.

The methods used for growing the cells and assaying their fermentation end products have been described previously (18). Antibiotics were added to the following concentrations: for E. coli; ampicillin, 50 μg/ml; tetracycline, 20 μg/ml; kanamycin, 50 μg/ml; for C. beijerinckii: erythromycin, 10 μg/ml.

Characterization of clostridial DNA adjacent to Tn1545 in mutant A10.

The left end of 25.3-kbp transposon Tn1545 contains the aphA-3 gene (5). Its associated kanamycin resistance phenotype (Kmr) is expressed in both gram-positive and gram-negative organisms (33). The sizes of HindIII junction fragments containing the left end of Tn1545 were determined by hybridization (30) with aphA-3-containing probe pAT187 (33, 35), labeled with digoxigenin (Genius kit; Boehringer Mannheim, Indianapolis, Ind.). HindIII digestion of A10 DNA yielded a fragment of 7.7 ± 0.1 kbp (mean ± standard deviation; n = 12) that hybridized with pAT187. This fragment was cloned into pBlueScript KS+ (Stratagene, La Jolla, Calif.) by selecting for Kmr transformants of E. coli DH5α. Several transformants containing apparently identical plasmids were obtained. The clostridial DNA flanking the left end of the transposon was isolated from one of them (pEK19), and the sequence of a ca. 450-bp segment adjacent to the site of Tn1545 insertion was determined for both strands by the dideoxy chain termination method (27).

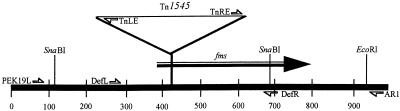

Ligation-mediated PCR amplification was used to isolate Tn1545 right-end junction fragments. DNA from strains harboring Tn1545 was digested with HindIII and ligated with HindIII-digested pMTL20 (9). PCR amplification was carried out with primers TnRE (5′CGTGAAGTATCTTCCTACAGT3′), specific for the right end of Tn1545 (34), and M13 -40. Rare ligation products, where the appropriate vector end had ligated with the appropriate Tn1545 junction fragment end, were amplified, giving a ca. 2-kb fragment. This was cloned in plasmid pXcm-Km12 (7), which acts as a T vector when cut with XcmI. The insert was excised from a representative plasmid (pAR12) as a ca. 2,000-bp BamHI fragment and cloned into pMTL20 for sequencing. Additional oligonucleotides used for sequencing and PCR analysis of strains were the standard M13 forward and reverse primers, TnLE (5′GGATAAATCGTCGTATCAAAGG3′ [34]), TnRE, AR1 (5′TTAACACCCCAAATCTACC3′), PEK19L (5′TAGCGATTGATATTCTAATG3′), DefR (5′GTTTCTATCAAGATACGTAACC3′), and DefL (5′AAGAATGTGTATGCCAAGCC3′). The positions and orientations of these primers in relation to the DNA segment under investigation are shown in Fig. 1.

FIG. 1.

Diagram of the chromosomal region disrupted by Tn1545 insertion in C. beijerinckii A10. The positions of PCR primers in relation to the fms gene and the Tn1545 insertion in strain A10 are indicated. The positions of landmark SnaBI and EcoRI restriction sites are indicated. Numerical values are in units of base pairs. Tn1545 is not drawn to scale. The downstream ORF referred to in the text starts at position 978.

Northern blots.

Bacteria were washed with 0.1 M sodium phosphate buffer, pH 7.0, and RNA was extracted with an RNeasy kit (Qiagen Inc., Santa Clarita, Calif.) according to the manufacturer’s directions. The RNA was treated with RNase-free DNase (Stratagene), repurified on an RNeasy column, and size fractionated by gel electrophoresis according to the manufacturer’s instructions. A 32P-labeled fms probe was prepared by using the 2-kbp insert isolated by BamHI digestion of pAR12. A second 32P-labeled probe, consisting of C. beijerinckii sequences lying entirely within the fms coding sequence, together with about 200 bp of Tn1545 DNA, was prepared by PCR amplification with the TnRE and DefR primers, with pAR12 (Fig. 1) as the template. Hybridizations were carried out by standard methods.

Complementation.

Primers AR1 and either PEK19L or TnRE were employed to isolate the fms gene from the wild-type and A10 strains, respectively. The 905-bp fragment from the wild type and the 654-bp fragment from the mutant were initially cloned into the T vector pXcm-Km12 (8). The wild-type gene was subcloned as a BamHI fragment into pMTL20 (9) to yield pDEFr. It was then isolated from pDEFr as a SmaI-AatII fragment (by using sites in the vector polylinker) and subcloned into pMTL21 (9) to yield plasmid pDEFf. The A10 mutant gene was subcloned in both orientations in pMTL20 as a ca. 600-bp EcoRI fragment, yielding plasmids pAREf and pAREr. The suffix f indicates that the insert is oriented such that transcription can occur from the vector lacZ promoter; the suffix r indicates the opposite orientation. The integrity of the inserts of all four plasmids was verified by sequencing.

The four recombinant plasmids, each containing the wild-type or mutant fms gene in one of the possible orientations, were transformed into the fms(Ts) PAL421Tr strain of E. coli (21), with selection for ampicillin resistance at 30°C. The fms gene has been deleted from the chromosome of this strain; it resides, instead, on a thermosensitive plasmid, and as a result, the strain is unable to grow at 42°C. Apr transformants were tested for fms expression by being streaked on Luria-Bertani plates containing either ampicillin or tetracycline and by being incubated at 42°C overnight.

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The sequence of the C. beijerinckii fms gene has been deposited in the GenBank and EMBL databases under accession no. Z96934.

RESULTS

Characterization of the Tn1545 insertion in strain A10.

Tn1545 has a distinct preference for A+T-rich target sites whose sequences resemble those of the transposon ends (11, 25, 29). As a result, most insertions in C. beijerinckii affect the very A+T-rich intergenic regions and are phenotypically silent (38). However, two phenotypes have previously been reported for one particular mutant, denoted A10, which harbors a single copy of Tn1545 (19). A10 has an altered colony morphology (fewer colonial outgrowths) and shows enhanced viability (because it produces less VFAs than the wild type) when grown in a rich medium with a high sugar content. Both of these phenotypes enhance the long-term stability of solvent production by this strain.

To investigate the genetic defect associated with these A10 phenotypes, DNA segments immediately adjacent to the transposon ends were obtained. Plasmids pEK19 and pAR12 (see Materials and Methods) contain the left- and right-end junction fragments, respectively, of Tn1545 from strain A10. DNA sequences immediately adjacent to the transposon ends were characterized; from these sequences PCR primers PEK19L and AR1 were designed and then employed to isolate the corresponding, uninterrupted 905-bp DNA segment from the wild type (Fig. 1). Additional sequence information, extending 479 bp to the right of the EcoRI site in Fig. 1, was obtained from pAR12.

The interrupted gene is fms.

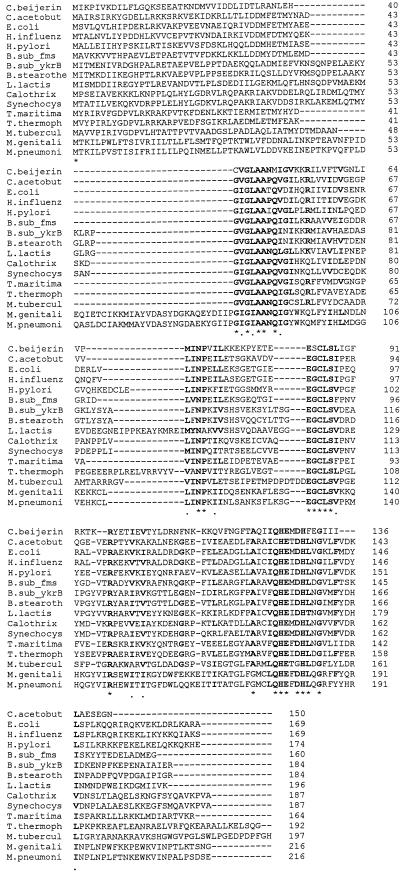

The 411-bp open reading frame (ORF) interrupted by Tn1545 insertion in A10 is similar (30 to 37% identity; 53 to 60% similarity) to several fms genes, encoding PDFs from a variety of different bacteria (Fig. 2). However, the predicted product of the C. beijerinckii gene shows some unusual features (Fig. 2). First, the GXGXAAXQ and EGCLS motifs found in other PDFs are present in slightly modified forms (CVGLAANM and ESCLS [boldface type indicates conserved amino acids]). Second, the predicted gene product lacks the dispensable C-terminal domain. There is no obvious transcription terminator in the 182-bp intergenic region that separates fms from the next gene downstream, whose product’s 148 predicted N-terminal residues (extent of the currently available sequence information) show no significant similarity to other sequences in the databases.

FIG. 2.

Multiple sequence alignment of bacterial PDFs. The sequences are (in order from top to bottom) from the following organisms (database accession numbers are in parentheses): C. beijerinckii (Z96934), C. acetobutylicum (U52368), E. coli (X77091), Haemophilus influenzae (U32745), Helicobacter pylori (AE000591), B. subtilis (Y10304 and Y13937), B. stearothermophilus (Y10549), L. lactis (L36907), Calothrix sp. (Y10305), Synechocystis sp. (D90906), Thermatoga maritima (Y10306), Thermus thermophilus (X79087), Mycobacterium tuberculosis (Z84724), Mycoplasma genitalium (U39690), and Mycoplasma pneumoniae (AE000057). Residues conserved in at least 14 of the 16 sequences are marked with an asterisk, and conservative substitutions are marked with a dot. Residues conserved or conservatively substituted in at least 12 gene products are in boldface. Gene products were aligned with the MACAW (Multiple Alignment Construction and Analysis Workbench) software (28).

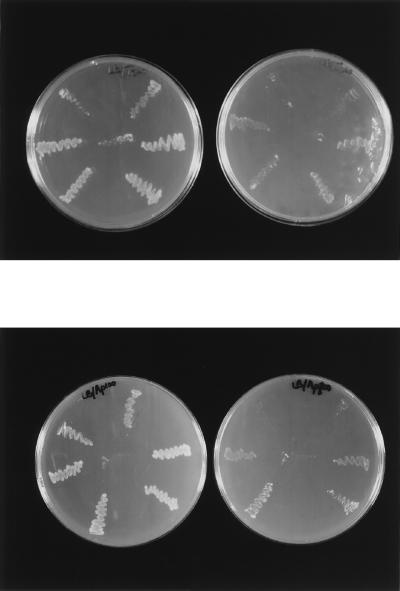

To determine whether the interrupted gene does indeed encode a functional PDF, 905 bp of the chromosomal region from the wild type characterized above, which encompasses the coding sequence, together with 315 bp of upstream DNA and 179 bp of downstream DNA, was cloned into plasmids pMTL20 and pMTL21 (9), yielding plasmids pDEFr and pDEFf, respectively (see Materials and Methods). The integrity of the inserts in these plasmids was verified by sequencing. The two plasmids were then transformed into the fms(Ts) PAL421Tr strain of E. coli (21). This strain carries a null mutation in its chromosomally located fms gene; the wild-type fms gene resides on a plasmid, which shows thermosensitive replication. Since PDF is essential for the growth of E. coli (21), this strain is unable to grow at 42°C. Both plasmids abolished the thermosensitivity of the fms(Ts) PAL421Tr strain of E. coli (Fig. 3), confirming that the C. beijerinckii gene is indeed fms. Moreover, since it was functional in both orientations, the 315-bp upstream region apparently contains sequences able to direct transcription in E. coli.

FIG. 3.

Complementation of an E. coli strain lacking PDF by recombinant plasmids harboring the C. beijerinckii fms gene. E. coli PAL421Tr-pMAKfms fmsΔ1 galK recA56 srl::Tn10 (Tcr) was transformed with plasmids pUCdef, pDEFf, pDEFr, pAREf, and pAREr. Single colonies were streaked on Luria-Bertani plates containing either tetracycline (upper panel) or ampicillin (lower panel) and incubated for 24 h at either 30 (left side) or 42°C (right side). The order of colonies on the plates is as follows: center, untransformed recipient; top right, pUCdef colony; center right, pDEFf colony; lower right, pDEFr colony; lower left, pAREr colony; center left, pAREf colony; upper left, pMTL20 colony. Complementation (ability to grow at 42°C) was conferred most strongly by pDEFr and pAREr, less strongly by pDEFf and pAREf, weakly by pUCdef (positive control), and not at all by pMTL20 (negative control, cloning vector).

A preferred insertion site for Tn1545 in fms.

Strain A10 was initially isolated by screening for mutants that do not lose viablity (because of excess VFA production) after overnight growth in a rich sugar-supplemented medium (18). When screened subsequently, A10 was found to produce fewer colonial outgrowths than the wild type. Several other mutants (E19, E46, and G11) having these same phenotypes were obtained from separate experiments (19). Their DNA gave PCR products similar to those obtained with A10 DNA (Table 1), and sequencing confirmed that all four strains harbor identical Tn1545 insertions, in the same orientation, in fms. This insertion site in fms therefore represents a favored target for Tn1545 in C. beijerinckii. The fact that several independently isolated Tn1545 mutants all have identical phenotypes and identical Tn1545 insertion points demonstrates unequivocally that the observed phenotypes result from Tn1545 insertions in fms.

TABLE 1.

Characterization of independently isolated mutants by PCR

| Strain | Size of PCR product (bp) obtained with primer paira:

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DefL + DefR (435) | PEK19L + TnLE (504) | AR1 + TnRE (654) | PEK19L + AR1 (905) | |

| NCIMB 8052 | 450 | NPb | NP | 880 |

| A10 | NP | 515 | 660 | NP |

| E19 | NP | 515 | 650 | NP |

| E46 | NP | 515 | 660 | NP |

| G11 | NP | 515 | 660 | NP |

The PCR conditions were 94°C for 4 min, followed by 25 cycles of 94°C for 30 s, 40°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 60 s, and then 72°C for 7 min. Most of these experiments were repeated at least two times. The values expected from the sequence data are in parentheses.

NP, no PCR product(s).

Tn1545 insertion in the A10 strain does not inactivate Fms.

PDF is essential for the growth of E. coli (21). However, the Tn1545 insertion near the 5′ end of fms in strain A10 was manifestly not lethal. To test for possible expression of an altered PDF, the truncated form of the gene, fused to adjacent upstream sequences from the right end of Tn1545, was isolated from the A10 strain with primers TnRE and AR1. The 654-bp PCR product was cloned into pMTL20 in both orientations, yielding plasmids pAREf and pAREr (see Materials and Methods). After the amplified DNA segments were tested to verify that they contained no PCR errors, they were introduced into the fms(Ts) PAL421Tr strain of E. coli. Both plasmids conferred the ability to grow at 42°C (Fig. 3), indicating that the Tn1545 insertion near the 5′ end of fms had not, in fact, inactivated the gene. The A10 strain must therefore produce an N-terminally modified form of PDF. Moreover, since complementation was observed with both plasmids, containing inserts in both possible orientations with respect to lacZ, the Tn1545-derived DNA upstream from the coding region apparently contains sequences able to drive gene expression in E. coli.

Several attempts were made to detect PDF activity in crude cell extracts of the wild-type and A10 strains by using the assay described by Meinnel and Blanquet (22). They were unsuccessful owing to the presence of interfering proteases that degraded the preferred substrate, N-formylMet-Ala-Ser (22).

The fms gene is expressed in strain A10.

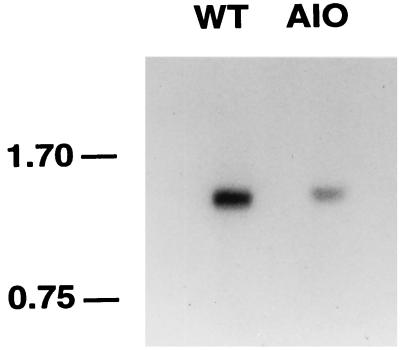

Northern hybridization experiments using two different fms probes (see Materials and Methods) confirmed that the disrupted gene is expressed in vivo (Fig. 4). In both the mutant and the wild type a ca. 1.2-kb transcript was detected by both probes. The fms coding sequence accounts for only 411 bases, suggesting that fms could be cotranscribed with another gene. In E. coli, T. thermophilus, and C. acetobutylicum, fms and fmt (encoding methionyl-tRNAfMet formyltransferase) form an operon. There is currently no evidence for a similar operon structure in C. beijerinckii; the sequenced DNA upstream (385 bp) contains no obvious ORF, and the predicted product of the partial ORF downstream (444 bp) is not similar to Fmt.

FIG. 4.

Northern blot of RNA prepared from wild-type C. beijerinckii NCIMB 8052 (WT) and C. beijerinckii A10 and probed with a DNA fragment containing fms. A single band of approximately 1.2 kb was seen in both samples. The numbers at the left identify the positions of molecular mass markers (in kilobases).

Strain A10 grows more slowly than the wild type.

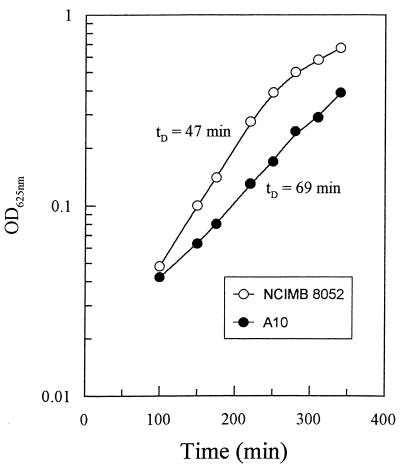

The phenotypic consequences of the production of an altered PDF were further examined by comparing growth and solvent production by the wild type and the A10 mutant in a rich medium containing glucose. The wild type grew more rapidly than the mutant (Fig. 5) and was unable to produce appreciable amounts of solvents under these conditions (Table 2). The bacteria acidified their environment by producing substantial amounts of VFAs (mainly acetate and butyrate), and it has been shown previously that bacterial concentrations of less than 10 CFU/ml are present after overnight incubation in this medium (19). In contrast, the mutant bacteria grew more slowly under these conditions; they produced appreciable amounts of solvents and retained their viability after incubation overnight (18). The mutant phenotype could be mimicked by using low concentrations of erythromycin to reduce the growth rate of the wild type in the rich medium containing glucose (Table 2). As the growth rate was reduced, the final yield of VFAs decreased and that of solvents increased. Solvent production was induced efficiently in wild-type bacteria whose growth rate had been reduced to doubling times greater than 45 min.

FIG. 5.

Growth of C. beijerinckii NCIMB 8052 and strain A10 in T6 medium. Serum bottles containing medium T6 were inoculated with overnight cultures of activated spores and the optical densities at 625 nm (OD625nm) were measured periodically as indicated in Materials and Methods. tD, doubling time.

TABLE 2.

Effect of growth rate on solvent production by C. beijerinckii NCIMB 8052 and mutant A10

| Strain | Erythro- mycin concn (μg/ml) | Doubling time (min) | OD625d at 24 h | Final pH | Total VFAsb (g/liter) | Total solventsc (g/liter) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NCIMB 8052 | 0 | 38a | 1.9 | 4.8 | 3.1 | 1.4 |

| 0.1 | 41 | 1.9 | 4.8 | 2.6 | 2.3 | |

| 0.2 | 45 | 2.6 | 4.9 | 1.0 | 3.9 | |

| 0.3 | 48 | 3.3 | 6.1 | 0.8 | 9.1 | |

| A10 | 0 | 61a | 3.2 | 6.1 | 0.8 | 9.1 |

The doubling times were significantly different (P < 0.05) in three independent determinations.

Acetic and butyric acids.

Acetone and butanol.

OD625, optical density at 625 nm.

DISCUSSION

The data presented indicate that solvent production by C. beijerinckii NCIMB 8052 can be enhanced and stabilized as a result of Tn1545 insertion close to the 5′ end of the fms structural gene encoding PDF. The fms gene is essential in E. coli (21), and presumably also in C. beijerinckii. Several different explanations for the non-lethality of the Tn1545 insertion can be considered.

First, the trivial possibility that the affected gene is not fms can be ruled out, since it complemented the fms(Ts) PAL421Tr strain of E. coli. Second, C. beijerinckii NCIMB 8052 does have an unusually large (6.7-Mbp) genome (37) which might, perhaps, contain a second, functional fms gene. There is one precedent for this, since Bacillus subtilis contains two fms-like genes (Fig. 2). One of these (ykrB), encodes a product similar to predicted gene products from Bacillus stearothermophilus and Lactococcus lactis suggesting, perhaps, that other representatives of the relatively low-G+C-content cohort of gram-positive bacteria in addition to B. subtilis may contain two fms-like genes. Although Southern hybridizations at low stringency (unpublished results) failed to reveal a second fms-like gene in C. beijerinckii, this possibility cannot be ruled out at this stage. Third, Tn1545 insertion may not have inactivated the fms gene. A10 could produce an N-terminally truncated protein via transcription from an outwardly directed promoter lying in the upstream, A+T-rich right end of Tn1545. This last hypothesis is supported by data indicating that the Tn1545-interrupted A10 gene is transcribed in vivo and, moreover, that it complements the fms(Ts) PAL421Tr strain of E. coli. Just downstream from the point of insertion of Tn1545 there is a possible AUG start codon (M24 in the wild type PDF) preceded by a purine-rich tract that could act as a ribosome binding site.

The Northern hybridization results, supported by the observed complementation of fms in E. coli by the truncated A10 gene, indicate that the right end of Tn1545 (and, presumably, the equivalent end of its close relative, Tn916) contains an outwardly directed promoter able to drive the expression of adjacent genes. Were the −10 region of this putative promoter to encompass the 6-bp host-derived coupling sequences, which vary from one Tn1545 insertion to another (6, 11, 25, 29), promoter activity could be highly variable, and even absent in some transposon insertions. Significantly, transcripts derived from promoters near the left end of Tn916 that read through the attachment site have recently been characterized (7).

The Northern hybridization results showed that the fms gene of C. beijerinckii is expressed as a ca. 1.2-kb transcript. This probably includes the gene downstream, because (i) there is no obvious transcription terminator between fms and this gene and (ii) the longer of the two probes employed for the Northern hybridizations, both of which detected a single 1.2-kb transcript (Fig. 4), also encompassed this downstream gene.

The fms gene of C. beijerinckii NCIMB 8052 is unusual in several respects. First, the 136-residue wild-type gene product lacks the disordered C-terminal domain found in other organisms. This part of the E. coli protein is dispensable and may even serve to destabilize the enzyme (23). Second, three perfectly conserved motifs occur in the fifteen other PDFs in the DNA sequence databases (Fig. 2) (24). Two of these are slightly modified in the C. beijerinckii enzyme: EGCLS becomes ESCLS and GXGXAAXQ becomes CVGLAANM (boldface type indicates conserved amino acids). In spite of these differences, residues C90, H132, and H136 involved in Zn2+ coordination and E133 involved in catalysis are absolutely conserved in all sixteen PDFs (residues numbered according to the E. coli sequence). Another unexpected feature of the C. beijerinckii PDF is that it can tolerate truncation at its N terminus without complete loss of activity. Although this region is poorly conserved among PDFs from different organisms, removal of more than two residues from the N terminus of the E. coli protein caused loss of activity (23). The N-terminal domain is also essential for activity of the T. thermophilus enzyme (24).

The A10 mutant (and the three other similar strains) grows more slowly than the wild type in a rich sugar-supplemented medium. This indicates that the Tn1545 insertion has probably reduced PDF activity and/or fms expression. The complementation experiments shown in Fig. 3 suggest that E. coli is adapted to a low level of PDF activity. Only weak complementation was observed in the positive control (E. coli gene overexpressed from the lacZ promoter on a multicopy plasmid). The better complementation observed with the heterologous C. beijerinckii gene from either the wild type or the A10 mutant was further improved when these genes were oriented such that they could not be expressed from the strong lacZ promoter.

Finally, the observed reduction in growth rate of the A10 strain (and other similar strains) provides a plausible explanation for the enhanced stability of solvent formation and the associated reduction of VFA production in all of the fms::Tn1545 strains. The tendency of the wild type to produce excess VFAs and no solvents when grown under similar conditions was also suppressed when the growth rate was reduced by using low concentrations of erythromycin (Table 2). Other treatments which reduce the bacterial growth rate (growth at lower temperature, use of a minimal medium, presence of a plasmid) are also known to have a similar effect (19, 36). The undesirable rapid degeneration of solvent production potential in C. beijerinckii NCIMB 8052 is substantially ameliorated by culturing the organism under conditions where it grows at submaximal rates.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are most grateful to Thierry Meinnel for strains, plasmids, and helpful advice concerning PDF and to Patrick Trieu-Cuot for communicating results prior to publication. We also thank Daslav Hranueli for helpful discussions and Graham Price for technical assistance.

This work was supported by the Cooperative State Research, Education, and Extension Service, U.S. Department of Agriculture, under Agreement No. 95-37308-1906 and the Chemicals and Pharmaceuticals Directorate of the U.K. BBSRC.

REFERENCES

- 1.Adams J M. On the release of the formyl group from nascent protein. J Mol Biol. 1968;33:571–589. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(68)90307-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Belouski, E., L. Gui, and G. N. Bennett. 1996. GenBank accession no. U52368.

- 3.Bertram J, Kuhn A, Durre P. Tn916-induced mutants of Clostridium acetobutylicum defective in regulation of solvent formation. Arch Microbiol. 1990;153:373–377. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brown D P, Ganova-Raeva L, Green B D, Wilkinson S R, Young M, Youngman P. Characterization of spo0A homologues in diverse Bacillus and Clostridium species reveals regions of high conservation within the effector domain. Mol Microbiol. 1994;14:411–426. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1994.tb02176.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Caillaud F, Carlier C, Courvalin P. Physical analysis of the conjugative shuttle transposon Tn1545. Plasmid. 1987;17:58–60. doi: 10.1016/0147-619x(87)90009-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Caparon M G, Scott J R. Excision and insertion of the conjugative transposon Tn916 involves a novel recombination mechanism. Cell. 1989;59:1027–1034. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90759-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Celli J, Trieu-Cuot P. Circularization of Tn916 is required for expression of the transposon-encoded transfer functions: characterization of long tetracycline-inducible transcripts reading through the attachment site. Mol Microbiol. 1998;28:103–118. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.00778.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cha J, Bishai W, Chandrasegaran S. New vectors for direct cloning of PCR products. Gene. 1993;136:369–370. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(93)90498-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chambers S P, Prior S E, Barstow D A, Minton N P. The pMTL nic− cloning vectors. I. Improved pUC polylinker regions to facilitate the use of sonicated DNA for nucleotide sequencing. Gene. 1988;68:139–149. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(88)90606-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Clark S W, Bennett G N, Rudolph F B. Isolation and characterization of mutants of Clostridium acetobutylicum ATCC 824 deficient in acetoacetyl-coenzyme A:acetate/butyrate:coenzyme A-transferase (EC 2.8.3.9) and in other solvent pathway enzymes. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1989;55:970–976. doi: 10.1128/aem.55.4.970-976.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Clewell D B, Flannagan S E. The conjugative transposons of Gram-positive bacteria. In: Clewell D B, editor. Bacterial conjugation. New York, N.Y: Plenum Press; 1993. pp. 369–393. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cornillot E, Soucaille P. Solvent-forming genes in clostridia. Nature. 1996;380:489. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cornillot E, Nair R V, Papoutsakis E T, Soucaille P. The genes for butanol and acetone formation in Clostridium acetobytlicum ATCC 824 reside on a large plasmid whose loss leads to degeneration of the strain. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:5442–5447. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.17.5442-5447.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gravius B, Bezmalinovic T, Hranueli D, Cullum J. Genetic instability and strain degeneration in Streptomyces rimosus. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1993;59:2220–2228. doi: 10.1128/aem.59.7.2220-2228.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Guillon J-M, Mechulam Y, Schmitter J-M, Blanquet S, Fayat G. Disruption of the gene for Met-tRNAfMet formyltransferase severely impairs growth of Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:4294–4301. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.13.4294-4301.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hoch J A. Regulation of the phosphorelay and the initiation of sporulation in Bacillus subtilis. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1993;47:441–465. doi: 10.1146/annurev.mi.47.100193.002301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jones D, Woods D R. Acetone-butanol fermentation revisited. Microbiol Rev. 1986;50:484–524. doi: 10.1128/mr.50.4.484-524.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kashket E R, Cao Z-Y. Isolation of a degeneration-resistant mutant of Clostridium acetobutylicum NCIMB 8052. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1993;59:4198–4202. doi: 10.1128/aem.59.12.4198-4202.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kashket E R, Cao Z-Y. Clostridial strain degeneration. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 1995;17:307–316. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Meinnel T, Blanquet S. Evidence that peptide deformylase and methionyl-tRNAfMet formyltransferase are encoded within the same operon in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:7737–7740. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.23.7737-7740.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Meinnel T, Blanquet S. Characterization of the Thermus thermophilus locus encoding peptide deformylase and methionyl-tRNAfMet formyltransferase. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:7387–7390. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.23.7387-7390.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Meinnel T, Blanquet S. Enzymatic properties of Escherichia coli peptide deformylase. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:1883–1887. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.7.1883-1887.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Meinnel T, Lazennec C, Dardel F, Schmitter J M, Blanquet S. The C-terminal domain of peptide deformylase is disordered and dispensable for activity. FEBS Lett. 1996;385:91–95. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(96)00357-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Meinnel T, Lazennec C, Villoing S, Blanquet S. Structure-function relationships within the peptide deformylase family. Evidence for a conserved architecture of the active site involving three conserved motifs and a metal ion. J Mol Biol. 1997;267:749–761. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1997.0904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Poyart-Salmeron C, Trieu-Cuot P, Carlier C, Courvalin P. The integration-excision system of the conjugative transposon Tn1545 is structurally and functionally related to those of lambdoid phages. Mol Microbiol. 1990;4:1513–1521. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1990.tb02062.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rogers P, Palosaari N. Clostridium acetobutylicum mutants that produce butyraldehyde and altered quantities of solvent. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1987;53:2761–2766. doi: 10.1128/aem.53.12.2761-2766.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sanger F, Nicklen S, Coulson A R. DNA sequencing with chain terminating inhibitors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1977;74:5463–5467. doi: 10.1073/pnas.74.12.5463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schuler G D, Altschul S F, Lipman D J. A workbench for multiple alignment construction and analyses. Proteins: Struct. Funct Genet. 1991;9:180–190. doi: 10.1002/prot.340090304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Scott J R, Churchward G G. Conjugative transposition. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1995;49:367–397. doi: 10.1146/annurev.mi.49.100195.002055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Southern E. Detection of specific sequences among DNA fragments separated by gel electrophoresis. J Mol Biol. 1975;98:503–517. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(75)80083-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Stim-Herndon K P, Nair R, Papoutsakis E T, Bennett G N. Analysis of degenerate variants of Clostridium acetobutylicum ATCC 824. Anaerobe. 1996;2:11–18. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Terracciano J S, Kashket E R. Intracellular conditions required for initiation of solvent production by Clostridium acetobutylicum. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1986;52:86–91. doi: 10.1128/aem.52.1.86-91.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Trieu-Cuot P, Carlier C, Courvalin P. Plasmid transfer by conjugation from Escherichia coli to Gram-positive bacteria. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1987;48:289–294. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Trieu-Cuot P, Carlier C, Poyart-Salmeron C, Courvalin P. An integrative vector exploiting the transposition properties of Tn1545 for insertional mutagenesis and cloning of genes from Gram-positive bacteria. Gene. 1991;106:21–27. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(91)90561-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Trieu-Cuot P, Courvalin P. Nucleotide sequence of the Streptococcus faecalis plasmid gene encoding the 3′ 5"-aminoglycoside phosphotransferase type III. Gene. 1983;23:331–341. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(83)90022-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Walter K A, Mermelstein L D, Papoutsakis E T. Host-plasmid interactions in recombinant strains of Clostridium acetobutylicum ATCC 824. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1994;123:335–341. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wilkinson S R, Young M. A physical map of the Clostridium beijerinckii (formerly Clostridium acetobutylicum) NCIMB 8052 chromosome. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:439–448. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.2.439-448.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wilkinson S R, Young D I, Morris J G, Young M. Molecular genetics and the initiation of solventogenesis in Clostridium beijerinckii (formerly Clostridium acetobutylicum) NCIMB 8052. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 1995;17:275–285. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.1995.tb00211.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Woolley D R, Morris J G. Stability of solvent production by Clostridium acetobutylicum in continuous culture: strain differences. J Appl Bacteriol. 1990;69:718–728. [Google Scholar]