Abstract

A decline in intellectual functioning (intelligence quotient [IQ]) is often observed following more severe forms of traumatic brain injury (TBI) and is a useful index for long-term outcome. Identifying brain correlates of IQ can serve to inform developmental trajectories of behavior in this population. Using magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), we examined the relationship between intellectual abilities and patterns of cortical thickness in children with a history of TBI or with orthopedic injury (OI) in the chronic phase of injury recovery. Participants were 47 children with OI and 58 children with TBI, with TBI severity ranging from complicated-mild to severe. Ages ranged from 8 to 14 years old, with an average age of 10.47 years, and an injury-to-test range of ∼1–5 years. The groups did not differ in age or sex. The intellectual ability estimate (full-scale [FS]IQ-2) was derived from a two-form (Vocabulary and Matrix Reasoning subtests) Wechsler Abbreviated Scale of Intelligence (WASI). MRI data were processed using the FreeSurfer toolkit and harmonized across data collection sites using neuroComBat procedures, while holding demographic features (i.e., sex, socioeconomic status [SES]), TBI status, and FSIQ-2 constant. Separate general linear models per group (TBI and OI) and a single interaction model with all participants were conducted with all significant results withstanding correction for multiple comparisons via permutation testing. Intellectual ability was higher (p < 0.001) in the OI group (FSIQ-2 = 110.81) than in the TBI group (FSIQ-2 = 99.81). In children with OI, bi-hemispheric regions, including the right pre-central gyrus and precuneus and bilateral inferior temporal and left occipital areas were related to IQ, such that higher IQ was associated with thicker cortex in these regions. In contrast, only cortical thickness in the right pre-central gyrus and bilateral cuneus positively related to IQ in children with TBI. Significant interaction effects were found in the bilateral temporal, parietal, and occipital lobes and left frontal regions, indicating that the relationship between IQ and cortical thickness differed between groups in these regions. Changes in cortical associations with IQ after TBI may reflect direct injury effects and/or adaptation in cortical structure and intellectual functioning, particularly in the bilateral posterior parietal and inferior temporal regions. This suggests that the substrates of intellectual ability are particularly susceptible to acquired injury in the integrative association cortex. Longitudinal work is needed to account for normal developmental changes and to investigate how cortical thickness and intellectual functioning and their association change over time following TBI. Improved understanding of how TBI-related cortical thickness alterations relate to cognitive outcome could lead to improved predictions of outcome following brain injury.

Keywords: harmonization, IQ, MRI, pediatric traumatic brain injury, surface analysis

Introduction

The intelligence quotient (IQ) is a common metric used to assess outcome in studies of pediatric traumatic brain injury (TBI).1–5 From a psychometric perspective, post-injury reductions in IQ represent a well-established finding and are significantly related to injury severity and length of time since injury.6,7 In a meta-analysis,6 intellectual impairments in the chronic phase post-injury were small for children and adults with mild or moderate TBI (d = -0.19 to -0.37) and large for patients with severe TBI (d = -0.80). Although children may demonstrate better intellectual recovery from mild TBI than adults, they are at increased risk for poorer recovery in intellectual functioning following severe TBI relative to adults.6 Anderson and colleagues8 found that overall intellectual ability in children with severe TBI remained in the low average to average range up to 10 years post-injury, with more severe injury associated with lower intellectual ability. Although extreme impairment at the group level was not noted in Anderson's sample, poorer performance was noted for adaptive abilities and speed of processing for those with a history of severe TBI.

Although total brain volume is moderately and positively associated with IQ in healthy populations, cortical thickness has demonstrated stronger associations with intelligence given its improved ability to capture fluctuating patterns of biological integrity across the cortical mantle.9 Menary and colleagues9 highlight that the association between cortical thickness and intelligence varies as a function of age and reported patterns of positive correlates with IQ in younger participants (9–16 years old) that were not observed in older participants (16–24 years old). Indeed, Shaw and colleagues10 reported that the trajectory of change in cortical thickness during maturation in childhood and adolescence more strongly relates to intelligence than does absolute thickness of the cortex. Early MRI studies suggested that cortical gray matter first increases in early childhood followed by volume loss that occurs as a normal part of development by early adolescence.11 However, more recent findings suggest that apparent thinning of the human cortex during development may instead be caused by the effects of myelination; myelination affects the contrast in gray and white matter on MRI and therefore the appearance of the cortical boundary.12

Although pediatric TBI is associated with cortical thinning,13 the relationship of thinning to post-injury alterations in IQ has been explored only to a limited extent. For example, Levan and colleagues14 reported that right frontal pole cortical thickness significantly predicted cognitive proficiency (a composite measure of the Working Memory Index and Processing Speed Index derived from the Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children, 4th edition [WISC-IV]). Volume loss in pediatric TBI is known to disproportionately affect the frontal and temporal lobes,15,16 but whether this directly impacts the changes in IQ observed post-injury is unclear. A better understanding of localized changes in cortical thickness may help to elucidate factors that contribute to lowered intellectual ability following pediatric TBI.

In the current investigation, the relation of cortical thickness to estimated full-scale IQ (FSIQ) derived from the Wechsler Abbreviated Scale of Intelligence (WASI)17 was examined in children who participated in the Social Outcomes of Brain Injury in Kids (SOBIK) investigation.16,18,19 We hypothesized that cortical thickness would be positively correlated with IQ in both TBI and orthopedically injured (OI) participants; however, because cortical integrity would likely be affected in the TBI group, we also hypothesized group differences in regional associations of cortical thickness with IQ. Participants with a history of OI were included to control for risk factors for injury (e.g., propensity for risk taking, pre-existing conditions such as attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD),20 and post-injury stress.21

Methods

Participants

This study used archival data derived from a National Institutes of Health (NIH)-funded study (SOBIK; R01 HD048946, PI: Yeates).16,22 SOBIK was a multi-site pediatric TBI outcome study that included a range of injury severity as well as a comparison group of demographically matched children with OI but not TBI. A total of 143 participants were enrolled in the study, and 106 of them were selected for the current analysis who had sustained either a TBI or OI and had usable MR data.16,18,19 Participants were 47 children with OI and 58 children with TBI, with TBI severity ranging from complicated-mild to severe as will be described. Children were recruited for the study from children's hospitals at three metropolitan sites, including the Hospital for Sick Children in Toronto (Canada), Nationwide Children's Hospital in Columbus (USA), and Rainbow Babies and Children's Hospital and MetroHealth Medical Center in Cleveland (USA). All participants completed intelligence testing, except for one TBI participant, who was excluded from subsequent analyses. All data were collected following established ethical guidelines as approved by each collection site's local institutional review board. Informed parental consent and child assent were obtained before participation, and the data set was anonymized prior to use for this study.

All participants were 8–13 years of age and were subject to the following exclusion criteria: (1) a history of more than one serious injury requiring medical treatment, (2) pre-morbid neurological disorders, (3) injury determined to be a result of child abuse or assault, (4) a history of severe psychiatric disorder requiring hospitalization, (5) sensory or motor impairments that would prevent valid administration of study measures, (6) primary language other than English, (7) any medical contraindication to MRI, or (8) home schooling or exclusive attendance in special education classrooms. Participants in the OI group were also excluded if they had a history of brain injury or if a structural lesion was observed on their MRI brain scan. Children with a history of pre-morbid learning or attentional problems were not excluded from the study.

Inclusion criteria for all participants included experiencing a mechanical injury and hospitalization; however, only those in the TBI group sustained a brain injury with severity status quantified using the Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS).23 Of the total TBI sample (n = 58), 32 (55.2%) were classified as complicated mild (GCS ≥13, but with positive day-of-injury neuroimaging findings), 9 as moderate (GCS 9–12; 15.5%), and 17 as severe (GCS 3–8; 29.3%). The OI comparison group (n = 47) consisted of participants who sustained non-skull or facial bone fractures and experienced no loss of consciousness or any other indications of brain injury. Sex was determined by self-report; see Table 1 for full demographic details.

Table 1.

Demographic Characteristics of Study Samples

| |

TBI (n = 58) |

OI (n = 47) |

Statistic |

Effect size |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | (SD) | Mean | (SD) | t test | df | p | Cohen's d | |

| Age (at injury) | 7.85 | (1.9) | 7.74 | (1.8) | -0.31 | 103 | 0.76 | 0.06 |

| Age at testing (years) | 10.44 | (1.5) | 10.51 | (1.6) | 0.22 | 103 | 0.83 | -0.05 |

| Injury to testing (years) | 2.59 | (1.2) | 2.77 | (1.0) | 0.80 | 103 | 0.43 | -0.16 |

| Parental SES | -0.28 | (0.9) | 0.35 | (1.1) | 3.38 | 103 | 0.001 | -0.63 |

| n | (%) | n | (%) | Χ2 | df | p | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex (male) |

37 |

(63.8%) |

29 |

(61.7%) |

0.05 |

1 |

0.83 |

|

| Race (White) |

45 |

(83.3%) |

40 |

(87%) |

0.30 |

2 |

0.86 |

|

| Injury mechanism: MVA/Sports/Fall |

23/16/19 |

(40/27/33%) |

3/33/11 |

(6/70/23%) |

22.5 |

2 |

<0.001

|

|

| Learning disability (Yes) |

1 |

(1.8%) |

4 |

(8.5%) |

2.6 |

1 |

0.11 |

|

| Pre-morbid ADHD (Yes) | 2 | (3.5%) | 1 | (2.2%) | 0.2 | 1 | 0.70 |

| Mean | (SD) | Mean | (SD) | F test | df | p | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WASI Composite FSIQ |

99.81 |

(13.9) |

110.81 |

(13.8) |

16.38 |

1104 |

<0.001

|

0.79 |

| WASI Vocabulary (T-score) |

48.79 |

(8.7) |

56.26 |

(9.6) |

17.38 |

1104 |

<0.001

|

0.82 |

| WASI Matrix Reasoning (T-score) |

50.26 | (11.4) | 55.85 | (7.6) | 8.30 | 1104 | 0.005 | 0.58 |

p-values in bold-faced type are less than 0.01.

d ≥ 0.20, 0.50, and 0.80 are interpreted as small, medium, and large, respectively.

TBI, traumatic brain injury; OI, orthopedic injury; SD, standard deviation; SES, socioeconomic status; MVA, motor vehicle accident; ADHD, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder; WASI, Wechsler Abbreviated Scale of Intelligence; FSIQ, full scale intellectual quotient.

Measures

The WASI17 was administered to all participants. The two-subscale version (Vocabulary [VOCAB] and Matrix Reasoning subtests) formed the basis for estimating IQ, and corrected T scores for both subtests were also calculated. The VOCAB subtest is a measure of word knowledge and verbal concept formation, and the Matrix Reasoning subtest is a measure of abstract visuospatial reasoning. Although the short form of the WASI represents an abbreviated intelligence test, its FSIQ score (i.e., FSIQ2) correlates well (r = 0.86) with the FSIQ composite from the WISC-IV.24 American norms were used for children from both the United States and Canada.

Socioeconomic status (SES) was measured using a standardized composite of parental education and occupational status, and mean family income.19,25 The SES composite is reported as a z score, with higher scores indicating higher socioeconomic status.

Image acquisition

The procedure for collection of MR images has been described in previous studies.16 In short, brain scans for all participants were performed during the chronic phase of injury (minimum = 6 months post-injury; average = 2.7 years post-injury) when acute effects on the brain were less likely to be observed.26–28 Magnetic field strength was 1.5 Tesla for all studies. Two of the collection sites used GE Signa Excite scanners, while one site used a Siemens Symphony scanner. All sites acquired thin slice T1-weighted ultrafast three-dimensional gradient echo images from each participant (magnetization-prepared rapid gradient-echo [MPRAGE] or fast spoiled gradient-echo [FSPGR] depending on scanner manufacturer) for analysis. Native voxel dimensions for the MR images were as follows: Cleveland – 0.625 × 0.625 × 1.2 mm; Columbus – 0.938 × 0.938 × 1.2 mm; Toronto – 0.469 × 0.469 × 1.2 mm.29 Pre-processing was applied uniformly to all scans for FreeSurfer (FS) analyses. At the beginning of the study, phantom imaging was performed to assess for the uniformity of image acquisition and quality across collection sites.

Image processing and harmonization procedures

All T1-weighted images were processed using the FS toolkit version 6.0 (http://surfer.nmr.mgh.harvard.edu/); details regarding the development and validation of this procedure have been previously described.30–33 In brief, images for the current project were processed through the automated pipeline and manually inspected and corrected for segmentation/topological errors per established guidelines.34

Multi-site neuroimaging studies, such as SOBIK, leverage opportunities for recruiting a greater range of participants from various populations of interest, as well as improving sample sizes for increased statistical power. However, this also introduces non-biological sources of variability, given differences in MRI scanner manufacturer, field strength, gradient non-linearity, and subject positioning in the scanner bore, which are known to increase bias and error for various neuroimaging measurements.35 Recent developments in data harmonization have shown promise at minimizing this error and improving reproducibility for downstream analyses.36 One recent approach that has been implemented for neuroimaging-based metrics, such as cortical thickness, is ComBat.37,38

Given that data utilized for this study was derived from three different collection sites that varied in scanner manufacturer, we used the neuroComBat harmonization procedures as outlined by Fortin and colleagues37 to account for potential error and variability when combining subjects from all sites/scanner types for analysis. We adapted the R implementation of their freely available code (https://github.com/Jfortin1/ComBatHarmonization) using the following approach. FreeSurfer-derived cortical thickness data for each participant was first smoothed with a 15 mm FWHM kernel and spherically registered in a common atlas space.31 Next, neuroComBat harmonization was conducted on the smoothed and registered thickness data separately for each hemisphere for each subject (e.g., ?h.thickness.fwhm15.fsaverage.mgh) with site as the primary nuisance variable (“batch” vector), while group status, FSIQ, SES, and sex were preserved during harmonization (“mod” vectors) to maintain relevant biological and behavioral effects of interest. Final harmonized thickness values were then written back into the standard FS “mgh” format for use in subsequent linear models described in the following section.

Statistical analyses

Demographic comparisons between the TBI and OI groups were conducted using independent samples t tests for age at injury, age at testing, years from injury to testing, and parental SES, and using χ2 analyses for sex, race, mechanisms of injury, and proportion of ADHD and learning disorder diagnoses. Group comparisons on WASI FSIQ, VOCAB and Matrix Reasoning were accomplished using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) models.

To evaluate the relationship between cortical thickness and WASI FSIQ-2, separate spherical statistical maps were constructed using the FS “mri_glmfit” procedure, which calculated correlation coefficients between cortical thickness at each vertex and the IQ measures. These models were conducted separately on a per-group basis (TBI, OI) to evaluate unique relationships in each group. A combined group analysis (TBI+OI) was also conducted to model potential interaction effects. Correction for multiple comparisons was accomplished using the FS implementation of Permutation Analysis of Linear Models (PALM)39 with a two-tailed analysis using 1000 permutations, and both cluster-forming and cluster-wise thresholds at p = 0.05.

Results

The groups did not differ significantly on age of injury, age at testing, testing interval, sex, race, or proportion of pre-morbid ADHD or learning disorder diagnoses. The groups did differ on SES (SES; t103 = -3.38, p = 0.001); the OI group had a higher SES. The groups also differed on mechanisms of injury (χ2 [2, n = 105) = 22.5, p < 0.001), with the TBI group experiencing more motor vehicle collisions and the OI group experiencing more sports-related injuries. Epidemiological studies have demonstrated that risk of TBI related to motorized vehicles is highest for children of lower SES and minority status,40–45 consistent with the current findings. Once mechanism of injury was accounted for, group differences in SES were no longer significant. Therefore, we did not include SES as a covariate in the neuroimaging analyses, out of concern that when a covariate is intrinsic to the condition, it can be potentially misleading to adjust for differences in the covariate.46

Regarding intellectual performance, the groups differed significantly on WASI FSIQ-2 (F1,104 = 16.38, p < 0.001), with the OI group showing higher scores than the TBI group, with moderate to large effect sizes; see Table 1 for all values and statistics.

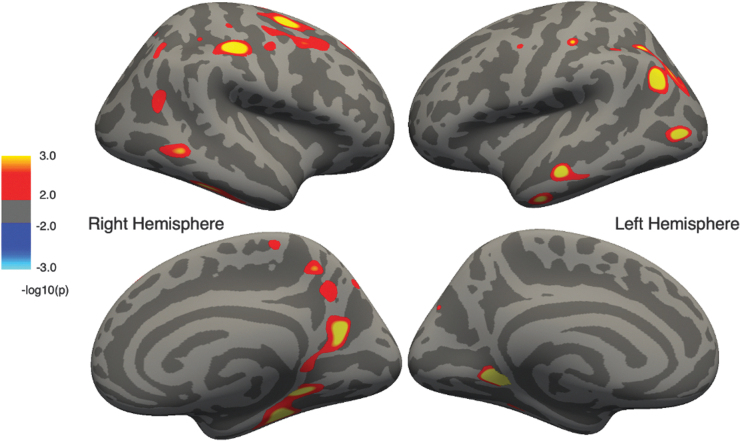

The statistical surface maps indicated that multiple regions showed associations between cortical thickness and IQ in both the OI and TBI groups separately, and remained significant after correction for multiple comparisons. As hypothesized, the OI and TBI groups differed in the spatial distribution of significant associations of cortical thickness with IQ. In OI participants (Fig. 1), positive associations were observed in multiple regions, such that higher IQ was associated with thicker cortex in these regions: right superior and middle frontal gyri, precuneus, and medial temporal regions; left anterior temporal regions; and bilaterally in pre-central, post-central, and lingual gyri, as well as in posterior parietal and lateral occipital areas.

FIG. 1.

Regions of cortical thickness positively correlated with intelligence quotient (IQ) in the orthopedic injury (OI) group corrected for multiple comparisons. Cluster color specifies the -log10 of the p value; warmer colors represent positive correlations and cooler colors represent negative correlations.

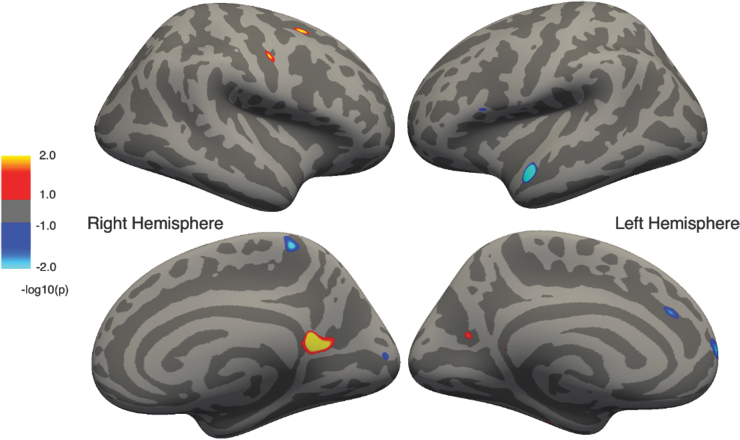

In contrast, among children with TBI (Fig. 2), positive associations between cortical thickness and IQ were noted in right hemisphere superior frontal gyrus, central sulcus, and bilateral regions of the parieto-occipital sulcal and isthmus of the cingulate. Negative associations (i.e., higher IQ associated with thinner cortex) were observed in the right hemisphere paracentral lobule and cuneus, and the left hemisphere anterior temporal, inferior frontal, and medial frontal regions.

FIG. 2.

Regions of cortical thickness positively correlated with intelligence quotient (IQ) in the traumatic brain injury (TBI) group corrected for multiple comparisons. Cluster color specifies the -log10 of the p value; warmer colors represent positive correlations and cooler colors represent negative correlations.

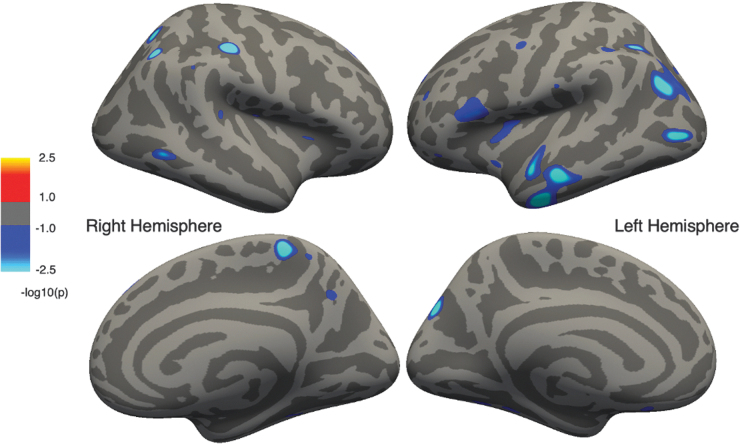

In the OI x TBI model (Fig. 3) , significant interaction effects were observed, indicating that the correlation between IQ and cortical thickness differed between groups in multiple regions: the right hemisphere post-central sulcus, paracentral lobule and precuneus; left hemisphere anterior temporal, inferior and middle frontal, pre-central, and parieto-occipital sulcal regions; and bilateral posterior parietal cortex, insula, and posterior temporal regions.

FIG. 3.

Regions showing significant group differences (traumatic brain injury [TBI] vs. orthopedic injury [OI]) in their correlation between intelligence quotient [IQ] and cortical thickness corrected for multiple comparisons. Cluster color specifies the -log10 of the p value; cooler colors represent regions of a significant interaction effect between TBI and OI.

Discussion

The current analyses revealed significant interaction effects involving the bilateral temporal, parietal, and occipital lobes and left frontal regions, indicating that the relationship between IQ and cortical thickness differed between TBI and OI groups in these regions. The differences between groups in the nature of cortical thickness associations with IQ may reflect direct injury effects and/or adaptation in cortical structure and intellectual functioning, particularly in the bilateral posterior parietal and inferior temporal regions. These findings also suggest that the substrates of intellectual ability are particularly susceptible to acquired injury in integrative association cortex.

The current findings are consistent with prior studies that demonstrate lower IQ scores observed following more severe injury.47,48 In one of the few studies of long-term intellectual outcomes of pre-school TBI, Anderson and colleagues49 found that mean FSIQ decreased at least one full standard deviation (FSIQ ≤85) 5 years following severe TBI, and that FSIQ remained lower than controls at 10 years post-injury.50 Injuries sustained in middle childhood (7–9 years of age) may be particularly associated with lower IQ scores, suggesting that this is a very vulnerable period of brain and cognitive development,47 or perhaps alternatively that the tests are more sensitive to the effects of injury in that age range. The mean age of injury (7.85 ± 1.9 years) of the current participants is within the time frame of middle childhood that may be particularly vulnerable to the effects of injury, although comparisons with other age groups were not performed in the current study.

As anticipated, significant positive correlations between cortical thickness and IQ were observed in both the OI and TBI groups, although the spatial distribution of associations differed between groups. There were few to no positive associations distributed in the left temporal and parietal lobes in TBI, although such associations were apparent for the OI group. Further, many of the associations were negative in the TBI group (e.g., right paracentral lobule, left anterior temporal, left medial frontal), although the cortical thickness of these regions was not significantly associated with IQ in the OI group. Some of these regions are among the last to develop/undergo pruning with maturation.11 There is evidence of possible failure to undergo the typical pattern of thinning in children after TBI.51 Although the current study used different methods, our findings may be additional evidence of failure to undergo the typical patterns of cortical thinning in certain regions following TBI.

The absence of a similar pattern of associations in the two groups suggests alterations of brain–behavior relationships in children who sustain a TBI. Most notably, the positive association between cortical thickness and IQ that is seen in typically developing children is largely attenuated in the TBI group, and instead there are small regions of negative associations that appear. This suggests that brain insults in the TBI group may have precipitated a shift in cortical organization, such that associations with IQ now involve more distributed regions. Assuming that brain injury precipitated a shift in cortical organization, intellectual ability following TBI may be reflective of adaptive or maladaptive mechanisms.52 The less-extensive brain–IQ correlations could either reflect damage to areas contributing to IQ (and therefore diminishing associations of cortical thickness) or displacement of cortical regions involved in cognitive ability to other areas. In the SOBIK TBI sample, we have previously shown that children with a history of TBI have diverse lesions and abnormalities, particularly within the frontotemporal distribution.16 Severity of TBI was also associated with cortical thinning in frontal and occipitoparietal regions within the SOBIK sample, although the presence of focal lesions was not associated with unique changes in cortical thickness.53 The current findings indicate a potential disruption of a typically developing association of IQ with the right frontal, left inferior temporal lobe, and the left parietal and occipital lobes, suggesting that the presence of focal frontotemporal lesions alone may not explain the spatial shift in correlational findings.

The cortical areas that survived correction for multiple comparison in the OI children in this sample are similar to regions that show correlation between IQ and cortical thickness in other pediatric studies (ages 6–18).54,55 However, the current findings are less extensive, particularly in frontal regions. Menary and colleagues9 also found similar regions showing positive correlations between cortical thickness and intellectual ability (also measured by the WASI, but for participants aged 9–24 years), also demonstrating more extensive regions of positive correlation, particularly in frontal regions. Considering that the current sample ranged from 8 to 13 years of age, more robust correlations may become apparent with increasing age, particularly following the cortical thinning that occurs around the time of puberty. The age range of our sample may reflect an inflection point in development that could explain the observed interaction effects, primarily in association cortex. The between-study differences in regional extent may be caused by differences in sample sizes, methods of correction for multiple comparison, and age ranges between the studies. The rate of cortical thinning with increasing age may also be associated with intellectual development. Longitudinal declines in FSIQ over time may show the steepest rate of cortical thinning over 2 years, in children and adolescents with mean age 11.59 years, whereas those who showed reliable gains in FSIQ within the same time frame showed no changes in cortical thickness on average.56

Limitations and future directions

The current study cannot differentiate among transfer of function, adaptation, and preservation of cortical integrity in accounting for the relationship of cortical thickness to IQ in children with TBI. Further insights would be best gained by a longitudinal study of cortical thickness and intellectual ability in the injured brain across time. Given that intellectual abilities arise from complex associations among brain development, genetics, and the environment,57 further research is needed to examine the direct and interactive effects of these several factors on the relationship of IQ to brain structure and function. TBI likely alters developmental trajectories of cortical development, depending on the severity of injury and whether the injury is focal or diffuse.52,58,59 Accordingly, future studies might examine associations between IQ and cortical thickness in relation to age at injury, time since injury, and the type and size of focal versus diffuse lesions.

In the current study, IQ was based on the WASI, which is an abbreviated measure of intellectual ability. Different findings might emerge with other measures of IQ. Notably, the relatively high FSIQ-2 scores in both groups may be in part caused by the use of American WASI norms and the inclusion of 54 Canadian children in the sample, who tend to perform above American averages on the WASI. Additionally, SES was lower on average for those participants who had a history of TBI. SES is known to relate to cognitive functioning, academic achievement, and other social and emotional outcomes.60 Therefore, SES may also influence the associations between IQ and cortical thickness. However, this notion requires further examination, ideally with a larger sample size.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the current findings demonstrate that the spatial distribution of associations between cortical thickness and IQ differ between children with TBI and children with OI but not TBI. Cortical associations with IQ may differ after TBI because of direct injury effects and/or adaptation in cortical structure and intellectual functioning. Clearer understanding of how TBI-related cortical thickness alterations relate to cognitive outcome could lead to improved predictions of outcome following brain injury.

Transparency, Rigor, and Reproducibility Summary

This study was not formally registered because this was a re-analysis of an existing data set drawn from a prior study, and the analytic plan was not formally pre-registered. A total of 143 potential participants were recruited for the study; usable imaging data were obtained from 106 and successfully analyzed in 105 (1 participant lacked WASI data). Actual sample size was 58 participants with a history of TBI and 47 with a history of OI, and the observed effect size was 0.79 for FSIQ. Imaging acquisition and analyses were performed by team members blinded to relevant characteristics of the participants, and clinical outcomes were assessed by team members blinded to imaging results. Imaging data were labeled using codes that were not linked to participant-identifying information. All equipment and software used to perform imaging and preprocessing are widely available from commercial sources. Imaging data were acquired between 2006 and 2010 as part of a multi-site study. Imaging was collected using multiple scanners, and imaging of participants in the relevant groups was distributed across devices by recruitment site. Variability among devices was assessed using phantom imaging to increase the uniformity of image acquisition and quality across collection sites. Variability was reduced using comparable MRI acquisition sequences and neuroComBat for post-processing harmonization across sites. Imaging parameters were reported previously.16 Quality control was assessed using trained raters following established guidelines.34 The key inclusion criteria are published, and the primary clinical outcome measure is an established standard in the field. Validation of the WASI includes high correlation with scores on the WISC-IV.24 Analytic codes used to conduct the analyses are available at https://surfer.nmr.mgh.harvard.edu/fswiki and GitHub, as previously described.37 The study data may be available upon request, subject to a data sharing agreement. The statistical tests used were based on the assumptions of normal distributions for parametric tests. Correction for multiple comparisons was performed using FS implementation of permutation analysis of linear models. To our knowledge, no replication or external validation studies have been performed or are planned/ongoing at this time. The content of the article will be publicly accessible through the National Institutes of Health.

Acknowledgments

We express our gratitude to Garrett Black who contributed to an earlier version of a related study using different methods. The abstract was presented at the 50th Annual Virtual Meeting of the International Neuropsychological Society (February 1–4, 2022), and the abstract was published in the December 2022 issue of the Journal of the International Neuropsychological Society along with the other abstracts that were presented at the meeting.

Authors' Contributions

Tricia L. Merkley was responsible for conceptualization (equal), formal analysis (supporting), writing – original draft (equal), and writing – review and editing (lead); Colt Halter was responsible for software, data curation, and formal analysis (supporting); Benjamin Graul was responsible for software, data curation, and writing – review and editing; Shawn D. Gale was responsible for conceptualization and writing – review and editing; Chase Junge, Madeleine Reading, Sierra Jarvis, Kaitlyn Greer, and Chad Squires were responsible for software and data curation; Erin D. Bigler was responsible for conceptualization and writing – review and editing; H. Gerry Taylor was responsible for conceptualization, methodology, investigation, supervision, project administration, funding acquisition, and writing – review and editing; Kathryn Vannatta was responsible for conceptualization, methodology, writing – review and editing, project administration, and funding acquisition; Cynthia A. Gerhardt was responsible for conceptualization, methodology, writing – review and editing, project administration, and funding acquisition; Kenneth Rubin was responsible for writing – review and editing; Terry Stancin was responsible for conceptualization and methodology; Keith Owen Yeates was responsible for conceptualization, methodology, writing – review and editing, project administration, and funding acquisition; and Derin Cobia was responsible for conceptualization, formal analysis, investigation, methodology, writing – original draft, review and editing, visualization, supervision, project administration, and data curation.

Funding Information

This study was supported by the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development grant No. R01 HD048946-01A2. Keith Owen Yeates has grant funding from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, but this is not applicable to the current study.

Author Disclosure Statement

Keith Owen Yeates is supported by the Ronald and Irene Ward Chair in Pediatric Brain Injury from the Alberta Children's Hospital Foundation. Derin Cobia currently serves as a consultant for Sage Therapeutics on a project unrelated to the present study. Erin D. Bigler is retired, emeritus professor at Brigham Young University, but does some forensic consultation. Tricia Merkley, Shawn Gale, Colt Halter, Benjamin Graul, Kaitlyn Greer, Madeline Reading, Sierra Jarvis, Chase Junge, Chad Squires, H. Gerry Taylor, Kathryn Vannatta, Cynthia A. Gerhardt, and Kenneth Rubin report no financial and personal relationships with commercial interests conflicting with this work.

References

- 1. Madaan P, Gupta D, Agrawal D, et al. Neurocognitive outcomes and their diffusion tensor imaging correlates in children with mild traumatic brain injury. J Child Neurol 2021;36(8):664–672; doi: 10.1177/0883073821996095 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Ferrazzano P, Yeske B, Mumford J, et al. Brain magnetic resonance imaging volumetric measures of functional outcome after severe traumatic brain injury in adolescents. J Neurotrauma 2021;38(13):1799–1808; doi: 10.1089/neu.2019.6918 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Sanz-Palau M, Lopez-Sala A, Palacio-Navarro A, et al. Prognostic factors and profile in traumatic brain injury in the paediatric age. Rev Neurol 2020;70(7):235–245; doi: 10.33588/rn.7007.2019393 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Crowe LM, Catroppa C, Babl FE, et al. Intellectual, behavioral, and social outcomes of accidental traumatic brain injury in early childhood. Pediatrics 2012;129(2):e262–268; doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-0438 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Shaklai S, Peretz R, Spasser R, et al. Long-term functional outcome after moderate-to-severe paediatric traumatic brain injury. Brain Inj 2014;28(7):915–921; doi: 10.3109/02699052.2013.862739 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Konigs M, Engenhorst PJ, Oosterlaan J. Intelligence after traumatic brain injury: meta-analysis of outcomes and prognosis. Eur J Neurol 2016;23(1):21–29; doi: 10.1111/ene.12719 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Cermak CA, Scratch SE, Reed NP, et al. Effects of pediatric traumatic brain injury on verbal IQ: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Int Neuropsychol Soc 2022;28(10):1091–1103; doi: 10.1017/S1355617721001296 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Anderson V, Godfrey C, Rosenfeld JV, et al. 10 years outcome from childhood traumatic brain injury. Int J Dev Neurosci 2012;30(3):217–224; doi: 10.1016/j.ijdevneu.2011.09.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Menary K, Collins PF, Porter JN, et al. Associations between cortical thickness and general intelligence in children, adolescents and young adults. Intelligence 2013;41(5):597–606; doi: 10.1016/j.intell.2013.07.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Shaw P, Greenstein D, Lerch J, et al. Intellectual ability and cortical development in children and adolescents. Nature 2006;440(7084):676–679; doi: 10.1038/nature04513 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Gogtay N, Giedd JN, Lusk L, et al. Dynamic mapping of human cortical development during childhood through early adulthood. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2004;101(21):8174–8179; doi: 10.1073/pnas.0402680101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Natu VS, Gomez J, Barnett M, et al. Apparent thinning of human visual cortex during childhood is associated with myelination. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2019;116(41):20.,750–20,759; doi:10.1073/pnas.1904931116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Merkley TL, Bigler ED, Wilde EA, et al. Diffuse changes in cortical thickness in pediatric moderate-to-severe traumatic brain injury. J Neurotrauma 2008;25(11):1343–1345; doi: 10.1089/neu.2008.0615 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Levan A, Baxter L, Kirwan CB, et al. Right frontal pole cortical thickness and social competence in children with chronic traumatic brain injury: cognitive proficiency as a mediator. J Head Trauma Rehabil 2015;30(2):E24–31; doi: 10.1097/HTR.0000000000000040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Bigler ED. Anterior and middle cranial fossa in traumatic brain injury: relevant neuroanatomy and neuropathology in the study of neuropsychological outcome. Neuropsychology 2007;21(5):515–531; doi: 10.1037/0894-4105.21.5.515 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Bigler ED, Abildskov TJ, Petrie J, et al. Heterogeneity of brain lesions in pediatric traumatic brain injury. Neuropsychology 2013;27(4):438–451; doi: 10.1037/a0032837 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Wechsler D. Wechsler Abbreviated Scale of Intelligence. The Psychological Corporation: San Antonio, TX; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Dennis M, Simic N, Gerry Taylor H, et al. Theory of mind in children with traumatic brain injury. J Int Neuropsychol Soc 2012;18(5):908–916; doi: 10.1017/S1355617712000756 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Yeates KO, Gerhardt CA, Bigler ED, et al. Peer relationships of children with traumatic brain injury. J Int Neuropsychol Soc 2013;19(5):518–527; doi: 10.1017/S1355617712001531 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Kaya A, Taner Y, Guclu B, et al. Trauma and adult attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. J Int Med Res 2008;36(1):9–16; doi: 10.1177/147323000803600102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Rabinowitz AR, Li X, McCauley SR, et al. Prevalence and predictors of poor recovery from mild traumatic brain injury. J Neurotrauma 2015;32(19):1488–1496; doi: 10.1089/neu.2014.3555 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Yeates KO, Bigler ED, Dennis M, et al. Social outcomes in childhood brain disorder: a heuristic integration of social neuroscience and developmental psychology. Psychol Bull 2007;133(3):535–556; doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.133.3.535 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Teasdale G, Jennett B. Assessment of coma and impaired consciousness. A practical scale. Lancet 1974;2(7872):81–84; doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(74)91639-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Flanagan DP, Kaufman AS. Essentials of WISC-IV Assessment. John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Yeates KO, Taylor HG. Predicting premorbid neuropsychological functioning following pediatric traumatic brain injury. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol 1997;19(6):825–837; doi: 10.1080/01688639708403763 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Blatter DD, Bigler ED, Gale SD, et al. MR-based brain and cerebrospinal fluid measurement after traumatic brain injury: correlation with neuropsychological outcome. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 1997;18(1):1–10 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Ross DE. Review of longitudinal studies of MRI brain volumetry in patients with traumatic brain injury. Brain Inj 2011;25(13–14):1271–1278; doi: 10.3109/02699052.2011.624568 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Warner MA, Youn TS, Davis T, et al. Regionally selective atrophy after traumatic axonal injury. Arch Neurol 2010;67(11):1336–1344; doi: 10.1001/archneurol.2010.149 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Bigler ED, Jantz PB, Farrer TJ, et al. Day of injury CT and late MRI findings: cognitive outcome in a paediatric sample with complicated mild traumatic brain injury. Brain Inj 2015;29(9):1062–1070; doi: 10.3109/02699052.2015.1011234 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Dale AM, Fischl B, Sereno MI. Cortical surface-based analysis. I. Segmentation and surface reconstruction. Neuroimage 1999;9(2):179–194; doi: 10.1006/nimg.1998.0395 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Fischl B, Sereno MI, Dale AM. Cortical surface-based analysis. II: Inflation, flattening, and a surface-based coordinate system. Neuroimage 1999;9(2):195–207; doi: 10.1006/nimg.1998.0396 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Fischl B, Dale AM. Measuring the thickness of the human cerebral cortex from magnetic resonance images. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2000;97(20):11.,050–11,055; doi:10.1073/pnas.200033797 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Fischl B. FreeSurfer. Neuroimage 2012;62(2):774–781; doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2012.01.021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Segonne F, Pacheco J, Fischl B. Geometrically accurate topology-correction of cortical surfaces using nonseparating loops. IEEE Trans Med Imaging 2007;26(4):518–529; doi: 10.1109/TMI.2006.887364 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Han X, Jovicich J, Salat D, et al. Reliability of MRI-derived measurements of human cerebral cortical thickness: the effects of field strength, scanner upgrade and manufacturer. Neuroimage 2006;32(1):180–194; doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2006.02.051 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Pomponio R, Erus G, Habes M, et al. Harmonization of large MRI datasets for the analysis of brain imaging patterns throughout the lifespan. Neuroimage 2020;208:116450; doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2019.116450 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Fortin JP, Cullen N, Sheline YI, et al. Harmonization of cortical thickness measurements across scanners and sites. Neuroimage 2018;167:104–120; doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2017.11.024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Johnson WE, Li C, Rabinovic A. Adjusting batch effects in microarray expression data using empirical Bayes methods. Biostatistics 2007;8(1):118–127; doi: 10.1093/biostatistics/kxj037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Winkler AM, Ridgway GR, Douaud G, et al. Faster permutation inference in brain imaging. Neuroimage 2016;141:502–516; doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2016.05.068 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Brown RL. Epidemiology of injury and the impact of health disparities. Curr Opin Pediatr 2010;22(3):321–325; doi: 10.1097/MOP.0b013e3283395f13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Howard I, Joseph JG, Natale JE. Pediatric traumatic brain injury: do racial/ethnic disparities exist in brain injury severity, mortality, or medical disposition? Ethn Dis 2005;15(4 Suppl 5):S5–51–6 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Langlois JA, Rutland-Brown W, Thomas KE. The incidence of traumatic brain injury among children in the United States: differences by race. J Head Trauma Rehabil 2005;20(3):229–238; doi: 10.1097/00001199-200505000-00006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. McKinlay A, Kyonka EG, Grace RC, et al. An investigation of the pre-injury risk factors associated with children who experience traumatic brain injury. Inj Prev 2010;16(1):31–35; doi: 10.1136/ip.2009.022483 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Parslow RC, Morris KP, Tasker RC, et al. Epidemiology of traumatic brain injury in children receiving intensive care in the UK. Arch Dis Child 2005;90(11):1182–1187; doi: 10.1136/adc.2005.072405 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Yates PJ, Williams WH, Harris A, et al. An epidemiological study of head injuries in a UK population attending an emergency department. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2006;77(5):699–701; doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2005.081901 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Dennis M, Francis DJ, Cirino PT, et al. Why IQ is not a covariate in cognitive studies of neurodevelopmental disorders. J Int Neuropsychol Soc 2009;15:331–343; doi: 10.1017/S1355617709090481 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Crowe LM, Catroppa C, Babl FE, et al. Timing of traumatic brain injury in childhood and intellectual outcome. J Pediatr Psychol 2012;37(7):745–754; doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jss070 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Neumane S, Camara-Costa H, Francillette L, et al. Functional outcome after severe childhood traumatic brain injury: results of the TGE prospective longitudinal study. Ann Phys Rehabil Med 2021;64(1):101375; doi: 10.1016/j.rehab.2020.01.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Anderson V, Catroppa C, Morse S, et al. Intellectual outcome from preschool traumatic brain injury: a 5-year prospective, longitudinal study. Pediatrics 2009;124(6):e1064-71; doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-0365 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Catroppa C, Godfrey C, Rosenfeld JV, et al. Functional recovery ten years after pediatric traumatic brain injury: outcomes and predictors. J Neurotrauma 2012;29(16):2539–2547; doi: 10.1089/neu.2012.2403 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Wilde EA, Merkley TL, Bigler ED, et al. Longitudinal changes in cortical thickness in children after traumatic brain injury and their relation to behavioral regulation and emotional control. Int J Dev Neurosci 2012;30(3):267–276; doi: 10.1016/j.ijdevneu.2012.01.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Dennis M, Spiegler BJ, Juranek JJ, et al. Age, plasticity, and homeostasis in childhood brain disorders. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 2013;37(10 Pt 2):2760–2773; doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2013.09.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Bigler ED, Zielinski BA, Goodrich-Hunsaker N, et al. The relation of focal lesions to cortical thickness in pediatric traumatic brain injury. J Child Neurol 2016;31(11):1302–1311; doi: 10.1177/0883073816654143 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Karama S, Ad-Dab'bagh Y, Haier RJ, et al. Positive association between cognitive ability and cortical thickness in a representative US sample of healthy 6 to 18 year-olds. Intelligence 2009;37(2):145–155; doi: 10.1016/j.intell.2008.09.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Karama S, Colom R, Johnson W, et al. Cortical thickness correlates of specific cognitive performance accounted for by the general factor of intelligence in healthy children aged 6 to 18. Neuroimage 2011;55(4):1443–1453; doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2011.01.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Burgaleta M, Johnson W, Waber DP, et al. Cognitive ability changes and dynamics of cortical thickness development in healthy children and adolescents. Neuroimage 2014;84:810–819; doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2013.09.038 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Toga AW, Thompson PM. Genetics of brain structure and intelligence. Annu Rev Neurosci 2005;28:1–23; doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.28.061604.135655 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Crowe LM, Catroppa C, Anderson V. Sequelae in children: developmental consequences. Handb Clin Neurol 2015;128:661–677; doi: 10.1016/B978-0-444-63521-1.00041-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Dennis M, Spiegler BJ, Simic N, et al. Functional plasticity in childhood brain disorders: when, what, how, and whom to assess. Neuropsychol Rev 2014;24(4):389–408; doi: 10.1007/s11065-014-9261-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Dearing E. Psychological costs of growing up poor. Ann N Y Acad Sci 2008;1136:324–332; doi: 10.1196/annals.1425.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]