Abstract

Open AI's ChatGPT has emerged as a popular AI language model that can engage in natural language conversations with users. Based on a qualitative research approach using semistructured interviews with 32 ChatGPT users from India, this study examined the factors influencing users' acceptance and use of ChatGPT using the unified theory of acceptance and usage of technology (UTAUT) model. The study results demonstrated that the four factors of UTAUT, along with two extended constructs, i.e. perceived interactivity and privacy concerns, can explain users' interaction and engagement with ChatGPT. The study also found that age and experience can moderate the impact of various factors on the use of ChatGPT. The theoretical and practical implications of the study were also discussed.

Keywords: ChatGPT, OpenAI, Chatbots, UTAUT, Acceptance and use

1. Introduction

With the advancements in artificial intelligence (AI), chatbots are unremittingly penetrating every aspect of human life. AI-powered chatbots are used in a broad range of applications, as varied as setting reminders, scheduling appointments [[1], [2], [3]], booking tickets [4] and providing information and assistance to people during the pandemic [5]. Chatbots are AI-powered programs enabling individuals and businesses to access information, receive support, and carry out various tasks through simple text-based conversations [6,7]. Over the years, the capabilities of chatbots have expanded, and the latest advancements in language processing technology have led to the development of highly advanced AI models, such as OpenAI's GPT-3.

GPT-3 (Generative Pretrained Transformer 3), commonly called ChatGPT, is the latest version of OpenAI's advanced language processing AI model [8]. It uses deep learning algorithms to understand and generate human-like text. One of the standout features of ChatGPT is its ability to understand and respond to questions naturally and conversationally [9]. It can generate detailed answers to complex questions, offering users a quick and effective way to get the information they need [9]. ChatGPT's proficiency is primarily attributed to its extensive pretraining process, which exposes it to diverse textual data from various sources. This vast corpus of data empowers ChatGPT to learn the nuances of language usage and context, enabling it to respond intelligently to various queries, from casual everyday conversations to technical and specialised topics ([10]). Additionally, ChatGPT continuously learns from user interactions, refining its responses over time and enhancing its language generation capabilities. This technology has revolutionised the chatbot industry, offering businesses a highly sophisticated and effective way to communicate with customers and clients [11]. Unlike traditional chatbots, the key to ChatGPT's success is its ability to generate text based on the context of previous inputs. It has been trained on a massive amount of diverse data, allowing it to understand and generate a wide range of text, from casual conversation to technical writing [9].

Given its advantages over traditional chatbots, ChatGPT has emerged as the fastest-growing app in the world, with 100 Million users within two months after its launch [12]. It has even surpassed social media platforms like Instagram and TikTok regarding adoption rates [13]. Some commentators predicted that ChatGPT could evolve as an alternative for Google shortly [14], and such fears have made Google launch its AI-enabled chatbot, Bard, as a rival to ChatGPT [15]. Some early adopters and researchers believe that ChatGPT can potentially render certain professions in the content creation domain obsolete [8,16]. This belief is based on ChatGPT's ability to produce high-quality responses to diverse challenges, such as solving coding problems and providing precise answers to exam questions [17].

The following aspects of the ChatGPT motivated us to undertake the current research. Firstly, irrespective of their discipline, available limited studies [[18], [19], [20], [21]] and anecdotal articles [[22], [23], [24]] suggest that ChatGPT provides numerous advantages to a diverse group of users. Nonetheless, it is crucial to gauge the early adopter sentiments since it is a new technology. Early adopters, the most enthusiastic and influential product users, can shape the overall perception of new technology with their opinions and sentiments [25,26]. This feedback can offer valuable insights into the potential triumph or setback of the product [27].

Secondly, being the first to use new technology, early adopters tend to be the ones who encounter any initial issues or problems. However, their feedback can be invaluable in identifying and resolving these issues before they become widespread [28]. For this reason, exploring the acceptance and usage of early adopters, especially for disruptive technologies like ChatGPT, is essential as it can increase the tool's chances of success in the market.

The current study aims to investigate the acceptance and usage of ChatGPT, based on the Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology (UTAUT) model. The following are the four critical contributions of this research: This study is one of the first to apply the UTAUT model to the context of ChatGPT. This model provides a comprehensive framework for examining the factors that influence the acceptance and usage of technology [29,30] and was selected for this study due to its widespread use in technology adoption research [31]. Second, this research provides a detailed analysis of ChatGPT usage by examining the influence of various UTAUT factors, including performance expectancy, effort expectancy, social influence, facilitating conditions, and intention to use. Third, the results of this study can be used by ChatGPT developers to improve the model's design and functionality and better understand user behaviour and needs. Finally, the study provides insights into adopting and using AI-based language models and contributes to the growing literature on AI technology acceptance and usage. The current research contributes to the technology acceptance and usage domain by comprehensively examining ChatGPT acceptance and usage based on the UTAUT model by a qualitative intervention. ChatGPT developers can use the results of this research to improve the model's design and functionality and help the AI community better to understand the adoption and usage of AI technologies.

2. Literature review

2.1. Chatbots and user engagements

Chatbots have become ubiquitous in modern technology, but their history dates back several decades. A chatbot is a computer program designed to simulate conversation with human users through text or voice-based interactions [32]. Chatbots are powered by artificial intelligence (AI) and natural language processing (NLP) technologies, allowing them to understand and respond to user input in a human-like manner [33]. NLP also provide the affordances of chatbots to understand and interpret human language, including its nuances, idioms, and cultural references [34,35]. This is accomplished through machine learning algorithms, statistical models, and linguistic rules [36]. Advanced machine-learning algorithms and natural language processing techniques power today's chatbots. They can understand complex language and context and learn from previous interactions to improve their responses over time [[37], [38], [39]].

The earliest chatbots were rule-based and limited in their abilities. They could only respond to pre-programmed commands and had a limited scope of understanding natural language [34,40]. However, with machine learning and natural language processing advancement, chatbots have become more intelligent and capable of handling complex tasks. One of the most significant developments in chatbot technology was the usage of neural networks [41]; [42]. Neural networks allow chatbots to learn from data and improve their responses over time [41]. This led to the development of advanced chatbots that could understand natural language and context, provide personalised recommendations, and handle complex conversations [43]; [44].

From the earliest text-based programs to today's AI-powered virtual assistants, chatbots have become sophisticated communication tools, automation, and customer support tools. The first chatbot, Eliza, was created in 1966 by Joseph Weizenbaum, a computer scientist at MIT [45]. Eliza was a simple program that used natural language processing techniques to mimic a human therapist [46]. Users could type in their problems, and Eliza would respond with empathetic statements and probing questions. Eliza was a groundbreaking experiment in AI and natural language processing, and it sparked a wave of interest in chatbots [47]. Over the next few decades, researchers created increasingly sophisticated chatbots, such as Parry, which simulated a patient with paranoid schizophrenia [48], and Jabberwacky, which used machine learning to generate responses based on previous conversations [[32], [49]].

Chatbots have a variety of applications, from customer service to personal assistants to entertainment. In recent years, they have become increasingly popular in the business world to automate customer support and reduce the workload on human agents [50,51]. One of the most common uses for chatbots is e-commerce, where they can help customers find products, answer questions about shipping and returns, and even make purchases [52,53]. Many businesses use chatbots on their websites and social media accounts to provide 24/7 customer support without requiring a large team of human agents [54]. More advanced chatbots are used in the healthcare, finance, and education industries to provide personalised assistance and support [55]; Wang et al., 2022). As AI technology advances, we can expect to see even more sophisticated chatbots with a wide range of applications in various industries [56]; [57]. The success of these popular chatbots has demonstrated the value of AI in improving customer experiences and streamlining business operations.

2.2. ChatGPT: an overview of the AI-powered language model

ChatGPT is a significant language model developed by OpenAI capable of generating human-like responses to text-based input. ChatGPT is based on the GPT (Generative Pre-trained Transformer) architecture, first introduced by OpenAI in 2018 [58]. The GPT architecture is a type of transformer-based neural network trained on large amounts of text data, allowing it to generate coherent and grammatically correct text [59,60]. The GPT-2 model, released by OpenAI in 2019, gained widespread attention due to its ability to generate high-quality text that was often difficult to distinguish from human-generated text [61]. In June 2020, OpenAI released the ChatGPT model, designed explicitly for conversational applications [9]. ChatGPT was trained on a large dataset of conversational data and can generate human-like responses to text-based input [9]. The model is built on the GPT-2 architecture but with modifications that allow it to understand the conversational context better and generate more natural-sounding responses [62].

ChatGPT has many potential applications, including customer service, virtual assistants, and chatbots [63]. ChatGPT can be used to provide instant and personalised customer service. It can understand natural language and provide tailored responses to the customer's needs [9]; [63]. This can help businesses save time and resources by automating routine customer service tasks and providing efficient customer support. ChatGPT can create virtual assistants capable of understanding and responding to natural language input [64]. These ChatGPT-enabled virtual assistants can be used in various applications, including personal assistance, scheduling, and productivity.

ChatGPT currently supports several languages, but as its language processing capabilities improve, we expect it to be used in even more languages [9,62]. This will enable it to support a broader range of users in different parts of the world. Hence, ChatGPT can improve language translation by generating more natural-sounding by capturing the nuances of the source language and conveying them accurately in the target language [65]. This can include aspects such as tone, style, and cultural references that can be challenging to translate accurately using traditional rule-based or statistical methods.

Researchers and policy analysts argue that ChatGPT can be adopted to enhance teaching and learning in various ways. One of the most promising applications of ChatGPT is personalised tutoring and learning support [66]. ChatGPT can analyse student performance data and provide tailored feedback and guidance to help students improve their skills and knowledge [67]. It can also answer student questions in real time, providing a more interactive and engaging learning experience. ChatGPT can also automate routine tasks like grading and feedback [55,66]. This can help to save time and improve efficiency, allowing educators to focus on more strategic tasks such as curriculum design and student engagement. ChatGPT can also provide virtual office hours, enabling students to interact with their instructors and receive support outside class time [68]. ChatGPT has the potential to revolutionise knowledge discovery by making it easier to access and analyse large amounts of information. ChatGPT can process and analyse unstructured data, such as academic journals and research papers, and provide relevant insights and information in a conversational format [69]; [10]. This can help researchers and academics to identify patterns and connections that traditional data analysis techniques might miss.

Despite its potential, there are several challenges and limitations to using ChatGPT in academics and research. One of the main challenges is the quality and accuracy of the data used to train ChatGPT [70]. If the data is biased or incomplete, this can lead to inaccurate or incomplete responses from ChatGPT. Another challenge is the lack of transparency and interpretability of ChatGPT's decision-making process [71]. ChatGPT is a complex machine-learning model, and it cannot be easy to understand how it arrives at its responses [71]. This can be a particular concern in academic and research contexts, where transparency and interpretability are essential for ensuring the validity and reliability of research findings [10,70]. Finally, there is the challenge of ensuring data privacy and security. ChatGPT operates on large amounts of data, and it is essential to ensure that this data is handled securely and responsibly to protect the privacy of individuals and organisations [72]. Despite these challenges, the usage of ChatGPT in academics and research will likely continue to grow in the coming years. Hence, more research is required on how emerging-market consumers interact with this path-breaking AI technology.

3. Theoretical framework

The current study uses Venkatesh et al.’s [73] UTAUT model as a guiding theoretical framework. UTAUT (Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology) was proposed by Venkatesh, along with co-authors Morris, Davis, and Davis, in 2003. UTAUT is a theoretical model designed to explain and predict the factors influencing users' acceptance and use of technology. UTAUT builds on several existing theories, including the Technology Acceptance Model (TAM), the Theory of Reasoned Action (TRA), and the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB). UTAUT integrates these theories and adds four fundamental constructs: performance expectancy, effort expectancy, social influence, and facilitating conditions [73]. Combining these constructs, UTAUT provides a comprehensive framework for understanding technology acceptance and use [74]. The model has been widely used in research and practice to guide the design and implementation of technology interventions. The UTAUT model can be applied to understand users' acceptance and use of AI tools [75]. In the case of AI tools, the constructs of UTAUT can be adapted to reflect the specific features and capabilities of AI technology [31,76]. UTAUT has already been used to study emerging AI tools, such as chatbots [77,78], virtual assistants [79], recommendation systems [80], and predictive analytics tools [81]. UTAUT has also applied to study the influence of AI technologies on early adopters [82,83]. When studying early adopters of AI technologies, the UTAUT model can be used to identify factors that influence early adoption, such as the perceived usefulness and ease of use of the technology and social influence. By understanding these factors, researchers can gain insights into what motivates early adopters to adopt new technologies and identify potential barriers to adoption [75].

3.1. Performance expectancy with ChatGPT

Performance expectancy is one of the key constructs in the UTAUT model, which is used to explain and predict individuals' technology acceptance behaviour. Performance expectancy refers to the degree to which an individual believes that using a particular technology will help them to perform their tasks more effectively or efficiently [73]. Prior studies on Chatbots suggest that performance expectancy is essential in predicting user acceptance and use of chatbots [6]. It can be influenced by several factors related to the chatbot's perceived usefulness, compatibility, and impact on job performance [84,85], task accomplishment, sense of accomplishment, and enhanced engagement [78]. In the context of ChatGPT, performance expectancy in UTAUT refers to the extent to which users believe that using ChatGPT will help them to perform their tasks more effectively and efficiently. According to UTAUT, the perception of performance expectancy can be influenced by several factors, including the perceived usefulness of ChatGPT, the user's expectations of ChatGPT's impact on their task performance, and the user's beliefs about the compatibility between ChatGPT and their current work practices.

3.2. Effort expectancy with ChatGPT

Effort expectancy refers to the perceived ease of using a particular technology [73]. According to UTAUT, effort expectancy is influenced by several factors, including the individual's prior experience with technology, their perceived technical ability, the complexity of the technology, and the availability of resources and support for using the technology [86]. The greater the perceived ease of technology, the more likely an individual is to adopt and use it [87]. However, the prior studies on Chatbots paint a conflicting picture of the effort expectancy of Chatbot adoption. Some of the prior scholarships suggest that the effort expectancy of Chatbots was found to be having a negative association with chatbot usage intention [88,89]. Contrary to this, in a recent study on the adoption and usage of chatbots in the banking sector [78], found that effort expectancy played a crucial role in chatbot adoption. In the case of ChatGPT, a large language model trained with a high level of effort expectancy would likely positively influence its adoption and usage. If users perceive ChatGPT as easy to use, they are more likely to adopt and integrate it into their daily routines. This could lead to increased usage and greater value from the technology. Therefore, understanding the effort expectancy should be a priority for those seeking to promote the adoption and usage of ChatGPT.

3.3. Social influence with ChatGPT

Social influence refers to how an individual perceives that significant others, such as friends, family members, or colleagues, believe they should use a particular technology [73]. Prior studies on chatbots suggest that social influence can affect the user's intention to use a chatbot in several ways. For example, positive social influence can increase the user's perception of the usefulness and ease of use of chatbots and reduce the perceived risks and barriers to adoption [78,90]. On the other hand, negative social influence can create doubts and concerns about the effectiveness and reliability of digital technologies and reinforce the user's resistance to change [91]. Social influence can come from various sources, such as friends, family, colleagues, experts, influencers, and online reviews [92]. Positive social influence can increase the user's perception of the usefulness and ease of use of ChatGPT, reduce the perceived risks and barriers to adoption, and enhance the user's confidence in their ability to use the technology effectively. On the other hand, negative social influence can create doubts and concerns about the reliability, accuracy, and ethics of ChatGPT and reinforce the user's resistance to change. Negative social influence can also stem from concerns about the potential misuse of ChatGPT, such as the spread of misinformation, biased content, or harmful recommendations. The wide acceptance and increased usage of ChatGPT globally immediately after its official launch [12,13] indicate that social influence is believed to influence its adoption positively.

3.4. Facilitating conditions with ChatGPT

Facilitating Conditions, the fourth factor in the UTAUT model refers to the degree to which individuals perceive that an organisational and technical infrastructure exists to support the use of technology [73]. It encompasses the resources, support, and technical infrastructure available to the user, such as hardware, software, technical support, and training [93]. Previous studies on chatbots have shown that facilitating conditions play a significant role in their adoption and usage [78]; [90]. In the case of ChatGPT, an AI language model, facilitating conditions could include access to a computer or mobile device with internet connectivity, a reliable and stable internet connection, and technical support to troubleshoot any issues that users may encounter. These facilitating conditions can significantly impact the adoption of ChatGPT. For instance, if users do not have access to the necessary technological resources or face technical difficulties, they may be less likely to adopt or continue using ChatGPT. On the other hand, if users can access the necessary technological resources and support, they may be more inclined to adopt ChatGPT and integrate it into their daily routines.

3.5. UTAUT moderating factors with ChatGPT

The UTAUT model includes four moderators influencing the relationship between the model's key constructs and users' behaviour: Gender, Age, Experience and Voluntariness [73]. Based on prior investigations, the UTAUT model suggests that these four moderators should be considered when predicting and explaining users' technology acceptance and usage behaviour [94]. In a prior study on robo-advisors' usage in the banking sector [95], observed that age and gender positively influence the perceived usefulness and user intention to use them. Mogaji et al., 2[78]022 in their study on chatbot adoption in the banking sector, found that age and experience moderate their usage. All of these moderators can influence the adoption of ChatGPT usage as well. For example, older individuals may find ChatGPT more difficult or less valuable, while individuals with more technology experience may find ChatGPT more user-friendly and helpful. Similarly, suppose users perceive a high risk associated with using ChatGPT. In that case, they may be less likely to adopt it, while users who trust the ChatGPT technology and the entity behind it may be more likely to adopt it. Therefore, when considering the adoption and usage of ChatGPT, it is essential to consider the influence of these moderators and how they may impact the acceptance and use of the technology. By addressing the concerns of potential users and building trust in the technology, chatbot developers can increase the likelihood of adoption and usage of ChatGPT.

3.6. Usage of external factors in the UTAUT model

UTAUT model offers the flexibility to be extended with other constructs to provide a more comprehensive understanding of user behaviour towards technology adoption and use [96]. The UTAUT model itself was developed based on a review of existing technology acceptance models, and its creators acknowledged that it is not an exhaustive model and that other factors may also impact technology acceptance [29]. Researchers have integrated various external constructs, such as trust [97], perceived security and privacy [98], perceived enjoyment [99], and system interactivity [100], to increase the robustness of the model. By incorporating additional constructs, the UTAUT model can provide a more comprehensive and nuanced understanding of user behaviour towards technology adoption and use [101]. In the current study, we consider extending the model with additional constructs based on the themes that emerge from the interviews.

4. Methodology

4.1. Semi-structured interviews

This study adopts qualitative interpretative research methods to understand how users have adopted ChatGPT. This research approach was used to gain in-depth insights and an understanding of users' experiences with ChatGPT. The goal of using qualitative interpretative research in this study is to understand the use of ChatGPT as an AI technology from users' perspectives. Given that qualitative interpretative research provides scope for using questions based on a theoretical framework that can be changed to get the most pertinent information, the researchers can elicit information from the participants using this method. The interview method, one of the qualitative methods, was adopted for the study. Interviews are believed to provide a ‘deeper’ understanding of social phenomena [102]. A qualitative research interview covers both a ‘factual’ and a ‘meaning’ level. However, it is usually more difficult to interview on a ‘meaning’ level[103]. During the interviews, the researcher was careful to draw inferences from the participants' responses at the factual level and the implied meaning by probing with follow-up questions. Further, the interviewer noted the non-verbal cues like pauses and specific expressions that the researcher interpreted in the analysis.

4.2. Sample recruitment

Semi-structured interviews with ChatGPT users in India were employed to collect the data. The decision to select samples from India for the study on ChatGPT's acceptance and usage is motivated by the country's diverse user base [104], sizeable tech-savvy population [105], high internet and smartphone penetration [106], and rapidly expanding AI market [107]. India's cultural diversity offers the opportunity to explore cross-cultural factors influencing ChatGPT's adoption. Understanding early adopters' sentiments in this emerging market can provide insights into potential challenges and opportunities, while the findings may have broader implications for AI adoption trends globally. By focusing on India, the study aims to capture a comprehensive understanding of user perceptions and experiences with ChatGPT, benefiting both the Indian AI ecosystem and the broader research on AI technology acceptance and usage.

Non-probability sampling and non-random selection based on convenience were used to collect the data. Flyers sent on various social media channels were used to find possible participants. We chose the samples based on the requirement that they should have been actively using ChatGPT for at least a month because that is the focus of the current study's interest in the user experience of ChatGPT.

The last date for enrolment was mentioned in the flyer. The initial, last date mentioned was one week from the date of the posting of the flyer. The response to the flyer regarding enrolment was good. There were over 50 respondents who expressed interest in participating in the Study.

All procedures performed in this research involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the 1975 Helsinki Declaration. Participants were invited to join an online meeting hosted on Google Meet. The respondents were informed of the objective and purpose of the study. Before conducting the interviews, the respondents’ verbal consent was additionally obtained. Most respondents volunteered for the study, and neither financial compensation nor gifts were given to participants. Of the first 50 persons that responded to our message, 38 expressed consent for the interview. Further, out of 38 Users, only 36 agreed to participate in the interview. In the end, 32 respondents persisted and participated in the interview. The response rate thus stands at 64 %. The participants signed up for a mutually agreeable interview date and time, which was carried out in January 2023.

Basic demographic information was collected, such as gender, age, and profession of the participants. The same is indicated in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographic details of the participants.

| Participant Code | Gender | Age | Education | Employment |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PC1F | Female | 18–25 | Graduation | Student |

| PC2F | Female | 18–25 | Graduation | Student |

| PC3F | Female | 18–25 | Graduation | Student |

| PC4F | Female | 18–25 | Graduation | Student |

| PC5F | Female | 18–25 | Graduation | Student |

| PC6F | Female | 18–25 | Graduation | Student |

| PC7F | Female | 18–25 | Graduation | Student |

| PC8F | Female | 18–25 | Graduation | Student |

| PC9F | Female | 18–25 | Post Graduate | Self-Employed |

| PC10F | Female | 18–25 | Graduation | Self-Employed |

| PC11F | Female | 26–35 | Post Graduate | Self-Employed |

| PC12F | Female | 26–35 | Graduation | Self-Employed |

| PC13F | Female | 26–35 | PhD | Employed |

| PC14F | Female | 26–35 | Post Graduate | Employed |

| PC15 M | Male | 18–25 | Graduation | Student |

| PC16 M | Male | 18–25 | Graduation | Student |

| PC17 M | Male | 18–25 | Graduation | Self-Employed |

| PC18 M | Male | 18–25 | Graduation | Self-Employed |

| PC19 M | Male | 18–24 | Graduation | Self-Employed |

| PC20 M | Male | 18–24 | Graduation | Employed |

| PC21 M | Male | 18–24 | Graduation | Employed |

| PC22 M | Male | 18–24 | Graduation | Student |

| PC23 M | Male | 18–24 | Post Graduate | Student |

| PC24 M | Male | 18–24 | Post Graduate | Employed |

| PC25 M | Male | 18–24 | Post Graduate | Employed |

| PC26 M | Male | 18–24 | Post Graduate | Employed |

| PC27 M | Male | 26–35 | Post Graduate | Self-Employed |

| PC28 M | Male | 26–35 | PhD | Employed |

| PC29 M | Male | 26–35 | PhD | Employed |

| PC30 M | Male | 26–35 | Post Graduate | Employed |

| PC31 M | Male | >36 | Post Graduate | Employed |

| PC32 M | Male | >36 | Graduation | Employed |

Participants included females (n = 14, 43.75 %) and males (n = 18, 56.25 %). The age profile of the respondents was categorised as young adults in the age group of 18–25 years, middle-aged adults in the age group of 26–35 years, and older adults above the age of 36 years. 68.75 % (n = 22) of respondents were young adults, while n = 08, 25 % were middle-aged adults, and 6.25 % (n = 02) were older adults. Regarding educational qualification and employment status, n = 11 (34.37 %) respondents were students pursuing graduation, and n = 1(3.12 %) were students pursuing post-graduation. n = 5 (15.62 %) respondents had a graduate degree and were self-employed, while n = 3 (9.37 %) having a graduate degree were employed. n = 5 (15.62 %) respondents who had completed post-graduate degrees were employed, while n = 3 (9.37 %) were self-employed. n = 3 (9.37 %) of the respondent had a PhD degree and were employed. Participants were assured of anonymity. The interview was conducted on the telephone. Respondents were asked questions in line with the study's objectives. The interview questions were comprehensively designed to cover various dimensions in line with the study's objectives. The questions started with seeking demographic profiling of the respondents and moved on to specifics of patterns of usage of ChatGPT. The later stage of the interview contained questions specific to respondents' experience of using ChatGPT – their perceived satisfaction with the application, performance, relatability to their work (professional or academic), user interface, social influence, privacy, and safety concerns. The interviews lasted between 30 and 50 min and were transcribed for further analysis.

4.3. Data analysis

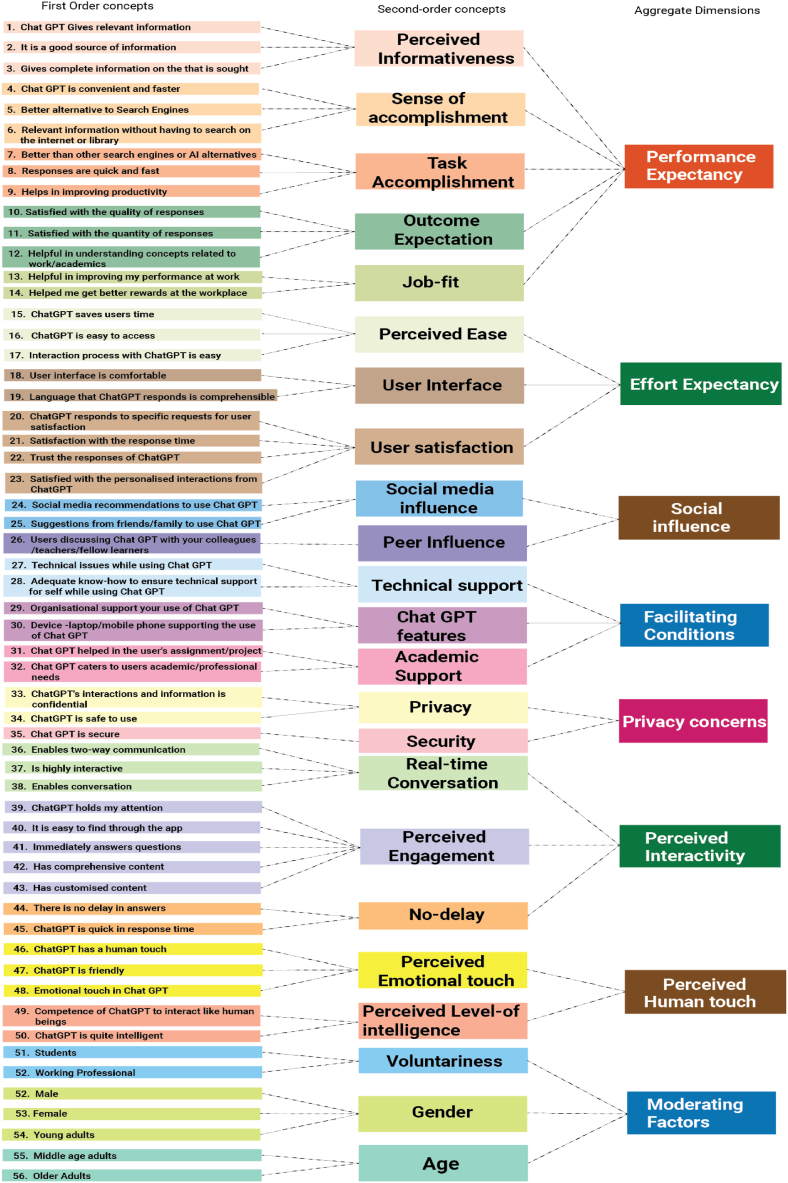

[108] six-phase approach to thematic analysis is widely used for analysing qualitative data. This provides systematic and rigorous methods for analysing qualitative data and generating themes that capture the essence of the data. The six phases include – familiarisation with the data, generating initial codes, searching for themes, reviewing themes, defining and naming themes and finally, writing up. In this study, we transcribed all the interviews manually to ensure precision in capturing the responses' facts and meaning. Further, the transcripts were imported to NVivo software, and initial codes were generated as part of the second phase. As the interviews were based on the UTAUT model, the data was coded keeping the theory in mind. In NVivo, the direct determinants of the modified UTAUT model, i.e., performance expectancy, effort expectancy, social influence, facilitating conditions, perceived Interactivity, human touch, and privacy concerns, were treated as parent nodes. Perceived interactivity and human touch were the parent nodes identified by the researchers based on the data gathered. These two parent nodes are an extension of the aggregate dimensions of the UTAUT model. In the third phase, the corresponding subthemes were located; for example, child nodes like perceived informativeness, sense of accomplishment, task accomplishment, outcome expectation, and job fit were related to Performance Expectancy. Fourth, overlapping items were reviewed and refined for better fit and clarity. Fifth, the refined child nodes were renamed in tune with the theoretical framework of the UTAUT model. Finally, the observations and findings were used to prepare the report on users’ experience with ChatGPT.

5. Results

Table 2 provides a summary of the results of the study. The table reflects first-order and second-order concepts in alignment with the UTAUT theory. As a first-order concept, performance expectancy has informativeness, sense of accomplishment, task accomplishment, outcome expectation, and job fit as second-order concepts. Effort Expectancy covers perceived ease, user interface, and user satisfaction. Social media influence and professional influence as second-order concepts integrated into the first-order concept of social influence. Technical features, academic support, and dependency mapping to facilitate conditions. Privacy and security are captured under privacy concerns. Interactivity emerged as an aggregate dimension that covers real-time conversation, perceived engagement, and no delay. Age, gender, experience and voluntariness are grouped under moderating conditions. The themes generated through NVivo software were conducive to expanding the scope of the UTAUT model [96] to include additional themes, Human touch and perceived interactivity (See Appendix-I). The researchers integrated these themes into the scope of the study since these themes offer a further understanding of the complex interplay of factors that influence an individual's decision to adopt and use technology under various conditions. Emotional touch and level of intelligence are analysed under the human touch.

Table 2.

Table of summary of key themes.

| First Order concepts | N = 32 n | Second-order concepts | Aggregate Dimensions | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Chat GPT Gives relevant information | 31 | Perceived Informativeness | Performance Expectancy |

| 2 | It is a good source of information | 30 | ||

| 3 | Gives complete information on the that is sought | 28 | ||

| 4 | Chat GPT is convenient and faster | 29 | Sense of accomplishment | |

| 5 | A better Alternative to Search Engines | 30 | ||

| 6 | Relevant information without having to search on the internet or library | 27 | ||

| 7 | Better than other search engines or AI alternatives | 28 | Task Accomplishment | |

| 8 | Responses are quick and fast | 27 | ||

| 9 | Helps in improving productivity | 26 | ||

| 10 | Satisfied with the quality of the responses | 26 | Outcome Expectation | |

| 11 | Satisfied with the quantity of responses | 22 | ||

| 12 | Helpful in understanding concepts related to work/academics | 28 | ||

| 13 | Helpful in improving my performance at work | 27 | Job-fit | |

| 14 | It helped me get better rewards at the workplace | 26 | ||

| 15 | ChatGPT saves users time | 30 | Perceived Ease | Effort Expectancy |

| 16 | ChatGPT is easy to access | 30 | ||

| 17 | The interaction process with ChatGPT is easy | 31 | ||

| 18 | The user interface is comfortable | 32 | User Interface | |

| 19 | The language that ChatGPT responds to is comprehensible | 32 | ||

| 20 | ChatGPT responds to specific requests for user satisfaction | 28 | User satisfaction | |

| 21 | Satisfaction with the response time | 28 | ||

| 22 | Trust the responses of ChatGPT | 26 | ||

| 23 | Satisfied with the personalised interactions from ChatGPT | 28 | ||

| 24 | Social media recommendations to use Chat GPT | 30 | Social media influence | Social influence |

| 25 | Suggestions from friends/family to use Chat GPT | 28 | ||

| 26 | Users discussing Chat GPT with your colleagues/teachers/fellow learners | 29 | Peer Influence | |

| 27 | Technical issues while using Chat GPT | 15 | Technical support | Facilitating Conditions |

| 28 | Adequate know-how to ensure technical support for self while using Chat GPT | 30 | ||

| 29 | Organisational support your use of Chat GPT | 10 | Chat GPT features | |

| 30 | Device -laptop/mobile phone supporting the use of Chat GPT | 32 | ||

| 31 | Chat GPT helped in the user's assignment/project | 30 | Academic Support | |

| 32 | Chat GPT caters to users' academic/professional needs | 29 | ||

| 37 | ChatGPT's interactions and information is confidential | 10 | Privacy | Privacy concerns |

| 38 | ChatGPT is safe to use | 25 | ||

| 39 | Chat GPT is secure | 26 | Security | |

| 40 | Enables two-way communication | 26 | Real-time Conversation | Perceived Interactivity |

| 41 | Is highly interactive | 28 | ||

| 42 | Enables conversation | 30 | ||

| 43 | ChatGPT holds my attention | 30 | Perceived Engagement | |

| 44 | It is easy to find through the app | 32 | ||

| 45 | Immediately answers questions | 30 | ||

| 46 | Has comprehensive content | 20 | ||

| 47 | Has customised content | 30 | ||

| 48 | There is no delay in answers | 28 | No-delay | |

| 49 | ChatGPT is quick in response time | 28 | ||

| 50 | ChatGPT has a human touch | 25 | Perceived Emotional touch | Perceived Human touch |

| 51 | ChatGPT is friendly | 24 | ||

| 52 | Emotional touch in Chat GPT | 23 | ||

| 53 | Competence of ChatGPT to interact like human beings | 24 | Perceived Level-of intelligence | |

| 54 | ChatGPT is quite intelligent | 31 | ||

| 55 | Students | 20 | Voluntariness | Moderating Factors |

| 56 | Working Professional | 12 | ||

| 57 | Male | 18 | Gender | |

| 58 | Female | 14 | ||

| 59 | Young adults | 22 | Age | |

| 60 | Middle age adults | 8 | ||

| 61 | Older Adults | 2 |

5.1. Performance expectancy

Among the themes derived from the data, performance expectancy has been a significant aggregate dimension. This is reiterated in the 5 s-order concepts grouped under performance expectancy. During the interviews, most respondents indicated that they perceived ChatGPT as informative. They felt that ChatGPT gives them the relevant and complete information they seek.

I have been using ChatGPT to understand concepts I find difficult to understand in class. It explains the concepts in simple terms and provides the required information. [PC6F]

ChatGPT is handy when working on assignments if I need any quick reference. I do not have to skim through search engine results. ChatGPT gives me all the required information that I want. [PC16M]

Further, respondents have also iterated ChatGPT as a good source of information. ‘I tried using ChatGPT to experiment with the information that it could provide. I am fascinated with how it can present so much information.

While respondents have acknowledged ChatGPT as a good source of information, they also stated how this information is time-bound. ChatGPT does not have access to real-time information as an AI language model. Its responses are generated based on its training data which goes up until 2021. Considering the fast-paced world that we live in, information is dynamic. If the source of information that we rely on does not have the latest updates, it might impede dependence.

As a student of BTech, we have to be updated with technology. I have realised that ChatGPT has its limitations. It does not help with the latest updates because of the limitation of its pre-dated data. So, I use ChatGPT as one of my sources, not the only source. [PC22M]

Respondents have also recorded instances where ChatGPT has given out misinformation.

I used ChatGPT for searching data for my work related to the literature review. I was appalled to see that ChatGPT gave the wrong response. It referenced a research paper I could not find anywhere on digital sites. When probed further, ChatGPT apologised and admitted that it could have made a mistake. We need to be alert and verify facts given by ChatGPT before taking it forward. [PC23M]

Participants acknowledged that ChatGPT helps them accomplish tasks related to their academic/professional work. Most have opined that ChatGPT is better than other search engines and is a decent AI alternative. Also, they feel that the responses in ChatGPT are quick and fast. They have admitted that ChatGPT helps in improving their productivity. However, the respondents have also accepted that ChatGPT has made them lazy.

I used to spend hours searching the internet for information and data for my project. From the deluge of information, I had to identify relevant data, understand, and then use it for my assignment. Now, I have to ask specific questions to ChatGPT, which does all the searching and fine-tuning. I have to understand and use it. [PC3F]

It has saved me a lot of time and effort. Yes. It might make us lazy but remember, we still have to ask the right questions to get the correct data. [PC16M]

Respondents feel a sense of accomplishment while using ChatGPT. This has been established in their responses, where they have been vocal that ChatGPT being convenient and faster has helped them accomplish their tasks without searching the internet or library. They have stated that it is a better alternative to search engines like Google.

What used to take me 2 hours, I can complete the same task in less than 30 minutes. As a content manager, I find it very convenient to use ChatGPT to help me with captions, content for social media, generic emails, etc. It has eased the time taken to do certain routine work. [PC11F]

However, apprehensions about ethical concerns about using ChatGPT also emerged during the interview.

‘Though I use ChatGPT for quick reference, I always verify before sharing the final document with other sources [PC14F]’. The interviewer observed the long-drawn pauses that PC14F took while answering whether ChatGPT is a better alternative to search engines.

Participants acknowledged that the quality of responses from ChatGPT draws them to it more than the quantity. PC29 M remarks, ‘There is a flood of information on digital media. It is not the amount of information, but what ChatGPT shares is extremely relevant and required. This quality factor is what draws me to ChatGPT’. Most respondents have opined that ChatGPT has met their outcome expectations.

Outcome Expectancy is an essential construct in UTAUT as it is crucial in predicting user behaviour and intentions to adopt new technologies. It reflects the user's belief that using the technology will lead to specific outcomes influencing their decision to accept or reject it. In this case, respondents believe that ChatGPT supports their purpose of using it, which drives them towards acceptance of the same. Further, if the same technology can aid users in improving their performance at work and getting better rewards and recognition, the degree of acceptance is higher. This is reiterated in the responses shared by users who are employed. ‘I use ChatGPT to compose my reports. When I get stuck while drafting, I quickly check with ChatGPT, giving me several alternative ways of drafting my ideas in no time. I am satisfied with how ChatGPT has helped me in my professional work.’ PC32 M.

5.2. Effort expectancy

Effort expectancy, which corresponds to the participants’ perceptions of effort in this study, is another vital element that emerged from the interviews. Using ChatGPT to complete their academic and professional obligations was seen as simple.

The participants in the study expressed their appreciation for the ease of access and time-saving benefits of using ChatGPT. Participants who had previous experience using technology to support their academic and professional tasks shared their past experiences and noted that their appreciation of ChatGPT was relative to their experience with other technologies. Some participants mentioned using multiple apps for different purposes, such as grammar checking, data analysis, and understanding. However, they found ChatGPT a one-stop solution, providing immediate and quick responses to all their needs. ‘I used a few specific apps to check my grammar, another for data, and another for understanding and analysing. ChatGPT is like a one-stop solution. I get immediate and quick responses to whatever I need’ [PC18 M].

This underscores the participants’ positive impression of ChatGPT as a versatile and efficient tool that streamlines their work processes.

The user interface of ChatGPT was well-received by the participants, who found it comfortable and easy to use. The language used by ChatGPT was also comprehensible, which contributed to the positive feedback shared by respondents on their experience with the user interface. Furthermore, the response time and personalised responses based on specific needs were noted as contributing factors to user satisfaction.

However, a few respondents expressed a lack of trust in ChatGPT. This indicates that while the technology is appreciated for its ease of use and personalised responses, there may be room for improvement in addressing potential concerns around trustworthiness. It is important to note that this feedback represents an opportunity for ChatGPT developers to address any perceived limitations and advance the technology.

‘It is swift in responding, but I am sceptical of some responses, precise data. However, this is a work-in-progress technology. I am confident that all the loopholes in this application will be plugged in due time”, remarks PC30M.

The interviews have provided insight into how favourably ChatGPT is viewed in terms of expected effort. The participants in the study found the technology easy to use and appreciated its ability to save time and streamline their work processes. They also noted that ChatGPT provides immediate and quick responses to their needs, making it a one-stop solution for their academic and professional tasks. Additionally, the user interface of ChatGPT was well-received, and the language used by the technology was comprehensible, contributing to the positive feedback shared by respondents on their experience with the user interface. Furthermore, the response time and personalised responses based on specific needs were noted as contributing factors to user satisfaction. While a few respondents expressed a lack of trust in ChatGPT, this was not related to effort expectancy but rather to concerns about the accuracy and trustworthiness of the technology. Overall, the interviews suggest that ChatGPT has been perceived as having reasonable effort expectancy, with participants finding it easy to use and time-saving.

5.3. Social influence

Social influence plays a vital role in early technology adoption (Venkatesh et al., 2003; [109,110]. When a new technology is introduced, people often look to their social networks to decide whether or not to adopt it. Social influence through social media and peers has been recorded in the responses gathered in the interviews.

I first learned about ChatGPT through social media. There were so many posts on this technology. My friends on social media were sharing their experiences of trying ChatGPT. I was intrigued and tried it. Moreover, I have influenced my other friends to use it. [PC8F]

Peer pressure is another method that social influence impacts how technology is adopted. People may feel pressured to use new technology if they observe their peers doing so to fit in and avoid feeling left out.

‘During the class, my teacher remarked on my friend's work, saying how his assignment could be produced by ChatGPT also and that it was nothing original or unique. This casual comment triggered my interest to check out ChatGPT. I have been using it since then. [PC22 M]

Social media and online networks can amplify social influence. People may be more willing to use new technology if they observe others embracing it on social media platforms. Likewise, peer influence also has been recorded to have contributed to respondents’ usage of ChatGPT.

5.4. Facilitating conditions

Technical support is a crucial enabling factor that can promote the adoption of new technology by giving users the tools and assistance they need to use and troubleshoot the technology effectively. A considerable number of respondents did express that they have faced technical issues while using the application. ‘The application hangs at times. This could be because of the heavy traffic of users using the application simultaneously. Since it is in the initial stages, I am sure this will be addressed. [PC15 M]

However, most respondents shared that they had adequate know-how to ensure technical support for themselves while using Chat GPT. ‘It is a straightforward application. Even a 5-year-old child can use it with ease. There is no technical support that is required. Most of the technical issues are related to server issues which need fixing at the developers’ end’. [PC20 M]

Further, all the respondents admitted that ChatGPT is compatible with all devices, facilitating conducive conditions for usage. Several respondents stated that they use the app on their mobile phones, most on their laptops, some on their tablets, and a few on multiple devices. This augments the usage pattern of the application.

The only deterring facilitating condition was limited support from the organisations to use ChatGPT. ‘My college has blocked ChatGPT on college devices/wifi. We have been informed not to use ChatGPT while turning in our assignments. Nevertheless, I use it for my reference from my home. [PC3F]

Successful adoption of technology is influenced by external conditions and elements that either facilitate or restrict the use of technology, in addition to the user's intention and conduct. Technical assistance that is easily accessible and efficient can assist in lowering adoption barriers by giving users the tools and direction they need to navigate any difficulties they may encounter successfully.

The researchers have considered respondents' opinions on ChatGPT catering to the users' academic and professional needs as one of the facilitating conditions. After all, continuous use and adoption of the technology may rise because of helping to boost user confidence and enhance the user experience. Most respondents have been using ChatGPT either for their academic or professional work. Respondents have admitted to using ChatGPT for -; assignments', ‘projects’ ‘reports,’ presentations' ‘drafts’ ‘understanding concepts while preparing for tests/exams’. The sense of purpose to use the application is no doubt a facilitating condition for adoption, especially in the early stages of the technology.

5.5. Human touch

ChatGPT is an AI language model that lacks a human touch because it does not have feelings, unique experiences, or subjective viewpoints like a person might. However, ChatGPT is made to simulate human-like dialogue and answer naturally and interestingly, which can be perceived as having a human touch. Perceived emotional touch was a recurrent sub-themes that emerged during the interviews. Some respondents have shared that they appreciated that ‘ChatGPT responds like a person, especially when it says sorry when it does not know the answer.’ [PC18 M]

‘It understands the context and meaning of the user’s input and generates appropriate and relevant responses to the conversation. Despite being algorithm-generated responses, they appear to be friendly, informative, and helpful. It has a human touch to this extent.’ [PC28M]

However, there is a consensus that as an AI, ChatGPT has limitations to responding like human beings.

Yes. ChatGPT is intelligent, but it is still a machine. Its intelligence is restricted to the data that it is trained on. It is still in the development phase. It is yet to update itself on the data post-2021. [PC1F]

Its capacity to reply appropriately to various topics under different situations and produce coherent and appropriate responses suited to our input is evidence of its intelligence. [PC29 M]

Though respondents have expressed their understanding of ChatGPT's limitations to responding like human beings, they have a consensus that, as an AI, ChatGPT's level of intelligence is commendable.

5.6. Perceived interactivity

One of the most prominent themes from the interviews is perceived interactivity. Chat GPT, an AI-driven natural language processing technology, is designed to simulate natural language conversations. The algorithms are codes to understand user inputs and generate relevant responses. The outcome is perceived Real-time conversation.

ChatGPT is highly interactive. The process of asking questions and getting responses makes enable two-way communication. [PC9F]. Most of the respondents have agreed that ChatGPT enables conversation with the users.

Further, respondents have admitted that ChatGPT holds up their attention by immediately answering all the questions. You have to be highly specific about what you want with search engines. However, ChatGPT tries to interpret the context even if we do not properly frame the question/query. It holds my attention. [PC7F]

Though there is positive feedback on certain areas of engagement, most respondents have acknowledged that the content that ChatGPT provides, in terms of comprehensive content, is limited. I use ChatGPT for quick references. It is good to this extent. If you are looking for depth, you must rely on good-old methods. It is no more than a ‘guide’ book. PC13F.

Remarking on how ChatGPT customises the content according to the user's requirement, PC11F, a teacher by profession, remarked, ‘I was amused to see how ChatGPT reframes content for the same question to cater to different levels of understanding. I asked ChatGPT to explain the Law of demand for a slow, average, and advanced learner. I was impressed by how it generated different responses for all three learner categories. It is no wonder it draws our attention. Respondents also reiterated how the quick response time adds to the overall interactivity.

5.7. Privacy concerns

The researchers have included privacy concerns as an additional aggregate dimension based on secondary data gathered during the literature review. Interview questions encouraged participants to comment on the privacy and security issues related to ChatGPT. While most respondents admitted to being aware that their interactions and information with ChatGPT are not confidential, they found it safe and secure.

I know that whenever I use technology, especially AI, there is no question of privacy. Comfort and convenience come at a cost. PC30M answered in rhetoric. He continues by adding, ‘the onus is on us as to how much we share and reveal’.

I am worried about the possibility of intentional or unintentional data exposure. I am cautious in my usage. There is always a risk attached to such technology.

The interview responses related to privacy and safety pointed out how users must exercise caution about sharing personal information and be aware of reporting suspicious or inappropriate behaviour. However, participants also specified that ChatGPT is safer and less prone to cyber-related crimes or malicious attacks, unlike social media. Responding to the issue, PC27 M remarks, ‘There is a high degree of privacy with ChatGPT because the conversation is between you and ChatGPT. It is not made public. Yes, there is fear of data exposure because ChatGPT generates responses by analysing users. It may have privacy concerns but fewer safety concerns.’

5.8. Moderating conditions

The moderating elements in UTAUT2 emphasise the significance of considering user demographics and context when researching user behaviour and technological adoption. In this study, the researchers have identified gender, age, and voluntariness as the moderating factors. Respondents identified as Male or female; no response was recorded under the ‘other’ gender category.

The data analysis does not point at gender having any moderating role in using ChatGPT. Both male and female respondents have shared similar experiences with ChatGPT. However, voluntariness and age, including education and employment, did reveal some influence on technology usage.

Sense of accomplishment, outcome expectation, perceived ease, social media influence, privacy concerns, and perceived interactions were factors that seemed to have been moderated by age and experience. Younger adults pursuing higher education were less concerned about privacy issues. They also appeared to have a higher sense of accomplishment. They reported greater ease of using ChatGPT. Further, most were influenced by social media. Younger participants seem to indicate that they are likely to continue using ChatGPT. Not much of a difference was established between the younger adults and the middle-aged adults.

I like exploring new technologies. I was using many other AI-based applications. I keep track of the reviews on social media about the latest applications. That is how I learnt about ChatGPT and began using it. [PC5F]

On the contrary, older adults exercise caution and restraint while using ChatGPT. They revealed that performance expectancy was the primary factor driving them to use the technology. They did raise concerns over safety and privacy.

PC28 M, a working professional in the education sector with a doctoral degree, remarked, ‘I have used technology extensively. However, I am cautious about what I use and how. ChatGPT is great in terms of user interface but has limitations. It is our responsibility to use the app within an ethical framework.’

6. Discussion

The study results indicate that aggregate dimensions of performance expectancy, effort expectancy, social influence, facilitating conditions and privacy concerns predominantly influence the usage of ChatGPT. This finding aligns with the prior qualitative chatbot study[78]. All five second-order concepts, perceived informativeness, sense of accomplishment, task accomplishment, outcome expectation, and job fit related to performance expectancy, have been established in the data. This finding suggests that by addressing and optimising these factors, organisations can help promote the adoption and use of ChatGPT, leading to improved job performance and outcomes.

Further, perceived interactivity, an extension of UTAUT theory, is also identified to be a dominant factor. Perceived interactivity refers to the degree to which a user perceives a system as responsive, flexible, and capable of supporting a two-way communication process [111]. Prior scholarships [112,113] suggested that interactivity is essential when designing and promoting chatbots to potential users. By providing a high level of interactivity and responsiveness, chatbots like ChatGPT are more likely to be perceived as valuable and enjoyable to use, which can increase users' intention to adopt and use the technology.

The researchers have identified perceived human touch as another extended factor, but the correlation between this factor and ChatGPT usage is limited. Perceived human touch refers to the social presence and emotional connection that people experience when interacting with others, including physical touch, eye contact, and vocal cues [114,115]. While some studies suggest incorporating human-like conversational features, such as humour and empathy, can increase users' engagement with conversational agents [116,117], the correlation between perceived human touch and ChatGPT usage is limited. One probable reason for this is that ChatGPT is a text-based conversational agent that relies solely on written language to communicate with users, which can limit the perceived human touch compared to face-to-face interactions or even voice-based conversational agents. ChatGPT is not designed to simulate physical touch or other nonverbal cues often associated with the perceived human touch.

The data highlight that most respondents found ChatGPT informative, providing relevant and comprehensive information. Participants also reported that ChatGPT helped them complete tasks related to their academic or professional work and that it outperformed other search engines as a reliable AI alternative. The findings that most respondents found ChatGPT informative and helpful in completing tasks related to their academic or professional work are consistent with previous research on the effectiveness of language models in information retrieval and natural language processing. Prior studies [118,119] have found that incorporating query expansion techniques, which involve expanding the original search query to include related terms, could significantly improve the effectiveness of information retrieval systems. Similarly, ChatGPT's ability to understand natural language queries and provide relevant responses may be crucial to its perceived informativeness and usefulness. Other research has also demonstrated the potential benefits of using language models like ChatGPT in information retrieval and natural language processing tasks. For example, a study by Ref. [120] found that the BERT language model significantly outperformed previous state-of-the-art models in various natural language processing tasks, including question-answering and text classification. ChatGPT outperforming other search engines as a reliable AI alternative may be due to the model's ability to generate more contextually relevant responses and its flexibility in understanding and responding to natural language queries. These advantages may make ChatGPT particularly well-suited for tasks requiring high precision and accuracy, such as academic or professional research.

The respondents appreciated the speed of the responses from ChatGPT, which they felt helped them to enhance their productivity. The appreciation of the speed and quality of responses from ChatGPT aligns with the concept of "just-in-time" learning [121], where individuals seek information as needed to complete a task or solve a problem in real-time. This approach allows for greater efficiency and productivity, as users do not have to search for information or wait for a response.

Quality of responses, rather than quantity, was cited as a critical factor that attracted users to ChatGPT. As a result, users felt that ChatGPT supported their intended use, leading to higher acceptance of the technology. Research has also shown that the quality of information is often prioritised over the quantity of information provided. A study on online health information seeking found that users preferred concise and accurate information rather than large amounts of information that may not be relevant to their needs [122]. This is in line with the findings of the respondents who valued the quality of responses from ChatGPT. Furthermore, if ChatGPT could assist users in improving their work performance and achieving better rewards and recognition, this could further increase its acceptance.

Another important factor that emerged was the participants' expectations of effort or perceptions of effort. The interviews revealed that ChatGPT aided in meeting academic and professional commitments. Participants who had previous experience using technology to support their work shared their past experiences and compared ChatGPT to other technologies. Participants cited user satisfaction as they are influenced by its response time and customised responses based on particular demands. Contrary to prior literature on AI-enabled chatbots [88,89], the interviews provided insight into ChatGPT's positive perception of expected effort. Participants in the interview felt the technology was simple to use and valued its capacity to speed up and simplify their work processes.

On the social influence front, in line with the prior literature on chatbots [78,90], social media and peer influence have been recorded to have contributed to respondents’ usage of ChatGPT. The age and experience of the participants moderated this factor. While social media influenced younger participants, older participants went with peer influence as a critical driver to initiate using ChatGPT. This is in tune with the prior literature, which suggested that social media more influence youngsters than older users [123]. On the other hand, older users are more influenced by peer pressure than social media [124].

Contrary to prior studies on chatbots [125,126], privacy was not a significant concern regarding the usage of ChatGPT. While most respondents admitted to being aware that their interactions and information with ChatGPT are not confidential, they found it safe and secure. The lack of concern about privacy among the respondents in this study may be due to a combination of factors [127], including trust in the platform's security measures, a lower expectation of privacy when interacting with chatbots, and a prioritisation of the benefits of using ChatGPT over the potential privacy risks.

The primary data established that gender does not influence how ChatGPT is used. Respondents of both genders had comparable experiences with ChatGPT. This finding aligns with Mogaji et al. [78](2022), who found that gender did not influence the usage of chatbots. However, it did turn out that voluntariness and age, including jobs and education, had some bearing on how people used technology. Age and experience appear to have tempered the influence of elements like the sense of success, outcome anticipation, perceived easiness, social media influence, privacy concerns, and perceived interactivity. Venkatesh et al. (2003) found that experience with technology can reduce the influence of perceived ease of use and perceived usefulness on adopting new technologies. This suggests that experienced users are more likely to base their decisions about technology adoption on factors such as their goals and needs rather than on external factors such as social influence or ease of use. Furthermore, older and more experienced users may have a more nuanced understanding of the limitations and capabilities of ChatGPT, which can influence their perceptions of factors such as interactivity and privacy concerns. A study by Ref. [128] found that older adults were more likely to consider privacy concerns when evaluating the usefulness and appropriateness of health-related chatbots. In summary, age and experience can moderate the impact of various factors on the use of ChatGPT. Older and more experienced users are less likely to be influenced by factors such as the sense of success, outcome anticipation, perceived easiness, social media influence, privacy concerns, and perceived interactivity of ChatGPT. This may be due to their greater reliance on their judgement and experience, as well as their more nuanced understanding of the limitations and capabilities of the tool.

6.1. Theoretical implications

The findings of this study contribute to the literature on technology acceptance and adoption, particularly in the context of AI-powered chatbots. The study provides evidence of the factors influencing the usage of ChatGPT and how they relate to the UTAUT model. Specifically, the study found that performance expectancy, effort expectancy, social influence, facilitating conditions, and privacy concerns were the predominant factors influencing the usage of ChatGPT, consistent with the prior literature on chatbots [78]. Furthermore, the study identified perceived interactivity as another dominant factor in using ChatGPT, an extension of the UTAUT theory. This highlights the importance of designing AI-powered chatbots that provide a personalised and engaging user experience. Perceived human touch was identified as an extended factor, although its correlation with usage was limited, suggesting that users do not necessarily require human-like responses from chatbots.

The study's findings also contribute to the literature on the factors influencing performance expectancy, with 5 s-order concepts (perceived informativeness, sense of accomplishment, task accomplishment, outcome expectation, and job fit) identified in the data. This research suggests that ChatGPT provided users with relevant and comprehensive information, helped them to complete academic or professional tasks, and outperformed other search engines as a reliable AI alternative. It is also found that the speed and quality of responses, customised to the user's particular demands, were critical factors in attracting and retaining users, consistent with prior research [87,129]. Another contribution of the study is the identification of participants' expectations of effort or effort expectancy as an essential factor in technology acceptance. The study found that ChatGPT was perceived as simple, and users valued its capacity to speed up and simplify their work processes. This finding supports prior research that ease of use and perceived usefulness are essential factors in technology adoption [73].

The study also adds to the growing literature on social influence and technology acceptance, with social media and peer influence identified as drivers of ChatGPT usage. Current research found that social media influenced younger participants, while older participants were influenced by their peers. This finding suggests that age and experience may moderate the impact of social influence on technology adoption [74].

Finally, the finding that privacy concerns did not significantly impact the usage of ChatGPT represents a unique contribution to the existing literature on chatbots and AI technologies. Prior research has highlighted the importance of privacy concerns in adopting and using AI-based technologies, including chatbots [125,126]. However, the results of this study suggest that for ChatGPT, privacy concerns were not a significant barrier to adoption. This finding aligns with recent research on the privacy paradox, which suggests that individuals may be willing to trade off some level of privacy for the benefits of using innovative technologies [130,131]. In the case of ChatGPT, users may perceive the benefits of using the tool for information and task completion as outweighing the potential privacy risks. In conclusion, the current study contributes to the technology acceptance and adoption literature and has practical implications for designing and implementing AI-powered chatbots.

6.2. Practical implications of the study

The practical implications of this study suggest that technology developers should focus on enhancing the performance expectancy and effort expectancy of AI-powered chatbots such as ChatGPT. Emphasising prior literature [6,132], we recommend that developers ensure that the chatbots provide informative and high-quality responses to users while simplifying and speeding up their work processes. Additionally, developers should consider the perceived interactivity of the chatbots as a significant factor in user acceptance, as users appreciate the feeling of interacting with responsive and engaging technology [133].

When implementing AI-powered chatbots in various settings, policymakers should consider the social influence [78,90] factor. For instance, younger users may be more influenced by social media campaigns and advertising, while older users may rely on recommendations from their peers. By understanding the social influence factors, policymakers can tailor their implementation strategies to ensure maximum reach and adoption of the technology [78].

Furthermore, privacy concerns [125,126] emerged as a crucial factor in accepting AI-powered chatbots. Developers and policymakers must ensure that users' privacy is protected by adhering to ethical standards, such as ensuring the confidentiality and security of user information. Additionally, users should be made aware of the level of confidentiality and security that the chatbot offers, as this can help to build trust and encourage the adoption of the technology. By enhancing the performance and effort expectancy, perceived interactivity, social influence, and privacy concerns, AI-powered chatbots such as ChatGPT can be developed and implemented to maximise user acceptance and adoption.

7. Conclusions, limitations and future research directions

Despite being initially designed for quantitative research, the UTAUT model was utilised in this qualitative study to provide a more comprehensive insight into how users interact and engage with ChatGPT. The study found that five key factors - performance expectancy, effort expectancy, social influence, facilitating conditions, and privacy concerns - were dominant in influencing users' behaviour. These factors align with established technology acceptance models, making them potentially applicable to other developing or developed countries. Moreover, the study highlights the importance of perceived informativeness and task accomplishment related to performance expectancy, suggesting that ChatGPT's effectiveness in providing relevant and comprehensive information and aiding in task completion could be relevant in various contexts.

Additionally, the perceived interactivity of ChatGPT was a significant factor in its usage. This factor extends the UTAUT theory and emphasises the need for high interactivity and responsiveness in chatbots like ChatGPT to increase users' intention to adopt and use the technology. While perceived interactivity may vary across cultures, the general notion that responsive systems are more likely to be perceived as valuable and enjoyable could be relevant in different countries. Further, the data showed that ChatGPT was perceived as informative, helpful in completing tasks, and reliable. Users appreciated its speed of response, quality of responses, and ease of use. Social media and peer influence were significant usage drivers, moderated by age and experience.

Generalising the findings about ChatGPT's perception of other developing countries requires careful consideration of various factors. While the initial study revealed positive perceptions, such as its informativeness, helpfulness, and reliability, its applicability to other developing nations cannot be assumed outright. Cultural variations significantly influence attitudes towards AI systems like ChatGPT, and language plays a crucial role in its adoption. Additionally, the level of technological infrastructure, digital literacy, and socioeconomic conditions in different countries will impact its accessibility and usage. Moreover, the significance of social media and peer influence may vary, with age and experience as potential moderating factors. Researchers must conduct country-specific studies to achieve meaningful generalisation, accounting for local context, needs, and cultural norms. By recognising the unique characteristics of each developing country, we can gain valuable insights into how ChatGPT's perception varies across this diverse global landscape.

Like any other, the study has several limitations and must be interpreted in light of these constraints. Firstly, the current research adopted a qualitative methodology, implying the need for a quantitative approach in the future, probably with the constructs employed in this study. Second, the sample size was limited, consisting of only 32 participants, and the study was conducted in a specific country, i.e. India, which may limit the generalizability of the findings. Future research could consider a larger sample size and explore the factors influencing the usage of ChatGPT in different contexts in different cultural settings. Additionally, the study relied on self-reported data, which may be subject to social desirability bias. Finally, the study did not consider other factors influencing users' behaviour, such as trust in AI, perceived risk, and perceived control. Future researchers could consider using different research methods, such as experiments, to address these limitations to validate the findings. The potential impact of trust in AI perceived risk and perceived control on users' behaviour are other vital aspects worth examining. Lastly, studies on the potential impact of ChatGPT on users' learning outcomes, such as academic performance or work productivity, will bring some exciting outcomes.

Data availability statement

Data will be made available on request.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Devadas Menon: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Visualization, Validation, Supervision, Software, Resources, Project administration, Methodology, Investigation, Funding acquisition, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization. Shilpa K: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Visualization, Validation, Software, Resources, Project administration, Methodology, Investigation, Funding acquisition, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Contributor Information

Devadas Menon, Email: devadasmb@gmail.com.