Abstract

High rates of overlap exist between disorders of gut-brain interaction (DGBI) and eating disorders, for which common interventions conceptually conflict. There is particularly increasing recognition of eating disorders not centered on shape/weight concerns, specifically avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder (ARFID) in gastroenterology treatment settings. The significant comorbidity between disorders of gut-brain interaction (DGBI) and ARFID highlights its importance, with 13–40% of DGBI patients meeting full criteria for or having clinically significant symptoms of ARFID. Notably, exclusion diets may put some patients at risk for developing ARFID and continued food avoidance may perpetuate preexisting ARFID symptoms. In this review, we introduce the provider and researcher to ARFID and describe the possible risk and maintenance pathways between ARFID and DGBI. As DGBI treatment recommendations may put some patients at risk for developing ARFID, we offer recommendations for practical treatment management including evidence-based diet treatments, treatment risk counseling, and routine diet monitoring. When implemented thoughtfully, DGBI and ARFID treatments can be complementary rather than conflicting.

Keywords: feeding and eating disorders, functional gastrointestinal disorder, disorder of gut–brain interaction, eating disorder, avoidant/restrictive eating disorder, cognitive-behavioral therapy

Eating disorders are common and damaging, with an estimated worldwide prevalence between 27.9 million and 59 million,1 and eating disorder symptoms may lead to, exacerbate, or co-occur with disorders of gut-brain interaction (DGBI; also known as functional gastrointestinal disorders).2 Eating disorder behaviors include dietary restriction (i.e., limiting the amount of food eaten, avoiding specific foods, delaying eating); binge eating (i.e., the consumption of an objectively large amount of food in a discrete period of time accompanied by a subjective sense of loss of control); and purging (e.g., self-induced vomiting) and non-purging (e.g., excessive exercise) behaviors.3 These eating disorder behaviors lie along a spectrum in terms of frequency and manifestations, as well as their underlying motivations. In many eating disorders, cognitive symptoms concerning body shape or weight underlie eating disorder behaviors,3 but there is increasing awareness of non-body image-based motivations, especially the relevance of avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder (ARFID) in the gastroenterology setting.4–7 In this conceptual review, we provide a practical guide for the gastroenterology provider in understanding the DGBI and ARFID intersection, including suggested strategies for how to prevent and assess for ARFID in their patients.

What is ARFID?

Avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder (ARFID) differs from other EDs in that it does not involve concerns about body shape or weight3,8 (see Table 1 for comparison of symptoms across various eating disorder diagnoses). ARFID was introduced in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders-fifth edition (DSM-5) and is defined as dietary restriction (reduced overall food intake and/or dietary variety) that results in nutritional deficiency, significant weight loss/inability to gain/grow taller, dependence on supplemental nutrition, and/or impairment in psychosocial functioning.3 ARFID can be diagnosed in the presence of any of these four consequences of dietary restriction, allowing for significant clinician judgment to be used in diagnosis.9

Table 1.

Comparison of eating disorder symptoms across diagnoses.

| Eating Disorder | Dietary Restriction | Binge Eating | Purging Compensatory Behaviors1 | Non-Purging Compensatory Behaviors2 | Body Image Concerns | Low Body Weight |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anorexia nervosa, binge/purge subtype | Recurrent binge eating and/or purging compensatory behaviors required for diagnosis | |||||

| Anorexia nervosa, restricting type | ||||||

| Avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder | ||||||

| Bulimia nervosa | Recurrent purging and/or non-purging compensatory behaviors required for diagnosis | |||||

| Binge-eating disorder | ||||||

| Other specified feeding or eating disorders 3 | ||||||

Note. Black squares indicate symptom is present. Gray squares indicate symptoms may be present, but are not required for diagnosis. White square indicates symptom not present.

May include self-induced vomiting, laxative misuse, diuretic misuse, or other medication misuse.

May include excessive exercise, fasting, or other extreme weight control behaviors.

Other Specified Feeding or Eating Disorder (OSFED) is a classification of eating disturbance for those who do not meet criteria for any other eating disorder.

Motivations Behind Restriction in ARFID

Three primary presentations, or motivations, of ARFID have been described in the literature: fear of aversive consequences, lack of interest/low appetite; and sensory sensitivity (Table 2).3,8 Fear of aversive consequences is characterized by fear of a negative outcome around eating (e.g., choking, vomiting, abdominal pain, diarrhea).3,8 Lack of interest/low appetite is characterized by forgetting to eat, not feeling interested in/enjoying eating, and/or appetite dysregulation (e.g., early satiation, low hunger).3,8 Sensory sensitivity is characterized by avoidance of specific foods due to hypersensitivity to texture, taste, and/or smell.3,8 Importantly, these motivations are not mutually exclusive, and patients can present with any combination of the three.4,10,11

Table 2.

Avoidant/restrictive food intake presentations or motivations.

| Fear of Aversive Consequences | Lack of Interest/Low Appetite | Sensory Sensitivity |

|---|---|---|

| Restricting types or amounts of foods to avoid feared adverse outcome such as vomiting and/or chocking | Restriction/delay in food intake due to reduced appetite | Avoidance of specific foods due to enhanced sensitivity towards texture, taste, and/or smell |

Note. Presentations are the three prototypic motivations behind food avoidance or dietary restriction in avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder. Presentations are dimensional and overlapping, thus some individuals may have only one presentation whereas others may have all three.

Medical and Psychosocial Consequences

Avoidant/restrictive eating crosses the diagnostic threshold for ARFID when it causes medical (e.g., nutritional deficiencies, compromised weight status, dependence on supplemental nutrition) and/or psychosocial problems (e.g., inability to maintain relationships or participate in social activities due to restrictive eating). To meet criteria for ARFID, at least one of these consequences must be present (see Box 1 for a summary of each).

Box 1: Examples of Medical and Psychosocial Consequences of ARFID.

Significant nutritional deficiency

|

Nutritional deficiency.

Even when individuals with ARFID are eating a sufficient amount of food, limited dietary variety due to food avoidance can lead to nutritional deficiency.3,12 One study in children, adolescents, and young adults found that in comparison to healthy controls, individuals with ARFID symptoms reported a significantly lower dietary intake of vitamins K and B12.12 This study also showed ARFID symptoms were associated with significantly lower protein and vegetable intake, with participants frequently not meeting USDA dietary recommendations for protein (in 76%) and vegetable intake (in 86%).12 However, further research is needed to characterize dietary patterns in ARFID, especially in adults.

Compromised weight status.

Low body weight is not an essential criterion for nutritional deficiency. Nevertheless, weight loss or failure to gain weight/grow taller can be a complicating factor in individuals with ARFID. For example, one study found that individuals with ARFID required longer hospitalizations than individuals with anorexia nervosa in order to reach their expected body weight.13 One pediatric study found that 18% of participants lost more than 20% of body weight prior to diagnosis and 39% presented with a weight 20% or more below their target weight.14 To operationalize low weight in ARFID, the DSM-5 criteria for low weight anorexia nervosa (body mass index (BMI) < 18.5 kg/m2 for those >20 years old or < 5th BMI percentile for those ≤20 years old) can be used.3,9 To operationalize significant weight loss in ARFID, a threshold of 5% of unintentional loss of body weight in 1 month or 7.5% loss over 3 months is recommended for adults and 5% loss of usual body weight for those ≤20 years old.15,16

Dependence on supplemental nutrition.

Dependence on enteral or parenteral nutrition, or nutritional supplements to meet calorie needs can fulfill the medical consequences criterion for ARFID.8,17 Dependence on supplemental nutrition for 50% or more of daily intake that is not required by a concurrent medical condition has been recommended as an operational definition.17 Some patients (e.g., ~3%)18 with DGBI who have gastroparesis may be placed on enteral or parenteral nutrition. While typically intended as a temporary measure, patients requiring prolonged use may meet ARFID criteria, though more research is needed to understand ARFID in these patients. Dependence on vitamin supplements (e.g., multivitamins) can also fulfill this criterion even in the absence of current deficiencies, as vitamin supplement use may veil the severity of malnutrition from poor food intake.

Psychologic effects/quality of life impairments.

ARFID is also often associated with marked psychosocial/quality of life impairments, such as social eating difficulties (e.g., avoiding eating at restaurants), familial burden, and overall distress about dietary limitations.19 The type of quality of life impairments can vary, with one pediatric study showing that 100% of outpatients experienced family functioning impairment and 41% experienced social functioning impairment.20 Another interview-based pediatric study showed that 63% of 54 children with food allergies met DSM-5 criteria for ARFID with dietary restrictions deemed beyond what would medically necessary (i.e., beyond allergen-containing foods) and with greater than expected psychosocial impairment reported by caregivers in the form of, for example, distressing and rigid eating behaviors.21 More research characterizing quality of life impairments in ARFID is needed, especially in adults.

Summary

ARFID is characterized by a reduction in food volume and/or variety with one or more of three motivations for restriction—fear of aversive consequences, lack of interest in eating/low appetite, and sensitivity to food characteristics (e.g., taste, texture, smell). ARFID symptoms certainly lie along a spectrum, and medical and/or psychosocial impairments due to avoidant/restrictive eating are required for an ARFID diagnosis. However, the inclusive nature of ARFID criteria can make it difficult to draw a distinct line between long-term management of DGBI and non-normative eating behaviors. We suggest that ARFID should be considered when any of the impairment criteria in Box 1 are met, as the presence of these indicators suggest that dietary restriction has crossed the line into causing harm. This line between normative versus problematic food avoidance/restriction is important, as dietary management is common, often adaptive, and non-problematic (i.e., does not result in the level of impairment as the examples in Box 1) for most patients with many conditions including DGBIs.22

The Relevance of ARFID in DGBIs

The eating disorder-gastrointestinal intersection is not new.23–25 A systematic review of GI symptoms and eating disorders found that nausea, gas, and abdominal pain were the most common symptoms among the 195 articles investigated.25 DGBI affect approximately 40% of adults worldwide26 and approximately 25% of children and adolescents in the US.27 Among those with DGBI, disordered eating patterns (such as food restriction, binge eating, purging) ranges from 5% - 44%.28 More recently, the phenomenon of ARFID in DGBI has been recognized with cross-sectional and retrospective studies.4,10,11,29–36

Overlapping Prevalence between ARFID & DGBI

ARFID prevalence in DGBI.

Clinically significant ARFID symptoms have been reported in 13% - 40% of individuals with DGBIs, in cross sectional self-report survey and retrospective chart review studies.4,10,11,29,31,32 In two retrospective chart review studies of DGBI patients in outpatient gastroenterology clinics (N=410 adults; N=129 pediatric), around 6% of adults and 8% of children met full criteria for ARFID and 17% of adults and 15% of children had clinically significant ARFID symptoms, but not enough information was available to make a definitive diagnosis.4,10 Another retrospective chart review study of 223 adult DGBI patients who were seen by a psychologist, identified ARFID in almost 13%.33 Cross-sectional self-report survey studies among adult outpatients with DGBI have shown varying frequencies of ARFID—two studies using different surveys showed 40% screened positive for ARFID,11,29 but another study showed 19.6% screened positive for ARFID.32 The fear of aversive consequences motivation has been the most frequent ARFID motivation across all studies and in fact, one study screening for the ARFID fear motivation alone found a positive screen in 18.5% of community individuals with irritable bowel syndrome or inflammatory bowel disease.37 Differences in self-report frequencies may be due to varying cutoffs applied across studies on one ARFID screening questionnaire (the Nine Item ARFID Screen),38,39 as well as characteristics of the clinical populations. Finally, a cross-sectional self-report survey study found that among a community of self-identified “picky eater” adults who self-reported DGBI symptoms, 11% met diagnostic criteria for ARFID.31 To our knowledge, no study to date has investigated the frequency of ARFID in DGBI using semi-structured or clinician interview (the gold standard for diagnosis of eating disorders), thus current frequency estimates are limited by the use of self-report surveys.

DGBI prevalence in ARFID.

Conversely, DGBI symptoms are also present in patients with ARFID. An investigation of 168 pediatric and adult patients seeking outpatient eating disorder treatment found that 30% met criteria for a DGBI, and that DGBI frequency did not differ between those with ARFID versus another eating disorder.34 Another study found among inpatient adults with underweight ARFID, 64% had a history of three of more GI diagnoses, including some DGBIs (e.g., irritable bowel syndrome, gastroparesis), and 100% presented with a minimum of five GI symptoms.35

Proposed ARFID & DGBI Risk and Maintenance Pathways

Given the bi-directional overlap in frequencies of DGBI and ARFID patients, it is apparent that there is relatively high comorbidity between DGBI and ARFID symptoms. While dietary management in DGBI populations can be helpful and non-problematic for many patients, a subset can develop problematic dietary restriction as seen in ARFID. We (HBM & KS) and others have suggested that the line is crossed to ARFID when restrictive eating negatively impacts quality of life or medical functioning.40,41 However, our understanding as to how DGBI and ARFID interact, including which may be more likely to come first and how one may exacerbate the other, is limited.

Risk for ARFID Related to DGBI

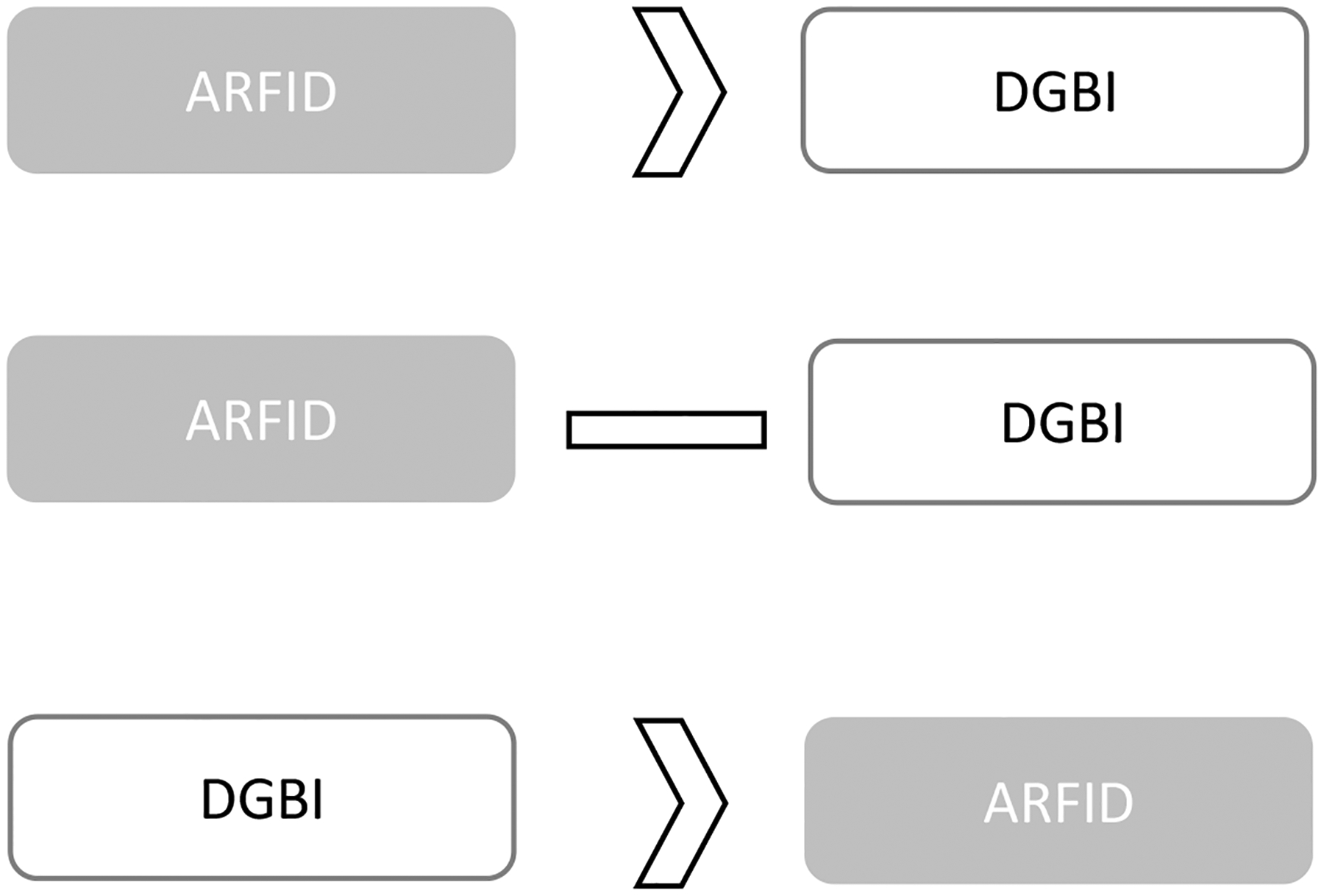

As described above, a subset of individuals with DGBI may already have or may be at risk for ARFID development. We propose and summarize three pathways for ARFID development in the context of DGBIs (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Possible development pathways for ARFID and DGBI.

ARFID may exist prior to a DGBI (DGBI symptoms develop as a consequence of ARFID symptoms); ARFID may present concurrently with a DGBI (ARFID and DGBI symptoms can occur simultaneously while not being directly related); DGBI may exist prior to ARFID (ARFID develops to alleviate DGBI symptoms)

Pre-existing ARFID → DGBI

No studies to date have evaluated DGBI developing in the context of ARFID or ARFID as a risk factor for a future DGBI. However, it is possible that some patients may develop DGBI symptoms due to the neurosensory changes generated by ARFID. The learned history of food avoidance and reaction to such events could make ARFID patients more vulnerable through heightened hypervigilance around GI sensations or heightened visceral hypersensitivity. More research is needed to understand the prevalence of DGBI developing as a consequence of ARFID and the mechanisms involved.

ARFID Concurrent with DGBI

Some patients may develop both ARFID and a DGBI independent of each other. For example, one study found that 1% of ARFID participants had chronic belching, which may be unrelated to ARFID symptoms and have developed independently.4 In this case, separate, non-overlapping factors may maintain the DGBI and ARFID symptoms. However, psychological and physiological factors can be mutually strengthening, therefore the presence of both places a patient at high risk for the symptoms of one disorder to exacerbate the other.42

Pre-existing DGBI → ARFID

Given the high frequency of ARFID among patients with DGBI and the routine use of dietary restriction for symptom management, the development of ARFID symptoms in the context of DGBIs is presumably the most important pathway for the GI provider to consider. Theoretical models as well as emerging empirical evidence suggest that ARFID symptoms may arise as a result of GI pain or discomfort.4,8,10,29 Though 3–23% of individuals with DGBI exhibit more than one ARFID motivation (i.e., sensory, lack of interest, fear),4,10,11 distinct characteristics of individuals across motivations suggest differing etiological pathways, some of which may be associated with existing DGBI symptoms:

Fear conditioning (i.e., initially neutral scenarios induce heightened fear after aversive events) after triggering event (e.g., choking, vomiting episode)

Increased susceptibility to fear conditioning (e.g., due to visceral hypersensitivity) around GI symptoms

Significant stressor or comorbid medical or psychological conditions that reduce appetite or interest in food

Chronic consumption of a limited variety of foods

The below descriptions posit how these etiological pathways may theoretically lead to ARFID development in individuals with DGBIs. Importantly, however, more empirical research is needed to support each of these hypotheses.

Fear conditioning after triggering event.

ARFID may develop in part from a triggering event (e.g., choking, vomiting). Specifically, the triggering event may lead to avoidance of certain foods due to fear of a similar episode from occurring in the future. The individual may experience a sudden and severe onset of avoidant/restrictive eating after the triggering incident, which may cross the line to ARFID when avoidant/restrictive eating persists and leads to medical consequences or and functional impariments.43 For example, a patient with chronic nausea who has a vomiting episode may connect specific foods to vomiting and quickly limit their dietary variety to prevent future vomiting episodes. In some cases though, the development of ARFID may be more nuanced and potentially arise in tandem with the DGBI after a triggering event (e.g., after a viral infection) due to dysregulation in gut-brain signaling. Further research is needed to understand the nature and course of fear conditioning of ARFID in response to specific triggering events.

Increased susceptibility to fear conditioning.

A disproportionate sensory response to normal eating and digestion, as seen with visceral hypersensitivity, may be a risk factor for fear conditioning with food intake, further leading to the development of ARFID. Preoccupation with and anxiety around GI sensations (i.e., GI-specific anxiety) has been identified as key maintenance mechanism of DGBI like irritable bowel syndrome.44–46 Over time, the patient connects eating with GI symptoms; in attempt to control symptoms, restricting types and amounts of foods reinforces the learned association with pain, even if food restriction does not reliably prevent or alleviate symptoms. For example, a patient with irritable bowel syndrome may start the low FODMAP diet (i.e., a diet low in fermentable oligosaccharides, disaccharides, monosaccharides, and polyols, which are short-chain carbohydrates not well-absorbed by the small intestine), but experiences difficulty with re-introduction due to difficulty tolerating any GI distress with reintroduction and/or generalizes food avoidance beyond the low FODMAP diet.

ARFID may develop when food avoidance is severe enough to result in medical and/or psychosocial consequences. ARFID development through this pathway may occur over a longer time period (compared to the triggering event pathway), where an individual experiences uncomfortable GI sensations repeatedly prior to developing ARFID symptoms. This pathway is also likely associated with ARFID fear of aversive consequences, which has consistently high rates in individuals with DGBI.4,10,11,29

Significant life stressors or co-morbid non-GI medical and psychological conditions.

Significant life stressors or increases in symptoms of existing psychological or non-GI-related medical conditions may result in the onset of ARFID symptoms more slowly and over a longer period of time. This is in contrast to the fear conditioning pathway where ARFID symptoms develop after a specific triggering event or in direct response to longstanding DGBI symptoms. Thus, the life stressors/non-GI comorbidities pathway may be most closely tied to the lack of interest/low appetite motivation, rather than the fear of aversive consequences motivation.43 Supporting this distinction, individuals with the lack of interest/low appetite motivation may be more likely to have comorbid medical conditions, ADHD, and mood disorder symptoms than individuals with other ARFID motivations.43,47 For example, an individual may experience loss of appetite over the course of several weeks or months as a result of major depressive disorder, which may result in ARFID when the change in appetite exceeds what would be expected from major depressive disorder alone and results in psychosocial and/or medical consequences.

Chronic limited diet variety.

Limited diet variety over prolonged periods of time may put some individuals at risk for ARFID. Limited diet variety is potentially most closely associated with the ARFID sensory sensitivity motivation. This pathway may also be associated with combined sensory selectivity and low appetite/lack of interest motivations,43,48 where both selective eating and low appetite result in limited diet variety over time, leading to psychosocial and/or medical consequences. Individuals with the sensory sensitivity or combined sensory sensitivity/low appetite motivation find only a small number of foods to be palatable, which may be due to hypersensitive taste perception.8 Given that the sensory sensitivity motivation is relatively less common in individuals with DGBIs than the lack of interest/low appetite and fear of aversive consequences motivation,4,10,11,29 this pathway may be less relevant for the GI provider.

Bidirectional Factors that Perpetuate (Maintain) ARFID and DGBIs

Identifying how ARFID and DGBI may reinforce each other can be crucial to inform what factors can be targeted for symptom improvements. We describe theoretical models in which DGBI symptoms may perpetuate ARFID symptoms and ways in which ARFID symptoms may perpetuate DGBI symptoms, providing supporting evidence where available. Two key factors in this model are:

Dietary restriction: A limited diet (volume and/or variety) likely maintains sensorimotor disturbances in GI functioning, and patients may associate any alleviation of DGBI symptoms with dietary restriction, thus reinforcing or extending restrictive behaviors.

GI-Specific Anxiety: Restrictive eating may lessen GI-specific anxiety in the short-term, but perpetuate it in the longer-term (and possibly associated visceral hypersensitivity).

DGBI maintenance of ARFID

Several factors may perpetuate ARFID symptoms among individuals with DBGI. First, engaging in dietary restriction may temporarily alleviate DGBI symptoms and thus reinforce dietary restriction as a strategy for symptom reduction and management. Additional factors may maintain ARFID symptoms, such as dysregulation of appetite signals in the brain in the lack of interest/appetite motivation and high fear responsiveness in the fear of aversive consequences motivation.8 For example, decreased appetite due to gastric emptying or accommodation disturbances may perpetuate eating small food volumes. However, it is still unknown whether appetite dysregulation is due to motility disturbances or the consequence of de-conditioning over time due to restricted food intake. Further complicating the clinical picture, visceral hypersensitivity may be independently associated with both ARFID49 and DGBI symptoms,50–52 and it may be unclear whether visceral hypersensitivity is a consequence of one or the other. However, in the context of visceral hypersensitivity in DGBI, individuals with ARFID may interpret innocuous GI sensations as potentially harmful, further reinforcing fear and avoidance of food.

Finally, while DGBI are known to be associated with food intolerances in the absence of true allergies,53 there is some growing evidence of nonclassical food allergy—at least in irritable bowel syndrome (IBS).54,55 While future research is needed, there may be an interplay between localized food intolerance in DGBI with visceral hypersensitivity and fear conditioning processes, given that treatments promoting dietary exclusion (e.g., in the low FODMAP diet) and dietary expansion (e.g., in exposure-based CBT) have proven efficacy for IBS.56

ARFID maintenance of DGBI

ARFID symptoms may perpetuate DGBI symptoms, in terms of both sensory and motility processes. Fear of GI symptoms around eating may perpetuate visceral hypersensitivity. Furthermore, while food avoidance/restriction may ease fear of GI symptoms occurring in the short-term, it can perpetuate fear around GI symptoms in the longer-term. Specifically, individuals with ARFID may become conditioned to interpret any changes in GI symptoms to be a consequence of food. Then, over time, they may experience heightened GI-specific anxiety which then increases DGBI symptoms. Dietary restriction and weight loss may also perpetuate sensorimotor disturbances in DGBIs. For example, significant dietary restriction seen in anorexia nervosa and ARFID has been associated with delayed gastric emptying4,36 and increased colonic transit time (in anorexia nervosa).57–59 Further, significant weight loss from functional dyspepsia (albeit not necessarily at an objectively low body mass index) has been associated with decreased gastric tolerance60,61 and accommodation62,63 impairments.

Screening for ARFID Symptoms

Understanding risk and maintenance factors for ARFID in individuals with DBGI is essential for ensuring appropriate treatment. Importantly, recommendations for treatment of DGBI (e.g., elimination/exclusion diets, consuming smaller volumes of food at mealtimes)64–66 may conflict with recommendations for treatment of ARFID (e.g., increased food variety and meal sizes).67–69 Thus, screening for ARFID symptoms may be helpful in ensuring that clinicians do not prescribe some of the standard DGBI treatment recommendations that may be counterproductive in those with ARFID.

Suggested current screening options.

Although we present several available self-report questionnaires below, engaging the patient around eating behavior themes during a clinical assessment may be sufficient to 1) get a sense of patients that may have a problematic relationship with food and 2) reinforce to the patient that eating behaviors are an important part of GI health. Clinical questioning may be helpful over four domains: the impact of food and eating on quality of life, eating-related distress, weight suppression, and dietary restriction (see Table 3 for a checklist of domains to cover and sample questions). Despite some behaviors, such as eating small portion sizes, being common options to alleviate DGBI symptoms, clinicians can assess when the restrictive eating behaviors are causing medical and/or psychosocial impairment that could indicate a need for intervention (Box 1). If the patient has a positive red flag, providers may consider referral to a behavioral health specialist or dietitian for further assessment (or in the case of medical instability, referral to inpatient or similar program).

Table 3.

Example questions for ARFID symptom screening.

| Domain | Example Questions | Red Flags for ARFID |

|---|---|---|

| Quality of life | Does eating or making decisions about food get in the way of your ability to live the life you would like to? | Patient reports that eating or making decisions about food is interfering with relationships, work/school, or other activities. |

| Eating-related distress | Have you ever felt like food was an issue for you?* How much time, mental energy, and effort do you spend around eating and food choices? |

Presence of a past eating disorder, which may confer risk for difficulties with restrictive/elimination diets, even if in remission. Patient reports that thinking about food or eating interferes with their ability to concentrate on tasks they are actively engaged in (e.g., work, conversations, reading) or that they wish to spend less time thinking about or preparing food. |

| Weight trajectory1 | Have you lost weight due to your GI symptoms? If so, what was your usual weight range prior to this weight loss?* Have you had difficulty gaining weight due to your GI symptoms? |

Unintentional weight loss of >5% over 1 month, 7.5% over 3 months, or >10% over 6 months or lack of weight gain despite intention to gain weight. Difficulty gaining weight/growing Low weight (Body mass index (BMI) < 18.5 kg/m2 for >20 years old; < 5th BMI percentile for ≤20 years old) |

| Dietary restriction: Delaying eating and limiting food intake | Over the past month, what has a typical day of eating looked like for you?2

If patient reports delaying eating or limiting intake: What are the reasons you wait to eat or limit the amount you eat?3 Over the past month, have you had difficulty eating enough, for example because of forgetting to eat or worry about having GI symptoms? |

Delaying eating (e.g., regularly going >6 waking hours without eating) Limiting food intake (e.g., low caloric intake, small portion sizes) |

| Dietary restriction: Food avoidance | Over the past month, have you avoided eating certain foods?2 Do you have any strict food rules? |

Patient reports eating only a few foods, relying on liquid supplements, eating only home-cooked food, self-directed diet changes without clear symptom benefit, and/or inflexibility around food choices. |

| Ruling out other eating disorder behaviors4 | What do you do for exercise? How often? Do you keep track of your calorie intake? Would gaining weight upset you? |

Patient reports positive to dietary restrictions or diminished quality of life, but negative for shape and weight concerns. |

Note. ARFID=Avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder, BMI= body mass index, GI=gastrointestinal. This table may be used as a starting point for screening for ARFID symptoms in individuals with DGBI. Red flags should be seen as a potential sign of ARFID, rather than a definite indicator that an ARFID diagnosis is warranted. When concerns about medical symptoms due to restrictive eating are present, see the Academy for Eating Disorders’ Medical Care Guidelines70.

Questions formed for bare minimum assessment that GI clinicians can address with patients.

Significant weight loss can have detrimental physical consequences, even when an individual is not in the underweight BMI range.

Items adapted from the Eating Disorder Examination.

If patient reports shape/weight-related motivations for dietary restriction, consider screening for eating disorders other than ARFID.

Validated ARFID screening measures do not yet exist for patients with DGBI. However, the Nine-Item ARFID Screen (NIAS) is a short, freely available self-report questionnaire validated for ARFID more generally in children, adolescents, and adults with ARFID.38,39 The NIAS subscales also provide information about which ARFID motivation(s) a patient might present with.38 Subscales are measured on a score of zero through fifteen, with picky eating subscale and fear subscale having a threshold score of 10 and appetite subscale at a threshold score of 9.39 The NIAS may provide a starting point for the assessment of ARFID in patients with DGBI and should be used in conjunction with an assessment to rule-out non-ARFID eating disorders. The Fear of Food Questionnaire (FFQ) is also a recently developed questionnaire that provides assessment of maladaptive fear of foods, but does not yet include a cutoff for clinically significant food fears.37 Another possible screening tool is the Pica, ARFID, Rumination Disorder Interview – ARFID Questionnaire (PARDI-AR-Q). The PARDI-AR-Q, adapted from the original PARDI interview, is a self-report questionnaire that assess a likely ARFID diagnosis and severity of symptoms.73

Targeted screening.

While it would be ideal to screen all individuals with DGBI for ARFID, GI providers may consider only screening individuals who present with specific characteristics that have been associated with ARFID in patients with DGBI and to ask only targeted, high-yield questions. The presence of ARFID symptoms has been associated with increased eating/weight-related complaints 4, 10, stomach-related GI diagnoses 4, 29, abdominal pain and constipation-related GI diagnoses 4, and a higher total number of GI symptoms 4. Though these characteristics are all common in the DGBI patient population, individuals with these features may stand to benefit significantly from ARFID screening.4 Using screening questions (sample questions noted in Table 3) as a bare minimum assessment, can elucidate whether patients are engaging in normative restriction in response to GI symptoms, or whether their symptoms may cross the threshold into ARFID. Notably, ARFID symptoms in patients with DGBI are present in patients across the weight spectrum,4,10,29,34 underscoring the importance of screening for ARFID symptoms even in patients who are not obviously underweight or malnourished. After screening for current ARFID symptoms and for characteristics that may put an individual at high risk for developing ARFID, appropriate treatment recommendations can be made. Medical and psychosocial consequences (i.e., those listed in Box 1) are high-yield areas that clinicians can focus on to assess for ARFID as efficiently as possible.

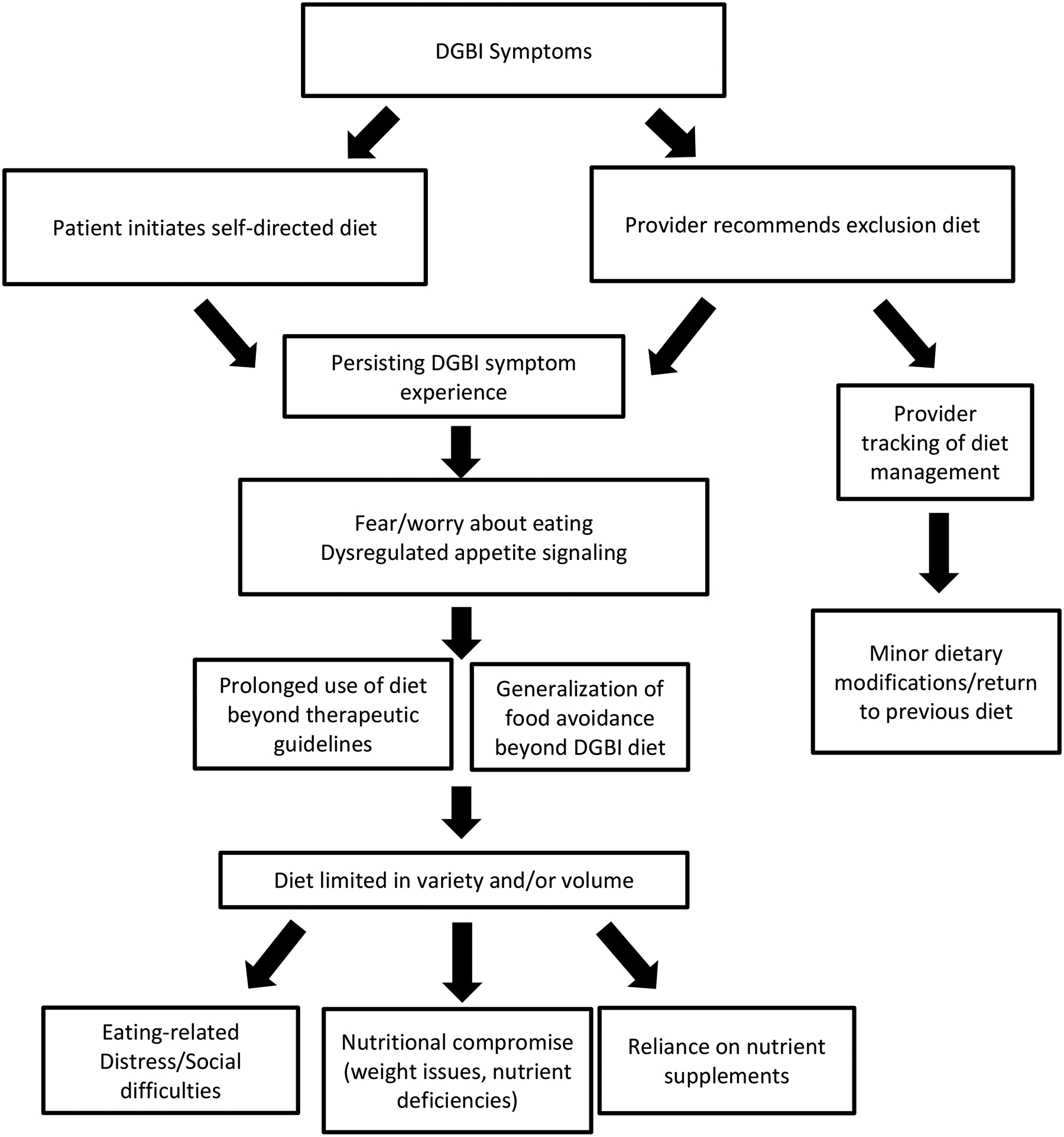

Preventing ARFID Development in DGBI

In our opinion, a key to preventing ARFID development in the context of a DGBI is to be mindful of how dietary management may put a subset of patients at risk for ARFID. Dietary management of DGBI has become a mainstay of treatment recommendations and are often self-initiated by patients. Dietary approaches involve exclusion diets (eg, where specific foods that are high in short-chain carbohydrates that the small intestine is unable to absorb are removed from the diet temporarily as in the low FODMAP diet74–76 or specific foods are removed entirely as in a gluten-free or dairy-free diet), modified intake of specific foods (e.g., low-fat, low-particle diet for gastroparesis/dyspepsia),22,77 and modified food timing (e.g., small frequent meals for gastroparesis/dyspepsia).22,77 An investigation of 495 adult and pediatric patients presenting for neurogastroenterology evaluation found that 39% had a history of exclusion diets, and those with exclusion diet histories were over three times as likely to have ARFID symptoms.30 Another study reported that of the 13% of gastroenterology patients that already met ARFID criteria, 89% were prescribed a low FODMAP diet.33 While dietary approaches are highly acceptable to many patients6 and often prescribed by providers,78 dietary management may exacerbate ARFID symptoms in a subset of patients (see Figure 2). While there is not yet prospective research elucidating who might be most at-risk for developing ARFID when prescribed an exclusion diet, routine diet monitoring (as described below) may help to identify ARFID symptoms and intervene early. Some work has suggested that modified dietary exclusion approaches or cognitive-behavioral treatment may be a better fit than the low FODMAP diet for individuals with high levels of GI-specific anxiety, avoidance, and/or weight loss.56 We provide several recommendations based on evidence-based diet protocols, other consensus recommendations,79 and our own clinical experience.

Figure 2.

Potential risk for ARFID through DGBI exclusion diets.

Education about evidence-base.

It is important for patients to be educated on proper diet implementation for both effectiveness and ARFID prevention. Many patients believe that certain foods80 or food insensitivities81 aggravate symptoms and may frequently self-initiate exclusion diets.30 In addition, there are many diets without quality evidence of effectiveness that patients may know about, have already tried, or were recommended by previous providers. Thus, early conversations about which diets have evidence to support their use for DGBI and identifying food triggers is important in reducing dietary restrictions that may not be effective. The low FODMAP diet has the most evidence for efficacy for adults with irritable bowel syndrome, but the evidence behind it is still mixed82,83 and with only one small randomized trial in children.84 In fact, emerging evidence suggests traditional dietary advice (e.g., creating a regular pattern of eating, reducing processed food consumption) is no worse than the low FODMAP diet in reducing some irritable bowel syndrome symptoms78,85,86 and is more acceptable to patients (e.g., lower cost, easier to shop for/eat out).86 There is limited evidence for other dietary approaches (e.g., gluten-free;82,87 dairy-free diet88,89) in irritable bowel syndrome and there is mixed evidence for dietary approaches to managing other DGBI (e.g., low-fat, low-particle diet90 for gastroparesis/dyspepsia).91,92

Risk counseling.

Early acknowledgement of the potential risk exclusion diets pose on nutritional and psychosocial impairment is also important. For highly restrictive diets like the low FODMAP diet, there is temporary restriction (e.g., 4–6 weeks of high FODMAP food exclusion) with a systematic reintroduction of foods to identify a handful foods high in FODMAPs that the patient may either avoid or limit quantities of.93 Without guidance to the proper protocol, exclusion diets like the low FODMAP diet can be more harmful than helpful. For example, prolonged use of the elimination phase of the low FODMAP diet has been associated with significant nutrient deficiencies.94–96 In addition, exclusion diets have been significantly associated with poorer quality of life,76 and greater dietary restrictions have been associated with poorer nutritional status.97 Providers should candidly discuss these nutritional and psychosocial risks (including the high association between history of exclusion diet use and ARFID symptoms) to facilitate prevention. For a full review of the psychosocial and nutritional risks of different dietary approaches for DGBI see the recent Rome Working Team report.81

Routine diet monitoring.

If a patient is prescribed any exclusion diet, continual monitoring is needed. Patients can be referred to dietitians to work on diet flexibility to minimize negative impact on psychosocial functioning.5 If the exclusion diet is not improving symptoms, then it should be discontinued.5,75 A lack of longitudinal follow up with providers may put some patients at risk to continue overly restrictive exclusion diets like the exclusion phase of the low FODMAP diet for a prolonged period.5 Regular assessment of diet by GI providers may facilitate prevention of ARFID as well as recognition of when patients have crossed the line into developing ARFID (e.g., as in Table 3). In addition, guided dietary therapy is recommended to identify any food triggers that would be warranted to exclude for individuals with DGBI in the absence of a true food allergy, with recommendations against investigation using current food intolerance and sensitivity testing.81

Treating Comorbid ARFID and DGBI Symptoms

Common Treatment Recommendations for ARFID

Currently, evidence-based treatment approaches for ARFID primarily focus on some form of behavioral intervention. Behavioral treatments involve gradual exposure to food types and amounts, and as applicable, correcting nutrient deficiencies, decreasing reliance on supplemental nutrition, increasing weight, and/or decreasing psychosocial impairment. Treatment teams can include a combination of behavioral health providers, dietitians, and primary care providers, depending on the case.68 Psychopharmacological approaches can also be used in conjunction with behavioral treatment.98 For example, mirtazapine, a drug that may promote gastric emptying according to preliminary data and decreases nausea and vomiting, may be used to facilitate weight gain in patients with ARFID.99–101

Cognitive-behavioral treatment for ARFID.

Several case series and open trials have shown cognitive-behavioral treatment (CBT) for ARFID is highly feasible and acceptable, with promising results for efficacy.67,69,102–105 Our team has developed an 8-session CBT for ARFID that has developed in the context of DGBI that targets both ARFID and DGBI outcomes, with preliminary, favorable results106 and a randomized clinical trial in progress. CBT for DGBI + ARFID includes self-monitoring of food intake, regularizing eating patterns, behavioral and food exposure, and maintenance planning (see Box 2).68 Similar to treatments for each DGBI44,108 and ARFID107 the primary component in CBT for DGBI + ARFID is exposure to fear foods aimed to reduce negative emotions (e.g., fear, disgust) and correct predictions around the consequences of eating (e.g., learning that the outcome is more tolerable than expected). For adolescents under the age of 16, family-based treatment104,107 or parent-training105,110 can be used, in which parents support the child in increasing dietary volume and variety. While future research is certainly needed on for whom CBT for ARFID is most beneficial, we would recommend clinicians consider CBT (or a similar approach) for patients with DGBI + ARFID, regardless of whether ARFID developed prior to or subsequent to the DGBI.

Box 2: Components of Cognitive-Behavioral Treatment for ARFID in the Context of DGBI.

Education

|

Note. ARFID=Avoidant/Restrictive Food Intake Disorder; DGBI=Disorders of Gut-Brain Interaction. Techniques are modeled from cognitive-behavioral treatment for ARFID107 and exposure-based brain-gut behavioral therapies for DGBI.44,108,109 An 8-session version of the treatment is currently being tested.

Of note, some patients may require a higher level of care to receive sufficient support around meals to make changes in their eating or for medical monitoring at an inpatient level.70,72 For example, treating patients with ARFID who are on enteral/parenteral nutrition is not recommended on a regular outpatient level, as it is in most ARFID cases insufficient to support cessation of enteral/parenteral nutrition supports.107 General guidelines for medical care standards can be found in the Academy for Eating Disorders Medical Care Standards Guide70 and primary care best practices.72

Balancing Existing ARFID with DGBI Treatment Recommendations

When an individual presents with both ARFID and a DGBI, treatment recommendations should be adjusted to address symptoms of both disorders.

Modified exclusion diets.

We recommend that traditional dietary advice over an exclusion diet be considered for patients with DGBI + ARFID. As previously mentioned, there is increasing evidence that traditional dietary advice has similar effects on DGBI symptoms as exclusion diets (e.g., for irritable bowel syndrome).78,85,86 The United Kingdom’s National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE)111 guidelines for irritable bowel syndrome actually suggest traditional dietary advice with eating on a regular schedule (e.g., ever 3–4 hours), staying hydrated, and limiting alcohol and caffeine consumption. In fact, some aspects of traditional dietary advice (e.g., establishing regular eating patterns) are a key component of CBTs for ARFID.

If there is rationale to prescribe an exclusion diet for DGBI symptoms, working in collaboration with a dietitian should be considered for patients to bridge the gap between increasing food volume and variety in ARFID treatment while simultaneously improving GI symptoms using an exclusion diet. Without dietitian guidance, the reintroduction/personalization phase of the low FODMAP diet can have diminished compliance.112 The exclusion period of the low FODMAP diet should only last up to 6 weeks; afterwards, it is necessary for food to be reintroduced to mitigate nutritional deficiencies.75 Reintroduction is also necessary to prevent maintenance of ARFID symptoms. Additionally, there are other emerging, modified exclusion diet recommendations that may be more suitable for patients with ARFID. For example, a less restrictive low FODMAP diet following the reintroduction phase may be an option.96,113

Neuromodulators.

Pharmacological treatments may be used concurrently with CBT for ARFID to reduce maladaptive DGBI symptoms. We take a symptom-based approach to selection of neuromodulators, being cognizant of any underlying dysmotility while leveraging or avoiding potential side effects. For example, buspirone, gabapentin, tricyclic antidepressants114, and mirtazapine have all been used in patients with functional dyspepsia114,115, but buspirone and gabapentin are less likely to be constipating and mirtazapine has evidence in dyspeptic patients requiring weight gain.116 While they have yet to be studied, in our clinical experience, neuromodulators may increase the tolerability and acceptability of food exposures in CBT for some patients with DGBI. However, it should be noted that neuromodulators are not currently labeled for use treating DGBI symptoms.

Conclusions

In the current review, we aimed to investigate the intersection of ARFID and DGBIs. The high prevalence rate of ARFID symptoms in DGBI patients4,10,11,29,31,32 highlights the necessity of being aware of the possible bidirectional risk and maintenance pathways between these conditions, particularly the possible risk for ARFID development in the context of a DGBI. Notably, more research is needed to elucidate whether appetite dysregulation is due to motility disturbances or the consequence of de-conditioning over time due to restricted food intake. For the GI provider, it is important to be cognizant of the potential pitfalls of DGBI dietary treatments and to take a cautious approach when using them to prevent both ARFID exacerbation and development.75 Continued research on the risk and maintenance factors is also necessary to increase our understanding of how best to prevent ARFID and intervene on interacting DGBI and ARFID processes.

Conflicts of Interest and Funding Disclosure:

IW, SRA, and SC have no personal or financial conflicts to declare. HBM and JJT receive royalties from Oxford University Press for their forthcoming book on rumination syndrome. KS has received research support from Ironwood and Urovant and has served as a consultant to Arena, Gelesis, GI Supply, and Shire/Takeda. BK has received research support from AstraZeneca, Takeda, Gelesis, Medtronic, Genzyme and has served as a consultant to Shire, Takeda, and Ironwood. JJT receives royalties from Cambridge University Press for the sale of her book, Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy for Avoidant/Restrictive Food Intake Disorder: Children, Adolescents, and Adults and The Picky Eater’s Recovery Book. HBM, KS, BK, and JJT have no personal conflicts to declare. This work was supported by the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases—K23 DK120945 (KS) and K23 DK131334 (HBM).

References

- 1.Santomauro DF, Melen S, Mitchison D, Vos T, Whiteford H, Ferrari AJ. The hidden burden of eating disorders: an extension of estimates from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet Psychiatry. 2021. Apr;8(4):320–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Drossman DA, Hasler WL. Rome IV—functional GI disorders: disorders of gut-brain interaction. Gastroenterology. 2016;150(6):1257–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.American Psychiatric Association, American Psychiatric Association, editors. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM-5. 5th ed. Washington, D.C: American Psychiatric Association; 2013. 334–338 p. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Burton Murray H, Bailey AP, Keshishian AC, Silvernale CJ, Staller K, Eddy KT, et al. Prevalence and characteristics of avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder in adult neurogastroenterology patients. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020. Aug;18(9):1995–2002.e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Werlang ME, Sim LA, Lebow JR, Lacy BE. Assessing for eating disorders: A primer for gastroenterologists. Am J Gastroenterol. 2021. Jan;116(1):68–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chey WD. Elimination diets for irritable bowel syndrome: Approaching the end of the beginning. Am J Gastroenterol. 2019. Feb;114(2):201–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Harer KN, Eswaran SL. Irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2021. Mar;50(1):183–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Thomas JJ, Lawson EA, Micali N, Misra M, Deckersbach T, Eddy KT. Avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder: A three-dimensional model of neurobiology with implications for etiology and treatment. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2017. Aug;19(8):54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Harshman SG, Jo J, Kuhnle M, Hauser K, Burton Murray H, Becker KR, et al. A moving target: How we define avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder can double its prevalence. J Clin Psychiatry. 2021. Sep 7;82(5). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Burton Murray H, Rao FU, Baker C, Silvernale CJ, Staller K, Harshman SG, et al. Prevalence and characteristics of avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder in pediatric neurogastroenterology patients. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2021. Dec 14;Publish Ahead of Print:995–2002.e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Burton Murray H, Riddle M, Rao F, McCann B, Staller K, Heitkemper M, et al. Eating disorder symptoms, including avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder, in patients with disorders of gut-brain interaction. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2021. Oct 24; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Harshman SG, Wons O, Rogers MS, Izquierdo AM, Holmes TM, Pulumo RL, et al. A diet high in processed foods, total carbohydrates and added sugars, and low in vegetables and protein Is characteristic of youth with avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder. Nutrients. 2019. Aug 27;11(9):2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Strandjord SE, Sieke EH, Richmond M, Rome ES. Avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder: Illness and hospital course in patients hospitalized for nutritional insufficiency. J Adolesc Health. 2015. Dec;57(6):673–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cooney M, Lieberman M, Guimond T, Katzman DK. Clinical and psychological features of children and adolescents diagnosed with avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder in a pediatric tertiary care eating disorder program: a descriptive study. J Eat Disord. 2018. Dec;6(1):7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Becker P, Carney LN, Corkins MR, Monczka J, Smith E, Smith SE, et al. Consensus statement of the academy of nutrition and dietetics/american society for parenteral and enteral nutrition: indicators recommended for the identification and documentation of pediatric malnutrition (undernutrition). Nutr Clin Pract. 2015. Feb;30(1):147–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.White JV, Guenter P, Jensen G, Malone A, Schofield M, Academy Malnutrition Work Group, et al. Consensus statement: Academy of nutrition and dietetics and american society for parenteral and enteral nutrition: Characteristics recommended for the identification and documentation of adult malnutrition (Undernutrition). J Parenter Enter Nutr. 2012. May;36(3):275–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Eddy KT, Harshman SG, Becker KR, Bern E, Bryant-Waugh R, Hilbert A, et al. Radcliffe ARFID workgroup: Toward operationalization of research diagnostic criteria and directions for the field. Int J Eat Disord. 2019. Apr;52(4):361–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Parkman HP, Blackford AL, Yates KP, Grover M, Malik Z, Schey R, et al. Patients with gastroparesis using enteral and/or parenteral nutrition: Clinical characteristics and clinical outcomes. Under Review. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 19.Becker KR, Keshishian AC, Liebman RE, Coniglio KA, Wang SB, Franko DL, et al. Impact of expanded diagnostic criteria for avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder on clinical comparisons with anorexia nervosa. Int J Eat Disord. 2019. Mar;52(3):230–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zickgraf HF, Murray HB, Kratz HE, Franklin ME. Characteristics of outpatients diagnosed with the selective/neophobic presentation of avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder. Int J Eat Disord. 2019. Apr;52(4):367–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Patrawala MM, Vickery BP, Proctor KB, Scahill L, Stubbs KH, Sharp WG. Avoidant-restrictive food intake disorder (ARFID): A treatable complication of food allergy. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2022. Jan;10(1):326–328.e2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pace LA, Crowe SE. Complex relationships between food, diet, and the microbiome. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2016. Jun;45(2):253–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Frank GKW, Golden NH, Burton Murray H. Introduction to a special issue on eating disorders and gastrointestinal symptoms—The chicken or the egg? Int J Eat Disord. 2021. Jun;54(6):911–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.West M, McMaster CM, Staudacher HM, Hart S, Jacka FN, Stewart T, et al. Gastrointestinal symptoms following treatment for anorexia nervosa: A systematic literature review. Int J Eat Disord. 2021. Jun;54(6):936–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Riedlinger C, Schmidt G, Weiland A, Stengel A, Giel KE, Zipfel S, et al. Which symptoms, complaints and complications of the gastrointestinal tract occur in patients with eating disorders? A systematic review and quantitative analysis. Front Psychiatry. 2020. Apr 20;11:195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sperber AD, Bangdiwala SI, Drossman DA, Ghoshal UC, Simren M, Tack J, et al. Worldwide prevalence and burden of functional gastrointestinal disorders, results of rome foundation global study. Gastroenterology. 2021. Jan;160(1):99–114.e3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Robin SG, Keller C, Zwiener R, Hyman PE, Nurko S, Saps M, et al. Prevalence of pediatric functional gastrointestinal disorders utilizing the rome IV criteria. J Pediatr. 2018. Apr;195:134–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Satherley R, Howard R, Higgs S. Disordered eating practices in gastrointestinal disorders. Appetite. 2015. Jan;84:240–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Burton Murray H, Jehangir A, Silvernale CJ, Kuo B, Parkman HP. Avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder symptoms are frequent in patients presenting for symptoms of gastroparesis. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2020. Dec;32(12). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Atkins M, Zar-Kessler C, Madva EN, Staller K, Eddy KT, Thomas JJ, et al. Relationship of exclusion diets with avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder in neurogastroenterology patients. Under Review. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 31.Nicholas JK, Tilburg MAL, Pilato I, Erwin S, Rivera-Cancel AM, Ives L, et al. The diagnosis of avoidant restrictive food intake disorder in the presence of gastrointestinal disorders: Opportunities to define shared mechanisms of symptom expression. Int J Eat Disord. 2021. Jun;54(6):995–1008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Harer KN, Baker J, Reister N, Collins K, Watts L, Phillips C, et al. Avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder in the adult gastroenterology population: An under-recognized diagnosis? Am J Gastroenterol. 2018. Oct;113:S247–8. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Harer KN, Jagielski CH, Riehl ME, Chey WD. Avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder among adult gastroenterology behavioral health patients: Demographic and clinical characteristics. Gastroenterology. 2019. May;156(6):S–53. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Burton Murray H, Kuo B, Eddy KT, Breithaupt L, Becker KR, Dreier MJ, et al. Disorders of gut–brain interaction common among outpatients with eating disorders including avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder. Int J Eat Disord. 2021. Jun;54(6):952–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cooper M, Collison AO, Collica SC, Pan I, Tamashiro KL, Redgrave GW, et al. Gastrointestinal symptomatology, diagnosis, and treatment history in patients with underweight avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder and anorexia nervosa: Impact on weight restoration in a meal-based behavioral treatment program. Int J Eat Disord. 2021. Jun;54(6):1055–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gibson D, Watters A, Mehler PS. The intersect of gastrointestinal symptoms and malnutrition associated with anorexia nervosa and avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder: Functional or pathophysiologic?—A systematic review. Int J Eat Disord. 2021. Jun;54(6):1019–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zickgraf HF, Loftus P, Gibbons B, Cohen LC, Hunt MG. “If I could survive without eating, it would be a huge relief”: Development and initial validation of the Fear of Food Questionnaire. Appetite. 2022. Feb;169:105808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zickgraf HF, Ellis JM. Initial validation of the Nine Item Avoidant/Restrictive Food Intake disorder screen (NIAS): A measure of three restrictive eating patterns. Appetite. 2018. Apr;123:32–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Burton Murray H, Dreier MJ, Zickgraf HF, Becker KR, Breithaupt L, Eddy KT, et al. Validation of the nine item ARFID screen subscales for distinguishing ARFID presentations and screening for ARFID. Int J Eat Disord. 2021. Oct;54(10):1782–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Burton Murray H, Staller K. When food moves from friend to foe: Why avoidant/restrictive food intake matters in Iiritable bowel syndrome. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021. Sep;S1542–3565(21):01031–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chey WD, Hashash JG, Manning L, Chang L. AGA Clinical Practice Update on the Role of Diet in Irritable Bowel Syndrome: Expert Review. Gastroenterology. 2022. May;162(6):1737–1745.e5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wiklund CA, Rania M, Kuja-Halkola R, Thornton LM, Bulik CM. Evaluating disorders of gut-brain interaction in eating disorders. Int J Eat Disord. 2021. Jun;54(6):925–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zickgraf HF, Lane-Loney S, Essayli JH, Ornstein RM. Further support for diagnostically meaningful ARFID symptom presentations in an adolescent medicine partial hospitalization program. Int J Eat Disord. 2019. Apr;52(4):402–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ljótsson B, Falk L, Vesterlund AW, Hedman E, Lindfors P, Rück C, et al. Internet-delivered exposure and mindfulness based therapy for irritable bowel syndrome – A randomized controlled trial. Behav Res Ther. 2010. Jun;48(6):531–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ljótsson B, Andersson E, Lindfors P, Lackner JM, Grönberg K, Molin K, et al. Prediction of symptomatic improvement after exposure-based treatment for irritable bowel syndrome. BMC Gastroenterol. 2013. Dec;13(1):160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bonnert M, Olén O, Bjureberg J, Lalouni M, Hedman-Lagerlöf E, Serlachius E, et al. The role of avoidance behavior in the treatment of adolescents with irritable bowel syndrome: A mediation analysis. Behav Res Ther. 2018. Jun;105:27–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kambanis PE, Kuhnle MC, Wons OB, Jo JH, Keshishian AC, Hauser K, et al. Prevalence and correlates of psychiatric comorbidities in children and adolescents with full and subthreshold avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder. Int J Eat Disord. 2020. Feb;53(2):256–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Norris ML, Spettigue W, Hammond NG, Katzman DK, Zucker N, Yelle K, et al. Building evidence for the use of descriptive subtypes in youth with avoidant restrictive food intake disorder. Int J Eat Disord. 2018. Feb;51(2):170–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zucker NL, LaVia MC, Craske MG, Foukal M, Harris AA, Datta N, et al. Feeling and body investigators (FBI): ARFID division—An acceptance-based interoceptive exposure treatment for children with ARFID. Int J Eat Disord. 2019. Apr;52(4):466–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Farzaei MH, Bahramsoltani R, Abdollahi M, Rahimi R. The role of visceral hypersensitivity in irritable bowel syndrome: Pharmacological targets and novel treatments. J Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2016. Oct 30;22(4):558–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Losa M, Manz SM, Schindler V, Savarino E, Pohl D. Increased visceral sensitivity, elevated anxiety, and depression levels in patients with functional esophageal disorders and non-erosive reflux disease. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2021. Sep;33(9). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Drossman DA. Functional gastrointestinal disorders: History, pathophysiology, clinical features, and rome IV. Gastroenterology. 2016. May;150(6):1262–1279.e2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Böhn L, Störsrud S, Törnblom H, Bengtsson U, Simrén M. Self-Reported Food-Related Gastrointestinal Symptoms in IBS Are Common and Associated With More Severe Symptoms and Reduced Quality of Life. Am J Gastroenterol. 2013. May;108(5):634–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Fritscher-Ravens A, Pflaum T, Mösinger M, Ruchay Z, Röcken C, Milla PJ, et al. Many Patients With Irritable Bowel Syndrome Have Atypical Food Allergies Not Associated With Immunoglobulin E. Gastroenterology. 2019. Jul;157(1):109–118.e5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Aguilera-Lizarraga J, Florens MV, Viola MF, Jain P, Decraecker L, Appeltans I, et al. Local immune response to food antigens drives meal-induced abdominal pain. Nature. 2021. Feb 4;590(7844):151–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Biesiekierski JR, Manning LP, Murray HB, Vlaeyen JWS, Ljótsson B, Oudenhove LV. Review article: exclude or expose? The paradox of conceptually opposite treatments for irritable bowel syndrome. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2022;56:592–605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Chun AB, Wald A. Colonic and anorectal function in constipated patients with anorexia nervosa. Am J Gastroenterol. 1997;92(10):1879–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kamal N, Chami T, Andersen A, Rosell FA, Schuster MM, Whitehead WE. Delayed gastrointestinal transit times in anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa. Gastroenterology. 1991. Nov;101(5):1320–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Benini L, Todesco T, Frulloni L, Dalle Grave R, Campagnola P, Agugiaro F, et al. Esophageal motility and symptoms in restricting and binge-eating/purging anorexia. Dig Liver Dis. 2010. Nov;42(11):767–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Tack J, Caenepeel P, Fischler B, Piessevaux H, Janssens J. Symptoms associated with hypersensitivity to gastric distention in functional dyspepsia. Gastroenterology. 2001. Sep;121(3):526–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Tack J, Jones MP, Karamanolis g., Coulie B, Dubois D. Symptom pattern and pathophysiological correlates of weight loss in tertiary-referred functional dyspepsia. Neurogastroenterol Motil [Internet]. 2009. Jan. Available from: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1365-2982.2008.01240.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Tack J, Piessevaux H, Coulie B, Caenepeel P, Janssens J. Role of impaired gastric accommodation to a meal in functional dyspepsia. Gastroenterology. 1998. Dec;115(6):1346–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kim DY, Murray JA, Stephens DA. Noninvasive measurement of gastric accommodation in patients with idiopathic nonulcer dyspepsia. 2001;96(11):7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Hasler WL. Gastroparesis: Symptoms, evaluation, and treatment. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2007. Sep;36(3):619–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Gearry R, Skidmore P, O’Brien L, Wilkinson T, Nanayakkara W. Efficacy of the low FODMAP diet for treating irritable bowel syndrome: The evidence to date. Clin Exp Gastroenterol. 2016. Jun;131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Marsh A, Eslick EM, Eslick GD. Does a diet low in FODMAPs reduce symptoms associated with functional gastrointestinal disorders? A comprehensive systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Nutr. 2016. Apr;55(3):897–906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Thomas JJ, Becker KR, Kuhnle MC, Jo JH, Harshman SG, Wons OB, et al. Cognitive-behavioral therapy for avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder: Feasibility, acceptability, and proof-of-concept for children and adolescents. Int J Eat Disord. 2020. Oct;53(10):1636–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Thomas JJ, Wons OB, Eddy KT. Cognitive–behavioral treatment of avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2018. Nov;31(6):425–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Thomas JJ, Becker KR, Breithaupt L, Burton Murray H, Jo JH, Kuhnle MC, et al. Cognitive-behavioral therapy for adults with avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder. J Behav Cogn Ther. 2021. Mar;31(1):47–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Academy for Eating Disorders. Eating disorders: A guide to medical care [Internet]. Reston, VA: Academy for Eating Disorders; 2021. Report No.: 4th. Available from: https://connectedchildhealth.files.wordpress.com/2021/10/eating-disorders-guide-to-medical-care.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 71.Burton Murray H, Staller K, Kuo B. Eating disorders: Understanding their symptoms, mechanisms, and relevance to gastrointestinal functional and motility disorders. In: Handbook of Gastrointestinal Motility and Functional Disorders. 2nd ed. Thorophare, NJ: SLACK Incorporated; In Press. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Lemly DC, Dreier MJ, Birnbaum S, Eddy KT, Thomas JJ. Caring for Adults With Eating Disorders in Primary Care. Prim Care Companion CNS Disord. 2022. Jan 6;24(1):39060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Bryant-Waugh R, Micali N, Cooke L, Lawson EA, Eddy KT, Thomas JJ. Development of the Pica, ARFID, and Rumination Disorder Interview, a multi-informant, semi-structured interview of feeding disorders across the lifespan: A pilot study for ages 10–22. Int J Eat Disord. 2019. Apr;52(4):378–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Mari A, Hosadurg D, Martin L, Zarate-Lopez N, Passananti V, Emmanuel A. Adherence with a low-FODMAP diet in irritable bowel syndrome: are eating disorders the missing link? Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019. Feb;31(2):178–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Chey WD, Keefer L, Whelan K, Gibson PR. Behavioral and diet therapies in integrated care for patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology. 2021. Jan;160(1):47–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Guadagnoli L, Mutlu EA, Doerfler B, Ibrahim A, Brenner D, Taft TH. Food-related quality of life in patients with inflammatory bowel disease and irritable bowel syndrome. Qual Life Res. 2019. Aug;28(8):2195–205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Kim BJ, Kuo B. Gastroparesis and functional dyspepsia: A blurring distinction of pathophysiology and treatment. J Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2019. Jan;25(1):27–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Trott N, Aziz I, Rej A, Surendran Sanders D. How patients with IBS use low FODMAP dietary information provided by general practitioners and gastroenterologists: A qualitative study. Nutrients. 2019. Jun 11;11(6):1313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Lacy BE, Pimentel M, Brenner DM, Chey WD, Keefer LA, Long MD, et al. ACG clinical guideline: Management of irritable bowel syndrome. Am J Gastroenterol. 2021. Jan;116(1):17–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Lenhart A, Ferch C, Shaw M, Chey WD. Use of dietary management in irritable bowel syndrome: Results of a survey of over 1500 united states gastroenterologists. J Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2018. Jul 30;24(3):437–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Murray HB, Doerfler B, Harer KN, Keefer L. Psychological Considerations in the Dietary Management of Patients With DGBI. Am J Gastroenterol. 2022. Jun;117(6):985–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Kamal A, Pimentel M. Influence of dietary restriction on irritable bowel syndrome. Am J Gastroenterol. 2019. Feb;114:212–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Dionne J, Ford AC, Yuan Y, Chey WD, Lacy BE, Saito YA, et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis evaluating the efficacy of a gluten-free diet and a low FODMAPS diet in treating symptoms of irritable bowel syndrome. Am J Gastroenterol. 2018. Sep;113(9):1290–300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Chumpitazi BP, Cope JL, Hollister EB, Tsai CM, McMeans AR, Luna RA, et al. Randomised clinical trial: Gut microbiome biomarkers are associated with clinical response to a low FODMAP diet in children with the irritable bowel syndrome. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2015. Aug;42(4):418–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Eswaran SL, Chey WD, Han-Markey T, Ball S, Jackson K. A randomized controlled trial comparing the low FODMAP diet vs. modified NICE guidelines in US adults with IBS-D. Am J Gastroenterol. 2016. Dec;111(12):1824–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Rej A, Sanders DS, Shaw CC, Buckle R, Trott N, Agrawal A, et al. Efficacy and acceptability of dietary therapies in non-constipated irritable bowel syndrome: A randomized trial of traditional dietary advice, the low FODMAP diet and the gluten-free diet. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022. Feb. Under Review. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Biesiekierski JR, Peters SL, Newnham ED, Rosella O, Muir JG, Gibson PR. No effects of gluten in patients with self-reported non-celiac gluten sensitivity after dietary reduction of fermentable, poorly absorbed, short-chain carbohydrate. Gastroenterology. 2013. Aug;145(2):320–328.e3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Parker TJ, Woolner JT, Prevost A, Tuffnell Q, Shorthouse M, Hunter JO. Irritable bowel syndrome: Is the search for lactose intolerance justified? Eur J Gastroenterol Hapatol. 2001;13:219–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Ockeloen LE, Deckers-Kocken JM. Short- and long-term effects of a lactose-restricted diet and probiotics in children with chronic abdominal pain: A retrospective study. Complement Ther Clin Pract. 2012. May;18(2):81–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Olausson EA, Störsrud S, Grundin H, Isaksson M, Attvall S, Simrén M. A Small Particle Size Diet Reduces Upper Gastrointestinal Symptoms in Patients With Diabetic Gastroparesis: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Am J Gastroenterol. 2014. Mar;109(3):375–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Duncanson K, Burns G, Pryor J, Keely S, Talley NJ. Mechanisms of food-induced symptom induction and dietary management in functional dyspepsia. Nutrients. 2021. Mar 28;13(4):1109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Duboc H, Latrache S, Nebunu N, Coffin B. The role of diet in functional dyspepsia management. Front Psychiatry. 2020. Feb 5;11:23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Whelan K, Martin LD, Staudacher HM, Lomer MCE. The low FODMAP diet in the management of irritable bowel syndrome: an evidence-based review of FODMAP restriction, reintroduction and personalisation in clinical practice. J Hum Nutr Diet. 2018. Apr;31(2):239–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Staudacher HM, Kurien M, Whelan K. Nutritional implications of dietary interventions for managing gastrointestinal disorders. Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 2018. Mar;34(2):105–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Staudacher HM, Ralph FSE, Irving PM, Whelan K, Lomer MCE. Nutrient Intake, Diet Quality, and Diet Diversity in Irritable Bowel Syndrome and the Impact of the Low FODMAP Diet. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2020. Apr;120(4):535–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Halmos EP, Gibson PR. Controversies and reality of the FODMAP diet for patients with irritable bowel syndrome. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019. Jul;34(7):1134–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Melchior C, Algera J, Colomier E, Törnblom H, Simrén M, Störsrud S. Food avoidance and restriction in irritable bowel syndrome: Relevance for symptoms, quality of life and nutrient intake. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021. Jul;S1542356521007151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Brewerton TD, D’Agostino M. Adjunctive use of olanzapine in the treatment of avoidant restrictive food intake disorder in children and adolescents in an eating disorders program. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2017. Dec;27(10):920–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Yin J, Song J, Lei Y, Xu X, Chen JDZ. Prokinetic effects of mirtazapine on gastrointestinal transit. Am J Physiol-Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2014. May 1;306(9):G796–801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Kumar N, Barai S, Gambhir S, Rastogi N. Effect of mirtazapine on gastric emptying in patients with cancer-associated anorexia. Indian J Palliat Care. 2017;23(3):335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Marella HK, Saleem N, Olden K. Mirtazapine for Refractory Gastroparesis. ACG Case Rep J. 2019. Oct;6(10):e00256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Brigham KS, Manzo LD, Eddy KT, Thomas JJ. Evaluation and treatment of avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder (ARFID) in adolescents. Curr Pediatr Rep. 2018. Jun;6(2):107–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Dumont E, Jansen A, Kroes D, Haan E, Mulkens S. A new cognitive behavior therapy for adolescents with avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder in a day treatment setting: A clinical case series. Int J Eat Disord. 2019. Apr;52(4):447–58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Lock J, Robinson A, Sadeh-Sharvit S, Rosania K, Osipov L, Kirz N, et al. Applying family-based treatment (FBT) to three clinical presentations of avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder: Similarities and differences from FBT for anorexia nervosa. Int J Eat Disord. 2019. Apr;52(4):439–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Shimshoni Y, Silverman WK, Lebowitz ER. SPACE-ARFID: A pilot trial of a novel parent-based treatment for avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder. Int J Eat Disord. 2020. Oct;53(10):1623–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Weeks I, Becker KR, Ljótsson B, Staller K, Thomas JJ, Kuo B, et al. Brief cognitive behavioral treatment is a promising approach for avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder in the context of disorders of gut-brain interaction. :4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Thomas JJ, Eddy KT. Cognitive-behavioral therapy for avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder: children, adolescents, and adults. Cambridge University Press; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 108.Keefer L, Ballou SK, Drossman DA, Ringstrom G, Elsenbruch S, Ljótsson B. A rome working team report on brain-gut behavior therapies for disorders of gut-brain interaction. Gastroenterology. 2022. Jan;162(1):300–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Hunt MG, Moshier S, Milonova M. Brief cognitive-behavioral internet therapy for irritable bowel syndrome. Behav Res Ther. 2009. Sep;47(9):797–802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Shimshoni Y, Lebowitz ER. Childhood avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder: Review of treatments and a novel parent-based approach. J Cogn Psychother. 2020. Aug 1;34(3):200–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). Irritable bowel syndrome in adults: diagnosis and management. 3rd ed. London: National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE); 2017. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Tuck CJ, Reed DE, Muir JG, Vanner SJ. Implementation of the low FODMAP diet in functional gastrointestinal symptoms: A real-world experience. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2020. Jan;32(1). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Bellini M, Tonarelli S, Nagy A, Pancetti A, Costa F, Ricchiuti A, et al. Low FODMAP diet: Evidence, doubts, and hopes. Nutrients. 2020. Jan 4;12(1):148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Drossman DA, Tack J, Ford AC, Szigethy E, Törnblom H, Van Oudenhove L. Neuromodulators for Functional Gastrointestinal Disorders (Disorders of Gut−Brain Interaction): A Rome Foundation Working Team Report. Gastroenterology. 2018. Mar;154(4):1140–1171.e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Wauters L, Tito RY, Ceulemans M, Lambaerts M, Accarie A, Rymenans L, et al. Duodenal Dysbiosis and Relation to the Efficacy of Proton Pump Inhibitors in Functional Dyspepsia. Int J Mol Sci. 2021. Dec 19;22(24):13609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Tack J, Ly HG, Carbone F, Vanheel H, Vanuytsel T, Holvoet L, et al. Efficacy of Mirtazapine in Patients With Functional Dyspepsia and Weight Loss. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016. Mar;14(3):385–392.e4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]