Abstract

Introduction

The cohort study aimed to assess the association of nighttime sleep duration and the change in nighttime sleep duration with chronic kidney disease (CKD) and whether the association between nighttime sleep duration and CKD differed by daytime napping.

Methods

This study included 11,677 individuals from the China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study (CHARLS) and used data from the 2011 baseline survey and four follow-up waves. Nighttime sleep duration was divided into three groups: short (<7 h per night), optimal (7–9 h), and long nighttime sleep duration (>9 h). Daytime napping was divided into two groups: no nap and with a nap. We used Cox proportional hazards model to examine the effect of nighttime sleep duration at baseline and change in nighttime sleep duration on incident CKD and a joint effect of nighttime sleep duration and nap time on onset CKD.

Results

With a follow-up of 7 years, the incidence of CKD among those with short, optimal, and long nighttime sleep duration was 9.89, 6.75, and 9.05 per 1,000 person-years, respectively. Compared to individuals with optimal nighttime sleep duration, short nighttime sleepers had a 44% higher risk of onset CKD (hazard ratio [HR]: 1.44, 95% confidence interval [CI]: 1.21–1.72). Compared to participants with persistent optimal nighttime sleep duration, those with persistent short or long nighttime sleep duration had an increased risk of incident CKD (HR: 1.44, 95% CI: 1.15–1.80). We found a lower incidence of CKD in participants with short nighttime sleep duration and a nap (HR: 0.74, 95% CI: 0.60–0.93), compared to those with short nighttime sleep duration and no nap.

Conclusion

Short nighttime sleep duration and persistent long or short nighttime sleep duration were associated with a higher risk of onset CKD. Keeping persistent optimal nighttime sleep duration may help reduce CKD risk later in life. Daytime napping may be protective against CKD incidence.

Keywords: Nighttime sleep duration, Change in nighttime sleep duration, Daytime napping, Chronic kidney disease

Introduction

Chronic kidney disease (CKD) requires more attention [1]. Since 1990, the morbidity of CKD has increased sharply worldwide, and the global CKD mortality has increased by about 50% [2]. In addition, patients with CKD face high cost renal treatment and are more prone to other health problems, such as cardiovascular diseases and diabetes, and all-cause mortality [3, 4]. Identifying the modifiable risk behaviors of CKD contributes to early prevention and intervention of CKD to curb severe health damage [5].

Adequate nighttime sleep is essential for maintaining good health; nearly 20% of adults suffer from sleep disorders [6, 7]. Increasing evidence has demonstrated that sleep disturbance had a strong connection with the onset of CKD, but results were inconsistent [8–11]. Several studies have shown that short [8, 9] and long nighttime sleep duration [10, 11] had adverse effects on the incidence of CKD. Short and long nighttime sleep duration may give rise to sympathetic overreaction, metabolic disorders, and diurnal rhythm disturbances, leading to CKD onset [12–15]. In addition, there is evidence of sex differences in the incidence and progression of CKD [16–18]. However, fewer studies explored sex differences in the effect of nocturnal sleep duration on CKD [19]. Notably, decreased or increased nighttime sleep duration may result in severe health issues, such as diabetes [20], cognitive damage [21], and increased premature mortality [22]. However, no studies assessed the effect of nighttime sleep duration change on the onset of CKD. Evidence suggested that daytime napping would influence the association between nighttime sleep duration and chronic diseases [23, 24]. An Israeli study observed that a nap in daylight could reduce the risk of death among older people who sleep less at night [23]. A Chinese study found optimal nighttime sleepers with more than 1 h of daytime napping had an increased risk of incident diabetes, compared with optimal nighttime sleepers without daytime napping [24]. However, the joint effect of nap time and nocturnal sleep time on CKD has not been explored. We hypothesized that too short or too long nighttime sleep duration and change in nighttime sleep duration would increase the risk of incident CKD. Furthermore, the association between sleep duration and CKD may be sex-specific. Daytime napping would reduce the impact of short nocturnal sleep duration.

Our longitudinal study aimed to assess the effect of nighttime sleep duration at baseline and change in nighttime sleep duration on incident CKD among the middle-aged and elderly populations. We also examined whether the association of nighttime sleep duration with CKD might be sex-specific and whether napping prevalence could influence the effect of nighttime sleep duration on the onset of CKD.

Materials and Methods

Participants

We used data from the China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study (CHARLS), a prospective national cohort study covering dwellers from 28 provinces in China. The specific contents of this investigation have been announced previously [25]. Among the 17,705 participants enrolled in the 2011 baseline survey (online suppl. Fig. 1; for all online suppl. material, see https://doi.org/10.1159/000531261), we excluded those without data of health status (N = 109), those who aged less than 45 years old at baseline (N = 369), those without information of nighttime sleep duration or CKD condition (N = 1,607), those without complete data of relative covariates (N = 2,910), and those who had CKD at baseline (N = 1,033). We selected 11,677 eligible individuals in the baseline analytic sample of nighttime sleep duration. Among the 11,677 individuals, we selected a sub-sample (N = 9,993) with complete nighttime sleep duration data at the three follow-up waves to create a polytomous variable “change in nighttime sleep duration” that expresses whether participants remained the same or transitioned into the other nighttime sleep duration groups. The average time to follow-up for the sub-sample of nighttime sleep duration change was 6.21 years. Follow-up of these participants began in December 2011 and ended at the time of the first diagnosis of CKD, or December 2018, whichever came first.

Exposure

Nighttime sleep duration was measured in the four waves of CHARLS with a question: “During the past month, how many hours of actual sleep did you get at night?” Many epidemiological studies suggest that sleeping 7–9 h at night most benefits adults [26, 27]. We followed the same approach as previous studies [28] to classify nighttime sleep duration into three groups according to average time at night: optimal nighttime sleep duration (7–9 h per night), short nighttime sleep duration (<7 h per night), and long nighttime sleep duration (>9 h per night).

We defined change in nighttime sleep duration according to the level of nocturnal sleep time at baseline and nocturnal sleep time at the time of CKD diagnosis or the last follow-up, whichever came first. Therefore, we divided change in nighttime sleep duration into four groups: persistent optimal nighttime sleep, persistent short or long nighttime sleep, optimal to short or long nighttime sleep, and short or long to optimal nighttime sleep.

Daytime napping was measured with a question: “During the past month, how long did you take a nap after lunch?” Daytime naps were divided into two categories: no nap and with a nap.

Chronic Kidney Disease

CKD status was documented by a question at the baseline survey and the three follow-up waves: “Have you been diagnosed with kidney disease (except for tumor and cancer) by a doctor?” If participants answered yes, they would be classified as having CKD and asked about the time of diagnosis.

Covariates

Possible covariates were collected at baseline by physical examination or self-reported questionnaires and included age at baseline (middle-aged adults: 45–60 years old; old adults: ≥60 years old), sex, marital conditions (married or cohabitated, divorced or separated, and widowed or never married), education (illiteracy, elementary school, secondary school, as well as university or above), residence, smoking (non-smokers, current smokers), and drinking conditions (never drinking, drinking less than once a month, and drinking more than once a month), body mass index (BMI), chronic disease conditions, and daytime napping. BMI was divided into four groups based on the criterion applicable to Chinese adults: underweight, normal weight, overweight, and obese [29]. Non-smokers were those who never smoked, ex-smokers were those who had quitted smoking, and current smokers were smoking at baseline. Chronic diseases, diagnosed by clinicians before participating in the survey, included hypertension, dyslipidemia, stroke, diabetes, and heart diseases.

Statistical Analysis

We computed mean ± standard deviation and N (%) to characterize continuous and categorical variables at baseline, respectively. We used ANOVA and Kruskal-Wallis test to compare the continuous variables normally distributed and nonnormally distributed, respectively. Categorical variables were compared using χ2 test. Cox proportional hazards model was used to estimate the effects of nighttime sleep duration and change in nighttime sleep duration on incident CKD. The potential non-linear relationship between nocturnal sleep time and CKD incidence was estimated by restricted cubic spline curve with four knots. We conducted the subgroup analyses according to age and sex, respectively. Finally, we assessed the effect of daytime naps on the link between nocturnal sleep duration and CKD. We performed a string of sensitivity analyses: (1) we evaluated the influence of unmeasured confounding [30] to examine the robustness of our main results; (2) we examined whether the association was modified by chronic disease status and residence; (3) we excluded participants who developed CKD within 1 year of follow-up to avoid reverse causality; (4) we examined whether our results would be altered when age and BMI were treated as continuous variables. All above analyses were performed using Stata 15 and R software. All tests were significant at p value <0.05.

Results

Table 1 denoted the baseline characteristics of adults among nighttime sleep duration categories. Of the 11,677 individuals, 52.7% were women, and 30.3% had one or more chronic diseases. 46.1% of participants, in the final analysis, reported optimal nighttime sleep duration, while 49.7% and 4.2% of the individuals had short and long nighttime sleep duration, respectively. The average daytime nap length was 29.3, 36.0, and 45.0 min in short, optimal, and long nighttime sleep duration, respectively. Compared to individuals sleeping 7–9 h at night, those sleeping less than 7 h tended to be women, older, and had a higher prevalence of chronic diseases.

Table 1.

The baseline characteristics of different nighttime sleep duration groups

| Characteristics | Nighttime sleep duration | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| short (<7 h) | optimal (7–9 h) | long (>9 h) | p value | |

| N (%) | 5,802 (49.7) | 5,382 (46.1) | 493 (4.2) | |

| Gender, N (%) | ||||

| Male | 2,624 (45.2) | 2,656 (49.4) | 240 (48.7) | <0.001 |

| Female | 3,178 (54.8) | 2,726 (50.7) | 253 (51.3) | |

| Age, N (%) | ||||

| [45, 60] | 2,972 (51.2) | 3,180 (59.1) | 261 (52.9) | <0.001 |

| ≥60 | 2,830 (48.7) | 2,202 (40.9) | 232 (47.1) | |

| Education level, N (%) | ||||

| Illiteracy | 1,741 (30.0) | 1,362 (25.3) | 175 (35.5) | <0.001 |

| Elementary school | 2,404 (41.43) | 2,113 (39.3) | 210 (42.6) | |

| Secondary school | 1,574 (27.1) | 1,777 (33.0) | 106 (21.5) | |

| University or above | 83 (2.4) | 130 (2.4) | 2 (0.4) | |

| Marital status, N (%) | ||||

| Married or cohabitated | 4,960 (85.5) | 4,812 (89.4) | 408 (82.7) | <0.001 |

| Divorced or separated | 80 (1.4) | 50 (0.9) | 12 (2.4) | |

| Widowed or never married | 762 (13.1) | 520 (9.7) | 73 (14.8) | |

| Residence, N (%) | ||||

| Urban | 2,157 (37.2) | 2,061 (38.3) | 138 (28.0) | 0.002 |

| Rural | 3,645 (62.8) | 3,321 (61.7) | 355 (72.0) | |

| BMI (mean ± SD, kg/m2) | 23.4±3.9 | 23.8±4.0 | 23.3±3.9 | <0.001 |

| Smoking status, N (%) | ||||

| Non-smoker | 3,551 (61.2) | 3,185 (59.2) | 299 (60.7) | 0.099 |

| Ex-smoker | 503 (8.7) | 480 (8.9) | 45 (9.1) | |

| Current smoker | 1,748 (30.1) | 1,717 (31.9) | 149 (30.2) | |

| Drinking status, N (%) | ||||

| Never | 1,431 (24.7) | 1,368 (25.4) | 127 (25.8) | 0.416 |

| Less than once a month | 447 (7.7) | 427 (7.9) | 44 (8.9) | |

| More than once a month | 3,924 (67.6) | 3,587 (66.7) | 322 (65.3) | |

| Chronic disease, N (%) | ||||

| Yes | 1,838 (31.7) | 1,554 (28.9) | 144 (29.2) | 0.002 |

| No | 3,964 (68.3) | 3,828 (71.1) | 349 (70.8) | |

| Daytime napping, N (%) | ||||

| No nap | 2,886 (49.7) | 2,331 (43.3) | 204 (41.4) | <0.001 |

| With a nap | 2,916 (50.3) | 3,051 (56.7) | 289 (58.6) | |

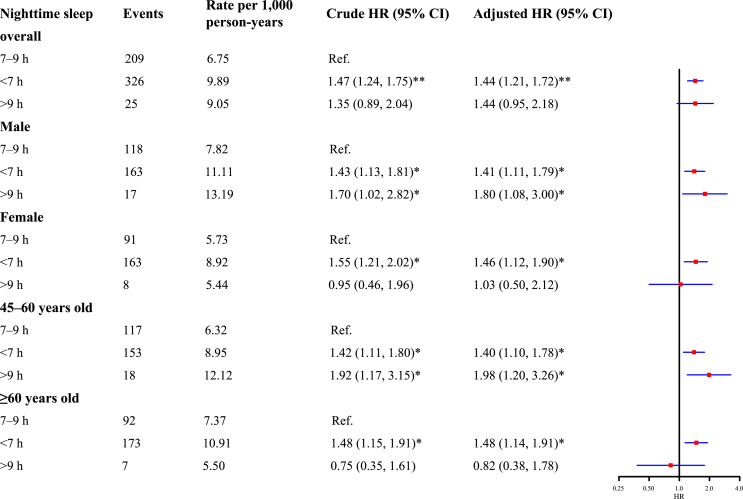

Nighttime sleep duration on a continuous level had a U-shaped association with the onset of CKD after adjusting for covariates (online suppl. Fig. 2). Approximately 7–8 h of nighttime sleep duration may have a protective effect on CKD incidence. The risk of incident CKD tended to be higher with decreasing nighttime sleep duration. Increased risks of CKD incidence were observed among individuals with short (hazard ratio [HR]: 1.44, 95% confidence interval [CI]: 1.21–1.72) and long nighttime sleep duration (HR: 1.44, 95% CI: 0.95–2.18) compared to individuals with optimal nighttime sleep duration (Fig. 1). The associations between short nighttime sleep duration and risk of onset CKD remained irrespective of sex and age at baseline. However, a higher risk of CKD incidence attributed to long nighttime sleep duration was only observed in male participants (HR: 1.80, 95% CI: 1.08–3.00) and middle-aged participants (HR: 1.98, 95% CI: 1.20–3.26) (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

The association between nighttime sleep duration at baseline and incident CKD. *p value <0.05; **p value <0.001. The adjusted model was adjusted for age, gender, BMI, education level, marital status, smoking and drinking status, residence, chronic diseases, and daytime napping.

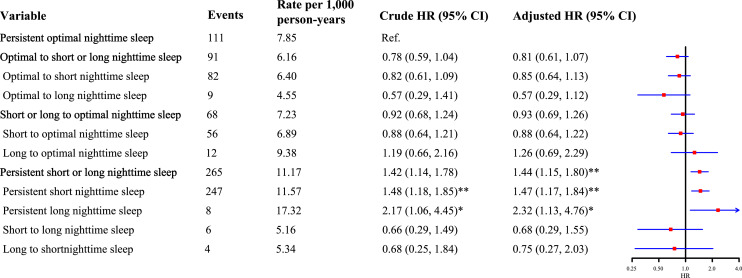

The incidence of CKD in persistent optimal nighttime sleep duration group, optimal to short or long nighttime sleep duration group, short or long to optimal nighttime sleep duration group, and persistent short or long nighttime sleep duration group was 7.85, 6.16, 7.23, and 11.17 per 1,000 person-years, respectively. Compared to individuals with persistent optimal nighttime sleep duration, participants with persistent short or long nighttime sleep duration had an increased risk of incident CKD (HR: 1.44, 95% CI: 1.15–1.80), while individuals with changed level of nighttime sleep duration were not significantly associated with incident CKD (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

The association between change in nighttime sleep duration and incident CKD. *p value <0.05; **p value <0.001. The adjusted model was adjusted for age, gender, BMI, education level, marital status, smoking and drinking status, residence, chronic diseases, and daytime napping.

Table 2 demonstrated the joint effect of nightly sleep time and daytime naps. In comparison with short nighttime sleepers with no nap at baseline, those with short nighttime sleep duration and a nap had a lower risk of onset CKD (HR: 0.74, 95% CI: 0.60–0.93). Moreover, those with optimal nighttime sleep duration and a nap had the lowest risk of incident CKD (HR: 0.55, 95% CI: 0.43–0.70).

Table 2.

The joint effect of nighttime sleep duration and daytime napping on incident CKD

| Nighttime sleep duration, h | Daytime napping | Events | Rate per 1,000 person-years | Crude HR (95% CI) | Adjusted HR (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| <7 | No nap | 177 | 10.77 | Ref | |

| <7 | With a nap | 149 | 9.02 | 0.83 (0.67, 1.04) | 0.74 (0.60, 0.93)** |

| 7–9 | No nap | 93 | 6.89 | 0.64 (0.50, 0.82)** | 0.64 (0.50, 0.82)** |

| 7–9 | With a nap | 116 | 6.63 | 0.62 (0.49, 0.78)** | 0.55 (0.43, 0.70)** |

| >9 | No nap | 10 | 8.60 | 0.79 (0.42, 1.49) | 0.83 (0.44, 1.58) |

| >9 | With a nap | 15 | 9.47 | 0.88 (0.52, 1.49) | 0.80 (0.47, 1.36) |

Adjusted model adjusts for age, gender, BMI, education level, marital status, smoking and drinking status, residence, chronic diseases.

**p value <0.001.

We conducted sensitivity analyses to examine the influence of unmeasured confounding on the main results. Even if the unmeasured confounding factors were sufficient to increase the likelihood of nighttime sleep duration and CKD onset by 1.8-fold, we still observed the increased risk of CKD associated with short nighttime sleep duration at baseline and persistent short or long nighttime sleep duration (online suppl. Tables 1, 2). Analyses stratified by chronic disease status and residence showed that short nighttime sleepers had a higher risk of CKD (with chronic disease [HR = 1.59, 95% CI: 1.22–2.09]; no chronic disease [HR = 1.37, 95% CI: 1.09–1.73]; urban [HR = 1.36, 95% CI: 1.03–1.81]; rural [HR = 1.49, 95% CI: 1.19–1.87]) (online suppl. Table 3). The results of analysis excluded individuals who were diagnosed with CKD within 1 year were similar to those from the main analysis (online suppl. Table 4). The associations between nighttime sleep duration and CKD remained unchanged when age and BMI were treated as continuous variables (online suppl. Tables 5–7).

Discussion

In our study, we observed short nighttime sleep duration at baseline would increase the risk of incident CKD. Decreased or increased nighttime sleep duration had no association with incident CKD, but long-term short or long nighttime sleep duration was linked to increased risk of incident CKD. Short nighttime sleepers with a nap in daylight had a lower risk of the onset of CKD, and individuals with optimal nighttime sleep duration and a nap had the lowest risk of CKD, compared with short nighttime sleepers without daytime naps.

The average hours of sleep at night impacted CKD incidence [8–11, 31]. The literature based on the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey has shown that sleeping <5 h at night could increase the estimated glomerular filtration rate [9]. A cohort study of >3,000 workers in Japan has indicated that shift workers sleeping <5 h per night had an increased risk of CKD [8]. These studies lend support to our findings that short nighttime sleep duration had a significant association with CKD risk. However, another Japanese study, including subjects who underwent health checks at a hospital, indicated that in comparison to individuals with optimal nighttime sleep duration, those with less than 6 h of sleep per night had a lower risk of CKD [31]. The impact of nighttime sleep duration on CKD is mixed [32], which may be the reason for the different results from our study. The inconsistent results regarding long nighttime sleep duration were also observed. A cross-sectional study has indicated that people with long (≥8 h/night) nighttime sleep duration had a higher prevalence of CKD [10]. A large cohort study in the Chinese population has demonstrated that long nighttime sleep duration (>8 h/night) had a higher risk of incident CKD [11]. There are some reasons for the inconsistency. On the one hand, compared with those previous studies [10, 11], the average nighttime sleep duration of individuals in our study was shorter, which may reduce the influence of long nighttime sleep duration on incident CKD. On the other hand, fewer individuals slept more than 9 h at night in our study population.

In the subgroup analysis, we found that long nighttime sleep duration had an association with the risk of incident CKD among middle-aged or male participants. A previous study in Korea has suggested that long nighttime sleep duration had a more significant effect on the onset of CKD in males than in females [19], which was consistent with our findings. Further studies are needed to explore whether the relationship between nighttime sleep duration and CKD is sex-specific. With respect to the impact of age on the association between nighttime sleep duration and health, the literature from the Swedish Cancer Society has indicated that the association between long nighttime sleep duration and all-cause mortality was most pronounced among young adults, reducing with age, but not among those over 65 years old [33]. Although the outcomes were different, both our study and the Swedish study suggested that the relationship between nighttime sleep duration and CKD was age-specific.

Currently, the mechanisms underlying the relationship between nighttime sleep duration and CKD are still under exploration. Some studies suggested that most renal physiological processes, such as the renin-angiotensin system and renal blood flow, follow a circadian rhythm, and some transcriptions of the genes in the kidney, like ribosomal protein L23 and lactate dehydrogenase B, were also diurnal [34–36]. Furthermore, lack of nighttime sleep duration may result in overactivation of the renal sympathetic nervous system and lead to CKD [12]. Previous studies have suggested that sleep disorders could promote systemic inflammation, leading to the risk of CKD [37–39].

For the first time, we found adhering to short or long nighttime sleep duration rather than an increase or decrease in nighttime sleep duration had an association with the onset of CKD. Although our exposure and outcome are self-reported, our findings are conducive to developing CKD prevention strategies, given the sufficient follow-up period. The results of animal studies have shown long-term lack of sleep can increase interleukin-6 and C-reactive protein [40, 41]. Furthermore, weakening the autoimmune barrier can damage renal function [39]. A human study on nighttime sleep duration and type 2 diabetes has shown that persistent short nighttime sleep duration over 5 years exposure period was linked to a higher risk of type 2 diabetes, compared with optimal sleep duration per night [20]. Type 2 diabetes may induce CKD [42], and in our analysis, we controlled diabetes status. The association between persistent short nighttime sleep duration and CKD was still apparent, which indicated that persistent short nighttime sleep duration was an independent risk factor for CKD. Regarding the effect of persistent long nighttime sleep duration on CKD, one explanation is that long nighttime sleep duration may be a marker of poor sleep quality, leading to decreased kidney function [43, 44]. Existing studies about sleep and CKD rarely mention the relationship between change in nighttime sleep duration and risk of CKD [8–10, 19], so the mechanisms of the potential effect of change in nighttime sleep duration on the onset of CKD remain to be elucidated.

In addition, we observed a lower risk of CKD in short nighttime sleepers with a nap in the daytime, compared with short nighttime sleepers without a nap. The literature has defined habitual short sleep duration with significant daytime impairment as insomnia [45]. Insomnia can cause hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal regulatory system disorders [46]. Another study showed that sleep restriction was associated with increased urinary norepinephrine levels [47], subsequently leading to constricting renal vasoconstriction and renal damage [48]. Daytime napping may compensate for lack of nighttime sleep duration [24], thereby obtaining enough sleep duration in an entire circadian cycle to reduce the risk of CKD. In addition, sleep restriction with regular napping attenuates urinary norepinephrine, which may reduce risk for sympathoexcitation-mediated renal damage [47]. Meanwhile, we found individuals with optimal sleep duration and a nap had the lowest risk of CKD. A previous study has indicated participants who slept 7–8 h at night and took a nap during the day had a lower risk of stroke than short nighttime sleepers without a nap [49], similar to our results. However, a previous study has shown the glomerular filtration rate decreased significantly with the increase of daytime napping [50], contradicting our results, possibly because the study population was patients with diabetes, which was different from our study population. The joint effect of daytime napping and nighttime sleep duration on CKD needs more research to support.

Our study had the following strengths: a large study population, detailed demographic and health status, and prospective design. However, some limitations need to be mentioned. First, the exposure and outcome measures in our study were self-reported by participants and were subject to recall bias, which may contribute to misclassification bias. Although studies have suggested that subjectively reported sleep duration was consistent with objectively monitored sleep duration [51], further studies using polysomnography or sleep diaries to monitor sleep duration are still needed. Second, measures of sleep fragmentation and sleep disturbance were not included in the questionnaire of CHARLS, which may attenuate the influence of nighttime sleep on CKD. Some evidence indicated that poor sleep quality may impair kidney function [44], and people with CKD also frequently experience sleep apnea [52]. However, the sensitivity analyses of unmeasured confounding denoted moderate confounder could not explain away our results. Third, we did not collect CKD staging in the present questionnaire. However, nighttime sleep duration may have an effect on CKD progression [53, 54]. Further studies are needed to explore the association between nighttime sleep duration and CKD staging. Finally, although we have performed subgroup analyses and controlled for potential confounders, the study was observational in nature, and we cannot exclude undermeasured confounders such as chronic disease status and education level, resulting in the possibility of residual confounding.

In conclusion, we found that sleeping less than 7 h per night and persistent short or long nighttime sleep duration had obvious associations with CKD incidence in Chinese adults. Daytime napping may be protective against CKD. Our study indicated that long-term nighttime sleep of 7–9 h might prevent CKD in Chinese middle-aged older adults.

Statement of Ethics

Ethical approval and consent were not required as this study was based on publicly available data.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors have no conflicts of interest.

Funding Sources

This study was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grants No. 82173612 and 82273730); Shanghai Rising-Star Program (21QA1401300); Shanghai Municipal Natural Science Foundation (22ZR1414900); Shanghai Municipal Science and Technology Major Project (ZD2021CY001).

Author Contributions

Bingxin Jiang wrote the manuscript and analyzed data. Dongxu Tang and Neng Dai contributed to study design and data analysis. Chen Huang, Yahang Liu, Ce Wang, Jiahuan Peng, Guoyou Qin, Yongfu Yu, and Jiaohua Chen provided critical suggestions for revising the manuscript.

Funding Statement

This study was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grants No. 82173612 and 82273730); Shanghai Rising-Star Program (21QA1401300); Shanghai Municipal Natural Science Foundation (22ZR1414900); Shanghai Municipal Science and Technology Major Project (ZD2021CY001).

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are openly available in CHARLS datasets at https://charls.charlsdata.com. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Material

References

- 1. GBD Chronic Kidney Disease Collaboration, Purcell CA, Levey AS, Smith M, Abdoli A, Abebe M, et al. Global, regional, and national burden of chronic kidney disease, 1990–2017: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet. 2020;395(10225):709–33. 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30045-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Cockwell P, Fisher L-A. The global burden of chronic kidney disease. Lancet. 2020;395(10225):662–4. 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)32977-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Jha V, Garcia-Garcia G, Iseki K, Li Z, Naicker S, Plattner B, et al. Chronic kidney disease: global dimension and perspectives. Lancet. 2013;382(9888):260–72. 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60687-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Couser WG, Remuzzi G, Mendis S, Tonelli M. The contribution of chronic kidney disease to the global burden of major noncommunicable diseases. Kidney Int. 2011;80(12):1258–70. 10.1038/ki.2011.368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Kelly JT, Su G, Zhang L, Qin X, Marshall S, González-Ortiz A, et al. Modifiable lifestyle factors for primary prevention of CKD: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2021;32(1):239–53. 10.1681/ASN.2020030384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Drake C, Kryger M, Phillips B. Sleep in America poll: summary of findings. Washington (DC): Nation Sleep Found; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Doi Y, Minowa M, Okawa M, Uchiyama M. Prevalence of sleep disturbance and hypnotic medication use in relation to sociodemographic factors in the general Japanese adult population. J Epidemiol. 2000;10(2):79–86. 10.2188/jea.10.79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Sasaki S, Yoshioka E, Saijo Y, Kita T, Tamakoshi A, Kishi R. Short sleep duration increases the risk of chronic kidney disease in shift workers. J Occup Environ Med. 2014;56(12):1243–8. 10.1097/JOM.0000000000000322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Petrov ME, Buman MP, Unruh ML, Baldwin CM, Jeong M, Reynaga-Ornelas L, et al. Association of sleep duration with kidney function and albuminuria: NHANES 2009–2012. Sleep Health. 2016;2(1):75–81. 10.1016/j.sleh.2015.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Salifu I, Tedla F, Pandey A, Ayoub I, Brown C, McFarlane SI, et al. Sleep duration and chronic kidney disease: analysis of the national health interview survey. Cardiorenal Med. 2014;4(3–4):210–6. 10.1159/000368205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Bo Y, Yeoh EK, Guo C, Zhang Z, Tam T, Chan T-C, et al. Sleep and the risk of chronic kidney disease: a cohort study. J Clin Sleep Med. 2019;15(3):393–400. 10.5664/jcsm.7660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Vink EE, de Jager RL, Blankestijn PJ. Sympathetic hyperactivity in chronic kidney disease: pathophysiology and (new) treatment options. Curr Hypertens Rep. 2013;15(2):95–101. 10.1007/s11906-013-0328-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Knutson KL, Lash J, Ricardo AC, Herdegen J, Thornton JD, Rahman M, et al. Habitual sleep and kidney function in chronic kidney disease: the chronic renal insufficiency cohort study. J Sleep Res. 2018;27(2):281–9. 10.1111/jsr.12573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Grandner M, Mullington JM, Hashmi SD, Redeker NS, Watson NF, Morgenthaler TI. Sleep duration and hypertension: analysis of >700,000 adults by age and sex. J Clin Sleep Med. 2018;14(6):1031–9. 10.5664/jcsm.7176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Brady E, Bodicoat D, Hall A, Khunti K, Yates T, Edwardson C, et al. Sleep duration, obesity and insulin resistance in a multi-ethnic UK population at high risk of diabetes. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2018;139:195–202. 10.1016/j.diabres.2018.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Gilg J, Castledine C, Fogarty D. Chapter 1 UK RRT incidence in 2010: national and centre-specific analyses. Nephron Clin Pract. 2012;120(Suppl 1):c1–27. 10.1159/000342843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Carrero JJ, Hecking M, Chesnaye NC, Jager KJ. Sex and gender disparities in the epidemiology and outcomes of chronic kidney disease. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2018;14(3):151–64. 10.1038/nrneph.2017.181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Ricardo AC, Yang W, Sha D, Appel LJ, Chen J, Krousel-Wood M, et al. Sex-related disparities in CKD progression. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2019;30(1):137–46. 10.1681/ASN.2018030296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Kim C-W, Chang Y, Sung E, Yun KE, Jung H-S, Ko B-J, et al. Sleep duration and quality in relation to chronic kidney disease and glomerular hyperfiltration in healthy men and women. PLoS One. 2017;12(4):e0175298. 10.1371/journal.pone.0175298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Ferrie JE, Kivimäki M, Akbaraly TN, Tabak A, Abell J, Davey Smith G, et al. Change in sleep duration and type 2 diabetes: the Whitehall II study. Diabetes Care. 2015;38(8):1467–72. 10.2337/dc15-0186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Ferrie JE, Shipley MJ, Akbaraly TN, Marmot MG, Kivimäki M, Singh-Manoux A. Change in sleep duration and cognitive function: findings from the Whitehall II Study. Sleep. 2011;34(5):565–73. 10.1093/sleep/34.5.565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Ferrie JE, Shipley MJ, Cappuccio FP, Brunner E, Miller MA, Kumari M, et al. A prospective study of change in sleep duration: associations with mortality in the Whitehall II cohort. Sleep. 2007;30(12):1659–66. 10.1093/sleep/30.12.1659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Cohen-Mansfield J, Perach R. Sleep duration, nap habits, and mortality in older persons. Sleep. 2012;35(7):1003–9. 10.5665/sleep.1970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Lin L, Lu C, Chen W, Guo VY. Daytime napping and nighttime sleep duration with incident diabetes mellitus: a cohort study in Chinese older adults. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(9):5012. 10.3390/ijerph18095012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Zhao Y, Hu Y, Smith JP, Strauss J, Yang G. Cohort profile: the China health and retirement longitudinal study (CHARLS). Int J Epidemiol. 2014;43(1):61–8. 10.1093/ije/dys203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Hirshkowitz M, Whiton K, Albert SM, Alessi C, Bruni O, DonCarlos L, et al. National Sleep Foundation’s sleep time duration recommendations: methodology and results summary. Sleep health. 2015;1(1):40–3. 10.1016/j.sleh.2014.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. García-Perdomo H, Zapata-Copete J, Rojas-Cerón C. Sleep duration and risk of all-cause mortality: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Epidemiol Psychiatr Sci. 2019;28(5):578–88. 10.1017/S2045796018000379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Chaput JP, Bouchard C, Tremblay A. Change in sleep duration and visceral fat accumulation over 6 years in adults. Obesity. 2014;22(5):E9–12. 10.1002/oby.20701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Zhou B-F; Cooperative Meta-Analysis Group of the Working Group on Obesity in China . Predictive values of body mass index and waist circumference for risk factors of certain related diseases in Chinese adults: study on optimal cut-off points of body mass index and waist circumference in Chinese adults. Biomed Environ Sci. 2002;15(1):83–96. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Ding P, VanderWeele TJ. Sensitivity analysis without assumptions. Epidemiology. 2016;27(3):368–77. 10.1097/EDE.0000000000000457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Nakajima H, Hashimoto Y, Okamura T, Obora A, Kojima T, Hamaguchi M, et al. Association between sleep duration and incident chronic kidney disease: a population-based cohort analysis of the NAGALA Study. Kidney Blood Press Res. 2020;45(2):339–49. 10.1159/000504545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development . OECD Gender Data Portal [Internet]. 2019. [Available from: https://www.oecd.org/gender/data/OECD_1564_TUSupdatePortal.xlsx.

- 33. Åkerstedt T, Ghilotti F, Grotta A, Bellavia A, Lagerros YT, Bellocco R. Sleep duration, mortality and the influence of age. Eur J Epidemiol. 2017;32(10):881–91. 10.1007/s10654-017-0297-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Zuber AM, Centeno G, Pradervand S, Nikolaeva S, Maquelin L, Cardinaux L, et al. Molecular clock is involved in predictive circadian adjustment of renal function. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106(38):16523–8. 10.1073/pnas.0904890106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Nikolaeva S, Pradervand S, Centeno G, Zavadova V, Tokonami N, Maillard M, et al. The circadian clock modulates renal sodium handling. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2012;23(6):1019–26. 10.1681/ASN.2011080842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Tokonami N, Mordasini D, Pradervand S, Centeno G, Jouffe C, Maillard M, et al. Local renal circadian clocks control fluid: electrolyte homeostasis and BP. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2014;25(7):1430–9. 10.1681/ASN.2013060641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Ferrie JE, Kivimäki M, Akbaraly TN, Singh-Manoux A, Miller MA, Gimeno D, et al. Associations between change in sleep duration and inflammation: findings on C-reactive protein and interleukin 6 in the Whitehall II Study. Am J Epidemiol. 2013;178(6):956–61. 10.1093/aje/kwt072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Lee HW, Yoon HS, Yang JJ, Song M, Lee JK, Lee SA, et al. Association of sleep duration and quality with elevated hs-CRP among healthy Korean adults. PLoS One. 2020;15(8):e0238053. 10.1371/journal.pone.0238053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Cirillo P, Sautin YY, Kanellis J, Kang D-H, Gesualdo L, Nakagawa T, et al. Systemic inflammation, metabolic syndrome and progressive renal disease. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2009;24(5):1384–7. 10.1093/ndt/gfp038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Meier-Ewert HK, Ridker PM, Rifai N, Regan MM, Price NJ, Dinges DF, et al. Effect of sleep loss on C-reactive protein, an inflammatory marker of cardiovascular risk. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004;43(4):678–83. 10.1016/j.jacc.2003.07.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Vgontzas AN, Zoumakis E, Bixler EO, Lin H-M, Follett H, Kales A, et al. Adverse effects of modest sleep restriction on sleepiness, performance, and inflammatory cytokines. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2004;89(5):2119–26. 10.1210/jc.2003-031562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Reidy K, Kang HM, Hostetter T, Susztak K. Molecular mechanisms of diabetic kidney disease. J Clin Invest. 2014;124(6):2333–40. 10.1172/JCI72271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Grandner MA, Drummond SP. Who are the long sleepers? Towards an understanding of the mortality relationship. Sleep Med Rev. 2007;11(5):341–60. 10.1016/j.smrv.2007.03.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Ogna A, Forni Ogna V, Haba Rubio J, Tobback N, Andries D, Preisig M, et al. Sleep characteristics in early stages of chronic kidney disease in the HypnoLaus cohort. Sleep. 2016;39(4):945–53. 10.5665/sleep.5660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Xu Q, Song Y, Hollenbeck A, Blair A, Schatzkin A, Chen H. Day napping and short night sleeping are associated with higher risk of diabetes in older adults. Diabetes Care. 2010;33(1):78–83. 10.2337/dc09-1143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Vgontzas AN, Bixler EO, Lin H-M, Prolo P, Mastorakos G, Vela-Bueno A, et al. Chronic insomnia is associated with nyctohemeral activation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis: clinical implications. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2001;86(8):3787–94. 10.1210/jcem.86.8.7778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Faraut B, Nakib S, Drogou C, Elbaz M, Sauvet F, De Bandt J-P, et al. Napping reverses the salivary interleukin-6 and urinary norepinephrine changes induced by sleep restriction. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2015;100(3):E416–26. 10.1210/jc.2014-2566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Albanèse J, Leone M, Garnier F, Bourgoin A, Antonini F, Martin C. Renal effects of norepinephrine in septic and nonseptic patients. Chest. 2004;126(2):534–9. 10.1378/chest.126.2.534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Li X, Pang X, Liu Z, Zhang Q, Sun C, Yang J, et al. Joint effect of less than 1 h of daytime napping and seven to 8 h of night sleep on the risk of stroke. Sleep Med. 2018;52:180–7. 10.1016/j.sleep.2018.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Franke FJ, Arzt M, Kroner T, Gorski M, Heid IM, Böger CA, et al. Daytime napping and diabetes-associated kidney disease. Sleep Med. 2019;54:205–12. 10.1016/j.sleep.2018.10.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Unruh ML, Redline S, An MW, Buysse DJ, Nieto FJ, Yeh JL, et al. Subjective and objective sleep quality and aging in the sleep heart health study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2008;56(7):1218–27. 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2008.01755.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Lee Y-C, Hung S-Y, Wang H-K, Lin C-W, Wang H-H, Chen S-W, et al. Sleep apnea and the risk of chronic kidney disease: a nationwide population-based cohort study. Sleep. 2015;38(2):213–21. 10.5665/sleep.4400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Ricardo AC, Knutson K, Chen J, Appel LJ, Bazzano L, Carmona-Powell E, et al. The association of sleep duration and quality with CKD progression. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2017;28(12):3708–15. 10.1681/ASN.2016121288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Yamamoto R, Shinzawa M, Isaka Y, Yamakoshi E, Imai E, Ohashi Y, et al. Sleep quality and sleep duration with CKD are associated with progression to ESKD. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2018;13(12):1825–32. 10.2215/CJN.01340118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are openly available in CHARLS datasets at https://charls.charlsdata.com. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.