Abstract

Introduction:

Understanding the experiences of people who live with primary progressive aphasia (PPA) can inform the development of appropriate speech-language pathology services for this population. This review aimed to summarize the qualitative research on the experience of living with PPA from the perspective of the individuals with the disorder and their families.

Methods:

A scoping review was conducted.

Results:

Eight studies met the inclusion criteria. Themes in the 3 investigations that focused on the individual’s perspective included adapting to overcome language difficulties and dealing with increased dependency. Themes identified in the 5 studies that highlighted the family’s perspective included observing and adapting to language, behavioral, and social communication changes; lack of awareness of PPA; control; and the impact of the historical relationship.

Discussion:

Experiences from the 2 perspectives differed. Further research is needed, particularly in relation to identifying the general experience of PPA from the perspective of individuals with the disorder.

Keywords: primary progressive aphasia, experiences, qualitative, scoping review, family

Introduction

The primary progressive aphasias (PPAs) are a group of language-led dementias that are associated with diverse pathologies such as frontotemporal lobar degeneration and Alzheimer’s disease.1,2 Three main variants of PPA are recognized according to current diagnostic classification criteria: nonfluent (nfvPPA), semantic (svPPA), and logopenic (lvPPA). 3 In nfvPPA, speech is agrammatic and/or effortful, and halting, with inconsistent speech sound errors or distortions. 3 The second variant, svPPA, is distinguished by impairments in confrontation naming and single-word comprehension. 3 Impairments in single-word retrieval and repetition characterize the clinical presentation of lvPPA, the third main variant. 3 Other variants of PPA have also been documented, including mixed progressive aphasia and primary progressive apraxia of speech. 1,3,4 Although symptoms initially present as a focal dementia, later stages of PPA may entail widespread cognitive decline, consistent with generalized dementia. 4 The prevalence of PPA is estimated to be 3.1/100 000. 5,6 As with other types of frontotemporal dementias (FTDs), PPA tends to appear earlier than most dementias, when a person is in late middle-age and may still have dependent children and work responsibilities. 6,7 Consequently, PPA can result in a high degree of psychological and economic burden for the individual and his or her family. 8,9 A recent survey estimated that the annual per-patient cost for individuals with PPA and other subtypes of FTD was almost twice that for individuals with Alzheimer’s disease. 9

Because language function is disproportionately affected by PPA, speech-language pathologists are an integral member of the support team for those living with this disorder. 10,11 However, speech-language pathology (SLP) approaches for aphasia poststroke 12 and other types of dementia 13 may not necessarily address the specific needs of people living with PPA. Understanding the experiences of people who live with PPA can help to inform the development of SLP approaches that are tailored to address these needs. Therefore, the present review aimed to identify what is currently known about the experience of living with PPA from the perspective of the individuals with the disorder and from the perspective of their family members. By shedding light on this topic, a more person- and family-centered approach to SLP management of PPA can be developed.

Methods

To provide an overview of the literature relating to the research aim, a scoping review was conducted, based on the framework outlined by Arksey and O’Malley 14 and updated by Levac et al. 15 Scoping reviews follow a structured methodological approach and are ideal for providing a comprehensive overview of the available literature in an emerging area such as the experiences of living with PPA. This type of review does not typically set out to assess the quality of literature. 14

Identifying the Research Question

The aim of the current scoping review was to identify and summarize the current state of knowledge regarding the experiences of living with PPA from the perspective of both the individuals with the disorder and their families. To meet this aim, a broad question guided this scoping review, “What is known within the existing qualitative research literature about the experience of living with PPA?” This question was subdivided into 2 research questions:

What are the experiences of living with PPA, within the existing qualitative research literature, from the perspective of the individuals with the disorder?

What are the experiences of living with PPA, within the existing qualitative research literature, from the perspective of family members?

Identifying Relevant Studies

The search strategy was created in consultation with a research librarian. First, an initial orientation search was conducted on 2 databases (PsycINFO and the Cochrane Library) to identify relevant key words and search terms that yielded outcomes that best fit the research questions. Second, a search was conducted on March 23, 2018 on 4 electronic scientific databases (PubMed, PsycINFO, CINAHL, and the Cochrane Library), using the following search terms: primary progressive aphasia OR semantic dementia OR progressive nonfluent aphasia OR progressive logopenic aphasia (see search strategy example for PubMed in Appendix A). No limit was placed on the year of publication in order to obtain a broad overview of the research literature. The searches were restricted to peer-reviewed and English-language articles only.

Selecting the studies

Prior to selecting the studies, the 2 reviewers (K.D. and T.H.) developed a list of inclusion and exclusion criteria to determine the eligibility of the articles. Peer-reviewed articles published in English were included if they met the following criteria: (1) focused on the experience of living with PPA from the perspective of people with the disorder and/or their family members and (2) reported on investigations that used a qualitative research approach as a primary study or as part of a larger mixed-methods study. As is typical of scoping reviews, the inclusion criteria were based on the relevance of the investigations, rather than on the quality of the studies. 14 Publications were excluded if they (1) used only a quantitative research approach; (2) were anecdotal or case reports that did not use formal qualitative data collection methods; (3) were not research reports (eg, commentaries, letters to the editor, opinion papers, and blogs); (4) focused on dementia or FTD without specifying whether individuals or family members living with PPA or a specific variant of PPA were included; or (5) included participants with PPA and/or family members living with PPA but did not report research results specifically in relation to PPA. Non-English–language studies were excluded due to a lack of resources for translation.

Following the removal of duplicate articles, the 2 reviewers independently screened the title and abstract of each article to identify potentially relevant publications based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria. The reviewers then independently reviewed the full texts of these publications to identify ones that fit the criteria. Each of the full-text articles that had been identified was then discussed by the 2 reviewers to determine the final set of publications that met the inclusion criteria. Any disagreements between the 2 reviewers were resolved by consensus. A third researcher was available if the reviewers were unable to reach a consensus but was not needed. The corresponding authors were contacted when a full-text article was unavailable. A manual search of the reference lists of included articles was also performed to identify any further potentially relevant publications.

Charting the Data

The 2 reviewers independently charted the data from the selected articles in relation to the following study characteristics: author(s), location; qualitative study aims; research methodology, qualitative data collection method(s), qualitative data analysis method(s); participant(s); and study results that related to the 2 scoping review research questions. The reviewers then compared their independently extracted data and discussed any discrepancies until a consensus was reached.

Summarizing and Reporting the Results

The study characteristics were collated and summarized into 2 tables that were generated for reporting purposes based on the 2 research questions: (1) studies focusing on the experiences of living with PPA from the perspective of individuals with the disorder and (2) studies focusing on the experiences of living with PPA from the perspective of family members. As recommended for scoping reviews, 15 the first author (K.D.) conducted a thematic analysis of the included studies to identify potential themes in relation to each of the 2 research questions. The thematic analysis was based on the 6 stages proposed by Braun and Clark 16 : (1) familiarization with the data; (2) generating initial codes; (3) searching for themes; (4) reviewing themes; (5) defining and naming themes; and (6) producing the report. The first (K.D.) and second authors (T.H.) identified the final themes for each research question through a consensus discussion.

Results

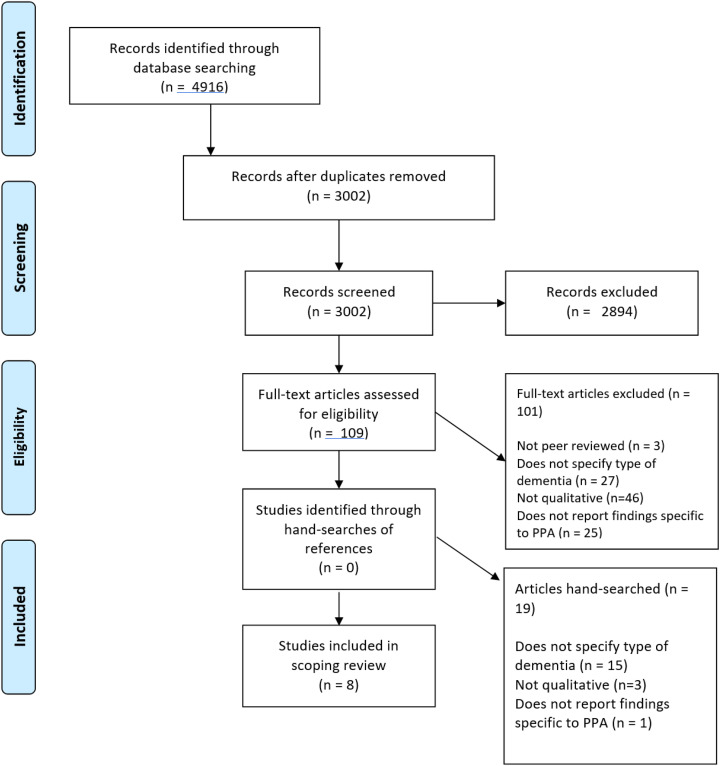

The electronic search of literature databases yielded a total of 4916 publications, 1914 of which were duplicates, leading to a total of 3002 articles. After screening titles and abstracts according to the inclusion and exclusion criteria, 109 publications were identified as potentially relevant and moved to the full-text review. The 2 reviewers independently completed the full-text screening with agreement on article inclusion/exclusion for 102 (94%) publications. After a consensus discussion on the final article inclusion, 8 of the 109 full-text publications were identified as meeting the scoping review inclusion criteria. A manual search of the reference lists of included articles did not yield any further publications. Three publications 17 -19 that provided first-hand experiences of living with PPA were excluded from this review because they were not qualitative or mixed-methods research studies. A flow diagram of the publication retrieval and selection process is provided in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of study retrieval and selection.

Study Characteristics

Specific characteristics of the included investigations are provided in Tables 1 and 2. Two studies were conducted in Australia, 27,28 2 in the United Kingdom, 22,25 2 in Canada, 20,30 1 in the United States, 24 and 1 in both the United States and Canada. 26 The research methodology of the studies varied: 3 investigations used qualitative case study, 25,27,30 1 used a constructivist grounded theory research methodology, 28 1 used mixed-methods, 20 2 used conversation analysis, 22,30 and 2 investigations did not specify a research approach. 24,26 The methods of data collection also varied across the investigations: 5 studies used individual qualitative interviews, 20,25,27,28,30 3 used video- or audio-recordings of conversations, 22,30 1 used focus groups, 26 and 1 used observational field notes in addition to audio-recordings of group sessions. 24

Table 1.

Experiences of Living With PPA From the Perspective of Individuals With the Disorder.

| Author(s) (Location) | Qualitative Study Aim(s) | Research Methodology/Qualitative Data Collection Method(s)/Qualitative Data Analysis Method(s) | Participant(s) | Key Qualitative Findings Related to the Scoping Review Question |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bier et al 20 (Canada) | To document day-to-day compensation strategies, including the use of a smartphone, of a man with svPPA | Mixed methods/semi-structured interview, based on the Canadian Model of Occupational Performance 21 /results extracted from the interview transcript | 56-year-old male with svPPA (3-4 years postdiagnosis) | “[The participant] proactively used different strategies to overcome his semantic difficulties and, apart from ARCUS [a smartphone application], he spontaneously found those strategies himself”(p. 740). These strategies included: “…always buying the same items and going to the same four grocery stores [when grocery shopping]…(p739); “To communicate with others, he mostly used e-mails since it gave him enough time to understand what he was writing or reading”(p740) |

| Kindell et al 22 (United Kingdom) | To examine the everyday conversation, at home, of an individual with svPPA | Conversation analysis/6 video-recordings of natural conversation in the home without the researcher present, and natural conversation between the individual and the researcher; Carer interview from the Conversation Analysis Profile in Cognitive Impairment 23 /Conversation analysis | 71-year-old male with svPPA (4-5 years post-diagnosis), his 71-year-old wife, and their adult son | “A recurrent and striking feature of Doug’s behaviour in conversation was his tendency to rely on enactment; he would regularly depict, or perform, his or others’ talk or thoughts, using direct reported speech, prosody and body movement as a form of communication”(p500) |

| Morhardt et al 24 (United States) | To explore the impact of a talk-based psycho-educational support program on individuals experiencing a progressive loss of language and on their care partnersa | Not specified/pilot group: Observational field-notes; Formal group: Observational field-notes; Audio-recordings of 2 group sessions/thematic analysis | Pilot group: 2 females and 4 males with PPA (subtypes unspecified; time post-diagnosis unspecified; all individuals in early-moderate stage); aged 53-80 years; mean = 67.5 years. Formal group: 4 females and 5 males with PPA (including 5 individuals from the pilot group) and 8 family members (subtypes unspecified; time post-diagnosis unspecified); aged 55-82 years; mean = 67.2 years |

Themes: (1) Coping with limitations and language decline—“Participants expressed frustration and sadness surrounding the loss of language abilities”(p6); (2) Dealing with increased dependency—“There were mixed feelings regarding the increased dependency on others, particularly family members”(p6); (3) Expressing resilience and making adaptations—“There was generous enthusiasm and sharing of helpful compensation strategies with other group members”(p7); (4) Experiencing stigma (Pilot group) and confronting stigma (Intervention group) “The group members used the group to discuss the challenges associated with communicating their changing needs and the experience of PPA to others”(p6); (5) Experiencing self-confidence—“Rather than being inhibited by it [confronting stigma], there was an overall expression of self-efficacy and appreciation for the opportunity the group provided to engage in a social situation; however, challenging”(p14); (6) Feeling a sense of belonging—“Participants would ask each other if they were experiencing similar symptoms and were comforted to know that they were not alone”(p7) |

Abbreviations: PPA, primary progressive aphasia; svPPA, semantic variant PPA.

a Qualitative results reported in the study only related to the experiences of individuals with PPA.

Table 2.

Experiences of Living With PPA From the Perspective of Family Members.

| Author(s) (Location) | Qualitative Study Aim(s) | Research Methodology/Qualitative Data Collection Method(s)/Qualitative Data Analysis Method(s) | Participant(s) | Key Qualitative Findings Related to the Scoping Review Question |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kindell et al 25 (United Kingdom) | To describe the experiences of a wife and son caring for a husband/father with svPPA | Qualitative case study/individual semistructured interviews/thematic narrative analysis | 71-year-old wife and adult son of individual with svPPA 4-5 years post-diagnosis | Themes: (1) Living with routines—“Doug had developed a number of complex routines since the start of his semantic dementia…Over time, Karina and Stuart had become accustomed to these routines and rather than try to change Doug’s behaviour, their caring now took account of them” (p. 404); (2) Policing and protecting—“Karina and Stuart reported a need to monitor, or ‘police,’ Doug’s behavior, constantly having to be vigilant and keep an eye on what he was doing” (p. 404); (3) Making connections—“There was…a sense that the deeper, more emotional levels of making connections were missing. Despite this, both Karina and Stuart continued to make attempts to include Doug in conversation and encourage him to talk” (p. 405); (4) Being adaptive and flexible—“There had been a change in Doug’s personality, his style of talking, the people and situations he engaged with, his interests, and the topics he talked about…To maintain a caring and family identity, Karina and Stuart had to be flexible and adapt to these changes while still preserving Doug’s roles as husband and father”(p406) |

| Nichols et al 26 (Canada and United States) | To learn more about the needs and experiences of young carers for patients with frontotemporal dementia in order to create a relevant support web site for young caregivers to patients with dementia | Not specified/focus groups/thematic analysis | 16-year-old son of man with PPA (subtype unspecified; time post-diagnosis not specified). The study also included 13 other children/stepchildren/ grandchildren of individuals with FTD, but not PPA | Symptoms of frontotemporal dementia: “Primary Progressive Aphasia—many doctors have no idea even what it is…a ton of other people think that since it’s called ‘aphasia’ that the person can’t really speak and it doesn’t relate to behavioral changes, and it absolutely does” |

| Pozzebon, et al 27 (Australia) | To understand how a spouse dealt with and negotiated the ongoing relational changes and psychosocial challenges of living with a partner through the course of svPPA | Qualitative instrumental case study/in-depth interview/thematic narrative analysis | Wife of man with svPPA who was died at the time of interview, age not stated | Themes: (1) Us—“Their close emotional bond was forged over 40 years prior to the onset of svPPA”(p379); (2) The way he was…The way he is now—“Mary gave a detailed account about how the insidious onset and progression of svPPA dramatically changed her husband’s personality and his interactions with her”(p380); (3) Floundering with unpredictability—“Particularly during the pre-diagnostic period, Mary had no feasible explanations to account for Geoff’s personality changes”(p381); (4) Adjusting and accepting support—“Over time,…[Mary] learnt to adjust and accommodate Geoff’s unpredictability and declining cognitive communication abilities…Mary only accessed help when she was desperate…Immediately after this event [a critical incident] Mary accepted whatever help and assistant was available”(p382); (5) Taking control—“For most of their married life and into the mid-phases of the svPPA, Geoff took the lead in decision-making, but this was not viable as he deteriorated. It was the critical event of selling their home that compelled Mary to turn the corner and take control”(p383); (6) Back to floundering with grief—“Mary’s previous feelings of floundering resurfaced immediately following Geoff’s death…For Mary, dealing with loss characterized her entire journey with svPPA”(p384) |

| Pozzebon et al 28 (Australia) | To explore the spousal recollections that for them signalled the earliest signs of PPA | Constructivist grounded theory/in-depth interviews/Initial open coding of “Initial/early signs”; quotes coded to most suitable DSM-5 neurocognitive domain 29 | 12 wives and 1 husband of 6 individuals with svPPA, 5 with lvPPA, and 2 with nfvPPA (1-7 years post-diagnosis) aged 54-82 years; mean = 70.9 years | (1) Earliest signs of svPPA: “[C]hanges in social cognition presenting concurrently with language difficulties…signalled the start of illness onset.”(p286) (2) Earliest signs of lvPPA: “Changes in social cognition as the earliest presenting symptoms preced[ed] the language difficulties…Reduced talking and cessation of emotional intimacy [were] the most prominent earliest signs of lvPPA, especially obvious in a social group setting.”(p288) (3) Earliest signs of nfvPPA: “Speech-language difficulties as the earliest presenting sign…[S]ubtle social cognition issues emerged about 1-2 years post-diagnosis”(p290) |

| Purves 30 (Canada) | To describe how the husband of a woman with nfvPPA and their adult children experienced and interpreted his ways of speaking for hera | Qualitative case study/semistructured interviews; audiorecordings of natural conversations involving the individual with nfvPPA and at least 2 other participants/thematic analysis and conversation analysis | 63-year-old female with nfvPPA (6 months post-diagnosis), her husband, 2 adult daughters, and 2 adult sons | The husband used 3 different patterns of “speaking-for” behaviors with his wife: (1) speaking in support of; (2) speaking on behalf of; and (3) speaking instead of. Themes related to these “speaking for” behaviors: (1) Historically familiar—“It represented a long-standing pattern in their relationship”(p917); (2) Interactionally problematic—“Margaret’s increasing difficulties in speaking for herself made this long-established pattern problematic”(p917); (3) Strategically compensatory—“Family members also recognized the different ways in which those behaviors supported interactions”(p918) |

Abbreviations: DSM-5, Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th Edition; FTD, frontotemporal dementia; PPA, primary progressive aphasia; svPPA, semantic variant PPA; nfvPPA, nonfluent variant PPA; lvPPA, logopenic variant PPA.

a Qualitative results reported in the study only drawn from experiences of family.

Experiences of Living With PPA From the Perspective of Individuals With the Disorder

Three of the included studies reported experiences of living with PPA from the perspective of individuals with the disorder who ranged in age from 53 to 82 years (see Table 1). 20,22,24 One of these investigations focused on a male with svPPA who was 3 to 4 years post-diagnosis, 20 one focused on a male with svPPA who was 4 to 5 years post-diagnosis, 22 and one did not report the PPA variants of the participants. 24

Six themes were identified in the included studies: adapting to overcome language difficulties; dealing with increased dependency; coping with limitations and language decline; experiencing and confronting stigma; experiencing self-confidence; and feeling a sense of belonging. All 3 of the studies reported findings related to developing adaptations for overcoming language difficulties. For example, the finding of expressing resilience: adapting and sharing compensatory strategies, in the Morhardt et al study, 24 encompassed strategies (eg, sitting next to people who liked to talk so the person with PPA did not have to talk as much) that the individuals with PPA had for overcoming difficulties with everyday communication activities such as having conversations and reading. Similarly, the main finding in the Kindell et al investigation 22 was that the participant with svPPA had spontaneously acquired the adaptive strategy of enactment to communicate more effectively with others during conversations. This strategy involved using direct reported speech, 31 paralinguistic, and/or nonverbal communication to overcome semantic difficulties. Finally, the Bier et al study 20 revealed that the participant with svPPA had developed a number of adaptive strategies for communicating such as using e-mail to maintain contact with other people. This investigation, also reported on adaptations that the individual with svPPA had made during more general everyday activities such as cooking and grocery shopping, in addition to adaptations made in communication-specific activities such as reading and conversing.

Dealing with increased dependency was also revealed as a theme in the investigations. The participants with PPA in the Morhardt at al 24 study were reported to have mixed emotions regarding their increased dependence on family and others as their disorder progressed. Similarly, the participant with PPA in the investigation by Brier et al 20 reported an increased dependency on his wife, indicating that it was important to him to complete chores at home independently while his spouse was at work.

Four themes were identified only in the Morhardt et al investigation. 24 First, within the theme of coping with limitations and language decline, participants reported experiencing frustration and sadness as a result of the loss of their language abilities. Second, within the theme of experiencing and confronting stigma, individuals in the pilot support group phase of the Morhardt et al study highlighted that they experienced stigma when they shared their changing needs and experience of PPA with other people. 24 However, in the intervention support group phase of the investigation, the participants indicated that they felt more empowered to share their diagnosis with others and to confront any stigma that they experienced. 24 Another theme from this investigation 24 involved the individuals with PPA experiencing self-confidence as a result of being able to participate in the social situation of the support group. Finally, within the theme of feeling a sense of belonging, the investigation reported that by participating in a psychoeducational group, the participants with PPA felt supported in knowing that they were not the only ones with the disorder. 24

Experiences of Living With PPA From the Perspective of Family Members

Five of the included studies presented the experiences of living with PPA from the perspective of family members (see Table 2). 25,26,27,28,30 Family members in these investigations ranged in age from 16 to 85 years and comprised 14 wives, 2 husbands, 2 adult daughters, 3 adult sons, and 1 adolescent son. One of the 5 studies focused on the spouses of 6 individuals with svPPA, the spouses of 5 individuals with lvPPA, and the spouses of 2 individuals with nfvPPA 28 ; one focused on 5 relatives of a female with nfvPPA 30 ; one focused on 2 relatives of a male with svPPA 25 ; and one focused on the wife of a male who died and had svPPA. 27 One investigation that explored relatives’ experiences focused on family members living with FTD in general and only reported that 1 participant was a family member of an individual with PPA, without specifying the variant of PPA. 26

A thematic analysis of the findings from the family member studies revealed 6 themes: observing and adapting to language, behavioral, and social communication changes; lack of awareness of PPA; control; the impact of the historical relationship; dealing with loss and grief; and support. The theme of observing and adapting to language, behavioral, and social communication changes included family members noticing linguistic changes in their relatives with PPA, with 4 of the investigations 22,26,27,28 revealing findings about the family’s experiences of behavioral and social communication changes in their relatives. For example, in the Pozzebon et al investigation, 27 the wife of an individual with svPPA noticed that the insidious onset and progression of the disorder dramatically changed her husband’s personality and his interactions with her. Similarly, a teenage boy in the Nichols et al investigation 26 reported being frustrated because doctors and others seemed unaware that individuals with PPA such as his father could demonstrate behavioral changes in addition to language difficulties. In the Kindell et al study, 25 the family members of a man with svPPA indicated that they had to adapt to his evolving personality changes and to his unusual behavioral routines such as touching and sorting through rubbish and rubbing the soles of his shoes and then objects in the house. Similarly, the participant in the Pozzebon et al investigation 27 reported having to adjust and accommodate to the unpredictable and declining cognitive communication abilities of her husband with svPPA. Finally, early changes in social cognition were identified as a feature of all 3 variants of PPA by the spouses in Pozzebon et al’s investigation. 28

The theme of lack of awareness of PPA was also identified in the family member studies. The participants in Pozzebon et al, 28 which focused on spousal experiences during the early stages of PPA, frequently reported not understanding what their spouses were experiencing or why symptoms were occurring. They also reported frustration with a lack of awareness of PPA from medical professionals, feeling symptoms were often dismissed as insignificant. Similarly, the spouse from another family investigation 27 experienced confusion during the prediagnostic period around not understanding why her husband’s personality and behavior was changing. Last, this theme emerged in a third family investigation, Nichols et al, 26 whose participant expressed frustration around medical professionals not knowing what her father’s diagnosis of PPA entailed.

The theme of control was also identified in 2 family member investigations. 25,27 For example, this finding was revealed in the Kindell et al study, 25 with the family members reporting having to control the behavior of their relative with svPPA by constantly monitoring and policing his behavior. Similarly, in the Pozzebon et al study, 27 the spouse felt compelled to take control of the decision-making role within her marriage after a critical incident involving her husband with svPPA.

Two of the family investigations 27,30 included a theme involving the impact of the historical relationship with the individual with PPA on the experience of living with PPA. In the Pozzebon et al study, 27 the participant described how she was able to use the positive memories from her decades-long strong relationship with her husband, to help her to cope with the relationship difficulties she encountered after the onset of his svPPA. The historical impact of a couple’s relationship also played a role in the experiences highlighted in the study by Purves. 30 In this investigation, 30 it was revealed that the husband’s “speaking for behaviors” (ie, speaking on his wife’s behalf) when communicating with his spouse with nfvPPA represented a long-standing pattern in their relationship. This pattern was initially problematic during initial stages of language difficulties, but these behaviors later became a strategic compensatory strategy. 30

Dealing with loss and grief was also revealed as a theme in the family member investigations. In the Pozzebon et al study, 27 the family member, who was interviewed after her husband with svPPA had died, reported that loss characterized her entire journey of living with svPPA and that because of this, she experienced bereavement in a nonconventional way. Loss was also highlighted in the Kindell investigation, 25 with the family members reporting that they missed the opportunity to have deeper and more emotional connections with their relative as the result of his svPPA.

The theme of support emerged within 2 family investigations. 27,28 In one study, 27 a spouse of an individual with PPA reported her experiences accepting emotional and financial support in both the early and later stages of her husband’s PPA. In contrast, spouses from the 2018 Pozzebon et al 28 investigation reported a lack of support during the prediagnostic and early phases of living with an individual with PPA.

Discussion

This scoping review identified research studies that have explored the experiences of living with PPA. Only 8 studies met the final inclusion criteria for the review, with 3 focusing on the perspective of the individuals with PPA and 5 focusing on the perspective of the family members. Experiences of the individuals with PPA in these investigations highlighted themes involving adapting to overcome language difficulties; dealing with increased dependency; coping with limitations and language decline; experiencing and confronting stigma; experiencing self-confidence; and feeling a sense of belonging. In contrast, family member experiences were characterized within the themes of observing and adapting to language, behavioral and social communication changes; lack of awareness of PPA; control; the impact of the historical relationship; dealing with loss and grief; and support.

The findings from the review suggest that there may be differences between the experiences of people with PPA and those of their family members. For example, although loss and adaptation were highlighted by both groups, people with PPA tended to focus on language loss and adaptations for overcoming the language difficulties (eg, asking others to repeat their questions so that the individual with PPA has more time to formulate their responses). 24 In contrast, family members tended to focus more broadly on loss and adaptation related to the individual’s behavioral, social communication, and personality changes (eg, preventing the person with svPPA from doing chores involving the rubbish bins because of his tendency to rub his hands on objects), in addition to linguistic changes. In order to provide a more person-centered approach, speech-language pathologists may need to ensure they focus broadly on the impact of the disorder on the individual’s interpersonal communication and family relationships, rather than solely on linguistic changes. The use of multicomponent interventions that include communication partner training and support strategies may be valuable for addressing these areas. 13,32

The review also revealed differing perspectives in relation to the experiences of dependency and control. As the disorder progressed, some individuals with PPA experienced mixed emotions over becoming increasingly dependent on their families. 24 In contrast, the need to take control and protect the individual with PPA as the disorder progressed caused stress for a spouse in one study. 25 This shift may affect their relationship and ability to adapt to living with the disorder.

It is noted that these divergent perspectives may reflect differences in the included studies’ aims and participant inclusion criteria. Three of the 5 family studies explored the overall experience of living with PPA, 25,26,27 whereas none of the 3 individual investigations focused on this more general perspective. Rather, these studies provided a more specific lens, with one investigating the experiences of participating in a psychoeducational support group, 24 one exploring the use of compensatory communication strategies, 20 and one analyzing the everyday conversations of an individual with PPA. 22 The family investigations also included findings involving the experiences of living with individuals with svPPA, lvPPA, and nfvPPA. In contrast, 2 of the 3 individual investigations focused on svPPA, with the third study not specifying the PPA variant(s) of the participants.

Strengths and Limitations

To our knowledge, this is the first scoping review of the literature focusing on the experiences of living with PPA. A key strength of the review was the use of a broad search strategy that included all publications that focused on PPA or the 3 main variants of PPA within the selected databases. The scoping review also met all but one of the required criteria as outlined in the PRISMA extension for scoping reviews. 33,34 The exception was that a registered protocol was not developed before the search was conducted, as the review was initiated prior to the publication of the PRISMA guidelines. 33,34 Another limitation of the scoping review was that it included only studies published in English, due to lack of resources for translation. Experiences of PPA explored in studies conducted in other languages will have been missed. Finally, it is important to note that recent research, which meets the inclusion criteria, has been published after the date that the scoping review search was conducted. This research includes an investigation of the experiences of participating in an aphasia camp for a couple living with PPA. 35

Conclusion and Future Directions

This scoping review identified and summarized the current qualitative literature about the experience of living with PPA from the perspective of people with the disorder and from the perspective of their family members. In general, the review revealed that the research about the experience of living with PPA is limited and that the findings differ across the 2 perspectives. Future investigations are needed to explore the overall experience of living with PPA, particularly from the perspective of the individuals with the disorder. In addition, for the most part, the included studies did not explore how the experiences of living with PPA changed as the disease progressed or how experiences varied depending on the subtype of PPA. Research in these areas can help to provide a more comprehensive account of the experience of living with PPA in order to inform the development of appropriate SLP management approaches for this population.

Appendix A

Search Strategy

March 23rd, 2018

Database: Pubmed 1946-present

Search Strategy:

((“primary progressive aphasia”[All Fields] OR “semantic dementia”[All Fields]) OR “progressive nonfluent aphasia”[All Fields]) OR “progressive logopenic aphasia”[All Fields] AND English[lang]

Footnotes

Authors’ Note: All authors have read the final manuscript draft and approve it for submission.

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The authors disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: The University of British Columbia Four Year Doctoral Fellowship.

ORCID iD: Katharine Davies  https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5766-229X

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5766-229X

References

- 1. Marshall CR, Hardy CJD, Volkmer A, et al. Primary progressive aphasia: a clinical approach. J Neurol. 2018;265(6):1474–1490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Grossman M. Primary progressive aphasia: clinicopathological correlations. Nat Rev Neurol. 2010;6(2):88–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Gorno-Tempini ML, Hillis AE, Weintraub S, et al. Classification of primary progressive aphasia and its variants. Neurology. 2011;76(11):1006–1014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Mesulam M, Rogalski EJ, Wieneke C, et al. Primary progressive aphasia and the evolving neurology of the language network. Nat Rev Neurol. 2014;10(10):554–569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Magnin E, Démonet J, Wallon D, et al. Primary progressive aphasia in the network of French Alzheimer plan memory centers. J Alzheimers Dis. 2016;54(4):1459–1471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Coyle-Gilchrist ITS, Dick KM, Patterson K, et al. Prevalence, characteristics, and survival of frontotemporal lobar degeneration syndromes. Neurology. 2016;86(18):1736–1743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Volkmer A, Spector A, Warren J, Beeke S. Speech and language therapy for primary progressive aphasia: referral patterns and barriers to service provision across the UK. Dementia. 2018;0(0):1–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Nickels L, Croot K. Understanding and living with primary progressive aphasia: current progress and challenges for the future. Aphasiology. 2014;28(8-9):885–899. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Galvin JE, Howard DH, Denny SS, Dickinson S, Tatton N. The social and economic burden of frontotemporal degeneration. Neurology. 2017;89(20):2049–2056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. McNeil MR, Duffy JR. Primary progressive aphasia. In: Chapey R, ed. Language Intervention Strategies in Aphasia and Related Neurogenic Communication Disorders. 4th Ed. Baltimore, MD: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2001:472–486. [Google Scholar]

- 11. American Speech-Language-Hearing Association. Evidence Maps, Dementia, Roles and Responsibilities of Speech-Language Pathologists. https://www.asha.org/PRPSpecificTopic.aspx?folderid=8589935289§ion=Roles_and_Responsibilities. Accessed February 23, 2019.

- 12. Holland AL, Nelson RL. Counseling in Communication Disorders: A Wellness Perspective. San Diego, CA: Plural Publishing Inc; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Rogalski EJ, Khayum B. A life participation approach to primary progressive aphasia intervention. Semin Speech Lang. 2018;39(3):284–296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Arksey H, O’Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol. 2005;8(1):19–32. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Levac D, Colquhoun H, O’Brien KK. Scoping studies: advancing the methodology. Implement Sci. 2010;5(1):69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Braun V, Clarke V. Thematic analysis. In: Cooper H, ed. APA Handbook of Research Methods in Psychology, Research Designs, Vol. 2. Washington, DC. APA books; 2012: 57–71. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Douglas JT. Adaptation to early-stage nonfluent/agrammatic variant primary progressive aphasia: a first-person account. Am J Alzheimers Dis. 2014;29(4):289–292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Lamont M. Semantic dementia: a long, sad, lonely journey. Aust J Dement Care. 2015;3(6):25–27. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Rutherford S. Our journey with primary progressive aphasia. Aphasiology. 2014;28(89):900–908. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Bier N, Paquette G, Macoir J. Smartphone for smart living: using new technologies to cope with everyday limitations in semantic dementia. Neuropsychol Rehabil. 2018;28(5):734–754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Townsend EA, Polatajko HJ. Enabling Occupation II: Advancing an Occupational Therapy Vision for Health, Well-Being, & Justice Through Occupation. Ottawa, CA: CAOT Publications Ace; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Kindell J, Sage K, Keady J, Wilkinson R. Adapting to conversation with semantic dementia: using enactment as a compensatory strategy in everyday social interaction. Int J Lang Commun Disord. 2013;48(5):497–507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Perkins L, Whitworth A, Lesser R. Conversation Analysis Profile for People with Cognitive Impairment. London, UK: Whurr; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Morhardt DJ, O’Hara MC, Zachrich K, Wieneke C, Rogalski EJ. Development of a psycho-educational support program for individuals with primary progressive aphasia and their care-partners. Dementia. 2017. doi: 10.1177/1471301217699675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Kindell J, Sage K, Wilkinson R, Keady J. Living with semantic dementia: a case study of one family’s experience. Qual Health Res. 2014;24(3):401–411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Nichols KR, Fam D, Cook C, et al. When dementia is in the house: needs assessment survey for young caregivers. Can J Neurol Sci. 2013;40(1):21–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Pozzebon M, Douglas J, Ames D. . “It was a terrible, terrible journey”: an instrumental case study of a spouse’s experience of living with a partner diagnosed with semantic variant primary progressive aphasia. Aphasiology. 2017;31(4):375–387. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Pozzebon M, Douglas J, Ames D. Spousal recollections of early signs of primary progressive aphasia. Int J Lang Commun Disord. 2018;53(2):282–293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5th ed. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Association; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Purves BA. The complexities of speaking for another. Aphasiology. 2009;23(7-8):914–925. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Goodwin MH. He-Said-She-Said: Talk as Social Organization among Black Children. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Volkmer A, Spector A, Meitanis V, Warren JD, Beeke S. Effects of functional communication interventions for people with primary progressive aphasia and their caregivers: a systematic review. Aging Ment Health. 2019;1–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, et al. PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): checklist and explanation. Ann Intern Med. 2018;169(7):467–473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, et al. A scoping review on the conduct and reporting of scoping reviews. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2016;16(1):15–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Kim ES, Figeys M, Hubbard HI, Wilson C. The impact of aphasia camp participation on quality of life: a primary progressive aphasia perspective. Semin Speech Lang. 2018;39(17):270–283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]