Summary

Mutation accumulation in stem cells has been associated with cancer risk. However, the presence of numerous mutant clones in healthy tissues has raised the question of what limits cancer initiation. Here, we review recent developments in characterizing mutation accumulation in healthy tissues and compare mutation rates in stem cells during development and adult life with corresponding cancer risk. A certain level of mutagenesis within the stem cell pool might be beneficial to limit the size of malignant clones through competition. This knowledge impacts our understanding of carcinogenesis with potential consequences for the use of stem cells in regenerative medicine.

Keywords: stem cell genomics, somatic mutations, carcinogenesis, clonal dynamics

The presence of mutant clones in healthy tissues has raised the question of what limits cancer initiation. Here, we review recent developments in characterizing mutation accumulation in stem cells during development and adult life, and we compare mutation rates with clonal dynamics in stem cell pools and corresponding cancer risk.

Introduction

Cancer is driven by oncogenic mutations. These somatic mutations accumulate during healthy life and can promote the expansion of individual clones within competing stem and progenitor cell pools.1 Indeed, the clonal mutational burden of cancers correlates with the age of the patient at diagnosis, indicating that a large proportion of cancer mutations is acquired prior to tumor initiation.2 Somatic mutations in stem cells are thought to have the largest effect on the total mutational burden within tissues, as they are long-lived, self-renew, and propagate mutations to differentiated progeny.3,4 Accordingly, a correlation was reported between cancer risk in different organs and the total number of stem cell divisions in corresponding tissues.3 This observation suggests that somatic mutations acquired during normal proliferation of stem cells, required to maintain tissue homeostasis, is a crucial contributor to carcinogenesis. This so-called “bad luck” hypothesis has been heavily debated.5 In addition, various environmental factors are known to be carcinogenic.6 Nonetheless, introducing oncogenic mutations in tissue-specific stem cells of transgenic mice efficiently induces malignant transformation, whereas this is not the case in non-stem cells.7,8

Although these findings indicate that the accumulation of mutations in stem cells is an important factor for carcinogenesis, the cancer cell of origin does not necessarily need to be a stem cell. More committed cells can regain stemness and initiate carcinogenesis (reviewed in Friedmann-Morvinski and Verma9). Nonetheless, multiple genetic hits are needed for cancer initiation, and it is likely that at least the initial hits were acquired in a stem cell. An example is the presence of DNMT3A-mutated, pre-leukemic hematopoietic stem/progenitor cells (HSPCs) in patients with acute myeloid leukemia (AML), which can still be found in remission samples after treatment.10

The exact rate-limiting step for the initiation of cancer remains unclear. Is it the sequential acquisition of an appropriate combination of oncogenic hits in stem cells that allows for transformation and clonal expansion as posited by the somatic mutation theory of cancer?11 If so, malignant transformation is a simple numbers game, whereby the chances are increased if one or multiple oncogenic hits are acquired in long-lived stem cells. Alternatively, selection of premalignant clones by a changing microenvironment could equally be the rate-limiting step for oncogenesis.12 An example supporting this idea is the observation that HSPCs carrying age-related TP53 mutations are selected by chemotherapy exposure and can give rise to clonal hematopoiesis and therapy-related AML.13,14 Identification of the rate-limiting step for carcinogenesis is highly relevant for preventive strategies and perhaps even treatment. Should we target the phenotypic consequences of an oncogenic mutation or prevent the context-dependent selection of existing mutant clones? Optimized preventive strategies will be important not only in oncology but also in regenerative medicine. The transplantation of stem cells extends their lifespan, both in vitro and in vivo, thereby increasing the time frame where cells are susceptible to oncogenic mutation and transformation. In this review, we will highlight the latest developments in understanding mutation accumulation in stem cells, how it contributes to carcinogenesis, and its possible consequences for stem cell use in regenerative medicine.

Assessing mutation rates in single stem cells

Although single-cell genomics technologies have revolutionized our understanding of stem cell biology and cancer development, sequencing the DNA of single cells has remained challenging. A single cell does not contain enough DNA for whole-genome sequencing analysis, and therefore, amplification is required. However, traditional whole-genome amplification (WGA) technologies, based on strand displacement polymerases, cause amplification biases, artifacts, and allelic dropouts.15,16 To overcome these challenges, different experimental strategies have been developed (Figure 1). One method to assess somatic mutations in single cells is to sequence clonal cell cultures.17,18,19,20,21 Each cell in these clonal cultures will share all the mutations that were present in the parental cell. However, mutations that accumulated after the first cell division will be shared by only a subset of cells and will therefore have a lower variant allele frequency in the sequencing data (Figures 1 and 2).22 This approach is especially well suited for assessing mutation accumulation in stem and progenitor cells, as they can be phenotypically or functionally selected and clonally expanded in culture systems. Reprogramming individual somatic cells into induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) is another way to obtain clonal cultures and sufficient DNA of the parental cell for sequencing analysis.23 One potential disadvantage of generating in vitro clonal stem cell cultures is that the culture system may induce a selective pressure, such as negative selection of highly damaged stem cells. Alternatively, microscopic clonal structures that exist in healthy tissues can be used to assess the mutations that were present in the parental cell by combining microdissection with low-input DNA sequencing (Figure 1).24,25 However, potential disadvantages of this approach are that the identity of the parental cell (i.e., a stem or more differentiated cell) is not always known. Additionally, it is unknown when the parental cell existed during the lifetime of the donor.

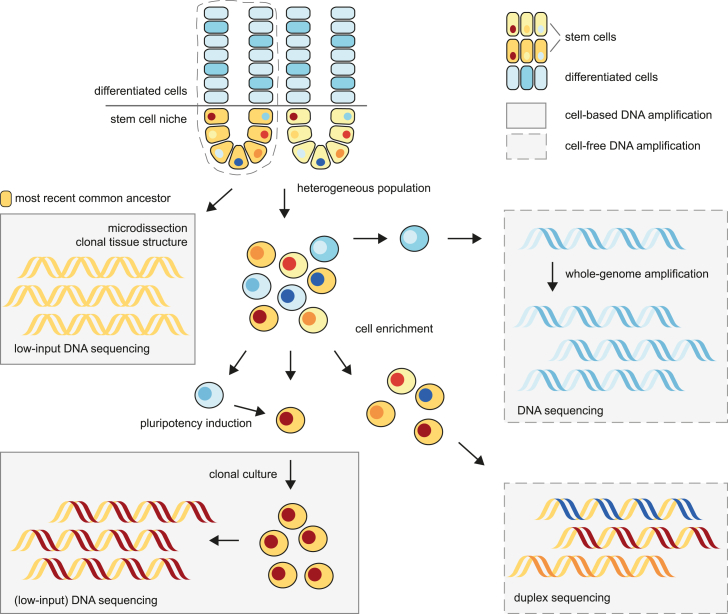

Figure 1.

Strategies for whole-genome sequencing of stem cells

Laser microdissection of clonal tissue structures enables the DNA sequencing of a shared common ancestor (top left). Alternatively, mutations present in a cell population can be detected at low frequencies through duplex sequencing after enrichment of the cell type of interest (lower right). The DNA of individual cells can be amplified through cell-based clonal expansion of stem cells (lower left) or whole-genome amplification of any cell (upper right).

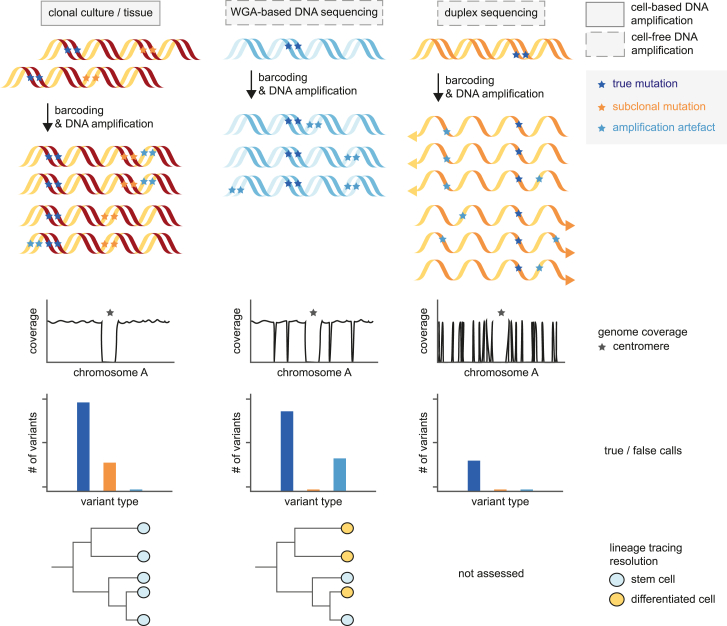

Figure 2.

DNA amplification methods and outcomes in single-cell whole-genome sequencing strategies

Although the DNA sequencing of clonally expanded stem cell cultures or tissue structures (left) results in even genome coverage and efficient filtering of amplification artifacts (light blue), stringent filtering is required to remove subclonal mutations (orange) present in the total population. Such subclonal mutations are not present in sequencing libraries based on whole-genome amplification of single cells (center), although these methods suffer from allelic dropout and amplification artifacts. Both amplification artifacts and subclonal variants are efficiently removed in duplex sequencing (right). However, phylogenetic lineage tracing is impossible as individual mutations are not linked to single cells.

Nonetheless, sequencing both clonal intestinal organoid cultures and individual crypts yielded very similar results, indicating that both approaches are valid.18,24 In the past years, WGA techniques have also improved, and the various types of artifacts associated with this approach have decreased significantly.16,26,27 In addition, bioinformatic approaches, including machine learning, can filter artifacts from WGA-based sequencing data.28,29 These methods allow for assessing mutation accumulation not only in stem cells27,28 but also in postmitotic and more differentiated cells, such as neurons and B lymphocytes (Figures 1 and 2).29,30,31 Finally, duplex sequencing has been used to assess mutations in individual DNA molecules, which can be extrapolated to a single genome (Figure 2).32,33,34,35 The advantage of this latter approach is that it can be applied to bulk tissue samples. However, such samples may contain various cell types, and it is impossible to know the cell type a molecule originated from in the sequencing data. Therefore, enrichment of specific populations prior to sequencing is warranted. Together, these technological advances allow genome-wide assessment of mutation accumulation in stem cells and their progeny, advancing our understanding of how mutation load corresponds to cancer risk.

Mutation accumulation in fetal stem cells

Stem cells start acquiring mutations immediately after conception, and these mutations are inherited by all surviving daughter cells. Their lineages can potentially span large body regions across multiple tissues and even the germ line.36 The consequences of pervasive mutations arising in embryonic development can be deleterious. For this reason, the occurrence rate of these mutations is expected to be minimized. Over the years, the extent of these mutations has been characterized directly through the sequencing of fetal tissues or inferred by phylogenetic analyses based on sequencing data that include multiple adult cells or tissues.19,36,37,38,39,40 Although in adult stem cells, between 13 and 40 mutations are acquired per year, omnipotent stem cells acquire 2–3 mutations per division immediately after conception.36,39,41,42 These error-prone divisions precede genome activation and thus transcription-coupled repair and the replenishment of diluted maternal factors, explaining the high error rate.43 The mutation rate quickly drops to an average of 1.6 mutations per division between conception and gastrulation, before reducing further below 0.9 mutations per division at 8 weeks post-conception (Figure 3A).36,39,42 Bulk RNA sequencing of multiple tissues in adult life also suggests that the highest mutation rate is found early in embryonic development.40 Despite a rapidly decreasing mutation rate, developmental mutation rates are still higher than in their matched postnatal tissue type. In HSPCs, the yearly mutation rate is 5.8-fold higher during development than that in postnatal life (Figures 3B–3D).37 This phenomenon was also observed based on clonally expanded fetal neuronal progenitor cells and liver and intestinal stem cells.38,44 Indirect measurements of the fetal mutation accumulation rate, through estimating the number of somatic mutations present at birth of different tissue types, indicated that a similar phenomenon occurs in colonic crypts.32

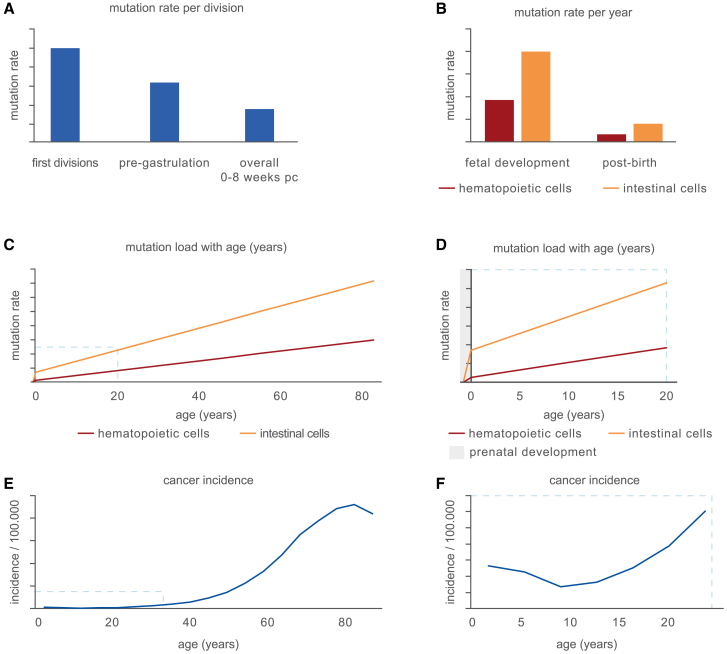

Figure 3.

Mutation accumulation and cancer incidence throughout life

(A) Schematic comparison of the rate of mutation accumulation per division in different stages of embryonal development. Mutation rates depicted are reported in Park et al.,36 Spencer Chapman et al.,39 Ju et al.,41 and Hasaart et al.42 pc: post-conception.

(B) Schematic representation of the rate of mutation accumulation per year during fetal development and life after birth in different tissues. Exact rates are reported for hematopoietic cells in Osorio et al.20 and Hasaart et al.37 (red) and intestinal stem cells in Blokzijl et al.18 and Kuijk et al.38 (orange).

(C) Graphical overview of the cumulative mutation load in stem cells throughout life of the tissues depicted in (B).

(D) The total mutation load as shown in (C), focused on early life including prenatal development (gray).

(E) Graphical representation of the total cancer incidence per age in years as available in Surveillance Research Program and National Cancer Institute45 (F) as in (E), focused on early life.

Overall, these results suggest that stem cells in developing tissues are subjected to higher somatic mutation rates than their postnatal counterparts. It could be argued that this phenomenon occurs because of the rapid proliferation of stem cells during the developmental processes. However, strong evidence suggests that the extent of mutation accumulation is not primarily determined by proliferation rates. For example, liver and intestinal stem cells accumulate about 40 mutations per year postnatally under homeostatic conditions, although the latter pool of stem cells divides much more rapidly.18,46,47 Accordingly, iPSCs derived from primary fibroblasts show a reduced mutation rate per cell division compared with the isogenic parental cells, despite a similar cell-cycle length in vitro.23 Clearly, cells possess a capacity to limit mutagenesis associated with an increased proliferation rate, but this capacity is either not fully realized or insufficient. Multiple processes, such as the short cell-cycle length and extensive chromatin remodeling, accompanied by lenient cell-cycle and DNA damage checkpoints, may result in unavoidable mutation accumulation in prenatal developing stem cells.48,49,50,51 In addition, stem and progenitor cells during prenatal development52 and germ cells are programmed for DNA damage hypersensitivity.53 Nonetheless, DNA mutations are still accumulated at a remarkable rate during prenatal development, leading to a relatively high mutation load at birth (Figures 3C and 3D). Due to the limited timespan for mutation accumulation during prenatal development, the absolute number of mutations at birth remains low, which may contribute to the low rate of childhood cancer. Overall, the total mutation load is not predictive of cancer incidence in early life, which drops slightly after early childhood (Figures 3E and 3F).45 These findings suggest that rather than mutation accumulation itself, other rate-limiting factors determine the cancer incidence in early life.

Mismatch of oncogene occurrence and cancer incidence in early life

Clonal expansions have been reported in the blood of newborns, harboring oncogenic mutations.54,55,56,57,58 Translocations are of particular interest, as gene fusions play a major role in driving pediatric leukemia.59,60,61 Indeed, the malignant expansion is thought to originate in utero for certain types of pediatric cancer.62 Assuming that the formation of a driver translocation is the rate-limiting step in oncogenesis, healthy newborns that never develop cancer should not harbor the associated driver translocations in their hematopoietic system. It is commonly believed that 1%–5% of newborns carry the oncogenic TEL-AML1 (ETV6-RUNX1) in umbilical cord blood samples.54,55,56,57,58 These findings are controversial, as the confirmation of a large number of positive cases has proven challenging.57,58 However, as a subset of positive cases was confirmed by breakpoint sequencing, at least 0.5% of the screened umbilical cord bloods of healthy newborns can be assumed to carry the TEL-AML1 translocation.56 This rate is markedly higher than the total cumulative incidence of pediatric acute lymphoblastic leukemia (0.07%), of which only 20%–25% of the patients are positive for TEL-AML1.63,64,65 Together, these results suggest that less than 3% of the newborns with detectable translocations eventually develop TEL-AML1-driven acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Thus, acquiring a leukemia-driving translocation is not sufficient for cancer initiation. An explanation for the lack of malignant transformation in newborns carrying oncogenic translocations is that the mutated cell is not a leukemia-initiating cell type. In multiple pediatric cancer types, including TEL-AML1-driven leukemia,62 malignant rhabdoid tumors,66 and Wilms tumors,67,68 cancer cells are likely arrested in an embryonic developmental state. The limited time window for oncogenic transformation due to a potential driver event may represent a rate-limiting factor for carcinogenesis in early life. Indeed, in mice, the cell type specificity of the initiating and second oncogenic hit is limited to the early development of hematopoietic cells.69 As the translocation is detected at low cellular frequencies, either in all cord-blood-derived mononuclear cells or its B cell compartment, it remains unclear in which (progenitor) cell the translocation arises.54,55,56,57,58 Despite enrichment in umbilical cord blood, the prevalence of hematopoietic stem cells is low (<1%), which hampers the detection of subclonal initiating driver events in this cellular compartment.70 Although single-nucleotide variants in fetal stem cells have an increased acquisition rate, systematic studies into the rate of de novo structural variant (SV) formation throughout life have been mostly lacking. Nevertheless, both adult and pediatric cancer samples harbor extensive structural rearrangements, and a large fraction of driver events is SVs.71,72,73 In the future, sequencing methods that enable SV discovery in single cells, such as SMOOTH-seq,74 scTRIP,75 and single-cell long-read sequencing,76 will likely provide more insights into the rates of SV formation and its relation to cancer incidence throughout development and life.

Classical twin studies have pointed toward a high penetrance of leukemia initiation when an initial oncogenic hit is present in a developing stem cell.77,78,79 In pediatric acute myeloid and lymphoid leukemia, twin studies have shown a concordance of 5%–25% overall, which is suspected to be increased even more in infant leukemia that originates in utero.77 It is hypothesized that in identical twins who share a single placenta, the cancer-initiating clone may be shared between the two fetuses, leading to the high concordance of leukemia. Large-scale, systematic studies are still lacking, but research into concordant and discordant pairs has shown that although initiating events occurred in a shared clone, the second hit is distinct or absent, respectively.78,79,80 Overall, an important rate-limiting step in the transformation is likely the occurrence of a second oncogenic hit. However, the high penetrance of concordant leukemia in twins suggests that in vivo, this requirement of a second hit is not a substantial impediment to leukemogenesis. Instead, the initial oncogenic mutation in the appropriate cell type is determinative for oncogenic transformation of pediatric cancer. Advances in single-cell genotyping techniques will allow more detailed research into cell-type-specific frequencies of oncogenic translocations to accurately determine the rate and transformative potential of an oncogenic hit in the cell of origin.

Postnatal mutation rates in adult stem cells

After birth, tissue-specific stem cells accumulate mutations in a linear fashion, although the mutation rate varies across tissues (Figures 3C and 3D).81,82 As indicated above, the mutation rate seems to be independent of the proliferation rate of tissue-specific stem cells. Even postmitotic neurons accumulate mutations at a constant rate throughout life in the absence of cell division. The lowest mutation rate in human tissues of 2.38 single base substitutions (SBSs) per year can be observed in seminiferous tubules, which are predominantly composed of germ cells.82,83 In somatic tissues, the lowest rate was observed in bile ductules (i.e., 9 SBSs per year) and the highest in intestinal crypts (i.e., ±50 SBSs per year).81,82 These rates have been estimated based on the results of sequencing analysis of microdissected clonal patches in normal human tissues. Reassuringly, rates estimated directly from tissue-specific stem cells are in a similar range, varying from 13 SBSs per year in satellite cells of skeletal muscle84 to 15–17 SBSs per year in HSPCs20,85,86 and up to 40 SBSs per year in liver and intestinal stem cells.18 These rates are remarkably low given that up to 105 DNA lesions are assumed to occur in an active mammalian cell on a daily basis.87 Stem cells are better safeguarded against the accumulation of DNA damage compared with differentiated cells. Their protection is owed to several stem-cell-specific features, such as quiescence, lower metabolic activity, and/or a protective niche.88 Low annual mutation rates observed in human tissues indicate that adult stem cells are well equipped to deal with the high levels of DNA damage they are confronted with. Nonetheless, considering the total number of stem cells in a human body, the combined mutational burden in the stem cell pool is high. For example, the human hematopoietic system contains 50,000–200,000 stem cells,19 each of which accumulate 15–17 SBSs per year.20,85,86 This means that in the hematopoietic stem cell pool over a lifetime (i.e., 80 years), 0.02%–0.1% of the haploid genome is mutated. In the colon, this number is even higher. A human colon has ∼107 crypts89 with multiple stem cells, in which one stem cell becomes dominant about every 5.5 years.24 If we take a crypt as a single stem cell unit, in the complete stem cell pool of the colon, about 1,200% of the haploid genome will be mutated over a lifetime. Although mutations do not accumulate in a random fashion across the genome90 and tissue architecture protects against oncogenic mutations and clonal outgrow of premalignant clones,91 the total mutational burden in the entire stem cell pool of the body and their progeny will be undeniably high.

Mutation accumulation alters competition between stem cells

Tissue heterogeneity driven by clonal dynamics

Although required, the estimated mutational burden in our body suggests that mutation accumulation is likely not a rate-limiting factor for carcinogenesis in childhood or adult life. However, cancer incidence is largely correlated with age and the background mutational load in stem cells.45,81,82 As mutations can confer competitive advantages that result in the development of cancer, mutation accumulation is required for carcinogenesis. Similarly, the use of stem cells in regenerative medicine might result in an increased cancer risk. For example, transplanted cells could harbor pre-existing oncogenic mutations.92,93 Alternatively, the extended lifespan of stem cells during in vitro culture and in vivo following transplantation will result in an increased mutational burden.94 However, the incidence of cancer, in particular leukemia and brain cancer, is higher in young children when compared with young adults, despite the lower mutational burden in younger cells (Figures 3D and 3F).45,95 This apparent paradox prompts the question of whether the background mutational load contributes to the selection dynamics within stem cell populations, especially at a young age.

Mutations that affect cell fitness either in development or homeostasis can lead to a competitive growth advantage and potentially clonal expansion. In addition, active cell competition eliminates “unfit” clones, for instance when aneuploid cells are depleted during development.96,97 During homeostasis, the size and complexity of a stem cell pool of homogeneous fitness need to be maintained. In the original model of a self-renewing stem cell at the apex of the lineage hierarchy, asymmetric cell divisions maintain the stem cell compartment and the production of differentiating progeny (Figure 4A).98 However, this original model has been challenged in different tissues.99,100,101 For example, in the intestinal stem cell compartment, cells of equal fitness compete for a limited niche space in a stochastic manner, termed neutral drift (Figure 4A).102,103 Stem cells that are pushed out of the intestinal crypt will differentiate, leading to a loss of self-renewal of that particular lineage.104 Neutral drift can lead to a gradual increase in clone size or loss of particular clones even in the absence of intrinsic differences in clone fitness.102,103 Similarly, larger clones can become apparent with age in the hematopoietic system. Often, clonal expansion cannot be explained by a genetic driver, but by neutral drift, which creates clones that become clinically detectable.105 At the extreme end of the contribution of neutral drift to clone size, clones can become extinct or dominant through a clonal sweep, which irreversibly alters the stem cell pool. Mutations that are neutral in homeostasis may confer a competitive advantage in another setting. Such mutations are preferably not fixed in the population due to a stochastic clonal sweep.

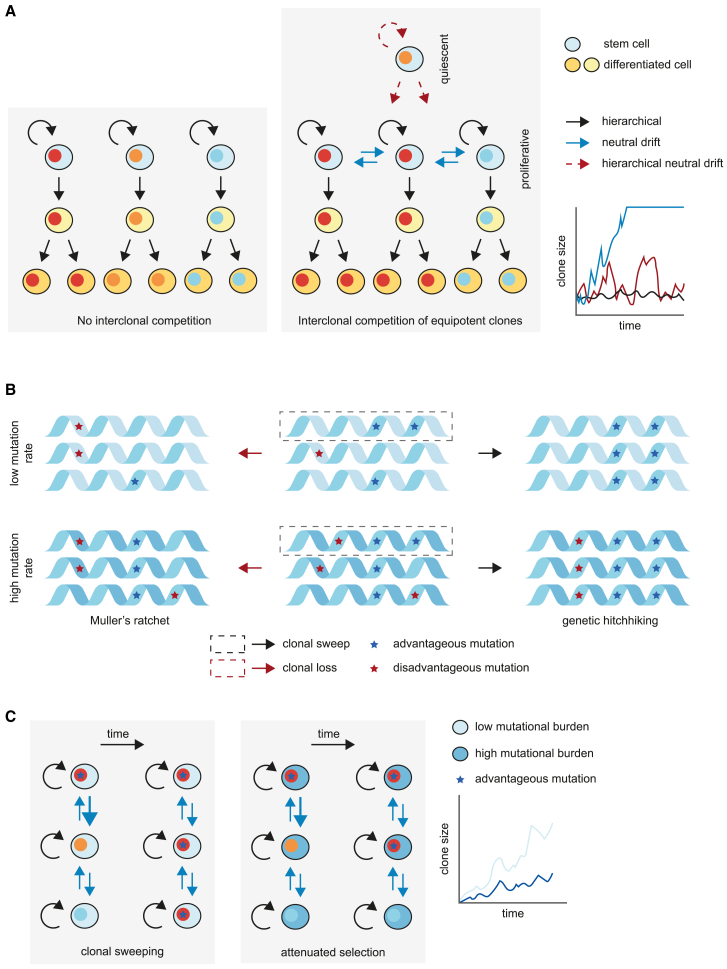

Figure 4.

The interplay between cellular competition and mutation accumulation in the stem cell compartment

(A) Models of regulation of clone size in the absence (left) or presence (center) of competition between stem cells, resulting in varying rates of clonal expansion between models (right).

(B) The accumulation of disadvantageous mutations in stem cells in a low (top) or high (bottom) mutation rate. Disadvantageous mutations (red) can become fixed in the stem cell compartment through Muller’s ratchet, when stochastic loss of the fittest clone results in a stem cell population where the remaining cells harbor disadvantageous mutations. Alternatively, advantageous mutations (blue) enable the genetic hitchhiking of disadvantageous variants.

(C) The rate of clonal expansion (right) due to an advantageous mutation (blue star) in a low mutational background (left) versus a high mutational background (center).

Multiple adaptations on the neutral drift model may prevent a pre-malignant clone from achieving clonal dominance. First, the existence of a quiescent stem cell population that occasionally feeds into the competitive, more actively cycling stem and progenitor cell compartment through infrequent proliferation (Figure 4A).106,107 In this multi-state model of stem cell competition, clones do not get extinguished as they can be re-seeded into the competitive stem cell compartment, thereby preventing complete dominance of a single clone in a tissue. Consequently, the size of the population that could potentially produce a malignant clone is kept limited, and clonal diversity is retained. Second, the aggregate of mutations within each cell affects the selection dynamics between clones.108 Despite a life-long accumulation of mutations in stem cells, a lack of negative selection of deleterious mutations is evident in tissue homeostasis and cancer.19,109,110 In somatic evolution, this phenomenon may be explained by the combination of two Hill-Robertson interference processes that lead to attenuated selection.111 The first is the genetic hitchhiking of advantageous and deleterious mutations through genetic linkage. The second is termed Muller’s ratchet, where the fittest clone is stochastically lost during genetic drift (Figure 4B). This process, in turn, fixes the second-fittest clone in the population, which likely harbors deleterious mutations that cannot be removed from the genome except by chromosomal aberrations.

The processes of genetic linkage and Muller’s ratchet are both increased in a high mutational background.112,113 Together, these phenomena result in the attenuated selection of individual driver events in a high mutational background, which will likely contain multiple deleterious passengers. This may contribute to the requirement of up to five driver events to achieve the competitive advantage necessary for clonal dominance (Figure 4C).108 Conversely, in a low mutational background, deleterious mutations are less likely to be present in the population and fewer drivers are required.108 The stem cell pool in young children is composed of cells likely to have more equal fitness compared with adult tissues, as they do not yet harbor deleterious characteristics that can attenuate the effect of a single driver mutation. However, it cannot be excluded that the developmental origin of childhood cancers or tissue-type-dependent differences alter the selection processes, thereby changing the type and number of drivers required for oncogenesis.62,66,67,68 In addition, some driver events may be more potent than others, such as MLL/KMT2A translocations in leukemia, which seem sufficient to drive oncogenesis.114,115 Nonetheless, the lack of deleterious background mutations in these younger children could likely increase the vulnerability of their stem cells to malignant transformation, which may contribute to the increased cancer incidence in this age group. In line with this theory, systematic studies of pediatric tumor genomes have revealed a lower mutational burden and a lower number of driver events compared with adult cancer.71,72 Overall, these studies point toward a model of stem cell hierarchy and competition where, counterintuitively, the accumulation of disadvantageous mutations in a heterogeneous stem cell pool creates a protective factor against carcinogenesis.

Clonality driven by (dis)advantageous mutations in healthy tissue

One of the surprising findings when studying somatic mutations in normal adult tissues is that tissues are often filled with clones, which harbor well-known cancer driver mutations.116 In the hematopoietic system, the presence of clonal expansions in the blood is associated with an increased hematologic cancer risk,117 which might pose an opportunity for early cancer detection. In addition, deep sequencing of a set of genes implicated in skin and other cancers revealed that sun-exposed eyelid epidermis is a patchwork of thousands of evolving clones.118 Using a similar approach, the same phenomenon could be observed in the esophagus.25,119 These clones were characterized by somatic mutations in key cancer genes, such as TP53 and NOTCH1. Although statistical approaches prove that these driver mutations have been positively selected and therefore likely underlie the clonal expansion of the parental cell, these studies raise the question of whether the presence of so many clones in these tissues directly increases the risk of cancer development. It is estimated that by middle age, more than 30% of the cells in a normal esophagus will harbor an inactivating mutation in the NOTCH1 gene, whereas this gene is mutated in 10% of the esophageal squamous cell carcinomas.25 One possibility could be that these driver mutations are not acquired in stem cells but in short-lived progenitors that act as transit amplifying cells. This explanation, although, is rather unlikely, as clonal expansions increase with age, suggesting that positively selected driver mutations are acquired in long-lived stem cells.

One approach to determine the cell of origin of clonal expansions in human tissues is to use somatic mutations and retrospectively trace clonal lineages.120 The clonal hierarchy of both cancer and normal tissues can be traced in this way.19,20,121 Especially passenger mutations (i.e., genetic variation without functional effects) are well suited for this, as these do not provide a selective advantage to a clone. The chance that such a mutation occurs independently in two different cells of the same donor is extremely small. In contrast, somatic mutations that confer a selective advantage can be acquired in multiple cells of the same individual through convergent evolution.122 Cells that share most mutations belong to the same genetic lineage and together make up a clone. This sharing of mutations in a population can occur through neutral drift, as observed in the intestinal crypt or because an oncogenic mutation provides a selective advantage to the clone.102,103 As for other tissues, the incidence of clonal hematopoiesis increases with age.105 Extensive phylogenetic trees of stem cell lineages clearly demonstrate that mutant clones underlying clonal hematopoiesis begin their expansion decades before clonal hematopoiesis is apparent.85 These mutant lineages display multilineage contributions to myeloid and lymphoid populations, indicating that the mutant parental cells were indeed multipotent stem cells.123

If many clones with positively selected mutations exist in our tissues, mutation accumulation in stem cells is unlikely to be the rate-limiting factor for carcinogenesis, at least in adults. As mentioned above, in the hematopoietic system of aged individuals, expanded clones can be observed that do not harbor any known driver mutation.85 Clonal hematopoiesis can even be observed in supercentenarians.124 Selection of specific premalignant clones due to environmental pressure is much more likely to be rate limiting. Some of the driver mutations have a higher frequency in normal tissues than in cancer, such as NOTCH1 mutations in the esophagus25,119,125 Some clonal mutations are even unique to noncancerous tissues, such as the FOXO1S22W mutation in cirrhotic liver, which is hardly found in hepatocellular carcinoma.126 This latter example supports the idea that altering selection pressure as a result of a changing environment might be rate limiting for carcinogenesis, at least in some cases, as chronic alcohol consumption, non-alcoholic fatty liver disease, and viral hepatitis are risk factors for liver cirrhosis. Overall, these studies reveal that clonal expansions are not necessarily a premalignant state. Additional research into specific mutations and their involvement in oncogenic transformation will provide more insights into the prognostic value of clonal expansions with and without such variants with respect to early cancer (risk) detection in the tissues of aging individuals.

Discussion

Despite the extensive genome maintenance programs present in stem cells, many potential driver mutations accumulate throughout life. However, the lifetime risk of developing cancer is less than 50%.127,128 Clearly, rate-limiting factors besides the protection of the genome are at play that prevent carcinogenesis. These factors may include the background rate of mutagenesis itself. An increased mutation rate is tolerated even during fetal development, a crucial time during which variants can become fixed in a large subset of the fetus’ future adult stem cells. Remarkably, prenatal coding mutations are more often predicted to be deleterious than postnatal coding mutations.40 This observation suggests that some variants, although deleterious in most settings, can be advantageous in developmental stages. Alternatively, the tolerance of an increased mutation rate may establish early phenotypic diversity and reduce the positive selection pressure of advantageous mutations.

Overall, a certain level of mutagenesis is tolerated during development and homeostasis and potentially even protective against clonal dominance of premalignant cells. This model of competition between stem cells can be translated to the use of stem cells in regenerative medicine, where the rate-limiting steps of carcinogenesis in vivo should be kept intact to prevent an increased cancer risk. The establishment and maintenance of a heterogeneous stem cell pool of similar fitness is of high importance to allow competition between stem cell clones, for instance, in normal human aging. Multiple factors should be considered to optimize the engraftment of a sufficient number of long-term stem cells in a transplant setting. First, the age of the donor: Long-term follow-up of recipients of HSPC transplantation showed engraftment of fewer stem cell clones when derived from older donors.123 A correlation also exists between increased donor age and reduced survival after HSPC transplantation.129,130 Second, the number of stem and progenitor cells that are infused has been correlated to the number of successfully engrafted stem cells.131 This outcome suggests that a higher number of cells should be infused for older donors to achieve engraftment of similar cell numbers as in younger donors. Third, the importance of phenotypic characterization of the stem cell pool used in a transplant setting can be observed in gene editing studies. The fraction of successfully genetically engineered cells after transplantation is lower than in the input stem cell pool, suggesting that long-term engrafting stem cells have been targeted less efficiently during genetic engineering.132

The combination of increased knowledge about stem cell markers, in vitro culture conditions, and genetic engineering of primary cells will likely contribute greatly to the long-term survival of recipients of stem cell therapies. For example, the long-term engraftment efficiency of HSPCs positive for primitive stem cell marker EPCR/CD201 was substantially increased, and optimized culture conditions have improved the enrichment of these particular cells.133,134,135 Still, these methods require in vitro culturing of stem cells, allowing culture-associated mutations to accumulate on top of the somatic mutations already present in the donor material. In iPSCs, the mutational burden per cell division is similar to the mutation rate of early embryonic cell divisions.42 However, the number of divisions of stem cells in culture will exceed the time window during which mutations are accumulated in development. Hematopoietic stem cells, for example, have acquired ±50 mutations at the time of birth, which will be exceeded within 40 days of culturing iPSCs.20,42 Reassuringly, estimations of the risk of inducing oncogenic mutations based on in vitro mutational spectra are similar to the in vivo risk of acquiring oncogenic mutations, despite the elevated mutation rates.94

Together, these studies suggest that a temporal elevation in the mutational rate of a pool of clonally diverse stem cells does not necessarily lead to an increased cancer risk. However, mutational screening of stem cells during a transplantation process may be clinically important, especially for tissues where extensive knowledge is available on the potential of driver mutations to induce malignant transformation of stem cells. Overall, as clonal dynamics between stem cells protect against the dominance of premalignant clones, future research into the selective pressures encountered during in vitro culture will show whether selection dynamics are similar to those in vivo.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Joske Ubels for insightful discussions. This work was supported by a grant from the European Research Council (ERC; no. 864499) and The New York Stem Cell Foundation. R.v.B. is a New York Stem Cell Foundation—Robertson Investigator.

Author contributions

L.L.M.D. and R.v.B. wrote and edited the manuscript.

Declaration of interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

References

- 1.Stratton M.R., Campbell P.J., Futreal P.A. The cancer genome. Nature. 2009;458:719–724. doi: 10.1038/nature07943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tomasetti C., Vogelstein B., Parmigiani G. Half or more of the somatic mutations in cancers of self-renewing tissues originate prior to tumor initiation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2013;110:1999–2004. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1221068110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tomasetti C., Vogelstein B. Cancer etiology. Variation in cancer risk among tissues can be explained by the number of stem cell divisions. Science. 2015;347:78–81. doi: 10.1126/science.1260825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rossi D.J., Jamieson C.H.M., Weissman I.L. Stems cells and the pathways to aging and cancer. Cell. 2008;132:681–696. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.01.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rozhok A.I., Wahl G.M., DeGregori J. A critical examination of the “bad luck” explanation of cancer risk. Cancer Prev. Res. (Phila) 2015;8:762–764. doi: 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-15-0229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wu S., Powers S., Zhu W., Hannun Y.A. Substantial contribution of extrinsic risk factors to cancer development. Nature. 2016;529:43–47. doi: 10.1038/nature16166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Barker N., Ridgway R.A., van Es J.H., van de Wetering M., Begthel H., van den Born M., Danenberg E., Clarke A.R., Sansom O.J., Clevers H. Crypt stem cells as the cells-of-origin of intestinal cancer. Nature. 2009;457:608–611. doi: 10.1038/nature07602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhu L., Finkelstein D., Gao C., Shi L., Wang Y., López-Terrada D., Wang K., Utley S., Pounds S., Neale G., et al. Multi-organ mapping of cancer risk. Cell. 2016;166:1132–1146.e7. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.07.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Friedmann-Morvinski D., Verma I.M. Dedifferentiation and reprogramming: origins of cancer stem cells. EMBO Rep. 2014;15:244–253. doi: 10.1002/embr.201338254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shlush L.I., Zandi S., Mitchell A., Chen W.C., Brandwein J.M., Gupta V., Kennedy J.A., Schimmer A.D., Schuh A.C., Yee K.W., et al. Identification of pre-leukaemic haematopoietic stem cells in acute leukaemia. Nature. 2014;506:328–333. doi: 10.1038/nature13038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vaux D.L. In defense of the somatic mutation theory of cancer. BioEssays. 2011;33:341–343. doi: 10.1002/bies.201100022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liggett L.A., DeGregori J. Changing mutational and adaptive landscapes and the genesis of cancer. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Rev. Cancer. 2017;1867:84–94. doi: 10.1016/j.bbcan.2017.01.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wong T.N., Ramsingh G., Young A.L., Miller C.A., Touma W., Welch J.S., Lamprecht T.L., Shen D., Hundal J., Fulton R.S., et al. Role of TP53 mutations in the origin and evolution of therapy-related acute myeloid leukaemia. Nature. 2015;518:552–555. doi: 10.1038/nature13968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bolton K.L., Ptashkin R.N., Gao T., Braunstein L., Devlin S.M., Kelly D., Patel M., Berthon A., Syed A., Yabe M., et al. Cancer therapy shapes the fitness landscape of clonal hematopoiesis. Nat. Genet. 2020;52:1219–1226. doi: 10.1038/s41588-020-00710-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hou Y., Song L., Zhu P., Zhang B., Tao Y., Xu X., Li F., Wu K., Liang J., Shao D., et al. Single-cell exome sequencing and monoclonal evolution of a JAK2-negative myeloproliferative neoplasm. Cell. 2012;148:873–885. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.02.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dong X., Zhang L., Milholland B., Lee M., Maslov A.Y., Wang T., Vijg J. Accurate identification of single-nucleotide variants in whole-genome-amplified single cells. Nat. Methods. 2017;14:491–493. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.4227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Welch J.S., Ley T.J., Link D.C., Miller C.A., Larson D.E., Koboldt D.C., Wartman L.D., Lamprecht T.L., Liu F., Xia J., et al. The origin and evolution of mutations in acute myeloid leukemia. Cell. 2012;150:264–278. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.06.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Blokzijl F., de Ligt J., Jager M., Sasselli V., Roerink S., Sasaki N., Huch M., Boymans S., Kuijk E., Prins P., et al. Tissue-specific mutation accumulation in human adult stem cells during life. Nature. 2016;538:260–264. doi: 10.1038/nature19768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lee-Six H., Øbro N.F., Shepherd M.S., Grossmann S., Dawson K., Belmonte M., Osborne R.J., Huntly B.J.P., Martincorena I., Anderson E., et al. Population dynamics of normal human blood inferred from somatic mutations. Nature. 2018;561:473–478. doi: 10.1038/s41586-018-0497-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Osorio F.G., Rosendahl Huber A., Oka R., Verheul M., Patel S.H., Hasaart K., de la Fonteijne L., Varela I., Camargo F.D., van Boxtel R. Somatic mutations reveal lineage relationships and age-related mutagenesis in human hematopoiesis. Cell Rep. 2018;25:2308–2316.e4. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2018.11.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yoshida K., Gowers K.H.C., Lee-Six H., Chandrasekharan D.P., Coorens T., Maughan E.F., Beal K., Menzies A., Millar F.R., Anderson E., et al. Tobacco smoking and somatic mutations in human bronchial epithelium. Nature. 2020;578:266–272. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-1961-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jager M., Blokzijl F., Sasselli V., Boymans S., Janssen R., Besselink N., Clevers H., van Boxtel R., Cuppen E. Measuring mutation accumulation in single human adult stem cells by whole-genome sequencing of organoid cultures. Nat. Protoc. 2018;13:59–78. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2017.111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rouhani F.J., Nik-Zainal S., Wuster A., Li Y., Conte N., Koike-Yusa H., Kumasaka N., Vallier L., Yusa K., Bradley A. Mutational history of a human cell lineage from somatic to induced pluripotent stem cells. PLoS Genetics. 2016;12:e1005932. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1005932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lee-Six H., Olafsson S., Ellis P., Osborne R.J., Sanders M.A., Moore L., Georgakopoulos N., Torrente F., Noorani A., Goddard M., et al. The landscape of somatic mutation in normal colorectal epithelial cells. Nature. 2019;574:532–537. doi: 10.1038/s41586-019-1672-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Martincorena I., Fowler J.C., Wabik A., Lawson A.R.J., Abascal F., Hall M.W.J., Cagan A., Murai K., Mahbubani K., Stratton M.R., et al. Somatic mutant clones colonize the human esophagus with age. Science. 2018;362:911–917. doi: 10.1126/science.aau3879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zong C., Lu S., Chapman A.R., Xie X.S. Genome-wide detection of single-nucleotide and copy-number variations of a single human cell. Science. 2012;338:1622–1626. doi: 10.1126/science.1229164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gonzalez-Pena V., Natarajan S., Xia Y., Klein D., Carter R., Pang Y., Shaner B., Annu K., Putnam D., Chen W., et al. Accurate genomic variant detection in single cells with primary template-directed amplification. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2021;118 doi: 10.1073/pnas.2024176118. e2024176118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Middelkamp S., Manders F., Peci F., van Roosmalen M.J., González D.M., Bertrums E.J.M., van der Werf I., Derks L.L.M., Groenen N.M., Verheul M., et al. Comprehensive single-cell genome analysis at nucleotide resolution using the PTA Analysis Toolbox. Cell Genomics. 2023;3:100389. doi: 10.1016/j.xgen.2023.100389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lodato M.A., Rodin R.E., Bohrson C.L., Coulter M.E., Barton A.R., Kwon M., Sherman M.A., Vitzthum C.M., Luquette L.J., Yandava C.N., et al. Aging and neurodegeneration are associated with increased mutations in single human neurons. Science. 2018;359:555–559. doi: 10.1126/science.aao4426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhang L., Dong X., Lee M., Maslov A.Y., Wang T., Vijg J. Single-cell whole-genome sequencing reveals the functional landscape of somatic mutations in B lymphocytes across the human lifespan. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2019;116:9014–9019. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1902510116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Luquette L.J., Miller M.B., Zhou Z., Bohrson C.L., Zhao Y., Jin H., Gulhan D., Ganz J., Bizzotto S., Kirkham S., et al. Single-cell genome sequencing of human neurons identifies somatic point mutation and indel enrichment in regulatory elements. Nat. Genet. 2022;54:1564–1571. doi: 10.1038/s41588-022-01180-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Abascal F., Harvey L.M.R., Mitchell E., Lawson A.R.J., Lensing S.V., Ellis P., Russell A.J.C., Alcantara R.E., Baez-Ortega A., Wang Y., et al. Somatic mutation landscapes at single-molecule resolution. Nature. 2021;593:405–410. doi: 10.1038/s41586-021-03477-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schmitt M.W., Kennedy S.R., Salk J.J., Fox E.J., Hiatt J.B., Loeb L.A. Detection of ultra-rare mutations by next-generation sequencing. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2012;109:14508–14513. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1208715109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Maslov A.Y., Makhortov S., Sun S., Heid J., Dong X., Lee M., Vijg J. Single-molecule, quantitative detection of low-abundance somatic mutations by high-throughput sequencing. Sci. Adv. 2022;8:eabm3259. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.abm3259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bae J.H., Liu R., Roberts E., Nguyen E., Tabrizi S., Rhoades J., Blewett T., Xiong K., Gydush G., Shea D., et al. Single duplex DNA sequencing with CODEC detects mutations with high sensitivity. Nat. Genet. 2023;55:871–879. doi: 10.1038/s41588-023-01376-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Park S., Mali N.M., Kim R., Choi J.W., Lee J., Lim J., Park J.M., Park J.W., Kim D., Kim T., et al. Clonal dynamics in early human embryogenesis inferred from somatic mutation. Nature. 2021;597:393–397. doi: 10.1038/s41586-021-03786-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hasaart K.A.L., Manders F., van der Hoorn M.L., Verheul M., Poplonski T., Kuijk E., de Sousa Lopes S.M.C., van Boxtel R. Mutation accumulation and developmental lineages in normal and Down syndrome human fetal haematopoiesis. Sci. Rep. 2020;10:12991. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-69822-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kuijk E., Blokzijl F., Jager M., Besselink N., Boymans S., Chuva de Sousa Lopes S.M., van Boxtel R., Cuppen E. Early divergence of mutational processes in human fetal tissues. Sci. Adv. 2019;5:eaaw1271. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.aaw1271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Spencer Chapman M., Ranzoni A.M., Myers B., Williams N., Coorens T.H.H., Mitchell E., Butler T., Dawson K.J., Hooks Y., Moore L., et al. Lineage tracing of human development through somatic mutations. Nature. 2021;595:85–90. doi: 10.1038/s41586-021-03548-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rockweiler N.B., Ramu A., Nagirnaja L., Wong W.H., Noordam M.J., Drubin C.W., Huang N., Miller B., Todres E.Z., Vigh-Conrad K.A., et al. The origins and functional effects of postzygotic mutations throughout the human life span. Science. 2023;380:eabn7113. doi: 10.1126/science.abn7113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ju Y.S., Martincorena I., Gerstung M., Petljak M., Alexandrov L.B., Rahbari R., Wedge D.C., Davies H.R., Ramakrishna M., Fullam A., et al. Somatic mutations reveal asymmetric cellular dynamics in the early human embryo. Nature. 2017;543:714–718. doi: 10.1038/nature21703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hasaart K.A.L., Manders F., Ubels J., Verheul M., van Roosmalen M.J., Groenen N.M., Oka R., Kuijk E., Lopes S.M.C.S., van Boxtel R.V. Human induced pluripotent stem cells display a similar mutation burden as embryonic pluripotent cells in vivo. iScience. 2022;25:103736. doi: 10.1016/j.isci.2022.103736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Schulz K.N., Harrison M.M. Mechanisms regulating zygotic genome activation. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2019;20:221–234. doi: 10.1038/s41576-018-0087-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bae T., Tomasini L., Mariani J., Zhou B., Roychowdhury T., Franjic D., Pletikos M., Pattni R., Chen B.J., Venturini E., et al. Different mutational rates and mechanisms in human cells at pregastrulation and neurogenesis. Science. 2018;359:550–555. doi: 10.1126/science.aan8690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Surveillance Research Program. National Cancer Institute . 2019. SEER∗Explorer: an interactive website for SEER cancer statistics.https://seer.cancer.gov/statistics-network/explorer/ Internet. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cao W., Chen K., Bolkestein M., Yin Y., Verstegen M.M.A., Bijvelds M.J.C., Wang W., Tuysuz N., ten Berge D., Sprengers D., et al. Dynamics of proliferative and quiescent stem cells in liver homeostasis and injury. Gastroenterology. 2017;153:1133–1147. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2017.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Basak O., van de Born M., Korving J., Beumer J., van der Elst S., van Es J.H., Clevers H. Mapping early fate determination in Lgr5+ crypt stem cells using a novel Ki67-RFP allele. EMBO J. 2014;33:2057–2068. doi: 10.15252/embj.201488017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Colaco S., Sakkas D. Paternal factors contributing to embryo quality. J. Assist. Reprod. Genet. 2018;35:1953–1968. doi: 10.1007/s10815-018-1304-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Palmer N., Kaldis P. Regulation of the embryonic cell cycle during mammalian preimplantation development. Curr. Top. Dev. Biol. 2016;120:1–53. doi: 10.1016/bs.ctdb.2016.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.McCoy R.C. Mosaicism in preimplantation human embryos: when chromosomal abnormalities are the norm. Trends Genet. 2017;33:448–463. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2017.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Vázquez-Diez C., FitzHarris G. Causes and consequences of chromosome segregation error in preimplantation embryos. Reproduction. 2018;155:R63–R76. doi: 10.1530/REP-17-0569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Vitale I., Manic G., De Maria R., Kroemer G., Galluzzi L. DNA damage in stem cells. Mol. Cell. 2017;66:306–319. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2017.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Bloom J.C., Loehr A.R., Schimenti J.C., Weiss R.S. Germline genome protection: implications for gamete quality and germ cell tumorigenesis. Andrology. 2019;7:516–526. doi: 10.1111/andr.12651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Mori H., Colman S.M., Xiao Z., Ford A.M., Healy L.E., Donaldson C., Hows J.M., Navarrete C., Greaves M. Chromosome translocations and covert leukemic clones are generated during normal fetal development. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2002;99:8242–8247. doi: 10.1073/pnas.112218799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Zuna J., Madzo J., Krejci O., Zemanova Z., Kalinova M., Muzikova K., Zapotocky M., Starkova J., Hrusak O., Horak J., et al. ETV6/RUNX1 (TEL/AML1) is a frequent prenatal first hit in childhood leukemia. Blood. 2011;117:368–369. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-09-309070. author reply 370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Schäfer D., Olsen M., Lähnemann D., Stanulla M., Slany R., Schmiegelow K., Borkhardt A., Fischer U. Five percent of healthy newborns have an ETV6-RUNX1 fusion as revealed by DNA-based GIPFEL screening. Blood. 2018;131:821–826. doi: 10.1182/blood-2017-09-808402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Škorvaga M., Nikitina E., Kubeš M., Košík P., Gajdošechová B., Leitnerová M., Copáková L., Belyaev I. Incidence of common preleukemic gene fusions in umbilical cord blood in Slovak population. PLoS One. 2014;9:e91116. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0091116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lausten-Thomsen U., Madsen H.O., Vestergaard T.R., Hjalgrim H., Nersting J., Schmiegelow K. Prevalence of t(12;21)[ETV6-RUNX1]–positive cells in healthy neonates. Blood. 2011;117:186–189. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-05-282764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wang Y., Wu N., Liu D., Jin Y. Recurrent fusion genes in leukemia: an attractive target for diagnosis and treatment. Curr. Genomics. 2017;18:378–384. doi: 10.2174/1389202918666170329110349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.van Belzen I.A.E.M., Cai C., van Tuil M., Badloe S., Strengman E., Janse A., Verwiel E.T.P., van der Leest D.F.M., Kester L., Molenaar J.J., et al. Systematic discovery of gene fusions in pediatric cancer by integrating RNA-seq and WGS. BMC Cancer. 2023;23:618. doi: 10.1186/s12885-023-11054-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ueno H., Yoshida K., Shiozawa Y., Nannya Y., Iijima-Yamashita Y., Kiyokawa N., Shiraishi Y., Chiba K., Tanaka H., Isobe T., et al. Landscape of driver mutations and their clinical impacts in pediatric B-cell precursor acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Blood Adv. 2020;4:5165–5173. doi: 10.1182/bloodadvances.2019001307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Greaves M. A causal mechanism for childhood acute lymphoblastic leukaemia. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2018;18:471–484. doi: 10.1038/s41568-018-0015-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Erdmann F., Kaatsch P., Grabow D., Spix C. German Childhood Cancer Registry - annual report 2019 (1980–2018). Institute of Medical Biostatistics, Epidemiology and Informatics [IMBEI] at the University Medical Center of the Johannes Gutenberg University Mainz; 2020. https://www.kinderkrebsregister.de/dkkr-gb/latest-publications/annual-reports.html?L=1

- 64.Romana S.P., Poirel H., Leconiat M., Flexor M.A., Mauchauffé M., Jonveaux P., Macintyre E.A., Berger R., Bernard O.A. High frequency of t(12;21) in childhood B-lineage acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Blood. 1995;86:4263–4269. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Loh M.L., Goldwasser M.A., Silverman L.B., Poon W.M., Vattikuti S., Cardoso A., Neuberg D.S., Shannon K.M., Sallan S.E., Gilliland D.G. Prospective analysis of TEL/AML1-positive patients treated on Dana-Farber Cancer Institute Consortium Protocol 95-01. Blood. 2006;107:4508–4513. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-08-3451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Custers L., Khabirova E., Coorens T.H.H., Oliver T.R.W., Calandrini C., Young M.D., Vieira Braga F.A., Ellis P., Mamanova L., Segers H., et al. Somatic mutations and single-cell transcriptomes reveal the root of malignant rhabdoid tumours. Nat. Commun. 2021;12:1407. doi: 10.1038/s41467-021-21675-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Treger T.D., Chowdhury T., Pritchard-Jones K., Behjati S. The genetic changes of Wilms tumour. Nat. Rev. Nephrol. 2019;15:240–251. doi: 10.1038/s41581-019-0112-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Coorens T.H.H., Treger T.D., Al-Saadi R., Moore L., Tran M.G.B., Mitchell T.J., Tugnait S., Thevanesan C., Young M.D., Oliver T.R.W., et al. Embryonal precursors of Wilms tumor. Science. 2019;366:1247–1251. doi: 10.1126/science.aax1323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Rodríguez-Hernández G., Casado-García A., Isidro-Hernández M., Picard D., Raboso-Gallego J., Alemán-Arteaga S., Orfao A., Blanco O., Riesco S., Prieto-Matos P., et al. The second oncogenic hit determines the cell fate of ETV6-RUNX1 positive leukemia. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2021;9:704591. doi: 10.3389/fcell.2021.704591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Notta F., Doulatov S., Laurenti E., Poeppl A., Jurisica I., Dick J.E. Isolation of single human hematopoietic stem cells capable of long-term multilineage engraftment. Science. 2011;333:218–221. doi: 10.1126/science.1201219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Ma X., Liu Y., Liu Y., Alexandrov L.B., Edmonson M.N., Gawad C., Zhou X., Li Y., Rusch M.C., Easton J., et al. Pan-cancer genome and transcriptome analyses of 1,699 paediatric leukaemias and solid tumours. Nature. 2018;555:371–376. doi: 10.1038/nature25795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Gröbner S.N., Worst B.C., Weischenfeldt J., Buchhalter I., Kleinheinz K., Rudneva V.A., Johann P.D., Balasubramanian G.P., Segura-Wang M., Brabetz S., et al. The landscape of genomic alterations across childhood cancers. Nature. 2018;555:321–327. doi: 10.1038/nature25480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.ICGC/TCGA Pan-Cancer Analysis of Whole Genomes Consortium Pan-cancer analysis of whole genomes. Nature. 2020;578:82–93. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-1969-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Fan X., Yang C., Li W., Bai X., Zhou X., Xie H., Wen L., Tang F. SMOOTH-seq: single-cell genome sequencing of human cells on a third-generation sequencing platform. Genome Biol. 2021;22:195. doi: 10.1186/s13059-021-02406-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Sanders A.D., Meiers S., Ghareghani M., Porubsky D., Jeong H., van Vliet M.A.C.C., Rausch T., Richter-Pechańska P., Kunz J.B., Jenni S., et al. Single-cell analysis of structural variations and complex rearrangements with tri-channel processing. Nat. Biotechnol. 2020;38:343–354. doi: 10.1038/s41587-019-0366-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Hård J., Mold J.E., Eisfeldt J., Tellgren-Roth C., Häggqvist S., Bunikis I., Contreras-Lopez O., Chin C.S., Nordlund J., Rubin C.J., et al. Long-read whole-genome analysis of human single cells. Nat. Commun. 2023;14:5164. doi: 10.1038/s41467-023-40898-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Greaves M.F., Maia A.T., Wiemels J.L., Ford A.M. Leukemia in twins: lessons in natural history. Blood. 2003;102:2321–2333. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-12-3817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Alpar D., Wren D., Ermini L., Mansur M.B., van Delft F.W., Bateman C.M., Titley I., Kearney L., Szczepanski T., Gonzalez D., et al. Clonal origins of ETV6-RUNX1+ acute lymphoblastic leukemia: studies in monozygotic twins. Leukemia. 2015;29:839–846. doi: 10.1038/leu.2014.322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Ford A.M., Colman S., Greaves M. Covert pre-leukaemic clones in healthy co-twins of patients with childhood acute lymphoblastic leukaemia. Leukemia. 2023;37:47–52. doi: 10.1038/s41375-022-01756-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Cazzaniga G., van Delft F.W., Lo Nigro L., Ford A.M., Score J., Iacobucci I., Mirabile E., Taj M., Colman S.M., Biondi A., et al. Developmental origins and impact of BCR-ABL1 fusion and IKZF1 deletions in monozygotic twins with Ph+ acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Blood. 2011;118:5559–5564. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-07-366542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Manders F., van Boxtel R., Middelkamp S. The dynamics of somatic mutagenesis during life in humans. Front. Aging. 2021;2:802407. doi: 10.3389/fragi.2021.802407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Moore L., Cagan A., Coorens T.H.H., Neville M.D.C., Sanghvi R., Sanders M.A., Oliver T.R.W., Leongamornlert D., Ellis P., Noorani A., et al. The mutational landscape of human somatic and germline cells. Nature. 2021;597:381–386. doi: 10.1038/s41586-021-03822-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Kong A., Frigge M.L., Masson G., Besenbacher S., Sulem P., Magnusson G., Gudjonsson S.A., Sigurdsson A., Jonasdottir A., Jonasdottir A., et al. Rate of de novo mutations and the importance of father’s age to disease risk. Nature. 2012;488:471–475. doi: 10.1038/nature11396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Franco I., Johansson A., Olsson K., Vrtačnik P., Lundin P., Helgadottir H.T., Larsson M., Revêchon G., Bosia C., Pagnani A., et al. Somatic mutagenesis in satellite cells associates with human skeletal muscle aging. Nat. Commun. 2018;9:800. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-03244-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Mitchell E., Spencer Chapman M., Williams N., Dawson K.J., Mende N., Calderbank E.F., Jung H., Mitchell T., Coorens T.H.H., Spencer D.H., et al. Clonal dynamics of haematopoiesis across the human lifespan. Nature. 2022;606:343–350. doi: 10.1038/s41586-022-04786-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Brandsma A.M., Bertrums E.J.M., van Roosmalen M.J., Hofman D.A., Oka R., Verheul M., Manders F., Ubels J., Belderbos M.E., van Boxtel R. Mutation signatures of pediatric acute myeloid leukemia and normal blood progenitors associated with differential patient outcomes. Blood Cancer Discov. 2021;2:484–499. doi: 10.1158/2643-3230.BCD-21-0010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Lindahl T. Instability and decay of the primary structure of DNA. Nature. 1993;362:709–715. doi: 10.1038/362709a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Mandal P.K., Blanpain C., Rossi D.J. DNA damage response in adult stem cells: pathways and consequences. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2011;12:198–202. doi: 10.1038/nrm3060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Frank S.A., Nowak M.A. Problems of somatic mutation and cancer. BioEssays. 2004;26:291–299. doi: 10.1002/bies.20000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Schuster-Böckler B., Lehner B. Chromatin organization is a major influence on regional mutation rates in human cancer cells. Nature. 2012;488:504–507. doi: 10.1038/nature11273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Vermeulen L., Morrissey E., van der Heijden M., Nicholson A.M., Sottoriva A., Buczacki S., Kemp R., Tavaré S., Winton D.J. Defining stem cell dynamics in models of intestinal tumor initiation. Science. 2013;342:995–998. doi: 10.1126/science.1243148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Hsu J.I., Dayaram T., Tovy A., De Braekeleer E.D., Jeong M., Wang F., Zhang J., Heffernan T.P., Gera S., Kovacs J.J., et al. PPM1D mutations drive clonal hematopoiesis in response to cytotoxic chemotherapy. Cell Stem Cell. 2018;23:700–713.e6. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2018.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Wong T.N., Miller C.A., Jotte M.R.M., Bagegni N., Baty J.D., Schmidt A.P., Cashen A.F., Duncavage E.J., Helton N.M., Fiala M., et al. Cellular stressors contribute to the expansion of hematopoietic clones of varying leukemic potential. Nat. Commun. 2018;9:455. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-02858-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Kuijk E., Jager M., van der Roest B., Locati M.D., Van Hoeck A., Korzelius J., Janssen R., Besselink N., Boymans S., van Boxtel R., et al. The mutational impact of culturing human pluripotent and adult stem cells. Nat. Commun. 2020;11:2493. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-16323-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Arora R.S., Alston R.D., Eden T.O.B., Estlin E.J., Moran A., Birch J.M. Age–incidence patterns of primary CNS tumors in children, adolescents, and adults in England. Neuro. Oncol. 2009;11:403–413. doi: 10.1215/15228517-2008-097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Traulsen A., Lenaerts T., Pacheco J.M., Dingli D. On the dynamics of neutral mutations in a mathematical model for a homogeneous stem cell population. J. R. Soc. Interface. 2013;10:20120810. doi: 10.1098/rsif.2012.0810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.van Neerven S.M., Vermeulen L. Cell competition in development, homeostasis and cancer. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2023;24:221–236. doi: 10.1038/s41580-022-00538-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Greulich P., MacArthur B.D., Parigini C., Sánchez-García R.J. Universal principles of lineage architecture and stem cell identity in renewing tissues. Development. 2021;148:dev194399. doi: 10.1242/dev.194399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Vermeulen L., Snippert H.J. Stem cell dynamics in homeostasis and cancer of the intestine. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2014;14:468–480. doi: 10.1038/nrc3744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Simons B.D., Clevers H. Strategies for homeostatic stem cell self-renewal in adult tissues. Cell. 2011;145:851–862. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.05.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Klein A.M., Simons B.D. Universal patterns of stem cell fate in cycling adult tissues. Development. 2011;138:3103–3111. doi: 10.1242/dev.060103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Snippert H.J., van der Flier L.G., Sato T., van Es J.H., van den Born M., Kroon-Veenboer C., Barker N., Klein A.M., van Rheenen J., Simons B.D., et al. Intestinal crypt homeostasis results from neutral competition between symmetrically dividing Lgr5 stem cells. Cell. 2010;143:134–144. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Lopez-Garcia C., Klein A.M., Simons B.D., Winton D.J. Intestinal stem cell replacement follows a pattern of neutral drift. Science. 2010;330:822–825. doi: 10.1126/science.1196236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Ritsma L., Ellenbroek S.I.J., Zomer A., Snippert H.J., de Sauvage F.J., Simons B.D., Clevers H., van Rheenen J. Intestinal crypt homeostasis revealed at single-stem-cell level by in vivo live imaging. Nature. 2014;507:362–365. doi: 10.1038/nature12972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Zink F., Stacey S.N., Norddahl G.L., Frigge M.L., Magnusson O.T., Jonsdottir I., Thorgeirsson T.E., Sigurdsson A., Gudjonsson S.A., Gudmundsson J., et al. Clonal hematopoiesis, with and without candidate driver mutations, is common in the elderly. Blood. 2017;130:742–752. doi: 10.1182/blood-2017-02-769869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Nakamuta A., Yoshido K., Naoki H. Stem cell homeostasis regulated by hierarchy and neutral competition. Commun. Biol. 2022;5:1268. doi: 10.1038/s42003-022-04218-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Xu S., Kim S., Chen I.S.Y., Chou T. Modeling large fluctuations of thousands of clones during hematopoiesis: the role of stem cell self-renewal and bursty progenitor dynamics in rhesus macaque. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2018;14:e1006489. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1006489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Tilk S., Tkachenko S., Curtis C., Petrov D.A., McFarland C.D. Most cancers carry a substantial deleterious load due to Hill-Robertson interference. eLife. 2022;11:e67790. doi: 10.7554/eLife.67790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Martincorena I., Raine K.M., Gerstung M., Dawson K.J., Haase K., Van Loo P., Davies H., Stratton M.R., Campbell P.J. Universal patterns of selection in cancer and somatic tissues. Cell. 2017;171:1029–1041.e21. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2017.09.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Weghorn D., Sunyaev S. Bayesian inference of negative and positive selection in human cancers. Nat. Genet. 2017;49:1785–1788. doi: 10.1038/ng.3987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Hill W.G., Robertson A. The effect of linkage on limits to artificial selection. Genet. Res. 1966;8:269–294. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Johnson T. Beneficial mutations, hitchhiking and the evolution of mutation rates in sexual populations. Genetics. 1999;151:1621–1631. doi: 10.1093/genetics/151.4.1621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Neher R.A., Shraiman B.I. Fluctuations of fitness distributions and the rate of Muller’s ratchet. Genetics. 2012;191:1283–1293. doi: 10.1534/genetics.112.141325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Bill M., Mrózek K., Kohlschmidt J., Eisfeld A.K., Walker C.J., Nicolet D., Papaioannou D., Blachly J.S., Orwick S., Carroll A.J., et al. Mutational landscape and clinical outcome of patients with de novo acute myeloid leukemia and rearrangements involving 11q23/KMT2A. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2020;117:26340–26346. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2014732117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Andersson A.K., Ma J., Wang J., Chen X., Gedman A.L., Dang J., Nakitandwe J., Holmfeldt L., Parker M., Easton J., et al. The landscape of somatic mutations in infant MLL-rearranged acute lymphoblastic leukemias. Nat. Genet. 2015;47:330–337. doi: 10.1038/ng.3230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Kakiuchi N., Ogawa S. Clonal expansion in non-cancer tissues. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2021;21:239–256. doi: 10.1038/s41568-021-00335-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Genovese G., Kähler A.K., Handsaker R.E., Lindberg J., Rose S.A., Bakhoum S.F., Chambert K., Mick E., Neale B.M., Fromer M., et al. Clonal hematopoiesis and blood-cancer risk inferred from blood DNA sequence. N. Engl. J. Med. 2014;371:2477–2487. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1409405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Martincorena I., Roshan A., Gerstung M., Ellis P., Van Loo P., McLaren S., Wedge D.C., Fullam A., Alexandrov L.B., Tubio J.M., et al. Tumor evolution. High burden and pervasive positive selection of somatic mutations in normal human skin. Science. 2015;348:880–886. doi: 10.1126/science.aaa6806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Yokoyama A., Kakiuchi N., Yoshizato T., Nannya Y., Suzuki H., Takeuchi Y., Shiozawa Y., Sato Y., Aoki K., Kim S.K., et al. Age-related remodelling of oesophageal epithelia by mutated cancer drivers. Nature. 2019;565:312–317. doi: 10.1038/s41586-018-0811-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Kester L., van Oudenaarden A. Single-cell transcriptomics meets lineage tracing. Cell Stem Cell. 2018;23:166–179. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2018.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Roerink S.F., Sasaki N., Lee-Six H., Young M.D., Alexandrov L.B., Behjati S., Mitchell T.J., Grossmann S., Lightfoot H., Egan D.A., et al. Intra-tumour diversification in colorectal cancer at the single-cell level. Nature. 2018;556:457–462. doi: 10.1038/s41586-018-0024-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Gerlinger M., Rowan A.J., Horswell S., Math M., Larkin J., Endesfelder D., Gronroos E., Martinez P., Matthews N., Stewart A., et al. Intratumor heterogeneity and branched evolution revealed by multiregion sequencing. N. Engl. J. Med. 2012;366:883–892. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1113205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Spencer Chapman M., Wilk M., Boettcher S., Campbell P. 2023. Clonal dynamics after allogeneic haematopoietic cell transplantation using genome-wide somatic mutations. Preprint at Research Square. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Holstege H., Pfeiffer W., Sie D., Hulsman M., Nicholas T.J., Lee C.C., Ross T., Lin J., Miller M.A., Ylstra B., et al. Somatic mutations found in the healthy blood compartment of a 115-yr-old woman demonstrate oligoclonal hematopoiesis. Genome Res. 2014;24:733–742. doi: 10.1101/gr.162131.113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Martincorena I. Somatic mutation and clonal expansions in human tissues. Genome Med. 2019;11:35. doi: 10.1186/s13073-019-0648-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Ng S.W.K., Rouhani F.J., Brunner S.F., Brzozowska N., Aitken S.J., Yang M., Abascal F., Moore L., Nikitopoulou E., Chappell L., et al. Convergent somatic mutations in metabolism genes in chronic liver disease. Nature. 2021;598:473–478. doi: 10.1038/s41586-021-03974-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Cancer Research UK (2018). Lifetime risk of cancer https://www.cancerresearchuk.org/health-professional/cancer-statistics/risk/lifetime-risk

- 128.American Cancer Society . 2023. Lifetime probability of developing and dying from cancer, 2017–2019.https://www.cancer.org/content/dam/cancer-org/research/cancer-facts-and-statistics/annual-cancer-facts-and-figures/2023/sd4-lifetime-probability-2023-cff.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 129.Kollman C., Howe C.W., Anasetti C., Antin J.H., Davies S.M., Filipovich A.H., Hegland J., Kamani N., Kernan N.A., King R., et al. Donor characteristics as risk factors in recipients after transplantation of bone marrow from unrelated donors: the effect of donor age. Blood. 2001;98:2043–2051. doi: 10.1182/blood.v98.7.2043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Kollman C., Spellman S.R., Zhang M.J., Hassebroek A., Anasetti C., Antin J.H., Champlin R.E., Confer D.L., DiPersio J.F., Fernandez-Viña M., et al. The effect of donor characteristics on survival after unrelated donor transplantation for hematologic malignancy. Blood. 2016;127:260–267. doi: 10.1182/blood-2015-08-663823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Six E., Guilloux A., Denis A., Lecoules A., Magnani A., Vilette R., Male F., Cagnard N., Delville M., Magrin E., et al. Clonal tracking in gene therapy patients reveals a diversity of human hematopoietic differentiation programs. Blood. 2020;135:1219–1231. doi: 10.1182/blood.2019002350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Sharma A., Boelens J.J., Cancio M., Hankins J.S., Bhad P., Azizy M., Lewandowski A., Zhao X., Chitnis S., Peddinti R., et al. CRISPR-Cas9 editing of the HBG1 and HBG2 promoters to treat sickle cell disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 2023;389:820–832. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2215643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Becker H.J., Ishida R., Wilkinson A.C., Kimura T., Lee M.S.J., Coban C., Ota Y., Tanaka Y., Roskamp M., Sano T., et al. Controlling genetic heterogeneity in gene-edited hematopoietic stem cells by single-cell expansion. Cell Stem Cell. 2023;30:987–1000.e8. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2023.06.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Anjos-Afonso F., Buettner F., Mian S.A., Rhys H., Perez-Lloret J., Garcia-Albornoz M., Rastogi N., Ariza-McNaughton L., Bonnet D. Single cell analyses identify a highly regenerative and homogenous human CD34+ hematopoietic stem cell population. Nat. Commun. 2022;13:2048. doi: 10.1038/s41467-022-29675-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Sakurai M., Ishitsuka K., Ito R., Wilkinson A.C., Kimura T., Mizutani E., Nishikii H., Sudo K., Becker H.J., Takemoto H., et al. Chemically defined cytokine-free expansion of human haematopoietic stem cells. Nature. 2023;615:127–133. doi: 10.1038/s41586-023-05739-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]