Abstract

A dynamic dilution system for producing low mixing ratios of methyl bromide (MeBr) and a sensitive analytical technique were used to study the uptake of MeBr by various soils. MeBr was removed within minutes from vials incubated with soils and ∼10 parts per billion by volume of MeBr. Killed controls did not consume MeBr, and a mixture of the broad-spectrum antibiotics chloramphenicol and tetracycline inhibited MeBr uptake by 98%, indicating that all of the uptake of MeBr was biological and by bacteria. Temperature optima for MeBr uptake suggested a biological sink, yet soil moisture and temperature optima varied for different soils, implying that MeBr consumption activity by soil bacteria is diverse. The eucaryotic antibiotic cycloheximide had no effect on MeBr uptake, indicating that soil fungi were not involved in MeBr removal. MeBr consumption did not occur anaerobically. A dynamic flowthrough vial system was used to incubate soils at MeBr mixing ratios as low as those found in the remote atmosphere (5 to 15 parts per trillion by volume [pptv]). Soils consumed MeBr at all mixing ratios tested. Temperate forest and grassy lawn soils consumed MeBr most rapidly (rate constant [k] = 0.5 min−1), yet sandy temperate, boreal, and tropical forest soils also readily consumed MeBr. Amendments of CH4 up to 5% had no effect on MeBr uptake even at CH4:MeBr ratios of 107, and depth profiles of MeBr and CH4 consumption exhibited very different vertical rate optima, suggesting that methanotrophic bacteria, like those presently in culture, do not utilize MeBr when it is at atmospheric mixing ratios. Data acquired with gas flux chambers in the field demonstrated the very rapid in situ consumption of MeBr by soils. Uptake of MeBr at mixing ratios found in the remote atmosphere occurs via aerobic bacterial activity, displays first-order kinetics at mixing ratios from 5 pptv to ∼1 part per million per volume, and is rapid enough to account for 25% of the global annual loss of atmospheric MeBr.

Methyl bromide (MeBr) is a widely used fumigant in crop production and commodity preservation worldwide. MeBr has been recognized as a major source of stratospheric bromine (11, 22), which is important in the destruction of ozone and subsequent elimination of the Earth’s ozone layer. Bromine may be up to 100 times more effective than chlorine in its capacity to destroy stratospheric ozone (25). The degree to which MeBr released in the lower atmosphere migrates to the stratosphere and releases Br to catalyze ozone destruction is directly proportional to its tropospheric lifetime (11, 22). This lifetime is influenced by the rate at which MeBr reacts with hydroxyl radicals in the troposphere, the rate at which it is absorbed into undersaturated surface waters, and the rate of its destructive uptake into soil and/or vegetation surfaces. While the first loss term is reasonably well known (11), and recent data have indicated that the open ocean is undersaturated with respect to MeBr and, hence, a sink (9, 28), there are few reliable data to allow an estimate of the third term. About half or more of the MeBr applied to agricultural soils is released into the atmosphere, with the remainder degraded in the soil (27). However, soil bacteria are capable of utilizing MeBr at levels present in the remote atmosphere, indicating that soils are a significant sink at the global level (21).

MeBr can be consumed by whole cells and cell extracts of methanotrophic bacteria (16). Consumption is coupled to O2 consumption, and it appears that methane monooxygenase is involved (1, 2, 13). Nitrifying bacteria have also been shown to consume MeBr via ammonia monooxygenase (20), and additions of ammonia fertilizers stimulate MeBr consumption by agricultural soils (19). MeBr is also consumed by anaerobic sediments by a nucleophilic substitution with sulfide which produces methylated S gases (17). Oremland et al. (16) reported the consumption of MeBr by soils incubated in the laboratory and the removal of MeBr in chambers placed over soils in the field. Their experiments with methane additions and the use of methyl fluoride inhibition suggested that at least a portion of the MeBr consumption by aerobic soils was conducted by methanotrophic bacteria. However, their experiments and others (26, 27) were conducted with MeBr mixing ratios which were orders of magnitude above ambient atmospheric levels. We developed an analytical system capable of measuring MeBr at ambient levels (5 to 10 parts per trillion by volume [pptv]) (8), and we report here the rapid consumption of low mixing ratios of MeBr by soil microflora.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Sampling sites.

Two types of soils used for the bulk of the experiments were collected in southern New Hampshire, a forest soil located in College Woods in Durham (3) and an agricultural soil in a corn field at the University of New Hampshire. Most of the experiments were conducted with forest soils situated below the surficial litter layer. The moisture content of the forest soil, as weight percent, was approximately 60% in the 0- to 3-cm horizon below the litter, 42% at 3 to 7 cm, and 30% at 10 to 15 cm. The organic-matter contents of these same layers, as weight percent, were approximately 60, 22, and 8.5%, respectively. The surficial corn field soils had moisture and organic contents of approximately 12 and 9%, respectively. Cores of forest soil were used to obtain samples to investigate MeBr uptake with respect to depth. MeBr uptake was also determined with incubations of a surficial boreal sandy forest soil from Manitoba (12% moisture, 5% organic) and a surficial subtropical soil from Costa Rica (38% moisture, 25% organic). Experiments with the New Hampshire forest and corn field soils were conducted on the day that soils were collected. The foreign soils were used several days after collection. We did not determine if prolonged storage affected results.

Experiments with static serum vials.

Soils (5 to 10 g) were added to 150-ml serum vials which were sealed with thick blue butyl rubber septa and crimps. MeBr at various mixing ratios was obtained with a dynamic dilution system (8) and added with syringes. In most cases reported here, we added MeBr to a final headspace mixing ratio of ∼10 parts per billion by volume (ppbv). To maintain MeBr at low mixing ratios in serum vials, we sacrificed separate duplicate vials at each point in a time course by sweeping the entire headspace through a cold trap which consisted of a Teflon tube with a 2-cm plug of quartz wool-PoropakQ immersed in a bath of 2-propanol and dry ice. Duplicate treatments were utilized. For details, see the study of Kerwin et al. (8). Except where noted, all laboratory incubations where conducted at 20°C. CH4 at various mixing ratios was occasionally added to serum vials with syringes, and MeBr uptake rates were determined 15 min after the addition of CH4. Anaerobic conditions were obtained by flushing vials with N2 for 20 min, followed by a second flushing with N2 after 3 h. MeBr consumption was determined on vials prior to and after flushing with N2. The effect of soil moisture on MeBr uptake in both forest and agricultural soils was determined by measuring MeBr consumption with unaltered soil and then determining rates again after sequential drying (overnight) and wetting (overnight). The effect of temperature on MeBr uptake was determined by incubating vials at various temperatures in a circulating refrigerated- and heated-water bath.

Both heat (autoclaving at 125°C for 1 h) and antibiotics were used to inhibit microbial activity. For the latter, a mixture of tetracycline and chloramphenicol to inhibit bacteria was prepared from individual concentrated stock solutions in ethanol. Just prior to use, these solutions were mixed and diluted in distilled water, and 0.22 ml of the mixture was stirred into soil. Control vials received 0.22 ml of an identical solution without antibiotics. The final concentration of both tetracycline and chloramphenicol was either 25 or 50 μg ml of soil water−1. To inhibit eucaryotic microorganisms, primarily filimentous fungi, 0.22 ml of a solution of cycloheximide in distilled water was added to a final concentration of 150 μg ml of soil water−1. Control vials received 0.22 ml of water alone. To ensure that amendments had sufficient time to influence microbial activity, in some instances antibiotic and control solutions were added immediately prior to MeBr uptake measurements, while in others soils were mixed with solutions 12 h prior to determination of MeBr uptake rates.

Experiments with dynamic serum vials.

To determine rates of MeBr uptake with ambient levels of MeBr (low-pptv levels), we utilized a dynamic flowthrough system in which air containing known and constant quantities of MeBr was passed through soil-containing vials at a constant rate (8). MeBr was measured in air entering and leaving the vials, and the difference was used to calculate uptake rate according to the following equation: rate (nmol min−1 g of dry soil−1) = (F/wt)(C0 − Cf), where F is the flow rate, wt is the dry weight of the soil in the vial, Cf is the mixing ratio of MeBr in the air exiting the vial, and C0 is the mixing ratio of MeBr in the air entering the vial. A constant source of MeBr was provided from the dynamic dilution system which provided standards of high precision with a gravimetrically calibrated permeation device as a source of MeBr (8). Because this dynamic system provided a constant supply of MeBr, we were able to sample as large a volume as necessary to detect MeBr adequately. Hence, we could maintain MeBr flows at ever-lower mixing ratios simply by collecting larger samples. In most instances, at least three replicate sample vials were utilized for each MeBr mixing ratio.

Field measurements.

Flux chambers were used to determine rates of MeBr exchange with soils in the field. Cubic-shaped fluorinated ethylene polypropylene (FEP) Teflon enclosures (30-liter volume) were placed on FEP Teflon-lined aluminum collars which were inserted to ∼15 cm in the soils with a small lip above ground to support the flux chamber. Collars were installed in the sites before field campaigns had begun. Details of the chamber design can be found in the studies of Morrison and Hines (15) and de Mello and Hines (4). Chambers were equipped with brushless fans to mix internal gases. Immediately after chamber deployment, MeBr was injected into the chamber to a final mixing ratio of 600 pptv. Subsamples were removed over time with 60-ml plastic syringes which were transported to the laboratory, where gases were cryotrapped and analyzed. To determine the effect of MeBr loss due solely to diffusion of MeBr into soils, we added sulfur hexafluoride (SF6) to chambers as an inert tracer. SF6 was measured by gas chromatography with electron capture detection (ECD). Diffusional differences for the two gases were accounted for with Graham’s law. The chamber-collar system was determined to be inert to both MeBr and SF6.

Analytical methods.

Details of the MeBr analytical system were described previously (8). Briefly, MeBr was analyzed by gas chromatography with ECD. The ECD was doped with O2, and gas separation was achieved with a precolumn packed with PoropakQ and an analytical column packed with HayeSepQ (Alltech). The precolumn was backflushed to remove detectable materials that eluted later than MeBr. Calibration standards were prepared by a dynamic dilution system with a gravimetrically calibrated permeation device and three-stage dilution box consisting of several mass flow controllers.

RESULTS

Static serum vials.

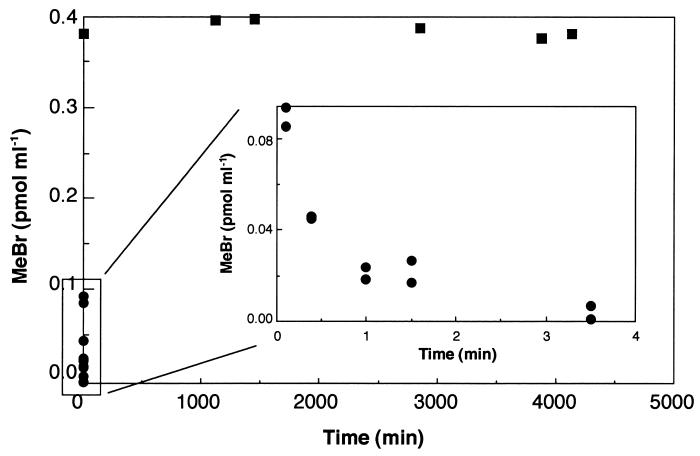

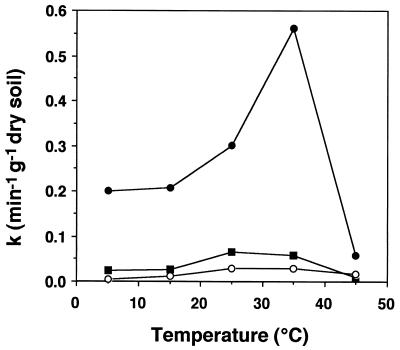

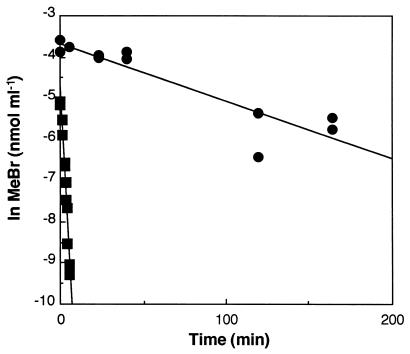

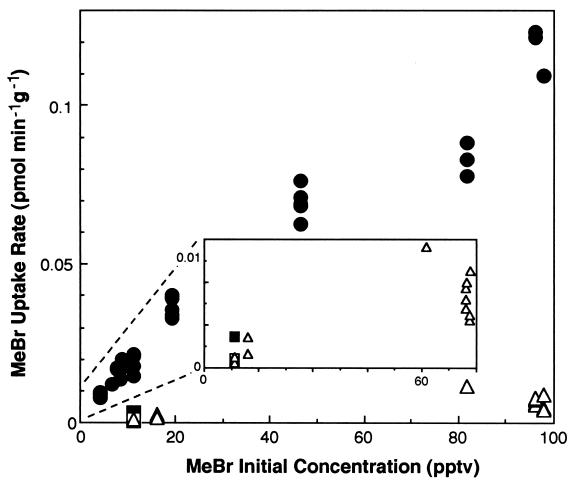

Forest soils consumed MeBr extremely rapidly, with less than 5% remaining in the headspace after 3 min of incubation (Fig. 1). Autoclaving stopped consumption completely (Fig. 1), with no measurable loss in vials incubated for over 3 days. The autoclaving results demonstrated not only that MeBr uptake was biological but also that the serum vial-stopper system did not consume MeBr. In addition, MeBr mixing ratios did not decrease within empty vials for 24 h (data not shown), again indicating the lack of reactivity of incubation vessels. The temperature effect on MeBr uptake was typical for a biologically mediated process (Fig. 2), with optimal uptake occurring between 25 and 40°C. In the upper 3 cm of the soil column the optimum temperature was near 35°C, while a lower optimum was observed in soils from deeper layers. The data shown in Fig. 2 also demonstrated that surficial forest soils consumed MeBr much more rapidly than deeper soils, with rate constants in the upper 3 cm exceeding those at 3 to 7 and 10 to 15 cm by 5- to 15-fold. In all soils tested, maximum rates occurred in samples from the surface.

FIG. 1.

Headspace MeBr mixing ratios during incubations of typical unaltered (•) (inset) and autoclaved (▪) forest soil samples.

FIG. 2.

Effect of temperature on MeBr uptake (rate constant [k]) by incubated forest soils from 0 to 3 cm (•), 3 to 7 cm (▪), and 10 to 15 cm (○).

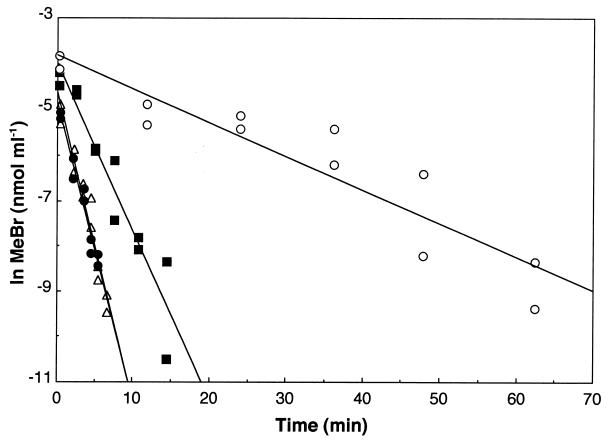

A mixture of 25 μg (each) of tetracycline and chloramphenicol ml−1, added 12 h prior to MeBr measurements, resulted in a 45% reduction in MeBr consumption, while 50 μg ml−1 decreased uptake by 90% (Fig. 3), indicating that bacteria are the major consumers of MeBr. The addition of these antibiotics immediately prior to measurements of MeBr uptake had little to no effect (data not shown), indicating that exposure for at least 12 h was required to significantly impede MeBr utilization. The eucaryotic antibiotic cycloheximide had no effect on MeBr consumption, illustrating the lack of involvement of soil fungi or other eucaryotic organisms (Fig. 3).

FIG. 3.

Effect of antibiotics on MeBr uptake by incubated forest soils. A mixture of the bacterial antibiotics tetracycline and chloramphenicol, each at 25 μg ml of soil water−1 (▪) (uptake rate constant [k] = 0.371 min−1) or 50 μg ml of soil water−1 (○) (k = 0.0738 min−1), and the eucaryotic antibiotic cylcoheximide at 150 μg ml of soil water−1 (▵) (k = 0.681 min−1) was used. Controls (•) (k = 0.653 min−1) consisted of identical solutions without antibiotics.

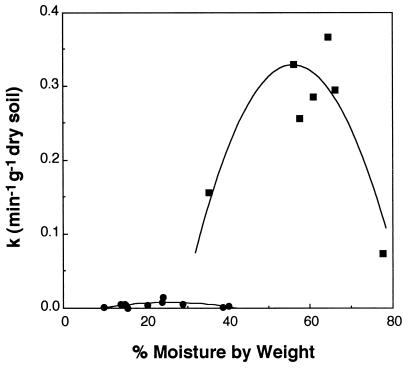

Soil moisture influenced MeBr consumption, with significant drying and wetting adversely affecting uptake in both forest (0- to 3-cm horizon) and agricultural soils (Fig. 4). The moisture content displaying the optimum MeBr uptake rate in the forest soil was much higher than that for the drier agricultural soil (65 versus 25%). Figure 4 also illustrates that the forest soils consumed MeBr much more rapidly than the agricultural soils even when the moisture content yielded maximum rates at both sites. The forest soils also exhibited a much higher organic-matter content (60 versus 9%).

FIG. 4.

Effect of soil moisture on MeBr uptake (rate constant [k]) in forest (▪) and agricultural (•) soils.

Maintenance of soil samples in an N2 atmosphere practically eliminated the uptake of MeBr (Fig. 5), with rates less than 2% of those under aerobic conditions. Testing of samples for MeBr uptake immediately after flushing with N2 indicated that MeBr consumption continued unimpeded (data not shown). We attributed this discrepancy to O2 which remained in vials within soil pores and which was slowly removed over the 3-h period between successive flushings with N2. Additions of H2 and CO2 to anaerobic vials did not change MeBr consumption compared to that with N2 alone.

FIG. 5.

Effect of anaerobic conditions on MeBr uptake during incubations of forest soils (0- to 3-cm horizon). Aerobic vials (▪) and vials flushed twice with N2 over 3 h (•) were used.

Amendments of methane to vials, even up to levels as high as 5%, had no effect on MeBr uptake (Fig. 6). MeBr consumption appeared to be slightly faster in methane-amended samples; however, data were variable, as indicated by the duplicate data, and there was no statistical difference between rates with or without added CH4.

FIG. 6.

Effect of addition of 5% CH4 (•) on MeBr uptake by surficial temperate forest soils. An unamended control (○) is also shown.

A comparison of MeBr uptake rates in the four soils studied demonstrated that the temperate forest site was considerably more active than the others (Table 1). The moisture and organic-matter contents of the agricultural and sandy boreal forest soils were low relative to those of the temperate forest soil. However, the tropical forest soil had moisture and organic-matter content which were similar to those of the 3- to 7-cm of temperate forest soil, yet the latter soil consumed MeBr 10 times faster on a dry-weight basis.

TABLE 1.

MeBr uptake rate constants (k) for various soils

| Soil and depth | k (min−1 g [dry wt]−1) (±SE) |

|---|---|

| Temperate foresta | |

| 0–3 cm | 0.284 ± 0.028 |

| 3–7 cm | 0.0652 ± 0.015 |

| 10–15 cm | 0.0168 ± 0.0016 |

| Temperate corn field | 0.00356 ± 0.0033 |

| Boreal forest (sandy) | 0.0102 ± 0.0005 |

| Tropical forest | 0.00652 ± 0.0011 |

Below surface-litter layer.

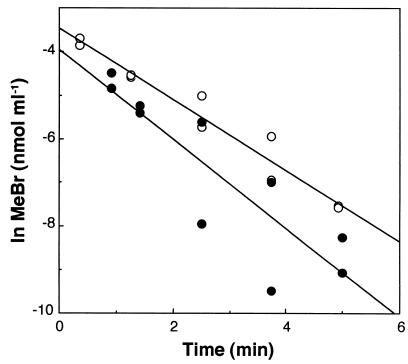

Dynamic serum vials.

The dynamic incubation technique allowed us to investigate rates of MeBr consumption at mixing ratios down to 103-fold lower than those used in the static incubations, including measurements with MeBr mixing ratios at levels found in the remote global atmosphere (5 to 15 pptv). The results clearly demonstrated that soils are capable of rapidly consuming MeBr at ambient levels and below (Fig. 7). Several mixing ratios of MeBr were used for measurements of MeBr uptake by the 0- to 3-cm forest soils and the corn field soils during dynamic incubation studies. Only one low mixing ratio of MeBr was used for determinations of uptake by forest soils from below 3 cm (Fig. 7). Uptake displayed essentially first-order kinetics for all experiments in which several mixing ratios of MeBr were used, and all soils examined consumed MeBr at the lowest mixing ratios tested, all of which were <12 to 15 pptv.

FIG. 7.

MeBr uptake rates during incubations of soils at various initial mixing ratios of MeBr. Temperate forest soils from depths of 0 to 3 cm (•), 3 to 7 cm (▪), and 10 to 15 cm (□) and temperate agricultural (corn field) surface soils (▵) were used. Inset expands all data except the forest soil from depths of 0 to 3 cm.

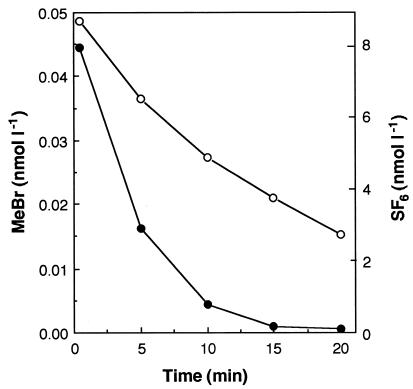

Field experiments.

MeBr was consumed rapidly within chambers deployed over soils in the field, especially the temperate forest soils in which MeBr mixing ratios decreased from 0.045 nmol liter−1 (∼1,000 pptv) to less than 0.005 nmol liter−1 (∼100 pptv) in 10 min (Fig. 8). Approximately 10 to 15 measurements were made at each site. In some instances in the temperate forest, MeBr decreased to below the detection limit of ∼2 pptv in less than 10 min. MeBr was consumed much more rapidly than SF6 in the forest soils (the latter decreasing from ∼9 nmol liter−1 to less than 3 pmol liter−1 in 20 min [Fig. 8]), indicating that MeBr loss was due not only to diffusion but also to active consumption by soils. Uptake of MeBr was also rapid when flux chambers were placed over a grassy lawn (data not shown). On the other hand, rates of loss of MeBr and SF6 were equal in chambers deployed in the corn field site (data not shown).

FIG. 8.

Example of the loss of MeBr (•) and an inert SF6 tracer (○) within a flux chamber placed over a temperate forest soil plot in summer.

DISCUSSION

MeBr was consumed extremely rapidly by soils, especially by surficial temperate forest soils, where its complete removal from experimental vials occurred in a matter of minutes during incubations (Fig. 1). MeBr amendments were also removed rapidly from flux chambers in the field (Fig. 8). The use of a dynamic flowthrough incubation vial system indicated that soils continue to rapidly consume MeBr even when mixing ratios are in the low-pptv range (Fig. 7). Hence, soils are significant sinks for MeBr at all levels of MeBr found in the atmosphere, including those in soils exposed to MeBr fumigation and those in soils in remote areas.

MeBr uptake was completely microbial. Oremland et al. (16) and Miller et al. (14) reported that microbes were responsible for degrading a significant portion of MeBr added to soils, but at the levels that were used, Oremland et al. (16) noted a significant loss of MeBr in killed controls even when MeBr was at 10 parts per million by volume (ppmv). In our experiments, autoclaved controls did not remove any MeBr, and broad-spectrum bacterial antibiotics significantly inhibited MeBr consumption (Fig. 1 and 3). In addition, the temperature response of MeBr uptake was biological in nature. Although MeBr in water is known to hydrolyze to methanol (24), hydrolysis is obviously very slow and insignificant for the incubations used here. A chemical sink may be important in soils fumigated with high levels of MeBr, and surface-linked sorption and chemical removal via nucleophilic substitutions have been previously implicated in the loss of MeBr in agricultural soils (5, 27). However, at the low MeBr levels reported here (<15 ppbv), a chemical sink was not apparent, and our data suggest that at levels below ∼1 ppmv, all of the uptake of MeBr occurs directly by microbes. The antibiotic experiments also indicated that this uptake is bacterial and that fungi are not involved (Fig. 3).

All of the data from various experiments indicated that MeBr uptake by soils occurs via first-order kinetics, at least in the range from low-pptv to high-ppbv levels. Previous studies with MeBr at levels of 10 to 10,000 ppmv reported uptake rates that were rapid, but with rate constants that decreased greatly with increasing MeBr mixing ratios, presumably due to poisoning by MeBr rather than by enzyme saturation (16). Gan et al. (5) assumed first-order kinetics in describing loss of MeBr in vial incubation studies with initial MeBr mixing ratios of ∼100 ppmv. However, their rate constants were approximately 106-fold lower than ours for a variety of soils, suggesting that first-order kinetics were not appropriate in their case and that a poisoning effect was probable. Using low MeBr mixing ratios, we did not note any chemical reactivity of MeBr, and rate constants did not vary over the 10 pptv to 1 ppmv range in initial MeBr mixing ratios. This result underscored the dominance of bacterial processes in consuming MeBr, and as discussed below, the occurrence of first-order kinetics allowed us to use static incubation data and our field experiments to calculate natural consumption rates of ambient MeBr by soils.

Physiochemical factors appeared to greatly influence rates of MeBr uptake. Gan et al. (5, 6) reported a negative correlation between both organic-matter content and moisture and MeBr volatilization by incubated soils, which they attributed to the methylation of organic material by MeBr and the inability of MeBr to penetrate moist and dense soils. Our findings that MeBr consumption is bacterial and that uptake is most active in organic-rich temperate soils suggested that microbially active soils are sites of intense MeBr consumption. Dry and organic-poor agricultural and sandy soils, which would be expected to harbor a less-active microbial community, exhibited low rates of MeBr uptake (Table 1). Conversely, the tropical soils which were more organic rich and moist than both the agricultural and sandy boreal soils still exhibited low rates of MeBr uptake compared to those of surface temperate forest soils. With regard to organic matter and moisture content, the tropical soils were similar to the 3- to 7-cm-deep temperate forest soils, yet MeBr uptake rates in the former were 10-fold lower. The cause of this discrepancy was not clear. Since the tropical soil bacteria may have had temperature optima which were greater than those of bacteria in the temperate or boreal soils, MeBr uptake may have been higher in the tropical soils at ambient temperatures. However, even the two- to threefold increase in tropical uptake rates expected with a 10°C rise in temperature would not make tropical soils significant consumers of MeBr compared to temperate forest soils. In general, it appeared that temperate soils were the sites of the most-active MeBr consumption, regardless of organic or moisture contents, and these soils deserve additional attention as globally significant sinks of MeBr.

Changing the moisture content of forest and corn field soils revealed that moisture optima for MeBr uptake differed greatly for each soil type but remained relatively close to the in situ moisture level (25 and 50% for corn field and forest soils, respectively) (Fig. 4). This finding implied that the MeBr-consuming microbiota are well adapted to in situ conditions and may be diverse with respect to the conditions required for MeBr uptake. The fact that temperature optima for MeBr uptake decreased with depth in temperate forest soils (Fig. 2) also supported this notion, since soil temperatures decrease with depth as well. Since MeBr is consumed within minutes in surface soils, microbiota situated below the few surficial centimeters would not normally be in contact with atmospheric MeBr. However, soils collected several centimeters below the surface consumed MeBr without a lag and relatively quickly, albeit slower than surface soils, indicating that the ability to utilize MeBr is constitutive and/or perhaps a fortuitous process (23). It is also possible that subsurface MeBr occurs in situ due to the production of methyl halides by soil fungi (7).

MeBr uptake was generally an aerobic process which did not occur significantly during anaerobic incubations, including those in which excess H2 and CO2 were added. Methyl halides can be used by anaerobic bacteria, including acetogens (10, 12) and methanogens (17), and anaerobic sediments are capable of using MeBr (17). Oremland et al. (16) suggested that anaerobic bacteria in soils may be significant consumers of MeBr but were unable to detect any role of methanogens or acetogens. At the lower mixing ratios employed in our studies, anaerobic activity did not significantly consume MeBr, even in incubations with added H2, which would tend to stimulate both methanogens and acetogens. However, it is possible that consumption by anaerobes occurs at the higher mixing ratios used by others and in agricultural soils fumigated with MeBr. We did not take special precautions to protect anaerobic bacteria from oxygen during sampling, and we did not test whether soils from depths of greater than 3.0 cm were capable of significant anaerobic consumption of MeBr. However, surface soils, which are the most aerated in the soil column, consumed MeBr very rapidly and aerobically, indicating that even if anaerobic MeBr consumption occurs in soils, the bulk of the uptake is by surficial bacteria metabolizing aerobically.

Oremland et al. (16) reported that a significant portion of the MeBr consumed by soils was due to activities of methanotrophic bacteria based on the inhibition of uptake by additions of methyl fluoride and the consumption of MeBr by cell suspensions of the methanotroph Methylococcus capsulatus. Increasing CH4 concentrations were shown to inhibit MeBr consumption by cultures of M. capsulatus and vice versa. On the other hand, although there was a lag in CH4 uptake by soil incubations until MeBr was consumed, MeBr consumption was not affected by the presence of CH4 (16). In our experiments with temperate forest soils, additions of up to 5% methane had essentially no effect on the rate of MeBr consumption (Fig. 6) even though CH4 mixing ratios exceeded those of MeBr by 107-fold. One would expect CH4:MeBr ratios this high to impede MeBr consumption if methanotrophs such as M. capsulatus were responsible for MeBr uptake in natural soils. Hence, it is likely that other types of bacteria are the major consumers of MeBr in soils, except perhaps in soils receiving high quantities of MeBr during fumigation. Ou et al. (18) found that soils preincubated with high levels of methane exhibited increased rates of MeBr consumption, presumably due to the stimulation of methanotrophs. However, these researchers utilized relatively high levels of MeBr in their experiments (from 500 to 1,000 μg g−1).

Microbial consumption of methane in soils is relatively insignificant in the upper few centimeters, with optimum activity occurring at depths of 3 to 7 cm (3). The relative difference in the depth distribution of MeBr and methane consumption in temperate forest soils (0 to 3 cm and 3 to 7 cm, respectively) also supports the idea that methanotrophs, like those presently in culture, are not major consumers of MeBr when it is at ambient levels. In natural soils where ambient methane is not consumed significantly throughout the upper few centimeters, the ratio of methane to MeBr would be expected to be approximately 10,000. Therefore, it seems unlikely that known methane monooxygenases would utilize MeBr at the soil surface, but not methane. During experiments with MeBr at ppmv levels or higher, a mixing ratio equal to or greater than ambient methane, it is not surprising that this enzyme is capable of using MeBr. Furthermore, since MeF is an analog of MeBr, MeF would be expected to adversely affect MeBr consumption by bacteria regardless of whether methane monooxygenase was involved. Hence, the type of bacteria responsible for MeBr uptake in soils is unknown and is probably not like known methanotrophs.

MeBr was consumed readily by soil plots enclosed within flux chambers in the field. Uptake rates in the temperate forest (and the temperate grassy lawn) were very rapid and greatly exceeded rates of diffusion alone as determined by the loss of the SF6 inert tracer (Fig. 8). However, field MeBr uptake rates by the corn field soils were the same as the diffusion rate determined by SF6. Since our laboratory incubation experiments demonstrated that MeBr was actively consumed by corn field soils, the finding that both MeBr and SF6 disappeared at equal rates in field flux chambers suggested that the consumption of MeBr in this case was limited by diffusion. Hence, estimations of in situ rates of MeBr consumption by the corn field soils were made with rate constants based on field diffusion rates as opposed to those determined by laboratory bulk sediment incubations (21). However, laboratory incubation studies were required to demonstrate that these soils did indeed consume MeBr.

Our finding that uptake of MeBr by soil bacteria is extremely rapid has implications for the role of soil bacteria in the fate of MeBr. The laboratory dynamic dilution incubation system allowed us to investigate the direct uptake of MeBr at mixing ratios equal to or lower than those found in the global atmosphere, indicating that soils are a potential sink for MeBr worldwide, not only in locales that are subjected to high levels of the gas used for agricultural purposes. We previously used data like these (Table 1 and Fig. 8) to estimate that the uptake of MeBr by soils accounts for about 25% of the loss of MeBr from the atmosphere (21), a sink that significantly decreases the potential detrimental impact of MeBr-derived Br on stratospheric ozone.

In conclusion, the use of MeBr at initial mixing ratios which were several orders of magnitude lower than those in previous studies provided insights into the uptake of this important compound by soils. It appears that the chemical uptake of MeBr and the poisoning effects of MeBr on MeBr uptake by bacteria and other microbial processes (i.e., methane consumption) are significant only at MeBr levels above approximately 1 ppmv. In addition, at higher levels used previously (>1 ppmv), MeBr appears to be consumed by methanotrophs similar to those in culture and is significantly consumed by anaerobic bacteria as well. These findings have significant implications for what may occur in agricultural sites fumigated with MeBr. However, in typical unfumigated soils which are subjected to MeBr at mixing ratios of ∼10 pptv, MeBr is consumed readily and completely at the soil surface by bacteria metabolizing aerobically, uptake is first order up to ∼1 ppmv, and chemical removal is negligible. The actual types of aerobes responsible for bacterial removal of MeBr from the ambient atmosphere remain unclear.

REFERENCES

- 1.Colby J, Dalton H, Whittenbury R. An improved assay for bacterial methane mono-oxygenase: some properties of the enzyme from Methylomonas methanica. Biochem J. 1975;151:459–462. doi: 10.1042/bj1510459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Colby J, Stirling D J, Dalton H. The soluble methane mono-oxygenase of Methylococcus capsulatus (Bath.) Biochem J. 1977;165:395–402. doi: 10.1042/bj1650395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Crill P M. Seasonal patterns of methane uptake and carbon dioxide release by a temperate woodland soil. Global Biogeochem Cycles. 1991;5:319–334. [Google Scholar]

- 4.de Mello W Z, Hines M E. Application of static and dynamic enclosures for determining dimethyl sulfide and carbonyl sulfide exchange in Sphagnum peatlands: implications for the magnitude and direction of flux. J Geophys Res. 1994;99:14601–14607. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gan J, Yates S R, Anderson M A, Spencer W F, Ernst F F, Yates M V. Effect of soil properties on degradation and sorption of methyl bromide in soil. Chemosphere. 1994;29:2685–2700. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gan J, Yates S R, Wang D, Spencer W M. Effect of soil factors on methyl bromide volatilization after soil application. Environ Sci Technol. 1996;30:1629–1636. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Harper D B. Biosynthesis of halogenated methanes. Biochem Soc Trans. 1994;22:1007–1011. doi: 10.1042/bst0221007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kerwin R A, Crill P M, Talbot R W, Hines M E, Shorter J H, Kolb C E, Harriss R C. Determination of atmospheric methyl bromide by cryotrapping-gas chromatography and application to soil kinetic studies using a dynamic dilution system. Anal Chem. 1996;68:899–903. doi: 10.1021/ac950811z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lobert J M, Butler J H, Montzka S A, Geller L S, Myers R C, Elkins J W. A net sink for atmospheric CH3Br in the East Pacific Ocean. Science. 1995;267:1002–1005. doi: 10.1126/science.267.5200.1002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Magli A, Rainey F A, Leisinger T. Acetogenesis from dichloromethane by a two-component mixed culture comprising a novel bacterium. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1995;61:2943–2949. doi: 10.1128/aem.61.8.2943-2949.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mellouki A, Talukdor R K, Schmoltner A-M, Gierczak T, Mills M J, Solomon S, Ravishankara A R. Atmospheric lifetimes and ozone depletion potentials of methyl bromide (CH3Br) and dibromomethane (CH2Br2) Geophys Res Lett. 1992;19:2059–2062. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Meßmer M, Wohlfarth G, Diekert G. Methyl chloride metabolism of the strictly anaerobic, methyl chloride-utilizing homoacetogen strain MC. Arch Microbiol. 1993;160:383–387. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Meyers A J. Evaluation of bromomethane as a suitable analogue in methane oxidation studies. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1980;9:297–300. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Miller L G, Connell T L, Guidetti J R, Oremland R S. Bacterial oxidation of methyl bromide in fumigated agricultural soils. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1997;63:4346–4354. doi: 10.1128/aem.63.11.4346-4354.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Morrison M C, Hines M E. The variability of biogenic sulfur flux from a temperate salt marsh on short time and space scales. Atmos Environ. 1990;24:1771–1779. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Oremland R S, Miller L G, Culbertson C W, Connell T L, Jahnke L. Degradation of methyl bromide by methanotrophic bacteria in cell suspensions and soils. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1994;60:3640–3646. doi: 10.1128/aem.60.10.3640-3646.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Oremland R S, Miller L G, Strohmaler F E. Degradation of methyl bromide in anaerobic sediments. Environ Sci Technol. 1994;28:514–520. doi: 10.1021/es00052a026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ou L T. Accelerated degradation of methyl bromide in methane-, 2,4-D-, and phenol-treated soils. Bull Environ Contam Toxicol. 1997;59:736–743. doi: 10.1007/s001289900542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ou L T, Joy P J, Thomas J E, Hornsby A G. Stimulation of microbial degradation of methyl bromide in soil during oxidation of an ammonia fertilizer by nitrifiers. Environ Sci Technol. 1997;31:717–722. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rasche M E, Hyman H R, Arp D J. Biodegradation of halogenated hydrocarbon fumigants by nitrifying bacteria. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1990;56:2568–2571. doi: 10.1128/aem.56.8.2568-2571.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shorter J H, Kolb C E, Crill P M, Kerwin R A, Talbot R W, Hines M E, Harriss R C. Rapid degradation of atmospheric methyl bromide in soils. Nature. 1995;377:717–719. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Solomon S, Mills M, Heidt L E, Pollock W H, Tuck A F. On the evaluation of ozone depletion potentials. J Geophys Res. 1992;97:825–842. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stirling D L, Dalton H. The fortuitous oxidation and cometabolism of various carbon compounds by whole-cell suspensions of Methylococcus capsulatus (Bath.) FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1979;5:315–318. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Swain C G, Scott C B. Quantitative correlation of relative rates. Comparison of hydroxide ion with other nucleophilic reagents toward alkyl halides, esters, epoxides, and acyl halides. J Am Chem Soc. 1953;75:141–147. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wofsy S C, McElroy M B, Yung Y L. The chemistry of atmospheric bromine. Geophys Res Lett. 1975;2:215–218. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yates S R, Ernst F F, Gan J, Gao F, Yates M V. Methyl bromide emissions from a covered field. II. Volatilization. J Environ Qual. 1996;25:192–202. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yates S R, Gan J, Ernst F F, Matziger A, Yates M V. Methyl bromide emissions from a covered field. I. Experimental conditions and degradation in soil. J Environ Qual. 1996;25:184–192. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yvon-Lewis S A, Butler J H. The potential effect of oceanic biological degradation on the lifetime of atmospheric CH3Br. Geophys Res Lett. 1997;24:1227–1230. [Google Scholar]