Introduction

Esophageal adenocarcinoma (EAC) is a highly fatal disease with an increasing incidence from 0.54 to 3.76 per 100,000 person-years from 1975 to 20161 that has been mirrored by a rise in EAC-related mortality. Since Barrett’s esophagus (BE) is the only known precursor lesion to EAC, early recognition and intervention could potentially reduce the societal burden of EAC by detecting cancers at an earlier stage and improving outcomes. Accordingly, professional gastroenterology society guidelines recommend screening upper endoscopy for at-risk individuals [chronic GERD (gastroesophageal reflux disease) along with the presence of other risk factors such as age >50 years, male sex, White race, smoking, obesity and family history of BE or EAC).2–5 Notably, most of these are conditional recommendations with weak evidence and there are no screening guidelines from the US Preventive Services Task Force or other Internal Medicine societies.

Current programs are ineffective as nearly 90% of EAC cases do not have known BE at the time of cancer diagnosis and the majority of EACs are found outside of dedicated screening programs.6 Screening algorithms largely rely on the diagnosis of GERD, but only 7–10% of GERD patients have BE, up to 25% of BE patients are asymptomatic, and 20–50% of EAC patients have no prior GERD symptoms.7, 8 Not only will patients at risk for BE/EAC be missed if GERD is required for screening, but from a societal and resource standpoint this approach is not practical given that GERD is very common. Results from a population-based survey of 78,812 persons in the US demonstrated that nearly 2 out of 5 patients (44%) had GERD symptoms in the past and this number is likely to increase with the obesity epidemic.9 Thus, the current paradigm for screening according to GERD and other risk factors needs to be changed. Nguyen et al evaluated the performance characteristics of screening guidelines among 513 veterans evaluated in primary care clinics and demonstrated that published guidelines are suboptimal in predicting BE (sensitivity 38.6–43.2% and specificity 71.6–75.1%). The 2011 American Gastroenterological Association guidelines, which do not mandate the presence of GERD symptoms to screen for BE, had a sensitivity of 100% and specificity of 0.2%.10 Ongoing efforts to incorporate risk prediction models that go beyond the presence of GERD symptoms will help better target individuals who would benefit most from screening.11

There are also more nuanced limitations to screening in the clinical setting and lack of studies characterizing practice patterns among gastroenterologists (GIs) and primary care providers (PCPs). Prior data demonstrate significant heterogeneity among GIs regarding BE screening practices,12 but overall there is minimal data to explain if BE screening is inadequate due to providers failing to recognize at-risk patients and refer them for endoscopy, patients failing to heed their physicians’ recommendation, system-level factors preventing patients from completing screening endoscopy, or a combination of the above. Additionally, PCPs often serve at the frontline in managing reflux symptoms and assessing candidacy for BE and EAC screening, but their attitudes and barriers to screening are not known. A detailed understanding of provider practice patterns, predictors of behavior, and key barriers to effective screening are essential to develop and implement interventions to improve BE screening and ultimately make population-level improvements in EAC outcomes.

SCREEN-BE survey study

We conducted the Study of Compliance, Practice Patterns, and Barriers REgarding Established National Screning Programs for Barrett’s Esophagus (SCREEN-BE), a web-based survey study to define GI and PCP knowledge, attitudes, and barriers to BE screening, and to evaluate how these relate to their application of screening guidelines in clinical practice. This was performed at four tertiary care referral and two affiliated safety-net health systems in the U.S (ClinicalTrials.gov NCT04408105). Surveys were developed using a theoretical model of physician behavior based on Social Cognitive Theory13 and the Theory of Reasoned Action and questions were adapted from earlier validated cancer screening-based surveys.14 (Supplemental Figure 1). To assess knowledge of BE screening, we designed nine clinical vignettes and categorized provider responses as concordant or discordant with published guidelines2, 4 (the gold standard for construct validity for this study). (Supplemental Figure 2). To evaluate responses to 9 clinical vignettes, 1 point was assigned for each guideline concordant recommendation (score range 0–9). GIs were given a point for a guideline concordant recommendation to perform screening endoscopy, and PCPs for ordering screening endoscopy or referring to GI to discuss screening (Supplementary Methods). The multicenter administration of rigorously developed surveys with multiple domains of physician behavior across different health care systems with geographic, socioeconomic, and cultural diversity adds to the generalizability of results and enhances validity.

We obtained a GI and PCP response rate of 74.5% (120/161) and 49.2% (195/396), respectively (Supplemental Table 1). Most respondents were physicians (91.5%) with a wide distribution of numbers of years in practice. The majority (76.3% GI, 92.0% PCP) reported seeing 2 or more patients with reflux per week. Despite the high volume of patients, the majority of GI and PCP clinics did not have a mechanism to remind providers when patients were eligible for BE screening; most felt this should be incorporated into the electronic health record.

Provider Attitudes toward BE Screening

Although over 70% of GIs and PCPs believe that BE screening is effective for early EAC detection, few believed it reduced all-cause mortality (22.6% and 21.9% respectively), and PCPs in particular expressed concerns regarding cost effectiveness (Table 1). Most providers agreed more data evaluating screening benefits (GI 74.8%, PCP 65.7%) and harms (GI 67.0%, PCP 59.0%) are needed, including data from randomized controlled trials for BE screening (GI 90.4%, PCP 80.3%). This perspective is not particularly surprising given the lack of randomized controlled trials demonstrating the effectiveness or mortality reduction from BE screening. Prior survey data indicate that 85% of GIs feel the evidence for BE screening is inadequate, only 48% think it is cost-effective to screen, and many perform screening despite concerns about effectiveness most commonly due to medicolegal liability.15 Support for screening is largely derived from retrospective cohort studies demonstrating better outcomes among BE/EAC patients who received screening endoscopy. Furthermore, BE screening with endoscopy and alternative methods appears to be cost effective in high-risk groups; however, this may depend on the potential mortality benefit afforded by treating dysplastic BE.16, 17 Although recent data from a RCT indicates the benefit of a non-invasive screening method in the primary care setting to detect BE compared to usual care,18, studies comparing screening to no screening may never demonstrate a reduction in mortality at the population level given the relatively low incidence of EAC and low number of cancers arising from BE. This remains a challenge in widespread adoption of BE screening, especially considering our results showing that 90% of GIs and 80% of PCPs desire strong data from a RCT to impact their decision making.

Table 1.

Gastroenterology and Primary Care Provider Attitudes related to BE Screening

| Provider Attitudes |

GI

(N = 120) |

PCP

(N = 195) |

P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| BE screening with upper endoscopy is effective for early esophageal cancer detection e | 0.02* | ||

| Strongly agree or agree, n (%) | 83 (72.2) | 127 (70.9) | |

| Neither agree nor disagree, n (%) | 20 (17.4) | 46 (25.7) | |

| Strongly disagree or disagree, n (%) | 12 (10.4) | 6 (3.4) | |

| BE screening with upper endoscopy reduces all-cause mortality f | <0.01* | ||

| Strongly agree or agree, n (%) | 26 (22.6) | 39 (21.9) | |

| Neither agree nor disagree, n (%) | 36 (31.3) | 109 (60.7) | |

| Strongly disagree or disagree, n (%) | 53 (46.1) | 31 (17.4) | |

| BE screening with upper endoscopy is cost-effective for at-risk individuals e | <0.01* | ||

| Strongly agree or agree, n (%) | 64 (55.7) | 68 (38.0) | |

| Neither agree nor disagree, n (%) | 34 (29.6) | 92 (51.4) | |

| Strongly disagree or disagree, n (%) | 17 (14.8) | 19 (10.6) | |

| Not performing Barrett’s esophagus screening poses malpractice liability e | <0.01* | ||

| Strongly agree or agree, n (%) | 47 (40.9) | 46 (25.7) | |

| Neither agree nor disagree, n (%) | 45 (39.1) | 103 (57.5) | |

| Strongly disagree or disagree, n (%) | 23 (20.00) | 30 (16.8) | |

| Primary care providers should not order BE screening based on lack of recommendation from the U.S. Preventative Services Task Force e | <0.01* | ||

| Strongly agree or agree, n (%) | 20 (17.4) | 51 (28.5) | |

| Neither agree nor disagree, n (%) | 44 (38.3) | 92 (51.4) | |

| Strongly disagree or disagree, n (%) | 51 (44.3) | 36 (20.1) | |

| Better data on the benefits of BE screening are needed f | <0.01* | ||

| Strongly agree or agree, n (%) | 86 (74.8) | 117 (65.7) | |

| Neither agree nor disagree, n (%) | 14 (12.2) | 56 (31.5) | |

| Strongly disagree or disagree, n (%) | 15 (13.0) | 5 (2.8) | |

| Better data on the harms of BE screening are needed f | <0.01* | ||

| Strongly agree or agree, n (%) | 77 (67.0) | 105 (59.0) | |

| Neither agree nor disagree, n (%) | 20 (17.4) | 66 (37.1) | |

| Strongly disagree or disagree, n (%) | 18 (15.7) | 7 (3.9) | |

| A randomized trial on BE screening would impact my decision to refer patients for screening f | 0.03* | ||

| Strongly agree or agree, n (%) | 104 (90.4) | 143 (80.3) | |

| Do not agree or strongly agree, n (%) | 11 (9.6) | 35 (19.7) | |

| BE screening with upper endoscopy has equally strong supporting data as colon cancer screening with colonoscopy f | <0.01* | ||

| Strongly agree or agree, n (%) | 7 (6.1) | 8 (4.5) | |

| Neither agree nor disagree, n (%) | 24 (20.9) | 77 (43.3) | |

| Strongly disagree or disagree, n (%) | 84 (73.0) | 93 (52.2) |

= 21 missing,

= 22 missing

Provider practice patterns related to Barrett’s esophagus screening

Whereas half (54.2%) of GI providers order at least one upper endoscopy for BE screening per month, only 17.4% of PCPs reported ordering BE screening and 29.7% reported referring patients to GI to discuss BE screening per month. Over two-thirds of GIs but only 31.8% of PCPs discuss the benefits and harms of BE screening in detail with patients with chronic GERD. These results highlighting provider practice patterns are consistent with epidemiological data demonstrating that only 10% of individuals with GERD undergo upper endoscopy within the first year of diagnosis.19 GI providers were more consistently able to identify BE risk factors that would prompt screening compared to PCPs who tend to overlook key risk factor and are less likely to recommend screening when appropriate (Supplemental Table 2) This failure to recognize the demographic and clinical factors that warrant consideration for BE screening may be a modifiable target to improve early detection of EAC. When GIs were asked about the relevance of the US Preventative Services Task Force (USPSTF) not having a recommendation on BE screening, 80% felt that this would not prevent GIs from ordering BE screening and 44.3% of GIs felt this would not prevent PCPs from ordering BE screening. PCPs appear to value data on benefits and risks of BE screening over direct endorsement from the USPSTF to conduct screening.

Unlike most other cancers where a negative examination should be followed by additional screening at a future date, BE screening is recommended as a one-time test that does not require repeated screening. While 18.0% of GIs would not recommend BE screening at all, most GIs (65.8%) appropriately would not recommend repeat screening after a negative endoscopy for BE. The rest did recommended repeat screening after a negative exam at either 3, 5 or 10 years (4.2%, 10.0%, and 1.7%, respectively). Approximately 32.0% of PCPs do not recommend screening at all, 31.8% of PCPs would not recommend repeat screening after a negative upper endoscopy, and the rest recommend repeat screening at 1, 3, 5 or 10 years (2.1%, 16.4%, 14.9%, and 2.6%, respectively). Notably, only 2/3 of GIs and 1/3 of PCPs in this study appreciate current recommendations for one-time BE screening. Although screening for BE is grossly underutilized, these results highlight the potential for overuse or unnecessary repeated exams and the need for education and clarification of this point in future guidelines.

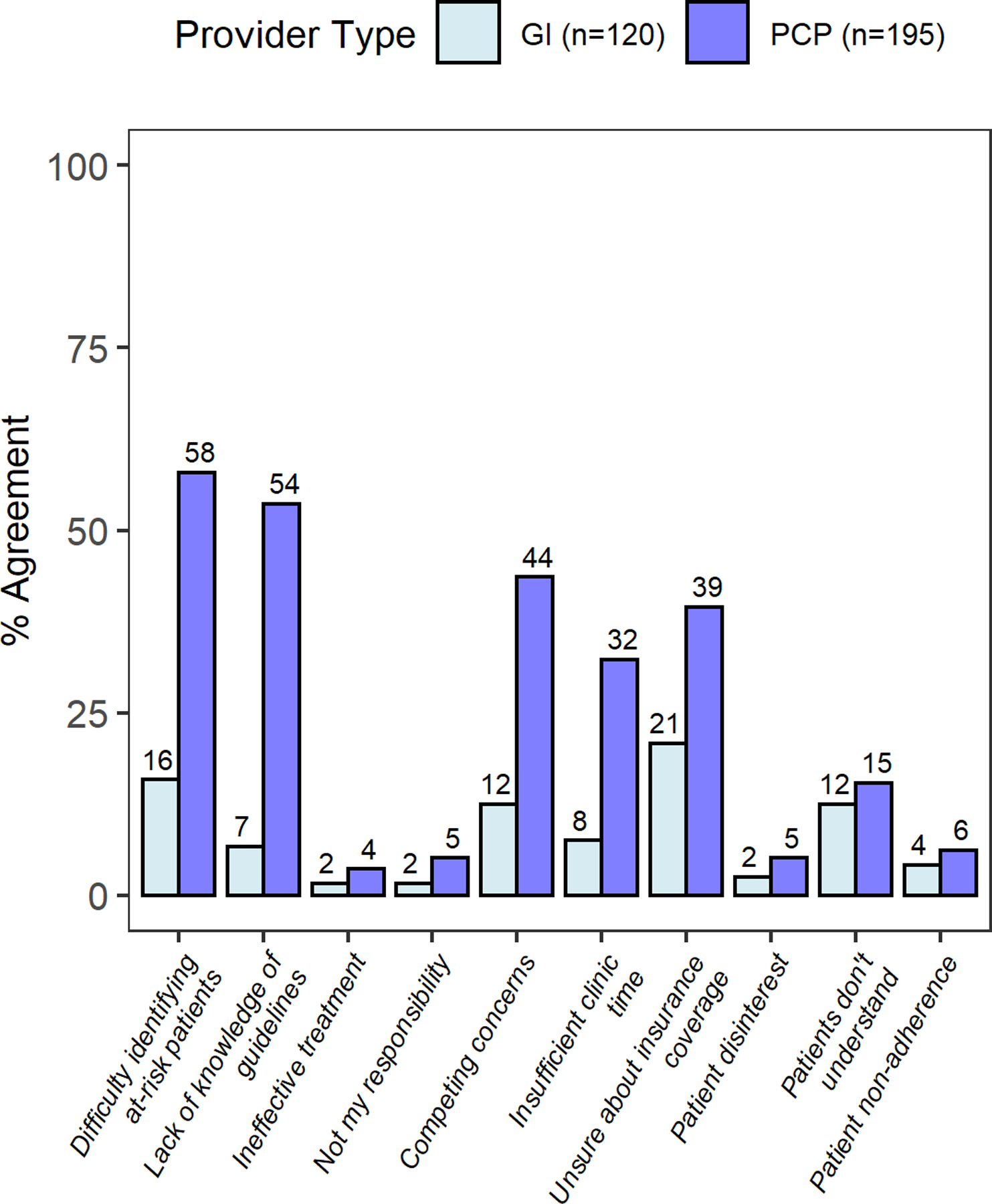

Barriers to Barrett’s esophagus screening

Whereas GIs reported minimal barriers to performing BE screening, PCPs identified several barriers at the provider and system level (Figure 1a, Supplemental table 3). Only 15.8% of GIs have difficulty knowing who should undergo upper endoscopy for BE screening, while 58.2% of PCPs note difficulty. Similarly, 75.8% of GIs reported that they know the current BE screening guidelines compared to only 15.5% of PCPs. Neither group felt that patients would have difficulty understanding information about BE or would be hesitant to undergo endoscopy. Most GI providers (62.8%) and PCPs (75.9%) reported they would be interested to learn more about BE screening. In contrast to GIs, PCPs identified multiple barriers at the provider and system level that hinder their ability to screen appropriately for BE. PCPs report a lack of knowledge related to screening guidelines and have difficulty identifying which patients to screen, despite seeing many patients with GERD. One potential contributing factor is the published literature on BE risk factors and screening has been largely confined to GI journals and professional circles. Additionally, efforts to dissuade PCPs from referring to endoscopy prior to a trial of acid-suppressive medication, or to limit use of proton pump inhibitors, may cause confusion among PCPs about diagnostic versus screening exams. In a previous questionnaire of >1000 PCPs attending industry sponsored conferences on GERD, 87% of respondents agreed that patients with GERD for ≥5 years should have screening EGD for BE, however 50% were unable to order the EGD through open access endoscopy and needed consultation with a GI provider.20 More PCPs than GIs identified competing clinical issues and time limitations that prevented them from addressing screening for BE (44.3% vs. 12.5% and 32.8% vs. 7.5% respectively).These barriers are consistent across other cancer screenings, including colorectal cancer and hepatocellular carcinoma.21 Several types of interventions such as provider training or best practice alerts in the electronic health record (EHR) may be effective in improving cancer screening quality in the primary care setting.22 Leveraging new technologies within the EHR for population health management may prove effective. Our results highlight the need for more robust educational and advocacy efforts on the part of GIs as well as improved partnership with our colleagues since PCPs are at the front line for screening.

Figure 1a.

Provider barriers to Barrett’s esophagus screening

Application of screening guidelines to clinical scenarios

When presented with clinical scenarios, GI providers were more likely to provide guideline-concordant screening recommendations than PCPs (mean composite score 7.0 ± 1.3 vs 5.7 ± 1.1, p<0.01) (Figure 1b). For the four vignettes where screening was not indicated, PCPs were more likely to recommended screening (47.2%) compared to GIs (35.1%, p<0.001). Similarly, in the five vignettes where screening was indicated, PCPs did not recommend screening 31.8% of the time compared to 14.0% among GIs (p<0.001). These results suggest a clear need for education and dissemination of current societal guidelines among primary care audiences.

Figure 1b.

GI and PCP application of guidelines to 9 clinical vignettes

Footnote:

*Mean score (SD) for GI versus PCP: 7.01 (1.28) vs 5.66 (1.12), p<0.01

**1 point assigned for each guideline concordant recommendation for a minimum score of 0 and maximum score of 9. GIs were given a point for a guideline concordant recommendation to perform screening endoscopy and PCPs were given a point for a guideline concordant recommendation to order screening endoscopy or refer to GI to discuss screening.

Conclusion

Granular data from the SCREEN-BE study identified multiple knowledge gaps and barriers to appropriate BE screening mainly in the primary care setting. These potential modifiable targets are ripe for future studies that focus on:

Intervention trials using decision-support algorithms along with integrated reminder systems to incorporate BE screening during PCP visits and improve the adherence and effectiveness of BE screening.

Qualitative research to understand opinions of key stakeholders (patients and caregivers, GIs, PCPs, pathologists, public health experts) and create screening algorithms that consider resources, cost, and feasibility.

Education and dissemination of screening guidelines among PCPs given their lack of knowledge and nonadherence to GI society guidelines

This is particularly relevant as we embark on an era of less invasive non-endoscopic screening tools which are mostly designed to be used in the primary care setting to facilitate population-based screening 11, 23 It will be critical to assess patient attitudes and risk tolerance when considering how to integrate these non-endoscopic studies into clinical practice. Additionally, the success of a screening program will depend on our ability to identify those at highest risk who would benefit most from screening through risk stratification modeling and machine learning. As emphasized by the provider survey responses, we continue to need effectiveness data and population-based studies demonstrating the impact of screening on hard outcomes to inform meaningful guidelines. To make population level improvements in EAC diagnosis and outcomes we will need to work as a larger medical and scientific community to refine the current paradigm of BE screening.

Supplementary Material

Grant Support:

• Gary W. Falk: NIH/NIDDK—P30-DK050306 and NIH/NCI—U54-CA163004

• Amit G. Singal: NIH/NCI—R01-CA222900

• Ravy K. Vajravelu: NIH/NIDDK—K08-DK119475, American College of Gastroenterology—ACG-CR-005-2020

• Sachin Wani: NIH/NIDDK—U34-DK124174, U01-DK129191, American College of Gastroenterology—ACG-CR-005-2020, and University of Colorado Department of Medicine Outstanding Early Scholars Award

Role of the funding source:

This research was funded by the American College of Gastroenterology (ACG-CR-005-2020 to RKV and SW). The funders of this study had no role in the study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, or presentation of the results.

Abbreviations:

- BE

Barrett’s esophagus

- CI

confidence interval

- EAC

esophageal adenocarcinoma

- EHR

electronic health record

- GERD

gastro-esophageal reflux disease

- GI

gastroenterologist

- PCP

primary care provider

- RCT

randomized controlled trial

- USPSTF

U.S. Preventative Services Task Force

SCREEN-BE Study Investigators

Camille J Hochheimer PhD1, Wyatt Tarter MS1, Jazmyne Gallegos BA1, Jack O’Hara BA1, Shalika Devireddy1, Bryan Golubski MD2, Kenneth J Chang MD3, Jason Samarasena MD3, Frank I. Scott MD MSCE1, Gary W. Falk MD MS4

Affiliations

1. Division of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus, Aurora, Colorado

2. Department of Internal Medicine, University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas, Texas

3. Digestive Health Institute, University of California Irvine, Orange, CA

4. Division of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, Perelman School of Medicine, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

Footnotes

Data Transparency Statement: Deidentified individual participant data that underlie the reported results will be made available 3 months after publication for a period of 5 years after the publication date. Proposals for access should be sent to corresponding author.

Preprint Server: None

Disclosures:

• Gary W. Falk: Consultant for Cernostics, CDx, Exact Sciences, Interpace, Lucid and Phathom Pharmaceuticals.

• Amit G. Singal: Consultant for Grail

• Sachin Wani: Consultant for Boston Scientific, Cernostics, Interpace, Exact Sciences and Medtronic. Research Support: Lucid, Ambu, CDx Diagnostics

• Kenneth J. Chang: Consultant for Cook, Olympus, EndoGastric Solutions, Medtronic, Erbe

• Jennifer M. Kolb, Camille J. Hochheimer, Frank I. Scott, Wyatt Tarter, Anna Tavakkoli, and Ravy K. Vajravelu have no relevant conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- 1.Kolb JM, Han S, Scott FI, et al. Early-Onset Esophageal Adenocarcinoma Presents With Advanced-Stage Disease But Has Improved Survival Compared With Older Individuals. Gastroenterology 2020;159:2238–2240 e4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shaheen NJ, Falk GW, Iyer PG, et al. ACG Clinical Guideline: Diagnosis and Management of Barrett’s Esophagus. Am J Gastroenterol 2016;111:30–50; quiz 51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Spechler SJ, Sharma P, Souza RF, et al. American Gastroenterological Association technical review on the management of Barrett’s esophagus. Gastroenterology 2011;140:e18–52; quiz e13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Asge Standards Of Practice C, Qumseya B, Sultan S, et al. ASGE guideline on screening and surveillance of Barrett’s esophagus. Gastrointest Endosc 2019;90:335–359 e2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fitzgerald RC, di Pietro M, Ragunath K, et al. British Society of Gastroenterology guidelines on the diagnosis and management of Barrett’s oesophagus. Gut 2014;63:7–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tan MC, Mansour N, White DL, et al. Systematic review with meta-analysis: prevalence of prior and concurrent Barrett’s oesophagus in oesophageal adenocarcinoma patients. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2020;52:20–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lagergren J, Bergström R, Lindgren A, et al. Symptomatic gastroesophageal reflux as a risk factor for esophageal adenocarcinoma. N Engl J Med 1999;340:825–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Eusebi LH, Telese A, Cirota GG, et al. Systematic review with meta-analysis: risk factors for Barrett’s oesophagus in individuals with gastro-oesophageal reflux symptoms. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2021;53:968–976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Delshad SD, Almario CV, Chey WD, et al. Prevalence of Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease and Proton Pump Inhibitor-Refractory Symptoms. Gastroenterology 2020;158:1250–1261 e2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nguyen TH, Thrift AP, Rugge M, et al. Prevalence of Barrett’s esophagus and performance of societal screening guidelines in an unreferred primary care population of U.S. veterans. Gastrointest Endosc 2021;93:409–419 e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rubenstein JH, McConnell D, Waljee AK, et al. Validation and Comparison of Tools for Selecting Individuals to Screen for Barrett’s Esophagus and Early Neoplasia. Gastroenterology 2020;158:2082–2092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Menezes A, Tierney A, Yang YX, et al. Adherence to the 2011 American Gastroenterological Association medical position statement for the diagnosis and management of Barrett’s esophagus. Dis Esophagus 2015;28:538–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bandura A Health promotion by social cognitive means. Health Educ Behav 2004;31:143–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Singal AG, Tiro JA, Murphy CC, et al. Patient-Reported Barriers Are Associated With Receipt of Hepatocellular Carcinoma Surveillance in a Multicenter Cohort of Patients With Cirrhosis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2021;19:987–995 e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lin OS, Mannava S, Hwang KL, et al. Reasons for current practices in managing Barrett’s esophagus. Dis Esophagus 2002;15:39–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ladabaum U How I do it: Does this cost-effectiveness analysis convince me about screening for Barrett’s esophagus? Gastrointest Endosc 2019;89:723–725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Heberle CR, Omidvari AH, Ali A, et al. Cost Effectiveness of Screening Patients With Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease for Barrett’s Esophagus With a Minimally Invasive Cell Sampling Device. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2017;15:1397–1404 e7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fitzgerald RC, di Pietro M, O’Donovan M, et al. Cytosponge-trefoil factor 3 versus usual care to identify Barrett’s oesophagus in a primary care setting: a multicentre, pragmatic, randomised controlled trial. The Lancet 2020;396:333–344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kramer JR, Shakhatreh MH, Naik AD, et al. Use and yield of endoscopy in patients with uncomplicated gastroesophageal reflux disorder. JAMA Intern Med 2014;174:462–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chey WD, Inadomi JM, Booher AM, et al. Primary-care physicians’ perceptions and practices on the management of GERD: results of a national survey. Am J Gastroenterol 2005;100:1237–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Simmons OL, Feng Y, Parikh ND, et al. Primary Care Provider Practice Patterns and Barriers to Hepatocellular Carcinoma Surveillance. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2019;17:766–773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hamel C, Ahmadzai N, Beck A, et al. Screening for esophageal adenocarcinoma and precancerous conditions (dysplasia and Barrett’s esophagus) in patients with chronic gastroesophageal reflux disease with or without other risk factors: two systematic reviews and one overview of reviews to inform a guideline of the Canadian Task Force on Preventive Health Care (CTFPHC). Syst Rev 2020;9:20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kolb JM, Wani S. A Paradigm Shift in Screening for Barrett’s Esophagus: The BEST Is Yet to Come. Gastroenterology 2021;160:467–469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.